Abstract

Objectives

We undertook a qualitative study to examine and compare the experience of ethical principles by telehealth practitioners and patients in relation to service delivery theory. The study was conducted prior to and during the recent global increase in the use of telehealth services due to the COVID-19 pandemic,

Methods

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 20 telehealth practitioners and patients using constructionist grounded theory methods to collect and analyse data. Twenty-five axial coded data categories were then unified and aligned through selective coding with the Beauchamp and Childress (2013) framework of biomedical ethics. The groups were then compared.

Results

Thirteen categories aligned to the ethical framework were identified for practitioners and 12 for patients. Variance existed between the groups. Practitioner results were non-maleficence 4/13 or (31%), beneficence 4/13 (31%), professional–patient relationships 3/12 (22%), autonomy 1/13 (8%) and justice 1/13 (8%). Patient data results were non-maleficence 4/12 (33%), professional–patient relationships 3/12 (33%), autonomy 2/12 (18%), beneficence 1/12 (8%) and justice 1/12 (8%).

Conclusions

Ethical principles are experienced differently between telehealth practitioners and patients. These differences can impact the quality and safety of care. Practitioners feel telehealth provides better care overall than patients do. Patients felt telehealth may force a greater share of costs and burdens onto them and reduce equity. Both patients and practitioners felt telehealth can be more harmful than face-to-face service delivery when it creates new or increased risk of harms. Building sufficient trust and mutual understanding are equally important to patients as privacy and confidentiality.

Keywords: Telehealth, general, ethics, experience, ethical, telemedicine, patient experience, clinician experience, telecare, health ethics

Introduction

Telehealth practice is the provision of health services to patients by clinicians who are not in the same physical location, through utilisation of information and communications technology. Telehealth, as a complement to face-to-face consultations, can provide benefits to patients, providers and the health system holistically, through improved access, availability and efficiency of quality health care. Ageing populations, technological advancements and the advantages of telehealth are predominant drivers for increasing investment and demand for telehealth services. The global COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was a ‘gamechanger’ for telehealth practice, as clinicians and patients sought safe ways to access healthcare. There was a significant increase in the volume of telehealth services being delivered, which exposed many more practitioners and patients to telehealth as a mode of healthcare. The expansion of telehealth was driven by the ‘Promise’ of telehealth – improved access, efficiency and clinical outcomes. The potential ‘Perils’ – the potentially negative, harmful or unethical implications of service delivery, also need also to be understood. 1

A recent systemic review identified a gap in the literature of how ethical considerations are experienced by telehealth patients and clinicians. 2 The authors reviewed 49 papers that discuss at least one or more ethical concepts in relation to telehealth practice, based on the Beauchamp and Childress framework, that is, autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, justice and the professional–patient relationship. 3

Autonomy was identified as the predominant ethical principle, and within this primary theme, several subthemes emerged, including consent, individual choice, independence, empowerment, control and self-determination.4–12

Non-maleficence, or preventing harm, was raised in relation to telehealth's ability to actively promote safety and reduce risk in patient care due to of the lack of physical proximity of the clinician. The potential for harm is more prevalent, however, and include telehealth equipment such as videophones situated in the home causing shame or embarrassment; the possibility that professional carers may choose telehealth over delivering care in person in difficult or high needs cases may put clients at risk; or an ‘undue burden’ may be imposed on unwell or frail patients who find the technology intrusive or do not fully understand it's use.6,13–28 Beneficence is discussed in relation to telehealth having the potential to benefit people by providing assurance, increasing an individual's confidence in managing their health and reducing the dependence on professional carers or family.13–15,19,22,23,25,26,29,30

Justice is most discussed in relation to fairness concerning equal access to telehealth technology, balancing the needs of the individual with those of the wider community and ensuring not to disadvantage one group in favour of another.10,13–16,18,20,22,25,29,31–33

Potential ‘disruption’ of the professional–patient relationship included sub-themes of confidentiality, privacy and fidelity and the lack of the ‘human touch’ in care.13,16–20,25,26,31–40. While a small number of qualitative studies identify relevant ethical issues associated with telehealth practice, and subsequently discuss their potential impact on service quality from the perspective of patients, carers and clinicians, there is little research on how ethical principles are experienced by clinicians and patients, or recommendation on how ethical practice may be improved.6,8,11,22,29,38 This study reduces that gap.

The time period for this research overlapped with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, corresponding to what Corbin and Strauss (2008) would identify as a ‘fortuitous event’. 41 The pandemic allowed for the discovery of “new and uncharted areas’, clinicians and patients who had never used telehealth before now participating in it. This resulted in a significant increase in the number and variety of telehealth services being delivered and exposed many more practitioners and patients to telehealth as a mode of healthcare.

The aims of the study were to understand the experience of ethical principles by telehealth practitioners and patients, examine the differences and similarities between the reported experiences of the two groups and discuss how they may impact practice. Our study had the benefit of exploring telehealth ethics from the perspective of those who had been involved pre-COVID-19 and those who, in a sense, had telehealth forced upon or ‘opened up’ to them, either as providers or clients due to the pandemic.

Methods

The study was approved by the appropriate ethics committee. Recruitment and interviews took place over a 16-month period. The sampling criteria for the research were limited to adult participants only. Practitioners were required to have delivered health services on multiple occasions to clients/ patients via telephone and/or video methods for at least 3 months prior to the study. Patients/clients were required to have received health services via telephone and/or video methods on multiple occasions over a minimum period of 3 months prior to the study. Theoretical sampling, a key element of grounded theory, aimed toward theory construction, not for population representativeness, was used. Glaser and Strauss define theoretical sampling as:

The process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analysist jointly collects, codes and analyses his data and decides what data to collect next and where to find them, in order to develop his theory as it emerges. 42

Practitioners were recruited primarily from an online telehealth community of practice and patients from a health consumer group. Selecting groups in this way described fits a criteria of ‘structural circumstance’ rather than that of ‘theoretical purpose and relevance’. 42 Glaser and Strauss propose instead the ‘ongoing inclusion of groups’ whereby the ‘fullest possible development’ of categories and their properties ‘is achieved by comparing any groups, irrespective of their difference or similarities’. The barriers to finding research participants in one single organisation, where practitioners and clients are experiencing essentially the same structural type of service, was one of ‘pre-planned inclusion and exclusion’, important if ‘accurate evidence is the goal’ but ‘hinder the generation of theory’, in which ‘non-comparability of groups is irrelevant’. 42 The approach then became one of selecting groups from the same substantive ‘class’ – that of telehealth practitioners or clients – regardless of whether they are found within a single service, or practice.

A search for telehealth client consumer groups identified state-based organisations that had established health consumer networks where participants for the study could be sourced. The largest of these was Health Consumers New South Wales (HCNSW), a membership-based, independent, not-for-profit organisation, who ‘promote and practise consumer engagement’ and ‘create meaningful partnerships between consumers, the health sector and policy-makers’. 43 They were approached an agreement to support recruitment of telehealth clients and an ethics modification was approved in August 2019 allowing recruitment to commence.

A similar search was undertaken for telehealth provider organisations or networks that were membership-based and supported research or permitted access to researchers. Membership-based organisations were chosen for two main reasons. First, because they gave access to a diverse pool of frontline practitioners who were involved in the direct delivery of healthcare and could be accessed through multiple rounds of sampling without having to seek further permissions. Second, there was reduced vested interest compared to telehealth groups linked to suppliers of technology. The organisation chosen was the Telehealth Victoria Community of Practice (TVCP) which ‘enables collaboration amongst members of the Victorian health workforce who are involved in implementing, supporting, managing and evaluating telehealth access to their health services’. 44 A further ethics modification was approved in August 2020 allowing recruitment to commence.

