Abstract

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common chronic gastrointestinal disorder. The role of pharmacotherapy for IBS is limited and focused mainly on symptom control.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the efficacy of bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.

Search methods

Computer assisted structured searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane library, CINAHL and PsychInfo were conducted for the years 1966‐2009. An updated search in April 2011 identified 10 studies which will be considered for inclusion in a future update of this review.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials comparing bulking agents, antispasmodics or antidepressants with a placebo treatment in patients with irritable bowel syndrome aged over 12 years were considered for inclusion. Only studies published as full papers were included. Studies were not excluded on the basis of language. The primary outcome had to include improvement of abdominal pain, global assessment or symptom score.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data from the selected studies. Risk Ratios (RR) and Standardized Mean Differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A proof of practice analysis was conducted including sub‐group analyses for different types of bulking agents, spasmolytic agents or antidepressant medication. This was followed by a proof of principle analysis where only the studies with adequate allocation concealment were included.

Main results

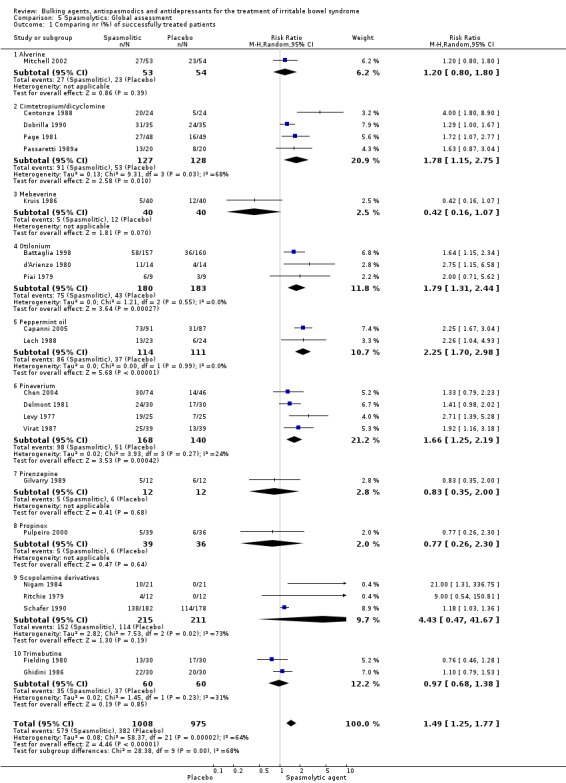

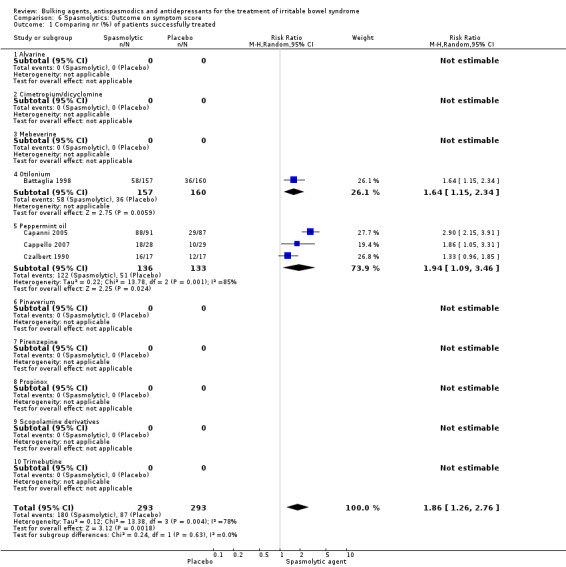

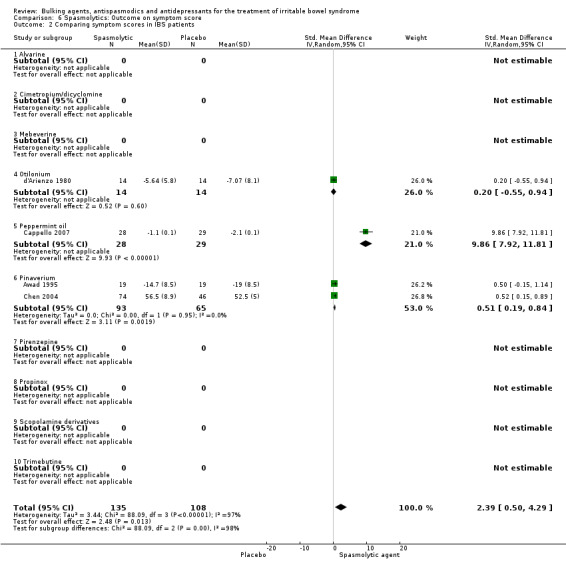

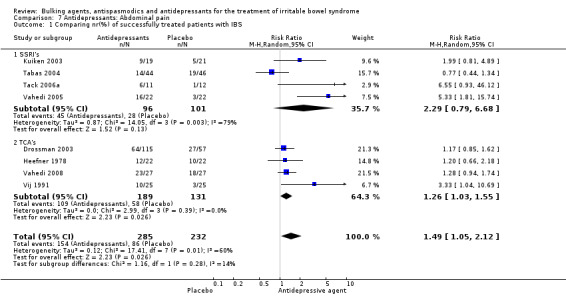

A total of 56 studies (3725 patients) were included in this review. These included 12 studies of bulking agents (621 patients), 29 of antispasmodics (2333 patients), and 15 of antidepressants (922 patients). The risk of bias was low for most items. However, selection bias is unclear for many of the included studies because the methods used for randomization and allocation concealment were not described. No beneficial effect for bulking agents over placebo was found for improvement of abdominal pain (4 studies; 186 patients; SMD 0.03; 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.40; P = 0.87), global assessment (11 studies; 565 patients; RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.33; P = 0.32) or symptom score (3 studies; 126 patients SMD ‐0.00; 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.43; P = 1.00). Subgroup analyses for insoluble and soluble fibres also showed no statistically significant benefit. Separate analysis of the studies with adequate concealment of allocation did not change these results. There was a beneficial effect for antispasmodics over placebo for improvement of abdominal pain (58% of antispasmodic patients improved compared to 46% of placebo; 13 studies; 1392 patients; RR 1.32; 95% CI 1.12 to 1.55; P < 0.001; NNT = 7), global assessment (57% of antispasmodic patients improved compared to 39% of placebo; 22 studies; 1983 patients; RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.77; P < 0.0001; NNT = 5) and symptom score (37% of antispasmodic patients improved compared to 22% of placebo; 4 studies; 586 patients; RR 1.86; 95% CI 1.26 to 2.76; P < 0.01; NNT = 3). Subgroup analyses for different types of antispasmodics found statistically significant benefits for cimteropium/ dicyclomine, peppermint oil, pinaverium and trimebutine. Separate analysis of the studies with adequate allocation concealment found a significant benefit for improvement of abdominal pain. There was a beneficial effect for antidepressants over placebo for improvement of abdominal pain (54% of antidepressants patients improved compared to 37% of placebo; 8 studies; 517 patients; RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.12; P = 0.03; NNT = 5), global assessment (59% of antidepressants patients improved compared to 39% of placebo; 11 studies; 750 patients; RR 1.57; 95% CI 1.23 to 2.00; P < 0.001; NNT = 4) and symptom score (53% of antidepressants patients improved compared to 26% of placebo; 3 studies; 159 patients; RR 1.99; 95% CI 1.32 to 2.99; P = 0.001; NNT = 4). Subgroup analyses showed a statistically significant benefit for selective serotonin releasing inhibitors (SSRIs) for improvement of global assessment and for tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) for improvement of abdominal pain and symptom score. Separate analysis of studies with adequate allocation concealment found a significant benefit for improvement of symptom score and global assessment. Adverse events were not assessed as an outcome in this review.

Authors' conclusions

There is no evidence that bulking agents are effective for treating IBS. There is evidence that antispasmodics are effective for the treatment of IBS. The individual subgroups which are effective include: cimetropium/dicyclomine, peppermint oil, pinaverium and trimebutine. There is good evidence that antidepressants are effective for the treatment of IBS. The subgroup analyses for SSRIs and TCAs are unequivocal and their effectiveness may depend on the individual patient. Future research should use rigorous methodology and valid outcome measures.

Keywords: Humans, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Pain/therapy, Antidepressive Agents, Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use, Dietary Fiber, Dietary Fiber/therapeutic use, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Irritable Bowel Syndrome/therapy, Parasympatholytics, Parasympatholytics/therapeutic use, Phytotherapy, Phytotherapy/methods, Plantago, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome

This review evaluates the effectiveness of medical therapies for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). We considered studies involving bulking agents (a fibre supplement), antispasmodics (smooth muscle relaxants) or antidepressants (drugs used to treat depression that can also change pain perceptions) that used outcome measures including improvement of abdominal pain, global assessment (overall relief of IBS symptoms) or symptom score. We found that bulking agents are not effective for treating IBS. There is evidence that antispasmodics including cimetropium/dicyclomine peppermint oil, pinaverium and trimebutine are effective for the treatment of IBS. Antidepressants are effective for the treatment of IBS. The side effects of these medications were not evaluated in this review. Physicians should be aware of the limitations of drug therapies and discuss these limitations with their patients before prescribing medication for IBS.

