Abstract

Sex determination is the process by which an initial bipotential gonad adopts either a testicular or ovarian cell fate. The inability to properly complete this process leads to a group of developmental disorders classified as disorders of sex development (DSD). To date, dozens of genes were shown to play roles in mammalian sex determination, and mutations in these genes can cause DSD in humans or gonadal sex reversal/dysfunction in mice. However, exome sequencing currently provides genetic diagnosis for only less than half of DSD patients. This points towards a major role for the non-coding genome during sex determination. In this review, we highlight recent advances in our understanding of non-coding, cis-acting gene regulatory elements and discuss how they may control transcriptional programmes that underpin sex determination in the context of the 3-dimensional folding of chromatin. As a paradigm, we focus on the Sox9 gene, a prominent pro-male factor and one of the most extensively studied genes in gonadal cell fate determination.

Keywords: 3D genome organisation, DSD, Enhancers, Ovary, Regulatory elements, Sex determination, Sox9, TAD, Testis

Introduction

When the first annotation of the human genome was published in 2003, one of the major insights was that neither genome size nor gene number can explain organismal complexity across the tree of life. This discovery has highlighted the crucial importance and complexity of gene regulatory processes operating at multiple levels in mammalian genomes. Among these processes, the timely and appropriate control of gene transcription relies on gene regulatory elements dispersed throughout the non-coding human genome − once famously discarded as “junk DNA”, the non-coding genome is now seen as a treasure trove of gene regulatory potential.

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project has revealed that in mammals ∼98% of the genome are non-coding, while only ∼2% represents protein-coding genes [ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012]. Attempts to assign function to this huge part of the genome that is non-coding are still ongoing today. Many of these elements are known to be transposons, non-coding RNAs (ncRNA), promoters, regulatory elements, and potentially other elements with yet unknown functions [ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012; Bhatti et al., 2021].

Extensive studies over the last 2 decades have revealed that the genome is organized into a higher order, non-random, 3D folding and that this organisation plays a crucial role in mediating appropriate gene expression [Sanyal et al., 2012; de Laat and Duboule, 2013; Spitz, 2016; Andrey and Mundlos, 2017]. In particular, developmental genes, which require precise and accurate control over their spatial and temporal expression, seem to be tightly controlled by complex gene regulatory mechanisms that include 3D genome organisation [de Laat and Duboule, 2013].

The sex determination process involves differentiation of an initial bipotential organ, termed the bipotential gonad/genital ridge, into either a testis or an ovary [Wilhelm et al., 2007]. This process is highly dependent on the delicate expression level control of several pro-male versus pro-female factors, and both gene activation and gene repression are crucially important [Lin and Capel, 2015]. The fact that less than half of human DSD cases can be attributed to mutations in protein-coding sequences [Eggers et al., 2016] points to a potential role of the non-coding genome in controlling the appropriate expression of key genes in sex determination.

Here, we will review recent advances in our understanding of how the non-coding genome contributes to spatiotemporal gene expression control. Different layers of genome organisation and structure will be described along with their functional roles and involvement in health and disease. We will discuss how gene regulatory elements control developmental gene expression in space and time, and which methods can be used to identify and classify them. We will then give an overview on mammalian sex determination and the process of testis and ovary differentiation and illustrate on specific examples of how cases of human DSDs have helped to decipher the molecular pathways and gene regulatory mechanisms that underpin sex determination. We will review what is currently known about the regulatory landscape of genes involved in sex determination, and more broadly, the role of 3D genome organisation in sex determination, with a focus on Sox9, one of the most intensively studied genes required for sex determination. We will conclude with a perspective on the emerging role of genome organisation during sex determination and DSD pathologies.

3D Genome Organisation

Layers of Genome Organisation

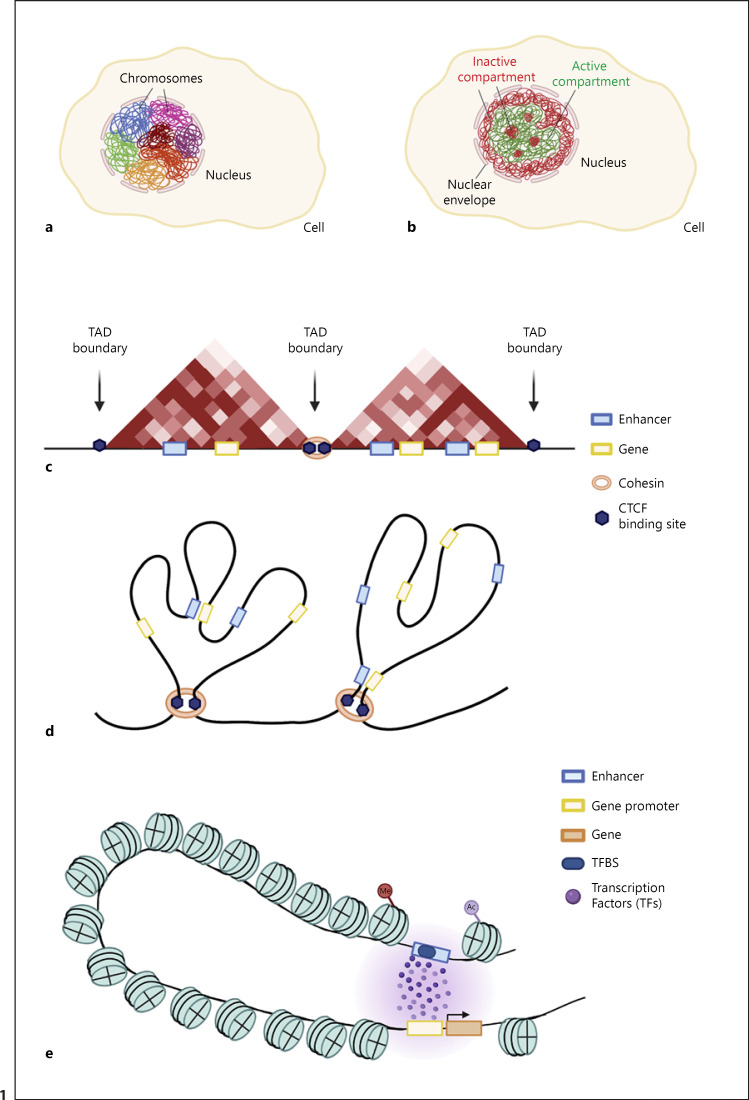

Textbook schematics and genome browsers sometimes depict genomes as linear structures which belies their 3D folding in the nucleus. Advances in microscopy approaches and biochemical techniques have shown that the genome is organized into large-scale subnuclear structures that occupy different areas of the nucleus. Within the nucleus, which is typically 2–10 μm in size, the DNA is packed into chromosomal territories that occupy preferential positions [Cremer and Cremer, 2010] (Fig. 1a). Additionally, the DNA is found in different functional states as euchromatin and heterochromatin [Misteli, 2020]. Hi-C, a genome-wide chromosome conformation capture (3C) technique [Dekker et al., 2002; Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009], has revealed that mammalian chromatin is spatially segregated into 2 sub-types: Type A compartments, which contain active DNA and are located towards the centre of the nucleus, and Type B compartments which mainly consist of inactive DNA and tend to localize at the nuclear periphery [Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009; Robson et al., 2019; Misteli, 2020] (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Organisation of the genome in 3 dimensions. a DNA is organised in the nucleus into chromosomal territories with each chromosome located in a specific location in a non-random fashion. b DNA within the nucleus is generally subdivided into 2 types of compartments: an active, Type A compartment, mostly localised at the centre of the nucleus, and an inactive, Type B compartment, mostly localised at the cell periphery termed the nuclear lamina/envelope. c Chromosomes are divided into megabase-scale units called Topologically Associating Domains (TADs). TADs are characterised by high levels of intra-TAD interactions and are separated by TAD boundaries over which interactions are relatively depleted. These boundaries are enriched for CTCF binding sites. TADs usually contain several genes and their regulatory elements and can be identified using Hi-C techniques. d Within TADs, regulatory elements can be brought near their target genes via chromosomal loop formation. e DNA is wrapped around histones to form nucleosomes. Enhancers and gene promoters are characterized by an accessible/open DNA signature due to binding of transcription factors at their target sites. Histone tails can undergo post-translational modifications including acetylation, phosphorylation, and methylation; this can attract or repel specific chromosomal proteins, thereby directly affecting genome function.

A more in-depth investigation of Hi-C interaction maps uncovered that the genome is further organized into megabase-scale units called topologically associating domains (TADs) [Dixon et al., 2012; Nora et al., 2012; Sexton et al., 2012]. TADs are characterised by preferential intra-domain chromosomal interactions and are separated by boundaries over which interactions are depleted (Fig. 1c). Within TADs, regulatory elements such as enhancers are thought to interact with their target promoters via loop formation to control gene expression levels [Andrey and Mundlos, 2017; Robson et al., 2019] (Fig. 1d, e). Furthermore, the DNA itself is wrapped around histones to form nucleosomes as a first layer of compaction; how chromatin is organised into higher-order structures is less well understood. Modifications such as DNA methylation or the post-translational modification of histones at specific residues can create binding sites for chromosomal effector proteins to catalyse enzymatic reactions that mediate transcriptional control, for example through changes in the positioning of nucleosomes or by creating specialised sub-nuclear microenvironments that favour gene activation or repression.

