Abstract

Calciotropic hormones, parathyroid hormone (PTH) and calcitonin are involved in the regulation of bone mineral metabolism and maintenance of calcium and phosphate homeostasis in the body. Therefore, an understanding of environmental and genetic factors influencing PTH and calcitonin levels is crucial. Genetic factors are estimated to account for 60% of variations in PTH levels, while the genetic background of interindividual calcitonin variations has not yet been studied. In this review, we analyzed the literature discussing the influence of environmental factors (lifestyle factors and pollutants) on PTH and calcitonin levels. Among lifestyle factors, smoking, body mass index (BMI), diet, alcohol, and exercise were analyzed; among pollutants, heavy metals and chemicals were analyzed. Lifestyle factors that showed the clearest association with PTH levels were smoking, BMI, exercise, and micronutrients taken from the diet (vitamin D and calcium). Smoking, vitamin D, and calcium intake led to a decrease in PTH levels, while higher BMI and exercise led to an increase in PTH levels. In terms of pollutants, exposure to cadmium led to a decrease in PTH levels, while exposure to lead increased PTH levels. Several studies have investigated the effect of chemicals on PTH levels in humans. Compared to PTH studies, a smaller number of studies analyzed the influence of environmental factors on calcitonin levels, which gives great variability in results. Only a few studies have analyzed the influence of pollutants on calcitonin levels in humans. The lifestyle factor with the clearest relationship with calcitonin was smoking (smokers had increased calcitonin levels). Given the importance of PTH and calcitonin in maintaining calcium and phosphate homeostasis and bone mineral metabolism, additional studies on the influence of environmental factors that could affect PTH and calcitonin levels are crucial.

Keywords: environmental factors, PTH, calcitonin, pollutants, lifestyle factors, calcium, phosphate, vitamin D

1. Introduction

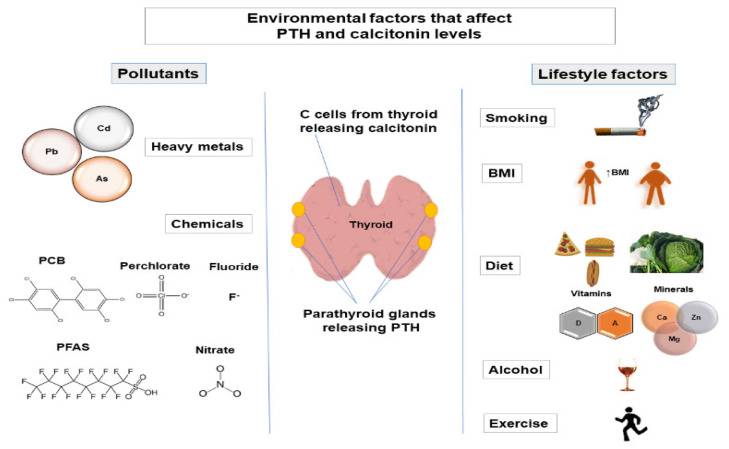

Maintenance of calcium homeostasis in the body is crucial since calcium regulates various physiological processes, including cellular signaling, protein and enzyme function, neurotransmission, contractility of the muscles, and blood coagulation [1]. Calcium homeostasis is regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcitonin, the active form of vitamin D (1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (1,25(OH)2D3)), and serum calcium and phosphate levels. Regulation of phosphate metabolism is also important as phosphate is involved in protein and enzyme function, cell signaling, and skeletal mineralization and is a component of cell membranes and nucleic acids [2,3]. The main factors that regulate phosphate homeostasis are PTH, fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23), 1,25(OH)2D3, and Klotho [3]. Calcitonin is also involved in the regulation of phosphate levels [4,5]. PTH is released from the parathyroid glands [6], while calcitonin is released from thyroid C-cells [7]. Alternation of PTH levels can lead to the development of hyperparathyroidism and hypoparathyroidism. Changes in calcitonin levels have also been observed in pathological conditions (such as medullary thyroid carcinoma [8]). Therefore, variations in PTH and calcitonin levels may indicate that the normal functioning of parathyroid glands and thyroid is altered. Various factors can affect PTH and calcitonin levels, such as genetic factors [9,10,11], demographic factors (age [12,13,14], sex [15,16,17]), and environmental factors [18,19,20,21]. It is estimated that genetic factors account for 60% of variations in PTH levels [9], while the amount to which genetic factors contribute to interindividual variation in calcitonin levels has not been studied. This review aims to provide an insight into environmental factors (lifestyle factors and pollutants) that affect PTH and calcitonin levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Environmental factors (lifestyle factors and pollutants) that affect PTH and calcitonin levels. As, arsenic; BMI, body mass index; Ca, calcium; Cd, cadmium; F, fluoride; Mg, magnesium; Pb, lead; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyl; PFAS, perfluoroalkyl substances; PTH, parathyroid hormone; Zn, zinc.

2. Involvement of PTH and Calcitonin in the Regulation of Calcium and Phosphate Levels

Calcium and phosphate levels in the body are regulated by the complex intestine–bone–kidney–parathyroid axis [22]. Calcium homeostasis is regulated by PTH, calcitonin, 1,25(OH)2D3, and serum phosphate and calcium levels. PTH increases calcium levels in the body, and calcitonin decreases calcium levels in the body. PTH increases serum calcium levels by activating osteoclasts (cells involved in bone resorption) and absorbing calcium in the kidneys. Calcitonin lowers calcium levels by inhibiting osteoclasts [23]. Additionally, 1,25(OH)2D3 stimulates intestinal calcium absorption [24]. Increasing serum levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 and calcium decrease PTH secretion, while increasing serum phosphate levels increase PTH secretion [25]. In addition to PTH, phosphate levels are mainly regulated by FGF-23, 1,25(OH)2D3, Klotho, and dietary phosphate [3,22,26,27], while calcitonin also affects phosphate levels [4,5]. PTH, FGF-23, and Klotho decrease serum phosphate levels (by inhibiting renal phosphate reabsorption), while 1,25(OH)2D3 increases serum phosphate levels (by increasing renal phosphate reabsorption, phosphate absorption from the intestine, and phosphate release from the bones) [2,22]. It has been suggested that FGF-23 acts in a negative feedback loop with PTH [28]; PTH stimulates FGF-23 production [28], while FGF-23 has been shown to inhibit PTH secretion indirectly (by increasing urinary phosphate excretion) and directly (by acting directly on parathyroid glands) [29]. Additionally, a negative feedback mechanism was observed between FGF-23 and 1,25(OH)2D3; 1,25(OH)2D3 increases FGF-23 levels, and FGF-23 decreases 1,25(OH)2D3 levels (by suppressing the expression of 1α-hydroxylase—the enzyme responsible for the production of 1,25(OH)2D3) (reviewed in [22]).

3. Environmental Factors That Affect PTH and Calcitonin Levels

3.1. Lifestyle Factors

3.1.1. Smoking

Many studies have investigated the impact of smoking on PTH levels. Most of these studies reported a decrease in PTH levels in smokers (Table 1). The three largest studies that involved more than 7000 participants confirmed these results [30,31,32]. The study of Diaz-Gomez et al., even showed that maternal smoking decreases PTH levels in newborns [33]. The heavy metal cadmium and thiocyanate (that is converted from cyanide in tobacco) which are also toxic components of tobacco smoke have been shown to reduce PTH levels [19,34]. Jorde et al., observed that after smoking cessation, PTH levels return to normal [30]. The mechanism by which smoking affects PTH levels is not fully understood. PTH–vitamin D axis dysfunction has been observed in smokers [35]. Many studies have found a decrease in 1,25(OH)2D levels among smokers (reviewed in [36]). Although under physiological conditions, a decrease in 1,25(OH)2D levels was accompanied by an increase in PTH levels, this was not observed in smokers in most studies. Need et al., suggested that smoking impairs osteoblast function, increasing serum calcium, which in turn leads to a decrease in PTH levels [37]. Jorde et al. did not rule out a possible direct toxic effect of smoking on parathyroid cells [30]. Additionally, it has been suggested that a decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) among smokers [38] may contribute to PTH–vitamin D axis dysfunction [35].

Table 1.

