Abstract

Rapid and efficient epidemiologic typing systems would be useful to monitor transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) at both local and interregional levels. To evaluate the intralaboratory performance and interlaboratory reproducibility of three recently developed repeat-element PCR (rep-PCR) methods for the typing of MRSA, 50 MRSA strains characterized by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (SmaI) analysis and epidemiological data were blindly typed by inter-IS256, 16S-23S ribosomal DNA (rDNA), and MP3 PCR in 12 laboratories in eight countries using standard reagents and protocols. Performance of typing was defined by reproducibility (R), discriminatory power (D), and agreement with PFGE analysis. Interlaboratory reproducibility of pattern and type classification was assessed visually and using gel analysis software. Each typing method showed a different performance level in each center. In the center performing best with each method, inter-IS256 PCR typing achieved R = 100% and D = 100%; 16S-23S rDNA PCR, R = 100% and D = 82%; and MP3 PCR, R = 80% and D = 83%. Concordance between rep-PCR type and PFGE type ranged by center: 70 to 90% for inter-IS256 PCR, 44 to 57% for 16S-23S rDNA PCR, and 53 to 54% for MP3 PCR analysis. In conclusion, the performance of inter-IS256 PCR typing was similar to that of PFGE analysis in some but not all centers, whereas other rep-PCR protocols showed lower discrimination and intralaboratory reproducibility. None of these assays, however, was sufficiently reproducible for interlaboratory exchange of data.

Nosocomial infections caused by methicillin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have become an important clinical problem worldwide. Monitoring and limiting the intra- and interhospital spread of MRSA strains require the use of efficient and accurate epidemiologic typing systems. A large number of DNA-based methods have been developed for typing MRSA strains. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis is an accurate, reliable, and discriminatory method used by many hospital and reference laboratories (1), but it is technically demanding and time-consuming. Compared to PFGE analysis, PCR-based typing methods offer the advantages of rapidity and simplicity. However, when evaluated according to recommended criteria (18, 20), several PCR-based methods used for typing MRSA strains have shown limitations, either in intercenter pattern reproducibility, as described for arbitrarily primed PCR (AP-PCR) analysis (22), or in discrimination, as found with PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the coagulase or protein A gene (7). Compared to the latter assays, repetitive-element PCR (rep-PCR) analysis based on multicopy elements of the staphylococcal genome has shown good reproducibility and discriminatory power in single-center studies (4–6, 15, 25). There is therefore a need to identify the most efficient of these recently developed PCR-based typing methods.

Ideally, laboratories conducting regional surveillance of MRSA infections should adopt a common genotyping system to compare typing results. This requires using a system with good interlaboratory reproducibility, implying standardization of protocols, reagents, PCR equipment, and DNA pattern analysis. Fragment pattern analysis using automated laser fluorescence analysis (ALFA) systems is promising, as it provides enhanced resolution and better normalization of patterns than agarose gel electrophoresis (3, 10, 11).

The aims of the present study were to (i) compare the performance of three rep-PCR typing methods targeting repetitive elements IS256 (6), 16S-23S rRNA (15), and rep-MP3 (5, 25), (ii) assess the reproducibility of these PCR assays when performed by different laboratories using a standard protocol and the same batch of reagents, and (iii) evaluate the advantages of PCR pattern analysis using an automated laser sequencer over analysis by agarose electrophoresis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A collection of 50 MRSA isolates (Table 1), already characterized by PFGE analysis (SmaI), were selected from previously described collections (8, 19, 21, 23, 24; R. De Ryck, A. Deplano, C. Nonhoff, B. Jans, C. Suetens, and M. J. Struelens, Prog. Abstr. 9th Eur. Cong. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis., 1999, abstr. P123, p. 117). These strains were subdivided into four groups: a group of isolates from a single hospital epidemic showing indistinguishable PFGE profiles (strains 1 to 5); two groups of epidemiologically related isolates (strains 6 to 11 and 12 to 15) displaying closely related PFGE patterns which differed by ≤3 DNA fragments (18, 20); and 30 epidemiologically unrelated isolates (strains 16 to 45) displaying PFGE patterns which differed by ≥7 DNA fragments, including the reference S. aureus strain NCTC 8325. This collection included five duplicate isolates (strains 46 to 50) used as a reproducibility panel.

TABLE 1.

