Abstract

Background

This is the first update of a review published in 2010. While calcium channel blockers (CCBs) are often recommended as a first‐line drug to treat hypertension, the effect of CCBs on the prevention of cardiovascular events, as compared with other antihypertensive drug classes, is still debated.

Objectives

To determine whether CCBs used as first‐line therapy for hypertension are different from other classes of antihypertensive drugs in reducing the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events.

Search methods

For this updated review, the Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the following databases for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) up to 1 September 2020: the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2020, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, and ClinicalTrials.gov. We also contacted the authors of relevant papers regarding further published and unpublished work and checked the references of published studies to identify additional trials. The searches had no language restrictions.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing first‐line CCBs with other antihypertensive classes, with at least 100 randomised hypertensive participants and a follow‐up of at least two years.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors independently selected the included trials, evaluated the risk of bias, and entered the data for analysis. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. We contacted study authors for additional information.

Main results

This update contains five new trials. We included a total of 23 RCTs (18 dihydropyridines, 4 non‐dihydropyridines, 1 not specified) with 153,849 participants with hypertension. All‐cause mortality was not different between first‐line CCBs and any other antihypertensive classes. As compared to diuretics, CCBs probably increased major cardiovascular events (risk ratio (RR) 1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.00 to 1.09, P = 0.03) and increased congestive heart failure events (RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.51, moderate‐certainty evidence). As compared to beta‐blockers, CCBs reduced the following outcomes: major cardiovascular events (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.92), stroke (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.88, moderate‐certainty evidence), and cardiovascular mortality (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.99, low‐certainty evidence). As compared to angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, CCBs reduced stroke (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.99, low‐certainty evidence) and increased congestive heart failure (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.28, low‐certainty evidence). As compared to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), CCBs reduced myocardial infarction (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.94, moderate‐certainty evidence) and increased congestive heart failure (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.36, low‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

For the treatment of hypertension, there is moderate certainty evidence that diuretics reduce major cardiovascular events and congestive heart failure more than CCBs. There is low to moderate certainty evidence that CCBs probably reduce major cardiovascular events more than beta‐blockers. There is low to moderate certainty evidence that CCBs reduced stroke when compared to angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and reduced myocardial infarction when compared to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), but increased congestive heart failure when compared to ACE inhibitors and ARBs. Many of the differences found in the current review are not robust, and further trials might change the conclusions. More well‐designed RCTs studying the mortality and morbidity of individuals taking CCBs as compared with other antihypertensive drug classes are needed for patients with different stages of hypertension, different ages, and with different comorbidities such as diabetes.

Plain language summary

Calcium channel blockers versus other classes of drugs for hypertension

What is the aim of this review?

In this first update of a review published in 2010, we wanted to find out if calcium channel blockers (CCBs) can prevent harmful cardiovascular events such as stroke, heart attack, and heart failure when compared to other antihypertensive (blood pressure‐lowering) medications used for individuals with raised blood pressure (hypertension).

Background

Appropriate lowering of elevated blood pressure in individuals with hypertension can reduce the amount of major complications of hypertension, such as stroke, heart attack, congestive heart failure, and even death. CCBs are used as a first‐line blood pressure‐lowering medication, but whether this is the best way to reduce harmful cardiovascular events has been a matter of debate.

Search date

We collected and analysed all relevant studies up to 01 September 2020.

Study characteristics

We found 23 relevant studies conducted in Europe, North America, Oceania, Israel, and Japan. The studies compared treatment with CCBs versus treatment with other classes of blood pressure‐lowering medications in people with hypertension and included 153,849 participants. Follow‐up of trial participants ranged from 2 to 5.3 years.

Key results

There was no difference in deaths from all causes between CCBs and other blood pressure‐lowering medications. Diuretics probably reduce total cardiovascular events and congestive heart failure more than CCBs. CCBs probably reduce total cardiovascular events more than beta‐blockers. CCBs reduced stroke when compared to angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and reduced heart attack when compared to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), but increased congestive heart failure when compared to ACE inhibitors and ARBs.

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the quality of the evidence as mostly moderate, although more trials are desirable.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Hypertension is a leading cause of death worldwide, and its prevalence has increased dramatically over the past two decades (GBD 2015). In the population‐based ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities) study, hypertension was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and end‐stage renal disease; 25% of all cardiovascular events were attributable to hypertension (Cheng 2014).

Description of the intervention

Antihypertensive therapies have established benefits in reducing the risk for major cardiovascular events. Pharmacotherapy for high blood pressure includes first‐line agents, such as diuretics, angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and non‐first‐line agents, such as beta‐blockers and alpha‐blockers (Whelton 2018).

How the intervention might work

Different classes of antihypertensive drugs have different mechanisms of action. Previous meta‐analysis demonstrated that all major antihypertensive drug classes (diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta‐blockers, and CCBs) caused a similar reduction in coronary heart disease events and stroke for a given reduction in blood pressure (Law 2009). The systematic review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults indicated that thiazides were associated with a lower risk of many cardiovascular outcomes compared with other antihypertensive drug classes (Reboussin 2017). CCBs significantly increased the risk of congestive heart failure as compared to diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs in a review by Thomopoulos(Thomopoulos 2015). One previous review concluded that beta‐blockers reduced total cardiovascular events significantly less than CCBs (Wiysonge 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

The issue of first‐line drug selection is highly relevant for millions of subjects receiving drug therapy for hypertension. The benefits in reducing the risk for major cardiovascular events of any one class of antihypertensive therapies relative to other classes has been a matter of debate. Our first systematic review compared CCBs with other classes of antihypertensive drugs in 2010 (Chen 2010), but since then some head‐to‐head trials of CCBs versus other classes of antihypertensive drugs have been performed. These additional newer trials not included in previous systematic reviews may provide an improved understanding of the relative benefits of each class of antihypertensive therapies. This review update aims to sent the outcome data in a way that best assists clinicians in the choice of a antihypertensive drug.

Objectives

To determine whether CCBs used as first‐line therapy for hypertension are different from other classes of antihypertensive drugs in reducing the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that randomised 100 or more participants and followed participants for at least two years.

Types of participants

We included participants with a baseline blood pressure (BP) of at least 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic, measured in a standard way on at least two occasions, or participants with diabetes mellitus with a BP of more than 135/85 mmHg. If a trial was not limited to participants with elevated BP, it must have reported outcome data separately for participants with elevated BP as defined above.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing first‐line CCBs with other first‐line antihypertensive classes. The majority (> 70%) of participants in all study groups must be taking the assigned drug class after one year. Supplemental drugs from drug classes other than CCBs were allowed as stepped therapy.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcomes of the review were as follows.

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Myocardial infarction (non‐fatal and fatal MI plus sudden or rapid death)

Stroke (non‐fatal and fatal stroke)

Congestive heart failure

Cardiovascular mortality

Major cardiovascular events (MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality)

Secondary outcomes

Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For this update, the Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the following databases without language or publication status restrictions:

the Cochrane Hypertension Specialised Register via the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS‐Web) (searched 01 September 2020);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2020, Issue 1) via CRS‐Web (searched 01 September 2020);

MEDLINE Ovid, MEDLINE Ovid Epub Ahead of Print, and MEDLINE Ovid In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (searched 01 September 2020);

Embase Ovid (searched 01 September 2020);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (searched 01 September 2020);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.it.trialsearch) (searched 01 September 2020).