We will first describe the different layers of 3D genome organisation (compartments, TADs, promoter-enhancer contacts) and discuss how they control spatiotemporal gene expression patterns in mammalian development.

TADs: Gene Regulatory Building Blocks of the Genome?

TADs are megabase-sized chromatin domains that display a high level of intra-domain interactions demarcated by boundaries which have been proposed to inhibit regulatory crosstalk, for example between a promoter located in one TAD and an enhancer in the neighbouring TAD [Dixon et al., 2012; Nora et al., 2012]. Thus, mammalian genomes appear to be folded into adjacent globular interaction domains (the TADs), which are spatially separated by boundaries [Beagan and Phillips-Cremins, 2020]; however, how important this 3D organisation is for proper gene expression control is an area of intense debate and research focus (see below). TADs and their boundaries were shown to be relatively stable across different cell types and even between different organisms [Dixon et al., 2012, 2015; Nora et al., 2012]. While most interacting promoter-enhancer pairs are located within the same TAD [Shen et al., 2012], additional mechanisms seem to operate at the sub-TAD level to ensure appropriate enhancer-promoter contacts.

How are TADs formed? The zinc finger transcription factor CTCF and the cohesin protein complex were shown to play a critical role in TAD formation through a process termed loop extrusion [Fudenberg et al., 2016, 2017; Rowley and Corces, 2018]. According to the loop extrusion model, cohesin complexes extrude chromatin until it encounters CTCF binding sites in convergent orientation, hence generating a loop that brings 2 remote DNA elements into spatial proximity [Davidson et al., 2016, 2019; Hansen et al., 2017; Davidson and Peters, 2021] (Fig. 1d, e). As a result, TAD boundaries are enriched for CTCF binding sites [Fudenberg et al., 2016, 2017; Rowley and Corces, 2018].

Several studies have depleted CTCF or cohesin from mammalian nuclei, and as expected, this results in significant weakening (CTCF depletion) or complete loss of TAD structures (cohesin depletion) [Haarhuis et al., 2017; Nora et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2017; Schwarzer et al., 2017; Wutz et al., 2017]. Using an auxin-inducible degron system in mouse embryonic stem cells, Nora et al., [2017] demonstrated that remarkably CTCF removal did not affect the spatial segregation into active and inactive genome compartments demonstrating that CTCF and TAD formation are not required for chromosome compartmentalization. Similarly, Rao et al. [2017] used an auxin-inducible degron system to remove RAD21, a core component in the cohesin complex, and demonstrated a rapid elimination of loop domains and TAD structures. As with CTCF removal, acute cohesin depletion did either not affect compartment domains or even strengthened compartmentalisation [Schwarzer et al., 2017; Wutz et al., 2017]. When cohesin was restored experimentally by auxin withdrawal, many megabase-sized loops re-formed within an hour, indicating the loop extrusion is a rapid process [Rao et al., 2017]. However, surprisingly, and seemingly at odds with the postulated role of TADs as key gene regulatory 3D building blocks of the genome, the loss of TADs resulted in only very moderate gene expression changes [Rao et al., 2017; Schwarzer et al., 2017].

At first glance, these findings appear difficult to reconcile with several studies which explored cases of chromosomal aberrations including deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations. In several of these cases, chromosomal aberrations that affect TAD boundaries were shown to result in pronounced gene expression changes, leading to severe developmental diseases [Lupianez et al., 2015; Franke et al., 2016; Symmons et al., 2016; Kragesteen et al., 2018; Despang et al., 2019; Laugsch et al., 2019; van Bemmel et al., 2019].

An extensively studied regulatory genomic locus is the Sox9-Kcnj2 locus on mouse chromosome 11. Franke et al. [2016] modelled human patients' genomic duplication in mice and demonstrated that some of these duplications can lead to the formation of new chromatin domains called “neo-TADs”. Duplications at the Sox9-Kcnj2 locus that extended the TAD boundary and contained the Kcnj2 gene led to neo-TAD formation. Incorporation of the Kcnj2 gene in the neo-TAD resulted in misregulation of Kcnj2 by gene regulatory elements that normally control Sox9, leading to a limb malformation phenotype. Interestingly, removal of all major CTCF binding sites at the Sox9-Kcnj2 TAD boundaries and within the TAD itself led to fusion with adjacent TADs, but no major effect on gene expression was observed. In contrast, inversions or re-position of TAD boundaries resulted in major gene dysregulation and disease phenotypes [Despang et al., 2019].

Another paradigm locus for complex gene regulation is the X-inactivation centre (Xic) locus, located on the X chromosome, which contains the 2 non-coding genes Xist and Tsix [Nora et al., 2012; van Bemmel et al., 2019; Galupa et al., 2020]. This locus mediates the initiation of X chromosome inactivation (XCI) by tightly controlling the expression of Xist. As this locus consists of 2 TADs, the authors explored the outcome of genomic inversions that swap the Xist/Tsix transcriptional unit and place each gene promoter in the opposite TAD. This inversion led to a switch in the genes' expression pattern, with Xist being upregulated in both male and female pluripotent cells while Tsix expression aberrantly continued during differentiation [van Bemmel et al., 2019]. Later work demonstrated that Xist is also regulated by sequences located in the neighbouring TAD, the Tsix TAD, within a non-coding RNA called LinxP. When LinxP was introduced into the same TAD as Xist, it switched to act as an enhancer rather than a silencer [Galupa et al., 2020]. This demonstrated the importance of TAD partitioning and structures in regulating proper gene expression during development.

It is important to note that the mild gene expression changes upon cohesin or CTCF removal were mainly observed in vitro under controlled cell culture conditions [Haarhuis et al., 2017; Nora et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2017; Thiecke et al., 2020]. Notably, the inflammatory response is impaired in macrophages in the absence of cohesin or CTCF [Cuartero et al., 2018; Stik et al., 2020], and cohesin is required for neuronal maturation [Calderon et al., 2021]. Therefore, in specific developmental contexts and in response to some environmental signalling cues, when spatial and temporal expression levels of key genes are critical, TAD disruption can have pronounced effects, including impaired transcriptional responses and developmental disorders [Lupianez et al., 2015; Franke et al., 2016; Symmons et al., 2016; Kragesteen et al., 2018; Despang et al., 2019; Laugsch et al., 2019; van Bemmel et al., 2019]. Thus, TADs may be required to enable transcriptional precision and robustness but are not essential for gene regulation in general [Ibrahim and Mundlos, 2020]. TADs may also have provided a genomic environment in which regulatory elements have accumulated over evolutionary time [Williamson et al., 2019].

Enhancers and Silencers: Fine-Tuning Spatiotemporal Gene Expression Patterns during Development

Enhancers are classically defined as cis-acting short stretches of DNA (normally 500–1,500 bp) that are highly enriched in transcription factor-binding sites and increase the expression of target genes. Dispersed throughout the genome, enhancers function in an orientation-independent manner and can be located upstream or downstream of the genes they control, sometimes bridging distances that can span hundreds of kilobases and bypassing more proximally located genes. The predominant model of enhancer function postulates that enhancers regulate their target genes by DNA looping that results in direct contacts between enhancers and their target gene promoters [Schoenfelder and Fraser, 2019]. However, some enhancers appear to control gene expression without engaging in physical contacts [Alexander et al., 2019; Benabdallah et al., 2019].

It has been estimated that hundreds of thousands of enhancers exist in the human genome, vastly outnumbering the about 22,000 genes [ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012]. Even with the caveat that the functional annotation of enhancers is still ongoing, the abundance in the human genome indicates that enhancers are crucially important non-coding regions for genome control.

Silencers are the repressive and much less studied counterparts of enhancers; they function as gene regulatory elements that reduce target gene transcription [Segert et al., 2021]. Like enhancers, silencers are enriched in disease-associated genetic variants. However, despite several recent genome-scale approaches to annotate silencers in mammalian genomes [Huang et al., 2019; Doni Jayavelu et al., 2020; Ngan et al., 2020; Pang and Snyder, 2020], key aspects of silencer function remain poorly understood. A unifying chromatin signature (comparable to H3K27ac for active enhancers) has not (yet) been identified, whether silencers regulate their targets genes via chromatin looping is controversial, and how regulatory variation affects silencer function is not clear [Segert et al., 2021]. Interestingly, a recent study found that Drosophila mesoderm silencers function as enhancers in other cellular contexts [Gisselbrecht et al., 2020]. It will be interesting to unravel the molecular underpinnings of this regulatory element mode switch and to determine if this bifunctionality is also a general feature of mammalian silencers [Galupa et al., 2020].

