Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate whether the debonding procedure leads to restitutio ad integrum of the enamel surface by investigating the presence of enamel within the bracket base remnants after debonding.

Materials and Methods:

Sixty patients who completed orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances were included. A total of 1068 brackets were microphotographed; the brackets presenting some remnants on the base (n = 818) were selected and analyzed with ImageJ software to measure the remnant area. From this population a statistically significant sample (n = 100) was observed under a scanning electron microscope to check for the presence of enamel within the remnants. Energy dispersive x-ray spectrometry was also performed to obtain quantitative data.

Results:

Statistically significant differences in the remnant percentage between arches were observed for incisor and canine brackets (P < .0001 and P = .022, respectively). From a morphologic analysis of the scanning electron micrographs the bracket bases were categorized in 3 groups: group A, bases presenting a thin enamel coat (83%); group B, bases showing sizable enamel fragments (7%); group C, bases with no morphologic evidence of enamel presence (10%). Calcium presence was noted on all evaluated brackets under energy dispersive x-ray spectrometry. No significant difference was observed in the Ca/Si ratio between group A (16.21%) and group B (18.77%), whereas the Ca/Si ratio in group C (5.40%) was significantly lower than that of the other groups (P < .323 and P = .0001, respectively).

Conclusion:

The objective of an atraumatic debonding is not achieved yet; in some cases the damage could be clinically relevant.

INTRODUCTION

The main objective of orthodontic debonding is to remove brackets and adhesive resin while restoring the enamel surface to its pretreatment condition.1–3 Nevertheless, damage to the enamel due to debonding has been, and still is, a concern to clinicians because it is reported to occur in vitro4–6 and in vivo.7,8

During bracket removal, bond failure can occur at the adhesive-enamel or at the adhesive-bracket interface (adhesive failure), or within the adhesive (cohesive failure); generally, a combination of adhesive and cohesive failure (mixed failure) takes place.9 A greater risk of damage to the tooth surface occurs in cases of adhesive failure between resin and enamel.9–11 This happens especially with the use of ceramic brackets,12–14 but enamel fracture may also occur with metal brackets.6,7

There are several important differences between in vitro and in vivo studies dealing with modes of bracket failure. The in vivo debonding load is a combination of shear, tensile, and torsion force,15,16 whereas in vitro studies are conducted by means of single tests (shear, tensile, or torsion). Furthermore, the complex oral environment involves continually changing temperature, stresses, humidity, acidity, and variability in the amount and composition of plaque. These conditions cannot be reproduced in the laboratory17,18; therefore, in vitro studies could not be highly relevant from the standpoint of scientific and clinical evidence.

On the basis that the debonding procedure should ideally lead to restitutio ad integrum of the enamel surface, the present ex vivo study was conducted to evaluate whether this assumption is true by investigating the presence of enamel within the bracket base remnants after debonding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sixty consecutive patients (39 females and 21 males; mean age, 13 ± 2 years) who completed orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances (mean duration, 1.7 ± 0.5 years) at the Department of Orthodontics, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy, were enrolled in the study. The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. The criteria for patient selection included intact permanent dentition and lack of any decalcification on teeth. All the patients underwent orthodontic treatment in both arches using metal brackets (MBT, Victory Series, 3M Unitek, Monrovia, Calif). The labial enamel surfaces of the teeth were cleaned and polished with a slow-speed handpiece using a slurry made of nonfluoride pumice and water. They were then rinsed and dried with a moisture-free air spray. Subsequently, the enamel was etched with 35% orthophosphoric acid gel (Scotchbond, 3M Unitek) for 30 seconds, rinsed with water, air sprayed for 30 seconds, and then dried until the etched enamel surfaces exhibited a frosty-white appearance.19,20

The brackets were bonded to the teeth surface using an adhesive system (Transbond XT Light Cure adhesive primer and Transbond XT adhesive resin, 3M Unitek), applied in strict accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The brackets were placed on the tooth surface, adjusted to their final position, and pressed firmly in place. The excess resin was then removed from the periphery of the bracket base using a dental probe. Light curing was performed for 20 seconds (10 seconds on the mesial side and 10 seconds on the distal side) using a light-emitting diode unit light (Ortholux, 3M Unitek). At the end of orthodontic treatment, a total of 1168 brackets were removed using the wings method,21 which involves gently squeezing the mesial and distal wings with bracket-removal pliers (Ormco Corporation, Glendora, Calif). Because debonding is an operator-dependent procedure, the results may vary between operators; to avoid this limitation, all clinical procedures were carried out by only one operator.

