Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is an important modification of eukaryotic mRNA. Since the first discovery of the corresponding demethylase and the subsequent identification of m6A as a dynamic modification, the function and mechanism of m6A in mammalian gene regulation have been extensively investigated. “Writer”, “eraser” and “reader” proteins are key proteins involved in the dynamic regulation of m6A modifications, through the anchoring, removal, and interpretation of m6A modifications, respectively. Remarkably, such dynamic modifications can regulate the progression of many diseases by affecting RNA splicing, translation, export and degradation. Emerging evidence has identified the relationship between m6A modifications and degenerative musculoskeletal diseases, such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, sarcopenia and degenerative spinal disorders. Here, we have comprehensively summarized the evidence of the pathogenesis of m6A modifications in degenerative musculoskeletal diseases. Moreover, the potential molecular mechanisms, regulatory functions and clinical implications of m6A modifications are thoroughly discussed. Our review may provide potential prospects for addressing key issues in further studies.

Keywords: N6-methyladenosine, degenerative musculoskeletal diseases, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, degenerative spinal disorders

Introduction

Emerging evidence has shown that methylation modifications have regulatory effects on the RNA of eukaryotic cells, and the common modifications include N1-methyladenosine (m1A), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), 5-methylcytosine (m5C), 7-methylguanosine (m7G), m1G, m2G, m6G, etc. (Shi et al., 2020). m6A is the most common of these modifications, accounting for the largest proportion, and approximately 20–40% of all transcripts encoded in mammalian cells are m6A-methylated (Frye et al., 2018). Each mammalian mRNA contains more than three m6A sites on average, in the consistent sequence of G (m6A) C (70%) and A (m6A) C (30%) (Wei et al., 1976; Wei and Moss, 1977). The m6A modification was first discovered by Prof. Desrosiers. R and his group in a groundbreaking experiment in the 1970s (Desrosiers et al., 1974). Subsequent studies have shown that it is a dynamic and reversible modification that is widely involved in physiological and pathological processes (Cao et al., 2016), including cellular aging (Casella et al., 2019), cancer progression (Lan et al., 2019) and inflammatory response (Zong et al., 2019). Specifically, m6A manipulates the splicing, export, translation and degradation of RNA through methylation and demethylation, controlled by a variety of enzymes, which in turn affect various physiological and pathological processes.

Degenerative musculoskeletal diseases are associated with aging and inflammatory conditions. These diseases include osteoarthritis (OA), osteoporosis (OP), intervertebral disc degeneration disease (IVDD), ossification of the ligamentum flavum (OLF) and sarcopenia (Ikegawa, 2013; Tabebordbar et al., 2013). Currently, a considerable body of epigenetic research is available in this area (Tu et al., 2019; Wijnen and Westendorf, 2019). Alterations in the levels of m6A play an important role in the progression of degenerative musculoskeletal diseases (Wu et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019).

In this review, we present a broad summary of the functions of m6A in the development and progression of various degenerative musculoskeletal diseases, with the aim of deepening our understanding of the association between m6A and degenerative lesions and exploring the preconceived idea that m6A can be a diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for degenerative musculoskeletal diseases in the future.

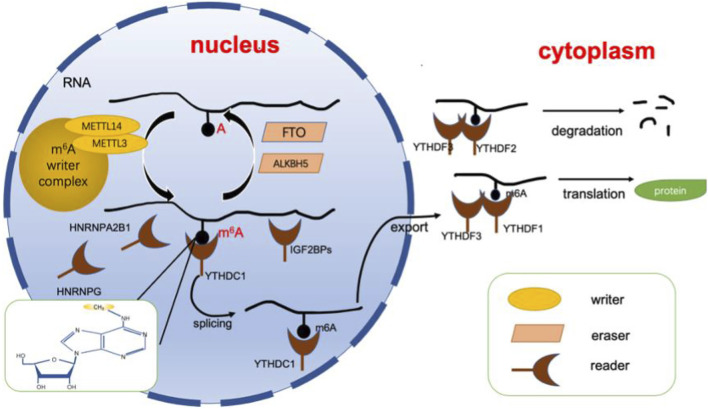

RNA m6A Modification

As mentioned above, the m6A modification is a dynamic and reversible epigenetic alteration and controls disease progression by affecting mRNA stability and functionality (Chen et al., 2019a; Li et al., 2020a; Qin et al., 2020). The position of m6A in the gene is highly conserved, and it is enriched in the consensus RRACH sequence of stop codons and long internal exons (R = G or A, H = A, C or U) (Dominissini et al., 2012). Current research shows that m6A can affect the splicing, translation, export, and degradation of mRNA through three types of key proteins. These three types of proteins are known as m6A writers, erasers and readers (Chen et al., 2019b). The writer and eraser proteins dynamically regulate m6A levels, while the readers determine the ultimate fate of mRNA (Shi et al., 2019). In this section, we will analyze and summarize the functions of these three types of proteins (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Dynamic regulation of RNA m6A modification. The dynamic regulation of RNA m6 A modifications relies on writers (including METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, etc.) erasers (including FTO, ALKBH5, etc.), and readers (including YTHDFs, YTHDCs, HNRNPs, etc.). Adenosine located in RNA is recognized by writers for methylation, while erasers can catalyze the demethylation of m6A. Finally, the modification is recognized by the reader protein, allowing it to perform its function. ALKBH5, alkB homolog 5; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein. m6A, N6-methyladenosine; YTHDF, YTH N6-methyladenosine, RNA binding protein, YTHDC, YTH domain containing protein, HNRNP, heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein.

m6A Writer

m6A is incorporated into RNA by a multisubunit writing complex in a highly specific manner (Bokar et al., 1997). This multisubunit writing complex is the m6A writer, and the following subunits have been identified: METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, VIRMA, METTl16, etc. METTL3 and METTL14 dominate most of the m6A modifications and are the core components of the entire complex. Both of them contain S-adenosylmethionine binding sequences, which can add methyl groups to adenosine and form a heterodimeric complex to regulate m6A (Geula et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016a). Analysis has shown that METTL3 functions as a catalytic subunit, while METTL14 is an important component facilitating binding to RNA (Wang et al., 2016b). WTAP itself does not have methyltransferase activity; it binds to METTL3/14 as a cofactor that helps METTL3/14 localize to nuclear patches and is an essential protein for recruiting substrates (Ping et al., 2014). In addition, it has been shown that WTAP relies on METTL3 to regulate its homeostasis (Sorci et al., 2018). On the other hand, VIRMA functions to promote the binding of m6A to the 3′UTR (Yue et al., 2018).

m6A Eraser

In contrast to the function of the m6A writer, the m6A eraser is responsible for the demethylation of m6A to adenosine (Jia et al., 2011). It is important for realization of the dynamic and reversible modification function of m6A (Zhao et al., 2017). Demethylation enzymes include fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkB homolog5 (ALKBH5).

The demethylase activity of FTO was first discovered by Prof. He’s group (Jia et al., 2011). It shows homology to the ALKB dioxygenase family. The demethylation function of FTO occurs by oxidizing m6A to N6-hydroxymethyladenosine (hm6A) and N6-formyladenosine (f6A), which eventually becomes simply A (Fu et al., 2013). Although the actual substrate for the action of FTO is N6,2-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), a modification with a chemical structure identical to that of m6A in the base part is found near the 5′ cap in mRNA (Mauer et al., 2017). However, a follow-up study showed that FTO had demethylation activity for both m6A and m6Am: m6A is mainly located in the nucleus, whereas the major substrate in the cytoplasm is m6Am (Wei et al., 2018).