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder characterized by fluctuating complains of abdominal pain or discomfort and an altered bowel habit resulting in diarrhoea or constipation. The prevalence of IBS ranges from 5‐18 % depending on the clinical setting and the diagnostic criteria that are used. IBS is slightly more common in females (Hungin 2003; Hillila 2004). IBS is associated with depressive and anxiety disorders as well with somatic co‐morbidities including fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and chronic pelvic pain (Riedl 2008).

Research shows that IBS can result in impaired health‐related quality of life and that IBS symptoms have a large impact on work productivity (Pare 2006; Creed 2001). IBS is also associated with increased health care utilization and costs (Longstreth 2003).

In the absence of a gold‐standard for diagnosing IBS, classification models have been developed including the Kruis scoring system, Manning criteria and Rome I, II, and III criteria (Manning 1978; Drossman 2006). Only the Rome I classification is validated (Ford 2010). These criteria are not widely used in clinical practice and the diagnosis of IBS is often made by a typical history, normal physical examination and the absence of alarm‐symptoms such as gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, or an abdominal mass (Jones 2000a).

The pathophysiology of IBS is still unclear. There are several putative mechanisms including visceral hypersensitivity, altered colonic motility, abnormal brain activation, serotine dysregulation, inflammation, abnormal colonic flora, stress, psychological factors and genetic factors (Talley 2006).

In the absence of a clear pathophysiology, explanation and reassurance are essential elements in the management of IBS (Jones 2000b). Pharmacotherapeutic interventions are limited and focus mostly on symptom control. High fibres diets and bulking agents are traditionally advised for their effect on stools and transit time (Burkitt 1972). Antispasmodics are given for their supposed effect on gastrointestinal motility. The more recent therapeutic options include the use of antidepressants, which are also given for other diseases associated with chronic pain (Verdu 2008).

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the efficacy of bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials comparing bulking agents, antispasmodics or antidepressants with a placebo were considered for inclusion. Cross‐over studies were eligible if data from the first phase were reported separately. Only studies published as a full paper were included. Studies were not excluded on the basis of language.

Types of participants

Patients aged over 12 years with irritable bowel syndrome, diagnosed either using predefined diagnostic criteria (e.g. Manning or Rome) or on clinical grounds were considered for inclusion. Studies including patients with functional bowel disorders without separate data for IBS patients were also included if the proportion of IBS patients was more than 75% of the total included patients.

Types of interventions

Interventions including bulking agents, antispasmodics or antidepressants compared with a placebo treatment were considered for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Outcome measures for clinical trials of interventions in IBS have been discussed in several studies (Irvine 2006; Schoenfeld 2006). Primary outcome measures included:

Improvement of symptoms of abdominal pain;

Improvement of patients overall global assessment; and

Improvement of IBS‐symptom score.

Subgroup analyses included:

Soluble and insoluble bulking agents;

Individual antispasmodics; and

Selective serotonin releasing inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

A sensitivity analysis excluded studies with poor methodological quality.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Computer assisted structured searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, CINAHL and PsychInfo were conducted, searching entries from 1966 to March 2009. The following search strategies were used:

Title/abstract search: spastic colon, irritable colon, irritable bowel, functional bowel, colonic disease, colonic diseases, IBS, gastrointestinal syndrome, gastrointestinal syndromes

Combined with title/abstract search: bulking agent, bulking agents, fiber, fibers, fibre, fibres, psyllium, plantago ovata, husk, bran, ispaghula, wheat, oat, sterculia, karaya gum

Or combined with title/abstract search: antispasmodic, antispasmodics, parasympatholytic, parasympatholytics. spasmolytic , spasmolytics, mebeverine, rociverine, pinaverium bromide, otilonium bromide, cimetropium bromide, trimebutine, pirenzipine, alverine, scopolamine, butylscopolamine, hyoscine , muscarinic antagonist, peppermint oil, mint oil

Or combined with title/abstract search: antidepressant, antidepressants, antidepressive agent, antidepressive agents, tricyclic, TCA, TCAs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SSRI, SSRIs

No limits or filters were used.

An updated search in April 2011 identified 10 studies which will be considered for inclusion in a future update of this review (See Characteristics of studies awaiting classification).

Searching other resources

The reference lists of the retrieved articles and reviews were hand searched to identify additional studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One author (LR) screened the title and abstract of all studies identified by the literature searches for eligibility . The full text articles were retrieved for all potentially eligible studies. The full text articles were screened according to predefined criteria by the same reviewer. All the doubtful articles were screened by a second reviewer (AOQ) and consensus on inclusions/ exclusion was achieved by discussion.

The predefined exclusion criteria included:

Not a randomised controlled trial

No placebo group

Inappropriate patient group

Patients younger than 12, diagnosis of functional bowel disorders not specified as IBS

Intervention not involving bulking agent, antispasmodic or antidepressant or mixed preparations

An outcome measurement other than abdominal pain, global assessment or IBS‐symptom score.

No extractable results or cross‐over trial with no report of first phase data

Duplicate trials

Data extraction and management

All studies were blinded for the reviewers in respect of authors, date of publication and journal or database of publication. Data were extracted independently by two authors for each study. A standardized data extraction form was used. Where necessary data were extracted from figures. If essential data were absent, the author of the article was contacted and requested to provide additional information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of included trials was independently assessed by two authors (AOQ and LR or NdW or GR).

Quality assessment criteria included: method of randomisation, concealment of allocation, blinding of patients and outcome measurers and description of lost to follow‐up.

Differences of opinion were resolved by discussion between two reviewers, and in case of disagreement by all the reviewers. A methodology expert (GvdH) was consulted for specific queries

In consultation with the Dutch Cochrane centre, concealment of allocation was used for additional analyses, since concealment of allocation is the only quality item that has proven to be associated with study outcome (Pidal 2007, Wood 2008).

Measures of treatment effect

The analyses were conducted using RevMan 5.0 software. For the dichotomous outcomes the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. For the continuous data standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

A fixed‐ or random‐effects model was used, based on the heterogeneity between study data. Statistical heterogeneity was explored with the Chi square test with significance set at P <0.10. When statistically significant heterogeneity occurred, a random‐effects model was used for the analyses.

There were differences in the direction of the scales for the continuous data. To correct for this the data from scales increasing with disease severity were multiplied by ‐1.

First, a proof of practice analysis was conducted, including all available data. This was followed by a proof of principle analysis where only the studies with adequate allocation concealment were included.

Results

Description of studies

Bulking agents

The search identified 1118 studies, of which, after screening title and abstract 72 were potentially eligible. After applying the exclusion criteria to the full‐text publications of these 72 potentially eligible studies, 12 articles remained for review and meta‐analysis.

Sixty articles were excluded (table of characteristics of excluded studies), of which twenty‐six were not randomized controlled trials (exc1). Fourteen studies did not involve a placebo treatment (exc2). Four studies included patients with functional bowel disorders without providing extractable results for the patients with IBS (exc3 and exc4). Two studies involved an intervention with a mixed preparation (exc5). Two studies did not report the outcome of interest (exc6). Eleven studies were cross‐over trials with no report of the first phase data or did not provide extractable results (exc7). One study was a duplicate publication (exc8).

Twelve papers remained for review and meta‐analysis (Table of characteristics of included studies). Two studies had a cross‐over design (Jalihal 1990; Lucey 1987). The studies were published between 1976 and 2005 (Soltoft 1976; Rees 2005). The research setting was a GI out patients’ clinic in 11 studies, in the other three the setting was unclear (Arthurs 1983; Longstreth 1981; Soltoft 1976). Seven studies used a run‐in period of 1 to 4 weeks before beginning the actual trial (Fowlie 1992; Longstreth 1981; Prior 1987; Rees 2005; Soltoft 1976). The studies included between 20 and 168 participants (Jalihal 1990; Nigam 1984). The mean age of the participants ranged from 28 years to 46 years (Arthurs 1983; Aller 2004). The percentage of female participants included ranged from 20% to 83% (Jalihal 1990; Longstreth 1981). Six studies used insoluble fibres as intervention (Aller 2004; Fowlie 1992; Kruis 1986; Lucey 1987; Rees 2005; Soltoft 1976) and six studies used soluble fibres as intervention (Arthurs 1983; Jalihal 1990; Longstreth 1981; Nigam 1984; Prior 1987; Ritchie 1979). The intervention period lasted from 4 weeks (Ritchie 1979) to 16 weeks (Kruis 1986).

Antispasmodics

The search identified 444 studies, of which, after screening title and abstract, 144 were potentially eligible. After applying the exclusion criteria to the full‐text publications of these 144 potentially eligible studies, 29 articles remained for review and meta‐analysis.

