Summary

Childhood, adolescent and young adult (CAYA) cancer survivors are at increased risk of reduced bone mineral density (BMD). Clinical practice surveillance guidelines are important for timely diagnosis and treatment of these survivors, which could improve BMD parameters and prevent fragility fractures. Discordances across current late-effects guidelines necessitated international harmonization of recommendations for BMD surveillance. The International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group therefore established a panel of 36 experts from 10 countries, representing a range of relevant medical specialties. The evidence of risk factors for (very) low BMD and fractures, surveillance modality, timing of BMD surveillance, and treatment of (very) low BMD were evaluated and critically appraised, and harmonized recommendations for CAYA cancer survivors were formulated. We graded the recommendations based on the quality of evidence and balance between potential benefits and harms. BMD surveillance is recommended for survivors treated with cranial or craniospinal radiotherapy, and is reasonable for survivors treated with total body irradiation. Due to insufficient evidence, no recommendation can be formulated for or against BMD surveillance for survivors treated with corticosteroids. This surveillance decision should be made by the survivor and healthcare provider together, after careful consideration of the potential harms and benefits and additional risk factors. We recommend to perform BMD surveillance using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry at entry into long-term follow-up, and if normal (Z-score >−1), repeat at 25 years of age. Between these measurements and thereafter, surveillance should be performed as clinically indicated. These recommendations facilitate evidence-based care for CAYA cancer survivors internationally.

Introduction

The survival of children, adolescents and young adults (CAYAs) with cancer has greatly improved over recent decades, with current 5-year overall survival rates approximating 80% in high-income countries.1,2 However, CAYA cancer survivors often experience long-term side effects.3,4 Previous studies suggest an increased proportion of survivors with low (Z-score ≤−1) and very low (Z-score ≤−2) bone mineral density (BMD) compared to the normal population,5,6 as well as an increased fracture rate.7,8 BMD deficits may occur due to the cancer itself, its treatment, or consequences such as endocrine defects (e.g. hypogonadism, growth hormone deficiency [GHD]), malnutrition or malabsorption, and sedentary lifestyles.9–11 These factors may lead to impaired bone accrual, resulting in a lower peak bone mass (PBM), usually achieved between the age of 20–30 years.12,13 Because PBM predicts osteoporosis in adulthood and affects the age of osteoporosis onset,14 it is hypothesized that as the current CAYA cancer survivor population ages, more survivors may experience fragility fractures at relatively young ages.15 These fragility fractures may cause substantial morbidity such as reduced mobility, chronic pain, and difficulty with activities of daily living.16

General population studies have shown that early detection and treatment of (very) low BMD may overcome suboptimal PBM acquisition and prevent fractures.17,18 Therefore, several North American and European groups have implemented BMD surveillance in their clinical practice survivorship guidelines.19–22 However, these guidelines have not systematically analyzed the literature. Thus, definitions of high-risk groups, timing of surveillance, and treatment recommendations vary considerably, which impedes effective international implementation and adherence. To overcome such limitations, the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group (IGHG) was established.23 This collaborative endeavor aims to establish a common vision and integrated strategy for surveillance of chronic health problems in CAYA cancer survivors. This IGHG report summarizes available evidence and provides the first harmonized recommendations for BMD surveillance among CAYA cancer survivors.

Methods

Guideline panel

The guideline panel was composed of 36 experts from 10 countries, representing several pediatric oncology and other related societies, as well as a broad range of medical specialties (Appendix pp. 2–3). Three dedicated working groups addressed the following topics (Appendix p. 4): 1) who needs BMD surveillance?; 2a) what surveillance modality should be used?; 2b) when should surveillance be initiated and at what frequency should it be performed?; and 3) what should be done when abnormalities are identified? Details on the IGHG methodology have been previously reported (Appendix p. 5).23

Scope and definitions

This guideline provides BMD surveillance recommendations for CAYA cancer survivors diagnosed with cancer up to 25 years of age, who are at least two years after completion of treatment, regardless of current age. Definitions of the main potential osteotoxic treatments and outcomes can be found in Appendix p. 6. We analyzed risk factors for very low BMD (including studies with a Z-score ≤−2 as outcome), low BMD (Z-score ≤−1 and ≤−2), lower BMD Z-score (continuous), and for fractures (all types). A Z-score indicates the number of standard deviations that BMD differs from age- and sex-matched normative values, whereas a T-score compares BMD with the healthy young adult mean (PBM). Z-scores (and not T-scores) were used as all included studies were performed in CAYAs, who may not have yet achieved PBM.24,25 Although we mainly focused on risk factors for very low BMD, we also included studies using a BMD Z-score threshold ≤−1. This threshold was considered relevant in the context of CAYA BMD surveillance, because Z-scores ≤−1 but >−2 may predispose to developing very low BMD as survivors age, and because adult studies showed a 2–3 times increased fracture risk for every one standard deviation reduction in BMD.26 All skeletal sites were analyzed together, because risks of (very) low BMD for different skeletal sites have similar implications for BMD surveillance.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Initially, the panel evaluated concordances and discordances between the online available Children’s Oncology Group, Dutch Childhood Oncology Group, UK Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group, and Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network survivorship guidelines.19–22 Clinical questions were then formulated for all discordant areas. For concordant areas, clinical questions were drafted if there was any uncertainty about sufficient literature support or if more details were needed.

We searched English literature published between January 1, 1990 and May 12, 2021 using the MEDLINE (PubMed) database to identify relevant evidence (Appendix p. 13). Two independent reviewers determined whether the identified articles met pre-determined inclusion criteria (Appendix p. 15). Subsequently, all guideline members were contacted to determine if additional evidence was available. Cross-references identified during the review procedure that had not been initially identified were added if relevant.

We summarized information from included studies using evidence tables, and generated a summary of the total body of evidence per clinical question. The quality of the evidence was graded using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology (Appendix pp. 16–20).27 If evidence in CAYA cancer survivors was not available or insufficient to answer a clinical question, we searched for recommendations in clinical practice guidelines on osteoporosis or low BMD in closely related populations (Appendix p. 14). These recommendations were extrapolated to support expert opinion after careful consideration.

Translating evidence into recommendations

We used the GRADE Evidence-to-Decision framework to formulate recommendations.28 Our harmonized recommendations for BMD surveillance were based on evidence, expert opinions, cost-benefit considerations, the balance between potential benefits and harms of surveillance, and the need to maintain flexibility of application across different health-care systems. According to the IGHG methodology, only treatment-related risk groups were considered for BMD surveillance. Decisions were made through group discussion and consensus. The strength of the recommendations were graded according to published evidence-based methods (Appendix p. 21).27,29 Finally, two independent experts in the field (CS and J-MK) and six survivor representatives (DC, LG, MB, TC, MS, and ZT) had the opportunity to provide input on the harmonized recommendations.

Results

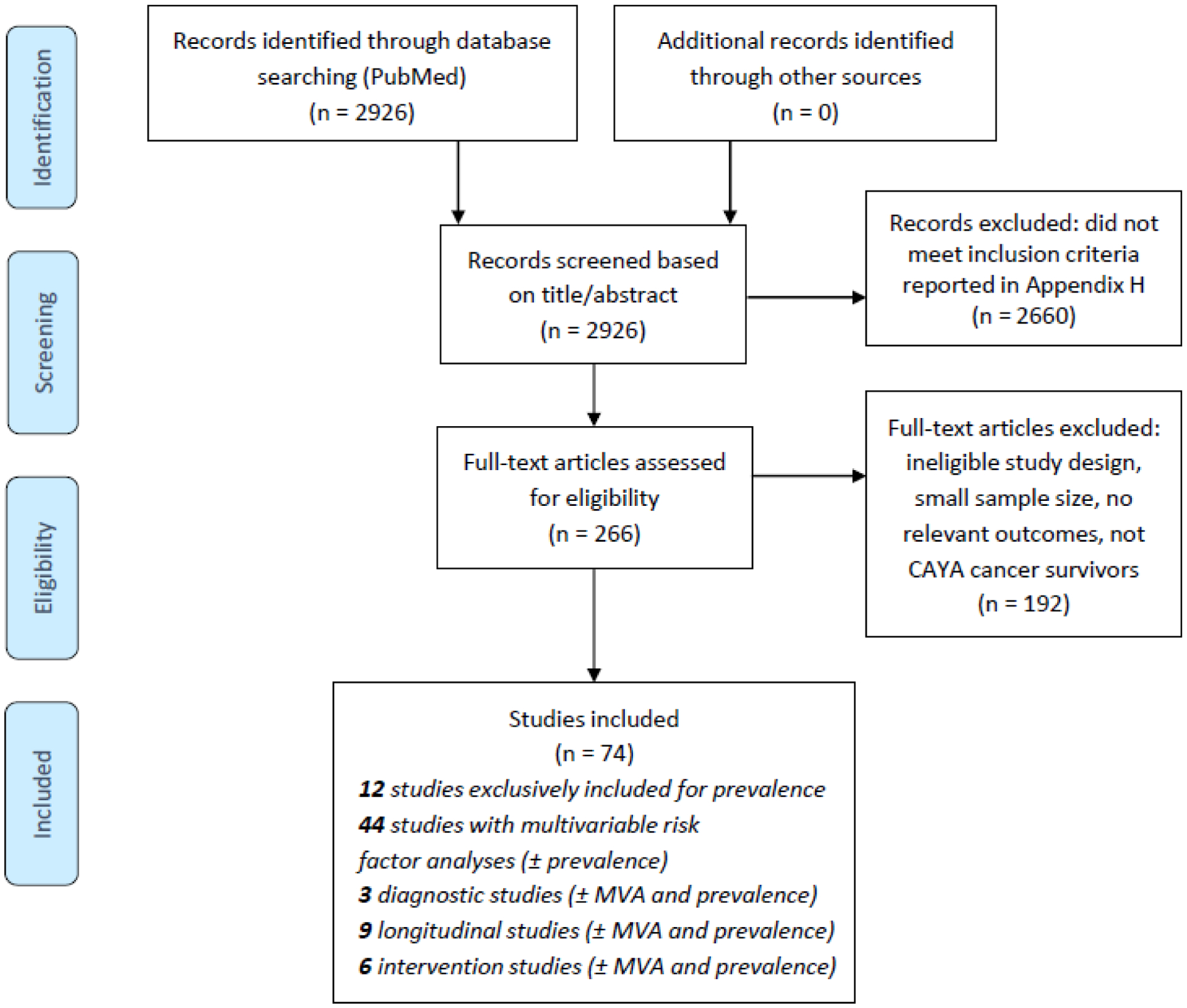

Appendix pp. 7–8 shows the evaluation of concordant and discordant areas between the existing survivorship guidelines. Because the panel felt that both concordant and discordant areas required systematic, in-depth review of the evidence, clinical questions were drafted for all areas (Appendix pp. 9–12). Seventy-four studies in CAYA cancer survivors (Figure 1) and three clinical practice guidelines in related populations (two childhood cancer guidelines and one general pediatric guideline, Appendix pp. 22–26) were included. Evidence tables and summary of findings tables are presented in Appendix pp. 27–218 and pp. 219–365.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of selected studies.