Origin and results of PFGE typing of the MRSA strain collection

| Strain code | Origin (country, yr) | Reference | Source | PFGE typea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Germany, 1994 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital A | 1 |

| 2 | Germany, 1994 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital A | 1 |

| 3 | Germany, 1994 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital A | 1 |

| 4 | Germany, 1994 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital A | 1 |

| 5 | Germany, 1994 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital A | 1 |

| 6 | Belgium, 1995 | Ab | Epidemic, hospital B | 2a |

| 7 | Belgium, 1995 | A | Epidemic, hospital C | 2b |

| 8 | Belgium, 1995 | A | Epidemic, hospital D | 2c |

| 9 | Belgium, 1995 | A | Epidemic, hospital E | 2d |

| 10 | Belgium, 1995 | A | Epidemic, hospital E | 2e |

| 11 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital F | 2f |

| 12 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital G | 3a |

| 13 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital G | 3b |

| 14 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital H | 3c |

| 15 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital G | 3d |

| 16 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital I | 4 |

| 17 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Sporadic, hospital J | 5 |

| 18 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital K | 6 |

| 19 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital L | 7 |

| 20 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Sporadic, hospital M | 8 |

| 21 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Sporadic, hospital F | 9 |

| 22 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Sporadic, hospital N | 10 |

| 23 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Sporadic, hospital O | 11 |

| 24 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Sporadic, hospital N | 12 |

| 25 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Sporadic, hospital O | 13 |

| 26 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital P | 14 |

| 27 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Sporadic, hospital Q | 15 |

| 28 | Germany, 1991 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital R | 16 |

| 29 | Poland, 1992 | 21 | Epidemic, hospital S | 17 |

| 30 | Saudi-Arabia, | 23 | Epidemic, hospital T | 18 |

| 31 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Sporadic, hospital U | 19 |

| 32 | Germany, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital A | 20 |

| 33 | Germany, 1996 | 18 | Sporadic, hospital V | 21 |

| 34 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Sporadic, hospital W | 22 |

| 35 | Poland, 1992 | 21 | Epidemic, hospital X | 23 |

| 36 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Sporadic, hospital Y | 24 |

| 37 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Sporadic, hospital Z | 25 |

| 38 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital ZA | 26 |

| 39 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Sporadic, hospital ZB | 27 |

| 40 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital ZC | 28 |

| 41 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital ZD | 29 |

| 42 | Belgium, 1992 | 8 | Epidemic, hospital ZE | 30 |

| 43 | United States | 19 | Sporadic | 31 |

| 44 | Germany, 1996 | 24 | Epidemic, hospital ZF | 32 |

| 45 | NCTC 8325/0 | 24 | Reference strain | 33 |

| 46 | Duplicate of strain 4 | 1 | ||

| 47 | Duplicate of strain 19 | 7 | ||

| 48 | Duplicate of strain 38 | 26 | ||

| 49 | Duplicate of strain 6 | 2a | ||

| 50 | Duplicate of strain 43 | 31 |

PFGE types are designated by numerals and include patterns differing by ≥7 DNA fragments; PFGE subtypes are designated by letter suffixes and include patterns differing by ≤6 DNA fragments.

A, De Ryck et al., Prog. Abstr. 9th Eur. Cong. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1999, abstr. P123.

PFGE analysis.

SmaI macrorestriction analysis resolved by PFGE was performed by the coordinating center as previously described (8). Major PFGE types were designated by arabic numerals, and subtypes were designated by letter suffixes (Table 1).

Study design.

This multicenter study was organized by the European Study Group on Epidemiological Markers. Twelve centers representing eight countries participated in the study. The study was coordinated at the National Reference Laboratory for Staphylococci, University of Brussels-Hôpital Erasme, Brussels. The MRSA strains were distributed by the coordinating center to the participating centers labeled with code numbers. Each center tested the coded isolates without knowledge of isolate origin or PFGE type using one or more rep-PCR typing methods. Each rep-PCR typing method was performed according to a standard protocol for DNA extraction, amplification, and electrophoresis and using the same batch of PCR primers with the local equipment and minor modifications of protocols (Table 2). For data analysis, each investigator first classified the coded isolates visually into PCR types based on previously defined criteria of pattern interpretation. Tables of type distribution and gel images were then reported to the coordinating center, where the codes were broken and centralized analysis was performed.

TABLE 2.

