Abstract

Armillariella tabescens (Scop.) Sing., a mushroom of the family Tricholomataceae, has been used in traditional oriental medicine to treat cholecystitis, improve bile secretion, and regulate bile-duct pressure. The present study evaluated the estrogen-like effects of A. tabescens using a cell-proliferation assay in an estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cell line (MCF-7). We found that the methanol extract of A. tabescens fruiting bodies promoted cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells. Using bioassay-guided fractionation of the methanol extract and chemical investigation, we isolated and identified four steroids and four fatty acids from the active fraction. All eight compounds were evaluated by E-screen assay for their estrogen-like effects in MCF-7 cells. Among the tested isolates, only (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol promoted cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells; this effect was mitigated by the ER antagonist, ICI 182,780. The mechanism underlying the estrogen-like effect of (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol was evaluated using Western blot analysis to detect the expression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), Akt, and estrogen receptor α (ERα). We found that (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol induced an increase in phosphorylation of ERK, PI3K, Akt, and ERα. Together, these experimental results suggest that (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol is responsible for the estrogen-like effects of A. tabescens and may potentially aid control of estrogenic activity in menopause.

Keywords: Armillariella tabescens; (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol; phytoestrogens; estrogen receptor

1. Introduction

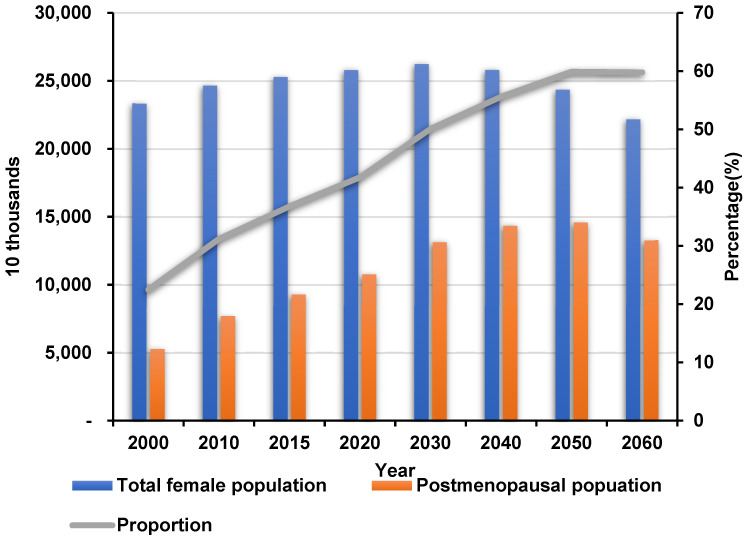

Menopause, the complete end of menstrual periods, typically occurs worldwide for women 45 to 55 years of age. With increasing life expectancy, the global number of menopausal women aged 50 years and over is estimated to reach 1.2 billion by 2030, with 47 million new entrants each year [1,2]. In South Korea, the postmenopausal female population aged over 50 years has increased since 2000. After 2030, over half of the female population will be postmenopausal (Figure 1), according to the Korean Statistical Information Service database [3]. Menopause results from declining ovarian function, and the production of steroid hormones such as estrogen dramatically drops. As a result, menopause results in such vasomotor symptoms as hot flushes, night sweats, sleep disturbance, vaginal dryness, and even osteoporosis [4]. Women experiencing menopausal symptoms have reported significantly reduced health-related quality of life; in the most severe cases, exogenous estrogens are prescribed [5].

Figure 1.

Transitions of the total female and postmenopausal female populations in South Korea. The total female population will peak in 2030 then decrease through to 2060. The postmenopausal female population will continuously increase. After 2030, over half of South Korean females will be postmenopausal [3].

Estrogen replacement therapy has traditionally been considered beneficial for the relief and prevention of postmenopausal symptoms and related diseases [6,7]. However, patients receiving estrogen replacement therapy over the long term are often reluctant to continue because of side effects including breast cancer, heart disease, and stroke [8,9]. Thus, there is growing interest in the use of phytoestrogens with estrogen-like activity. Phytoestrogens are natural compounds found in plants and plant-based foods and are structurally, and sometimes functionally, similar to mammalian estrogens and their active metabolites [10]. Phytoestrogens such as stilbenes, isoflavonoids, lignans, and flavonoids are reported to be abundant in red clover plants, flax seeds, and soy plants [11]. When phytoestrogens bind to the estrogen receptor (ER), they act as agonists or antagonists [12]. They are structurally similar to estrogen; in theory, therefore, they can increase the risk of breast cancer development [7]. However, some studies on the effects of phytoestrogens on breast cancer have suggested that phytoestrogens exhibit no effect on cancer or even exhibit anti-cancer effects [13].

Mycoestrogens, natural fungus-derived products with estrogen-like activity, can be produced by various Fusarium species [14]. Mycoestrogens have features similar to those of phytoestrogens and are reported to act as estrogen-receptor agonists [15]. Mushrooms—the fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting bodies of fungi—have been used as functional foods and dietary supplements because of various bioactive secondary metabolites that exhibit interesting biological actions [16]. As an example of the estrogen-like activity of a mushroom, the ethanol extract of the Pleurotus eryngii fruiting body is well documented to exhibit proliferative effects in ER-positive MCF-7 human breast epithelial cell lines and to promote ovariectomy-induced bone loss in old female rats [17]. However, the chemical contributors to the estrogen-like effects of P. eryngii have not yet been identified.

