Abstract

Strains of Candida albicans obtained from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals prior to their first episode of oral thrush were already in a high-frequency mode of switching and were far more resistant to a number of antifungal drugs than commensal isolates from healthy individuals. Switching in these isolates also had profound effects both on susceptibility to antifungal drugs and on the levels of secreted proteinase activity. These results suggest that commensal strains colonizing HIV-positive individuals either undergo phenotypic alterations or are replaced prior to the first episode of oral thrush. They also support the suggestion that high-frequency phenotypic switching functions as a higher-order virulence trait, spontaneously generating in colonizing populations variants with alterations in a variety of specific virulence traits.

Most strains of Candida albicans and related species are capable of switching spontaneously, reversibly, and at high frequencies (10−4 to 10−1) between a number of general phenotypes distinguishable by colony morphology (14, 49, 50, 52, 56). Several lines of evidence suggest that switching plays a significant role in pathogenesis. First, switching has been demonstrated to regulate an ever-increasing number of phase-specific genes, some of which have been implicated in pathogenesis (53, 54, 56). The list for C. albicans includes the secreted aspartyl proteinase genes SAP1 and SAP3 (17, 21, 30, 31, 32, 68), the drug resistance gene CDR3 (4), the white phase-specific gene WH11 (22, 62), the opaque phase-specific gene OP4 (31), the two-component histidine kinase regulator gene CaNIK1 (63), the transcription factor gene EFG1 (61, 64), and a number of new genes that have not been fully characterized (56). Second, switching has been demonstrated to regulate a number of phenotypic characteristics involved in pathogenesis (52). The list includes antigenicity (1), constraints on the bud-hypha transition (2), sensitivity to neutrophils and oxidants (20), adhesion (19, 67), secretion of aspartyl proteinase (32), and virulence in a mouse systemic model and a mouse cutaneous model (21, 22). Third, switching has been demonstrated at sites of infection (58, 59). Fourth, results from several studies have demonstrated that infecting isolates switch at significantly higher frequencies, on average, than commensal isolates (16), and that isolates causing deep mycoses switch, on average, more frequently than isolates causing superficial mycoses (18).

To investigate further the links between high-frequency phenotypic switching and pathogenesis, we compared switching in isolates collected before, during, and after the first episode of oral thrush in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients with that in control isolates collected from healthy, HIV-negative individuals. We then tested the switch phenotypes of freshly isolated strains for levels of expression of secreted aspartyl proteinase and susceptibilities to antifungal drugs. Our results demonstrate that the proportions of colony variants in Candida populations collected before, during, and after the first episode of oral or esophageal thrush are 2 orders of magnitude higher than that in commensal populations collected from healthy individuals. Switching in the strains obtained from HIV-positive individuals in turn was found to affect dramatically the levels of secreted aspartyl proteinase and drug susceptibilities. These results demonstrate that the average strain of C. albicans colonizing the oral cavity of HIV-positive individuals prior to the first episode of oral thrush and prior to antifungal therapy is already in a high-frequency mode of phenotypic switching and is already more resistant to a number of common antifungal agents than the average commensal strain colonizing healthy individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Collection of isolates.

A total of 54 HIV-positive individuals voluntarily enrolled in the study between July 1994 and July 1996: 48 from the Infectious Diseases Clinic at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City; 4 from the William Beaumont Army Hospital, Fort Bliss, El Paso, Tex.; and 2 from the Bering Dental Clinic, Houston, Tex. Seventy-five percent were male, and 25% were female. All subjects were initially free of signs or symptoms of oral candidiasis or other mucosal disease, and all had CD4+ lymphocyte counts of greater than 200 cells per mm3 at the beginning of surveillance. A total of 24 healthy, presumably HIV-negative individuals also enrolled in the study.

A sample was collected from test individuals at each of three oral locations: the buccal mucosa (B), the floor of the mouth (F), and the dorsal surface of the tongue (T). Samples were first coded according to location of collection: Fort Bliss (FB), Houston (H), or Iowa City (I). Samples were then coded according to test individual number (1, 2, 3, and so forth), the time of sampling (prior to the first episode of oral thrush, during the first episode of oral thrush, or after antifungal therapy [a, b, and c, respectively]), and the oral location of collection (B, F, or T). If several samples were obtained at different times before, during, or after thrush, they were labeled 1, 2, or 3, respectively, after the appropriate letter a, b, or c. Therefore, sample FB1a2F represents the second sample obtained from the floor of the mouth of patient 1 prior to an episode of thrush at the William Beaumont Army Hospital, Fort Bliss, El Paso, Tex.

Each sample was collected by passing a sterile cotton swab (Culturette; Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) several times across the particular oral surface. Immediately after sampling, each swab was replaced in its sterile containment tube and moistened with sterile salt solution by crushing the glass barrier in the tube. The containment tubes were transported within 2 h of sampling from the place of collection to the laboratory. The cotton end of each swab was inserted into 0.5 ml of sterile water in a polypropylene test tube and vigorously mixed for 30 s with a vortex mixer. A 0.15-ml sample of the swab wash was spread onto each of two agar plates containing supplemented Lee's medium (7). This agar was formulated to evaluate phenotypic switching (52) and supports the growth of all tested yeast species but Caudida glabrata (26, 27). A 0.15-ml sample was spread on a CHROMagar plate (Hardy Diagnostics, Santa Monica, Calif.) for primary species typing (33, 36). This agar supports the growth of all yeast species. This procedure resulted in three plates for each of the three sampled oral locations. The agar plates containing supplemented Lee's medium were incubated for 7 days at 25°C, while the CHROMagar plate was incubated for 48 h at 37°C.

When more than one colony morphology was present on a culture dish, at least one colony exhibiting each morphology was streaked onto an agar storage slant containing supplemented Lee's medium and stored for subsequent analysis. To assess the genetic homogeneity of clonal populations, multiple colonies with the same colony morphology from selected primary plates were individually streaked onto agar slants and stored for subsequent analysis. In all cases, cells from each streaked colony were examined microscopically to verify that they were yeast colonies.

Typing of yeast species was performed with the IDS rapid yeast identification system (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) or the Vitek YBC automated yeast identification system (BioMerieux, St. Louis, Mo.). In both cases, manufacturer instructions were followed.

Assessing phenotypic switching.

The proportion of minor phenotypes in primary cultures plated on supplemented Lee's medium was measured. To assess switching in secondary cultures, cells from a storage streak originating from one colony in the primary culture were suspended in 1,000 μl of sterile water. Cells were counted with a hemocytometer and serially diluted in sterile water to a final concentration of 103 cells per ml. A 100-μl volume, containing 100 cells, was then spread on each of 10 agar plates containing supplemented Lee's medium. Plates were incubated at 25°C for 7 days and then scored for colony phenotype (3, 49, 50, 52). The average number of colonies per plate was approximately 70.

Fingerprinting C. albicans isolates with probe Ca3.

The complex DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 (2, 25, 41, 44, 55) was used to assess the genetic relatedness of C. albicans isolates by methods previously described (28, 40, 48). In brief, cells from agar storage slants were streaked on agar containing 2% dextrose, 2% Bacto-Peptone, 1% yeast extract, and 2% agar and incubated for 48 h at 25°C. DNA was then prepared by the method of Scherer and Stevens (46), and the concentrations were determined with a fluorometer. DNA was digested with EcoRI and electrophoresed in an 0.8% agarose gel overnight at 35 V. DNA from reference strain 3153A was run in the outer lanes of each gel. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide to compare loading between lanes. DNA was then transferred by capillary blotting to a nylon Hybond-N+ membrane (Amersham, Piscataway, N.J.) and hybridized with a random-primer-labeled ([32P]dCTP) probe. The membrane was washed at 45°C and exposed to XAR-S film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, N.Y.) with a Cronex Lightning-Plus intensifying screen (Du Pont Co., Wilmington, Del.). DNA hybridization patterns were digitized into the DENDRON software program (version 2.0; Solltech Inc., Oakdale, Iowa) based in a Macintosh computer. The methods for automatic processing and analysis of Southern blot hybridization patterns have been described in detail recently (55). Similarity coefficients (SAB) were computed by a formula based on band positions only, and dendrograms were generated by the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages (51).

