SUMMARY

Objective.

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) are characterized by multifocal and global abnormalities in brain function and connectivity. Only a few studies have examined neuroanatomic correlates of PNES. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is reported in 83% of patients with PNES and may be a key component of PNES pathophysiology. In this study, we included patients with TBI preceding the onset of PNES (TBI-PNES) and TBI without PNES (TBI-only) to identify neuromorphometric abnormalities associated with PNES.

Methods.

Adults diagnosed with TBI-PNES (N=62) or TBI-only (N=59) completed psychological questionnaires and underwent 3T MRI. Imaging data were analyzed by voxel- and surface-based morphometry. Voxelwise general linear models computed group differences in GMV, cortical thickness, sulcal depth, fractal dimension (FDf), and gyrification. Statistical models were assessed with permutation-based testing at 5000 iterations with the Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement toolbox. Logarithmically scaled p-values corrected for multiple comparisons using family-wise error were considered significant at p<0.05. Post-hoc analyses determined the association between structural and psychological measures (p<0.05).

Results.

TBI-PNES participants demonstrated atrophy of the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG) and the right cerebellum VIII. Relative to TBI-only, TBI-PNES participants had decreased FDf in the right superior parietal gyrus and decreased sulcal depth in the left insular cortex. Significant clusters were positively correlated with global assessment of functioning scores, and demonstrated varying negative associations with measures of anxiety, depression, somatization, and global severity of symptoms.

Significance.

The diagnosis of PNES was associated with brain atrophy and reduced cortical folding in regions implicated in emotion processing, regulation, and response inhibition. Cortical folds primarily develop during the third trimester of pregnancy and remain relatively constant throughout the remainder of one’s life. Thus, the observed aberrations in FDf and sulcal depth could originate early in development. The convergence of environmental, developmental, and neurobiological factors may coalesce to reflect PNES’ neuropathophysiological substrate.

Keywords: psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, voxel-based morphometry, cortical folding, grey matter volume, neuromorphometry, traumatic brain injury

1. OBJECTIVE

Uncontrolled electrical activity between neurons produces epileptic seizures, but not all seizures are rooted in abnormal neuronal firing. Psychogenic non-epileptic (functional) seizures (PNES), instead arise from the combination of psychiatric symptoms and psychosocial stressors.1,2 Though PNES’ paroxysmal episodes bear a clinical resemblance to epileptic seizures, electroencephalograms (EEGs) remain normal during typical events.3,4 Moreover, standard anti-seizure medications (ASMs) do not treat and can sometimes exacerbate PNES.5 Due to the similar semiology and failure of ASMs, many patients with PNES are initially diagnosed as having treatment-resistant epilepsy (TRE).4,5 Similar to TRE, patients with PNES have higher incidences of anxiety, depression, prior abuse, and/or trauma, as well as poorer quality of life.6-8 To date, many studies have investigated psychiatric comorbidities and psychosocial stressors in participants with PNES.9,10 However, the neurobiological correlates of PNES are less well-understood.11 While they are etiologically conceived as a manifestation of psychological distress, the neuropathophysiology of PNES is an area of active inquiry.11

Evidence from neuroimaging studies suggests PNES is a disorder of multiple large-scale neural networks that is characterized by multifocal abnormalities in brain function and connectivity.1,12,13 These, in turn, are tied to their structural morphology and the underlying cytoarchitecture. To date, few studies have sought to examine the structural correlates of PNES. The lack of macroscopic abnormalities on structural MRI have led many to conclude that the brains of patients with PNES are normal, which is true from a “lesional” perspective.14 However, the absence of macroscopic structural MRI abnormalities in PNES suggests that network aberrations may stem from pathology at the microstructural level, which can be investigated by voxel- and surface-based morphometry.15-17 Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) quantifies grey matter volume (GMV) in a certain structure or region of interest by measuring signals from grey matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. Surface-based morphometry (SBM) uses those signals to recreate the brain’s surface and maps its topographical landscape to measure the thickness of the brain’s cortex, characterize the amount of folding, estimate sulcal depth, and index brain surface complexity. To date, only two relatively small studies have used VBM and SBM to study brain morphology in patients with PNES.18,19 The first investigation of brain structure in PNES (n = 20) found cortical atrophy of the right motor and premotor regions and the bilateral cerebellum, relative to 40 matched healthy controls.18 Atrophy of premotor regions was associated with higher depression scores.18 Another study was conducted in 37 PNES participants and 37 age- and sex- matched healthy controls and found changes in regions involved in emotion processing: cortical thickness increased in the left inferior anterior insula and bilateral orbitofrontal and precentral regions, and thickness was reduced in the left anterior cingulate.19

The inconsistent results of the two prior studies highlight the need for larger studies that better delineate the structural changes specific to PNES. Aberrant neuroplasticity can certainly cause changes in brain volume and corresponding deviations in surface-based metrics, but the direction of plasticity (gains vs losses) is routinely conserved in patient populations. Based on the clinical presentation, previous studies of PNES, and VBM analyses in patients with mood disorders, we would expect neuronal loss and cortical thinning in brain regions implicated in emotion regulation. Notably, both prior studies compared PNES to healthy control groups rather than a clinical comparison group. Healthy participants are frequently used as a control sample. However, they are not customarily assessed for the neuropsychiatric comorbidities, early life adverse life events, and history of head trauma, all of which may occur in many patients with PNES.18,19 These limitations render healthy control group comparisons less relevant to neuropsychiatric research. Moreover, it is unclear if abnormal brain morphology is linked with PNES, whether it is inherited or acquired because of traumatic or other brain injury, or whether it is associated with patients’ psychological comorbidities. Since up to 83% of patients with PNES report a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI), TBI may be a key component of PNES neuropathophysiology.20-22 Patients with mild TBI are also three times more likely to experience depression, with symptoms of emotional dysregulation persisting well beyond resolution of physiological brain injury.23 Thus, TBI provides a potential model to investigate the neural substrates that link PNES with emotional dysregulation.

The present study used VBM and SBM to computationally dissect neuropathophysiological factors associated with PNES by investigating patients with TBI with (TBI-PNES) and without PNES (TBI-only). We hypothesized that participants with TBI-PNES would show brain atrophy and cortical morphology aberrations in regions implicated in emotional processing. We further hypothesized morphological abnormalities to be associated with psychological measures (anxiety, depression, quality of life), with magnitude of volume- or surface-based neuronal loss corresponding to scores on self-report measures of affect and functioning.

2. METHODS

This multi-site study recruited 121 adult participants from three sites: 1) the Providence VA Healthcare System, 2) Rhode Island Hospital, and 3) the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB). Participants were recruited by clinician referrals, approved study flyers, press releases, and social media posts. Study details were shared and posted on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03441867). Pre-screenings conducted over the phone or in-person assessed patients’ interest, study eligibility, and MRI-compatibility. Electronic medical records and other files were consulted for definitive diagnosis of TBI and PNES and for documenting clinical history. Participants provided written informed consent prior to study participation. All study procedures were approved by the VA, RIH and UAB Institutional Review Boards, and were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants were screened for recruitment via a phone screen and medical chart review. All participants (TBI-only and TBI-PNES) were offered participation on the basis of: 1) history of documented TBI, 2) age of 18 to 60 years, 3) ability to undergo 3T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (e.g., no metal implants or claustrophobia), 4) a negative urine pregnancy test if female of childbearing potential, and 5) ability to complete questionnaires. For TBI-PNES participants only, additional inclusionary criteria were: 1) video/EEG-confirmed PNES, and 2) at least one PNES during the year prior to enrollment. Participants were excluded from the study if they did not meet inclusion criteria or were unable to complete self-report assessments during study visits. Additional exclusionary criteria included: 1) self-injurious behavior at enrollment or during the preceding year, 2) current or recent suicidal intent as indicated by score >1 for question 9 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI), at enrollment or during the preceding year, 3) psychosis at enrollment or during the preceding year, 4) current application or pending litigation for long-term disability, or 5) active substance or alcohol use disorder in the last 3 months.24

Participants’ clinical history, medical records and video/EEG findings were reviewed to confirm history of TBI and diagnosis of subsequent PNES, a process overseen by study epileptologists.

