Abstract

Vaginal trichomonosis is a highly prevalent infection which has been associated with human immunodeficiency virus acquisition and preterm birth. Culture is the current “gold standard” for diagnosis. As urine-based testing using DNA amplification techniques becomes more widely used for other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, a similar technique for trichomonosis would be highly desirable. Women attending an STD clinic for a new complaint were screened for Trichomonas vaginalis by wet-preparation (wet-prep) microscopy and culture and for the presence of T. vaginalis DNA by specific PCR of vaginal and urine specimens. The presence of trichomonosis was defined as the detection of T. vaginalis by direct microscopy and/or culture from either vaginal samples or urine. The overall prevalence of trichomonosis in the population was 28% (53 of 190). The sensitivity and specificity of PCR using vaginal samples were 89 and 97%, respectively. Seventy-four percent (38 of 51) of women who had a vaginal wet prep or vaginal culture positive for trichomonads had microscopic and/or culture evidence of the organisms in the urine. Two women were positive for trichomonads by wet prep or culture only in the urine. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR using urine specimens were 64 and 100%, respectively. These results indicate that the exclusive use of urine-based detection of T. vaginalis is not appropriate in women. PCR-based detection of T. vaginalis using vaginal specimens may provide an alternative to culture.

Although bacterial sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia are declining in the United States, the rate of infections caused by Trichomonas vaginalis remains constant. Vaginal trichomonosis has been linked to preterm birth and acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus (5, 20); however, increased screening efforts have not materialized. Despite its limited sensitivity (19), direct microscopic examination of the vaginal fluid remains the most widely utilized diagnostic test for this infection. Culture of the organism using vaginal specimens is the current “gold standard” (4); however, PCR techniques are currently being designed. As urine-based testing using DNA amplification techniques becomes more widely used for gonorrhea and chlamydia (22), a similar technique for trichomonosis would be highly desirable. In order to evaluate the possible use of urine for the diagnosis of trichomonosis in women, we tested urine and vaginal fluids for the presence of T. vaginalis using direct microscopy, culture, and PCR and compared the relative sensitivities of these methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Women attending the Jefferson County Department of Health sexually transmitted disease clinic for either screening or a new complaint were eligible for entry into the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Jefferson County Department of Health. During the routine pelvic examination, additional swab specimens were collected from the vaginal vault. One of these was used to inoculate culture medium for T. vaginalis at the bedside (In Pouch TV; BioMed Diagnostics Inc., San Jose, Calif.) (4). The second swab was placed into a cryogenic airtight vial for PCR studies. Vaginal fluid wet preparations (wet preps) were examined by light microscopy at ×400 by the examining clinician as part of the routine examination of the patient. Vaginal symptoms including discharge, pruritus, and odor were recorded. The patient was also asked to provide 20 to 40 ml of urine which was pelleted in its entirety at 1,000 × g for 5 min, decanted, and resuspended in 250 μl of sterile water. This initial centrifugation was performed at a low speed to help maintain the viability of the trichomonads for culture. Resuspension of the pellet in water rather than saline was performed because of a possible lethal effect of saline previously reported (16). Fifty microliters of the suspension was placed into a culture pouch, an additional aliquot was examined microscopically for motile trichomonads, and the remainder was transported to the laboratory for PCR testing. Culture pouches were incubated at 37°C and examined daily for up to 5 days for the presence of motile trichomonads.

PCR for T. vaginalis.