Methods Used to Identify and Test the Function of Regulatory Elements

Bespoke methods have been developed to identify enhancers, assess their function, and to link them to their target genes. An “open” chromatin state is a major hallmark of enhancers, which stems from enhancer-bound transcription factors. Hence, methods that assess chromatin accessibility are extensively used to delineate enhancers. Among these methods are DNaseI-Seq [Boyle et al., 2008; Thurman et al., 2012] and ATAC-Seq [Buenrostro et al., 2013; Klein and Hainer, 2020]. DNaseI-Seq uses the non-specific DNA endonuclease DNaseI, which preferentially cleaves naked DNA devoid of proteins, followed by deep sequencing [Boyle et al., 2008; Thurman et al., 2012]. ATAC-Seq (assay for transposase accessibility and deep sequencing) employs the hyperactive Tn5 transposase to insert sequencing adapters into open chromatin regions followed by next-generation sequencing [Buenrostro et al., 2013; Klein and Hainer, 2020]. A major advantage of ATAC-Seq over DNaseI-Seq is the markedly reduced number of cells required (50,000 cells for ATAC-Seq compared to millions in DNaseI-Seq). Although DNaseI-Seq and ATAC-Seq are highly sensitive, not all the identified accessible sites in the genome are enhancers, and hence other methods are needed for further refinement and validation [Spitz, 2016].

Enhancers are enriched in specific post-translational histone marks which can be detected using Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Sequencing techniques (ChIP-seq) [Heintzman et al., 2009; Visel et al., 2009; Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011; Spitz, 2016]. It was shown that active enhancers are enriched in monomethylation of histone H3 at lysine 4 (H3K4me1) as well as acetylation of histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27ac). In contrast, “poised enhancers” are enriched in histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and devoid of H3K27ac [Rada-Iglesias et al., 2011].

The above-described methods are used to identify and classify putative enhancers based on specific characteristics such as DNA accessibility and presence of specific histone marks. Yet, these methods cannot determine whether an enhancer is indeed able to induce expression in vivo. A widely used method to interrogate enhancer function are transgenic reporter mice [Banerji et al., 1981]. In this method, which is considered the gold standard, a putative enhancer is cloned upstream of a minimal promoter and a reporter gene (β-galactosidase/fluorescent protein) and the construct is injected into the zygote of mice. Upon random incorporation into the genome, one can assess reporter gene expression in a specific tissue and at a defined developmental timepoint to examine the ability of a putative enhancer to activate gene expression both spatially and temporally in vivo [Spitz, 2016]. Recently, a high-throughput, in vivo site-specific reporter assay was developed to measure the pathogenic potential of numerous human enhancers linked to polydactyly [Kvon et al., 2020]. A major advantage of this approach is that it eliminates the effects of different genomic integration sites on enhancer-driven reporter gene expression.

CRISPR genome editing makes it possible to delete putative enhancers from their endogenous genomic locations to assess their functional roles in vitroor in vivo [Lopes et al., 2016; Dickel et al., 2018; Gonen et al., 2018; Osterwalder et al., 2018]. This method is increasingly used to measure enhancer activity but also to manipulate critical elements in the genome, including TF binding sites, CTCF binding sites, and other structural elements [Lopes et al., 2016].

Lastly, a major challenge is to identify the target gene(s) that enhancers regulate. Traditionally, many studies have linked regulatory elements to the nearest gene. However, enhancers can regulate and interact with target genes located at considerable genomic distances (in some cases hundreds of kilobases). A study in human cell lines showed that as few as 7% of total looping interactions are between an element and the nearest promoter, indicating that many enhancers may not regulate their nearby gene [Sanyal et al., 2012]. Chromosome conformation capture (3C), and related approaches including 4C, 5C, and Hi-C, map DNA regions in close spatial proximity, including contacts between enhancers and promoters [Dekker et al., 2002; Dostie et al., 2006; Simonis et al., 2006; Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009]. 3C provides information on how one specific region interacts with another known region (“one to one”) [Dekker et al., 2002]. 4C captures all the interactions of one specific “bait” region with the rest of the genome (“one to all”) [Simonis et al., 2006], 5C maps interactions within a defined genomic region at high resolution (“many to many”) [Dostie et al., 2006], while Hi-C captures all interactions within the entire genome (“all to all”) [Lieberman-Aiden et al., 2009]. The main principle of the C-family techniques is that cells first undergo fixation to “freeze” 3D genome architecture. Next, the genome is being digested into small fragments using restriction enzyme (or alternatively using micrococcal nuclease in Micro-C [Hsieh et al., 2015], followed by a ligation step which creates hybrid molecules composed of interacting genomic regions that can be identified by PCR or massively parallel sequencing. As the number of interactions between genomic regions in the genome is enormous (estimated 1010−1011 interaction products in mouse or human Hi-C libraries) [Belton et al., 2012], specific chromosomal interactions between genomic regions, such as between promoters of enhancers, cannot be reliably identified from Hi-C libraries unless they are sequenced to extreme depths. To circumvent this limitation, techniques to enrich 3C [Hughes et al., 2014] or Hi-C [Mifsud et al., 2015; Sahlen et al., 2015; Schoenfelder et al., 2015] libraries have been developed to enrich for specific interactions. In Promoter Capture Hi-C (PCHi-C) [Mifsud et al., 2015; Schoenfelder et al., 2015], a library of ∼40K biotinylated RNA probes with sequence complementarity to the ends of promoter-containing restriction fragments is used to isolate Hi-C ligation fragments containing promoters, enabling the genome-scale identification of enhancer-promoter interactions with statistical significance.

Functions of Enhancers during Development

ChIP-seq approaches have identified tens of thousands of tissue-specific enhancers, but it is the detailed study and functional dissection of a handful of enhancers that have shaped our understanding of enhancer function in health and disease.

One of the most extensively studied developmental enhancers is the ZRS enhancer of the Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) gene. The Shh gene is expressed in multiple tissues during development, including at the zone of polarizing activity (ZPA), which is critical for the establishment of the developing limb [Lettice et al., 2003]. Shh expression was shown to be regulated by several tissue-specific enhancers spanning a region of 900 kb [Lettice et al., 2003; Sagai et al., 2005]. However, Shh expression at the ZPA specifically is fully dependent on the activity of a single enhancer, the ZRS enhancer, which lies 850 kb away from the Shh promoter and within the intron of the unrelated Lmbr1 gene [Lettice et al., 2003]. Deletion of the ZRS enhancer abolished Shh expression in the limb bud and led to truncation of the mouse limbs [Sagai et al., 2005]. Shh and its diverse enhancers are found within the same TAD, with Shh and ZRS located close to the TAD boundaries [Anderson et al., 2014]. Interestingly, using engineered chromosomal rearrangements, Symmons et al. [2016] showed that altering the distance between the ZRS enhancer and the Shh promoter within the Shh TAD does not affect Shh expression. In contrast, inversions that led to disruptions of TAD borders resulted in modified 3D chromosomal folding in the region and prevented regulatory contacts. However, another study found that Shh expression was remarkable resistant to genomic rearrangements in its TAD − deletion of CTCF sites and TAD boundary perturbations did not affect Shh expression. In fact the only genomic rearrangements that had an impact on Shh expression were those that affected ZRS enhancer integrity [Williamson et al., 2019]. Thus, even in one of the model loci of enhancer-promoter long-range gene expression control, conflicting results indicate that there is more to be understood and discovered.

A single gene (as is often the case for developmental genes) can be regulated by multiple enhancers, which can act in a redundant, additive, or synergistic manner [Choi et al., 2021; Kvon et al., 2021]. Two studies interrogated conserved enhancers and showed high degree of enhancer redundancy also termed as “shadow enhancers” [Dickel et al., 2018; Osterwalder et al., 2018]. Osterwalder et al. [2018] generated 23 mouse lines containing single/combinatorial enhancer deletions at 7 loci required for limb development. Deletions of individual enhancers did not interfere with limb development; it was only when pairs of enhancers near the same gene were deleted that abnormal limb phenotypes started to appear. This strongly indicates that although several enhancers are extremely potent when acting alone [Sagai et al., 2005; Gonen et al., 2018], in most cases, a combinatorial effect of multiple enhancers regulating a single gene is needed [Osterwalder et al., 2018; Kvon et al., 2021].

Despite the impressive progress in deciphering 3D genome organisation and its effect on gene expression over the past decade, many questions remain to be addressed. For example, although we can identify putative enhancers by genome-wide approaches, it is currently impossible to predict from ChIP-seq data which enhancers have a functional role in regulating gene expression (see examples in the Vista Enhancer Browser: https://enhancer.lbl.gov/). In addition, we do not fully understand how a remote enhancer can find its target gene within a megabase-scale TAD, which usually contains multiple genes with sometimes vastly different expression levels. Furthermore, how the dynamics of enhancer-promoter contacts are translated into transcriptional outputs is still unclear [Zuin et al., 2021]. Several studies report that enhancers can control their target genes without engaging in physical contacts [Alexander et al., 2019; Benabdallah et al., 2019], but how these enhancers function at the molecular level remains to be elucidated. Another open question concerns the regulation of one gene by multiple enhancers (e.g., developmental genes). Do multiple enhancers contact their target gene at the same time in a multi-enhancer-promoter hub or do shadow enhancers operate in a stand-by mode and are only recruited once the main enhancer is not sufficient to maintain appropriate gene expression levels [Kvon et al., 2021]? Moreover, at the molecular level, how distal regulatory elements can induce or repress gene expression is not yet clear. At the level of 3D genome organisation, the role of TADs may be restricted to conferring transcriptional robustness to developmental gene expression programmes; but notably, there are regions in the genome which do not appear to be organised into TADs, and it is unclear which gene regulatory principles operate in these regions [Ibrahim and Mundlos, 2020]. Also, while most enhancer-promoter contacts occur within TADs, examples of gene regulation across TAD boundaries have been reported [Javierre et al., 2016; Galupa et al., 2020; Yokoshi et al., 2020]. In conclusion, it remains extremely difficult to predict how specific genomic rearrangements or mutations in non-coding elements will affect gene expression and hence development and disease.