Our group has been conducting extended natural-product research to discover bioactive compounds from Korean wild mushrooms [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. In this context, we investigated potential bioactive compounds from a methanol (MeOH) extract of the fruiting bodies of Armillariella tabescens (Scop.) Sing. to show anti-gastritic activity against ethanol-induced gastric damage in rats. The previous study found that (Z,Z)-9,12-octadecadienoic acid, isolated from A. tabescens as a fatty acid, exhibited anti-inflammatory activity involved in anti-gastritic activity [23]. A. tabescens, belonging to the Tricholomataceae family, is known as the “Luminous Fungus” in China. This mushroom has been used in traditional medicine to treat cholecystitis, to regulate bile-duct pressure, and to improve liver function [26,27]. Previous studies of A. tabescens extracts have reported that the extracts exhibit antitumor and immunomodulatory activities [23,28,29]. However, few studies of A. tabescens have investigated its chemical constituents, despite the potential pharmacological applications. Previous chemical investigations of A. tabescens have reported armillarisins A and B, which exhibited biological activities including antifungal effects and anti-infection properties against gastritis and hepatitis [26,27]. In our ongoing research on A. tabescens, we found that the MeOH extract of the fruiting bodies of A. tabescens showed estrogen-like effects in the estrogen-receptor-positive MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The estrogen-like effect of A. tabescens has not previously been reported. Thus, the present study was conducted to further investigate the active MeOH extracts to identify potential mycoestrogens. Herein, we describe the isolation and structural characterization of eight compounds and evaluate their estrogen-like effects in MCF-7 cells; we also characterize the bioactivity of the active compound as a mycoestrogen.

2. Results

2.1. Bioactivity-Guided Fractionation of the MeOH Extract of A. tabescens

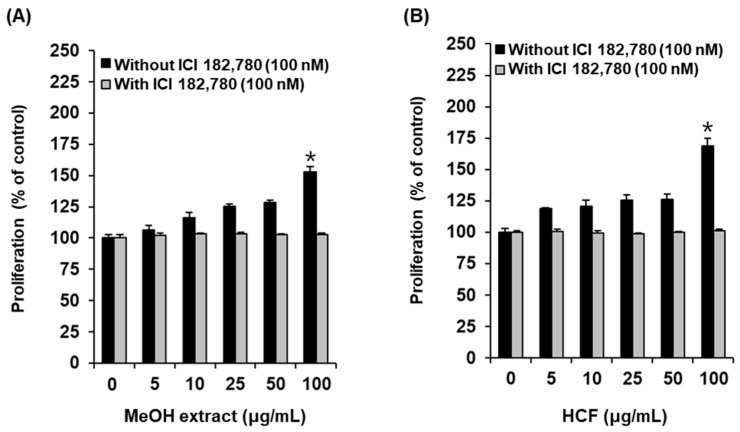

We examined MCF-7 cell proliferation after treatment with the MeOH extract of A. tabescens using Ez-Cytox reagents. Cell proliferation increased to 152.61 ± 4.73% after treatment, with 100 µg/mL of the MeOH extract compared with the untreated cells, and this effect was mitigated by ICI 182,780, an estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist (Figure 2A). Based on this result, the MeOH extract was successively solvent partitioned with hexane, CH2Cl2, EtOAc, and n-BuOH to give four main fractions: hexane-soluble, CH2Cl2-soluble, EtOAc-soluble, and n-BuOH-soluble. LC/MS and TLC analyses indicated that the hexane-soluble and CH2Cl2-soluble fractions had similar chemical profiles, which allowed us to consolidate the hexane- and CH2Cl2-soluble fractions, yielding the HCF for further experiments. For the bioactivity-guided fractionation of the MeOH extract, the estrogen-like effects of the three main fractions (HCF, EtOAc-soluble, and n-BuOH-soluble) were evaluated using a cell-proliferation assay to identify the active fraction. Of the fractions tested, cell proliferation increased to 169.01 ± 5.91% after treatment with the HCF fraction compared with the untreated cells, and this effect was mitigated by the ICI 182,780 (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Comparison of estrogenic activities of (A) MeOH extract and (B) hexane- and CH2Cl2-soluble fraction (HCF) in the absence or presence of ICI 182,780, as determined by cell proliferation measured by E-screen assay in MCF-7 cells. * Significant difference between untreated cells and cells treated with sample in the absence of ICI 182,780 (n = 3 independent experiments, p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test). Data are the mean ± SEM.