The Information Specialist modelled subject strategies for databases on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE. Where appropriate, these were combined with subject strategy adaptations of the Highly Sensitive Search Strategy designed by Cochrane for identifying randomised controlled trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0, Box 6.4.c.)(Higgins 2011). The database search strategies are shown for this update in Appendix 1 and from the previous (2010) review in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

The Cochrane Hypertension Information Specialist searched the Hypertension Specialised Register segment (which includes searches of MEDLINE, Embase, and Epistemonikos for systematic reviews) to retrieve existing reviews relevant to this systematic review, so that we could scan their reference lists for additional trials. The Specialised Register also includes searches of CAB Abstracts & Global Health, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, and Web of Science for controlled trials.

We checked the bibliographies of included studies and any relevant systematic reviews identified for further references to relevant trials.

Where necessary, we contacted authors of key papers and abstracts to request additional information about their trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Jiaying Zhu, Ning Chen) independently examined the titles and abstracts of citations identified by the electronic searches for possible inclusion. We retrieved full‐text publications of potentially relevant studies and three review authors (Jiaying Zhu, Jie Zhou and Mengmeng Ma) then independently determined study eligibility. We resolved disagreements about study eligibility by discussion and, if necessary, a fourth review author would arbitrate.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (Jiaying Zhu, Jie Zhou and Mengmeng Ma) independently extracted data using a standard form, and then cross‐checked them. Muke Zhou and Jian Guo confirmed all numeric calculations and graphic interpolations. We resolved any discrepancies by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The review authors (Jiaying Zhu and Mengmeng Ma) independently used the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool to categorize studies as having low,unclear, or high risk of bias for sequence generation, allocation sequence concealment, loss of blinding, selective reporting,incomplete reporting of outcomes, and other potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011a).

Measures of treatment effect

We based quantitative analysis of outcomes on intention‐to‐treat principles as much as possible. For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed results as the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For combining continuous variables (systolic blood pressure reduction, diastolic blood pressure reduction), we used the mean difference (with 95% CI).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual trial. For trials having more than two arms, we only included arms relevant to this review. For trials included more than one intervention group with a single comparator arm, we included both intervention groups.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study investigators in the case of missing data. We based the quantitative analyses of outcomes on intention‐to‐treat results.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used Chi2 and I2statistics to test for heterogeneity of treatment effect among trials.

We assessed values of the I2statistic as follows (Higgins 2011a):

0% to 40%: heterogeneity might not be important;

30% to 60%: moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90%: substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% considerable heterogeneity.

We used the fixed‐effect model when there was homogeneity and used the random‐effects model to test for statistical significance where there was heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess reporting bias following the recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Data synthesis

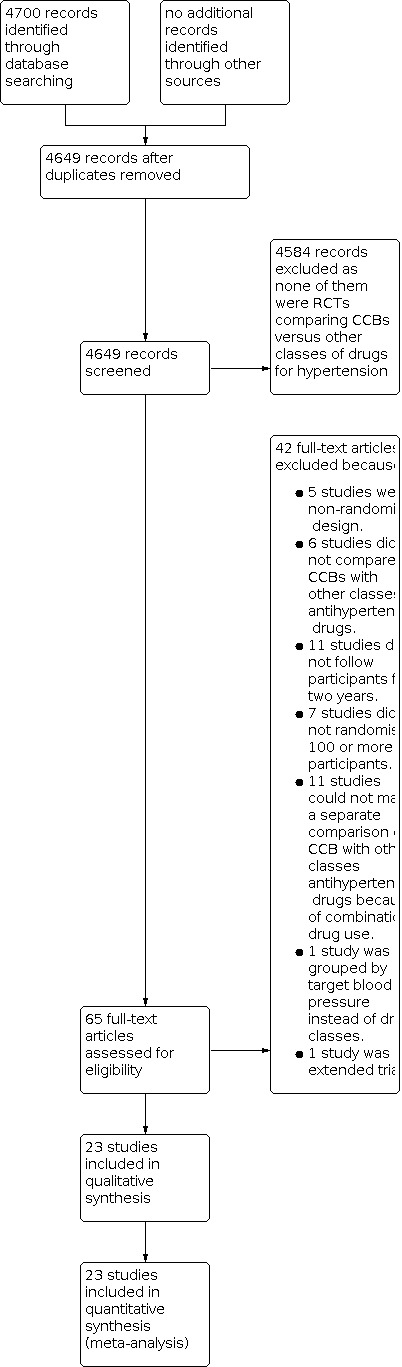

We performed data synthesis and analyses using the Cochrane Review Manager software, RevMan 5.4, We describe data results in tables and forest plots. We also give full details of all studies we include and exclude. We have included a standard PRISMA flow diagram.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If appropriate, we would perform subgroup analyses.

Heterogeneity among participants could be related to: age,gender, baseline blood pressure, target blood pressure, high‐risk participants, participants with comorbid conditions. Heterogeneity in treatments could be related to: form of drugs,dosage of drugs, or duration of therapy.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to examine the effects of excluding studies with a moderate or high risk of bias, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011)

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

In this updated review, we included 'Summary of findings' tables for comparisons that included more than one trial to present the main findings of the review, which included information about the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of effects, and the sum of the available data on the main outcomes (Schünemann 2011a).

We assessed the quality of a body of evidence according to five GRADE considerations (study limitations, inconsistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) (Ryan 2016). We downgraded the evidence from 'high certainty by one level where one of these factors was present to a serious degree and two levels if very serious. We used the methods and recommendations described in Chapter 8 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2011a; Schünemann 2011b). We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of the evidence using footnotes and made comments to aid reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

The results of the search are shown in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1), We identified 4,700 records from database searches. 4,649 records remained after removal of duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, we obtained 65 full‐text articles. Of these articles, we excluded 42 studies based on them not meeting our inclusion criteria.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies for details.

We included 23 RCTs (AASK; ABCD; ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA; CASE‐J; CONVINCE; ELSA; FACET; HOMED‐BP; IDNT; INSIGHT; INVEST; J‐MIC(B); MIDAS; NAGOYA; NICS‐EH; NORDIL; SHELL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2; TOMHS; VALUE; VART; VHAS) with a total of 153,849 participants. Five of the 23 trials were new in this update (CASE‐J; HOMED‐BP; J‐MIC(B); NAGOYA; VART).

