Abstract

Background

Social isolation has been one of the main strategies to prevent the spread of Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). However, the impact of social isolation on the lifestyle of patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) and claudication symptoms remains unclear.

Objectives

To analyze the perceptions of patients with PAD of the impact of social isolation provoked by COVID-19 pandemic on health lifestyle.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

The database of studies developed by our group involving patients with PAD from public hospitals in São Paulo.

Methods

In this cross-sectional survey study, 136 patients with PAD (61% men, 68 ± 9 years old, 0.55 ± 0.17 ankle-brachial index, 82.4% with a PAD diagnosis ≥5 years old) were included. Health lifestyle factors were assessed through a telephone interview using a questionnaire containing questions related to: (a) COVID-19 personal care; (b) mental health; (c) health risk habits; (d) eating behavior; (e) lifestyle; (f) physical activity; (g) overall health; and (h) peripheral artery disease health care.

Results

The majority of patients self-reported spending more time watching TV and sitting during the COVID-19 pandemic and only 28.7% were practicing physical exercise. Anxiety and unhappiness were the most prevalent feelings self-reported among patients and 43.4% reported a decline in walking capacity.

Conclusion

Most patients with PAD self-reported increased sedentary behavior, lower physical activity level, and worse physical and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, it is necessary to adopt strategies to improve the quality of life of these patients during this period.

Introduction

Patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) and claudication symptoms present walking impairment1 and several cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The first line therapy for these patients includes stimulus to physical activity practice, improvements in healthy eating, the treatment of comorbid conditions, such as. hypertension, cardiac disease and more recently, management of mental health.6 , 7

In December 2019, a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) called Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) was first identified in the city of Wuhan, China and subsequently declared a global pandemic, with more than 200.174.880 cases and 4.255.890 deaths registered worldwide by August 5, 2021.8 Social isolation has been one of the main strategies used to prevent the spread of COVID-19, however, this strategy has resulted in unintended negative consequences on the lifestyle of the population.9, 10 Amnar et al., through an international online survey involving people from different continents, observed a reduction in physical activity level, an increase in daily sitting time, and unhealthy eating habits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hossain et al. in a review study also observed worsening mental health of the population due to social isolation. Whether similar results occur in patients with PAD, who frequently report low physical activity level, poor eating habits, and mental health, is unclear. Thus, the current study investigated the perceptions of patients with PAD and the impact of COVID-19 on health lifestyle. The hypothesis of the study was that social isolation negatively affects lifestyle, aggravating the physical and mental health, and unhealthy eating habits of these patients.

Material and methods

Study design and patients

This observational, descriptive, cross-sectional survey study, included patients with PAD and claudication symptoms (i.e. residents of metropolitan cities) recruited from the database of studies developed and published before the COVID-19 pandemic by our group.1 , 3, 4, 5 , 11, 12, 13 This study was approved by the Universidade Nove de Julho’ Ethics Committee before data collection (CAAE #31529220.8.0000.5511). All participants verbally gave informed consent by phone prior to participation. Participants did not identify themselves and their answers were only included in the sample if they gave authorization before the protocol started. All procedures follow the national legislation and Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (a) agreed to participate and respond to all questions of the survey; (b) previous diagnosis of PAD; (c) age > 45 years old; (d) had ankle-brachial index (ABI) ≤ 0.90 in one or both legs, and; (e) absence of non-compressible vessels, amputated limbs and/or ulcers. Patients were only excluded if: (a) presented disabilities such as cognitive, hearing, or speech during phone call that compromises the answer to the questionnaire.

Data collection

Social isolation in São Paulo was recommended on March 16, 2020 with quarantine, and non-essential services closed on March 24, 2020. Data collection was performed through a phone interview, between May 15, 2020 and August 22, 2020. The evaluation of the impact of COVID-19 on health lifestyle was assessed through a questionnaire developed by the researchers of the study, based on questionnaires and previous studies.11, 12, 13, 14, 15

The questionnaire was composed of questions divided into 8 domains: (a) COVID-19 personal care; (b) mental health; (c) health risk habits; (d) eating behavior; (e) lifestyle; (f) physical activity; (g) overall health; and (h) peripheral artery disease health care. The questions used in the present analysis are presented below.