2.2. Isolation and Identification of Compounds from the Active Fraction

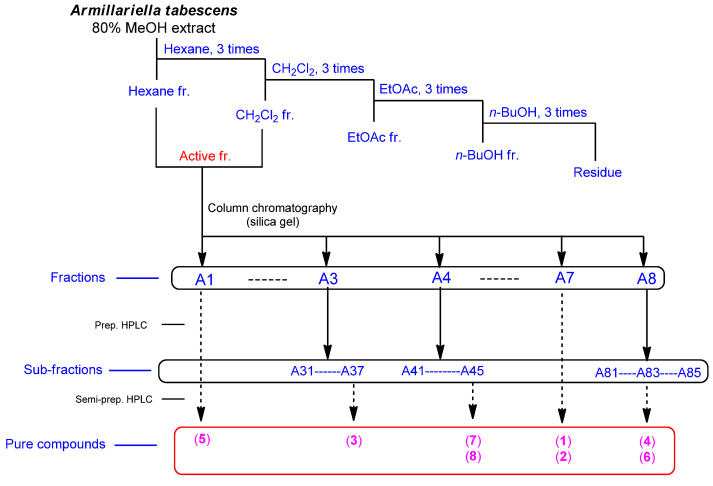

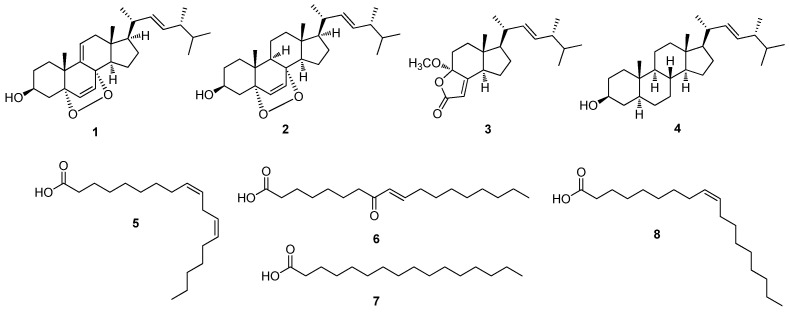

Based on the results of the bioactivity-guided fractionation for estrogen-like effects, chemical investigation of the active HCF fraction was conducted to identify the chemical contributors to the estrogenic activity of the MeOH extract of A. tabescens. Chemical investigation of the EA fraction, using column chromatography and preparative and semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purification, led to the isolation and identification of four steroids (1–4) and four fatty acids (5–8) from the active fraction (Figure 3). The structures of compounds 1–8 (Figure 4) were determined to be 9,11-dehydroergosterol peroxide (1) [30], ergosterol peroxide (2) [30], (17R)-17-methylincisterol (3) [31], (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (4) [32], (Z,Z)-9,12-octadecadienoic acid (5) [33], (9E)-8-oxo-9-octadecenoic acid (6) [34], hexadecanoic acid (7) [35], and (9Z)-9-octadecenoic acid (8) [36], by comparing their 1H and 13C NMR spectra (Figures S1–S9) with those previously reported in the literature and by LC/MS analysis (Figures S10–S17).

Figure 3.

Separation scheme of compounds 1–8.

Figure 4.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–8; 9,11-dehydroergosterol peroxide (1), ergosterol peroxide (2), (17R)-17-methylincisterol (3), (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (4), (Z,Z)-9,12-octadecadienoic acid (5), (9E)-8-oxo-9-octadecenoic acid (6), hexadecanoic acid (7), and (9Z)-9-octadecenoic acid (8).

2.3. Effects of Compounds on the Proliferation of MCF-7 Cells

All the isolated compounds 1–8 were tested for their effects on MCF-7 cell proliferation to investigate their estrogenic activity. Among the tested isolates 1–8, only (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (compound 4) promoted cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells. Cell proliferation increased to 163.23 ± 4.23%, 384.38 ± 3.07%, and 429.33 ± 2.52% after treatment with 25 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM of compound 4, respectively, and the effects were mitigated by the ICI 182,780, an ER antagonist (Figure 5A). Cell proliferation increased to 201.71 ± 4.47%, 266.82 ± 8.72%, and 294.87 ± 7.31% after treatment with 25 nM, 50 nM, and 100 nM, respectively, of 17β-estradiol (E2) as a positive control, compared with the untreated cells (Figure 5B). These results proved that compound 4 is an effective phytoestrogen demonstrating E2-like activity in the proliferation of estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Comparison of estrogenic activities of (A) (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (4) and (B) 17β-estradiol (E2) in the absence or presence of ICI 182,780, as determined by cell proliferation measured by E-screen assay in MCF-7 cells. * Significant difference between untreated cells and cells treated with sample in the absence of ICI 182,780 (n = 3 independent experiments, p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test). Data are the mean ± SEM.