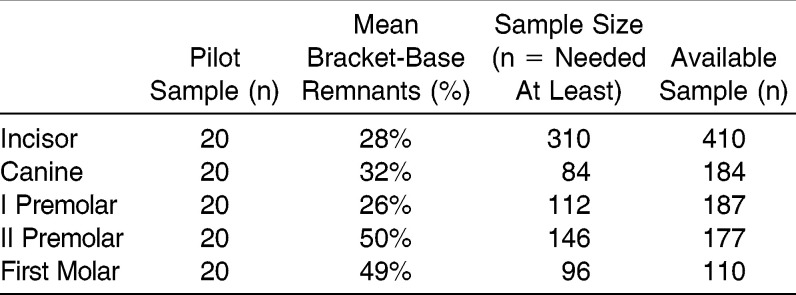

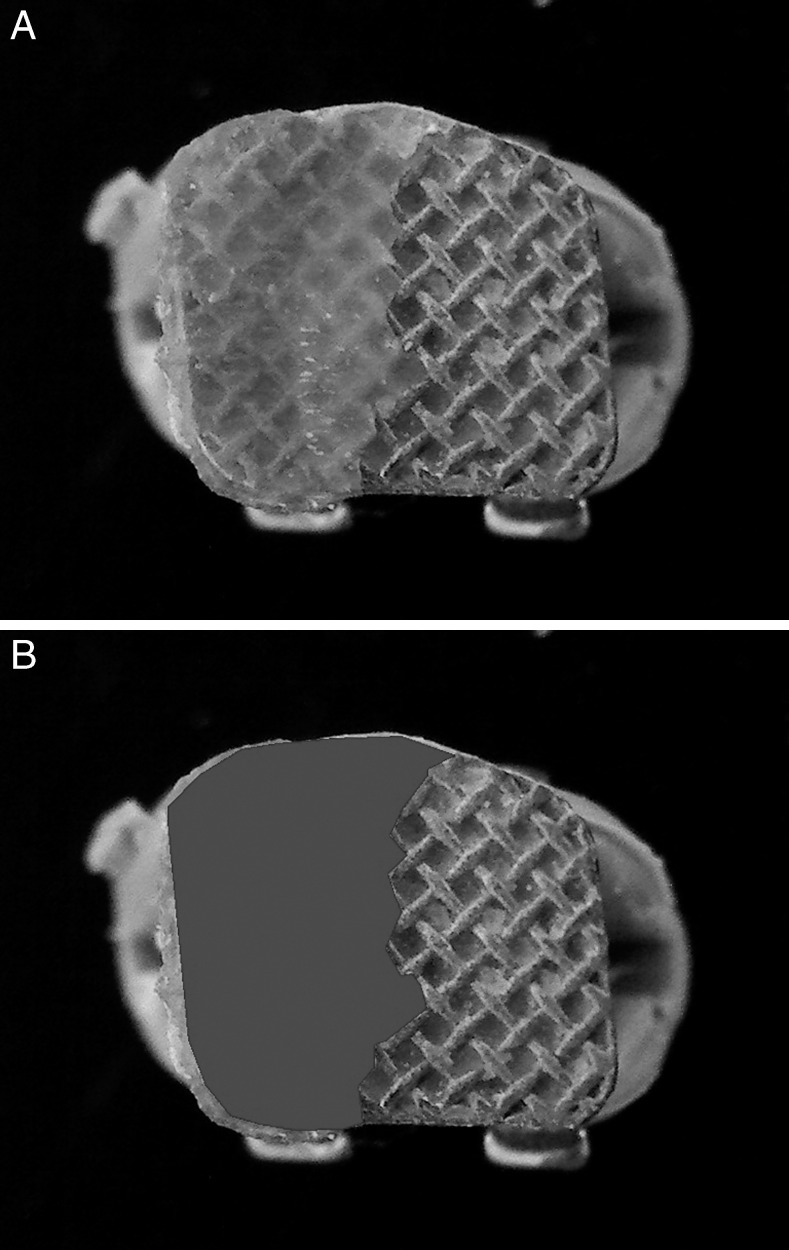

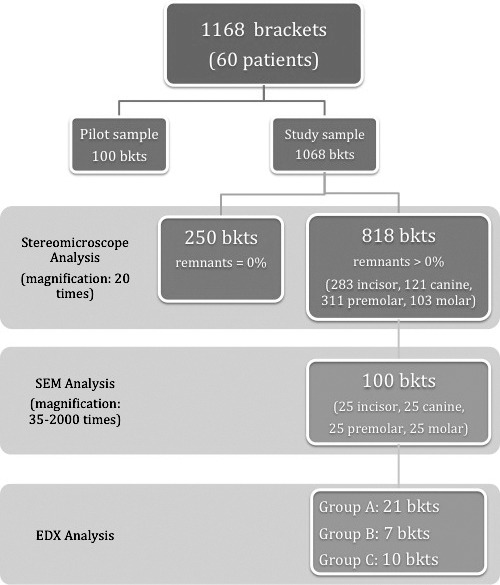

A pilot study was conducted on 100 teeth to determine the sample size, as reported in Table 1. Patient and tooth selection were performed with pseudo-random numbers in blocks of four digits: the first two digits individuate the patient and the last ones individuate the tooth (incisor, canine, premolar, first molar). A single expert examiner trained in micromorphologic evaluations measured the bracket base surface and the remnant surface using ImageJ open-source image-analysis software (Version 1.44o for Macintosh, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md) and calculated the latter area as a percentage of the former. The outcome resulting from the pilot study was the remnant percentage. As no significant differences were found between the upper and lower arches, the two arches were unified. The mean percentage of remnants for each tooth type was used to compute the final sample size with a permissible error of 5% and a power of 95% (Table 1). Because the pilot study revealed that the sample size was statistically adequate, all 1068 brackets were observed under a digital stereomicroscope (Meade Instruments Europe, GmbH & Co KG, Rhede, Germany) at a 20× magnification. This procedure was carried out to exclude bases free of resin remnants and to select only those with some resin remnants, for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis. Therefore, 818 brackets (283 incisor, 121 canine, 311 premolar, and 103 molar) were included in the study. The same examiner who analyzed the pilot-study sample measured the bracket base surface and the remnant surface using ImageJ open-source image-analysis software and calculated the latter area as a percentage of the former (Figure 1A,B).

Table 1.

Results of the Pilot Study

Figure 1.

Representative example of the bracket-base remnant-area measurement. (A) A bracket base showing some remnants. (B) The remnant area detected with the use of Image J.

From the 818-bracket population, considering an α-level of 0.01 with a power of 95% and an estimated percentage of enamel fractures of 77% (as claimed by Stratmann et al.7) it has been computed that at least 60 specimens are needed as statistically adequate sample size for SEM analysis.