Clinical history and medical records were the primary sources for details regarding TBI history. This included the dates of the first, most severe, and most recent TBI, as well as TBI severity classification(s). For patients with documented history of TBI, clinical severity was classified using the DSM-5 TBI criteria components: Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), loss/alteration of consciousness, and post-traumatic amnesia.25 Patient narratives were used when source documents from medical records were unavailable.

PNES were defined as “clinical activity typical for patient’s events not associated with EEG epileptiform correlates before, during, or after the ictus, and not associated with a physiological non-epileptic event.” Physiological non-epileptic events included convulsive syncope, substance withdrawal seizures, etc. Sensory simple partial (focal) seizures were also excluded. A PNES diagnosis was confirmed by a board-certified epileptologist using International League Against Epilepsy criteria.26 PNES diagnosis included confirmatory review of participants’ prior video EEG or EEG recordings.

2.2. Study measures

All participants had diagnoses established by Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis of DSM-5.25 Anxiety and depression, quality of life, and functioning were measured through a battery of self-report assessments. Anxiety was measured with the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), while depression was measured with the BDI.24,27 The Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) instrument was used to assess the global severity and somatization of psychological symptoms with the Global Severity Index (GSI) and somatization subscale (SOM), respectively.28 Clinical staff scored the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale, which measured each participant’s symptoms effect in their day-to-day quality of life and psychological, social, and occupational functioning.29

2.3. Structural brain imaging

Structural imaging data were acquired using identical protocols and equipment at Brown University Magnetic Resonance Imaging Facility and the UAB Civitan International Neuroimaging Laboratory. All participants were scanned on a 3T Siemens Magnetom Prisma MRI using a 64-channel head coil. A 3-D high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition with gradient echo (MPRAGE) brain scan was acquired with the following parameters: TR/TE 2400/2.22 ms, FOV 24.0×25.6×16.7 cm, matrix 256x256 mm2, flip angle 8°, slice thickness = 0.8 mm isotropic voxels. Hardware and software synchronization between centers was performed and quality assessments of data were evaluated as previously described.30 Per visual inspection, none of the participants’ data demonstrated brain lesions that required masking during processing.

2.3.1. Voxel-based morphometry

Participants’ T1-weighted images were processed as previously described using the Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12) in Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk)) running in MATLAB 2020a (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA).15,31 Briefly, this included skull-stripping, bias correction, tissue segmentation with partial volume estimation, denoising, normalization, modulation, and smoothing. Tissue segments were spatially normalized to standard 1.5 mm voxel size Montreal Neurological Institute space by the Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration through the Exponentiated Lie Algebra algorithm.32 Modulated images were spatially smoothed with an 8-mm full-width-at-half-maximum Gaussian smoothing kernel. CAT12 tissue segmentation calculated total intracranial volume (TIV), which captures head size variation stemming from individual factors such as biological sex. The smoothed brain volumes were thus corrected for TIV before statistical computations. TIV was modeled as a predictor of voxelwise GMV in a multiple regression model with resultant residuals yielding volumes representative of the group effect only.

2.3.2. Surface-based morphometry

Volume-based surface measures were estimated using a fully automated approach integrated with CAT12 tissue segmentation during VBM processing.16 Cortical thickness, fractal dimensionality (FDf), gyrification, and sulcal depth were estimated for the right and left hemispheres.16,17 The distances between grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM) regions were estimated using projection of local maxima.16 The central surface was reconstructed on the basis of these neighboring relationships, at the 50% distance between GM/WM and GM/CSF boundaries.16 Data underwent topology correction, spherical inflation, and spherical registration. Surface data for the left and right hemispheres were merged, resampled, and spatially smoothed using the default 15-mm FWHM Gaussian kernel. Significant clusters were labeled using the Desikan-Killiany-Tourville atlas.33

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, normality and outlier testing, and group differences were computed for study measures (demographic, disease-related, and psychological variables). Continuous variables were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 for Mac (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com). A chi-square test of association was conducted within IBM SPSS Version 27.0 for Mac (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) to determine if there was an association between group and biological sex, as well as group and most severe TBI. The frequency and group differences in levels of ordinal variables (e.g., TBI diagnosis) were evaluated with the Kruskal-Wallis H test. All study measures found to be significantly different between groups were additionally modeled as variables of interest within voxelwise general linear models (GLMs).

Within SPM12, voxelwise GLMs were computed to investigate group differences in brain morphology measures. Statistical models were assessed with permutation-based testing at 5000 iterations to create clusters with the Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement (TFCE) toolbox as implemented in SPM12 (http://www.neuro.uni-jena.de/tfce/). TFCE-based results were visualized with logarithmically scaled p-values that combined voxel-height and cluster size. Results were considered significant at p<0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using family-wise error (FWE). The magnitude and direction of significant effect(s) were determined by extracting and analyzing data within clusters using cluster-specific masks. Post-hoc correlation analyses were performed to evaluate the relationship between study measures and mean cluster data found to be significantly different between groups. The Pearson correlation coefficient was computed for datasets without outliers; Spearman’s ρ was used for variables impacted by outliers.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics and Participant Features

Data are presented for 121 adult participants diagnosed with TBI-PNES (N=62) or TBI-only (N=59). Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of each group. The mean age at PNES onset was 31.6±12.3 years and the mean duration of PNES diagnosis for the group was 4.9 ± 7.5 years. PNES semiology included motor and non-motor presentations. There were no differences between TBI-only and TBI-PNES groups in age or age at first TBI. TBI-PNES participants reported higher number of current medications (6.4±6.5 meds, p<0.0001), a regimen that included current ASMs for 56.5% of the group. TBI-PNES participants had significantly lower (worse) GAF scores (p<0.0001), and significantly higher GSI and SOM subscale scores for the SCL-90-R (p<0.001). TBI-PNES participants reported greater depressive symptoms (BDI, p<0.0001) and anxiety (BAI, p<0.0001) than TBI-only participants (Table 1). Significantly more TBI-PNES participants reported history of emotional and verbal abuse during both childhood and adulthood. Psychiatric comorbidities and history of substance abuse/dependence was established with SCID. The majority (69.4%) of the study sample did not report prior or current history of substance abuse/dependence. Twenty-six participants (21.5%) reported dependence on 1 substance, 10 (8.3%) reported abuse/dependence of 2 substances. A single participant (0.8%) reported abuse/dependence of 3 substances. Per the SCID, 31 of the total participants had 2 concurrent psychiatric diagnoses, while 27 participants had 3 concurrent diagnoses; only 5 participants had 4 concurrent diagnoses. Of the entire sample, 32 total participants (26.4%) had both substance abuse/dependence and psychiatric symptoms per SCID results. TBI-PNES and TBI-only participants showed significant differences only the in distribution of PTSD (p<0.017). The frequency of the other psychiatric comorbidities was not different between groups (all p’s> 0.05). Seven participants had a conversion or somatoform disorder other than PNES, 6 of whom were TBI-PNES participants.