ALKBH5 was the second enzyme to be discovered as an m6A-based demethylase (Zheng et al., 2013). The role of ALKBH5 can be summarized as follows: 1. Knockdown of the ALKBH5 gene has no effect on the normal growth and development of mice but has an impact on their spermatogenesis. ALKBH5 is enriched in testes and female ovaries, which suggests that the demethylase activity of ALKBH5 is important for germ cell development (Zheng et al., 2013). 2. The altered expression levels of ALKBH5 affect m6A modifications, which play an important role in several diseases via the regulation of m6A. For example, ALKBH5 expression is decreased in bladder cancer tissues and cells, which correlate with poor patient prognosis. The overexpression of ALKBH5 could inhibit disease progression through the m6A-CK2a-mediated glycolytic pathway and increase the sensitivity of bladder cancer to cisplatin (Yu et al., 2021).

m6A Reader

m6A readers are a class of proteins that recognize m6A modifications on RNA and determine the function of transcripts. These readers include the YT521-B homology (YTH) domain, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, and insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins.

The crystal structure of the human YTH domain revealed that it contains a recognition pocket consisting of three conserved tryptophan residues for specific recognition of methylation modifications (Luo and Tong, 2014; Xu et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2014). The most widely studied YT521-B homology (YTH) domains include YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 1–3 (YTHDF1-3) and YTH domain containing protein 1–2 (YTHDC1-2). YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein is mainly localized in the cytoplasm, while YTH domain-containing protein is localized in the nucleus (Reichel et al., 2019). Among them, YTHDF1 promotes the translation of mRNA mainly by affecting the translation mechanism (Wang et al., 2015). On the other hand, YTHDF2 can mediate the degradation of its target m6A transcripts by reducing their stability (Li et al., 2018). As a cofactor of YTHDF1 and YTHDF2, YTHDF3 can synergize with both YTHDF1 and YTHDF2 to promote translation and degradation, respectively (Ni et al., 2019). However, YTH domain-containing proteins have other functions. YTHDC1 interacts with m6A in nuclear RNA to regulate splicing of premRNA (Kasowitz et al., 2018) and promotes nuclear export of m6A-modified RNA (Roundtree, 2017). Interestingly, YTHDC2 seems to be quite important for fertility, as it is mainly enriched in the testis, mediates mRNA stability and translation and regulates spermatogenesis (Hsu et al., 2017). In addition, it promotes the translation of the m6A methylation-modified RNA coding region (Mao et al., 2019).

HNRNP is a group of RNA binding proteins responsible for precursor mRNA shearing and stabilization of newly transcribed precursor RNA (Geuens et al., 2016). For instance, hnRNPA2B1 can affect the shear processing of precursor miRNAs by recognizing and binding to sites containing RGm6AC sequences (Alarcón et al., 2015). HNRNPC was one of the first HNRNP proteins identified to be involved in shearing, and it requires oligomerization with other HNRNPC monomers to form a specific binding RNA interaction (Cieniková et al., 2015). HNRNPC preferentially binds single-stranded U-tracts (5 or more contiguous uridines) and affects nascent RNA shearing, translation, etc. (Liu et al., 2015). Finally, HNRNPG contains a low-complexity region that recognizes structural changes mediated by m6A modifications involved in the shearing of cotranscribed precursor mRNAs (Liu et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2019).

Finally, IGF2BP is able to target transcripts by recognizing GGAC sequences rich in m6A modifications; it promotes the translation of mRNA by recruiting mRNA stabilizers such as HuR and MATR3, which enhance the stability of mRNA (Huang et al., 2018).

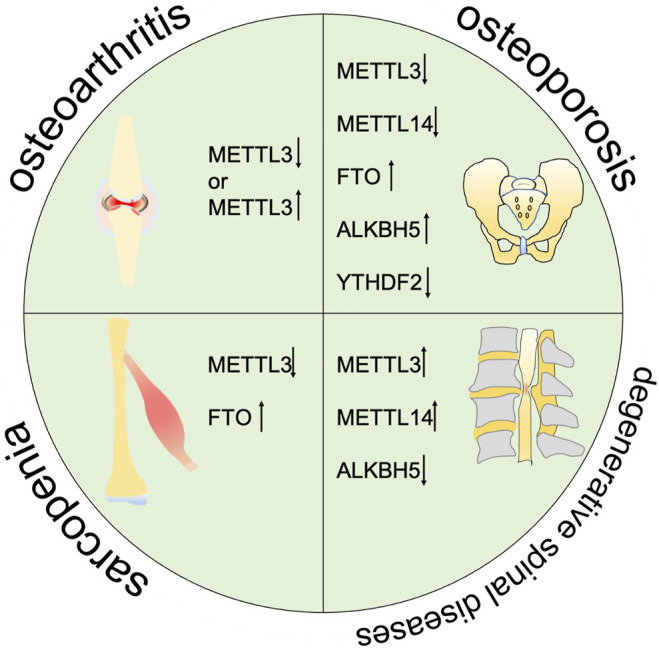

Roles of m6A in Degenerative Musculoskeletal Disorders

Degenerative musculoskeletal diseases are associated with aging and inflammatory conditions. m6A modifications have been considered to be involved in degenerative musculoskeletal diseases. However, the molecular mechanisms and functional details are not fully understood. Thus, we summarize the current evidence on the pleiotropic function of m6A in degenerative musculoskeletal diseases (Figure 2, Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

m6A is correlated with the progression of multiple degenerative diseases including osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and degenarative spinal diseases.

TABLE 1.

The role of m6A in degenerative musculoskeletal diseases.

| disease | m6A regulator | Cell type | Target gene/signal pathway | Roles in disease | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA | METTL3 | ATDC5 Cell | NF- B signaling | Promoting inflammatory response, collagen synthesis and degradation, and cell apoptosis in chondrocytes | Liu et al. (2019) |

| METTL3 | SW1353 cell | NF- B signaling | Promoting inflammatory response, degradation of extracellular matrix | Sang et al. (2021) | |

| OP | METTL3 | Primary MSCs | PTH/PTH1r signaling | Impairing bone formation | Wu et al. (2018) |

| METTL3 | BMSCs | PI3K-AKT signaling axis | Inhibiting osteogenic differentiation | Tian et al. (2019) | |

| METTL3 | BMSCs | JAK1/STAT5/C/EBP signaling axis | Suppressing the early lipid differentiation of BMSCs | Yao et al. (2019) | |

| METTL3 | BMSCs | PremiR-320/RUNX2 | Promoting OP development | Yan et al. (2020) | |

| METTL14 | Osteoblasts | miR-103-3p | miR-103-3p can target METTL14 to inhibit osteogenic differentiation | Sun et al. (2021) | |

| FTO | BMSCs | GDF11- FTO - PPAR signal pathway | Promoting differentiation of BMSCs to adipocytes | Shen et al. (2018) | |

| FTO | BMSCs | miR-149-3p | miR-149-3p promotes osteogenic differentiation by targeting FTO. | Li et al. (2019) | |

| FTO | BMSCs | miR-22-3p and MYC/PI3K/AKT signal pathway | miR-22-3p in BMSC-derived EVs can inhibit MYC/PI3K/AKT signal pathway by targeting FTO to stimulate osteogenic differentiation | Zhang et al. (2020a) | |

| ALKBH5 | MSCs | PRMT6 mRNA | Inhibiting the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs through PRMT6 | Li et al. (2021) | |

| Sarcopenia | METTL3 | C2C12 cell | MyoD mRNA | Mettl3 is required for MyoD mRNA expression in proliferative myoblasts | Kudou et al. (2017) |

| METTL3 | C2C12/MuSCs | - | METTL3 regulates the differentiation of MuSCs | Gheller et al. (2020) | |

| METTL3 | MuSCs | Notch Signaling | Regulating the notch signaling pathway and controlling muscle regeneration and repair with the METTL3-m6A-YTHDF1 axis | Liang et al. (2021) | |

| FTO | C2C12 cell | mTOR-PGC-1α pathway | Regulating mTOR-PGC-1a-mediated intramitochondrial synthesis and muscle cell differentiation | Wang et al. (2017) | |

| FTO | C2C12 cell | AMPK | Reducing lipid accumulation by inhibiting the demethylase activity of FTO. | Wu et al. (2017) | |

| Degenerative spinal diseases | METTL14 | HNPCs | miR-34a-5p | METTL14 promotes he senescence of nucleus pulposus cell by increasing the expression of miR-34a-5p | Zhu et al. (2021) |

| METTL3 | chondrocytes | PI3K/AKT signaling | METTL3 promotes the degeneration by inhibit the protective effect of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway on endplate cartilage | Xiao et al. (2020) | |

| METTL3 | Primary Ligament Fibroblasts | XIST/miR-302a-3p/USP8 Axis | Regulating the ossification of primary ligament fibroblasts | Yuan et al. (2021) | |

| ALKBH5 | Ligamentum Flavum Cells | AKT pathway | Promoting ligamentum flavum cell osteogenesis by decreasing BMP2 demethylation and activating Akt signaling pathway | Wang et al. (2020b) |