Mammalian Sex Determination

Sex Determination and Gonad Development

The process of sex determination dictates whether an organism will develop as a male or a female. Although most organisms present with 2 sexes (males and females), the process of sex determination in different organisms has evolved in various ways. This process generally involves the differentiation of an initial bipotential organ into either a testis or an ovary, yet many types of genetic and/or environmental cues can control and modulate this process. For example, in many types of reptiles and fish, various environmental cues, among them temperature, can control the sex of the animal [Capel, 2017]. In mammals, sex determination occurs during embryonic development and is genetically driven by sex chromosomes with XY individuals developing as males and XX individuals as females.

The gonads, i.e., testis or ovary, develop from a common progenitor called the bipotential gonad/genital ridge, which starts to appear at embryonic day 10 (E10.0) in the mouse [Karl and Capel, 1998; Wilhelm et al., 2007; Maatouk and Capel, 2008; Nef et al., 2019]. The bipotential gonad consists of several bipotential progenitor cell populations. These include the supporting cell precursors which can differentiate into Sertoli (male) or granulosa cells (female), the steroidogenic cell precursors which can give rise to Leydig (male) or theca (female) cells, and the germ cells which can differentiate into spermatogonia or oogonia in the testis or ovary, respectively [Wilhelm et al., 2007; Maatouk and Capel, 2008; Nef et al., 2019]. Early somatic gonadal progenitors harbour a unique molecular signature with the expression of 3 key transcription factors [Wilhelm et al., 2007; Maatouk and Capel, 2008; Nef et al., 2019]: SF1 (Steroidogenic factor 1) [Luo et al., 1994, 1995], GATA4 (GATA Binding Protein 4) [Viger et al., 1998; Tevosian et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2013], and WT1 (Wilms' tumor 1) [Kreidberg et al., 1993; Vidal and Schedl, 2000]. Additional factors with key functions in these cells include M33 (CBX2) [Katoh-Fukui et al., 1998], FOG2 (Friend of GATA2) [Tevosian et al., 2002], LHX9 (LIM homeobox 9) [Birk et al., 2000], and EMX2 (Empty Spiracles Homeobox 2) [Miyamoto et al., 1997; Kusaka et al., 2010]. Mutations in these genes, in both human and mouse, result in defective gonad development [Bashamboo et al., 2017; Nef et al., 2019]. Recent single cell transcriptomic analyses [Maatouk and Capel, 2008; Stevant et al., 2018, 2019; Mayere et al., 2021] as well as ATAC-Seq experiments examining the regulatory landscape of early gonadal cells [Garcia-Moreno et al., 2019a] indicate that the genital ridge of both sexes is highly similar and sexual dimorphism starts to occur upon sex determination.

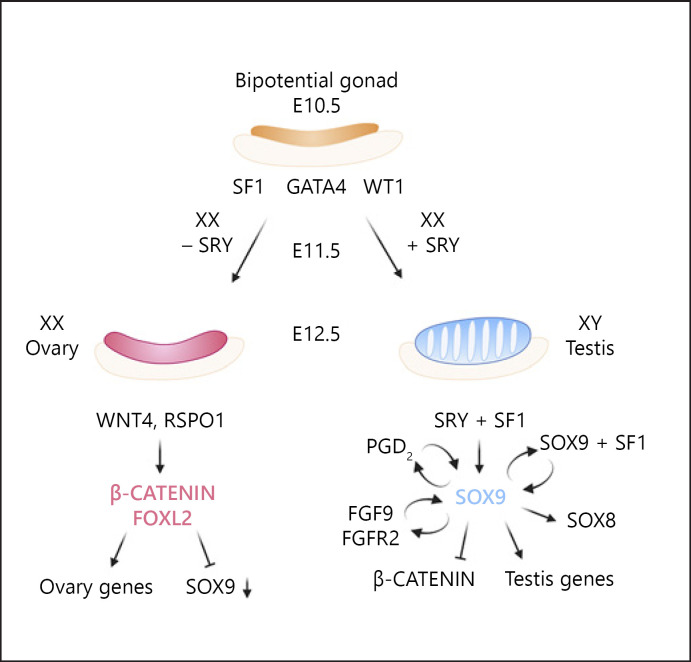

The bipotential gonad follows either a testicular or ovarian cell fate, depending on which transcription factors will be activated or repressed. Testis differentiation is initiated by the expression of the Y chromosome encoded gene Sry (sex determining region Y) which starts to be expressed at E10.5 and reaches a peak expression at E11.5 [Gubbay et al., 1990; Sinclair et al., 1990; Koopman et al., 1991; Hacker et al., 1995; Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2009]. SRY, together with SF1, activates the expression of Sox9 [Sekido et al., 2004; Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008; Gonen et al., 2018]. SOX9 is considered one of the key pro-male factors, and loss of SOX9/Sox9 in human and mouse causes XY female development [Foster et al., 1994; Wagner et al., 1994; Chaboissier et al., 2004; Barrionuevo et al., 2006; Gonen and Lovell-Badge, 2019]. Several positive feedback loops exist that maintain high expression levels of Sox9 throughout life in Sertoli cells, including SOX9 regulating its own expression by interacting with SF1 [Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008] as well as regulation via the PGD2(Prostaglandin D2) [Wilhelm et al., 2005] and FGF9 (Fibroblast growth factor 9)/FGFR2 (Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2) signalling pathways [Kim et al., 2006, 2007] (Fig. 2). Other important factors co-expressed with SOX9 in Sertoli cells include GATA4, WT1, SF1, FGF9, SOX8, and DMRT1. It is believed that SOX9, along with the other pro-male factors, is responsible for activating the male differentiation program while opposing the female program [Wilhelm et al., 2007; Maatouk and Capel, 2008; Nef et al., 2019] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cascade of events leading to mammalian sex determination. The gonads originate from a common precursor called the bipotential gonad. Several genes including wt1, Sf1, Gata4, and Lhx9 are expressed in early gonads and have been implicated in controlling their function. In mammals, males contain XY sex chromosomes, and the expression of the Sry gene, located on the Y chromosome, initiates testis development at E11.5. SRY acts with SF1 to upregulate the expression of Sox9. Several regulatory loops exist that maintain high levels of Sox9 expression throughout life in Sertoli cells. SOX9 is thought to activate Sox8 expression and other testis genes while repressing pro-female genes such as ß-catenin. Females contain XX sex chromosomes and thus lack the Sry gene. In the absence of SRY, the activity of RSPO1 along with WNT4 leads to stabilization of ß-catenin which, together with FOXL2, is believed to initiate the expression of ovarian genes while repressing pro-male genes such as Sox9.

Ovary differentiation on the other hand relies on the activity of other transcription factors and signalling pathways including the WNT4 (WNT family member 4)/RSPO1 (R-Spondin1) signalling pathway that leads to stabilization of the downstream effector ß-catenin [Vainio et al., 1999; Kim et al., 2006; Chassot et al., 2008; Maatouk et al., 2008], as well as the transcription factor FOXL2 [Schmidt et al., 2004; Uda et al., 2004; Ottolenghi et al., 2005; Boulanger et al., 2014]. It is thought that ß-catenin blocks Sox9 expression, leading to diversion into an ovary developmental path [Maatouk and Capel, 2008; Maatouk et al., 2008] (Fig. 2).

Genetic studies in which loss-of-function alleles of pro-male and pro-female factors were introduced together, for example, Wnt4/Fgf9 [Kim et al., 2006]; Sox9/Rspo1 [Lavery et al., 2012]; Sox9/Ctnnb1 [Nicol and Yao, 2015], and Sox9/Sox8/Rspo1 [Richardson et al., 2020], have strongly supported the concept that proper gonad development is achieved through a delicate balance of mutually antagonistic pro-male and pro-female factors.

