Abstract

Our previous matched case-control study of postmenopausal women with resected early stage breast cancer revealed that only anastrozole, but not exemestane or letrozole, showed a significant association between the six-month estrogen concentrations and risk of breast cancer event. Anastrozole, but not exemestane or letrozole, is a ligand for estrogen receptor α (ERα). The mechanisms of endocrine resistance are heterogenous and with the new mechanism of anastrozole, we have found that treatment of anastrozole maintains fatty acid synthase (FASN) protein level by limiting the ubiquitin-mediated FASN degradation, leading to increased breast cancer cell growth. Mechanistically, anastrozole decreases guided entry of tail-anchored proteins factor 4 (GET4) expression, resulting in decreased BCL2-associated athanogene cochaperone 6 (BAG6) complex activity, which in turn, prevents RNF126-mediated degradation of FASN. Increased FASN protein level can induce a negative feedback loop mediated by the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. High levels of FASN are associated with poor outcome only in anastrozole-treated breast cancer patients, but not in patients treated with exemestane or letrozole. Repressing FASN causes regression of breast cancer cell growth. The anastrozole-FASN signaling pathway is eminently targetable in endocrine-resistant breast cancer.

Introduction

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs), anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole, are first-line therapy for postmenopausal women with estrogen-dependent breast cancer (1–4). These agents block the biosynthesis of estrogen through the inhibition of aromatase activity and, in turn, inhibit the proliferation of estrogen-dependent breast tumors. Despite the worldwide use of AIs as adjuvant treatment for postmenopausal women with ER-positive (ER+) breast cancer, cancer recurs in 30% of AIs-treated patients (5–7). In these AI-resistant tumors, ERα is either hypersensitive to low levels of estrogens (8) in a ligand-independent manner through activation of growth signaling, or by acquired somatic ESR1 mutations (9,10) (11,12). Thus, it is crucial to identify molecular mechanisms of recurrence/resistance to improve the success of endocrine therapies and, therefore, prevent breast cancer mortality.

Currently, anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole are considered interchangeable and equal in efficacy when administered as adjuvant therapy in early-stage breast cancer. This position is based on two large phase III clinical trials. The first trial, MA.27, randomized 7,576 postmenopausal women to anastrozole or exemestane and found similar outcomes for the two AIs in terms of event-free survival, distant disease–free survival and disease-specific survival (3). The second trial, Letrozole (Femara) Versus Anastrozole Clinical Evaluation (FACE) study, randomized 4,136 postmenopausal women to letrozole or anastrozole, and found similar outcomes for the two AIs in terms of disease-free survival and overall survival (13). Despite the apparent similarity of the three AIs in outcomes from these adjuvant trials, we identified biomarkers [estrone (E1) and estradiol (E2)] that were associated with efficacy of anastrozole but not exemestane or letrozole. We performed a matched case-control study of postmenopausal women with resected early-stage breast cancer treated with anastrozole, exemestane or letrozole adjuvant therapy that revealed woman who, after six months of AI therapy had an E1 >1.3 pg/mL and an E2 >0.5 pg/mL had a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 2.2-fold increased risk of an early breast cancer event (EBCE) compared to a woman with the same matching characteristics but who had an E1 and/or E2 below these respective thresholds (14). An EBCE was used as the primary outcome to indicate any of the following: local–regional breast cancer recurrence (including ipsilateral Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)), distant breast cancer recurrence, contralateral breast cancer (invasive or DCIS), or death with or from breast cancer without prior recurrence within five years of randomization. Importantly, when the three AIs were examined individually, however, only anastrozole showed a significant association between the six-month E1 and E2 concentrations and risk of an EBCE. That is, for women with E1 and E2 concentrations at or above their respective threshold after six months of anastrozole, the risk of an EBCE was increased 3.0-fold (14). We also have identified novel common genetic variants associated with estrogen suppression and breast cancer events in women treated with adjuvant AI therapy in which the variant allele increased sensitivity to anastrozole, but not letrozole or exemestane (15). Mechanistically, anastrozole, but not letrozole or exemestane, has a secondary mechanism of action, that is, anastrozole acts as a ERα agonist to activate ERE-dependent transcription (14). Therefore, anastrozole-driven transcriptional programs may provide valuable clues for understanding anastrozole-specific resistance.

Recent studies have revealed that lipid metabolism-related traits can be key drivers to endocrine resistance. Overexpression of fatty acid synthase (FASN) in breast cancer has been associated with significantly shorter disease-free survival and overall survival (16) (17–19). FASN is the major enzyme of lipogenesis that catalyzes the NADPH-dependent condensation of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA to produce free palmitic acid (17). The molecular link between FASN and HER2 oncogene has been partially characterized (20). Pharmacological FASN inhibitors were found to suppress HER2 expression, and the simultaneous targeting of FASN and HER2 was synergistically cytotoxic (20). However, the role of FASN in driving ER+/HER2- breast cancer resistance to endocrine therapies remains unknown.

This study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that increased FASN activity plays an active role in anastrozole resistance. We demonstrate that anastrozole, through its binding to ER, directly represses gene transcription that is responsible for FASN protein degradation in breast cancer cells. We further show that increased FASN protein activates ERα, negatively affecting its own expression. Further understanding of the regulatory dynamics by which anastrozole controls lipid metabolism should aid the development of novel therapies that may target not only FASN itself but also genes involved in FASN regulation.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Human breast cancer cell lines,T47D, MCF7, BT549, HS578T, and human 293T (ATCC Cat# CRL-3216, RRID:CVCL_0063) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. The identities of all cell lines were confirmed by the medical genome facility at Mayo Clinic using short tandem repeat profiling upon receipt. Mycoplasma tests were performed using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, LT07–318). Cells were passaged <20 times. The anastrozole resistant MCF7/AnaR cells were obtained from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (15).

Drug-related enrichment analysis and pathway enrichment analysis

To explore whether identified genes were enriched in gene sets related to biological phenotypes or drug mechanisms of action, we utilized the web-based tool of WebGestalt (21) to perform functional enrichment analysis based on the resources of GLAD4U (22) and Wikipathway (21). The enrichment analysis utilized all genome protein-coding genes as the background genes.

Cell proliferation assays

Cell proliferation analysis was performed as described previously (15). Briefly, 2000 cells/well were plated in 96 well plates in triplicate, followed by different treatments for the indicated time. The cell proliferation rate was assessed using CyQUANT proliferation kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at 480 and 650 nm was measured using a TECAN plate reader. The relative cell proliferation rate at each time point was determined relative to time zero.

