Abstract

Background

Adjuvant aromatase inhibitors (AI) improve survival compared to tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor‐positive stage I to III breast cancer. In approximately half of these women, AI are associated with aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms (AIMSS), often described as symmetrical pain and soreness in the joints, musculoskeletal pain and joint stiffness. AIMSS may have significant and prolonged impact on women's quality of life. AIMSS reduces adherence to AI therapy in up to a half of women, potentially compromising breast cancer outcomes. Differing systemic therapies have been investigated for the prevention and treatment of AIMSS, but the effectiveness of these therapies remains unclear.

Objectives

To assess the effects of systemic therapies on the prevention or management of AIMSS in women with stage I to III hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and Clinicaltrials.gov registries to September 2020 and the Cochrane Breast Cancer Group (CBCG) Specialised Register to March 2021.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised controlled trials that compared systemic therapies to a comparator arm. Systemic therapy interventions included all pharmacological therapies, dietary supplements, and complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). All comparator arms were allowed including placebo or standard of care (or both) with analgesia alone. Published and non‐peer‐reviewed studies were eligible.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened studies, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias and certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach. Outcomes assessed were pain, stiffness, grip strength, safety data, discontinuation of AI, health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), breast cancer‐specific quality of life (BCS‐QoL), incidence of AIMSS, breast cancer‐specific survival (BCSS) and overall survival (OS). For continuous outcomes, we used vote‐counting by reporting how many studies reported a clinically significant benefit within the confidence intervals (CI) of the mean difference (MD) between treatment arms, as determined by the minimal clinically importance difference (MCID) for that outcome scale. For dichotomous outcomes, we reported outcomes as a risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI.

Main results

We included 17 studies with 2034 randomised participants. Four studies assessed systemic therapies for the prevention of AIMSS and 13 studies investigated treatment of AIMSS. Due to the variation in systemic therapy studies, including pharmacological, and CAM, or unavailable data, meta‐analysis was limited, and only two trials were combined for meta‐analysis. The certainty of evidence for all outcomes was either low or very low certainty.

Prevention studies

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on pain (from baseline to the end of the intervention; 2 studies, 183 women). The two studies, investigating vitamin D and omega‐3 fatty acids, showed a treatment effect with 95% CIs that did not include an MCID for pain. Systemic therapies may have little to no effect on grip strength (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.37 to 3.17; 1 study, 137 women) or on women continuing to take their AI (RR 0.16, 95% 0.01 to 2.99; 1 study, 147 women). The evidence suggests little to no effect on HRQoL and BCS‐QoL from baseline to the end of intervention (the same single study; 44 women, both quality of life outcomes showed a treatment effect with 95% CIs that did include an MCID).

The evidence is very uncertain for outcomes assessing incidence of AIMSS (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.06; 2 studies, 240 women) and the safety of systemic therapies (4 studies, 344 women; very low‐certainty evidence). One study had a US Food and Drug Administration alert issued for the intervention (cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 inhibitor) during the study, but there were no serious adverse events in this or any study.

There were no data on stiffness, BCSS or OS.

Treatment studies

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on pain from baseline to the end of intervention in the treatment of AIMSS (10 studies, 1099 women). Four studies showed an MCID in pain scores which fell within the 95% CI of the measured effect (vitamin D, bionic tiger bone, Yi Shen Jian Gu granules, calcitonin). Six studies showed a treatment effect with 95% CI that did not include an MCID (vitamin D, testosterone, omega‐3 fatty acids, duloxetine, emu oil, cat's claw).

The evidence was very uncertain for the outcomes of change in stiffness (4 studies, 295 women), HRQoL (3 studies, 208 women) and BCS‐QoL (2 studies, 147 women) from baseline to the end of intervention. The evidence suggests systemic therapies may have little to no effect on grip strength (1 study, 107 women). The evidence is very uncertain about the safety of systemic therapies (10 studies, 1250 women). There were no grade four/five adverse events reported in any of the studies. The study of duloxetine reported more all‐grade adverse events in this treatment group than comparator group.

There were no data on the incidence of AIMSS, the number of women continuing to take AI, BCCS or OS from the treatment studies.

Authors' conclusions

AIMSS are chronic and complex symptoms with a significant impact on women with early breast cancer taking AI. To date, evidence for safe and effective systemic therapies for prevention or treatment of AIMSS has been minimal. Although this review identified 17 studies with 2034 randomised participants, the review was challenging due to the heterogeneous systemic therapy interventions and study methodologies, and the unavailability of certain trial data. Meta‐analysis was thus limited and findings of the review were inconclusive. Further research is recommended into systemic therapy for AIMSS, including high‐quality adequately powered RCT, comprehensive descriptions of the intervention/placebo, and robust definitions of the condition and the outcomes being studied.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Aromatase Inhibitors, Aromatase Inhibitors/adverse effects, Breast Neoplasms, Breast Neoplasms/drug therapy, Musculoskeletal Pain, Musculoskeletal Pain/chemically induced, Musculoskeletal Pain/drug therapy, Musculoskeletal Pain/prevention & control, Quality of Life, Tamoxifen, Tamoxifen/adverse effects

Plain language summary

Systemic therapies for preventing or treating aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms in early breast cancer

What was the aim of this review?

Hormonal therapy with aromatase inhibitors is used to treat a type of early breast cancer (hormone‐receptor positive) in women after the menopause. AI cause side effects including joint and muscle pains and stiffness (aromatase inhibitors musculoskeletal symptoms, or so‐called AIMSS), which may cause some women to stop taking their aromatase inhibitors, and potentially worsen survival. The aim of this Cochrane Review was to examine whether systemic therapies (treatments that reach cells throughout the body by travelling through the bloodstream) can prevent or treat AIMSS. The authors collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer this question.

Key messages

It is very unclear if systemic therapies improve, worsen or make no difference to pain or quality of life for women taking aromatase inhibitors. Most of the evidence was of very low quality. It was very unclear if systemic therapies for AIMSS were safe.

What did the review study?

We looked at research studies of systemic therapies, which included medicines, vitamins, and complementary and alternative medicines, to see if these could prevent or treat the joint and muscle pains and stiffness of women taking aromatase inhibitors. We included trials of systemic therapies compared to placebo (dummy treatment), or to standard treatments. Women treated with aromatase inhibitors for early‐stage hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer were included. Most studies were for treatment of AIMSS.

Outcomes that were studied included changes in pain, stiffness, hand strength (grip strength), safety and side effects of the study treatments, number of women continuing to take their aromatase inhibitors, quality of life for women, how many women developed muscle and joint aches from their aromatase inhibitors, and survival.

What were the main results of this review?

After collecting and analysing all the relevant studies, we found 17 studies with 2034 women included. Different numbers of women were involved in these studies, ranging from 37 to 299. Four studies looked at systemic therapies to prevent the joint and muscle pains from aromatase inhibitors; 13 studies investigated systemic therapies to treat these symptoms. Ten studies were carried out in the USA, three in China, two in Australia, one in Italy and one in Brazil. Many of the studies had low numbers of women and this may have made it difficult to find small differences. There were problems with some studies being at risk of bias. Other problems were because several studies had not fully published information about their treatment ingredients or their results, so that some data were not available for review or analysis. In addition, studies used many different types of treatment, and it was not appropriate to combine their results in analysis.

AIMSS prevention studies

It is unclear whether any of these studies found a positive or negative effect on pain, and on the number of women who developed AIMSS because of the very low quality evidence. Systemic therapies may have little to no effect on grip strength, quality of life or on women continuing to take their aromatase inhibitors (low‐quality evidence). None of the studies looked at stiffness.

