Abstract

Delirium is a debilitating medical condition that disproportionately affects hospitalized older adults1 and is associated with adverse health outcomes, increased mortality, and high medical costs.2 Efforts to understand delirium risk in hospitalized older adults have focused on examining medical comorbidities, pre-existing cognitive deficits, and other clinical and demographic factors present in the period proximate to the hospitalization.3,4 The contribution of social determinants of health (SDOH), including social circumstances, environmental characteristics, and early-life exposures, referred as the social exposome,5 to delirium risk are poorly understood. Increased knowledge about the influence of SDOH will offer a more comprehensive understanding of factors that may increase vulnerability to delirium and poor outcomes. Clinically, these efforts can guide the development and implementation of holistic preventive strategies to improve clinical outcomes. We propose a social determinants of health (SDOH) framework for delirium tailored to older adults. We provide the definition, description, and rationale for the domains and variables in our proposed model.

Keywords: contextual-level factors, acute changes in cognition, medical settings, health

INTRODUCTION

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the constellation of economic, psychosocial, and environmental factors present throughout a person’s life that may influence health and contribute to global health disparities.6 SDOH may operate through differences in access to healthcare, socioeconomic status, and biological predisposition, to increase health vulnerabilities.7 SDOH can impact health at both the individual level and the contextual-level (environmental/systemic factors). Given SDOH’s synergistic effect on health outcomes, a multi-domain approach to examine potential factors is recommended.8

By 2060, it is expected that 23% of the US population will be >65 years old,9 a demographic shift with large-scale social and economic implications. Late adulthood10 is associated with increased cognitive vulnerabilities and medical needs.11 Older persons who reside in economically disadvantaged areas exhibit worse medical outcomes12 and earlier functional decline13 relative to those in more affluent areas. Ethno-racially diverse older adults are disproportionately affected by dementia relative to their non-Hispanic White peers,14 controlling for age and comorbidity. Thus, advancing our understanding of the factors that improve health outcomes in older adults is a public health priority.

While many prior studies have examined SDOH in the context of chronic conditions, such as dementia, our goal was to explore the impact of SDOH for an acute condition, delirium, which is common and often preventable in older adults. This approach is exploratory and novel, yet strongly supported by several lines of evidence. First, we have previously demonstrated that the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), a social determinant of health indicating neighborhood poverty and disadvantage, was an important risk factor for incident delirium and delirium severity.15 Second, accumulating evidence from electrophysiologic (EEG),16 neuroimaging,17, 18 and biomarker studies of delirium19 has indicated that underlying brain vulnerability, even in the absence of cognitive impairment or dementia, is an important risk factor for delirium. Third, cognitive reserve and resilience play important roles in delirium risk. Our prior work indicates that the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR), reflecting premorbid education and intelligence, is an important risk factor for delirium, even in the absence of cognitive impairment.20 Taken together, this evidence supports our hypothesis that environmental and social factors may increase risk for delirium by increasing brain vulnerability across the lifecourse—that is, over many years or decades of exposure.

Delirium, a clinical syndrome involving an acute change in mental status often precipitated by infection, surgery, or hospitalization, is a common and life-threatening medical condition for many older adults.21,22 Delirium is associated with high medical costs, with attributable healthcare costs of $164 billion per year across all older adults23 and $33 billion per year for older surgical patients.2 In the US, over 2 million older adults are diagnosed with delirium each year.23 While many risk factors for delirium have been described, such as cognitive impairment, frailty, and medical comorbidities,24 the influence of SDOH have not been well-examined. The absence of a conceptual framework to examine the contribution of SDOH to delirium is an important gap. Here we provide an overview of existing theoretical models examining the role of SDOH in chronic medical conditions. Subsequently, we propose an evidence-based SDOH framework for delirium tailored to older adults. Finally, we provide the definition, description, and rationale for the domains and variables in our proposed model.