To ensure a diverse sample as possible, particularly in relation to the type of health services being delivered and received, social media platforms were searched for relevant groups or pages. LinkedIn and Facebook were chosen as having the relevant professional (provider) and social (client) networks, and a final ethics modification was approved in October 2020. Table 1 summarises the recruitment process for the study.

Table 1.

Summary of research participant recruitment process.

| Sampling source | Time period | Telehealth providers recruited | Telehealth patients recruited |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Consumers New South Wales (HCNSW) Newsletter and website | Round 1: August 2019 Round 2: November 2020 | 1 0 | 4 5 |

| Victorian Telehealth Community of Practice Online Forum | Round 1: August 2020 Round 2: October 2020 | 3 5 | 0 0 |

| Social media – LinkedIn and Facebook | October 2020 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 10 | 10 | |

Semi-structured interviews commenced with introductory questions about how the participant came to be delivering or receiving a telehealth service and for how long. A format regarding ‘can you talk me through how…’ was used, which allowed participants to choose ‘where they want to start’ and ‘which parts of the story they want to emphasise’. 45

A series of broad open-ended questions followed, to ‘invite detailed discussion of the topic’ and to encourage ‘unanticipated statements and stories to emerge’. 46 The interview questions were aligned with the ethical principles; however, these exact terms were not used explicitly to avoid confusion due to the relative obscurity of terms like ‘non-maleficence’, and to avoid leading questions. This allowed participants to bring their individual perspective and interpretation to the fore which then facilitated the uncovering of new elements or constructs of each principle. This approach may be perceived as ‘forcing the data into a preconceived framework’ and therefore counter to the fundamental principle of grounded theory that a researcher should be ‘constructing analytic codes and categories from data, that are not from preconceived logically deduced hypotheses’. 42 However, Charmaz argues that while ‘tensions between data collection strategies and what constitutes “forcing” are unresolved in grounded theory’. Grounded theorists often begin their studies with ‘certain guiding empirical interests‘ and ‘general concepts that give a loose frame to these interests’. 46

The interviews were conducted over Zoom, Skype or telephone and were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim into text narratives providing suitable ‘rich data’ which is ‘detailed, focused, and full’ generating ‘solid material for building a significant analysis’. 46

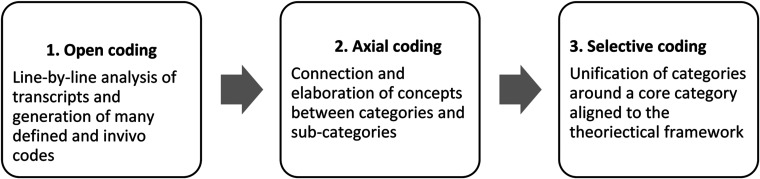

Transcripts were analysed during an iterative process of simultaneous data collection and analysis. 42 All interview transcripts were uploaded to NVivo and read alongside the audio recording of each interview to check for accuracy, and ensure they were written verbatim. Different interpretations between three analysts, one female higher degree student, and one male and one female academic, were triangulated to help gain a consensus for most themes, which added rigour to the methods. However, agreement did not always necessarily occur because of the different assumptions that are brought to the interpretation by different analysts. 47 Memos were written for each transcript, as to ‘explicate and fill out categories’ and define the key themes, concepts, thoughts and feelings for each participant. 46 The final version of each transcript was then coded in three separate steps, in order to shape an ‘analytic frame’ from which to build the analysis. 46 The three steps in the coding method were aligned with grounded theory methodology and comprised open coding, axial coding and selective coding. Step one comprised an ‘open coding’ process, where each line or section of coding was examined to determine ‘what was happening in the data, what processes are taking place and what theoretical category they imply’ 45 . This process involved both assigning specific codes to data, and in vivo coding where sections of verbatim text were then used as codes. For example, a defined category like ‘patient acceptance of technology’ was assigned as a code as it emerged from the data, and relevant text from subsequent transcripts was added to it. Verbatim comments such as ‘I don’t think telehealth can be unethical, clinicians are’, and ‘if (patients are) disclosing then clearly they feel comfortable’ were also used as codes.

Step 2 comprised an ‘axial coding’ process – a ‘focused, selective phase that uses the most significant or frequent initial codes to sort, synthesize, integrate, and organize large amounts of data’, to create new categories or expand existing ones. Corbin and Strauss (2008) define axial coding as a method for ‘crosscutting or relating concepts to each other’ 41 linking categories but also elaborating them.

Step 3 involved the comparison and alignment of categories with a core category of the theoretical framework. Each elaborated category from Phase 2 was aligned to either autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, justice or the professional–patient relationship, depending on which principle has the greatest explanatory relevance and the highest potential for linking the other categories together. 45 Figure 1 summaries the data analysis method.

Figure 1.

Summary of data analysis method.

Clinician and patient data was analysed separately to ensure differences in experience and themes could be fully exposed. The constant comparative method between and within transcripts was used, which allowed similarities and differences to be explored within the data. 48

Ten telehealth practitioners and 10 telehealth patients were interviewed between August 2019 and December 2020. The participant sample was sourced from five practice types, with practitioner experience ranging from 10 years to 3 months, across three regions of Australia. Six of the 10 had only commenced telehealth practice as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, predominantly in urban public hospital outpatient services or private practice, where face-to-face consultations had to cease. Tables 2 and 3 summarise the participant characteristics.

Table 2.

Characteristics of telehealth practitioner participants.

| ID # | Practice type | Time practicing telehealth | Service type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paramedicine | 2 years | Rural and remote public ambulance service; South Australia |

| 2 | Physiotherapist | 10 years | Urban private practice; Victoria |

| 3 | Physiotherapist | 6 months | Urban, public outpatient clinic; Victoria |

| 4 | Physiotherapist | 6 months | Urban, public outpatient clinic; Victoria |

| 5 | Occupational therapist | 9 months | Urban, rural and remote, not-for-profit service; Victoria |

| 6 | Clinical psychologist | 9 months | Urban private practice; South Australia |

| 7 | Clinical psychologist | 9 months | Urban private practice; South Australia |

| 8 | Clinical psychologist | 5 years | Urban, rural and remote private practice; South Australia |

| 9 | Clinical neuropsychologist | 3 months | Urban, public outpatient clinic; Victoria |

| 10 | Clinical psychologist | 4 years | Urban, rural and remote private practice; Queensland |

Table 3.