Lifestyle factors that affect PTH levels in humans.

| Factor | Effect on Hormone Levels | Number of Participants | Participants | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Smoking | ↓PTH | 170 (men) | Healthy adults | [113] |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 376 | Healthy adults | [114] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 510 | Healthy adults | [62] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 535 | Healthy adults | [115] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 1203 | Healthy adults | [116] | |

| Smoking | ↓iPTH | 177 | Healthy adults | [117] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH (in mothers and their new-borns) | 61 | Mothers and their new-borns | [33] | |

| Smoking | ↓iPTH | 31 (men) | Healthy adults | [118] | |

| Smoking | ↔iPTH | 43 (women) | Healthy adults | [118] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 7896 | Healthy adults | [30] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 405 (women) | Healthy adults | [37] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 958 (men) | Healthy adults | [119] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 136 | Healthy adults | [92] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 406 | Healthy adults | [38] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 3212 | 2758 healthy adults + 454 participants with coronary heart disease | [120] | |

| Smoking | ↓iPTH | 347 | Healthy adults | [61] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 1206 | Healthy adults | [121] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 1068 | Healthy adults | [122] | |

| Smoking | ↓iPTH | 345 | 216 healthy adults + 129 men with earlier partial gastrectomy | [123] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 7561 | Healthy adults | [31] | |

| Smoking | ↓iPTH | 3949 | Healthy adults | [124] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 32 | Healthy adults | [125] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 414 | Healthy adults | [126] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 2810 | Healthy adults | [127] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 1205 | Healthy adults | [128] | |

| ↔PTH | 719 (men) | ||||

| Smoking | ↑PTH | 128 (participants with low body weight (≤75 kg)) |

Healthy adults | [129] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 1067 (women) | Healthy adults | [130] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 47 (women) | Healthy adults | [131] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 489 (women) | Healthy adults | [91] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 908 | Healthy adults | [132] | |

| Smoking | ↓PTH | 294 (women) | Healthy adults | [18] | |

| Smoking | ↔PTH | 58 | Healthy adults | [133] | |

| Alcohol consumption | Alcohol | ↔PTH | 535 | Healthy adults | [115] |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 510 | Healthy adults | [62] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 1203 | Healthy adults | [116] | |

| Alcohol | ↓PTH | 7896 | Healthy adults | [30] | |

| Alcohol | ↓PTH | 136 | Healthy adults | [92] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 1206 | Healthy adults | [121] | |

| Alcohol | ↓iPTH | 3949 | Healthy adults | [124] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 414 | Healthy adults | [126] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 1205 | Healthy adults | [128] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 27 (men) | Healthy adults, alcoholics | [134] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 21 (men) | Healthy adults, alcoholics | [135] | |

| Alcohol | ↓PTH | 6 | Healthy adults | [90] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 47 | Healthy adults, alcoholics | [95] | |

| Alcohol | ↔PTH | 26 | Healthy adults | [136] | |

| Alcohol | ↓PTH | 136 | Healthy adults | [92] | |

| Alcohol | ↓PTH (increase in PTH levels after alcohol withdrawal) | 26 | Healthy adults, alcoholics | [137] | |

| Alcohol | ↔iPTH | 36 (men) | Healthy adults, alcoholics | [138] | |

| Alcohol | ↓immunoreactive PTH | 104 (men) | Healthy adults | [139] | |

| Increased BMI | ↑BMI | ↔PTH | 535 | Healthy adults | [115] |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 510 | Healthy adults | [62] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 1203 | Healthy adults | [116] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 7896 | Healthy adults | [30] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 7561 | Healthy adults | [31] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 3212 | 2758 healthy adults + 454 participants with coronary heart disease | [120] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑iPTH | 347 | Healthy adults | [61] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 1206 | Healthy adults | [121] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 2810 | Healthy adults | [127] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 1205 | Healthy adults | [128] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑iPTH | 3949 | Healthy adults | [124] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑iPTH | 160 | Healthy adults | [140] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 483 | Healthy adults | [141] | |

| ↑BMI | ↔PTH | 57 | Healthy adults | [79] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 57 (men) | Healthy adults | [142] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 1628 | Dialysis patients | [143] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 419 | Children | [144] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 82 (women) | Healthy adults | [145] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 316 | Healthy adults | [146] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑iPTH | 332 | Healthy adults | [147] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 40 | Bariatric surgery patients and healthy controls | [148] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 316 | Patients who had attended the obesity clinics | [149] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 42 | Patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy | [150] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 516 | Healthy adults | [151] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 3248 (women) | Healthy adults | [152] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 669 (men) | Healthy adults | [153] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑iPTH | 590 | Hemodialysis patients | [154] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 2758 healthy adults + 454 participants with coronary heart disease | Healthy adults | [155] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 250 | Healthy adults | [156] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 608 | Healthy adults | [157] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 496 (men) | Patients with chronic kidney disease | [158] | |

| ↑BMI | ↔PTH | 1436 | Healthy adults | [159] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 304 (women) | Healthy adults | [160] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 156 | Obese children | [161] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 3002 | Healthy adults | [162] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 810 (women) | Healthy adults | [163] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH (PTH = 21.4–65.8 pg/ mL) |

131 | Healthy adults and subjects with primary hyperparathyroidism | [41] | |

| ↓PTH (PTH = 147–2511.7 pg/mL) | 132 | ||||

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 383 (women) | Healthy adults | [164] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 2848 | Healthy adults | [165] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 453 | Healthy adults | [166] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 25 | Anorexia nervosa patients | [167] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 98 | Healthy adults | [168] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 625 | Healthy adults | [71] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑PTH | 294 | Healthy adults | [18] | |

| Diet | Different sorts of vegetables, sausages, salami, mushrooms, eggs, white bread | ↑PTH | 1180 | Healthy adults | [21] |

| Bran bread | ↓PTH | ||||

| Traditional Inuit diet (diet mainly of marine origin taken by Greenland inhabitants) |

↓PTH | 535 | Healthy adults | [115] | |

| ↑Total calorie intake | ↔iPTH | 3949 | Healthy adults | [124] | |

| Protein intake | ↔PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| Coronary Health Improvement Project (CHIP). CHIP intervention, which promotes a plant-based diet with little dairy intake and meat consumption | ↑PTH (after 6 weeks) | 119 (women) | Healthy adults | [57] | |

| High-phosphorus, low-calcium diets |

↑PTH | 16 | Healthy adults | [50] | |

| The traditional Brazilian diet (fruits, vegetables, and small amounts of meat) | ↓PTH | 111 | Severely obese adults | [169] | |

| Extra virgin olive oil supplementation | ↔PTH | 111 | Severely obese adults | [169] | |

| Moderate dietary protein restriction | ↑PTH | 18 | Patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria and calcium nephrolithiasis | [55] | |

| Vegans vs omnivores | ↑PTH in vegans | 155 | Healthy adults | [58] | |

| The “Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension” (DASH) diet, rich in fiber and low-fat dairy | ↔PTH | 334 | Healthy adults | [170] | |

| Vegans vs. omnivores | ↔PTH | 210 (women) | Healthy adults | [171] | |

| High protein and high dairy group | ↓PTH | 30 (women) | Healthy adults | [56] | |

| Adequate protein and medium dairy group | ↓PTH | 30 (women) | Healthy adults | [56] | |

| Adequate protein and low dairy | ↑PTH | 30 (women) | Healthy adults | [56] | |

| Diet with low calcium:phosphorus ratio | ↑PTH | 147 (women) | Healthy adults | [51] | |

| Low-protein diets (diets containing 0.7 and 0.8 g protein/kg) | ↑PTH | 8 (women) | Healthy adults | [54] | |

| Higher consumption of a proinflammatory diet | ↑PTH | 7679 | Adults with/without chronic kidney disease | [53] | |

| High fruit and vegetable intake (consuming more than 3 servings of fruit and vegetables) | ↓PTH | 56 | Children | [172] | |

| Dietary calorie, vitamin D, and magnesium intake | ↔PTH | 98 | Healthy adults | [168] | |

| Vegetarians vs. controls | ↑iPTH | 44 | Healthy adults | [59] | |

| Intake of dietary fiber | ↑iPTH | ||||

| Dietary calcium intake | ↓iPTH | ||||

| Coffee | ↓iPTH | 181 (men) | Healthy adults | [61] | |

| Coffee, tea | ↔PTH | 510 | Healthy adults | [62] | |

| Coffee | ↓PTH | 3427 (men) | Healthy adults | [30] | |

| Caffeine intake | ↔PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| Caffeine intake | ↔PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| Vitamin D supplements | ↔PTH | 510 | Healthy adults | [62] | |

| Vitamin D supplements | ↓PTH | 4469 (women) | Healthy adults | [30] | |

| Vitamin D supplements | ↓iPTH | 3949 | Healthy adults | [124] | |

| Vitamin D supplements | ↔PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| Vitamin D supplements | ↓PTH | 414 | Healthy adults | [126] | |

| Vitamin D intake | ↓PTH | 316 | Healthy adults | [146] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 250 | Healthy adults | [156] | |

| Vitamin D intake | ↓PTH | 376 (women) | Healthy adults | [173] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | Meta-analysis | [70] | ||

