Dear Editor

SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern threaten evasion of natural and vaccine-induced immunity. There is an urgent need to know how effective different vaccine strategies will be in reducing the transmission of and disease severity arising from the Omicron variant of concern (VOC). In the UK, two main vaccines have formed the basis of the national immunisation strategy: the AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZ)1 and the Pfizer-BioNtech 162b2 COVID-19 vaccine (PFZ).2 Both elicit immune responses directed against the original wildtype SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan) spike glycoprotein and both have been shown to reduce the incidence of severe disease in clinical trials.1 , 2 In mid-2021, the Delta VOC became dominant worldwide and led to the widespread deployment of booster immunisations using mRNA vaccines. In late November 2021, the Omicron VOC rapidly emerged displaying even greater transmissibility and has become the dominant SARS-CoV-2 virus in the UK and across the world.3 These rapid shifts in the pre-dominance of VOC outpaces and impairs the development and testing in clinical trials of new VOC-tailored vaccines. We do not yet know how well the different vaccine strategies applied in the UK will reduce the transmission of and severity of disease arising from rapidly emerging VOC in the general population and immunological vulnerable subgroups.

We have used the core design of an anti-IgG/A/M SARS-CoV-2 ELISA4 , 5 to measure IgG antibodies specific for spike protein from the original Wuhan strain,6 B.1.617.2 (Delta - Abingdon Health) and B.1.1.529 (Omicron - SinoBiological China). In addition, we assayed serial dilutions (250 – 7.8 IU/mL) of the WHO standard NIBSC 20/1367 and the therapeutic monoclonal antibody therapy Sotrovimab (Glaxo Smith Kline) the base concentration of which is 62.5 mg/ml and a 500 mg dose is given to patients. We have used these ELISAs to determine cross-reactivity of spike glycoprotein induced antibody against Delta and Omicron variants before and after third SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose.

We have recruited three well-characterised cohorts: firstly, a health care worker cohort from University Hospitals Birmingham from the Determining the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in convalescent health care workers (COCO) study, who had PFZ as their primary two-dose vaccine course followed by PFZ booster (PPP cohort). Secondly, individuals classed as clinically extremely vulnerable (CEV) attending general practice for vaccination in Ulster, who had the AZ vaccine as their primary two-dose vaccine course followed by a PFZ third dose (AAP). Lastly, individuals on haemodialysis under renal care at the University Hospitals Birmingham; 70.3% of which had AZ as their primary course (HD cohort) followed by a PFZ third dose. Serum samples were taken 6 months following their second vaccination of their primary course, prior to the third dose with PFZ, and also 28 days following vaccination.