FASN activity assay

Following exposure to AIs and/or FASN inhibitors, cells were harvested, sonicated at 4°C and centrifuged to obtain supernatants. FASN activity was determined by measuring the decrease of absorption at 340 nm due to the oxidation of NADPH. 20 μl supernatant, 25 mM KH2PO4-K2HPO4, 0.25 mM EDTA, 0.25 mM dithiothreitol, 30 μM acetyl-CoA and 350 μM NADPH (pH 7.0) in a total volume of 200 μl were monitored at 340 nm for 5 min to measure background NADPH oxidation. Following the addition of 100 μM of malonyl-CoA, the reaction was assayed to determine FASN-dependent oxidation of NADPH at 340 nm.

Free fatty acid (FFA) quantification assay

Following indicated treatment, cells were harvested and washed with PBS. Intracellular FFA levels were measured using a FFA Quantification Colorimetric kit (BioVision) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were measured against a standard of varying concentrations of palmitic acid (PA) and the optical density was measured at 570 nm in a Tecan plate reader. The levels of FFA were calculated using the slope of the standard curve.

Organoid derivation, 3D culture and growth assay

Organoids were derived using the human Tumor Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) from the ER+ patient derived xenografts from the Breast Cancer Genome Guided Therapy Study according to a previously described protocol (15). Organoids were cultured in 96-well low binding NanoCulture plate (Organogenix) in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% glutamax, 1% sodium pyruvate, non-essential amino acids, and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Life Technologies) at 37°C, 5% CO2. Organoid growth was measured as previously described (15) using the CellTiter-Glo Viability assay (Promega).

Mass spectrometry

T47D cells were starved in a culture medium with 5% charcoal stripped FBS for 48 hours. Cells were then treated with anastrozole or estrodiol (E2) overnight. Proteins were extracted using NETN buffer. ERα was immunoprecipitated with ERα antibody (Diagenode) and performed mass spectrometry to identify ERα interacting proteins by the Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility (Harvard Medical School).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing and data analysis

ChIPseq experiments were performed in duplicate using T47D cells (ATCC Cat# HTB-133, RRID:CVCL_0553). Cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde and the reaction was quenched with 0.125 M glycine. ChIP reaction was done using 5 μg ERα antibody (Diagenode) and chromatin input generated from 2×107 cells. ChIPseq libraries were prepared from 3~10 ng ChIP and input DNA using the ThruPLEX DNA-seq Kit V2 (Rubicon Genomics). The libraries were sequenced to 51 base pairs from both ends on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 instrument in the Mayo Clinic Medical Genomics Facility. The Fastq files were aligned against the UCSC human reference genome (hg19) with Bowtie 1.1.0 (Bowtie, RRID:SCR_005476) using the following Bowtie parameters: −sam−chunkmbs 512−p4−k1−m 1−e70−l51−best.

ChIP and ChIP-re-ChIP assays

ChIP assays were performed using the EpiTect ChIP kit (Qiagen) as previously described (15). 2×106 cells per sample were collected for the ChIP assay. DNA-ERα complexes were immunoprecipitated using ERα antibody or normal mouse IgG. ChIP-re-ChIP assays were performed using the Re-ChIP-IT Kit (Active Motif). qPCR was used to quantify the bindings. The primer sets for the ChIP assays are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Ubiquitination assays

Approximately 1.5 μg HA-ubiquitin, 1.5 μg FLAG-FASN, wild type or mutant RNF126 plasmids (Genscript) were co-transfected in HEK 293T cells using the Lipofectamine 2000. After 64 h, 10 μM MG132 was added for 8 hours. Cells were then collected for the ubiquitination assay as previously described (23). Immunoprecipitation was performed with FLAG antibody conjugated beads. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blotting.

Rapid immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins for analysis of chromatin complexes

Chromatin complex was analyzed based on the protocol described previously (24). Briefly, ERα antibody conjugated to protein A beads. 10×107 cells were cross-link in 1% formaldehyde, followed by quenching with 0.1 M glycine. Cells were then lysated with 10ml lysis buffer 1. The enriched nuclear material was collected by centrifugation and suspended in 10 ml lysis buffer 2. The lysate was then cleared by centrifugation and ~2×107 cell nuclei was resuspended in 300 μl lysis buffer 3. The mixture was sonicated using a 30s on/off cycle for 10 min. 30 μl of 10% Triton X-100 was added, followed by centrifugation. Antibody-bound beads (100 ul) were added to the supernatant, incubated overnight, followed by washing with in RIPA buffer. Recipes for all buffer were described in Supplementary Materials. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blotting.

Luciferase activity assay

ERα transcription activity was measured using the dual luciferase assay with the Cignal ERE Reporter Assay Kit (Qiagen) as described previously (14,15). Cells were transfected with indicated plasmid and siRNA, and went through treatment for 24h. Luciferase assay was performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

FASN reporter gene assay

Luciferase reporter gene constructs containing FASN promoter were generated by gene synthesis. Specifically, a 900 bp segment of the FASN promoter containing ERE was synthesized and cloned into the Kpnl and Xhol sites upstream of the luc2 gene in the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). Cells were transfected with reporter gene constructs and pRL-CMV vector (Promega), and treated with AIs for 24h. Luciferase activity was determined using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay system. The renilla luciferase activity was used to correct for the transfection efficiency.

Clinical outcome analysis

Microarray expression and clinical data of AIs treated breast cancer cohort was downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (RRID:SCR_005012) accession number GSE41994 (25). Samples with ER+ or PR+ and HER2- treated with one of the AIs, and with outcome data were included (n=80) in the study. The poor, medium and good outcome were as defined as time to progression <12 months, between 12 and 24 months, and >24months, respectively, as in the original publication (25). Statistical significance was tested using the Mann-Whitney’s test.

Statistical Analysis

For cell survival, proliferation, gene expression, and quantifications, data were represented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed with 2-way ANOVA. Statistical significance is represented by: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available within the article and its supplementary data files.