Abbreviations: CAYA=childhood, adolescent, and young adult; MVA=multivariable analyses.

Risk of reduced BMD and fractures

CAYA cancer survivors are at increased risk of low BMD (moderate-quality evidence),6,7,9–11,30–70 very low BMD (moderate-quality evidence),6,7,9,10,30–37,39–44,47–55,58–62,64,66–71 and lower BMD Z-scores (moderate-quality evidence) after a follow-up period ranging from 2∙7 to 27∙2 years.30,31,33,38,39,41,43,44,50,52–55,58,60,61,64,66,67,69–79 We found an increased risk of fractures in survivors versus controls (very low-quality evidence) after a follow-up ranging from 9∙1 to 22∙7 years.7,8,80 (See Appendix pp. 219–237 for details on prevalence of (very) low BMD and incidence of fractures). Clinical fractures are significantly associated with low BMD in survivors (low-quality evidence),58,68 but not with lower versus higher BMD Z-score as a continuum (moderate-quality evidence).81 It is unknown whether (very) low BMD during therapy or previous fractures lead to an increased risk of reduced BMD and fractures at two or more years after treatment cessation (no studies).

Risk factors for very low BMD

Identified risk factors associated with very low BMD include cranial or craniospinal radiotherapy (C[S]RT) (high-quality evidence),6,54 abdominal/pelvic irradiation (moderate-quality evidence, one study),6 hypogonadism (moderate-quality evidence),10,54 GHD (low-quality evidence),10,54,82,83 low body mass index (BMI) (high-quality evidence),6,54,69 and male sex (moderate-quality evidence).6,41,54 For the remaining potential risk factors, no increased risk of very low BMD was found, or no or only very low-quality evidence was available (Table 1).

Table 1.

Conclusions and quality of the evidence for bone mineral density surveillance in CAYA cancer survivors.

| Who needs bone mineral density surveillance? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk and risk factors for low BMD, very low BMD, lower BMD Z-score, and fractures in CAYA cancer survivors diagnosed up to 25 years of age | ||||

| Very low BMD (Z-score ≤−2) | Low BMD (Z-score ≤−1 and ≤−2) | Lower BMD Z-score (continuous) | Fractures (all types) | |

| Risk | ||||

| Risk | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,7,9,10,30–37,39–44,47–55,58–62,64,66–71 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,7,9–11,30–70 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE30,31,33,38,39,41,43,44,50,52–55,58,60,61,64,66,67,69–79 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW7,8,80 |

| Risk after low BMD/fracture | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Host factors | ||||

| Male sex | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,41,54 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH6,9,64,65,68,32,40–42,45,51,54,56 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9,35,41,43,44,49,53,67,74,76 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE41,58,81 |

| Age at diagnosis | =⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH6,54,69 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW6,9,54,56,64,68,69 | ⇳ ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW9,35,44,53,67,70,72 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW80,81 |

| White race | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW41 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE40,41,51,65,68 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE41,43 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW80 |

| Low BMI/weight/lean mass | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH6,54,69 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH6,9,40,42,51,54,56,64,68,69 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE9,33,35,36,43,52,53,72,74,126 | No studies |

| Certain SNPs | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW66 | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW66 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9,73,74,78 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW127 |

| Family history of OP/# | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Treatment factors | ||||

| Corticosteroids (y/n) | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,54 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,9,51,54,68 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW9,38,44 | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW80,127 |

| Higher corticosteroid dose | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW69 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE32,46,69 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE41,67,70,72,74 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW81 |

| DEXA vs. PRED | No studies | No studies | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW79 | No studies |

| Methotrexate (y/n) | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,54 | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,9,54,68 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9,38 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW80,81 |

| Higher methotrexate dose | No studies | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW32 | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW70 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW127 |

| Ifosfamide (y/n) | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6 | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,9 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9 | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW80 |

| Higher ifosfamide dose | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Cyclophosphamide (y/n) | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6 | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,9,68 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9 | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW80 |

| Higher cyclo dose | No studies | No studies | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW68,70 | No studies |

| Cisplatin (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Higher cisplatin dose | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| 6-MP (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Higher 6-MP dose | No studies | No studies | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW70 | No studies |

| Cyclosporine (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Higher cyclosporine dose | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| TKIs (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| TKI dose | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Tacrolimus (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Higher tacrolimus dose | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| C(S)RT (y/n) | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH6,54 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH6,9,32,38,51,54,64,68 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9,33,38,50,52,67,72,79 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW81 |

| Higher C(S)RT dose | No studies | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW32 | No studies | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW127 |

| HSCT (y/n) | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW54 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9,54 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW9,44 | No studies |

| TBI (y/n) | No studies | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH9,45,54,64,65 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9,44,67,75 | No studies |

| Higher TBI dose | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Abdominal/pelvic RT (y/n) | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW6,9 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9 | =⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW80 |

| Higher abd./pelvic RT dose | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Medical conditions | ||||

| GHD (y/n) | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW10,54,82,83 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE10,54,61,68,82,83 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW67,75 | No studies |

| Hypogonadism (y/n) | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE10,54 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW10,38,51,54,61,68,82,84 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW38,67 | No studies |

| Vitamin D deficiency (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Hyperthyroidism (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Endocrine dysfunction* (y/n) | No studies | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW62 | No studies | No studies |

| Health behaviors | ||||

| Inadequate vit. D intake (y/n) | No studies | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE51 | No studies | No studies |

| Vitamin D deficiency (y/n) | No studies | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW65 | No studies | No studies |

| Inadequate Ca intake (y/n) | No studies | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE51 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW33 | No studies |

| Inadequate vit. B intake (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Lack of exercise (y/n) | No studies | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE11,40,51,56 | ⬆⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW39,63 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW11,80 |

| Current/prior smoking (y/n) | =⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6 | ⬆⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE6,9,56,61 | =⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW9 | ⬆⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW80 |

| Alcohol consumption (y/n) | No studies | ⇳ ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW61 | No studies | No studies |

| Carbonated beverages (y/n) | No studies | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| What surveillance modality should be used? | ||||

| Diagnostic value to detect (very) low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors diagnosed up to 25 years of age | ||||

| Variable | Outcome | Quality of evidence | ||

| Diagnostic value of QCT vs. DXA | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Correlation between QCT and DXA derived BM(A)D and BMD Z-scores | Significant (r 0.33–0.64) | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW41,85 | ||

| Diagnostic value of QUS vs. DXA | Moderate | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW86 | ||

| Diagnostic value of QUS vs. QCT | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Diagnostic value of pQCT vs. QCT | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Added value of QUS to QCT and DXA in predicting fractures | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Location of BMD measurement (lumbar spine, total body and/or hip) that should be evaluated | Unknown | No studies | ||

| When should surveillance be initiated and at what frequency should it be performed? | ||||

| Risk over time of (very) low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors diagnosed up to 25 years of age | ||||

| Variable | Outcome | Quality of evidence | ||

| Course of BMD Z-scores over time from 2 years until at least 10 years since end of cancer treatment | Increase | ⊕⊕⊕⊖ MODERATE32,40,49,64,71,87–90 | ||

| Latency time of low BMD and fractures | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Risk of fractures for low BMD vs. normal BMD | Increased | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW58,68 | ||

| Risk of fractures for lower BMD vs. higher BMD | Not significant | ⊕⊕⊖⊖ LOW81 | ||

| What should be done when abnormalities are identified? | ||||

| Use of medical interventions to improve BMD in CAYA cancer survivors diagnosed up to 25 years of age | ||||

| Variable | Outcome | Quality of evidence | ||

| Effect of growth hormone replacement therapy in GH deficient survivors | Significant | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW91–93 | ||

| Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation | Not significant | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW43 | ||

| Effect of weight-bearing physical exercise | Not significant | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW94 | ||

| Effect of twice daily treatment with a vibrating plate | Not significant (intention-to-treat analysis) Significant (per-protocol analysis) | ⊕⊖⊖⊖ VERY LOW95 | ||

| Effect of bisphosphonates | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Effect of PTH | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Effect of Denosumab | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Effect of vitamin B12 supplementation | Unknown | No studies | ||

| Effect of sex hormone replacement therapy | Unknown | No studies | ||

GHD, hypogonadism or thyroid dysfunction.

⬆ indicates an increased risk, = indicates no significant effect, and ⇳ indicates conflicting evidence.

