Abstract

Background:

The Geriatric Emergency Department (ED) Guidelines recommend screening older adults during their ED visit for delirium, fall risk/safe mobility, and home safety needs. We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change (ERIC) tool for pre-implementation planning.

Methods:

The cross-sectional survey was conducted among ED nurses at an academic medical center. The survey was adapted from the CFIR Interview Guide Tool and consisted of 21 Likert scale questions based on four CFIR domains. Potential barriers identified by the survey were mapped to identify recommended implementation strategies using ERIC.

Results:

Forty-six of 160 potential participants (29%) responded. Intervention Characteristics: Nurses felt geriatric screening should be standard practice for all EDs (76.1% agreed some/very much) and that there was good evidence (67.4% agreed some/very much). Outer setting: The national and regional practices such as the existence of guidelines or similar practices in other hospitals were unknown to many (20.0%). Nurses did agree some/very much (64.4%) that the intervention was good for the hospital/health system. Inner Setting: 67.4% felt more staff or infrastructure and 63.0% felt more equipment were needed for the intervention. When asked to pick from a list of potential barriers, the most commonly chosen were motivational (I often don’t remember (n=27, 58.7%) and It is not a priority (n=14, 30.4%)). The identified barriers were mapped using the ERIC tool to rate potential implementation strategies. Strategies to target culture change were: identifying champions, improve adaptability, facilitate the nurses performing the intervention, and increase demand for the intervention.

Conclusion:

CFIR domains and ERIC tools are applicable to an ED intervention for older adults. This pre-implementation process could be replicated in other EDs considering implementing geriatric screening.

Keywords: Emergency Department, Implementation, CFIR, screening tools

INTRODUCTION

The 2014 Geriatric ED Guidelines recommend screening all older adults in the ED for geriatric syndromes such as fall risk and delirium.(1) In 2018, the American College of Emergency Physicians instituted a Geriatric ED accreditation process based on these guidelines with a tiered accreditation system (Level 1, 2, or 3).(2) Despite evidence for improved quality and decreased costs of care, uptake of geriatric screening throughout the >5,000 EDs in the United States has been low, with only 15 EDs (as of March 2021) receiving the highest Level 1 which requires multiple geriatric screening protocols.(3, 4) Of the remaining 211 Level 2 or 3 Geriatric EDs, only 17% (n=36) screen for delirium, 36% (n=77) screen for fall risk, and 17% (n=35) screen for functional decline.(3) This suggests that implementation of screening tools into the ED setting is a barrier to Geriatric ED dissemination. The objective of this article is to demonstrate how using an implementation science framework can improve the planning and integration of geriatric screening tools in an ED setting.

To date, implementation of geriatric screening has been done using informal, non-implementation science approaches which often lack front line provider input on barriers and can be difficult to replicate at other healthcare institutions.(5, 6) An alternative is Implementation and Dissemination Science. Implementation Science evaluates the internal and external factors associated with program success as well as the necessary factors for replication.(7, 8) Implementation frameworks dictate a formal evaluation of barriers and formal methodology to choosing implementation strategies. A standardized approach helps other sites understand the rational for the strategies chosen and avoids the dreaded “it seemed like a good idea at the time” strategy.(9) Other healthcare teams have seen improvements by switching from QI to an Implementation Science approach, identifying previously unknown barriers from intervention complexity and electronic medical record (EMR) issues to confusion about adaptability to different patient populations or clinic workflows.(10, 11) The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR, cfirguide.org)(12) has been used successfully both in the ED and for implementation of geriatric interventions in other settings.(13, 14) This implementation framework is applicable to the ED because it breaks down barriers to change along domains relevant to complicated healthcare interventions: intervention characteristics, internal setting, outer setting, and individual characteristics. Once the barriers to implementation are identified, an accompanying tool called the CFIR Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change (ERIC) pinpoints high yield, targeted implementation strategies.

Our Geriatric ED initially implemented geriatric screening using normal, informal processes (see Methods: Initial QI Approach). Despite education and encouragement from management, compliance was low at <5%. This motivated us to switch to a formal Implementation Science approach. We present and explain the process of using the CFIR-ERIC tool to identify and address remaining barriers to geriatric screening implementation.

METHODS

Design:

A cross-sectional survey based on CFIR was conducted as part of a larger ongoing effectiveness-implementation hybrid study of geriatric screening in the ED.(15) The survey was approved both by the Institutional Review Board and the nurses’ union.

