Abstract

Congenital heart defects (CHD) are the most commonly occurring birth defect and can occur in isolation or with additional clinical features comprising a genetic syndrome. Autosomal dominant variants in TAB2 are recognized by the American Heart Association as causing non-syndromic CHD, however, emerging data point to additional, extra-cardiac features associated with TAB2 variants. We identified 15 newly reported individuals with pathogenic TAB2 variants and reviewed an additional 24 subjects with TAB2 variants in the literature. Analysis showed 64% (25/39) of individuals with disease resulting from TAB2 single nucleotide variants (SNV) had syndromic CHD or adult-onset cardiomyopathy with one or more extra-cardiac features. The most commonly co-occurring features with CHD or cardiomyopathy were facial dysmorphism, skeletal and connective tissue defects and most subjects with TAB2 variants present as a connective tissue disorder. Notably, 53% (8/15) of our cohort displayed developmental delay and we suspect this may be a previously unappreciated feature of TAB2 disease. We describe the largest cohort of subjects with TAB2 SNV and show that in addition to heart disease, features across multiple systems are present in most TAB2 cases. In light of our findings we recommend that TAB2 be included on the list of genes that cause syndromic CHD, adult-onset cardiomyopathy and connective tissue disorder.

Keywords: Rare Disease, Pediatric Cardiology, Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Clinical Genetics

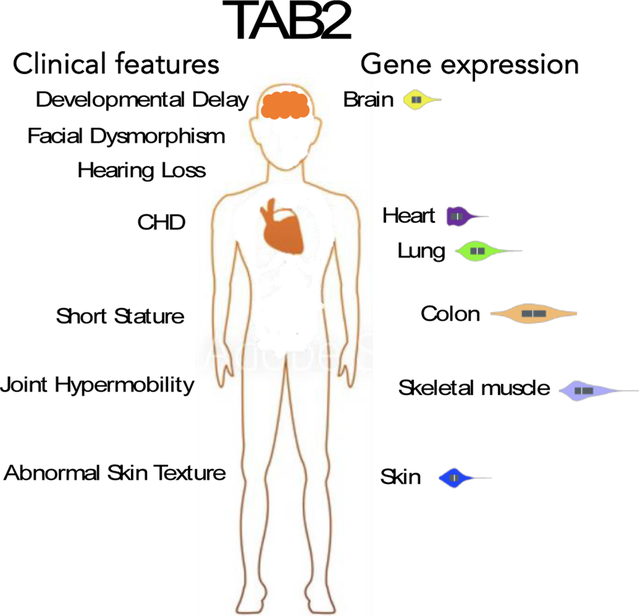

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Congenital heart defects (CHDs) are the most commonly occurring birth defect [1] resulting in infant mortality and morbidity and with an estimated prevalence of 1.4 million adults and 1 million children living with CHD in the United States [2]. CHD can occur in isolation or with additional clinical features comprising a genetic syndrome. While both genetic and environmental factors can contribute to CHD, many single gene disorders have been identified to cause CHD with over 40 genes reported to cause syndromic CHD and ~20 genes reported to cause non-syndromic CHD [3]. In a study of over 2,800 CHD cases a single gene disorder was reported to be the cause of disease in 10% of the cohort [4].

Autosomal dominant variants in TAB2 were reported to cause non-syndromic CHD [5] (OMIM 614980). Two unrelated patients who were each heterozygous for a different missense variants in TAB2 were noted to have outflow tract defects and no other clinical problems. Since this initial report, additional patients have been reported to have single nucleotide variants (SNV) in TAB2 [6–13]. The clinical presentation has primarily been reported as non-syndromic CHD, including valvular and cardiac outflow tract structural abnormalities. However, other clinical features have sometimes been noted including facial dysmorphism, skeletal and connective tissue defects [6–9]. Moreover, two families were reported to have members who presented with adult-onset cardiomyopathy; some of these individuals displayed extra-cardiac features with their disease presentation [8, 10]. In addition, two unrelated subjects heterozygous for TAB2 missense variants were reported to have frontometaphyseal dysplasia (FMD) with no heart problems [12, 13].