ALKBH5, alkB homolog 5; BMSC, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell; FTO, fat mass and obesity-associated protein; m6A, N6-methyladenosine; METTL3, methyltransferase-like 3; METTL14, methyltransferase-like 14; OA, osteoarthritis; OP, osteoporosis. HNPCs, human nucleus pulposus cell. MuSCs, Muscle-specific adult stem cells.

m6A in Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a chronic joint disease represented by symptoms such as pain, stiffness, joint deformity and limited joint movement. Elderly females and overweight people are most affected (Sharma, 2021). Tang. X et al. indicated that the prevalence of knee OA in China was 8.1%, while a later study by Li. Z et al. showed that the prevalence of patellofemoral OA had increased to 23.9% (Tang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2020b). A worldwide study showed that there were approximately 301.1 million prevalent cases of hip and knee OA, which was a 9.3% increase from 1990 to 2017 (Safiri et al., 2020). As the aged population becomes more sophisticated, OA has become one of the most important diseases affecting quality of life, which imposes a huge economic burden on society (Hunter et al., 2014). Pathologically, the main mechanism of OA is the degradation of the articular cartilage matrix, including type II collagen and a small amount of type IX and XI collagen, which ultimately causes total joint damage (Hunter and Bierma-Zeinstra, 2019). In addition, the development of OA is associated with senescent cells, which are linked to aging-related mitochondrial dysfunction and associated oxidative stress (Coryell et al., 2021). Inflammatory factors such as IL-1 and TNF- cooperate with chemokines to participate in the progression of OA (Chen et al., 2017). It is now believed that the study of the relationship between epigenetic regulation and inflammatory factors will be the way forward for OA treatment. Thus, the relationship between m6A modifications and OA has attracted the attention of researchers.

Although both Liu. Q et al. and Sang. W et al. concluded that METTL3 affects OA development by regulating the inflammatory response and extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, and their experiments presented different results. Liu. Q et al. showed that METTL3 expression was increased in IL-1 -treated ATDC5 cells. Silencing METTL3 expression inhibited the level of inflammatory cytokines and the transactivation of the NF- B signaling pathway, which delayed the progression of OA. Moreover, it could inhibit the synthesis of ECM by downregulating the expression of MMP13 and COII-X (Liu et al., 2019). Sang. W et al. showed that METTL3 expression was reduced in patient tissues and in IL-1 -treated SW1353 cells. Overexpression of METTL3 resulted in decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines and promoted the expression of p-65 protein and p-ERK to activate the NF- B signaling pathway. Overexpression of METTL3 also regulated the balance between TIMPs and MMPs to affect the degradation of ECM (Sang et al., 2021). The discrepancy in experimental results was speculated to be due to the following two reasons: 1. differences in the selection of cell models: ATDC5 cells and SW1353 cells have a limited ability to mimic primary articular chondrocytes; 2. the normal control selected by Sang. W et al. collected articular cartilage from patients who underwent replacement for femoral neck fractures (for ethical reasons), although whether this is fully consistent with normal human METTL3 expression needs to be reconsidered; 3. Liu. Q et al. verified the expression of METTL3 in experimental osteoarthritis, which might not reflect the actual expression of OP patients. In addition to the methylation enzyme METTL3, the demethylase FTO has also been studied for its effect on the development of OA. It was shown that FTO-mediated overweight could lead to increased susceptibility to OA (arc et al., 2012; Panoutsopoulou et al., 2014). However, both Wang. Y et al. and Dai. J et al. demonstrated that the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs8044769 of FTO was not associated with OA in the Chinese population, and some other genes may account for it. Therefore, the correlation between FTO and OA needs further investigation (Wang et al., 2016c; Dai et al., 2018).

m6A in Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis (OP), a disease characterized by low bone mass and altered bone microarchitecture (Johnston and Dagar, 2020), is a complex multifactorial disease. Age, sex, BMI (body mass index), postmenopausal women, and previous history of fracture are considered risk factors (Rubin et al., 2013). Altered bone quality and bone microarchitecture in OP cause increased bone brittleness and susceptibility to fracture (Compston et al., 2019), which seriously affect quality of life (Cauley, 2017). Zeng. Q et al. hypothesized that an estimated 10.9 million men and 49.3 million women suffered from OP in China by 2019, and the age-standardized prevalence rates of OP in Chinese men and women over 50 years old were 6.46 and 29.13%, respectively (Zeng et al., 2019). The United States and the United Kingdom spend approximately US$17.9 billion and £4 billion each year on osteoporosis-related fractures (Clynes et al., 2020), which is a huge economic burden for society. However, the current treatment protocols for OP have some issues, such as a long treatment cycle time and poor patient compliance (Qaseem et al., 2017; Estell and Rosen, 2021). Therefore, it is important and intriguing to explore OP treatment from the perspective of epigenetics (de Nigris et al., 2021).

A genome-wide identification study showed that 138, 125 and 993 m6A SNPs were associated with density issues of the femoral neck, lumbar spine and heel, respectively, at significant levels (Mo et al., 2018). The differentiation tendency of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) is closely associated with the development of OP, and the imbalance between osteogenic and lipogenic differentiation of BMSCs is often considered the basis for the development of OP. BMSC differentiation into adipocytes may lead to decreased bone formation, which contributes to the development of OP (Chen et al., 2016; Qadir et al., 2020). Coincidentally, as an m6A-modified demethylase, FTO mediates demethylation to regulate mRNA shearing, which is required for lipogenesis (Zhao et al., 2014). Importantly, Guo. Y et al. found an association between FTO and OP phenotype (Guo et al., 2011). Shen. G et al. found that the GDF11-FTO-PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ) axis controls the differentiation of BMSCs to adipocytes and reduces bone formation in OP patients. The main mechanism is that the upregulated GDF11-FTO signaling targets PPAR , which is dependent on FTO demethylase activity. This can reduce m6A modification of the mRNA encoding PPAR , prolong the half-life period, and ultimately contribute to differentiation of BMSCs into adipocytes (Shen et al., 2018). In addition, miR-149-3p can promote the differentiation of BMSCs into osteoblasts by binding to the mRNA 3′UTR of FTO, which in turn inhibits its own expression (Li et al., 2019). Notably, to investigate the effect of extracellular capsule-encapsulated miR-22-3p from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on osteogenic differentiation, Zhang. X et al. performed a series of experiments. They found that miR-22-3p in BMSC-derived EVs can inhibit the MYC/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by targeting FTO to stimulate osteogenic differentiation (Zhang et al., 2020a). Interestingly, although FTO could inhibit the differentiation of BMSCs to osteoblasts in OP, it had a protective effect on differentiated cells. Studies in normal mouse models showed that the demethylase activity of FTO is required for normal bone growth and calcification in mice (Sachse et al., 2018). FTO is also able to avoid genotoxic damage to osteoblasts by stabilizing endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway components, such as Hsp70 (which inhibits NF- B signaling pathway activation) (Zhang et al., 2019). As another demethylase, ALKBH5 could also negatively regulate the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs through PRMT6 (protein arginine methyltransferase 6) (Li et al., 2021).