AIMSS treatment studies

It is unclear whether any of these studies found a positive or negative effect on pain, stiffness and quality of life of women because of the very low‐quality evidence. Systemic therapies likely result in little to no change on grip strength in women with AIMSS (low‐quality evidence). None of the studies looked at the number of women continuing to take aromatase inhibitors or who developed AIMSS, or their survival.

Safety

We do not know if systemic therapies for AIMSS are safe as the evidence is very uncertain. There were no serious side effects. One treatment, duloxetine, resulted in an increase in side effects for women, and one treatment, etoricoxib, had a safety alert during the trial. Length of monitoring of women for many studies was short. Safety data should be interpreted with caution.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

The last search for studies (published and ongoing) in this review was in September 2020 within the specified databases and in March 2021 in the Cochrane Breast Cancer's Specialised Register.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table ‐ Systemic therapy compared to control for treating aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms in women with early breast cancer.

| Systemic therapy compared to control for treating aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms in women with early breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with early breast cancer Setting: Intervention: systemic therapy Comparison: control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control | Risk with systemic therapy | |||||

| Change in pain from baseline to end of intervention assessed with: Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) worst pain; BPI severity follow‐up: 24 weeks | There were 2 studies (omega‐3 fatty acids, vitamin D) that showed a treatment effect with 95% CI that did not include a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for BPI pain scale. | 183 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on change in pain from baseline to end of intervention. | ||

| Change in grip strength from baseline to end of intervention follow‐up: 24 weeks | 85 per 1000 | 91 per 1000 (31 to 268) | RR 1.08 (0.37 to 3.17) | 137 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | The evidence suggests that systemic therapies results in little to no difference in grip strength from baseline to end of intervention. |

| Safety of systemic therapies in AIMSS | 1 study had a US Food and Drug Administration alert issued for the class of drug which the study drug belonged to (cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 inhibitors), but the study reported no serious adverse effects. No serious adverse events noted in any study. | 344 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc,d,e | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on safety of systemic therapies in AIMSS. | ||

| Effect on discontinuation of aromatase inhibitors (AI) follow‐up: 24 weeks | 39 per 1000 | 6 per 1000 (0 to 116) | RR 0.16 (0.01 to 2.99) | 147 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | The evidence suggests that systemic therapies results in little to no difference in effect on discontinuation of AIs. |

| Effect on breast cancer‐specific quality of life (BCS‐QoL) assessed with: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast (FACT‐B) follow‐up: 24 weeks | 1 study (omega‐3 fatty acids) showed a treatment effect with 95% CI that did include an MCID for this outcome measure. | 44 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | The evidence suggests that systemic therapies results in little to no difference in effect on BCS‐QoL. | ||

| Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) ‐ HRQoL: Total Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General(FACT‐G) score assessed with: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT‐G) follow‐up: 24 weeks | A single study (omega 3 fatty acids) showed a treatment effect with 95% CI which did include a MCID for this outcome measure. | (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | The evidence suggests that systemic therapies results in little to no difference in effect on HRQoL. | ||

| Incidence of AIMSS follow‐up: range 24 weeks to 52 weeks | 537 per 1000 | 440 per 1000 (338 to 569) | RR 0.82 (0.63 to 1.06) | 240 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,d | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on change in Incidence of AIMSS. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_424110183232321857. | ||||||

a High risk of reporting bias and attrition bias in single study. Downgraded one level. b Downgraded one level for indirectness (restricted population dependent on vitamin D level). c Downgraded one level for imprecision (small sample sizes). d Downgraded one level for risk of bias (high risk of bias across multiple domains). e High suspicion of publication bias (too few studies for funnel plot; one study in abstract form only).

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table ‐ Systemic therapy compared to control for preventing aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms in women with early breast cancer.

| Systemic therapy compared to control for preventing aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms in women with early breast cancer | ||||||

| Patient or population: health problem or population Setting: Intervention: Systemic therapy Comparison: Control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Control | Risk with Systemic therapy | |||||

| Change in pain from baseline to end of intervention follow‐up: range 30 days to 6 months | 4 studies showed a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in pain scores that fell within the 95% CIs of the measured effect (calcitonin, bionic tiger bone, Yi Shen Jian Gu granules and vitamin D). 6 studies showed a treatment effect with 95% CIs that did not include an MCID (testosterone, vitamin D, duloxetine, omega‐3 fatty acids, emu oil, Cat's claw). Due to the variation in systemic therapies, including pharmacological, complementary and alternative medicines, the studies could not be combined for meta‐analysis. | 1099 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c,d | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on change in pain from baseline to the end of intervention in the treatment of AIMSS. | ||

| Change in stiffness from baseline to end of intervention | 2 studies showed a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) in stiffness scores that fell within the 95% CIs of the measured effect (bionic tiger bone, Yi Shen Jian Gu granules). 2 studies that showed a treatment effect with 95% CIs that did not include an MCID (vitamin D, emu oil). | 295 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c,e,f | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on change in stiffness from baseline to the end of the intervention in the treatment of AIMSS. | ||

| Grip strength ‐ Vitamin D | There was a single study which did not show a MCID for grip strength which falls within the 95% CI for the measured effect (vitamin D). | (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,f | The evidence is uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on change in grip strength from baseline to the end of the intervention in the treatment of AIMSS 'little to no effect' | ||

| Effect on breast cancer‐specific quality of life (BCS‐QoL) | 2 studies investigated the effect on BCS‐QoL (bionic tiger bone, Yi Shen Jian Gu granules). All subscales of the same quality of life tool utilised in both of these studies (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast (FACT‐B)) showed an MCID for this tool that falls within the 95% CIs of the measured effect. | 147 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,g,h | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on effect on BCS‐QoL from baseline to the end of the intervention in the treatment of AIMSS. | ||

| Effect on health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) | 2 studies investigated the effect of BCS‐QoL (bionic tiger bone, Yi Shen Jian Gu granules) using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT‐G) tool. All subscales of this quality of life tool showed an MCID for this tool that fell within the 95% CIs of the measured effect. 1 study used the 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) and showed most individual subscales in this outcome showing effect size that did not include MCID for this tool within the 95% CIs of the measured effect. | 208 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,g,h | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of systemic therapies on HRQoL from baseline to the end of the intervention in the treatment of AIMSS. | ||

| Safety of systemic therapies for the treatment of AIMSS | There were no grade 4/5 adverse events reported in any studies. 1 study investigating duloxetine reported significantly more all‐grade adverse events in the systemic therapy arm (78%) than the control arm (50%) (P < 0.001). | 1250 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c,i | The evidence is very uncertain about the safety data in the use of systemic therapies for the treatment of AIMSS. | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_424113354545582340. | ||||||

a Downgraded one level for risk of bias (high risk of bias across multiple domains). b Downgraded one level for inconsistency (heterogeneity in interventions). c Downgraded one level for imprecision (small sample sizes and unable to be combined for meta‐analysis). d Downgraded one level for publication bias (funnel plot displayed asymmetry; multiple studies only written in abstract form). e Downgraded one level for risk of bias (one study had high risk of both performance and detection bias). f Downgraded one level for indirectness (one study with poorly defined AIMSS). g Downgraded one level for indirectness (no criteria for an AIMSS in one study and exclusion of bisphosphonates, which are frequently utilised in the target population). h Downgraded for imprecision (small sample size). i Downgraded one level for publication bias (multiple studies published in abstract form only).