Results

Anastrozole regulates the fatty acid biosynthesis pathway

Since anastrozole can function as an ERα ligand, we performed RNAseq to investigate anastrozole mediated downstream signaling using ER+ T47D breast cancer cells treated with anastrozole or E2 (15). To explore anastrozole-specific mechanism, we used the anastrozole regulated genes for pathway analysis. Wikipathway enrichment analysis indicated that hub genes were mainly enriched in cholesterol metabolism, cholesterol biosynthesis, lipid metabolism, and fatty acid biosynthesis pathways (Fig. 1A), suggesting anastrozole may play important roles in regulating these pathways. These anastrozole regulated genes and pathways might help us to better understand anastrozole resistance since dysregulation of these pathways might cause resistance. To further identify additional treatment regimen that might target the anastrozole regulated genes to mitigate anastrozole resistance, we utilized the WebGestalt (21) software to conduct drug-based enrichment analysis. For drug-focused enrichment analysis, 10 gene sets related to drugs were significantly enriched based on the GLAD4U database (Fig. 1A). GLAD4U derives gene lists from PubMed literature to create gene sets related to the drug targets and mechanisms, and thus, the drug association analysis can only suggest that the anastrozole regulated genes enriched in the 10 drug related gene sets. We, therefore, tested whether these identified drugs impact breast cancer cell growth in both treatment naïve (MCF7, T47D) and anastrozole resistant (MCF7/AnaR) (15) settings. FASN inhibition by cerulenin, a specific FASN inhibitor, resulted in significant growth inhibition (Fig. 1C–D, Fig. S1A), while sparing the non-transformed breast epithelial MCF10A cells (Fig. S1B). We further validated the effect of FASN inhibition on ER+ breast cancer cell growth using a second FASN inhibitor, C75 (26) (Fig. 1C–D). FASN catalyzes the terminal steps in the synthesis of long-chain saturated fatty acids. The production of fatty acids supports the membrane synthesis in proliferating cells (27). Both cerulenin and C75 inhibited the growth of anastrozole-resistant cells in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2A–B), even in the presence of anastrozole or E2 (Fig. S1 C–D). Furthermore, FASN knockdown MCF7/AnaR cells exhibited reduced growth compared with the scrambled siRNA control (Fig. 2C). To prove the specificity of the FASN inhibitor, we hypothesized that supplementation with palmitic acid (PA), the final product of FASN catalyzed synthesis, could reverse the growth phenotype. Indeed, as shown in Figure 2D–E, the addition of PA reversed the growth inhibition by cerulenin or C75. These results suggest that FASN plays a critical role in anastrozole resistance and ER+ breast cancer cell growth.

Figure 1.

Anastrozole regulates fatty acid biosynthesis pathway. (A) Pathway enrichment analysis based on the Wikipathway database. (B) Drug-based enrichment analysis using the GLAD4U database based on the WebGestalt. (C-D) Selected drug effects on cell growth in the MCF7 and MCF7/AnaR breast cancer cells. (vehicle vs cerulenin: p<0.0001). Error bars (C-D) represent the SEM of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01. Statistical test: 2-way ANOVA plus Tukey.

Figure 2.

The effect of FASN on cell growth in anastrozole resistant breast cancer cells. (A-B) The effects of FASN inhibitors, cerulenin or C75, on MCF7/AnaR cell growth. The cells were incubated with 1.5, 2, 4, and 5 μg/ml cerulenin (A) or C75 (B) for indicated time. (vehicle vs various FASN inhibitor concentration). (C) Cell growth of MCF7/AnaR cells after knocking down FASN in the presence or absence of 100 nM anastrozole. Scramble siRNA as negative control (Neg) (Neg vs siFASN: p<0.0001; Neg Ana vs siFASN Ana: p<0.0001) (D) Palmitic acid (PA) could rescue the inhibitory effects of cerulenin on MCF7/AnaR cell growth. The cells were incubated with 100 nM anastrozole, 2 μg/ml cerulenin, in the presence or absence of 50 μM PA for indicated time. (ceru vs ceru+PA: p<0.0001; Ana+ceru vs Ana+ceru+PA: p<0.0001). (E) PA could rescue the inhibitory effects of C75 on MCF7/AnaR cell growth. The cells were incubated with 100 nM anastrozole, 2 μg/ml C75, in the presence or absence of 50 μM PA for indicated time. (C75 vs C75+PA: p<0.0001; Ana+C75 vs Ana+C75+PA: p<0.0001). (F) Anastrozole decreased FASN mRNA and increased FASN protein levels in MCF7/AnaR cells. Cells were treated with 1,10, and 100nM anastrozole or 0.1, 1, 10nM E2 for 12, 24, and 48 hours. Error bars represent the SEM of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01. Statistical test: 2-way ANOVA plus Tukey.

