Abstract

Valproic acid (VPA) is a well-established anticonvulsant drug discovered serendipitously and marketed for the treatment of epilepsy, migraine, bipolar disorder and neuropathic pain. Apart from this, VPA has potential therapeutic applications in other central nervous system (CNS) disorders and in various cancer types. Since the discovery of its anticonvulsant activity, substantial efforts have been made to develop structural analogues and derivatives in an attempt to increase potency and decrease adverse side effects, the most significant being teratogenicity and hepatotoxicity. Most of these compounds have shown reduced toxicity with improved potency. The simple structure of VPA offers a great advantage to its modification. This review briefly discusses the pharmacology and molecular targets of VPA. The article then elaborates on the structural modifications in VPA including amide-derivatives, acid and cyclic analogues, urea derivatives and pro-drugs, and compares their pharmacological profile with that of the parent molecule. The current challenges for the clinical use of these derivatives are also discussed. The review is expected to provide necessary knowledgebase for the further development of VPA-derived compounds.

Keywords: valproic acid, anticonvulsant, analogues, derivatives, teratogenicity, hepatotoxicity, development

1. Introduction

Valproic acid (VPA, 2-propyl-pentanoic acid), is a fatty acid derivative of valeric acid naturally found in Valeriana officinalis [1,2]. Synthesized in 1881 by Beverly S Burton [3], VPA continued to be used as an organic solvent till 1963 before its role as an anticonvulsant was discovered serendipitously by Meunier et al. [4]. Following its first marketing as an antiepileptic drug (AED) in France, VPA represents one of the most efficient and widely prescribed AED world-wide [1]. With its recognized role as an AED, VPA has drastically evolved as a molecule targeting a spectrum of pathologies such as bipolar disorder, migraines and neuropathic pain [5,6,7]. VPA has shown promise as a neuroprotective agent in Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis [8,9,10]. Additionally, overlapping pathways and interactions have led to its recognition as a compound of interest in the clinical trials for a wide variety of cancers [11,12,13,14]. However, the potential adverse effects associated with VPA use are hepatotoxicity and teratogenicity, which interfere with its therapeutic use [15]. Substantial experimentation and research have gone into elimination of these adverse effects and to improve its efficacy by introducing structural changes in the VPA skeletal structure. These changes ranged from branching and alpha fluorination to production of chiral compounds, from its amide derivatives to cyclic derivatives and conjugation products. This article briefly discusses on the structural elements of valproic acid, its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic profile. The focus of the review is to provide a comprehensive account of all the derivatives and analogues of VPA and ascertain their success as possible replacement of the parent compound as better, safe and tolerable drugs. Any compound second generation to VPA shall address the current challenges of potency and teratogenicity along with hepatotoxicity of the metabolites. This knowledge of the existing modifications will serve a platform to design better successors of VPA.

2. Structure and Pharmacology of Valproic Acid

2.1. VPA Structural Elements

The simple chemical structure of VPA makes it unique in the arsenal of drugs that are used for same treatments as VPA. It is an eight-carbon molecule with the backbone of pentanoic acid and a propyl group attached to the second carbon. It is a weak organic acid with pKa value of 4.8, that causes 99.8% ionization of the molecule at physiological pH [16]. Therefore, despite of good lipophilicity (logP = 2.75) it requires carrier protein for its cellular uptake [16]. Keane et al., reported lack of anticonvulsant activity of non-branched analogues of VPA in vivo [17]. On the contrary, branched analogues were found to significantly increase the brain concentration of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), showing anticonvulsant activity against induced seizures in animal models [17,18,19]. These studies indicated the essentiality of the branched structure of VPA for anticonvulsant activity. It has also been proposed that C=O group is the main functional group controlling the anticonvulsant behavior by providing the initial electrostatic interaction between VPA and the target protein [20]. Other than the molecule’s therapeutic effect, structure-teratogenicity relationship studies performed in mouse strains implicated that the tetrahedral structure, the hydrogen attached to C-2 and aliphatic side chain branching [21] may be responsible for the undesirable teratogenic effect associated with its use [22]. Lloyd et al., also suggested the role of carboxylic acid moiety in causing neural tube defect. It has been reported that the carboxylic group of VPA that exists as an anion at physiological pH interacts with organic anion transporters (OATs) present on the foetal facing/basolateral plasma membrane of the placenta [23]. This interaction of VPA with OATs leads to VPA accumulation in foetus causing embryotoxicity [23]. Next substantial side-effect, hepatotoxicity is primarily caused by metabolites of VPA (4-ene-VPA and 2,4-diene-VPA) [24,25,26,27].

2.2. VPA Pharmacokinetics

Valproic acid is available for treatment in various forms such as oral solutions, tablets, enteric-coated capsule and intravenous solution, with bioavailability up to 100% and absorption half-life ranging from 30 min to 4 h depending upon the type of formulation used [28,29]. Among the present preparations, the oral formulations are widely used with enteric coated capsule showing highest bio-availability compared to other oral formulations [28]. Food intake influences the absorption of VPA, with absorption being slowest when taken after three hours of a meal as compared to when taken with meals or during fasting conditions [30].

Established metabolic routes of VPA are glucuronidation and beta oxidation, which account for 50% and 40% of VPA metabolism, respectively [31,32]. Studies have also explored the involvement of cytochrome P450 (CYP450)-mediated oxidation, although its contribution remains low (~10% VPA metabolism) [33,34]. A major metabolite found in urine samples is a conjugate product of VPA and glucuronic acid (15% to 40% of total VPA administered in humans) [35,36]. The metabolites produced via oxidation pathways are known to cause hepatotoxicity. Direct esterification of VPA or esterification of one of the major metabolites, 4-ene-VPA, forms respective acetyl-CoA esters [37,38]. These esters are highly reactive and they form thiol conjugates with mitochondrial glutathione, which result in the depletion of mitochondrial glutathione. The resulting reduction in the glutathione pool causes interference with mitochondrial function, which leads to hepatotoxicity [37,39,40].

The plasma level of a free fraction of VPA therapeutic concentration is 6%; the rest is bound to protein mainly albumin. Due to its high affinity for the protein, VPA shows a low clearance rate of 6–8 mL/h/kg [41,42,43].

2.3. VPA Pharmacodynamics

Valproic acid is primarily prescribed for the treatment of epilepsy, bipolar disorder and migraines. The anticonvulsant property of VPA is due to its influence on brain concentrations of GABA. It indirectly inhibits GABA degradation by hindering the activity of enzymes, such as GABA transaminase (GABA-T) and succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) that are involved in GABA decay [44]. Furthermore, VPA acts on GABA-receptor to potentiate postsynaptic inhibitory responses [29].

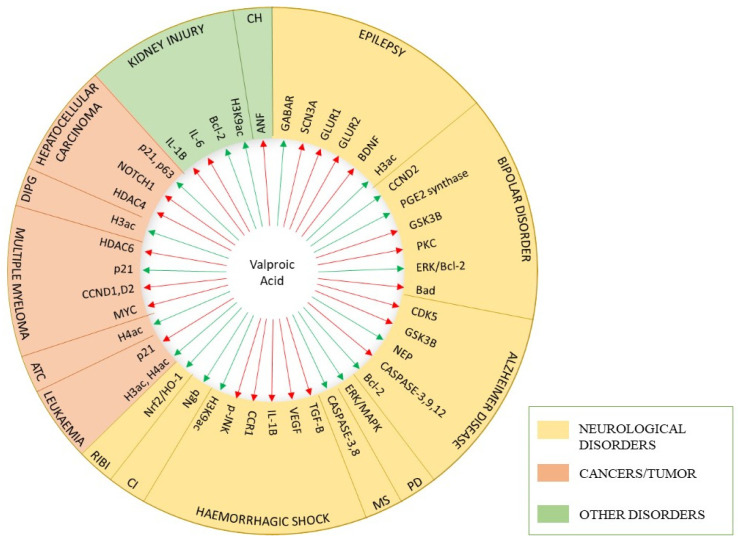

Other than affecting inhibitory synapses, VPA has been demonstrated to reduce the neuron surface expression and synaptic localization of glutamate-receptor subunits, GluR1/2, thus preventing excitatory effect [29]. It also obstructs various voltage gated ion channels such as Na+ channels, voltage-gated K+ channels, and voltage-gated Ca2+ channels [45]. Such an obstruction relaxes the high frequency neuronal firing [46,47]. The downregulation of sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 3 (SCN3a) expression by reducing the gene promoter methylation in mouse neural crest-derived cells is also suggested as an epigenetic pathway in the anticonvulsant role of VPA [48]. More recent finding of VPA pharmacodynamics is its role as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor [12,13]. leading to increase in gene expression of apoptotic proteins and hence its activity in cancer treatment [14]. Apart from these mechanisms, evidence demonstrates that VPA affects other signaling systems to exert its antimanic, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effect, which may lead to extension of its use in other non-epileptic neurological disorders; however, discussing these diverse roles is beyond the scope of this article. Figure 1 summarizes major molecular targets of VPA for various therapeutic areas.

