Abstract

Background

Because the etiologies of bronchiectasis and related diseases vary significantly among different regions and ethnicities, this study aimed to develop a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis in South Korea.

Methods

A modified Delphi method was used to develop expert consensus statements on a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis in South Korea. Initial statements proposed by a core panel, based on international bronchiectasis guidelines, were discussed in an online meeting and two email surveys by a panel of experts (≥70% agreement).

Results

The study involved 21 expert participants, and 30 statements regarding a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis were classified as recommended, conditional, or not recommended. The consensus statements of the expert panel were as follows: A standardized diagnostic bundle is useful in clinical practice; diagnostic tests for specific diseases, including immunodeficiency and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, are necessary when clinically suspected; initial diagnostic tests, including sputum microbiology and spirometry, are essential in all patients with bronchiectasis, and patients suspected with rare causes such as primary ciliary dyskinesia should be referred to specialized centers.

Conclusion

Based on this Delphi survey, expert consensus statements were generated including specific diagnostic, laboratory, microbiological, and pulmonary function tests required to manage patients with bronchiectasis in South Korea.

Keywords: Bronchiectasis, Diagnosis, Consensus Guideline, Korea, Survey

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by abnormal dilatation of the bronchi, with clinical manifestations of cough, sputum, and recurrent infection [1,2]. The prevalence and disease burden of bronchiectasis has increased worldwide [3-6], including South Korea [1,7-9]. One of the obstacles to adequately addressing the disease burden of bronchiectasis is its heterogeneity [10,11], as it may be caused by or related to various respiratory or systemic diseases [12,13].

Given the heterogeneity of the disease, a systematic etiologic evaluation is recommended by various international bronchiectasis guidelines [14,15]. Determining the etiology is of paramount importance in order to prescribe appropriate treatment and improve patients’ outcomes [16,17]. The international bronchiectasis guidelines, which suggest a minimum diagnostic bundle as part of the systematic approach, play a crucial role in the management of patients with bronchiectasis [15]. However, there are significant differences in the etiology and comorbidities of bronchiectasis among different countries and regions [10].

It may be inappropriate to apply the diagnostic bundles suggested by other international societies without modification for the management of patients with bronchiectasis in South Korea. This study developed a diagnostic bundle for patients with bronchiectasis in South Korea.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design