Setting:

The 106 bed academic, tertiary referral hospital ED includes a 15 bed oncology area with oncology-trained ED nurses and a 20 bed Observation Unit area. It is an accredited Level 1 Geriatric ED.(16)

Initial QI Approach:

Prior Level 1 Geriatric EDs overcame the geriatric screening burden by hiring supplementary staff to perform the screening, such as dedicated nurses or case managers.(17–20) Additional staff or funding was not available at our institution, necessitating the integration of screening into the current staff load and clinical workflow. Our interdisciplinary Geriatric ED team brainstormed solutions using process mapping to decide where, when, and who would perform the screening. Workflow studies were performed to streamline the process and identify barriers.(21) The process was piloted in our ED Observation Unit in 2015 expanded to the entire ED in 2018. ED nurse educators and geriatric EM physicians were the program champions. Nurses underwent a 2 hour in-person training course designed by a geriatric emergency medicine physician and a Geriatric Emergency Nurse Education (GENE) certified nurse educator.(22) The proportion of older adults receiving screening was tracked via monthly EMR reports using a Tableau dashboard (Tableau, Seattle WA). The program had very good leadership support and nurse managers and nurse educators volunteered to be champions. Despite booster education sessions and reminders at nurse huddles, screening rates remained very low at <5%.

Geriatric screening:

The screening process consists of the Brief Delirium Triage Screen, the 4 Stage Balance Test, and the Identifying Seniors at Risk Score, requires 3 minutes and no additional resources.(23–25) The screening assessments were built into the EMR as a nursing rounding assessment to fulfill hourly rounding criteria. The bedside nurse performs the geriatric screening for any patient ≥65 years old roomed in any ED bed, including the oncology and observation areas. Patients who screen positive for delirium, fall risk, polypharmacy (on ≥6 medications), or general risk can be evaluated by a consulting geriatrician, a physical therapist, occupational therapist, an ED pharmacist, or an ED case manager as determined by the ED physician. When multiple consults or interventions are needed, the ED Observation Unit is used to provide appropriate time for these consultations.(26)

Survey Participants:

Participants were front line staff nurses who worked in the ED and ED Observation Unit. Physicians were not surveyed as they do not perform the geriatric screening. Nurses in the float pool, nursing administration, and nurse educators were excluded as they are not representative of front line staff perceptions and attitudes.

Survey:

Investigators constructed the survey using the CFIR Interview Guide (CFIRguide.org) which provides questions based on the CFIR model and can be tailored to the intervention and setting (see Supplemental Table S1). The questions chosen reflected the first 4 CFIR domains of Intervention Characteristics, Outer Setting, Inner Setting, and Individual Characteristics (Supplemental Table S2). The final domain of Process was not assessed as the health system uses Lean Six Sigma as their implementation process. Intervention characteristics (5 items) focused on the perceived strength of evidence, quality and relative advantage. Outer Setting (5 items) reflected the extent to which patient needs are known and prioritized by the organization, external peer pressure to implement the screening, and external policies and incentives that influence the implementation. Inner Setting (5 items) included infrastructure changes, available resources, access to knowledge and information, and local culture. Individual Characteristics (5 items) included nurses’ self-efficacy, knowledge, and beliefs.

Participants rated their agreement on a 6 item scale of I don’t agree at all, I somewhat agree, I am neutral, I agree some, I agree very much, and I don’t know. The survey also included an additional multiple choice question identifying potential barriers with a free text option to write in other barriers or comments on the process. The Geriatric ED team, consisting of implementation scientists, ED nurse educators, and ED physicians reviewed the questions and survey format for ease of readability and clarification of any ambiguous information. Refinements were made based on their feedback.

The survey was built into REDCap,(27) an electronic HIPAA-compliant data capture system, and distributed to the work email of all potential participants in August 2020. Potential participants received 2 automatic reminders if they did not complete the survey. Nursing administration also encouraged participation with reminders from leadership during huddles. There was no incentive to participate and individual responses were blinded/anonymized.

Statistical analysis:

Data were entered and analyzed using SAS software (SAS, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables. Participants’ responses were re-classified as agreement (agreed some or very much), neutral, disagreement (disagree somewhat or very much), and no knowledge (I don’t know). Six survey questions where phrased negatively and responses were inverted for aggregation. The study goal was to compare overall trends; as such no hypothesis testing or confidence intervals are reported.