Figure 1.

Molecular targets of valproic acid. Different targets regulated by valproic acid are represented by arrows for neurological disorders (epilepsy, bipolar disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease (PD), encephalomyelitis), haemorrhagic shock, ischemia, injury (radiation-induced brain injury (RIBI), kidney injury), cardiac hypertrophy (CH) and cancers (leukaemia, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC), multiple myeloma, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), hepatocellular carcinoma). The green arrows indicate upregulation of expression and red arrows indicate inhibition/downregulation of target gene.

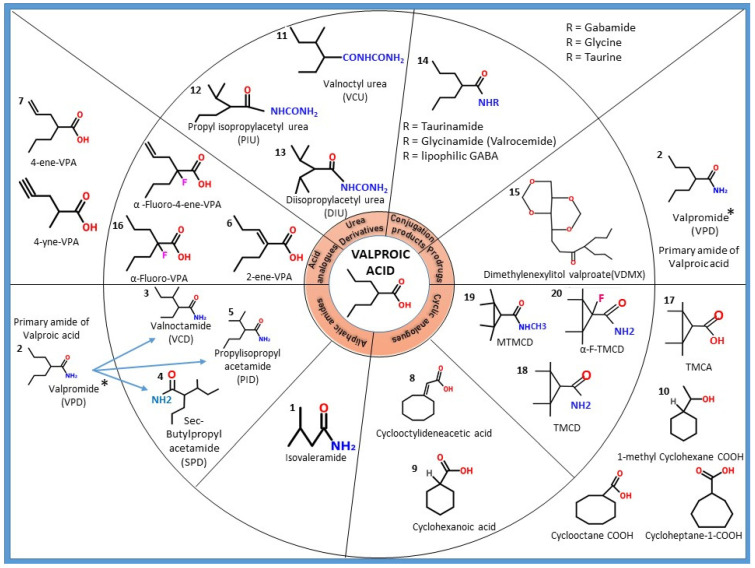

3. Structural Modification of Valproic Acid: Derivatives and Analogues

In attempts to minimize the adverse effects associated with VPA use and to improve its potency, various analogues and derivatives have been synthesized and studied in comparison to the parent molecule. As shown in Figure 2, primary modifications include altering the carboxylic acid group (replacing it with the amide); altering the main chain (replacing with cyclic entities) and/or changing the branching pattern by introducing unsaturated bonds. This section elaborates the literature reported under each VPA derivative describing the structural changes to the parent molecule, comparison of pharmacological properties in terms of potency, activity and toxicity profile and the clinical applicability of the compound. A brief summary of the above is shown in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of valproic acid derivatives and analogues. These compounds are characterised into aliphatic amides, acid analogues, conjugation products, prodrugs and cyclic analogues. The aliphatic amides are further characterised into chiral and achiral compounds, and acid analogues are further characterised into unsaturated and alpha fluorinated compounds. The compounds outside the circle are those with some limitations ceasing their further study. The compounds included in the circle are those that are under active investigation. * Valpromide is mentioned twice since along with being a primary amide of valpromide; it also behaves as a prodrug.

Table 1.

Valproic acid analogues and derivatives, classification and pharmacological activity.

| S. No | Candidate Compound | Parent Compound | Classification | Chemical Formula | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

Anticonvulsant Property | Clinical Trial Phase | Teratogenicity | Hepatotoxicity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isovaleramide | Isovaleric acid | Aliphatic amide | C5H11NO | 101.149 | Reduced | Phase I, a Phase II | Reduced | N.D. | [49] |

| 2 | Valpromide | Valproic acid | Aliphatic amide | C8H17NO | 143.23 | Increased | NA | * No change in humans | * No change in humans | [50] |

| 3 | Valnoctamide | Valpromide | Aliphatic amide | C8H17NO | 143.23 | Increased | b Phase III completed | Reduced | Reduced | [50] |

| 4 | sec-Butyl-propyl acetamide | Valpromide | Aliphatic amide | C9H19NO | 157.25 | Increased | Phase II | Reduced | Reduced | [51] |

| 5 | Propyl isopropyl acetamide | Valpromide | Aliphatic amide | C8H17NO | 143.23 | Increased | NA | Reduced | N.D. | [52] |

| 6 | 2-ene-VPA | Valproic acid | Acid analogue | C8H14O2 | 142.2 | Similar | c Phase I | Reduced | Reduced | [53] |

| 7 | 4-ene-VPA | Valproic acid | Acid analogue | C8H14O2 | 142.2 | Similar | NA | Increased | Increased | [27,54] |

| 8 | Cyclooctylideneacetic acid | Valproic acid | Cyclic analogue | C10H16O2 | 168.23 | Increased | NA | N.D. | N.D. | [55] |

| 9 | Cyclohexane carboxylic acid | Valproic acid | Cyclic analogue | C7H12O2 | 128.17 | Similar | NA | Reduced | N.D. | [55] |

| 10 | 1-methyl cyclohexane carboxylic acid | Cyclohexane carboxylic acid | Cyclic analogue | C8H14O2 | 142.2 | Increased | NA | N.D. | N.D. | [55] |

| 11 | Valnoctyl urea | Valnoctic acid | Urea Derivative | C9H18N2O2 | 186.25 | Increased | NA | Reduced | N.D. | [56] |

| 12 | Propyl isopropylacetyl urea | Diisopropyl acetamide | Urea Derivative | C9H18N2O2 | 186.25 | Increased | NA | Reduced | N.D. | [56] |

| 13 | Diisopropyl acetyl urea | Valproic acid | Urea Derivative | C9H18N2O2 | 186.25 | Increased | NA | N.D. | N.D. | [56] |

| 14 | Valrocemide | Valproic acid | Conjugation product | C10H20N2O2 | 200.282 | Increased | d Phase II | Absent | N.D. | [57,58] |

| 15 | Dimethylenexylitol valproate | Valproic acid | Sugar ester | C15H26O6 | 302.36 | Increased | NA | N.D. | N.D. | [59,60] |

| 16 | α-Floro-VPA | Valproic acid | Acid analogue | C8H15O2F | 162.20 | Reduced | NA | Reduced | Reduced | [61] |

| 17 | TMCA | Valproic acid | Cyclic analogue | C8H14O2 | 142.20 | Reduced | NA | N.D. | N.D. | [62] |

| 18 | TMCD | TMCA | Cyclic analogue | C8H15NO | 141 | Increased | NA | Reduced | N.D. | [62,63] |

| 19 | MTMCD | TMCA | Cyclic analogue | C9H17NO | 154 | Increased | NA | Reduced | N.D. | [63,64] |

| 20 | α-Floro-TMCD | TMCA | Cyclic analogue | C8H14FNO | 159.20 | Increased | NA | Reduced | N.D. | [24,65] |

Note—The change in anticonvulsant activity, teratogenicity and hepatotoxicity is mentioned with respect to valproic acid. * Since valpromide transforms into valproic acid in humans, there is no change in teratogenicity for valpromide; NA—not applicable, these compounds did not enter the clinical trials; N.D.—not determined; a: for acute migraine headache; b: for mania, schizoaffective disorder, manic type; c: drug tolerance study in health volunteers; d: for therapy-resistant patients with epilepsy.

3.1. Amide Derivatives of VPA

Amide derivatives of VPA have proven themselves to reduce the hepatotoxicity and teratogenicity of the parent compound. They have also depicted improved potency except valpromide, which systemically bio-transforms into VPA in human subjects [66].

3.1.1. Isovaleramide

Isovaleramide, a branched chain amide derivative of isovaleric acid (naturally occurring VPA analogue) with the molecular weight of 101.149 g/mol was developed by NPS Pharmaceuticals Inc., Salt Lake City, UT, USA under the alias of NPS 1776 [49]. Isovaleramide has a palatable taste and odour, unlike its parent compound isovaleric acid, which has an undesirable taste and odour [49]. Though, no mechanism of action for this compound has been reported, it is targeted for treatment of epilepsy and migraine attacks, and has shown broad spectrum of anticonvulsant activity in maximal electroshock stimulation (MES)-, pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures and kindling models along with chemo-convulsant and absence epilepsy models [49].

Islovaleramide exhibits linear pharmacokinetics in the dose range of 100–1600 mg [49]. The drug was found to be safe and well tolerated up to maximum dose of 2400 mg per day administered to phase 1 human volunteers with none of the adverse effects associated with VPA use [49]. Isovaleramide does not show any inhibitory effect on CYP450 enzymes, which may prevent any significant drug–drug interactions [49]. One limitation of the compound is its lower half-life of just 2.5 h, which leads to its rapid elimination. The reduced half-life of this potential drug can be targeted by making conjugation products or sustained release formulations [49]. Currently, the drug is undergoing phase II clinical trials for treatment of acute migraine headaches [67].