One hundred and fifteen articles were excluded (table of characteristics of excluded studies). Thirty‐eight were not randomised controlled trials (exc1). Thirty four studies did not involve a placebo treatment (exc2). Six studies included patients with functional bowel disorders without providing extractable results for the patients with IBS (exc3 and exc4). Three studies involved an intervention with a mixed preparation (exc5). Twelve studies did not report the outcome of interest (exc6). Nineteen studies had no extractable results or were cross‐over trials with no report of the first phase data (exc7). Three were duplicate publications (exc8) (Baldi 1992; Glende 2002; Koch 1998).

Twenty‐nine papers remained review and meta‐analysis (Table of characteristics of included studies; Awad 1995; Baldi 1991; Battaglia 1998; Capanni 2005; Cappello 2007; Centonze 1988; Chen 2004; Czalbert 1990; d'Arienzo 1980; Delmont 1981; Dobrilla 1990; Dubarry 1977; Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986; Gilvarry 1989; Kruis 1986; Lech 1988; Levy 1977; Liu 1997; Mitchell 2002; Moshal 1979; Nigam 1984; Page 1981; Passaretti 1989a; Piai 1979; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979; Schafer 1990; Virat 1987). Two studies had a cross‐over design (Moshal 1979; Piai 1979). The studies were published between 1977 and 2007 (Levy 1977; Cappello 2007). The research setting was definitely defined as secondary care in 18 studies, none of the studies was definitely conducted in primary care. Fourteen studies used a run‐in period of 1 to 4 weeks before beginning the actual trial. Five of these used a placebo during the run‐in period and one used a high fibre diet (Gilvarry 1989). The studies included between 18 (Piai 1979) and 360 participants (Schafer 1990). The mean age of the participants ranged from 26 years (Fielding 1980) to 60.6 years (Baldi 1991). The percentage of female participants included ranged from 35% (Moshal 1979) to 100% (Awad 1995). The intervention period lasted from 1 week (Virat 1987) to 6 months (Centonze 1988). The antispasmodics are divided into ten pharmacological subgroups: Alverine (1 study), cimetropium/dicyclomine (4 studies), mebeverine (2 studies), Otilonium (6 studies), peppermint oil (5 studies), pinaverium (6 studies),pirenzepine (1 study), propinox (1 study), scopolamine derivates (4 studies), and trimebutine (3 studies).

Antidepressants

The search identified 419 studies, of which, after screening title and abstract 56 were potentially eligible. After applying the exclusion criteria on the full‐text publications of these 56 potentially eligible studies, 15 articles remained for review and meta‐analysis.

Forty articles were excluded (table of characteristics of excluded studies). Twenty were not randomized controlled trials (exc1). Six studies did not involve a placebo treatment (exc2). One study involved an intervention with a mixed preparation (exc5). Four studies did not report the outcome of interest (exc6). Three studies had no extractable results or were cross‐over trials with no report of the first phase data (exc7). Six studies were duplicate publications (exc8) (Kalpert 2005, Han 2009; Marks 2008; Block 1983; Tripathi 1983; Greenbaum 1987).

Fifteen studies remained for review and meta‐analysis (table of characteristics of included studies). One study had a cross‐over design (Tack 2006a). The studies were published between 1978 and 2009 (Heefner 1978; Masand 2009). Two studies were partly conducted in primary care (Myren 1982; Boerner 1988), the remainder in secondary care. Three studies used a run‐in period of 1 to 2 weeks before beginning the actual trial (Rajagopalan 1998; Tack 2006a; Talley 2008a). One study had a placebo run‐in period of unspecified duration (Masand 2009). One study randomised patients who had completed a 7 week open‐label high‐fibre trial (Tabas 2004). The studies included between 23 and 201 participants (Tack 2006a; Drossman 2003). The mean age of the participants ranged from 32 years to 49 years (Masand 2009). The percentage of female participants included ranged from 13% (Heefner 1978) to 100% (Drossman 2003). Five studies used a SSRI as the intervention (Kuiken 2003; Masand 2009; Tabas 2004; Tack 2006a; Vahedi 2005). Nine studies used a TCA the as intervention (Bahar 2008; Myren 1982; Boerner 1988; Drossman 2003; Heefner 1978; Rajagopalan 1998; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991). One study compared an SSRI and a TCA with placebo treatment (Talley 2008a). The intervention period lasted from 4 weeks (Myren 1982) to 12 weeks (Vahedi 2005).

Risk of bias in included studies

The results of the risk of bias assessment are shown in Figure 1.The risk of bias was low for most items. However, selection bias is unclear for many of the included studies because the methods used for randomization and allocation concealment were not described.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Bulking agents None of the twelve studies on bulking agents described the methods used for randomization and these studies were rated as unclear for this item. Five of the studies were rated as low risk for allocation concealment (Fowlie 1992; Jalihal 1990; Longstreth 1981; Ritchie 1979; Soltoft 1976). The other seven studies were rated as unclear for allocation concealment.

Antispasmodics Three studies reported on the methods used for randomization (Capanni 2005; Cappello 2007; Piai 1979) and were rated as low risk for this item. The other twenty‐six studies did not report on methods used for randomization and were rated as unclear. Four studies were rated as low risk for allocation concealment (Awad 1995; Chen 2004; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979). The other studies were rated as unclear for this item.

Antidepressants Seven studies were reported the methods used for randomization and were rated as low risk for this item (Drossman 2003; Kuiken 2003; Tabas 2004; Talley 2008a; Vahedi 2005; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991). The other studies were rated as unclear. Six studies were rated as low risk for allocation concealment (Drossman 2003; Kuiken 2003; Tabas 2004; Talley 2008a; Vahedi 2005; Vahedi 2008). The other studies were rated as unclear for this item.

Blinding

Bulking agents Six studies were rated as low risk for blinding (Fowlie 1992; Jalihal 1990; Longstreth 1981; Nigam 1984; Ritchie 1979; Soltoft 1976). Rees 2005 used a single blind design and was rated as a high risk of bias. The other studies did not describe methods used for blinding and were rated as unclear.

Antispasmodics Eleven studies were rated as low risk for blinding (Awad 1995; Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986; Liu 1997; Mitchell 2002; Moshal 1979; Nigam 1984; Page 1981; Passaretti 1989a; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979). The other studies did not describe methods used for blinding and were rated as unclear.

Antidepressants Nine studies were rated as low risk for blinding (Kuiken 2003; Myren 1982; Rajagopalan 1998; Tabas 2004; Tack 2006a; Talley 2008a; Vahedi 2005; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991). Drossman 2003 used a single blind design and was rated as a high risk of bias. The other studies did not describe methods used for blinding and were rated as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Bulking agents Eleven studies were rated as low risk for incomplete outcome date (Aller 2004; Arthurs 1983; Fowlie 1992; Jalihal 1990; Kruis 1986; Longstreth 1981; Nigam 1984; Prior 1987; Rees 2005; Ritchie 1979; Soltoft 1976). One study was rated as unclear for this item (Lucey 1987).

Antispasmodics Twenty‐four studies were rated as low risk for incomplete outcome data (Awad 1995; Baldi 1991; Battaglia 1998; Capanni 2005; Cappello 2007; Centonze 1988; Delmont 1981; Dobrilla 1990; Dubarry 1977; Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986; Gilvarry 1989; Kruis 1986; Lech 1988; Levy 1977; Liu 1997; Mitchell 2002; Moshal 1979; Nigam 1984; Page 1981; Passaretti 1989a; Piai 1979; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979). Five studies were rated as unclear for this item (Chen 2004; Czalbert 1990; d'Arienzo 1980; Schafer 1990; Virat 1987).

Antidepressants Eleven studies were rated as low risk for incomplete outcome data (Bahar 2008; Drossman 2003; Heefner 1978; Kuiken 2003; Masand 2009; Myren 1982; Tabas 2004; Tack 2006a; Vahedi 2005; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991). Four studies were rated as unclear for this item (Bergmann 1991; Boerner 1988; Rajagopalan 1998; Talley 2008a).

Selective reporting

Bulking agents All twelve studies were rated as low risk for selective reporting (Aller 2004; Arthurs 1983; Fowlie 1992; Jalihal 1990; Kruis 1986; Longstreth 1981; Lucey 1987; Nigam 1984; Prior 1987; Rees 2005; Ritchie 1979; Soltoft 1976).

Antispasmodics Twenty‐six studies were rated as low risk for selective reporting (Awad 1995; Baldi 1991; Battaglia 1998; Capanni 2005; Cappello 2007; Centonze 1988; Delmont 1981; Dobrilla 1990; Dubarry 1977; Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986; Gilvarry 1989; Kruis 1986; Lech 1988; Levy 1977; Liu 1997; Mitchell 2002; Moshal 1979; Nigam 1984; Page 1981; Passaretti 1989a; Piai 1979; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979; Schafer 1990; Virat 1987). Three studies were rated as unclear for this item (Chen 2004; Czalbert 1990; d'Arienzo 1980).