Specimens for PCR were processed for freezing within 2 to 4 h. Vaginal swabs were vigorously agitated in 1 ml of sterile water and then centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of sterile distilled water and then frozen at −20°C. The urine pellet received from the clinical site was resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and repelleted at 2,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was rinsed with 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and then frozen at −20°C. DNA was extracted as previously described with some modification (31). Briefly, thawed samples were resuspended in 600 μl of lysis buffer (1 M Tris, 0.5 M EDTA, 10% glucose, and 2 mg of lysozyme per ml), heated at 80°C for 5 min, and then cooled to room temperature. The samples were RNase treated (Promega, Madison, Wis.) (3 μl; 0.5 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Proteins were precipitated with 0.2 N NaOH–1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–5 M CH3COOK (pH 4.8) for 5 min on ice and then centrifuged for 3 min at 2,000 × g. DNA was precipitated with 600 μl of isopropanol and then centrifuged for 3 min at 2,000 × g, and then the DNA pellet was washed with 600 μl of 70% ethanol and centrifuged for 3 min at 2,000 × g. The DNA pellet was dried, resuspended in 50 to 100 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)–1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and heated at 65°C for 1 h. The presence of DNA was confirmed in each sample by electrophoresis prior to PCR amplification. T. vaginalis-specific primers TV3 (5′ ATTGTCGAACATTGGTCTTACCCTC 3′) and TV7 (5′ TCTGTGCCGTCTTCAAGTATGC 3′) (15) were used for PCR amplification. The PCR mixture consisted of 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 4 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (2.5 mM each), 0.5 μl of each primer pair (10 pmol/μl), 0.5 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) (5 U/μl), 10 μl of sample (5 to 10 ng/μl), and 29.5 μl of distilled water. Positive and negative controls were included in all PCR runs. The positive control consisted of DNA isolated from a clinical isolate of T. vaginalis grown in batch culture in vitro. Negative controls included DNA from a clinical isolate of Lactobacillus spp., PCR mix with primers but no DNA, and human genomic DNA. PCR amplification consisted of 30 cycles of 1 min at 90°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 2 min at 72°C. After amplification, there was an additional extension step at 72°C for 7 min, and then the samples were cooled to 4°C. Five microliters of amplified product was electrophoresed on a 2% agarose–0.5-μg/ml ethidium bromide gel, viewed on a UV light box, and photographed. Samples containing a 300-bp fragment were considered positive for T. vaginalis. The specificity of the PCR was confirmed by sequence analysis of the 300-bp PCR product from random samples as previously described (34).

Inhibition assays were performed on discrepant samples. The reaction mix used was as previously described with the exception that DNA from a clinical isolate of T. vaginalis (8 ng of DNA in a 50-μl volume) was added with 10 μl of sample.

Serial dilutions were made of a live culture of a clinical isolate of Trichomonas and tested to detect the lower limit of sensitivity for the PCR assay. Dilutions were made in deionized water, and then DNA was extracted and processed as described above.

Statistical methods.

Statistical comparisons were made using the EpiInfo software program, version 6 (A. Dean, J. Dean, and D. Columbeer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.). Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated to evaluate statistically significant differences between collection methods (6). Trichomonosis was defined as the detection of motile trichomonads by either direct microscopy or culture in either vaginal or urine specimens. This was the comparator for all other methods.

RESULTS

Samples were obtained from 190 women. The overall prevalence of trichomonosis was 28% (53 of 190). The sensitivities and specificities of direct microscopy, culture, and PCR of both urine and vaginal swab samples compared to the previously defined gold standard are shown in Table 1. The most sensitive method for the detection of T. vaginalis was culture of the vaginal fluid, with a sensitivity of 94.3%. Direct microscopy of either urine or vaginal fluid was the least sensitive, at only 58.5%.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of diagnostic tests for T. vaginalis in femalesa

| Diagnostic method | No. true positive | No. false positive | No. false negative | No. true negative | Sensitivity

|

Specificity

|

Predictive value (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | Positive | Negative | |||||

| Vaginal swab culture | 50 | 0 | 3 | 137 | 94.3 | 83.4–98.5 | 100 | 96.6–100 | 100 | 97.9 |

| Vaginal PCR | 47 | 4 | 6 | 133 | 88.7 | 76.3–95.3 | 97.1 | 92.2–99.1 | 92.2 | 95.7 |

| Vaginal wet prep | 31 | 0 | 22 | 137 | 58.5 | 44.2–71.6 | 100 | 96.6–100 | 100 | 86.2 |

| Urine culture | 32 | 0 | 21 | 137 | 60.4 | 46.0–73.2 | 100 | 96.6–100 | 100 | 86.7 |

| Urine PCR | 34 | 0 | 19 | 137 | 64.2 | 49.7–76.5 | 100 | 96.6–100 | 100 | 87.8 |

| Urine wet prep | 31 | 0 | 22 | 137 | 58.5 | 44.2–71.6 | 100 | 96.6–100 | 100 | 86.2 |

n = 190. The gold standard is trichomonads visualized from any wet prep or culture (n = 53). CI, confidence interval.