3.1.2. Valpromide (VPD)

Valpromide (VPD, dipropylacetamide, 2-propylvaleramide) is a 143.23 g/mol primary fatty acid amide of VPA, differing by the presence of amide group replacing the carboxylic acid functional group. This substitution makes it a more potent AED (2–5 times) as observed in in vivo models [68].

As opposed to the HDAC inhibitory effect of VPA, studies prove that VPD does not interfere with HDAC activity and thus has a highly diminished teratogenic effect in animals [12,69]. A study by France-Hélène Paradis and Barbara F. Hales [70] demonstrated that VPA causes downregulation of both SRY-Box Transcription Factor 9 (SOX9) and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2)-signalling pathways involved in chondrogenesis and osteogenesis, leading to an overall teratogenic limb malformation in rat embryos. The downregulation of these pathways was likely the consequence of histone-4 hyperacetylation by VPA. VPD essentially failed at affecting histone 4 hyperacetylation or SOX9 expression, with only minimally altering the expression of RUNX2, thus lacking teratogenic potential. However, VPD proved to be a stronger sedative and neurotoxin than VPA in a mice model of seizures [68].

Reports show that valpromide gets partially converted to valproic acid in dogs and rats [71]. Consistent with this, Bailer et al. found that following the oral administration of VPD in human subjects, blood plasma detection of VPA was observed instead of VPD. This suggested that VPD acts as a prodrug to VPA in humans, and bio-transforms into VPA in humans, due to which its superiority over VPA in vivo does not have any clinical significance [72].

To build upon the reduced teratogenicity, improved potency and to resist metabolic hydrolysis of the amide to its parent carboxylic acid compound, a further three compounds were derived from VPD (valnoctamide, sec-butyl-propyl carboxamide and propylisopropyl acetamide) [56].

Valnoctamide (VCD, 2-Ethyl-3-methylpentanamide)

Valnoctamide is a 143.23 g/mol constitutional isomer of VPD with valnoctic acid (VCA) as its corresponding acid. Structurally, the parent chain has two branches instead of one making two chiral centres. The first branching is from an ethyl group at C-2 position and the second branching is from a methyl group at C-3 position. Similar to VPD, VCD has also shown higher potency than VPA in rodent models, which might be attributed to its better brain distribution [50]. In a pilocarpine-treated rat model of focal epilepsy, VCD proved as effective as its parent compound VPD and its analogue VPA in showing protective and antiepileptogenic effects [73], although it failed to show any activity in status epilepticus (SE) model [51]. Additionally, both VCD and VPD also demonstrated improved attenuation of extracellular glutamate levels as compared to VPA [73].

Apart from anticonvulsant action, the enantiomers of VCD have been demonstrated to show efficacious antiallodynic activity in rats with neuropathic pain induced by spinal nerve ligation (SNL) [74]. Of the two diastereoisomers, (2S,3S)-VCD demonstrated lesser embryotoxicity and higher potency than (2R,3S)-VCD, indicating that (2S,3S)-VCD as the potential molecule for neuropathic pain treatment [74].

VCD was found to have longer half-life and mean residence time than VPD [50]. Besides, unlike VPD, VCD does not bio-transform into its corresponding acid or VPA under physiological condition and thus has a greatly reduced teratogenic potential. Okada et al. reported that inhibition of Polycomb group (Pc-G) gene expression by VPA led to axial skeletal abnormalities in embryos of pregnant NMRI mice, whereas VPD and VCD did not show any significant effect on these genes, thus proving them to be much less teratogenic than VPA [69]. The same group also revealed that VPA affects expression changes in genes involved in the cell cycle and apoptosis pathways of neural tube cells, causing neural tube defects in embryos of NMRI mice. However, VCD and VPD affected only few of these genes with majority of genes unaffected [75]. VCD has undergone phase III clinical trials and is primarily prescribed for mania, bipolar, and schizoaffective disorders [66,74]. Nirvanil, which is a racemic mixture of both enantiomeric pairs of VCD, is a marketed anxiolytic drug in some European countries, namely France, Holland, Italy, and Switzerland [76,77].

sec-Butyl-propylacetamide (SPD, 3-Methyl-2-propylpentanamide)

Another amide of VPA developed from VCD is its one-carbon homologue namely sec-Butyl-propylacetamide (SPD) and has been under investigation as a replacement of VPA. SPD differs from VCD by having a propyl rather than ethyl side chain at C-2 position. SPD demonstrated broad-spectrum antiseizure profile comparable to VPA [51]. Being currently in phase II clinical trials, SPD in animal studies has been effective against both focal and secondarily generalized seizures [51]. A dose-dependent decline was observed in secondarily generalized seizures when SPD was tested on kindled rodent models with median effective dose (ED50) values lesser than VCD and hence better efficacy [51]. It also caused a dip in seizure score from 4.6 to 1.3 in hippocampal kindled rats at a dose of 32 mg/kg and also with corneal kindled mice from 5 to 1 at 60 mg/kg [51]. In case of refractory 6Hz limbic seizures, an ED50 = 27 mg/kg for SPD was observed which is less than that of VCD (ED50 = 37 mg/kg) [51]. Moreover, unlike VCD, SPD also showed its activity in pilocarpine SE model with an ED50 value of 84 mg/kg with improved neuroprotective role as compared to VPA. SPD has also shown promising results in managing benzodiazepine-resistant seizures [51]. These findings implicate better efficacy of SPD over VCD.

Kaufmann et al. studied the antiallodynic activity of range of VPA related compounds in SNL model and found SPD to be as effective as Gabapentin in countering neuropathic pain with ED50 values of 49 mg/kg along with mild sedation observed at dose of 80 mg/kg [78].

The lack of teratogenicity was shown in studies where racemic SPD failed to induce neural tube defects (NTD) in SWV mice. Thus, along with better anticonvulsant property, it is nonembryotoxic and non-teratogenic [79].

Propylisopropyl Acetamide (PID, Diisopropyl Acetamide)

PID is a 143.23 g/mol constitutional isomer of VPD with a single stereocenter. As the name indicates, it has an isopropyl side chain at C-2 parent carbon instead of a n-propyl group as it is in VPA. It has anticonvulsant ability comparable to VPD and about 3–30 times more potency than VPA [80,81]. PID and VCD were tested for their anticonvulsant activity against generalized convulsive seizures in developing rats induced with PTZ. PID showed better control of generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS) in 25 days old rats as compared to much younger ones, whereas VCD proved to be an overall better anticonvulsant, with no significant differences observed between the two stereoisomers [82]. Stereoselectivity of PID enantiomers was seen in animal models, where it was observed that the R enantiomer is a more potent anticonvulsant than S-PID with ED50 of R-PID being 19–32% lower than the latter [83]. It was also found to be more potent in 6Hz seizure model compared to S-PID [81].

The results of teratogenic effect of VPA and PID in pregnant NMRI mice exhibited that in contrast to VPA causing 37% and 73% (water and Cremophor EL suspension respectively) exencephaly in foetuses; PID and its enantiomers did not show any significant teratogenic effect [84].

The development of PID as second generation VPA was stopped due to financial limitations of the holding company Jazz Pharmaceuticals [85].

3.2. Acid Analogues of VPA

3.2.1. 2-ene-VPA (2-Propyl-2-pentenoic Acid)

2-ene-VPA is a 142.2 g/mol, unsaturated metabolite of VPA with a double bond between C-2 and C-3 has undergone phase I clinical trial in humans to establish its safety and tolerability [53]. Its potency was observed to be 60–90% of the parent compound in electro and chemiconvulsive threshold tests in vivo [86,87]. Loscher et al. did the comparative analysis of 2-ene-VPA against the parent compound in mice models with MES and PTZ seizure, rats with chronically reoccurring spontaneous petit mal seizures and gerbils with GTCS [88]. The results of the study clearly reflected that 2-ene-VPA has comparable ED50 values to that of VPA and no toxicity at effective dose in gerbils and rats. The study also reported lack of embryotoxicity even at doses as high as 600 mg/kg [88]. However, 2-ene-VPA showed greater sedation than VPA at a dose of 200–300 mg/kg in MES- and PTZ-induced seizures [89].

The pharmacokinetic shortcoming of this analogue was its partial biotransformation into VPA, due to which its development as an AED was ceased [90].

3.2.2. 4-ene-VPA (2-n-Propyl-4-pentenoic Acid)

4-ene-VPA is a 142.2 g/mol acidic analogue and metabolite formed by terminal desaturation of valproic acid, by the action of CYP2C9 [44]. It is shown to have anticonvulsant potency similar to VPA [86,87].