PCR assays and experimental parameters used by participating centers

| Rep-PCR target | Center | Cycler | Product analysis | Gel type (concn)a | Size ladder (brand)b | Image format | DNA fragment pattern

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of fragments | Size range (bp) | |||||||

| IS256 | 1 | Biomed 60 | Agarose | A (1.5%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | TIFF | 2–8 | 200–2,000 |

| 1 | Biomed 60 | ALF | F (5%) | TIFF | 9–16 | 100–1,500 | ||

| 3 | Hybaid | Agarose | A (1.5%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | TIFF + photo | 2–10 | 200–2,000 | |

| 5 | Perkin-Elmer 480 | ALF | F (5%) | TIFF | 9–16 | 100–1,500 | ||

| 6 | Perkin-Elmer 480 | Agarose | A (1.5%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | Photo | 2–8 | 150–2,000 | |

| 8 | Ericomp twinBlock system | Agarose | A (1.5%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | TIFF | 2–8 | 200–1,500 | |

| 10 | Techne Cyclogene | Agarose | B (1.5%) | 100 bp (Bo.) | TIFF | 2–6 | 150–2,600 | |

| 11 | Perkin-Elmer 9600 | Agarose | A (1.5%) | 100 bp (BRL) | TIFF | 2–8 | 150–1,500 | |

| rRNA | 3 | Hybaid | Agarose | C (3%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | TIFF + photo | 1–8 | 420–820 |

| 4 | Techne pHC3 | Agarose | C (3%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | Photo | 4–12 | 400–700 | |

| 5 | Perkin-Elmer | ALF | F (5%) | TIFF | 4–9 | 100–750 | ||

| 7 | Biomed 60 | Agarose | C (3%) | 100 bp (BRL) | TIFF | 3–8 | 350–600 | |

| 11 | Perkin-Elmer 9600 | Agarose | D (2.5%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | TIFF | 5–11 | 400–700 | |

| 12 | Techne-Genius | Agarose | C (3%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | Photo | 5–10 | 400–800 | |

| repMP3 | 1 | Biomed 60 | Agarose | A (1.5%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | TIFF | 2–9 | 400–1,500 |

| 1 | Biomed 60 | ALF | F (5%) | 100 bp (H.) | TIFF | 6–15 | 100–1,100 | |

| 2 | Perkin-Elmer 480 | Agarose | E (1.5%) | 100 bp (Ph.) | TIFF | 1–7 | 400–2,400 | |

| 9c | Perkin-Elmer 9600 | Agarose | A (1.5%) | 1 kb (Ph.) | Photo | 6–13 | 100–4,000 | |

A, ultrapure agarose (Gibco-BRL); B, standard agarose (Eurobio); C, Nusieve (Biozym); D, Metaphor (FMC BioProduct); E, agarose NA (Amersham-Pharmacia-Biotech); F, Long Ranger (FMC Bioproduct).

Ph., Amersham-Pharmacia-Biotech; Bo, Boehringer Mannheim; BRL, Gibco-BRL.

This center also used another batch of primer.

Inter-IS256 PCR typing.

Inter-IS256 typing was performed on a bacterial lysate obtained in a three-step procedure with lysostaphin, proteinase K, and boiling, as described previously (6). Amplification was performed using Ready-To-Go RAPD beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Roosendaal, The Netherlands). The bacterial lysate was diluted 1:10, and 2 μl (40 to 80 ng) of this solution were used as the DNA template in the Ready-To-Go tube for the PCR as previously described (6).

Inter-16S-23S rRNA PCR typing.

Typing of 16S-23S rRNA was performed on a bacterial lysate obtained in a three-step procedure with lysostaphin, proteinase K, and boiling, as described previously (15).

Rep-MP3 PCR typing.

Rep-MP3 typing was performed on phenol-chloroform-purified DNA as described recently, and 200 ng of DNA was added to 25 μl of PCR mix as previously described (25).

Agarose analysis of PCR products.

Electrophoresis of IS256 and Rep-MP3 PCR products was performed on a 1.5% ultrapure agarose gel (Life Technology, Merelbeke, Belgium), and 16S-23S rRNA PCR products were electrophoresed on 3% NuSieve gel (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) in 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer containing 0.5 μg of ethidium bromide per ml. A 100-bp DNA ladder (size range, 100 to 2,600 bp; catalog number 27-4001-01; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Roosendaal, The Netherlands) was included in every sixth lane as molecular size markers.

ALFA of PCR products.

DNA extraction and PCR protocols were as above except that CY-5′ fluorescently labeled primers were used and PCR products were resolved in the ALF-Express automated DNA sequencer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Electrophoresis was performed in 5% Long Ranger gel containing 7 M urea (catalog number 50660; FMC Bioproducts) in 0.6× TBE buffer. One microliter of amplicon was mixed with 5 μl of gel loading buffer containing two internal CY-5′-labeled DNA size markers, 0.4 μl of a 100-bp fragment (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and 0.4 μl of a 1,064-bp fragment of the Escherichia coli small-subunit ribosomal DNA (rDNA) (kindly provided by H. Grundmann). The external size marker was a CY-5′-labeled 100-bp ladder (size range, 100 to 1,500 bp) (kindly provided by H. Grundmann). Electrophoresis conditions were 1,600 V, 38 mA, and 45 W at 45°C for 490 min.