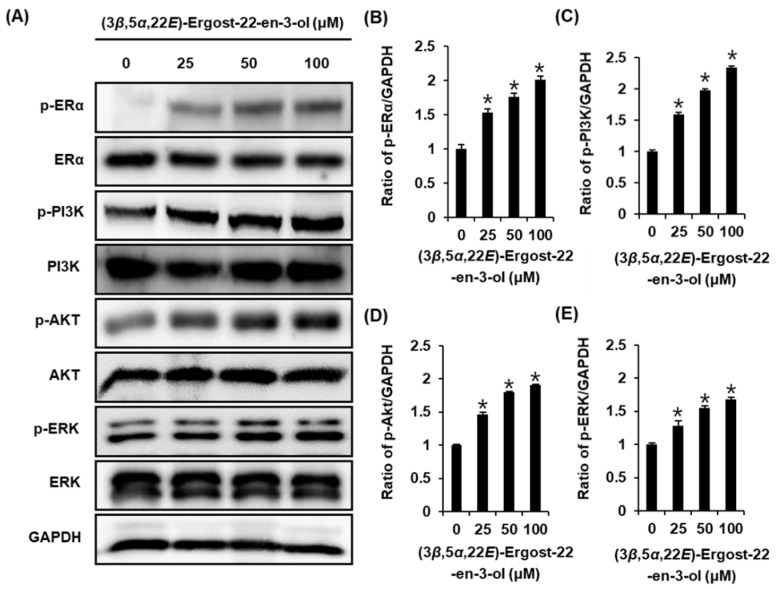

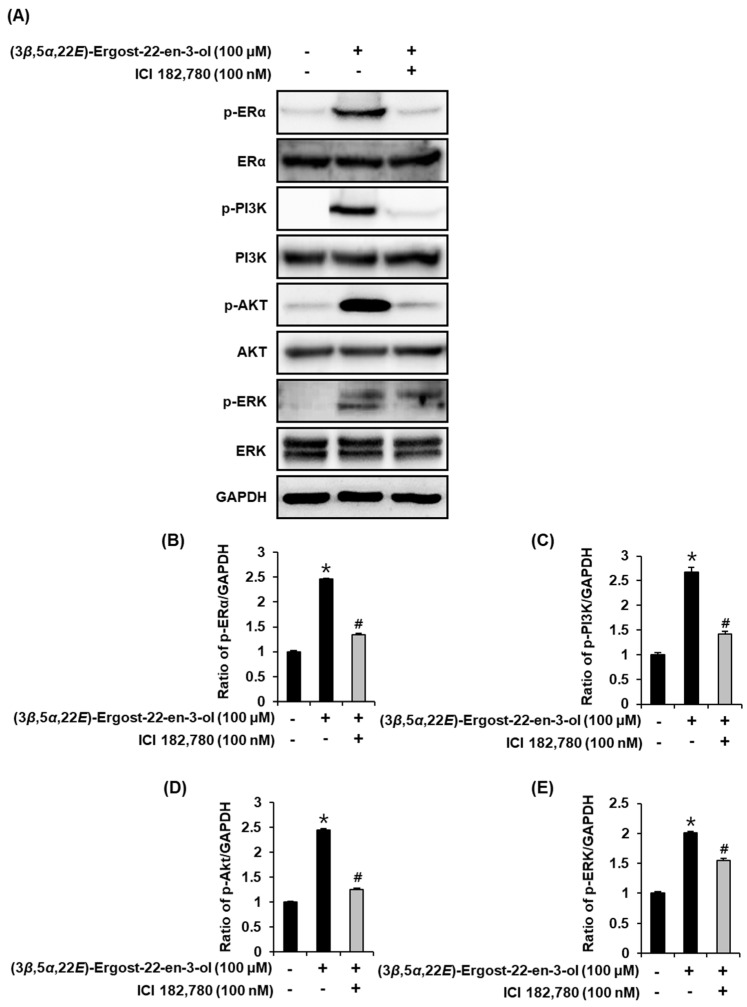

2.4. Effect of (3β,5α,22E)-Ergost-22-en-3-ol on the Protein Expression of Phospho-PI3K, PI3K, Phospho-Akt, Akt, Phospho-ERα, and ERα

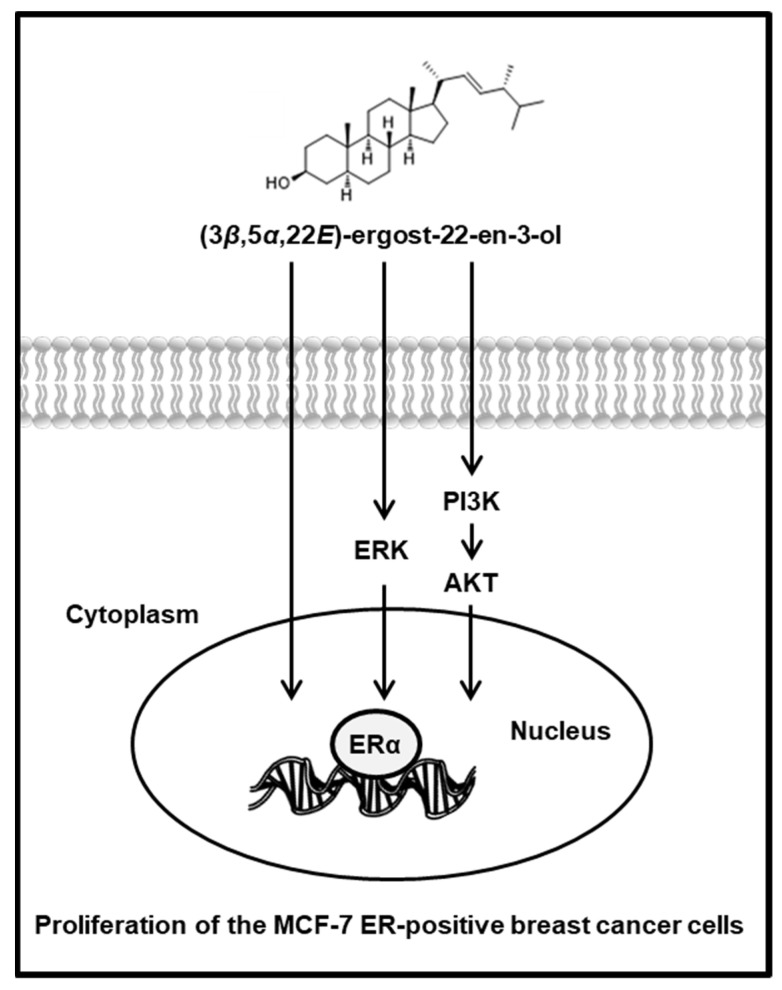

To support the proliferation-promoting effects of (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (4), the activation of ERα and related pathways were evaluated using Western blot analysis. Compared with untreated cells, 25 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM of compound 4 induced a concentration-dependent increase in the protein expression of p-ERK, p-PI3K, p-Akt, and p-ERα (Figure 6). Furthermore, this effect was mitigated by treatment with 100 nM ICI. When ICI was present, the expression of p-ERK, p-PI3K, p-Akt, and ERα failed to increase after treatment with 100 µM of compound 4 (Figure 7). These results proved that the responses of ERK, PI3K, and Akt to compound 4 depend on the functioning of ER (Figure 8).

Figure 6.

Effect of (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (compound 4) on the protein expression of phospho-extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK), ERK, phospho-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (p-PI3K), PI3K, phospho-Akt (p-Akt), Akt, phospho-estrogen receptor α (p-ERα), and ERα in MCF-7 cells. (A) Protein expression levels of p-PI3K, PI3K, p-Akt, Akt, p-ERα, ERα, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in MCF-7 cells treated or untreated with 25 µM, 50 µM, and 100 µM compound 4 for 24 h. (B–E) Bar graph presents the densitometric quantification of Western blot bands. * Significant difference between cells treated with compound 4 and the untreated cells (n = 3 independent experiments, p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test). Data are the mean ± SEM.