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 77 | Healthy adults | [174] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 247 (women) | Healthy adults | [175] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 877 (women) | Healthy adults | [176] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 270 (women) | Healthy adults | [75] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 313 | Healthy adults | [177] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 103 (women) | Elderly institutionalised women | [178] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↔PTH | 128 (women) | Healthy adults | [179] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 145 (women) | Healthy adults | [180] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 60 (men) | Healthy adults | [181] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 192 (women) | Healthy adults | [182] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 191 (women) | Ambulatory elderly women | [183] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↔PTH | 208 (women) | Healthy adults | [184] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 314 | Healthy adults | [185] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 1368 | Healthy adults | [127] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 338 | Healthy adults | [186] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 218 | Older patients | [187] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↔PTH | 215 | Healthy adults | [188] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 242 | Healthy adults | [189] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 165 | Healthy overweight subjects | [190] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 153 | Healthy adults | [191] | |

| Multiple micronutrient and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 153 (women) | Healthy adults | [191] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 158 | Overweight subjects | [192] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 202 | Healthy adults | [193] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 94 | Healthy adults | [194] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↔PTH | 90 | Coronary artery disease patients | [195] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↔PTH | 151 | Healthy adults | [196] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 89 | Obese with pre- or early diabetes | [197] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 112 | Hypertensive patients | [198] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 230 | Adults with depression | [199] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 77 (women) | Healthy adults | [200] | |

| Vitamin D and calcium supplementation | ↓PTH | 173 (women) | Healthy adults | [201] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↓PTH | 112 | Parkinson disease | [202] | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | ↔PTH | 82 | Healthy adults | [203] | |

| Vitamin A intake | ↔PTH | 606 | Healthy adults | [72] | |

| Total calcium and vitamin A intake | ↓PTH | 625 | Healthy adults | [71] | |

| Vitamin A intake | ↓PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| The dietary intake of minerals (calcium, phosphate, and magnesium) and vitamin D | ↔PTH | 127 | Healthy adults | [204] | |

| Calcium supplements | ↓PTH | 414 | Healthy adults | [126] | |

| Calcium supplements | ↓PTH | 51 | Toddlers | [205] | |

| Calcium intake | ↓PTH | 7896 | Healthy adults | [30] | |

| Dietary calcium intake | ↓PTH | 181 | Healthy adolescents |

[206] | |

| Calcium intake | ↓PTH | 1203 | Healthy adults | [116] | |

| Calcium intake | ↓PTH | 3212 | 2758 healthy adults + 454 participants with coronary heart disease | [120] | |

| Calcium intake | ↔PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| Calcium intake | ↓iPTH | 3949 | Healthy adults | [124] | |

| Dietary calcium intake | ↓PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| Calcium intake | ↔PTH | 57 | Healthy adults | [79] | |

| Animal/total calcium intake | ↓PTH | 316 | Healthy adults | [146] | |

| Dietary calcium | ↔PTH | 155 (women) | Healthy adults | [207] | |

| Calcium supplements | ↓PTH | 566 | Healthy adults | [208] | |

| Intake of calcium | ↓PTH | 82 | Healthy adults | [203] | |

| Calcium intake derived from milk | ↓PTH | 245 (women) | Healthy adults | [173] | |

| Magnesium intake | ↔PTH | 57 | Healthy adults | [79] | |

| Magnesium intake | ↔PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| Magnesium supplementation | ↑PTH | 10 (patients with hypoparathyroidism) | Patients with osteoporosis | [78] | |

| ↓PTH | 10 (patients with vitamin D insufficiency) | ||||

| Magnesium supplementation | ↑iPTH | 23 | Children with diabetes | [77] | |

| Zinc infusion | ↔PTH | 38 | Patients of short stature, diabetes mellitus, and controls | [83] | |

| Phosphorus intake | ↔PTH | 7652 | Healthy adults | [32] | |

| Intervention group (exercise, vitamin D, calcium, protein supplementation) |

↓iPTH | 220 | Patients that were on bariatric surgery | [209] | |

| Exercise | Exercise | ↓PTH | 7561 | Healthy adults | [31] |

| Exercise | ↔PTH | 1288 | Healthy adults | [63] | |

| Exercise | ↓PTH | 3427 (men) | Healthy adults | [30] | |

| Exercise | ↔PTH | 414 | Healthy adults | [126] | |

| Exercise | ↔PTH | 1205 | Healthy adults | [128] | |

| ↑Sitting | ↑PTH | 566 | Healthy adults | [208] | |

| Exercise | ↓PTH | 625 | Healthy adults | [71] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 12 (men) | Healthy adults | [210] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 20 | Healthy adults | [211] | |

| Exercise | ↓PTH | 54 | Chronic kidney disease patients | [212] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 29 | Boys and young men | [213] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 11 (men) | Healthy adults | [214] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 25 | Healthy adults | [215] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 12 (men) | Healthy adults | [216] | |

| Exercise | ↔iPTH | 100 (women) | Healthy adults | [217] | |

| Exercise | ↑iPTH | 21 | Healthy adults | [218] | |

| Exercise | ↑iPTH | 7 (men) | Healthy adults | [219] | |

| Exercise | ↓PTH | 5 (women) | Healthy adults | [220] | |

| Exercise | ↑iPTH | 9 (men) | Healthy adults | [221] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH (during the exercise with the highest intensity) | 10 (men) | Healthy adults | [222] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH (during the exercise) ↔PTH (postexercise period) |

10 (men) | Healthy adults | [223] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 10 (women) | Healthy adults | [104] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 51 (men) | Healthy adults | [224] | |

| Exercise | ↓iPTH (moderate exercise) ↑iPTH (intensive exercise) |

21 (women) | Healthy adults | [225] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 14 (women) | Healthy adults | [226] | |

| Exercise | ↓PTH (with the onset of exercise) ↑PTH (intensive exercise) |

10 (men) | Healthy adults | [227] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 17 (men) | Healthy adults | [228] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 100 (men) | Healthy adults | [229] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 9 (men) | Healthy adults | [111] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 26 (women) | Healthy adults | [230] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 18 | Healthy adults | [112] | |

| Exercise | ↑iPTH | 8 (men) | Healthy adults | [231] | |

| Exercise | ↔PTH | 6 (men) | Healthy adults | [232] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 6 (men) | Healthy adults | [109] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 19 (men) | Healthy adults | [107] | |

| Exercise | ↔PTH | 13 (men) | Healthy adults | [110] | |

| Exercise | ↑PTH | 27 (men) | Healthy adults | [20] |

BMI, body mass index; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; PTH, parathyroid hormone. Decreased (↓), unchanged (↔), increased (↑).

Most studies investigating the effect of smoking on calcitonin levels have found an increase in calcitonin levels in smokers (Table 2). A large population study by Song et al., involving 10,566 participants showed an increase in calcitonin levels in male smokers [17]. Smoking affects the normal functioning of the thyroid gland [39]; however, the effect of smoking on calcitonin-producing C cells has not been elucidated [17]. The results of Tabassian et al. suggested that the lungs are the source of increased calcitonin in smokers rather than the thyroid. Specifically, smoking increases the release of calcitonin from neuroendocrine lung cells [40].

Table 2.

Lifestyle factors that affect calcitonin levels in humans.

| Factor | Effect on Hormone Levels | Number of Participants | Participants | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Smoking | ↔Calcitonin | 294 (women) | Healthy adults | [18] |

| Smoking | ↑Calcitonin | 9340 | People with type 2 diabetes | [48] | |

| Smoking | ↑Calcitonin | 142 (men) | Healthy adults | [233] | |

| Smoking | ↑Calcitonin | 58 | Healthy adults | [133] | |

| Smoking | ↑Calcitonin | 120 (men) | Healthy adults | [234] | |

| Smoking | ↑Calcitonin | 6341 (men) | Healthy adults | [17] | |

| Alcohol consumption | Alcohol | ↔Calcitonin | 26 | Healthy adults | [136] |

| Alcohol | ↔Calcitonin | 93 | Healthy adults | [96] | |

| Alcohol | ↓Calcitonin (in a heavy drinking group) | 47 | Alcoholics | [95] | |

| Alcohol | ↑Calcitonin | 50 | Alcoholics + controls | [94] | |

| Increased BMI | ↑BMI | ↔Calcitonin | 467 | Patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | [235] |

| ↑BMI | ↓Calcitonin | 294 | Healthy adults | [18] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑Calcitonin | 9340 | People with type 2 diabetes | [48] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑Calcitonin | 287 | Healthy adults | [233] | |

| ↑BMI | ↔Calcitonin | 4638 | Healthy adults | [17] | |

| ↑BMI | ↑Calcitonin | 31 | Patients with chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis | [236] | |

| Vitamins and minerals | Vitamin D supplementation | ↔Calcitonin | 270 (women) | Healthy adults | [75] |

| Zinc infusion | ↓Calcitonin | 38 | Patients of short stature, diabetes mellitus, and controls | [83] | |

| High dietary zinc | ↓Calcitonin | 21 | Healthy adults | [86] | |

| High dietary copper | ↔Calcitonin | 21 | Healthy adults | [86] | |

| Exercise | Exercise | ↔Calcitonin | 9 (men) | Healthy adults | [111] |

| Exercise | ↔Calcitonin | 18 | Healthy adults | [112] | |

| Exercise | ↔Calcitonin | 6 (men) | Healthy adults | [109] | |

| Exercise | ↑Calcitonin | 19 (men) | Healthy adults | [107] | |

| Exercise | ↔Calcitonin | 13 (men) | Healthy adults | [110] | |

| Exercise | ↔Calcitonin | 27 (men) | Healthy adults | [20] | |

| Raloxifene combined with aerobic exercise | ↑Calcitonin | 70 | Patients with osteoporosis | [108] |

BMI, body mass index. Decreased (↓), unchanged (↔), increased (↑).