Using the same randomized allocation procedure as in the initial pilot study, 100 brackets (25 brackets for each tooth type) were then selected, mounted on aluminum stubs with their bases facing up, sputter-coated with a 300-Å layer of gold and palladium (Sputter Coater SC7620, Polaron, East Grinstead, UK), and analyzed using a high-vacuum SEM (JSM-5200, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) that captured secondary electron images at 10–15 kV using a 20-mm working distance.

Microphotographs of the bracket base were taken at increasing magnifications (35, 100, 200, 500, 1000, and 2000 times). The 35× magnification allowed examination of the bracket base on the whole; the surface was then progressively inspected in detail at higher magnification to detect any presence of enamel. Evaluations were carried out at the same time by two calibrated examiners. On the basis of SEM analysis, the brackets were categorized according to the presence on the resin remnants of a thin coat of enamel (group A; n = 83), sizable enamel fragments (group B; n = 7), and no morphologic evidence of enamel (group C; n = 10).

Because the SEM analysis provides only qualitative evaluation, the bracket sample was also examined through energy dispersive x-ray spectrometry (EDX) to obtain quantitative data. The EDX analysis (Stereo Scan 360, Cambridge Instrument Ltd, Cambridge, UK; using accelerating voltage, 20kV; type of detector, Si(Li)-liquid N2 cooled; detector dead time 17%; spectra acquisition time, 70 seconds; resolution, 133 eV; magnification, between 20 and 30×; scan mode, area) was performed on 21 brackets from group A, 7 brackets from group B, and 10 brackets from group C. The 7 bracket bases from group B were matched to 21 bracket bases from group A (ratio 1∶3), which represented the clinical controls. The 10 bracket bases from group C were also analyzed. The percentage of calcium was calculated from adhesive in relation to that of silicon. Because the bonding materials used are calcium free, the presence of this element could only be attributed to enamel. The study design is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the study design; bkts indicates brackets.

Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test the normality of the distribution of the primary outcome, that is, remnant percentage, for each tooth in both arches. Because of the significance of the deviation from normality (P = .0001), median and interquartile ranges were presented to describe the data. The Mann-Whitney U-test was applied to compare the percentages of remnants for each tooth type between the arches. The α-level was set at 0.05.

As regards EDX examination, the Shapiro-Wilk test evidenced no significant deviation from normality of the Ca/Si ratio in each of the three groups (A, B, and C). Consequently, the comparison between them was carried out by using a t-test for independent samples, after having controlled the homoschedasticity of the variances by means of the Levene test.

RESULTS

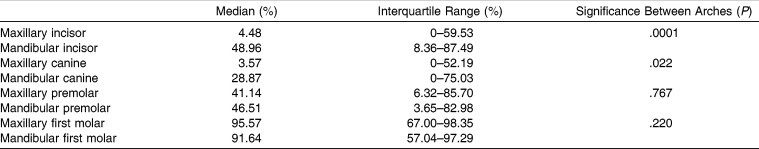

The remnant areas of the 818 bracket bases analyzed with the use of ImageJ are reported in Table 2 and expressed as a percentage of the bracket base surface. The maxillary incisor and maxillary canine brackets exhibited the lowest median values (4.48% and 3.57%, respectively); first molar brackets, either maxillary or mandibular, displayed the highest median values (95.57% and 91.64%, respectively). The Mann-Whitney U-test did not show a statistically significant difference between upper and lower arches for premolar (P = .767) or molar brackets (P = .220), whereas statistically significant differences between arches were observed for incisor (P = .0001) and canine brackets (P = .022).

Table 2.