Local analysis of agarose-generated PCR patterns.

PCR patterns resolved by agarose electrophoresis were visually interpreted by each investigator. Determination of DNA banding pattern differences and classification of coded isolates into PCR types was done without knowledge of strain origin or PFGE typing results. Classification was performed twice, following two distinct interpretation rules: (i) patterns differing by one or more band were categorized into distinct types and (ii) patterns differing by two or more bands were categorized into distinct types, whereas patterns differing by a single band were considered as belonging to the same type (6).

Centralized visual analysis of data.

Gel photographs and/or TIFF files of gel images were sent to the coordinating center together with a table showing the results of visual classification of the coded strains. Classification of patterns performed at the participating centers was checked at the coordinating center. The performance characteristics of each PCR method were evaluated after breaking the isolate codes by calculation of three performance indices (18) for each participating center. First, intracenter reproducibility (R) was defined as the proportion of duplicate strains assigned to the same PCR type (18). Second, discriminatory power was estimated by calculation of the discrimination index (D) (13) based on PCR type distribution among the 33 unrelated strains with distinct PFGE types. Third, the agreement of PCR type distribution of all MRSA isolates with PFGE type classification was assessed.

Centralized computer-assisted analysis of data.

ALF files and photographs of agarose gels were converted into TIFF files using Image Master software (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and the ScanJet IIP system (Hewlet Packard, Brussels, Belgium), respectively. All TIFF files were imported as fingerprint type into a BioNumerics software database (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). For each set of gel patterns produced by a participating laboratory, data were stored as a separate file of fingerprint experiment type, each containing 50 fingerprints. The database included a total of 19 fingerprint types combining different centers, PCR methods, and post-PCR analytic methods.

Gel image files were processed by definition of fingerprint lanes, optimization of densitometric curves, and normalization of the patterns. The Fourier analysis function of the BioNumerics software was used for determination of settings for background substraction with the rolling disk method. The signal-noise ratio indicating the quality of the gel was noted. Noise filtering was applied using the Wienner cut-off scale to determine optimal settings using the least-square noise-filtering method. The 100-bp ladder external size markers loaded in every sixth lane were used as a reference for gel normalization. One reference pattern was selected as the standard and used to align the corresponding bands of all reference patterns, and fingerprints were normalized by interpolation.

Computer-assisted analysis of PFGE patterns.

TIFF files of SmaI PFGE patterns were imported into the BioNumerics database as fingerprint types and analyzed using the dice coefficient and the unweighted pair group method using the arithmetic averages clustering method. PFGE patterns with a dice coefficient of ≥80% (corresponding to ≤6 DNA fragment differences between patterns) were assigned to the same type (20).

RESULTS

Performance of rep-PCR typing methods resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis.