Abbreviations: BMD=bone mineral density; BMI=body mass index; CAYA=childhood, adolescent, and young adult; CRT=cranial irradiation; CSRT=craniospinal irradiation; DEXA=dexamethasone; DXA=dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; GH=growth hormone; GHD=growth hormone deficiency; HSCT=hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; OP=osteoporosis; PRED=prednisone; PTH=parathyroid hormone; pQCT=peripheral quantitative computed tomography; QCT=quantitative computed tomography; QUS=quantitative ultrasound; RT=radiotherapy; SNP=single nucleotide polymorphism; TBI=total body irradiation; TKI=tyrosine kinase inhibitors; y/n=yes/no; 6-MP=6-mercaptopurine; #=fracture.

Treatment-related risk factors for low BMD

The main treatment-related risk factors for low BMD include C(S)RT (high-quality evidence),6,9,32,38,51,54,64,68 total body irradiation (TBI) (high-quality evidence),9,45,54,64,65 and corticosteroids (administered as anti-cancer treatment, moderate-quality evidence)6,9,51,54,68. Survivors treated with higher doses of C(S)RT (low-quality evidence)32 and corticosteroids (moderate-quality evidence)32,46,69 are at greater risk of low BMD. A dose threshold for increased risk of low BMD could not be determined from available literature for C(S)RT or corticosteroids. The effect of higher total body irradiation doses is unclear, as no studies investigated this. Furthermore, it is unknown whether administering dexamethasone leads to higher risk of low BMD than prednisone (no studies). However, very low-quality evidence for a greater risk of dexamethasone versus prednisone on lower BMD Z-scores as a continuum was found.79 Survivors treated with abdominal/pelvic irradiation6,9 also have increased risk of low BMD (low-quality evidence). No significant associations between low BMD and treatment with methotrexate (moderate-quality evidence),6,9,54,68 ifosfamide (moderate-quality evidence),6,9 cyclophosphamide (moderate-quality evidence),6,9,68 and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation without TBI (low-quality evidence)9,54 were found. Finally, the panel identified no studies that assessed the independent effect of cisplatin, 6-mercaptopurine, cyclosporine, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or tacrolimus on low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors.

Other risk factors for low BMD

Survivors with GHD (moderate-quality evidence)10,54,61,68,82,83 or hypogonadism (low-quality evidence)10,38,51,54,61,68,82,84 have increased risk of low BMD. In more than half of the included studies, either some of the survivors received hormone replacement therapy or the percentage of treated survivors was not reported (Appendix pp. 321–323 and 326–328). Survivor characteristics and health behaviors associated with low BMD include low BMI (high-quality evidence),6,9,40,42,51,54,56,64,68,69 male sex (high-quality evidence),6,9,32,40–42,45,51,54,56,64,65,68 White race (moderate-quality evidence),40,41,51,65,68 lack of physical activity (moderate-quality evidence),11,40,51,56 and current or prior smoking (moderate-quality evidence).6,9,56,61 We found conflicting evidence for the association between alcohol consumption61 and low BMD. No significant effect of age at cancer diagnosis6,9,54,56,64,68,69 or inadequate dietary vitamin D and calcium intake (moderate-quality evidence, one study)51 on the risk of low BMD was observed. However, we found an increased risk of low BMD for survivors with biochemical vitamin D deficiency (25OHD levels <20 ng/ml) (low-quality evidence).65 None of the included studies assessed the risk of low BMD in relation to biochemical vitamin B deficiency, hyperthyroidism, or consumption of carbonated beverages.

Risk factors for fractures

Risk factors for fractures in CAYA cancer survivors include male sex (moderate-quality evidence)41,58,81 and higher doses corticosteroids (low-quality evidence)81 (Table 1). When evidence about other risk factors for fractures was available, it was of very low-quality or no increased risk was identified.

Diagnostic value of BMD surveillance modalities

No studies investigating the diagnostic value of quantitative computed tomography (QCT) compared to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in CAYA cancer survivors were identified. However, two studies showed a significant correlation between QCT and DXA-derived BMD parameters in this population (low-quality evidence).41,85 Very low-quality evidence indicated that the diagnostic value of quantitative ultrasound (QUS) compared to DXA was moderate.86 No studies addressing the diagnostic value of QUS and peripheral QCT (pQCT) versus QCT, as well as the added value of QUS to QCT and DXA in predicting fractures in survivors, were identified. Also, the optimal site of BMD measurement has not been evaluated (no studies).

Risk of (very) low BMD over time

The average time from diagnosis to the time of (very) low BMD development in survivors is unknown (no studies). Moderate-quality evidence suggests that BMD Z-scores increase from two years until at least ten years from completion of cancer treatment in CAYA cancer survivors.32,40,49,64,71,87–90

Interventions to maintain or increase BMD

Limited evidence for efficacy of interventions to remediate (very) low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors was identified. A significant effect of growth hormone replacement therapy on BMD in survivors with GHD was reported (very low-quality evidence).91–93 However, no significant effect of weight-bearing physical exercise (low-quality evidence)94 or calcium and vitamin D supplementation (very low-quality evidence)43 on BMD was found. In addition, one study showed no significant effect of twice daily treatment with a vibrating plate on total body BMD Z-score in survivors in an intention-to-treat analysis, although there was significant improvement of tibial trabecular bone content among participants completing at least 70% of prescribed sessions.95 The effects of bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone, denosumab, vitamin B12 supplementation, and sex steroid replacement therapy were not studied in any of the included reports.