Background

Description of the condition

Despite advances in screening and treatment, breast cancer continues to significantly impact the global community. There was an estimated 1.67 million new cases diagnosed in 2012 making breast cancer the most common non‐skin cancer in women, and it is the fifth most common cause of cancer death globally (Ferlay 2012). In women in high‐income regions of the world, breast cancer is second to lung cancer as the leading cause of death, and in lower income regions, breast cancer remains the leading cause of death (Ferlay 2012). Eighty percent of breast cancer is hormone receptor (i.e. oestrogen receptor or progesterone receptor, or both)‐positive, which is often described as 'endocrine‐sensitive' breast cancer (Nadji 2005). Treatment of postmenopausal women with hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer with aromatase inhibitor (AI) medications is effective. When compared to treatment with another hormonal therapy, tamoxifen, five years of AI therapy in early breast cancer improves disease‐free‐survival (DFS) and breast cancer‐specific survival (BCSS) (EBCTCG 2015). An AI medication called exemestane, used in combination with ovarian suppression in women with higher risk premenopausal breast cancer has also shown an improvement in DFS compared with tamoxifen (Francis 2015; Francis 2018). These results may see the adoption of AI therapy in a greater proportion of women with early breast cancer.

However, AIs are commonly associated with joint and muscular symptoms, commonly referred to as aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms (AIMSS) (Lintermans 2013). Approximately half of all women treated with AIs experience these musculoskeletal effects (Beckwee 2017), which can significantly impact on their quality of life. AIMSS usually presents as symmetrical pain or soreness in multiple joints within the first two to three months of initiating the AI (Burstein 2007). Women may also experience early‐morning stiffness and difficulty sleeping (Burstein 2007). Despite the survival advantage of AIs, between a quarter and a half of all women on this treatment choose to discontinue therapy (Chim 2013; Henry 2012; Kadakia 2016). AIMSS is the most common reason for women to discontinue AI therapy (Kwan 2017).

Description of the intervention

We aimed to investigate the impact of systemic therapies on the prevention or management of AIMSS. Systemic therapies range from prescription medications to dietary supplements such as vitamins. We also included complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) in our review. The National Centre for Complementary and Integrative Health defines CAM as "a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine" (NCCIH 2016).

How the intervention might work

There is a body of research investigating the mechanisms of action and the effectiveness of systemic therapies on other musculoskeletal conditions such as osteoarthritis, but quality evidence is still lacking for the optimal systemic therapy management of AIMSS. Examples of research into the management of other musculoskeletal conditions include reviews on glucosamine therapy for osteoarthritis (Towheed 2005), opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip (Da Costa 2014), and muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis (Richards 2012). Reviews such as these have enabled evidence‐based guidelines to be developed for the management of conditions such as osteoarthritis (NICE 2014). Systemic therapy approaches for AIMSS investigated by researchers have included interventions previously studied in osteoarthritis, rheumatological arthritis and chronic pain conditions (Hershman 2015b).

The exact cause of AIMSS remains unknown, but has been hypothesised to be related to multiple factors, including oestrogen deprivation, vitamin D insufficiency and the activation of molecules within the body that promote inflammation (Borrie 2017; Hershman 2015b). Of these, oestrogen deprivation appears to be the key mediator. Oestrogen has an effect on both inflammation and the neural processing of a painful stimulus, which could result in heightened pain in the setting of oestrogen depletion (Felson 2005). Researchers have also identified an association between AIMSS and various genetic variations in women, which may result in women being more susceptible to experiencing musculoskeletal toxicity from AIs (Borrie 2017; Lintermans 2016).

Risk factors that have been attributed to developing AIMSS include previous hormone replacement therapy (Sestak 2008), previous taxane chemotherapy (Crew 2007; Lintermans 2014), younger age (Kanematsu 2011; Lintermans 2014), fewer years since last menstrual period (Kanematsu 2011; Mao 2011), body mass index less than 25 or greater than 30 kg/m2 (Beckwee 2017; Crew 2007), severity of menopausal symptoms (Castel 2013), presence of joint‐related comorbidity at baseline (Castel 2013; Lintermans 2014), stage two breast cancer (Beckwee 2017), and fear of recurrence (Lopez 2015). However, clinicopathological associations have been inconsistent across studies (Beckwee 2017), except for time since last menstrual period (Kanematsu 2011; Mao 2009).

With only postulated causes of AIMSS, the interventions that have been investigated to date vary widely. Research interventions with systemic therapies have attempted to address various postulated causes of AIMSS, sometimes potentially via multiple complex and postulated pharmacological targets or pathways (or both).

Omega‐3 fatty acids (O3‐FA), as found in fish oil (particularly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have anti‐inflammatory properties (Hershman 2015a; Hershman 2015b), and have shown effect on pain and stiffness in inflammatory joint pain (Goldberg 2007). EPA and DHA inhibit conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandin and leukotrienes, reducing inflammation (Cleland 1988; Sundrarjun 2004). O3‐FA supplements have thus been investigated in AIMSS (Hershman 2015a; Lustberg 2015).

Other anti‐inflammatory systemic therapies have been investigated, including a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID), etoricoxib (Rosati 2011) and prednisolone (Kubo 2012). NSAIDS are utilised as part of the management strategy for osteoarthritis, with traditional NSAIDS inhibiting the cyclo‐oxygenase‐1 (COX‐1) enzyme (Song 2016). Etoricoxib is selective for the cyclo‐oxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inducible form of cyclo‐oxygenase, potentially improving the central hyperalgesic action (Song 2016). Rosati 2011 examined the effect of AI on musculoskeletal events as a secondary endpoint in a trial where the primary outcome was to investigate whether etoricoxib or placebo improved DFS in addition to adjuvant anastrozole in early breast cancer. Similarly, glucosamine with chondroitin has been investigated in AIMSS (Greenlee 2013). Chondroitin with glucosamine slightly improves pain in osteoarthritis (Singh 2015), with multiple postulated mechanisms of action in preclinical research, including anti‐inflammatory effects in joints and glucosamine increasing the synthesis of proteoglycans in articular cartilage (Greenlee 2013; Reginster 2012).

Oestrogen is thought to play a role in the modulation of nociceptive pain pathways (Felson 2005). With a higher incidence of autoimmune disease in women than men, hormonally active androgens are believed to be anti‐inflammatory and oestrogens are pro‐inflammatory (Schmidt 2006). The balance between oestrogen and androgen mediated by the AI enzyme is thought important in joint health (Schmidt 2006). Hence, testosterone has been investigated as it was hypothesised that this could improve AIMSS (Birrell 2009; Cathcart‐Rake 2020).

Duloxetine, as investigated by Henry 2018, is a serotonin‐noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) with antidepressant and analgesic properties (Bellingham 2010). The analgesic effect of duloxetine is postulated to be achieved by augmentation of the tone of the descending pain inhibitory pathways from the central nervous system (Bellingham 2010). Duloxetine is indicated for treatment of fibromyalgia, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain and chronic musculoskeletal pain (Lilly 2020), and has been investigated for management of AIMSS (Henry 2018).

Low vitamin D levels have been associated with higher levels of joint pain in postmenopausal women (Chlebowski 2011). Vitamin D deficiency has been found to be prevalent in women with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy (Crew 2009). Oestrogen activates both vitamin D and it's receptor (Gallagher 1980), with AIs causing a subsequent functional deficiency of vitamin D. As vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency can contribute to musculoskeletal symptoms (Hershman 2015b; Holick 2007), vitamin D supplementation for prevention and management of AIMSS has thus been investigated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Khan 2017; Niravath 2019; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016).

Calcitonin acts with parathyroid hormone and 1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol to regulate short‐term calcium homeostasis, mediated in part by inhibiting bone resorption by an effect on osteoclasts (Chesnut 2008). Salmon calcitonin has thus been used as an anti‐resorptive therapy in osteoporosis and other bone‐associated pain conditions (Chesnut 2008), and has been studied by Liu 2014.