MODELS OF SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

We conducted a review of publications in PubMed and Google Scholar from 1991–2020, with search terms: [social determinants, determinants, socioeconomic factors, demographic factors] AND [conceptual framework OR model]. We identified 26 frameworks of SDOH;25–28 17 underwent full-text review because they: 1) contained multiple domains, 2) proposed a hierarchical structure between domains, and 3) examined health outcomes. Subsequently, 7 frameworks were excluded since they were tailored to children/adolescents, did not consider lifecourse factors, or were not focused on health disparities. Ten frameworks underwent more comprehensive review. Some frameworks focused on the historical and sociocultural mechanisms that underlie the role of SDOH in health inequities,29,30 such as structural racism. Others discussed the interactions between different SDOH6,31 and their contribution to social and clinical outcomes. Additional frameworks focused on elucidating the role of SDOH within clinical settings, focused on specific diagnoses.27,31 Finally, three SDOH frameworks exemplified our domains of interest and were selected as the basis to develop a SDOH framework for delirium in older adults, described below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Models that Identify Factors that Influence Health Outcomes

| Domains Proposed | National Institute on Aging Health Disparity Framework (Hill et al., 2015) | Sociocultural Framework for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Service Disparity (Alegria et al., 2009) | The Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) SDOH Framework (Solar, 2010) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activities and Social Engagement | Behavioral | Provider/Clinician Factors Patient Factors |

Behaviors and Biological Factors |

| Well-being | Biological | ||

| Demographic Factors | Fundamental Factors | Social Class, Gender, Ethnicity (racism) Education, Occupation, and Income | |

| Social and Economic Factors | Sociocultural | Environmental Context | Material Circumstances |

| Social Capital | Operation of Health Care System and Community System | Social Cohesion and Social Capital Psychosocial Factors | |

| Built and Social Environment | Environmental | Environmental Context | Governance Macroeconomic and Social Policies Culture and Societal Values |

| Lifecourse Factors | Lifecourse Perspective |

National Institute on Aging (NIA) Health Disparities Research Framework

The National Institute on Aging Health Disparities Research (NIA-HDR) framework26 was designed to identify gaps, assess scientific progress, and evaluate health disparities research in aging. This framework utilizes four domains: (1) environmental (geographical and political factors, health care), (2) sociocultural, (3) behavioral (coping factors, health behaviors), and (4) biological (physiological indicators, morbidity). The NIA-HDR framework also highlights fundamental or historical causes of health disparities, such as age, gender, race, and disability status, which are considered across all domains. Lifecourse factors are critical across all domains, illustrating the role of lifetime exposures on health in older adulthood.

Sociocultural Framework for Health Service Disparities

The Sociocultural Framework for Health Service Disparities (SCF-HSD)31 focuses on the structures and mechanisms that interfere with implementation of culturally-sensitive interventions to eliminate disparities in mental health services. The SCF-HSD framework identifies two systems involved in health disparities: (1) health care system (i.e., policies, institution, and persons providing health care services), and (2) community system (i.e., environment and social context). These systems interact and operate via three domains--societal, organizational, and individual--to contribute to disparities in mental health services.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health

The Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) Framework6 conceptualized factors leading to health inequities globally. This framework highlights the connection between health inequities with broader social inequities. Determinants are classified into structural, social systems and institutions leading to the unequal distribution of power, or intermediary factors proximal to the individual in daily life. Social capital, or the social organizations and networks that promote reciprocity and trust, is an important feature of this framework.

A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH TAILORED TO DELIRIUM IN OLDER ADULTS