We report 13 new families with TAB2 SNV, most of whom have extra-cardiac clinical features in addition to CHD. This report doubles the current number of families with TAB2 mutation in the medical literature. We review all previously reported cases and show that most individuals with TAB2 SNV have facial dysmorphism, skeletal and connective tissue problems and that a notable proportion have neurodevelopmental delays as well.

Methods

Patient cohort and variants identified

The patients we present here were ascertained from exome databases of the clinical genetics diagnostic laboratories of Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics, Kansas City, MO, and Baylor Genetics, Houston, TX and through a survey of medical literature. A total of 15 individuals were ascertained from the aforementioned clinical laboratories. All patients initially presented with a structural or functional cardiac defect and a constellation of other features indicating an underlying genetic disorder of uncertainty warranting testing by clinical exome sequencing, which was performed as previously described [14]. Structural and functional cardiac defects were identified by echocardiogram and results were confirmed by a pediatric cardiologist. Physical exams were performed by a clinical geneticist and clinically relevant features of the proband were provided to the diagnostic laboratories for testing. Using the clinical information provided by the referring physician the 15 individuals were each found to harbor a sequencing variant in TAB2 (NM_015093.5), which was scored likely pathogenic or pathogenic by variant interpretation guidelines according to ACMG criteria [15]. Detailed variant information can be found in the supplement text (Table S1).

Search of the medical literature was conducted to identify individuals with a confirmed TAB2 pathogenic variant and clinical description. We systematically reviewed the literature for all cases of TAB2 published online up to January 1, 2021, written in English and contained in the National Institute of Health Pubmed database. The search was conducted using the term “TAB2”. We reviewed all papers returned by this search and identified 24 subjects across 10 manuscripts who were heterozygous for a pathogenic TAB2 variant, whose TAB2 genotype and clinical case description was published. For any subject that had been published in multiple papers, we reviewed and extracted clinical information about the subject from all papers, in order to compile the fullest clinical case description available in the literature.

Genotype / Phenotype Assessment

Clinical phenotypes for the 15 individuals were reported by the referring clinicians for testing. Therefore, some specific information was limited. Complete phenotypic information for the 15 individuals can be found in the supplement. In the literature search, we extracted data on the age at onset, age at diagnosis, age at death, and all clinical information noted in the manuscript and the supplemental information. This assessment yielded the identification of the overall clinical features: Cardiovascular defects: mitral valve, tricuspid valve, aortic valve, pulmonic valve, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, supravalvular aortic stenosis, atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, cardiomegaly, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, supraventricular tachycardia, arrhythmia. Problems with joints and skin including: abnormal skin texture, joint hypermobility, joint contractures, hyperconvex nails. Problems with skeletal system including: short stature, small extremities, short limbs, pes planus. Problems with development and growth including: speech and language delay, motor delay, hypotonia, failure to thrive. Additional clinical features noted were craniofacial dysmorphism, hearing loss, and myopia. Next, we examined what proportion of features were present in the cohort of 15 patients and the cohort identified from the literature individually to uncover any phenotypic bias, while also looking at the overall proportion of features of both cohorts combined.

Ethics Statement

Written informed consent for patients provided by Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics were obtained by the treating physician and/or genetic counselor A wavier of consent was obtained for patients provided by Baylor College of Medicine. Both organizations IRB’s approved this study.