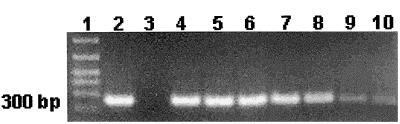

PCR-based detection of T. vaginalis from vaginal swabs was equivalent to culture with a sensitivity and specificity of 88.7 and 97.1%, respectively. Four vaginal swab samples were positive by PCR but negative by wet prep and culture. DNA sequence analysis of the PCR products from all four women was performed. A BLAST search of the National Institutes of Health GenBank confirmed that the 300-bp PCR product corresponded with T. vaginalis DNA. Sufficient DNA was available for only one of these four specimens to be tested with alternative T. vaginalis-specific PCR primers (TVA5 and -6) (27), and this was also positive for T. vaginalis DNA. The lower limit of T. vaginalis detection by the PCR assay was found to be one organism (Fig. 1). Motile trichomonads were detected in the urine by direct microscopy or culture from 74.5% (38 of 51) of women with vaginal trichomonosis detected by similar means. Two women were positive for trichomonads in the urine but not in vaginal specimens. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR for urine specimens were 64.2 and 100%, respectively, compared to the previously defined gold standard (Table 1). The sensitivity of PCR for urine specimens from only those women with motile trichomonads detected in the urine by wet mount or culture was still only 68.4% (26 of 38).

FIG. 1.

Serial dilution testing of T. vaginalis PCR with TVK3-TVK7 primer set. Lane 1, DNA marker; lane 2, T. vaginalis isolate; lane 3, Lactobacillus isolate; lane 4, stock sample, 1.2 × 105 parasites; lane 5, 1.2 × 104 dilution; lane 6, 1.2 × 103 dilution; lane 7, 120 parasites; lane 8, 12 parasites; lane 9, 6 parasites; lane 10, 1 parasite.

Inhibition assays were performed for 32 urine samples from women with either a culture or a vaginal PCR sample positive for T. vaginalis. Inhibitors for PCR were present in 3 of 32 (9%) samples. PCR inhibitor was eliminated in these three specimens by use of a threefold increase of Taq, confirming that these samples were false negatives.

Seventy-five percent (40 of 53) of women with trichomonads complained of vaginal symptoms such as discharge, odor, and itching. Among women with trichomonads, the presence of symptoms was not associated with a positive vaginal fluid wet prep for T. vaginalis (24 of 40, 62.5%, versus 6 of 13, 46.2%; P = 0.47). Review of the medical records for the four women who had positive PCRs but negative culture and wet preps was unrevealing.

DISCUSSION

Infection with T. vaginalis remains highly prevalent worldwide despite the availability of an inexpensive, single-dose, curative antibiotic regimen (10). To date, little emphasis has been placed on the importance of decreasing rates of this infection even though it has been associated with human immunodeficiency virus acquisition and increased risk of preterm birth (5, 20). One strategy for increasing diagnosis and treatment of trichomonosis is the use of a screening test with increased sensitivity compared to the traditional wet prep of vaginal fluid. Culture methods are currently the gold standard and should be considered for widespread clinical use (2, 4). PCR techniques have proven superior to culture for other infections such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, and moreover urine has been found to be a suitable testing substrate for these techniques in men and women (7, 32). A similar approach would further facilitate screening for trichomonads. Although urine specimens are suitable for the culture of T. vaginalis in males (18), there are limited published data on rates of urethral colonization in women. In one study of the incidence of urinary tract trichomoniasis, 18 of 25 (72%) women with vaginal trichomonosis had a positive urine culture for T. vaginalis obtained from a catheterized specimen (J. Finley, P. Breeden, W. Lushbaugh, and J. Cleary, Abstr. Int. Congr. Sex. Transm. Dis., abstr. 679, p. 175, 1997). Another reference states that urethral colonization occurs in up to 90% of women, but data are not presented (17). Among adolescent women, the sensitivity of detection of trichomonads by direct microscopy of centrifuged urine specimens was 64%, and use of this technique improved the level of detection achieved by using direct microscopic examination of vaginal fluid alone by 12% (3). Our data are comparable to those of the first study in that the percentage of women with trichomonosis who had evidence of motile trichomonads in the urine was approximately 75%. This rate of urethral colonization and/or infection with T. vaginalis is comparable to that previously reported for gonorrhea and chlamydia (23, 32). For gonorrhea, detection of urethral colonization in women by culture was not found to be necessary for detection of gonorrhea by PCR of the urine, suggesting either that culture techniques are insensitive for detecting urethral colonization in females or that urine is contaminated by organisms from the vaginal secretions (32). Since our study used voided urine, we might have anticipated greater isolation rates and better detection by PCR if the latter were true. The former hypothesis also seems unlikely considering the ease with which the organism is grown in culture compared to those causing gonorrhea and chlamydia. It is possible, therefore, that urethral colonization rates in women may be only 70 to 75%, as suggested by the available data. If this is true, urine may not be a suitable testing substrate for this organism even with the use of PCR. Additionally, 9% of urine specimens in our study showed evidence of PCR inhibitors, a factor which must be considered (25). However, PCR inhibitor was eliminated by use of a threefold increase in Taq. van der Schee et al. also compared PCR results from urine specimens to vaginal cultures and wet prep and found that the sensitivity of PCR for urine specimens was 100% (33). However, this comparison was based on only six patients with wet-mount- or culture-proven trichomoniasis.