Use of CAM is anecdotally widely noted by care providers and, therefore, reviewing the evidence of effect and toxicities is important (Boon 2000; Kremser 2008). Women with AIMSS may be unwilling to take medications with side effects to treat side effects, and hence may seek CAM as an alternative potential management strategy (Hershman 2015b).

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been widely used in care of people with cancer in China (Li 2013), and Chinese patients have sought out TCM practitioners due to lack of effective therapies for AIMSS (Peng 2018). Investigators have trialled various TCM for AIMSS (bionic tiger bone, Li 2017; Yi ShenJian Gu (YSJG) granules, Peng 2018; Blue Citrus capsules, Massimino 2011).

Tiger bone, whose "main ingredients are calcium and collagen", has been utilised in TCM for proposed strengthening of muscles and bones (Li 2017). However, as tigers are protected animals, "scientists adopted bionic research method to develop bionic tiger bone powder, which has similar ingredients to natural tiger bone"(Li 2017). "Bionic TB [tiger bone] powder has more than 20 kinds of amino‐acid and microelements essential to human. Besides, calcium to phosphorus ratio of TB makes it suitable for body to absorb, whereas it also contains various organic components, such as collagen, analgesic peptide, bone morphogenetic protein, bone growth factors, and polyose" (Li 2017). Li 2017 investigated bionic tiger bone powder for management of AIMSS because of proposed anti‐inflammatory, analgesic and anti‐osteoporotic effects.

YSJG granules, patented by the Beijing Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, are composed of an empiric formula of 12 herbs, including Radix rehmanniae Preparata (ShuDiHuang), Fructus Corni (ShanZhuYu), Semen cuscutae (TuSiZi), Radix Achyranthis Bidentatae (NiuXi), Rhizoma cyperi (XiangFu), Radix Angelicae Sinensis (Dang‐Gui), Poria (FuLing), Radix Paeoniae Alba (BaiShao), Rhizoma chuanxiong (ChuanXiong), Rhizoma corydalis (YanHuSuo), Phryma leptostachya (TouGuCao) and Caulis trachelospermi (LuoShiTeng) (Peng 2014). YSGJ granules have been used in TCM treatment of musculoskeletal symptoms of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and arthrosis based on TCM principles, and have been investigated for management of AIMSS (Peng 2018). "Because the formula for YSJG is currently being patented, the ingredients in YSJG cannot be published at this time" (Peng 2014), and therefore it is not possible to postulate on the proposed action of this intervention in AIMSS due to the large number and complexity of the ingredients, and the uncertainty arising from the lack of information on the ingredients with the pending patent.

Similarly, the TCM Blue Citrus has been investigated for AIMSS, due to anecdotal reports of improvements of AIMSS (Massimino 2011). According to the National Cancer Institute drug dictionary (NCI 2021), Blue Citrus is "An oral capsule formulation of a traditional Chinese herbal medicine with potential analgesic activity. In addition to other herbs, seeds and fruits, blue citrus‐based herbal capsule contains the Chinese herb blue citrus (qing pi), which is produced from the dried immature green peel of the tangerine Citrus reticulata Blanco. Blue citrus contains large amounts of limonene, citral and synephrine, which may attribute to its analgesic activity. However, due to the complexity of its chemical components, the exact mechanism of action of this agent remains to be determined".

Emu oil, obtained from the fat of emus, a large bird indigenous to the Australian continent, has been used by Australian Aboriginal people as a traditional medicine (Turner 2015; Whitehouse 1998). The liquid fat was applied topically by Aboriginal people for musculoskeletal disorders and to assist wound healing (Turner 2015; Whitehouse 1998) with transdermal absorption considered to be anti‐inflammatory in rat models of arthritis (Whitehouse 1998). There were anecdotal evidence of effectiveness in osteoarthritis (Power 2004), and hence topical application for treatment of AIMSS has been investigated (Chan 2017). Emu oil "contains several fatty acids (myristic, palmitic, stearic, palmitoleic, oleic, linoleic, and linolenic), and it is not known which specific component provides symptomatic relief" (Chan 2017).

Uncaria tomentosa (Cat's claw) is a plant species found in the Amazon (Sordi 2019), and has been used for centuries by the Incas as a traditional medicine to treat arthritis, arthrosis and other inflammatory conditions. The active metabolites (including pentacyclic and indole oxindole alkaloids and quinovic acid glycosides) have reported antioxidant, immunomodulatory, antineoplastic, anti‐inflammatory and antiviral activities (Aguilar 2002; Aquino 1989; Sordi 2019). Sordi 2019 investigated the use of the dry extract of Cat's claw for women with AIMSS.

Cherries contain many bioactive compounds with reported health benefits (Kelley 2018). Flavonoids and anthocyanins in tart cherry extract reportedly reduce inflammation, and some clinical trials suggest improvement in joint pain in osteoarthritis and gout (Kelley 2018; Shenouda 2019). Shenouda 2019 investigated tart cherry extract in AIMSS.

As the cause of AIMSS remains unknown, it is important to further review the evidence for systemic prevention and management of musculoskeletal symptoms specific to AIMSS, rather than extrapolating evidence from other non‐AIMSS musculoskeletal conditions.

Why it is important to do this review

The high prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms secondary to AIs can result in detrimental outcomes for patients. Several studies have shown poor participant adherence to AI therapy (Brier 2017; Hadji 2014; Henry 2012; Hershman 2011; Partridge 2008; Presant 2007). This is particularly concerning in the setting of early breast cancer, where non‐compliance with hormonal therapies such as AIs, used in the curative setting, have been shown to be detrimental to patient survival (Hershman 2011). Given the prevalence of breast cancer in the community, the implications of the potential impact of non‐adherence on breast cancer outcomes are important.

While there has been a few reviews to assist clinicians with the management of AIMSS (Roberts 2017; Yang 2017), there have been no reviews dedicated solely to the systemic management of AIMSS. Several of the authors from this review have conducted a separate Cochrane Review entitled "Exercise therapies for preventing or treating aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms in early breast cancer" (Roberts 2020). There has been a meta‐analysis on acupuncture for AIMSS (Chen 2017). Identifying current evidence and potential areas for further research in this field is required for the optimisation of management of women with endocrine‐sensitive breast cancer.

Objectives

To assess the effects of systemic therapies on the prevention or management of AIMSS in women with stage I to III hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

RCTs examining the prevention or management of AIMSS in women with stage I to III hormone receptor‐positive breast cancer. AIMSS was defined by the study authors of each trial. We excluded animal and in vitro studies. We considered studies in all languages for inclusion.

Types of participants

Women with stage I to III oestrogen‐receptor (ER) or progesterone‐receptor (PR) (or both)‐positive breast cancer, being treated adjuvantly with AIs.

Types of interventions

Intervention: all systemic therapy interventions, including pharmacological therapies, dietary supplements, and CAM. We excluded acupuncture administered as a sole intervention as it was not considered a systemic therapy.

Comparator: all comparator groups were allowed, including placebo or standard of care (or both) with analgesia alone.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Symptoms of AIMSS (specifically pain, stiffness and grip strength) from baseline. These were preferably assessed by validated questionnaires, such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT‐G), Medical Outcome Study Short Form 36 (SF‐36) and the Modified Score for the Assessment of Chronic Rheumatoid Affections of the Hands (M‐SACRAH). These questionnaires identified participant symptoms including, but not limited to, pain (e.g. severity of pain, change in pain scores), physical function (e.g. using stairs, sitting up, performing domestic duties) and stiffness. These outcomes were assessed for both the impact on AIMSS immediately after the intervention, and in the long‐term, where available.