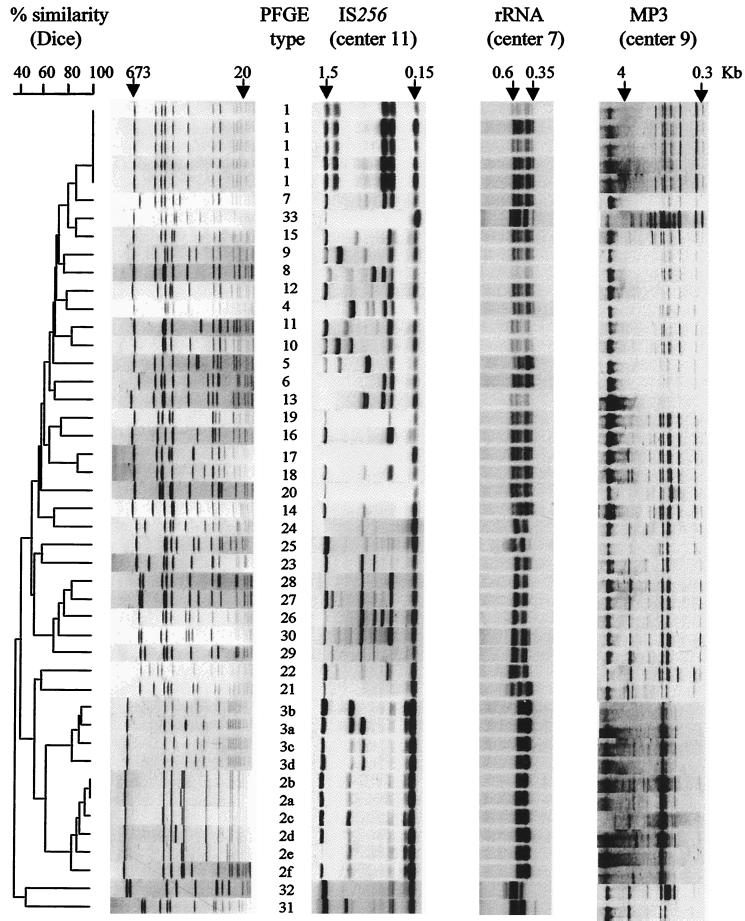

Figure 1 shows rep-PCR patterns obtained at the best agarose center, defined as having obtained a PCR type classification closest to the PFGE classification. The performance characteristics of each rep-PCR method, based on visual type classification, varied widely among participating centers (Table 3). Using the one-band difference interpretation rule, inter-IS256 PCR and rRNA PCR typing achieved a reproducibility of 100% in two and three centers, respectively. Inter-IS256 PCR typing showed a D index ranging between 97 and 100%, whereas that of 16S-23S rRNA PCR ranged between 72 and 82%. The lower discrimination of the latter method seemed to be related to production of a limited diversity of DNA fragments which clustered in a narrow size range (Fig. 1). Rep-MP3 PCR typing showed low reproducibility and intermediate-level discrimination, compared with the two other methods. Using the interpretation criterion of a two-band difference, there was limited improvement in reproducibility but at the cost of a significant decrease in discrimination (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Patterns, clustering, and type classification of the 45 MRSA strains by PFGE analysis and inter-IS256, 16S-23S rRNA, and MP3 PCR patterns resolved by agarose electrophoresis in the center obtaining the best performance with each method.

TABLE 3.

Discrimination (D), intralaboratory reproducibility (R), and agreement with PFGE analysis of rep-PCR typing methods by center, based on visual interpretation of patterns that differed by one or two bands

| Rep-PCR target | Center |

D (%)

|

R (%)

|

Agreement with PFGEb (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 band | 2 bands | 1 band | 2 bands | 1 band | 2 bands | ||

| IS256 | 1 | 99 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 78 | 62 |

| 3 | 99 | 97 | 20 | 40 | 66 | 64 | |

| 6 | 99 | 94 | 60 | 80 | 80 | 54 | |

| 8 | 97 | 77 | 80 | 100 | 78 | 58 | |

| 10 | 99 | 98 | 75c | 75 | 77 | 67 | |

| 11 | 100 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 73 | |

| 16S-23S rRNA | 3 | 79 | 69 | 20 | 20 | 36 | 36 |

| 4 | 72 | 53 | 75c | 75 | 39 | 35 | |

| 7 | 82 | 63 | 100 | 100 | 48 | 36 | |

| 11 | 78 | 76 | 100 | 100 | 49 | 43 | |

| 12 | 78 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 44 | 37 | |

| Rep-MP3 | 1 | 85 | 78 | 50c | 50 | 47 | 43 |

| 2 | 95 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 50 | |

| 9 | 83 | 78 | 80 | 80 | 50 | 42 | |

Calculation based on 33 unrelated strains with distinct PFGE types.

Concordance between classification in rep-PCR types and PFGE types.

Evaluated on four duplicates.

Agreement of rep-PCR types, based on a single- or two-band difference, with PFGE types was better for inter-IS256 PCR than for all rep-PCR techniques (Table 3). By using the one-band rule, center 11 achieved a typing performance with inter-IS256 typing equivalent to that of PFGE typing (Table 3).

Epidemiologically related MRSA strains with indistinguishable PFGE patterns (PFGE type 1) were uniformly classified into a common rep-PCR type (Fig. 1). However, strains belonging to PFGE types 2 and 3 (which differed from each other by ≥7 SmaI DNA fragments) were also grouped together into an identical type by 16S-23S rRNA and rep-MP3 PCR methods (Fig. 1). In contrast, inter-IS256 PCR showed in all centers an additional “extra” DNA band in the majority of PFGE type 3 strains compared with PFGE type 2 strains (Fig. 1). Unrelated strains did not show consistent clustering by rep-PCR typing.

Intralaboratory pattern reproducibility of duplicate strains was very variable between strains, as measured by computer analysis using the Pearson similarity coefficient, which ranged by center between 43 and 98% with inter-IS256 PCR, 40 and 99% for 16S-23S rRNA PCR, and 50 and 98% for rep-MP3 PCR (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Intralaboratory reproducibility as measured by the Pearson similarity coefficient of DNA patterns of duplicate strains by rep-PCR target, method of post-PCR analysis, and centera

| Duplicate strain no. | Similarity coefficient (%) for target, method, and center no.:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS256