As m6A-modified methylesterases, METTL3 and METTL14 have likewise received the attention of researchers. METTL3-and METTL14-mediated m6A methylation affects the differentiation of BMSCs through multiple pathways. On the one hand, METTL3 knockdown in mice could decrease the translation efficiency of PTH1r (parathyroid hormone receptor-1) and reduce its expression in vivo, which interferes with the osteogenesis of PTH (parathyroid hormone) via the PTH/PTH1r signaling axis to induce an OP-related pathological phenotype (Wu et al., 2018). Moreover, knockdown of METTl3 could inhibit osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs by suppressing VEGF-a expression and activation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in vivo (Tian et al., 2019). On the other hand, METTL3 could promote the modification of m6A in JAK1 mRNA and reduce JAK1 expression by recognizing and destabilizing JAK1 through YTHDF2, thereby inhibiting the activation of the JAK1/STAT5/C/EBP signaling pathway. METTL3 could also suppress the early lipid differentiation of BMSCs (Yao et al., 2019). In addition, Yan. G et al. showed that the downregulation of METTL3 in BMSCs could reduce the expression of RUNX2 and PremiR320 by inhibiting their methylation (Yan et al., 2020). RUNX2 is an important regulator of osteogenic precursor cells in vivo and is involved in bone mineral deposition and the progression of OP (Komori, 2019). As another m6A-modified methylation enzyme, METTL14 can be targeted by miR-103-3p to inhibit osteogenic differentiation. Moreover, it can also modulate miRNA activity through DGCR8 in a feedback-dependent manner, which suggests that the miR-103-3p/METTL14/m6A signaling axis is a potential target in the treatment of OP (Sun et al., 2021).

Emerging evidence has shown that the knockdown of the m6A-modified reader protein YTHDF2 can enhance the phosphorylation of IKKα/β, IκBα, ERK, p38 and JNK in the NF- B and MAPK signaling pathways and then mediate LPS-induced osteoclast formation and inflammation (Fang et al., 2021). This indicates that the role of m6A reader proteins in OP is important, which provides a novel pathway for future research.

In summary, the relationship between m6A modifications and OP is closely associated with the regulation of BMSC differentiation. The modalities can be summarized as follows: 1. METTL3 and MEETTL14 can mediate the differentiation of BMSCs toward osteoblasts; 2. FTO can mediate the differentiation of BMSCs toward adipocytes; 3. FTO can protect the cells from genotoxic injury; 4. ALKBH5 negatively regulates the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs; 5. YTHDF2 reader protein can mediate osteoclast formation. Current research on the relationship between m6A and osteoporosis mainly focuses on the differentiation and regulation of BMSCs. Given that the imbalance of bone remodeling due to abnormal differentiation of osteoclasts is an important pathological basis of osteoporosis and that METTL3 has been shown to regulate osteoclast differentiation (Li et al., 2020c), the mechanism by which m6A modification regulates osteoclast differentiation in osteoporotic patients needs to be further addressed in the future.

Thus, it appears that there may be a dual role of m6A modification in the progression of OP. Understanding the mechanism associated with m6A modification with this dual relationship could provide promising insight for the prevention and treatment of OP.

m6A in Sarcopenia

Sarcopenia, a disease characterized by a decrease in muscle mass and function associated with age-related progression, was first identified by Rosenberg et al., in 1997 (Rosenberg, 1997). Sarcopenia often results in many adverse outcomes, such as falls, decreased function, fractures and even death. These adverse outcomes can lead to increased hospital stays and exacerbate the sarcopenia process (Coker and Wolfe, 2012; Dhillon and Hasni, 2017; Yeung et al., 2019). The etiology of sarcopenia can be described as follows: 1. Age: muscle content decreases with age and reflects the trend of development. However, the speed of muscle loss in sarcopenia patients is far beyond that in the normal population (Larsson et al., 2019); 2. Chronic low-titer systemic inflammatory state of the body: the body of a sarcopenia patient always presents a chronic low-titer systemic inflammatory state with cachexia, which could increase physical exertion and accelerate muscle decrease (Muscaritoli et al., 2010). Nevertheless, the mechanism of sarcopenia pathogenesis is not yet well understood.

With regard to the relationship between m6A modification and sarcopenia, current research has mainly focused on muscle stem cell differentiation. Kudou et al. found that muscle stem cells require MyoD regulators to maintain differentiation potential, and m6A modifications of mRNA encoding MyoD are enriched in the 5′UTR. The m6A methylation enzyme METTl3 can stabilize MyoD RNA by promoting pro-myogenic differentiation mRNA processing in proliferating cells. Knockdown of METTL3 can significantly downregulate processed MyoD mRNA expression in adult myoblasts (Kudou et al., 2017). Knockdown of METTL3 in mouse C2C12 cells and muscle stem cells can reduce the level of m6A modification and lead to premature differentiation of adult myoblasts, suggesting an important role of METTL3 in m6A regulation (Gheller et al., 2020). METTL3 can enhance protein expression by increasing mRNA m6A modification via the Notch signaling pathway and increase the translation efficiency of mRNAs through the YTHDF1 reader protein. This suggests that METTL3 is essential for regulating muscle stem cells and promoting muscle injury recovery (Liang et al., 2021).

Similarly, FTO demethylases have also been found to be involved in the regulation of muscle stem cells. Increased expression of FTO is observed during muscle cell differentiation and regulates mTOR-PGC-1a-mediated intramitochondrial synthesis through its own demethylase activity (affecting muscle cell differentiation) (Wang et al., 2017). In addition, the expression of AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinases) is a key regulator of skeletal muscle lipid metabolism and m6A modification in skeletal muscle. These proteins showed a negative correlation with lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle. Lipid accumulation may be reduced by inhibiting the demethylase activity of FTO and increasing the level of m6A modification (Wu et al., 2017).

In summary, although the existing evidence does not directly verify the relationship between m6A modification and sarcopenia, the ability of m6A to regulate the differentiation of muscle stem cells will provide us with a future direction. Given the variety of sarcopenia mouse models that have been established (Xie et al., 2021), novel methods of sarcopenia research can be developed. Interestingly, given the regulatory role of FTO in muscle differentiation and lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle, FTO may be considered a key regulatory factor specifically in sarcopenic obesity (high-risk disease characterized by both sarcopenia and obesity (Batsis and Villareal, 2018)).

m6A in Degenerative Spinal Disease

Degenerative spinal disorders are a group of age- and aging-related structural abnormalities of the spine, including cervical spondylosis, lumbar disc herniation, spinal stenosis and posterior longitudinal ligament calcification (Ailon et al., 2015; Davies et al., 2018). These constitute a type of clinical syndrome caused by degenerative alternations or long-term strain as age increases. A structural imbalance in the spine initiates repair in the body and stimulates bone hyperplasia, ligament thickening and ossification, which eventually lead to the emergence of spinal cord, nerve root or vertebral dynamic compression. This imbalance can seriously affect the quality of life of patients and even endanger life (Wang et al., 2016d; Badhiwala et al., 2020). Abnormal nucleus pulposus cells are a crucial cause of lower back pain (a common chronic inflammatory pain closely related to disc degeneration in which IL-1 and TNF- are key factors (Cunha et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020a)). Zhu. H et al. showed that TNF- and TNF- can promote the expression of miR-34a-5p through the methylation enzyme activity of METTL14 in myeloid cells, which may increase the m6A modification of the mRNA encoding miR-34a-5p (targeting the utility of SIRT1 inhibition). Eventually, this promotes the senescence of nucleus pulposus cells (Zhu et al., 2021). As another methylesterase, METTL3 is able to promote inflammation by binding DGCR8 to positively regulate the m6A modification level of pri-miR-365-3p in a CFA-induced chronic inflammation model (Zhang et al., 2020b). In IVDD, degeneration of endplate chondrocytes may also lead to pathological alterations. Xiao. L et al. found that METTL3-mediated m6A modification was closely associated with degeneration (Xiao et al., 2020). METTL3 expression was upregulated in IL-1 -mediated inflammatory cells: METTL3 upregulation promoted the breakdown of pri-miR-126-5p to increase miR-126-5p expression. Subsequently, miR-126 could downregulate PIK3R2 expression to inhibit the protective effect of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Xiao et al., 2020). METTl3 increases the level of m6A modification of lncRNA XIST during posterior longitudinal ligament ossification and subsequently affects the ossification of primary ligament fibroblasts by influencing the miR-302a-3p/USP8 axis (Yuan et al., 2021). During ligamentum flavum ossification, the ALKBH5 demethylase can promote ligamentum flavum cell osteogenesis by decreasing BMP2 demethylation and activating the Akt signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2020b).