Results

Cohort

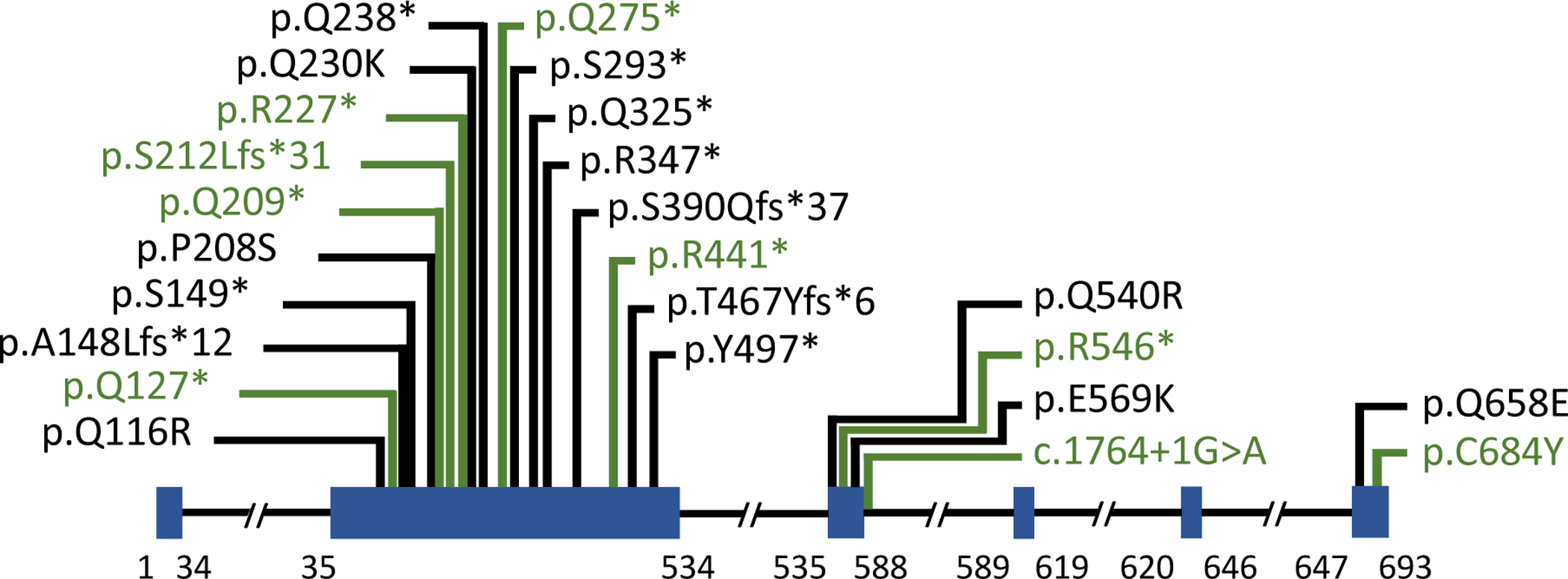

Our cohort consisted of a total of 15 affected individuals from 13 kindreds segregating TAB2 SNV (Table S2). Age at diagnosis ranged from 3 months to 26 years. Multiple patterns of inheritance were observed: 5 de novo, 3 maternal inheritance, 3 paternal inheritance and 4 with unknown inheritance due to the lack of parental samples. Most pathogenic variants in our TAB2 cohort were nonsense (73%,11/15), two were splice, one was a frameshift and one was a missense. This includes 9 TAB2 variants not previously reported as pathogenic or likely pathogenic, thereby improving the genetic diagnostic potential for this disease (Figure 1). Interestingly, of all the reported pathogenic variants, the majority (75%, 18/24) occurred in between amino acids 35 – 535 which is encoded by the largest coding exon, exon 2 of the gene (Figure 1). In addition, we found that some variants were also present in multiple unrelated families such as c.679C>T (p.Arg227*), c.1491T>A (p.Tyr497*), c.1636C>T (p.Arg546*), c.1764+1G>A (p.?), suggesting that these residues may be variant hot spot regions of the gene (Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 1.

TAB2 gene schematic. Pathogenic variants in TAB2 that were previously reported are shown in black and pathogenic variants newly reported are shown in green. Exons are illustrated as blue boxes.

Integrated analysis of this cohort and previously reported TAB2 subjects

We conducted a review of all individuals in the literature reported to be heterozygous for TAB2 SNV and identified 24 individuals from 11 different kindreds (Table S2) [5–13, 16, 17]. We present an integrated analysis of clinical features of our cohort plus those cases previously reported, to describe the largest number of TAB2 cases and the most comprehensive evaluation of features associated with TAB2 disease.