Matching Identified Barriers to Potential Interventions:

The CFIR-ERIC tool v0.53 (https://cfirguide.org/choosing-strategies/) identifies implementation strategies that are most efficacious at addressing the barriers within specified CFIR domains.(28) During the development of the ERIC tool, experts ranked each strategy on its ability to target/improve a specific barrier. The points in the tool are the proportion of experts who rated that strategy in the top 7 best for that barrier. The tool is an Excel spreadsheet which tabulates the points of each strategy over the barriers identified by the CFIR assessment. The output of the tool is thus a total number of points that represent how well that implementation strategy is expected to address the multiple identified barriers. This allows the implementation team to identify strategies that simultaneously address multiple barriers and/or to evaluate strategies targeting individual barriers. For example, the strategy “Inform local opinion leaders” is weighted as having a large impact on barriers within “Tension for Change” (39 points) and “Individual Stage of Change” (28 points) but is unlikely to be a successful strategy for addressing the barrier of “Self-Efficacy” (4 points). The top strategies for each separate barrier are reported as well as the top overall strategies.

RESULTS:

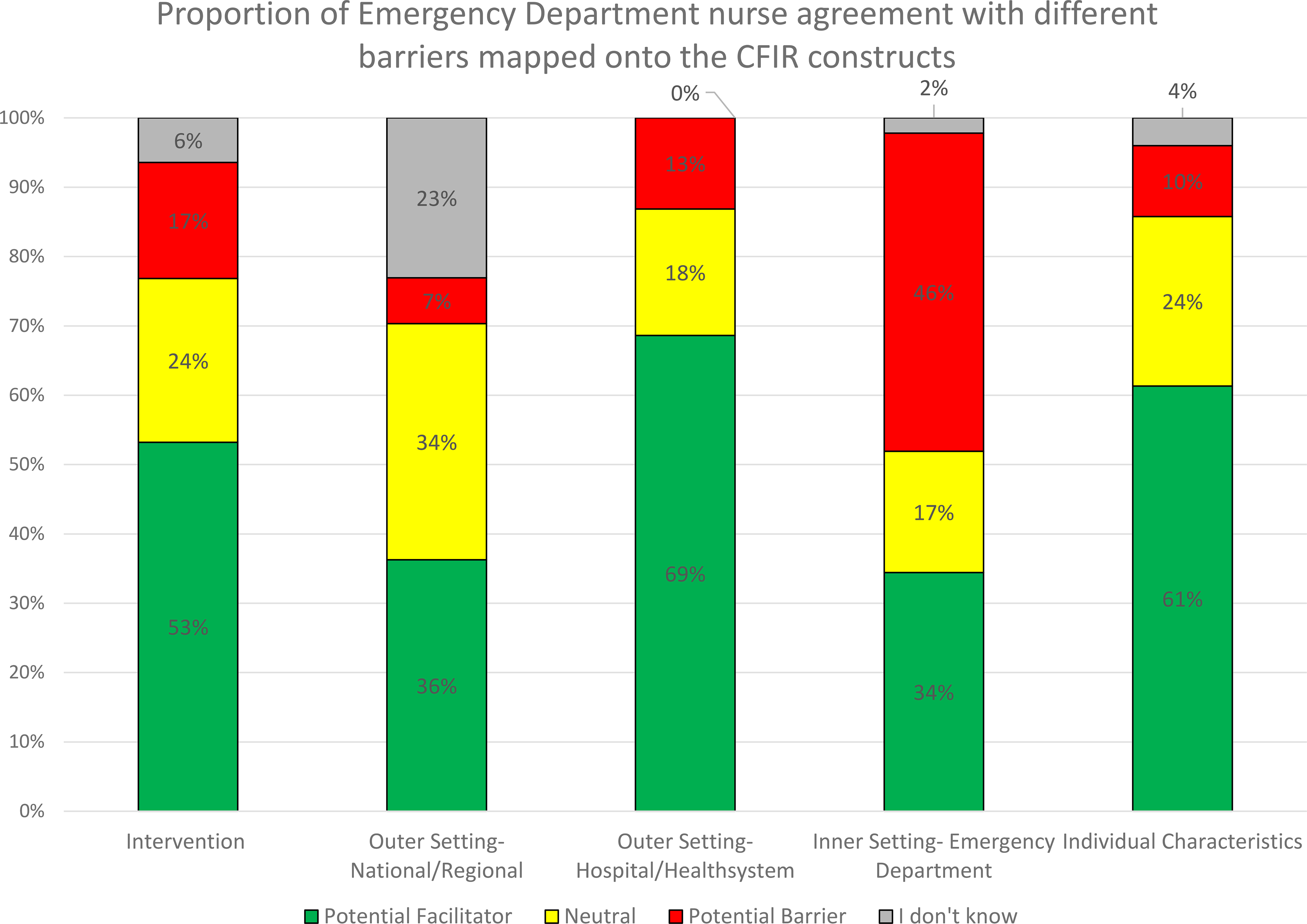

The survey was sent to 160 ED nurses with 46 individuals responding (29% response rate). The respondents primarily identified as bedside nurses (n=43, 93.5%) and 84.9% (n=39) had taken the geriatric training class. All questions were included in the analysis except for one of the Inner Setting statements, I have changed my practice based on the Geriatrics training I had. This was excluded because 7 people (15.2%) had not yet taken the geriatric training, but none of the untrained people answered “I don’t know”. It is unclear how the statement was interpreted, as half the untrained agreed or very much agreed that they changed their practice based on training. Of the remaining 20 Likert scale questions, seven had missing responses (range, 0–2 missing responses per question, see Supplemental Table S3). The aggregated proportions of agreement within the different CFIR domains are displayed in Figure 1 and categorized as potential facilitator, potential barrier, neutral or ‘don’t know’.

Figure 1:

Survey answers organized by CFIR construct demonstrate varying degrees of agreement across the constructs. In this analysis, Agree very much/Agree some responses were considered to be areas of potential facilitators (green), and Somewhat disagree/Don’t agree answers identified potential barriers to implementation (red). See Supplemental Table S1 for individual survey prompts and responses and Supplemental Table S2 for the associated CFIR construct map.