Proteinase activity.

Cells were streaked from agar storage slants onto Sabouraud dextrose agar plates and incubated at 25°C for 24 h. One colony from each plate was inoculated into a 50-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 25 ml of Sabouraud dextrose broth and cultured at 25°C in a gyratory incubator for 48 h at 200 rpm. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min and resuspended in 25 ml of sterile distilled water. Bovine serum albumin (BSA; Cohn fraction V; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.)-containing agar plates were made according to the methods described by Staib (65). In brief, a solution containing 2% glucose, 7.3 mM KH2PO4, 4.1 mM MgSO4 and 2% agar (pH 4.5) was sterilized. After it was cooled to 50°C, filter-sterilized BSA and 100× minimum essential medium vitamins (Flow Laboratories, Inc., McLean, Va.) were added to concentrations of 1.0% (wt/vol) and 1×, respectively. The mixtures were poured into plates and cooled. Resuspended cells were counted with a hemocytometer and adjusted to 108 cells per ml. Each plate was inoculated with a 5-μl aliquot of the cell suspension and incubated at 37°C for 96 h in a humidified incubator. The colony phenotype was verified by plating 10 μl of the cell suspension on a Lee's medium-supplemented agar plate and incubating the plate for 7 days at 25°C. The plates were then flooded with 20% trichloroacetic acid for 20 min and washed briefly with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.0). The plates were stained with 0.6% amido black in methanol-acetic acid-distilled water (45:10:45) for 10 min and destained with the same solution lacking amino black for 30 min. After destaining, the plates were allowed to air dry for 24 h and then were examined with backlighting for clear zones around the colonies. The diameter of the clear zone surrounding each colony was measured with a Boley gauge. All assays were conducted in triplicate.

Antifungal susceptibility.

Cells from storage slants were grown on potato dextrose agar plates for 24 h at 30°C. Suspensions were prepared from individual colonies with 5 ml of sterile 0.85% saline to a density of a 0.5 McFarland standard (37, 43). Two quality control organisms that had well-defined macrodilution MIC reference ranges for amphotericin B, flucytosine, and fluconazole (Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and C. albicans ATCC 90028) were included in each experiment. Amphotericin B (E. R. Squibb & Sons, Princeton, N.J.), fluconazole (Roerig-Pfizer, New York, N.Y.), 5-fluorocytosine (5FC) (Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., Nutley, N.J.), nystatin (Sigma), clotrimazole (Sigma), and voriconazole (Roerig-Pfizer) were obtained as reagent-grade powders from their respective manufacturers. Microdilution trays containing serial dilutions of the antifungal agents in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) were prepared in a single lot and stored frozen at −70°C prior to use. The analysis was performed according to the guidelines set by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (43) for the spectrophotometric method of inoculum preparation, with an inoculum concentration range of 0.5 × 103 to 2.5 × 103 cells per ml and RPMI 1640 medium buffered to pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (Sigma). One hundred microliters of yeast inoculum was added to 100 μl of antifungal drug solution (2× final concentration) in each well of the microdilution trays. Final concentrations of the antifungal agents were 0.12 to 4.00 μg/ml for amphotericin B, 0.03 to 2.00 μg/ml for nystatin, 0.12 to 128.00 μg/ml for fluconazole, 0.06 to 64.00 μg/ml for 5FC, and 0.007 to 8.000 μg/ml for voriconazole and clotrimazole. The trays were incubated in air at 35°C and analyzed for the presence or absence of growth at 24 and 48 h. After the wells had been agitated, spectrophotometric readings of each well were obtained with a Biowhittaker Microplate 2001 reader (Anthos Labtec Instruments, Salzburg, Austria) at 492 nm. MIC endpoints were determined as the first concentration of the antifungal agent at which turbidity in the well was at least 50% less (5FC, fluconazole, voriconazole, and clotrimazole) or at least 90% less (amphotericin B and nystatin) than that in the control well (38).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using a Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance for ranks and Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests. Significant differences were noted as P values of <0.05. When pairs of data were evaluated, the Student t test was used.

RESULTS

The average proportion of variant colonies in primary cultures from HIV-positive patients is elevated.

Of 54 HIV-positive patients, 43 (80%) tested positive for oral yeast. The colony phenotypes on primary agar plates containing supplemented Lee's medium (7) were assessed, regardless of whether these patients subsequently presented with thrush. The primary plates for 38 patients (88%) contained at least two different colony morphologies, while those for only 5 patients (12%) contained one colony morphology. Of 24 healthy control individuals, 12 tested positive for oral yeast. None of the primary plates for the 12 control individuals with yeast contained more than one colony phenotype. These results demonstrated that, on average, colonizing populations of yeast in the oral cavity of HIV-positive individuals were phenotypically heterogeneous, while those of healthy individuals were phenotypically homogeneous.

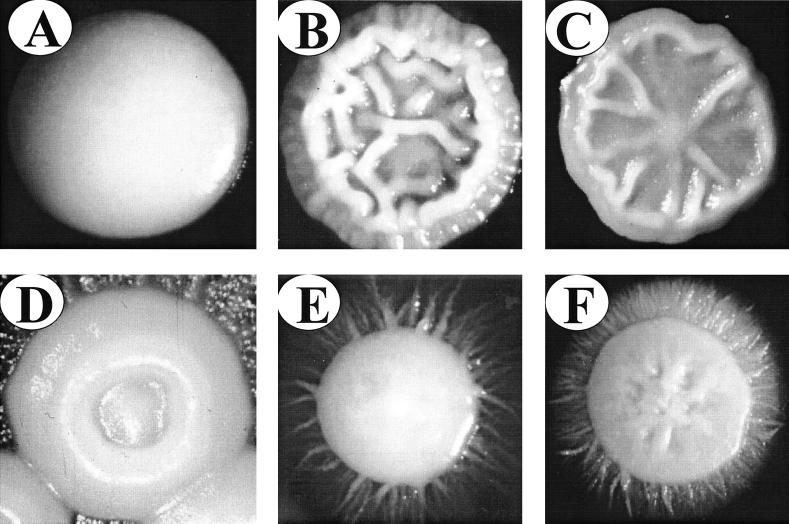

Eleven HIV-positive patients presented with oral thrush during surveillance. The major phenotype and the proportions of minor phenotypes in the primary cultures of nine of these patients (I1, I2, I3, I4, I5, H1, H2, FB3, and FB4) were assessed before, during, and after their first episode of oral thrush. Data could not be collected from primary cultures for 2 of the 11 patients (FB1 and FB2) because of the very high densities of colonization. In seven of the nine primary cultures that could be analyzed (78%), the proportion of colonies exhibiting a minor phenotype before the first episode of thrush was greater than 5 × 10−2 (Table 1). The mean proportion of colonies exhibiting minor phenotypes for the nine patients before the first episode of thrush was 1.6 × 10−1 (Table 1). The dominant phenotype in six of the nine primary platings was smooth white. In three cases, however, the dominant phenotype was heavily myceliated or myceliated (Table 1). The smooth white phenotype is shown in Fig. 1A, and examples of variant phenotypes are shown in Fig. 1B through F.

TABLE 1.