Table 1.

Summary of participants’ neuropsychological assessment scores, clinical characteristics, and global brain volume metrics.

| All (N=121) |

TBI-only (N=59) |

TBI-PNES (N=62) |

Group difference or association | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | Age (years) | 37.3 ± 11.9 | 37.6 ± 11.8 | 37.0 ± 12.0 | t(119) = 0.26, p = 0.80 |

| Age at TBI (years) | 17.0± 11.9 | 18.8 ± 12.2 | 15.3 ± 11.5 | t(112) = 1.6, p < 0.111 | |

| Total # TBIs | 4.1 ± 5.5 | 3.7 ± 4.1 | 4.6 ± 6.8 | t(111) = 0.92, p = 0.36 | |

| Years since TBI | 20.2 ± 13.7 | 18.6 ± 14.0 | 21.9 ± 13.3 | t(111) =1.31, p = 0.20 | |

| Age at PNES onset | 31.6 ± 12.3 | ||||

| Duration of PNES | 4.9 ± 7.5 | ||||

| History of abuse as a child (# of pts) | Physical | 34 | 12 | 22 | χ2(1, N=53) =1.51, p = 0.219 |

| Verbal | 34 | 10 | 24 | χ2(1, N=50) =4.96, p = 0.026 | |

| Emotional | 46 | 11 | 35 | χ2(1, N=64) =10.27, p = 0.001 | |

| Sexual | 35 | 9 | 26 | χ2(1, N=51) =2.91, p = 0.088 | |

| History of abuse as an adult (# of pts) | Physical | 29 | 10 | 19 | χ2(1, N=54) =1.02, p = 0.313 |

| Verbal | 26 | 7 | 19 | χ2(1, N=49) =4.43, p = 0.035 | |

| Emotional | 38 | 8 | 30 | χ2(1, N=64) =9.00, p = 0.003 | |

| Sexual | 22 | 5 | 17 | χ2(1, N=51) =2.76, p = 0.252 | |

| Psychiatric Comorbidities (# of pts) | MDD and/or other depressive disorders | 63 | 26 | 37 | χ2(1, N=121) =2.95, p = .086 |

| Anxiety disorders | 57 | 25 | 32 | χ2(1, N=121) =1.04, p = 0.31 | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 48 | 17 | 31 | χ2(1, N=121) =5.67, p = 0.017 | |

| Additional conversion or somatoform disorder | 7 | 1 | 6 | χ2(1, N=121) = 3.53, p = 0.06 | |

| Bipolar disorder | 6 | 3 | 3 | χ2(1, N=121) =0.004, p = 0.95 | |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 6 | 3 | 3 | χ2(1, N=121) =0.004, p = 0.95 | |

| Substance abuse or dependence | 37 | 19 | 18 | χ2(4, N=121) =1.517, p = 0.678 | |

| Personality disorder | 23 | 5 | 18 | χ2(8, N=48) = 9.523, p = 0.30 | |

| Medications | Total # of current meds | 4.7 ± 5.6 | 2.9 ± 3.6 | 6.4 ± 6.5 | t(94.05) = 3.6, p < 0.0001 |

| Current on ASMs (% yes) | 34.7% | 11.8% | 56.5% | χ2(3, N=119) = 27.13, p< 0.001 | |

| Anxiety and Depression Scores | BAI, total score | 18.6 ± 13.8 | 11.8 ± 12.1 | 25.0 ± 12.1 | H(1) = 31.4, p < 0.0001 |

| BDI, total score | 17.3 ± 13.8 | 11.4 ± 12.8 | 22.9 ± 12.4 | H(1) = 23.8, p < 0.0001 | |

| Quality of Life and Functioning | GAF score | 67.9 ± 17.2 | 79.6 ± 15.5 | 55.7 ± 8.0 | H(1) = 57.2, p < 0.0001 |

| SLC-90-R, GSI | 0.85 ± 0.74 | 0.60 ± 0.62 | 1.1 ± 0.77 | t(119) = 3.8, p < 0.001 | |

| SLC-90-R, SOM | 1.1 ± 0.90 | 0.67 ± 0.66 | 1.5 ± 0.92 | t(113) = 5.5, p < 0.001 | |

| Global brain volume | TIV | 1390 ± 148.9 | 1425 ± 139.1 | 1356 ± 151.2 | t(119) = 2.6, p = 0.01 |

| GM, global | 645.4 ± 68.1 | 664.1 ± 66.5 | 627.6 ± 65.2 | t(119) = 3.1, p = 0.003 |

Abbreviations: TBI, traumatic brain injury; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures; H/o, history of; MDD, Major Depressive Disorder; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning (lower score indicates worse functioning); SLC-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; GSI, Global Severity Index for the SLC-90-R; SOM, Somatization subscale for the SLC-90-R; TIV, mean total intracranial volume; GM, grey matter.

The distribution of TBI severity classifications, severity of anxiety and depression scores, and biological sex across and within-groups is summarized in Table 2. The ratio of males to females was not balanced across groups, as indicated by the significant association between group and biological sex, χ2(4, N=121) = 6.282, p=0.012. The ratio of males to females was balanced in the TBI-only group, with 47.5% males (28 of 59 participants). The TBI-PNES group had disproportionately more females than males, with males accounting for 25.8% of the group (16 of 62 participants). There were no significant associations between group and most severe TBI, χ2(4, N=121) = 2.921, p=0.571. Both the TBI-only and TBI-PNES groups were comprised of approximately equal proportions of participants with mild, moderate, and severe TBI. Mild TBI comprised 71.9% of the total study sample, accounting for 72.9% of the TBI-only group and 71.0% of the TBI-PNES group. A history of moderate TBI accounted for 18.1% of all participants, while severe TBI was reported in 5% of the study sample (3 participants in each group). Most TBI-only participants reported mild depression (n=34), followed by moderate (n=10) and minimal (n=8). Only 6 TBI-only participants reported severe depression. TBI-PNES participants’ distribution of BDI classification was more distributed; moderate (n=23) and severe (n=18) depression were predominant, with equal numbers reporting mild (n=10) and minimal (n=10) depression. Severe anxiety was reported by the majority of TBI-PNES participants (n=30), while TBI-only participants predominantly reported mild anxiety symptoms (n=28). Mild and Moderate anxiety symptoms were comparable in both groups.

Table 2.