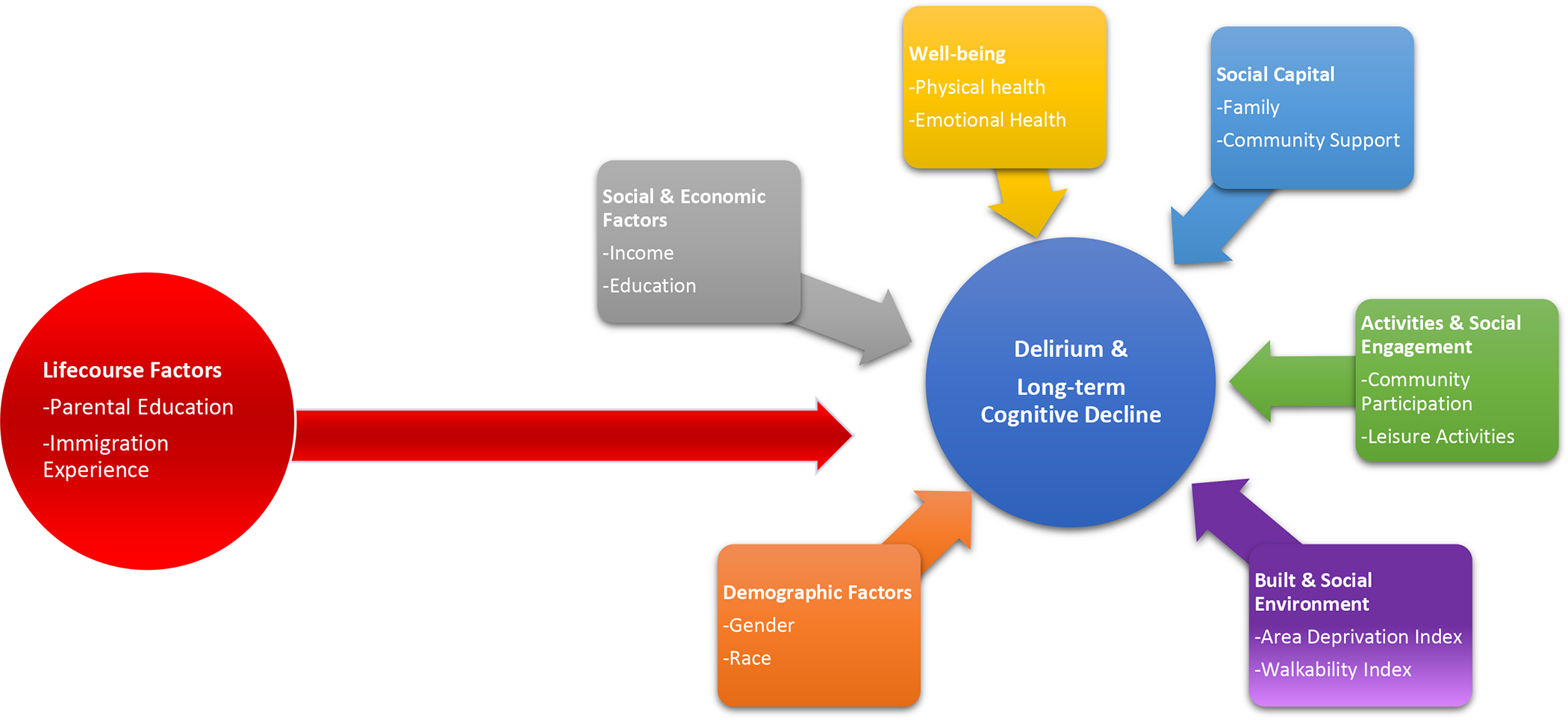

While building on the prior models, our proposed framework has been fully adapted and operationalized for delirium, with rigorous attention to the relevant evidence for delirium in each proposed domain. Specifically, we adapted the domains derived from the 3 frameworks above to make them relevant to delirium in older adults (Table 2). We reviewed prior evidence on health outcomes in older adults relevant to our proposed SDOH domains. For inclusion of specific variables, we required prior published evidence in the context of either chronic or acute cognitive conditions, such as dementia and/or delirium. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed conceptual framework for SDOH related to delirium risk in older adults. Below, we describe the domains, variables, and rationale for each domain.

Table 2.

Social Determinants of Health Variables proposed for delirium risk in older adults

| Proposed Domains | Potential Variables of Interest | Supporting Evidence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Demographic factors | Race Ethnicity Sex/gender |

21, 32–35 | |

| 2. Social and Economic Factors | Education Occupation and job responsibilities Current household income Presence and type of medical insurance |

36–42 | |

| 3. Well-being: Emotional and Physical |

Emotional well-being Depressive symptomatology Mental health/quality of life |

Physical well-being Physical health and multimorbidity Body mass index Hearing impairment Visual impairment Use of alcohol and tobacco |

43–50 |

| 4. Activities and Social Engagement | Participation in social activities, such as dancing, bowling, and religious services Participation in volunteer work |

51–54 | |

| 5. Social Capital | Marital status Living situation/Community support Number and relationship of caregivers |

55–58 | |

| 6. Built and Social Environment | Area Deprivation Index Walkability index |

14–15, 59–62 | |

| 7. Lifecourse Factors | English as second language and primary language Non-US country of origin |

Prior to the age of 16 years old: Family’s financial status Number of siblings Parental level of education Parental occupation and job responsibilities |

63–65 |

Figure 1. A Theoretical Framework of Social Determinants of Health for Delirium in Older Adults.