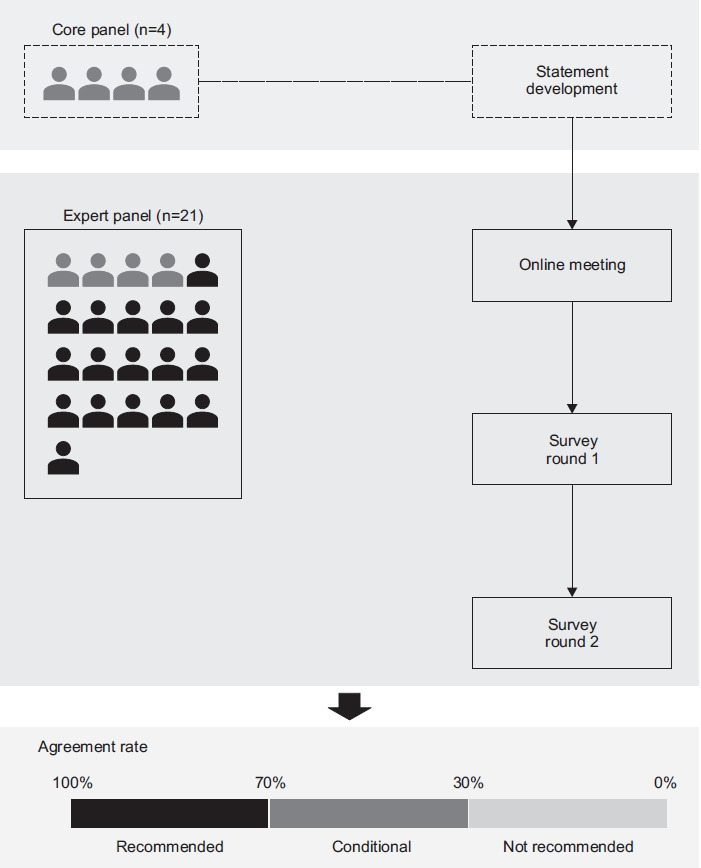

This study incorporated a two-step, modified Delphi method [18] focusing on developing a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis in South Korea. The Delphi method is recommended for use in the healthcare setting as a reliable means of determining consensus for a defined clinical problem [19,20]. Initially, a comprehensive list of items was identified, and a set of statements was proposed by four core panelists (HC, HL, SWR, and YMO) based on recently published international guidelines for bronchiectasis [14,15]. The draft document containing the list of statements was circulated by email to all panel members. Subsequently, an online meeting (March 8, 2021) attended by an expert panel (see below) was held before initiation of two rounds of Delphi surveys. During the process, a set of statements was modified and updated based on the expert panel’s feedback (Figure 1). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (application no. 2021-0218). All 21 participants provided informed consent and received written information about the study.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of a modified Delphi method.

2. Panel selection

Panel members were selected from study groups of the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases, the official Korean society of respiratory physicians, based on their clinical and research expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of bronchiectasis. Twenty-one experts were initially contacted and asked to participate in consensus development. Among the 21 expert panels, 20 experts were selected from three study groups of the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases: 16 from the Bronchiectasis Study Group (four of the 16 were the core panel members), two from the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Study Group, and two from the Tuberculosis Study Group. Additionally, one pediatrician, who is an expert in the field of primary ciliary dyskinesia, was also included in the expert panel. The other pediatrician, who is an expert in the field of primary immunodeficiency, served as a consultant (not as a panelist) during the study period. All 21 experts provided consent and agreed to participate. Of the 21 experts, 20 responded to both rounds of the survey.

3. Survey round 1

A document containing a set of statements was circulated by email to all experts. The document had five sections and 30 statements. Panel members selected one of the following answers to each statement: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree.

The agreement rate was defined as the percentage of panel members who answered, “strongly agree” or “agree.” The disagreement rate was defined as the percentage of panel members who answered “disagree” or “strongly disagree.” Additionally, towards the end of document, there was a questionnaire regarding the optimal cutoff for an agreement rate to recommend a particular diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis (Table 1). Panel members also had an option to write their suggestions and feedback in free text form in the document.

Table 1.

Survey round 1: questions and agreement/disagreement rates

| Choose one of the answers to each statement (Strongly agree/Agree/Neutral/Disagree/Strongly disagree) | Agreement/Neutral/Disagreement rates (%)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1. Overview | |||

| Q1 | A standardized diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis is useful in clinical practice. | 95/5/0 | |

| Q2 | In patients <50 years of age without a definite cause of bronchiectasis, additional tests should be performed to elucidate the etiology. Additional testing for primary ciliary dyskinesia, cystic fibrosis, alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency, and immunoglobulin deficiency may be performed. | 80/15/5 | |

| Section 2. Tests to search for the causes of bronchiectasis | |||

| Q3 | All patients should receive a chest CT when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 95/5/0 | |

| Q4 | All patients should receive tests related to ABPA such as CBC, total Ig E, specific Ig E, or skin test for Aspergillus fumigatus. | 35/25/40 | |

| Q5 | Tests related to ABPA should be performed only in patients with bronchiectasis carrying a history of asthma. | 60/5/35 | |

| Q6 | Serum Ig levels (Ig G, Ig A, and Ig M) should be measured in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 40/30/30 | |

| Q7 | Serum Ig levels (B cell immunity) should be measured only when immunodeficiency (e.g., recurrent infections) is suspected. | 60/10/30 | |

| Q8 | A baseline level of antibody specific to Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be measured in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 20/20/60 | |

| Q9 | If the baseline level of specific antibody to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides is low, it should be remeasured 4–8 weeks after pneumococcal 23 polyvalent vaccine injection. | 30/35/35 | |

| Q10 | A baseline level of antibody specific to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be measured only when immunodeficiency is suspected. | 65/35/0 | |

| Q11 | Repetitive measurement of antibody specific to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be performed 4–8 weeks after pneumococcal 23 polyvalent vaccine injection only when immunodeficiency is suspected and the baseline level is low. | 60/30/10 | |

| Q12 | Autoimmune markers (FANA, RF, anti-CCP, ANCA) should be measured in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 40/25/35 | |

| Q13 | Autoimmune markers should be measured only when rheumatologic diseases are suspected. | 65/15/20 | |

