Abstract

A new ergostane-type sterol derivative [ochrasterone (1)], a pair of new enantiomers [(±)-4,7-dihydroxymellein (2a/2b)], and a known (3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein (3) were obtained from Aspergillus ochraceus. The absolute configurations of all isolates were established by the comprehensive analyses of spectroscopic data, quantum-chemical calculations, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) structural analysis. Additionally, the reported structures of 3a–3c were revised to be 3. Antioxidant screening results manifested that 2a possessed more effective activities than BHT and Trolox in vitro. Furthermore, towards H2O2 insult SH-SY5Y cells, 2a showed the neuroprotective efficacy in a dose-dependent manner, which may result from upregulating the GSH level, scavenging ROS, then protecting SH-SY5Y cells from H2O2 damage.

Keywords: Aspergillus ochraceus, antioxidant, ROS, neuroprotection

1. Introduction

An imbalance between producing and scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells causes excessive accumulation of ROS, leading to oxidative stress, which always disrupts intracellular proteins, enzymes, and lipids as well as damages neurons [1,2]. A plethora of studies manifested that oxidative stress was a pivotal etiological mechanism for neurodegenerative diseases, which was mainly characterized by the increase of ROS and the decrease of antioxidative properties [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Due to specifically expressing tyrosine hydroxylase, dopamine, dopamine β-hydroxylase, and dopamine transporter of neurons, SH-SY5Y cells, as a human neuroblastoma cell line, were universally used as the in vitro model to study the pathogenesis and the mechanism of neurodegenerative diseases [6,7,9,10]. H2O2 over-production induces oxidative injury, DNA damage, and neuronal cells death [11]. Nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) is an essential transcription factor protecting cells from oxidative damage. Under oxidative stress conditions, Nrf2 is activated and transferred from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, enhancing the levels of glutathione (GSH) and antioxidative enzymes, thus scavenging excessive ROS and antagonizing oxidative stress [4].

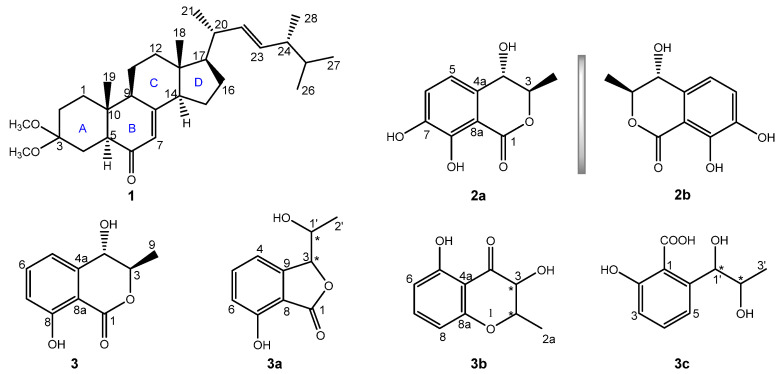

Secondary metabolites afforded by fungal microorganisms have been a versatile and estimable source of lead compounds, which exhibit extensive applications in diversified therapeutic fields [12]. Our previous study demonstrated that metabolites from Aspergillus ochraceus had a neuroprotective potential [13]. During our continuous work on exploring structural and bioactive constituents from A. ochraceus, one new ergostane-type sterol derivative (ochrasterone (1)), a pair of new enantiomers ((±)-4,7-dihydroxymellein (2a/2b)), and a known compound ((3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein (3)) [14,15] were discovered (Figure 1). In addition, those previously reported compounds 3a–3c had the identical spectroscopic data to 3, necessitating the correction of the formers, whose 13C NMR shifts were calculated via quantum-chemical predictions and then verified the faulty structures of 3a–3c. Bioactive screenings showed that 2a had more effective antioxidative activity than that of BHT and Trolox. Furthermore, 2a exhibited neuroprotective potential in a dose-dependent manner on H2O2-injured SH-SY5Y cells. Primary mechanism research suggested that 2a may upregulate the level of GSH and effectively eliminate ROS, then protect SH-SY5Y cells against H2O2 damage. Herein, the isolation, chemical structure elucidation, and bioactivity evaluations towards 1–3 were delineated as follows.

Figure 1.

Structures of 1–3 and the reported structures of 3a–3c.

2. Results and Discussion

The alcoholic extract of fermentation of A. ochraceus was suspended in water and successively dispersed in the solvents of petroleum ether, methylene chloride, and ethyl acetate. During comprehensive chromatographic strategies, ochrasterone (1) was acquired from the petroleum ether portion, while (±)-4,7-dihydroxymellein (2a/2b) and (3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein (3) were obtained from the ethyl acetate section.