The figure illustrates a theoretical framework of social determinants of health for delirium in older adults. This model depicts 7 domains (black boxes and black arrow) that are relevant to the health of older adults: demographic factors, social and economic factors, well-being, social capital, activities and social engagement, and built and social environment. Example variables that represent each domain are indicated (grey boxes). Lifecourse factors are depicted as a horizontal arrow to illustrate that exposure to deleterious/protective events affect health outcomes throughout the course of a person’s life.

Demographic Factors.

These factors refer to individual-level characteristics such as age, gender, and ethno-racial diversity. Demographic characteristics influence quality of life directly or through structural inequities that result in persistent exposure to stressors.32 Studies show that willingness to participate in health-promoting interventions differ by a person’s demographic characteristics.33 Moreover, structural inequities lead person’s from diverse groups to disproportionately depend on publicly available programs to access health services,34 and to be more likely to experience misdiagnosis and undertreatment relative to their counterparts.35 Relevant to delirium, increasing age is consistently associated with increased delirium risk.21

Social and Economic Factors.

These factors capture information related to affluence and power, and include income, education, and paid employment. Older adults who report low SES are more likely than their counterparts to experience earlier onset of chronic disease and functional disabilities.36,37 Financial security and employment conditions have been associated with cognitive health.38 Low education level is a risk factor for premature cognitive decline.39 Diminished functional status and cognitive impairment are more prevalent in economically marginalized older adults.40 Given that dementia, increased medical comorbidity, and reduced functional status are documented risk factors for delirium, social and economic factors at the individual and neighborhood level may increase delirium risk via both direct and indirect mechanisms.41,42

Well-being: Emotional and Physical.

Designed to encompass aspects of the patient’s health that influence their ability to interact with and benefit from health-promoting resources available within the community and health care system.43 Physical well-being refers to factors such as hearing,44 vision, pain,45, and medical conditions. Emotional well-being refers to depression, anxiety, and social isolation.46,47 Physical and emotional well-being are associated with cognition and health-related quality of life.48 Depression, chronic pain, and diminished hearing and vision have been associated with delirium risk.49,50 Additional references are included in the supplemental materials (Supplemental Appendix S1).

Activities and Social Engagement.

This domain captures the participation of older adults in social and community systems, such as volunteering and participation in group activities.51 Studies have shown that participation in occupational and leisure activities promotes functional independence, greater life satisfaction, and longevity.52 Non-pharmacological delirium prevention strategies incorporating therapeutic activities and social engagement53 are useful to reduce incident delirium in older adults.54

Social Capital.

This domain includes access to healthcare support.55 Data suggests that diminished social interactions are associated with incident dementia.56 Relevant to delirium, many prior studies have documented the importance of family members and informal caregivers in reducing incident delirium.57,58

Built and Social Environment.

This domain captures the characteristics and safety of the individual’s environment,59 such as the home environment, neighborhood poverty level, and access to community recreational facilities. Characteristics of the living environment have been associated with higher rates of 30-day rehospitalization,14 Alzheimer’s disease,60 and general health in older adults.61 Residing in a neighborhood that supports walking to and from destinations is associated with better health among older adults.62 We have demonstrated that patients residing in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods experience increased delirium and delirium severity relative to patients residing in the least disadvantaged neighborhoods.15

Lifecourse Factors.

This domain includes social and cultural factors present throughout a persons’ life, including early life exposures such as childhood health and socioeconomic status. Lifetime exposures interact with the environment, social structures, and biological predisposition to influence health.63 For example, maternal and paternal education have been associated with educational attainment and dementia risk.64,65 Preliminary (unpublished) work by our group suggests that paternal education may influence delirium incidence and severity.

DISCUSSION

We have proposed a novel conceptual framework of SDOH for delirium in older adults. Our framework allows us to expand existing constructs of social disadvantage to consider domains beyond traditional ethno-racial and socioeconomic indicators. It is grounded by a careful review of prior conceptual models, and the domains and variables proposed are strictly evidence-based. The proposed framework is innovative in several ways. First, it is tailored specifically to the unique considerations of older adults, including risk factors and health outcomes. Second, our focus on an acute medical condition – delirium – is highly novel and provides an approach to better conceptualize vulnerability to acute stressors. Finally, our framework is unique in incorporating a lifecourse approach to examine how exposures across the lifespan affect delirium in late life. Our conceptual framework can help to broaden our holistic understanding of vulnerability to delirium.