Several groups of investigators have reported their findings on the development of a PCR technique for trichomonads. In 1992, Riley et al. published a report of primers (TVA5 and TVA6) for the detection of T. vaginalis (27). Subsequently, many additional primer sets have been described. The sensitivity and specificity of these primers in clinical studies using vaginal swab specimens have varied, with sensitivities of 85 to 100% being reported (Table 2). The sensitivity and specificity of our PCR method using vaginal swab specimens were comparable to those of other published studies. Unlike PCR for infections such as gonorrhea and chlamydia, which appears to have greater sensitivity than culture methods (7, 32), PCR for trichomonads does not appear to offer a diagnostic advantage. This may be due to the fact that T. vaginalis is much less fastidious for culture than is Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis. Successful culture of T. vaginalis requires only the multiplication of a single organism, the same as that needed for PCR. PCR of vaginal swabs may be advantageous in settings where incubation of cultures is not possible and shipping of specimens to a reference laboratory is required. Self-obtained vaginal swab specimens, which have been shown to be appropriate specimens for PCR testing of gonorrhea and chlamydia (11, 12) as well as for culture of T. vaginalis (29), may also be useful for the PCR technique. In addition, PCR may be superior to culture for the diagnosis of T. vaginalis in males. Although Hobbs et al. in their study of T. vaginalis in males found the sensitivity of PCR using urethral swabs to be only 82%, the authors suggest that technical factors may have played a role (9). There are no published studies on the use of PCR for detection of trichomonads in male urine specimens. Of note also are the many different primers which have been used for the detection of T. vaginalis by PCR (Table 2). Direct comparisons of these primers, and perhaps the development of new primers, could prove useful with regards to refining the technique and improving sensitivity.

TABLE 2.

Summary of PCR primers for T. vaginalis and results of clinical trials using PCR in females

| Authors (year) | Reference no. | Principal primers | Type of specimen | Sensitivity/specificity of PCR (%)a | Commentsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riley et al. (1992) | 27 | TR 7 and 8, TV A5 and 6, TR 5 and 6, FE 1 and 2 | Laboratory isolates | NA | |

| Pâces et al. (1992) | 24 | TV-E650-1c | Laboratory isolates | NA | |

| Kengne et al. (1994) | 15 | TVK 3, 4 and 7 | Laboratory isolates | NA | |

| Katiyar and Edlind (1994) | 14 | BTUB 9 and 2 (beta-tubulin genes) | Laboratory isolates | NA | |

| Alderete et al. (1995) | 1 | AP651 and -2c | Laboratory isolates | NA | |

| Jeremias et al. (1994) | 13 | TVA5 and -6 | Vaginal swab | 100/97.8 | Prevalence, 11.5% (6 of 52); symptomatic |

| Heine et al. (1997) | 8 | TVA5 and -6 | Vaginal swab | 91.8/95.2 | Prevalence, 14.6% (44 of 300); symptomatic and symptomatic |

| Shaio et al. (1997) | 30 | TV-E650-1 | Vaginal swab | 100/100 | Prevalence, 8.9% (40 of 451); symptomatic and symptomatic |