Anastrozole - induced FASN mRNA and protein expression changes

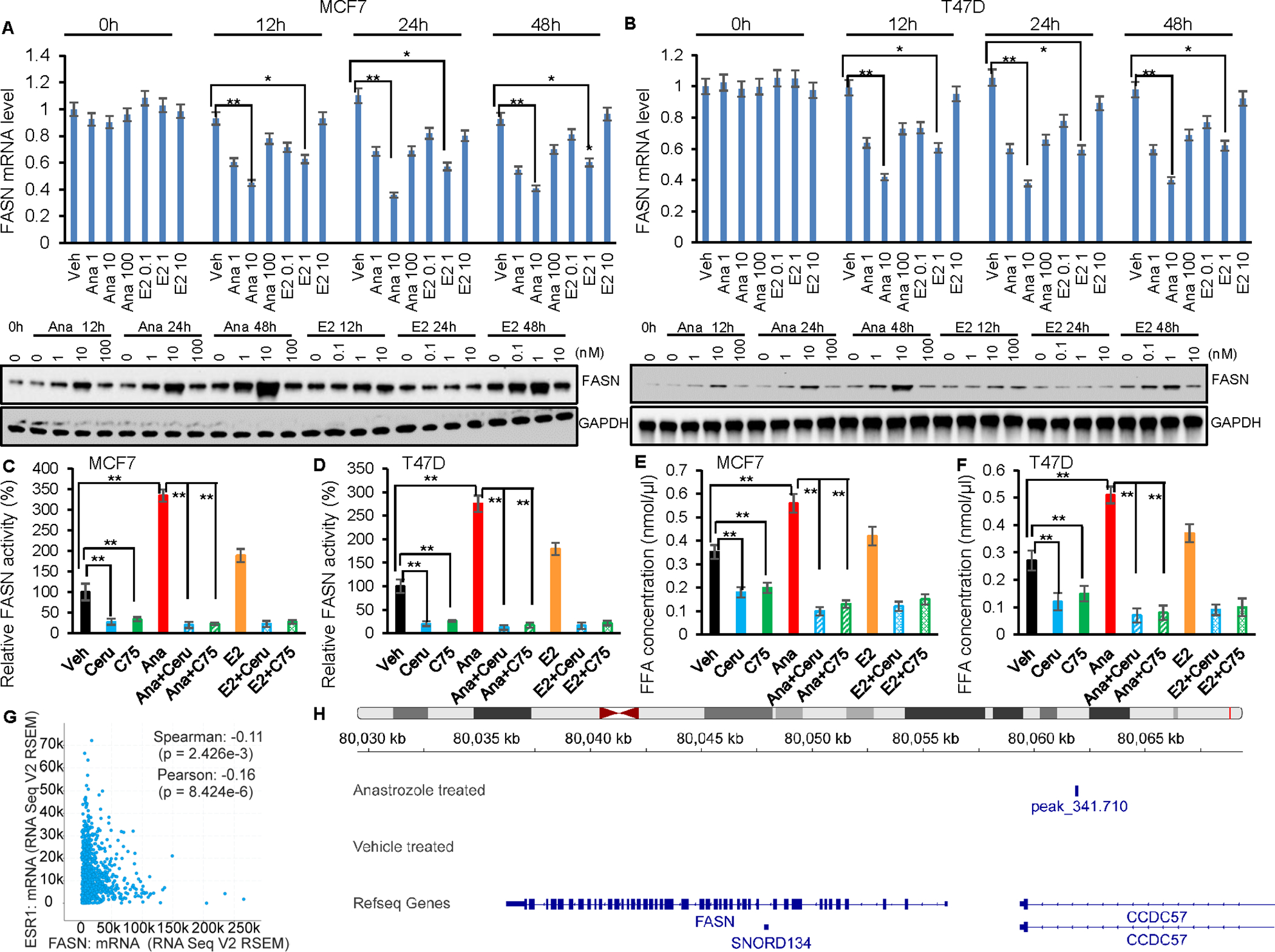

We next determined the possible effect of anastrozole on FASN expression in ER+ breast cancer cells. Dose effect study demonstrated that FASN mRNA expression was significantly downregulated after 100 nM anastrozole exposure in MCF7/AnaR cells (Fig. 2F) or 10nM anastrozole exposure in MCF7 and T47D cells (Fig. 3A–B). In parallel, the ERα natural ligand, E2 (1nM), also reduced, to a lesser degree, FASN mRNA level. These anastrozole concentrations fall within the range of the plasma drug levels observed in postmenopausal patients with ER+ breast cancer, and exhibits strong ERα agonist activity in our previous study (14). Strikingly, and somewhat surprisingly, FASN protein levels in these cells were upregulated in the presence of anastrozole (100 nM in MCF7/AnaR, 10nM in MCF7 and T47D), while to a lesser degree in the presence of E2 (Fig. 2F, Fig. 3A–B). It is noticeable that MCF7/AnaR cells required higher dose of anastrozole in regulating FASN compared to treatment naïve cells (T47D and MCF7), as will become clear subsequently, anastrozole regulates FASN via ERα, and MCF7/AnaR cells express less ERα compared to parental cells and are less sensitive to anastrozole treatment (15), which might explain this concentration difference. The most significant increase in FASN protein was observed at 48 hours following anastrozole treatment. We should point out that the absence of correlation between mRNA and protein levels occurs frequently (28–30). The differential expression of mRNA can capture at most 40% of the variation of protein expression in mammalian cells (31). The discordance between the mRNA and protein levels emphasizes the importance of integrated analyses of both proteins and mRNAs. To confirm the regulation of FASN by anastrozole translates into modulation of fatty acid or other lipid metabolites, the cells were incubated with AIs, E2, or FASN inhibitors for 24 h to evaluate cellular FASN activity. Anastrozole increased cellular FASN activity in MCF7 and T47D cells to 289.2% and 334.6% respectively, while E2, to a lesser degree, also increased FASN activity (Fig. 3C–D). Cerulenin and C75, as control modulators for FASN activity, reduced FASN activity, even in the presence of anastrozole (Fig. 3C–D). The upregulation of FASN in several types of cancer markedly induces de novo lipogenesis, including phospholipids, which are necessary for de novo synthesis of the cell membrane (32). Thus, inhibiting FASN can reduce the levels of phospholipids and free fatty acids (FFA) required. We measured FFA as the primary function of FASN is to catalyze long-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. Anastrozole treatment increased intracellular FFA level in MCF7 and T47D cells (Fig. 3E–F). The anastrozole-induced FASN activities can be abolished by the addition of cerulenin or C75. These results indicated that anastrozole promoted FASN function. Given the discrepancy between the changes in FASN mRNA and protein level upon anastrozole treatment, we hypothesized that FASN mRNA and protein level might be regulated by anastrozole through different mechanisms, respectively.

Figure 3.

Anastrozole regulates FASN mRNA and protein expression. (A-B) Anastrozole decreased FASN mRNA and increased FASN protein levels in MCF7 (A) and T47D (B) cells. Cells were treated with 1,10, and 100nM anastrozole or 0.1, 1, 10nM E2 for 12, 24, and 48 hours. (C-D) Induction of FASN by anastrozole or E2 were measured in MCF7 (C) and T47D (D). Relative FASN activity was measured spectrophotometically by monitoring oxidation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate at 340 nm. Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate determinations. *p<0.05, vs. vehicle control. (E-F) Intracellular free fatty acid (FFA) levels in MCF7 (E) and T47D (F) cells were detected following treatment with 10nM anastrozole, 1nM E2 and/or cerulenin, C75. FFA concentration (nmol/μl) is presented as the mean + standard deviation of triplicate determinations. *p<0.05, vs. control. Cerulenin was used as the positive control. (G) FASN and ESR1 mRNA were negatively correlated in TCGA ER+ breast cancer patients. (H) ERα CHIPseq peaks near FASN gene region in the presence of anastrozole. Error bars (A-B) represent SEM of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01. Statistical test: 2-way ANOVA plus Tukey.

Anastrozole ERα - mediated FASN transcriptional regulation

The next series of experiments was performed to determine the underlying mechanism of anastrozole-mediated FASN transcriptional regulation. Our previous studies indicated that anastrozole is different from letrozole or exemestane by possessing a second mechanism of action, being an ERα agonist in a similar fashion to E2 (14). It can activate ERα-dependent transcription (14). Interestingly, neither letrozole nor exemestane altered FASN levels and activities (Fig. S2A–F). More importantly, anastrozole did not affect FASN levels or activities in ER negative BT549 and HS578T breast cancer cells (Fig. S3A–F). This series of findings led us to ask whether anastrozole might regulate FASN gene transcription through ERα signaling, which was supported by a modest but significant correlation between the expressions of these two genes (Fig. 3G). Our genome-wide ChIPseq performed in T47D cells treated with anastrozole identified ERα binding peak near the FASN gene (Fig. 3H, Fig. S4A), indicating a direct anastrozole-ERα dependent transcription regulation. We identified four estrogen response elements (EREs) in FASN promoter region based on the ENCODE data, as shown schematically in Figure 4A. ChIP assays demonstrated that ERα bound to all four binding sites in the presence of anastrozole in MCF7 cells, resulting in decreased FASN mRNA level (Fig. 4B), suggesting a repressive regulation. In addition, anastrozole could also induce ERα recruitment to two of the EREs in T47D cells (Fig. 4C), a slightly different phenotype from that observed in MCF7, which might be due to the cell line specific difference in transcription machinery. Although ERα served as a transcription factor for FASN, E2 only induced a modest ERα-ERE binding in the FASN promoter region (Fig. 4B–C), which might explain the observation of lesser E2 effect on FASN expression level (Fig. 3A–B), while neither letrozole nor exemestane induced ERα binding to any of these ERE sites (Fig. S4B). The next series of studies were designed to characterize ERα coregulators involved in anastrozole-ERα mediated FASN transcriptional regulation.