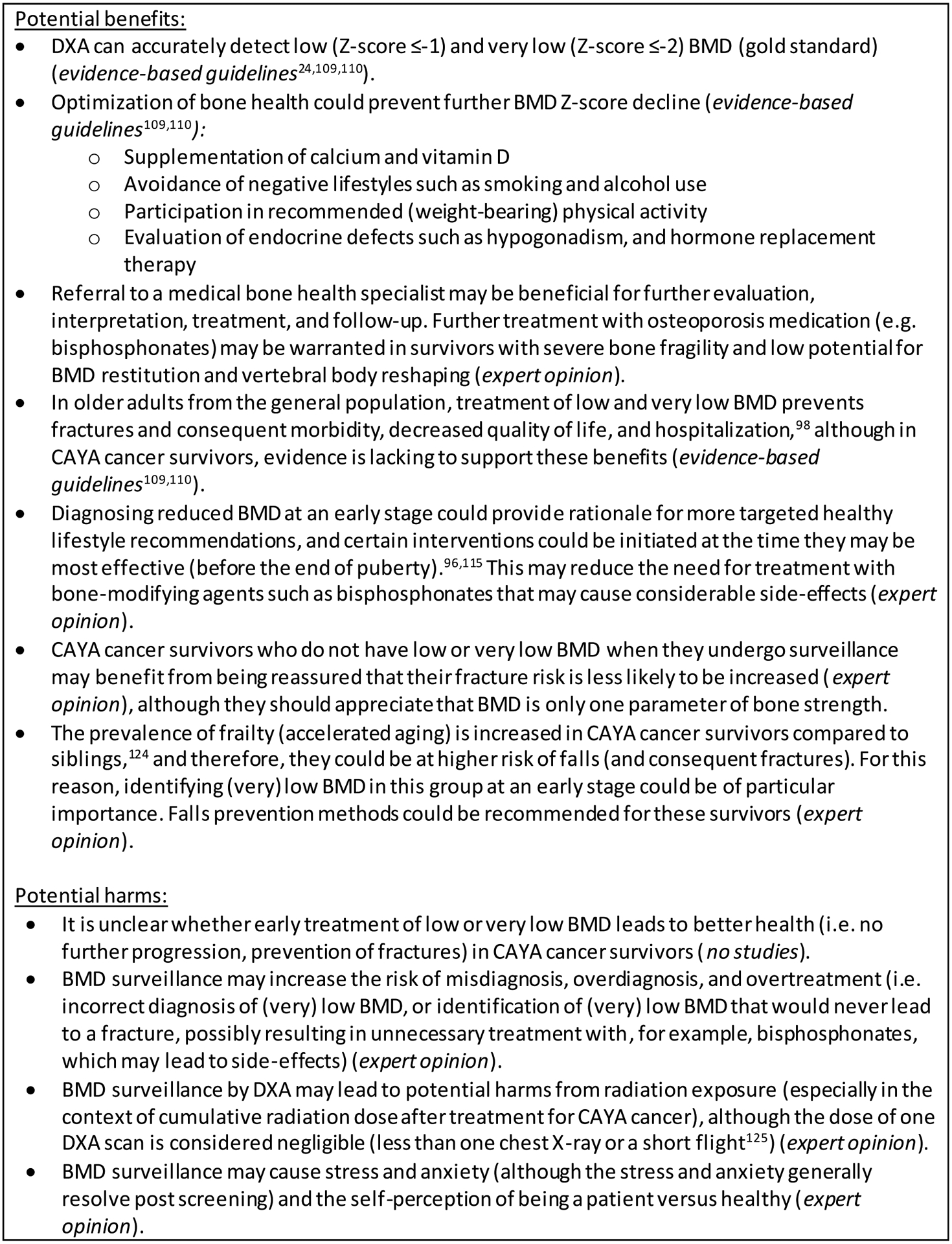

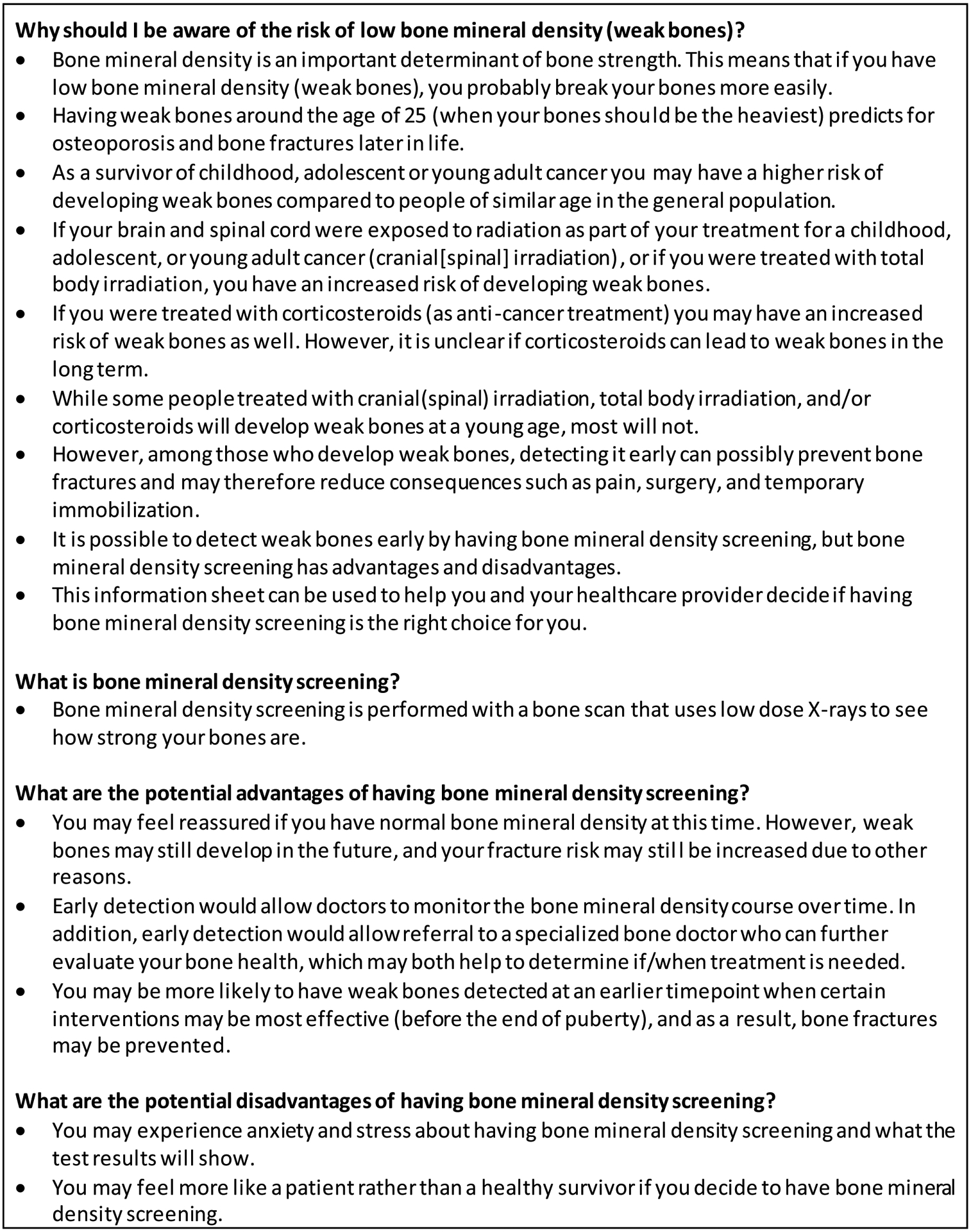

Potential benefits and harms of BMD surveillance

The potential benefits and harms of BMD surveillance are shown in Figure 2. Most importantly, it is unclear whether early treatment of BMD deficits leads to better skeletal health (i.e. no further progression, prevention of fractures) in CAYA cancer survivors, which is a prerequisite for BMD surveillance. However, in healthy children, weight-bearing physical exercise and calcium and vitamin D supplementation (in case of deficit) have been shown to maintain or enhance BMD.96,97 Diagnosing (very) low BMD at an early stage among at-risk survivors could provide rationale for targeted healthy lifestyle recommendations. Furthermore, in older adults from the general population, treatment of (very) low BMD prevents fractures and consequent morbidity, decreased quality of life, and hospitalization.98

Figure 2.

Potential benefits and harms of bone mineral density surveillance for childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors.

Abbreviations: BMD=bone mineral density; CAYA=childhood, adolescent and young adult; DXA=dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

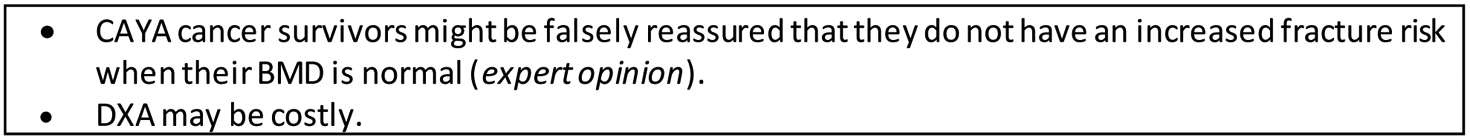

Translating evidence into recommendations

Who needs BMD surveillance?

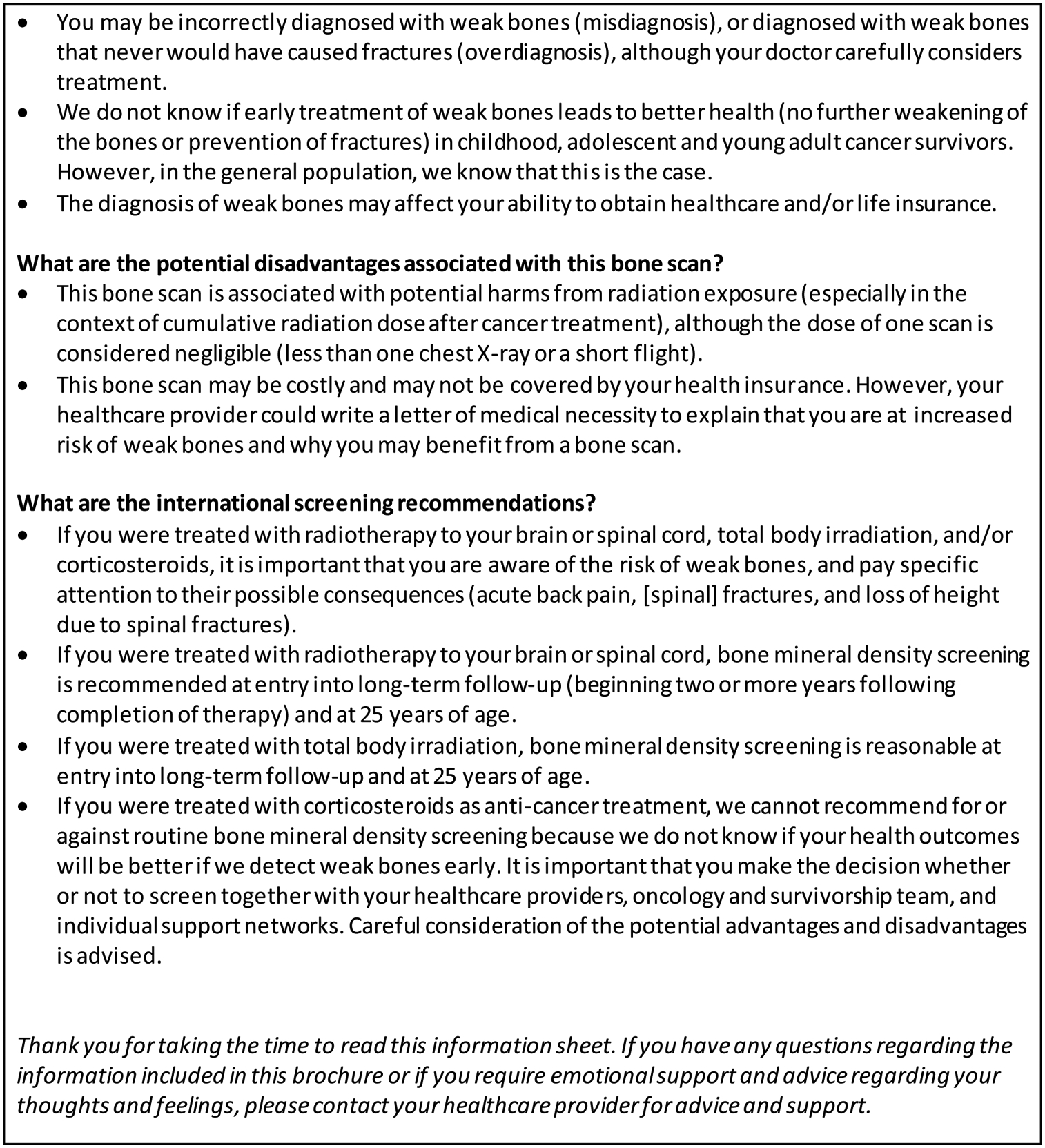

The panel strongly recommends that CAYA cancer survivors and their healthcare providers should be aware of the risk of (very) low BMD and pay specific attention to possible consequences (e.g. acute and chronic back pain, low-trauma vertebral fractures [VF] and non-VF, and loss of height due to VF) after treatment with C(S)RT (high-quality evidence for very low BMD), TBI (high-quality evidence for low BMD), or corticosteroids (moderate-quality evidence for low BMD) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Harmonized recommendations for bone mineral density surveillance for CAYA cancer survivors.

Abbreviations: BMD=bone mineral density; BMI=body mass index; CAYA=childhood, adolescent and young adult; DXA=dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; LTFU=long-term follow-up; PBM=peak bone mass; TBI=total body irradiation.