Thus, although research on the role of m6A in the process of spinal degeneration is still in its infancy, a close association between the regulation of m6A modifications and spinal degeneration has been identified. Both the METTL3 and METTL14 methylation enzymes and the ALKBH5 demethylase can influence the progression of spinal degeneration by regulating the level of m6A modifications (affecting the level of inflammation or differentiation tendency). The excellent studies described here provide novel insight for the diagnosis and treatment of degenerative spinal disorders in the future.

Perspective

Currently, accurately describing the specific mechanisms of m6A in degenerative musculoskeletal diseases remains a great challenge. The impact of m6A modifications on degenerative musculoskeletal diseases remains to be addressed. First, the current SNP detection methods, such as high-resolution and high-throughput detection, need to be improved. Second, research on OA, sarcopenia and degenerative spinal diseases is relatively limited, and we hope that subsequent investigators will more thoroughly examine the mechanisms involved. Third, although an important role of YTHDF2 in degenerative musculoskeletal diseases has been observed, the role of the reader protein has been less well investigated (Fang et al., 2021). Finally, current evidence suggests that targeting m6A modifications may be a promising therapeutic option (Peng et al., 2019; Bedi et al., 2020). However, more in-depth studies on safety and efficacy are still needed.

Conclusion

Recently, researchers have begun to investigate the role and importance of m6A modifications in a variety of diseases. However, only a small number of these studies have focused on degenerative issues. In this review, we summarize the role and regulatory mechanisms of m6A in the pathogenesis of degenerative musculoskeletal diseases. During transcription, the level of transcript m6A modification is closely associated with the development and repair of bones, muscles and soft tissues. The regulation of the m6A modification level at the lesion site requires functional coordination among writer, eraser and reader proteins, and the abnormal expression of each of these proteins may contribute to exacerbating degeneration. Therefore, the dynamic balance of m6A modifications is crucial for degenerative musculoskeletal diseases. Unfortunately, the current treatment options for degenerative musculoskeletal diseases are not yet well understood, and most patients are ultimately likely to receive surgical treatment. Research on the relationship between m6A modifications and degenerative musculoskeletal diseases will provide us with novel insights for the diagnosis and treatment of these diseases to control their progression and long-term prognosis by regulating m6A modification.