Cardiovascular

Most of our cohort (93%,14/15) displayed a structural heart defect (Table S2). The most commonly observed heart defects in our cohort were valvular with 87% (13/15) of subjects displaying a valvular defect, most often the mitral (73%,11/15) and tricuspid (66%,10/15) valves. Moreover, 10/15 subjects had polyvalvular disease. Adding subjects from the literature (Table 1), 77% of subjects (30/39) with TAB2 SNV had valvular defects and polyvalvular disease was noted in 56% (22/39). Over all subjects, mitral valve defects appeared most common (63%, 26/39), with tricuspid (49%,19/39) and aortic (36%,14/39) valve defects next. Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) was observed in one subject in our cohort, but was reported in five individuals previously for an overall frequency of 15%(6/39). Aortic coarctation was reported in two individuals who also had BAV.

Table 1.

Frequency of clinical findings in patients with pathogenic TAB2 variants. n = 39

| CARDIAC STRUCTURAL | 86% (33) |

| Mitral valve | 67% (26) |

| Tricuspid valve | 49% (19) |

| Aortic valve | 36% (14) |

| Pulmonic valve | 15% (6) |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 15% (6) |

| Aortic coarctation | 5% (2) |

| Supravalvular aortic stenosis | 5% (2) |

| Atrial septal defect | 8% (3) |

| Ventricular septal defect | 13% (5) |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 15% (6) |

| Patent foramen ovale | 5% (2) |

| Cardiomegaly | 3% (1) |

| CARDIAC FUNCTIONAL | 51% (20) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 46% (18) |

| cardiomyopathy | 5% (2) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 5% (2) |

| Arrhythmia | 8% (3) |

| JOINT and SKIN | 41% (16) |

| Abnormal skin texture | 21% (8) |

| Joint hypermobility | 28% (11) |

| Joint contractures | 5% (2) |

| Hypercovex nails | 5% (2) |

| SKELETAL DEFECTS | 54% (21) |

| Short stature | 44% (17) |

| Small extremities | 8% (3) |

| Short limbs | 10% (4) |

| Pes Planus | 8% (3) |

| GROWTH | 26% (10) |

| Speech and language delay | 15% (6) |

| Motor delay | 18% (7) |

| Hypotonia | 13% (5) |

| Failure to thrive | 10% (4) |

| DYSMORPHISM | 59%(23) |

| HEARING LOSS | 18% (7) |

| MYOPIA | 18% (7) |

Other structural defects in our cohort included patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) (33%, 5/15), ventricular septal defect (VSD) (13%, 2/15), atrial septal defect (ASD) (13%, 2/15) and patent foramen ovale (PFO) (13%, 2/15). VSD was reported previously in three subjects while ASD and PDA were each previously reported once (Table S2).

67% (10/15) of our cohort displayed functional heart defects with dilated cardiomyopathy the most frequent (53%, 8/15). Over all TAB2 patients 51% (20/39) displayed a functional defect with dilated cardiomyopathy observed in 46% (18/39) of individuals. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and supraventricular tachycardia were observed in 2 subjects each.

Joint and Skin

47% (7/15) of individuals in our cohort displayed issues with joint or skin, with joint hypermobility (33%, 5/15) and abnormal skin texture (27%, 4/15) being the most predominant. Hyperconvex nails were also observed in two unrelated individuals. The findings in our cohort are similar to previous reports where 38% (9/24) of individuals displayed connective tissue features with joint hypermobility (25%, 6/24) and abnormal skin texture (17%, 4/24) most frequently reported. Overall, 41% (16/39) of TAB2 patients had connective tissue concerns (Table 1).

Skeletal

60% (9/15) of our cohort displayed skeletal features with short stature (53%,8/15) being the most frequent (Table S2). Two individuals (subject 1 and 2) displayed postnatal short stature, while for the other individuals in our cohort, this detail was uncertain. This correlated with previous reports where 50% (12/24) of individuals displayed skeletal problems in which short statue was the reported majority (33%, 8/24). Other features such as small extremities, short limbs and pes planus were variably observed. Overall, 54% (21/39) of TAB2 subjects had skeletal issues (Table 1).