1As in the general population (except for sex; female sex in the general population); 2A medical bone health specialist is defined as any specialist who is caring for BMD deficits in CAYA cancer survivors, such as an endocrinologist (most settings), internist, pediatrician, rheumatologist, family physician, or general practitioner, depending on country and setting; 3The WHO global recommendation on physical activity for health for adults is 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity (or equivalent) per week, measured as a composite of physical activity undertaken across multiple domains: for work (paid and unpaid, including domestic work); for travel (walking and cycling); and for recreation (including sports). For adolescents, the recommendation is 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity daily; 4Insufficient evidence to determine if early detection of low BMD after treatment with corticosteroids reduces morbidity in CAYA cancer survivors, and whether the risk of very low BMD is increased in the long-term; 5Survivors treated with C(S)RT (high-quality evidence), TBI (high-quality evidence), or corticosteroids (moderate-quality evidence); 6Target 25OHD levels should be >20 ng/ml.

Green representing a strong recommendation to do with a low degree of uncertainty; Yellow representing a moderate recommendation to do with a higher degree of uncertainty; Red representing a recommendation not to do.

Overall, the balance of desirable and undesirable anticipated effects of surveillance varies depending on the risk of (very) low BMD (Appendix pp. 366–373). In CAYA cancer survivors treated with C(S)RT (high-quality evidence for very low BMD), the panel was convinced that the potential benefits of BMD surveillance clearly outweigh the potential harms. For these survivors, we strongly recommend BMD surveillance. Mechanisms through which C(S)RT could cause very low BMD include hypogonadism, GHD, low BMI or lean mass, and obesity leading to diabetes.10,99 These mechanisms may also apply to survivors treated with TBI, but evidence is more limited (high-quality evidence for low BMD, but no studies for very low BMD). Therefore, we made a moderate recommendation for BMD surveillance after treatment with TBI. A dose threshold for C(S)RT and TBI could not be determined, but the risk of (very) low BMD is likely associated with the risk of hypothalamic-pituitary axis, ovarian, or testicular injury after radiotherapy, and with age of radiotherapy administration. In addition, radiotherapy may impact bones directly and increase fracture risk, but this may not directly result from low BMD but from a perturbation in bone (re)modeling.100

It is well-known that corticosteroids (administered as anti-cancer treatment) have a detrimental effect on bone (especially trabecular bone) during its administration, resulting in an increased risk of low-trauma VF and non-VF.101 However, for survivors with and without bone issues during therapy, the effect of corticosteroids on BMD more than two years after the last exposure is unclear, as longitudinal studies from corticosteroid initiation until many years after its termination are lacking. We found an increased risk of low BMD after corticosteroid treatment (moderate-quality evidence), but not of very low BMD (moderate-quality evidence) and fractures (very low-quality evidence). An increased risk of low BMD (moderate-quality evidence) and fractures (low-quality evidence) after higher doses corticosteroids was observed. The included longitudinal studies (mostly involving survivors treated with steroids) showed that BMD Z-scores increased after treatment cessation.32,40,49,87–90 This observation is supported by literature from corticosteroid-treated adult populations, which shows that after corticosteroid termination, BMD increases and clinical fracture risk declines.102,103 However, the age of corticosteroid administration may play a role in this respect, as corticosteroid exposure during puberty, a critical period for bone mass acquisition, may impact BMD more severely and permanently than during the prepubertal period.104,105 In addition, the fracture risk associated with corticosteroids in other populations may be due to mechanisms not definitively assessed by BMD measurements, such as altered bone structure and increased risk of falls due to muscle weakness.106 Ultimately, a large proportion of CAYA cancer survivors have been treated with (higher doses) corticosteroids, and it is unclear if the benefits of BMD surveillance outweigh the potential harms for this substantive group. Therefore, no recommendation can be formulated for or against BMD surveillance. This surveillance decision should be made by the survivor and healthcare provider together, after careful consideration of the potential harms and benefits (Figure 2 and Survivor Information Brochure) and additional risk factors (Figure 3).

Abdominal/pelvic irradiation was not included in the surveillance recommendations because the moderate-quality evidence for an increased risk of very low BMD was based on only one study, and because it is uncertain whether the risk of (very) low BMD for survivors treated with abdominal/pelvic irradiation who did not develop hypogonadism is increased.

In CAYA cancer survivors with hypogonadism or GHD, BMD measurements should be performed as part of standard endocrine care, which is best done by a medical bone health specialist in the context of hypogonadism or GHD management. A medical bone health specialist may include specialists such as an endocrinologist (most settings), internist, pediatrician, rheumatologist, or general practitioner, depending on country and setting. We refer to the IGHG guidelines premature ovarian insufficiency107 and male gonadotoxicity108 for survivors at risk of hypogonadism.

What surveillance modality should be used?

The included clinical practice guidelines in related populations all advise DXA (lumbar spine and total body less head [TBLH] or total hip, depending on age) for BMD surveillance.24,109,110 The International Society of Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) 2019 pediatric position states that the lumbar spine and TBLH are the preferred sites for BMD measurements.25 In addition, although hip measurements are generally not preferred in younger children due to variability in skeletal development and limited reference values, they can be useful in adolescents at-risk for bone fragility who would benefit from continuity of DXA measurements through transition into adulthood, as is the case for CAYA cancer survivors. One of the included guidelines recommends to avoid QCT for clinical application based on higher radiation doses applied compared to DXA (radiation exposure from pQCT is much lower, although slightly higher than DXA),110 and the ISCD currently considers both quantitative modalities primarily research techniques.24 Although the panel appreciates the value of volumetric BMD measured by (p)QCT, clear QCT-derived BMD thresholds associated with fractures have not yet been established. Furthermore, the panel has concerns about the availability of (p)QCT in most settings (expert opinion). We found that the diagnostic value of QUS compared to DXA is moderate in survivors (very-low quality evidence). However, QUS is not endorsed generally in diagnosing reduced BMD in CAYAs, and appropriate normative data are scarce (expert opinion). Based on these considerations, we recommend a DXA scan of the lumbar spine (posterior-anterior L1-L4), TBLH (in children and adolescents), and total hip (in adolescents and adults) for BMD surveillance (strong recommendation). QCT is currently not recommended for BMD surveillance (evidence-based guidelines and expert opinion). No recommendation for or against using pQCT and QUS for BMD surveillance was formulated.

When should surveillance be initiated and at what frequency should it be performed?

BMD Z-scores seem to increase in survivors from entry into long-term follow-up (LTFU) onwards. However, longitudinal studies that include more than two years off therapy investigating the average time to development of (very) low BMD to inform the timing of BMD surveillance were absent. In general, screening for a condition is only justified when results have treatment implications.111 Bisphosphonates can effectively treat osteoporosis and reduce fracture risk in children and adults.98,112 However, because bisphosphonates have several known and theoretical side-effects in children,113 their use is presently only considered in individuals with severe bone fragility (fragility fractures ± very low BMD), and reduced potential for BMD restitution and vertebral body reshaping following VF.104,114 Prophylactic bisphosphonate therapy (i.e. treating a low BMD Z-score in the absence of fractures) is not currently recommended.110,114 This means that bisphosphonates are not indicated when BMD deficits are detected through primary surveillance in this age group. Initiating bisphosphonate treatment solely based upon very low BMD is also controversial in CAYA cancer survivors that have achieved PBM (around the age of 25 years), because of low absolute fracture risk, low bisphosphonate efficacy if active bone loss is absent, and potentially long treatment duration, but may be considered in older survivors under specific circumstances. PBM is predictive of bone status in later adulthood and therefore represents an important landmark in time.14 However, the interval between entering LTFU and attaining the age of 25 years may be long for many survivors, which represents a period of potential increased risk of (very) low BMD and fractures. In addition, it is important to optimize PBM acquisition, and interventions such as exercise and hormone replacement therapy are most effective during puberty.96,115 Hence, BMD surveillance is recommended at entry into LTFU (between two to five years following completion of therapy) and if normal (Z-score >−1), it is recommended to repeat surveillance at 25 years of age when PBM should be achieved (expert opinion). In the small proportion of survivors for whom these timepoints overlap or are in proximity, one DXA scan is sufficient. Between these two measurements and thereafter, BMD surveillance should be performed as clinically indicated based on BMD and ongoing risk assessment. Furthermore, BMD trajectories are more informative than a single, cross-sectional measurement.

What should be done when abnormalities are identified?

The two included clinical practice guidelines for BMD treatment state that bisphosphonate therapy should be reserved for patients with overt bone fragility.109,110 Furthermore, these guidelines conclude that adequate dietary calcium and vitamin D intake is important for optimal bone health, and that supplementation is warranted in case of deficit. The presence of endocrinopathies such as hypogonadism and GHD should be evaluated and corrected. In addition, these guidelines recommend adequate weight-bearing physical activity, and one guideline underscores that negative lifestyles such as smoking and any alcohol use should be avoided.110

The panel drafted the following recommendations based on published evidence-based guidelines and expert opinion. In CAYA cancer survivors with a BMD Z-score ≤−2, referral to (or consultation of) a medical bone health specialist is recommended for further (endocrine) evaluation, interpretation of BMD findings, treatment, and follow-up (expert opinion). In survivors with a BMD Z-score ≤−1 and >−2, it is recommended to: 1) evaluate for the presence of endocrine defects (hypogonadism, GHD etc.), and consult a medical bone health specialist for further evaluation as clinically indicated (very low-quality evidence and evidence-based guidelines); and 2) repeat DXA after 2 years, and thereafter as clinically indicated based on BMD change (i.e. in case of BMD decline more than the DXA machine’s least significant change25) and ongoing risk assessment (expert opinion). In all at-risk CAYA cancer survivors (i.e. those treated with C[S]RT, TBI, and/or corticosteroids), regardless of their BMD Z-score, it is recommended to counsel about the following lifestyle habits that are important to maintain or improve bone health: 1) engage in regular physical activity,116 especially weight-bearing and falls prevention activities (evidence-based guidelines and expert opinion); 2) abstain from smoking (moderate-quality evidence and evidence-based guidelines) and limit or avoid alcohol intake (evidence-based guidelines); 3) consume adequate dietary vitamin D (at least 400 IU/day) and calcium (at least 500 mg/day) irrespective of vitamin D status, and advise vitamin D supplementation in survivors with 25OHD levels <20 ng/ml (plus calcium if the recommended amount of dietary calcium is not met) as per local or national guidelines (evidence-based guidelines and expert opinion); and 4) advise nutritional supplementation for survivors with low BMI or underweight (expert opinion).