Intervention characteristics:

Most participants endorsed the value of the intervention reflected in the survey prompts This should be standard practice for all EDs (76.1% agreement) and There is good evidence that the geriatric screening will help our patients in the ED (67.4% agreement). However, almost half (43.5%, n=20) perceived that their colleagues would need more evidence before agreeing to do the intervention. Some nurses (28.3%, n=13) felt that the second step of obtaining the consultations in the ED Observation Unit was too complex.

Outer Setting - National and Regional:

The existence of guidelines or similar practices in other hospitals, were unknown to 20.0% (n=9). Less than half (n=21, 46.7%) agreed very much/somewhat that We have to do this because of national guidelines or rules. A quarter (n=12, 26.1%) did not know what other EDs do. This was the largest knowledge gap identified.

Outer Setting - Hospital/Health system:

Nurses agreed some/very much (64.4%, n=29) that the intervention was good for the hospital/health system. They felt that the screening tools should also be done on inpatient units (n=38, 82.6%). A minority were concerned that the intervention may not meet the needs of patients (n=5, 10.9%).

Inner setting:

Nurses identified the Inner Setting of the ED as an area of potential barriers to screening. Two thirds (n=31, 67.4%) felt more staff or infrastructure were needed and 63.0% (n=29) felt more equipment was needed. Ten nurses (21.7%) disagreed with the prompt about having sufficient training, however half of these nurses had not had the Geriatric course. The survey identified a local culture of resistance to new interventions, as over half (56.5% (n=26)) agreed that Getting everyone to buy into the screening process would be very hard.

Individual characteristics:

Over half of the nurses (56.5%, n=26) were confident that they could screen >80% of their geriatric patients, but only 30.4% (n=14) had confidence in their colleagues ability to do so. A minority (8.7%, n=4) had low self-efficacy and agreed some/very much with the prompt I don’t want an older adult assigned to my section because I don’t want to have to do the screening. While self-efficacy was low, most (69.6%, n= 32) agreed that the fall risk screening was better than the standard of care triage fall risk questions, and 67.4% (n=31) had positive thoughts towards managing delirium.