Facial Features

Facial dysmorphism was commonly reported in both our cohort (60%, 9/15) and in the literature (58%, 14/24) (Table S2). However, in our cohort referring clinical information was limited for five patients with only four patients (Subjects 1, 2, 3, and 5A) having specific details (see supplement). Hearing loss was also reported in our cohort (13%, 2/15) as was myopia (13%, 2/15), while one individual displayed esotropia (7%, 1/15). Across all TAB2 subjects 59% (23/39) had facial dysmorphism, 15% (6/39) had myopia and 18% (7/39) experienced hearing loss (Table 1). The low rate and age of onset of myopia reported in the overall TAB2 cohort suggest that it likely is not an identifying feature of disease given that the rate in the general population is higher [18].

Development and Growth

53% (8/15) of individuals in our TAB2 cohort displayed developmental delay, failure to thrive (FTT), and/or hypotonia. Speech language delay and motor delay each presented in 33% of our cohort (5/15) while failure to thrive and hypotonia each also appeared at an appreciable rate (27%, 4/15) (Table S2). None of the previous reports that focused on subjects with TAB2 SNV reported developmental delay. However, since half of the subjects in our cohort displayed developmental delay, FTT or hypotonia we hypothesized that developmental delay is a feature of TAB2 disease that was underappreciated in past reports.

TAB2 and neurodevelopmental disorders

Two different studies that combined sequenced ~5,500 children with severe neurodevelopmental disorders reported 5 unrelated cases with TAB2 SNV [6, 16, 19]. One subject found to have a TAB2 missense variant experienced developmental delay and dyspraxia in addition to congenital heart defects, connective tissue defects and facial dysmorphism [6, 16] (Table S2). SNV in TAB2 were also found in 4 patients with ‘severe, undiagnosed developmental disorder’ [19]. Each subject was heterozygous for a TAB2 SNV; three of these subjects had nonsense variants while the fourth had a missense. We note these subjects and variants, however, these subjects were not included in Table S2 because no clinical information was reported at the individual level and consequently it is unknown whether they had CHD and or other developmental disorders. Based on our TAB2 cohort and the results of these studies, we recommend that neurodevelopmental delay be taken into consideration as a feature of TAB2 disease.

Most subjects with TAB2 SNV had CHD syndromic with facial dysmorphism, skeletal and connective tissue defects

80% of the individuals in our cohort (12/15) presented with CHD and/or cardiomyopathy syndromic with extra-cardiac features. 60% (9/15) subjects had CHD with craniofacial dysmorphism, 9/15 had CHD plus skeletal defects, 8/15 had developmental delay along with CHD, and 7/15 had CHD and joint or skin problems. Most individuals in our cohort (60%, 9/15) had clinical problems in three or more systems, for example, CHD with facial dysmorphism and short stature (Figure 2).