3.1.2. Body Mass Index

Many studies have investigated the influence of body mass index (BMI) on PTH levels. Most studies have shown that an increase in BMI is accompanied by an increase in PTH levels (Table 1). However, a study by Yuan et al., showed a positive correlation between BMI and PTH levels in subjects with lower PTH levels (below 65.8 pg/mL), while a negative correlation was observed between BMI and PTH levels in the group of patients with high PTH levels (above 147 pg/mL) [41]. There are several possible explanations for the positive correlation between BMI and PTH levels. The first possibility is that weight gain leads to an increase in PTH levels by sequestration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) in adipose tissue (since 25(OH)D is soluble in fat) [42,43]. Because PTH and 25(OH)D are inversely related, a decrease in 25(OH)D levels increases PTH levels. Another possibility is that an increase in PTH levels causes weight gain. Because PTH can activate 1α-hydroxylase (the enzyme responsible for the production of 1,25(OH)2D), an increase in PTH levels can lead to an increase in 1,25(OH)2D levels. Both PTH and 1,25(OH)2D increase calcium levels. Increased calcium levels in adipocytes result in increased lipid storage (by activation of phosphodiesterase 3β which reduces catecholamine-induced lipolysis [44,45]). A possible explanation of the negative correlation between PTH and BMI in patients with high PTH levels is that PTH in higher concentrations inhibits adipogenesis, consequently resulting in weight loss [46]. Additionally, high-dose PTH has been shown to increase the expression of thermogenesis genes, resulting in white adipose browning [47].

Several studies have investigated the association between BMI and calcitonin levels, reporting conflicting results (Table 2). The largest study, which included 9340 people with type 2 diabetes, showed a positive correlation between BMI and calcitonin levels [48]. However, a study by Song et al., conducted on 4638 healthy individuals did not show an association between BMI and calcitonin [17]. Although the relationship between calcitonin levels and BMI in humans has not been fully elucidated, experimental studies have shown that salmon calcitonin intake causes weight loss (reviewed in [49]). These authors also described some additional compounds that target the calcitonin receptor and that could be used as an option in the treatment of obesity [49].

3.1.3. Diet

Different types of food can affect the level of PTH in the body (Table 1). A diet high in phosphorus and low in calcium has been shown to increase PTH levels [50,51]. This is logical because both high serum phosphate levels and low serum calcium levels are signals to increase PTH release [52]. Phosphorus is present in various types of food and food additives, while dairy products contain a large amount of calcium. Increased intake of dairy products and decreased intake of highly processed food should increase calcium levels and reduce phosphorus levels [51]. Processed foods such as sausages, salami, and white bread [21] and a proinflammatory diet (processed and red meat, refined carbohydrates, and fried food) [53] have been observed to increase PTH levels. Consumption of this type of food increases BMI, which is positively correlated with PTH levels (Table 1). A decrease in PTH levels was observed in consumers of bran bread [21]. A low–protein diet was associated with an increase in PTH levels [54,55,56]. Interestingly, the consumption of plant foods also led to an increase in PTH levels [21,57]. Therefore, vegans [58] and vegetarians [59] had higher levels of PTH than controls. A possible explanation for this is that higher plant food intake increases serum phosphorus levels (due to pesticide treatment of plants) [60]. PTH levels either decreased [30,61] or did not change [32,62,63] after coffee consumption.

The effect of different types of food on calcitonin levels has not been studied to date. Several studies have shown that food intake (without specifying the type of food) does not affect calcitonin levels [64,65]. Zayed et al., have shown that calcitonin levels increase after ingestion of food (without specifying the type of food) [66]. A study in pigs showed that a diet high in phosphorus increased calcitonin levels [67], while a study in rats showed that a diet high in fat increased calcitonin levels [68].

Micronutrients

Many studies have tested the effect of vitamin D on PTH levels because these two hormones act together. About 95% of vitamin D is synthesized in the skin after exposure to sunlight, while 5% of vitamin D comes from food [69]. Since PTH and the active form of vitamin D (1,25(OH)2D) are in an inverse relationship, it is not surprising that most of the studies have reported a decrease in PTH levels after vitamin D intake (Table 1). In some studies, however, there was no change in PTH levels after vitamin D intake (Table 1). On the other hand, a meta-analysis by Moslehi et al. confirmed that PTH levels are reduced by vitamin D intake [70]. Vitamin A intake decreased [63,71] or did not affect PTH levels [72]. In vitro studies in human [73] and bovine parathyroid cells [74] have shown that retinoic acid (a metabolite of vitamin A) directly suppresses PTH secretion.

No changes in calcitonin levels were observed after vitamin D intake [75]. While calcitonin stimulates 1,25(OH)2D synthesis, 1,25(OH)2D reduces the synthesis of calcitonin [76]. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct additional studies on the relationship between vitamin D and calcitonin.

Most studies have shown that calcium intake decreases PTH levels (Table 1), which is logical since PTH is released in hypocalcemia. Magnesium intake either increased [77,78] or did not affect [32,79] PTH levels. The relationship between PTH and magnesium is complex because PTH improves magnesium absorption [80], and magnesium reduces PTH secretion in a state of moderately low calcium concentration [81,82]. Zinc intake [83] did not affect PTH levels. However, a study in rats showed that a zinc-deficient diet increased PTH levels [84], while patients with primary hyperparathyroidism had decreased serum zinc levels [85].

Zinc intake decreased calcitonin levels [83,86], while copper intake [86] did not affect calcitonin levels. Intake of both zinc and copper resulted in inhibition of bone loss [87,88].

3.1.4. Alcohol

Studies investigating the influence of alcohol on PTH levels have yielded conflicting results. Some studies have found a decrease in PTH levels in alcoholics, while most studies have not reported a significant change in PTH levels due to alcohol consumption (Table 1). Moreover, the two largest studies involving more than 7000 participants yielded conflicting results; Jorde et al. observed a significant reduction in PTH levels in alcoholics [30], while Paik et al. did not notice a significant change in PTH levels in alcoholics [32]. Because alcohol inhibits bone regeneration [89], it has been suggested that alcohol intake reduces PTH levels [90,91,92] and increases calcitonin levels [93].

Several studies investigated calcitonin levels in alcoholics, and all yielded conflicting results (Table 2) with calcitonin levels that were increased [94], decreased [95], or unchanged [96] in alcoholics. Schuster et al. suggested that the reduction in calcitonin in chronic alcoholism is due to lower calcium concentration at this stage of alcohol consumption [95]. Interestingly, animal studies have shown that salmon calcitonin intake reduces various alcohol-related behaviors [97,98].

3.1.5. Exercise

Most studies that have investigated the influence of exercise on PTH levels have reported an increase in PTH levels during and after exercise (Table 1). However, most of these studies involved a small number of participants (less than 50). In contrast to the results of these studies, two studies involving as many as 7561 [31] and 3427 [30] participants reported a decrease in PTH levels after exercise. Causes of inconsistencies between studies may be the physical status of the participants; the age and gender of the participants; and the type, duration, and intensity of the exercise [99]. PTH is thought to increase during high-intensity exercise (reviewed in [100]). Although exercise is thought to be beneficial for BMD, some groups of professional athletes have had significant reductions in BMD [101,102]. It has been suggested that intense exercise leads to a decrease in calcium levels, resulting in an increase in PTH. Elevated PTH levels may contribute to bone resorption (reviewed in [103]). Moreover, Shea et al. suggested that calcium supplementation during exercise could reduce bone resorption [104]. However, other researchers have noticed an increase in PTH levels during exercise despite the stability of calcium levels (reviewed in [103]). Some other factors that can lead to an increase in PTH during exercise are increased catecholamine release (which stimulates PTH release) [105], increased aldosterone release (which increases PTH and calcitonin release) [80], and acidosis (stimulates PTH release) [106].