| Q14 | When primary ciliary dyskinesia is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q15 | In patients <50 years of age without a definite cause of bronchiectasis, questionnaires of high diagnostic sensitivity should be used for the differential diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. | 85/15/0 | |

| Q16 | When alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | 95/5/0 | |

| Q17 | If patients <50 years of age without a definite cause of bronchiectasis and demonstrate panacinar emphysema on basal lung CXR, tests for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency should be performed. | 60/35/5 | |

| Q18 | When cystic fibrosis is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | 90/10/0 | |

| Section 3. Pulmonary function and microbiological tests | |||

| Q19 | Prebronchodilator spirometry should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q20 | Postbronchodilator spirometry combined with prebronchodilator spirometry is indicated for all patients first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 95/0/5 | |

| Q21 | Diffusion capacity should be measured if indicated when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 65/25/10 | |

| Q22 | Lung volume should be measured if indicated when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 40/40/20 | |

| Q23 | Sputum Gram stain and bacterial culture should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 90/5/5 | |

| Q24 | Sputum AFB stain and culture should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 95/5/5 | |

| Q25 | Sputum fungal culture should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 50/25/25 | |

| Q26 | All patients should receive testing for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 0/45/55 | |

| Q27 | Tests for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis should be performed when patients with bronchiectasis manifest chronic pulmonary disease and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is suspected. | 95/5/0 | |

| Section 4. Laboratory tests | |||

| Q28 | All stable patients should receive laboratory testing, including CBC, liver function tests, BUN, creatinine, and CRP. | 95/5/0 | |

| Section 5. Paranasal sinus tests | |||

| Q29 | All patients should receive PNS X-ray when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 90/5/5 | |

| Q30 | All patients should receive PNS CT when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 5/15/80 | |

| Optimal cutoff for analyzing survey results | |||

| Q31 | What is the optimal cutoff for analyzing survey results? | A) 71 | |

| (A 70%/30% cutoff means a statement with ≥70% agreement should be recommended, a statement with ≥30% and <70% agreement rate should be considered as conditional based on the choice of the physician and patient, and a statement with <30% agreement should not be recommended.) | B) 12 | ||

| C) 6 | |||

| A) 70%/30%, B) 80%/30%, C) 70%/20%, D) 80%/20% | D) 12 | ||

Agreement rate was defined as the percentage of experts who answered, “strongly agree” or “agree,” and the disagreement rate was the percentage who answered “disagree” or “strongly disagree.”

CT: computed tomography; ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CBC: complete blood count; FANA: fluorescent antinuclear antibody; RF: rheumatoid factor; anti-CCP: anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide; ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; CXR: chest X-ray; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; CRP: C-reactive protein; PNS: paranasal sinus.

4. Survey round 2

A document for the round 2 survey was composed based on the results of the round 1 survey and feedback from the experts. This survey was emailed to all panel members who responded during round 1. In round 2, the experts used the same voting method as described for round 1. The document for round 2 also indicated the rates of expert panel’s agreement/disagreement. Based on the results of round 2, a third survey or an online meeting was considered if indicated. The final version of the round 2 survey is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Survey round 2: questions and agreement/disagreement rates

| Choose one of the answers to each statement (Strongly agree/Agree/Neutral/Disagree/Strongly disagree) | Agreement/Neutral/Disagreement rates (%)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Section 1. Overview | |||

| Q1 | A standardized diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis is useful in clinical practice. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q2 | In patients <50 years of age without definite cause of bronchiectasis, additional tests should be performed to elucidate the etiology beyond a specific diagnostic bundle. | 80/20/0 | |

| Section 2. Tests to search for the causes of bronchiectasis | |||

| Q3 | All patients should receive a chest CT when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 95/5/0 | |

| Q4 | All patients should receive tests to elucidate eosinophilic endotype (CBC, total Ig E) when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 55/15/30 | |

| Q5 | All patients should receive tests related to ABPA when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 15/30/55 | |

| Q6 | Tests related to ABPA should be performed only in patients with bronchiectasis carrying a history of asthma. | 80/5/15 | |

| Q7 | Serum Ig levels should be measured in patients <50 years of age when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 65/15/20 | |

| Q8 | Serum Ig levels should be measured only when immunodeficiency is suspected. | 70/5/25 | |