Percentages of Bracket-base Remnants by Tooth Type

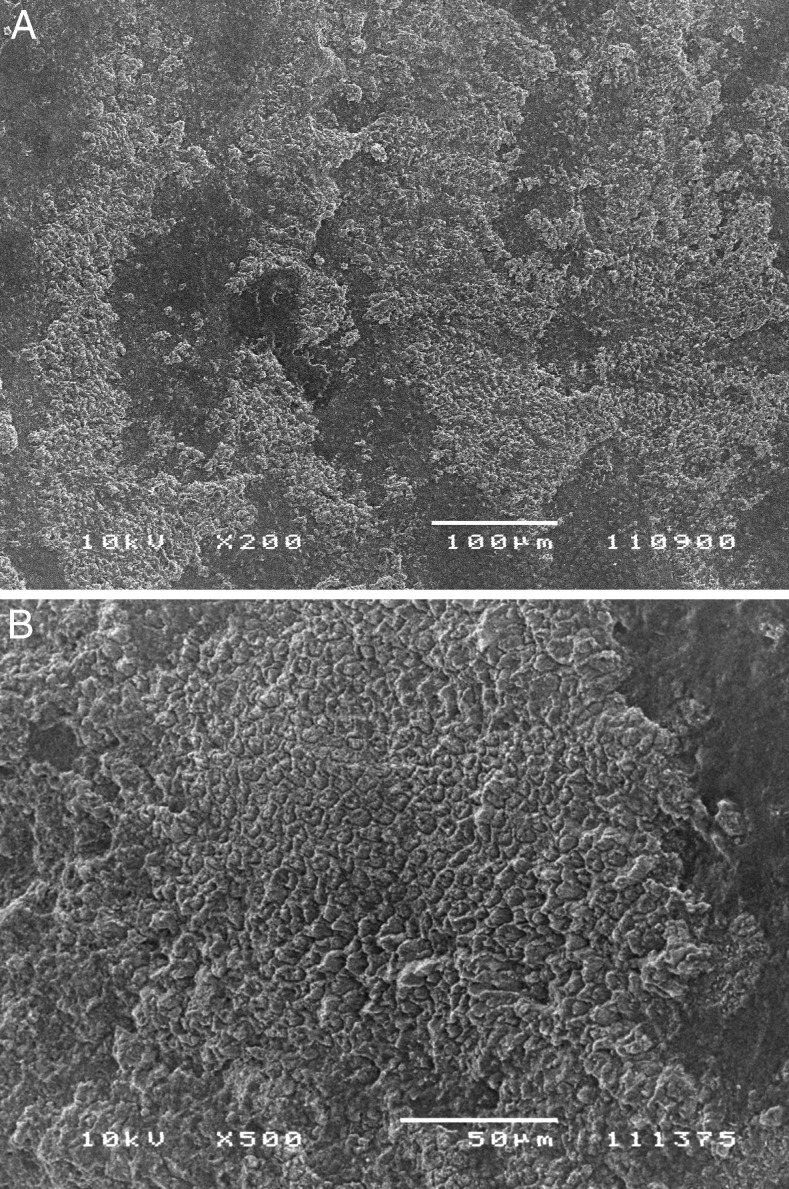

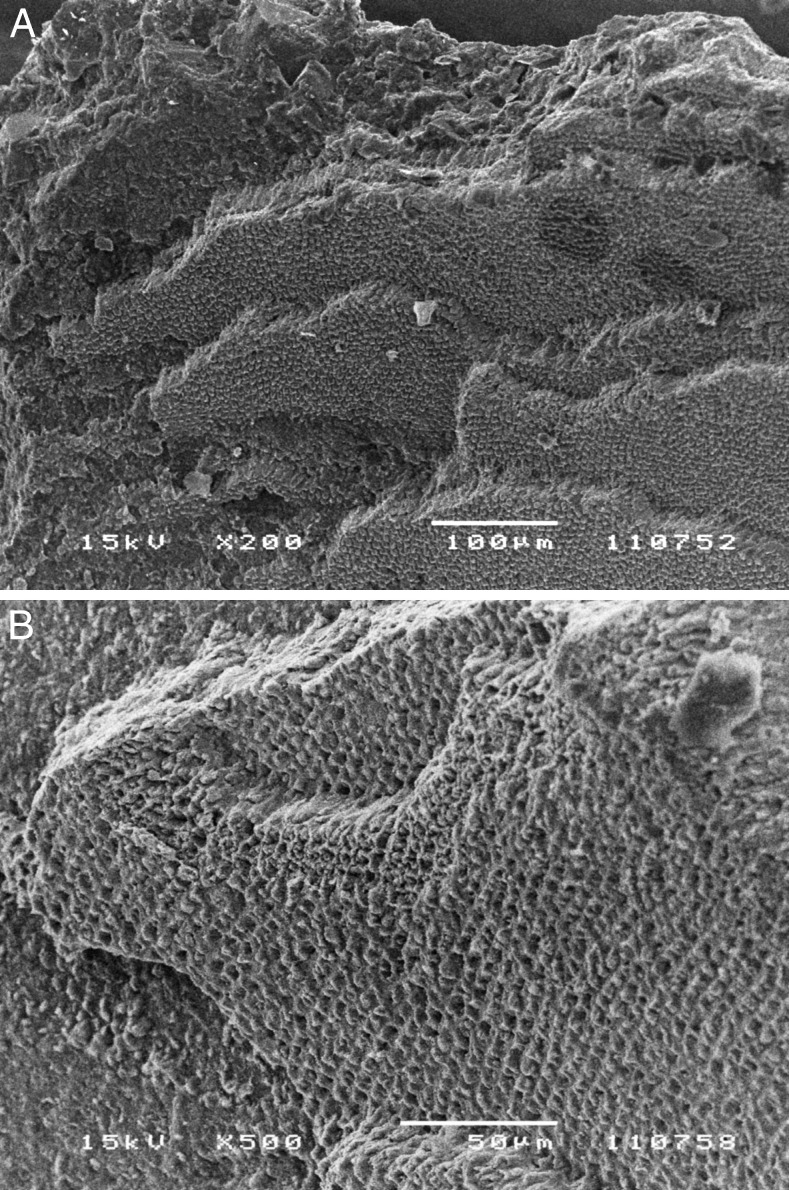

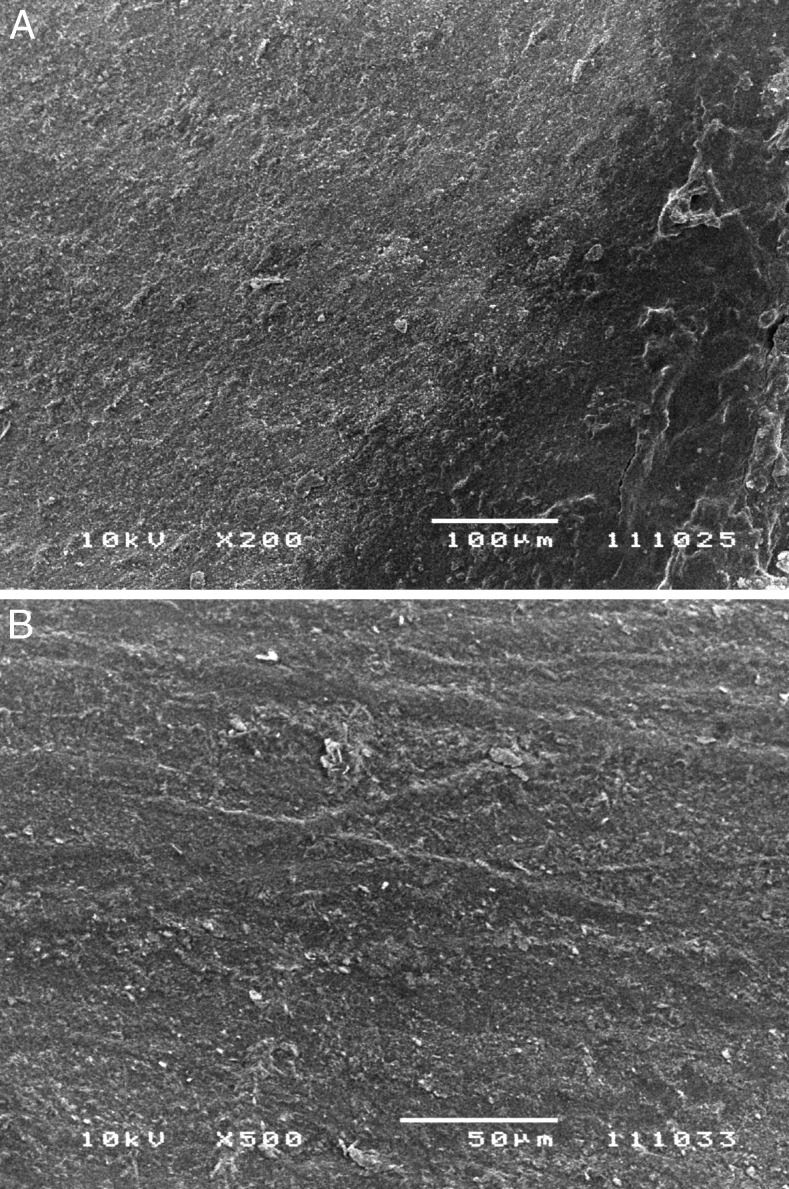

As regards the 100-bracket sample, from a morphologic analysis of the SEM micrographs, two modes of enamel presence emerged: (1) a thin coat of enamel on the resin surface was found in 83 specimens (83%) (group A) (Figure 3A,B); and (2) sizable enamel fragments (area ranging from 306 to 1247 µm2) on the resin were detected in 7 samples (7%) (group B) (Figure 4A,B), located on canine (n = 2), premolar (n = 3), and molar brackets (n = 2). No evidence of enamel was visible on 10 samples (10%) (group C) (Figure 5A,B), whereas EDX analysis showed the presence of calcium on all specimens. The mean Ca/Si ratio was 16.21 ± 5.81% for group A, 18.77 ± 5.79% for group B, and 5.40 ± 2.02% for group C. Based on the statistical analysis (t-test for independent samples), no significant difference was observed in the Ca/Si ratio between group A and group B (P = 0.323); the Ca/Si ratio in group C was significantly lower than that of the other groups (P = 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Representative micrograph of a bracket base showing a thin coat of enamel over the resin surface. (A) 200× magnification. (B) 500× magnification.

Figure 4.

Representative micrograph of a bracket base showing enamel fragments adherent to the composite resin. (A) 200× magnification. (B) 500× magnification.

Figure 5.

Representative micrograph of a bracket base showing no morphologic evidence of enamel presence. (A) 200× magnification. (B) 500× magnification.