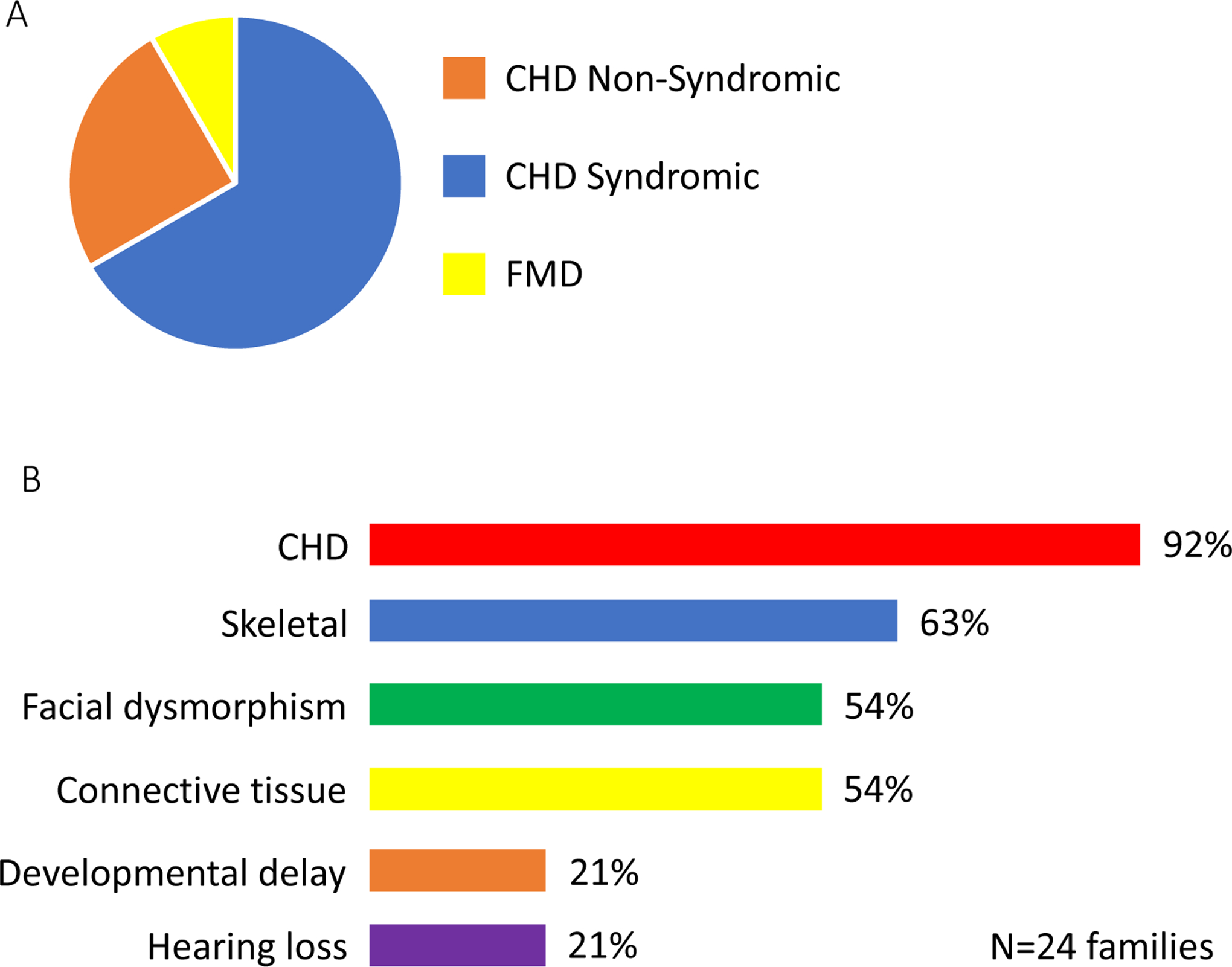

Figure 2.

TAB2 disease features. Clinical features of thirty-nine individuals with pathogenic TAB2 SNV were summarized. A. Most TAB2 subjects (64%) had congenital heart disease (CHD) syndromic with other features. Twenty-five percent of families had non-syndromic CHD and 8% of families had fronto-metaphyseal dysplasia (FMD) without any features of heart disease. B. The main clinical features observed in families with TAB2 are shown. CHD is the most common, extra-cardiac features were also observed as skeletal system defects (63% of families), facial dysmorphism (54% of families), and connective tissue defects (54% of families).

Five families with 13 affected individuals with TAB2 point mutation were previously reported to have CHD and/or cardiomyopathy syndromic with facial dysmorphism, connective tissue and/or skeletal defects (Table S2) [6–9, 16, 17]. Clinical features in extra-cardiac tissues across these 13 individuals included facial dysmorphism, skin and joint abnormalities, skeletal defects, developmental delay and dyspraxia, myopia, and hearing loss.

The combined analysis of all TAB2 subjects reveals that 64% (25/39) of individuals with disease resulting from TAB2 SNV have CHD or adult-onset cardiomyopathy syndromic with one or more extra-cardiac feature. The most common co-occurring feature with CHD or adult-onset cardiomyopathy was facial dysmorphism (57%,21/37) and skeletal defects (51%,19/37) and connective tissue defects (38%,14/37) (Figure 2). Of the individuals who had syndromic CHD, 92% (23/25) presented with CHD plus two or more extra-cardiac features (Table 1).

TAB2 SNV cause non-syndromic CHD

Four families with 9 affected individuals were previously reported to have non-syndromic CHD due to TAB2 SNV [5, 10, 11]. These individuals were reported to have CHD manifesting as valvular disease and/or dilated cardiomyopathy. In our cohort, 2 families with three subjects displayed non-syndromic CHD. Overall, 31% (12/39) of individuals with disease resulting from TAB2 SNV had non-syndromic CHD or adult-onset cardiomyopathy (Table 1). All other reports of individuals with TAB2 SNV have extra-cardiac features to their disease.