Characteristics of telehealth patient participants.

| ID # | Patient characteristics | Time receiving telehealth services | Service type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female, 25–35 years | 5 years | Medical (general practitioner), dietician |

| 2 | Male, 45–55 years | 3 years | Medical (general practitioner and specialist) |

| 3 | Male, 55–65 years | 12 months | Medical (general practitioner and specialist), psychology, psychiatry |

| 4 | Female, 25–35 years | 6 months | Medical (general practitioner), paediatrics |

| 5 | Female, 55–65 years | 5 months | Medical (general practitioner and specialist) |

| 6 | Female, 35–45 years | 6 months | Medical (general practitioner), psychology, psychiatry, dietician |

| 7 | Female, 55–65 years | 5 months | Medical (general practitioner), physiotherapy, diabetes management |

| 8 | Female, 35-45 years | 6 months | Medical (general practitioner), psychology, psychiatry |

| 9 | Female, 25–35 years | 6 months | Medical (general practitioner), psychology, psychiatry |

| 10 | Male, 35–45 years | 8 months | Medical (general practitioner and specialist) |

The framework for the definitions, concepts and principles of health ethics used is that provided by Beauchamp and Childress, described as ‘the set of pivotal moral principles functioning as an analytic framework of general norms derived from the common morality’. The ‘common morality’ is shared by all persons committed to morality, defined as ‘norms about right and wrong human conduct that are so widely shared that they form a stable social compact’. The common morality is

….applicable to all persons in all places and we rightly judge all human conduct by its standards, and violation of these norms is unethical, and will both generate feelings of remorse and provoke the moral censure of others. 3

Beauchamp and Childress divide these four moral principles further into related concepts or sub-themes for discussion, and I have included, as they do, the ‘obligations’ of veracity, privacy, confidentiality and fidelity in the context of professional–patient relationships. This is important because it is recognised that patients and health providers, especially doctors, ‘are really attached to their usually longstanding personal relationship’. Telehealth, with technology ‘acting as an intermediate’, is perceived to ‘potentially jeopardise’ those relationships, producing behaviour that may be unethical. 49 Table 5 summarises the framework.

Table 5.

Framework of ethical principles.

| Moral principle/concept | Definition | Related concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Respect for autonomy | Self-rule that is free from both controlling interference by others and limitations that prevent meaningly choice |

|

| Non-maleficence | The obligation to abstain from causing harm |

|

| Beneficence | The moral obligation to act for the benefit of others |

|

| Justice | Fair, equitable and appropriate distribution of benefits and burdens |

|

| Professional–patient relationships | Relationships in clinical practice, research involving human subjects and public health |

|

Open coding resulted in 210 separate categories of data. Axial coding produced 25 categories that are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Coding and categorisation of patient and practitioner data.

| Selective coding | Axial coding – clinicians | Axial coding – patients |

|---|---|---|

Autonomy

|

1. Telehealth provides a greater choice of access to health services and supports person-centred care | 1. Access and choice are improved for some patients but reduced

for others. 2. Telehealth can give patients more power and control in their relationships with practitioners. |

Beneficence

|

2. The growth of telehealth illuminates poor clinical practice

and is a catalyst for change. 3. Telehealth saves time and allows more efficient use of resources. 4. The inclusion of home and family helps build rapport and embed positive behavioural change. 5. Continuity of care and keeping patients in place improves outcomes for the community. |

3. Patients feel they receive more thorough care and are ‘listened to’ over telehealth |

Justice

|

6. Telehealth alleviates isolation and the distance to care for remote communities. | 4. Improved access to services must be balanced against the cost of technology and the potential for over-servicing |

Non-maleficence

|

7. Guidelines and policies are incomplete, inadequate or

absent. 8. Telehealth creates new and unforeseen risks for practitioners, patients and carers. 9. Practitioners are poorly prepared for telehealth which impacts welfare and quality of care. 10. Adapting to the technology is confusing and stressful and hinders good clinical practice. |

5. Practitioners provide inferior or less adequate care than

patients expect through telehealth. 6. Technology is unpredictable and can limit or exclude patients’ access to care. 7. Improved physical safety needs to be balanced against psychological harms and risks. 8. Less open conversations over telehealth leads to reduced disclosure and understanding of patient needs. |

Professional–patient relationships

|

11. Communication challenges are greater, preventing effective

rapport building, understanding and trust. 12. Human interaction and comfort of the physical presence are missing. 13. Privacy and confidentiality are more difficult to assure for both practitioners and patients. |

9. Practitioners can put their needs first and behave less

professionally over telehealth. 10. There is a greater risk of miscommunication, reduced trust and patients not fully expressing themselves. 11. Feeling support or reassurance is more likely face-to-face than over telehealth. 12. Patients don't trust that telehealth is private, but neither is face-to-face. |

Selective coding aligned the categories with the ethical principles of the theoretical framework. 3 Categories aligned to the ethical framework were found for both groups but varied within groups.

Results

Practitioner results were: non-maleficence 4/13 or (31% of the practitioner data categories), beneficence 4/13 (31% of the practitioner data categories), professional–patient relationships 3/12 (22% of the practitioner data categories), autonomy 1/13 (8% of the practitioner data categories) and justice 1/13 (8% of the practitioner data categories). Patient data results were non-maleficence 4/12 (33% of the patient data categories), professional–patient relationships 3/12 (33% of the patient data categories), autonomy 2/12 (18% of the patient data categories), beneficence 1/12 (8% of the patient data categories) and justice 1/12 (8% of the patient data categories).

The practitioner experience – autonomy

- 1. Telehealth provides greater choice of access to health services and supports person-centred care includes themes of patient-centred services, client acceptability, self-care, introducing patients to telehealth and ease of use. Choice is expressed by psychologists, in the context of comfort, independence and security for clients, especially for those who normally wouldn’t be comfortable in a clinical setting:…Clients seem more relaxed and comfortable over telehealth, and I want them to be more relaxed and comfortable, it gives me a truer sense of what is going on with them and they are more open. (Practitioner 9)

Patient acceptance of technology was also raised in relation to choice and control. Practitioners acknowledge that for some demographic groups, particularly older people or those who are vulnerable, telehealth is a challenge:

…with the older patients, it's pretty tricky when they're not technology savvy, like they accidently mute the call, they can’t turn on the video, they can't flip the camera. (Practitioner 8)

One psychologist noted that some of her ‘reluctant’ patients eventually agreed to use telehealth because it was the only way to access care, deciding they ‘needed the help more than they disliked using the technology’. (Practitioner 6) Patient-centred care was mentioned in the context of disability services where practitioners emphasised not providing ‘a one size fits all approach’, but rather ‘really trying to accommodate what our client's preference was’. (Practitioner 5)

Non-maleficence

- 1. Guidelines and policies are incomplete, inadequate or absent included themes of policies, guidelines, legal issues and accountability. All practitioners commented that, regardless of how long they had been practicing, telehealth guidelines, policies and protocols were incomplete, inadequate or simply lacking altogether. When COVID-19 restricted the use of face-to-face care, practitioners looked to their professional bodies for guidance, or accessed tutorials or training from platform providers, with mixed results:…because there weren’t any guidelines I had to speak with a lot of the psychiatrists that had delivered up services via telehealth. (Practitioner 10)

An occupational therapist providing services to visually impaired clients, found that of the guidance that was available ‘pretty much none of it was appropriate for our cohort’ (Practitioner 5)

- 2. Telehealth creates new and unforeseen risks for practitioners, patients and carers included themes of patient and clinician safety, the therapeutic space and carer's fatigue. In terms of patient safety, some practitioners thought they still needed to be checking ‘exactly the same safety issues as they would normally’. In telehealth, ‘any inkling’ that the people they are seeing, or the topics of conversation that they are discussing ‘might have safety implications, needs to be addressed and discussed within the first five minutes’. Safety is also often mentioned in terms of the practitioners’ ability to control the home environment, what they see and hear and what they can influence:..It's always in the back of my mind that there may be something dangerous or something going on that I don't have much control over. (Practitioner 1)

Knowing exactly where patients are and how to get help to them if necessary was concerning for psychologists:

… I did have one situation of a police officer who contacted me one night, and she was suicidal, but she refused to tell me where she was. (Practitioner 7)

Telehealth can have the effect of forcing people to find a safe space for themselves that is a ‘therapeutic space’ within their home, providing a ‘layer of safety’ to be able to talk freely. If a safe space cannot be found, practitioners can gain an insight into some of the issues that a client may not express, leading to more effective and personal care. (Practitioner 8)