Figure 7.

Effect of (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (compound 4) in the absence or presence of ICI 182,780 (ICI) on the protein expression of phospho-extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK), ERK, phospho-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (p-PI3K), PI3K, phospho-Akt (p-Akt), Akt, phospho-estrogen receptor α (p-ERα), and ERα in MCF-7 cells. (A) Protein expression levels of p-PI3K, PI3K, p-Akt, Akt, p-ERα, ERα, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in MCF-7 cells treated or untreated with concentrations of 100 µM compound 4, either with or without 100 nM ICI 182,780 (ICI) for 24 h. (B–E) Bar graph presents the densitometric quantification of Western blot bands. * Significant difference between cells treated with compound 4 and the untreated cells. # Significant reduction in co-treatment with ICI compared to treatment with compound 4 alone (n = 3 independent experiments, p < 0.05, Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 8.

Schematic illustration of the underlying mechanism of the estrogenic activity of (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol via estrogen receptor α (ERα)-dependent signaling pathways in MCF-7 estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells.

3. Discussion

Few previous studies have investigated the compounds isolated from A. tabescens. Our previous chemical studies on A. tabescens have shown the presence of steroids, alkaloids, nucleic acids, and fatty acids. (Z,Z)-9,12-Octadecadienoic acid, a fatty acid, is known to possess anti-inflammatory activity [23]. Extending from our previous study, the present study found that the MeOH extract of A. tabescens had estrogen-like effects on MCF-7 cells. Eight compounds were isolated from the active fraction, the hexane- and CH2Cl2-soluble fraction showing estrogen-like effects. Of the eight compounds tested, only (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol (compound 4) promoted cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells. Co-treatment with ICI 182,780, an ER antagonist, inhibited the proliferation-stimulatory effect. These results indicated that compound 4 exhibited a proliferation-stimulatory effect via the ER in MCF-7 cells. Its proliferation-stimulatory effect was confirmed by the expression of proteins related to the ER signaling pathway. The binding of estrogen to the G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) activates the ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways [37,38]. ERK is a family of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) stimulated by peptide hormones, cellular stress, and cytokines. It regulates the proliferation of ER-positive breast cancer cells [39]. The activated PI3K/Akt pathway regulates cellular growth, survival, and proliferation in normal estrogen-responsive tissues [40,41]. Ginsenoside Rg1, a chemical component of ginseng, has been reported to possess estrogen-like effects and promote ER signaling via the ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways [42]. Various studies have reported the estrogen-like effect of acacetin, a flavonoid, and its possible mechanism has also been evaluated as the ERK and PI3K/Akt pathway [43,44,45]. In our study, (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol also induced a concentration-dependent increase in the protein expression of p-ERK, p-PI3K, p-Akt, and p-ERα in MCF-7 cells, similar to that of other reported phytoestrogens. Therefore, it was concluded that the estrogen-like effect of (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol was mainly mediated via ERα. These cell-based results demonstrated for the first time that the extract of A. tabescens exhibited potent estrogen-like effects. Among the isolates, (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol was the main contributor to the estrogen-like effect of A. tabescens; it may be a potential candidate for further verification in animal experiments, towards finding estrogen-like drugs to eventually help postmenopausal women.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured using a Jasco P-2000 polarimeter (Jasco, Easton, MD, USA). Ultraviolet (UV) spectra were acquired using an Agilent 8453 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). NMR spectra were measured using a Bruker AVANCE III 700 NMR spectrometer operating at 700 MHz (1H) and 175 MHz (13C; Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). Preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using a Waters 1525 Binary HPLC Pump with a Waters 996 Photodiode Array Detector (Waters Corporation, Milford, CT, USA) and an Agilent Eclipse C18 column (250 × 21.2 mm, 5 μm; flow rate: 5 mL/min; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Semi-preparative HPLC was performed using a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC System with SPD-20A/20AV Series Prominence HPLC UV-Vis detectors (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) and a Phenomenex Luna phenyl-hexyl column (250 × 10 mm inner diameter [ID], flow rate: 2 mL/min; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis was performed using an Agilent 1200 Series HPLC system equipped with a diode array detector and 6130 Series ESI mass spectrometer using an analytical Kinetex C18 100 Å column (100 × 2.1 mm, 5 μm; flow rate: 0.3 mL/min; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Column chromatography was performed using silica gel 60, 230–400 mesh, and reverse-phase (RP) C18 silica gel, 230–400 mesh (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Sephadex LH-20 (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) was used for molecular-sieve column chromatography. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was conducted using precoated silica gel F254 plates and RP-18 F254s plates (Merck). Spots on TLC were detected using UV light and heating after dipping in anisaldehyde sulfuric acid.

4.2. Fungus Material

Fresh fruiting bodies of A. tabescens were collected from Hwasung, Gyeonggi-do, Korea, in September 2014. Samples of fungal material were identified by one of the authors (K.H.K.). A voucher specimen (SKKU 2015-09-BN) was deposited in the herbarium of the School of Pharmacy, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon, Korea.