Figure 4.

Anastrozole mediated FASN mRNA regulation. (A) Schematic figure showing EREs in the FASN promoter region. Primers 1, 2, 3, and 4 were used in the ChIP assays to determine the regions around the four EREs. (B-C) ERα ChIP assay showed ERα binding to the ERE in the presence of 10nM anastrozole (Ana) and 1nM estradiol (E2). (D) ERα-interacting proteins in T47D cells in the presence of anastrozole or E2 by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS). (E) FASN mRNA levels after knocking down candidate cofactors. Cells were transfected with each siRNA respectively for 24 hours. FASN mRNA was measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH. (F) ERα binding partners on chromatin in the presence of anastrozole (Ana) and estradiol (E2) using the rapid immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins for analysis of chromatin complexes. (G-H) Cofactors involved in anastrozole mediated FASN transcription regulation. ChIP-re-ChIP assays of NONO (G) and P53 (H) were performed in T47D cells to confirm the co-occupancy of ERα with NONO and P53 on the selected binding regions in FASN gene as shown in Fig. 4A in the presence of anastrozole (Ana) and estradiol (E2). Error bars (B, C, E, G, H) represent SEM of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01. Statistical test: 2-way ANOVA plus Tukey.

Cofactors involved in anastrozole - ERα mediated FASN transcriptional regulation

It is known that the crosstalk between ERα and other transcription factors can promote ERα target gene expression regulation (33,34). To identify cofactors involved in ERα mediated FASN transcription repression, ERα immunoprecipitation followed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry was conducted to identify ERα interacting proteins in T47D cells in the presence of anastrozole or E2 (Table S2). As both anastrozole and E2 reduced FASN mRNA levels, 97 common proteins shared between the two treatments were identified (Table S2, Fig. 4D) and 10 out of the 97 proteins were known transcription cofactors. Included among these proteins were HDAC3, SETDB1, SFPQ, PSPC1, ANP32E, TP53, SET, NONO, DDX17, GTF3C3, HSPA4 and SND1. We then asked whether any of these transcription cofactors, together with ERα might be involved in FASN transcription regulation. siRNA knocking down followed by qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that knocking down of HDAC3, DDX17, SETDB1, SFPQ, NONO, SET, TP53, GTF3C3, and HSPA4 increased FASN mRNA levels, while these cofactors did not regulate each other (Fig. 4E, Fig. S4C). The chromatin-bound interaction complex of ERα was defined using rapid immunoprecipitation of endogenous proteins (RIME) (35),(24), and NONO, HDAC3, and TP53 were associated with ERα in nuclear foci on chromatin at baseline and the associations for all three cofactors also increased in the presence of anastrozole and E2, but not letrozole or exemestane (Fig. 4F, Fig. S5A). We next determined whether NONO, HDAC3, or TP53 associated with ERα, targeting the regulatory regions of the FASN gene by ChIP-re-ChIP assay. As shown in Figure 4G, ERα and NONO co-occupied the same sites on FASN, based on the results of ChIP-re-ChIP assays performed using an antibody against ERα, followed by antibody against NONO for two regions containing ERE that were assessed by two primer sets. Even more striking, the binding of ERα and NONO significantly increased at both regions upon anastrozole treatment, but not letrozole or exemestane (Fig. 4G, Fig. S5B). Similar results were also observed for ERα and P53, which co-occupied the same sites on the FASN gene, especially in the presence of anastrozole (Fig. 4H, Fig. S5B). ERα and HDAC3, however, occupied the same sites at the baseline, and this binding was not increased with anastrozole or E2 treatment, suggesting that HDAC3 only involved in FASN gene transcription at baseline. Taken as a whole, these results supported the conclusion that an ERα, NONO and/or P53 protein complex might play an important role in anastrozole-dependent FASN transcription regulation.

Anastrozole - ERα mediated FASN protein regulation

FASN mRNA and protein level changed in the opposite direction in response to anastrozole (Fig. 3A–B). To pursue these observations, we began by determining whether anastrozole might affect FASN protein stability mediated by protein degradation. We merged RNAseq and ChIPseq data by overlapping the results for genes whose expression levels were altered upon anastrozole treatment through the anastrozole-ERα transcription regulation (Table S3). Expression of 31 genes could be regulated by anastrozole, and displayed significantly increased genomic binding of ERα in the presence of anastrozole (Fig. 5A). Ten out of the 31 genes have been implicated in protein degradation based on their functions. Included among these proteins were CUEDC1, EPS15L1, PIP, FKBP4, GET4, HSPB1, OLFML3, PSMC3, SPDEF, and SPINK5. To gain further insights into the molecular mechanisms governing FASN protein regulation by anastrozole, we first determined the effects of these 10 genes on FASN protein level in ER+ breast cancer cells. FASN protein levels increased with CUEDC1, EPS15L1, PIP, FKBP4, and GET4 knockdown respectively (Fig. 5B, Fig. S5C). Among this group of proteins, only GET4 expression level showed a significant change in response to anastrozole (Fig. 5C, Fig. S5D), suggesting its involvement in the anastrozole–mediated FASN protein regulation. ChIPseq showed that ERα bound to the GET4 gene region in the presence of anastrozole, and we confirmed this observation by ChIP-qPCR with primers designed to amplify the genomic region for the ERα binding sites in the GET4 gene (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Anastrozole-mediated FASN protein regulation. (A) Venn diagram showing 31 genes that displayed anastrozole-dependent gene expression as determined by RNA-seq, displayed anastrozole-dependent ERα occupancy as determined by CHIP-seq. (B) Western blot analysis of endogenous FASN protein levels after knockdown protein degradation related candidate genes in T47D cells. (C) GET mRNA level in response to 10nM anastrozole (Ana), 10nM letrozole (Let), or 10nM exemestane (Exe) treatment in T47D cells. (D) ERα ChIP assay that show anastrozole-dependent ERα binding to the ERE in GET gene region. (E) Upper panel: RNF126 mRNA level in response to 10nM anastrozole (Ana) in T47D and MCF7 cells. Lower panel: endogenous FASN protein level after knocking down RNF126 in T47D and MCF7 cells. (F) The endogenous interaction between FASN, GET4, BAG6, and RNF126 using immunoprecipitation, followed by Western blot analysis with indicated antibodies. (G) RNF126 ubiquitinates FASN in an E3 ligase activity-dependent manner. Wild-type or RING domain mutated (C229/232A) RNF126, Flag-FASN, and HA-Ub were expressed in 293T cells. MG132 were added to the cells before harvest to prevent FASN degradation. Flag-FASN was immunoprecipitated and ubiquitinated FASN was detected by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody. Error bars (C-E) represent SEM of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01. Statistical test: 2-way ANOVA.