Proportions of minor phenotypes in primary isolates collected before, during, and after the first episode of oral thrush in HIV-positive individuals and in primary isolates collected from healthy control individuals

| Individual | Before thrusha

|

During thrusha

|

After thrusha

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of colonies (per six plates) | Fraction of minor phenotypes | Major phenotype | Minor phenotype(s) | No. of colonies (per six plates) | Fraction of minor phenotypes | Major phenotype | Minor phenotype(s) | No. of colonies (per six plates) | Fraction of minor phenotypes | Major phenotype | Minor phenotype(s) | |

| HIV-positive patients | ||||||||||||

| I1 | 42 | <2 × 10−2 | myc | — | 3,212 | 2.0 × 10−2 | myc | hm | 335 | 3.6 × 10−2 | myc | sw, hm |

| I2 | 641 | 1.1 × 10−1 | myc | hm, sw | 2,213 | 4.5 × 10−4 | hm | sw | 311 | <3.0 × 10−3 | hm | sw |

| I3 | 109 | 7.2 × 10−2 | sw | iw, st, myc | 2,050 | 1.4 × 10−2 | sw | hm, myc | 1,014 | 3.5 × 10−1 | myc | sw |

| I4 | 78 | 4.2 × 10−1 | sw | hm | 600 | 1.7 × 10−3 | sw | — | 155 | 1.8 × 10−1 | sw | hm |

| I5 | 60 | 2.7 × 10−1 | sw | hm | 480 | 1.7 × 10−1 | hm | sw | 208 | 8.9 × 10−2 | myc | sw, hm |

| H1 | 380 | 5.6 × 10−2 | sw | hm, myc | 3,050 | 1.6 × 10−2 | sw | myc | NDb | |||

| H2 | 530 | 3.0 × 10−1 | sw | hm | 1,520 | <7.0 × 10−4 | sw | — | 315 | 6.0 × 10−3 | sw | hm |

| FB3 | 120 | 1.8 × 10−1 | sw | hm | 780 | <1.3 × 10−4 | sw | — | ND | |||

| FB4 | 215 | <5 × 10−3 | hm | — | 520 | <1.9 × 10−3 | sw | — | ND | |||

| Mean ± SD | 241 ± 222 | 1.6 × 10−1 ± 4.2 × 10−1 (1.5 × 10−1c) | 1,603 ± 1,083 | 2.5 × 10−2 ± 5.5 × 10−2 (4.7 × 10−2c) | 389 ± 314 | 1.1 × 10−1 ± 1.4 × 10−1 (1.7 × 10−1c) | ||||||

| Healthy control (C1–C12)d | 1,005e (avg, 83) | <10−3 | sw | |||||||||

Phenotypes: sw, smooth white; myc, myceliated; hm, heavily myceliated; iw, irregular wrinkle; st, star; —, no minor phenotype. Because primary plates also contained bacteria that affected yeast colony size, smooth white versus petite smooth white (psw) were not differentiated, as in secondary platings.

ND, not determined.

When no minor phenotypes were identified in primary platings, 1 was divided by the total number of colonies to obtain a maximum estimate of the fraction of minor phenotypes.

The average proportion was computed by dividing the total number of minor phenotypes by the total number of colonies scored for nine patients.

Total number of colonies.

FIG. 1.

Examples of some of the general colony phenotypes in the switching systems of C. albicans strains colonizing HIV-positive individuals. (A) Smooth white. (B) Irregular wrinkle. (C) Star. (D) Ring. (E) Myceliated. (F) Heavily myceliated. Cells were grown to a low density on supplemented Lee's medium (6) for 7 days at 25°C.

The proportion of minor phenotypes in the primary cultures of these nine HIV-positive patients differed markedly from that of the 12 control individuals. In all of the latter cases, the phenotype of the oral commensal was uniformly smooth white and the mean frequency of variants was estimated to be <10−3, a value at least 2 orders of magnitude lower than that for the nine HIV-positive patients prior to an episode of thrush (Table 1).

During the first episode of oral thrush, the mean intensity of colonization increased sevenfold and the proportion of minor phenotypes in the primary cultures of four of the nine HIV-positive patients remained very high. The mean proportion of minor phenotypes was 2.5 × 10−2, at least 25 times higher than the mean proportion in primary cultures for the nine control individuals (Table 1). After the first episode of oral thrush, the mean intensity of colonization decreased fourfold, but the proportion of minor phenotypes in the primary cultures was again high in four of the six patients from whom samples were obtained. The mean proportion of minor phenotypes was 1.1 × 10−1, 2 orders of magnitude higher than that in cultures for the control individuals (Table 1).

In secondary platings, cells from individual storage streaks of well-distinguished single colonies from primary cultures were replated. The mean proportion of minor phenotypes was again high for isolates obtained before, during, and after the first episode of thrush. The mean proportions in secondary platings were 8.6 × 10−2, 4.4 × 10−2, and 6.5 × 10−2, respectively (Table 2). Secondary platings of 12 random clones from primary platings of control isolates were also performed. The average proportion of variant phenotypes was 3.3 × 10−3 (data not shown), more than 1 order of magnitude less than that in cultures for HIV-positive individuals. The differences between the mean proportions of minor phenotype in cultures from HIV-positive and control individuals were significant, with P values of <0.05.

TABLE 2.

Proportions of minor phenotypes in secondary platings of isolates collected before, during, and after the first episode of oral thrush in HIV-positive individuals

| Patient | Before thrusha

|

During thrusha

|

After thrusha

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction of minor phenotypes | Major phenotype | Variant phenotype(s) | Fraction of minor phenotypes | Major phenotype | Variant phenotype(s) | Fraction of minor phenotypes | Major phenotype | Variant phenotype(s) | |

| I1 | 3.1 × 10−1 | myc | wr, hm, st, r, psw | 4.7 × 10−2 | myc | sw, psw | 2.5 × 10−2 | myc | sw, psw |

| I2 | 7.8 × 10−3 | myc | psw, nip | 4.4 × 10−2 | swb | myc, psw | 9.9 × 10−3 | swb | myc, psw, nip |

| I3 | 2.9 × 10−3 | sw | psw | <1.4 × 10−3 | sw | — | 9.9 × 10−4 | swb | psw |

| I4 | 6.8 × 10−3 | sw | psw, wr | 9.5 × 10−2 | sw | wr | NDc | ||

| I5 | <1.4 × 10−3 | sw | — | <1.4 × 10−3 | sw | — | 2.0 × 10−1 | swb | psw, myc, wr |

| H1 | 3.6 × 10−1 | hmb | sw, st, wr | 2.3 × 10−1 | swb | myc, hm, iw | ND | ||

| H2 | 8.9 × 10−2 | mycb | sw | 1.4 × 10−3 | sw | psw | 9.0 × 10−3 | sw | myc |

| FB1 | 9.0 × 10−2 | hm | sw, st, psw, iw | 2.5 × 10−2 | sw | psw | 4.9 × 10−2 | hm | sw, st |

| FB2 | 4.1 × 10−2 | wr | sw, hm, myc | 3.0 × 10−2 | myc | sw, wr | 1.5 × 10−1 | myc | sw, psw, wr |

| FB3 | 2.0 × 10−2 | sw | myc, psw | 6.9 × 10−3 | hmb | wr | ND | ||

| FB4 | 1.2 × 10−2 | hm | sw, wr, stip | 4.6 × 10−3 | sw | wr | ND | ||

| Mean ± SD | 8.6 × 10−2 ± 1.3 × 10−1 | 4.4 × 10−2 ± 6.8 × 10−2 | 6.5 × 10−2 ± 7.8 × 10−2 | ||||||

See Table 1, footnote a, for explanations of most phenotypes; stip, stippled; nip, nippled; psw, petite smooth white; wr, wrinkled.

The phenotypes of the secondary platings in these cases differed from those of the primary platings. There are two possible explanations. First, when a switch phenotype is stored, there is often enrichment of another switch phenotype after growth and maintenance, the likely explanation for these results. Second, bacteria in the original cultures can alter phenotype.

ND, not determined.

Variant phenotypes reflect switching even when the colonizing yeast population includes multiple strains.

The primary plating experiments demonstrated that the proportion of variant colony morphologies in colonizing populations of HIV-positive individuals was, on average, 2 orders of magnitude higher than that in colonizing populations of control individuals. Although the results of the secondary plating experiments indicated that many of the variant phenotypes in primary platings of the samples from HIV-positive individuals were the result of switching, some of the colony variability also could have been due to colonization by multiple strains. To test strain heterogeneity, several individual clones from primary cultures for each of the 11 individuals with thrush were fingerprinted with the complex DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 (48). Ca3 is specific for C. albicans (44) and has been demonstrated to be effective in distinguishing between completely unrelated strains, in identifying the same strain in different samples, in identifying microevolution within a strain, and in grouping moderately related isolates in cluster analyses (40, 55).