Safety of the intervention, including adverse effects. All grade of adverse events were considered from each intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Persistence and adherence of participants continuing to take their AI medication due to the intervention.

Patient health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), also preferably assessed by validated patient‐reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires. Where available, this was analysed for the impact on participants during the intervention, immediately after the intervention and in the long term.

Incidence of AIMSS.

Breast cancer‐specific survival (BCSS).

Overall survival (OS).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Information Specialist (KR) designed and conducted systematic searches in the selected databases and trial registries without language, publication year or publication status restrictions on 10 September 2020. Cochrane Breast Cancer's Information Specialist conducted the search of the Specialised Register on 27 March 2021. Where appropriate, the search strategies also included adaptations of the Highly Sensitive Search Strategy designed by the Cochrane Collaboration (Lefebvre 2011), and the search filter for CINAHL (EBSCO) created by Mark Clowes at SIGN for identifying RCTs and controlled clinical trials.

We searched the following databases and trial registries up to 10 September 2020.

CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library, 2020, Issue 8). See Appendix 1.

MEDLINE (via PubMed) from 1946. See Appendix 2.

Embase (via EMBASE.com) from 1947. See Appendix 3.

CINAHL (via EBSCO) from 1981. See Appendix 4.

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) for all prospectively registered and ongoing trials. See Appendix 5.

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/). See Appendix 6.

The following was searched up to 27 March 2021.

The Cochrane Breast Cancer Group's (CBCG's) Specialised Register. Trials with the keywords “breast cancer” and related terms, “aromatase inhibitors”, “exemestane”, “anastrozole”, “letrozole”, were extracted and considered for inclusion in the review.

Searching other resources

Adverse effects

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used for the treatment of AIMSS. We considered adverse effects in included studies only.

Searching within other reviews

We scanned the reference lists of existing systematic reviews relevant to this systematic review that the search identified, or reference/citation lists, for additional trials and to check robustness of search strategy.

Bibliographic searching

We identified further studies from reference and citation lists of identified relevant trials or reviews. We obtained a copy of the full article for each reference reporting a potentially eligible trial for those studies selected for full‐text review. Where this was not possible, such as with the inclusion of conference abstracts, we contacted the authors for additional information and reviewed additional information from clinical trial databases.

Grey searching

The San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) conference proceedings are included in the Embase database and, therefore, were not searched separately. See Electronic searches for searching of clinical trials databases.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

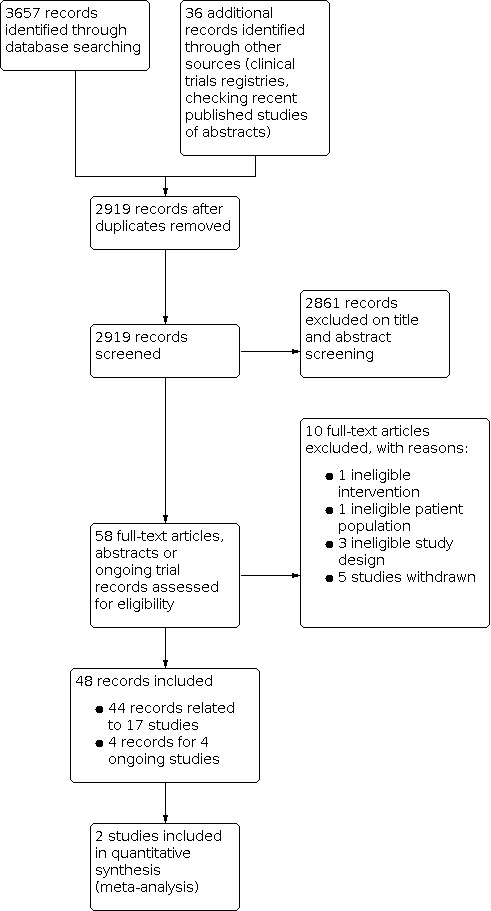

Two review authors (KER and NW) screened and retrieved abstracts from the literature search to assess whether they met the specified selection criteria. Subsequently, two review authors (KER and NW) reviewed full‐texts of all remaining studies, ensuring they still met the selection criteria. Any disagreements on study selection were resolved by a separate review author (IA or SC). The selection process was recorded in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). We documented the reason for excluding studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Clinical trials that were terminated are detailed as Excluded studies, and those that are ongoing and awaiting publication, are included in the Studies awaiting classification table.

1.

Study flow diagram.

No studies required translation from other languages.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (IA, SC, NW) used a standardised data extraction form and collected the following information. A fourth review author (KER) resolved disagreements.

Characteristics of the study

Study sponsors and author affiliations.

Study funding.

Methods, including study design, method of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome, participant attrition and exclusions, and selective outcome reporting.

Full‐text available versus abstract only.

Characteristics of the study population

Country of enrolment.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Study definition of AIMSS.

Number of participants in each treatment arm.

Mean and range of participant ages.

Number of participants aged less than 40 years; aged 40 to 60 years; and aged greater than 60 years.

Menopausal status (i.e. requirement for biochemical ovarian suppression versus no requirement).

Previous use of taxane (yes/no).

Type of AI prescribed, and time since commencement of AI.

Characteristics of the intervention

Description of the intervention.

Details of control group.

Ingredients of placebo, if applicable.

Compliance with intervention.

Safety.

Characteristics of the outcomes

Scoring systems used (and documentation of PRO versus investigator‐reported outcomes).

Outcomes of pain, stiffness, functioning and HRQoL.

Timing of outcome data collection, including length of time between intervention and last collected outcome measurement.

Follow‐up period.

Two review authors (IA and NW) entered the data into Review Manager Web (Review Manager 2014). Where there was more than one publication for a study, the data was extracted from all publications as required, but the most recent version of the study was considered the primary reference. Where possible, records relating to the same study were combined under an overall trial name or study.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (of NW, SC or IA) independently assessed risk of bias for all RCTs using the Cochrane's risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011a). A third review author (KR) resolved any disagreements. This tool included seven specific domains: random sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of outcome assessment; blinding of participant and personnel; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting and other sources of bias. Each risk of bias domain was assessed as high risk, low risk or unclear risk. For risk of bias for cross‐over RCTs, we referred to guidance in Chapter 23 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011b).

Where there was incomplete reporting of a study's conduct, we attempted to contact the study authors to clarify such uncertainties. Risk of bias tables for each study were presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. Risk of bias domain‐level judgements were presented in forest plots, and a summary table listing the risk of bias judgement for all studies is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias domain, for each included trial.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item, presented as percentages across all included trials.

Measures of treatment effect

It was expected that studies would use a variety of different tools to measure the outcomes of interest (pain, stiffness, grip strength and HRQoL) and mostly report continuous outcomes. Because of the clinical heterogeneity of the included studies, a random‐effects model was considered.

The measurement of the treatment effect was performed using a mean difference (MD) analysis. This is different from our protocol, which we had intended to measure the treatment effect by performing a standardised mean difference (SMD) analysis and the random‐effects model to combine data from different scoring systems measuring the same outcome of interest. But, due to inconsistent reporting of standard deviations (SD), with some studies reporting only 'end‐of‐treatment' SD and others reporting only 'change score' SD, we were unable to combine these results for the calculation of SMD. Multiple studies did not report SD of change scores and only provided SD from baseline or end‐of‐treatment SD. If change score means with SD were not available, we reported end‐of‐treatment means and SD for both groups. As discussed in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, "in a randomized study, MD based on changes from baseline can usually be assumed to be addressing exactly the same underlying intervention effects as analyses based on post‐intervention measurements" (Deeks 2021). If end‐of‐treatment means and SD were used, this was highlighted in the analysis.