GET4 is part of the heterotrimeric BCL2-associated athanogene cochaperone 6 (BAG6) complex that plays a central role in membrane protein quality control (36,37). The BAG6 complex directs substrates (such as the tail-anchor proteins) to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane or to degradation by recruiting the E3 ligase, RNF126, followed by subsequent proteasome mediated degradation (36,38,39). We examined whether RNF126 acted as an E3 ligase for FASN in cells, and observed that FASN was dramatically upregulated by RNF126 siRNAs in both T47D and MCF7 cells (Fig. 5E), suggesting that RNF126 may target FASN for degradation. Anastrozole did not change RNF126 expression level (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, BAG6, GET, and RNF126 were co‐precipitated by FASN pull‐down in T47D cells (Fig. 5F upper panel), while endogenous FASN protein was co‐precipitated by GET4 pull‐down (Fig. 5F lower panel). Collectively, these results suggest that the BAG6 complex associates with FASN protein. To test whether RNF126 ubiquitinates FASN, we overexpressed Flag-FASN, HA-Ub, and wild type (WT) RNF126 or catalytic inactive RNF126-C229/232A in HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitated Flag-FASN. The ubiquitination of FASN was increased by WT RNF126 but not by catalytic inactive RNF126 (Fig. 5G). These results imply that RNF126 promotes ubiquitin-mediated FASN degradation.

A novel feedback loop involving FASN/MAPK/ERα

Given several studies revealed that FASN can activate MAPK signaling (40), in turn activate ERα (41) (23) (42), we speculated that anastrozole might regulate FASN mRNA level through FASN-MAPK-ERα dependent negative feedback in breast cancer cells. Indeed, knockdown of FASN decreased MAPK signaling reflected by decreased pERK level (Fig. 6A). These observations were paralleled by the observation that FASN overexpression induced MAPK activity, leading to ERα dependent transcriptional activation (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, the induction of ERα luciferase activity by FASN in the presence of anastrozole was lost after ERK knockdown (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Feedback loop of FASN/MAPK/ERα. (A) FASN activates MAPK signaling. T47D and MCF7 cells were transfected with indicated siRNA, and phospho-ERK was analyzed. (B) ERE dependent-luciferase assay in response to anastrozole (Ana) in MCF7 and T47D cells transfected with FASN plasmid with or without siERK. Overexpression or knockdown efficiency was indicated by western blots. (C) Reporter gene assays for the FASN promoter containing the EREs. FASN promotor was subcloned upstream of the luciferase reporter gene. Cells were transfected with the luciferase constructs together with scrambled siRNA (Neg) or siERK, and then treated with anastrozole. Values shown are ratios of relative light units (RLUs) compared with the internal reference. (D) FASN expression in GSE41994 (probe A_23_P44132) by categorized progression free interval (PFI), defined as good (>24months), medium (12–24months), and poor (<12months). ER+/HER2- samples received neoadjuvant anastrozole. (Good: n=9, Medium: n=4, Poor: n=11). Statistical significance was tested by Mann-Whitney’s test. (E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of PFI based on median separated FASN expression. P-value of Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test is indicated and number of patients in each risk group is indicated below the figures. (F) Upper panel: FASN protein levels in MCF7 and MCF7/AnaR cells. Lower panel: MCF7/AnaR cells were more sensitive to cerulenin compared to MCF7 cells (p<0.01). (G) Organoid growth curves in the presence of 10nM anastrozole and/or 2 μg/ml cerulenin or 2 μg/ml C75. (H) Hypothetical model illustrated how anastrozole might regulate FASN transcription and protein degradation. Anastrozole induces the recruitment of ERα to the functional EREs in GET4 promoter region, resulting in transcriptional repression of GET4. The decrease in GET4 reduces FASN protein proteasomal degradation mediated by the BAG6 complex and ubiquitin ligase RNF126, resulting in accumulation of FASN protein. As a feedback loop, FASN protein further activates ERα via MAPK signaling, leading to the down-regulation of FASN mRNA by ERα/NONO/P53 complex. Error bars (B-C, F) represent SEM of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05; **p< 0.01. Statistical test: 2-way ANOVA.

To examine whether this regulation has a negative feedback loop that acts on FASN transcription, we created a reporter construct for the FASN gene that included the functional EREs present in its promoter, as shown schematically in Figure 4A. Anastrozole induced transcriptional activity of the FASN reporter gene construct (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the induction of the luciferase activity by anastrozole was lost after ERK knockdown (Fig. 6C). These data indicated that FASN/MAPK activates the ERα signaling, which in turn suppresses FASN transcription.

FASN predicts clinical outcome in anastrozole - resistant breast cancer patients

To examine if FASN can be predictive of endocrine resistance in breast cancer, we examined FASN expression in AI treated ER+ breast cancer patients (n = 84) from the GSE41994 data set (25). We found a statistically significant association between higher FASN expression and shorter progression-free interval (PFI) in the entire cohort (Fig. S6A–B). More importantly, the association only existed in anastrozole-treated patients (Fig. 6D–E), but not in exemestane (Fig. S6C) or letrozole treated patients (Fig. S6D). In addition, FASN protein level was strikingly upregulated in anastrozole-resistant breast cancer cells (Fig. 6F, upper panel), and the resistant cells were more sensitive to FASN inhibitor (Fig. 6F, lower panel). We also noticed that the feedback loop regulating FASN mRNA was disrupted after long term anastrozole treatment using the anastrozole-resistant MCF7/AnaR cells, in which the FASN mRNA slightly increased compared to MCF7 cells (Fig. S6E). We further confirmed the increase in FASN protein level upon anastrozole treatment in ER+ breast cancer patient derived organoids, and FASN inhibition successfully slowed down organoid growth (Fig. 6G). These results further support our hypothesis that the anastrozole– ERα–GET4–FASN signaling is associated with anastrozole resistance.

Discussion

ER-targeted therapy such as AIs is effective in treating ERα+ breast cancer in postmenopausal women (43). However, long-term endocrine treatment often leads to resistance in breast cancer. Our previous studies have established the potential differences among the third-generation AIs, given the differences in individual genetic background, and the secondary mechanism of anastrozole as a ligand for ERα (14,15). We also identified biomarkers for selecting patients who might benefit from individual AI therapy, which might have significant clinical implications for individualized therapy of AIs. Although many underlying molecular events that confer AI resistance are known, given our finding of the new mechanism of anastrozole action, how this finding might contribute to anastrozole-specific resistance is yet to be revealed. Here, our results supported a key role of FASN in anastrozole resistance, leading to the identification of potential novel therapeutic targets to help overcome the resistance.