The association of study group with biological sex, most severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), and severity of anxiety and depression scores.

| TBI-only | TBI-PNES | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group*Sex | χ2(4, N=121) = 6.282, p=0.012* | ||||

| Male | Count | 28 | 16 | 44 | |

| % | 47.5 | 25.8 | 36.4 | ||

| Female | Count | 29 | 44 | 73 | |

| % | 49.2 | 71.0 | 60.3 | ||

| Null, Not Reported | Count | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| % | 3.4% | 3.2 | 3.3 | ||

| Group*Most Severe TBI | χ2(4, N=121) = 2.921, p=0.571 | ||||

| Mild | Count | 43 | 44 | 87 | |

| % | 72.9 | 71.0 | 71.9 | ||

| Moderate | Count | 12 | 10 | 22 | |

| % | 20.3 | 16.1 | 18.1 | ||

| Severe | Count | 3 | 3 | 6 | |

| % | 5.1 | 4.8 | 5.0 | ||

| Null, Not Reported | Count | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| % | 1.7 | 4.1 | 5.0 | ||

| Group*BDI | χ2(3, N=119) = 24.37, p < .0001* | ||||

| Mild depression | Count | 34 | 10 | 44 | |

| % | 58.6% | 16.4% | 37.0% | ||

| Minimal depression | Count | 8 | 10 | 18 | |

| % | 13.8% | 16.4% | 15.1% | ||

| Moderate depression | Count | 10 | 23 | 33 | |

| % | 17.2% | 37.7% | 27.7% | ||

| Severe depression | Count | 6 | 18 | 24 | |

| % | 10.3% | 29.5% | 20.2% | ||

| Group*BAI | χ2(3, N=119) = 32.32, p < 0.0001 | ||||

| Mild anxiety | Count | 28 | 5 | 33 | |

| % | 48.3% | 8.2% | 27.7% | ||

| Minimal anxiety | Count | 10 | 9 | 19 | |

| % | 17.2% | 14.8% | 16.0% | ||

| Moderate anxiety | Count | 14 | 17 | 31 | |

| % | 24.1% | 27.9% | 26.1% | ||

| Severe anxiety | Count | 6 | 30 | 36 | |

| % | 10.3% | 49.2% | 30.3% | ||

Abbreviations: TBI, traumatic brain injury; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures; Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI; Beck Depression Inventory, BDI.

3.2. Brain Atrophy: Voxel-based morphometry results

The size and location of VBM clusters implicated in significant between-group differences are summarized in Table 3. For the voxelwise GLM that investigated the effect of group and TBI severity on GMV, there was a main effect for TBI severity, but the interaction of Group*TBI severity was not significant. Participants with moderate TBI severity demonstrated decreased GMV in regions implicated in emotional regulation, as compared to those with mild TBI (Table 3). Patients with severe TBI had decreased GMV in the left cerebellum (Crus I), as compared to those with moderate TBI across both groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of significant results for voxel-wise general linear models investigating grey matter volume (differences in traumatic brain injury (TBI) participants with and without psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES).

| Significant cluster region(s) | Cluster size (mm3) | MNI coordinates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | ||||

| GMV differences | ||||||

| Decreased GMV for Moderate < Mild TBI Severity | ||||||

| R Temporal Fusiform cortex, posterior division | 1444 | 36 | −24 | −35 | ||

| R Inferior Temporal Gyrus/fusiform cortex - anterior | 35 | −3 | −38 | |||

| L Precuneus | 4614 | −2 | −59 | 26 | ||

| R Precuneus | 2 | −50 | 66 | |||

| L Mid Cingulate | −5 | −38 | 54 | |||

| R Parahippocampal Gyrus | 539 | 23 | −26 | −27 | ||

| L Inferior Parietal Lobule | 142 | −30 | −48 | 45 | ||

| Decreased GMV for Severe < Moderate TBI Severity | ||||||

| L Cerebellum (Crus 1) | 388 | −40 | −63 | −27 | ||

| Decreased GMV for TBI-PNES < TBI-only | ||||||

| L Inferior Frontal Gyrus (LIFG), pars opercularis | 190 | −44 | 5 | 17 | ||

| R Cerebellum (VIII) | 4.857 | −57 | −45 | 33 | ||

| Interaction of GMV*Anxiety (BAI scores) | ||||||

| Decreased GMV for TBI-PNES < TBI-only | ||||||

| L Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis | 7 | −45 | 6 | 18 | ||

| Interaction of GMV*Depression (BAI scores) | ||||||

| Decreased GMV for TBI-PNES < TBI-only | ||||||

| L Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis | 62 | −45 | 6 | 18 | ||

| Interaction of GMV*GAF scores | ||||||

| Decreased GMV for TBI-PNES < TBI-only | ||||||

| L Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis | 7 | −42 | 4.5 | 16.5 | ||

| L Parahippocampal gyrus | 9 | −18 | −25.5 | −21 | ||

Logarithmically-scaled Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement (TFCE) p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the familywise error rate (FWE), and considered significant at p<0.05FWE. Significant clusters are listed with atlas labels, statistical values, and Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates (x, y, z).

Abbreviations: TBI, traumatic brain injury; PNES, psychogenic non-epileptic seizures; L, left; R, right; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning.

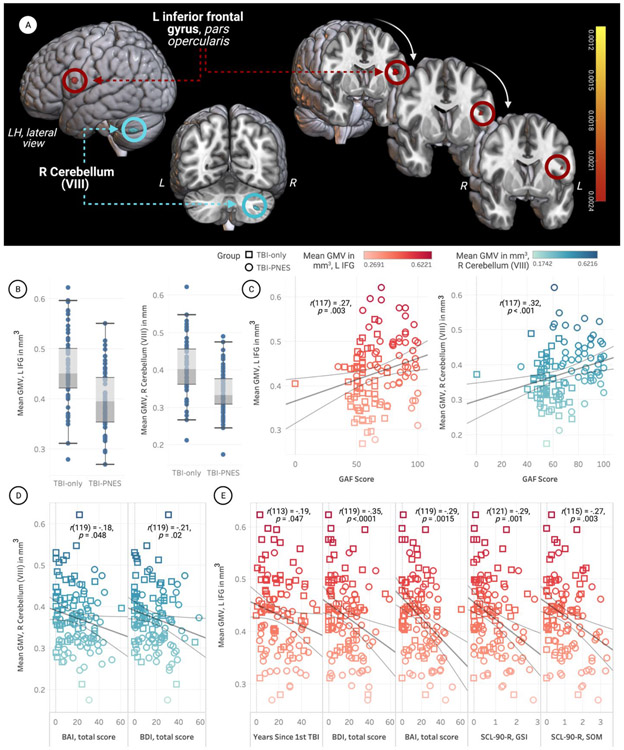

Compared to TBI-only, TBI-PNES demonstrated significantly decreased GMV in the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG) pars opercularis and the right cerebellum VIII (Fig.1 A, B). Mean GMV in the both the LIFG [r(117) = 0.27; p=0.003], and right cerebellum [r(117) = 0.32; p<0.001] clusters positively correlated with GAF scores (higher scores indicate better functioning) (Fig.1C, D), and negatively correlated with anxiety and depression scores (Fig.1E, F). Mean GMV in the LIFG was also negatively correlated with the SLC-90-R GSI and SOM subscale scores (Fig.1F). The interaction between voxel-wise GMV and anxiety (BAI scores) GMV*anxiety was associated with significant group differences in the LIFG. The LIFG was also implicated in the interaction between voxel-wise GMV and BDI scores. The cluster was smaller for anxiety scores on the BAI (cluster size=7mm3) and larger when modeled using depression scores on the BDI (cluster size=62mm3). The LIFG cluster was no longer significant when BAI and BDI were instead modeled as nuisance covariates rather than explanatory variables.

Figure 1. Participants with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) had decreased grey matter volume (GMV) in the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG) and right cerebellum (VIII).

The open-source software MRIcroGL (McCausland Center for Brain Imaging, University of South Carolina; https://www.mccauslandcenter.sc.edu/mricrogl/) was used to overlay significant clusters on the MNI template for 3D renderings. The figure was created using BioRender and plots were created using Tableau. For each plot, the shapes of data points correspond to group and colors correspond to mean GMV of the relevant cluster (see legends).