| Q9 | A baseline level of antibody specific to Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be measured in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 0/15/85 | |

| Q10 | A baseline level of antibody specific to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be measured only when immunodeficiency is suspected. | 90/10/0 | |

| Q11 | Repetitive measurement of antibody levels specific to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be performed 4–8 weeks after pneumococcal 23 polyvalent vaccine injection only when immunodeficiency is suspected and the baseline level was low. | 85/15/0 | |

| Q12 | Autoimmune markers should be measured in patients <50 years of age when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 50/25/25 | |

| Q13 | Autoimmune markers should be measured only when rheumatologic diseases are suspected. | 95/5/0 | |

| Q14 | When primary ciliary dyskinesia is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q15 | In patients <50 years of age without a definitive cause of bronchiectasis, questionnaires with a high diagnostic sensitivity should be used for the differential diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q16 | When alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q17 | If patients <50 years of age do not have a definitive cause of bronchiectasis and demonstrate panacinar emphysema on basal lung CXR, tests for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency should be performed. | 80/20/0 | |

| Q18 | When cystic fibrosis is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | 100/0/0 | |

| Section 3. Pulmonary function and microbiological tests | |||

| Q19 | Prebronchodilator spirometry should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q20 | Postbronchodilator spirometry should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 100/0/0 | |

| Q21 | Diffusion capacity should be included in a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis. | 45/25/30 | |

| Q22 | Lung volume should be included in a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis. | 35/20/45 | |

| Q23 | Sputum Gram stain and bacterial culture should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 95/0/5 | |

| Q24 | Sputum AFB stain and culture should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 95/0/5 | |

| Q25 | Sputum fungal culture should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 25/35/40 | |

| Q26 | All patients should be tested for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 5/15/80 | |

| Q27 | Tests for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis should be performed only when chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is suspected. | 95/5/0 | |

| Section 4. Laboratory tests | |||

| Q28 | All patients should undergo laboratory testing, including CBC, liver function, BUN, creatinine, and CRP, when they are in a stable state. | 95/0/5 | |

| Section 5. Paranasal sinus tests | |||

| Q29 | All patients should receive a PNS X-ray when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 95/0/5 | |

| Q30 | All patients should receive a PNS CT when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | 0/10/90 | |

| Optimal cutoff for analyzing survey results | |||

| Q31 | Which is the optimal cutoff for analyzing survey results? | A) 85 | |

| (A 70%/30% cutoff means a statement with ≥70% agreement should be recommended, a statement with ≥30% and <70% agreement rate should be considered as conditional based on the choice of physician and patient., and a statement with <30% agreement should not be recommended) | B) 5 | ||

| C) 5 | |||

| A) 70%/30%, B) 80%/30%, C) 70%/20%, D) 80%/20% | D) 5 | ||

Agreement rate was defined as the percentage of experts who answered “strongly agree” or “agree.” The disagreement rate was the percentage of experts who answered “disagree” or “strongly disagree.”

CT: computed tomography; CBC: complete blood count; ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CXR: chest X-ray; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; PNS: paranasal sinus.

5. Analysis

The panel’s opinions on a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis were collected from the round 1 and round 2 Delphi method surveys. Based on the panel’s recommendation, a 70%/30% cutoff was used to decide whether or not to recommend the statement. The statement was recommended if there was ≥70% agreement. If the agreement was ≥30% but <70%, it was considered conditional based on the choice of the physician and patient. If the agreement was <30% with a statement it was not recommended.

Results

The first survey was circulated by email between March 24, 2021 and April 15, 2021. The response rate was 95% (n=20/21). In the overview section, most experts agreed on the necessity for a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis. Although there were differences of opinion regarding the need to test for immunodeficiency, most experts agreed on the need for additional testing of younger (<50 years) patients with bronchiectasis without a definite cause and on referral to other institutions with access to diagnostic testing when cystic fibrosis (involving predominantly upper lung lobes, gastrointestinal symptoms due to malabsorption, pancreatitis, diabetes mellitus, and infertility), primary ciliary dyskinesia (predominantly middle and lower lung lobes, sinusitis, recurrent otitis media, situs inversus, and infertility), and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (panacinar emphysema in lower lung lobes) were suspected [14,15]. In the pulmonary function testing and microbiologic testing sections, most experts agreed on pre- and post-bronchodilator spirometry, Gram stain and bacterial culture, and acid-fast bacilli stain and culture. However, there were differences of opinion regarding other pulmonary function and microbiological tests. Most panelists agreed on the need for laboratory tests for stable patients as well as paranasal sinus X-rays when bronchiectasis was diagnosed. The specific rates of agreement and disagreement based on the round 1 survey are noted in Table 1.