Calcitonin levels increased [107,108] or did not change [20,109,110,111,112] during exercise. However, these results should be verified in larger cohorts as most of these studies involved less than 30 participants (Table 2). Calcitonin levels could increase during exercise due to an increase in aldosterone levels [80].

3.2. Pollutants

3.2.1. Heavy Metals

Various heavy metals, such as cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and lead (Pb), affect PTH levels. Most studies have shown that PTH levels decrease after cadmium exposure (Table 3). Schutte et al., explained the decrease in PTH levels after cadmium exposure as a consequence of the direct osteotoxic effect of cadmium [18]. Exposure to cadmium leads to a decrease in bone density, resulting in increased release of calcium from bone tissue. The result of increased calcium release is the decrease in PTH levels [18]. In addition, cadmium has been shown to have a toxic effect on parathyroid glands [237]. However, some studies did not observe any effect [238,239,240] or observed an increase [241,242] in PTH levels in subjects exposed to cadmium. Studies in experimental animals observed an increase in PTH levels after cadmium exposure [243]. Arsenic exposure did not affect PTH levels [244]. Most studies reported an increase in PTH levels in subjects exposed to lead (Table 3). Lead inhibits 1α-hydroxylase (the enzyme responsible for the production of 1,25(OH)2D) [245], and since PTH and 25(OH)D are in an inverse relationship, a decrease in 25(OH)D levels results in an increase in PTH levels. PTH levels were also measured in Gulf War I veterans who were exposed to uranium, and it was shown that uranium exposure led to a decrease in PTH levels [246].

Table 3.

Pollutants affecting PTH and calcitonin levels in humans.

| Factor | Effect on Hormone Levels | Number of Participants | Participants | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy metals | Arsenic | ↔PTH– | 196 | Healthy adults | [256] |

| Arsenic | ↔iPTH | 774 | Children and new-borns | [244] | |

| Cadmium | ↓PTH | 719 (women) | Healthy adults | [34] | |

| Cadmium | ↓PTH | 85 (women) | Healthy adults | [257] | |

| Cadmium | ↓PTH | 51 (men) | Participants exposed to cadmium | [258] | |

| Cadmium | ↔PTH | 46 | Participants exposed to cadmium for a long period (some suffering from decreased tubular function) |

[240] | |

| Cadmium | ↔PTH | 41 (women) | Subjects with renal tubular dysfunction caused by exposure to cadmium | [259] | |

| Cadmium | ↓iPTH | 306 | Chronic peritoneal dialysis patients | [260] | |

| Cadmium in urine (maternal) | ↓PTH (in boys) ↑PTH (in girls) |

504 | 504 children in a mother–child cohort | [242] | |

| Cadmium in erythrocytes (maternal) | ↑PTH (in boys) ↓PTH (in girls) |

504 | |||

| Cadmium | ↔PTH | 60 | Patients with renal tubular damage caused by exposure to cadmium and healthy controls | [238] | |

| Cadmium | ↑PTH | 53 | Patients with renal tubular damage caused by exposure to cadmium and healthy controls | [241] | |

| Cadmium | ↓PTH (association lost after adjustment for smoking) | 908 (women) | Healthy adults | [132] | |

| Cadmium | ↓PTH, ↑Calcitonin |

294 (women) | Healthy adults | [18] | |

| Cadmium | ↔PTH | 146 | Healthy adults | [239] | |

| Lead | ↑PTH | 89 | Healthy adults | [245] | |

| Lead | ↔PTH | 719 (women) | Healthy adults | [34] | |

| Lead | ↔PTH | 51 | Dialysis patients | [261] | |

| Lead | ↑PTH | 146 (men) | Healthy adults | [262] | |

| Lead | ↑iPTH | 315 | Chronic peritoneal dialysis patients | [263] | |

| Lead | ↑PTH | 115 | Hemodialysis patients | [264] | |

| Lead | ↔PTH | 47 | Healthy adults | [265] | |

| Lead | ↑PTH | 73 (women) | Healthy adults | [266] | |

| Lead | ↑iPTH | 93 | Hemodialysis patients | [267] | |

| Uranium | ↔iPTH | 35 | Gulf War I veterans exposed to uranium | [268] | |

| Uranium | ↓iPTH | 35 | Gulf War I veterans exposed to uranium | [246] | |

| Chemicals | Persistent organochlorine compounds (CB-153) | ↔PTH | 908 (women) | Healthy adults | [132] |

| Persistent organochlorine compounds (p,p’-DDE) | ↔PTH | ||||

| PFAS | ↑PTH | 100 (men) | Healthy adults | [251] | |

| PCBs (exposed prenatally) | ↔PTH | 110 | Children in a mother–child cohort | [250] | |

| Fluoride | ↑PTH | 196 | Healthy adults | [256] | |

| Fluoride | ↑PTH | 84 | Patients with endemic fluorosis and healthy controls | [252] | |

| Fluoride | ↓PTH (in pregnant women) | 180 | Pregnant women and their new-borns | [269] | |

| ↔PTH (in new-borns) | |||||

| Lithium | ↔iPTH | 178 | Mother–child cohort | [270] | |

| Perchlorate | ↓PTH | 2207 (women) | Healthy adults | [19] | |

| Nitrate | ↓PTH | 4265 | Healthy adults | [19] | |

| Thiocyanate | ↓PTH | 4265 | Healthy adults | [19] |

iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyl; PFAS, perfluoroalkyl substances; p,p′-DDE, p,p′-diphenyldichloroethene; PTH, parathyroid hormone. Decreased (↓), unchanged (↔), increased (↑).

We found only one study that analyzed the influence of heavy metals on calcitonin levels. Schutte et al., observed an increase in calcitonin levels after cadmium exposure [18]. A study in rats showed that exposure to cadmium and lead decreased calcitonin levels [243,247]. Exposure of laying hens to cadmium led to a decrease in calcitonin levels [248], while a study in goldfish found no changes in calcitonin levels after cadmium exposure (although exposure to methylmercury increased calcitonin levels) [249].

3.2.2. Chemicals

Only a few studies have investigated the effect of chemicals on PTH levels in humans (Table 3). Exposure to persistent organochlorine compounds (p,p′-diphenyldichloroethene (p,p′-DDE) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs)) did not affect PTH levels [132,250]. Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) led to an increase in PTH levels [251]. Di Nisio et al. suggested that perfluoro-octanoic acid (PFOA) binds to vitamin D receptors, causing reduced 1,25(OH)D activity, which in turn increases PTH levels [251]. Fluoride exposure increases PTH levels [252]. According to researchers, excess fluoride alters calcium metabolism and potentially leads to secondary hyperparathyroidism (reviewed in [253]). Exposure to perchlorate, thiocyanate, and nitrate has led to a decrease in PTH levels, but the underlying mechanism of this action is not yet clear [19].

Data on the effect of chemicals and pesticides on calcitonin levels in humans are scarce. A study on goldfish has shown that bisphenol A inhibits the release of calcitonin [249]. Aroclor 1254 (PCB) increased calcitonin expression in rat thyroid [254]. Because many chemicals have an endocrine disruptive effect [255], further studies are needed on the impact of chemicals and pesticides on PTH and calcitonin levels.

4. Conclusions

In this review, we gave an insight into environmental factors that affect the levels of PTH and calcitonin, two hormones that regulate calcium and phosphate homeostasis. We included literature discussing lifestyle factors (smoking, BMI, diet, alcohol, and exercise) and pollutants (heavy metals and chemicals) (Figure 1). In terms of lifestyle factors, most studies have shown a decrease in PTH levels in smokers, a positive correlation between BMI and PTH, an increase in PTH levels during exercise, and a decrease in PTH levels after vitamin D and calcium intake (Table 1). The results of studies on the impact of alcohol consumption and intake of different types of food and micronutrients (except for vitamin D and calcium) showed great variability (Table 1). Regarding studies that analyzed the effect of pollutants on PTH levels, the clearest relationship was between PTH and cadmium, with PTH levels decreasing after cadmium exposure (Table 3). While arsenic exposure did not affect PTH levels, lead exposure resulted in increased PTH levels (Table 3). Several studies have investigated the influence of chemicals on PTH levels in humans. Moreover, data on the effect of chemicals and heavy metals on calcitonin levels in humans are scarce, and most of the knowledge, to date, relies on studies in experimental animals. As for the relationship between lifestyle factors and calcitonin, several studies have been conducted on humans and have given great variability in results. The most consistent results were related to smoking (an increase in calcitonin levels was observed in smokers) (Table 2). Given the important role that PTH and calcitonin play in maintaining calcium and phosphate homeostasis in the body, additional studies on the influence of environmental and genetic factors that could affect the levels of these two hormones are extremely important.