Author Contributions

HL and WX decided on the content, wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures. YZ and YL conceptualized and revised this review. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0111900), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81874030, 82072506, 82102581), National Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2021M693562), Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (No.2020JJ3060), Provincial Outstanding Postdoctoral Innovative Talents Program of Hunan (2021RC2020), Provincial Clinical Medical Technology Innovation Project of Hunan (No.2020SK53709), the Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Hunan Province (No.2021075), Innovation-Driven Project of Central South university (No.2020CX045), Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (No.320.6750.2020-03-14), CMA Young and Middle-aged Doctors Outstanding Development Program--Osteoporosis Specialized Scientific Research Fund Project (No.G-X-2019-1107-12), the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province (No.2018SK 2076), the Key Program of Health Commission of Hunan Province (No.20201902), Young Investigator Grant of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University (2020Q14) and the General Project of Hunan University Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program in 2021(S2021105330398).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Ailon T., Smith J. S., Shaffrey C. I., Lenke L. G., Brodke D., Harrop J. S., et al. (2015). Degenerative Spinal Deformity. Neurosurgery 77 (Suppl. 4), S75–S91. 10.1227/neu.0000000000000938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón C. R., Goodarzi H., Lee H., Liu X., Tavazoie S., Tavazoie S. F. (2015). HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m6A-dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell 162 (6), 1299–1308. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- arc O. C., au fnm., Zeggini E., Panoutsopoulou K., Southam L., Rayner N. W., et al. (2012). Identification of New Susceptibility Loci for Osteoarthritis (arcOGEN): a Genome-wide Association Study. Lancet 380 (9844), 815–823. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60681-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badhiwala J. H., Ahuja C. S., Akbar M. A., Witiw C. D., Nassiri F., Furlan J. C., et al. (2020). Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy - Update and Future Directions. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 16 (2), 108–124. 10.1038/s41582-019-0303-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsis J. A., Villareal D. T. (2018). Sarcopenic Obesity in Older Adults: Aetiology, Epidemiology and Treatment Strategies. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14 (9), 513–537. 10.1038/s41574-018-0062-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi R. K., Huang D., Eberle S. A., Wiedmer L., Śledź P., Caflisch A. (2020). Small‐Molecule Inhibitors of METTL3, the Major Human Epitranscriptomic Writer. ChemMedChem 15 (9), 744–748. 10.1002/cmdc.202000011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokar J. A., Shambaugh M. E., Polayes D., Matera A. G., Rottman F. M. (1997). Purification and cDNA Cloning of the AdoMet-Binding Subunit of the Human mRNA (N6-Adenosine)-Methyltransferase. Rna 3 (11), 1233–1247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G., Li H.-B., Yin Z., Flavell R. A. (2016). Recent Advances in Dynamic M 6 A RNA Modification. Open Biol. 6 (4), 160003. 10.1098/rsob.160003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casella G., Tsitsipatis D., Abdelmohsen K., Gorospe M. (2019). mRNA Methylation in Cell Senescence. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 10 (6), e1547. 10.1002/wrna.1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauley J. A. (2017). Osteoporosis: Fracture Epidemiology Update 2016. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 29 (2), 150–156. 10.1097/bor.0000000000000365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Shen J., Zhao W., Wang T., Han L., Hamilton J. L., et al. (2017). Osteoarthritis: toward a Comprehensive Understanding of Pathological Mechanism. Bone Res. 5, 16044. 10.1038/boneres.2016.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Shou P., Zheng C., Jiang M., Cao G., Yang Q., et al. (2016). Fate Decision of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Adipocytes or Osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ 23 (7), 1128–1139. 10.1038/cdd.2015.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-Y., Zhang J., Zhu J.-S. (2019). The Role of m6A RNA Methylation in Human Cancer. Mol. Cancer 18 (1), 103. 10.1186/s12943-019-1033-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Peng C., Chen J., Chen D., Yang B., He B., et al. (2019). WTAP Facilitates Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent Epigenetic Silencing of ETS1. Mol. Cancer 18 (1), 127. 10.1186/s12943-019-1053-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieniková Z., Jayne S., Damberger F. F., Allain F. H.-T., Maris C. (2015). Evidence for Cooperative Tandem Binding of hnRNP C RRMs in mRNA Processing. RNA 21 (11), 1931–1942. 10.1261/rna.052373.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clynes M. A., Harvey N. C., Curtis E. M., Fuggle N. R., Dennison E. M., Cooper C. (2020). The Epidemiology of Osteoporosis. Br. Med. Bull. 133 (1), 105–117. 10.1093/bmb/ldaa005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coker R. H., Wolfe R. R. (2012). Bedrest and Sarcopenia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 15 (1), 7–11. 10.1097/mco.0b013e32834da629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compston J. E., McClung M. R., Leslie W. D. (2019). Osteoporosis. The Lancet 393 (10169), 364–376. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell P. R., Diekman B. O., Loeser R. F. (2021). Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications of Cellular Senescence in Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 17 (1), 47–57. 10.1038/s41584-020-00533-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha C., Silva A. J., Pereira P., Vaz R., Gonçalves R. M., Barbosa M. A. (2018). The Inflammatory Response in the Regression of Lumbar Disc Herniation. Arthritis Res. Ther. 20 (1), 251. 10.1186/s13075-018-1743-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J., Ying P., Shi D., Hou H., Sun Y., Xu Z., et al. (2018). FTO Variant Is Not Associated with Osteoarthritis in the Chinese Han Population: Replication Study for a Genome-wide Association Study Identified Risk Loci. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 13 (1), 65. 10.1186/s13018-018-0769-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies B. M., Mowforth O. D., Smith E. K., Kotter M. R. (2018). Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy. BMJ 360, k186. 10.1136/bmj.k186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Nigris F., Ruosi C., Colella G., Napoli C. (2021). Epigenetic Therapies of Osteoporosis. Bone 142, 115680. 10.1016/j.bone.2020.115680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers R., Friderici K., Rottman F. (1974). Identification of Methylated Nucleosides in Messenger RNA from Novikoff Hepatoma Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 71 (10), 3971–3975. 10.1073/pnas.71.10.3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon R. J. S., Hasni S. (2017). Pathogenesis and Management of Sarcopenia. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 33 (1), 17–26. 10.1016/j.cger.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., et al. (2012). Topology of the Human and Mouse m6A RNA Methylomes Revealed by m6A-Seq. Nature 485 (7397), 201–206. 10.1038/nature11112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estell E. G., Rosen C. J. (2021). Emerging Insights into the Comparative Effectiveness of Anabolic Therapies for Osteoporosis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17 (1), 31–46. 10.1038/s41574-020-00426-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang C., He M., Li D., Xu Q. (2021). YTHDF2 Mediates LPS-Induced Osteoclastogenesis and Inflammatory Response via the NF-Κb and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Cell Signal. 85, 110060. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye M., Harada B. T., Behm M., He C. (2018). RNA Modifications Modulate Gene Expression during Development. Science 361 (6409), 1346–1349. 10.1126/science.aau1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Jia G., Pang X., Wang R. N., Wang X., Li C. J., et al. (2013). FTO-mediated Formation of N6-Hydroxymethyladenosine and N6-Formyladenosine in Mammalian RNA. Nat. Commun. 4, 1798. 10.1038/ncomms2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuens T., Bouhy D., Timmerman V. (2016). The hnRNP Family: Insights into Their Role in Health and Disease. Hum. Genet. 135 (8), 851–867. 10.1007/s00439-016-1683-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geula S., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Dominissini D., Mansour A. A., Kol N., Salmon-Divon M., et al. (2015). m 6 A mRNA Methylation Facilitates Resolution of Naïve Pluripotency toward Differentiation. Science 347 (6225), 1002–1006. 10.1126/science.1261417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheller B. J., Blum J. E., Fong E. H. H., Malysheva O. V., Cosgrove B. D., Thalacker-Mercer A. E. (2020). A Defined N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) Profile Conferred by METTL3 Regulates Muscle Stem Cell/myoblast State Transitions. Cell Death Discov. 6, 95. 10.1038/s41420-020-00328-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Liu H., Yang T.-L., Li S. M., Li S. K., Tian Q., et al. (2011). The Fat Mass and Obesity Associated Gene, FTO, Is Also Associated with Osteoporosis Phenotypes. PLoS One 6 (11), e27312. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. J., Zhu Y., Ma H., Guo Y., Shi X., Liu Y., et al. (2017). Ythdc2 Is an N6-Methyladenosine Binding Protein that Regulates Mammalian Spermatogenesis. Cell Res 27 (9), 1115–1127. 10.1038/cr.2017.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Weng H., Sun W., Qin X., Shi H., Wu H., et al. (2018). Recognition of RNA N6-Methyladenosine by IGF2BP Proteins Enhances mRNA Stability and Translation. Nat. Cel Biol 20 (3), 285–295. 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. J., Bierma-Zeinstra S. (2019). Osteoarthritis. The Lancet 393 (10182), 1745–1759. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30417-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. J., Schofield D., Callander E. (2014). The Individual and Socioeconomic Impact of Osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10 (7), 437–441. 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegawa S. (2013). The Genetics of Common Degenerative Skeletal Disorders: Osteoarthritis and Degenerative Disc Disease. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 14, 245–256. 