DISCUSSION

The literature is rich with studies describing the bond failure of orthodontic brackets. Most were carried out in vitro and on small samples of teeth, usually premolars.2,4,9,11,19,20

These conditions could represent serious limitations as concerns the scientific relevance of the research; furthermore, potential differences in the debonding pattern, relative to the tooth position in the arch, do not emerge. To date, minimal information is available regarding possible differences in the debonding pattern between maxillary and mandibular teeth.8,22

In the present ex vivo study, maxillary incisor and canine brackets showed the lowest percentage of residual debris, while corresponding tooth-type brackets in the mandibular arch presented higher percentages, in accordance with the findings of Pont et al.8 First molar brackets, either maxillary or mandibular, displayed the highest percentages.

Because the bracket debonding procedure should ideally preserve the integrity of the enamel layer, the persistence of remnant material on the tooth after debonding represents one desirable occurrence. A bond failure leaving more residual debris on the bracket base is undesirable because of the increased probability of tooth enamel damage.11,12,23

Stain and decreased resistance to organic acids may be the result of iatrogenic injury, making the tooth more susceptible to plaque decalcification.6 A small number of studies are available regarding enamel detachments during debonding (very few were conducted in vivo), and the related findings are often contradictory.4,7,24,25 One possible explanation for this fact is that enamel damage is more likely to occur in extracted teeth, as they are more desiccated than vital teeth.24 Another limitation of some studies4 is that they did not adopt an adequate SEM magnification (20×) to distinguish enamel from resin.

In the present study, three morphologically different types of images were observed under the SEM: a thin enamel coat over the resin surface (83%) (Figure 3A,B), sizable enamel fragments attached to the composite resin (7%) (Figure 4A,B),7 or a smooth surface with no evidence of enamel presence (10%) (Figure 5A,B). It is critical to differentiate between the first and the second situation. The first finding corresponds to some enamel prism cores and interprismatic enamel that are not relevant from a clinical standpoint, whereas the second one is characterized by the typical honeycomb pattern, suggesting a fracture of sizable enamel fragments (area ranging from 306 to 1247 µm2) during debonding. In agreement with Pont et al.,8 calcium remnants were noticed on all evaluated bracket bases at the EDX analysis, even on the specimens with no morphologic evidence of enamel presence (group C) at SEM analysis; in any event, the Ca/Si ratio (5.40%) in this group was significantly lower than the Ca/Si ratio in groups A and B (16.21% and 18.77%, respectively). On the other hand, the Ca/Si ratio between group A and group B was not statistically different. This outcome indicates that through this kind of analysis it is not possible to distinguish between situations characterized by a different clinical relevance. Therefore, even though the EDX spectometry is an objective method and provides quantitative data, it should be associated with the morphologic evaluation given by the SEM to assess the damage severity.

According to the findings of the present study, because calcium remnants were noticed on each specimen under EDX, even on those bases with no morphologic evidence of enamel presence under SEM, a restitutio ad integrum is not possible. Furthermore, in 7% of the brackets showing resin remnants (n = 818), the damage could be visible, could be detectable, and could have some clinical relevance; considering the whole bracket population (n = 1068), the prevalence of enamel damage is 5.4%, which should represent the risk for a clinician to create a iatrogenic enamel injury during debonding.

Further studies should be conducted to verify whether fractured enamel surfaces are still visible after the cleanup procedure and to investigate the influence of saliva in the remineralization of these lesions in a long-term follow-up. To date, the objective of atraumatic debonding has not yet been achieved; therefore, clinicians must be aware that debonding may bring about this occurrence. Therefore, the debonding procedure, often delegated, should be taken into proper consideration and regarded with more respect, as it is still part of the treatment and the clinician is personally responsible for any undesired consequences.

CONCLUSIONS

Within the experimental conditions of this ex vivo study:

No statistically significant difference was found in the percentage of resin remnants between upper and lower dental arches for premolar or molar brackets.

Statistically significant differences between upper and lower dental arches were observed for incisor and canine brackets; maxillary incisor and canine brackets showed the lowest percentages of resin remnants.

The presence of enamel was found in 100% of the bracket bases at the EDX analysis; however, 10% showed no evidence of enamel presence, 83% presented a thin enamel coat, and 7% showed sizable enamel fragments at the SEM analysis.