A. Decreased GMV in LIFG and right cerebellum (VIII) of TBI-PNES participants. The significant cluster located in the LIFG is presented on coronal slices in the rightmost portion of the figure, while the cluster in the right cerebellum is presented on the left.

B. Box-and-whisker plots of mean parameter estimates for participants in both groups. TBI-PNES participants’ mean GMV was significantly lower in the LIFG and right cerebellum (VIII). Vertical bars represent means and whiskers indicate standard deviation. Mean GMV in the LIFG was 0.40 mm3 for TBI-PNES and 0.46 mm3 for the TBI-only group. Mean GMV in the cerebellar cluster was 0.34 mm3 for TBI-PNES and 0.41 mm3 for the TBI-only group

C. Significant positive correlation between GAF scores and mean beta values (GMV) extracted from within the significant LIFG (p=0.003) and right cerebellum clusters (p<0.001).

D. Mean parameter estimates for the right cerebellar cluster were negatively correlated with both anxiety scores (BAI) and depression scores (BDI).

E. Mean parameter estimates for the LIFG were negatively correlated with years since first TBI, anxiety scores (BAI) and depression scores (BDI), and the SCL-90-R GSI and SOM subscale scores.

Abbreviations: Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, PNES; Traumatic brain injury, TBI; Grey matter volume, GMV; Left, L; Right, R; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI; Beck Depression Inventory, BDI; Global Assessment of Functioning, GAF; Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, SCL-90-R; SLC-90-R Global Severity Index, SCL-90-R GSI; SCL-90-R Somatization subscale, SCL-90-R SOM.

3.3. Altered Cortical Morphology: Surface-based morphometry results

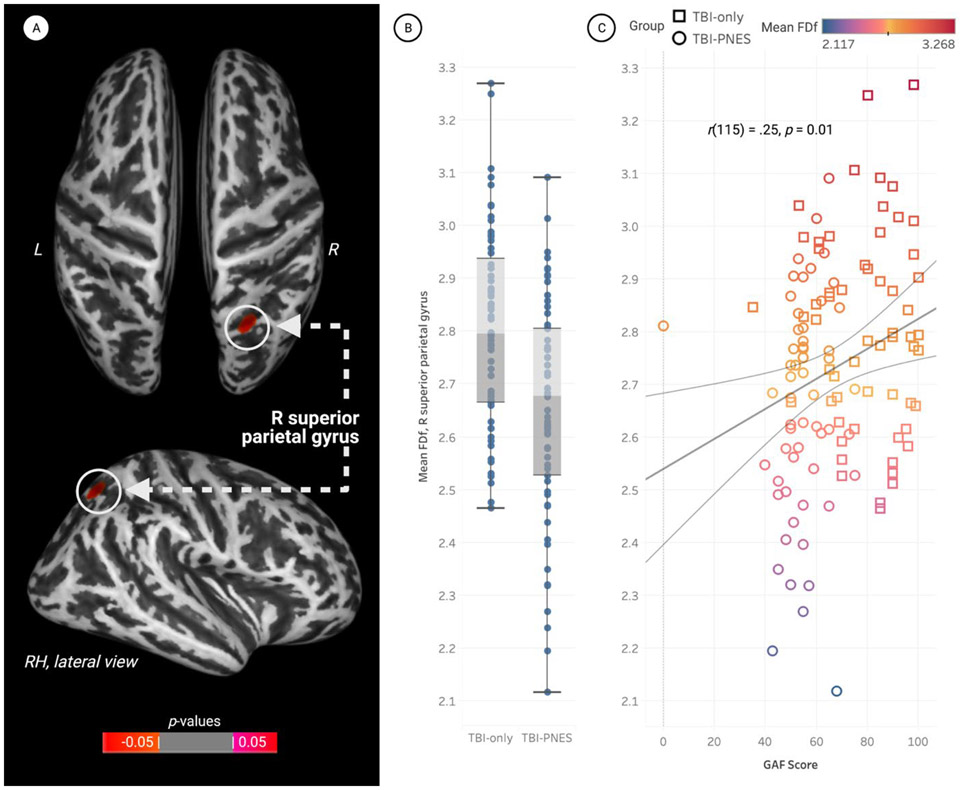

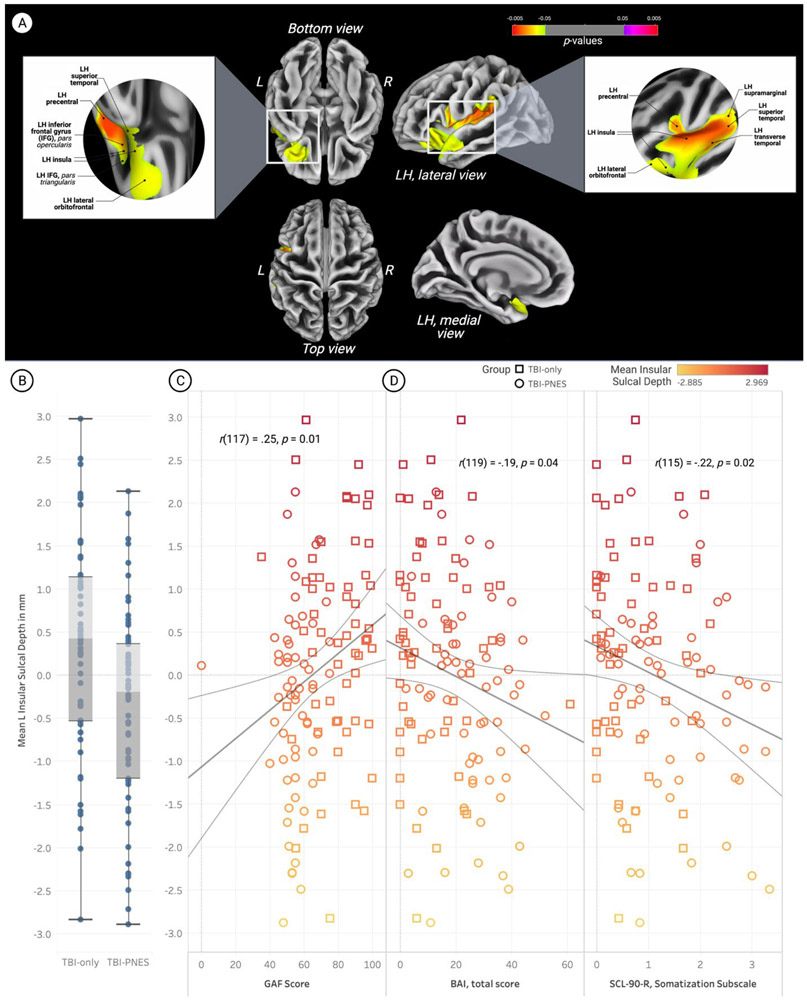

There were no significant differences in cortical thickness and gyrification index data for TBI-PNES vs. TBI-only. Decreased fractal dimension (i.e., FDf) was observed in TBI-PNES participants relative to TBI-only in the right superior parietal gyrus, pFWE<0.05 (Fig.2). Mean FDf in the right superior parietal gyrus positively correlated with GAF scores [r(115) = 0.25; p=0.01], with no other associations with psychological measures and clinical data reaching statistical significance (including age). Participants with TBI-PNES had decreased sulcal depth (pFWE<0.05) in a left hemisphere cluster encompassing the insula cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and the superior and transverse temporal, supramarginal, and precentral gyri (Fig.3). Mean insula sulcal depth was negatively correlated with SCL-90-R SOM [r(115) = −0.22; p=0.02], and anxiety as indicated by the BAI [r(119) = −0.19; p=0.04]. Mean insula sulcal depth was positively correlated with GAF scores [r(117) = 0.25; p=0.01]. Mean FDf in the superior parietal gyrus and mean sulcal depth in the insula were not correlated with age.