|

16S-23S rRNA

|

MPS

|

||||||||||||||||

| Agarose

|

ALFA

|

Agarose

|

ALFA

|

Agarose

|

ALFA

|

|||||||||||||

| 1 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 1 | |

| 4 | 88 | NA | 75 | 53 | 91 | 89 | 75 | 94 | 87 | 89 | 72 | 67 | 95 | 72 | 65 | 71 | 74 | 88 |

| 6 | 43 | NA | 98 | 81 | ND | 97 | 88 | 88 | 99 | 97 | 97 | 78 | ND | 90 | 98 | 90 | 75 | 95 |

| 19 | 94 | NA | 46 | 97 | 98 | 90 | 87 | 85 | 75 | 82 | 76 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 76 | 62 | 68 | 82 |

| 38 | 95 | NA | 96 | 87 | 97 | 97 | 75 | NA | 91 | ND | 90 | ND | 80 | 92 | 50 | 87 | 79 | 58 |

| 43 | 98 | NA | 96 | 96 | 98 | 95 | 95 | 93 | 96 | 40 | 90 | 78 | ND | 95 | NA | NA | 89 | 91 |

| Mean of 5 pairs | 84 | NA | 82 | 83 | 96 | 94 | 84 | 90 | 90 | 77 | 85 | 73 | 85 | 88 | 72 | 77 | 77 | 83 |

NA, not acceptable for interpretation due to low picture quality or markedly lower DNA concentration in one duplicate lane; ND, not done.

ALFA.

ALFA of rep-PCR products revealed additional amplified DNA fragments in the range of 100 to 200 bp compared with the patterns obtained by agarose electrophoresis (Table 2). The level of intralaboratory reproducibility on duplicate strains analyzed with ALF was similar to that obtained in the best agarose center with each PCR typing method (Table 4). The reproducibility between these post-PCR analysis methods could not be formally compared because ALFA was performed by fewer centers than agarose analysis.

The mean Pearson similarity values of duplicate strain patterns (Table 4) were used as a cut-off value, below which isolates were assigned to distinct rep-PCR types in Fig. 2. MRSA strains included in this dendrogram were those classified into distinct PFGE types and excluded the duplicate strains. The number of types thus obtained was 28, 13, and 14 by inter-IS256, 16S-23S rRNA, and rep-MP3 PCR typing, respectively (Fig. 2). The discriminatory power of all rep-PCR methods was similar whether analyzed by ALF or agarose electrophoresis, displaying D values of 99, 91, and 87% for inter-IS256, 16S-23S rRNA, and rep-MP3 PCR, respectively (data not shown). The 16S-23S rRNA PCR typing showed better discrimination when resolved by ALFA, probably due to the better resolution of the compacted DNA fragments observed in agarose analysis (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Agreement with PFGE analysis was 77% for inter-IS256 PCR typing and only 49 and 51% for 16S-23S rRNA and rep-MP3 PCR methods, respectively. Dendrograms of rep-PCR pattern similarity resolved by ALFA (Fig. 2) showed a consistent clustering of isolates of PFGE type 1 into one branch and of those of either PFGE type 2 or 3 into another branch.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of similarity of MRSA strains based on ALFA of inter-IS256 PCR, 16S-23S rRNA PCR, and MP3 PCR patterns produced by laboratories with optimal performance score compared with classification in PFGE type. The cut-off value for type identity was based on mean duplicate similarity values (Table 4).

Interlaboratory reproducibility.

A low interlaboratory reproducibility was observed with rep-PCR patterns resolved by agarose electrophoresis (Table 2). In general, MRSA strains exhibited different patterns by a given PCR method in different laboratories. In most cases, the same strain showed a common core of high-intensity amplified DNA fragments by a given PCR method in all laboratories, whereas less abundantly amplified DNA fragments were less reproducible. Among the rep-PCR typing methods tested, inter-IS256 PCR appeared to be less variable by center than the other methods (Table 2).

Inter-IS256 PCR patterns showed better interlaboratory reproducibility by ALFA than by agarose electrophoresis (Table 2). The interlaboratory reproducibility with ALFA of other rep-PCR techniques could not be assessed, since they were both tested in a single laboratory only.

DISCUSSION

Standardization of molecular typing methods is important in order to support large-scale epidemiological surveillance of infectious diseases with epidemic potential. Collaborative studies have shown limited interlaboratory reproducibility of AP-PCR and PFGE analysis for typing S. aureus (2, 22, 24). This study aimed at comparing the intralaboratory performance and interlaboratory reproducibility of three rep-PCR methods proposed for typing MRSA strains. In principle, these rep-PCR techniques offer the advantages of rapidity, low cost, and ease of use compared with PFGE analysis.