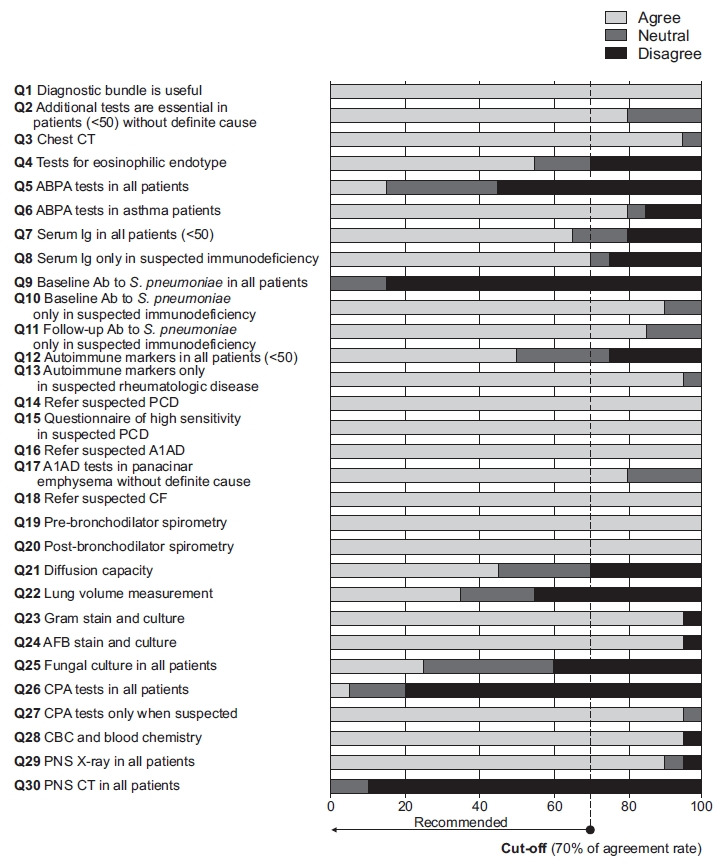

The second survey was also circulated by email between May 7, 2021 and May 13, 2021. The document was sent to the 20 experts who responded to the round 1 survey. The round 2 survey had a 100% response rate. The round 2 survey attempted to narrow the discrepancies found in the round 1 survey. Expert panelists did not recommend testing for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), immunodeficiency, autoimmune diseases, and chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in all patients with bronchiectasis. Instead, they recommended such tests only when the diseases were clinically suspected as follows: (1) ABPA in patients with uncontrolled asthma and recurrent pulmonary opacities, (2) immunodeficiency in patients with a history of recurrent infection or comorbidities of hematological malignancies, (3) autoimmune diseases in patients with known connective tissue diseases (especially rheumatoid arthritis) or suspected symptoms of connective tissue diseases, and (4) chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with a long-term (several months) history of chronic productive cough (or hemoptysis) and one or more cavities on chest X-rays [14,15,21]. Detailed rates of agreement and disagreement from the round 2 survey are noted in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Results of survey round 2. <50: <50 years of age; CT: computed tomography; ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; Ab: antibody; PCD: primary ciliary dyskinesia; A1AD: alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency; CF: cystic fibrosis; AFB: acid-fast bacilli; CPA: chronic pulmonary aspergillosis; CBC: complete blood count; PNS: paranasal sinus.

Table 3 summarizes the results of the modified Delphi survey regarding a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis in South Korea. All 30 statements are classified into three categories as recommended, conditional, or not recommended. There were 20 recommendations, including when to order specific tests to determine etiology, when to refer patients to more specialized centers, and specific microbiological, laboratory, radiological, and pulmonary function tests. Additionally, five statements were conditionally recommended and five not recommended.

Table 3.