Antidepressants Fourteen studies were rated as low risk for selective reporting (Bahar 2008; Bergmann 1991; Drossman 2003; Heefner 1978; Kuiken 2003; Masand 2009; Myren 1982; Rajagopalan 1998; Tabas 2004; Tack 2006a; Talley 2008a; Vahedi 2005; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991). One study was rated as unclear for this item (Boerner 1988).

Other potential sources of bias

Bulking agents All twelve studies were rated as low risk for other potential sources of bias (Aller 2004; Arthurs 1983; Fowlie 1992; Jalihal 1990; Kruis 1986; Longstreth 1981; Lucey 1987; Nigam 1984; Prior 1987; Rees 2005; Ritchie 1979; Soltoft 1976).

Antispasmodics Twenty‐six studies were rated as low risk for other potential sources of bias Awad 1995; Baldi 1991; Battaglia 1998; Capanni 2005; Cappello 2007; Centonze 1988; Delmont 1981; Dobrilla 1990; Dubarry 1977; Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986; Gilvarry 1989; Kruis 1986; Lech 1988; Levy 1977; Liu 1997; Mitchell 2002; Moshal 1979; Nigam 1984; Page 1981; Passaretti 1989a; Piai 1979; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979; Schafer 1990; Virat 1987). Three studies were rated as unclear for this item (Chen 2004; Czalbert 1990; d'Arienzo 1980).

Antidepressants Fourteen studies were rated as low risk for other potential sources of bias (Bahar 2008; Bergmann 1991; Drossman 2003; Heefner 1978; Kuiken 2003;Masand 2009; Myren 1982; Rajagopalan 1998; Tabas 2004; Tack 2006a; Talley 2008a; Vahedi 2005; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991). One study was rated as unclear for this item (Boerner 1988).

Effects of interventions

Bulking agents

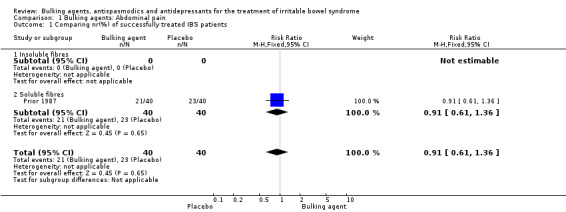

Improvement of abdominal pain (outcome 1) One study with a total of 80 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain. The RR was 0.91 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.36) using a fixed‐effect model. A planned subgroup analysis for insoluble compared to soluble bulking agents could not be performed because there was only one study with soluble (Prior 1987) bulking agents.

Four studies with a total of 186 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain. Two of these studies did not report sufficient data to calculate a SMD (Fowlie 1992; Rees 2005). One study of an insoluble bulking agent with a total of 56 patients remained (Aller 2004). There was one study of a soluble fibre (Longstreth 1981). The pooled SMD was 0.03 (95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.40) using a fixed‐effect model.

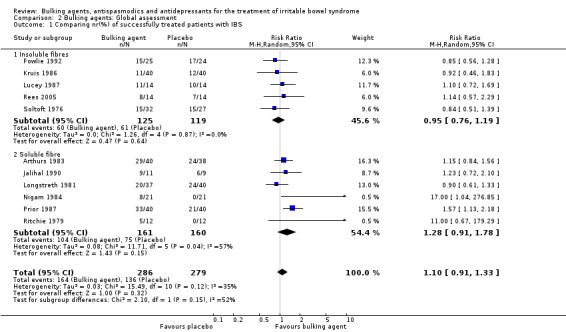

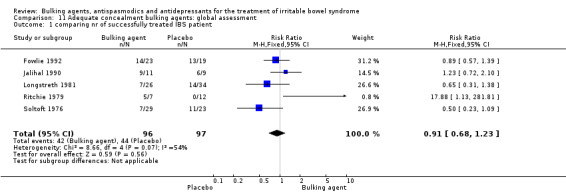

Improvement of global assessment (outcome 2) Eleven studies, with a total of 565 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of global assessment. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P = 0.12). The pooled relative risk was not statistically significant using a random‐effects model (RR 1.10; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.33). A RR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.19) was calculated for the studies using an insoluble bulking agent (244 patients) (Fowlie 1992; Kruis 1986; Lucey 1987; Rees 2005; Soltoft 1976). In the six studies with a soluble bulking agent the RR was 1.28 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.78; 321 patients) (Arthurs 1983; Jalihal 1990; Longstreth 1981; Nigam 1984; Prior 1987; Ritchie 1979).

One study of an insoluble bulking agent, comprising 56 patients, reported a continuous outcome for improvement of global assessment (Aller 2004). The standardized mean difference was not statistically significant (SMD ‐0.22; 95% CI ‐0.74 to 0.31).

Improvement of IBS symptom score (outcome 3) Three studies, with a total of 126 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of IBS symptom score. One study did not report sufficient data to calculate a SMD (Fowlie 1992). Two studies, both of insoluble fibre, with a total of 84 patients remained (Aller 2004; Fowlie 1992). The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P = 0.16). The pooled SMD was not statistically significant (SMD 0.00; 95%CI ‐0.43 to 0.43).

The main results for the bulking agents studies are summarized in additional Table 1.

1. Bulking agents: main results.

|

Dichotomous outcomes RR (95% CI) |

Continuous outcomes SMD (95% CI) |

|

| Abdominal pain | 0.91 (0.61 to 1.36) | 0.03 (‐0.34 to 0.40) |

| Global assessment | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.35) | |

| Symptom score | 0.00 (‐0.43 to 0.43) |

Antispasmodics

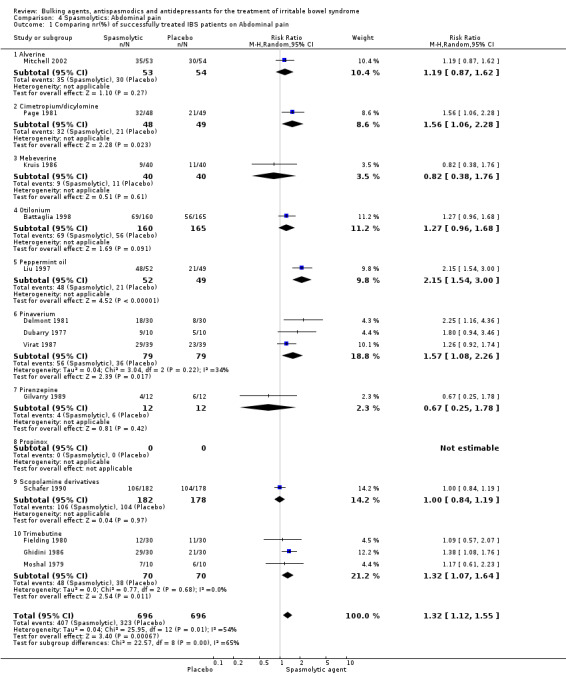

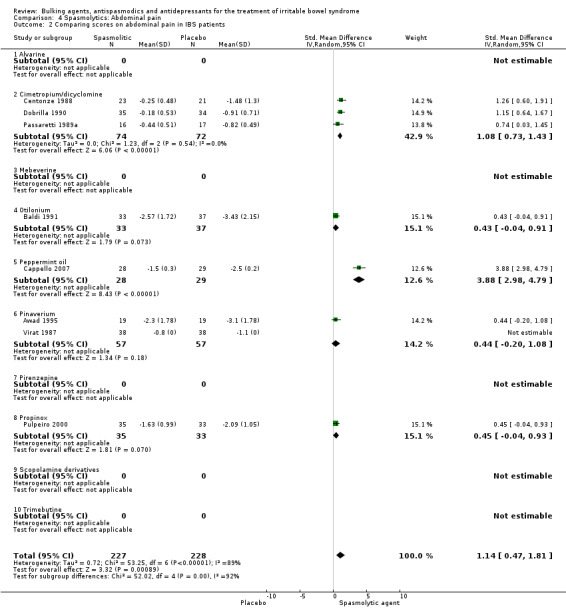

Improvement of abdominal pain (outcome 4) Thirteen studies with a total of 1392 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P = 0.01). The pooled RR was 1.32 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.55) using a random‐effects model. Subgroup analyses showed statistically significant benefit for pinaverium bromide (RR 1.57; 95% CI 1.08 to 2.26; 158 patients) (Delmont 1981; Dubarry 1977; Virat 1987) and trimebutine (RR 1.32; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.64; 140 patients) (Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986; Moshal 1979). There was no statistically significant benefit for scopolamine derivatives (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.19; 360 patients) (Page 1981; Schafer 1990). The other subgroups contained only one study each. Eight studies comprising 455 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P < 0.00001) The pooled SMD was 1.14 (95% CI 0.47 to 1.81) using a random‐effects model. Statistically significant benefit was present for the subgroup cimetropium/dicyclomine (SMD 1.08; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.43; 146 patients) (Centonze 1988; Dobrilla 1990; Passaretti 1989a). There was no statistically significant benefit for pinaverium (SMD 0.44; 95% CI ‐0.20 to 1.08; 114 patients) (Awad 1995; Virat 1987). The other subgroups contained none or only one study each.