All the included RCTs supplied explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria. Twenty trials included only hypertensive participants, but these were defined differently, as follows: 140/90 mmHg or more (FACET; INVEST; NAGOYA; VART); 150/90 mmHg or more (J‐MIC(B)); more than 160/95 mmHg (VHAS); more than 135/85 mmHg for participants with diabetes mellitus (IDNT); 140 to 179 mmHg systolic and/or 90 to 109 mmHg diastolic (ALLHAT); 150 to 210 mmHg systolic and 95 to 115 mmHg diastolic (ELSA); systolic BP ≥ 180 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 105 mmHg (STOP‐Hypertension‐2); diastolic BP of 100 mmHg or more, NORDIL, or of 90 to 99 mmHg (TOMHS); treated hypertension with an upper limit of 175/100 mmHg or untreated hypertension of 140 to 190 mmHg systolic or 90 to 110 mmHg diastolic (CONVINCE); BP ≥ 160/100 mmHg for participants with untreated hypertension or BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg for participants on antihypertensive treatment (ASCOT‐BPLA); systolic BP ≥ 150 mmHg and diastolic BP ≥ 95 mmHg, or only systolic BP ≥ 160 mmHg (INSIGHT); only diastolic BP ≥ 95 mmHg, AASK, or 90 to 115 mmHg (MIDAS); 160 to 210/220 mmHg systolic and less than 115 mmHg diastolic (NICS‐EH; VALUE); ≥ 160 mmHg systolic and ≤ 95 mmHg diastolic (SHELL); systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg in participants < 70 years old, or systolic BP ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg in participants ≥ 70 years old (CASE‐J); mild‐to‐moderate hypertension (HOMED‐BP). Only one trial did not limit participants to elevated BP (diastolic BP ≥ 80 mmHg) (ABCD), but it reported outcomes on participants with elevated BP (diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg) separately, so data for hypertensive participants could be extracted.

Additional inclusion criteria varied for each study, as follows: with other risk factor(s) for coronary heart disease or cardiovascular disease (ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA; CASE‐J; CONVINCE; INSIGHT); with coronary heart disease (INVEST; J‐MIC(B)); with cardiovascular risk factors or cardiovascular disease (VALUE); with type 2 diabetes mellitus (non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus), ABCD; FACET, or type 2 diabetes mellitus and nephropathy (IDNT); with glucose intolerance (type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance) (NAGOYA); African‐Americans with hypertensive kidney disease (AASK).

All 23 included RCTs recruited participants of both sexes, but age requirements differed amongst the trials, as follows: ≥ 30 years (VART); > 40 years (HOMED‐BP; MIDAS); > 50 years (INVEST; VALUE); > 55 years (ALLHAT; CONVINCE); > 60 years (NICS‐EH; SHELL); 18 to 70 years (AASK); 30 to 70 years (IDNT); 30 to 75 years (NAGOYA); 40 to 65 years (VHAS); 40 to 74 years (ABCD); 40 to 79 years (ASCOT‐BPLA); 45 to 69 years (TOMHS); 45 to 75 years (ELSA); 50 to 74 years (NORDIL); 55 to 80 years (INSIGHT); under 75 years (J‐MIC(B)); 70 to 84 years (STOP‐Hypertension‐2). In the CASE‐J trial, differing BP levels were required for participants aged < 70 years and ≥ 70 years.

Most trials followed a goal BP in their protocols, mostly less than 140/90 mmHg (ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA; CONVINCE; FACET; INSIGHT; INVEST; VALUE; VART); or less than 150/90 mmHg (J‐MIC(B)); less than 130/80 mmHg for hypertensive participants with glucose intolerance (NAGOYA); less than 130/85 mmHg for participants with diabetes or renal impairment (ASCOT‐BPLA; INVEST); ≤ 135/85 mmHg or a decrease ≥ 10 mmHg systolic for diabetic participants (IDNT); ≤ 160/95 mmHg (STOP‐Hypertension‐2); less than 90 mmHg diastolic, NORDIL, or 95 mmHg (TOMHS); less than 95 mmHg with a fall of at least 5 mmHg (ELSA); less than 90 mmHg with a fall of at least 10 mmHg (MIDAS); reduction more than 20 mmHg or systolic BP ≤ 160 mmHg (SHELL); ≤ 90 mmHg or ≤ 95 mmHg with a reduction of at least 10% from baseline value (VHAS); 75 mmHg or less diastolic in the intensive‐treatment group and 80 to 89 mmHg diastolic in the moderate‐treatment group (ABCD); 102 to 107 mmHg of mean arterial pressure in the usual‐goal group and 92 mmHg or less in the lower‐goal group (AASK); a decrease ≥ 20 mmHg of BP if systolic BP was more than 160 mmHg or diastolic BP was more than 110 mmHg (FACET); 60 years old, systolic BP/diastolic BP 130/85 mmHg; 60 to 69 years old, systolic BP/diastolic BP 140/90 mmHg; 70 to 79 years old, systolic BP/diastolic BP 150/90 mmHg; 80 years old, systolic BP/diastolic BP 160/90 mmHg (CASE‐J); usual control 125 to 134/80 to 84 mmHg and tight control < 125/< 80 mmHg (HOMED‐BP).

Of CCBs for hypertension, dihydropyridines (DHPs) were the most commonly studied, especially amlodipine (AASK; ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA; CASE‐J; FACET; IDNT; NAGOYA; TOMHS; VALUE; VART). Other DHPs studied included nifedipine (INSIGHT; J‐MIC(B)), felodipine (STOP‐Hypertension‐2), nisoldipine (ABCD), nicardipine (NICS‐EH), lacidipine (ELSA; SHELL), and isradipine (MIDAS). Other trials evaluated non‐DHPs such as an aralkylamine derivative verapamil, CONVINCE; INVEST; VHAS, and a benzothiazepine derivative diltiazem (NORDIL). One study did not describe the specific CCBs used (HOMED‐BP). The included RCTs compared one of the above CCBs to other classes of antihypertensive drugs, including: a diuretic (ALLHAT; INSIGHT; MIDAS; NICS‐EH; SHELL; TOMHS; VHAS); a beta‐blocker (AASK; ASCOT‐BPLA; ELSA; INVEST; TOMHS); a diuretic or beta‐blocker, or both, data of which could not be separated for each drug (CONVINCE; NORDIL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2); an alpha‐1‐antagonist (TOMHS); an ACE inhibitor (AASK; ABCD; ALLHAT; FACET; HOMED‐BP; J‐MIC(B); STOP‐Hypertension‐2; TOMHS); or an ARB (CASE‐J; HOMED‐BP; IDNT; NAGOYA; VALUE; VART).

Supplemental antihypertensive agents other than the study drugs were permitted in most of the included trials, often administered sequentially to achieve BP goals (AASK; ABCD; ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA; CASE‐J; CONVINCE; ELSA; HOMED‐BP; IDNT; INSIGHT; INVEST; J‐MIC(B); MIDAS; NAGOYA; NORDIL; SHELL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2; VALUE; VART; VHAS). The FACET trial added the study drug of the other group to participants whose BP was not controlled well. The TOMHS trial studied five classes of first‐line antihypertensive drugs, and added chlortalidone or enalapril, both of which were study drugs, to participants to control BP. NICS‐EH prohibited the use of any other antihypertensive drugs.

Outcomes differed amongst studies, but results for our planned outcomes of cardiovascular events and BP changes were reported in most trials. However, fatal MI, stroke, and heart failure were sometimes contained in death events, and in some trials components of cardiovascular events were not reported separately. As a result, not every trial supplied data to each meta‐analysis for outcomes of this review. Only two trials explicitly presented the mean BP changes with standard deviations (SDs), INVEST, or standard errors, TOMHS, which could be directly inputted into Review Manager 5 for analysis. In some other trials, mean BP change could be calculated by subtracting the baseline value at randomisation from the value reported at the end of the trial, but SDs for changes were not reported. We calculated change‐from‐baseline SDs when baseline and final values were known (Higgins 2011b) (AASK; ALLHAT; FACET; NICS‐EH; NORDIL; VALUE). However, when trials did not supply SDs for the baseline and final BPs, the BP results were not entered into the meta‐analysis (ABCD; ASCOT‐BPLA; CASE‐J; CONVINCE; ELSA; HOMED‐BP; IDNT; INSIGHT; J‐MIC(B); MIDAS; NAGOYA; SHELL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2; VART; VHAS).