Figure 2. Participants with a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) with concurrent psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) demonstrated significantly reduced fractal dimension in the right parietal gyrus.

Data were visualized using CAT12’s surface overlay functions. The figure was created using BioRender and plots were created using Tableau.

A. Whole brain vertex-wise statistical maps demonstrating significantly reduced mean fractal dimension (FDf) in the right parietal gyrus of participants with TBI-PNES (pFWE<0.05). Data are presented on the inflated cortical surface (dark grey = sulci; light grey = gyri), and are visualized for the superior (top) and right lateral (bottom) surfaces. Red clusters represent brain regions where participants with TBI-PNES had significantly lower cortical complexity (mean FDf) than participants with TBI-only, indicating reduced amount of cortical folds and decreased gyrification.

B. Box-and-whisker plots of mean parameter estimates for participants in both groups. Mean FDf in the right superior parietal gyrus was significantly lower in the TBI-PNES group. Vertical bars represent means and whiskers indicate standard deviation. The mean FDf index within the right superior parietal gyrus was 2.65±0.21 for TBI-PNES, ranging from a minimum FDf of 2.12 to 3.09. For TBI-only, the FDf index within this cluster was 2.80±0.19, ranging from a minimum FDf of 2.46 to 3.27.

C. Significant positive correlation between Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores and mean beta values (FDf) extracted from within the significant cluster in the right superior parietal gyrus, p=0.01. Shapes of data points correspond to group, and colors correspond to mean FDf (see legends).

Abbreviations: Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, PNES; Traumatic brain injury, TBI; Fractal Dimensionality, FDf; Left, L; Right, R; RH, right hemisphere; Global Assessment of Functioning, GAF.

Figure 3. Participants with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) and traumatic brain injury (TBI) had decreased sulcal depth in a left hemisphere cluster encompassing the insular cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and the superior and transverse temporal, supramarginal, and precentral gyri.

Data were visualized using CAT12’s surface overlay functions. The figure was created using BioRender and the plots were created using Tableau.

D. Whole brain vertex-wise statistical maps demonstrating significantly reduced mean sulcal depth in the left insula of participants with TBI-PNES (pFWE<0.05). Data presented on the inflated cortical surface (dark grey = sulci; light grey = gyri). The location of the significant cluster is visualized for the brain’s inferior and superior inferior surfaces, as well as the lateral and medial views of the left hemisphere. Orange to yellow clusters represent brain regions where participants with TBI-PNES had significantly lower sulcus depth than participants with TBI-only.

E. Box-and-whisker plots of mean parameter estimates for participants in both groups. Mean sulcal depth in the insula cortex was significantly lower in the TBI-PNES group. Vertical bars represent means and whiskers indicate standard deviation. Mean sulcal depth within the left insula region was 16.95±1.18 mm for TBI-PNES participants, ranging from a minimum of 14.27 mm to a maximum of 19.51 mm. For TBI-only participants, mean sulcal depth within this cluster was 17.69±1.20 mm, ranging from a minimum of 14.57 mm to a maximum of 20.22 mm.

F. Left insula sulcal depth was positively correlated with Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores.

G. Left insula sulcal depth was negatively correlated with anxiety scores, as measured by the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI).

H. Left insula sulcal depth was negatively correlated with distress arising from bodily perceptions such as PNES events, as measured by the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90-R) somatization subscale scores. Shapes of data points correspond to group, and colors correspond to mean left insula sulcal depth (see legends).

Abbreviations: Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures, PNES; Traumatic brain injury, TBI; Grey matter volume, GMV; Left, L; Right, R; Left hemisphere, LH; Square root, sqrt; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI; Beck Depression Inventory, BDI; Global Assessment of Functioning, GAF; Symptom Checklist-90-Revised, SCL-90-R; SLC-90-R Global Severity Index, SCL-90-R GSI; SCL-90-R Somatization subscale, SCL-90-R SOM.

4. DISCUSSION

This is the largest to date prospective study of brain morphology in participants with TBI and with or without subsequent PNES. The computational dissection provides a more comprehensive assessment than prior studies, encompassing GMV, cortical thickness, sulcal depth, and fractal dimension. Compared to TBI-only, participants with TBI-PNES showed atrophy of the LIFG and right cerebellum (VIII), both regions implicated in emotional regulation and processing.34,35 The left posterior IFG (pars opercularis) is implicated in executive control and response inhibition characteristic of trait anxiety.36,37 In the present study, the LIFG was additionally implicated in the voxelwise interaction with anxiety, depression, and GAF scores. Interestingly, there were no significant differences in GMV when anxiety and depression scores were modeled as nuisance covariates, indicating that group differences in these measures may explain neuroanatomic differences. Decreased fractal dimensionality in TBI-PNES was observed in regions encompassing the right superior parietal gyrus, with cluster boundaries overlapping with the border of the temporoparietal junction (TPJ). Decreased insula sulcal depth in TBI-PNES is consistent with prior studies showing atrophy and decreased folding of the insula in patients with neurological and/or psychiatric disorders characterized by anxiety and depressive symptoms.38 In these patients, the TPJ and insula may work in concert to link neurobiological phenomena, perceptions, and prior experience to the clinical manifestations of PNES.38,39

Overall, participants with TBI-PNES showed brain atrophy and aberrant cortical folding in brain regions implicated in emotional processing, regulation, and response inhibition. Findings from prior studies of network and connectivity aberrations in PNES have underscored the importance of studying the cytoarchitecture that underlies these connections.1,12,13 Characterizing the morphological changes that characterize PNES in TBI participants is an important initial step for investigations aimed at discerning the timing of these changes (i.e., cause or consequence) and identifying appropriate treatment.

The present study expanded upon prior studies with a more comprehensive assessment of cortical topography. Aberrant cortical folding in TBI-PNES may contribute to the functional aberrations of the relevant sulci. Decreased sulcal depth may stem from the local shrinkage of gyri but could also be the product of global tissue changes or shrinkages in distal regions. Cortical complexity measured by fractal dimensionality is an index that combines sulcal depth, frequency of cortical folding, and degree of gyral convolution detected in the cerebral cortex. Cortical folds primarily develop during the third trimester of pregnancy and remain relatively constant throughout the remainder of one’s life.40 GMV and cortical thickness, both more widely used measures of brain morphometry, vary considerably in health and disease. Due to their fluctuation over the lifespan, the onset of GMV and cortical thickness changes thought to underlie functional or network changes cannot be pinpointed in time.40 As a result, FDf and sulcal depth are more sensitive structural indices than GMV and cortical thickness. Group differences in FDf might indicate neurodevelopmental disturbances during early cortical development, or impact of early life events or trauma.