Several caveats deserve comment. First, while grounded in prior evidence, our proposed framework has not yet been empirically tested for prediction of delirium or other health outcomes. Second, the proposed variables were limited to those with available evidence from prior studies. Third, the complex inter-relationships, including potential interactions and synergies between the domains and variables, have not yet been examined. While SDOH have been documented to affect cognitive impairment and dementia, addressing their contribution to delirium is exploratory yet important, given its preventable nature and the potential to offset the development of subsequent adverse outcomes and dementia. Moreover, such examination is feasible, given that there are many studies enrolling older adults without cognitive impairment or dementia to examine risk factors and outcomes of delirium.66 The interactions of SDOH with delirium and with related conditions such as cognitive impairment and frailty will be required in future work. Finally, the mechanisms by which these SDOH may lead to poor health outcomes are not addressed by this framework. Cognitive reserve, or the behavioral and neurobiological substrate that confers resilience to disease, has been proposed as a mechanism that explains a patient’s vulnerability to delirium.4 Examining how cognitive reserve accumulates over time, and is impacted by SDOH will be an important area for future research.67

Conclusions

Our SDOH framework for delirium is a novel exploration to capture the challenges and vulnerabilities unique to older adults. This conceptualization may motivate the development of innovative and impactful individual and community-based intervention strategies focused on prevention and mitigation of delirium by targeting SDOH, such as community-based interventions (improving access and health literacy)68 and supporting family caregivers.69 Ultimately, such interventions may improve health outcomes and quality of life for vulnerable older populations.

Supplementary Material

Key Points:

Delirium is a common psychiatric syndrome that is costly and potentially life-threatening when present in older adults.

The contribution of social determinants of health (SDOH) to delirium risk are poorly understood.

Knowledge about the influence of SDOH in the medical settings will offer a more comprehensive understanding of factors that may increase vulnerability to delirium.

Why does this matter?

We propose a social determinants of health (SDOH) framework for delirium that is tailored to the needs of older adults. Our novel framework aims to comprehensively capture the social circumstances, environmental characteristics, and life course factors that may protect against or precipitate delirium in older adults.

Funding:

This work was funded in part by grants no. P01AG031720 (SKI) and R24AG054259 (SKI) from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Marcantonio’s time in part by K24AG035075; Dr. Franchesca Arias’ time was supported in part by an NIA Diversity Supplement to grant P01AG031720 (SKI) and by grant no. 2019-AARFD-644816 of the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Inouye holds the Milton and Shirley F. Levy Family Chair at Hebrew SeniorLife/Harvard Medical School. Dr. Kind’s time in part by R01AG070883, RF1AG057784 and P30AG062715. Dr. Alegria’s time is funded in part by 1R01AG046149.

Sponsor’s Role:

The funding sources was not involved in the design, analysis, or reporting of the results.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no competing interests or conflicts to declare.

Dedication: This work is dedicated to the memory of Joshua Bryan Inouye Helfand. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the patients, family members, nurses, physicians, research team, and Executive Committee members who participated in the Successful Aging after Elective Surgery (SAGES) study.

| Franchesca Arias, Ph.D. franchescaarias@hsl.harvard.edu |

This author was involved in all aspects of project concept, design, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation of manuscript |

| Margarita Alegria, Ph.D. Malegria@mgh.harvard.edu |

This author was involved in project concept, data interpretation, and preparation of manuscript |

| Amy. J. Kind, M.D., Ph.D. ajk@medicine.wisc.edu |

This author was involved in project concept, data analysis, and preparation of manuscript |

| Richard Jones, Sc.D. richard_jones@brown.edu |

This author was involved in project concept, data interpretation, and preparation of manuscript |

| Thomas Travison, Ph.D. TGT@hsl.harvard.edu |

This author was involved in project concept and preparation of manuscript |

| Edward R. Marcantonio, M.D., S.M. emarcant@bidmc.harvard.edu |

This author was involved in project concept, data interpretation, and preparation of manuscript |

| Eva Schmitt, Ph.D. EvaSchmitt@hsl.harvard.edu |

This author was involved in data collection, data interpretation, and preparation of manuscript |

| Tamara Fong, M.D., Ph.D. tamarafong@hsl.harvard.edu |

This author was involved in project concept, design, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation of manuscript |

| Sharon K. Inouye, M.D., M.PH. SharonInouye@hsl.harvard.edu | This author was involved in all aspects of the project: concept, design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and preparation of manuscript |