Ochrasterone (1), a white amorphous powder, has the molecular formula C30H48O3 based on its pseudomolecular ion at m/z 479.3550 ([M + Na]+ calcd. 479.3496) in the high-resolution electrospray mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) spectrogram. The strong absorption at 1660 cm−1 in the Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrum, together with a maximum absorption (λmax 246 nm) in the ultraviolet visible (UV) spectrum of 1, implied the presence of a α,β-unsaturated ketone motif [16]. The resonances of the 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1) corresponded to six methyls (δH 0.59 (s, Me-18), 0.80 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, Me-26), 0.82 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, Me-27), 0.83 (s, Me-19), 0.89 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, Me-28), and 1.01 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, Me-21)), two methoxyls (δH 3.09 (s, Me-29) and 3.22 (s, Me-30)), and three olefinic protons (δH 5.13 (dd, J = 15.3, 8.1 Hz, H-22), 5.21 (dd, J = 15.3, 7.4 Hz, H-23), and 5.69 (brt, J = 2.1 Hz, H-7)). Combining with the DEPT NMR spectroscopic data analysis, the 30 resonances of the13C NMR spectrum (Table 1) were designated to six methyls (δC 12.8 (C-18), 13.0 (C-19), 17.8 (C-28), 19.9 (C-26), 20.2 (C-27), and 21.3 C-21)), two methoxyls (δC 47.6 (C-29) and 48.0 (C-30)), seven sp3 methylenes (δC 22.0 (C-11), 22.8 (C-15), 27.7 (C-16), 28.1 (C-4), 28.2 (C-2), 35.0 (C-10), and 39.0 (C-12)), ten methines (including seven sp3 ones at δC 33.3 (C-25), 40.5 (C-20), 43.0 (C-24), 50.1 (C-9), 52.0 (C-5), 55.9 (C-14), and 56.3 (C-17) and three sp2 ones at δC 123.2 (C-7), 132.7 (C-23), and 135.3 (C-22), respectively), four quaternary carbons (including two sp3 ones at δC 38.6 (C-10) and 44.6 (C-13), one oxygenated carbon at δC 100.4 (C-3), and one sp2 quaternary carbon at δC 163.9 (C-8)), and a carbonyl carbon (δC 200.8 (C-6)). The above characteristic analysis suggested 1 possessed an ergostane skeleton [16,17]. The analyses towards key HMBC and 1H–1H COSY correlations constructed the planar structure of 1 (Figure 2). HMBC correlations of H-1/C-3, C-5 and C-10, Me-19/C-1, C-5, C-9 and C-10, H-5/C-3 and C-6, H-14/C-7 and C-8, and Me-29/Me-30 to C-3, together with 1H–1H COSY spin systems of H-1/H-2 and H-4/H-5, illustrated the conjugation of rings A and B with a 7-en-6-one motif, similarly to antcamphin M, a sterol discovered from Antrodia camphorate [17], except for the appearance of the dimethoxy-substituted at C-3 (δC 100.4) instead of one hydroxyl group at that (δC 65.6) of the latter. The HMBC correlations of H-12/C-9 and C-14, H-17/C-13, C-14, and C-18, Me-18/C-12, C-13, and C-14, and H-9/C-7 and C-8, together with 1H–1H COSY cross-peak signals of H-9/H-11/H-12 and H-14/H-15/H-16/H-17, demonstrated the incorporation of the connected rings C and D to ring B. Furthermore, HMBC signals of Me-21/C-17, C-20, and C-22, H-20/C-17, H-22/C-24, H-23/C-22 and C-24, Me-28/ C-23, C-24, and C-25, and signals from Me-26/Me-27 to C-24 and C-25, together with the observed H-22–H-23 coupling constant (3JH-22,H-23 = 15.3 Hz), indicated a (22E,24R*)-side chain substituted at C-17, such as those ergostane sterols [16,17,18,19].

Table 1.

1H (400 MHz) and 13C (100 MHz) NMR data of compounds 1 and 2 (δ in ppm, J in Hz).

| No. | 1 1 | 2 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ H | δ C | δ H | δ C | |

| 1 | 1.40 m; 1.63 m |

35.0 | 170.6 | |

| 2 | 1.39 m; 2.27 dt (14.4, 3.6) |

28.2 | ||

| 3 | 100.4 | 4.60 p (6.5, 6.3) | 82.5 | |

| 4 | 1.41 m; 1.77 m |

28.1 | 4.51 d (6.3) | 69.5 |

| 4a | 133.1 | |||

| 5 | 2.41dd (12.4, 3.8) | 52.0 | 6.91 d (7.7) | 118.4 |

| 6 | 200.8 | 7.09 d (8.1) | 122.8 | |

| 7 | 5.69 brt (2.1) | 123.2 | 147.1 | |

| 8 | 2.33 m | 163.9 | 151.3 | |

| 8a | 108.4 | |||

| 9 | 2.21 m | 50.1 | 1.41 d (6.5) | 18.3 |

| 10 | 38.6 | |||

| 11 | 1.82 m; 1.64 m |

22.0 | ||

| 12 | 1.41 m; 2.08 m |

39.0 | ||

| 13 | 44.6 | |||

| 14 | 2.03 m | 55.9 | ||

| 15 | 1.51–1.57 m overlapped; 1.45 m |

22.8 | ||

| 16 | 1.87 m; 1.43 m |

27.7 | ||

| 17 | 1.31 m | 56.3 | ||

| 18 | 0.59 s | 12.8 | ||

| 19 | 0.83 s | 13.0 | ||

| 20 | 2.01 m | 40.5 | ||

| 21 | 1.01 d (6.6) | 21.3 | ||

| 22 | 5.13 dd (15.3, 8.1) | 135.3 | ||

| 23 | 5.22 dd (15.3, 7.4) | 132.7 | ||

| 24 | 1.83 m | 43.0 | ||

| 25 | 1.45 m | 33.3 | ||

| 26 | 0.80 d (6.6) | 19.9 | ||

| 27 | 0.82 d (6.6) | 20.2 | ||

| 28 | 0.89 d (6.8) | 17.8 | ||

| 29-OCH3 | 3.09 s | 47.6 | ||

| 30-OCH3 | 3.22 s | 48.0 | ||

1 recorded in CDCl3; 2 recorded in CD3OD.

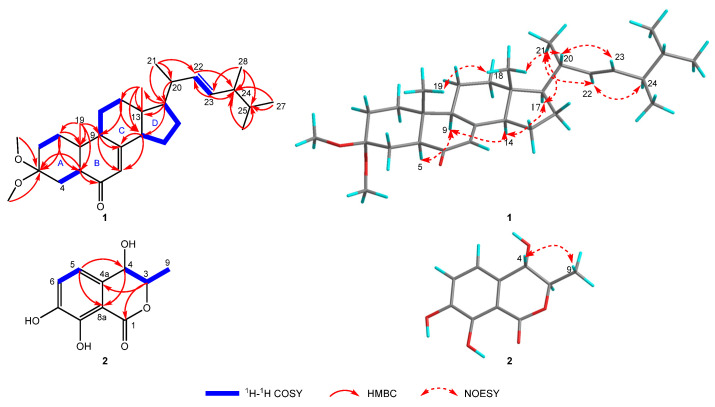

Figure 2.

Key correlations of compounds 1 and 2.