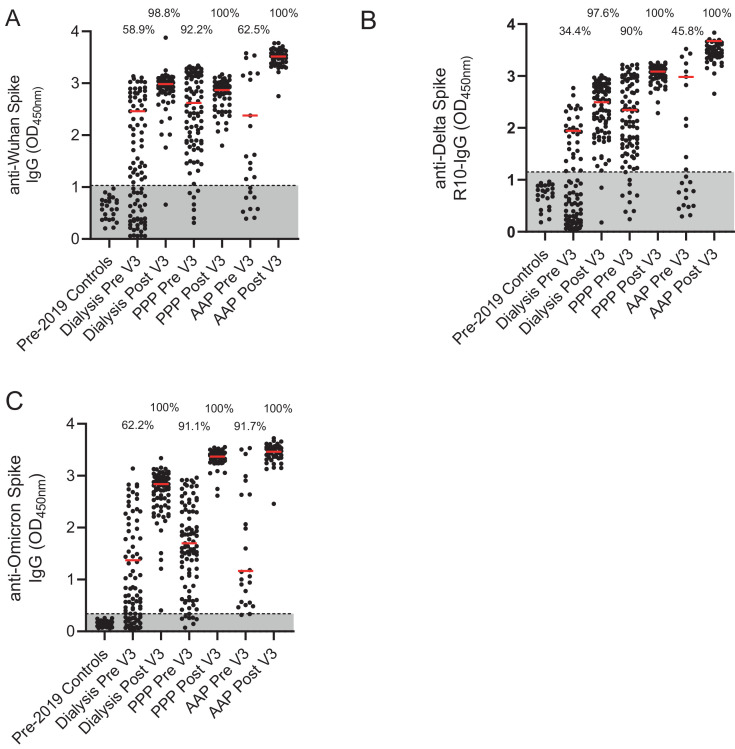

There was evidence of suboptimal seropositivity 6 months post primary dose of vaccination in all groups but particularly amongst HD and CEV patients. Samples taken 6 months post-primary vaccine course showed that for the HD cohort, 58.9% of individuals were seropositive against the Wuhan strain, 34.4% against Delta and 62.2% against Omicron strains. For the PPP cohort, seropositivity was maintained at 92.2% against Wuhan, 90% against Delta and 91.1% against Omicron strains. For the AAP cohort, seropositivity was 62.5% against Wuhan, 45.8% against Delta and 91.7% against Omicron strains (Fig. 1 a-c).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of cohort with antibodies against Wuhan, Delta and Omicron strain.

A-Detection of anti- Wuhan spike IgG in pre-2019 controls, a dialysis population, a cohort of health care workers who have had three PFZ vaccines and a Clinically Extremely Vulnerable population in general practice who have had two AZ and one PFZ vaccine. Results are given for pre and post 3rd dose of vaccination. Percentage of cohort that are considered seropositive are included above the dot plots. The red line represents the median of the seropositive individuals in that cohort.

B-Detection of anti-Delta spike IgG for the same populations.

C-Detection of anti- Omicron spike IgG for the same populations

Pre- pre-3rd dose of vaccine and 6 months post 2nd dose. Post- 28 days post 3rd dose of vaccine. PPP- 3 Pfizer-BioNtech vaccines given in this cohort. AAP- two AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccines and the one Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine given in this cohort. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Post third vaccine dose, there was a significant increase in the percentage of individuals who were seropositive and a rise in the median serum antibody concentration (as measured by optical density or OD) of these seropositive individuals. For the HD cohort, seropositivity was 98.8% against the Wuhan, 97.6% against Delta and 100% against Omicron strains. For the PPP and AAP cohorts seropositivity was 100% against all 3 strains . The increase in median OD following vaccination in HD patients was 2.46 to 2.98 (p<0.0001) for the Wuhan, 1.94 to 2.49 (non-significant (ns)) for Delta, and 1.37 to 2.84 (p<0.0001) for Omicron strains. The increase in median OD for the PPP cohort against the Wuhan strain was 2.62 to 2.88 (ns), for Delta 2.33 to 3.08 (p<0.0001) and for Omicron 1.71 to 3.37 (p<0.0001). For the AAP cohort, for the Wuhan strain the increase was from 2.38 to 3.52 (p<0.0001), for Delta 2.98 to 3.45 (p = 0.0044) and for Omicron 1.17 to 3.46 (p<0.0001). We also compared antibody concentrations following booster immunisation between the PPP and AAP groups: in the AAP group there was a higher median OD for the Wuhan (2.88 v 3.52, p<0.0001) and Delta strains (3.08 v 3.45, p = 0.0022) but not for the Omicron strain (3.37 v 3.46, ns) compared to the PPP group suggesting heterologous vaccine strategies may demonstrate enhanced immunogenicity against these SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Lastly, the WHO NIBSC 20/136 standard was run as a standard curve in the Wuhan, Delta and Omicron ELISAs and no significant loss of antibody binding was observed against any VOC (Supplementary Figure 1a). Similarly, a dilution series from 6.5 mg/ml to 0.003 mg/ml of Sotrovimab (GSK) found no loss of antibody binding against Omicron (Supplementary Figure 1b). Strong correlations exist between antibody binding and neutralisation8 and between the presence of neutralising antibodies and protection against severe COVID-19.9

Understanding the pre-existing seroprevalence of antibodies directed against novel SARS-CoV-2 VOC and their induction following third-primary or booster immunisation is of critical importance in guiding public health policy during the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. This knowledge is of particular relevance to immunologically vulnerable groups who either do not make a robust serological response to vaccination or fail to retain a serological response over time. In this study, we provide evidence supporting the need of a third dose of vaccination due to a waning antibody response at 6 months and the broadly cross-reactive humoral immunogenicity of the third vaccine dose against rapidly evolving SARS-CoV-2 VOC in healthy, CEV, and HD patients. However, it is important to note that antibody binding doesn't necessarily equate with functionality of antibodies, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals. Therefore, this is the best-case scenario and this study will need to be repeated with neutralisation assays going forward.