4.3. Extraction and Isolation

Shade-dried and chopped A. tabescens mushrooms (310 g) were extracted with 80% aqueous MeOH three times (each 3 L × 24 h) at room temperature. The resulting extracts were filtered, and the filtrate concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (EYELA, Tokyo Rikakikai Co., Tokyo, Japan). The resultant MeOH extract (28.7 g) was suspended in distilled water (700 mL) and successively solvent-partitioned three times using hexane, dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and n-butanol (n-BuOH), which yielded a hexane-soluble fraction (0.9 g), a CH2Cl2-soluble fraction (1.0 g), an EtOAc-soluble fraction (0.3 g), and an n-BuOH-soluble fraction (1.7 g). LC/MS and TLC analyses indicated that the hexane-soluble and CH2Cl2-soluble layers had similar chemical profiles, allowing us to consolidate the hexane- and CH2Cl2-soluble layers for further experiments. The active hexane- and CH2Cl2-soluble fraction (HCF; 1.9 g) was subjected to silica-gel (230–400 mesh, Merck, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) column chromatography (CC), using a gradient solvent system of hexane/EtOAc from 30:1 to 1:1, to yield eight fractions (Fr. A1–A8). Fr. A1 (353 mg) was purified by semi-preparative HPLC (solvent system of 91% MeOH) using a Phenomenex Luna phenyl-hexyl column (250 × 10 mm ID, flow rate: 2 mL/min) to isolate compound 5 (13.1 mg). Fr. A3 (192 mg) was separated by preparative HPLC (solvent system of 83% MeOH) using an Agilent Eclipse C18 column (250 × 21.2 mm ID, flow rate: 5 mL/min) to obtain seven fractions (Fr. A31–A37). Fr. A37 (85 mg) was further purified by semi-preparative HPLC (solvent system of 88% MeOH) using the Phenomenex Luna phenyl-hexyl column system to yield compound 3 (1.7 mg). Fr. A4 (174 mg) was fractionated with preparative HPLC (gradient solvent system of 85–100% MeOH), using the above conditions of the Agilent Eclipse C18 column, to give five fractions (Fr. A41–A45). Fr. A45 (94 mg) was further purified using preparative HPLC (solvent system of 84% MeOH) with the same column to obtain five subfractions (Fr. A451–A455). Fr. A455 (53 mg) was separated by semi-preparative HPLC (solvent system of 87% MeOH) using a Phenomenex Luna phenyl-hexyl column, which yielded compounds 7 (7.3 mg) and 8 (2.4 mg). Fr. A7 (24.6 mg) was directly subjected to semi-preparative HPLC (solvent system of 90% MeOH) using a Phenomenex Luna phenyl-hexyl column to purify compounds 1 (0.9 mg) and 2 (1.2 mg). Fr. A8 (380 mg) was separated on a Sephadex LH-20 column using a solvent system of CH2Cl2/MeOH (2:8), and five fractions were obtained (Fr. A81–A85). Fr. A83 (155 mg) was separated by preparative HPLC (gradient solvent system of 70–100% MeOH) using an Agilent Eclipse C18 column to give five subfractions (Fr. A831–A835). Fr. A834 (14.8 mg) was further purified using semi-preparative HPLC (solvent system of 76% MeOH) using a Phenomenex Luna phenyl-hexyl column to yield compound 6 (0.9 mg), and Fr. A835 (24 mg) was also purified by semi-preparative HPLC (solvent system of 85% MeOH) using the same column to yield compound 4 (1.0 mg).

4.4. Cell Culture

The ER-positive MCF-7 human breast epithelial cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI1640) medium (Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) with 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA). MCF-7 cells were stored at 37 °C in an incubator with a CO2 concentration of approximately 5%.

4.5. E-Screen Assay

MCF-7 cells were cultured in 24-well plates to a final concentration of 1 × 105 cells per well in RPMI medium without phenol red (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 5% charcoal-dextran stripped human serum (Innovative Research, Novi, MI, USA) for 24 h. MCF-7 cells were treated with MeOH extract (5–100 μg/mL), HCF (5–100 μg/mL), the isolated compounds 1–8 (5–100 μM), and 17β-estradiol (E2; 5–100 nM), either with or without ICI 182,780 (100 nM), for 144 h. Ez-Cytox reagents (Daeil Lab Service Co., Seoul, Korea) were added to each well and incubated for 40 min. The absorbance of each well was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (PowerWave XS).

4.6. Western Blot Analysis

MCF-7 cells were cultured in 6-well plates at a final concentration of 4 × 105 cells per well in RPMI medium without phenol red (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 5% charcoal-dextran stripped human serum (Innovative Research, Novi, MI, USA) for 24 h. MCF-7 cells were treated with compound 4 (25 μM to 100 μM) for 24 h. Proteins (20 µg) from MCF-7 cells were fractionated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gel) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. Phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK), ERK, phospho-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (p-PI3K), PI3K, phospho-Akt, Akt, phospho-estrogen receptor α (p-ERα), ERα, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Cell Signaling Technology) were used as primary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized on a FUSION Solo Chemiluminescence System (PEQLAB Biotechnologie GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) using ECL Advance Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK).