Managing risk with telehealth is mentioned both in terms of patient and practitioner safety. The potential that they may not be able to ‘control a situation’ was a concern for psychologists and making sure they were able to contact an emergency person was extremely important. (Practitioner 10) Unreliable technology or connections means practitioners have to be prepared for situations to suddenly deteriorate and results in ‘that little bit more stress because you've got to think a bit quicker when you're on the telehealth just in case the phone line goes down’. (Practitioner 10)

The safety of the practitioner was also raised, particularly with those who had recently become involved with telehealth. Physiotherapists agreed that telehealth was safer for them than face-to-face sessions. (Practitioner 2)

The concept of carer's fatigue was mentioned in relation to visually impaired clients, as the preparation of materials for sessions, normally done by a therapist, had to be done by someone in the client's home:

… a few practitioners did say, “we're quite wary of carer's fatigue, we don't want to impose too much on someone's carer, or family member, on top of everything else”. But we didn't at that time put together sort of any mitigating strategies around that. (Practitioner 5)

3. Practitioners are poorly prepared for telehealth which impacts well-being and quality of care included themes of introduction to telehealth, training, confidence, choice and challenges. If practitioners are poorly prepared for telehealth the quality of care they are able to deliver, and potentially their own welfare can be negatively impacted. For a rural ambulance service, paramedics were not consulted about the introduction of telehealth and had to develop their own ways of working. (Practitioner 1)

For physios working in a public outpatient clinic, their introduction to telehealth came as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. They describe it as being somewhat chaotic and stressful, particularly in relation to informing patients:

I think because it all happened so quickly with COVID everyone was just focused on getting the function up. We all felt that it was a sort of “the blind leading the blind rule”, just doing what we felt was right. (Practitioner 4)

Training is a crucial aspect of preparing for telehealth, and most practitioners accessed either little or no formal training, or training that was inadequate. A paramedic described their training as ‘very little - really just a half an hour in-service training package online’. While some received ‘orientation to the platform’ they were to use, most learned through their own and their peer's ‘shared knowledge’. (Practitioner 4) Due to the suddenness of lockdowns and the need to get telehealth service up rapidly, the lack of training and formal processes resulted in ‘shock and doubt’ for some. (Practitioner 3)

- 4. Adapting to the technology is confusing, stressful and hinders good clinical practice included themes regarding the type and quality of technology, and which to use, technical support and back up. Making decisions about which platforms to use in telehealth consults involves weighing up factors such as accessibility, cost, ease of use for clinicians and patients, reliability and security from hacking. In many practices, clinicians have found themselves having to act as both technology advisors and trouble-shooters for clients:..our practitioners did find that it was quite challenging to kind of quickly learn and adapt to get an idea of how each platform would best work. (Practitioner 5)

Beneficence

- 1. The growth of telehealth illuminates poor clinical practice and is a catalyst for change included themes around the differences between face-to-face and telehealth clinical practice, improving practice and the evidence base for telehealth. There was some disparity over whether telehealth practice required different clinical skills or not. One clinician felt that:the way practitioners are practicing currently can just be transferred and will be as effective via a different modality, is a very incorrect assumption. (Practitioner 2)

A psychologist delivering predominantly rural and remote services for over 4 years suggested a continuum of clinical skills enhancement that helped her refine her practice and develop transferrable skills. This began by ‘mastering the art’ of telephone coaching and counselling, so that when she moved to telehealth practice having a video link ‘was a walk in the park’, comparatively. (Practitioner 10)

For physiotherapists used to seeing patients in Hospital clinics, and dependent on physical touch, manipulation of bodies and demonstrating exercises, the sudden move to telehealth required some innovative adaptions to their practice. While setting up a video call, moving the camera and communication with clients was not particularly difficult, they found themselves doing ‘a lot more gestures and mirroring’, showing patients exercises on camera and then asking them to do it. While younger patients found this ‘pretty easy’, it can be ‘tricky’ for older people, requiring a change to the approach. (Practitioner 4)

Ways to improve telehealth clinical practice were also reported by some practitioners. Recording and peer review of consultations was strongly advocated by one, arguing that the effective way to improve clinical practice was to ‘get people to audio record the consult and listen back to an audit on the processes and the skills that they use’. She noted that while the mechanisms for ‘personal skills reflection’ have always been there, there is ‘very little desire on the health system front to use those mechanisms’, due to clinician reluctance. (Practitioner 9)

One psychologist suggested that if COVID-19 had a ‘silver lining’ it was to force their practice more into the telehealth space, noting that ‘psychologists are very wedded to the scientist practitioner model, the empirical evidence is a really important part of it’. The lack of widespread use of telehealth has not provided that empirical support in the past, but the pandemic has reversed the normal evidence-based approach, ‘It's now the experience rather than research that's feeding back through’. (Practitioner 7)

2. Telehealth saves time and allows more efficient use of resources included themes of costs and benefits, and from a positive perspective is expressed in terms of saving time, better use of resources and flexibility for practitioners. In supporting visually impaired clients, mobility and orientation instructors travel widely and are often ‘hands-on in the training sessions, with absolutely no availability for any other client’. Telehealth enables them to efficiently deliver services ‘to someone who's maybe just having a relatively simple aftercare concern”. For psychologists in private practice, the convenience of not having to drive to offices is “a really big positive factor’ as is the ‘quicker turnaround time’ of not having to see clients out and bring the next one in. Some negative impacts on efficiency were also noted, mainly due to issues with setting up sessions, connections dropping out, or sessions lasting longer than they otherwise would, due to communication issues. Funding arrangement and increased overheads were another cost for practitioners, with psychologists expected to reduce fees or ‘bulk bill’ due to Medicare subsidies, while having to pay administration staff to schedule and send out links to online platforms. (Practitioner 10)

3. The inclusion of home and family helps builds rapport and embed positive behavioural change includes themes of being able to see patients in the home environment and involve family and carers directly in consults. This is perceived as positive both through the lens of improving rapport, helping to design treatment and embedding behaviours. For physiotherapists, being able to see how patients move around their own homes was reported to be a significant benefit. (Practitioner 4)

One psychologist commented that younger male clients are particularly benefiting from the use of telehealth in her practice, seeming to be ‘more verbose, more open, more willing to share’ in their home environment, attributing this to the more casual, familiar setting being ‘maybe a little less intimidating’, ‘a little less uncomfortable, than sitting in an office’. (Provider 7)

4. Continuity of care and keeping patients in place provides improved outcomes for the community included themes of continuity of care, continuous improvement, feedback and professional development. In remote areas of Australia where are large distances between major hospitals, health emergencies can lead to long and traumatic travel experiences, involving both road and air transport. Extending telehealth further into those communities can provide a continuity of care and potentially reduce the number of times people need to leave their areas for treatment. (Practitioner 1) Understanding the client experience to inform continuous improvement is recognised as important by practitioners but has been occurring haphazardly. While acknowledging that ‘permanent feedback mechanisms’ are needed to ‘build onto monitoring and evaluation’, most did not collect client experience data at all.