In a study comparing teratogenic potencies of R and S enantiomeric forms of 4-ene-VPA in NMRI mice, S-(-)-4-ene-VPA was revealed to show four times higher exencephaly compared to the R enantiomer and also had higher teratogenic potential than VPA itself [54]. 4-ene-VPA also demonstrated hepatotoxicity in rats, and proved to be a good prediction compound in urine to ascertain hepatotoxicity of VPA [27]. Thus, higher hepatoxicity and teratogenicity of the metabolite than VPA despite having similar anticonvulsant activity might reason the absence of its clinical trial record.

3.3. Fluorinated Derivatives

Alpha-fluorovalproic acid is a 162.2 g/mol fluorinated derivative of valproic acid. This derivatisation was introduced with an aim to reduce the hepatotoxicity of VPA [25]. As mentioned earlier, metabolic conversion of VPA into (E)-2,4-diene-VPA via CYP450 and mitochondrial beta-oxidation results in further toxic intermediates, which causes hepatotoxicity. The introduction of fluorine at the alpha carbon of VPA, forms α-fluoro-4-ene VPA upon metabolic conversion [91]. This intermediate is a non-toxic analogue of 4-ene VPA and does not undergo beta-oxidation, thus preventing the formation of downstream hepato-toxic metabolite, 2,4-diene-VPA [92]. This non-toxic effect was evaluated in rats administered with α-fluoro-4-ene VPA, wherein no signs of hepatic microvesicular steatosis were observed. The derivative also showed reduced teratogenic effect in NMRI mice compared to VPA [61].

Although α-fluoro VPA did show its suppressive effect against PTZ-induced seizures in CD-1 mice, its maximal effect was much delayed likely due to its slower brain uptake [24]. Its ED50 value was observed to be 275.74 mg/kg vs. that of VPA with an ED50 of 119.7 mg/kg [24].

3.4. Cyclic Analogues of VPA

3.4.1. Cyclooctylideneacetic Acid (2-Cycloctylideneacetic Acid)

Cyclooctylideneacetic acid is a 168.23 g/mol cyclic acid analogue of VPA. In a study by Palaty J and Abbott F.S., mice with PTZ-induced seizure were subjected to 17 VPA-related cyclic and acyclic analogues. Of these 17 analogues, cyclooctylideneacetic acid was found to be the most potent anticonvulsant, even exceeding the potency of VPA with an ED50 dose (122.8 mg/kg) lower than VPA [55]. Moreover, the compound imparted a significantly reduced sedative effect on the treated mice at the observed ED50 value [55].

3.4.2. Tetramethylcyclopropyl Analogues

These analogues of VPA were designed to inhibit the conversion of VPA to its hepatotoxic metabolites [93]. The lack of potential transformation of this analogue is due to presence of two tertiary carbons at beta position to the carboxyl moiety [64].

2,2,3,3-Tetramethylcyclopropanecarboxylic Acid (TMCA)

TMCA is a 142 g/mol cyclopropyl analogue of VPA. It has weak anticonvulsant activity as compared to VPA, but has enhanced antiallodynic activity compared to parent drug, at doses that do not show any sedation effect [62]. This was shown in SNL mice model for tactile allodynia where the antiallodynic effect was observed at ED50 value of 181 mg/kg vs. ED50 value of 269 mg/kg of VPA 60 min post dosage [62].

In a fashion similar to the production of VPA amides with improved potency, TMCA amide derivatives were also studied as discussed in below sections.

2,2,3,3-Tetramethylcyclopropanecarboxamide (TMCD)

TMCD is a 141 g/mol cyclopropyl analogue of VPD. Okada et al. observed the analogue to have better anticonvulsant activity and lesser teratogenicity in mice embryos than VPA [64]. Consistent finding was also reported in rats, where reduced fetal skeletal abnormalities were observed as compared to VPA [63]. Hence, the analogue was suggested as a possible candidate for VPA replacement. Similar to TMCA, TMCD was also found to be potent antiallodynic drug with ED50 of 85 mg/kg [62].

N-Methoxy-TMCD (MTMCD)

It is a 154 g/mol derivative of TMCD, where the hydrogen atom of NH2 in TMCD is substituted with a methoxy group. MTMCD is a broad-spectrum anticonvulsant [63,94]. In the same study by Okada et al., enhanced anticonvulsant activity for MTMCD in comparison to VPA was observed, accompanied with less teratogenicity shown in vivo [64]. This compound was found to have 18.5 times more potency than VPA in rat subcutaneous metrazol (scMet) test and 4.5 times in MES test. It also has a wider safety margin (8 times the protective index (PI = TD50/ED50) of VPA) [64]. Among other cyclopropyl analogues of VPA, MTMCD showed best antiallodynic activity with ED50 value of 41 mg/kg [62].

Alpha-Fluro-TMCD

As mentioned, fluorinated VPA analogues show reduced hepatotoxicity but were also accompanied by reduced anticonvulsant activity [24,25,92]; this limitation was overcome by fluorination of TMCD [65]. Alpha-fluoro TMCD showed 120 times more potent anticonvulsant activity in scMET rat model than VPA [65]. It also showed higher potency in other in vivo test (kindled rat model, 6 Hz test and pilocarpine induced seizure in rat) and was found to be non-teratogenic with better safety margin than VPA, due to which it was proposed to be a potent candidate of CNS therapeutics [65].

Other compounds in this category are cyclohexanecarboxylic acid and its methylated form. Cyclohexanecarboxylic acid, a 128.17 g/mol analogue, showed promise with reduced neurotoxicity, though it still maintains the low potency of VPA [90]. In contrast, the 142.2 g/mol methylated analogue, i.e., 1-methylcyclohexane carboxylic acid depicted higher potency, but had a fatally increased neurotoxic potential [90].

3.5. Urea Derivatives of VPA

In the studies targeted at understanding the structure–activity relationships between VPA and its adverse effects, a number of urea derivatives have also been synthesized. The three compounds showing promise as future anticonvulsants are derived from VPA amide derivatives, and have not only improved anticonvulsant activity but also broader spectrum [56].

3.5.1. Valnoctylurea (VCU, 2-Ethyl-3-methylpentanoyl Urea)

VCU is a 186 g/mol urea derivative of VCA. VCU along with diisopropyl acetic acid (DIU) has shown tremendous anticonvulsant potential in scMET and MES seizure model, even better than amide derivatives of VPA [56]. The observed ED50 values for VCU are 14 mg/kg and 48 mg/kg in scMET seizures and 6Hz seizures, respectively, which was much better than those observed for VPA (646 mg/kg and 310 mg/kg respectively) [56]. In addition, VCU also has a lower teratogenic effect, leading to its acceptance as a safer derivative of VPA [56].

3.5.2. Propyl Isopropylacetyl Urea (PIU)

PIU is a 186 g/mol urea derivative of PID with the characteristic C-2 chiral centre. The enantioselective anticonvulsant effect of (R) and (S)-PIU was consistently observed in both MES and scMET-induced seizures [56]. In MES model, an ED50 value of 16 mg/kg was determined for the racemic mixture of PIU enantiomers, whereas individual R-PIU and S-PIU enantiomers had ED50 36 mg/kg and 18 mg/kg respectively [56]. Opposite results were observed in scMET model, where (R)-PIU had better efficacy with ED50 of 22 mg/kg that was significantly lower than S-PIU (ED50 = 37 mg/kg) and racemic-PIU (ED50 = 45 mg/kg) [56]. Results similar to scMET model was also observed for 6Hz model.

Teratogenic effect of (R)-PIU was observed at doses 5 to 6 times higher than the its ED50 [56]. This effect was greater than the S enantiomer. The significant difference in the toxicity of the two enantiomers can be ascertained as (R)-PIU has 54% embryotoxicity as compared to 10% of (S)-PIU [56]. The R isomer also leads in causing neural tube defects in the exposed embryos [56]. Yet the safety margin of both the enantiomers was better than VPA at their effective doses.

3.5.3. Diisopropyl Acetyl Urea (DIU)

DIU is a 186 g/mol urea derivative of diisopropyl acetyl amide (DIA). DIU has shown itself to be a promising anticonvulsant against 6Hz seizures with ED50 of 49 mg/kg that is sufficiently lower than VPA (310 mg/kg) [56]. It also showed better results than VPA in scMET and MES model with ED50 value of 16 mg/kg and 33 mg/kg, respectively, compared to ED50 value of 646 mg/kg and 485 mg/kg of VPA. Like other urea derivatives of VPA amide, DIU has better safety margin than VPA [56].

3.6. Conjugation Products of VPA

Valrocemide (TV1901, VGD)

VGD is a 200.28 g/mol amide derivative conjugation product of VPA and glycinamide. The conjugate was targeted to maximize the brain penetration [95]. Drug-distribution study performed by Blotnik et al. documented 4 times higher brain-to-plasma ratio of VGD than VPA in rats, thus implying better brain distribution of the conjugate [96]. VGD turned out to be a VPA-like broad-spectrum anticonvulsant [57]. VGD has proven itself to show doubly potent anticonvulsant activity than VPA and can effectively counter MES, 6-Hz psychomotor seizures (even at 44 mA stimulation), PTZ-, picrotoxin-, and bicuculline-induced seizures in rat model. VGD lagged behind VPA only in managing seizures of hippocampal kindled rats. The compound has reached Phase II clinical trials as an AED for patients with refractory epilepsy [97].