Lastly, there were insufficient studies that assessed fracture outcomes to draw formal fracture-based surveillance recommendations. However, low-trauma VF are the clinical signature of osteoporosis, and low-trauma non-VF may also indicate a diagnosis of osteoporosis.24 Therefore, it is reasonable to refer at-risk CAYA cancer survivors with a history of low-trauma VF and non-VF (from entry into LTFU onwards) to a medical bone health specialist for further examination and treatment.

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive BMD surveillance strategy for CAYA cancer survivors, which could enhance early identification and adequate treatment and follow-up of survivors with (very) low BMD in a variety of LTFU settings, with the goal to prevent clinically relevant fractures and their consequences. In addition, the guideline panel identified gaps in the current literature that could guide future research to improve BMD surveillance and fracture prevention strategies in survivors (Panel).

Panel.

Gaps in knowledge of BMD deficits and fractures in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer survivors and directions for future research.

| Effect of different types of abdominal/pelvic irradiation (independent of hypogonadism) on the risk of low and very low BMD in female CAYA cancer survivors. |

| Effect of corticosteroids on the risk of low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors with increasing follow-up time. |

| Effect of the age of corticosteroid treatment on the risk of low and very low BMD. |

| Independent effect of TBI and HSCT on the risk of low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors. |

| Safe corticosteroid dose with regard to the risk of low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors, and if so, what is this dose. |

| Safe C(S)RT dose with regard to the risk of low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors, and if so, what is this dose. |

| Safe TBI dose with regard to the risk of low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors, and if so, what is this dose. |

| Risk and risk factors of low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors older than 40 years. |

| Sex- and pubertal stage-based differences in risk factors for low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors. |

| Risk and risk factors of low and very low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors treated for bone or soft tissue sarcomas. |

| Risk and risk factors of incident low-trauma vertebral and non-vertebral fractures in CAYA cancer survivors, including treatment-related risk factors and other risk factors such as very low BMD, history of fractures, and maternal hip fracture etc. (included in the FRAX® fracture risk profile for older adults), the most frequent sites of fractures, and the disability and impact on quality of l ife resulting from low-trauma fractures. |

| Further improvement and validation of prediction models (including demographic, lifestyle, and treatment factors) for low and very low BMD, and development of a prediction model for low-trauma fractures in CAYA cancer survivors. |

| Risk and risk factors of impaired bone structure and its association (± BMD) with low-trauma fractures in CAYA cancer survivors. |

| BMD trajectory and latency time of low-trauma fractures from cancer diagnosis into very long-term follow-up. |

| Association between QCT, pQCT and QUS measurements and fracture risk in CAYA cancer survivors. |

Abbreviations: BMD=bone mineral density; CAYA=childhood, adolescent, and young adult; C(S)RT=cranio(spinal) radiotherapy; HSCT=hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; (p)QCT=(peripheral) quantitative computed tomography; TBI=total body irradiation.

(Very) low BMD in survivors results from a complex, multifactorial process. We identified C(S)RT, abdominal/pelvic irradiation, total body irradiation, and corticosteroids as the main treatment-related risk factors for (very) low BMD. The primary mechanism through which these treatment modalities impact BMD varies; however, they can all lead to primary or secondary hypogonadism.117 Hypogonadism is a well-established cause of osteoporosis in the general population,118,119 and was independently associated with (very) low BMD in this review. Therefore, we hypothesize that hypogonadism is also a key driver of (very) low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors. Interestingly, moderate-quality evidence suggests no increased risk of (very) low BMD after treatment with ifosfamide or cyclophosphamide, two alkylating agents that may induce hypogonadism, especially at higher doses.107 We propose that the number of survivors with hypogonadism following ifosfamide or cyclophosphamide at any dose may have been too small (and/or received sex steroid replacement therapy) in available studies to detect a significant association with (very) low BMD.

As in the general population, host and lifestyle factors (e.g. White race, low BMI, smoking) contribute to the risk of (very) low BMD in CAYA cancer survivors. This makes it difficult to designate a distinct group of survivors at highest absolute risk of (very) low BMD solely based on prior cancer treatment. In this guideline, we recommend BMD surveillance for those survivors with an excess risk of very low BMD based on their prior cancer treatment (i.e. those treated with C[S]RT or TBI). Another approach is to incorporate treatment-related, demographic, and lifestyle factors into a prediction model for the absolute risk of (very) low BMD, which has been done for White adult childhood cancer survivors.6 However, this model needs to be further validated in survivors younger than 18 and older than 40 years of age, as well as in non-White survivors, before its use can generally be recommended in CAYA cancer survivors.

We recommend using DXA as the optimal modality for BMD surveillance in CAYA cancer survivors. However, in growing children more so than in adults, several limitations should be considered when interpreting areal BMD Z-scores generated by DXA. First, areal BMD may be underestimated in shorter individuals (for example as a result of GHD or delayed pubertal development) due to the confounding effect of bone size.120 To correctly interpret BMD findings in these individuals, the bone mineral apparent density (BMAD, g/cm3) can be estimated to reduce this confounding effect,121,122 and a medical bone health specialist can be consulted to further assist in BM(A)D interpretation. Second, although the association between lumbar spine BMD and VF remains consistent, Z-scores vary significantly in children depending upon the reference database that is used.123 This is further complicated by the fact that a Z-score of −1.5 for example might be normal for one individual, but abnormal for another, and that fragility fractures can occur at a BMD Z-score better than −2.123 Monitoring BMD trajectory by performing serial DXA scans (recommended in this guideline) could overcome some of these limitations.

An important aspect of the IGHG guideline process is the identification of gaps in knowledge and development of directions for future research. According to our findings, future studies should investigate the risk of reduced BMD after several treatment modalities and disease types (such as bone and soft tissue sarcomas) in more detail, and further develop and validate prediction models for very low BMD and low-trauma fractures (Panel). One important development in recent years is that bone research has expanded to consider not only BMD, but also bone structure, as an important indicator of bone strength. For example, it is now understood that low-trauma VF are a key sign of osteoporosis in the cancer setting, but that such fractures are frequently asymptomatic and thereby go undetected in the absence of VF imaging. While a longitudinal study of incident low-trauma VF and non-VF has been carried out up to six years following childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia diagnosis,101 studies beyond this duration and including other cancer settings are presently lacking. Therefore, additional longitudinal studies are needed to identify the risk and risk factors of incident low-trauma fractures, the most frequent sites of fractures, as well as the BMD trajectory with age.

Several limitations of the available literature are important in interpreting our BMD surveillance recommendations. For instance, much literature is available on the risk of BMD Z-scores ≤−1, but less is known about the risk of BMD Z-scores ≤−2 and low-trauma fractures, which are more clinically relevant outcomes. Furthermore, only few of the available studies discussed the bone health of patients with sarcomas, and the follow-up times differed significantly across included studies. In addition, although all studies performed multivariable analyses, some failed to adjust for all essential confounders (e.g., sex, BMI, age, and Tanner stage). These limitations hinder comparison of results between studies. Finally, recommendations regarding diagnostic modality, optimal timing of BMD surveillance, and interventions for survivors with reduced BMD were extrapolated from non-cancer populations and clinical expertise due to lack of evidence in CAYA cancer survivors.

Conclusion

This IGHG guideline provides harmonized recommendations for BMD surveillance that may improve health outcomes by facilitating more consistent LTFU care for current CAYA cancer survivors. In addition, it promotes strategically planned ongoing research that will inform future guideline updates.