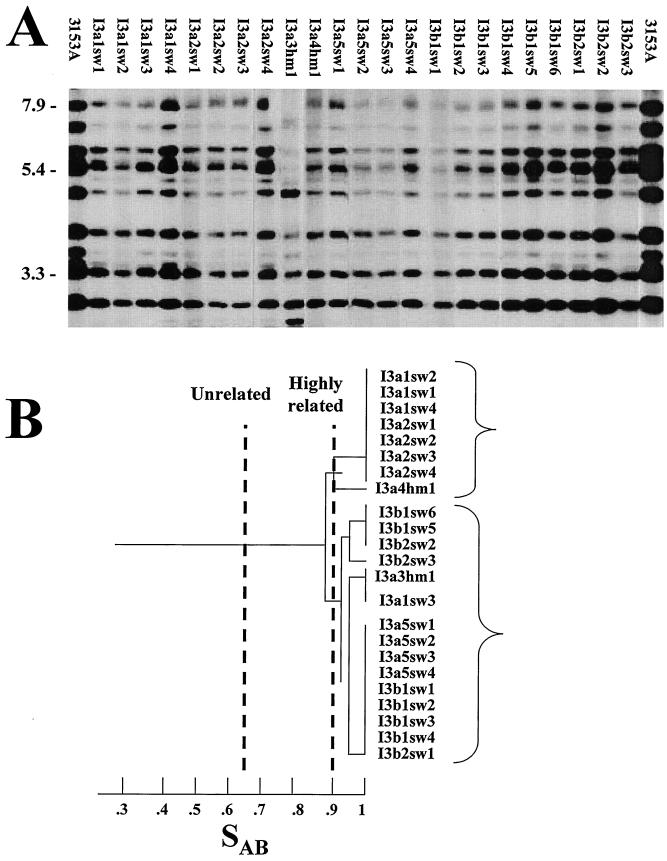

Southern blot hybridization patterns were compared between every pair of isolates in a test group by calculating the SAB based on band position alone. An SAB of 0.69 represents unrelatedness, an SAB between 0.90 and 0.99 reflects highly similar patterns, and an SAB of 1.00 indicates identical patterns (55). For 4 of the 11 collections of isolates from HIV-positive individuals with oral thrush (FB2, FB3, FB4, and I3), the DNA fingerprints of all isolates, including those with variant phenotypes, were similar or identical (i.e., exhibited an SAB of ≥0.90); this result demonstrated carriage of a single strain prior to, during, and subsequent to the first episode of thrush. All of these isolates exhibited elevated levels of switching in secondary platings. An example of the fingerprinting patterns of the collection of isolates from patient I3 is presented in Fig. 2. Prior to the first episode of thrush, 14 clones, including 12 smooth white and 2 heavily myceliated, exhibited similar or identical Ca3 hybridization patterns. During the first episode of thrush, nine smooth white clones shared the same pattern (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Southern blot hybridization patterns generated with the Ca3 probe for clones isolated from patient I3 (A) and the dendrogram generated from SAB measurements (B). Molecular sizes in kilobases are noted to the left of the Southern blots. The threshold SAB for considering isolates unrelated and highly related (56) are indicated by broken lines. Two major clusters with a node separating them at an SAB of 0.88 are indicated by brackets to the right of the dendrogram. The last number of each isolate designation refers to the individual clone. Pattern images in this case were unwarped, straightened, and normalized with DENDRON software.

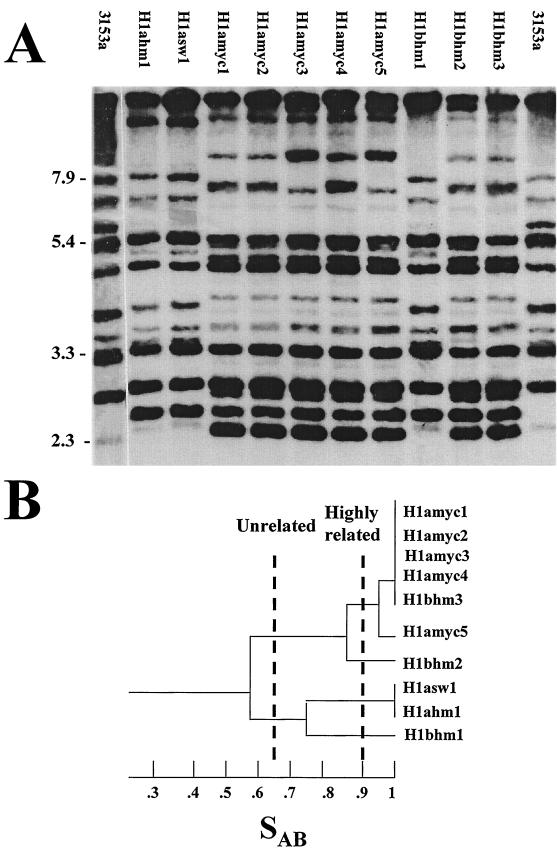

For 2 of the 11 collections of isolates from HIV-positive individuals with thrush (I4 and H1), multiple clusters were separated in dendrograms by nodes well below an SAB of 0.90. In each patient collection, genetically distinct isolates included multiple phenotypes. This fact is evident in the phenotypes and fingerprint patterns of clones isolated from patient H1 (Fig. 3A). Prior to the first episode of thrush, the patient had two genetically distinct strains, one that expressed a smooth white and a heavily myceliated phenotype and a second that expressed a myceliated phenotype. Separation of the two strains is apparent at an SAB of 0.57 (Fig. 3B). During the second episode of oral thrush, the strain that had exhibited only a mycelial phenotype during the first episode now also expressed a smooth white phenotype, and a third strain, Hlbsw8, appeared in the population.

FIG. 3.

Southern blot hybridization patterns generated with the Ca3 probe for clones isolated from patient H1 (A) and the dendrogram generated from SAB measurements (B). Molecular sizes in kilobases are noted to the left of the Southern blots. The thresholds for considering isolates unrelated and highly related (56) are indicated by broken lines. The last number of each isolate designation refers to the individual clone.

In the collections from the remaining five HIV-positive individuals with thrush, four involved strain replacement, but in each case, multiple colony phenotypes were present for each strain (data not shown). These results demonstrated that even though yeast populations colonizing the oral cavity of HIV-positive patients sometimes included genetically unrelated strains, the individual strains exhibited high proportions of variant phenotypes, indicating high frequencies of switching.

Proteinase activity varies as a function of colony morphology.

Based on the observation that switching in vitro regulates a variety of putative virulence traits and putative virulence genes (52, 56), including the expression of at least two proteinase genes, SAP1 and SAP3 (17, 21, 30, 31, 32, 68), we examined whether the variant phenotypes of the strains isolated from HIV-positive patients differed in secreted proteinase activity.

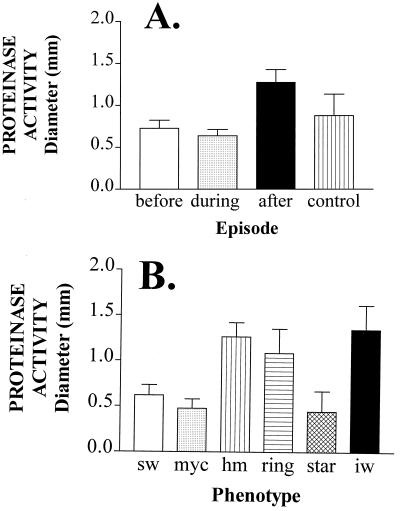

The average proteinase activities of isolates collected before and during the first episode of oral thrush were statistically indistinguishable from one another as well as from those of isolates from healthy control individuals (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4A). However, the average proteinase activity of isolates obtained from individuals after the first episode of thrush was significantly higher than that of isolates obtained before or during the first episode or from healthy individuals (P < 0.05).

FIG. 4.

Mean proteinase activities of isolates collected before, during, and after the first episode of oral thrush in HIV-positive individuals (A) and of isolates exhibiting different colony morphologies (B). Activity is also presented for control isolates (A). Proteinase activity was measured as the diameter of the cleared zone around a colony on BSA-containing agar. sw, smooth white; myc, myceliated; hm, heavily myceliated; iw, irregular wrinkle. The numbers of isolates analyzed before, during, and after the first episode were 162, 184, and 173, respectively. The number of control isolates analyzed was 40. The numbers of sw, myc, hm, ring, star, and iw isolates analyzed were 180, 110, 103, 52, 53, and 61, respectively.