Specific barriers:

Multiple barriers could be chosen (Figure 2). The most common were I often don’t remember (n=27, 58.7%) and It’s not a priority (n=14, 30.4%) (Figure 2). Of the 39 nurses who completed the Geriatric Screening tools training, only 2 (5.1%) endorsed the educational barrier (I don’t know where to find/chart them) suggesting adequate training. Free text feedback on barriers was provided by 12 nurses. Three recommended EMR changes to improve awareness of the screening tools and ease of access. There were four comments with concerns that the ED was not the right place (recommended inpatient only) or right time (patients too sick or tired at night). Several also recommended increased staffing of nursing assistants to help make the fall risk screening safer.

Figure 2:

Barriers to nurses screening older adults with validated geriatric assessment tools in the Emergency Department. Options were non-exclusive and nurse participants were allowed to choose as many as they felt applied.

Potential Intervention Strategies:

One barrier identified in the survey but not included in the ERIC mapping tool was “Inner Setting - Availability of Resources”. Due to health system constraints, increasing staffing or resources without proportional increases in patient volume is not a viable implementation strategy. Table 1 displays the remaining barriers amenable to intervention matched to the top implementation strategies by the CFIR-ERIC tool. The strategies with the most ability to target the barriers identified by this survey were Identify champions (340 points), Alter incentive/allowance structure (302 points), Conduct local consensus discussions (249 points), Assess for readiness/identify barriers and facilitators (211 points), Inform local opinion leaders (205 points), and Promote adaptability (189 points).

Table 1:

Potential barriers identified by the nurses were mapped onto the CFIR framework. The CFIR Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change (CFIR-ERIC) tool was used to identify potential strategies. Some potential strategies may not be feasible, and it is up to an implementation team to pick the strategies that target multiple barriers and are feasible and applicable to their setting and intervention. Topic and descriptions are reproduced with permission from Waltz, et al 2019.

| Topic | Description | Potential Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| INTERVENTION CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Adaptability | Stakeholders do not believe that the innovation can be sufficiently adapted, tailored, or re-invented to meet local needs. | Promote adaptability; Conduct local needs assessment; Facilitation; Identify champions |

| OUTER SETTING | ||

| Peer Pressure | There is little pressure to implement the innovation because other key peer or competing organizations have not already implemented the innovation nor is the organization doing this in a bid for a competitive edge. | Alter incentive/allowance structures; Identify champions; Increase demand; Involve patients and their family members. |

| External Policy & Incentives | External policies, regulations (governmental or other central entity), mandates, recommendations or guidelines, pay-for-performance, collaborative, or public or benchmark reporting do not exist or they undermine efforts to implement the innovation. | Alter incentive/allowance structures; Involve executive boards; Build a coalition; Inform local opinion leaders |

| INNER SETTING | ||

| Culture | Cultural norms, values, and basic assumptions of the organization hinder implementation. | Identify champions; Conduct local consensus discussions; Inform local opinion leaders; Facilitation; Tailor Strategies |

| Tension for Change | Stakeholders do not see the current situation as intolerable or do not believe they need to implement the innovation. | Identify champions; Conduct local consensus discussions; Inform local opinion leaders; Promote adaptability; Involve patients and family members |

| Relative Priority | Stakeholders perceive that implementation of the innovation takes a backseat to other initiatives or activities. | Conduct local consensus discussions; Alter incentive/allowance structures; Increase demand; Mandate change by leadership |

| Organizational Incentives & Rewards | There are no tangible (e.g., goal-sharing awards, performance reviews, promotions, salary raises) or less tangible (e.g., increased stature or respect) incentives in place for implementing the innovation. | Alter incentive/allowance structures; Identify champions; Audit and feedback; Develop tools for quality monitoring. |

| CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIVIDUALS | ||

| Self-efficacy | Stakeholders do not have confidence in their capabilities to execute courses of action to achieve implementation goals. | Identifying champions; Creating a learning collaborative; Facilitation; Making training dynamic; Ongoing training |

| Individual Stage of Change | Stakeholders are not skilled or enthusiastic about using the innovation in a sustained way. | Identifying champions; Making training dynamic; Alter allowance/incentive structure; Promote adaptability |

Short Term Results:

The strategies of Identify champions, Alter incentive, Inform local opinion leaders, and Promote adaptability were chosen by the implementation team and began March 2021. Implementation was delayed after the initial survey due to the winter 2020 COVID-19 wave. Screening increasing from prior levels of 7.5% (88/1168) in February 2021 to 20.0% (283/1431) in March, 28.3% (379/1335) in April, 40% (552/1380) in May, and 42% (538/1271) in June 2021. These numbers are preliminary as our datasets do not yet include the patients who met screening exclusion caveats implemented under the adaptability strategy. Full impact adjusting for this as well as other confounders will be reported upon implementation completion.