Recommended diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis in South Korea

| Statements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Recommended | ||

| 1 | A standardized diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis is useful in clinical practice. | |

| 2 | In patients <50 years of age without a definitive cause of bronchiectasis, additional tests should be performed to elucidate the etiology beyond a standardized diagnostic bundle. | |

| 3 | All patients should receive a chest CT when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 4 | Tests related to ABPA should be performed only in patients with bronchiectasis and a history of asthma. | |

| 5 | Serum Ig levels should be measured when immunodeficiency is suspected. | |

| 6 | A baseline level of specific antibody to Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be measured when immunodeficiency is suspected. | |

| 7 | Repetitive measurement of antibody levels specific to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should be performed 4–8 weeks after pneumococcal 23 polyvalent vaccine injection when immunodeficiency is suspected and the baseline level was low. | |

| 8 | Autoimmune markers should be measured only when rheumatologic diseases are suspected. | |

| 9 | When primary ciliary dyskinesia is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | |

| 10 | In patients <50 years of age without a definitive cause of bronchiectasis, questionnaires with a high diagnostic sensitivity should be used for the differential diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia. | |

| 11 | When alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | |

| 12 | Tests for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency should be performed in patients <50 years of age without a definite cause of bronchiectasis and demonstrate panacinar emphysema on basal lung CXR. | |

| 13 | When cystic fibrosis is suspected, clinicians should refer patients to institutions where diagnostic tests are available. | |

| 14 | Prebronchodilator spirometry should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 15 | Postbronchodilator spirometry is indicated for all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 16 | Sputum Gram stain and bacterial culture are indicated for all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 17 | Sputum AFB stain and culture should be performed in all patients when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 18 | Tests for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis should be performed only when chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is suspected. | |

| 19 | All patients should receive laboratory testing, including CBC, liver function tests, BUN, creatinine, and CRP when they are in a stable state. | |

| 20 | All patients should receive a PNS X-ray when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| Conditional | ||

| 1 | All patients receive tests to evaluate eosinophilic endotype (CBC, total IgE) when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 2 | Serum Ig levels are measured in patients <50 years of age when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 3 | Autoimmune markers are measured in patients <50 years of age when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 4 | Diffusion capacity is included in the diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis. | |

| 5 | Lung volume is included in the diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis. | |

| Not recommended | ||

| 1 | None of the patients should undergo testing for ABPA when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 2 | A baseline level of antibody specific to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides should not be measured in any patient first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 3 | A sputum fungal culture should not be performed in any patient first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 4 | None of the patients should undergo testing for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

| 5 | None of the patients should receive a PNS CT when first diagnosed with bronchiectasis. | |

If age (e.g., less than 50 years) is not specified, the statements are applicable to adults of all ages.

CT: computed tomography; ABPA: allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis; CXR: chest X-ray; AFB: acid-fast bacilli; CBC: complete blood count; BUN: blood urea nitrogen; CRP: C-reactive protein; PNS: paranasal sinus.

Discussion

In this study involving 21 expert participants, 30 statements regarding a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis were classified as recommended, conditional, or not recommended. An expert panel agreed that (1) a standardized diagnostic bundle is useful in clinical practice; (2) diagnostic tests for specific diseases, including immunodeficiency, ABPA, and rheumatologic diseases should be performed when clinically suspected; (3) initial diagnostic tests, including sputum microbiology, complete blood count, blood chemistry, chest computed tomography, paranasal X-ray, and spirometry are essential for all patients with bronchiectasis; and (4) patients suspected with rare causes such as primary ciliary dyskinesia, cystic fibrosis, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency should be referred to specialized centers.

As previously noted in the international guideline [15], this study also found that all experts agreed that a standardized diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis is useful in clinical practice. In line with this recommendation, a previous study noted that a standardized etiological algorithm for bronchiectasis has reduced the frequency of diagnosis of idiopathic bronchiectasis from 42% to 29% [22]. Given the substantial differences in the etiology of bronchiectasis and clinical presentation among different regions and ethnic groups [10], the development of a diagnostic bundle for bronchiectasis optimized for the population in South Korea is necessary. This expert consensus will be the cornerstone for the future development of the Korean bronchiectasis guideline, incorporating the study results from the Korean Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (KMBARC) [23].