VGD also lacks a carboxylic moiety, thus its teratogenic potential is essentially missing and, therefore, no teratogenic effect of the compound was observed in rats, rabbits or SWV mice [57].

3.7. Prodrugs (Sugar Esters of VPA)

Unlike the other compounds discussed above, the sugar esters do not aim to change the VPA-related adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Sugar esters as prodrugs of VPA were developed as slow-release formulations of VPA to counter its limited plasma half-life, though they were also found to exert direct action on the brain. Amongst these esters, dimethylenexylitol valproate (VDMX) turned up as the most potent compound with its effective dose as low as 100 times that of VPA in suppressing spontaneous epileptiform activities (SEA) in rat hippocampal slices [60]. Also, VDMX showed best protective index in PTZ test [60]. VDMX shows good activity in entorhinal cortex late recurrent discharges (LRD) model for pharmacoresistant epilepsy, even though VPA fails to exert any significant effect on suppressing epileptiform activity in LRDs [59]. It was speculated that since LRD primarily depend on glutamatergic mechanisms, VDMX might strongly affect glutamatergic synaptic transmissions to exert its actions.

4. Conclusions

Introduced in clinical practice about 60 years ago, valproic acid still represents one of the most efficient AED targeting broad spectrum of epilepsy types. Emerging evidence also demonstrates its use in other neurological disorders such as migraine, bipolar disorder and neuropathic pain. However, its use in pregnant women with epilepsy (WWE) has shown to be associated with teratogenic effects on the developing foetus leading to congenital abnormalities. In addition, hepatotoxicity is another adverse effect commonly experienced with VPA therapy.

Numerous attempts have been made by various research groups to modify VPA structure. These were focused on altering one of the factors deemed responsible for its teratogenic behaviour or on avoiding the formation of its hepatotoxic metabolites (4-ene-VPA and 2,4-diene-VPA) while simultaneously increasing or maintaining its anticonvulsant activity and potency. This review has meticulously accounted for all the structural derivatives and analogues of VPA, discussing their pharmacological and toxicological profiles tested in vivo. These included amide derivatives, acid analogues, fluorinated derivatives, cyclic analogues, urea derivatives, conjugation products and sugar esters. The modifications thus made, have proven themselves to be effective as anxiolytics, antiallodynics and better anticonvulsants than VPA. Furthermore, the majority of them have shown better potency and tolerability in vivo.

Among the developed amide derivatives, VCD and SPD were found to have potentially no teratogenicity, are broad spectrum AEDs just like VPA, and are under active investigations. VCD has shown itself to be non-teratogenic at therapeutic doses in animal models [98,99] and has an anticonvulsant profile comparable to SPD. Advantages of SPD over VCD are lower ED50 values in pilocarpine induced status epilepticus [66,100,101]. Even though the fluorinated derivatives of VPA have reduced hepatotoxicity and teratogenicity, they are not as effective anticonvulsants as VPA, thus stopping their development. A fluorinated hydroxamic acid derivative of; VPA 2-Fluoro-VPA-HA [61] and alpha-Fluoro-TMCD [65] proved to be good candidates as second generation VPA. Apart from this, effectiveness of VGD in controlling mouse 44mA 6Hz-induced seizures and its better brain distribution has led to its successful completion of a 13-week, phase II clinical trial in Europe with resistant patients with epilepsy [57,58,77].

This article provides necessary knowledgebase of existing modifications which may facilitate more rational attempts in making structural changes. These strategies will systematically enhance the therapeutic use of VPA-related compounds for better disease management.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Director, CSIR-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (IGIB), Anurag Agrawal, for his scientific vision and support. We are also thankful to the research scholar, Neha Kanojia, CSIR-IGIB, for her help in literature screening for the review. M.K.M. acknowledge Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), Govt. of India, S.K. (Samiksha Kukal) acknowledge Department of Biotechnology (DBT) and CSIR, Govt. of India, P.R.P. and S.B. acknowledge CSIR, Government of India, for their financial assistance. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions in improving the manuscript.

Abbreviations

VPA: valproic acid: CNS, central nervous system; AED, antiepileptic drug; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; OAT, organic anion transporters; CYP450, cytochrome P450; GABA-T, GABA transaminase; SSADH, succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase; GluR1/2, glutamate receptor subunits 1 and 2; SCN3A, sodium voltage-gated channel alpha subunit 3; HDAC, histone deacetylase; GABAR: GABA receptors; BDNF: brain derived neurotrophic factor; CCND2: cyclin D2; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; GSK3B: glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta; PKC: protein kinase C; ERK/BCL-2: extracellular regulated kinase—B-cell lymphoma 2 pathway; Bad: BCL2 associated agonist of cell death; CDK5: cyclin-dependent kinase 5; NEP: neprilysin; TGF-B: transforming growth factor beta; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor, IL-1B: interleukin 1 beta; CCR1: C-C chemokine receptor type 1; p-JNK: phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase; H3K9ac: histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation; Ngb: neuroglobin; Nrf2/HO-1: nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2—heme oxygenase-1 pathway; H3ac: histone 3 acetylation; H4ac: histone 4 acetylation; p21: cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor; MYC: master regulator of cell cycle entry and proliferative metabolism; CCND1: cyclin D1; NOTCH1: Notch homolog 1, translocation-associated; p63: tumor protein p63; IL-6: interleukin 6; ANF: atrial natriuretic peptide; MES, maximal electroshock stimulation; PTZ, pentylenetetrazole; VPD, valpromide; SOX9, SRY-Box Transcription Factor 9; RUNX2, Runt-related transcription factor 2; VCD, valnoctamide, VCA, valnoctic acid; SE, status epilepticus; SNL, spinal nerve ligation; Pc-G, Polycomb group; NMRI, Naval Medical Research Institute; SPD, sec-Butyl-propylacetamide; ED50, effective dose; NTD, neural tube defect; PID, propylisopropyl acetamide; GTCS, generalized tonic–clonic seizures; TMCA, 2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid; TMCD, 2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropanecarboxamide; MTMCD, N-methoxy-TMCD; scMET, subcutaneous Metrazol; VCU, valnoctylurea; DIU, diisopropyl acetyl urea; DIA, diisopropyl acetic acid. PIU, propyl isopropylacetyl urea; VGD, valrocemide; ADR, adverse drug reaction; SEA, spontaneous epileptiform activities; VDMX, dimethylenexylitol valproate; LRD, late recurrent discharges; WWE, women with epilepsy.