Proteinase activity, however, varied dramatically among colony phenotypes. While the average proteinase activities computed from the pooled data for the smooth white, star, and myceliated phenotypes of all analyzed isolates were relatively low, the average activities computed from the data for heavily mycelial, irregular wrinkle, and ring were relatively high (Fig. 4B). The differences between the proteinase levels in the former and latter groups were statistically significant (P < 0.001). Even more dramatic differences in proteinase activity existed between switch phenotypes of the same strain. In Fig. 5, the proteinase activity is presented for variant phenotypes of each of three strains from patients H2, FB2, and I4. For the strain from patient H2, irregular wrinkle released 3 times more activity than smooth white, heavily myceliated, ring, and star (Fig. 5A); for the strain from patient FB2, irregular wrinkle released 6 times more activity than smooth white and 25 times more activity than myceliated (Fig. 5B); for the strain from patient I4, myceliated and heavily myceliated released approximately 4 times more activity than smooth white (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that variant phenotypes that are either dominant or appear frequently in C. albicans populations colonizing HIV-positive individuals release higher levels of proteinase, on average, than the smooth white phenotype, which represents the dominant phenotype of populations colonizing healthy individuals. However, it should also be noted that although the averaged data for phenotypes suggest that particular general phenotypes (e.g., heavily myceliated, ring, and irregular wrinkle), on average, release high levels of proteinase activity (Fig. 4B), variability was observed between the same variant phenotypes expressed by different strains. For instance, while the myceliated phenotype of the strain from patient FB2 exhibited a very low level of proteinase activity (Fig. 5B), the myceliated phenotype of the strain from patient I4 exhibited a relatively high level of proteinase activity (Fig. 5C).

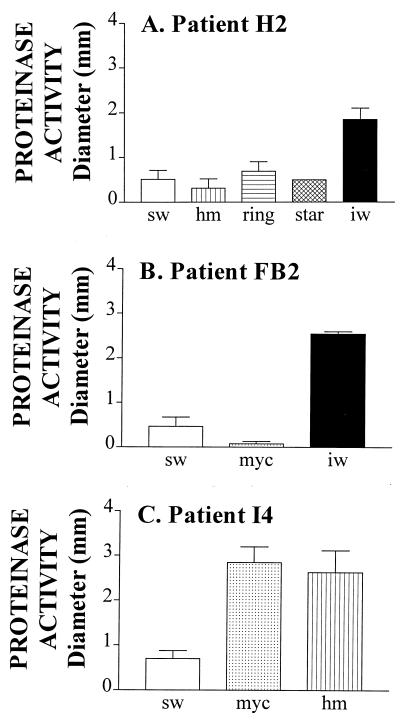

FIG. 5.

Proteinase activities of the different switch phenotypes in the switching repertoires of isolates from patients H2, FB2, and I4. sw, smooth white; hm, heavily myceliated; iw, irregular wrinkle; myc, myceliated. Error bars represent standard deviations. The numbers of isolates with sw, hm, ring, star, and iw phenotypes analyzed for patient H2 were 19, 17, 15, 10, and 12, respectively; those with sw, myc, and iw phenotypes for patient FB2 were 23, 23, and 20, respectively; and those with sw, myc, and hm phenotypes for patient I4 were 16, 18, and 21, respectively.

Drug susceptibility varies as a function of colony morphology.

Isolates from the 11 HIV-positive individuals were tested for susceptibility to the common antifungal drugs nystatin, 5FC, amphotericin B, fluconazole, clotrimazole, and voriconazole. The combined results for all isolates from the 11 HIV-positive individuals before, during, and after the first episode of oral thrush were a bit surprising (Fig. 6). There was no indication of an increase in drug resistance after the first episode of thrush and antifungal drug therapy (Fig. 6C). In fact, there appeared to be a decrease in susceptibility to voriconazole and fluconazole and no obvious trend in susceptibility to 5FC (which went up and then down), to clotrimazole (which went down and then up), to amphotericin B (which stayed the same), or to nystatin (which went up after the first episode) (Fig. 6).

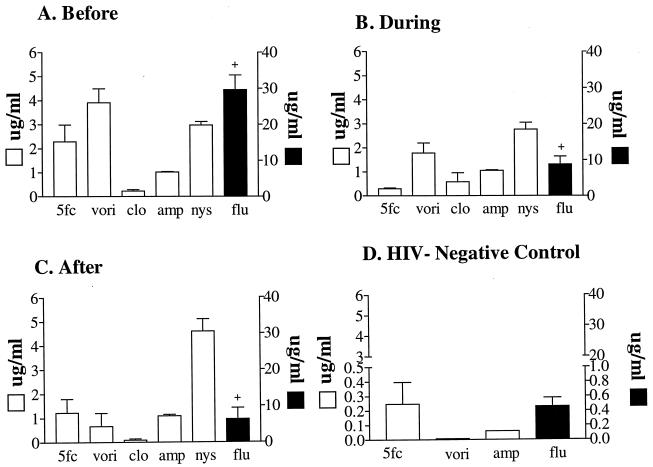

FIG. 6.

(A to C) Susceptibilities (MICs) of isolates collected before (A), during (B), and after (C) the first episode of oral thrush to a variety of antifungal agents. (D) Susceptibility of isolates from HIV-negative control individuals. The numbers of isolates analyzed before, during, and after the first episode of thrush and the numbers analyzed from controls were 169, 184, 175, and 40, respectively. 5fc, 5FC; vori, voriconazole; clo, clotrimazole; amp, amphotericin B; nys, nystatin; flu, fluconazole. Error bars represent standard deviations.

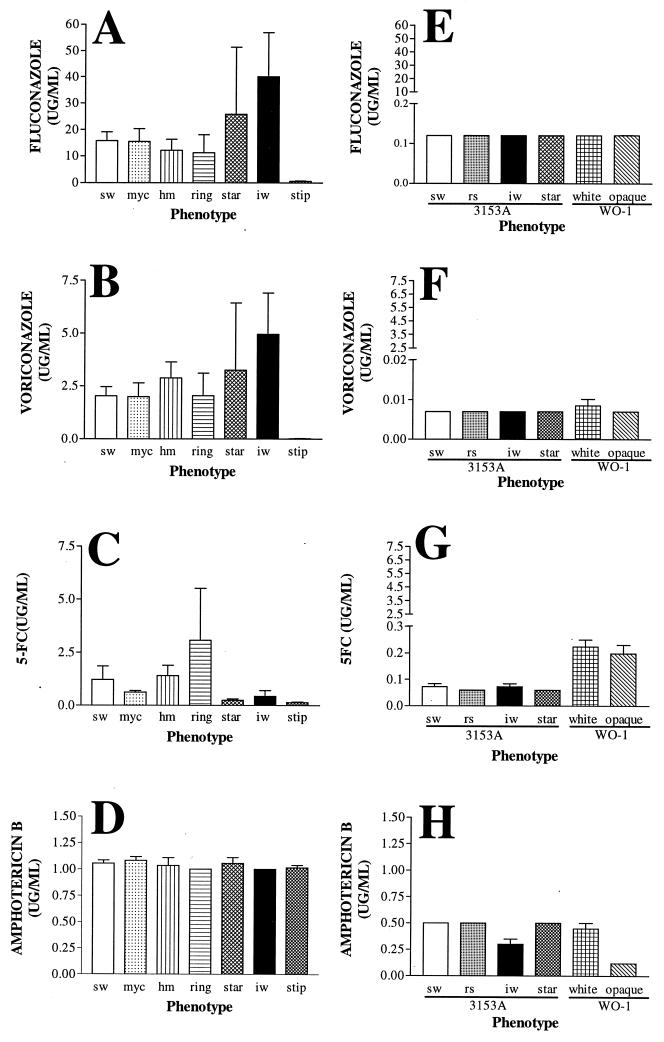

Although average levels of susceptibility indicated that no consistent changes were associated with an episode or treatment of the first episode of oral or esophageal thrush, there was a dramatic difference between all of the isolates from HIV-positive patients and all of the isolates from control individuals. The average susceptibility of 10 tested control isolates to 5FC, voriconazole, amphotericin B, and fluconazole (Fig. 6D) was approximately 1 order of magnitude lower than that of HIV isolates (Fig. 6A, B, and C). In addition, pronounced differences in average susceptibility existed among switch phenotypes. For instance, while stipple was highly susceptible to fluconazole (Fig. 7A) and voriconazole (Fig. 7B), irregular wrinkle was far less susceptible to both (Fig. 7A and B). While the susceptibilities of the different phenotypes to the two azoles were consistent, susceptibility to 5FC was quite different (Fig. 7C). On the other hand, there was no significant difference among phenotypes in susceptibility to amphotericin B (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