Unlike the two prior neuromorphometric studies in PNES, the present study did not detect significant between-group differences in cortical thickness.18,19 The two prior studies employed less stringent thresholds and smaller sample sizes, and they did not control for the presence or absence of TBI. Their use of the healthy control group also differed from our TBI-only control, in which we compared PNES to patients with similar clinical history and severity of TBI. Since both prior studies were conducted 6+ years ago, the present study also benefits from advancements in scanning hardware, sequence design, and computational approaches to measuring brain morphology. The present study’s sample size (N=121) was substantially larger than the two prior brain morphology studies in PNES.18,19 All participants in our study had prior history of TBI; mild, moderate, and severe TBI were equally distributed across both cohort samples. This design controlled for precipitating brain insult and psychiatric symptoms alike, though patients with PNES reported higher anxiety and depression symptoms. The two prior brain morphometry studies of PNES reported exclusion of patients with any neuropsychiatric comorbidities, which is very uncommon in the PNES population. Our study did not exclude on the basis of these criteria, a decision that primarily stemmed from the high occurrence of both neuropsychiatric comorbidities in the PNES population.6 Our study’s participant age range was limited to those 18-60 years to avoid the confound of neurodegenerative age-related atrophy. Brain atrophy and cortical morphology aberrations did not correlate with age, providing more confidence that group differences in morphology were not driven by age-related declines.

Patients with PNES typically have numerous comorbidities. Patients’ comorbid, concurrent, and often intertwined psychiatric, neurological, and psychosocial problems contribute to PNES’ neuropathophysiology and may manifest in structural brain changes. The present study treated PNES as a homogeneous neuropsychiatric disorder to find neural correlates of PNES, arguably both a strength and a limitation, given the gaps in the growing body of literature. Though data on patients’ psychiatric comorbidities were acquired, the severity and duration of most disorders was not measured for several reasons pertaining to study aims and practical constraints. Future studies that focus on specific psychiatric comorbidities and their impact on PNES could fill these gaps. Further, the present study recruited patients with PNES with a minimum of one PNES event in the preceding year. This criterion ultimately limited the ability to study patients with rare events, who may have varying pathophysiology with possible impact on neuromorphometry. Limitations include the cross-sectional design, which allowed investigating between-group differences but did not permit making causal inferences. A large, prospective, longitudinal study with repeated scans over decades could allow determining the location and timing of brain volume and cortical morphology changes in relation to PNES development in those with brain injury. A comparison group of lone depression or lone PTSD could add insights on differences between clinical samples without PNES and/or TBI. Multimodal imaging studies that incorporate functional, structural, and connectivity analyses would provide a more comprehensive view of functional neuropathophysiology in participants with PNES.

Conclusion

The present study offers novel insights on the neuroanatomic correlates of PNES. While the common comorbidities of anxiety and depression have been well documented in PNES, less is known about the neuropathology of patients with PNES. Identifying underlying neural correlates of PNES may be an important step to developing more precise treatments (i.e., precision medicine). The present study’s findings indicate that structural alterations may underlie the functional and connectivity changes identified in previous PNES studies, though multimodal studies are needed to fully understand these phenomena. Based on the timing and stability of FDf and sulcal depth changes, aberrations in brain morphology may originate early in cortical development. Thus, future studies could probe whether neurodevelopmental factors render a person more likely to have PNES. Multi-site studies and datasets, such as in the ENIGMA-type approach, could facilitate comparisons of other cohorts. In summary, based on the literature to date, the convergence of environmental, developmental, and neurobiological factors may coalesce to form PNES’ neuropathophysiological substrate. Currently, it is unknown if the relationship of brain and behavior, comorbidities, brain atrophy and altered surface topography may be consequences or causes of PNES. The present findings further the field’s ongoing search for a biomarker that characterizes and predicts PNES.

KEY POINTS.

Few studies have investigated the link between brain structure and function in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES).

The diverging findings of two such studies to date may highlight differences in the studied cohorts.

TBI is an effective model for examining neural substrates that link PNES and psychiatric symptoms grounded in emotion dysregulation.

TBI-PNES participants showed brain atrophy and aberrant cortical folding in brain regions implicated in emotional regulation.

The convergence of environmental, developmental, and neurobiological factors may coalesce to reflect PNES’ neuropathophysiological substrate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Epilepsy Research Program under Award No. W81XWH-17-1-0619 to WCL and JPS. Ayushe A. Sharma is supported by an institutional training grant (5T32NS061788-14) from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke through the University of Alabama at Birmingham Department of Neurobiology's Pre-doctoral Training Program in Cognition and Cognitive Disorders (C&CD). The authors thank Jasper J. Odell for training and assistance in data visualization and graphical rendering, which was used to create Figures 1-3.

The contents of this article do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government. The U.S. Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity, 820 Chandler Street, Fort Detrick MD 21702-5014 is the awarding and administering acquisition office. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Providence VA Medical Center, Providence RI, Rhode Island Hospital, and at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

DISCLOSURE OF CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A.M. Goodman is funded by US Department of Defense grant W81XWH-17-1-0619.

J.B. Allendorfer receives salary support from the U.S. Department of Defense study, salary support from state of Alabama “Carly’s Law” unrelated to current study, research support from the Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute at UAB, and is a consultant for LivaNova Inc.

W.C. LaFrance Jr., has served on the editorial boards of Epilepsia, Epilepsy & Behavior, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, and Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences; receives editor’s royalties from the publication of Gates and Rowan’s Nonepileptic Seizures, 3rd ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2010) and 4th ed. (2018); receives author’s royalties for Taking Control of Your Seizures: Workbook and Therapist Guide (Oxford University Press, 2015); has received research support from the Department of Defense (DoD W81XWH-17-0169), NIH (NINDS 5K23NS45902 [PI]), Providence VAMC, Center for Neurorestoration and Neurorehabilitation, Rhode Island Hospital, the American Epilepsy Society (AES), the Epilepsy Foundation (EF), Brown University and the Siravo Foundation; serves on the Epilepsy Foundation New England Professional Advisory Board, the Functional Neurological Disorder Society Board of Directors, the American Neuropsychiatric Association Advisory Council; has received honoraria for the AES Annual Meeting; has served as a clinic development consultant at University of Colorado Denver, Cleveland Clinic, Spectrum Health, Emory University, Oregon Health Sciences University and Vanderbilt University; and has provided medico legal expert testimony.

J.P. Szaflarski is funded by NIH, NSF, DoD, State of Alabama, Shor Foundation for Epilepsy Research, UCB Pharma Inc., NeuroPace Inc., Greenwich Biosciences Inc., Biogen Inc., Xenon Pharmaceuticals, and Serina Therapeutics Inc., has served on consulting/advisory boards for Greenwich Biosciences Inc., NeuroPace, Inc., Serina Therapeutics Inc., LivaNova Inc., UCB Pharma Inc., iFovea, AdCel Biopharma LLC, and Elite Medical Experts LLC and serves as an editorial board member for Epilepsy & Behavior, Journal of Epileptology (associate editor), Epilepsy & Behavior Reports (associate editor), Journal of Medical Science, Epilepsy Currents (contributing editor), and Folia Medica Copernicana.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- ASMs