Disorders of Sex Development

In human, similarly to mouse, sex determination is regulated via the tightly controlled gene expression and activity of several pro-male versus pro-female key TFs and signalling pathways. Alterations or disruptions of this balance can lead to a group of developmental abnormalities called disorders of sex development (DSD). DSDs are defined as congenital conditions where the chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomical sex is atypical. Overall, DSDs affect 1: 2,500–4,000 newborns and are considered common birth defects in humans [Hughes et al., 2006; Bashamboo et al., 2017]. It is important to note that a variety of causes can lead to DSDs, for example an imbalance of hormonal factors, and that only a subset of DSDs are due to genetic mutations affecting the sex determination path [Eggers et al., 2016]. DSDs are classified into chromosomal DSDs which include Turner syndrome (45,X), Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY) and others, as well as 46,XY DSD and 46,XX DSD [Bashamboo et al., 2017]. Genetic variants in many different genes have been implicated in DSD including SRY, WT1, SF1, SOX9, FOXL2, GATA4, CBX2 and many others [for a comprehensive review see Bashamboo et al., 2017]. To allow better disease management for patients, it is crucial to identify the causative variant. As many of the DSD causing variants are active in a heterozygous state, identifying the causative mutation can also allow parents with an affected DSD child to use assisted reproductive techniques coupled with pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) to screen future embryos for the presence of the DSD-causing variant. Yet, despite more than 3 decades of research, today many DSD patients remain without a clinical genetic diagnosis. Until recently, most patients were analysed using custom-made microarrays and the diagnosis rate was around 13% [Eggers et al., 2016]. Recent developments of a massively parallel sequencing targeted DSD gene panel as well as the use of exome sequencing enabled to increase diagnosis rate to ∼50% for 46,XY DSD but only ∼20% for 46,XX DSD [Baxter et al., 2015; Eggers et al., 2016; Tenenbaum-Rakover et al., 2021]. Yet, as more than 50% of DSD patients lack genetic diagnosis following exome sequencing, it is highly likely that many of the causing variants lie within the 98% of the genome that are non-coding, including regulatory elements such as promoters, enhancers, silencers, and possibly other elements that may affect proper gene expression as introns and 5′/3′ untranslated regions (UTRs).

In the following sections we will review what is known about the role of non-coding elements in regulating sex determination and DSD pathologies, a topic that is still in its infancy.

Genome-Scale Approaches to Define the Cis-regulatory Landscapes during Sex Determination

Recent studies from the Maatouk lab have provided the first datasets to start exploring the regulatory landscape present during the bipotential stage as well as in the testis and ovary. First, DNaseI-Seq was performed on E13.5 and E15.5 sorted Sertoli cells [Maatouk et al., 2017]. This approach identified over 81,000 gonad-specific DNaseI-hypersensitivity sites (DHS) at E15.5, many of which (71%) were shared between E13.5 and E15.5. In addition, H3K27ac ChIP-Seq identified >28,000 peaks, and 70% of these overlapped with the DHS in E13.5 Sertoli cells. In a later study, ATAC-Seq as well as H3K27ac ChIP-Seq were performed, this time on both XY and XX E10.5 SF1-GFP positive somatic progenitors as well as on purified Sertoli and granulosa cells at E13.5 [Garcia-Moreno et al., 2019a]. Using this approach, the authors showed that XY and XX progenitors at the bipotential stage present similar chromatin regulatory landscapes; only upon sex determination, the somatic cells acquire sex-specific regulatory landscapes. This notion was further supported by recent scRNA-Seq studies by the Nef lab [Stevant et al., 2018, 2019; Mayere et al., 2021]. Lastly, ChIP-seq on E10.5 XY and XX E10.5 SF1-GFP positive somatic progenitors as well as on purified Sertoli and granulosa cells at E13.5 was performed for the histone mark H3K27me3, which marks repressive or poised regulatory elements, and its counterpart H3K4me3, which marks active promoters [Garcia-Moreno et al., 2019b]. This work defined a role for CBX2, a subunit of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) in repressing ovary promoting pathways, mostly Wnt signalling, thereby stabilizing the testis fate [Garcia-Moreno et al., 2019b]. Together, these studies constitute rich and highly valuable datasets to explore regulatory elements that may function during sex determination.

Regulatory Elements Involved in Sex Determination

Extensive genetic and molecular studies have identified many genes, most of which encode TFs and signalling pathways molecules, that play a critical role during mammalian sex determination. For many of these genes, a tight control of spatiotemporal expression is crucial for normal development, and thus, many of the critical pro-male and pro-female factor genes are heavily regulated during the process of sex determination.

Cases of mutations or large genomic structural alterations such as deletions, duplications, translocations, or inversions have been described in DSD patients in genes well known to be involved in sex determination including SRY, SOX9, SOX3, SOX8, DMRT1, DAX1 and AR. Genomic alterations in FOXL2 have been described in goats in relation to sex determination (for a comprehensive review see [Baetens et al., 2017]). These mutations or genomic alterations can affect the function of regulatory elements such as promoters, insulators, enhancers, or silencers, or they can affect the chromosomal 3D conformation, resulting in, for example, enhancers acting on genes they are shielded away from during normal development (enhancer hijacking). This can cause misexpression of the target gene(s), either in the “wrong” developmental time window and/or in the “wrong” cell types, which in some cases can lead to DSD.

The mechanisms that control the spatiotemporal expression are incompletely understood for most genes encoding pro-male and pro-female factors, but our knowledge on gene regulatory control in the gonads is much more advanced for 2 key genes in sex determination: SOX9 and FOXL2. We refer the reader to an elaborate and up-to-date review on FOXL2 expression control by Migale et al., [this issue]. Here, we will summarize what is known about the complex regulation of Sox9/SOX9 in the gonads from both human DSD patients and mouse studies.

The Sox9/SOX9 Gene Regulatory Landscape

Arguably the most extensively studied gene in relation to its gonadal gene expression regulation is the Sox9/SOX9 gene [Baetens et al., 2017; Gonen and Lovell-Badge, 2019].

Like many developmental genes, Sox9 displays pleiotropic effects and is expressed in many tissues during embryonic development and in adults, including the brain, cartilage, testis, lung, pituitary, retina, and hair follicle [Jo et al., 2014]. Notably, the Sox9 gene is located within a gene desert encompassing almost 2 Mb, with the Kcnj2 gene located 1.7 Mb upstream of Sox9. Studies of multiple cases of human patients, including DSD patients, carrying large genomic rearrangements in this region, as well as studies in mice, indicate the presence of multiple tissue-specific regulatory elements that ensure proper spatiotemporal control of Sox9 expression [for comprehensive reviews see Baetens et al., 2017; Gonen and Lovell-Badge, 2019].

The TES Enhancer

We and other groups were interested in the gene expression regulation of Sox9 specifically in the testis. An initial study used a 120-kb bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) that was cloned upstream of an hsp68 minimal promoter and a LacZ reporter gene. Injection of this large fragment into zygotes of mice and screening of transgenic mice identified a 3.2-kb fragment which was termed TES (for testis-specific enhancer of Sox9), with a core element of 1.4 kb called TESCO (for TES core) that is located around 10 kb upstream of the Sox9 transcription start site [Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008]. TES-LacZ reporter mice exhibit expression that is reminiscent of testicular Sox9 expression starting from E11.5, specifically in Sertoli cells, and present throughout life, while being absent in the ovary. TES was shown to be bound in vivo by SOX9 itself, SRY, and SF1 [Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008]. Mutating the SRY/SOX9/SF1 binding sites within TESCO eliminated LacZ reporter expression [Sekido and Lovell-Badge, 2008]. These findings made TES a very promising candidate for a testis-specific enhancer of Sox9; however CRISPR deletion of TES or TESCO in mice resulted in 55 or 40% reduction in Sox9 mRNA levels compared to wild type, respectively, demonstrating that TES is definitely not the sole testis-specific enhancer of Sox9 [Gonen et al., 2017]. In support of this, and consistent with TES acting as a shadow enhancer, no TES mutations have yet been reported in DSD patients [Georg et al., 2010]. Interestingly, further reducing Sox9 mRNA levels by introducing a floxed Sox9 allele and a ß-actin Cre in a TES-deletion background resulted in ovotestis formation [Gonen et al., 2017]. A similar phenomenon was described in the Gli3 and Shox2 loci. It was shown that deletion of single enhancers resulted in no clear phenotype; however, upon reduction of the Gli3 or Shox2 baseline levels to 50% of normal, deletion of the same single enhancers led to reduction of the expression below the critical threshold and caused a limb phenotype [Osterwalder et al., 2018].

Interestingly, alterations of the 3D genome organisation were also shown to generate a similar phenotype. Paliou et al. [2019] deleted CTCF binding sites around the ZRS enhancer of the Shh gene and showed that this resulted in loss of the ZRS-Shh interaction, accompanied by 50% reduction in Shh expression, yet no significant phenotype was observed. When mice with these CTCF binding site deletions were bred on a hypomorphic ZRS allele, a major reduction in Shh expression was evident along with digit agenesis. These examples demonstrate that for some key developmental regulators, expression levels can directly determine developmental phenotypes, highlighting the need for their tight spatiotemporal transcriptional control.

Enhancer 13

In contrast to TES for which no mutations in DSD patients have yet been identified, deletions and duplications in 2 remote genomic regions, located more than 0.5 Mb upstream of the human SOX9, were reported in several 46,XY DSD and 46,XX DSD patients. Analysis of these DSD patients led to the identification of 2 minimal genomic regions termed XY SR and XX SR (or Rev Sex) [Kim et al., 2015].