Author Contributions

R.K.: conceptualization and supervision. M.K.M., S.K. (Samiksha Kukal), P.R.P. and S.B.: original draft preparation. S.K. (Samiksha Kukal) and P.R.P.: editing. A.S., S.K. (Shrikant Kukreti), L.S., K.M. and Y.H.: manuscript revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) under Grant OLP1154 and OLP1142.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Perucca E. Pharmacological and Therapeutic Properties of Valproate: A Summary after 35 Years of Clinical Experience. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];CNS Drugs. 2002 16:695–714. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216100-00004. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12269862/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghodke-Puranik Y., Thorn C.F., Lamba J.K., Leeder J.S., Song W., Birnbaum A.K., Altman R.B., Klein T.E. Valproic Acid Pathway: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. [(accessed on 29 September 2020)];Pharm. Genom. 2013 23:236–241. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835ea0b2. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3696515/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López-Muñoz F., Baumeister A.A., Hawkins M.F., Álamo C. The Role of Serendipity in the Discovery of the Clinical Effects of Psychotropic Drugs: Beyond of the Myth. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2012;40:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meunier H., Carraz G., Neunier Y., Eymard P., Aimard M. Pharmacodynamic Properties of N-dipropylacetic acid. [(accessed on 29 September 2020)];Therapie. 1963 18:435–438. Available online: http://europepmc.org/article/med/13935231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diederich M., Chateauvieux S., Morceau F., Dicato M. Molecular and Therapeutic Potential and Toxicity of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 29 September 2020)];J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/479364. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20798865/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emrich H.M., Von Zerssen D., Kissling W., Moeller H.J. Therapeutic Effect of Valproate in Mania. [(accessed on 29 September 2020)];Am. J. Psychiatry. 1981 138:256. doi: 10.1176/ajp.138.2.256. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6779643/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabresi P., Galletti F., Rossi C., Sarchielli P., Cupini L.M. Antiepileptic drugs in Migraine: From Clinical Aspects to Cellular Mechanisms. [(accessed on 29 September 2020)];Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007 28:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.02.005. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165614707000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tariot P.N., Loy R., Ryan J.M., Porsteinsson A., Ismail S. Mood Stabilizers in Alzheimer’s Disease: Symptomatic and Neuroprotective Rationales. [(accessed on 29 September 2020)];Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2002 54:1567–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00153-9. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169409×02001539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loy R., Tariot P.N. Neuroprotective Properties of Valproate: Potential Benefit for AD and Tauopathies. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];J. Mol. Neurosci. 2002 19:303–307. doi: 10.1385/JMN:19:3:301. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12540056/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen N.M., Svanström H., Stenager E., Magyari M., Koch-Henriksen N., Pasternak B., Hviid A. The Use of Valproic Acid and Multiple Sclerosis. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2015 24:262–268. doi: 10.1002/pds.3692. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25111895/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaheta R., Nau H., Michaelis M., Cinatl J., Jr. Valproate and Valproate-Analogues: Potent Tools to Fight Against Cancer. [(accessed on 29 September 2020)];Curr. Med. Chem. 2012 9:1417–1433. doi: 10.2174/0929867023369763. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12173980/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phiel C.J., Zhang F., Huang E.Y., Guenther M.G., Lazar M.A., Klein P.S. Histone Deacetylase is a Direct Target of Valproic Acid, a Potent Anticonvulsant, Mood Stabilizer, and Teratogen. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];J. Biol. Chem. 2001 276:36734–36741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101287200. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11473107/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Göttlicher M., Minucci S., Zhu P., Krämer O.H., Schimpf A., Giavara S., Sleeman J.P., Coco F.L., Nervi C., Pelicci P.G., et al. Valproic Acid Defines a Novel Class of HDAC Inhibitors inducing Differentiation of Transformed Cells. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];EMBO J. 2001 20:6969–6978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.6969. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11742974/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradbury C.A., Khanim F.L., Hayden R., Bunce C.M., White D.A., Drayson M.T., Craddock C., Turner B.M. Histone Deacetylases in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Show a Distinctive Pattern of Expression that Changes Selectively in Response to Deacetylase Inhibitors. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Leukemia. 2005 19:1751–1759. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403910. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16121216/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jäger-Roman E., Deichl A., Jakob S., Hartmann A.M., Koch S., Rating D., Steldinger R., Nau H., Helge H. Fetal Growth, Major Malformations, and Minor Anomalies in Infants Born to Women Receiving Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 30 September 2020)];J. Pediatr. 1986 108:997–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(86)80949-0. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3086531/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terbach N., Shah R., Kelemen R., Klein P.S., Gordienko D., Brown N.A., Wilkinson C.J., Williams R.S. Identifying an Uptake Mechanism for the Antiepileptic and Bipolar Disorder Treatment Valproic acid Using the Simple Biomedical Model Dictyostelium. Pt 13 [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];J. Cell Sci. 2011 124:2267–2276. doi: 10.1242/jcs.084285. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21652627/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keane P.E., Simiand J., Mendes E., Santucci V., Morre M. The Effects of Analogues of Valproic Acid on Seizures Induced by Pentylenetetrazol and GABA Content in Brain of Mice. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Neuropharmacology. 1983 22:875–879. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(83)90134-X. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6413882/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman A.G., Meldrum B.S., Mendes E. Acute Anticonvulsant Activity of Structural Analogues of Valproic Acid and Changes in Brain GABA and Aspartate Content. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Life Sci. 1983 32:2023–2031. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90054-1. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6403794/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman A.G., Croucher M.J., Meldrum B.S. Anticonvulsant Activity of Intracerebroventricularly Administered Valproate and Valproate Analogues. A Dose-Dependent Correlation with Changes in Brain Aspartate and GABA Levels in DBA/2 Mice. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984 33:1459–1463. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90413-1. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6428419/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comelli N.C., Duchowicz P.R., Lobayan R.M., Jubert A.H., Castro E.A. QSPR Study of Valproic Acid and Its Functionalized Derivatives. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Mol. Inform. 2012 31:181–188. doi: 10.1002/minf.201100119. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27476963/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nau H., Hauck R.-S., Ehlers K. Valproic Acid-Induced Neural Tube Defects in Mouse and Human: Aspects of Chirality, Alternative Drug Development, Pharmacokinetics and Possible Mechanisms. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1991 69:310–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1991.tb01303.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1803343/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nau H., Löscher W. Pharmacologic Evaluation of Various Metabolites and Analogs of Valproic Acid: Teratogenic Potencies in mice. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1986 6:669–676. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(86)90180-6. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3086174/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lloyd K.A., Sills G. A Scientific Review: Mechanisms of Valproate-Mediated Teratogenesis. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Biosci. Horiz. Int. J. Stud. Res. 2013 6:2013. doi: 10.1093/biohorizons/hzt003. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/biohorizons/article/doi/10.1093/biohorizons/hzt003/302011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang W., Palaty J., Abbott F.S. Time Course of Alpha-Fluorinated Valproic Acid in Mouse Brain and Serum and Its Effect on Synaptosomal Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Levels in Comparison to Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997 Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9316822/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang W., Borel A.G., Abbott F.S., Fujimiya T. Fluorinated Analogues as Mechanistic Probes in Valproic Acid Hepatotoxicity: Hepatic Microvesicular Steatosis and Glutathione Status. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1995 8:671–682. doi: 10.1021/tx00047a006. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7548749/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neuman M.G., Shear N.H., Jacobson-Brown P.M., Katz G.G., Neilson H.K., Malkiewicz I.M., Cameron R.G., Abbott F. CYP2E1-Mediated Modulation of Valproic Acid-Induced Hepatocytotoxicity. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Clin. Biochem. 2001 34:211–218. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9120(01)00217-X. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11408019/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee M.S., Lee Y.J., Kim B.J., Shin K.J., Chung B.C., Baek D.J., Jung B.H. The Relationship between Glucuronide Conjugate Levels and Hepatotoxicity after Oral Administration of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Arch Pharm. Res. 2009 32:1029–1035. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1708-x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19641884/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaccara G., Messori A., Moroni F. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Valproic Acid—1988. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1988 15:367–389. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198815060-00002. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3149565/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romoli M., Mazzocchetti P., D’Alonzo R., Siliquini S., Rinaldi V.E., Verrotti A., Calabresi P., Costa C. Valproic Acid and Epilepsy: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Evidences. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019 17:926–946. doi: 10.2174/1570159X17666181227165722. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30592252/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levy R.H., Cenraud B., Loiseau P., Akbaraly R., Brachet-Liermain A., Guyot M., Gomeni R., Morselli P.L. Meal-Dependent Absorption of Enteric-Coated Sodium Valproate. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsia. 1980 21:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1980.tb04073.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6769666/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito M., Ikeda Y., Arnez J.G., Finocchiaro G., Tanaka K. The Enzymatic Basis for the Metabolism and Inhibitory Effects of Valproic Acid: Dehydrogenation of valproyl-CoA by 2-methyl-branched-chain acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1990 1034:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(90)90079-C. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2112956/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Argikar U.A., Remmel R.P. Effect of Aging on Glucuronidation of Valproic acid in Human Liver Microsomes and the Role of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT1A4, UGT1A8, and UGT1A10. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Drug Metab. Dispos. 2009 37:229–236. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.022426. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18838507/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan L., Yu J.T., Sun Y.P., Ou J.R., Song J.H., Yu Y. The influence of cytochrome oxidase CYP2A6, CYP2B6, and CYP2C9 Polymorphisms on the Plasma Concentrations of Valproic Acid in Epileptic Patients. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2010 112:320–323. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.01.002. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20089352/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rettie A.E., Rettenmeier A.W., Howald W.N., Baillie T.A. Cytochrome P-450—Catalyzed Formation of Delta 4-VPA, a Toxic Metabolite of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Science. 1987 235:890–893. doi: 10.1126/science.3101178. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3101178/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bialer M., Hussein Z., Raz I., Abramsky O., Herishanu Y., Pachys F. Pharmacokinetics of Valproic Acid in Volunteers after a Single Dose Study. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 1985 6:33–42. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510060105. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3921078/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metabolite Pattern of Valproic Acid. Part I: Gaschromatographic Determination of the Valproic Acid Metabolite Artifacts, Heptanone-3, 4- and 5-Hydroxyvalproic Acid Lactone-PubMed. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)]; Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/373770/ [PubMed]

- 37.Identification and Characterization of the Glutathione and N-Acetylcysteine Conjugates of (E)-2-propyl-2,4-pentadienoic Acid, a Toxic Metabolite of Valproic Acid, in Rats and Humans-PubMed. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)]; Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1676665/ [PubMed]

- 38.Kassahun K., Hu P., Grillo M.P., Davis M.R., Jin L., Baillie T.A. Metabolic activation of unsaturated derivatives of valproic acid. Identification of novel glutathione adducts formed through coenzyme A-dependent and -independent processes. [(accessed on 23 November 2021)];Chem. Biol. Interact. 1994 90:253–275. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)90014-0. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8168173/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rettenmeier A.W., Prickett K.S., Gordon W.P., Bjorge S.M., Chang S.L., Levy R.H., Baillie T.A. Studies on the Biotransformation in the Perfused Rat Liver of 2-n-Propyl-4-pentenoic Acid, a Metabolite of the Antiepileptic Drug Valproic Acid. Evidence for the Formation of Chemically Reactive Intermediates-PubMed. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)]; Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2858383/ [PubMed]