In this study, the experts recommended diagnostic tests that are currently incorporated in international bronchiectasis guidelines released recently [14,15]. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria, commonly isolated in patients with bronchiectasis [24], plays a role in diagnosing treatable etiologies and improving long-term outcomes [25]. Diagnosing chronic infections with Pseudomonas or other bacteria may also explain why some patients experience severe disease and exacerbations more frequently [25,26]. This microbiological information can assist clinicians in diminishing symptom burden and future risk of exacerbation [27,28]. Similarly, pulmonary function tests, recommended by most experts in this study, have been used to estimate the mortality of patients with bronchiectasis [29] and identify patients might benefit from bronchodilators [27,28,30].

Interestingly, there were some discrepancies between the study panel’s recommendations and international guidelines. Tests for ABPA were not recommended for all patients with bronchiectasis but only in those with a history of asthma. However, tests for ABPA are included in a minimum diagnostic bundle of the European Respiratory Society and the British Thoracic Society guidelines [14,15]. Additionally, although the British Thoracic Society guideline recommends testing for immunoglobulins and specific antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides in all patients with bronchiectasis [14], the current panel recommended testing only in specific subpopulations. These discrepancies may reflect the Korean clinicians frequently encounter post-infectious, including post-tuberculosis (TB), bronchiectasis as a major portion of bronchiectasis in real-world practice. Additionally, this could also be attributed to limited testing of specific antibodies to S. pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides in South Korea and the relatively low level of awareness regarding primary immunodeficiency among physicians. According to the KMBARC registry data, the most common etiologies of bronchiectasis were idiopathic (41%), TB (20%), post-infective (20%), asthma (5%), and nontuberculous mycobacteria (4%) in South Korea [10]. However, the decrease in TB incidence over the past decades in South Korea [31] will likely change the major etiologies of bronchiectasis in the future. Additionally, developing a diagnostic bundle to evaluate the etiology of bronchiectasis systematically may decrease the rate of idiopathic disease resulting in changes in major etiologies in South Korea, suggesting the need for further reviews of the Korean bronchiectasis registry. The diagnostic bundle may need to be updated according to the study results.

There are potential limitations to this study. First, because most experts are respiratory physicians working at secondary or tertiary university-affiliated hospitals, all of the diagnostic tests recommended by this study may not be available in primary care settings. Second, this study focused on the development of a diagnostic bundle for adult patients with bronchiectasis. Therefore, a further study is needed to develop a diagnostic bundle for pediatric patients with bronchiectasis. In contrast, two pediatricians, participating in this study, are experts in the field of primary ciliary dyskinesia and immunodeficiency respectively, which is a strength of this study.

In conclusion, in this Delphi survey, expert consensus statements on specific diagnostic tests were proposed to determine the etiology and appropriate laboratory, microbiological, and pulmonary function tests for managing patients with bronchiectasis in South Korea.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sang Yong Sim, RN (Clinical Research Center for Chronic Obstructive Airway Diseases, Asan Medical Center) for assistance with the study.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: Choi H, Lee H, Ra SW, Oh YM. Methodology: Choi H, Lee H, Ra SW, Jang JG, Lee JH, Jhun BW, Park HY, Jung JY, Oh YM. Formal analysis: Choi H, Lee SJ, Jo KW, Rhee CK, Kim C, Lee SW, Oh YM. Data curation: Choi H, Min KH, Kwon YS, Kim DK, Lee JH. Investigation: Choi H, Lee H, Ra SW, Park YB, Chung EH, Kim YJ, Yoo KH, Oh YM. Writing - original draft preparation: Choi H, Oh YM. Writing - review and editing: all authors. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