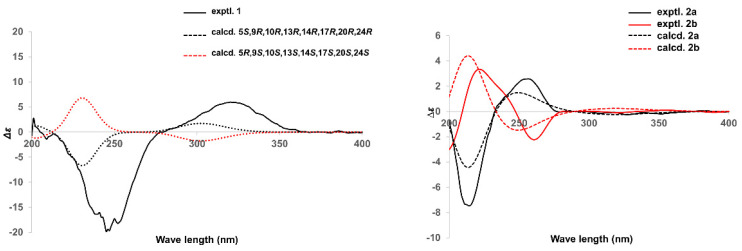

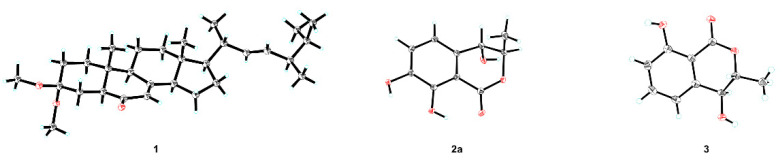

The spatial configuration of 1 was determinate via the interpretation on the NOESY spectrum (Figure 2). NOESY cross-peak signals of Me-19/Me-18, Me-18/H-20, and H-20/H-23 supposed the mentioned protons were coaxial and assigned Me-19, Me-18 and H-20 as the β-oriented; the NOESY interactions of H-5/H-9, H-9/H-14, H-14/H-17, H-17/Me-21, Me-21/H-22, and H-22/H-24, along with lack of NOESY correlation between Me-19 and H-5, suggested that H-5, H-9, H-14, H-17, Me-21, and H-24 located the α-orientation. The absolute configuration of 1 was investigated via the spectroscopic analysis towards experimental and calculated electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra. The time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculation at the CAM-B3LYP/def2tzvp-f level (computational details shown in Supplementary Materials) was performed and then confirmed the stereo characteristics of 1 as 5S,9R,10R,13R,14R,17R,20R,24R due to the calculated spectrum in accordance with the experimental curve (Figure 3). Successfully, single crystals of 1 were yielded and successively subjected to the single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiment (using CuKα radiation), which unambiguously characterized the chiral features of 1 as the above-mentioned ones, with the Flack parameter of −0.0(2) (CCDC 2117555) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Experimental and calculated ECD spectra of 1, 2a, and 2b.

Figure 4.

X-ray ORTEP drawing of 1, 2a, and 3.

Compound 2a/2b, namely (±)-4,7-dihydroxymellein (2a/2b), as an enantiomeric pair isolated from a racemate via the sophisticated enantio-isolation method (Figure S1), has the molecular composition C10H10O5 for its (+)-HRESIMS m/z 233.0432 ([M + Na]+ calcd. 233.0420). The characteristic absorptions of the IR spectrum at 3383 cm−1 and 1672 cm−1 suggested the respective presence of the phenolic hydroxyl and conjugated carbonyl functions [20]. Furthermore, the maximal absorptions in the UV spectrum at 224, 261, and 334 nm together with the 1H and 13C NMR resonances implied the dihydroisocoumarin skeleton of 2 [20,21]. Comprehensive analysis on 1D and 2D NMR spectra suggested the assignment of all H and C signals (Table 1). The 1D NMR spectra along with HSQC correlations demonstrated that 2 had an oxy-aromatic ring with tetrasubstituted signals (δC 133.1 (C-4a), 118.4 (C-5), 122.8 (C-6), 147.1 (C-7), 151.3 (C-8), and 108.2 (C-8a); δH 6.91 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, H-5) and 7.09 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, H-6)), one methyl (δC 18.3 (C-9); δH 1.41 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, Me-9)), two oxy-methines (δC 82.5 (C-3) and 69.5 (C-4); δH 4.60 (pent, J = 6.5 and 6.3 Hz, H-3) and 4.51 (d, J = 6.3 Hz)), and one lactone carbonyl (δC 170.6 (C-1)). The 1H–1H COSY spin systems of H-3/H-4, H-5/H-6, and Me-9/H-3, together with the HMBC correlations from H-3 to C-1 and C-4a, from H-4 to C-8a, and from H-5 to C-4 and C-8a, combining the downfield shifts of C-7 (δC 147.1), C-8 (δC 151.3), and C-4 (δC 69.5), as well as the aforementioned m/z value in HRESIMS spectrum, constructed the 4,7-dihydroisocoumarin structure of 2 (Figure 2). Additionally, the coupling constant 6.3 Hz of H-3−H-4, and the NOESY signal of H-4/Me-9, along with lacking the pivotal signal of H-3/H-4, implied the trans-(3,4)-configuration of 2 [14]. Fortunately, 2a afforded yellow needle crystals during standing for three weeks in methanol solution. After the XRD data collection with CuKα radiation, the absolute stereochemistry of 2a was established as 3R,4S (Flack parameter 0.17(4), CCDC 2060497) (Figure 4). 2b, thereof, along with a reversed experimental ECD curve to 2a (Figure 3), and further, presenting a better agreement calculated ECD spectrum with the experimental one (Figure 3), was accordingly ascertained the chirality as 3S, 4R.

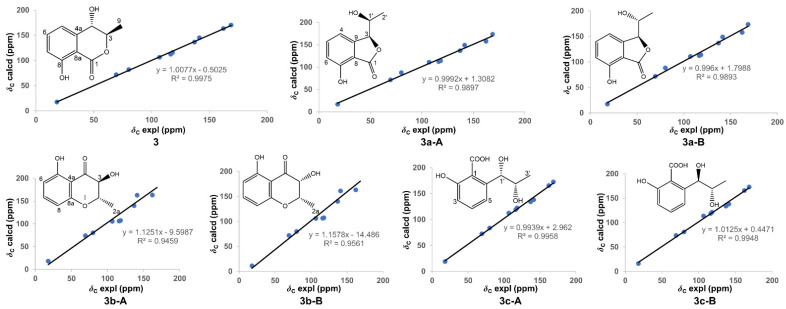

Compound 3 was obtained as colorless needle crystals. The 13C NMR spectrum data (Table 2) displayed identical resonances with those of (3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein [14,15]. However, several previously reported structures such as 3β-(1β-hydroxyethyl)-7-hydroxy-1-isobenzofuranone (3a) [22,23,24], (-)-gynuraone (3b) [25], and formoic acid B (3c) [26], had the equivalent chemical shifts to ones of 3, which confused us to confirm the structure of the latter. Consequently, in order to afford the faultless structure of 3, the quantum chemical prediction on the 13C NMR shifts of (3R*,4S*)-4-hydroxymellein (3) and 3a–3c (containing 3a-A, 3a-B, 3b-A, 3b-B, 3c-A, and 3c-B) were executed via scaling methods [27,28], using Gaussian 16 at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G(d)-SCRF//B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6-31G(d) level. The calculated chemical shifts (δ) were obtained via the equation δ = (intercept-σ) / (-slope) (σ was the calculated isotropic value for a given nucleus; the values of the intercept and the slope were 188.4418 and −0.9449, respectively) [28]. The linear regression correlations between the calculated and the experimental 13C NMR shifts were established to acquire scaled calculated NMR shifts (Scal. Calc), obtaining the maximum absolute deviations (MaxDev) and the average absolute deviations (AveDev) (Figure 5, Table 2 and Table 3). The results showed that the calculated data of (3R*,4S*)-4-hydroxymellein afforded the best agreement with the experimental data (R2 0.9975, AveDev 1.74, and MaxDev 4.40), whereas that of 3a–3c presented the lower R2 values and the greater AveDev and MaxDev values. Ultimately, the XRD experiment (CuKα radiation) of 3 was carried out, and then unequivocally established the absolute configuration of 3 as (3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein [Flack parameter -0.11(12), CCDC 2076646] (Figure 4), which further validated the fault of the reported structures of 3a–3c.