Personal information was accessed from our database including information on sex (“female” or “male”), date of birth (DD/MM/YYYY), time of PAD diagnosis (in years), and PAD severity (ankle-brachial index).

Covid-19 personal care: involved questions on the recommendations for personal care during the Covid-19 pandemic. The patient was required to report all that were applicable from the possible answers: “washing hands”, “alcohol gel”, “avoid leaving home (shelter in place)”, “avoid crowds”, “avoid other family members (outside household)”, “avoid shaking hands”, “avoid eating out”, and “social isolation”. In order to gain direct information about a COVID-19 diagnosis, patients were asked: 1 – Have you had contact with someone who was diagnosed with COVID-19?, 2 – Have you been diagnosed with COVID-19? If yes, 3 – Have you recovered? Answers to all questions were “Yes” or “No”.

Mental health: This domain is composed of 3-self-reported items aiming to identify frequent feelings related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The following questions were used: 1 – Due to the COVID-19, are you feeling more anxious?; 2 – Due to the COVID-19, are you feeling overwhelmingly unhappy?; 3 - Due to the COVID-19, are you feeling more stressed?; 4- Due to the COVID-19, are you feeling depressed? Answers to all questions were “Yes” or “No”.

Health risk behavior: This domain aimed to identify frequent social habits. The selected questions were as follows: 1 – Do you smoke?; 2 – Due to social isolation, do you spend more time sitting?; 3 – With the COVID-19 pandemic, do you feel that your television use has increased? Answers to all items were “No”, or “Yes”.

Eating behavior: To explore the possible impacts of COVID-19 on the frequent eating habits, the following questions were asked: 1 – Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, are your eating habits: “unchanged”, “worsened” or “improved”?; 2 –Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, do you feel that your fruit intake has increased?; 3 – Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, do you feel that your intake of sweets has increased? 4 – Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, do you feel that your intake of vegetables has increased? 5 – Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, do you feel that your fried food intake has increased? Possible answers to questions 2 to 5 of this topic were “No”, or “Yes”.

Physical activity: In order to assess frequent physical activity habits, participants were asked the following questions: 1-Did you regularly practice physical activity before the COVID-19 pandemic?; 2- Have you been practicing physical activity regularly, at least once a week, during the COVID-19 pandemic?; 3 – How many times do you exercise a week at the moment?; 4 –Do you usually exercise less than 30 min, between 30 and 60 min or more than 60 min?; 5 –What type of exercise do you do?

Overall health: From the list of diseases, the participant is required to report the presence of all diagnosed diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol, high triglycerides, cardiopathy, or other.

Peripheral artery disease health care: from this domain patients were asked: “Do you feel that your ability to walk has decreased in recent weeks?” Possible answers were “yes” or “no”.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analysis were performed using the software SPSS (version 20). The data are presented as mean and standard deviations for continuous variables and relative frequencies for categorical variables.

Results

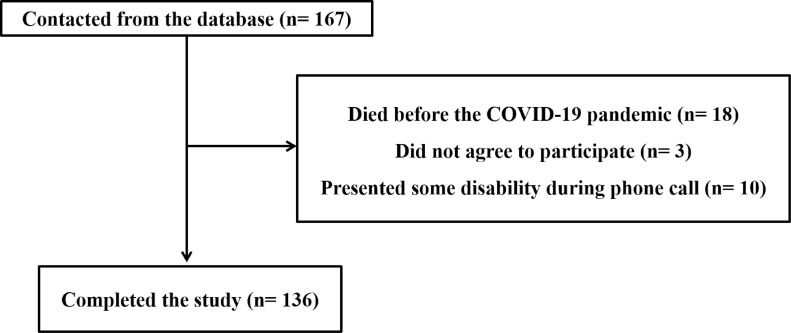

A flowchart of the study is provided in Fig. 1 . One hundred and sixty-seven patients were contacted. Of these, 18 patients died before the COVID-19 pandemic, 3 did not agree to participate, and 10 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, 136 patients with PAD and claudication symptoms (61% men, 68 ± 9 years old, 0.55 ± 0.17 ankle-brachial index, 82.4% had the PAD diagnosis ≥5 years old) participated in the study. Of these, two patients had been diagnosed with and recovered from COVID-19. The majority of patients followed preventive attitudes to avoid COVID-19 contagion, such as social isolation (88.2%) and hand sanitization (98.5%) (Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Participants’ flowchart.

