Introduction

With the sudden shift to virtual healthcare operations that occurred during the pandemic, the lack of digital access potentially worsened disparities in healthcare access for some patients already facing severe inequities.1 Digital access has become a vital component of day-to-day living with many vital services also becoming easily accessible through the internet. There is a large overlap between patients who have low-income and those who have low digital literacy and limited access to computers and internet; for example, about 30% of all households in the United States lack broadband access, however 59% of homes with household income less than $20,000 lack access.2 Many state and federal government programs exist to address the need for digital access, including the Emergency Broadband Benefits program,3 and a critical component of providing funds is developing the human resources needed to support teaching technology skills.

The availability of government-funded programs increased to provide basic internet access and devices such as tablets for populations in need. However, tackling the Digital Divide should go beyond ensuring affordability. There is also a foundational need for addressing digital literacy and providing training and support for key groups like older adults. Otherwise, these programs risk neither helping effectively nor sustainably. In this commentary, we discuss the need to consider supportive training in tandem with any program that delivers internet access and devices to community members with limited prior experience using digital technology, which we saw firsthand while implementing a program to improve digital access in the community. Finally, we share some important considerations for targeting key barriers to begin closing the Digital Divide.

Our Experience Connecting Older Community Members with Digital Access

We implemented a program, funded by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Engagement Award, that delivered tablets to 20 older community members in Baltimore, Maryland, and provided broadband access via the Comcast Internet Essentials program. We provided one-on-one supportive training to assist the community members in connecting to the internet and using basic tablet functionality (e.g., emails and video conferencing). We conducted an evaluation of the program and found that community members repeatedly identified the training as the most useful component. Our community members mentioned that they had participated in other programs before where they received a laptop or a smartphone, but remarked that they were “given the laptop and then never talked to again”. As a result, they never gained comfort using the device on their own. A community member also voiced that some older adults feel anxious and afraid when attempting to use something so unfamiliar to them and knowing that a trainer would be available to assist them in learning how to properly use new technologies instilled confidence within our program.

Programs Addressing Affordability of Internet and Devices

Emergency Broadband Benefits is a federal-funded program that pays up to $50 a month for a broadband access plan, and up to $100 for a device (tablet, laptop, or smartphone) for qualified individuals.3 There are many other programs at local-, state-, and federal levels that fund broadband expansion. The creation of these programs suggests that broadband service is quickly becoming recognized as a necessity rather than a luxury or non-essential commodity, and that issues of accessibility and affordability are inextricably linked with promoting equity. Many of these programs rely on outreach partners such as community-based organizations to disseminate information about such benefits.

Outreach: A Necessary Component of the Programs

We emphasize that outreach and education about these programs are not trivial efforts. We encourage readers to visit the main webpage of Emergency Broadband Benefits at fcc.gov/broadbandbenefit and imagine telling someone who has never used communication technologies beyond a basic flip phone to sign-up. It would be a tough feat for many older adults, particularly for those who lack a compatible device and available internet to access the webpage in the first place. Alternative solutions may involve program staff temporarily lending a device and/or network access, or helping people apply for such benefits by filling out paper forms and mailing them by postal service. Either way, programs should also consider whether acceptability is another issue to address; some older adults may inherently resist adopting new technologies and internet access for conducting their personal affairs and/or for socializing. This may be attributed to the anxiety/fear that one of our community members described about some of their peers.

Enrolling is the first step, followed by ensuring that people have the support they need to use the device and access the internet successfully. There are organizations that offer public- or philanthropic-programs to provide service support at no or little cost, so people can be connected to such programs through outreach. Faith-based groups like churches, community centers, and other community-based organizations are all venues that can serve as effective partners for spreading important information and resources.

Conclusion

The Digital Divide has been a pressing and longstanding issue.4 With the increasing affordability of devices and broadband access, along with the availability of some supplemental coverage for eligible people through government-funded programs, we have an opportunity to significantly close the Digital Divide. However, if we do not consider the human service component that can help promote comfort and literacy with digital tools and devices for older adults, we will continue to fail at achieving digital equity and inclusivity in an increasingly virtual world. Recently introduced programs improving affordability are a wonderful starting point, but without following through with substantial outreach and supportive training, we risk “helicoptering” in with short-sighted plans and then perpetuating sentiments on-the-ground behind feeling “never talked to again” when we leave.