Justice

1. Telehealth alleviates isolation and the distance to care for remote communities included themes of reducing isolation and equity of access. For rural and remote communities, not just access to health services but time spent travelling or away from home and family can be alleviated by the use of telehealth. This also alleviated the sense of isolation remote communities have. (Practitioner 1) One psychologist noted that there are ‘very limited’ mental health services in regional and remote areas and ‘none, basically none’ in very remote areas. For clients driving ‘four and a half hours for a fifty-minute session, staying overnight and then driving back’, telehealth ‘saved a whole day of their lives’. (Practitioner 8)

Professional–patient relationships

1. Communication challenges are greater, preventing effective rapport building, understanding and trust included themes of communication barriers, the use of small talk and video versus phone. Practitioners experienced challenges communicating with clients over telehealth, particularly those who were older, or who spoke a different language. Elderly patients ‘may not accept telehealth’, translators may be difficult to access, and the skill of the patient in navigating the technology can also have a significant impact, especially for those involved in physical therapy. (Practitioner 4)

Connections dropping out, unstable platforms, the client's ability to switch off the camera or lags in timing also caused headaches, particularly for psychologists interacting with vulnerable clients:

…when you're working with kids or teens they play around with the video, they switch it over or they pause it, particularly the ones that are into self-harming. (Practitioner 10)

Some practitioners found using telehealth during COVID-19 easier, as they could work from home and didn’t have to wear PPE, as ‘wearing our masks and glasses and things can limit communication as well’. Some made the choice to use telehealth for that reason, finding it ‘less intrusive than masks’. (Practitioner 7)

Practitioners reported how their use of ‘small talk’, or introductory communications, to put patients at their ease was impacted by the use of telehealth . With face-to-face sessions, there is a ‘natural 30 s’ when people are moving from waiting rooms into the clinical space where talk about ‘the weather, or the drive in’ normally occurs. Some practitioners felt that, as sessions were taking longer over telehealth, they had less time for ‘chit-chat, while others spent more time than they would otherwise’. Longer time spent was mainly due to orienting patients to the ‘why and how to use’ the technology or overcoming ‘the awkwardness of a telehealth appointment’. (Practitioner 3)

The difference between using telephone and video for telehealth was mentioned by some practitioners. For physiotherapists, using video was the ‘closest thing we can get to face-to-face’, finding consults where patients are ‘just giving you feedback or information’ over telephone, ‘presumably less accurate’. (Practitioner 3)

For a psychologist servicing rural and remote clients, there is ‘an awful lot that has to happen through telephone that just can't, when you can't see someone’ including interpreting ‘how distressed patients are’. (Practitioner 6) There is also the ‘the great mental fatigue” that came from “switching your senses on in a different way’. (Practitioner 10)

Patient demographics and patient choice can also determine what methods practitioners use. Younger people are ‘very comfortable to walk around with their phones even and be talking while walking’. Some clients choose telephone over video if they're ‘set up in bed in their pyjamas and they don’t want the bother of going to get their PC’. For older clients, unused to the technology, telephone is just as effective. (Practitioner 10)

2. Human interaction and comfort of the physical presence are missing included themes of the comfort of a physical presence, human interaction and the changed nature of the relationship. Most practitioners felt very strongly that face-to-face interactions with patients were superior to telehealth, but many struggled to express why. For paramedics, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, being able to touch a patient was integral to the way they delivered care, and also to their own identity as health professionals. Patient expectations of the service, and trust were also raised by one physiotherapist, feeling that using telehealth ‘takes away from the full treatment that you would normally be giving them’. She could also ‘build a stronger rapport’ and ‘connect a bit deeper’ with patients ‘through trust with you being able to touch them’. (Practitioner 3).

For psychologists, face-to-face sessions better enabled them to deliver quality care, as there is ‘something about that that you can't replace with telecommunication’. Some spoke about the value of communication nuances such as facial and bodily cues, ‘the whole perception’, that is not possible through telehealth, which ‘changes the dynamic of that therapeutic relationship’. (Practitioner 6)

Another psychologist spoke of the ‘comfort of a physical presence’ in face-to-face sessions and the fact that patients are ‘with someone whose job is to care, to think about their psychological position’. One believed it is essential when delivering telehealth services that ‘we're not forgetting that sense of connectivity to each other and other people’ because it's harder to let them see that you're authentic and real and you're compassionate over a video than what it is face-to-face. (Practitioner 10)

3. Privacy and confidentiality are more difficult to assure for both practitioners and patients included themes of privacy, confidentiality, recording of video and audio and the drivers of privacy concerns. Most practitioners acknowledged that ensuring complete privacy is not possible given ‘we are on the Internet and it's only as secure as the server is’. One noted that ‘in telehealth you can’t always control the environment.’ They take various measures to negate privacy concerns from both their and the client's perspectives through ‘overt checking’ of who is in the room, including ‘calling it out’ if there are interruptions, and ‘holding people accountable’ to preparing as if it were a face-to-face session. (Practitioner 5) Practitioners need to trust what clients are saying, but ‘you don't have that one hundred percent confirmation that they're alone and that it is private’. Others acknowledge that patients can’t always fully control their own home environment and see the need for flexibility. (Practitioner 10)

The issue of what drives concerns over privacy in telehealth was raised by some practitioners, who are ‘not so sure that there are people out there who want to listen to other people's health conversations’. While acknowledging a ‘Zoom bomb’ by a third party would be ‘entirely inappropriate’, some doubt that many patients are as concerned as ‘a lot of legislators are’. (Practitioner 2) The emphasis should be on making sure ‘the platform we use is secure, and the data we hold is secure’, and ‘that's about it.’ (Practitioner 7)

The issue of recording consultations over telehealth is also somewhat controversial. Some practitioners have had no direction or ‘any instruction’ regarding it and never explicitly state to clients, ‘I don't record this, this can't be recorded or it's OK to record things’. One physiotherapist commented that a few patients ‘here and there’ asked if she could record ‘me doing an exercise or a demonstration’ for them. A psychologist mentioned that it was more common for clients to ask to record in face-to-face sessions, rather than over telehealth. (Practitioner 2)

The patient experience – autonomy

- 1. Access and choice are improved for some patients but reduced for others included themes of choice, access to services and lack of alternatives to telehealth. Choice was linked to convenience for several patients, enabling better use of their time and easier coordination of appointments:…I would get up in the morning and think, “oh, look, I don't have to travel today, I just have to wait for the phone call”. (Patient 10)

For a mother, whose son is living with a disability, the option to use telehealth made caring choices easier:

…. on the days when he's not well, it's very hard to get him out of the house. Having telehealth means he gets the care and support that he needs rather than having to reschedule for a face to face. (Patient 8)

If distance were a barrier to accessing services, patients valued having the choice, and the ability to access health services anywhere, even at work, improved a patient's ability to manage their conditions. The option to access face-to-face care should be ‘always be available’, if patients felt that it was ‘warranted’. Choice should not be at the discretion of health professionals. (Patient 5) One patient accessing mental health services was concerned that Governments would perceive telehealth as ‘a cheaper option’ and restrict access to other options such as face-to-face care. (Patient 9) For someone who is predominantly bed bound or otherwise severely disabled, and with home visits by general practitioners either ‘not an option’ or ‘ridiculously expensive’, it's ‘either telehealth or go without’. (Patient 1)

- 2. Telehealth can give patients more power and control in their relationships with practitioners included themes of patients having more control and power in using telehealth, both in relation to managing their interactions with health professionals, and by having to become more self-reliant. One patient felt less vulnerable when accessing psychological services, finding telehealth gave them more control over the process, and less power to clinicians:…you're not as vulnerable as in a room, that's their space, that's their domain, they have the power. I can't just leave. (Patient 8)

Another benefited from being able to engage with a health professional in an environment that suited her therapeutically, like ‘a really calming place, like bushland’ (Patient 9)

Telehealth also permits vulnerable patients to have a support person attend a consultation much more easily ‘to help me through, especially when you're having a poor mental health episode’ (Patient 5).