The prevalence of enamel damage in respect to the whole bracket population is 5.4%.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shuler FS, Van Waes H. SEM-evaluation of enamel surface after removal of fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Dent. 2003;16:390–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozer T, Basaran A, Kama JD. Surface roughness of the restored enamel after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2010;137:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alessandri Bonetti G, Zanarini M, Incerti Parenti S, Lattuca M, Marchionni S, Gatto MR. Evaluation of enamel surfaces after bracket debonding: an in-vivo study with scanning electron microscopy. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2011;140:696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang WN, Meng CL, Tarng TH. Bond strength: a comparison between chemical coated and mechanical interlock bases of ceramic and metal brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1997;111:374–381. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(97)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorel O, El Alam R, Chagneaub F. Comparison of bond strength between simple foil mesh and laser-structured base retention brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2002;122:260–266. doi: 10.1067/mod.2002.125834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Hsu M, Chang K, Kuang S, Chen P, Gung Y. Failure analysis: enamel fracture after debonding orthodontic brackets. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:1071–1077. doi: 10.2319/091907-449.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stratmann U, Schaarschmidt K, Wegener H, Ehner U. The extent of enamel surface fractures. A quantitative comparison of thermally debonded ceramic and mechanically debonded metal brackets by energy dispersive micro- and image-analyses. Eur J Orthod. 1996;18:655–662. doi: 10.1093/ejo/18.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pont HB, Özcan M, Bagis B, Ren Y. Loss of surface enamel after bracket debonding: an in-vivo and ex-vivo evaluation. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2010;138:387.e1–387.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishara S, Truelove T. Comparisons of different debonding techniques for ceramic brackets: an in vitro study. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1990;98:145–153. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(90)70008-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ødegaard T, Segnes D. Shear bond strength of metal brackets compared with a new ceramic bracket. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1988;94:20–26. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(88)90028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habibi M, Nik TH, Hooshmand T. Comparison of the debonding characteristics of metal and ceramic orthodontic brackets to enamel: an in vitro study. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2007;132:675–679. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph VP, Rossouw PE. The shear bond strengths of stainless steel and ceramic brackets used with chemically and light-activated composite resins. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1990;97:168–175. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(90)70084-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeroudi MT. Enamel fracture caused by ceramic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1991;99:97–99. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(91)70111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redd TB, Shivapura PK. Debonding ceramic brackets: effects on enamel. J Clin Orthod. 1991;99:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valletta R, Prisco D, De Santis R, Ambrosio L, Martina R. Evaluation of the debonding strength of orthodontic brackets using three different bonding systems. Eur J Orthod. 2007;29:571–577. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sfondrini MF, Gatti S, Scribante A. Shear bond strength of self-ligating brackets. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33:71–74. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eliades T, Bourauel C. Intraoral aging of orthodontic materials: the picture we miss and its clinical relevance. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2005;127:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zachrisson BU, Büyükyilmaz T. Bonding in orthodontics. In: Graber LW, Vanarsdall RL, Vig KWL, editors. Orthodontics Current Principles and Techniques 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012. p. 744. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al Shamsi AH, Cunningham JL, Lamey PJ, Lynch E. Three dimensional measurement of residual adhesive and enamel loss on teeth after debonding of orthodontic brackets: an in-vitro study. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2007;131:301.e9–301.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitahara-Céia FMF, Mucha JN, Marques dos Santos P. Assessment of enamel damage after removal of ceramic brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2008;134:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brosh T, Kaufman A, Balabanovsky A, Vardimon AD. In vivo debonding strength and enamel damage in two orthodontic debonding methods. J Biomech. 2005;38:1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoll M, Gwinnett AJ, Wollf MS. Shear bond strengths of brackets bonded to anterior and posterior teeth. Am J Orthod. 1986;89:476–479. doi: 10.1016/0002-9416(86)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yapel MJ, Quick DC. Experimental traumatic debonding of orthodontic brackets. Angle Orthod. 1994;64:131–136. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1994)064<0131:ETDOOB>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theodorakopolou LP, Sadowsky PL, Jacobson A, Lacefield W., Jr Evaluation of the debonding characteristics of 2 ceramic brackets: an in vitro study. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2004;125:329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng HY, Chen CH, Li CL, Tsai HH, Chou TH, Wang WN. Bond strength of orthodontic light-cured resin-modified glass ionomer cement. Eur J Orthod. 2011;33:180–184. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]