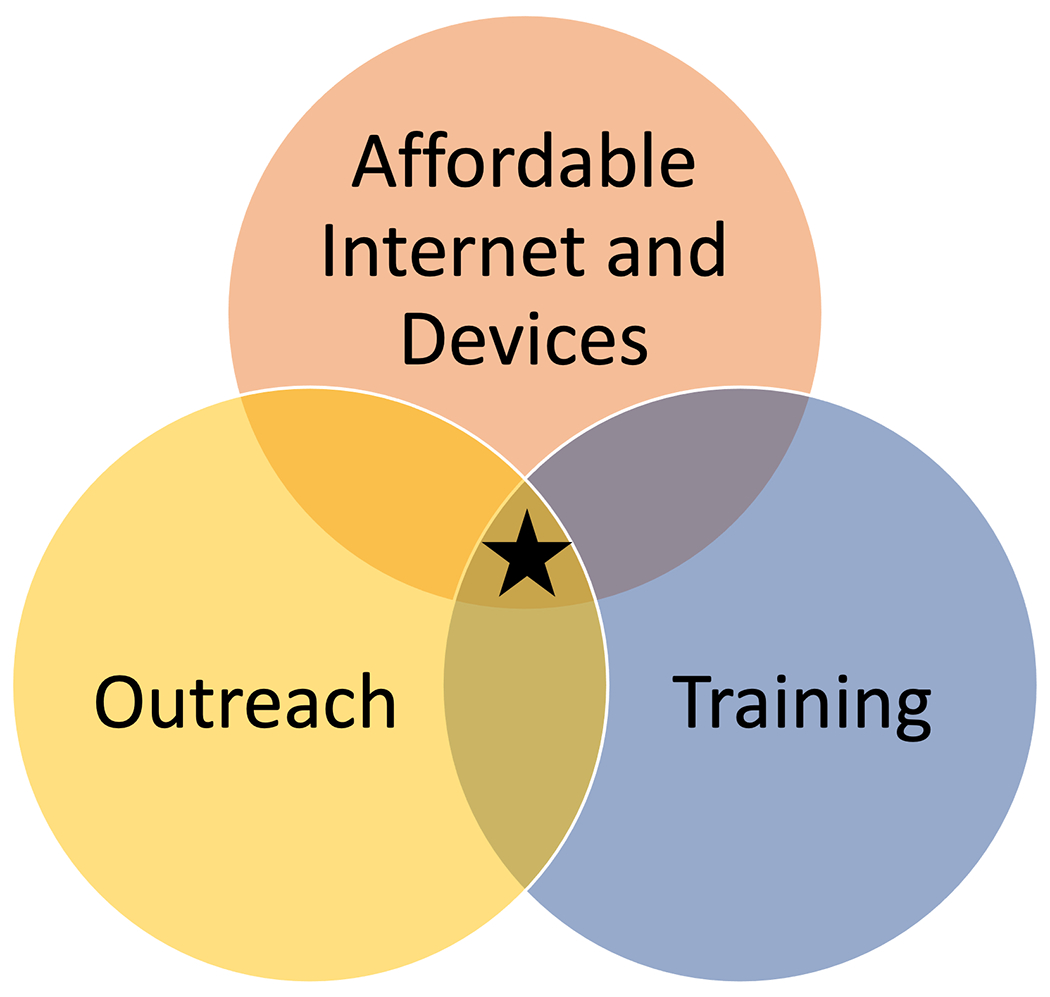

Figure 1.

Key Considerations for Bridging the Digital Divide. The star indicates that addressing all three is recommended: Affordability, Outreach, and Training.

Acknowledgements

K. Gleason receives funding from the following sources: NIH NCATS Institutional Career Development Core, KL2 TR003099, NIH NCATS Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, UL1TR003098, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research institute, EAIN-00178, Addressing the Digital Divide to Improve Patient Centered-Outcomes Research, and Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, #9904, Development of a Patient-Reported Measure Set of Diagnostic Excellence.

J.J. Suen is supported in-part by the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health (F31AG071353) and the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Sponsor’s Role:

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute funded the program referenced in the commentary. The sponsor had no influence on the writing of this commentary.

Footnotes

Twitter: @KTG_RN, @SuenJonathan

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lai J & Widmar NO Revisiting the Digital Divide in the COVID-19 Era. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 43, 458–464 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horrigan J & Duggan M Home Broadband 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/12/21/home-broadband-2015.

- 3.Federal Communications Commission. Emergency Broadband Benefits. https://www.fcc.gov/broadbandbenefit (2021).

- 4.Anderson M & Kumar M Digital divide persists even as lower-income Americans make gains in tech adoption. Pew Res. Cent (2019). [Google Scholar]