Supplemental Material Descriptive Title: Additional References

REFERENCES

- 1.Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1161–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gou RY, Hshieh TT, Marcantonio ER, Cooper Z, Jones RN, Travison TG, Fong TG, Abdeen A, Lange J, Earp B, Schmitt EM. One-Year Medicare Costs Associated With Delirium in Older Patients Undergoing Major Elective Surgery. JAMA Surgery. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, & Inouye SK (2009). Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nature Reviews Neurology, 5(4), 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones RN, Yang FM, Zhang Y, Kiely DK, Marcantonio ER, & Inouye SK Does educational attainment contribute to risk for delirium? A potential role for cognitive reserve. J Gerontol Series A. 2006;61(12):1307–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wild CP Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark Prev. 2005;14(8):1847–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. WHO Document Production Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irwin A, Scali E. Action on the social determinants of health: a historical perspective. Glob Public Health. 2007;2(3):235–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vespa J The US joins other countries with large aging populations. US Census Bureau website. Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/03/graying-america.html. Accessed. 2019;27:19.

- 10.Widick C, Parker CA, Knefelkamp L. Erik Erikson and psychosocial development. New Directions for Student Services.1978;4:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Humboldt S, Leal I, Pimenta F. What predicts older adults’ adjustment to aging in later life? The impact of sense of coherence, subjective well-being, and sociodemographic, lifestyle, and health-related factors. Educ Gerontol. 2014;40(9):641–54. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, Yu M, Bartels C, Ehlenbach W, Greenberg C, Smith M. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;161(11):765–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoeni RF, Martin LG, Andreski PM, Freedman VA. Persistent and growing socioeconomic disparities in disability among the elderly: 1982–2002. AJPH. 2005;95(11):2065–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quiñones AR, Kaye J, Allore HG, Botoseneanu A, Thielke SM. An Agenda for Addressing multimorbidity and racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s Disease and related dementia. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Dement. 2020;35:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arias F, Chen F, Fong TG, Shiff H, Alegria M, Marcantonio ER, Gou Y, Jones RN, Travison TG, Schmitt EM, Kind AJ. Neighborhood-Level Social Disadvantage and Risk of Delirium Following Major Surgery. JAGS. 2020;68(12):2863–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavallari M, Dai W, Guttmann CR, Meier DS, Ngo LH, Hshieh TT, Callahan AE, Fong T, Schmitt E, Dickerson BC, Press DZ, Marcantonio E, Jones RN, Inouye SK*, Alsop DC* Neural substrates of vulnerability to postsurgical delirium as revealed by presurgical diffusion MRI. Brain. 2016; 139:1282–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavallari M, Dai W, Guttman CR, Meier DS, Ngo LH, Hshieh TH, Fong TG, Schmitt E, Press DZ, Travison TG, Marcantonio ER, Jones RN, Inouye SK*, Alsop DC*; on behalf of the SAGES Study Group. Longitudinal diffusion changes following postoperative delirium in older people without dementia. Neurology. 2017; 89:1020–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fong TG*, Vasunilashorn SM*, Ngo L, Libermann TA, Dillon ST, Schmitt EM, Pascual-Leone A, Arnold SE, Jones RN, Marcantonio ER*, Inouye SK* for the SAGES Study Group. Association of Plasma Neurofilament Light with Postoperative Delirium. Ann Neurol. 2020. 88:984–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cizginer S, Marcantonio ER, Vasunilashorn S, Pascual-Leone A, Shafi MM, Schmitt EM, Inouye SK*, Jones RN*. The cognitive reserve model in the development of delirium: the Successful Aging after Elective Surgery Study (SAGES). J Geriatr Pyschiatry Neurol. 2017; 30:337–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Dellen E, van der Kooi AW, Numan T, Koek HL, Klijn FA, Buijsrogge MP, Stam CJ, Slooter AJ. Decreased functional connectivity and disturbed directionality of information flow in the electroencephalography of intensive care unit patients with delirium after cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2014. August;121(2):328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tieges Z, Quinn T, MacKenzie L, Davis D, Muniz-Terrera G, MacLullich AM, Shenkin SD. Association between components of the delirium syndrome and outcomes in hospitalised adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC geriatrics. 2021. December;21(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, Van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2010. July 28;304(4):443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shokouh SM, Mohammad AR, Emamgholipour S, Rashidian A, Montazeri A, Zaboli R. Conceptual models of social determinants of health: A narrative review. IJPHCD. 