Mean duration of follow‐up ranged from 2 to 5.3 years. One trial stated that no participant was lost to follow‐up and no participant refused to continue in the study (STOP‐Hypertension‐2), whilst loss to follow‐up and withdrawal were reported in the other 22 trials. All trials with the exception of NICS‐EH stated that an intention‐to‐treat analysis was performed.

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies for details.

The reasons for exclusion included: non‐randomised design (Abascal 1998; Bhad 2011; DHCCP; Pahor 1995; Psaty 1995); the control group used placebo instead of other classes of antihypertensive drugs (Chen 2013; STONE; Syst‐China; Syst‐Eur); the comparison was performed between different kinds of CCBs, without any other classes of antihypertensive drugs (Abe 2013; Kes 2003); the follow‐up was shorter than two years (Espinel 1992; GLANT; Gottdiener 1997; Kereiakes 2012; Leon 1993; Papademetriou 1997; PRESERVE; Schneider 1991; Van Leeuwen 1995; Weir 1990; Zhang 2012); small sample of participants (fewer than 100 were randomised) (Bakris 1996; Bakris 1997; FACTS; Kim 2011; Maharaj 1992; Mesci 2011; Radevski 1999); cannot make a separate comparison of CCB with other classes antihypertensive drugs because of combination drug use (ACCOMPLISH; BEAHIT; Calhoun 2013; Cicero 2012; COLM; DEMAND; FEVER; Kojima 2013; Lauria 2012; OSCAR; Wen 2011); study groups differed in target BPs instead of drug classes (HOT); to avoid repeated inclusion of the research population in extended trial (CASE‐J Ex).

Risk of bias in included studies

Since trials with a small sample were excluded from the current review, most of included trials were large and multicentre with standardised protocols. We evaluated the methodological quality of the included trials in several ways. According to the summary assessment of the risk of bias for each important outcome (Higgins 2011a), we assessed five trials as at low risk of bias (ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA CASE‐J; IDNT; INVEST; J‐MIC(B)), two trials as at high risk of bias (FACET; NICS‐EH), and the remaining 16 trials as at unclear risk of bias. The risk of bias graph (Figure 2) shows judgements of the review authors about each domain presented as percentages across all included studies. The risk of bias summary (Figure 3) shows review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All of the included studies were stated as randomised controlled trials. A computer‐generated code for randomisation was often used, but eight trials did not report the methods of allocation (ABCD; HOMED‐BP; INSIGHT; NICS‐EH; NORDIL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2; VART; VHAS). Allocation concealment was seldom described; only four trials stated that their randomisation codes were concealed at the clinical trials centre (ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA; IDNT; INVEST), whilst in the CONVINCE trial, an interactive voice response system for randomising, assigning, and tracking blinded medication was used. Information was insufficient to assess this 'Risk of bias' domain for the remaining trials.

Blinding

All the included trials compared two first‐line antihypertensive drug classes to each other. With exception of the FACET trial, which was open‐label, the included studies were stated as blinded. In some trials active drugs were described as of indistinguishable appearance, but it was still impossible to know the extent of blinding (Higgins 2011a). Nine trials used a Prospective, Randomised, Open‐label, Blinded Endpoint (PROBE) design (ASCOT‐BPLA; CASE‐J; HOMED‐BP; INVEST; J‐MIC(B); NAGOYA; NORDIL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2; VART), which differs from the classical double‐blind method. In a PROBE study, outcomes are evaluated by a blinded endpoint committee to avoid detection bias; in this way treatment allocation might be open to risk of performance bias from participants and doctors (Hansson 1992).

Incomplete outcome data

Missing data caused by loss to follow‐up or withdrawals were on the whole equal amongst the treatment groups, and an intention‐to‐treat analysis, which meant data were analysed according to randomised treatment assignments regardless of the subsequent medications (Fergusson 2002), was performed in most of the included trials, with the exception of the STOP‐Hypertension‐2 trial (with negligible loss) and the NICS‐EH trial. Some sites and their participants were excluded after randomisation because of poor documentation of informed consent, data integrity concerns, or misconduct (ALLHAT; ASCOT‐BPLA; CONVINCE; INSIGHT), which could have led to attrition bias.

Selective reporting

In this review, we judged all included studies to have a low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

In FACET trial, when BP was not controlled well on monotherapy, the other study drug was added. In NORDIL trial, a diuretic or blocker was added in step 3, and any other antihypertensive compound could be added as step 4 in the diltiazem group. This could have affected the evaluation of effect of each study drug.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4

Summary of findings 1. CCBs versus diuretic for hypertension.

| CCBs versus diuretic for hypertension | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with hypertension Settings: outpatients or inpatients Intervention: CCBs versus diuretic | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | CCBs versus diuretic | |||||

| All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | 35,057 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | NNH 83 (95%CI 53 to 187) | |

| 121 per 1000 | 118 per 1000 (111 to 126) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.92 to 1.08) | 34,072 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | NNT 146 (95%CI 81 to 729) | |

| 74 per 1000 | 74 per 1000 (68 to 79) | |||||

| Stroke Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.94 (0.84 to 1.05) | 34,072 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | NNT 236 (95%CI 120 to 5816) | |

| 40 per 1000 | 37 per 1000 (33 to 42) | |||||

| Congestive heart failure Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | Study population | RR 1.37 (1.25 to 1.51) | 34,072 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | NNH 107 (95% CI 71 to 213) | |

| 45 per 1000 | 62 per 1000 (56 to 68) | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: 2 to 5 years | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.93 to 1.12) | 32,721 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | NNT 242 (95% CI 111 to 1377) | |

| 54 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 (50 to 60) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CCB: calcium channel blocker; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; NNH: number needed to harm; NNT: number needed to treat | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1All studies were blinded, but two of them did not describe the method of blinding. All studies mentioned randomisation, but only three studies provided details; only one study described allocation concealment. 2All studies were blinded, but one of them did not describe the method of blinding. All studies mentioned randomisation, but two of them did not provide details; only one study described allocation concealment. 3All four studies were blinded, but one of them did not describe the method of blinding. All studies mentioned randomisation, but two of them did not provide details; only one study described allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 2. CCBs versus β‐blocker for hypertension.

| CCBs versus β‐blocker for hypertension | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with hypertension Settings: outpatients or inpatients Intervention: CCBs versus β‐blocker | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | CCBs versus β‐blocker | |||||

| All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 2.7 to 5.5 years | Study population | RR 0.94 (0.88 to 1) | 44,825 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | NNT 194 (95%CI 99 to 4004) | |

| 79 per 1000 | 74 per 1000 (70 to 79) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.90 (0.79 to 1.02) | 22,249 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | NNT 223 (95%CI 102 to 1190) | |

| 45 per 1000 | 41 per 1000 (36 to 46) | |||||

| Stroke Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.77 (0.67 to 0.88) | 22,249 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | NNT 104 (95%CI 69 to 210) | |

| 41 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (27 to 36) | |||||

| Congestive heart failure Follow‐up: 4 to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.67 to 1.04) | 19,915 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | NNT 279 (95%CI 141 to 12238) | |

| 18 per 1000 | 15 per 1000 (12 to 19) | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: 2.7 to 5.5 years | Study population | RR 0.90 (0.81 to 0.99) | 44,825 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4 | NNT 279 (95%CI 145 to 3783) | |

| 35 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (29 to 35) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CCB: calcium channel blocker; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; NNT: number needed to treat | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Only two studies described allocation concealment. 2Two studies did not describe allocation concealment. 3Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect and low event rate. 4I2 > 60%. Effect size varied considerably.