| Madico et al. (1998) | 21 | BTUB 9 and 2 | Vaginal swab | 96/98 | Prevalence, 6.6% (23 of 350) |

| Paterson et al. (1998) | 26 | TVA5 and -6 | Tampon specimen | 92.7/92.1 | Prevalence, 8.6% (51 of 590); delayed (up to 5 days) inoculation of culture medium may have affected results |

| van der Schee et al. (1999) | 33 | TVK3 and -7 | Vaginal swab | 95.8/98.1 | Prevalence, 5.7% (48 of 846) |

| Urine | 100/97.4 | Prevalence, 3.0% (6 of 202) | |||

| Ryu et al. (1999) | 28 | TV-E650-1 | Vaginal swab | 100/96.8 | Prevalence, 2.4% (10 of 426); symptomatic and asymptomatic |

Positive culture and/or wet prep was used as the gold standard. NA, not available.

Prevalence is based on wet prep and culture.

Original cloning sequence.

Evaluation of the four false-positive specimens in our study suggested that these may represent true infection. All specimens were processed in a biological hood which would greatly limit the possibility of contamination. All PCR products were consistent with T. vaginalis sequences. Although only one specimen had sufficient quantity available to test with additional primers, the result was positive. However, even if these are regarded as true-positive results, the sensitivity of PCR did not exceed that of culture.

In summary, T. vaginalis was detected in the urine of 75% of women with trichomoniasis using standard methods. PCR of urine for T. vaginalis had a sensitivity less than that of microscopy and culture. PCR for T. vaginalis using vaginal swab specimens was equivalent to culture. PCR of vaginal swab specimens may be considered in settings where incubation of cultures is not feasible or in settings where self-collection techniques are utilized. Important areas for future investigations include further studies of rates of urethral colonization with T. vaginalis in females, enhancement of the sensitivity of PCR assays including comparison and refinement of T. vaginalis-specific primers, and suitability of PCR for detection of trichomonads in male urine specimens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH Sexually Transmitted Disease Cooperative Research Centers grant AI 38514 and NIH Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinical Trials Unit (NO AI75329).