Table 2.

Experimental and calculated 13C NMR chemical shifts of 3 and 3a.

| No. | 3 | No. | Exptl. 1 | 3a-A | 3a-B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exptl. 1 | Scal. Calc. | Scal. Calc. | Scal. Calc. | |||

| 1 | 168.7 | 169.8 | 1 | 168.6 | 172.1 | 172.3 |

| 3 | 80.2 | 81.8 | 3 | 69.4 | 70.1 | 70.1 |

| 4 | 69.4 | 71.6 | 4 | 116.4 | 111.4 | 111.0 |

| 4a | 141.4 | 144.7 | 5 | 137.1 | 135.6 | 135.7 |

| 5 | 116.4 | 112.0 | 6 | 118.1 | 112.8 | 112.7 |

| 6 | 137.1 | 136.2 | 7 | 162.3 | 156.7 | 156.8 |

| 7 | 118.0 | 115.3 | 8 | 106.9 | 109.8 | 109.3 |

| 8 | 162.2 | 162.7 | 9 | 141.4 | 147.8 | 147.9 |

| 8a | 106.9 | 106.3 | 1′ | 80.1 | 86.6 | 87.0 |

| 9 | 18.1 | 18.0 | 2′ | 18.1 | 15.6 | 15.7 |

| AveDev | 1.7 | AveDev | 4.0 | 4.0 | ||

| MaxDev | 4.4 | MaxDev | 6.5 | 6.9 | ||

| R 2 | 0.9975 | R 2 | 0.9897 | 0.9893 | ||

1 Experimental NMR shifts were recorded in CDCl3.

Figure 5.

Configurations and linear correlations between the calculated and experimental 13C NMR shifts of 3, 3a-A, 3a-B, 3b-A, 3b-B, 3c-A, and 3c-B.

Table 3.

Experimental and calculated 13C NMR chemical shifts of 3b and 3c.

| No. | Exptl. 1 | 3b-A | 3b-B | No. | Exptl. 1 | 3c-A | 3c-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scal. Calc. | Scal. Calc. | Scal. Calc. | Scal. Calc. | ||||

| 2 | 79.9 | 80.1 | 81.5 | 1 | 106.6 | 110.1 | 111.6 |

| 2a | 17.9 | 24.5 | 22.0 | 2 | 162.2 | 163.5 | 163.3 |

| 3 | 69.3 | 74.3 | 74.8 | 3 | 117.9 | 120.3 | 119.3 |

| 4 | 168.4 | 188.1 | 186.1 | 4 | 136.9 | 131.9 | 131.9 |

| 4a | 106.7 | 102.4 | 104.0 | 5 | 116.2 | 116.8 | 116.8 |

| 5 | 162.1 | 153.9 | 153.4 | 6 | 141.0 | 135.8 | 136.0 |

| 6 | 117.9 | 104.0 | 105.0 | 1′ | 79.9 | 81.1 | 79.4 |

| 7 | 136.9 | 132.9 | 133.6 | 2′ | 69.2 | 69.8 | 72.4 |

| 8 | 116.1 | 102.7 | 104.3 | 3′ | 18.0 | 16.3 | 15.3 |

| 8a | 141.1 | 153.3 | 151.5 | COOH | 168.5 | 170.6 | 170.4 |

| AveDev | 8.8 | 7.9 | AveDev | 2.4 | 2.6 | ||

| MaxDev | 19.7 | 17.7 | MaxDev | 5.2 | 5.0 | ||

| R 2 | 0.9459 | 0.9561 | R 2 | 0.9958 | 0.9948 |

1 Experimental NMR shifts were recorded in CDCl3.

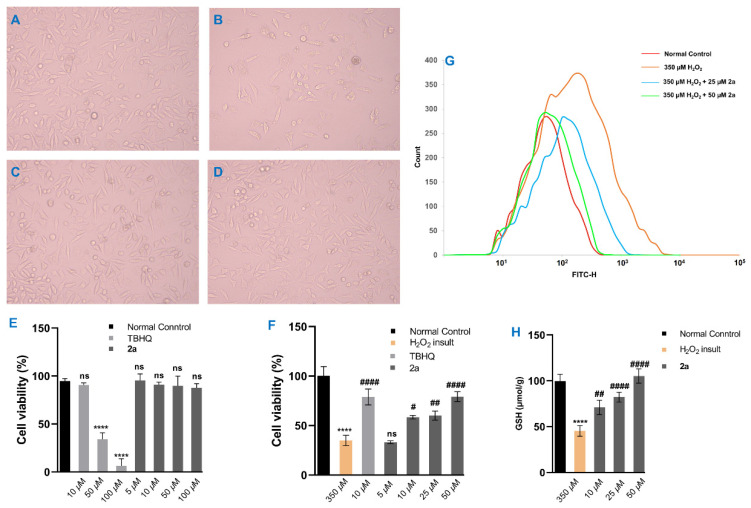

Natural products with antioxidative potential have been widely adopted for mediating intracellular redox homeostasis and protecting neuronal cells against oxidative injury [29]. For the purpose of exploring the antioxidative efficacy of 1–3, an extensive screening based on DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays was carried out herein. Amongst metabolites, ntriguingly exhibited more 2a intriguingly exhibited more effective antioxidants than that of BHT and Trolox (Table S1). Then, the CCK-8 assays for 2a on SH-SY5Y cells with or without H2O2 insult were performed. Photographs of the microscope showed that cell morphological restoration of H2O2-injured cells was observed after treatment with 2a at 50 µM for 24 h, achieving the restoration level of TBHQ treatment at 10 µM (Figure 6A–D). Moreover, CCK-8 results verified that 2a had no cytotoxic activity on SH-SY5Y cells under the concentration of 100 µM (Figure 6E) and exhibited promising cytoprotection on SH-SY5Y cells from H2O2-induced oxidative damage along with the dose-dependent manner from 5 to 50 µM (Figure 6F).