Summary of findings 3. CCBs versus ACE inhibitor for hypertension.

| CCBs versus ACE inhibitor for hypertension | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with hypertension Settings: outpatients or inpatients Intervention: CCBs versus ACE inhibitor | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | CCBs versus ACE inhibitor | |||||

| All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.91 to 1.03) | 27,999 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | NNT 282 (95%CI 89 to 240) | |

| 126 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (115 to 130) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 3 to 5.3 years | Study population | RR 1.05 (0.97 to 1.14) | 27,999 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | NNT 235 (95%CI 96 to 541) | |

| 71 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (69 to 81) | |||||

| Stroke Follow‐up: 3 to 5.3 years | Study population | RR 0.90 (0.81 to 0.99) | 27,999 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | NNT 185 (95%CI 95 to 2863) | |

| 52 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (42 to 51) | |||||

| Congestive heart failure Follow‐up: median 3 years | Study population | RR 1.16 (1.06 to 1.28) | 25,276 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4,5 | NNT 94 (95%CI 59 to 222) | |

| 63 per 1000 | 73 per 1000 (66 to 80) | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: 3 to 5 years | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.89 to 1.07) | 27,619 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate6 | NNT 923 (95%CI 148 to 219) | |

| 62 per 1000 | 61 per 1000 (55 to 66) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ACE: angiotensin‐converting enzyme; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; NNT: number needed to treat | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1In one study, study drugs were administered open‐label. All studies mentioned randomisation, but two of them did not provide details; only three studies described allocation concealment. 2In one study, when BP was not well‐controlled on monotherapy, the other study drug was added. 3I2 > 60%; direction and size of effect inconsistent. 4All studies mentioned randomisation, but two of them did not provide details; only two studies described allocation concealment. 5Wide 95% CI crossing the line of no effect and low event rate. 6All studies mentioned randomisation, but two of them did not provide details; only three studies described allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 4. CCBs versus ARB for hypertension.

| CCBs versus ARB for hypertension | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with hypertension Settings: outpatients or inpatients Intervention: CCBs versus ARB | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | CCBs versus ARB | |||||

| All‐cause mortality Follow‐up: 2 to 5.5 years | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.92 to 1.08) | 25,611 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | NNT 3128 (95%CI 143 to 157) | |

| 81 per 1000 | 81 per 1000 (75 to 88) | |||||

| Myocardial infarction Follow‐up: 2 to 5.5 years | Study population | RR 0.82 (0.72 to 0.94) | 25,611 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | NNT 157 (95%CI 93 to 492) | |

| 36 per 1000 | 29 per 1000 (26 to 34) | |||||

| Stroke Follow‐up: 2.6 to 5.5 | Study population | RR 0.89 (0.76 to 1.00) | 25,611 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | NNT 226 (95%CI 115 to 8570) | |

| 34 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (26 to 34) | |||||

| Congestive heart failure Follow‐up: mean 2.6 years | Study population | RR 1.20 (1.06 to 1.36) | 23,265 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | NNT 94 (95%CI 59 to 222) | |

| 38 per 1000 | 45 per 1000 (40 to 51) | |||||

| Cardiovascular mortality Follow‐up: mean 2 years | Study population | RR 0.79 (0.54 to 1.15) | 4642 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | NNT 184 (95% CI 72 to 331) | |

| 25 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (13 to 29) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker; CCB: calcium channel blocker; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; NNT: number needed to treat | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Only two studies described allocation concealment, and one study had withdrawals. 2Only three studies described allocation concealment, and one study had withdrawals. 3I2 > 60%; direction and size of effect inconsistent. 4One study of three did not describe allocation concealment, and one study had withdrawals.

The diuretic and beta‐blocker subgroup included data from three studies in which a diuretic, a beta‐blocker, or both were used but could not be separately analysed.

All‐cause mortality

The effect of CCBs on death from any cause was not significantly different from that of any other evaluated agents: diuretics (5 trials with 35,057 participants: risk ratio (RR) 0.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92 to 1.04, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence); beta‐blockers (4 trials with 44,825 participants: RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.00, P = 0.54, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence); diuretics and beta‐blockers (3 trials with 31,892 participants: RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.12, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence); ACE inhibitors (7 trials with 27,999 participants: RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.03, I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence); and ARBs (6 trials with 25,611 participants: RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.08, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: All‐cause mortality, Outcome 1: CCBs vs other classes of antihypertensive agents

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All‐cause mortality, outcome: 1.1 CCBs versus other classes of antihypertensive agents.

MI (non‐fatal and fatal MI plus sudden or rapid death)

The effect of CCBs on MI was not significantly different from that of diuretics (5 trials with 34,072 participants: RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.08, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence); beta‐blockers (3 trials with 22,249 participants: RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.02, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence); diuretics and beta‐blockers (3 trials with 31,892 participants: RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.19, I2 = 72%; moderate‐certainty evidence); and ACE inhibitors (7 trials with 27,999 participants: RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.14], I2 = 66%; low‐certainty evidence). The incidence of MI was statistically significantly lower (P = 0.004) for CCBs compared to ARBs (6 trials with 25,611 participants: RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.72 to 0.94, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Myocardial infarction, Outcome 1: CCBs vs other classes of antihypertensive agents

We found significant statistical heterogeneity between trials comparing CCBs to diuretics and beta‐blockers (I2 = 72%, P = 0.03) and CCBs to ACE inhibitors (I2 = 66%, P = 0.007). A possible explanation for the heterogeneity may be that the type of CCB studied was different in each trial. The three trials involving diuretics and beta‐blockers respectively studied an aralkylamine derivative (verapamil, CONVINCE), a benzothiazepine derivative (diltiazem, NORDIL), and a DHP (felodipine, STOP‐Hypertension‐2). Another possible explanation is difference in participants. In the CONVINCE trial, participants diagnosed as having hypertension and who had one or more additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease were enrolled, but participants enrolled in the other two trials had no additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Six of seven trials involving ACE inhibitors studied DHPs, but three of them gave participants amlodipine (AASK; ALLHAT; FACET), and two administered felodipine (STOP‐Hypertension‐2), or nisoldipine (ABCD) and one gave nifedipine (J‐MIC(B)). One study did not describe the the specific ACE inhibitors and CCBs that were used (HOMED‐BP). The pooled RR for the trials comparing amlodipine and ACE inhibitors was 1.00 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.10, I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Myocardial infarction, Outcome 2: Amlodipine vs ACE inhibitors