Improvement of global assessment (outcome 5) Twenty‐two studies with a total of 1983 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of global assessment. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). The pooled relative risk was statistically significant (RR 1.49; 95% CI 1.25 to 1.77) using a random‐effects model. Statistically significant benefit was present for the subgroups cimetropium/dicyclomine (RR 1.78; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.75; 255 patients) (Centonze 1988; Dobrilla 1990; Page 1981; Passaretti 1989a), otilonium (RR 1.79; 95% CI 1.31 to 2.44; 363 patients) (Battaglia 1998; d'Arienzo 1980; Piai 1979); peppermint‐oil (RR 2.25; 95% CI 1.70 to 2.98; 225 patients) (Capanni 2005; Lech 1988) and pinaverium bromide (RR 1.66; 95% CI 1.25 to 2.19; 308 patients) (Chen 2004; Delmont 1981; Levy 1977; Virat 1987). There was no statistically significant benefit for alverine (RR 1.20; 95% CI 0.80 to 1.80; 107 patients) (Mitchell 2002); mebeverine (RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.16 to 1.07; 80 patients) (Kruis 1986), scolpamine derivates (RR 4.43; 95% CI 0.47 to 41.67; 426 patients) (Nigam 1984; Ritchie 1979; Schafer 1990) and trimebutine (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.38; 120 patients) (Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986).

Two studies comprising 331 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of global assessment. The pooled SMD could not be estimated because of lack of data provided by the studies (Battaglia 1998; Delmont 1981).

Improvement of IBS symptom score (outcome 6) Four studies with a total of 586 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of IBS symptom score. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P = 0.004). The pooled relative risk was statistically significant (RR 1.86; 95% CI 1.26 to 2.76) using a random‐effects model. Statistically significant benefit was present for the subgroups peppermint‐oil (RR 1.94; 95% CI 1.09 to 3.46; 269 patients) (Capanni 2005; Cappello 2007; Czalbert 1990) and otilonium (RR 1.64; 95% CI 1.15 to 2.34; 317 patients) (Battaglia 1998). Four studies comprising 243 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of global assessment. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P = 0.00001). The pooled SMD was statistically significant (SMD 2.39; 95% CI 0.50 to 4.29) using a random‐effects model. A statistically significant benefit was found for the pinaverium subgroup (SMD 0.51; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.84; 158 patients) (Awad 1995; Chen 2004). The other subgroups contained none or only one study each.

The main results for antispasmodics are summarized in additional Table 2.

2. Antispasmodics: main results.

|

Dichotomous outcomes RR (95% CI) |

Continuous outcomes SMD (95% CI) |

|

| Abdominal pain | 1.32 (1.12 to 1.55) | 1.14 (0.47 to 1.81) |

| Global assessment | 1.49 (1.25 to 1.77) | |

| Symptom score | 1.86 (1.26 to 2.76) | 2.39 (0.50 to 4.29) |

Individual spasmolytic agents: Cimetropium/dicyclomine No statistically significant effect for improvement of abdominal pain was found for Cimetropium/dicyclomine (SMD 1.08; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.43; 146 patients) (Centonze 1988; Dobrilla 1990; Passaretti 1989a). A statistically significant effect for improvement of global assessment was found for Cimetropium/dicyclomine (RR 1.88; 95% CI 1.04 to 3.42; 255 patients) (Centonze 1988; Dobrilla 1990; Page 1981; Passaretti 1989a). Mebeverine No statistically significant effect for improvement of global assessment was found for Mebeverine (RR 0.83; 95% CI 0.31 to 2.23; 149 patients) (Kruis 1986). Peppermint oil A statistically significant effect for improvement of global assessment was found for peppermint oil (RR 2.25; 95% CI 1.70 to 2.98; 225 patients) (Capanni 2005; Lech 1988). A statistically significant effect for improvement of IBS symptom score was found for peppermint oil (RR 1.94; 95% CI 1.09 to 3.46; 269 patients) (Capanni 2005; Cappello 2007; Czalbert 1990). Pinaverium Pinaverium provided a statistically significant benefit for improvement of abdominal pain, RR 1.57 (95% CI 1.08 to 2.26; 158 patients) (Delmont 1981; Dubarry 1977; Virat 1987) and SMD 0.44 (95% CI ‐0.20 to 1.08; 114 patients) (Awad 1995; Virat 1987). A statistically significant effect for improvement of global assessment, RR1.87 (95% CI1.41 to 2.48; 308 patients) (Chen 2004; Delmont 1981; Levy 1977; Virat 1987) and IBS‐symptom score was also found, SMD 0.51 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.84; 158 patients) (Awad 1995; Chen 2004). Scopolamine derivatives No statistically significant effect for improvement of global assessment was found for Scopolamine derivatives (RR 1.42; 95% CI 0.94 to 2.14; 442 patients) (Nigam 1984; Ritchie 1979; Schafer 1990).

Trimebutine A statistically significant effect for improvement of abdominal pain was found for Trimebutine (RR 1.32; 95% CI 1.07 to 1.64; 140 patients) (Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986; Moshal 1979). No statistically significant effect for improvement of global assessment (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.38; 120 patients) (Fielding 1980; Ghidini 1986). Other subgroups There was not enough data to calculate a pooled estimate effect.

Antidepressants

Improvement of abdominal pain (outcome 7) Eight studies with a total of 517 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P = 0.01). The pooled relative risk was statistically significant (RR was 1.49; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.12) using a random‐effects model. Subgroup analyses showed no benefit for SSRIs (RR 2.29; 95% CI 0.79 to 6.68; 197 patients) (Kuiken 2003; Tabas 2004; Tack 2006a; Vahedi 2005), and a statistically significant benefit for TCAs (RR 1.26; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.55; 320 patients) (Drossman 2003; Heefner 1978; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991).

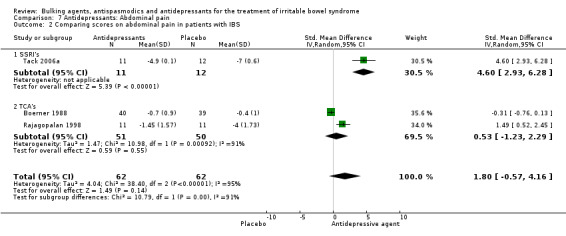

Three studies with a total of 124 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P < 0.00001). The pooled RR was 1.80 (95% CI ‐0.57 to 4.16). Subgroup analyses showed no significant benefit for TCA’s (SMD was 0.53; 95% CI ‐1.23 to 2.29; 101 patients) (Boerner 1988; Drossman 2003; Rajagopalan 1998).

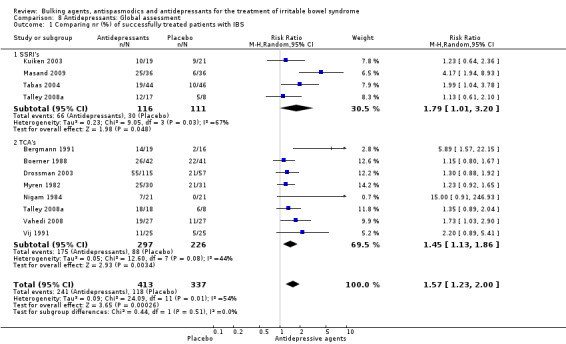

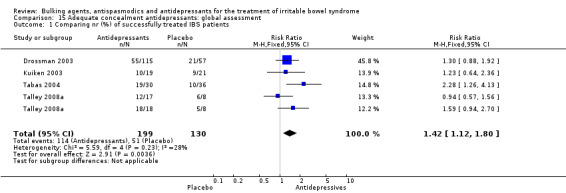

Improvement of global assessment (outcome 8) Twelve studies, with a total of 750 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of global assessment. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P = 0.01). The pooled relative risk was statistically significant (RR 1.57; 95% CI 1.23 to 2.00) using a random‐effects model. Subgroup analyses suggest a benefit for SSRIs (RR 1.79; 95% CI 1.01 to 3.20; P = 0.05; 227 patients) (Kuiken 2003; Masand 2009; Tabas 2004; Talley 2008a) and showed a statistically significant benefit for TCAs (RR 1.45; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.86; 523 patients) (Bergmann 1991; Boerner 1988; Drossman 2003; Myren 1982; Nigam 1984; Talley 2008a; Vahedi 2008; Vij 1991).

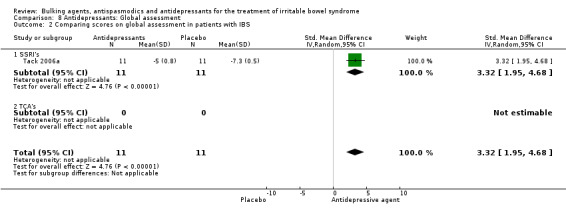

One study assessing an SSRI (Tack 2006a), with a total of 22 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of global assessment. The pooled SMD was 3.32 (95% CI 1.95 to 4.68).