Even though, over time, many ER+ breast tumors lose estrogen dependence for their growth, nearly 30% retain ER expression (44). This implies that activated ER can still serve as a therapeutic target. Recently, FASN, a multienzyme protein that catalyzes the synthesis of fatty acids, has gained attention in breast cancer with respect to its roles in the pathogenesis of breast cancer (32,45). FASN regulates HER2 oncogene, and it acts as the key molecular sensor of energy imbalance under tumor-associated FASN hyperactivity (20). One of the novelties of our previous finding was that anastrozole acts as a ligand for ERα, a mechanism that can contribute to anastrozole-specific resistance. In line with our hypothesis, in the current study we found a large number of anastrozole-regulated genes including FASN (Fig. 1B). FASN inhibition dramatically reduced anastrozole-resistant breast cancer cell growth (Fig. 2), suggesting that FASN is one of the mediators of anastrozole resistance. In this study, we identified the mechanism by which anastrozole regulates FASN expression. Interestingly, anastrozole regulated FASN mRNA and protein levels in the opposite direction in ER+ breast cancer cells (Fig. 3A–B). This type of discrepancy offers, as have been suggested (28), an opportunity to decipher mechanisms embedded in gene regulation. We found that anastrozole-bound ERα elicited transcriptional repression of FASN in ER+ breast cancer cells (Fig. 4A–C), and this process involved the recruitment of NONO and P53 corepressors (Fig. 4F–H).

During the process of examining FASN regulation, we found that anastrozole regulated FASN protein level through its protein degradation (Fig. 5). We determined that anastrozole increased FASN stability via GET4 (Fig. 5A–C). The anastrozole–induced FASN protein upregulation provided increased targets for FASN inhibitors which could explain the increased growth inhibition when combining anastrozole with FASN inhibitors compared to FASN inhibitors alone (Fig. 2D–E).

We have demonstrated that the decreased expression of FASN mRNA stems from the anastrozole-induced activation of the ERα feed-back loop. The phosphorylation of ERα by MAPK is required for the full activity of ERα (41), and FASN protein can activate MAPK signaling (40). Studies have demonstrated the involvement of ERK pathways in regulating FASN expression in cancer cells (40). In agreement, we identified that pERK was an upstream regulator of FASN mRNA expression, and anastrozole increased FASN protein level by upregulation of genes regulating FASN protein stability, resulted in the activation of ERα via MAPK signaling, which in turn repressed FASN transcription (Fig. 6 A–C, H).

Taken together, we summarize a model that anastrozole modulates FASN gene transcription and FASN protein degradation. In this model, anastrozole can repress GET4 transcription via ERα, resulting in up-regulation of FASN protein. As a feedback loop, FASN protein further activates ERα via MAPK signaling, leading to the down-regulation of FASN mRNA by ERα/NONO/P53. Functionally, the anastrozole/ERα/FASN signaling enhances tumor growth. Our finding provides new insights into the anastrozole resistance mechanisms in ER+ breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF), NIH R01CA196648, UG1CA18967, P50CA116201 (Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence), U1961388 (the Pharmacogenomics Research Network), the George M. Eisenberg Foundation for Charities, and the Nan Sawyer Breast Cancer Fund.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare the following competing interests: L.W. and R.M.W are co-founders of OneOme. No direct conflict of interest with this work. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