Ethical approval

The COCO study was ethically approved for this work by the London - Camden and Kings Cross Research Ethics Committee on behalf of the United Kingdom Health Research Authority – reference 20/HRA/1817. The Haemodialysis study was ethically approved for this work by the North West Preston Research Committee on behalf of the United Kingdom Health Research Authority for the National Institute of Health Research Coronavirus Immunological Analysis study – reference 20/NW/ 0240. The Ulster study was ethically approved for this work by the Office of Research Ethics Committee for Northern Ireland on behalf of the United Kingdom Health Research Authority - reference 20/WM/0184. The pre-2019 health controls was ethically approved for this work by the University of Birmingham Research Ethics Committee, United Kingdom - reference ERNE_16–178 (2002/201, Amendment Number 4).

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and patients that have kindly volunteered for this study. Thanks also to Abingdon Health for the Wuhan and Delta antigens. The authors would like to acknowledge the COVID-HD Birmingham Study Group and PITCH consortium that have enabled this work, the staff of the Clinical Immunology Service, managed by Tim Plant, who helped process the healthcare worker and haemodialysis samples and Dr. Margaret Goodall for her expertise in antibody production and assay development. The authors would also like to acknowledge the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)/Wellcome Trust Birmingham Clinical Research Facility and University Hospitals Birmingham Research and Development team, in particular the research nurses that enabled the sample consent and sample collection including Mary Dutton, Lesley Fifer, Sinead White, Natalie Walmsley-Allen, Lucy Atchinson-Jones, Kulli Kuningas, Margaret Carmody, Rani Maria Joseph, Christopher McGhee, Shannon Page and Michelle Bates. Also, The Ulster Pandemic Study team. The COCO/PITCH healthcare worker cohort was funded by the United Kingdom Department of Health and Social Care and United Kingdom Research and Innovation COVID-19 Rapid Response Rolling Call as part of the PITCH Consortium. The HD cohort was funded by the United Kingdom Research and Innovation COVID-19 Rapid Response Rolling Call. The COVID-HD Birmingham Study Group include Claire Backhouse, Anna Casey, Lynsey Dunbar, Beena Emmanuel, Megan Fahy, Alexandra Godlee, Paul Moss, Peter Nightingale, Liz Ratcliffe, Stephanie Stringer, Matthew Tabinor, Sian Faustini, Adam Cunningham, Alex Richter, Lorraine Harper. The PITCH study Group include Susanna Dunachie, Paul Klenerman, Lance Turtle, Thushan de Silva, Christopher Duncan, Rebecca Payne, Alex Richter, Ellie Barnes, Miles Carroll, Alexandra Deeks, Christina Dold.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2022.01.002.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A., Weckx L.Y., Folegatti P.M., Aley P.K. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397(10269):99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.England P.H. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England. Sage. 2021;(April).

- 4.Cook A.M., Faustini S.E., Williams L.J., Cunningham A.F., Drayson M.T., Shields A.M. Validation of a combined ELISA to detect IgG, IgA and IgM antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in mild or moderate non-hospitalised patients. J Immunol Methods. 2021:494. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2021.113046. Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faustini S.E., Jossi S.E., Perez-Toledo M., Shields A.M., Allen J.D., Watanabe Y. Development of a high-sensitivity ELISA detecting IgG, IgA and IgM antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein in serum and saliva. Immunology. 2021;164(1):135–147. doi: 10.1111/imm.13349. Sep 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe Y., Allen J.D., Wrapp D., McLellan J.S., Crispin M. Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Science. 2020;369(6501) doi: 10.1126/science.abb9983. Jul 17330-3. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32366695/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NIBSC NI for BS andControls. WHO International Standard First WHO International Standard for anti-SARS-CoV-2 Immunoglobulin (human) NIBSC Code: 20/136 Instructions for Use (Version 2.0, Dated 17/12/2020). Potters Bar, Hertfordshire, EN6 3QG.

- 8.Earle K.A., Ambrosino D.M., Fiore-Gartland A., Goldblatt D., Gilbert P.B., Siber G.R. Evidence for antibody as a protective correlate for COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine. 2021 Jul 22;39(32):4423–4428. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.063. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34210573/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoury D.S., Cromer D., Reynaldi A., Schlub T.E., Wheatley A.K., Juno J.A. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. Jul 1Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34002089/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.