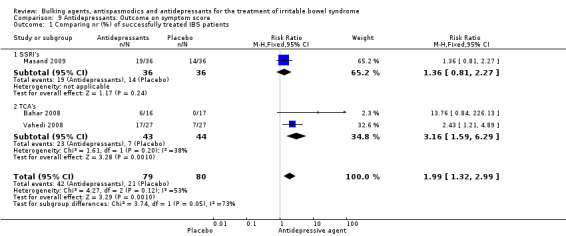

Improvement of IBS symptom score (outcome 9) Three studies with a total of 159 patients reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of symptom score. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P = 0.12). The pooled RR was 1.99 (95% CI 1.32 to 2.99) using a fixed‐effect model. Subgroup analyses showed a statistically significant benefit for TCAs (RR 3.16; 95% CI 1.59 to 6.29; 87 patients) (Bahar 2008; Vahedi 2008).

Two studies, with a total of 122 patients reported a continuous outcome for improvement of IBS symptom score. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P = 0.07). The pooled SMD was 0.38 (95% CI ‐0.30 to 1.06) using a random‐effects model.

The main results for antidepressants are summarized in Table 3.

3. Antidepressants: main results.

|

Dichotomous outcomes RR (95% CI) |

Continuous outcomes SMD (95% CI) |

|

| Abdominal pain | 1.49 (1.05 to 2.12) | 1.80 (‐0.57 to 4.16) |

| Global assessment | 1.57 (1.23 to 2.00) | 3.32 (1.95 to 4.68) |

| Symptom score | 1.99 (1.32 to 2.99) | 0.38 (‐0.30 to 1.06) |

Additional comparison: adequate concealment of allocation

Bulking agents abdominal pain (outcome 10.2) Two studies of bulking agents with adequate concealment of allocation reported a continuous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain (Longstreth 1981; Fowlie 1992). The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P = 0.88). The pooled SMD using a fixed‐effect model was ‐0.04 (95%CI ‐0.40 to 0.32; 119 patients).

Bulking agents: global assessment (outcome 11.1) Five studies of bulking agents with adequate concealment of allocation reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain (Fowlie 1992; Jalihal 1990; Longstreth 1981; Ritchie 1979; Soltoft 1976). Using a random‐effects model, the pooled RR was 0.91 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.23; 193 patients).

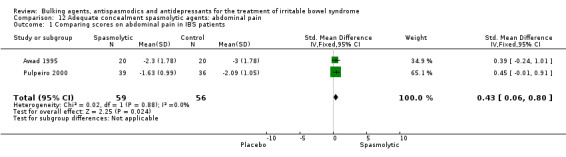

Antispasmodics: abdominal pain (outcome 12.1) Two studies of spasmolytic agents with adequate concealment of allocation reported a continuous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain (Awad 1995; Pulpeiro 2000). The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P = 0.88). Using a fixed‐effect model, the pooled SMD was 0.43 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.80; 115 patients).

Antispasmodics: global assessment (outcome 13.1) Three studies of spasmolytic agents with adequate concealment of allocation reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of global assessment (Chen 2004; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979). The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P= 0.25). Using a fixed‐effect model, the pooled RR was 1.35 (95% CI 0.85 to 2.12; 219 patients).

Antidepressants: abdominal pain (outcome 14.1) Five studies of antidepressant agents with adequate concealment of allocation reported a dichotomous outcome for improvement of abdominal pain. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (P = 0.06). Using a random‐effects model, the pooled RR was 1.35 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.86; 364 patients) . Subgroup analyses showed no statistically significant benefit for SSRIs (RR 1.20; 95% CI 0.87 to 1.67) (Kuiken 2003; Tabas 2004; Vahedi 2005) or TCAs (RR 2.19; 95% CI 0.59 to 8.11) (Drossman 2003; Vahedi 2008).

Antidepressants: global assessment (outcome 15.1) Four studies of antidepressant agents with adequate concealment of allocation reported a dichotomous outcome for global assessment. The chi‐square test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P = 0.23). Using a fixed‐effect model, the pooled RR was 1.42 (95% CI 1.12 to 1.80; 329 patients) (Drossman 2003; Kuiken 2003; Tabas 2004; Talley 2008a).

Antidepressants: IBS symptom score (outcome 16.1) One study of antidepressants with adequate concealment of allocation reported a continuous outcome for improvement of IBS symptom score (Vahedi 2008). Using a fixed‐effect model, the SMD was 0.75 (95% CI 0.17 to 1.32; 50 patients).

Discussion

Bulking agents The pooled data suggest that bulking agents do not provide any benefit for the treatment of IBS. No statistically significant differences between bulking agents and placebo were found for abdominal pain, global assessment or symptom score. Only 7 of the included studies had more than 30 patients and all studies had quality limitations (i.e. method of randomisation, double‐blinding, concealment of treatment allocation, description of withdrawals). There were five studies with adequate allocation concealment (Fowlie 1992; Jalihal 1990; Longstreth 1981; Ritchie 1979; Soltoft 1976). A sensitivity analysis of those studies with adequate allocation concealment, did not change the results. Subgroup analyses for the different type of bulking agents, soluble versus insoluble fibre, also gave no statistically significant findings.

We are aware of five systematic reviews of bulking agents for IBS. Jailwala 2000, who used less strict exclusion criteria than the present review, also concluded from an analysis of 13 studies that the efficacy of bulking agents is not clearly established. When Jailwala 2000 separately analysed high and low quality trials, the conclusion remained the same (Jailwala 2000). Akehurst 2001 included 7 studies on bulking agents in a review of IBS therapies and concluded that there was little reason to believe that bulking agents were effective for IBS (Akehurst 2001). Lesbros‐Pantoflickova 2004 included 13 studies in their meta‐analyses, of which 5 studies reported a statistically significant benefit of fibre treatment for the relief of global symptoms (OR 1.9; 95% CI 1.5 to 2.4). However, after exclusion of the low‐quality trials, this effect was not statistically significant. In conclusion, they found no evidence to recommend bulking agents for the treatment of IBS (Lesbros‐Pantoflickova 2004). Ford 2008 included 12 studies comparing fibre with placebo, and used persistent symptoms after treatment as an outcome measure. Ford 2008 calculated a RR of 0.87 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.00). A subgroup analysis identified a statistically significant benefit for ispaghula a soluble fibre (RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.63 to 0.96). Ford 2008 had almost the same strict inclusion criteria as our review but included different outcome analyses. Ford 2008 did not use an ITT‐analyses, only extracted dichotomous outcome and pooled all the outcomes (global assessment of symptoms and abdominal pain) as one. Bijkerk 2004 examined the separate effects of soluble and insoluble fibres, on global assessment and constipation. Bijkerk 2004 found a beneficial overall effect for fibre in general (RR 1.33; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.50) and soluble fibres for global assessment of IBS (RR 1.55; 95% CI 1.35 to 1.78). We could not reproduce these findings (outcomes 1.1 to 3.2). A possible explanation for this is that Bijkerk 2004 included cross‐over trials (7 of the 17 included studies), which were excluded in this review. Bijkerk 2004 also included two studies with no placebo comparison.

Antispasmodics Spasmolytic agents compared to placebo provided a statistically significant benefit for abdominal pain, global assessment and IBS‐symptom score. Spasmolytic agents are pharmacologically diverse and arbitrary choices were made regarding the pooling of results. We decided to treat peppermint‐oil as an anti‐spasmodic because of its known effect on smooth muscles. Trimebutine appears to be effective for abdominal pain, pinaverium for abdominal pain and global assessment, cimetropium/dicyclominand for global assessment and peppermint‐oil for global assessment and symptom score. Only four studies had adequate allocation concealment (Awad 1995; Chen 2004; Pulpeiro 2000; Ritchie 1979). It is important to note that none of the studies involving peppermint‐oil had adequate allocation concealment. When analysing the studies with adequate allocation concealment separately, the results get weaker and only improvement of abdominal pain has still a statistically significant benefit. Spasmolytics are extensively studied for their use in the treatment of IBS, however due to the diversity of types of spasmolytic agents, the number of studies for each compound are limited. Therefore most subgroups could not be pooled, and a type II error could have occurred.

Eight systematic reviews of antispasmodics for IBS have been published (Akehurst 2001; Brandt 2002; Ford 2008; Jailwala 2000; Lesbros‐Pantoflickova 2004; Poynard 1994; Poynard 2001; Tack 2006b). Jailwala 2000 included 13 studies and found that all of the 7 high‐quality trials demonstrated a benefit, mainly for abdominal pain, less so for constipation. Akehurst 2001 identified 12 studies and came to similar conclusions. Ford 2008 found consistent evidence of efficacy for otilonium (RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.31 to 0.97) and scopolamine (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.78). Ford 2008 identified peppermint‐oil as an individual group, included 4 studies and calculated a RR of 0.43 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.59). These results are almost identical to our own. However, Ford 2008 used a different method to assess methodological quality (Jadad scale), and rated three studies as high quality, resulting in a greater effect than seen in this review. In an update of a 1994 meta‐analysis, Poynard 2001 included 23 trials comprising 6 types of drugs. Using a fixed‐effect model, there was a statistically significant benefit for global assessment (Peto OR 2.13; 95%CI 1.77 to 2.58) and pain (Peto OR 1.65; 95%CI 1.30 to 2.10) (Poynard 2001).This review provides similar evidence of the efficacy of spasmolytic agents for IBS. The reviews from Lesbros‐Pantoflickova 2004 and Tack 2006b concluded that there is some evidence that antispasmodic may improve symptoms of abdominal pain but are careful in recommending antispasmodics for the treatment of IBS due to the low methodological quality of the included RCTs.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants provide a statistically significant benefit over placebo for abdominal pain, global assessment and IBS‐symptom score. Subgroup analyses for SSRIs and TCAs, showed a statistically significant improvement in global assessment for SSRIs and a statistically significant improvement in abdominal pain and symptom score for TCAs. A sensitivity analysis of the six studies with adequate allocation concealment showed a statistically significant benefit for improvement of symptom score and global assessment (Drossman 2003; Kuiken 2003; Tabas 2004; Talley 2008a; Vahedi 2005; Vahedi 2008).