In the present study, a collection of well-defined MRSA strains characterized by epidemiological data and PFGE types were tested in 12 laboratories using their own thermocyclers but standard rep-PCR protocols, with minor deviations in only five centers. These rep-PCR methods produced arrays of DNA fragments which differed markedly between laboratories for the same strain and method. However, the clustering of strains into related patterns was more reproducible, a finding similar to that of a previous intercenter comparison of AP-PCR fingerprinting of MRSA strains (22). As various models of thermocyclers were used in different centers, this parameter may be partly responsible for the lack of precise pattern reproducibility between laboratories, underlining the key role of accurate temperature cycling in this respect. Minor deviations from the standard protocol in some centers possibly also contributed to this low reproducibility among laboratories. In contrast, a recent multicenter study of AP-PCR typing of Acinetobacter spp. using very controlled and standardized reagents, markers, and protocols showed good reproducibility between laboratories, with an average duplicate strain reproducibility of patterns of above 85% (11). The degree of experience with PCR methods tested in different laboratories was also quite variable, and better results might have been achieved if the experiments had been carried out after a training period in each center.

In this study, the best-performing center with inter-IS256 PCR typing achieved intracenter reproducibility and discrimination similar to those of PFGE. The finding that MRSA strains from different parts of Europe were better discriminated by inter-IS256 PCR typing than by rep-MP3 PCR typing is in discordance with a previous study (25) on S. aureus strains from the United States, which had concluded that rep-MP3 PCR typing was more discriminatory than inter-IS256 PCR typing. We also previously observed a lower discriminatory power of the inter-IS256 PCR method on U.S. strains compared with European strains of MRSA (6). These conflicting results seem to indicate that the repeat elements of the S. aureus genome used as a target in this assay may exhibit geographic variation in their polymorphism. Additional mapping and sequencing studies would be required to test this hypothesis.

The use of automated sequencers for fragment analysis moderately improved the resolution and interlaboratory reproducibility of inter-IS256 PCR patterns compared with agarose gel analysis. It should be noted, however, that the two centers using ALFA of inter-IS256 patterns made no deviation from the standard protocol. Previous studies have demonstrated the advantages of pattern analysis using a fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide primer on an automated sequencer for rep-PCR typing of several gram-negative bacilli (12), Acinetobacter species (10, 11), and MRSA (3, 5, 12).

Results obtained in the present study confirm that inter-IS256 PCR typing, used in an experienced laboratory, can reach excellent performance for typing MRSA strains, comparable to that obtained with PFGE analysis (6). The inter-IS256 PCR method can be used as a rapid typing tool for the local epidemiology of MRSA strains. Its turn-around time is only 5 h, compared to 2 or 3 days for PFGE. Rep-PCR typing based on the 16S-23S rDNA spacer and rep-MP3 element provided less discrimination but could be used as alternative rapid MRSA screening methods. It does not appear useful, however, to combine these rep-PCR techniques, as this does not increase typing resolution significantly.

Our results suggest that it would be difficult to fully standardize these rep-PCR typing methods using current technology. More technically complex genotyping techniques, like amplified fragment length polymorphism and restriction-sequence analysis of multiple polymorphic genes, seem more promising in terms of reproducibility (14, 17). Full sequence determination of a polymorphic locus, such as the protein A gene (spa) (16), or multilocus sequence typing (10) appear very promising for S. aureus typing. However, these assays are more labor intensive and less appropriate for routine use than rep-PCR techniques. Their main advantages, on the other hand, are complete reproducibility, good discriminatory power, and concordance with epidemiological data. Furthermore, sequence data provide easy comparative interpretation combined with ease of exchange via electronic networks (9, 16). The performance of these novel techniques still needs to be compared to current DNA fingerprinting techniques, such as rep-PCR and PFGE. Multicenter studies should be designed to verify that these methods allow interlaboratory exchange of genotypic data for monitoring geographic spread of MRSA strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Ready-To-Go RAPD beads were kindly provided by Amersham-Pharmacia-Biotech.