If SDs could not be obtained for studies, imputing the SD was attempted as per Chapter 6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). In studies where only CIs were available, we used the following formula to determine the SD: SD = √n × (upper limit 95% CI − lower limit 95% CI)/2 × T value calculated by the T distribution), where n was the sample size and CI was the confidence interval. We estimated appropriate T values for smaller sample sizes using the TINV function (TINV(1‐0.95,n‐1)) in Excel. If the standard error (SE) was reported instead of SD, then SD was calculated with the following formula, SE = SD × √n, as per guidance from Chapter 6 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021). One study reported the use of mean and SD, but the data were more consistent with the reporting of median values and interquartile ranges (IQR) (Liu 2014). Reporting the median is often an indicator that the data are skewed, so it should be incorporated into a meta‐analysis with caution (Higgins 2021). To calculate SD from IQR, we used the following formula: SD = (q3‐q1)/1.35, where q3 is quartile 3 and q1 is quartile 1 (Higgins 2021).

If studies reported dichotomous outcomes (e.g. incidence rates), the treatment outcome was measured by the risk ratio (RR), in combination with a 95% CI. We reported the ratio of treatment effect so that RR less than 1.0 favoured the intervention group for relief of AIMSS symptoms and RR greater than 1.0 favoured the control group.

The most appropriate time point across all studies for each outcome depended on the availability of suitable data. As recommended in Section 16.7.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, we avoided multiple testing of the treatment effect at each time point (Higgins 2011c). We collected data on the treatment effect at baseline, immediately following the intervention and long‐term data, if available. The only study that we did not use end‐of‐treatment outcomes was Rastelli 2011. Instead, we utilised outcome data at two months to eliminate any differences in the stratums in the intervention arm, which received differing doses of intervention between two and four months of the study.

Unit of analysis issues

There were two studies that would have created unit of analysis issues, including one study with a cross‐over trial design (Massimino 2011), and one study with multiple treatment arms (Birrell 2009). However, both studies were only published in abstract form without pursuing full publication. We were unable to obtain information or data from either of the study authors by correspondence, and, therefore, did not have adequate data to analyse the results. Our planned approach for unit of analysis issues that were not utilised in this review can be found in our protocol (Roberts 2018).

Dealing with missing data

In the case of missing data, we attempted to contact the study authors to source additional information through clinical trial registries or data repositories. If the required data were still not available, we contacted original investigators via email and gave three weeks to reply to the request. If the corresponding authors did not reply, we attempted further contact with the original investigators and either the first or last author of each paper (if not the primary corresponding author).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, Chi2 test and visual inspection of forest plots, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). An I2 statistic of 30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity, a result of 50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity and a result of 75% to 100% may represent considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011a). The importance of the I2 statistic depended on the magnitude and direction of effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity. For the Chi2 test, we used P < 0.1 to indicate significant heterogeneity. We planned to use both a random‐effects model and a fixed‐effect model for analysis of results of meta‐analysis, but there were only two studies combined for meta‐analysis of one outcome, and there was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity; therefore, fixed‐effect and random‐effects models did not need to be compared.

Assessment of reporting biases

We included one funnel plot in the assessment of reporting biases for the outcome with the largest number of studies. We could not undertake any further assessments due to the small number of studies contributing data to each outcome (fewer than 10 studies).

Data synthesis

We used Review Manager Web to perform statistical analysis (Review Manager Web 2021). We assessed analyses for clinical heterogeneity (see Assessment of heterogeneity). We performed a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis using the inverse variance method to combine data results for one outcome where at least two studies were appropriate to be combined for meta‐analysis. We reported the meta‐analysis using a forest plot and in the summary of findings table.

There needed to be sufficient data available for meta‐analysis between studies. If there were insufficient outcome data, we attempted to contact authors for additional data. If there were insufficient studies, or where the data could not be combined due to insufficient data for comparison, we presented the findings in a narrative manner.

To enable synthesis of our outcomes where meta‐analysis could not be done for the majority of outcomes, we applied the vote‐counting method as detailed by McKenzie 2021. We used vote‐counting by reporting continuous outcomes as the number of studies that showed a treatment effect that included a clinically significant benefit within the CIs of the MD between studies as determined by reported minimal clinically importance difference (MCID) for that outcome scale, compared to the number of studies that did not include an MCID within the CIs of the treatment effect. The MCID is a change in score that has been determined to represent a meaningful change in quality of life.

For binary outcomes, we reported RR as per our initial protocol. There were no trials with binary outcomes that reported zero events in both arms.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not undertake any subgroup analyses, as there were insufficient studies and participants to undertake any meaningful subgroup analysis within this review. Our planned subgroup analyses can be found in our protocol (Roberts 2018).

Sensitivity analysis

There were not enough studies of each intervention in our review to undertake meaningful sensitivity analyses. Our planned sensitivity analyses can be found in our protocol (Roberts 2018).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used GRADEpro GDT software to present summary of findings tables to illustrate the main outcomes and grade the certainty of the evidence. We assessed the level of evidence using the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias) as per the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Schünemann 2021). At least two review authors (KR, IA) independently assessed the evidence using the GRADE technique, and a third review author (NW) resolved any disputes.

Main outcomes in the summary of findings tables: prevention studies

Change in pain from baseline to end of intervention (symptoms of AIMSS)

Adverse effects secondary to the intervention (safety data)

Change in grip strength from baseline to end of intervention (symptoms of AIMSS)

Effect on discontinuation of AIs

Effect on BCS‐QoL

Effect on HRQoL

Change in incidence of AIMSS.

Main outcomes in the summary of findings table: treatment studies

Change in pain from baseline to end of intervention (symptoms of AIMSS)

Change in stiffness from baseline to end of intervention (symptoms of AIMSS)

Overall change in grip strength (symptoms of AIMSS)

Adverse effects secondary to the intervention (safety data)

Effect on BCS‐QoL

Effect on HRQoL

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search retrieved 3693 records from four databases (3350 records; see Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4 in Electronic searches), the Specialised Register (307 records), clinical trial registries and reference lists of included studies (36 records). Once duplicates were removed, there were 2919 records. We excluded 2861 records during title and abstract screening, and obtained the full text (where possible) of the remaining 58 records. At full‐text review, we excluded 10 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies table). We identified four ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table).

We included 17 studies reported in 44 references (see Characteristics of included studies table) and four ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table). The full details of our screening process is detailed in the study flow diagram (Figure 1).

Included studies

The review included 17 studies (see Characteristics of included studies table).

Thirteen studies investigated the treatment of AIMSS (Birrell 2009; Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Li 2017; Liu 2014; Massimino 2011; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Shenouda 2019; Sordi 2019), and all of these studies investigated at least one symptom of AIMSS as a primary outcome.

Four studies investigated the prevention of AIMSS (Khan 2017; Lustberg 2018; Niravath 2019; Rosati 2011). One of these studies investigated the five‐year event‐free survival (EFS) as a result of adding adjuvant etoricoxib versus placebo to adjuvant anastrozole, and examined the musculoskeletal events as a secondary outcome (Rosati 2011); another trial investigated adherence and tolerability as a primary outcome, and investigated pain as a secondary outcome (Lustberg 2018); the other two studies investigated prevention of AIMSS as a primary outcome (Khan 2017; Niravath 2019).

Ten studies enrolled participants in the USA (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Khan 2017; Lustberg 2018; Massimino 2011; Niravath 2019; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Shenouda 2019), three studies in China (Li 2017; Liu 2014; Peng 2018), two in Australia (Birrell 2009; Chan 2017), and one each in Italy (Rosati 2011) and Brazil (Sordi 2019). One trial used a multi‐arm study design (Birrell 2009), and another trial employed a cross‐over design (Massimino 2011).