Sensitivities of the different switch phenotypes from the present study (A through D) and from laboratory strains 3153A and WO-1 (E through H) to fluconazole, voriconazole, 5FC, and amphotericin B. sw, smooth white; myc, myceliated; hm, heavily myceliated; iw, irregular wrinkle; stip, stippled; rs, revertant smooth. The numbers of sw, myc, hm, ring, star, iw, and stip isolates from HIV-positive individuals were 140, 90, 85, 40, 45, 60, and 68, respectively. Error bars represent standard deviations.

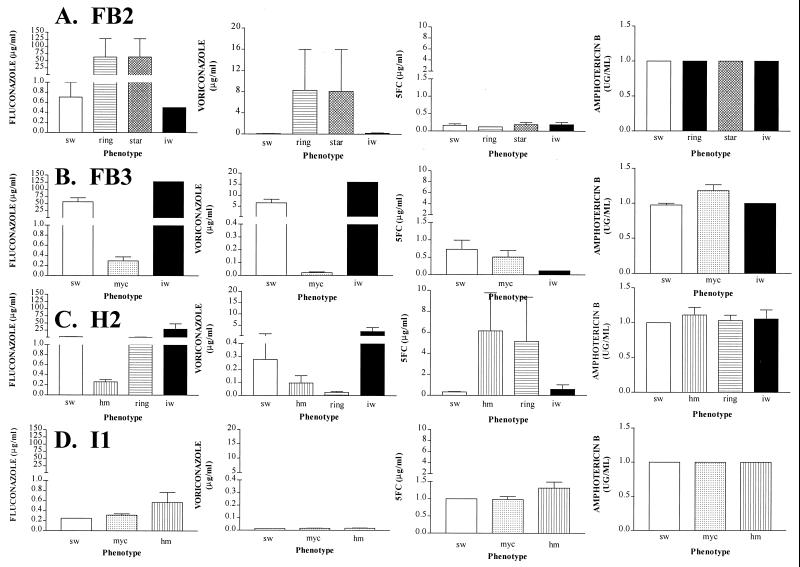

Dramatic differences in susceptibility were observed among the switch phenotypes of individual colonizing strains for fluconazole, voriconazole, and 5FC but, again, no differences were observed for amphotericin B (Fig. 8). For instance, the smooth white and irregular wrinkle phenotypes of the strain colonizing patient FB2 were highly susceptible to fluconazole and voriconazole, while star and ring were far less susceptible (Fig. 8A). In contrast, all phenotypes were equally susceptible to 5FC and amphotericin B (Fig. 8A). While the irregular wrinkle phenotype of the strain colonizing patient H2 was far less susceptible to fluconazole and voriconazole than smooth white, heavily myceliated, and ring, heavily myceliated and ring were far less susceptible to 5FC than irregular wrinkle and smooth white (Fig. 8C). In some cases (e.g., the switch phenotypes of the strain colonizing patient I1), there were no significant differences between variant phenotypes and smooth white in susceptibility to any of the tested drugs (Fig. 8D).

FIG. 8.

Sensitivities of the different switch phenotypes in the switching repertoires of isolates from patients FB2 (A), FB3 (B), H2 (C), and I1 (D) to fluconazole, voriconazole, 5FC, and amphotericin B. The numbers of sw, ring, star, and iw isolates analyzed for FB2 were 15, 10, 11, and 12, respectively; for FB3, the numbers of sw, myc, and iw isolates were 30, 35, and 25, respectively; for H2, ring, and iw isolates were 25, 21, 20, and 11, respectively; and for I1, the numbers of sw, myc, and hm isolates were 20, 28, and 30, respectively. Abbreviations for switch phenotypes are defined in the legend to Fig. 7.

In contrast to the switch phenotypes of strains recently isolated from HIV-positive patients, the switch phenotypes of each of the established laboratory strains (3153A and WO-1) of C. albicans exhibited little difference in susceptibility to fluconazole, voriconazole, and 5FC (Fig. 8E, F, and G, respectively). The switch phenotypes of strain 3153A also exhibited little difference in susceptibility to amphotericin B (Fig. 8H). However, opaque-phase cells of strain WO-1 were more susceptible to amphotericin B then were white-phase cells (Fig. 7H), as demonstrated in a previous study (57).

DISCUSSION

Virtually all tested strains of C. albicans and related species (52, 60; D. R. Soll, unpublished observations), as well as other infectious fungi, such as Cryptococcus neoformans (12, 15), can undergo high-frequency phenotypic switching. Although switching was first identified through its effects on colony morphology, it was soon demonstrated that the spontaneous and reversible process had profound effects on a number of cellular characteristics, including several putative virulence traits. With the white-opaque transition as a model, it was further demonstrated that switching could affect virulence in animal models. While white-phase cells were highly virulent in a mouse tail injection model for systemic infection, they were only weakly virulent in a mouse skin model for cutaneous infection (21, 22). In contrast, opaque-phase cells, representing the alternate switch phenotype, were weakly virulent in the systemic model but highly virulent in the cutaneous model. These results have provided the most direct evidence that variants generated by spontaneous high-frequency switching provide a population of infecting cells with a variety of phenotypic states for rapid adaptation to changes in host physiology and anatomical location and for quick responses to challenges from the immune system and antifungal drug therapy. Subsequent studies have demonstrated that switching regulates a variety of phase-specific genes, several of which encode putative virulence factors, and that specific molecular circuitry has evolved for the regulation of phase-specific gene expression in the switching process (reviewed in references 53, 54, and 56).

Here, we have examined whether isolates from HIV-positive individuals switch at higher frequencies, on average, than isolates from uninfected individuals and whether switching in fresh isolates affects the secretion of acid proteinase and susceptibility to several antifungal agents. Our results demonstrate (i) that primary cultures of C. albicans from the oral cavities of HIV-positive individuals contain proportions of variant colony morphologies 320 times higher, on average, than those in primary cultures of isolates from the oral cavities of control individuals; (ii) that the majority of these variants result from switching; (iii) that strains from HIV-positive individuals continue to switch at frequencies much higher than those of strains colonizing control individuals; (iv) that switching in strains derived from HIV-positive patients has a profound effect on both proteinase secretion and drug susceptibility; and (v) that strains infecting HIV-positive individuals, even before their first episode of oral thrush and associated drug therapy, are, on average, far more resistant to antifungal drugs than strains from healthy control individuals.

Increased frequency of switching.

The colony morphologies of primary cultures of commensal isolates from 12 healthy individuals were uniformly smooth white, and the proportion of variants in secondary platings of random clonal isolates from these primary cultures remained low. In marked contrast, the proportion of variant colony morphologies in primary cultures of isolates from HIV-positive individuals prior to the first episode of thrush was, on average, 1.6 × 10−1, and the average proportion of variants in secondary platings was 8.6 × 10−2. The fact that clonal isolates from primary cultures of HIV-positive patients still generated variant colony morphologies in secondary platings at a frequency between 1 and 2 orders of magnitude higher than that of isolates from healthy control individuals suggests that the former switch at significantly higher rates.

Our results demonstrate that the C. albicans strains colonizing the oral cavity of HIV-positive individuals prior to the first episode of thrush usually persist through subsequent episodes, as have others (5, 11, 47), and that the high rates of switching persist. The observation that isolates obtained from HIV-positive individuals prior to thrush are, on average, already in a high-frequency mode of switching suggests that changes in the oral cavity of HIV-positive individuals prior to thrush either induce an increase in the switching frequency of commensal strains or select new strains with increased switching frequencies. Other differences in isolates obtained from HIV-positive patients have been documented, including increased adherence to epithelial cells (35, 66) and increased expression of secreted aspartyl proteinases (10, 34).