Stroke (non‐fatal and fatal stroke)

The incidence of stroke was not significantly different between CCB and diuretic groups (5 trials with 34,072 participants: RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.05, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence) or between CCB and diuretic and beta‐blocker groups (3 trials with 31,892 participants: RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.03, I2 = 55%; moderate‐certainty evidence). Hypertensive participants treated with CCBs had a significantly lower risk of developing a stroke than those treated with a beta‐blocker (3 trials with 22,249 participants: RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.88, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence) or an ACE inhibitor (7 trials with 27,999 participants: RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.99, I2 = 28%; low‐certainty evidence). There was no difference in risk of stroke between on CCB and ARB groups (6 trials with 25611 participants: RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.00, p = 0.05, I2 = 15%; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 3.1), but the incidence of stroke was lower for amlodipine compared to ARBs (5 trials with 23265 participants:RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.98, I2 = 0%)(Analysis 3.2; Figure 5).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Stroke, Outcome 1: CCBs vs other classes of antihypertensive agents

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3: Stroke, Outcome 2: Amlodipine vs ARBs

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Stroke, outcome: 3.1 CCBs versus other classes of antihypertensive agents.

The reason for significant statistical heterogeneity between trials comparing CCBs to diuretics and beta‐blockers (I2 = 55%, P = 0.11) might be related to the type of CCBs, similar to the description above in the MI results. Explanation for the heterogeneity may be that the type of CCB studied and inclusion criteria of participants were different in each trial. Regarding trials comparing CCBs to ARBs, one trial did not describe the specific CCBs used (HOMED‐BP), whilst five of six trials gave participants amlodipine (CASE‐J; IDNT; NAGOYA; VALUE; VART). The pooled RR for the trials comparing amlodipine to ARBs was 0.85 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.98, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 3.2).

Congestive heart failure

There was no significant difference in development of congestive heart failure between CCB and beta‐blocker groups (2 trials with 19,915 participants: RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.04, I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence) and between CCB and diuretic and beta‐blocker groups (3 trials with 31,892 participants: RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.33, I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). However, the risk of developing congestive heart failure was markedly higher in participants given CCBs than those given diuretics (5 trials with 34,072 participants: RR 1.37, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.51, I2 = 17%; moderate‐certainty evidence); ACE inhibitors (5 trials with 25,276 participants: RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.28, I2 = 0%; low‐certainty evidence); and ARBs (5 trials with 23,265 participants: RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.36, I2 = 66%; low‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 4.1).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4: Congestive heart failure, Outcome 1: CCBs vs other classes of antihypertensive agents

The lack of homogeneity between the five trials comparing a CCB to an ARB may be due to the different inclusion criteria of participants: the IDNT trial included hypertensive individuals with type 2 diabetic nephropathy, and the NAGOYA trial included hypertensive individuals with glucose intolerance, whilst the VALUE, CASE‐J, and VART trials only required participants to have hypertension and cardiovascular risk factors. There was a significant increase in congestive heart failure events among the diabetic nephropathic participants in IDNT (RR 1.58, 95% CI 1.17 to 2.14) and glucose intolerance participants in NAGOYA (RR 5.00, 95% CI 1.46 to 17.18]) treated with a CCB compared to those treated with an ARB.

Cardiovascular mortality

We added death caused by cardiovascular disease as a supplemental outcome, which differed from the published protocol, as we judged it to be important and it was reported in most of the included trials.

We found only a marginally lower cardiovascular mortality in the CCBs group compared to the beta‐blocker group (4 trials with 44,825 participants: RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.99, I2 = 62%; low‐certainty evidence). The effect of CCBs on cardiovascular mortality was not significantly different from that of diuretics (4 trials with 32721 participants: RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.12, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence); diuretics and beta‐blockers (3 trials with 31892 participants: RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.18, I2 = 0%); ACE inhibitors (6 trials with 27619 participants: RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.07, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence) or ARBs (3 trials with 4642 participants: RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.15, I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence) (Analysis 5.1)

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Cardiovascular mortality, Outcome 1: CCBs vs other classes of antihypertensive agents

The heterogeneity amongst trials involving beta‐blockers (I2 = 62%, P = 0.05) might be explained by the different types of CCBs that were evaluated: a non‐DHP in the INVEST trial (verapamil) and a DHP in the other three trials (amlodipine in AASK and ASCOT‐BPLA, and lacidipine in ELSA). After deselecting the INVEST trial, the pooled RR was 0.77 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.90, I2 = 0%), still showing a significant decrease in cardiovascular mortality in the CCB group (Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5: Cardiovascular mortality, Outcome 2: DHP vs β‐blockers

Major cardiovascular events (MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality)

Compared to beta‐blockers, CCBs significantly reduced major cardiovascular events (3 trials with 22,249 participants: RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.92, I2 = 0%). In contrast, when compared to diuretics, CCBs probably increased major cardiovascular events (4 trials with 33,643 participants: RR 1.05, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.09, I2 = 0%, P = 0.03). There was no significant difference in total major cardiovascular events when CCBs were compared to diuretics or beta‐blockers (2 trials with 21,011 participants: RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.10, I2 = 0%); to ACE inhibitors (5 trials with 25,186 participants: RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.02, I2 = 45%); or ARBs (3 trials with 6874 participants: RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.22, I2 = 32%) (Analysis 6.1; Figure 6).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Major cardiovascular events, Outcome 1: CCBs vs other classes of antihypertensive agents

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 6 Major cardiovascular events, outcome: 6.1 CCBs versus other classes of antihypertensive agents.

The poor methodological quality of the FACET trial might be a source of heterogeneity amongst the five trials comparing CCBs with ACE inhibitors. We undertook a sensitivity analysis on this effect by deselecting the FACET trial; the results were unchanged (4 trials with 24,806 participants: RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.02, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6: Major cardiovascular events, Outcome 2: Sensitivity analysis: CCBs vs ACE inhibitors

Systolic and diastolic BP reduction

Using the weighted mean difference method and the fixed‐effect model, we found that the mean systolic BP reduction of the CCB group was 0.81 mmHg (95% CI 0.56 to 1.06) less than that of the diuretic‐based regimen group, and 3.00 mmHg (95% CI 2.59 to 3.41) less than the diuretic‐and‐beta‐blocker‐based regimen group. Systolic BP reduction was ‐1.11 mmHg (95% CI −1.40 to −0.82) more with CCBs than with ACE inhibitors, and ‐2.10 mmHg (95% CI −2.46 to −1.74]) more than with ARBs. There was no significant difference between the CCB group and beta‐blocker group (P = 0.38), or between the CCB group and alpha‐1‐antagonist group (P = 0.27) (Analysis 7.1).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Blood pressure reduction, Outcome 1: Systolic blood pressure reduction

For diastolic BP, the mean reduction of the CCB group was −0.68 mmHg (95% CI −0.84 to −0.52) more than the diuretic group; −0.63 mmHg (95% CI −0.81 to −0.44) more than the ACE inhibitor group; −1.70 mmHg (95% CI −1.91 to −1.49) more than the ARB group; and −1.20 mmHg (95% CI −2.39 to −0.01) more than the alpha‐1‐antagonist group. Mean diastolic changes between the CCB and beta‐blocker groups were not significantly different (Analysis 7.2).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Blood pressure reduction, Outcome 2: Diastolic blood pressure reduction

There was heterogeneity (I2 of 85%) for the four trials comparing the effect of CCBs versus ACE inhibitors on systolic BP reduction, however there was no heterogeneity for the same comparison evaluating diastolic BP reduction. The heterogeneity was most likely due to the poor methodological quality of the FACET trial. Sensitivity analyses conducted without the FACET trial resulted in homogeneous significant mean differences for both systolic and diastolic BP: mean difference −1.00 (95% CI −1.29 to −0.70) and −0.62 (95% CI −0.81 to −0.44), respectively (Analysis 7.3).