10.1146/annurev-genom-091212-153427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G., Fu Y., Zhao X., Dai Q., Zheng G., Yang Y., et al. (2011). N6-methyladenosine in Nuclear RNA Is a Major Substrate of the Obesity-Associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7 (12), 885–887. 10.1038/nchembio.687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C. B., Dagar M. (2020). Osteoporosis in Older Adults. Med. Clin. North America 104 (5), 873–884. 10.1016/j.mcna.2020.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasowitz S. D., Ma J., Anderson S. J., Leu N. A., Xu Y., Gregory B. D., et al. (2018). Nuclear m6A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates Alternative Polyadenylation and Splicing during Mouse Oocyte Development. Plos Genet. 14 (5), e1007412. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T. (2019). Regulation of Proliferation, Differentiation and Functions of Osteoblasts by Runx2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (7), 1694. 10.3390/ijms20071694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudou K., Komatsu T., Nogami J., Maehara K., Harada A., Saeki H., et al. (2017). The Requirement of Mettl3-Promoted MyoD mRNA Maintenance in Proliferative Myoblasts for Skeletal Muscle Differentiation. Open Biol. 7 (9), 170119. 10.1098/rsob.170119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Q., Liu P. Y., Haase J., Bell J. L., Hüttelmaier S., Liu T. (2019). The Critical Role of RNA m6A Methylation in Cancer. Cancer Res. 79 (7), 1285–1292. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-2965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson L., Degens H., Li M., Salviati L., Lee Y. i., Thompson W., et al. (2019). Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiol. Rev. 99 (1), 427–511. 10.1152/physrev.00061.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Cai L., Meng R., Feng Z., Xu Q. (2020). METTL3 Modulates Osteoclast Differentiation and Function by Controlling RNA Stability and Nuclear Export. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (5), 1660. 10.3390/ijms21051660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Rao B., Yang J., Liu L., Huang M., Liu X., et al. (2020). Dysregulated m6A-Related Regulators Are Associated with Tumor Metastasis and Poor Prognosis in Osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 10, 769. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Zhao X., Wang W., Shi H., Pan Q., Lu Z., et al. (2018). Ythdf2-mediated m6A mRNA Clearance Modulates Neural Development in Mice. Genome Biol. 19 (1), 69. 10.1186/s13059-018-1436-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Yang F., Gao M., Gong R., Jin M., Liu T., et al. (2019). miR-149-3p Regulates the Switch between Adipogenic and Osteogenic Differentiation of BMSCs by Targeting FTO. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 17, 590–600. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.06.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Liu Q., Zhao C., Gao X., Han W., Stefanik J. J., et al. (2020). High Prevalence of Patellofemoral Osteoarthritis in China: a Multi-center Population-Based Osteoarthritis Study. Clin. Rheumatol. 39 (12), 3615–3623. 10.1007/s10067-020-05110-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Wang P., Li J., Xie Z., Cen S., Li M., et al. (2021). The N6-Methyladenosine Demethylase ALKBH5 Negatively Regulates the Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells through PRMT6. Cell Death Dis 12 (6), 578. 10.1038/s41419-021-03869-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Han H., Xiong Q., Yang C., Wang L., Ma J., et al. (2021). METTL3-Mediated m6A Methylation Regulates Muscle Stem Cells and Muscle Regeneration by Notch Signaling Pathway. Stem Cell Int 2021, 9955691. 10.1155/2021/9955691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Dai Q., Zheng G., He C., Parisien M., Pan T. (2015). N6-methyladenosine-dependent RNA Structural Switches Regulate RNA-Protein Interactions. Nature 518 (7540), 560–564. 10.1038/nature14234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Zhou K. I., Parisien M., Dai Q., Diatchenko L., Pan T. (2017). N 6-methyladenosine Alters RNA Structure to Regulate Binding of a Low-Complexity Protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (10), 6051–6063. 10.1093/nar/gkx141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Li M., Jiang L., Jiang R., Fu B. (2019). METTL3 Promotes Experimental Osteoarthritis Development by Regulating Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis in Chondrocyte. Biochem. Biophysical Res. Commun. 516 (1), 22–27. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.05.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S., Tong L. (2014). Molecular Basis for the Recognition of Methylated Adenines in RNA by the Eukaryotic YTH Domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111 (38), 13834–13839. 10.1073/pnas.1412742111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y., Dong L., Liu X.-M., Guo J., Ma H., Shen B., et al. (2019). m6A in mRNA Coding Regions Promotes Translation via the RNA Helicase-Containing YTHDC2A in mRNA Coding Regions Promotes Translation via the RNA Helicase-Containing YTHDC2. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 5332. 10.1038/s41467-019-13317-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauer J., Luo X., Blanjoie A., Jiao X., Grozhik A. V., Patil D. P., et al. (2017). Reversible Methylation of m6Am in the 5′ Cap Controls mRNA Stability. Nature 541 (7637), 371–375. 10.1038/nature21022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo X. B., Zhang Y. H., Lei S. F. (2018). Genome-wide Identification of m6A-Associated SNPs as Potential Functional Variants for Bone mineral Density. Osteoporos. Int. 29 (9), 2029–2039. 10.1007/s00198-018-4573-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscaritoli M., Anker S. D., Argilés J., Aversa Z., Bauer J. M., Biolo G., et al. (2010). Consensus Definition of Sarcopenia, Cachexia and Pre-cachexia: Joint Document Elaborated by Special Interest Groups (SIG) "Cachexia-Anorexia in Chronic Wasting Diseases" and "nutrition in Geriatrics". Clin. Nutr. 29 (2), 154–159. 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W., Yao S., Zhou Y., Liu Y., Huang P., Zhou A., et al. (2019). Long Noncoding RNA GAS5 Inhibits Progression of Colorectal Cancer by Interacting with and Triggering YAP Phosphorylation and Degradation and Is Negatively Regulated by the m6A Reader YTHDF3. Mol. Cancer 18 (1), 143. 10.1186/s12943-019-1079-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panoutsopoulou K., Metrustry S., Doherty S. A., Laslett L. L., Maciewicz R. A., Hart D. J., et al. (2014). The Effect ofFTOvariation on Increased Osteoarthritis Risk Is Mediated through Body Mass index: a Mendelian Randomisation Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 73 (12), 2082–2086. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S., Xiao W., Ju D., Sun B., Hou N., Liu Q., et al. (2019). Identification of Entacapone as a Chemical Inhibitor of FTO Mediating Metabolic Regulation through FOXO1. Sci. Transl Med. 11 (488), 7116. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau7116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ping X.-L., Sun B.-F., Wang L., Xiao W., Yang X., Wang W.-J., et al. (2014). Mammalian WTAP Is a Regulatory Subunit of the RNA N6-Methyladenosine Methyltransferase. Cel Res 24 (2), 177–189. 10.1038/cr.2014.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadir A., Liang S., Wu Z., Chen Z., Hu L., Qian A. (2020). Senile Osteoporosis: The Involvement of Differentiation and Senescence of Bone Marrow Stromal Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (1), 10349. 10.3390/ijms21010349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qaseem A., Forciea M. A., McLean R. M., Denberg T. D. (2017). Treatment of Low Bone Density or Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures in Men and Women: A Clinical Practice Guideline Update from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 166 (11), 818–839. 10.7326/m15-1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L., Min S., Shu L., Pan H., Zhong J., Guo J., et al. (2020). Genetic Analysis of N6-Methyladenosine Modification Genes in Parkinson's Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 93, 143–e13. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel M., Köster T., Staiger D. (2019). Marking RNA: m6A Writers, Readers, and Functions in Arabidopsis. J. Mol. Cel Biol 11 (10), 899–910. 10.1093/jmcb/mjz085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg I. H. (1997). Sarcopenia: Origins and Clinical Relevance. J. Nutr. 127, 990S–991S. 10.1093/jn/127.5.990s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roundtree I. A. (2017). YTHDC1 Mediates Nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine Methylated mRNAs. Elife 6, e31311. 10.7554/elife.31311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin K. H., Friis-Holmberg T., Hermann A. P., Abrahamsen B., Brixen K. (2013). Risk Assessment Tools to Identify Women with Increased Risk of Osteoporotic Fracture: Complexity or Simplicity? A Systematic Review. J. Bone Miner Res. 28 (8), 1701–1717. 10.1002/jbmr.1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachse G., Church C., Stewart M., Cater H., Teboul L., Cox R. D., et al. (2018). FTO Demethylase Activity Is Essential for normal Bone Growth and Bone Mineralization in Mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (Bba) - Mol. Basis Dis. 1864 (3), 843–850. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safiri S., Kolahi A. A., Smith E., Hill C., Bettampadi D., Mansournia M. A., et al. (2020). Global, Regional and National burden of Osteoarthritis 1990-2017: a Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79 (6), 819–828. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang W., Xue S., Jiang Y., Lu H., Zhu L., Wang C., et al. (2021). METTL3 Involves the Progression of Osteoarthritis Probably by Affecting ECM Degradation and Regulating the Inflammatory Response. Life Sci. 278, 119528. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma L. (2021). Osteoarthritis of the Knee. N. Engl. J. Med. 384 (1), 51–59. 10.1056/nejmcp1903768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G.-S., Zhou H.-B., Zhang H., Chen B., Liu Z.-P., Yuan Y., et al. (2018). The GDF11-FTO-Pparγ axis Controls the Shift of Osteoporotic MSC Fate to Adipocyte and Inhibits Bone Formation during Osteoporosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (Bba) - Mol. Basis Dis. 1864 (12), 3644–3654. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Chai P., Jia R., Fan X. (2020). Novel Insight into the Regulatory Roles of Diverse RNA Modifications: Re-defining the Bridge between Transcription and Translation. Mol. Cancer 19 (1), 78. 