Effects of switching on proteinase secretion.

Although the average levels of proteinase secretion by isolates from HIV-positive individuals before, during, and after the first episode of thrush were not significantly different from those of control isolates, in contrast to previous studies (10, 34), the effects of switching on proteinase secretion were dramatic. This was not a surprising result, since it has been demonstrated that switching of laboratory strains regulates the transcription of the secreted aspartyl proteinase genes SAP1 and SAP3 (17, 29, 32, 68) and that the regulation of SAP1 expression by switching affects virulence in a mouse model of cutaneous infection (21). The high frequency of switching in C. albicans populations colonizing HIV-positive individuals results in variant phenotypes secreting very different levels of aspartyl proteinase and, presumably, exhibiting very different combinations of virulence traits (52, 53, 54, 56). The high level of spontaneous variability in these populations would provide them with the advantage of rapid adaptation.

Increased levels of drug resistance.

In addition to increased rates of switching, strains colonizing HIV-positive individuals also exhibit, on average, elevated levels of resistance to a variety of antifungal drugs, including 5FC, voriconazole, fluconazole, and amphotericin B. Surprisingly, the strains colonizing HIV-positive individuals exhibited elevated resistance prior to drug therapy, just as they did elevated frequencies of switching. Again, these results suggest either that the original commensals in these individuals were induced to be more drug resistant or that more drug-resistant strains replaced the original commensals as a result of changes in the oral cavity associated with HIV infection. In either case, the inducing or selecting condition was not drug treatment, which has been documented to induce drug-resistant strains in HIV-positive individuals (6, 8, 9, 13, 23, 24, 39, 42) through a variety of molecular mechanisms (29, 45).

We have presented evidence here that switching can have a profound effect on the susceptibility of a strain to a variety of antifungal agents. The increased frequency of switching in strains from HIV-positive individuals increases the proportion of phenotypes in a colonizing population that are drug resistant. This finding should not be surprising, since it has been demonstrated that switching regulates the transcription of selected genes involved in drug resistance (4; D. Sanglard, personal communication).