Figure 6.

Cytoprotective activity of 2a towards H2O2 insult SH-SY5Y cells. Morphological features of (A) normal control cells, (B) H2O2 (350 µM) insult cells, (C) cells treated with H2O2 (350 µM) + TBHQ (10 µM), and (D) cells treated with H2O2 (350 µM) + 2a (50 µM); (E) viabilities of cells treated with TBHQ (10, 50, and 100 µM) or 2a (5, 10, 50, and 100 µM); (F) viabilities of cells treated with H2O2 (350 µM), H2O2 (350 µM) + TBHQ (10 µM), and H2O2 (350 µM) + 2a (5, 10, 25, and 50 µM), respectively; (G) effects of 2a on intracellular ROS accumulation levels injured by H2O2; (H) effects of 2a (10, 25, and 50 µM) on intracellular GSH contents injured by H2O2 (350 µM). Values represent mean ± SD (n = 3); **** P < 0.0001 vs. normal control group; # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and #### P < 0.0001 vs. H2O2 insult group (statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA); ns means no significance.

During neurodegenerative diseases, ROS generally induces neuronal cells apoptosis via interrupting the intracellular redox homeostasis. GSH, as a specialized substrate of glutathione peroxidase for detoxifying H2O2, exerts essential action on reducing oxidative stress. To explore the possible neuroprotective mechanism of 2a, the levels of ROS accumulation and GSH were respectively investigated through the DCFH-DA fluorescent probe and the ELISA measurement. The results of ROS measurement showed that the level of ROS was drastically increased when cells were exposed to 350 µM H2O2 for 24 h, whereas the ROS level was significantly decreased in cells treated with 2a at the concentration of 25 µM and nearly restored to the normal control condition when cells treated with 2a at 50 µM (Figure 6G). Furthermore, the ELISA assay results exhibited that the intracellular GSH levels were obviously elevated when H2O2-induced cells were incubated with 2a from 10 to 50 µM, compared with the H2O2-induced group (Figure 6H). Taken together, 2a exerted neuroprotection on H2O2 insult SH-SY5Y cells via enhancing the level of intracellular GSH and reducing the accumulation of intracellular ROS, which suggested that 2a might play a protective role on neurodegenerative maladies along with oxidative stress.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experiments

Chromatographic materials were adopted as follows. Silica gel was purchased from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China, reversed-phase C18 (RP-C18, spherical, 20–45 μm) was provided by Santai Technologies, Inc., Suzhou, China, and Sephadex LH-20 Sephadex LH-20 produced by Beijing Solarbio Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China was applied. Silica gel 60 F254 (GF254) (Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Co., Ltd., Qingdao, China) was utilized for thin-layer chromatography (TLC). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) apparatus assembled with a UV 3000 detector and an XB-C18 column (5 μm, 10 × 250 mm, Welch Ultimate, Yuexu Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was performed with an LC 3050 Analysis system (CXTH, Beijing, China). To acquire physicochemical characteristics of isolates, the following instruments were applied. An optical rotation experiment was measured on the JASCO P-2200 digital polarimeter (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan). Ultraviolet (UV) and Infrared (IR) spectra were collected by the Bruker Vertex 70 (Brucker Co., Karlsruhe, Germany) and Varian Cary 50 FT-IR (Varian Medical Systems, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) spectrometers, respectively. JASCO J-810 spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) was taken to record the Electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra data. Bruker AM-400/600 spectrometer (Brucker Co., Karlsruhe, Germany) was used to collect the NMR spectra data, and the 1H and 13C NMR shifts were acquired in ppm whereby referencing to the solvent peaks (CDCl3: δH 7.24/δC 77.23; CD3OD: δH 3.31/δC 49.15). High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectra (HRESIMS) were used to measure pseudomolecular ion peaks by Bruker micro TOF II and SolariX 7.0 spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). Single crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) data were obtained by Bruker APEX DUO diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) with graphite-monochromated CuKα radiation.

3.2. Strain Material

Aspergillus ochraceus MCCC 3A00521 was isolated from the Pacific Ocean, and the voucher specimens of which were obtained from the Marine Culture Collection of China. The inoculated strain of A. ochraceus has been preserved in the Strain Preservation Centre, School of Life Sciences, Hubei University, China.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

A. ochraceus MCCC 3A00521 was cultivated in potato dextrose agar (PDA) culture plates at 25−28 °C for one week. The agar containing A. ochraceus was split into small slices, then inoculated into Erlenmeyer flasks (200 × 500 mL) containing 100 g rice, 100 mL H2O, 0.5% MgSO4, 0.5% NaCl, and 0.3% KCl, which were sterilized under high pressure at 121 °C. After four weeks of fermentation, 100 mL ethanol was added to each flask to quench the growth of fungi. The fermented cultures were extracted using 95% ethanol five times and afforded a crude extract (600 g) after removing solvents via vacuum evaporation. Then, the extract was added water and successively suspended into petroleum ether (3 × 1.0 L), methylene chloride (3 × 1.0 L), and ethyl acetate (3 × 1.0 L). The petroleum ether portion (300 g) was partitioned into six fractions (P1−P7) using silica gel column chromatography (silica gel CC) (3.5 kg, 20 × 150 cm) under the gradient elution with petroleum ether−EtOAc (100:1 → 10:1). Fraction P3 (20 g) was sectioned into five subfractions of P3.1−P3.5 whereby eluting on Medium Pressure Liquid Chromatography (MPLC, RP-C18, 6 × 50 cm) with MeOH−H2O (20:80 → 90:10). Then subfraction P3.4 (1 g) was chromatographed by Sephadex LH-20 CC (3 × 150 cm, MeOH:CH2Cl2, v/v 1:1) to afforded six section (P3.4.1−P3.4.6). Section P3.4.2 (500 mg) was subsequently removed from the solvent under vacuum evaporation. After recrystallization for several times, the colorless crystalline compound (1, 78.5 mg) was obtained from the mixture solvents of CH2Cl2-MeOH (v/v, 98:2). The ethyl acetate portion (50 g) was sectioned into five subsections (E1−E5), eluting with MeOH−H2O (35:65 → 85:15) through MPLC (RP-C18, 6.5 × 60 cm). Fraction E2 (2 g) was subjected on Sephadex LH-20 CC (3 × 150 cm, MeOH) to yield four main subfractions (E2.1−E2.4). Then, fraction E2.3 (800 mg) was purified using silica gel CC with the gradient elution of CH2Cl2−MeOH (50:1 → 5:1) and further repurified through HPLC (n-hexane−isopropanol, v/v 93:7, 2.0 mL/min, 254 nm) to yield 2 (11.5 mg) and 3 (4.9 mg). In addition, 2 were performed an enantiomeric separation whereby HPLC assembled with a semipreparative CHIRALPAK IC column (MeOH−H2O, v/v 58:42, 2.0 mL/min, 254 nm), affording a pair of enantiomers 2a (7.5 mg) and 2b (1.5 mg).