No funding to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi H, Yang B, Nam H, Kyoung DS, Sim YS, Park HY, et al. Population-based prevalence of bronchiectasis and associated comorbidities in South Korea. Eur Respir J. 2019;54:1900194. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00194-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim C, Kim DG. Bronchiectasis. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2012;73:249–57. doi: 10.4046/trd.2012.73.5.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seitz AE, Olivier KN, Adjemian J, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Trends in bronchiectasis among medicare beneficiaries in the United States, 2000 to 2007. Chest. 2012;142:432–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringshausen FC, de Roux A, Pletz MW, Hamalainen N, Welte T, Rademacher J. Bronchiectasis-associated hospitalizations in Germany, 2005-2011: a population-based study of disease burden and trends. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringshausen FC, de Roux A, Diel R, Hohmann D, Welte T, Rademacher J. Bronchiectasis in Germany: a populationbased estimation of disease prevalence. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:1805–7. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00954-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quint JK, Millett ER, Joshi M, Navaratnam V, Thomas SL, Hurst JR, et al. Changes in the incidence, prevalence and mortality of bronchiectasis in the UK from 2004 to 2013: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:186–93. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01033-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang B, Choi H, Lim JH, Park HY, Kang D, Cho J, et al. The disease burden of bronchiectasis in comparison with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a national database study in Korea. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:770. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.11.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi H, Yang B, Kim YJ, Sin S, Jo YS, Kim Y, et al. Increased mortality in patients with non cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis with respiratory comorbidities. Sci Rep. 2021;11:7126. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86407-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sin S, Yun SY, Kim JM, Park CM, Cho J, Choi SM, et al. Mortality risk and causes of death in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Respir Res. 2019;20:271. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Choi H, Chalmers JD, Dhar R, Nguyen TQ, Visser SK, et al. Characteristics of bronchiectasis in Korea: first data from the Korean Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration registry and comparison with other international registries. Respirology. 2021;26:619–21. doi: 10.1111/resp.14059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dhar R, Singh S, Talwar D, Mohan M, Tripathi SK, Swarnakar R, et al. Bronchiectasis in India: results from the European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) and Respiratory Research Network of India Registry. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1269–79. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McShane PJ, Naureckas ET, Tino G, Strek ME. Noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:647–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201303-0411CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonnell MJ, Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, Restrepo MI, Finch S, Pesci A, et al. Comorbidities and the risk of mortality in patients with bronchiectasis: an international multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:969–79. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30320-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill AT, Sullivan AL, Chalmers JD, De Soyza A, Elborn SJ, Floto AR, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax. 2019;74:1–69. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, Aliberti S, Marshall SE, Loebinger MR, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00629-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao YH, Guan WJ, Liu SX, Wang L, Cui JJ, Chen RC, et al. Aetiology of bronchiectasis in adults: a systematic literature review. Respirology. 2016;21:1376–83. doi: 10.1111/resp.12832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amati F, Simonetta E, Pilocane T, Gramegna A, Goeminne P, Oriano M, et al. Diagnosis and initial investigation of bronchiectasis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42:513–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manag Sci. 1963;9:458–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R, Global Consensus G. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett C, Vakil N, Bergman J, Harrison R, Odze R, Vieth M, et al. Consensus statements for management of Barrett’s dysplasia and early-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma, based on a Delphi process. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:336–46. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Ader F, Chakrabarti A, Blot S, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:45–68. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Araujo D, Shteinberg M, Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, Hill AT, Fardon T, et al. Standardised classification of the aetiology of bronchiectasis using an objective algorithm. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1701289. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01289-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee H, Choi H, Sim YS, Park S, Kim WJ, Yoo KH, et al. KMBARC registry: protocol for a multicentre observational cohort study on non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis in Korea. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e034090. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang B, Ryu J, Kim T, Jo YS, Kim Y, Park HY, et al. Impact of bronchiectasis on incident nontuberculous mcobacterial pulmonary disease: a 10-year national cohort study. Chest. 2021;159:1807–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jose RJ, Loebinger MR. Clinical and radiological phenotypes and endotypes. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;42:549–55. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aliberti S, Lonni S, Dore S, McDonnell MJ, Goeminne PC, Dimakou K, et al. Clinical phenotypes in adult patients with bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2016;47:1113–22. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01899-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Oh YM. Clinical approach to non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis based on recent clinical guideline. Korean J Med. 2020;95:141–50. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi H, Lee H, Ra SW, Oh YM. Update on pharmacotherapy for adult bronchiectasis. J Korean Med Assoc. 2020;63:486–92. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Aliberti S, McDonnell MJ, Lonni S, Davidson J, et al. The bronchiectasis severity index: an international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:576–85. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1575OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SY, Lee JS, Lee SW, Oh YM. Effects of treatment with longacting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) and long-acting betaagonists (LABA) on lung function improvement in patients with bronchiectasis: an observational study. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13:169–77. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim JH, Yim JJ. Achievements in and challenges of tuberculosis control in South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1913–20. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.141894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]