Abbreviations

1,25(OH)2D3, 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; As, arsenic; BMD, bone mineral density; BMI, body mass index; Ca, calcium; Cd, cadmium; F, fluoride; FGF-23, fibroblast growth factor 23; iPTH, intact parathyroid hormone; Mg, magnesium; Pb, lead; PCB, polychlorinated biphenyl; PFAS, perfluoroalkyl substances; PFOA, perfluoro-octanoic acid; p,p-DDE, p,p-diphenyldichloroethene; PTH, parathyroid hormone; Zn, zinc.

Author Contributions

T.Z. and M.B.L. conceived the review. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.B.L., I.G., N.P. and T.Z. revised and edited the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Croatian Science Foundation under the project “Regulation of Thyroid and Parathyroid Function and Blood Calcium Homeostasis” (No. 2593).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tebben P.J., Kumar R. Seldin and Geibisch’s The Kidney. Volume 2. Elsevier Inc.; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2013. The hormonal regulation of calcium metabolism; pp. 2249–2272. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi N.W. Kidney and phosphate metabolism. Electrolytes Blood Press. 2008;6:77–85. doi: 10.5049/EBP.2008.6.2.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattineni J., Friedman P.A. Regulation of hormone-sensitive renal phosphate transport. Vitam. Horm. 2015;98:249–306. doi: 10.1016/BS.VH.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talmage R.V., Vanderwiel C.J., Matthews J.L. Calcitonin and phosphate. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1981;24:235–251. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(81)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jafari N., Abdollahpour H., Falahatkar B. Stimulatory effects of short-term calcitonin administration on plasma calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and glucose in juvenile Siberian sturgeon Acipenser baerii. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020;46:1443–1449. doi: 10.1007/s10695-020-00801-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lofrese J.J., Basit H., Lappin S.L. Physiology, Parathyroid. StatPearls Publishing LLC; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pearse A.G. The cytochemistry of the thyroid C cells and their relationship to calcitonin. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1966;164:478–487. doi: 10.1098/RSPB.1966.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae Y.J., Schaab M., Kratzsch J. Calcitonin as biomarker for the medullary thyroid carcinoma. Recent Res. Cancer Res. 2015;204:117–137. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22542-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter D., De Lange M., Snieder H., MacGregor A.J., Swaminathan R., Thakker R.V., Spector T.D. Genetic contribution to bone metabolism, calcium excretion, and vitamin D and parathyroid hormone regulation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2001;16:371–378. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson-Cohen C., Lutsey P.L., Kleber M.E., Nielson C.M., Mitchell B.D., Bis J.C., Eny K.M., Portas L., Eriksson J., Lorentzon M., et al. Genetic variants associated with circulating parathyroid hormone. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017;28:1553–1565. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matana A., Brdar D., Torlak V., Boutin T., Popović M., Gunjača I., Kolčić I., Boraska Perica V., Punda A., Polašek O., et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies novel loci associated with parathyroid hormone level. Mol. Med. 2018;24:15. doi: 10.1186/s10020-018-0018-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deftos L.J., Weisman M.H., Williams G.W., Karpf D.B., Frumar A.M., Davidson B.J., Parthemore J.G., Judd H.L. Influence of age and sex on plasma calcitonin in human beings. N. Engl. J. Med. 1980;302:1351–1353. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198006123022407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haden S.T., Brown E.M., Hurwitz S., Scott J., Fuleihan G.E.H. The effects of age and gender on parathyroid hormone dynamics. Clin. Endocrinol. 2000;52:329–338. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrivick S.J., Walsh J.P., Brown S.J., Wardrop R., Hadlow N.C. Brief report: Does PTH increase with age, independent of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, phosphate, renal function, and ionized calcium? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015;100:2131–2134. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-4370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiegs R.D., Body J.J., Barta J.M., Heath H. Secretion and metabolism of monomeric human calcitonin: Effects of age, sex, and thyroid damage. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1986;1:339–349. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650010407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazeh H., Sippel R.S., Chen H. The role of gender in primary hyperparathyroidism: Same disease, different presentation. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012;19:2958–2962. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song E., Jeon M.J., Yoo H.J., Bae S.J., Kim T.Y., Kim W.B., Shong Y.K., Kim H.K., Kim W.G. Gender-dependent reference range of serum calcitonin levels in healthy Korean adults. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;36:365–373. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2020.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schutte R., Nawrot T.S., Richart T., Thijs L., Vanderschueren D., Kuznetsova T., Van Hecks E., Roels H.A., Staessen J.A. Bone resorption and environmental exposure to cadmium in women: A population study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008;116:777. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ko W.C., Liu C.L., Lee J.J., Liu T.P., Yang P.S., Hsu Y.C., Cheng S.P. Negative association between serum parathyroid hormone levels and urinary perchlorate, nitrate, and thiocyanate concentrations in U.S. adults: The national health and nutrition examination survey 2005–2006. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e115245. doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0115245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soria M., Haro C.G., Ansón M.A., Iñigo C., Calvo M.L., Escanero J.F. Variations in serum magnesium and hormonal levels during incremental exercise. Magnes. Res. 2014;27:155–164. doi: 10.1684/mrh.2014.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popović M., Matana A., Torlak V., Brdar D., Gunjača I., Boraska Perica V., Barbalić M., Kolčić I., Punda A., Polašek O., et al. The effect of multiple nutrients on plasma parathyroid hormone level in healthy individuals. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019;70:638–644. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2018.1551335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penido M.G.M.G., Alon U.S. Phosphate homeostasis and its role in bone health. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2012;27:2039–2048. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2175-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter P., Schipani E. The roles of parathyroid hormone and calcitonin in bone remodeling: Prospects for novel therapeutics. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 2006;6:59–76. doi: 10.2174/187153006776056666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khundmiri S.J., Murray R.D., Lederer E. PTH and Vitamin, D. Compr. Physiol. 2016;6:561–601. doi: 10.1002/CPHY.C140071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silver J., Levi R. Regulation of PTH synthesis and secretion relevant to the management of secondary hyperparathyroidism in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2005;67:S8–S12. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutiérrez O.M., Mannstadt M., Isakova T., Rauh-Hain J.A., Tamez H., Shah A., Smith K., Lee H., Thadhani R., Jüppner H., et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:584–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saki F., Kassaee S.R., Salehifar A., Omrani G.H.R. Interaction between serum FGF-23 and PTH in renal phosphate excretion, a case-control study in hypoparathyroid patients. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01826-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanske B., Razzaque M.S. Molecular interactions of FGF23 and PTH in phosphate regulation. Kidney Int. 2014;86:1072–1074. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ben-Dov I.Z., Galitzer H., Lavi-Moshayoff V., Goetz R., Kuro-o M., Mohammadi M., Sirkis R., Naveh-Many T., Silver J. The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. J. Clin. Investig. 2007;117:4003–4008. doi: 10.1172/JCI32409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jorde R., Saleh F., Figenschau Y., Kamycheva E., Haug E., Sundsfjord J. Serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels in smokers and non-smokers. The fifth Tromsø study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2005;152:39–45. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He J.L., Scragg R.K. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and blood pressure in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. Am. J. Hypertens. 2011;24:911–917. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2011.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paik J.M., Farwell W.R., Taylor E.N. Demographic, dietary, and serum factors and parathyroid hormone in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Osteoporos. Int. 2012;23:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1776-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Díaz-Gómez N.M., Mendoza C., González-González N.L., Barroso F., Jiménez-Sosa A., Domenech E., Clemente I., Barrios Y., Moya M. Maternal smoking and the vitamin D-parathyroid hormone system during the perinatal period. J. Pediatr. 2007;151:618–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Åkesson A., Bjellerup P., Lundh T., Lidfeldt J., Nerbrand C., Samsioe G., Skerfving S., Vahter M. Cadmium-induced effects on bone in a population-based study of women. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:830–834. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mousavi S.E., Amini H., Heydarpour P., Amini Chermahini F., Godderis L. Air pollution, environmental chemicals, and smoking may trigger vitamin D deficiency: Evidence and potential mechanisms. Environ. Int. 2019;122:67–90. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Al-Bashaireh A.M., Haddad L.G., Weaver M., Chengguo X., Kelly D.L., Yoon S. The effect of tobacco smoking on bone mass: An overview of pathophysiologic mechanisms. J. Osteoporos. 2018;2018:1206235. doi: 10.1155/2018/1206235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Need A.G., Kemp A., Giles N., Morris H.A., Horowitz M., Nordin B.E.C. Relationships between intestinal calcium absorption, serum vitamin D metabolites and smoking in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2002;13:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s198-002-8342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorde R., Stunes A.K., Kubiak J., Grimnes G., Thorsby P.M., Syversen U. Smoking and other determinants of bone turnover. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0225539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Babić Leko M., Gunjača I., Pleić N., Zemunik T. Environmental factors affecting thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroid hormone levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:6521. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabassian A.R., Nylen E.S., Giron A.E., Snider R.H., Cassidy M.M., Becker K.L. Evidence for cigarette smoke-induced calcitonin secretion from lungs of man and hamster. Life Sci. 1988;42:2323–2329. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90185-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan T.J., Chen L.P., Pan Y.L., Lu Y., Sun L.H., Zhao H.Y., Wang W.Q., Tao B., Liu J.M. An inverted U-shaped relationship between parathyroid hormone and body weight, body mass index, body fat. Endocrine. 2021;72:844–851. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02635-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wortsman J., Matsuoka L.Y., Chen T.C., Lu Z., Holick M.F. Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;72:690–693. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bolland M.J., Grey A.B., Ames R.W., Horne A.M., Gamble G.D., Reid I.R. Fat mass is an important predictor of parathyroid hormone levels in postmenopausal women. Bone. 2006;38:317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ni Z., Smogorzewski M., Massry S.G. Effects of parathyroid hormone on cytosolic calcium of rat adipocytes. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1837–1844. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7525254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarty M.F., Thomas C.A. PTH excess may promote weight gain by impeding catecholamine-induced lipolysis-implications for the impact of calcium, vitamin D, and alcohol on body weight. Med. Hypotheses. 2003;61:535–542. doi: 10.1016/S0306-9877(03)00227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rickard D.J., Wang F.L., Rodriguez-Rojas A.M., Wu Z., Trice W.J., Hoffman S.J., Votta B., Stroup G.B., Kumar S., Nuttall M.E. Intermittent treatment with parathyroid hormone (PTH) as well as a non-peptide small molecule agonist of the PTH1 receptor inhibits adipocyte differentiation in human bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2006;39:1361–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He Y., Liu R.X., Zhu M.T., Shen W.B., Xie J., Zhang Z.Y., Chen N., Shan C., Guo X.-z., Tao B., et al. The browning of white adipose tissue and body weight loss in primary hyperparathyroidism. EBioMedicine. 2019;40:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daniels G.H., Hegedüs L., Marso S.P., Nauck M.A., Zinman B., Bergenstal R.M., Mann J.F.E., Derving Karsbøl J., Moses A.C., Buse J.B., et al. LEADER 2: Baseline calcitonin in 9340 people with type 2 diabetes enrolled in the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of cardiovascular outcome Results (LEADER) trial: Preliminary observations. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2015;17:477–486. doi: 10.1111/dom.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathiesen D.S., Lund A., Vilsbøll T., Knop F.K., Bagger J.I. Amylin and calcitonin: Potential therapeutic strategies to reduce body weight and liver fat. Front. Endocrinol. 2021;11:1016. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.617400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calvo M.S., Kumar R., Heath H. Elevated secretion and action of serum parathyroid hormone in young adults consuming high phosphorus, low calcium diets assembled from common foods. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1988;66:823–829. doi: 10.1210/jcem-66-4-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kemi V.E., Kärkkäinen M.U.M., Rita H.J., Laaksonen M.M.L., Outila T.A., Lamberg-Allardt C.J.E. Low calcium:phosphorus ratio in habitual diets affects serum parathyroid hormone concentration and calcium metabolism in healthy women with adequate calcium intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2010;103:561–568. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lederer E. Regulation of serum phosphate. J. Physiol. 2014;592:3985–3995. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.273979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qin Z., Yang Q., Liao R., Su B. The association between dietary inflammatory index and parathyroid hormone in adults with/without chronic kidney disease. Front. Nutr. 2021;8:364. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.688369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kerstetter J.E., Svastisalee C.M., Caseria D.M., Mitnick M.A.E., Insogna K.L. A threshold for low-protein-diet-induced elevations in parathyroid hormone. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;72:168–173. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giannini S., Nobile M., Sartori L., Carbonare L.D., Ciuffreda M., Corrò P., D’Angelo A., Calò L., Crepaldi G. Acute effects of moderate dietary protein restriction in patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria and calcium nephrolithiasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999;69:267–271. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Josse A.R., Atkinson S.A., Tarnopolsky M.A., Phillips S.M. Diets higher in dairy foods and dietary protein support bone health during diet- and exercise-induced weight loss in overweight and obese premenopausal women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:251–260. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merrill R.M., Aldana S.G. Consequences of a plant-based diet with low dairy consumption on intake of bone-relevant nutrients. J. Women’s Health. 2009;18:691–698. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hansen T.H., Madsen M.T.B., Jørgensen N.R., Cohen A.S., Hansen T., Vestergaard H., Pedersen O., Allin K.H. Bone turnover, calcium homeostasis, and vitamin D status in Danish vegans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018;72:1046–1054. doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lamberg-Allardt C., Kärkkäinen M., Seppänen R., Biström H. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and secondary hyperparathyroidism in middle-aged white strict vegetarians. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;58:684–689. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.5.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu R., Huang X., Huang J., Li Y., Zhang C., Yin Y., Chen Z., Jin Y., Cai J., Cui F. Long- and short-term health effects of pesticide exposure: A cohort study from China. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0128766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Landin-Wilhelmsen K., Wilhelmsen L., Lappas G., Rosén T., Lindstedt G., Lundberg P.A., Wilske J., Bengtsson B.Å. Serum intact parathyroid hormone in a random population sample of men and women: Relationship to anthropometry, life-style factors, blood pressure, and vitamin D. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1995;56:104–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00296339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brot C., Jøorgensen N.R., Sørensen O.H. The influence of smoking on vitamin D status and calcium metabolism. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999;53:920–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paik J.M., Curhan G.C., Forman J.P., Taylor E.N. Determinants of plasma parathyroid hormone levels in young women. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2010;87:211–217. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9397-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parthemore J.G., Deftos L.J. Calcitonin secretion in normal human subjects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1978;47:184–188. doi: 10.1210/jcem-47-1-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pedrazzoni M., Ciotti G., Davoli L., Pioli G., Girasole G., Palummeri E., Passeri M. Meal-stimulated gastrin release and calcitonin secretion. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1989;12:409–412. doi: 10.1007/BF03350714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zayed A., Alzubaidi M., Atallah S., Momani M., Al-Delaimy W. Should food intake and circadian rhythm be considered when measuring serum calcitonin level? Endocr. Pract. 2013;19:620–626. doi: 10.4158/EP12358.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pointillart A., Garel J.M., Gueguen L., Colin C. Plasma calcitonin and parathyroid hormone levels in growing pigs on different diets. I.—High phosphorus diet. Ann. Biol. Anim. Biochim. Biophys. 1978;18:699–709. doi: 10.1051/rnd:19780407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deftos L.J., Miller M.M., Burton D.W. A high-fat diet increases calcitonin secretion in the rat. Bone Miner. 1989;5:303–308. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(89)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grundmann M., von Versen-Höynck F. Vitamin D—Roles in women’s reproductive health? Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2011;9:146. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moslehi N., Shab-Bidar S., Mirmiran P., Hosseinpanah F., Azizi F. Determinants of parathyroid hormone response to vitamin D supplementation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2015;114:1360–1374. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515003189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vaidya A., Curhan G.C., Paik J.M., Wang M., Taylor E.N. Physical activity and the risk of primary hyperparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;101:1590–1597. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engström A., Håkansson H., Skerfving S., Bjellerup P., Lidfeldt J., Lundh T., Samsioe G., Vahter M., Åkesson A. Retinol may counteract the negative effect of cadmium on bone. J. Nutr. 2011;141:2198–2203. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.146944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu W., Ridefelt P., Akerström G., Hellman P. Differentiation of human parathyroid cells in culture. J. Endocrinol. 2001;168:417–425. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1680417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacDonald P.N., Ritter C., Brown A.J., Slatopolsky E. Retinoic acid suppresses parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion and PreproPTH mRNA levels in bovine parathyroid cell culture. J. Clin. Investig. 1994;93:725–730. doi: 10.1172/JCI117026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ooms M.E., Roos J.C., Bezemer P.D., van der Vijgh W.J.F., Bouter L.M., Lips P. Prevention of bone loss by vitamin D supplementation in elderly women: A randomized double-blind trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1995;80:1052–1058. doi: 10.1210/JCEM.80.4.7714065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Naveh-Many T., Silver J. Regulation of calcitonin gene transcription by vitamin D metabolites in vivo in the rat. J. Clin. Investig. 