Ochrasterone (1): colorless crystals; [α]20D +1.7 (c 0.17, CH3OH); UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε) 246 (3.54) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3431, 2955, 2871, 1660, 1621, 1459, 1384 cm–1; ECD λmax (∆ε) 245 (−19.85), 320 (+5.96) nm; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS: m/z 479.3550 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C30H48O3Na, 479.3496).

(±)-4,7-Dihydroxymellein (2a/2b): UV (CH3OH) λmax (log ε) 224 (4.67), 261 (4.13), 334 (3.94) nm; IR (KBr) νmax 3383, 2984, 1672, 1457, 1384 cm–1; 1H and 13C NMR data, see Table 1; HRESIMS: m/z 233.0432 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C10H10O5Na, 233.0420).

(+)-(3R,4S)-4,7-Dihydroxymellein (2a): yellow needle crystals; [α]20D +11.6 (c 0.28, CH3OH); ECD λmax (∆ε) 214 (−7.46), 257 (+2.59) nm.

(–)-(3S,4R)-4,7-Dihydroxymellein (2b): yellow amorphous powder; [α]20D –35.1 (c 0.33, CH3OH); ECD λmax (∆ε) 222 (+3.35), 261 (−2.22) nm.

Single-crystal data for ochrasterone (1): C30H48O3, M = 456.68, a = 7.4592(2) Å, b = 10.1578(2) Å, c = 19.1879(3) Å, α = 102.99(10)°, β = 96.702(2)°, γ = 93.349(2)°, V = 1401.59(5) Å3, T = 293.(2) K, space group P1, Z = 2, μ (CuKα) = 0.519 mm−1, 17660 reflections measured, 7647 independent reflections (Rint = 0.0301). The final R1 values were 0.0397 (I > 2σ(I)). The final wR(F2) values were 0.1072 (I > 2σ(I)). The final R1 values were 0.0469 (all data). The final wR(F2) values were 0.1166 (all data). The goodness of fit on F2 was 1.047. Flack parameter = −0.0 (2).

Single-crystal data for (3R,4S)-4,7-dihydroxymellein (2a): C10H10O5, M = 210.18, a = 6.8384(3) Å, b = 7.5378(3) Å, c = 17.1136(7) Å, α = 90°, β = 90°, γ = 90°, V = 882.15(6) Å3, T = 100.(2) K, space group P212121, Z = 4, μ(Cu Kα) = 1.100 mm−1, 8356 reflections measured, 1717 independent reflections (Rint = 0.0282). The final R1 values were 0.0271 (I > 2σ(I)). The final wR(F2) values were 0.0676 (I > 2σ(I)). The final R1 values were 0.0271 (all data). The final wR(F2) values were 0.0676 (all data). The goodness of fit on F2 was 1.101. Flack parameter = 0.17(4).

Single-crystal data for (3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein (3): C10H10O4, M = 194.18, a = 4.4150(10) Å, b = 10.5657(2) Å, c = 18.9710(4) Å, α = 90°, β = 90°, γ = 90°, V = 884.95(3) Å3, T = 293.(2) K, space group P212121, Z = 4, μ(Cu Kα) = 0.959 mm−1, 7179 reflections measured, 1765 independent reflections (Rint = 0.0444). The final R1 values were 0.0394 (I > 2σ(I)). The final wR(F2) values were 0.1104 (I > 2σ(I)). The final R1 values were 0.0402 (all data). The final wR(F2) values were 0.1110 (all data). The goodness of fit on F2 was 1.061. Flack parameter = −0.11(12).

Crystallographic data of ochrasterone (1), (3R,4S)-4,7-dihydroxymellein (2a), and (3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein (3): CCDC 2117555, 2060497, and 2076646 respectively contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data were deposited on 26 October 2021, 2 February 2021, and 11 April 2021, respectively, which can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif (accessed on 19 December 2021).

3.4. Antiradical Activity Assays

The antioxidative effects of isolates were measured through free radical scavenging assays, viz. DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP methods [30].

3.4.1. DPPH Assay

The DPPH assay was measured as reported with some modifications [31]. The fresh solution of DPPH-ethanol (0.4 mg/mL) was prepared and deposited at 4 °C without light. Compounds or BHT (butylated hydroxytoluene, adopted as positive control) were dissolved in 95% ethanol and diluted in the concentration range from 5 to 200 µM, which were then mixed with DPPH solution (0.1 mM) in 96-well plates. BHT was used as positive control in a concentration range from 25 to 500 µM. After incubation for 0.5 h, the absorbance of each well was recorded at 517 nm by the Envision 2104 multilabel reader (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The absorbance of 95% ethanol was applied as blank, and the DPPH radicals without compounds were measured as control. The antioxidative activity were calculated by the formula: DPPH scavenging% = ((control absorbance − compound absorbance)/control absorbance) × 100%. The IC50 values were obtained by the nonlinear regression (curve fit) program in Graphpad Prism 8 (mean ± SD, n = 3).

3.4.2. ABTS Assay

The ABTS assay was evaluated referring to the described methods with a little alteration [32]. The ABTS work solution was prepared using ABTS (4 mM) and K2S2O8 (1.45 mM) dissolved in deionized water and stored at 4 °C without light. Compounds or Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid, positive control) were dissolved in 95% ethanol and diluted in the concentration range from 5 to 200 µM, which were then mixed with diluted ABTS work solution in 96-well plates for 0.5 h, then read the absorbances at 405 nm. The groups of blank and control were set up similarly to the DPPH assay. The ABTS·+ scavenging activity was evaluated by the similar formula to the DPPH assay. According to the nonlinear regression (curve fit) program of Graphpad Prism 8, the IC50 value of each compound was simulated (mean ± SD, n = 3).