4.7. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics ver. 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Non-parametric comparisons of samples were conducted using the Kruskal–Wallis test to analyze the results. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we reported the estrogenic effect of (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol isolated from the MeOH extract of the fruiting bodies of A. tabescens in MCF-7 estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Our results demonstrated that (3β,5α,22E)-ergost-22-en-3-ol significantly increased the proliferation of MCF-7 cells, which was associated with the activation of ERK, PI3K, Akt, and ERα. (3β,5α,22E)-Ergost-22-en-3-ol may have potential for use in controlling the estrogenic activity involved in menopausal symptoms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded online. Figure S1: The 1H NMR spectrum of 1 (CDCl3, 700 MHz), Figure S2: The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 (CDCl3, 700 MHz), Figure S3: The 1H NMR spectrum of 3 (CDCl3, 700 MHz), Figure S4: The 13C NMR spectrum of 3 (CDCl3, 175 MHz), Figure S5: The 1H NMR spectrum of 4 (CD3OD, 700 MHz), Figure S6: The 1H NMR spectrum of 5 (CDCl3, 700 MHz), Figure S7: The 1H NMR spectrum of 6 (CDCl3, 700 MHz), Figure S8: The 1H NMR spectrum of 7 (CDCl3, 700 MHz), Figure S9: The 1H NMR spectrum of 8 (CDCl3, 700 MHz), Figure S10: Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of compound 1 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S11: TIC of compound 2 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S12: TIC of compound 3 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S13: TIC of compound 4 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S14: TIC of compound 5 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S15: TIC of compound 6 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S16: TIC of compound 7 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S17: TIC of compound 8 in the LC/MS analysis, Figure S18: UV chromatogram of LC/MS (detection wavelength was set as 254 nm) of (A) hexane-soluble and (B) CH2Cl2-soluble factions, Figure S19: TLC analysis of (A) hexane-soluble and (B) CH2Cl2-soluble factions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S.K. and K.H.K.; formal analysis, D.L., Y.-K.C., Y.K., C.P. and Y.-J.K.; investigation, D.L. and Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L., Y.K., K.H.K. and K.S.K.; writing—review and editing, K.H.K. and K.S.K.; visualization, D.L. and Y.K.; supervision, K.S.K. and K.H.K.; project administration, K.S.K. and K.H.K.; funding acquisition, K.S.K. and K.H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was also supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT; grant number 2021R1A2C2007937, and 2019R1F1A1059173). This research was also funded by the Gachon University research fund of 2020 (GCU-202002780001).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are not available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Research on the Menopause in the 1990s: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill K. The demography of menopause. Maturitas. 1996;23:113–127. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(95)00968-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim M.Y., Im S.-W., Park H.M. The demographic changes of menopausal and geripausal women in Korea. J. Bone Metab. 2015;22:23–28. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2015.22.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurzer M. Soy consumption for reduction of menopausal symptoms. Inflammopharmacology. 2008;16:227–229. doi: 10.1007/s10787-008-8021-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whiteley J., DiBonaventura M.D., Wagner J.-S., Alvir J., Shah S. The impact of menopausal symptoms on quality of life, productivity, and economic outcomes. J. Women’s Health. 2013;22:983–990. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton J.L. Menopausal hormone therapy, age, and chronic diseases: Perspectives on statistical trends. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016;29:1583–1590. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glazier M.G., Bowman M.A. A review of the evidence for the use of phytoestrogens as a replacement for traditional estrogen replacement therapy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001;161:1161–1172. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.9.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fait T. Menopause hormone therapy: Latest developments and clinical practice. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212551. doi: 10.7573/dic.212551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett-Connor E.L. The risks and benefits of long-term estrogen replacement therapy. Public Health Rep. 1989;104:62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patisaul H.B., Jefferson W. The pros and cons of phytoestrogens. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31:400–419. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cos P., De Bruyne T., Apers S., Berghe D.V., Pieters L., Vlietinck A.J. Phytoestrogens: Recent developments. Planta Med. 2003;69:589–599. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-41122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carusi D. Phytoestrogens as hormone replacement therapy: An evidence-based approach. Prim. Care Update OB/GYNS. 2000;7:253–259. doi: 10.1016/S1068-607X(00)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu P., Maier C. Phytoestrogens and breast cancer: In vitro anticancer activities of isoflavones, lignans, coumestans, stilbenes and their analogs and derivatives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;107:1648–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson K.E., Hagler W.M., Jr., Mirocha C.J. Production of zearalenone,. alpha.-and. beta.-zearalenol, and. alpha.-and. beta.-zearalanol by Fusarium spp. in rice culture. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1985;33:862–866. doi: 10.1021/jf00065a024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding X., Lichti K., Staudinger J.L. The mycoestrogen zearalenone induces CYP3A through activation of the pregnane X receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;91:448–455. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasad S., Rathore H., Sharma S., Yadav A. Medicinal mushrooms as a source of novel functional food. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Diet. 2015;4:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimizu K., Yamanaka M., Gyokusen M., Kaneko S., Tsutsui M., Sato J., Sato I., Sato M., Kondo R. Estrogen-like activity and prevention effect of bone loss in calcium deficient ovariectomized rats by the extract of Pleurotus eryngii. Phytother. Res. 2006;20:659–664. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee D., Yu J.S., Ryoo R., Kim J.-C., Jang T.S., Kang K.S., Kim K.H. Pulveraven A from the fruiting bodies of Pulveroboletus ravenelii induces apoptosis in breast cancer cell via extrinsic apoptotic signaling pathway. J. Antibiot. 2021;74:752–757. doi: 10.1038/s41429-021-00435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee S., Lee D., Ryoo R., Kim J.-C., Park H.B., Kang K.S., Kim K.H. Calvatianone, a sterol possessing a 6/5/6/5-fused ring system with a contracted tetrahydrofuran B-ring, from the fruiting bodies of Calvatia nipponica. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:2737–2742. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S.R., Lee D., Lee B.S., Ryoo R., Pang C., Kang K.S., Kim K.H. Phallac acids A and B, new sesquiterpenes from the fruiting bodies of Phallus luteus. J. Antibiot. 