XX SR (Rev Sex) is a 24-kb region located 559–583 kb upstream of SOX9 and found duplicated in several 46,XX DSD patients [Benko et al., 2011; Cox et al., 2011; Vetro et al., 2011; Xiao et al., 2013; Hyon et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015; Ohnesorg et al., 2017; Croft et al., 2018]. Croft et al. [2018] recently identified a human-specific, testis-specific enhancer within XX SR termed eSR-B.

XY SR is a 32.5-kb region located 607–639 kb upstream of SOX9, and it is deleted in several 46,XY DSD patients [Hyon et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2015].

To identify additional testis-specific enhancers of Sox9, we used DNaseI-Seq performed on sorted E13.5 and E15.5 Sertoli cells [Maatouk et al., 2017] as well as ATAC-Seq and H3K27Ac ChIP-Seq performed on sorted E13.5 Sertoli and granulosa cells [Gonen et al., 2018; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2019a]. Interrogating the 2-Mb gene desert in which Sox9 is located, we identified 33 putative enhancers, 16 of which were examined in vivo using transgenic reporter mice. Four of these enhancers displayed expression in the gonads with Enh13, Enh14, and Enh32 showing mostly testicular expression (in addition to TES), while Enh8 mostly drove ovarian expression [Gonen et al., 2018]. Out of these 4 novel enhancers, Enh13 stood out as it was a 557-bp enhancer located within the XY SR region previously identified in human DSD patients. Enh13 is highly conserved in mammals and exhibited a solid ATAC-Seq peak in Sertoli cells and to a lesser extent also in granulosa cells. Consistent with this finding, 5 independent stable transgenic lines all exhibited strong expression of LacZ in Sertoli cells while some also showed expression in granulosa cells. Remarkably, deletion of Enh13 alone resulted in XY male-to-female sex reversal on a C57BL/6J genetic background. Furthermore, this XY male-to-female sex reversal was also observed on a mixed C57BL/6J × CBA genetic background demonstrating the robustness of the phenotype [Gonen et al., 2018]. We showed that homozygous deletion of Enh13 leads to 80% reduction in Sox9 mRNA levels in XY gonads at E11.5 (compared to a ∼50% reduction upon TES deletion), a level comparable to XX gonads at this stage. Furthermore, SRY, and SOX9 itself, were shown to be bound to Enh13 in vivoby ChIP. Together, these findings suggest that Enh13 is the critical enhancer controlling the early expression of Sox9 in the gonads [Gonen et al., 2018].

Notably, fine-mapping of functional elements within the 32.5-kb XY SR identified a 783-bp element in mice, which when homozygously deleted causes XY male-to-female sex reversal [Ogawa et al., 2018]. Furthermore, eSR-A, a 1,514-bp enhancer located within the described XY SR was identified in humans, and deletion of which was shown to cause XY female development in human DSD patients [Croft et al., 2018]. Notably, Enh13 (557 bp) is fully embedded within this 783-bp element found in mice and within the 1,514-bp eSR-A enhancer identified in humans.

Interestingly, Croft et al. [2018] showed not only that deletion of eSR-A leads to XY male-to-female sex reversal in XY DSD patients but also that duplications within this region appear in XX DSD patients leading to XX female-to-male sex reversal. At first glance, this is surprising as we showed that Enh13 is bound by SRY, and XX individuals do not contain the SRY gene located on the Y chromosome. One possibility is that the low levels of SOX9 that are present in XX gonads at early gonadal stages [Morais da Silva et al., 1996; Zhao et al., 2018] can bind the duplicated copies of eSR-A/Enh13, leading to over-activation of SOX9 expression possibly through a positive feedback loop, thus tipping the balance towards male development. It will be interesting to examine this hypothesis in vivo in mice.

Other Gonadal Enhancers of Sox9

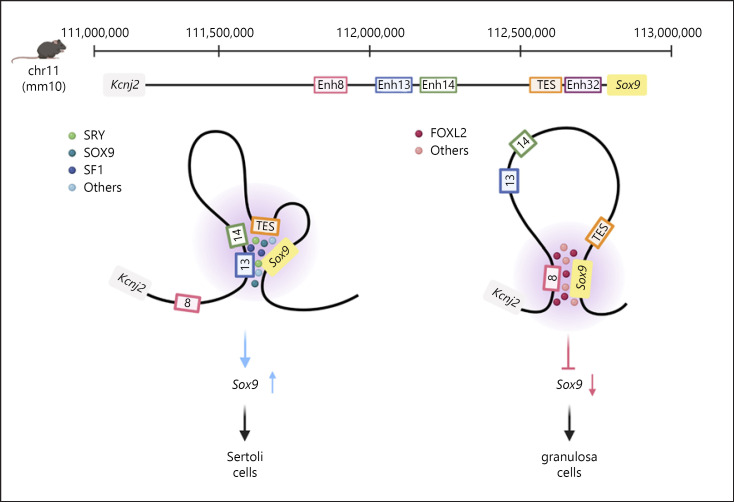

Despite the identification of Enh13 and TES as key Sox9 enhancers, the complex regulatory landscape that controls Sox9 expression in gonads is far from being completely understood. Several other putative enhancers in the Sox9 domain drive gonad-specific reporter gene expression [Gonen et al., 2018]. Deletion of 2 of these putative enhancers (Enh14) [Gonen et al., 2018] and (Enh32) [unpubl. data], has no effect on Sox9 mRNA levels at E13.5, indicating that these enhancers may either control Sox9 expression during a different developmental time window, and/or function redundantly to Enh13 and/or TES [Gonen et al., 2018]. It is possible that they act as shadow enhancers that confer transcriptional robustness under suboptimal conditions [Robson et al., 2019]. We speculate that the joint activity of Enh13, Enh14, Enh32, and TES initiates and maintains Sox9 expression in Sertoli cells by looping and interacting with the Sox9 promoter while being bound by some of the pro-male TFs (Fig. 3); this remains to be experimentally tested.

Fig. 3.

The regulatory landscape of the Sox9 gene. In the mouse, Sox9 is located on chromosome 11, with the Kcnj2 gene located 1.7 Mb upstream of Sox9. Five gonad-specific enhancers in the Sox9 locus were identified termed Enh8, Enh13, Enh14, TES, and Enh32. Enh13 was shown to have a critical role in the regulation of Sox9 at the sex determination stage. The other enhancers may function as shadow enhancers with redundant functions. We speculate that Enh13, Enh14, TES, and Enh32 are bound by SRY, SF1, SOX9, and maybe other pro-male TFs and are brought into proximity of the Sox9 promoter via DNA looping, leading to upregulation of Sox9 and hence Sertoli cell fate. In the female, we hypothesise that these enhancers do not interact with the Sox9 promoter; instead Enh8, bound by FOXL2 and other pro-female TFs, is in close proximity to the Sox9 promoter, which represses Sox9 expression and promotes granulosa cell fate acquisition.

Another putative enhancer, Enh8 (672 bp), located 838 kb upstream of Sox9, showed an unexpected pattern of expression. Transient and stable reporter mice carrying Enh8 showed a very strong reporter gene expression in the ovary with no expression in testis [Gonen et al., 2018]. Generation of additional lines showed that while ovarian expression persists, testicular expression can also be present [unpubl. data], consistent with the detection of accessible chromatin (by ATAC-Seq) and the enhancer mark H3K27ac (by ChIP-Seq) in both Sertoli and granulosa cells at Enh8 at E13.5 [Gonen et al., 2018]. It is surprising, however, to find a putative Sox9 gonadal enhancer that drives ovarian expression at E13.5, considering that Sox9 is normally not expressed at this stage in ovaries. Nonetheless, Sox9 is expressed at low levels in both sexes between E10.5–E11.5, after which it is repressed in granulosa cells and strongly activated in Sertoli cells [Kent et al., 1996; Morais da Silva et al., 1996; Zhao et al., 2018]. Furthermore, upon deletion of a single TF, Foxl2, adult granulosa cells transdifferentiate into Sertoli cells with SOX9 activation being one of the earliest markers for the transdifferentiation [Uhlenhaut et al., 2009]. This points towards a fast-acting mechanism that enables activation of Sox9 expression in females. Interestingly, several recent studies demonstrated FOXL2 binding to Enh8 in vivo and in vitro [Georges et al., 2014; Nicol et al., 2018; Rossitto et al., 2021]. One possibility is that Enh8 possesses an intrinsic ovary-specific enhancer activity that is repressed in its endogenous chromatin environment by mechanisms involving FOXL2 binding, thereby promoting ovary development. In this scenario, loss of FOXL2 binding would unmask the enhancer activity of Enh8, leading to Sox9 upregulation in granulosa cells. We hypothesise that Sertoli- and granulosa cell-specific 3D genome topologies, respectively, juxtapose the Sox9 promoter to regulatory elements with opposing activities, and/or facilitate enhancer contacts only in Sertoli cells (Fig. 3). Interestingly, a similar phenomenon was described for the Pitx1 locus and the Pen enhancer [Kragesteen et al., 2018]. Pen is active in both forelimb and hindlimb whereas Pitx1 is only expressed in the hindlimb. It was shown that in the hindlimb, Pen is in close proximity to the Pitx1 gene whereas in the forelimb it is folded away. The most likely explanation is that activation of Pitx1 by Pen is prevented in the forelimb by chromatin folding that prevents the enhancer from interacting with its target gene. Interestingly, this 3D genome folding is independent of CTCF and appears to be induced by binding of transcription factors and/or chromatin modifications [Kragesteen et al., 2018]. It will be fascinating to see whether a similar mechanism involving Enh8 operates at the Sox9 locus.