TAB2 SNV cause frontometaphyseal dysplasia

In our literature review we identified reports of two different de novo TAB2 missense variants from unrelated subjects displayed FMD without CHD [12, 13]. These individuals displayed classic signs of FMD including facial dysmorphism, hearing loss, under-modeled phalanges, joint contractures, and scoliosis. Although this disease association is still emerging, it appears that bone and joint related phenotypes are elicited by TAB2 dysfunction across a spectrum, and this may be variant, domain and/or mechanism dependent.

Intra-family variation indicates variable expressivity of TAB2 SNV

Multiple families segregating TAB2 variants show phenotypes indicative of variable expressivity: clinical features, age of onset and degree of severity varies. One example includes a report of two siblings: one presented with adult-onset cardiomyopathy and joint hyperextensibility, while the other presented with these two features plus VSD and hearing loss [8]. While both of these individuals had adult-onset cardiomyopathy, one was more severe requiring heart transplant. Another family was reported to segregate a TAB2 variant that presented as infantile-onset cardiomyopathy, including an infant who died of sudden cardiac arrest, while other family members were adults who displayed a range of valvular defects and/or cardiomyopathy [10].

Discussion

We report the largest case series of individuals heterozygous for TAB2 SNV (N=15) and review previously reported subjects (N=24). Taking all subjects into consideration, there is a clear association with TAB2 and syndromic CHD. 64% (25/39) of individuals with disease resulting from TAB2 SNV have CHD with one or more extra-cardiac feature. The most common co-occurring features with CHD were facial dysmorphism, skeletal and connective tissue defects. Of the individuals who had syndromic CHD, 92% (23/25) presented with CHD plus two or more extra-cardiac features. In contrast, 31% (12/39) of individuals with disease resulting from TAB2 SNV had non-syndromic CHD. Notably, two unrelated individuals with TAB2 SNV had FMD and no cardiovascular problem. Developmental delay was also present in 21% of TAB2 families and may be an underappreciated feature of TAB2 disease. Most cases of disease caused by TAB2 variants presented in childhood, however, there were a small number of individuals reported in the literature with adult-onset, cardiomyopathy and due to TAB2 mutation. Variable expressivity of TAB2 variants was noted as families manifesting a range in clinical features, severity of disease and a range in age of onset.

Additional support that TAB2 plays a role in multiple organ systems and exhibit pleiotropy comes from TAB2 gene expression pattern in humans and mice. Mouse studies showed TAB2 is ubiquitously expressed in adult and embryo mice [20]. Adult human TAB2 gene expression appeared to be ubiquitous (Supplemental Figure 1) supporting the notion that loss-of-function SNV in TAB2 can cause a multisystem disorder.

TAB2 forms a protein complex with MAP3K7, which serves as the core enzymatic component, TAB1 and TRAF6 to activate NF-kB and AP-1 and their transcriptional programs. TAB2 acts as a coactivator of MAP3K7 and is necessary for the activation of some of the enzyme’s signaling properties [21]. Autosomal dominant gain-of-function SNV in MAP3K7 cause FMD in some individuals and cardiospondylocarpofacial syndrome in others [12, 22]. Interestingly, two individuals with de novo missense TAB2 SNV were reported to have FMD and no CHD [12, 13]. Although functional studies of one TAB2 missense variant did not reveal a specific mechanism or alteration to surveyed outputs [12], the functional relationship among these proteins may support the phenotypic overlap in subjects with variants in TAB2 and MAP3K7 and suggests that the TAB2 clinical spectrum may extend to syndromic CHD and FMD. Therefore, missense variants and/or loss-of-function variants that escape non-sense mediated decay in TAB2 may exert a dominant-negative or gain-of-function effect that results in FMD-like features, suggesting that functional studies delineating these protein properties may be helpful in predicting phenotypic outcomes.