Non-maleficence

1. Practitioners provide inferior or less adequate care than patients expect through telehealth included patients reporting that ‘you're not actually getting the same level of care’ through telehealth compared to face-to-face. One patient described the care she was receiving from her GP over telehealth as ‘rubbish care’, resulting in her avoiding treatment for her condition. (Patient 6). Another described a telehealth consult with his GP as ‘just ticking the boxes’. (Patient 10)

Not being physically present with a patient meant that doctors ‘miss a lot’. The sign of a ‘good doctor’ was to ‘see the whole person, not just treat symptoms’. Important physical or emotional cues like ‘nervousness or demeanour’, are not observed ‘when all you can see is a talking head’. The lack of physical interaction could also lead to misdiagnosis, or people avoiding care altogether. (Patient 5)

2. Technology is unpredictable and can limit or even exclude access to care. One patient who has physical disabilities and has relied on telehealth for many years found it ‘very hard to predict if it's a day when the technology is going to work or whether the technology isn’t going to work’. Although she was ‘used to it’, her concern was that health providers would stop telehealth services altogether because ‘they’re much more likely to be super frustrated and not know what to do or just want to give up straight away’. (Patient 1)

When technology ‘collapses’, patients report not knowing what to do. As well as being disruptive, they feel ‘excluded’ from meetings when audio or video doesn’t work properly. (Patient 8) Those with reduced access to a network, or able to only use a mobile phone, found telehealth ‘imited’, and ‘becoming too dependent on it is a concern’. (Patient 9)

3. Improved physical safety needs to be balanced against psychological harms and risks included both positive and negative themes. Not having to attend clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic was ‘a big weight off’ for one patient who didn’t ‘have to go and expose myself or expose my son to other people sitting in the waiting room’. (Patient 4)

Patients accessing mental health services reported mixed feelings about safety. One felt quite comfortable with her psychiatrist on telehealth but unsafe with her psychologist because ‘if things went bad, she couldn't help me because she wasn't with me’. (Patient 9)

Another patient questioned ‘how well they could assess my psychological safety over telehealth versus in person, and whether they would be able to pick up that risk’. (Patient 6)

4. Less open conversations over telehealth leading to reduced disclosure and understanding of patient needs:

One patient reported being frustrated because ‘all the normal cues you use in conversation, like when to talk’ are not as apparent. (Patient 9) Another felt that increased levels of discomfort in communication over telehealth led to ‘less genuine conversations and less emotional connection’. (Patient 8)

Patients also reported the sharing of home lives, either their home lives being shared with others, or them seeing into provider's home lives, as causing stress and concern. Some providers, such as psychologists, attempted to explain changes to their normal environment with anxious patients:

…she would always tell me at the beginning where she was. And if it was strange, then she would explain why. (Patient 6)

One patient reported that her ‘anxiety increases’ at the thought of people seeing into her home if she is unable to ‘get a background’ for a video meeting, because that's ‘a very private thing for me’. (Patient 8)

Beneficence

1. Patients feel they receive more thorough care and are ‘listened to’ over telehealth, included themes of increased flexibility and effort of providers using telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic, and greater thoroughness of clinical care. Telehealth enabled continuity of care to occur where it otherwise may not have been able to, due to distance or restrictions. The ‘lack of exposure’ to waiting rooms also provided some peace of mind to fearful people in a pandemic. One patient also felt ‘more listened to’ and ‘really heard’ over telehealth compared to a face-to-face meeting with her general practitioner. (Patient 4)

Justice

1. Improved access to services needs to be balanced against the cost of technology and the potential for over-servicing included the theme of telehealth providing equity of access to health services for people who may otherwise struggle to do so. Telehealth could be ‘lifesaving’ for those with mental health issues who find it difficult to leave their homes. (Patient 5)

Physical activity such as strength training sessions over video would also be beneficial for nursing home residents where ‘the people can’t go to the gym or they're in wheelchairs’. Barriers exist, however, for the elderly who ‘can't use modern technology’, and those who are visually or hearing impaired. The cost to access telehealth was also seen as a barrier to access as participating assumes ‘that people have access to all the high tech that you need and to the Internet, which is quite costly’. (Patient 8)

The concept of fairness was reported by patients in relation to sharing of benefits and burdens. Being able to access a variety of technology rather than one preferred or mandated by a health provider was of value to one patient. Another found that telehealth forced doctors to be more strict or careful with their time as they must initiate calls, rather than having patients waiting in clinics for them. One patient reported feeling concerned about the potential for telehealth to lead to over-servicing, in the case of doctors who ‘had lost 90% of their face-to-face consultations’ during the pandemic. (Patient 5)

Professional–patient relationships

1. Practitioners put their needs first and behave less professionally over telehealth included themes of not knowing where providers are, wasting patient's time and not being adequately prepared for a telehealth consultation. Not knowing where a health professional was during telehealth consultations was reported by patients as being a concern. This was linked to expectations that they gave patients their full attention, as well as issues concerning safety and security. (Patient 5)

Patients expected that providers would ‘explain where they are, whether they're at home or in their office, I think it's just good to have a sense of where they are’. (Patient 6) One found telephone sessions particularly difficult for that reason, as she ‘didn’t know if they’re there or not, you don't know what they're doing’. (Patient 9) Health professionals should disclose where they are from a privacy perspective; often ‘it's a conversation that just doesn't happen’. (Patient 8)

Another patient wanted rules ‘around where a doctor could consult.’ While acknowledging that during a pandemic ‘doctors were not going into their clinics for safety reasons’,

… you shouldn't be able to be stirring the pot in the kitchen or supervising your kids or in the car and doing something on your mobile phone with no video. (Patient 5)

Patients also reported their time being wasted due to poor time keeping by doctors, exacerbated by a lack of technology infrastructure in clinics, and inadequate communication. Patients reported health professionals not being prepared for telehealth consults, including being ‘hopeless’ with the technology, allowing interruptions to sessions, or rushing conversations. (Patient 5)

One patient reported that the lack of confidence by providers using telehealth caused her stress and anxiety, as her GP ‘still has not been able to get it to work with me’ after several months. Patients expect that clinicians are ‘confident in what they're doing or at least appear to be comfortable with it ’. (Patient 6)

Patients reported ‘annoying’ behaviour by providers such as ‘leaving the room to go and let the dog out or close a window‘. (Patient 6) Interruptions with GP consultations also caused frustration when ‘you'll get a knock on the door and it's a receptionist assuming you're on a phone call. But it breaks the sequence. It breaks the flow’. (Patient 8)

2. There is a greater risk of miscommunication, reduced trust and patients not fully expressing themselves included themes of miscommunication, confusing gaps and silences in conversations, or patients not feeling they could adequately express themselves. (Patient 10). Telehealth ‘didn't seem as though they were real consultations’, or that ‘the person at the other end was fully engaged’ or ‘really knew what they were supposed to be talking about’. (Patient 5)

Others reported missing out on ‘a lot’ with telehealth, including the ‘with-it-ness’ from emotional readings and facial expressions. (Patient 4) Another felt that ‘you miss out on all that body language and all the micro expressions are completely gone’. (Patient 8)

Another patient reported finding communicating with mental health professionals over telehealth ‘in general’, very difficult, and found telehealth was akin to a physical barrier. (Patient 9) Patients also reported the nature of ‘chatting’ or ‘small talk’ with their health providers was altered when telehealth was used. (Patient 10)