- 40.Baillie T.A. Metabolic Activation of Valproic Acid and Drug-Mediated Hepatotoxicity. Role of the Terminal Olefin, 2-n-propyl-4-pentenoic Acid. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1988 1:195–199. doi: 10.1021/tx00004a001. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2979731/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson G.M., Naunton M. Valproate: A Simple Chemical with so Much to Offer. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2005 30:417–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2005.00671.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16164485/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riva R., Albani F., Contin M., Baruzzi A., Altomare M., Merlini G.P., Perucca E. Mechanism of Altered Drug Binding to Serum Proteins in Pregnant Women: Studies with Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Ther. Drug Monit. 1984 6:25–30. doi: 10.1097/00007691-198403000-00006. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6424276/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svensson C.K., Woodruff M.N., Baxter J.G., Lalka D. Free Drug Concentration Monitoring in Clinical Practice. Rationale and Current Status. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1986 11:450–469. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198611060-00003. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3542337/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiang T.K.L., Ho P.C., Anari M.R., Tong V., Abbott F.S., Chang T.K.H. Contribution of CYP2C9, CYP2A6, and CYP2B6 to Valproic Acid Metabolism in Hepatic Microsomes from Individuals with the CYP2C9*1/*1 Genotype. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Toxicol. Sci. 2006 94:261–271. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl096. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16945988/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.VanDongen A.M.J., VanErp M.G., Voskuyl R.A. Valproate Reduces Excitability by Blockage of Sodium and Potassium Conductance. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsia. 1986 27:177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb03525.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3084227/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johannessen C.U., Johannessen S.I. Valproate: Past, Present, and Future. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];CNS Drug Rev. 2003 9:199–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2003.tb00249.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12847559/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van den Berg R.J., Kok P., Voskuyl R.A. Valproate and Sodium Currents in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Exp. Brain Res. 1993 93:279–287. doi: 10.1007/BF00228395. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8387930/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan N.N., Tang H.L., Lin G.W., Chen Y.H., Lu P., Li H.J., Gao M.M., Zhao Q.H., Yi Y.H., Liao W.P., et al. Epigenetic Downregulation of Scn3a Expression by Valproate: A Possible Role in Its Anticonvulsant Activity. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Mol. Neurobiol. 2017 154:2831–2842. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9871-9. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27013471/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bialer M., Johannessen S.I., Kupferberg H.J., Levy R.H., Perucca E., Tomson T. Progress Report on New Antiepileptic Drugs: A Summary of the Seventh Eilat Conference (EILAT VII) [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 2004 61:1–48. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2004.07.010. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15570674/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blotnik S., Bergman F., Bialer M. Disposition of Valpromide, Valproic Acid, and Valnoctamide in the Brain, Liver, Plasma, and Urine of Rats-PubMed. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)]; Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8723737/ [PubMed]

- 51.White H.S., Alex A.B., Pollock A., Hen N., Shekh-Ahmad T., Wilcox K.S., McDonough J.H., Stables J.P., Kaufmann D., Yagen B., et al. A New Derivative of Valproic Acid Amide Possesses a Broad-Spectrum Antiseizure Profile and Unique Activity against Status Epilepticus and Organophosphate Neuronal Damage. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Epilepsia. 2012 53:134–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03338.x. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22150444/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bialer M., Johannessen S.I., Kupferberg H.J., Levy R.H., Perucca E., Tomson T. Progress Report on New Antiepileptic Drugs: A Summary of the Eigth Eilat Conference (EILAT VIII) [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 2007 73:1–52. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.10.008. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17158031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Düsing R.H. Single-Dose Tolerance and Pharmacokinetics of 2-n-propyl-2(E)-pentenoate (delta 2(E)-valproate) in Healthy Male Volunteers. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Pharm. Weekbl. Sci. 1992 14:152–158. doi: 10.1007/BF01962708. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1502017/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hauck R.S., Nau H. Asymmetric Synthesis and Enantioselective Teratogenicity of 2-n-propyl-4-pentenoic Acid (4-en-VPA), an Active Metabolite of the Anticonvulsant Drug, Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Toxicol. Lett. 1989 49:41–48. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(89)90099-4. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2510370/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Palaty J., Abbott F.S. Structure-Activity Relationships of Unsaturated Analogues of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 18 November 2021)];J. Med. Chem. 1995 38:3398–3406. doi: 10.1021/jm00017a024. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7650693/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimshoni J.A., Bialer M., Wlodarczyk B., Finnell R.H., Yagen B. Potent Anticonvulsant Urea Derivatives of Constitutional Isomers of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];J. Med. Chem. 2007 50:6419–6427. doi: 10.1021/jm7009233. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17994680/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Isoherranen N., Woodhead J.H., White H.S., Bialer M. Anticonvulsant Profile of Valrocemide (TV1901): A New Antiepileptic Drug. Epilepsia. 2001;42:831–836. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.042007831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.O’Shea S., Johnson K., Clark R., Sliwkowski M.X., Erickson S.L. Effects of In Vivo Heregulin Beta1 Treatment in Wild-Type and ErbB Gene-Targeted Mice Depend on Receptor Levels and Pregnancy. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Am. J. Pathol. 2001 158:1871–1880. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64144-2. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11337386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Armand V., Louvel J., Pumain R., Heinemann U. Effects of New Valproate Derivatives on Epileptiform Discharges Induced by Pentylenetetrazole or Low Mg2+ in Rat Entorhinal Cortex-Hippocampus Slices. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 1998 32:345–355. doi: 10.1016/S0920-1211(98)00030-8. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9839774/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Armand V., Louvel J., Pumain R., Ronco G., Villa P. Effects of Various Valproic Acid Derivatives on Low-Calcium Spontaneous Epileptiform Activity in Hippocampal Slices. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 1995 22:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00044-5. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8991785/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gravemann U., Volland J., Nau H. Hydroxamic acid and Fluorinated Derivatives of Valproic Acid: Anticonvulsant Activity, Neurotoxicity and Teratogenicity. [(accessed on 10 November 2021)];Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2008 30:390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.03.060. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18455366/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Winkler I., Sobol E., Yagen B., Steinman A., Devor M., Bialer M. Efficacy of antiepileptic tetramethylcyclopropyl analogues of valproic acid amides in a rat model of neuropathic pain. [(accessed on 18 November 2021)];Neuropharmacology. 2005 49:1110–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.008. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16055160/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blotnik S., Bergman F., Bialer M. Disposition of two tetramethylcyclopropane analogues of valpromide in the brain, liver, plasma and urine of rats. [(accessed on 18 November 2021)];Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 1998 6:93–98. doi: 10.1016/S0928-0987(97)00081-X. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9795021/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okada A., Onishi Y., Yagen B., Shimshoni J.A., Kaufmann D., Bialer M., Fujiwara M. Tetramethylcyclopropyl Analogue of the Leading Antiepileptic Drug, Valproic Acid: Evaluation of the Teratogenic Effects of Its Amide Derivatives in NMRI Mice. [(accessed on 18 November 2021)];Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2008 82:610–621. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20490. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18671279/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pessah N., Bialer M., Wlodarczyk B., Finnell R.H., Yagen B. Alpha-fluoro-2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropanecarboxamide, a Novel Potent Anticonvulsant Derivative of a Cyclic Analogue of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 18 November 2021)];J. Med. Chem. 2009 52:2233–2242. doi: 10.1021/jm900017f. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19296679/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shekh-Ahmad T., Mawasi H., McDonough J.H., Yagen B., Bialer M. The Potential of Sec-Butylpropylacetamide (SPD) and Valnoctamide and their Individual Stereoisomers in Status Epilepticus. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsy Behav. 2015 49:298–302. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.04.012. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25979572/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Safety and Efficacy of NPS 1776 in the Acute Treatment of Migraine Headaches-Full Text View-ClinicalTrials.gov. [(accessed on 28 September 2020)]; Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00172094?id=NCT00172094&draw=2&rank=1&load=cart.