Given the significantly positive effects of antidepressant medication, the clinical indication of antidepressant medication in IBS needs to be discussed. Careful examination of the domain descriptions in the individual studies, shows no differences in patient population between studies investigating antidepressants, antispasmodics or bulking agents. Two studies performed a direct comparison of antidepressants with bulking agents or antispasmodics (Nigam 1984; Ritchie 1979), but found no proof of the superiority of either compound.

We are aware of eight systematic reviews of antidepressants for IBS (Akehurst 2001; Brandt 2002; Ford 2009; Jailwala 2000; Jackson 2000; Lesbros‐Pantoflickova 2004; Tack 2006b; Rahimi 2009). Most of these reviews are consistent with our results. Akehurst 2001 concluded from two studies that antidepressants were effective. Ford 2009 included 13 RCTs and found a RR of 0.66 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.78) for persistent symptoms after treatment, and no difference between SSRIs and TCAs. The Jailwala 2000 meta‐analysis included 7 studies, all reporting beneficial effect, and concluded that it was not clear whether this was due to resolving abdominal symptoms, or to improved psychological health. The Jackson 2000 review included 11 studies on functional gastro‐intestinal disorders, 8 of which were enrolled IBS patients exclusively. Jackson 2000 identified a statistically significant effect for overall assessment (7 studies; OR 4.2; 95% CI 2.3 to 7.9) and abdominal pain (9 studies; SMD 0.9; 95% CI 0.6 to 1.2). The Lesbros‐Pantoflickova 2004 review included 12 studies and found an OR: 2.6 (95% CI 1.9 to 3.5). They recommend antidepressant medication for the treatment of patients with severe IBS symptoms, i.e. patients with daily or persistent pain. Rahimi 2009 only investigated TCAs and found clinically and statistically significant control of IBS symptoms. They advised that treatment with TCAs should be limited to patients with moderate to severe IBS.

Brandt 2002 and Tack 2006b (a extended version of Brandt 2002) reported no beneficial effect for antidepressant medication. This difference may be due to less strict inclusion criteria: both included cross‐over studies with no report of the first phase data. They also failed to conduct a meta‐analysis of the data.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The limitations of drug therapy should be discussed with the patient before deciding to prescribe medication for IBS. Agreement should be reached on treatment objectives, usually this will be relief of the most troublesome symptom. Our findings support the use of antispasmodics, although, it is not entirely clear whether one antispasmodic is more effective than another. Physicians will be limited to those antispasmodics which are locally available.

Antidepressants may also have a role for the treatment of IBS. Antidepressants could be used in patients who seek drug therapy and who have not responded to antispasmodics. The effectiveness of antidepressants may vary with individual patient features.

Implications for research.

It is likely that two different disease entities exist: constipation predominant IBS, and diarrhea predominant IBS. There may even be a third entity, patients with an alternating stool pattern. The pharmacological properties of bulking agents, spasmolytic agents and antidepressive medication suggest that different responses might be expected in these patient groups and this issue should be studied in future trials of “classic” drugs.

The variation in methods of outcome assessment in IBS studies is a validity problem. It is uncertain how precisely current outcome measures reflect the actual health status of the IBS patient. The need for more meaningful measures of response to treatment has led to the development of health‐related quality of life measures including stool frequency and consistency, social, daily, physical and sexual functioning, sleep, pain, emotion, and change of health. Future research should use validated outcome measures for IBS, such as the IBS Quality of Life Questionnaire (IBSQOL), the IBS Quality of Life Measure (IBS‐QOL), the Digestive Health Status Instrument (DHSI), the Functional Digestive Disorder Quality of Life questionnaire (FDDQOL), or the IBS‐Q.

The concept of the brain‐gut axis invites trials aimed at central and peripheral neural levels; apart from drug trials these may include cognitive behavioural therapy or other psychological interventions (e.g. hypnotherapy).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 February 2013 | Amended | Correction of minor errors in additional tables |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2002 Review first published: Issue 2, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 September 2011 | Amended | Change in address for contact author |

| 26 April 2011 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Change in authors, conclusions changed due to new data |

| 26 April 2011 | New search has been performed | New search, new studies included |

Acknowledgements

Funding for the IBD/FBD Review Group (September 1, 2010 ‐ August 31, 2015) has been provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Knowledge Translation Branch (CON ‐ 105529) and the CIHR Institutes of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD); and Infection and Immunity (III).

Miss Ila Stewart has provided support for the IBD/FBD Review Group through the Olive Stewart Fund.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Bulking agents: Abdominal pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated IBS patients | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.61, 1.36] |

| 1.1 Insoluble fibres | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 Soluble fibres | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.61, 1.36] |

| 2 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in IBS patients | 4 | 186 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.34, 0.40] |

| 2.1 Insoluble fibres | 3 | 126 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [‐0.52, 0.52] |

| 2.2 Soluble fibres | 1 | 60 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.45, 0.57] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bulking agents: Abdominal pain, Outcome 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated IBS patients.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bulking agents: Abdominal pain, Outcome 2 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in IBS patients.

Comparison 2. Bulking agents: Global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated patients with IBS | 11 | 565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.91, 1.33] |

| 1.1 Insoluble fibres | 5 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.76, 1.19] |

| 1.2 Soluble fibre | 6 | 321 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.91, 1.78] |

| 2 Comparing scores on global assessment in IBS patients | 1 | 56 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.74, 0.31] |

| 2.1 Insoluble fibres | 1 | 56 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.22 [‐0.74, 0.31] |

| 2.2 Soluble fibres | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Bulking agents: Global assessment, Outcome 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated patients with IBS.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Bulking agents: Global assessment, Outcome 2 Comparing scores on global assessment in IBS patients.

Comparison 3. Bulking agents: Outcome on symptom score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing symptom scores in IBS patients | 3 | 126 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.43, 0.43] |

| 1.1 Insoluble fibres | 3 | 126 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.00 [‐0.43, 0.43] |

| 1.2 Soluble fibres | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Bulking agents: Outcome on symptom score, Outcome 1 Comparing symptom scores in IBS patients.

Comparison 4. Spasmolytics: Abdominal pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated IBS patients on Abdominal pain | 13 | 1392 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.12, 1.55] |

| 1.1 Alverine | 1 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.87, 1.62] |

| 1.2 Cimetropium/dicylomine | 1 | 97 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.56 [1.06, 2.28] |

| 1.3 Mebeverine | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.38, 1.76] |

| 1.4 Otilonium | 1 | 325 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.27 [0.96, 1.68] |

| 1.5 Peppermint oil | 1 | 101 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.15 [1.54, 3.00] |

| 1.6 Pinaverium | 3 | 158 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.08, 2.26] |

| 1.7 Pirenzepine | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.25, 1.78] |

| 1.8 Propinox | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.9 Scopolamine derivatives | 1 | 360 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.84, 1.19] |

| 1.10 Trimebutine | 3 | 140 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.32 [1.07, 1.64] |

| 2 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in IBS patients | 8 | 455 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.47, 1.81] |

| 2.1 Alvarine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Cimetropium/dicyclomine | 3 | 146 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.73, 1.43] |

| 2.3 Mebeverine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.4 Otilonium | 1 | 70 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.43 [‐0.04, 0.91] |

| 2.5 Peppermint oil | 1 | 57 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.88 [2.98, 4.79] |

| 2.6 Pinaverium | 2 | 114 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.44 [‐0.20, 1.08] |

| 2.7 Pirenzepine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.8 Propinox | 1 | 68 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.45 [‐0.04, 0.93] |

| 2.9 Scopolamine derivatives | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.10 Trimebutine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Spasmolytics: Abdominal pain, Outcome 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated IBS patients on Abdominal pain.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Spasmolytics: Abdominal pain, Outcome 2 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in IBS patients.