Thirteen studies were published as full texts (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Khan 2017; Li 2017; Liu 2014; Lustberg 2018; Niravath 2019; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019), whereas four studies were published as an abstract or in poster form only (Birrell 2009; Massimino 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019). Author correspondence resulted in additional data information from four studies (Chan 2017; Khan 2017; Niravath 2019; Sordi 2019).

Population

This review included 2034 randomised participants in 17 studies. The sample sizes ranged from 37 to 299 participants.

Participant age ranges were from 27 to 83 years. Eight studies reported the mean age of participants, which ranged from 59 to 61.5 years (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Khan 2017; Liu 2014; Lustberg 2018; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019). Six studies reported the median age of the participants, which ranged from 56.9 to 64 years (Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Li 2017; Niravath 2019; Rosati 2011). Nine studies reported age ranges (Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Khan 2017; Li 2017; Lustberg 2018; Niravath 2019; Peng 2018; Rosati 2011; Sordi 2019). Three studies reported only in abstract/poster format provided no participant baseline characteristics data (Birrell 2009; Massimino 2011; Shenouda 2019).

Most participants were already receiving AI treatment at enrolment into the studies, except for the three prevention studies, which were investigating women commencing AI (Khan 2017; Niravath 2019; Rosati 2011). The prevention study by Lustberg 2018 included women with short duration (less than 21 days) of AI exposure. The treatment study by Li 2017 included women with a duration of AI treatment of less than one month, despite being designed to investigate the treatment of AIMSS. Six treatment studies reported the duration of AI therapy at baseline, with mean durations ranging from 47.9 weeks to 20.6 months (Henry 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019), and median durations reported as 1.2 years (Hershman 2015a) and 13.3 months (emu oil group) to 16.9 months (placebo group; Chan 2017). Inclusion criteria of note related to two of the vitamin D studies that required participants to have specific serum 25‐hydroxyvitamin D (25‐OHD) levels at baseline (Khan 2017; Rastelli 2011), particularly 25‐OHD levels of 40 ng/mL or less for Khan 2017 and between 10 ng/mL and 29 ng/mL for Rastelli 2011. Mean baseline 25‐OHD levels in the studies investigating vitamin D supplementation ranged from 22.5 ng/mL to 36.6 ng/mL (Khan 2017; Niravath 2019; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016).

Several studies excluded women with potentially confounding comorbid musculoskeletal conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia and connective tissue disorders (Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Li 2017; Lustberg 2018; Massimino 2011; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019), or specifically the use of COX‐2 inhibitors for arthritis (Rosati 2011). All studies excluded women with metastatic disease; however, one woman with metastatic breast cancer was randomised and included in the study by Liu 2014. Inclusion criteria for Lustberg 2018 was stage I to III breast cancer; however, one women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) only was randomised; however, DCIS was allowed in the inclusion criteria in the study by Sordi 2019 but only one participant with DCIS was enrolled.

Definition of aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms

Studies that included participants with AIMSS at baseline varied in their definitions of AIMSS. Most studies specified the requirement of arthralgia/myalgias or musculoskeletal symptoms to be related to the AI as an inclusion criterion, although the specific definition of AIMSS and the determination of the relationship to AI therapy varied markedly (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Li 2017; Liu 2014; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Shenouda 2019; Sordi 2019). Several of these studies specified a minimum pain score to qualify for inclusion (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Peng 2018; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019). Two other studies included women experiencing any joint symptoms while taking an AI (Birrell 2009; Massimino 2011), and one of these stipulated a minimum pain score to qualify for inclusion (Birrell 2009); however, both studies were reported in abstract form with minimal details.

Interventions

The interventions investigated for systemic therapy for AIMSS varied widely. These were:

one study on oral duloxetine for the treatment of AIMSS (Henry 2018);

one study on etoricoxib as part of an adjuvant trial with anastrozole, with musculoskeletal adverse effects as a secondary outcome (Rosati 2011);

four studies investigating vitamin D on AIMSS, either for prevention (Khan 2017; Niravath 2019) or treatment (Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016). The dose, scheduling and duration of vitamin D intervention varied substantially between these studies (Khan 2017; Niravath 2019; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016);

one study on calcitonin for the treatment of AIMSS (Liu 2014);

two studies investigated testosterone for treatment of AIMSS, either administered as a subcutaneous implant or as gel (Birrell 2009; Cathcart‐Rake 2020);

two studies investigated O3‐FA supplementation for AIMSS, one for prevention (Lustberg 2018) and one for treatment (Hershman 2015a). For Hershman 2015a, the O3‐FA intervention dose was 3.3 grams (g) per day; for Lustberg 2018 4.3 g per day;

-

six studies investigated a range of complementary medicines, all for the treatment of AIMSS (Chan 2017; Li 2017; Massimino 2011; Peng 2018; Shenouda 2019; Sordi 2019) covering:

one study on topical application of emu oil, a traditional medicine of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, massaged into joints, with possible anti‐inflammatory properties via local or systemic (or both) absorption (Chan 2017);

three studies on TCM (Li 2017; Massimino 2011; Peng 2018), which included bionic tiger bone powder (Li 2017), YSJG (Peng 2018) and Blue Citrus capsules (Massimino 2011);

one study on traditional Incan medicine Uncaria tomentosa (Cat's claw) administered as dry extract tablets (Sordi 2019); and

one study on tart cherry concentrate, added to water (Shenouda 2019).

Thirteen of the 17 studies were placebo controlled (Birrell 2009; Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Khan 2017; Lustberg 2018; Massimino 2011; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019; Sordi 2019). Seven studies described the placebo, in varying detail (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Lustberg 2018; Peng 2018; Sordi 2019). The control arm of the other studies included calcium carbonate daily orally (Li 2017), oral caltrate D 600 mg/day (Liu 2014), oral vitamin D3 800 IU daily (Niravath 2019), and oral vitamin D3 600 IU daily (Shapiro 2016). The duration of the intervention varied, from four weeks to two years.

The duration of follow‐up varied between four weeks and five years.

Excluded studies

The reasons for excluding studies are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Ten studies were excluded from the analysis. Most studies were not RCTs (four studies) or the studies were withdrawn/terminated early (three studies). One study had an incorrect participant population (women with chemotherapy‐induced arthralgia) and one had an incorrect intervention (local rather than systemic treatment).

Studies awaiting classification

There are no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

There are four ongoing studies (NCT02831582; NCT03865992; NCT04205786; UMIN000027481). See Characteristics of ongoing studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

Details of the risk of bias are available in the risk of bias tables in the Characteristics of included studies table.

We requested further information to clarify unclear risk of bias from 11 studies, which authors of four studies provided (Chan 2017; Khan 2017; Niravath 2019; Sordi 2019). We also requested further information from another five studies to clarify potential bias including those at high risk of bias from selective reporting; however, we received no responses. The risk of bias summary can be viewed in Figure 2 and risk of bias graph in Figure 3.

Allocation

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment

We judged six studies at unclear risk of selection bias because there was insufficient information to permit judgement about the adequacy of methods of random sequence generation or allocation concealment (Birrell 2009; Liu 2014; Massimino 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019; Sordi 2019). Four of these studies were published as abstract alone or in poster format and there was no further information (Birrell 2009; Massimino 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019). One study had insufficient information available in the publication to permit judgement and no further information could be obtained by author correspondence (Liu 2014). One study had insufficient information available to permit judgement on methods of random sequence generation or allocation concealment, although author correspondence did provide additional information for this study (Sordi 2019).