10.1186/s12943-020-01194-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Wei J., He C. (2019). Where, when, and How: Context-dependent Functions of RNA Methylation Writers, Readers, and Erasers. Mol. Cel 74 (4), 640–650. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorci M., Ianniello Z., Cruciani S., Larivera S., Ginistrelli L. C., Capuano E., et al. (2018). METTL3 Regulates WTAP Protein Homeostasis. Cel Death Dis 9 (8), 796. 10.1038/s41419-018-0843-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Wang H., Wang Y., Yuan G., Yu X., Jiang H., et al. (2021). MiR-103-3p Targets the M6 A Methyltransferase METTL14 to Inhibit Osteoblastic Bone Formation. Aging Cell 20 (2), e13298. 10.1111/acel.13298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabebordbar M., Wang E. T., Wagers A. J. (2013). Skeletal Muscle Degenerative Diseases and Strategies for Therapeutic Muscle Repair. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 8, 441–475. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X., Wang S., Zhan S., Niu J., Tao K., Zhang Y., et al. (2016). The Prevalence of Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis in China: Results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 68 (3), 648–653. 10.1002/art.39465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian C., Huang Y., Li Q., Feng Z., Xu Q. (2019). Mettl3 Regulates Osteogenic Differentiation and Alternative Splicing of Vegfa in Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (3), 551. 10.3390/ijms20030551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu C., He J., Chen R., Li Z. (2019). The Emerging Role of Exosomal Non-coding RNAs in Musculoskeletal Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 25 (42), 4523–4535. 10.2174/1381612825666191113104946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Cai F., Shi R., Wang X.-H., Wu X.-T. (2016). Aging and Age Related Stresses: a Senescence Mechanism of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 24 (3), 398–408. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.-F., Kuang M.-j., Han S.-j., Wang A.-b., Qiu J., Wang F., et al. (2020). BMP2 Modified by the m6A Demethylation Enzyme ALKBH5 in the Ossification of the Ligamentum Flavum through the AKT Signaling Pathway. Calcif Tissue Int. 106 (5), 486–493. 10.1007/s00223-019-00654-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Doxtader K. A., Nam Y. (2016). Structural Basis for Cooperative Function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 Methyltransferases. Mol. Cel 63 (2), 306–317. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Feng J., Xue Y., Guan Z., Zhang D., Liu Z., et al. (2016). Structural Basis of N6-Adenosine Methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 Complex. Nature 534 (7608), 575–578. 10.1038/nature18298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Huang N., Yang M., Wei D., Tai H., Han X., et al. (2017). FTO Is Required for Myogenesis by Positively Regulating mTOR-PGC-1α Pathway-Mediated Mitochondria Biogenesis. Cel Death Dis 8 (3), e2702. 10.1038/cddis.2017.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., Lu Z., Han D., Ma H., et al. (2015). N6-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 161 (6), 1388–1399. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Che M., Xin J., Zheng Z., Li J., Zhang S. (2020). The Role of IL-1β and TNF-α in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Biomed. Pharmacother. 131, 110660. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chu M., Rong J., Xing B., Zhu L., Zhao Y., et al. (2016). No Association of the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Rs8044769 in the Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Gene with Knee Osteoarthritis Risk and Body Mass index. Bone Jt. Res. 5 (5), 169–174. 10.1302/2046-3758.55.2000589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C.-M., Moss B. (1977). Nucleotide Sequences at the N6-Methyladenosine Sites of HeLa Cell Messenger Ribonucleic Acid. Biochemistry 16 (8), 1672–1676. 10.1021/bi00627a023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C. M., Gershowitz A., Moss B. (1976). 5'-Terminal and Internal Methylated Nucleotide Sequences in HeLa Cell mRNA. Biochemistry 15 (2), 397–401. 10.1021/bi00647a024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Liu F., Lu Z., Fei Q., Ai Y., He P. C., et al. (2018). Differential m6A, m6Am, and m1A Demethylation Mediated by FTO in the Cell Nucleus and Cytoplasm. Mol. Cel 71 (6), 973–985. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnen A. J., Westendorf J. J. (2019). Epigenetics as a New Frontier in Orthopedic Regenerative Medicine and Oncology. J. Orthop. Res. 37 (7), 1465–1474. 10.1002/jor.24305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W., Feng J., Jiang D., Zhou X., Jiang Q., Cai M., et al. (2017). AMPK Regulates Lipid Accumulation in Skeletal Muscle Cells through FTO-dependent Demethylation of N6-Methyladenosine. Sci. Rep. 7, 41606. 10.1038/srep41606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Xie L., Wang M., Xiong Q., Guo Y., Liang Y., et al. (2018). Mettl3-mediated m6A RNA Methylation Regulates the Fate of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Osteoporosis. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 4772. 10.1038/s41467-018-06898-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Zhao Q., Hu B., Wang J., Liu C., Xu H. (2020). METTL3 Promotes IL‐1β-induced Degeneration of Endplate Chondrocytes by Driving m6A‐dependent Maturation of miR‐126‐5p. J. Cel. Mol. Med. 24 (23), 14013–14025. 10.1111/jcmm.16012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W. q., He M., Yu D. j., Wu Y. x., Wang X. h., Lv S., et al. (2021). Mouse Models of Sarcopenia: Classification and Evaluation. J. Cachexia, Sarcopenia Muscle 12 (3), 538–554. 10.1002/jcsm.12709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Wang X., Liu K., Roundtree I. A., Tempel W., Li Y., et al. (2014). Structural Basis for Selective Binding of m6A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH Domain. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10 (11), 927–929. 10.1038/nchembio.1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan G., Yuan Y., He M., Gong R., Lei H., Zhou H., et al. (2020). m6A Methylation of Precursor-miR-320/runx2 Controls Osteogenic Potential of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem CellsA Methylation of Precursor-miR-320/runx2 Controls Osteogenic Potential of Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 19, 421–436. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Bi Z., Wu R., Zhao Y., Liu Y., Liu Q., et al. (2019). METTL3 Inhibits BMSC Adipogenic Differentiation by Targeting the JAK1/STAT5/C/EBPβ Pathway via an M 6 A‐YTHDF2-dependent Manner. FASEB j. 33 (6), 7529–7544. 10.1096/fj.201802644r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung S. S. Y., Reijnierse E. M., Pham V. K., Trappenburg M. C., Lim W. K., Meskers C. G. M., et al. (2019). Sarcopenia and its Association with Falls and Fractures in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. J. Cachexia, Sarcopenia Muscle 10 (3), 485–500. 10.1002/jcsm.12411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Yang X., Tang J., Si S., Zhou Z., Lu J., et al. (2021). ALKBH5 Inhibited Cell Proliferation and Sensitized Bladder Cancer Cells to Cisplatin by m6A-Ck2α-Mediated Glycolysis. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 23, 27–41. 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.10.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X., Shi L., Guo Y., Sun J., Miao J., Shi J., et al. (2021). METTL3 Regulates Ossification of the Posterior Longitudinal Ligament via the lncRNA XIST/miR-302a-3p/USP8 Axis. Front. Cel Dev. Biol. 9, 629895. 10.3389/fcell.2021.629895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y., Liu J., Cui X., Cao J., Luo G., Zhang Z., et al. (2018). VIRMA Mediates Preferential m6A mRNA Methylation in 3′UTR and Near Stop Codon and Associates with Alternative Polyadenylation. Cell Discov 4, 10. 10.1038/s41421-018-0019-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q., Li N., Wang Q., Feng J., Sun D., Zhang Q., et al. (2019). The Prevalence of Osteoporosis in China, a Nationwide, Multicenter DXA Survey. J. Bone Miner Res. 34 (10), 1789–1797. 10.1002/jbmr.3757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Wang Y., Peng Y., Xu H., Zhou X. (2020). METTL3 Regulates Inflammatory Pain by Modulating M 6 A‐dependent pri‐miR‐365‐3p Processing. FASEB j. 34 (1), 122–132. 10.1096/fj.201901555r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Riddle R. C., Yang Q., Rosen C. R., Guttridge D. C., Dirckx N., et al. (2019). The RNA Demethylase FTO Is Required for Maintenance of Bone Mass and Functions to Protect Osteoblasts from Genotoxic Damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116 (36), 17980–17989. 10.1073/pnas.1905489116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Wang Y., Zhao H., Han X., Zhao T., Qu P., et al. (2020). Extracellular Vesicle-Encapsulated miR-22-3p from Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation via FTO Inhibition. Stem Cel Res Ther 11 (1), 227. 10.1186/s13287-020-01707-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B. S., Roundtree I. A., He C. (2017). Post-transcriptional Gene Regulation by mRNA Modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cel Biol 18 (1), 31–42. 10.1038/nrm.2016.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Yang Y., Sun B.-F., Shi Y., Yang X., Xiao W., et al. (2014). FTO-dependent Demethylation of N6-Methyladenosine Regulates mRNA Splicing and Is Required for Adipogenesis. Cel Res 24 (12), 1403–1419. 10.1038/cr.2014.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G., Dahl J. A., Niu Y., Fedorcsak P., Huang C.-M., Li C. J., et al. (2013). ALKBH5 Is a Mammalian RNA Demethylase that Impacts RNA Metabolism and Mouse Fertility. Mol. Cel 49 (1), 18–29. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou K. I., Shi H., Lyu R., Wylder A. C., Matuszek Ż., Pan J. N., et al. (2019). Regulation of Co-transcriptional Pre-mRNA Splicing by m6A through the Low-Complexity Protein hnRNPG. Mol. Cel 76 (1), 70–81. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Sun B., Zhu L., Zou G., Shen Q. (2021). N6-Methyladenosine Induced miR-34a-5p Promotes TNF-α-Induced Nucleus Pulposus Cell Senescence by Targeting SIRT1. Front. Cel Dev. Biol. 9, 642437. 10.3389/fcell.2021.642437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Roundtree I. A., Wang P., Wang X., Wang L., Sun C., et al. (2014). Crystal Structure of the YTH Domain of YTHDF2 Reveals Mechanism for Recognition of N6-Methyladenosine. Cel Res 24 (12), 1493–1496. 10.1038/cr.2014.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong X., Zhao J., Wang H., Lu Z., Wang F., Du H., et al. (2019). Mettl3 Deficiency Sustains Long-Chain Fatty Acid Absorption through Suppressing Traf6-dependent Inflammation Response. J.Immunol. 202 (2), 567–578. 10.4049/jimmunol.1801151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]