2020;73:729–732. doi: 10.1038/s41429-020-0328-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee D., Lee W.-Y., Jung K., Kwon Y.S., Kim D., Hwang G.S., Kim C.-E., Lee S., Kang K.S. The inhibitory effect of cordycepin on the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells, and its mechanism: An investigation using network pharmacology-based analysis. Biomolecules. 2019;9:414. doi: 10.3390/biom9090414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S., Lee D., Lee J.C., Kang K.S., Ryoo R., Park H.J., Kim K.H. Bioactivity-guided isolation of anti-inflammatory constituents of the rare mushroom Calvatia nipponica in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Chem. Biodivers. 2018;15:e1800203. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S., Lee D., Park J.Y., Seok S., Jang T.S., Park H.B., Shim S.H., Kang K.S., Kim K.H. Antigastritis effects of Armillariella tabescens (Scop.) Sing. and the identification of its anti-inflammatory metabolites. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018;70:404–412. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S., Park J.Y., Lee D., Seok S., Kwon Y.J., Jang T.S., Kang K.S., Kim K.H. Chemical constituents from the rare mushroom Calvatia nipponica inhibit the promotion of angiogenesis in HUVECs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017;27:4122–4127. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S.R., Lee D., Lee H.-J., Noh H.J., Jung K., Kang K.S., Kim K.H. Renoprotective chemical constituents from an edible mushroom, Pleurotus cornucopiae in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Bioorg Chem. 2017;71:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen J.-W., Ma B.-J., Li W., Yu H.-Y., Wu T.-T., Ruan Y. Activity of armillarisin B in vitro against plant pathogenic fungi. Z. Nat. C J. Biosci. 2009;64:790–792. doi: 10.1515/znc-2009-11-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y., Wang Y., Li P., Tang Y., Fawcett J.P., Gu J. Quantitation of Armillarisin A in human plasma by liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2007;43:1860–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai F. Study on the isolation, purification and antitumor activity in vivo of polysaccharide extracted from Armillariella tabescens. Jiyinzuxue Yu Yingyong Shengwuxue. 2013;32:767–770. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiho T., Shiose Y., Nagai K., Ukai S. Polysaccharides in fungi. XXX. Antitumor and immunomodulating activities of two polysaccharides from the fruiting bodies of Armillariella tabescens. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1992;40:2110–2114. doi: 10.1248/cpb.40.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Y.-K., Kuo Y.-H., Chiang B.-H., Lo J.-M., Sheen L.-Y. Cytotoxic activities of 9,11-dehydroergosterol peroxide and ergosterol peroxide from the fermentation mycelia of Ganoderma lucidum cultivated in the medium containing leguminous plants on Hep 3B cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:5713–5719. doi: 10.1021/jf900581h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciminiello P., Fattorusso E., Magno S., Mangoni A., Pansini M. Incisterols, a new class of highly degraded sterols from the marine sponge Dictyonella incisa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:3505–3509. doi: 10.1021/ja00165a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shirane N., Takenaka H., Ueda K., Hashimoto Y., Katoh K., Ishii H. Sterol analysis of DMI-resistant and-sensitive strains of Venturia inaequalis. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:1301–1308. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00787-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marwah R.G., Fatope M.O., Deadman M.L., Al-Maqbali Y.M., Husband J. Musanahol: A new aureonitol-related metabolite from a Chaetomium sp. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:8174–8180. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.05.119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawagishi H., Miyazawa T., Kume H., Arimoto Y., Inakuma T. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Inhibitors from the Mushroom Clitocybe clavipes. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:1712–1714. doi: 10.1021/np020200j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sujun Y., Jingyu S., Longmei Z., Lijuan L., Yanhong W. Chemical constituents of alga Halimeda incrassata (II) Trop. Oceanogr. 2002;21:92–95. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akita C., Kawaguchi T., Kaneko F., Yamamoto H., Suzuki M. Solid-state13C NMR study on order→disorder phase transition in oleic acid. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:4862–4868. doi: 10.1021/jp037326p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macêdo D.S., Sanders L.L.O., das Candeias R., Montenegro C.D.F., de Lucena D.F., Chaves Filho A.J.M., Seeman M.V., Monte A.S.G. Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor 1 (GPER) as a Novel Target for Schizophrenia Drug Treatment. Schizophr. Bull. Open. 2020;1:sgaa062. doi: 10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pepermans R.A., Sharma G., Prossnitz E.R. G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor in Cancer and Stromal Cells: Functions and Novel Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells. 2021;10:672. doi: 10.3390/cells10030672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bratton M.R., Antoon J.W., Duong B.N., Frigo D.E., Tilghman S., Collins-Burow B.M., Elliott S., Tang Y., Melnik L.I., Lai L. Gαo potentiates estrogen receptor α activity via the ERK signaling pathway. J. Endocrinol. 2012;214:45. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kazi A.A., Molitoris K.H., Koos R.D. Estrogen rapidly activates the PI3K/AKT pathway and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and induces vascular endothelial growth factor A expression in luminal epithelial cells of the rat uterus. Biol. Reprod. 2009;81:378–387. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.076117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shrivastav A., Murphy L. Interactions of PI3K/Akt/mTOR and estrogen receptor signaling in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Manag. 2012;1:235–249. doi: 10.2217/bmt.12.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi C., Zheng D.-D., Fang L., Wu F., Kwong W.H., Xu J. Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes nonamyloidgenic cleavage of APP via estrogen receptor signaling to MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1820:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ren H., Ma J., Si L., Ren B., Chen X., Wang D., Hao W., Tang X., Li D., Zheng Q. Low dose of acacetin promotes breast cancer MCF-7 cells proliferation through the activation of ERK/PI3K/AKT and cyclin signaling pathway. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 2018;13:368–377. doi: 10.2174/1574892813666180420154012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barlas N., Özer S., Karabulut G. The estrogenic effects of apigenin, phloretin and myricetin based on uterotrophic assay in immature Wistar albino rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2014;226:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei Y., Yuan P., Zhang Q., Fu Y., Hou Y., Gao L., Zheng X., Feng W. Acacetin improves endothelial dysfunction and aortic fibrosis in insulin-resistant SHR rats by estrogen receptors. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020;47:6899–6918. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05746-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.