What Moles Can Teach Us about Sex Determination

A recent study highlights the power of evolutionary genetics in deciphering gonadal lineage specification [Real et al., 2020]. Male moles have a normal XY genotype, but mole XX females are “masculinized” with a so-called ovotestis instead of ovaries. These ovotestes are composed of a fully functional ovarian part and a testicular part that is devoid of fertile germ cells but contains androgen producing Leydig cells. This unique intersexuality causes an increased androgen synthesis in females leading to masculinized external genitalia and aggressive behaviour. Through phylogenomic analyses, the authors identified 2 genomic rearrangements in the mole genome that altered the regulatory landscape of key gonadal genes. The first affects the CYP17A1 gene and its regulatory sequences. CYP17A1 is involved in androgen production; therefore, the increased expression that is driven mainly by the duplication of its enhancers provides a plausible molecular mechanism for female mole masculinization [Real et al., 2020]. The second genomic rearrangement is a mole-specific inversion involving FGF9, a testis-determining gene. This inversion extends the FGF9 TAD beyond the boundaries found in other mammals, allowing FGF9 to interact with putative enhancers that may support its expression in mole gonads. These fascinating examples of regulatory innovation during evolution point to key roles for enhancers and 3D genome organisation in mole sexual development [Real et al., 2020]. It will be interesting to explore whether genomic rearrangements around key gonadal genes can affect sex determination in humans or may even affect gonadal function and fertility in adulthood.

Perspectives

Until recently, much of the focus to understand sex determination and DSD pathologies was directed at protein-coding genes and the roles they play in this complex developmental process.

Only in the last couple of years have we begun to explore how the non-coding genome contributes to sex determination in normal development and disease. Sex determination depends on the tightly balanced control over the levels of key developmental regulators. It therefore offers unique possibilities to dissect how the interplay between transcription factors, gene regulatory elements, and 3D genome organisation fine-tunes gene expression programmes to direct cell fate decisions and maintain cellular states. As advances in next-generation sequencing technologies fuel a current revolution in evolutionary genetics, propel whole genome sequencing into a routine tool for disease diagnostics, and enable genome-wide profiling of transcriptomes and epigenomes from small cell numbers down to single cells, it is highly likely that our knowledge in this area will grow rapidly in the near future. This will lead to a deeper understanding of the molecular tug of war that establishes and maintains gonadal cell fates and may also uncover fundamental regulatory principles that underpin developmental gene expression control more broadly.

Conflict of Interest Statement

S.S. is a co-founder of Enhanc3D Genomics Ltd.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Israeli Science Foundation Grant 710/20 to N.G. S.S. was supported by a UKRI MRC Rutherford Fund Fellowship (MR/T016787/1) and a Career Progression Fellowship from the Babraham Institute.