Comparison 5. Spasmolytics: Global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated patients | 22 | 1983 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.49 [1.25, 1.77] |

| 1.1 Alverine | 1 | 107 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.80, 1.80] |

| 1.2 Cimtetropium/dicyclomine | 4 | 255 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.78 [1.15, 2.75] |

| 1.3 Mebeverine | 1 | 80 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.16, 1.07] |

| 1.4 Otilonium | 3 | 363 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.79 [1.31, 2.44] |

| 1.5 Peppermint oil | 2 | 225 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.25 [1.70, 2.98] |

| 1.6 Pinaverium | 4 | 308 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.66 [1.25, 2.19] |

| 1.7 Pirenzepine | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.83 [0.35, 2.00] |

| 1.8 Propinox | 1 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.77 [0.26, 2.30] |

| 1.9 Scopolamine derivatives | 3 | 426 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 4.43 [0.47, 41.67] |

| 1.10 Trimebutine | 2 | 120 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.68, 1.38] |

| 2 Comparing scores on global assessment in IBS patients | 2 | 331 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.1 Alvarine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Cimetropium/dicyclomine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.3 Mebeverine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.4 Otilonium | 1 | 271 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.5 Peppermint oil | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.6 Pinaverium | 1 | 60 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.7 Pirenzepine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.8 Propinox | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.9 Scopolamine derivatives | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.10 Trimebutine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Spasmolytics: Global assessment, Outcome 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated patients.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Spasmolytics: Global assessment, Outcome 2 Comparing scores on global assessment in IBS patients.

Comparison 6. Spasmolytics: Outcome on symptom score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr (%) of patients successfully treated | 4 | 586 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.86 [1.26, 2.76] |

| 1.1 Alvarine | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 Cimetropium/dicyclomine | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 Mebeverine | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.4 Otilonium | 1 | 317 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.64 [1.15, 2.34] |

| 1.5 Peppermint oil | 3 | 269 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.94 [1.09, 3.46] |

| 1.6 Pinaverium | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.7 Pirenzepine | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.8 Propinox | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.9 Scopolamine derivatives | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.10 Trimebutine | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Comparing symptom scores in IBS patients | 4 | 243 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.39 [0.50, 4.29] |

| 2.1 Alvarine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 Cimetropium/dicyclomine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.3 Mebeverine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.4 Otilonium | 1 | 28 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.20 [‐0.55, 0.94] |

| 2.5 Peppermint oil | 1 | 57 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 9.86 [7.92, 11.81] |

| 2.6 Pinaverium | 2 | 158 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.19, 0.84] |

| 2.7 Pirenzepine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.8 Propinox | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.9 Scopolamine derivatives | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.10 Trimebutine | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Spasmolytics: Outcome on symptom score, Outcome 1 Comparing nr (%) of patients successfully treated.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Spasmolytics: Outcome on symptom score, Outcome 2 Comparing symptom scores in IBS patients.

Comparison 7. Antidepressants: Abdominal pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated patients with IBS | 8 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.49 [1.05, 2.12] |

| 1.1 SSRI's | 4 | 197 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.29 [0.79, 6.68] |

| 1.2 TCA's | 4 | 320 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.26 [1.03, 1.55] |

| 2 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in patients with IBS | 3 | 124 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.80 [‐0.57, 4.16] |

| 2.1 SSRI's | 1 | 23 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 4.60 [2.93, 6.28] |

| 2.2 TCA's | 2 | 101 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.53 [‐1.23, 2.29] |

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antidepressants: Abdominal pain, Outcome 1 Comparing nr(%) of successfully treated patients with IBS.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Antidepressants: Abdominal pain, Outcome 2 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in patients with IBS.

Comparison 8. Antidepressants: Global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated patients with IBS | 11 | 750 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.23, 2.00] |

| 1.1 SSRI's | 4 | 227 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.79 [1.01, 3.20] |

| 1.2 TCA's | 8 | 523 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.45 [1.13, 1.86] |

| 2 Comparing scores on global assessment in patients with IBS | 1 | 22 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.32 [1.95, 4.68] |

| 2.1 SSRI's | 1 | 22 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.32 [1.95, 4.68] |

| 2.2 TCA's | 0 | 0 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antidepressants: Global assessment, Outcome 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated patients with IBS.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Antidepressants: Global assessment, Outcome 2 Comparing scores on global assessment in patients with IBS.

Comparison 9. Antidepressants: Outcome on symptom score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated IBS patients | 3 | 159 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.99 [1.32, 2.99] |

| 1.1 SSRI's | 1 | 72 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.36 [0.81, 2.27] |

| 1.2 TCA's | 2 | 87 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.16 [1.59, 6.29] |

| 2 Comparing symptom scores of IBS patients | 2 | 122 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐0.30, 1.06] |

| 2.1 SSRI's | 1 | 72 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐0.41, 0.52] |

| 2.2 TCA's | 1 | 50 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.17, 1.32] |

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antidepressants: Outcome on symptom score, Outcome 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated IBS patients.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Antidepressants: Outcome on symptom score, Outcome 2 Comparing symptom scores of IBS patients.

Comparison 10. Adequate concealment bulking agents: abdominal pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing scores on abdominal pain | 2 | 119 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.04 [‐0.32, 0.40] |

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Adequate concealment bulking agents: abdominal pain, Outcome 1 Comparing scores on abdominal pain.

Comparison 11. Adequate concealment bulking agents: global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 comparing nr of successfully treated IBS patient | 5 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.68, 1.23] |

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Adequate concealment bulking agents: global assessment, Outcome 1 comparing nr of successfully treated IBS patient.

Comparison 12. Adequate concealment spasmolytic agents: abdominal pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in IBS patients | 2 | 115 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.06, 0.80] |

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Adequate concealment spasmolytic agents: abdominal pain, Outcome 1 Comparing scores on abdominal pain in IBS patients.

Comparison 13. Adequate concealment spasmolytic agents: global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 comparing nrs of successfully treated IBS patients with spasmolytic agents | 3 | 219 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.85, 2.12] |

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Adequate concealment spasmolytic agents: global assessment, Outcome 1 comparing nrs of successfully treated IBS patients with spasmolytic agents.

Comparison 14. Adequate concealment antidepressants: abdominal pain.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated patients | 5 | 364 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.98, 1.86] |

| 1.1 SSRI | 3 | 156 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.87, 1.67] |

| 1.2 TCA | 2 | 208 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.19 [0.59, 8.11] |

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Adequate concealment antidepressants: abdominal pain, Outcome 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated patients.

Comparison 15. Adequate concealment antidepressants: global assessment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated IBS patients | 4 | 329 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [1.12, 1.80] |

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Adequate concealment antidepressants: global assessment, Outcome 1 Comparing nr (%) of successfully treated IBS patients.

Comparison 16. Adequate concealment antidepressants: Outcome on symptom score.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Comparing symptom scores in IBS patients | 1 | 50 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.17, 1.32] |

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Adequate concealment antidepressants: Outcome on symptom score, Outcome 1 Comparing symptom scores in IBS patients.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Aller 2004.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 56 patients Rome II criteria 53% diarrhea‐predominant Setting unclear Mean age 46 years 67% female |

|

| Interventions | Bulking agent 30 g fibre of which 25 g insoluble, over the day for 13 weeks |

|

| Outcomes | Abdominal pain, continuous Symptom score, continuous |

|

| Notes | Half a week run‐in | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Single‐blind ‐ not described in detail |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No patients dropped out of the study |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Arthurs 1983.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 80 patients Setting unclear Diagnostic criteria not defined Mean age 27.7 years 78% female |

|

| Interventions | Bulking agent 4 weeks ispaghula husk 2 sachets/day | |

| Outcomes | Global assessment, dichotomous | |

| Notes | Unclear setting No run‐in | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Double‐blind but procedures not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Two dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Awad 1995.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 40 patients Tertiary care Rome criteria Mean age 31.3 years 100% female |

|

| Interventions | Spasmolytic pinaverium 50 mg od for 3 weeks | |

| Outcomes | Abdominal pain, continuous symptom score, continuous | |

| Notes | No run‐in | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Adequate |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blind, identical placebo, neither doctors nor patients knew which treatment was given |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Two dropouts one from each treatment group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Bahar 2008.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 33 adolescent patients secondary care Rome criteria mean age 15 years 65% female |

|

| Interventions | Antidepressant amitriptyline 10 to 30 mg dd for 8 weeks |

|

| Outcomes | Abdominal pain, change score (not included global assessment, change score ( not included) and dichotomous |

|

| Notes | 2 weeks run in period adolescents |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | 2 drop‐outs |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Baldi 1991.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 71 patients with IBS 8 GI centres Mean age 40 years 60.6% female |

|

| Interventions | Spasmolytic 4 weeks otilonium 40 mg tds | |

| Outcomes | abdominal pain | |

| Notes | 2 wk run‐in with placebo | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Double‐blind, methods not described |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | One drop‐out |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Battaglia 1998.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 325 patients multicentre GI outpatients Rome criteria Mean age 47.7 years 69% female |

|

| Interventions | Spasmolytic 15 weeks otilonium 40 mg tds | |

| Outcomes | abdominal pain, dichotomous global assessment, continuous | |

| Notes | 2 weeks run‐in, with placebo | |

| Risk of bias | ||