Surprisingly, the switching systems of fresh C. albicans isolates from HIV-positive individuals had a far greater impact on drug resistance than on the two established strains (3153A and WO-1) that are commonly used to study switching under laboratory conditions. The levels of resistance achieved by switch phenotypes in strains freshly isolated from HIV-positive individuals were in some instances 1 order of magnitude higher. It is not clear whether maintenance under laboratory conditions diminished drug resistance in strains 3153A and WO-1 or whether the strains were never resistant. If the latter were true, then the isolates from HIV-positive individuals might have been unique in their elevated levels of drug resistance. In either case, these results suggest that in future studies in which the role of switching in drug resistance is investigated, the switching systems of fresh pathogenic isolates, not those of established laboratory strains, should be used.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by Public Health Service grants AI39735 and DE10758 to D.R.S. and DE00364 to K.V. from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson J, Mihalik R, Soll D R. Ultrastructure and antigenicity of the unique cell wall “pimple” of the Candida opaque phenotype. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:224–235. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.224-235.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson J, Srikantha T, Morrow B, Miyasaki S H, White T C, Agabian N, Schmid J, Soll D R. Characterization and partial sequence of the fingerprinting probe Ca3 of Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1472–1480. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1472-1480.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson J M, Soll D R. The unique phenotype of opaque cells in the “white-opaque transition” in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:5579–5588. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5579-5588.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balan I, Alarco A, Raymond M. The Candida albicans CDR3 gene codes for an opaque-phase ABC transporter. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7210–7218. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7210-7218.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barchiesi F, Arzeni D, Del Prete M S, Sinicco A, Falconi di Francesco L, Pasticci M B, Lamura L, Nuzzo M M, Burzacchini F, Coppola S, Chiodo F, Scalise G. Fluconazole susceptibility and strain variation of Candida albicans isolates from HIV-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41:541–548. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barchiesi F, Najvar K, Luther M, Scalise G, Rinaldi G, Graybill R. Variation in fluconazole efficacy for Candida albicans strains sequentially isolated from oral cavities of patients with AIDS in an experimental murine candidiasis model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1317–1320. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedell G, Soll D R. The effects of low concentrations of zinc on the growth and dimorphism of Candida albicans: evidence for zinc-resistant and zinc-sensitive pathways for mycelium formation. Infect Immun. 1979;26:348–354. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.1.348-354.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berenguer J, Diaz-Guerra T, Ruiz-Diez L, Bernaldo de Quiros J, Rodriguez-Tudela T, Martinez-Suarez J. Genetic dissimilarity of two fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains causing meningitis and oral candidiasis in the same AIDS patient. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1542–1545. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1542-1545.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartledge J D, Midgley J, Gazzard B G. Clinically significant azole cross-resistance in Candida isolates from HIV-positive patients with oral candidosis. AIDS. 1997;11:1839–1844. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199715000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bernardis F, Chiani P, Ciccozzi M, Pellegrini G, Ceddia T, D'Offizzi G, Quinti I, Sullivan P A, Cassone A. Elevated aspartic proteinase secretion and experimental pathogenicity of Candida albicans isolates from oral cavities of subjects infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:466–471. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.466-471.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz-Guerra T M, Martinez-Suarez J, Laguna F, Valencia E, Rodriguez-Tudela J. Change in fluconazole susceptibility patterns and genetic relationship among oral Candida albicans isolates. AIDS. 1998;12:1601–1610. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fries B C, Goldman D C, Cherniak R, Ju R, Casadevall A. Phenotypic switching in Cryptococcus neoformans results in changes in cellular morphology and glucuronoxylomannan structure. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6076–6083. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6076-6083.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallagher J, Bennett D, Henman M, Russell R, Flint S, Shanley D, Coleman D. Reduced azole susceptibility of oral isolates of Candida albicans from HIV-positive patients and a derivative exhibiting colony morphology variation. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1901–1911. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-9-1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil C, Pomes R, Nombela C. A complementation analysis by parasexual recombination of Candida albicans morphological mutants. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1587–1595. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-6-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman D, Fries B, Franzot S, Montella L, Casadevall A. Phenotypic switching in the human pathogenic fungus Cryptococcus neoformans is associated with changes in virulence and pulmonary inflammatory response in rodents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14967–14972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellstein J, Vawter-Hugart H, Fotos P, Schmid J, Soll D R. Genetic similarity and phenotypic diversity of commensal and pathogenic strains of Candida albicans isolated from the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3190–3199. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3190-3199.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hube B, Monod M, Schofield D, Brown A, Gow N. Expression of seven members of the gene family encoding aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones S, White G, Hunter P R. Increased phenotypic switching in strains of Candida albicans associated with invasive infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2869–2870. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2869-2870.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy M J, Rogers A L, Hanselman L A, Soll D R, Yancey R J. Variation in adhesion and cell surface hydrophobicity in Candida albicans white and opaque phenotypes. Mycopathologia. 1988;102:149–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00437397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolotila M P, Diamond R D. Effects of neutrophils and in vitro oxidants on survival and phenotypic switching of Candida albicans WO-1. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1174–1179. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.5.1174-1179.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kvaal C, Srikantha T, Daniels K, McCoy J, Soll D R. Misexpression of the opaque phase-specific gene PEPI (SAPI) in the white phase of Candida albicans enhances growth in serum and virulence in a cutaneous model. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6652–6662. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6652-6662.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvaal C A, Srikantha T, Soll D R. Misexpression of the white phase-specific gene WH11 in the opaque phase of Candida albicans affects switching and virulence. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4468–4475. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4468-4475.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law D, Moore C B, Wardle H M, Ganguli L A, Keaney G L, Denning D W. High prevalence of antifungal resistance in Candida spp. from patients with AIDS. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:659–668. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Guennec R, Reynes J, Mallie M, Pujol C, Janbon F, Bastide J-M. Fluconazole- and itraconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains from AIDS patients: multilocus enzyme electrophoresis analysis and antifungal susceptibilities. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2732–2737. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2732-2737.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lockhart S, Fritch J J, Meier A S, Schröppel K, Srikantha T, Galask R, Soll D R. Colonizing populations of Candida albicans are clonal in origin but undergo microevolution through C1 fragment reorganization as demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting and C1 sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1501–1509. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1501-1509.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lockhart S R, Joly S, Pujol C, Sobel J, Pfaller M, Soll D R. Development and verification of fingerprinting probes for Candida glabrata. Microbiology. 1997;143:3733–3746. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lockhart S R, Joly S, Vargas K, Swails-Wenger J, Enger L, Soll D R. Defenses against oral Candida carriage break down in the elderly. J Dent Res. 1999;78:857–868. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marco F, Lockhart S, Pfaller M, Pujol C, Rangel-Frausto M S, Wiblin T, Blumberg H M, Edwards J E, Jarvis W, Saiman L, Patterson J E, Rinaldi M G, Wenzel R P, Soll D R the NEMIS Study Group. Elucidating the origins of nosocomial infections with Candida albicans by DNA fingerprinting with the complex probe Ca3. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2817–2828. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.2817-2828.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran G, Sanglard D, Donnelly S, Shanley D, Sullivan D, Coleman C. Identification and expression of multidrug transporters responsible for fluconazole resistance in Candida dubliniensis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1819–1830. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrow B, Ramey H, Soll D R. Regulation of phase-specific genes in the more general switching system of Candida albicans strain 3153A. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:287–394. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrow B, Srikantha T, Anderson J, Soll D R. Coordinate regulation of two opaque-specific genes during white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1823–1828. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1823-1828.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrow B, Srikantha T, Soll D R. Transcription of the gene for a pepsinogen, PEP1, is regulated by white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2997–3005. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.7.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odds F C, Bernaerts R. CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1923–1929. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1923-1929.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ollert M W, Wende C, Goerlich M, McMullan-Vogel C G, Borg-Von Zepelin M, Vogel C-W, Korting H C. Increased expression of Candida albicans secretory proteinase, a putative virulence factor, in isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2543–2549. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2543-2549.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pereiro M, Losada A, Toribio J. Adherence of Candida albicans strains isolated from AIDS patients. Comparison with pathogenic yeasts isolated from patients without HIV infection. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfaller M. Nosocomial candidiasis: emerging species, reservoirs, and modes of transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:S89–S94. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.supplement_2.s89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfaller M A, Bale M, Buschelman B, Lancaster M, Espinel-Ingroff A, Rex J H, Rinaldi M C, Cooper C R, McGinnis M R. Quality control guidelines for National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1104–1107. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1104-1107.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfaller M A, Messer S A, Coffman S. Comparison of visual and spectrophotometric methods of MIC endpoint determination by using broth microdilution methods to test five antifungal agents, including the new triazole DO870. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1094–1097. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.5.1094-1097.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfaller M A, Rhine-Chalberg J, Reding S W, Smith J, Farinacci G, Fothergill A W, Rinaldi M G. Variations in fluconazole susceptibility and electrophoretic karyotype among oral isolates of Candida albicans from patients with AIDS and oral candidiasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:59–64. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.59-64.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pujol C, Joly S, Lockhart S, Noel S, Tibayrenc M, Soll D R. Parity of MLEE, RAPD, and Ca3 hybridization as fingerprinting methods for Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2348–2358. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2348-2358.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pujol C, Joly S, Nolan B, Srikantha T, Soll D R. Microevolutionary changes in Candida albicans identified by the complex Ca3 fingerprinting probe involve insertions and deletions of the full-length repetitive sequence RPS at specific genomic sites. Microbiology. 1999;145:2635–2646. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-10-2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Redding S, Smith J, Farinacci G, Rinaldi M, Fothergill A, Rhine-Chalberg J, Pfaller M. Resistance of Candida albicans to fluconazole during treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in a patient with AIDS: documentation by in vitro susceptibility testing and DNA subtype analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:240–242. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rex J H, Pfaller M A, Lancaster M, Odds F C, Bolmstrom A, Rinaldi M G. Quality control guidelines for National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:816–817. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.816-817.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadhu C, McEachern M J, Rustchenko-Bulgac E P, Schmid J, Soll D R, Hicks J. Telomeric and dispersed repeat sequences in Candida yeasts and their use in strain identification. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:842–850. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.842-850.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Koymans L, Bille J. Amino acid substitutions in the cytochrome P-450 ianosterol 14α-demethylase 9CYP51A1 from azole-resistant Candida albicans clinical isolates contribute to resistance to azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:241–253. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scherer S, Stevens D A. Application of DNA typing methods to epidemiology and taxonomy of Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:675–679. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.4.675-679.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schmid J, Odds F C, Wiselka M J, Nicholson K G, Soll D R. Genetic similarity and maintenance of Candida albicans strains in a group of AIDS patients demonstrated by DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:935–941. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.935-941.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmid J, Voss E, Soll D R. Computer-assisted methods for assessing Candida albicans strain relatedness by Southern blot hybridization with repetitive sequence Ca3. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1236–1243. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1236-1243.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Slutsky B, Buffo J, Soll D R. High frequency “switching” of colony morphology in Candida albicans. Science. 1985;230:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.3901258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slutsky B, Staebell M, Anderson J, Risen L, Pfaller M, Soll D R. “White-opaque transition”: a second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:189–197. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.189-197.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sneath P H A, Sokal R R. Numerical taxonomy. W. H. San Francisco, Calif: Freeman & Co.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Soll D R. High-frequency switching in Candida albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:183–203. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soll D R. The emerging molecular biology of switching in Candida albicans. ASM News. 1997;62:415–420. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soll D R. Gene regulation during high frequency switching in Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1997;143:279–288. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soll D R. The “ins and outs” of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:332–370. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.332-370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soll D R. The molecular biology of switching in Candida. In: Cihlac R L, Calderone R A, editors. Fungal pathogenesis: principles and clinical applications, in press. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soll D R, Anderson J, Bergen M. The developmental biology of the white-opaque transition in Candida albicans. In: Prasad R, editor. Candida albicans: cellular and molecular biology. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 20–45. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soll D R, Galask R, Isley S, Rao T V G, Stone D, Hicks J, Schmid J, Mac K, Hanna C. “Switching” of Candida albicans during successive episodes of recurrent vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:681–690. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.681-690.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soll D R, Langtimm C J, McDowell J, Hicks J, Galask R. High-frequency switching in Candida strains isolated from vaginitis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1611–1622. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1611-1622.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Soll D R, Staebell M, Langtimm C J, Pfaller M, Hicks J, Rao T V G. Multiple Candida strains in the course of a single systemic infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1448–1459. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.8.1448-1459.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sonneborn A, Tebarth B, Ernst J F. Control of white-opaque phenotypic switching in Candida albicans by the Efg1 morphogenetic regulator. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4655–4660. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4655-4660.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Srikantha T, Soll D R. A white-specific gene in the white-opaque switching system of Candida albicans. Gene. 1993;131:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90668-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Srikantha T, Tsai L, Daniels K, Enger L, Highley K, Soll D R. The two-component hybrid kinase regulator CaNIK1 of Candida albicans. Microbiology. 1998;144:2715–2729. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srikantha T, Tsai L, Daniels K, Soll D R. EFGI null mutant of Candida albicans can switch but cannot suppress the complete phenotype of white budding cells. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1580–1591. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1580-1591.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Staib F. Serum proteins as nitrogen source for yeast-like fungi. Sabouraudia. 1965;4:187–193. doi: 10.1080/00362176685190421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sweet S P, Cookson S, Challacombe S J. Candida albicans isolates from HIV-infected and AIDS patients exhibit enhanced adherence to epithelial cells. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:452–457. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-6-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vargas K, Wertz P W, Drake D, Morrow B, Soll D R. Differences in adhesion of Candida albicans 3153A cells exhibiting switch phenotypes of buccal epithelium and stratum corneum. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1328–1335. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1328-1335.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White R, Miyasaki S, Agabian N. Three distinct secreted aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6126–6133. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6126-6133.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]