Eleven studies were at low risk of selection bias for both methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Khan 2017; Li 2017; Lustberg 2018; Niravath 2019; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016). These 11 studies all described in sufficient detail methods to generate randomisation sequences that produced comparable groups, and adequate methods to conceal allocation.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

We judged three studies at high risk of performance bias (Henry 2018; Li 2017; Niravath 2019). One study was not blinded, with participants randomised to receive either oral vitamin D3 at 50,000 International Units (IU) per week for 12 weeks followed by 2000 IU daily for 40 weeks, or vitamin D3 at 800 IU daily for 52 weeks (Niravath 2019). A second study had differences in the dosing between the intervention (bionic tiger bone) and the control which could foreseeably have led to unblinding of participants and personnel (Li 2017). The third study examining duloxetine versus placebo found that more participants in the duloxetine group experienced adverse effects (78% with duloxetine versus 50% with placebo; Henry 2018). More participants in the duloxetine group compared with the placebo arm believed they were receiving duloxetine (79% with duloxetine versus 50% with placebo; P < 0.001). Likely due to adverse events experienced, it was foreseeable that participants and personnel were at risk of unblinding.

Five studies were at unclear risk of performance bias due to insufficient information available to permit judgement on measures used to blind participants and personnel (Birrell 2009; Liu 2014; Massimino 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019). We judged nine studies at low risk of performance bias due to effective blinding of participants and personnel (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Hershman 2015a; Khan 2017; Lustberg 2018; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019).

Blinding of outcome assessment

Most outcomes were PROs. We judged three studies at high risk of detection bias (Henry 2018; Li 2017; Niravath 2019). The primary outcomes for all three of these studies were PROs where participants were the outcome assessors. One of these studies had lack of blinding with outcome assessors, that is, participants, having knowledge of the assigned intervention (Niravath 2019). In two other studies, it was highly likely that participants, and therefore the outcome assessors, had potential knowledge of the assigned intervention (Henry 2018; Li 2017). Five studies were at unclear risk of detection bias (Birrell 2009; Liu 2014; Massimino 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019). There was insufficient information to permit judgement on measures used to blind the participants who were the outcome assessors in four of these studies (Birrell 2009; Liu 2014; Massimino 2011; Shenouda 2019), and insufficient information on blinding procedures related to personnel who were the outcome assessors in the remaining study (Rosati 2011). We judged nine studies at low risk of detection bias due to effective blinding of outcome assessors (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Hershman 2015a; Khan 2017; Lustberg 2018; Peng 2018; Rastelli 2011; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed seven studies at high risk of attrition bias (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Liu 2014; Lustberg 2018; Niravath 2019; Rastelli 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019). We based these judgements on high drop‐out rates of 20% or greater (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Lustberg 2018; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019; Niravath 2019), high proportional rates of exclusion from analysis with disparities between groups (Liu 2014), and a high drop‐out rate of 20% of greater and disparity in dropout rates between the intervention and control groups (Rastelli 2011). Two studies published in abstract/poster only were at unclear risk of attrition bias due to insufficient information to permit judgement (Birrell 2009; Massimino 2011).

We judged eight studies at low risk of attrition bias as handling of incomplete outcome data was adequately described and unlikely to have produced bias (Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Khan 2017; Li 2017; Peng 2018; Shapiro 2016; Sordi 2019).

Selective reporting

We judged two studies at high risk of selective reporting (Lustberg 2018; Rastelli 2011). One study of high‐ versus standard‐dose vitamin D reported an improvement in two‐month pain scores for the high‐dose group; however, the two‐month PRO pain outcome data scores did not appear to be a prespecified outcome on the trial registry (Rastelli 2011). The six‐month PRO outcomes were the registered primary outcomes. The positive effect of high‐dose vitamin D supplementation was not maintained at six months. The second study of O3‐FA compared to placebo reported safety and tolerability as the primary outcomes (Lustberg 2018); however, the trial registration listed pain score change after six months based on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Breast (FACT‐B) and Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment – Endocrine Symptoms (FACT‐ES) instrument as the primary outcome, and did not specify specifically safety and tolerability as secondary outcomes on the trial registry. No further information could be obtained by author correspondence.

Nine studies were at unclear risk of selective reporting (Birrell 2009; Khan 2017; Li 2017; Liu 2014; Massimino 2011; Peng 2018; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019; Sordi 2019). The reasons for judgement were as follows: insufficient information to permit judgement as study published only in abstract/poster form and no further information available (Birrell 2009; Massimino 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019), or insufficient information available in the publication to permit judgement and no further information able to be obtained (Liu 2014); at least one relevant missing unreported outcome among a very high number of planned outcomes in the protocol (Khan 2017); insufficient information whether certain outcomes had been analysed in accordance with a prespecified statistical plan (Li 2017); uncertainties about the time points for the primary outcomes with insufficient information available to permit judgement (Peng 2018); and inability to access the trial registry or statistical analysis plan to permit judgement (Sordi 2019).

We assessed six studies at low risk of selective reporting because these studies reported all of their proposed outcomes (Cathcart‐Rake 2020; Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Hershman 2015a; Niravath 2019), or only secondary/exploratory outcomes included in the initial trial registration were not reported in the study and these outcomes were not of relevance to our review (Shapiro 2016).

Other potential sources of bias

We judged two studies at high risk of additional bias due to authors holding patents for either the intervention itself (Birrell 2009), or for patents relevant to the intervention (Cathcart‐Rake 2020). Birrell 2009 was published only in abstract/poster form and no further information could be obtained by author correspondence.

Eight studies were at unclear risk of additional sources of bias (Hershman 2015a; Liu 2014; Lustberg 2018; Massimino 2011; Peng 2018; Rosati 2011; Shapiro 2016; Shenouda 2019). Four of these studies were deemed to be unclear risk due to insufficient information to permit judgement (Liu 2014; Massimino 2011; Rosati 2011; Shenouda 2019). Two of these studies were considered at unclear risk of contamination, due to the unclear exposure to O3‐FA in the placebo arm (Hershman 2015a; Lustberg 2018). Two studies had run‐in designs, whereby participants were provided with vitamin D (Shapiro 2016) or calcium and vitamin D supplementation (Peng 2018) prior to randomisation. The authors in one study stated the study was designed to mimic the high prevalence of the use of supplemental vitamin D among women with AIMSS (Shapiro 2016). As it was possible that vitamin D had a role in altering AIMSS in women with low 25(OH)D (less than 30 ng/mL), and this may have enhanced or diminished the effect of subsequent randomised intervention, these studies were judged at unclear risk of other bias (Peng 2018; Shapiro 2016).

We considered the remaining seven studies at low risk of additional sources of bias, as the introduction of possible bias was thought to be adequately assessed through the primary domains of bias consideration (Chan 2017; Henry 2018; Khan 2017; Li 2017; Niravath 2019; Rastelli 2011; Sordi 2019).

Effects of interventions

Prevention of aromatase inhibitor‐induced musculoskeletal symptoms

See Table 1.

Pain (from baseline to the end of the intervention)

See Table 3; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4.

1. Prevention studies: pain.

| Study | Intervention vs control | Treatment duration | Intervention | Control | ||||

| Baseline pain, mean (SD) | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | n | Change from baseline, mean (SD) | n | Outcome measure (scale) | |||

| Khan 2017 | Vitamin D3 30,000 IU weekly vs placebo | 24 weeks | 2.39 (2.34) | 0.8 | 67 | 0.86 | 72 | BPI worst pain (0–10) |

| Lustberg 2018 | Omega‐3 fatty acids vs placebo containing mixture of fats and oils typical of USA diet | 24 weeks | 1.1 (1.55) | 0.11 (1.88*) | 22 | −0.70 (1.88*) | 22 | BPI severity (0–10) |