Table 1.

Factors related with COVID-19 in patients with peripheral artery disease.

| N = 136 | |

|---|---|

| Variables, n (% yes) | |

| COVID-19 diagnosis | 2 (1.5) |

| Recovered COVID-19* | 2 (100) |

| Preventive attitudes | |

| Social isolation | 120 (88.2) |

| Hands sanitization | 134 (98.5) |

| Avoid leaving home | 114 (83.8) |

| Avoid contact people | 132 (97.1) |

| Contact with people diagnosed with COVID-19 | 7 (5.1) |

| Comorbid conditions | |

| Smoking | 21 (15.4) |

| Ex-smoker | 84 (61.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 61 (44.9) |

| Hypertension | 114 (83.8) |

| Dyslipidemia | 105 (77.2) |

| Respiratory disease | 22 (16.2) |

Data presented as absolute and relative frequency

n = 2.

Table 2 shows the sedentary and physical activity habits of patients with PAD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most patients self-reported spending more time watching TV and sitting, 58.8% and 76.5%, respectively. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 54.4% of patients were physically active, decreasing to 28.7% during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

Impact of COVID-19 on sedentary and physical activity habits in patients with peripheral artery disease (n = 136).

| Patients with peripheral artery disease | |

|---|---|

| Variables, n (% yes) | |

| Sedentary habits (n=136) | |

| Spend more time watching TV | 80 (58.8) |

| Spend more time sitting | 104 (76.5) |

| Physical activity habits (n = 136) | |

| Physical exercise before COVID-19 | 74 (54.4) |

| Physical exercise currently | 39 (28.7) |

| Modalities (n = 39) | |

| Aerobic exercise | 24 (61.5) |

| Functional exercise | 14 (35.9) |

| Frequency (n = 39) | |

| 1–2 x/week | 8 (20.5) |

| 3–4 x/week | 11 (28.2) |

| 5–7 x/week | 20 (51.3) |

| Duration (n = 39) | |

| ≤ 30 min | 10 (25.6) |

| 31–60 min | 23 (59.0) |

| ≥ 61 min | 6 (15.4) |

Data presented as absolute and relative frequency.

Table 3 shows the eating habits, physical and mental health of patients with PAD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Approximately, seventy-nine percent of patients had not modified their eating habits and only 10.3% reported worsened eating habits. In addition, approximately, forty-three percent of patients reported a reduction in walking capacity, anxiety, and unhappiness had increased in more than 30.1% of patients.

Table 3.

Impact of COVID-19 on eating habits and physical and mental health in patients with peripheral artery disease.

| N = 136 | |

|---|---|

| Variables, n (% yes) | |

| Eating habits | |

| healthier | 15 (11.0) |

| equal | 107 (78.7) |

| less healthy | 14 (10.3) |

| Increase in consumption of fried foods | 14 (10.3) |

| Increase in consumption of sweets | 24 (17.6) |

| Increase in consumption of fruits | 46 (33.8) |

| Increase in consumption of vegetables/legumes | 33 (24.3) |

| Physical health | |

| Decline in walking capacity | 59 (43.4) |

| Mental health | |

| More anxious | 69 (50.7) |

| Unhappier | 41 (30.1) |

| More stressed | 34 (25.0) |

| More depressed | 27 (19.9) |

Data presented as absolute and relative frequency.