Author Contribution

N.G., S.S., and M.R. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Alexander JM, Guan J, Li B, Maliskova L, Song M, Shen Y, et al. Live-cell imaging reveals enhancer-dependent Sox2 transcription in the absence of enhancer proximity. Elife. 2019;8 doi: 10.7554/eLife.41769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson E, Devenney PS, Hill RE, Lettice LA. Mapping the Shh long-range regulatory domain. Development. 2014;141:3934–43. doi: 10.1242/dev.108480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrey G, Mundlos S. The three-dimensional genome: regulating gene expression during pluripotency and development. Development. 2017;144:3646–58. doi: 10.1242/dev.148304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baetens D, Mendonça BB, Verdin H, Cools M, De Baere E. Non-coding variation in disorders of sex development. Clin Genet. 2017;91:163–72. doi: 10.1111/cge.12911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerji J, Rusconi S, Schaffner W. Expression of a beta-globin gene is enhanced by remote SV40 DNA sequences. Cell. 1981;27:299–308. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrionuevo F, Bagheri-Fam S, Klattig J, Kist R, Taketo MM, Englert C, et al. Homozygous inactivation of Sox9 causes complete XY sex reversal in mice. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:195–201. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bashamboo A, Eozenou C, Rojo S, McElreavey K. Anomalies in human sex determination provide unique insights into the complex genetic interactions of early gonad development. Clin Genet. 2017;91:143–56. doi: 10.1111/cge.12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baxter RM, Arboleda VA, Lee H, Barseghyan H, Adam MP, Fechner PY, et al. Exome sequencing for the diagnosis of 46,XY disorders of sex development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:E333–44. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beagan JA, Phillips-Cremins JE. On the existence and functionality of topologically associating domains. Nat Genet. 2020;52:8–16. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0561-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belton JM, McCord RP, Gibcus JH, Naumova N, Zhan Y, Dekker J, et al. Hi-C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods. 2012;58:268–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benabdallah NS, Williamson I, Illingworth RS, Kane L, Boyle S, Sengupta D, et al. Decreased enhancer-promoter proximity accompanying enhancer activation. Mol Cell. 2019;76:473–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benko S, Gordon CT, Mallet D, Sreenivasan R, Thauvin-Robinet C, Brendehaug A, et al. Disruption of a long distance regulatory region upstream of SOX9 in isolated disorders of sex development. J Med Genet. 2011;48:825–30. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatti GK, Khullar N, Sidhu IS, Navik US, Reddy AP, Reddy PH, et al. Emerging role of non-coding RNA in health and disease. Metab Brain Dis. 2021;36:1119–34. doi: 10.1007/s11011-021-00739-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birk OS, Casiano DE, Wassif CA, Cogliati T, Zhao L, Zhao Y, et al. The LIM homeobox gene Lhx9 is essential for mouse gonad formation. Nature. 2000;403:909–13. doi: 10.1038/35002622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulanger L, Pannetier M, Gall L, Allais-Bonnet A, Elzaiat M, Le Bourhis D, et al. FOXL2 is a female sex-determining gene in the goat. Curr Biol. 2014;24:404–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle AP, Davis S, Shulha HP, Meltzer P, Margulies EH, Weng Z, et al. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell. 2008;132:311–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1213–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calderon L, Weiss FD, Beagan JA, Oliveira MS, Wang Y-F, Carroll T, et al. Activity-induced gene expression and long-range enhancer-promoter contacts in cohesin-deficient neurons. bioRxiv. 2021 2021.2002.2024.432639. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capel B. Vertebrate sex determination: evolutionary plasticity of a fundamental switch. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18:675–89. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaboissier MC, Kobayashi A, Vidal VI, Lützkendorf S, van de Kant HJ, Wegner M, et al. Functional analysis of Sox8 and Sox9 during sex determination in the mouse. Development. 2004;131:1891–901. doi: 10.1242/dev.01087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chassot AA, Ranc F, Gregoire EP, Roepers-Gajadien HL, Taketo MM, Camerino G, et al. Activation of beta-catenin signaling by Rspo1 controls differentiation of the mammalian ovary. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1264–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi J, Lysakovskaia K, Stik G, Demel C, Soding J, Tian TV, et al. Evidence for additive and synergistic action of mammalian enhancers during cell fate determination. Elife. 2021;10:e65381. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox JJ, Willatt L, Homfray T, Woods CG. A SOX9 duplication and familial 46,XX developmental testicular disorder. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:91–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1010311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cremer T, Cremer M. Chromosome territories. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003889. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croft B, Ohnesorg T, Hewitt J, Bowles J, Quinn A, Tan J, et al. Human sex reversal is caused by duplication or deletion of core enhancers upstream of SOX9. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07784-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuartero S, Weiss FD, Dharmalingam G, Guo Y, Ing-Simmons E, Masella S, et al. Control of inducible gene expression links cohesin to hematopoietic progenitor self-renewal and differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:932–41. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0184-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson IF, Bauer B, Goetz D, Tang W, Wutz G, Peters JM. DNA loop extrusion by human cohesin. Science. 2019;366:1338–45. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz3418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davidson IF, Goetz D, Zaczek MP, Molodtsov MI, Huis In 't Veld PJ, Weissmann F, et al. Rapid movement and transcriptional re-localization of human cohesin on DNA. EMBO J. 2016;35:2671–85. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davidson IF, Peters JM. Genome folding through loop extrusion by SMC complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:445–64. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Laat W, Duboule D. Topology of mammalian developmental enhancers and their regulatory landscapes. Nature. 2013;502:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Despang A, Schöpflin R, Franke M, Ali S, Jerković I, Paliou C, et al. Functional dissection of the Sox9-Kcnj2 locus identifies nonessential and instructive roles of TAD architecture. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1263–71. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0466-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickel DE, Ypsilanti AR, Pla R, Zhu Y, Barozzi I, Mannion BJ, et al. Ultraconserved enhancers are required for normal development. Cell. 2018;172:491–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dixon JR, Jung I, Selvaraj S, Shen Y, Antosiewicz-Bourget JE, Lee AY, et al. Chromatin architecture reorganization during stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2015;518:331–6. doi: 10.1038/nature14222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–80. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doni Jayavelu N, Jajodia A, Mishra A, Hawkins RD. Candidate silencer elements for the human and mouse genomes. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1061. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14853-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dostie J, Richmond TA, Arnaout RA, Selzer RR, Lee WL, Honan TA, et al. Chromosome Conformation Capture Carbon Copy (5C): a massively parallel solution for mapping interactions between genomic elements. Genome Res. 2006;16:1299–309. doi: 10.1101/gr.5571506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eggers S, Sadedin S, van den Bergen JA, Robevska G, Ohnesorg T, Hewitt J, et al. Disorders of sex development: insights from targeted gene sequencing of a large international patient cohort. Genome Biol. 2016;17:243. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1105-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foster JW, Dominguez-Steglich MA, Guioli S, Kwok C, Weller PA, Stevanović M, et al. Campomelic dysplasia and autosomal sex reversal caused by mutations in an SRY-related gene. Nature. 1994;372:525–30. doi: 10.1038/372525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franke M, Ibrahim DM, Andrey G, Schwarzer W, Heinrich V, Schöpflin R, et al. Formation of new chromatin domains determines pathogenicity of genomic duplications. Nature. 2016;538:265–9. doi: 10.1038/nature19800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fudenberg G, Abdennur N, Imakaev M, Goloborodko A, Mirny LA. Emerging evidence of chromosome folding by loop extrusion. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2017;82:45–55. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2017.82.034710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fudenberg G, Imakaev M, Lu C, Goloborodko A, Abdennur N, Mirny LA. Formation of chromosomal domains by loop extrusion. Cell Rep. 2016;15:2038–49. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galupa R, Nora EP, Worsley-Hunt R, Picard C, Gard C, van Bemmel JG, et al. A conserved noncoding locus regulates random monoallelic Xist expression across a topological boundary. Mol Cell. 2020;77:352–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Moreno SA, Futtner CR, Salamone IM, Gonen N, Lovell-Badge R, Maatouk DM. Gonadal supporting cells acquire sex-specific chromatin landscapes during mammalian sex determination. Dev Biol. 2019a;446:168–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcia-Moreno SA, Lin YT, Futtner CR, Salamone IM, Capel B, Maatouk DM. CBX2 is required to stabilize the testis pathway by repressing Wnt signaling. PLoS Genet. 2019b;15:e1007895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Georg I, Bagheri-Fam S, Knower KC, Wieacker P, Scherer G, Harley VR. Mutations of the SRY-responsive enhancer of SOX9 are uncommon in XY gonadal dysgenesis. Sex Dev. 2010;4:321–5. doi: 10.1159/000320142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Georges A, L'Hôte D, Todeschini AL, Auguste A, Legois B, Zider A, et al. The transcription factor FOXL2 mobilizes estrogen signaling to maintain the identity of ovarian granulosa cells. Elife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.04207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gisselbrecht SS, Palagi A, Kurland JV, Rogers JM, Ozadam H, Zhan Y, et al. Transcriptional silencers in Drosophila serve a dual role as transcriptional enhancers in alternate cellular contexts. Mol Cell. 2020;77:324–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonen N, Lovell-Badge R. The regulation of Sox9 expression in the gonad. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2019;134:223–52. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonen N, Quinn A, O'Neill HC, Koopman P, Lovell-Badge R. Correction: Normal levels of Sox9 expression in the developing mouse testis depend on the TES/TESCO enhancer, but this does not act alone. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonen N, Futtner CR, Wood S, Garcia-Moreno SA, Salamone IM, Samson SC, et al. Sex reversal following deletion of a single distal enhancer of Sox9. Science. 2018;360:1469–73. doi: 10.1126/science.aas9408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gubbay J, Collignon J, Koopman P, Capel B, Economou A, Münsterberg A, et al. A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature. 1990;346:245–50. doi: 10.1038/346245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haarhuis JHI, van der Weide RH, Blomen VA, Yáñez-Cuna JO, Amendola M, van Ruiten MS, et al. The cohesin release factor WAPL restricts chromatin loop extension. Cell. 2017;169:693–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hacker A, Capel B, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Expression of Sry, the mouse sex determining gene. Development. 1995;121:1603–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hansen AS, Pustova I, Cattoglio C, Tjian R, Darzacq X. CTCF and cohesin regulate chromatin loop stability with distinct dynamics. Elife. 2017;6:e25776. doi: 10.7554/eLife.25776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD, Kheradpour P, Stark A, Harp LF, et al. Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature. 2009;459:108–12. doi: 10.1038/nature07829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsieh TH, Weiner A, Lajoie B, Dekker J, Friedman N, Rando OJ. Mapping nucleosome resolution chromosome folding in yeast by micro-C. Cell. 2015;162:108–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu YC, Okumura LM, Page DC. Gata4 is required for formation of the genital ridge in mice. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang D, Petrykowska HM, Miller BF, Elnitski L, Ovcharenko I. Identification of human silencers by correlating cross-tissue epigenetic profiles and gene expression. Genome Res. 2019;29:657–67. doi: 10.1101/gr.247007.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hughes IA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, Lee PA. Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society/European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology Consensus G: Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. J Pediatr Urol. 2006;2:148–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hughes JR, Roberts N, McGowan S, Hay D, Giannoulatou E, Lynch M, et al. Analysis of hundreds of cis-regulatory landscapes at high resolution in a single, high-throughput experiment. Nat Genet. 2014;46:205–12. doi: 10.1038/ng.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hyon C, Chantot-Bastaraud S, Harbuz R, Bhouri R, Perrot N, Peycelon M, et al. Refining the regulatory region upstream of SOX9 associated with 46,XX testicular disorders of sex development (DSD) Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A:1851–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibrahim DM, Mundlos S. Three-dimensional chromatin in disease: What holds us together and what drives us apart. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2020;64:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2020.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Javierre BM, Burren OS, Wilder SP, Kreuzhuber R, Hill SM, Sewitz S, et al. Lineage-specific genome architecture links enhancers and non-coding disease variants to target gene promoters. Cell. 2016;167:1369–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jo A, Denduluri S, Zhang B, Wang Z, Yin L, Yan Z, et al. The versatile functions of Sox9 in development, stem cells, and human diseases. Genes Dis. 2014;1:149–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karl J, Capel B. Sertoli cells of the mouse testis originate from the coelomic epithelium. Dev Biol. 1998;203:323–33. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Katoh-Fukui Y, Tsuchiya R, Shiroishi T, Nakahara Y, Hashimoto N, Noguchi K, et al. Male-to-female sex reversal in M33 mutant mice. Nature. 1998;393:688–92. doi: 10.1038/31482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kent J, Wheatley SC, Andrews JE, Sinclair AH, Koopman P. A male-specific role for SOX9 in vertebrate sex determination. Development. 1996;122:2813–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim GJ, Sock E, Buchberger A, Just W, Denzer F, Hoepffner W, et al. Copy number variation of two separate regulatory regions upstream of SOX9 causes isolated 46,XY or 46,XX disorder of sex development. J Med Genet. 2015;52:240–7. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim Y, Bingham N, Sekido R, Parker KL, Lovell-Badge R, Capel B. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 regulates proliferation and Sertoli differentiation during male sex determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16558–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702581104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim Y, Kobayashi A, Sekido R, DiNapoli L, Brennan J, Chaboissier MC, et al. Fgf9 and Wnt4 act as antagonistic signals to regulate mammalian sex determination. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klein DC, Hainer SJ. Genomic methods in profiling DNA accessibility and factor localization. Chromosome Res. 2020;28:69–85. doi: 10.1007/s10577-019-09619-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Koopman P, Gubbay J, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature. 1991;351:117–21. doi: 10.1038/351117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kragesteen BK, Spielmann M, Paliou C, Heinrich V, Schöpflin R, Esposito A, et al. Dynamic 3D chromatin architecture contributes to enhancer specificity and limb morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1463–73. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0221-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kreidberg JA, Sariola H, Loring JM, Maeda M, Pelletier J, Housman D, et al. WT-1 is required for early kidney development. Cell. 1993;74:679–91. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90515-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kusaka M, Katoh-Fukui Y, Ogawa H, Miyabayashi K, Baba T, Shima Y, et al. Abnormal epithelial cell polarity and ectopic epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression induced in Emx2 KO embryonic gonads. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5893–904. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kvon EZ, Waymack R, Gad M, Wunderlich Z. Enhancer redundancy in development and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2021;22((5)):324–36. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00311-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kvon EZ, Zhu Y, Kelman G, Novak CS, Plajzer-Frick I, Kato M, et al. Comprehensive in vivo interrogation reveals phenotypic impact of human enhancer variants. Cell. 2020;180:1262–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]