2017;46(4):435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill CV, Pérez-Stable EJ, Anderson NA, Bernard MA. The National Institute on Aging health disparities research framework. Ethn Dis. 2015;25(3):245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gehlert S, Sohmer D, Sacks T, Mininger C, McClintock M, Olopade O. Targeting health disparities: a model linking upstream determinants to downstream interventions. Health Aff. 2008;27(2):339–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diderichsen F, Evans T, Whitehead M. The social basis of disparities in health. Challenging inequities in health: From Ethics to Action. 2001;1:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adler NE, Ostrove JM. Socioeconomic status and health: What we know and what we don’t. Ann N.Y. Acad Sci. 1999;896(1):3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howden-Chapman PC, O’Dea P, Salmond D, Wilson C, Nick Blakely T. Social inequalities in health: New Zealand: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alegría M, Sribney W, Perez D, Laderman M, Keefe K. The role of patient activation on patient–provider communication and quality of care for US and foreign born Latino patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):534–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia MA, Downer B, Chiu CT, Saenz JL, Ortiz K, & Wong R Educational benefits and cognitive health life expectancies: Racial/ethnic, nativity, and gender disparities. Gerontol. 2021;61(3): 330–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarit SH, & Pearlin LI Special issue on health inequalities across the life course. J Gerontol Series B. 2005;60(Special_Issue_2): S6–S6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gornick M Vulnerable populations and Medicare services: Why do disparities exist? New York. Century Foundation Press. (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayberry RM, Mili F, & Ofili E Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Medical Care Research Review. 2000; Suppl 1:108–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crimmins EM, Kim JK, & Seeman TE Poverty and biological risk: the earlier “aging” of the poor. J Gerontol Series A. 2009; 64(2): 286–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louwman WJ, Aarts MJ, Houterman S, Van Lenthe FJ, Coebergh JWW, & Janssen-Heijnen MLGA 50% higher prevalence of life-shortening chronic conditions among cancer patients with low socioeconomic status. Bri J Cancer. 2010;103(11):1742–1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zahodne LB, Manly JJ, Smith J, Seeman T, & Lachman ME Socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial mediators of racial disparities in cognition in early, middle, and late adulthood. Psychology and aging. 2017; 32(2): 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsemann KM, & Ailshire JA Early educational experiences and trajectories of cognitive functioning among US adults in midlife and later. AJPH. 2020;189(5):403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schoeni RF, Martin LG, Andreski PM, & Freedman VA Persistent and growing socioeconomic disparities in disability among the elderly: 1982–2002. AJPH. 2005; 95(11): 2065–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fong TG, Jones RN, Shi P, Marcantonio ER, Yap L, Rudolph JL, … & Inouye SK Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72(18):1570–1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, Fong TG, Tommet D, Quach L, … & Inouye SK Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med. 2012; 172(17):1324–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen C, Goldman DP, Zissimopoulos J, & Rowe JW Multidimensional comparison of countries’ adaptation to societal aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018;115(37):9169–9174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brewster KK, Pavlicova M, Stein A, Chen M, Chen C, Brown PJ, … & Rutherford BR A pilot randomized controlled trial of hearing aids to improve mood and cognition in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2020;35(8):842–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kosar CM, Tabloski PA, Travison TG, Jones RN, Schmitt EM, Puelle MR, … & Inouye SK Effect of preoperative pain and depressive symptoms on the risk of postoperative delirium: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(6):431–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prince MJ, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet. 2015;385:549–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. 2020. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Floud S, Balkwill A, Sweetland S, Brown A, Reus EM, Hofman A, … & Beral V Cognitive and social activities and long-term dementia risk: the prospective UK Million Women Study. The Lancet Public Health. 2021; 6(2): e116–e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomlinson EJ, Phillips NM, Mohebbi M, & Hutchinson AM Risk factors for incident delirium in an acute general medical setting: A retrospective case–control study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2015;26(5–6): 658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Givens JL, Jones RN, & Inouye SK (2009). The overlap syndrome of depression and delirium in older hospitalized patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(8):1347–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.