For some patients, seeing the provider's face was important for communication, and preferred video to telephone ‘so that you can see where the person is and that they fully engaged with you’. (Patient 6)

3. Feeling supported or reassured is more likely face-to-face than over telehealth was reported by patients, although the reasons for stating this varied. One who is predominantly housebound due to disability preferred it ‘partly because you don’t have to worry about all the technical stuff’, but also to ease loneliness. (Patient 1)

Another reported that ‘if it's a case of somebody who has limited mobility or can't get to a doctor for geographic or other reasons’ telehealth ‘is better than nothing’. However, ‘you can't, in my opinion, replace face to face consultations, all the cues that you would get sitting with someone’. (Patient 5) Providing support or reassurance to patients was more effective face-to-face than over telehealth. (Patient 4) A patient receiving psychological services over telehealth reported ‘keeping myself in check more, there's more self-care, self-responsibility’ when becoming emotional, due to the lack of a physical support presence. (Patient 8)

4. Patients don't trust that telehealth is private, but neither is face-to-face included varying degrees of concern about privacy and confidentiality. For some the risk was either low, or equivalent to a face-to-face consultation. One patient felt there was an important difference between the expectation of ‘perfect’ privacy and likelihood that no-one would be ‘interested enough’ to breach it. (Patient 1) Some providers made concerted effort to reassure patients, moving the computer ‘around the room, because they were working from home, to try and show me that it was private’. (Patient 6) Another patient, who reported once receiving someone else's test results, felt that ‘privacy and confidentiality has been a factor for a long time’, that telehealth isn’t any more susceptible or liable to breaches than “the old method”. (Patient 3)

Some patients are concerned about the privacy and confidentiality of telehealth, the potential for hacking and ‘what happens to the recordings’. (Patient 8) One patient stated that privacy concerns should be ‘raised up front and dealt with by the health professional’ and then ‘if the person's not that bothered, you can move on’. (Patient 6)

Discussion

Patients and practitioners all reported experiencing situations, instances or phenomea associated with ethical principles while providing or receiving health services via telehealth. However, those reported experiences were either slightly or substantially different.

In relation to autonomy, both participant groups reported that telehealth provided a greater choice to access health services, but patients felt that choice could be limited by demographic factors such as age, ethnic background and income. There is evidence to support the patient’s claim that the social determinants of health have often been found to restrict access to health services in general and specifically for telehealth. 50 Perhaps, the most salient point is that the practitioners did not highlight this ethical challenge. Patients also reported an increased experience of power and control when using telehealth. This suggests that telehealth may be more ethical than traditional health service delivery regarding autonomy.

The principle of non-maleficence requires that health professionals not inflict harm on patients, impose the risk of harms and take ‘due care’. 3 For patients, the reporting of experiences regarding risk of harm from telehealth was much greater. Practitioners reported that they were poorly prepared for telehealth, including a lack of useful guidelines and training. This was more prevalent in those who had commenced telehealth practice solely as a response to the pandemic. Patients experienced this lack of skill and preparedness as provision of a lower standard of clinical care than they required, but it also resulted in increased levels of stress for practitioners. Telehealth created new risks in practice, particularly for mental health clinicians, who felt they could not always adequately control environmental hazards. Mental health patients also reported feeling less psychologically safe when using telehealth, compared to being physically in a room, as the clinician was not physically present with them. Both groups reported that the use of the technology required to deliver telehealth could also cause harm through poor user experience, unfamiliarity with the functionality, adapting to different platforms and limited access to technological support when it failed. 4 This harm manifested itself as anxiety, stress and the avoidance of sessions where the clinician did not seem confident with the technology.

In relation to beneficence, practitioners reported more phenomena of positive beneficence than patients. Practitioners reported that telehealth could positively influence clinical practice overall, by highlighting the inadequacies of current systems, such as record keeping. They reported that telehealth enables continuity of care where patients wanted to live, and allows for family, carers and the home environment to be included in treatment, which provides benefits to the broader community. However, only a third of patients articulated how telehealth provided ‘good care’ for them. This was predominantly reported in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, where health professionals put additional protocols in place to ensure clinical standards were maintained. The majority of patients felt that reduced clinician preparedness, attention to detail and thoroughness of examinations did impact their perception of the level of clinical care. Both groups reported similar instances of improved utility from telehealth, as patients and practitioners were able to save time and resources through reduced travel to attend clinics. Overall, from the perspective of preventing or removing harm and promoting good, and the balancing of benefits, risks and costs, the patient data suggests that telehealth presents ethical issues in delivering quality care.

Both practitioner and patient data resulted in one category for justice, but the perspectives were different. For practitioners, justice was reported as an increased ability for patients to equally access health services, regardless of distance or physical isolation from care. For the patient group, distributive justice was more important. There was a strong concern that costs to access technology was unfair and burdensome for patients, and that GPs, in particular, were using telehealth to supplement their income during the pandemic, when there was no clinical need. Regarding justice, therefore, telehealth practice may present ethical issues from the patients’ perspective.

Practitioners and patients were most aligned when reporting experiences of professional–patient relationships. Categories relating to increased barriers to communication and, the importance and drivers of concerns around privacy and confidentiality, were comparable. Challenges to veracity in the context of building rapport, mutual understanding and trust were similar because communication was less effective for both patients and clinicians. Patients reported experiencing concerns with fidelity, the duty of health professionals to act in the best interests of the patient, rather than putting their own needs first This was in relation to inappropriate billing of time as well as unprofessional behaviour during consultations, such as cooking meals or letting the dog out. From the perspective of professional–patient relationships, the data again suggests that telehealth may present ethical issues, particularly for patients.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Scope of the thesis

The intention of undertaking this research was originally to examine the ethical use of telehealth in a focused way. We hoped to compare a cohort of clinicians with a cohort of patients who were participating in delivering or receiving the same service. This approach would produce results that were empirically strong and applicable for that service and allow for a relatively easy and effective knowledge translation. The inability to find an organisation willing or able to partner in a reasonable timeframe led us to broaden the scope of the research by recruiting clinicians and patients from a range of services, which added depth to the data and types of experiences and perspectives. However, it may also have diluted the ability to contextualise the findings for a specific organisation.

Timeliness of the thesis

When we commenced this research in 2018 Australian Government-funded access to telehealth was limited to rural and remote services whose practitioners had developed models of care and expertise over several years. With the COVID-19 pandemic occurrence, the majority of face-to-face health services were suspended and new cohorts of clinicians – general practitioners, Specialists, allied health professionals – were ‘thrown in’ to using telehealth. While the rushed nature of pivoting to telehealth meant that services remained available, many clinicians were not well prepared, supported or even enthusiastic to use telehealth. As one physiotherapist said, ‘there wasn’t a part of starting telehealth that I wasn’t worried about’ (Practitioner 3). In some cases, it was ‘the blind leading the blind”’ (Practitioner 4). This may have distorted the data to the extent of these practitioners appearing ‘less ethical’ than those who had been practicing for longer, in a way that accentuated the negatives.

Sample size/sample bias

These groups were initially chosen due to the lack of evidence in the literature of the experience of both groups, which means that the groups chosen had both ‘common factors and relevant differences’ with both being involved in telehealth service delivery, one group as providers of a service and one group as receivers. Limitations in scope, as mentioned above, coupled with the small number of participants who met the selection criteria for length of practice resulted in a somewhat narrow range of experiences since delivering telehealth services. Practitioners were either very new (6 months or less) to telehealth due to COVID-19 or had been practicing for a comparatively much longer time (greater than 2 years). While this disparity was useful in surfacing some of the systemic and longer-term issues for telehealth practice, it present challenges in transferring the finding more generally to populations. The same applied, although to a lesser degree, with the patient cohort

Data collection

Data collection was limited to qualitative methods. It would have been beneficial to include a quantitative study of a larger group of both patients and practitioners to add further depth to the analysis and potentially form the basis of a broader longitudinal study. Again, this approach was limited by time, resources and access to research participants.