References

- 1.Allred DC, Harvey JM, Berardo M, Clark GM. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer by immunohistochemical analysis. Mod Pathol 1998;11(2):155–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69(5):363–85 doi 10.3322/caac.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goss PE, Strasser K. Aromatase inhibitors in the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2001;19(3):881–94 doi 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller WR. Aromatase inhibitors: mechanism of action and role in the treatment of breast cancer. Semin Oncol 2003;30(4 Suppl 14):3–11 doi 10.1016/s0093-7754(03)00302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali S, Coombes RC. Endocrine-responsive breast cancer and strategies for combating resistance. Nat Rev Cancer 2002;2(2):101–12 doi 10.1038/nrc721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke R, Liu MC, Bouker KB, Gu Z, Lee RY, Zhu Y, et al. Antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer and the role of estrogen receptor signaling. Oncogene 2003;22(47):7316–39 doi 10.1038/sj.onc.1206937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brueggemeier RW. Aromatase, aromatase inhibitors, and breast cancer. Am J Ther 2001;8(5):333–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santen RJ, Song RX, Zhang Z, Kumar R, Jeng MH, Masamura A, et al. Long-term estradiol deprivation in breast cancer cells up-regulates growth factor signaling and enhances estrogen sensitivity. Endocr Relat Cancer 2005;12 Suppl 1:S61–73 doi 10.1677/erc.1.01018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali S, Metzger D, Bornert JM, Chambon P. Modulation of transcriptional activation by ligand-dependent phosphorylation of the human oestrogen receptor A/B region. EMBO J 1993;12(3):1153–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson DR, Wu YM, Vats P, Su F, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, et al. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet 2013;45(12):1446–51 doi 10.1038/ng.2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan CM, Martin LA, Johnston SR, Ali S, Dowsett M. Molecular changes associated with the acquisition of oestrogen hypersensitivity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells on long-term oestrogen deprivation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2002;81(4–5):333–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin LA, Farmer I, Johnston SR, Ali S, Dowsett M. Elevated ERK1/ERK2/estrogen receptor cross-talk enhances estrogen-mediated signaling during long-term estrogen deprivation. Endocr Relat Cancer 2005;12 Suppl 1:S75–84 doi 10.1677/erc.1.01023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith I, Yardley D, Burris H, De Boer R, Amadori D, McIntyre K, et al. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Adjuvant Letrozole Versus Anastrozole in Postmenopausal Patients With Hormone Receptor-Positive, Node-Positive Early Breast Cancer: Final Results of the Randomized Phase III Femara Versus Anastrozole Clinical Evaluation (FACE) Trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(10):1041–8 doi 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingle JN, Cairns J, Suman VJ, Shepherd LE, Fasching PA, Hoskin TL, et al. Anastrozole has an Association between Degree of Estrogen Suppression and Outcomes in Early Breast Cancer and is a Ligand for Estrogen Receptor alpha. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(12):2986–96 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cairns J, Ingle JN, Dudenkov TM, Kalari KR, Carlson EE, Na J, et al. Pharmacogenomics of aromatase inhibitors in postmenopausal breast cancer and additional mechanisms of anastrozole action. JCI Insight 2020;5(16) doi 10.1172/jci.insight.137571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alo PL, Visca P, Marci A, Mangoni A, Botti C, Di Tondo U. Expression of fatty acid synthase (FAS) as a predictor of recurrence in stage I breast carcinoma patients. Cancer 1996;77(3):474–82 doi . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhajda FP, Jenner K, Wood FD, Hennigar RA, Jacobs LB, Dick JD, et al. Fatty acid synthesis: a potential selective target for antineoplastic therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91(14):6379–83 doi 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doria ML, Ribeiro AS, Wang J, Cotrim CZ, Domingues P, Williams C, et al. Fatty acid and phospholipid biosynthetic pathways are regulated throughout mammary epithelial cell differentiation and correlate to breast cancer survival. FASEB J 2014;28(10):4247–64 doi 10.1096/fj.14-249672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du T, Sikora MJ, Levine KM, Tasdemir N, Riggins RB, Wendell SG, et al. Key regulators of lipid metabolism drive endocrine resistance in invasive lobular breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2018;20(1):106 doi 10.1186/s13058-018-1041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menendez JA, Vellon L, Mehmi I, Oza BP, Ropero S, Colomer R, et al. Inhibition of fatty acid synthase (FAS) suppresses HER2/neu (erbB-2) oncogene overexpression in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101(29):10715–20 doi 10.1073/pnas.0403390101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao Y, Wang J, Jaehnig EJ, Shi Z, Zhang B. WebGestalt 2019: gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47(W1):W199–W205 doi 10.1093/nar/gkz401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jourquin J, Duncan D, Shi Z, Zhang B. GLAD4U: deriving and prioritizing gene lists from PubMed literature. BMC Genomics 2012;13 Suppl 8:S20 doi 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S8-S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cairns J, Ingle JN, Kalari KR, Shepherd LE, Kubo M, Goetz MP, et al. The lncRNA MIR2052HG regulates ERalpha levels and aromatase inhibitor resistance through LMTK3 by recruiting EGR1. Breast Cancer Res 2019;21(1):47 doi 10.1186/s13058-019-1130-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammed H, Taylor C, Brown GD, Papachristou EK, Carroll JS, D’Santos CS. Rapid immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry of endogenous proteins (RIME) for analysis of chromatin complexes. Nat Protoc 2016;11(2):316–26 doi 10.1038/nprot.2016.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansen MP, Knijnenburg T, Reijm EA, Simon I, Kerkhoven R, Droog M, et al. Hallmarks of aromatase inhibitor drug resistance revealed by epigenetic profiling in breast cancer. Cancer Res 2013;73(22):6632–41 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhajda FP, Pizer ES, Li JN, Mani NS, Frehywot GL, Townsend CA. Synthesis and antitumor activity of an inhibitor of fatty acid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000;97(7):3450–4 doi 10.1073/pnas.050582897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackowski S, Wang J, Baburina I. Activity of the phosphatidylcholine biosynthetic pathway modulates the distribution of fatty acids into glycerolipids in proliferating cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000;1483(3):301–15 doi 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenbaum D, Colangelo C, Williams K, Gerstein M. Comparing protein abundance and mRNA expression levels on a genomic scale. Genome Biol 2003;4(9):117 doi 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D Discrepancy between mRNA and protein abundance: insight from information retrieval process in computers. Comput Biol Chem 2008;32(6):462–8 doi 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fournier ML, Paulson A, Pavelka N, Mosley AL, Gaudenz K, Bradford WD, et al. Delayed correlation of mRNA and protein expression in rapamycin-treated cells and a role for Ggc1 in cellular sensitivity to rapamycin. Mol Cell Proteomics 2010;9(2):271–84 doi 10.1074/mcp.M900415-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tian Q, Stepaniants SB, Mao M, Weng L, Feetham MC, Doyle MJ, et al. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of gene expression in Mammalian cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 2004;3(10):960–9 doi 10.1074/mcp.M400055-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 2007;7(10):763–77 doi 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston SR, Lu B, Scott GK, Kushner PJ, Smith IE, Dowsett M, et al. Increased activator protein-1 DNA binding and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activity in human breast tumors with acquired tamoxifen resistance. Clin Cancer Res 1999;5(2):251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiff R, Reddy P, Ahotupa M, Coronado-Heinsohn E, Grim M, Hilsenbeck SG, et al. Oxidative stress and AP-1 activity in tamoxifen-resistant breast tumors in vivo. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92(23):1926–34 doi 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Augello MA, Liu D, Deonarine LD, Robinson BD, Huang D, Stelloo S, et al. CHD1 Loss Alters AR Binding at Lineage-Specific Enhancers and Modulates Distinct Transcriptional Programs to Drive Prostate Tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2019;35(5):817–9 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodrigo-Brenni MC, Gutierrez E, Hegde RS. Cytosolic quality control of mislocalized proteins requires RNF126 recruitment to Bag6. Mol Cell 2014;55(2):227–37 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shao S, Rodrigo-Brenni MC, Kivlen MH, Hegde RS. Mechanistic basis for a molecular triage reaction. Science 2017;355(6322):298–302 doi 10.1126/science.aah6130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stefanovic S, Hegde RS. Identification of a targeting factor for posttranslational membrane protein insertion into the ER. Cell 2007;128(6):1147–59 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hessa T, Sharma A, Mariappan M, Eshleman HD, Gutierrez E, Hegde RS. Protein targeting and degradation are coupled for elimination of mislocalized proteins. Nature 2011;475(7356):394–7 doi 10.1038/nature10181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu N, Li Y, Zhao Y, Wang Q, You JC, Zhang XD, et al. A novel positive feedback loop involving FASN/p-ERK1/2/5-LOX/LTB4/FASN sustains high growth of breast cancer cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2011;32(7):921–9 doi 10.1038/aps.2011.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kato S, Endoh H, Masuhiro Y, Kitamoto T, Uchiyama S, Sasaki H, et al. Activation of the estrogen receptor through phosphorylation by mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science 1995;270(5241):1491–4 doi 10.1126/science.270.5241.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giamas G, Filipovic A, Jacob J, Messier W, Zhang H, Yang D, et al. Kinome screening for regulators of the estrogen receptor identifies LMTK3 as a new therapeutic target in breast cancer. Nat Med 2011;17(6):715–9 doi 10.1038/nm.2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan VC, Brodie AM. Development and evolution of therapies targeted to the estrogen receptor for the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. Steroids 2007;72(1):7–25 doi 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutierrez MC, Detre S, Johnston S, Mohsin SK, Shou J, Allred DC, et al. Molecular changes in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer: relationship between estrogen receptor, HER-2, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(11):2469–76 doi 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bueno MJ, Jimenez-Renard V, Samino S, Capellades J, Junza A, Lopez-Rodriguez ML, et al. Essentiality of fatty acid synthase in the 2D to anchorage-independent growth transition in transforming cells. Nat Commun 2019;10(1):5011 doi 10.1038/s41467-019-13028-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated in this study are available within the article and its supplementary data files.