1988;81:270–273. doi: 10.1172/JCI113305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saggese G., Federico G., Bertelloni S., Baroncelli G.I., Calisti L. Hypomagnesemia and the parathyroid hormone-vitamin D endocrine system in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Effects of magnesium administration. J. Pediatr. 1991;118:220–225. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80486-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sahota O., Mundey M.K., San P., Godber I.M., Hosking D.J. Vitamin D insufficiency and the blunted PTH response in established osteoporosis: The role of magnesium deficiency. Osteoporos. Int. 2006;17:1013–1021. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cheung M.M., DeLuccia R., Ramadoss R.K., Aljahdali A., Volpe S.L., Shewokis P.A., Sukumar D. Low dietary magnesium intake alters vitamin D-parathyroid hormone relationship in adults who are overweight or obese. Nutr. Res. 2019;69:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dai L.J., Ritchie G., Kerstan D., Kang H.S., Cole D.E.C., Quamme G.A. Magnesium transport in the renal distal convoluted tubule. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:51–84. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McGonigle R., Weston M., Keenan J., Jackson D., Parsons V. Effect of hypermagnesemia on circulating plasma parathyroid hormone in patients on regular hemodialysis therapy. Magnesium. 1984;3:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ohya M., Negi S., Sakaguchi T., Koiwa F., Ando R., Komatsu Y., Shinoda T., Inaguma D., Joki N., Yamaka T., et al. Significance of serum magnesium as an independent correlative factor on the parathyroid hormone level in uremic patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:3873–3878. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nishiyama S., Nakamura T., Higashi A., Matsuda I. Infusion of zinc inhibits serum calcitonin levels in patients with various zinc status. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1991;49:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02556114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Suzuki T., Kajita Y., Katsumata S.I., Matsuzaki H., Suzuki K. Zinc deficiency increases serum concentrations of parathyroid hormone through a decrease in serum calcium and induces bone fragility in rats. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2015;61:382–390. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.61.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alkan Baylan F., Bankir M., Acıbucu F., Kılınç M. Zinc copper levels in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Cumhur. Med. J. 2021;43:117–123. doi: 10.7197/cmj.884316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nielsen F.H., Milne D.B. A moderately high intake compared to a low intake of zinc depresses magnesium balance and alters indices of bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;58:703–710. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strause L., Saltman P., Smith K.T., Bracker M., Andon M.B. Spinal bone loss in postmenopausal women supplemented with calcium and trace minerals. J. Nutr. 1994;124:1060–1064. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.7.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Eaton Evans J., Mcilrath E.M., Jackson W.E., Mccartney H., Strain J.J. Copper supplementation and the maintenance of bone mineral density in middle-aged women. J. Trace Elem. Exp. Med. 1996;9:87–94. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-670X(1996)9:3<87::AID-JTRA1>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marrone J.A., Maddalozzo G.F., Branscum A.J., Hardin K., Cialdella-Kam L., Philbrick K.A., Breggia A.C., Rosen C.J., Turner R.T., Iwaniec U.T. Moderate alcohol intake lowers biochemical markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:974–979. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824ac071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Laitinen K., Lamberg-Allardt C., Tunninen R., Karonen S.-L., Tähtelä R., Ylikahri R., Välimäki M. Transient hypoparathyroidism during acute alcohol intoxication. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;324:721–727. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103143241103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rapuri P.B., Gallagher J.C., Balhorn K.E., Ryschon K.L. Smoking and bone metabolism in elderly women. Bone. 2000;27:429–436. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ilich J.Z., Brownbill R.A., Tamborini L., Crncevic-Orlic Z. To drink or not to drink: How are alcohol, caffeine and past smoking related to bone mineral density in elderly women? J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2002;21:536–544. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rico H. Alcohol and bone disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 1990;25:345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Vantyghem M.C., Danel T., Marcelli-Tourvieille S., Moriau J., Leclerc L., Cardot-Bauters C., Docao C., Carnaille B., Wemeau J.L., D’Herbomez M. Calcitonin levels do not decrease with weaning in chronic alcoholism. Thyroid. 2007;17:213–217. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schuster R., Koopmann A., Grosshans M., Reinhard I., Spanagel R., Kiefer F. Association of plasma calcium concentrations with alcohol craving: New data on potential pathways. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ilias I., Paparrigopoulos T., Tzavellas E., Karaiskos D., Meristoudis G., Liappas A., Liappas I. Inpatient alcohol detoxification and plasma calcitonin (with original findings) Hell. J. Nucl. Med. 2011;14:177–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kalafateli A.L., Vallöf D., Colombo G., Lorrai I., Maccioni P., Jerlhag E. An amylin analogue attenuates alcohol-related behaviours in various animal models of alcohol use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1093–1102. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0323-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kalafateli A.L., Satir T.M., Vallöf D., Zetterberg H., Jerlhag E. An amylin and calcitonin receptor agonist modulates alcohol behaviors by acting on reward-related areas in the brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2021;200:101969. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ylli D., Wartofsky L. Can we link thyroid status, energy expenditure, and body composition to management of subclinical thyroid dysfunction? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019;104:209–212. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bouassida A., Latiri I., Bouassida S., Zalleg D., Zaouali M., Feki Y., Gharbi N., Zbidi A., Tabka Z. Parathyroid hormone and physical exercise: A brief review. J. Sport. Sci. Med. 2006;5:367. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nichols J.F., Palmer J.E., Levy S.S. Low bone mineral density in highly trained male master cyclists. Osteoporos. Int. 2003;14:644–649. doi: 10.1007/S00198-003-1418-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hind K., Truscott J.G., Evans J.A. Low lumbar spine bone mineral density in both male and female endurance runners. Bone. 2006;39:880–885. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lombardi G., Ziemann E., Banfi G., Corbetta S. Physical activity-dependent regulation of parathyroid hormone and calcium-phosphorous metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:5388. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shea K.L., Barry D.W., Sherk V.D., Hansen K.C., Wolfe P., Kohrt W.M. Calcium supplementation and parathyroid hormone response to vigorous walking in postmenopausal women. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2014;46:2007–2013. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Blum J.W., Fischer J.A., Hunziker W.H., Binswanger U., Picotti G.B., Da Prada M., Guillebeau A. Parathyroid hormone responses to catecholamines and to changes of extracellular calcium in cows. J. Clin. Investig. 1978;61:1113–1122. doi: 10.1172/JCI109026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.López I., Aguilera-Tejero E., Estepa J.C., Rodríguez M., Felsenfeld A.J. Role of acidosis-induced increases in calcium on PTH secretion in acute metabolic and respiratory acidosis in the dog. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;286:E780–E785. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00473.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lin L.L., Hsieh S.S. Effects of strength and endurance exercise on calcium-regulating hormones between different levels of physical activity. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2005;5:267–275. doi: 10.1142/S0219519405001461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhao C., Hou H., Chen Y., Lv K. Effect of aerobic exercise and raloxifene combination therapy on senileosteoporosis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016;28:1791. doi: 10.1589/jpts.28.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Henderson S.A., Graham H.K., Mollan R.A.B., Riddoch C., Sheridan B., Johnston H. Calcium homeostasis and exercise. Int. Orthop. 1989;13:69–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00266727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.O’Neill M.E., Wilkinson M., Robinson B.G., McDowall D.B., Cooper K.A., Mihailidou A.S., Frewin D.B., Clifton-Bligh P., Hunyor S.N. The effect of exercise on circulating immunoreactive calcitonin in men. Horm. Metab. Res. 1990;22:546–550. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Klausen T., Breum L., Sørensen H.A., Schifter S., Sonne B. Plasma levels of parathyroid hormone, vitamin D, calcitonin, and calcium in association with endurance exercise. Calcif. Tissue Int. 1993;52:205–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00298719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Soria M., Anson M., Escanero J.F. Correlation analysis of exercise-induced changes in plasma trace element and hormone levels during incremental exercise in well-trained athletes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016;170:55–64. doi: 10.1007/s12011-015-0466-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Çetin Kargin N., Marakoglu K., Unlu A., Kebapcilar L., Korucu N. Comparison of bone turnover markers between male smoker and non-smoker. Acta Med. Mediterr. 2016;32:317–323. doi: 10.19193/0393-6384_2016_2_47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Fujiyoshi A., Polgreen L.E., Gross M.D., Reis J.P., Sidney S., Jacobs D.R. Smoking habits and parathyroid hormone concentrations in young adults: The CARDIA study. Bone Rep. 2016;5:104. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Andersen S., Noahsen P., Rex K.F., Fleischer I., Albertsen N., Jorgensen M.E., Schæbel L.K., Laursen M.B. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, calcium and parathyroid hormone levels in Native and European populations in Greenland. Br. J. Nutr. 2018;119:391–397. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517003944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen W.R., Sha Y., Chen Y.D., Shi Y., Yin D.W., Wang H. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and serum lipid profiles in a middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. Endocr. Pract. 2014;20:556–565. doi: 10.4158/EP13329.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]