Supplementary Material

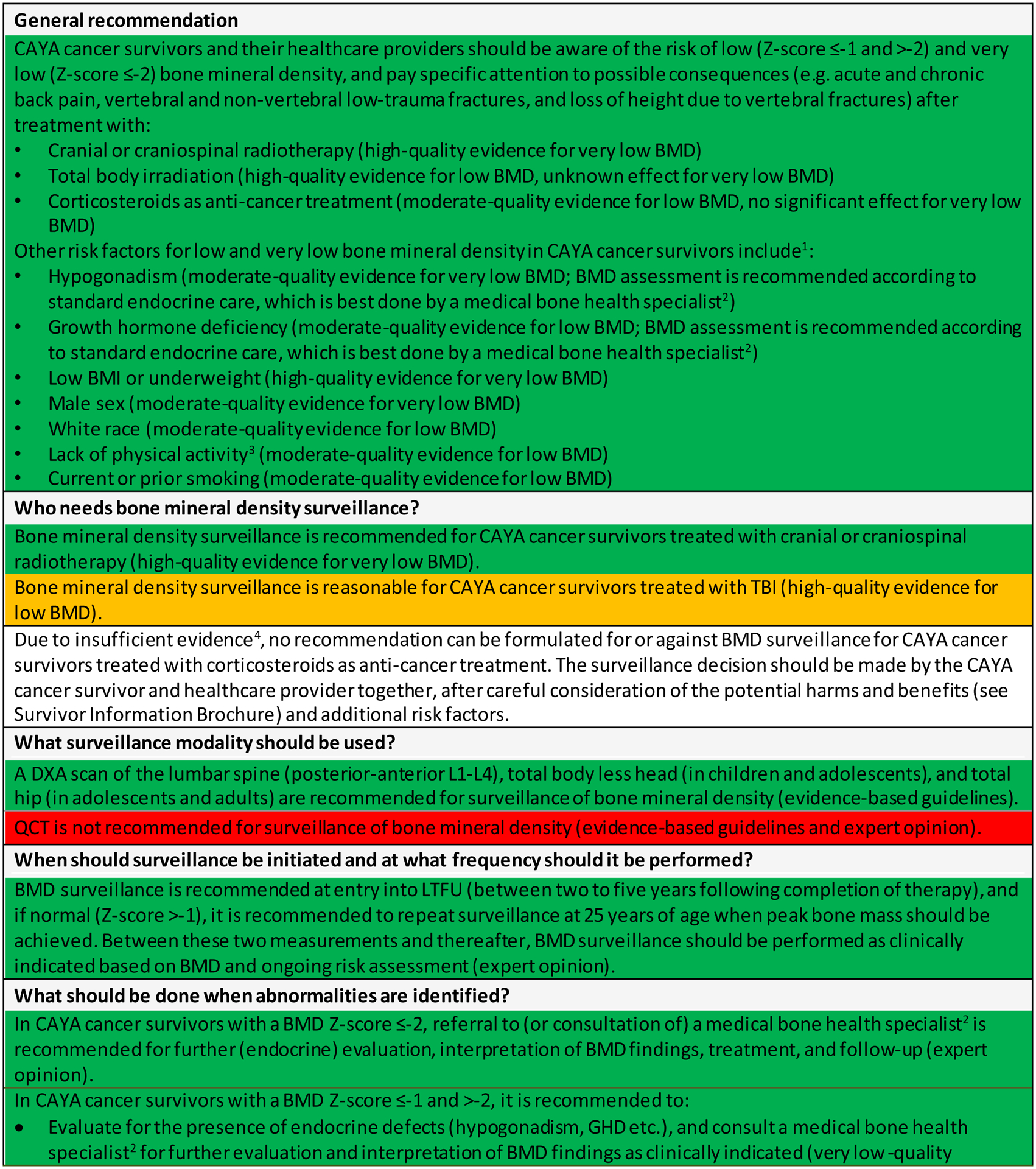

Figure 4.

Potential advantages and disadvantages of bone mineral density surveillance for childhood, adolescent and young adult cancer survivors – A Survivor Information Brochure.

Acknowledgements

We have no role of funding source to disclose. All authors had full access to the full data in the study and accept responsibility to submit for publication. We thank Prof. Charles Sklar (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA) and Prof. Jean-Marc Kaufman (Ghent University Hospital, Ghent, Belgium) for critically appraising the recommendations and manuscript as external reviewers and Debbie Crom (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA), Lisa Goerens (CCI Europe, Luxembourg), Marie Barth (CCI Europe, Germany), Tiago Costa (CCI Europe, Portugal), Mihael Severinac (CCI Europe, Croatia), and Zuzana Tomášiková (CCI Europe, Switzerland) as survivor representatives.

Declaration of interest

LMW received grants and personal fees from Novartis and Amgen (with funds to the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Institute), outside the submitted work. KKN received grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), during the conduct of the study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gatta G, Zigon G, Capocaccia R, et al. Survival of European children and young adults with cancer diagnosed 1995–2002. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(6):992–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LCM, et al. Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2705–2715. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chemaitilly W, Cohen LE, Mostoufi-Moab S, et al. Endocrine Late Effects in Childhood Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(21):2153–2159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Atteveld JE, Pluijm SMF, Ness KK, et al. Prediction of low and very low bone mineral density among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(25):2217–2225. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.01917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liuhto N, Grönroos MH, Malila N, Madanat-Harjuoja L, Matomäki J, Lähteenmäki P. Diseases of renal function and bone metabolism after treatment for early onset cancer: A registry-based study. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(5):1324–1332. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller BA, Doody DR, Weiss NS, Chow EJ. Hospitalization and mortality among pediatric cancer survivors: a population-based study. Cancer Causes Control. 2018;29(11):1047–1057. doi: 10.1007/s10552-018-1078-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.den Hoed MA, Klap BC, te Winkel ML, et al. Bone mineral density after childhood cancer in 346 long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(2):521–529. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2878-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Iersel L, Li Z, Srivastava DK, et al. Hypothalamic-Pituitary Disorders in Childhood Cancer Survivors: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Long-Term Health Outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(12):6101–6115. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemay V, Caru M, Samoilenko M, et al. Prevention of Long-term Adverse Health Outcomes With Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Physical Activity in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41(7):E450–E458. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boot AM, de Ridder MAJ, van der Sluis IM, van Slobbe I, Krenning EP, Keizer-Schrama SMPF de M. Peak bone mineral density, lean body mass and fractures. Bone. 2010;46(2):336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon CM, Zemel BS, Wren TAL, et al. The Determinants of Peak Bone Mass. J Pediatr. 2017;180:261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez CJ, Beaupré GS, Carter DR. A theoretical analysis of the relative influences of peak BMD, age-related bone loss and menopause on the development of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int a J Establ as result Coop between Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA. 2003;14(10):843–847. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1454-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2014;32(12):1218–1227. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(12):1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim LS, Hoeksema LJ, Sherin K. Screening for osteoporosis in the adult U.S. population: ACPM position statement on preventive practice. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rizzoli R, Bianchi ML, Garabédian M, McKay HA, Moreno LA. Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in the adolescents and the elderly. Bone. 2010;46(2):294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer: A national clinical guideline (SIGN Guideline No 132). 2013;(March):69. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign132.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Children’s Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers, Version 5.0. Monrovia, CA Child Oncol Gr. www.survivorshipguidelines.org [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutch Childhood Oncology Group. Richtlijn follow-up na kinderkanker meer dan 5 jar na diagnose. Published online 2010. www.skion.nl