Discussion

This study revealed the majority of patients self report spending more time watching TV and sitting during the COVID-19 pandemic, with only 28.7% physically exercising. In addition, thirty percent of patient reported the most prevalent self reported feeling of anxiety, unhappiness, and noted decline in walking capacity.

The majority of the patients presented with different co-morbidities, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes. The study results corroborate with other studies1, 2, 3, 4, 5 that also demonstrated a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with PAD, classifying them as a risk group for COVID-19.16 Jin et al. state the number of co-morbidities has been associated with higher severity and mortality among patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis. Among our sample, two patients had been diagnosed with and recovered from COVID-19. This result is interesting because São Paulo had the highest number of cases and deaths of all cities in Brazil.17 The low number of cases of COVID-19 among our sample may be related to their high adherence to preventive measures. Most of our patients were in social isolation (88.2%), avoiding contact with other people (97.1%) or leaving their homes (83.8%), and using hygienic strategies, such as hand sanitization (98.5%). These precautions suggest that preventive attitudes could be useful to avoid contagion in this group.

In accordance with other studies performed with subjects without PAD,18 , 19 patients self-reported spending more time watching TV and sitting compared with the period before COVID-19. This is alarming for these patients who already presented high sedentary behavior13and also, especially, among the patients with a higher body mass index and lower walking capacity.12 A small number of patients with PAD also self-reported (28.7%) the continuation of regular physical exercise practice. Recent studies9 , 20 , 21 also observed a negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity level of the population in different countries. Studies 3 , 22 performed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that the majority of PAD patients were physically inactive. This result corroborates the impairment in walking capacity reported by 43.4% of patients compared with before COVID-19. Lower walking capacity has been associated with worse prognosis in this population.23 , 24 Thus, exacerbation of these harmful behaviors due to social isolation has aggravated the worsening in health of these patients.

Many patients reported being more anxious, unhappy, stressed, and depressed than before the pandemic, which is particularly worrying since studies before the COVID-19 pandemic showed that patients with PAD already presented deleterious alterations in mental health compared to subjects without PAD.25 , 26 Factors such as social distancing from family and friends, for being included in a main risk group, and also reduced physical activity level might have contributed to these factors. Future studies should investigate the factors associated with mental health during social isolation in patients with PAD.

Since physical activity, management of cardiovascular risk factors, and mental health are the cornerstones of clinical treatment of PAD, these results could be useful for health authorities to develop future strategies to avoid the clinical impairment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in PAD. In this context, our data support the importance of studies analyzing the feasibility and health effects of behavior change programs using telemedicine consultations to improve overall health (sedentary time, physical and mental health, healthy eating habits, and physical activity), unsupervised home-based exercise programs, and tele-rehabilitation programs.

Limitations

The questionnaire used in this study was a non validated questionnaire developed by our group, based on questionnaires and previous studies.11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Despite the group has experience in research with PAD, the use of non validated questionnaire has less methodological rigor and is also more susceptible to information bias. The PAD severity was not assessed due to the social isolation adopted to contain of COVID-19, however, as all patients were recruited from a previously compiled database. We can attest all of them have a confirmed PAD diagnosis. In addition, a group of individuals without PAD was not included in this study.

Conclusion

Most patients with PAD self-reported increased sedentary behavior, lower physical activity level, and worse physical and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavior change programs involving nutritional, psychological, physical activity monitoring among others in order to improve quality of life these patients should be adopted to counteract the consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on lifestyle.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding

RR and NW receive a research productivity fellowship granted by Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development.