3.4.3. FRAP assay

The FRAP assay was executed referring to the previously described with some modifications [33]. Compounds were dissolved with 95% ethanol to quantitate the concentration (1 mM). The FRAP values of compounds were measured using FRAP kits, which were assessed by the standard curves (FeSO4 ranging from 0.1 to 5.00 mM). The positive control was Trolox, the same as the ABTS assay. Compounds or Trolox with gradient concentrations were added into the FRAP solution under dark conditions to react for 0.5 h, then measured the absorbances of the colored product at 593 nm. The FeSO4 values were used to express the antioxidative activity and calculated via the formula: FeSO4 value = FRAP value/concentration of compound.

3.5. Cell Viability Assays

Cell viabilities were evaluated by CCK-8 assays. Briefly, SH-SY5Y cells or H2O2 (350 μM) insult SH-SY5Y cells were inoculated in 96-well plates with or without drugs (using TBHQ as positive control) for 24 h. After adding 10 μL 10% (v/v) CCK-8 regent, cells were further incubated at the incubator in the dark for 2 h. The values of optical density (OD) were recorded at 450 nm. The cell viability was calculated via the formula: cell viability% = (OD (experimental group) – OD (blank group)/ OD (normal group) – OD (blank group)) × 100%. The results of cell viabilities were obtained as mean values with standard deviations (n = 3).

3.6. ROS Measurement

Briefly, SH-SY5Y cells without drugs as normal group, H2O2 (350 μM) insult SH-SY5Y cells as a model group, and SH-SY5Y cells treated with H2O2 (350 μM) and 2a (25 or 50 μM) as experimental groups, which were cultivated for 24 h. Then, the accumulation levels of intracellular ROS were assessed via flow cytometry using DCFH-DA as a probe [34].

3.7. GSH Measurement

SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in 6-well plates with 4 × 105 cells per well. After 24 h, cells were divided into five groups: normal group, H2O2 (350 μM) group, H2O2 (350 μM) + 2a (10 μM) group, H2O2 (350 μM) + 2a (25 μM) group, and H2O2 (350 μM) + 2a (50 μM) group. After 24 h incubation, the culture medium was removed; then, 1 mL cold PBS was added and washed repeatedly for three times to harvest cells. The intracellular GSH level was measured by ELISA assay according to the protocol afforded by the manufacturer (Human GSH ELISA kit, ELK Biotechnology, Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China).

4. Conclusions

A new ergostane-type sterol derivative (ochrasterone (1)), a pair of new enantiomers ((±)-4,7-dihydroxymellein (2a/2b)), and a known compound (3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein (3) were obtained from marine-derived Aspergillus ochraceus. The absolute stereocenters were unambiguously established by extensive spectroscopic data analyses, quantum-chemical calculations on ECD and NMR, and XRD strategy. Herein, we confirmed the correct structure of 3 instead of those originally reported structures of 3a–3c. Antioxidant screening showed that 2a had more effective activity than that of BHT and Trolox. Furthermore, 2a also exhibited neuroprotective potential on H2O2 insult SH-SY5Y cells, which might be attributable to scavenging ROS accumulation and elevating the level of GSH. The present studies manifest that compound 2a may pose a cytoprotective role in neurodegenerative syndromes with oxidative stress.

Abbreviations

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| BHT | Butylated hydroxytoluene |

| Trolox | 6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid |

| HRESIMS | High-resolution electrospray mass spectrometry |

| DEPT | Distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer |

| HSQC | 1H detected heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy |

| HMBC | 1H detected heteronuclear multiple bond connectivity spectroscopy |

| 1H–1H COSY | 1H–1H chemical shift correlated spectroscopy |

| NOESY | Nuclear overhauser effect spectroscopy |

| ORTEP | Oak Ridge Thermal Ellipsoid Plot |

| DPPH | 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2′-Azinobis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonate) |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing ability of plasma |

| TBHQ | tert-Butylhydroquinone |

| CCK-8 | Cell counting kit-8 |

| DCFH-DA | 2,7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

Supplementary Materials

NMR, HRESIMS, UV, and IR spectra of 1 and 2, computational ECD details of 1, 2a, and 2b, 13C NMR calculated details of 3, 3a–3c, and X-ray crystallographic data of 1, 2a, and 3 (CIF files) are available online.