BioMed Diagnostics, Inc., supplied the culture media for T. vaginalis. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Bari Cotton, Jill Bailey Griffin, and Moira Venglarik with patient enrollment and acknowledge Frank Barrientes and Amanda Beverly for laboratory assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderete J F, O'Brien J L, Arrayo R, et al. Cloning and molecular characterization involved in Trichomonas vaginalis cytoadherence. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beverly A L, Venglarik M, Cotton B, Schwebke J R. Viability of Trichomonas vaginalis in transport medium. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3749–3750. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3749-3750.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake D, Duggan A, Jaffe A. Use of spun urine to enhance detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in adolescent women. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1222–1226. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.12.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borchardt K, Smith R. An evaluation of an InPouch TV culture method for diagnosing Trichomonas vaginalis infection. Genitourin Med. 1991;67:149–152. doi: 10.1136/sti.67.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cotch M F, Pastorek J G, Nugent R P, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:361–362. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleiss J. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaydos C A, Howell M R, Quinn T C, Gaydos J C, McKee K T J. Use of ligase chain reaction with urine versus cervical culture for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in an asymptomatic military population of pregnant and nonpregnant females attending Papanicolaou smear clinics. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1300–1304. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1300-1304.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heine R P, Wiensfeld H C, Sweet R L, Witkin S S. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of distal vaginal specimens: a less invasive strategy for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:985–987. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobbs M, Kazembe P, Reed A, Miller W, Nkata E, Zimba D, Daly C, Chakraborty H, Cohen M, Hoffman I. Trichomonas vaginalis as a cause of urethritis in Malawian men. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:381–387. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199908000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hook E W., III Trichomonas vaginalis—no longer a minor STD. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:388–389. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199908000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hook E W, III, Ching S F, Stephens J, Hardy K F, Smith K R, Lee H H. Diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in women by using the ligase chain reaction on patient-obtained vaginal swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2129–2132. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2129-2132.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hook E W, III, Smith K, Mullen C, Stephens J, Rinehardt L, Pate M S, Lee H H. Diagnosis of genitourinary Chlamydia trachomatis infections by using the ligase chain reaction on patient-obtained vaginal swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2133–2135. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.8.2133-2135.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeremias J, Draper D, Ziegert M, et al. Detection of Trichomonas vaginalis using the polymerase chain reaction in pregnant and non-pregnant women. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1994;2:16–19. doi: 10.1155/S1064744994000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katiyar S K, Edlind T D. B-tubulin genes of Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;64:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kengne P, Veas F, Vidal N, Rey J L, Cuny G. Trichomonas vaginalis: repeated DNA target reaction diagnosis. Cell Mol Biol. 1994;40:819–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostara I, Carageorgiou H, Varonos D, Tzannetis S. Growth and survival of Trichomonas vaginalis. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:555–560. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-6-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger J, Alderete J. Trichomonas vaginalis and trichomoniasis. In: Holmes K, Sparling F, Lemon S, et al., editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1999. pp. 587–604. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger J, Verdon M, Siegel N, Holmes K. Natural history of urogenital trichomoniasis in men. J Urol. 1993;149:1455–1458. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger J N, Tam M R, Stevens C E, et al. Diagnosis of trichomoniasis. JAMA. 1988;259:1223–1227. doi: 10.1001/jama.259.8.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laga M, Manoka A, Kivuvu M, et al. Non-ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV-1 transmission in women: results from a cohort study. AIDS. 1993;7:95–102. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199301000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madico G, Quinn T C, Rompalo A, McKee K T, Jr, Gaydas C A. Diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection by PCR using vaginal swab samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3205–3210. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3205-3210.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh M K, Smith K R, O'Cain M, Kilmer D, Johnson J, Hook E W., III Urine-based screening of adolescents in detention to guide treatment for gonococcal and chlamydial infections. Translating research into intervention. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:52–56. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paavonen J, Saikku P, Vesterinen E, Meyer B, Vartiainen E, Saksela E. Genital chlamydial infections in patients attending a gynaecological outpatient clinic. Br J Vener Dis. 1978;54:257–261. doi: 10.1136/sti.54.4.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pâces J, Urbankova V, Urbanek P. Cloning and characterization of a repetitive DNA sequence specific for Trichomonas vaginalis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;54:247–256. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasternack R, Vuorinen P, Miettinen A. Effect of urine specimen dilution on the performance of two commercial systems in the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in men. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:676–678. doi: 10.1007/BF01708358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paterson B A, Tabrizi S N, Garland S M, Fairley C K, Bowden F J. The tampon test for trichomoniasis: a comparison between conventional methods and a polymerase chain reaction for Trichomonas vaginalis in women. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74:136–139. doi: 10.1136/sti.74.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riley D E, Roberts M C, Takayama T, Krieger J N. Development of a polymerase chain reaction-based diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:465–472. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.465-472.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryu J, Chung H, Min D, Cho Y, Ro Y, Kim S. Diagnosis of trichomoniasis by polymerase chain reaction. Yonsei Med J. 1999;40:56–60. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwebke J R, Morgan S C, Pinson G B. Validity of self-obtained vaginal specimens for diagnosis of trichomoniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1618–1619. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1618-1619.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaio M F, Lin P R, Liu J Y. Colorimetric one-tube nested PCR for detection of Trichomonas vaginalis in vaginal discharge. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:132–138. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.132-138.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen A L, Porter T D, Wilson T E, Kasper G B. Structural analysis of the FMV binding domain of NADPH-cytochrome P-450 oxidoreductase by site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7584–7589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith K R, Ching S, Lee H, Ohhashi Y, Hu H-Y, Fisher III H C, Hook E W., III Evaluation of ligase chain reaction for use with urine for identification of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in females attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:455–457. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.455-457.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Schee C, van Belkum A, Zwijgers L, van der Brugge E, O'Neill E L, Luijendijk A, van Rijsoort-Vos T, van der Meijden W I, Verbrugh H, Sluiters H J F. Improved diagnosis of Trichomonas vaginalis infection by PCR using vaginal swabs and urine specimens compared to diagnosis by wet mount microscopy, culture, and fluorescent staining. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4127–4130. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4127-4130.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Werle E, Schneider C, Renner M, Volker M, Fiehn W. Convenient single-step, one tube purification of PCR products for direct sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4354–4355. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.20.4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]