- 68.Löscher W., Nau H. Pharmacological Evaluation of Various Metabolites and Analogues of Valproic Acid. Anticonvulsant and Toxic Potencies in Mice. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Neuropharmacology. 1985 24:427–435. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90028-0. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3927183/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okada A., Aoki Y., Kushima K., Kurihara H., Bialer M., Fujiwara M. Polycomb Homologs are Involved in Teratogenicity of Valproic Acid in Mice. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2004 70:870–879. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20085. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15523661/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paradis F.H., Hales B.F. Exposure to Valproic Acid Inhibits Chondrogenesis and Osteogenesis in Mid-Organogenesis Mouse Limbs. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Toxicol. Sci. 2013 131:234–241. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs292. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23042728/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bialer M., Rubinstein A. Pharmacokinetics of Valpromide in Dogs after Various Modes of Administration. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 1984 5:177–183. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510050211. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6430363/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bialer M., Rubinstein A., Raz I., Abramsky O. Pharmacokinetics of Valpromide after Oral Administration of a Solution and a Tablet to Healthy Volunteers. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1984 27:501–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00549603. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6440792/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lindekens H., Smolders I., Khan G.M., Bialer M., Ebinger G., Michotte Y. In Vivo Study of the Effect of Valpromide and Valnoctamide in the Pilocarpine Rat Model of Focal Epilepsy. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Pharm. Res. 2000 17:1408–1413. doi: 10.1023/A:1007559208599. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11205735/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kaufmann D., Yagen B., Minert A., Wlodarczyk B., Finnell R.H., Schurig V., Devor M., Bialer M. Evaluation of the Antiallodynic, Teratogenic and Pharmacokinetic Profile of Stereoisomers of Valnoctamide, an Amide Derivative of a Chiral Isomer of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Neuropharmacology. 2010 58:1228–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.03.004. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20230843/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okada A., Kushima K., Aoki Y., Bialer M., Fujiwara M. Identification of Early-Responsive Genes Correlated to Valproic Acid-Induced Neural Tube Defects in Mice. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2005 73:229–238. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20131. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15799026/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bialer M., White H.S. Key Factors in the Discovery and Development of New Antiepileptic Drugs. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010 9:68–82. doi: 10.1038/nrd2997. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20043029/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bialer M., Yagen B. Valproic Acid: Second Generation. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Neurotherapeutics. 2007 4:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2006.11.007. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17199028/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kaufmann D., West P.J., Smith M.D., Yagen B., Bialer M., Devor M., White H.S., Brennan K.C. sec-Butylpropylacetamide (SPD), a New Amide Derivative of Valproic Acid for the Treatment of Neuropathic and Inflammatory Pain. [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Pharmacol. Res. 2017 117:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.030. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27890817/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hen N., Shekh-Ahmad T., Yagen B., McDonough J.H., Finnell R.H., Wlodarczyk B., Bialer M. Stereoselective Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Analysis of sec-Butylpropylacetamide (SPD), a New CNS-Active Derivative of Valproic Acid with Unique Activity against Status Epilepticus. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];J. Med. Chem. 2013 2256:6467–6477. doi: 10.1021/jm4007565. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23879329/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haj-Yehia A., Bialer M. Structure–Pharmacokinetic Relationships in a Series of Valpromide Derivatives with Antiepileptic Activity. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Pharm. Sci. 1989 6:683–689. doi: 10.1023/a:1015934321764. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2510141/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Isoherranen N., Yagen B., Woodhead J.H., Spiegelstein O., Blotnik S., Wilcox K.S., Finnell R.H., Bennett G.D., White H.S., Bialer M. Characterization of the Anticonvulsant Profile and Enantioselective Pharmacokinetics of the Chiral Valproylamide Propylisopropyl Acetamide in Rodents. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003 138:602–613. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705076. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12598414/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mareš P., Kubová H., Hen N., Yagen B., Bialer M. Derivatives of Valproic Acid are Active against Pentetrazol-Induced Seizures in Immature Rats. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Epilepsy Res. 2013 106:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2013.06.001. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23815889/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Spiegelstein O., Yagen B., Levy R.H., Finnell R.H., Bennett G.D., Roeder M., Schurig V., Bialer M. Stereoselective Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Propylisopropyl Acetamide, a CNS-Active Chiral Amide Analog of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Pharm. Res. 1999 16:1582–1588. doi: 10.1023/A:1018960722284. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10554101/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spiegelstein O., Bialer M., Radatz M., Nau H., Yagen B. Enantioselective Synthesis and Teratogenicity of Propylisopropyl Acetamide, a CNS-Active Chiral Amide Analogue of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Chirality. 1999 11:645–650. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1999)11:8<645::AID-CHIR6>3.0.CO;2-7. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10467316/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bialer M., Johannessen S.I., Levy R.H., Perucca E., Tomson T., White H.S. Progress Report on New Antiepileptic Drugs: A Summary of the Tenth Eilat Conference (EILAT X) [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 2010 92:89–124. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.09.001. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20970964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Loescher W. Anticonvulsant Activity of Metabolites of Valproic Acid-PubMed. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)]; Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6784685/

- 87.Loscher W., Nau H. Distribution of Valproic Acid and Its Metabolites in Various Brain Areas of Dogs and Rats after Acute and Prolonged Treatment-PubMed. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)]; Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6411902/ [PubMed]

- 88.Löscher W., Nau H., Marescaux C., Vergnes M. Comparative Evaluation of Anticonvulsant and Toxic Potencies of Valproic Acid and 2-en-valproic Acid in Different Animal Models of Epilepsy. [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1984 99:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(84)90243-7. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6428923/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Strichartz G.R., Wang G.K. Rapid Voltage-Dependent Dissociation of Scorpion Alpha-Toxins Coupled to Na Channel Inactivation in Amphibian Myelinated Nerves. [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];J. Gen. Physiol. 1986 88:413–435. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.3.413. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2428923/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Isoherranen N., Yagen B., Bialer M. New CNS-Active Drugs Which are Second-Generation Valproic Acid: Can They Lead to the Development of a Magic Bullet? [(accessed on 10 September 2020)];Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2003 16:203–211. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200304000-00014. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12644750/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tang W., Abbott F.S. A Comparative Investigation of 2-Propyl-4-Pentenoic Acid (4-ene VPA) and its α-Fluorinated Analogue: Phase II Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1997;25:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kesterson J.W., Granneman G.R., Machinist J.M. The Hepatotoxicity of Valproic acid and Its Metabolites in Rats. I. Toxicologic, Biochemical and Histopathologic Studies. Hepatology. 1984;4:1143–1152. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sobol E., Bialer M., Yagen B. Tetramethylcyclopropyl Analogue of a Leading Antiepileptic Drug, Valproic acid. Synthesis and Evaluation of Anticonvulsant Activity of Its Amide Derivatives. [(accessed on 18 November 2021)];J. Med. Chem. 2004 47:4316–4326. doi: 10.1021/jm0498351. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15294003/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bialer M., Hadad S., Kadry B., Abdul-Hai A., Haj-Yehia A., Sterling J., Herzig Y., Yagen B. Pharmacokinetic Analysis and Antiepileptic Activity of Tetra-Methylcyclopropane Analogues of Valpromide. [(accessed on 18 November 2021)];Pharm. Res. 1996 13:284–289. doi: 10.1023/A:1016055517724. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8932450/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bialer M., Johannessen S.I., Levy R.H., Perucca E., Tomson T., White H.S. Progress Report on New Antiepileptic Drugs: A Summary of the Ninth Eilat Conference (EILAT IX) [(accessed on 25 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 2009 83:1–43. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.09.005. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19008076/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Blotnik S., Bergman F., Bialer M. The Disposition of Valproyl Glycinamide and Valproyl Glycine in Rats. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:873–878. doi: 10.1023/A:1012143631873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bialer M., Johannessen S.I., Kupferberg H.J., Levy R.H., Loiseau P., Perucca E. Progress Report on New Antiepileptic Drugs: A Summary of the Fifth Eilat Conference (EILAT V) [(accessed on 22 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 2001 43:11–58. doi: 10.1016/S0920-1211(00)00171-6. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11137386/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wlodarczyk B.J., Ogle K., Lin L.Y., Bialer M., Finnell R.H. Comparative Teratogenicity Analysis of Valnoctamide, Risperidone, and Olanzapine in Mice. [(accessed on 26 November 2021)];Bipolar Disord. 2015 17:615–625. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12325. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26292082/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bialer M., Johannessen S.I., Levy R.H., Perucca E., Tomson T., White H.S. Progress Report on New Antiepileptic Drugs: A Summary of the Eleventh Eilat Conference (EILAT XI) [(accessed on 26 November 2021)];Epilepsy Res. 2013 103:2–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.10.001. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23219031/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mawasi H., Shekh-Ahmad T., Finnell R.H., Wlodarczyk B.J., Bialer M. Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Analysis of CNS-Active Constitutional Isomers of Valnoctamide and sec-Butylpropylacetamide—Amide Derivatives of Valproic Acid. [(accessed on 26 November 2021)];Epilepsy Behav. 2015 46:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.02.040. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25863940/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pouliot W., Bialer M., Hen N., Shekh-Ahmad T., Kaufmann D., Yagen B., Ricks K., Roach B., Nelson C., Dudek F.E. A Comparative Electrographic Analysis of the Effect of sec-butyl-propylacetamide on Pharmacoresistant Status Epilepticus. [(accessed on 26 November 2021)];Neuroscience. 2013 231:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.005. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23159312/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]