DISCUSSION:

The CFIR-ERIC were applicable to the ED setting and identified appropriate implementation strategies. The nursing survey identified specific barriers to geriatric screening: 1) Lack of applicability or adaptability to individual patient needs (Intervention Characteristics); 2) Lack of knowledge of the importance of screening, including the existence of national guidelines and accreditation (Outer Setting); 3) A culture of distrust that nursing colleagues would buy in (Inner Setting); 4) Lack of time or being understaffed (Inner Setting), and 5) Lack of motivation (Individual Characteristics). All but lack of motivation were newly identified with the CFIR approach vs our prior QI approach. These findings echo barriers identified in studies of geriatric ED screening in the Netherlands and Canada.(5, 29) The Dutch study also identified lack of adaptability to the patient as a large factor in screening non-adherence. This suggests some external validity to this approach, but does not imply that every site will have the same barriers.

Our survey found that most agree that screening for geriatric syndromes helps patients in the ED, should be standard practice for all EDs, and that the assessments are better than the standard fall risk screen. This suggests that disagreement with the intervention itself is not the barrier, and the screening tools themselves were not difficult or infeasible. This is likely due to the initial QI approach, during which a lot of time was devoted to choosing geriatric screening tools adapted to the ED setting.(21) The CFIR approach found that while adapted to the setting, the tools were not adaptable to the individual patient. For example, a patient who is non-ambulatory at baseline cannot perform the 4 Stage Balance Test. Adaptability is defined as the ability to change the intervention to fit a particular situation or environment. The CFIR approach encouraged us to think of adaptability in this context to be adapting the intervention to the individual patient as well as the environment. The consensus solution was to add in a menu of exclusion criteria to the screening tool, so that the nurses could document the reason why a particular screening tool was inapplicable to the individual while still building a culture of documenting screening every time.

The most barriers were found in the Inner Setting, the ED itself. The ED setting is complex, decision-dense, non-linear, consistently over-capacity, and has continued staff turnover. A lack of time and staffing as barriers was not unexpected. Similar to other hospitals, increasing staffing or resources without proportional increases in patient volume is not a viable implementation strategy, and so was not included in the ERIC analysis. However, implementation strategies aimed at reducing the time needed or the burden on the nurses are possible for most EDs. To decrease nurse burden, the implementation team mapped the process within the EMR. Recommendations included changing the placement of the screening tools to move them to the top of the nurse assessment list, as both a visual prompt (addressing barrier of lack of remembering) and to make it faster to find and complete. Other ideas were to distribute the responsibility across areas of the ED and for the patient flow coordinator (a designated ED nurse) who assigns patients to ED beds to be cognizant of the additional nursing burden of caring for multiple older adults.(30)

The ERIC analysis suggested Identifying champions, conducting local consensus discussions, and increasing demand. Conducting local consensus discussions is using focus groups or meetings to develop stakeholder relationships and engagement. Work is underway with training champions to affect culture and lead local consensus discussions with the nurses.(31) Increasing demand means to engage the consumers of the work to create a “pull system” of people asking for it to be done. Increasing demand in this system was interpreted as increasing the demand for the screening information. This required the physicians to ask for the data, which we developed by creating an EMR template phrase for physicians to easily pull the geriatric screening data into their notes to guide medical decision making.

The final barrier was Individual Characteristics: motivation and self-efficacy, which we interpret as remembering to do the screening and prioritizing it among the myriad of patient care duties. An external contributor to this barrier is that nurses were responding to the survey in August and September 2020, 7 months into the COVID-19 pandemic with the added stress and staffing issues that entailed. The CFIR-ERIC strategies recommended for improving self-efficacy included identifying champions, making training dynamic, and ongoing training (Table 1). Consistent with prior studies, our initial education was not sufficient to change culture and self-efficacy.(32) CFIR also identified that our initial education did not sufficiently address the external forces of national guidelines and accreditation. An educational campaign that appeals to pride at having this intervention when most others don’t could be successful at overcoming the Outer Setting and Inner Setting (emotional appeal, motivation) barriers together.