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7: Blood pressure reduction, Outcome 3: Sensitivity analysis: CCBs vs ACE inhibitors

Discussion

Summary of main results

After a systematic search and selection process according to the protocol for this review, we included 23 RCTs with 153,849 participants that assessed cardiovascular outcomes or BP change, or both, among hypertensive participants. The two most important outcomes from the perspective of the patient were total all‐cause mortality and major cardiovascular events. The latter outcome is important as it is a composite of the individual outcomes of stroke, MI, and congestive heart failure. There was no significant difference between first‐line CCBs and any of the other classes of antihypertensive drugs for total mortality. In this update, no new trial comparing CCBs with beta‐blockers or diuretics has been incorporated, therefore the outcomes for these comparisons are consistent with the first version of the review. First‐line CCBs reduced major cardiovascular events as compared to beta‐blockers (moderate‐certainty evidence) and increased major cardiovascular events as compared to diuretics (moderate‐certainty evidence). The reduction in major cardiovascular events with CCBs as compared to beta‐blockers is explained by a significant reduction in stroke (moderate‐certainty evidence) and cardiovascular mortality (low‐certainty evidence). The increase in major cardiovascular events for first‐line CCBs as compared to diuretics is explained by increased congestive heart failure events (moderate‐certainty evidence). The risk difference (RD) for heart failure for the comparison of CCBs versus diuretics was 0.02 and is thus clinically important and consistent with either a protective effect of diuretics or a harmful effect of CCBs for this outcome. The finding that first‐line CCBs increased congestive heart failure as compared to ACE inhibitors (low‐certainty evidence) and ARBs (low‐certainty evidence) is robust after more RCTs were included in this update. The other significant differences found were that first‐line CCBs reduced stroke more than ACE inhibitors (low‐certainty evidence) and reduced MI more than ARBs (moderate‐certainty evidence). With the inclusion of new studies comparing CCBs with ARBs, the advantages of CCBs in reducing stroke over ARBs that were found in the first version of the review no longer exist (Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4), but in pooled analysis, the incidence of stroke was lower for amlodipine compared to ARBs.(Analysis 3.2)

Blood pressures decreased in all treatment arms of all the included trials, but mean BP reduction differed. First‐line CCB‐based regimens lowered systolic BP less than first‐line diuretic‐based regimens and conventional treatment‐based regimens. In contrast, first‐line CCBs lowered diastolic BP better than diuretic‐based regimens. First‐line CCB‐based regimens also lowered both systolic and diastolic BPs more than ACE inhibitors and ARBs. This could partially explain the differences in stroke outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most of the included trials with the exception of TOMHS reported relevant hypertension outcomes, but not all of the desired outcomes were available from each trial. Furthermore, supplemental inclusion criteria were required in several trials, and most trials were event‐driven hypertension studies, which meant that the included participants tended to have more complicated hypertension or advanced disease (Zanchetti 2005). Patients at the two extremes, that is those with uncomplicated hypertension at one extreme and those with severe or acute hypertension and secondary hypertension at the other extreme, were not included in the current analysis.

Although we included 23 studies with a large number of participants comparing several classes of antihypertensive drugs in this update, the number of trials for each of the subgroups was limited. Because of this data were insufficient for some comparisons. This was particularly the case for alpha‐1‐antagonists. Furthermore, most of the included CCBs were dihydropyridines, with evidence for non‐DHPs inadequate.

The prevalence of hypertension amongst adults with diabetes mellitus is approximately 80% (Kannel 1991). Although all major antihypertensive drug classes (i.e. ACE inhibitors, ARBs, CCBs, and diuretics) are useful in the treatment of hypertension in diabetes mellitus (Whelton 2018), guidelines recommended CCBs as a first‐line choice for those with hypertension and diabetes (JNC‐8; Whelton 2018; Williams 2018). Opie and colleagues made the point that the incidence of developing diabetes was less on the amlodipine‐based regimen (Opie 2002). On the other hand, the NAGOYA study found that hypertensive participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance in the valsartan group had a significantly lower incidence of heart failure than those in the amlodipine group. A meta‐analysis of RCTs of primary prevention of albuminuria in participants with diabetes mellitus demonstrated a significant reduction in progression of moderately to severely increased albuminuria with the use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs (Palmer 2015), with CCB showing no effect. As we were unable to extract data to separately evaluate the effects on hypertensive participants with diabetes in our review, it is not possible to say whether CCBs have different effects in diabetic hypertensive patients.

Quality of the evidence

We graded the overall quality of the evidence and developed 'Summary of findings' tables, using GRADEpro GDTsoftware.

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that all‐cause mortality was not different between first‐line CCBs and any other antihypertensive classes.

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that first‐line CCBs increased congestive heart failure more than diuretics, and low‐certainty evidence that they increased congestive heart failure more than ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that first‐line CCBs reduced stroke, and low‐certainty evidence that they reduced cardiovascular mortality more than beta‐blockers.

We found low‐certainty evidence that first‐line CCBs reduced stroke more than ACE inhibitors, and moderate‐certainty evidence that they reduced myocardial infarction more than ARBs.

Potential biases in the review process

The included trials varied in their designs and methods, baseline and goal BPs, study populations, and drugs, so combining their data to arrive at a conclusion may have some limitations. For example, CCBs are a heterogeneous group of drugs that are subclassified into DHPs and non‐DHPs. The different classes have different in binding sites on the calcium channel pores and thus could have different effects (Opie 2000; Triggle 2007). In the current review, we did not evaluate different types of CCBs in separate comparisons, but it might not be appropriate to combine them in a meta‐analysis. The high I2 values for pooled trials involving both DHPs and non‐DHPs (72% for three trials assessing MI events) are consistent with this possibility (CONVINCE; NORDIL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2). However, in this case dividing the trials into DHPs and non‐DHPs does not explain the heterogeneity. Likewise, heterogenous populations in the included trials might be the cause of the heterogeneity of the effect. In the current review, enrolled participants included those with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, or other conditions. It was not possible to investigate the effect of these subgroup populations on the effect size. In general, there was excellent homogeneity of most effects as shown by an I2 value of 0%, with only a few outcomes associated with I2 > 50%, leading us to believe that the overall conclusions of our review are valid.