This study was an initiative of the European Study Group on Epidemiological Markers (ESGEM) of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bannerman T L, Hancock G A, Tenover F C, Miller J M. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as a remplacement for bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:551–555. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.551-555.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cookson B D, Aparicio P, Deplano A, Struelens M, Goering R, Marples R. Inter-centre comparison of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for the typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:179–184. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-3-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotter L, Daly M, Greer P, Cryan B, Fanning S. Motif-dependent DNA analysis of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus collection. Br J Biomed Sci. 1998;55:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuny C, Witte W. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus by PCR for DNA sequences flanked by transposon Tn916 target region and ribosomal binding site. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1502–1505. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1502-1505.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Vecchio V G, Petroziello J M, Gress M J, McCleskey F K, Melcher G P, Crouch H K, Lupski J R. Molecular genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus via fluorophore-enhanced repetitive-sequence PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2141–2144. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2141-2144.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deplano A, Vaneechoutte M, Verschraegen G, Struelens M J. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis strains by PCR analysis of inter-IS256 spacer length polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2580–2587. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2580-2587.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deplano A, Struelens M J. Nosocomial infections caused by staphylococci. In: Woodford N, Johnson A P, editors. Methods in molecular medicine, molecular bacteriology: protocols and clinical applications. Clifton, N.J: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 431–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deplano A, Witte W, Van Leeuwen W J, Brun Y, Struelens M J. Clonal dissemination of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Belgium and neighboring countries. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2000;6:239–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enright M C, Spratt B G. Multilocus sequence typing. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:482–487. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundmann H, Schneider C, Tichy H V, Simon R, Klare I, Hartung D, Dashner F D. Automated laser fluorescence analysis of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA: a rapid method for investigating nosocomial transmission of Acinetobacter baumannii. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:2948–2953. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-6-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grundmann H J, Towner K J, Dijkshoorn L, Gerner-Smidt P, Maher M, Seifert H, Vaneechoutte M. Multicenter study using standardized protocols and reagents for evaluation of reproducibility of PCR-based fingerprinting of Acinetobacter spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:3071–3077. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.12.3071-3077.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundmann H, Hahn A, Ehrenstein B, Geiger K, Just H, Dashner F D. Detection of cross-transmission of multiresistant gram-negative bacilli and Staphylococcus aureus in adult intensive care units by routine typing of clinical isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1999;5:355–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hookey J V, Edwards V, Patel S, Richardson J F, Cookson B D. Use of fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism (fAFLP) to characterise methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;37:7–15. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter P R. Reproducibility and indices of discriminatory power of microbial typing methods. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1903–1905. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1903-1905.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumari D N P, Peer V, Hawkey P M, Parnell P, Joseph N, Richardson J F, Cookson B. Comparison and application of ribosome spacer DNA amplicon polymorphisms and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for differentiation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:881–885. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.881-885.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shopsin B, Gomez M, Montgomery S O, Smith D H, Waddington M, Dodge D E, Bost D A, Riehman M, Naidich S, Kreiswirth B N. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphism region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3556–3563. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3556-3563.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sloos J H, Janssen P, van Boven C P A, Dijkshoorn L. AFLP™ typing of Staphylococcus epidermidis in multiple sequential blood cultures. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:221–228. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(98)80082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Struelens M J the European Study Group on Epidemiological Markers (ESGEM) Consensus guidelines for appropriate use and evaluation of microbial epidemiologic typing systems. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;2:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1996.tb00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tenover F C, Arbeit R, Archer G, Biddle J, Byrne S, Goering R, Hancock G, Hébert G A, Hill B, Hollis R, Jarvis W R, Kreiswirth B, Eisner W, Maslow J, McDougal L K, Miller J M, Mulligan M, Pfaller M A. Comparison of traditional and molecular methods of typing isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:407–415. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.407-415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trzcinski K, van Leeuwen W, van Belkum A, Grzesiowski P, Kluytmans J, Sijmons M, Verbrugh H, Witte W, Hryniewicz W. Two clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Poland. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996;3:198–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Belkum A, Kluytmans J, van Leeuwen W, Bax R, Quint W, Peters E, Fluit A, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C, van den Brule A, Koeleman H, Melchers W, Meis J, Elaichouni A, Vaneechoutte M, Moenens F, Maes N, Struelens M, Tenover F, Verbrugh H. Multicenter evaluation of arbitrarily primed PCR for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1537–1547. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1537-1547.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Belkum A, Vandenbergh M, Kessie G, Hussain Qadri S M, Lee G, Van den Braak N, Verbrugh H, Al-Ahdal M N. Genetic homogeneity among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from Saudi Arabia. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;4:365–369. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Belkum A, van Leeuwen W, Kaufmann M E, Cookson B, Forey F, Etienne J, Goering R, Tenover F, Steward C, O'Brien F, Grubb W, Tassios P, Legakis N, Morvan A, El Solh N, De Ryck R, Struelens M, Salmenlinna S, Vuopio-Varkila J, Kooistra M, Talens A, Witte W, Verbrugh H. Assessment of resolution and intercenter reproducibility of results of genotyping Staphylococcus aureus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI macrorestriction fragments: a multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1653–1659. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1653-1659.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Zee A, Verbakel H, van Zon J-C, Frenay I, van Belkum A, Peeters M, Buiting A, Bergmans A. Molecular genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus strains: comparison of repetitive element sequence-based PCR with various typing methods and isolation of a novel epidemicity marker. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:342–349. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.342-349.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]