Front line nurse champions sharing positive stories is another dual purpose intervention, providing education and motivation. Our initial champions were in nursing and physician leadership, and this evaluation pointed out the potentially greater impact on motivation and culture change of recruiting front line staff champions. Trusted coworkers performing the action and sharing stories also can eventually catalyze positive-task generated feedback, which provides continued motivation and culture change.(33, 34)

Limitations of this work include the low response rate and single site nature. Surveys or focus group interviews with small sample sizes have been successful in identifying applicable interventions in other CFIR-ERIC studies, but this is still a limitation.(35, 36) Also, we were unable to address non-responder bias, as demographic information was deliberately excluded to ensure anonymity for all participants. While a low response rate, the survey did capture a range of knowledge and viewpoints from those who always did the screening (4.4%) to those who had never heard of it or never had the education (15%) which provides some internal validity. Others using this approach could consider including personal requests by the investigators, adding additional reminders (2 were sent), or adding incentives for survey completion. A final limitation of this study is the novel setting, as the CFIR interview guide prompts have not been validated in an ED setting and not all CFIR-ERIC strategies may apply. However, implementation frameworks and tools are developed to be adaptable to different projects and settings.

The initial strategies identified by CFIR-ERIC tool have resulted in improvement in preliminary intervention rates from 7.5% to 42%, demonstrating good initial success. It also resulted in the team reviewing different implementation strategies than initially planned during the QI process. The CFIR-ERIC survey process could be adapted to other EDs interested in incorporating geriatric screening or interventions that deviate from standard operations. Further data on the effects of using a theory driven, targeted strategies approach will be reported upon completion of the ongoing research.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table S1: Geriatric Screening Tools Survey

Supplemental Table S2: Survey questions mapped to the CFIR domains

Supplemental Table S3: Original data file

Impact statement:

We certify that this work is novel research. While the data behind geriatric screening in Emergency Departments shows high levels of new diagnosis of unsafe mobility and delirium, dissemination of geriatric screening tools in EDs has been minimal. This paper uses validated implementation science tools to assess for barriers and facilitators of geriatric screening by surveying front line ED nurses and then demonstrates how to use the Expert Recommendations for Implementation Change tool to identify high yield implementation strategies to target multiple barriers. This article both provides the data from a single academic ED and also leads the reader through the basics of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research and the associated toolkits (survey development and implementation strategy matching guide) available at cfirguide.org.

Key Points:

Implementation of geriatric screening in the ED encountered many barriers.

The CFIR-ERIC tool identified high-impact implementation strategies.

Why does this paper matter?

An implementation framework guided geriatric screening implementation in the ED and identified barriers and targeted strategies missed by QI approaches.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Conflict of interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest. LTS and KBH are volunteer Geriatric ED Accreditation site reviewers through the American College of Emergency Physicians. LTS was funded by NIA K23AG061284. This study was also supported by The Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational grant support (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR001070. The funders had no role in the study design, interpretation of data, and writing of the report.

Sponsor’s role:

The sponsors (NIH) had no role in the design, methods, analysis and preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES:

- 1.American College of Emergency P, American Geriatrics S, Emergency Nurses A, Society for Academic Emergency M, Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines Task F. Geriatric emergency department guidelines. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(5):e7–25.24746437 [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Emergency Physicians GEDC. Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program: American College of Emergency Physicians; 2017. [Available from: https://www.acep.org/geda/#sm.0000h0eb9k15z2emhtnd9t8m2cloj.