- 22.Skinner R, Wallace WHB, Levitt GA. Long-term follow-up of people who have survived cancer during childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(6):489–498. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70724-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kremer LCM, Mulder RL, Oeffinger KC, et al. A worldwide collaboration to harmonize guidelines for the long-term follow-up of childhood and young adult cancer survivors: a report from the International Late Effects of Childhood Cancer Guideline Harmonization Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(4):543–549. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon CM, Leonard MB, Zemel BS. 2013 Pediatric Position Development Conference: executive summary and reflections. J Clin Densitom. 2014;17(2):219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shuhart CR, Yeap SS, Anderson PA, et al. Executive Summary of the 2019 ISCD Position Development Conference on Monitoring Treatment, DXA Cross-calibration and Least Significant Change, Spinal Cord Injury, Peri-prosthetic and Orthopedic Bone Health, Transgender Medicine, and Pediatrics. J Clin Densitom Off J Int Soc Clin Densitom. 2019;22(4):453–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2019.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, et al. Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet (London, England). 1993;341(8837):72–75. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92555-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353:i2089. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibbons RJ, Smith S, Antman E. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical practice guidelines: Part I: where do they come from? Circulation. 2003;107(23):2979–2986. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000063682.20730.A5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esbenshade AJ, Sopfe J, Zhao Z, et al. Screening for vitamin D insufficiency in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(4):723–728. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gawade PL, Ness KK, Sharma S, et al. Association of bone mineral density with incidental renal stone in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(4):388–397. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0241-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurney JG, Kaste SC, Liu W, et al. Bone mineral density among long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(7):1270–1276. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson RC, Madsen CD, Davis C, Gold SH. Bone density in survivors of childhood malignancies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1996;18(4):367–371. Accessed July 13, 2017. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8888743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hesseling PB, Hough SF, Nel ED, van Riet FA, Beneke T, Wessels G. Bone mineral density in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1998;11:44–47. Accessed July 13, 2017. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9876477 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hobusch GM, Noebauer-Huhmann I, Krall C, Holzer G. Do long term survivors of ewing family of tumors experience low bone mineral density and increased fracture risk? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(11):3471–3479. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3777-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holzer G, Krepler P, Koschat MA, Grampp S, Dominkus M, Kotz R. Bone mineral density in long-term survivors of highly malignant osteosarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(2):231–237. Accessed July 13, 2017. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12678358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2013;309(22):2371–2381. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isaksson S, Bogefors K, Åkesson K, et al. Low bone mineral density is associated with hypogonadism and cranial irradiation in male childhood cancer survivors. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(7):1261–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00198-020-05285-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joyce ED, Nolan VG, Ness KK, et al. Association of muscle strength and bone mineral density in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(6):873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaste SC, Rai SN, Fleming K, et al. Changes in bone mineral density in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46(1):77–87. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaste SC, Tong X, Hendrick JM, et al. QCT versus DXA in 320 survivors of childhood cancer: association of BMD with fracture history. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;47(7):936–943. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaste SC, Metzger ML, Minhas A, et al. Pediatric Hodgkin lymphoma survivors at negligible risk for significant bone mineral density deficits. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(4):516–521. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaste SC, Qi A, Smith K, et al. Calcium and cholecalciferol supplementation provides no added benefit to nutritional counseling to improve bone mineral density in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(5):885–893. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le Meignen M, Auquier P, Barlogis V, et al. Bone mineral density in adult survivors of childhood acute leukemia: impact of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other treatment modalities. Blood. 2011;118(6):1481–1489. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung W, Ahn H, Rose SR, et al. A prospective cohort study of late sequelae of pediatric allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Med. 2007;86(4):215–224. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31812f864d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandel K, Atkinson S, Barr RD, Pencharz P. Skeletal morbidity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(7):1215–1221. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.04.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miyoshi Y, Ohta H, Hashii Y, et al. Endocrinological analysis of 122 Japanese childhood cancer survivors in a single hospital. Endocr J. 2008;55(6):1055–1063. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.K08E-075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molinari PCC, Lederman HM, De Martino Lee ML, Caran EMM. Assessment of the late effects on bones and on body composition of children and adolescents treated for acute lymphocytic leukemia according to brazilian protocols. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2017;35(1):78–85. doi: 10.1590/1984-0462/;2017;35;1;00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Muszynska-Roslan K, Konstantynowicz J, Panasiuk A, Krawczuk-Rybak M. Is the treatment for childhood solid tumors associated with lower bone mass than that for leukemia and Hodgkin disease? Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;26(1):36–47. doi: 10.1080/08880010802625472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pietilä S, Sievänen H, Ala-Houhala M, Koivisto A-M, Liisa Lenko H, Mäkipernaa A. Bone mineral density is reduced in brain tumour patients treated in childhood. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(10):1291–1297. doi: 10.1080/08035250600586484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Polgreen LE, Petryk A, Dietz AC, et al. Modifiable risk factors associated with bone deficits in childhood cancer survivors. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Remes TM, Arikoski PM, Lahteenmaki PM, et al. Bone mineral density is compromised in very long-term survivors of irradiated childhood brain tumor. Acta Oncol. Published online January 2018:1–10. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1431401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ruza E, Sierrasesumaga L, Azcona C, Patino-Garcia A. Bone mineral density and bone metabolism in children treated for bone sarcomas. Pediatr Res. 2006;59(6):866–871. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000219129.12960.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siegel DA, Claridy M, Mertens A, et al. Risk factors and surveillance for reduced bone mineral density in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(9). doi: 10.1002/pbc.26488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siviero-Miachon AA, Spinola-Castro AM, de Martino Lee ML, et al. Visfatin is a positive predictor of bone mineral density in young survivors of acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Bone Min Metab. 2017;35(1):73–82. doi: 10.1007/s00774-015-0728-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sloof N, Hinderschot E, Griffin M, et al. The Impact of Physical Activity on the Health of Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: An Exploratory Analysis. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. Published online May 2019. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2019.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staba Hogan MJ, Ma X, Kadan-Lottick NS. New health conditions identified at a regional childhood cancer survivor clinic visit. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(4):682–687. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Santen SS, Olsso DS, Van Den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, et al. Fractures, Bone mineral density, and final height in craniopharyngioma patients with a follow-up of 16 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(4):E1397–E1407. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watsky MA, Carbone LD, An Q, et al. Bone turnover in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(8):1451–1456. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wei C, Candler T, Davis N, et al. Bone Mineral Density Corrected for Size in Childhood Leukaemia Survivors Treated with Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Total Body Irradiation. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;89(4):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000487996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilson CL, Chemaitilly W, Jones KE, et al. Modifiable Factors Associated with Aging Phenotypes among Adult Survivors of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(21):2509–2515. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.9525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han JW, Kim HS, Hahn SM, et al. Poor bone health at the end of puberty in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(10):1838–1843. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zürcher SJ, Jung R, Monnerat S, et al. High impact physical activity and bone health of lower extremities in childhood cancer survivors: A cross-sectional study of SURfit. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(7):1845–1854. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Latoch E, Konstantynowicz J, Krawczuk-Rybak M, Panasiuk A, Muszyńska-Rosłan K. A long-term trajectory of bone mineral density in childhood cancer survivors after discontinuation of treatment: retrospective cohort study. Arch Osteoporos. 2021;16(1):45. doi: 10.1007/s11657-020-00863-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bhandari R, Teh JB, Herrera C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for vitamin D deficiency in long-term childhood cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(7):e29048. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aaron M, Nadeau G, Ouimet-Grennan E, et al. Identification of a single-nucleotide polymorphism within CDH2 gene associated with bone morbidity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(6):409–420. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2018-0169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Benmiloud S, Steffens M, Beauloye V, et al. Long-term effects on bone mineral density of different therapeutic schemes for acute lymphoblastic leukemia or non-Hodgkin lymphoma during childhood. Horm Res Paediatr. 2010;74(4):241–250. doi: 10.1159/000313397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bloomhardt HM, Sint K, Ross WL, et al. Severity of reduced bone mineral density and risk of fractures in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia and lymphoma undergoing guideline-recommended surveillance for bone health. Cancer. 2020;126(1):202–210. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi YJ, Park SY, Cho WK, et al. Factors related to decreased bone mineral density in childhood cancer survivors. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(11):1632–1638. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.11.1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.De Matteo A, Petruzziello F, Parasole R, et al. Quantitative Ultrasound of Proximal Phalanxes in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41(2):140–144. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tabone M-D, Kolta S, Auquier P, et al. Bone Mineral Density Evolution and Its Determinants in Long-term Survivors of Childhood Acute Leukemia: A Leucémies Enfants Adolescents Study. HemaSphere. 2021;5(2):e518. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alikasifoglu A, Yetgin S, Cetin M, et al. Bone mineral density and serum bone turnover markers in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Comparison of megadose methylprednisolone and conventional-dose prednisolone treatments. Am J Hematol. 2005;80(2):113–118. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Im C, Ness KK, Kaste SC, et al. Genome-wide search for higher order epistasis as modifiers of treatment effects on bone mineral density in childhood cancer survivors /631/208/205/2138 /692/699/67/2332 /631/114/2114 /692/308/174 /631/208/177 /45/43 article. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26(2):275–286. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0050-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jones TS, Kaste SC, Liu W, et al. CRHR1 polymorphisms predict bone density in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3031–3037. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mostoufi-Moab S, Ginsberg JP, Bunin N, Zemel B, Shults J, Leonard MB. Bone density and structure in long-term survivors of pediatric allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Bone Min Res. 2012;27(4):760–769. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nysom K, Holm K, Michaelsen KF, Hertz H, Müller J, Mølgaard C. Bone mass after treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(12):3752–3760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pluskiewicz W, Łuszczyń A, Halaba Z, Drozdzowska B, Soń D. Skeletal status in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia assessed by quantitative ultrasound: A pilot cross-sectional study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28(10):1279–1284. doi: 10.1016/S0301-5629(02)00490-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sawicka-Żukowska M, Krawczuk-Rybak M, Muszynska-Roslan K, Panasiuk A, Latoch E, Konstantynowicz J. Does Q223R Polymorphism of Leptin Receptor Influence on Anthropometric Parameters and Bone Density in Childhood Cancer Survivors? Int J Endocrinol. 2013;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/805312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.van Beek RD, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SMPF, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, et al. No difference between prednisolone and dexamethasone treatment in bone mineral density and growth in long term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46(1):88–93. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wilson CL, Dilley K, Ness KK, et al. Fractures among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2012;118(23):5920–5928. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fiscaletti M, Samoilenko M, Dubois J, et al. Predictors of Vertebral Deformity in Long-Term Survivors of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: The PETALE Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):512–525. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Huang S, et al. Anterior hypopituitarism in adult survivors of childhood cancers treated with cranial radiotherapy: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(5):492–500. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.56.7933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Iersel L, van Santen HM, Potter B, et al. Clinical impact of hypothalamic-pituitary disorders after conformal radiation therapy for pediatric low-grade glioma or ependymoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(12):e28723. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Krasin MJ, et al. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(7):2242–2250. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brennan BMD, Rahim A, Adams JA, Eden OB, Shalet SM. Reduced bone mineral density in young adults following cure of acute lymphblastic leukaemia in childhood. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(11–12):1859–1863. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Azcona C, Burghard E, Ruza E, Gimeno J, Sierrasesúmaga L. Reduced bone mineralization in adolescent survivors of malignant bone tumors: Comparison of quantitative ultrasound and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003;25(4):297–302. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200304000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Demirkaya M, Sevinir B, Saglam H. Time-dependent alterations in growth and bone health parameters evaluated at different posttreatment periods in pediatric oncology patients. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;28(7):588–599. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2011.603819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marinovic D, Dorgeret S, Lescoeur B, et al. Improvement in bone mineral density and body composition in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A 1-year prospective study. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pluijm S, den Hoed M, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM. Catch-up of bone mineral density among long-term survivors of childhood cancer? Letter to the editor: Response to the article of Gurney et al. 2014. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(2):369–370. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pluskiewicz W, Halaba Z, Chelmecka L, Drozdzowska B, Sońta-Jakimczyk D, Karasek D. Skeletal status in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia assessed by quantitative ultrasound at the hand phalanges: A longitudinal study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30(7):893–898. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Van Den Heijkant S, Hoorweg-Nijman G, Huisman J, et al. Effects of growth hormone therapy on bone mass, metabolic balance, and well-being in young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2011;33(6):231–238. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31821bbe7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Follin C, Link K, Wiebe T, Moell C, Bjork J, Erfurth EM. Bone loss after childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: an observational study with and without GH therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(5):695–703. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cohen LE, Gordon JH, Popovsky EY, et al. Bone density in post-pubertal adolescent survivors of childhood brain tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(6):959–963. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dubnov-Raz G, Azar M, Reuveny R, Katz U, Weintraub M, Constantini NW. Changes in fitness are associated with changes in body composition and bone health in children after cancer. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(10):1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/apa.13052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mogil RJ, Kaste SC, Ferry RJJ, et al. Effect of Low-Magnitude, High-Frequency Mechanical Stimulation on BMD Among Young Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(7):908–914. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.MacKelvie KJ, Khan KM, McKay HA. Is there a critical period for bone response to weight-bearing exercise in children and adolescents? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(4):250–257. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.4.250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Munns CF, Shaw N, Kiely M, et al. Global Consensus Recommendations on Prevention and Management of Nutritional Rickets. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):394–415. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster J-Y. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int a J Establ as result Coop between Eur Found Osteoporos Natl Osteoporos Found USA. 2019;30(1):3–44. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kindler JM, Kelly A, Khoury PR, Levitt Katz LE, Urbina EM, Zemel BS. Bone Mass and Density in Youth With Type 2 Diabetes, Obesity, and Healthy Weight. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(10):2544–2552. doi: 10.2337/dc19-2164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dhakal S, Chen J, McCance S, Rosier R, O’Keefe R, Constine LS. Bone density changes after radiation for extremity sarcomas: Exploring the etiology of pathologic fractures. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(4):1158–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]