References

- 1.Farah B.Q., Barbosa J.P.S., Cucato G.G., et al. Predictors of walking capacity in peripheral arterial disease patients. Clinics. 2013;68:537–541. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(04)16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brevetti G., Oliva G., Di Giacomo S., Bucur R., Annecchini R., Di Iorio A. Intermittent claudication in older patients: risk factors, cardiovascular comorbidity, and severity of peripheral arterial disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1261–1262. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerage A.M., Correia M.A., Oliveira P.M.L., et al. Physical activity levels in peripheral artery disease patients. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;113:410–416. doi: 10.5935/abc.20190142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalcante B.R., Germano-Soares A.H., Gerage A.M., et al. Association between physical activity and walking capacity with cognitive function in peripheral artery disease patients. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:672–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanegusuku H., Cucato G.G., Domiciano R.M., Longano P., Puech-Leao P., Wolosker N., et al. Impact of obesity on walking capacity and cardiovascular parameters in patients with peripheral artery disease: a cross-sectional study. J Vasc Nurs. 2020;38:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aboyans V., Ricco J.B., Bartelink M.E.L., et al. ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS): document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteriesEndorsed by: the European Stroke Organization (ESO). The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Eur Heart J. 2017;39:763–816. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx095. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norgren L., Hiatt W.R., Dormandy J.A., Nehler M.R., Harris K.A., Fowkes F.G. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II) J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:S5–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. Suppl S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (Accessed August 5, 2021).

- 9.Ammar A., Brach M., Trabelsi K., et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hossain M.M., Sultana A., Purohit N. Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: a systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. Epidemiol Health. 2020;42:e2020038. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2020038. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cucato G.G., Correia M.A., Farah B.Q., Saes G.F., Lima A.H.A., Ritti-Dias R.M., et al. Validation of a Brazilian Portuguese version of the walking estimated-limitation calculated by history (WELCH) Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106(1):49–55. doi: 10.5935/abc.20160004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farah B.Q., Ritti-Dias R.M., Cucato G.G., Montgomery P.S., Gardner A.W. Factors associated with sedentary behavior in patients with intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;52:809–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2016.07.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farah B.Q., Ritti-Dias R.M., Montgomery P.S., Casanegra A.I., Silva-Palacios F., Gardner A.W. Sedentary behavior is associated with impaired biomarkers in claudicants. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63:657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser M.J., Bauer J.M., Ramsch C., et al. Validation of the mini nutritional assessment short-form (MNA®-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:782–788. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The WHOQOL Group The World Health Organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403–1409. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin J.M., Bai P., He W., et al. Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: focus on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. 2020;8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.COVID-19. Painel coronavírus. https://covid.saude.gov.br (assessed 12 May 2021).

- 18.Cheval B., Sivaramakrishnan H., Maltagliati S., et al. Relationships between changes in self-reported physical activity, sedentary behaviour and health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in France and Switzerland. J Sports Sci. 2021;9:699–704. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2020.1841396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luciano F., Cenacchi V., Vegro V., Pavei G. COVID-19 lockdown: physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep in Italian medicine students. Eur J Sport Sci. 2021;21(10):1459–1468. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2020.1842910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caputo E.L., Reichert F.F. Studies of physical activity and COVID-19 During the pandemic: a scoping review. J Phys Act Health. 2020;17:1275–1284. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2020-0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tison G.H., Avram R., Kuhar P., Abreau S., Marcus G.M., Pletcher M.J., et al. Worldwide effect of COVID-19 on physical activity: a descriptive study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:767–770. doi: 10.7326/M20-2665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heikkila K., Coughlin P.A., Pentti J., Kivimaki M., Halonen J.I. Physical activity and peripheral artery disease: two prospective cohort studies and a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2019;286:114–120. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gengo e Silva Rde C., de Melo V.F., Wolosker N., Consolim-Colombo F.M. Lower functional capacity is associated with higher cardiovascular risk in Brazilian patients with intermittent claudication. J Vasc Nurs. 2015;33:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nead K.T., Zhou M., Caceres R.D., et al. Walking impairment questionnaire improves mortality risk prediction models in a high-risk cohort independent of peripheral arterial disease status. Cir Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:255–261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas M., Patel K.K., Gosch K., et al. Mental health concerns in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease: insights from the PORTRAIT registry. J Psychosom Res. 2020;131:109963. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.109963. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sliwka A., Furgal M., Maga P., et al. The role of psychopathology in perceiving, reporting and treating intermittent claudication: a systematic review. Int Angiol. 2018;37:335–345. doi: 10.23736/S0392-9590.18.03948-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]