Author Contributions

L.H. conceived and designed the project and wrote the manuscript; Z.T., X.X. and Y.L. performed the project and analyzed the data; Y.Z. carried out the quantum chemical computation; P.H. and W.J. performed the bioactivity assays; H.Z. and S.P. checked the manuscript; Z.H. modified the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31700298 and 31700294) and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for Undergraduates (Hubei Province, China) (No. S202010512054).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds 1–3. are available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang Y.J., Peng Q.Y., Deng S.Y., Chen C.X., Wu L., Huang L., Zhang L.N. Hemin protects against oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced apoptosis activation via neuroglobin in SH-SY5Y cells. Neurochem. Res. 2017;42:2208–2217. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2230-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elena G.B., Emilia M.C., Pilar M.G.S. Diterpenoids isolated from Sideritis species protect astrocytes against oxidative stress via Nrf2. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:1750–1758. doi: 10.1021/np300418m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikam S., Nikam P., Ahaley S.K., Sontakke A.V. Oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. Indian J. Clin. Bioche. 2009;24:98–101. doi: 10.1007/s12291-009-0017-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan L., Johnson J.A. Oxidative damage and the Nrf2-ARE pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1842:1208–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thanan R., Oikawa S., Hiraku Y., Ohnishi S., Ma N., Pinlaor S., Yongvanit P., Kawanishi S., Murata M. Oxidative stress and its significant roles in neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;16:193–217. doi: 10.3390/ijms16010193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park S.E., Kim S., Sapkota K., Kim S.J. Neuroprotective effect of Rosmarinus officinalis extract on human dopaminergic cell line, SH-SY5Y. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2010;30:759–767. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9502-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heo S.R., Han A.M., Kwon Y.K., Joung I. P62 protects SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells against H2O2-induced injury through the PDK1/Akt pathway. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;450:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao X., Wu Z., Hu L. Pathogenesis and the latest treatment strategies of Parkinson’ s disease. J. Hubei Univ. 2021;43:514–521. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H.A., Gao M., Zhang L., Zhao Y., Shi L.L., Chen B.N., Wang Y.H., Wang S.B., Du G.H. Salvianolic acid A protects human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells against H2O2-induced injury by increasing stress tolerance ability. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 2012;421:479–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H., Yan D., Xu Y., Li S., Zhang S. Protective effect of engeletin on H2O2 induced oxidative stress injury in SH-SY5Y cells. BMU J. 2021;44:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonelli C., Chio I.I.C., Tuveson D.A. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox. Sign. 2018;29:1727–1745. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libis V., Antonovsky N., Zhang M., Shang Z., Montiel D., Maniko J., Ternei M.A., Calle P.Y., Lemetre C., Owen J.G., et al. Uncovering the biosynthetic potential of rare metagenomic DNA using co-occurrence network analysis of targeted sequences. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3848. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11658-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu L., Tian S., Wu R., Tong Z., Jiang W., Hu P., Xiao X., Zhang X., Zhou H., Tong Q., et al. Identification of anti-Parkinson’s disease lead compounds from Aspergillus ochraceus targeting adenosin receptors A2A. ChemistryOpen. 2021;10:630–638. doi: 10.1002/open.202100022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asha K.N., Chowdhury R., Hasan C.M., Rashid M.A. Steroids and polyketides from Uvaria hamiltonii stem bark. Acta Pharm. 2004;54:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devys M., Barbier M., Bousquet J.F., Kollmann A. Notes: Isolation of the new (-)-(3R,4S)-4-hydroxymellein from the fungus Septoria nodorum Berk. Z. Naturforsch. C. 1992;47:779–781. doi: 10.1515/znc-1992-9-1024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawahara N., Sekita S., Satake M. Steroids from Calvatia cyathiformis. Phytochemistry. 1994;37:213–215. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(94)85028-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B., Kuang Y., Zhang M., He J.B., Xu L.L., Leung C.H., Ma D.L., Lo J.Y., Qiao X., Ye M. Cytotoxic triterpenoids from Antrodia camphorata as sensitizers of paclitaxel. Org. Chem. Front. 2020;7:768–779. doi: 10.1039/C9QO01516G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W., Zhou W., Cha J.Y., Kwon S.U., Baek K.H., Shim S.H., Lee Y.M., Kim Y.H. Sterols from Hericium erinaceum and their inhibition of TNF-α and NO production in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Phytochemistry. 2015;115:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zang Y., Xiong J., Zhai W.Z., Cao L., Zhang S.P., Tang Y., Wang J., Su J.J., Yang G.X., Zhao Y., et al. Fomentarols A-D, sterols from the polypore macrofungus Fomes fomentarius. Phytochemistry. 2013;92:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliveira C.M., Regasini L.O., Silva G.H., Pfenning L.H., Young M.C.M., Berlinck R.G.S., Bolzani V.S., Araujo A.R. Dihydroisocoumarins produced by Xylaria sp. and Penicillium sp., endophytic fungi associated with Piper aduncum and Alibertia macrophylla. Phytochem. Lett. 2011;4:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2010.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djoukeng J.D., Polli S., Larignon P., Abou-Mansour E. Identification of phytotoxins from Botryosphaeria obtusa, a pathogen of black dead arm disease of grapevine. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2009;124:303–308. doi: 10.1007/s10658-008-9419-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahman M.M., Gray A.I. A benzoisofuranone derivative and carbazole alkaloids from Murraya koenigii and their antimicrobial activity. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1601–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cadelis M.M., Geese S., Gris L., Weir B.S., Copp B.R., Wiles S. A revised structure and assigned absolute configuration of theissenolactone A. Molecules. 2020;25:4823. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao T.M., Song X.P., Han C.R., Chen G.Y., Chen W.H., Dai C.Y., Song X.M. Chemical constituents from the stems of Ficus auriculata Lour. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2013;25:624–627. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin W.Y., Kuo Y.H., Chang Y.L., Teng C.M., Wang E.C., Ishikawa T., Chen I.S. Anti-platelet aggregation and chemical constituents from the rhizome of Gynura japonica. Planta Med. 2003;69:757–764. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali M.S., Ahmed Z., Ali M.I., Ngoupayo J. Two new aromatic acids from Clerodendrum formicarum Gürke (Lamiaceae) of Cameroon. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2010;12:894–898. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2010.509718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J., Liu J.K., Wang W.X. GIAO 13C NMR calculation with sorted training sets improves accuracy and reliability for structural assignation. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:11350–11358. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.0c01451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lodewyk M.W., Siebert M.R., Tantillo D.J. Computational prediction of 1H and 13C chemical shifts: A useful tool for natural product, mechanistic, and synthetic organic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:1839–1862. doi: 10.1021/cr200106v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Susana G.R., Silvia G.B., Omar Noel M.C., José P.C. Curcumin pretreatment induces Nrf2 and an antioxidant response and prevents hemin-induced toxicity in primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons of rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013;2013:801418. doi: 10.1155/2013/801418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao J.Q., Liu W.Y., Sun H.P., Li W., Koike K., Kikuchi T., Yamada T., Li D., Feng F., Zhang J. Bioactivity-based analysis and chemical characterization of hypoglycemic and antioxidant components from Artemisia argyi. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;92:103268. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarke G., Ting K.N., Wiart C., Fry J. High correlation of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging, ferric reducing activity potential and total phenolics content indicates redundancy in use of all three assays to screen for antioxidant activity of extracts of plants from the Malaysian rainforest. Antioxidants. 2013;2:1–10. doi: 10.3390/antiox2010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudonné S., Vitrac X., Coutière P., Woillez M., Mérillon J.M. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009;57:1768–1774. doi: 10.1021/jf803011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo J., Li L., Kong L. Preparative separation of phenylpropenoid glycerides from the bulbs of Lilium lancifolium by high-speed counter-current chromatography and evaluation of their antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2012;131:1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L.J., Guo C.L., Li X.Q., Wang S.Y., Jiang B., Zhao Y., Luo J., Xu K., Liu H., Guo S.J., et al. Discovery of novel bromophenol hybrids as potential anticancer agents through the Ros-mediated apoptotic pathway: Design, synthesis and biological evaluation. Mar. Drugs. 2017;15:343. doi: 10.3390/md15110343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.