anti-seizure medications

- TRE

treatment-resistant epilepsy

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- VBM

voxel-based morphometry

- GMV

grey matter volume

- SBM

surface-based morphometry

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- BAI

Beck Anxiety Inventory

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory-II

- SCL-90-R

Symptom Checklist-90-Revised

- GSI

Global Severity Index of the SCL-90-R

- SOM

Somatization subscale of the SCL-90-R

- GAF

Global Assessment of Functioning scale

- CAT12

Computational Anatomy Toolbox

- SPM12

Statistical Parametric Mapping

- TIV

total intracranial volume

- FDf

fractal dimensionality

- GM

grey matter

- WM

white matter

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- GLM

general linear model

- TFCE

Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement

- FWE

family-wise error

- TPJ

temporoparietal junction

Footnotes

None of the other authors have any specific conflicts of interest to report.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The authors confirm that they have read the Journal’s position on ethical publication, and this report is consistent with those guidelines.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balachandran N, Goodman AM, Allendorfer JB, Martin AN, Tocco K, Vogel V, et al. Relationship between neural responses to stress and mental health symptoms in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures after traumatic brain injury. Epilepsia. 2021; 62(1):107–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez DL, LaFrance WC Jr. Nonepileptic seizures: An updated review. Vol. 21, CNS Spectrums. Cambridge University Press; 2016. p. 239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGonigal A, Russell AJC, Mallik AK, Oto M, Duncan R. Use of short term video EEG in the diagnosis of attack disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004; 75(5):771–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuber M, Jamnadas-Khoda J, Broadhurst M, Grunewald R, Howell S, Koepp M, et al. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizure manifestations reported by patients and witnesses. Epilepsia. 2011; 52(11):2028–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anzellotti F, Dono F, Evangelista G, Di Pietro M, Carrarini C, Russo M, et al. Psychogenic Non-epileptic Seizures and Pseudo-Refractory Epilepsy, a Management Challenge. Vol. 11, Frontiers in Neurology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2020. p. 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mökleby K, Blomhoff S, Malt UF, Dahlström A, Tauböll E, Gjerstad L. Psychiatric comorbidity and hostility in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures compared with somatoform disorders and healthy controls. Epilepsia. 2002; 43(2):193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szaflarski JP, Hughes C, Szaflarski M, Ficker DM, Cahill WT, Li M, et al. Quality of life in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2003; 44(2):236–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman ES, Markand ON. Psychodynamics and psychiatric diagnoses of pseudoseizure subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1996; 153(1):57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S, Allendorfer JB, Gaston TE, Griffis JC, Hernando KA, Knowlton RC, et al. White matter diffusion abnormalities in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Brain Res. 2015; 1620:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van der Kruijs SJM, Jagannathan SR, Bodde NMG, Besseling RMH, Lazeron RHC, Vonck KEJ, et al. Resting-state networks and dissociation in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Psychiatr Res. 2014; 54(1):126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perez DL, Nicholson TR, Asadi-Pooya AA, Bègue I, Butler M, Carson AJ, et al. Neuroimaging in Functional Neurological Disorder: State of the Field and Research Agenda. Vol. 30, NeuroImage: Clinical. Elsevier Inc.; 2021. p. 102623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barzegaran E, Carmeli C, Rossetti AO, Frackowiak RS, Knyazeva MG. Weakened functional connectivity in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) converges on basal ganglia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016; 87(3):332–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding J, An D, Liao W, Wu G, Xu Q, Zhou D, et al. Abnormal functional connectivity density in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2014; 108(7):1184–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szaflarski JP, LaFrance WC Jr. Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures (PNES) as a network disorder - Evidence from neuroimaging of functional (psychogenic) neurological disorders. Vol. 18, Epilepsy Currents. American Epilepsy Society; 2018. p. 211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-Based Morphometry—The Methods. Neuroimage. 2000; 11(6):805–21. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10860804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahnke R, Yotter RA, Gaser C. Cortical thickness and central surface estimation. Neuroimage. 2013; 65:336–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yotter RA, Nenadic I, Ziegler G, Thompson PM, Gaser C. Local cortical surface complexity maps from spherical harmonic reconstructions. Neuroimage. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labate A, Cerasa A, Mula M, Mumoli L, Gioia MC, Aguglia U, et al. Neuroanatomic correlates of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A cortical thickness and VBM study. Epilepsia. 2012; 53(2):377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ristić AJ, Daković M, Kerr M, Kovačević M, Parojčić A, Sokić D. Cortical thickness, surface area and folding in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2015; 112:84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LaFrance WC Jr, Deluca M, MacHan JT, Fava JL. Traumatic brain injury and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures yield worse outcomes. Vol. 54, Epilepsia. 2013. p. 718–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salinsky M, Rutecki P, Parko K, Goy E, Storzbach D, O’Neil M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and traumatic brain injury attribution in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic or epileptic seizures: A multicenter study of US veterans. Epilepsia. 2018; 59(10):1945–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popkirov S, Carson AJ, Stone J. Scared or scarred: Could ‘dissociogenic’ lesions predispose to nonepileptic seizures after head trauma?. Vol. 58, Seizure. 2018. p. 127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hellewell SC, Beaton CS, Welton T, Grieve SM. Characterizing the risk of depression following mild traumatic brain injury: A meta-analysis of the literature comparing chronic mTBI to non-mTBI populations. Vol. 11, Frontiers in Neurology. 2020. p. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Steer RA BG. Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace. Toronto; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Psychiatric Publishing. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaFrance WC Jr, Baker GA, Duncan R, Goldstein LH, Reuber M. Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A staged approach: A report from the International League Against Epilepsy Nonepileptic Seizures Task Force. Epilepsia. 2013; 54(11):2005–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988; 56(6):893–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derogatis L Symptom Checklist 90-R: administration, scoring, and procedures manual II. 2nd ed. Baltimore Clin Psychom Res. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall RCW. Global Assessment of Functioning: A Modified Scale. Psychosomatics. 1995; 36(3):267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goodman AM, Allendorfer JB, Blum AS, Bolding MS, Correia S, Ver Hoef LW, et al. White matter and neurite morphology differ in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020; 7(10):1973–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma AA, Nenert R, Allendorfer JB, Gaston TE, Grayson LP, Hernando K, et al. A preliminary study of the effects of cannabidiol (CBD) on brain structure in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav Reports. 2019; 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashburner J A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage. 2007; 38(1):95–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006; 31(3):968–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu Y, Dolcos S. Trait anxiety mediates the link between inferior frontal cortex volume and negative affective bias in healthy adults. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2017; 12(5):775–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein AP, Ulmer JL, Quinet SA, Mathews V, Mark LP. Nonmotor functions of the cerebellum: An introduction. Am J Neuroradiol. 2016; 37(6):1005–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fales CL, Becerril KE, Luking KR, Barch DM. Emotional-stimulus processing in trait anxiety is modulated by stimulus valence during neuroimaging of a working-memory task. Cogn Emot. 2010; 24(2):200–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shang J, Fu Y, Ren Z, Zhang T, Du M, Gong Q, et al. The common traits of the ACC and PFC in anxiety disorders in the DSM-5: Meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. PLoS One. 2014; 9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatton SN, Lagopoulos J, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Bennett MR, Hickie IB. Correlating anterior insula gray matter volume changes in young people with clinical and neurocognitive outcomes: an MRI study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012; 12(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voon V, Cavanna AE, Coburn K, Sampson S, Reeve A, Curt Lafrance W. Functional neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of functional neurological disorders (Conversion disorder). J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016; 28(3):168–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hogstrom LJ, Westlye LT, Walhovd KB, Fjell AM. The structure of the cerebral cortex across adult life: Age-related patterns of surface area, thickness, and gyrification. Cereb Cortex. 2013; 23(11):2521–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]