To conclude, our study supports a number of assumptions of how ethical principles are experienced in telehealth practice. We found that ethical principles are often experienced differently by telehealth practitioners and patients, and these differences can impact the quality and safety of care. Also, practitioners perceived telehealth provides better care overall than patients do, however, both reported similar levels of improved utility. Access to telehealth services may not be fair and equitable; increased utilisation may force a greater share of costs and burdens onto patients. Telehealth can be more harmful than face-to-face health service delivery as it creates new or increased risk of harms for both patients and practitioners. Finally, building sufficient trust and mutual understanding as part of the professional–patient relationship is equally or more important to patients as privacy and confidentiality. There remains a strong desire from both clinicians and patients, however, to realise the ‘Promise’ that telehealth represents, while minimising the ‘Peril’. This study, and further research in ethical telehealth service delivery, can assist them to do so.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Health Consumers New South Wales in facilitating access to their consumer group, and Telehealth Victoria Community of Practice for providing access to their member forum.

Footnotes

Contributorship: The authors provided have the entire authorship of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Australian Postgraduate Award.

Ethical approval: Ethics approval was provided by the Flinders University Social and Behavioural Research Ethics Committee (SBREC) in December 2018 (Project no. 8156).

Informed consent: Written consent was obtained from all research participants prior to the commencement of the research.

Guarantor: AJK.

ORCID iDs: Amanda Jane Keenan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1121-1228

Jennifer Tieman https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2611-1900

Trial registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Thede LQ. Telehealth: promise or peril? Online journal of issues in nursing [electronic resource] 2001; 6: 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keenan AJ, Tsourtos G, Tieman J. The value of applying ethical principles in telehealth practices: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e25698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Priciples of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demiris G, Oliver DP, Courtney KL. Ethical considerations for the utilization of telehealth technologies in home and hospice care by the nursing profession. Nurs Adm Q 2006; 30: 56–66. 11p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisk MJ, Rudel D. Telehealth and service delivery in the home: Care, support and the importance of user autonomy. 2014, p.211–225.

- 6.Glueckauf RL, Maheu MM, Drude KP, et al. Survey of psychologists’ telebehavioral health practices: technology use, ethical issues, and training needs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2018; 49: 205–219.. Article. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan B, Litewka S. Ethical challenges of telemedicine and telehealth. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 2008; 17: 401–416. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mort M, Roberts C, Pols J, et al. Ethical implications of home telecare for older people: a framework derived from a multisited participative study. Health expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy 2015; 18: 438–449. 2013/08/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newton MJ. The promise of telemedicine. Surv Ophthalmol 2014; 59: 559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palm E, Nordgren A, Verweij M, et al. Ethically sound technology? Guidelines for interactive ethical assessment of personal health monitoring. Stud Health Technol Inform 2013; 187: 105–114. 2013/08/08. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Percival J, Hanson J. Big brother or brave new world? Telecare and its implications for older people's Independence and social inclusion. Critical Social Policy 2006; 26: 888–909. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schermer M. Telecare and self-management: opportunity to change the paradigm? J Med Ethics 2009; 35: 688–691. 2009/11/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaet D, Clearfield R, Sabin J, et al. Ethical practice in telehealth and telemedicine. J Gen Intern Med 2017; 32: 1136–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornford T, Klecun-Dabrowska E. Ethical perspectives in evaluation of telehealth. Cambridge quarterly of healthcare ethics : CQ : the international journal of healthcare ethics committees 2001; 10: 161–169. 2001/04/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eccles A. Ethical considerations around the implementation of telecare technologies. J Technol Hum Serv 2010; 28: 44–59. 16p. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleming DA, Edison KE, Pak H. Telehealth ethics. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association 2009; 15: 797–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gogia SB, Maeder A, Mars M, et al. Unintended consequences of tele health and their possible solutions. Contribution of the IMIA working group on telehealth. Yearb Med Inform 2016: 41–46. Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humbyrd CJ. Virtue ethics in a value-driven world: ethical telemedicine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2019; 477: 2639–2641. Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iserson KV. Telemedicine: a proposal for an ethical code. Cambridge quarterly of healthcare ethics : CQ : the international journal of healthcare ethics committees 2000; 9: 404–406. 2000/06/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langarizadeh M, Moghbeli F, Aliabadi A. Application of ethics for providing telemedicine services and information technology. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina) 2017; 71: 351–355. 2017/12/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loute A, Cobbaut JP. What ethics for telemedicine? In: The digitization of healthcare: new challenges and opportunities. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017, pp.399-416. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perry J, Beyer S, Francis J, et al. Ethical issues in the use of telecare. UK: Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutenberg C, Oberle K. Ethics in telehealth nursing practice. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2008; 20: 342–348. 347p. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarhan F. Telemedicine in healthcare 2: the legal and ethical aspects of using new technology. Nurs Times 2009; 105: 18–20. 3 November 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skar L, Soderberg S. The importance of ethical aspects when implementing eHealth services in healthcare: a discussion paper. J Adv Nurs 2018; 74: 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voerman SA, Nickel PJ. Sound trust and the ethics of telecare. Journal of Medicine & Philosophy 2017; 42: 33–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willems D. Advanced home care technology: moral questions associated with an ethical ideal. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands Centre for Ethics and Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson E-L, Davis K, Velasquez SE. 4 - Ethical considerations in providing mental health services over videoteleconferencing. Telemental health: Clinical, technical, and administrative foundations for evidence-based practice 2013: 47–62. USA: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holmstrom I, Hoglund AT. The faceless encounter: ethical dilemmas in telephone nursing. J Clin Nurs 2007; 16: 1865–1871. 2007/09/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shea K, Effken JA. Enhancing patients’ trust in the virtual home healthcare nurse. Cin-Computers Informatics Nursing 2008; 26: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Botrugno C. Towards an ethics for telehealth. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26: 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Demiris G, Doorenbos AZ, Towle C. Ethical considerations regarding the use of technology for older adults: the case of telehealth. Res Gerontol Nurs 2009; 2: 128–136. 129p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson WA. The ethics of telemedicine. Unique nature of virtual encounters calls for special sensitivities. Healthc Exec 2010; 25: 50–53. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barina R. New places and ethical spaces: philosophical considerations for health care ethics outside of the hospital. In: HEC Forum. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht, 2015, pp.93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheshire WP. Telemedicine and the ethics of medical care at a distance. Ethics and Medicine 2017; 33: 71–75. Article. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Draper H, Sorell T. Telecare, remote monitoring and care. Bioethics 2013; 27: 365–372. 2012/04/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kluge EHW. Ethical and legal challenges for health telematics in a global world: telehealth and the technological imperative. Int J Med Inf 2011; 80: E1–E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pols J. The heart of the matter. About good nursing and telecare. Health Care Anal 2010; 18: 374–388. Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stanberry B. Legal ethical and risk issues in telemedicine. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2001; 64: 225–233. Ireland. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stowe S, Harding S. Telecare, telehealth and telemedicine. Eur Geriatr Med 2010; 1: 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. Calif, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co., 1967. [Google Scholar]