Currently, TAB2 is recognized by the American Heart Association as causing non-syndromic CHD [3]. In light of our findings that most subjects reported to be heterozygous for pathogenic TAB2 SNV have CHD with other features, we recommend that TAB2 also be included on the list of genes that cause syndromic CHD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the families for participating in this study. The expression data used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) on 05/01/2020. The GTEx Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health, and by NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. PEB is supported by NIH NINDS RO1 NS08372.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT The authors have no commercial association that might pose, create or create the appearance of a conflict of interest with the information presented in any submitted manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL Clinical data were collected and published with consent from the IRBs of Children’s Mercy Hospitals and Clinics and Baylor College of Medicine.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data that are part of this publication are available in this manuscript and in prior publications.

References

- 1.van der Linde D, et al. , Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2011. 58(21): p. 2241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilboa SM, et al. , Congenital Heart Defects in the United States: Estimating the Magnitude of the Affected Population in 2010. Circulation, 2016. 134(2): p. 101–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierpont ME, et al. , Genetic Basis for Congenital Heart Disease: Revisited: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 2018. 138(21): p. e653–e711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin SC, et al. , Contribution of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart disease probands. Nat Genet, 2017. 49(11): p. 1593–1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thienpont B, et al. , Haploinsufficiency of TAB2 causes congenital heart defects in humans. Am J Hum Genet, 2010. 86(6): p. 839–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homsy J, et al. , De novo mutations in congenital heart disease with neurodevelopmental and other congenital anomalies. Science, 2015. 350(6265): p. 1262–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ackerman JP, et al. , Whole Exome Sequencing, Familial Genomic Triangulation, and Systems Biology Converge to Identify a Novel Nonsense Mutation in TAB2-encoded TGF-beta Activated Kinase 1 in a Child with Polyvalvular Syndrome. Congenit Heart Dis, 2016. 11(5): p. 452–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caulfield TR, et al. , Protein molecular modeling techniques investigating novel TAB2 variant R347X causing cardiomyopathy and congenital heart defects in multigenerational family. Mol Genet Genomic Med, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritelli M, et al. , A recognizable systemic connective tissue disorder with polyvalvular heart dystrophy and dysmorphism associated with TAB2 mutations. Clin Genet, 2018. 93(1): p. 126–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, et al. , A novel TAB2 nonsense mutation (p.S149X) causing autosomal dominant congenital heart defects: a case report of a Chinese family. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2020. 20(1): p. 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasilescu C, et al. , Genetic Basis of Severe Childhood-Onset Cardiomyopathies. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018. 72(19): p. 2324–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wade EM, et al. , Mutations in MAP3K7 that Alter the Activity of the TAK1 Signaling Complex Cause Frontometaphyseal Dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet, 2016. 99(2): p. 392–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wade EM, et al. , Autosomal dominant frontometaphyseal dysplasia: Delineation of the clinical phenotype. Am J Med Genet A, 2017. 173(7): p. 1739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y, et al. , Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(16): p. 1502–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards S, et al. , Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med, 2015. 17(5): p. 405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosmicki JA, et al. , Refining the role of de novo protein-truncating variants in neurodevelopmental disorders by using population reference samples. Nat Genet, 2017. 49(4): p. 504–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Permanyer E, et al. , A single nucleotide deletion resulting in a frameshift in exon 4 of TAB2 is associated with a polyvalular syndrome. Eur J Med Genet, 2020. 63(4): p. 103854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baird PN, et al. , Myopia. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2020. 6(1): p. 99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deciphering Developmental Disorders, S., Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature, 2017. 542(7642): p. 433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanjo H, et al. , TAB2 is essential for prevention of apoptosis in fetal liver but not for interleukin-1 signaling. Mol Cell Biol, 2003. 23(4): p. 1231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takaesu G, et al. , TAB2, a novel adaptor protein, mediates activation of TAK1 MAPKKK by linking TAK1 to TRAF6 in the IL-1 signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell, 2000. 5(4): p. 649–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Goff C, et al. , Heterozygous Mutations in MAP3K7, Encoding TGF-beta-Activated Kinase 1, Cause Cardiospondylocarpofacial Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet, 2016. 99(2): p. 407–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data that are part of this publication are available in this manuscript and in prior publications.