- 3.Hwang U, Dresden SM, Vargas-Torres C, Kang R, Garrido MM, Loo G, et al. Association of a Geriatric Emergency Department Innovation Program With Cost Outcomes Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e2037334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy M LA, Israni J, Liu SW, Santangelo I, Tidwell N, Southerland LT, Carpenter CR, Biese K, Ahmad S and Hwang U. Reach and Adoption of a Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program in the United States. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2021;In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blomaard LC, Mooijaart SP, Bolt S, Lucke JA, de Gelder J, Booijen AM, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of the ‘Acutely Presenting Older Patient’ screener in routine emergency department care. Age Ageing. 2020;49(6):1034–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asomaning NaL C. Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) Screening Tool in the Emergency Department: Implementation Using the Plan-Do-Study-Act Model and Validation Results. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2014;40(4):357–64.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM. An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychol. 2015;3:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter CR, Pinnock H. StaRI Aims to Overcome Knowledge Translation Inertia: The Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies Guidelines. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1664–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, Albers B, Nilsen P, Broder-Fingert S, et al. Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keith RE, Crosson JC, O’Malley AS, Cromp D, Taylor EF. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: a rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sibbald SL, Van Asseldonk R, Cao PL, Law B. Lessons learned from inadequate implementation planning of team-based chronic disease management: implementation evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gesell SB, Golden SL, Limkakeng AT Jr., Carr CM, Matuskowitz A, Smith LM, et al. Implementation of the HEART Pathway: Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2018;17(4):191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolansky MA, Pohnert A, Ball S, McCormack M, Hughes R, Pino L. Pre-Implementation of the Age-Friendly Health Systems Evidence-Based 4Ms Framework in a Multi-State Convenient Care Practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2021;18(2):118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Southerland LT, Stephens JA, Carpenter CR, Mion LC, Moffatt-Bruce SD, Zachman A, et al. Study protocol for IMAGE: implementing multidisciplinary assessments for geriatric patients in an emergency department observation unit, a hybrid effectiveness/implementation study using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Southerland LT, Savage EL, Muska Duff K, Caterino JM, Bergados TR, Hunold KM, et al. Hospital costs and reimbursement model for a Geriatric Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shesser R, Ghassemi M, Sun E, Keim A, Marchak A, Pourmand A. Shifting attention to an undervalued asset; the emergency department technician. Am J Emerg Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Stark S, Coopersmith CM, Gage BF. Physician and nurse acceptance of technicians to screen for geriatric syndromes in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12(4):489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huded JM, Lee A, McQuown CM, Song S, Ascha MS, Kresevic DM, et al. Implementation of a geriatric emergency department program using a novel workforce. Am J Emerg Med. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Southerland LT, Lo AX, Biese K, Arendts G, Banerjee J, Hwang U, et al. Concepts in Practice: Geriatric Emergency Departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(2):162–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elder NM BK, Gregory ME, Gulker P, and Southerland LT. Are Geriatric Screening Tools Too Time Consuming for the Emergency Department? A Workflow Time Study. Journal of Geriatric Emergency Medicine. 2021;2(6). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desy PM, Prohaska TR. The Geriatric Emergency Nursing Education (GENE) course: an evaluation. J Emerg Nurs. 2008;34(5):396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han JH, Wilson A, Vasilevskis EE, Shintani A, Schnelle JF, Dittus RS, et al. Diagnosing delirium in older emergency department patients: validity and reliability of the delirium triage screen and the brief confusion assessment method. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(5):457–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Southerland LT, Slattery L, Rosenthal JA, Kegelmeyer D, Kloos A. Are triage questions sufficient to assign fall risk precautions in the ED? Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(2):329–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Trepanier S. Screening for geriatric problems in the emergency department: reliability and validity. Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) Steering Committee. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(9):883–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Southerland LT, Vargas AJ, Nagaraj L, Gure TR, Caterino JM. An Emergency Department Observation Unit Is a Feasible Setting for Multidisciplinary Geriatric Assessments in Compliance With the Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parks A, Eagles D, Ge Y, Stiell IG, Cheung WJ. Barriers and enablers that influence guideline-based care of geriatric fall patients presenting to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(12):741–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy SO, Barth BE, Carlton EF, Gleason M, Cannon CM. Does an ED flow coordinator improve patient throughput? J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(6):605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpenter CR, Sherbino J. How does an “opinion leader” influence my practice? CJEM. 2010;12(5):431–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O’Brien MA, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(2):CD003030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frykman M, Hasson H, Athlin AM, von Thiele Schwarz U. Functions of behavior change interventions when implementing multi-professional teamwork at an emergency department: a comparative case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carpenter CR, Neta G, Glasgow RE, Rabin BA, Brownson RC. Carpenter et al. respond. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delaforce A, Duff J, Munday J, Hardy J. Preoperative Anemia and Iron Deficiency Screening, Evaluation and Management: Barrier Identification and Implementation Strategy Mapping. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:1759–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Oers HA, Teela L, Schepers SA, Grootenhuis MA, Haverman L, PROMs I, et al. A retrospective assessment of the KLIK PROM portal implementation using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Qual Life Res. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table S1: Geriatric Screening Tools Survey

Supplemental Table S2: Survey questions mapped to the CFIR domains

Supplemental Table S3: Original data file