Although the benefits of BP lowering for the prevention of cardiovascular disease are well established (BPLTTC 2000; BPLTTC 2003; Ezzati 2002; Thomopoulos 2015; Wright 2018; Xie 2016), which antihypertensive drug class should be prescribed first is still somewhat controversial. In order to achieve the BP goal many patients need to be prescribed more than one antihypertensive agent (Chobanian 2003; Haller 2008; Mancia 2007). This fact leads to another limitation in the review and is perhaps its major weakness. Since additional antihypertensive agents other than first‐line drugs were administered sequentially to reach BP goals in most of the included trials, the results may have been confounded, although they were presumed to reflect the effect of the first drug. Only one small trial included in our review prohibited the use of any other antihypertensive drugs (NICS‐EH), and it concluded that the CCB and diuretic groups had a similar decrease in BPs and cardiovascular events. BP differences between different classes of drugs could have an impact on outcomes (Staessen 2003; Wright 2018), which is a further limitation of this type of review. In addition, three included trials had a 2 X 3 design (AASK; ABCD; HOMED‐BP). Participants were randomised 1) BP tight target versus usual 2) different drug classes. As reported, the effect of different drugs is difficult to differentiate from that of BP targets.

We have tried to reduce the risk of attrition bias by reporting on the intent‐to‐treat population to the greatest degree possible. We do not think publication bias is likely as we have done an extensive search of the pertinent literature, including published and unpublished studies, without any language restrictions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This review was not designed to assess the effect of CCBs versus placebo or no treatment, but other meta‐analyses have addressed this question and demonstrated that first‐line CCBs reduce stroke and total cardiovascular events. A recent meta‐analysis of 10 RCTs (30, 359 participants) comparing CCBs blood pressure‐lowering treatment with no or less intense treatment showed that significant reductions in stroke, major cardiovascular events, cardiovascular and all‐cause death were obtained with CCBs (Thomopoulos 2015). Another meta‐analysis of 147 RCTs including 464,000 participants with hypertension demonstrated that all major antihypertensive drug classes (diuretics, ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta‐blockers, and CCBs) caused a similar reduction in coronary heart disease events and stroke for a given reduction in BP (Law 2009). Blood pressure lowering by all classes of antihypertensive drugs is accompanied by significant reductions in stroke and major cardiovascular events, supporting the concept that reduction of these events is due to BP lowering.

In this review, we found that CCBs increased total cardiovascular events as compared to diuretics; within total cardiovascular events, only congestive heart failure events increased with CCB. The results of recent meta‐analyses are consistent with this conclusion: thiazides were associated with a lower risk of heart failure compared with CCBs, whilst there was no difference between groups in other events (Reboussin 2017; Thomopoulos 2015). The increase in total cardiovascular events for first‐line CCBs as compared to diuretics is explained by increased congestive heart failure events with CCBs.

CCBs significantly increased the risk of congestive heart failure as compared to diuretics, ACE inhibitors, and ARBs. This finding is consistent with other reviews (Black 2004; Opie 2000; Thomopoulos 2015). The Systematic Review for the 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults indicated that thiazides were associated with a lower risk of many cardiovascular outcomes compared with other antihypertensive drug classes (Reboussin 2017). Since CCBs and other drug classes did not have any other advantages as compared to diuretics, this would suggest that diuretics are the preferred first‐line drugs for patients with hypertension.

The results of this review are consistent with the findings of another Cochrane Review evaluating the comparison of beta‐blockers versus first‐line CCBs (Wiysonge 2007). That review concluded that beta‐blockers reduced total cardiovascular events significantly less than CCBs. A similar meta‐analysis including six of the trials included in our review, INSIGHT; MIDAS; NICS‐EH; NORDIL; STOP‐Hypertension‐2; VHAS, concluded that mortality and major cardiovascular events with CCBs were similar to those seen with conventional therapy (diuretics or beta‐blockers) (Opie 2002). A recent meta‐analysis showed that the risk of stroke was significantly higher (25%) with beta‐blockers as compared with CCBs (Thomopoulos 2015). To this point there is no evidence to support the initial use of beta‐blockers for hypertension in the absence of specific cardiovascular comorbidities.

Other authors have claimed that CCBs are more effective than other treatments in decreasing the risk of stroke in hypertensive individuals (Angeli 2004; Verdecchia 2005). However, a previous meta‐analysis found no difference between ARBs and CCBs in risk of stroke in diabetic participants (Turnbull 2005). Our results showed that stroke events are significantly reduced by CCBs as compared to beta‐blockers and ACE inhibitors. In the previous version of this review we found that CCBs reduced the risk of stroke as compared to ARBs (2 trials with 16,391 participants). In this updated version we added 4 new trials for comparison (CASE‐J; HOMED‐BP; NAGOYA; VART),the results indicated no difference between ARBs and CCBs(total 6 trials with 25611 participants). But in a pooled analysis of 5 trials comparing amlodipine of CCBs and ARBs, the incidence of stroke was lower for amlodipine compared to ARBs.This may be due to the greater blood pressure‐lowering effect of CCBs as compared to ACE inhibitors as was found in this review, but it does not explain the difference for beta‐blockers, which did not have a different blood pressure‐lowering effect. It has been hypothesised that CCBs might have anti‐atherosclerotic actions that could be helpful in reducing stroke as well (Angeli 2004).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This update changed some conclusions of the previous version of this review. First‐line calcium channel blockers (CCBs) do not affect total mortality as compared to other antihypertensive drug classes. First‐line CCBs reduce major cardiovascular events, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality as compared to beta‐blockers. First‐line CCBs increase major cardiovascular and congestive heart failure events as compared to diuretics. First‐line CCBs reduce stroke as compared to angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and myocardial infarction as compared to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), but they increase congestive heart failure events as compared to both ACE inhibitors and ARBs.

The review shows an advantage of diuretics over CCBs in reducing major cardiovascular mortality and congestive heart failure events. We found evidence supporting CCBs over beta‐blockers in reduce major cardiovascular events, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality. It should be noted that many of the differences found in the current review are not robust, and further trials might change the conclusions. It will therefore be important to follow the research in this field closely and update this review when new data become available.

Implications for research.

More well‐designed randomised controlled trials comparing CCBs with other types of antihypertensive drugs and combinations of CCBs with other antihypertensive drug classes are needed, especially for individuals with comorbidities such as diabetes, coronary heart disease, and nephropathy. These trials must avoid confounding factors to the greatest degree possible, such as by ensuring that the secondary drugs added to each arm of the trial are the same. It is important that all relevant outcomes are well defined and reported.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 January 2022 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | We created 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADEpro software and assessed the overall quality of evidence for each outcome based on GRADE criteria. Some main conclusions were changed. |

| 7 January 2022 | New search has been performed | We updated the literature searches and included five new studies in this updated review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2002 Review first published: Issue 8, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 September 2020 | New search has been performed | The authors finished the first draft of the full review. |

| 1 May 2009 | New citation required and major changes | Protocol re‐published with new authors and amended methods. |

| 23 August 2006 | New citation required and major changes | Protocol withdrawn by authors. |

Notes

This protocol was first published in the Cochrane Library in Issue 2, 2002, by Onder G, Furberg CD, Moore A, Psaty BM, Pahor M. It was subsequently withdrawn by the original authors in June 2006 because they were not able to continue working on it.

This review was updated in 2021.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the original authors of this Cochrane Review protocol (Onder G, Furberg CD, Moore A, Psaty BM, Pahor M), who identified the topic and contributed extensively to the background.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies