Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether favipiravir reduces the time to viral clearance as documented by negative RT-PCR results for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in mild cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) compared to placebo.

Methods

In this randomized, double-blinded, multicentre, and placebo-controlled trial, adults with PCR-confirmed mild COVID-19 were recruited in an outpatient setting at seven medical facilities across Saudi Arabia. Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either favipiravir 1800 mg by mouth twice daily on day 1 followed by 800 mg twice daily (n = 112) or a matching placebo (n = 119) for a total of 5 to 7 days. The primary outcome was the effect of favipiravir on reducing the time to viral clearance (by PCR test) within 15 days of starting the treatment compared to the placebo group. The trial included the following secondary outcomes: symptom resolution, hospitalization, intensive care unit admissions, adverse events, and 28-day mortality.

Results

Two hundred thirty-one patients were randomized and began the study (median age, 37 years; interquartile range (IQR): 32–44 years; 155 [67%] male), and 112 (48.5%) were assigned to the treatment group and 119 (51.5%) into the placebo group. The data and safety monitoring board recommended stopping enrolment because of futility at the interim analysis. The median time to viral clearance was 10 days (IQR: 6–12 days) in the favipiravir group and 8 days (IQR: 6–12 days) in the placebo group, with a hazard ratio of 0.87 for the favipiravir group (95% CI 0.571–1.326; p = 0.51). The median time to clinical recovery was 7 days (IQR: 4–11 days) in the favipiravir group and 7 days (IQR: 5–10 days) in the placebo group. There was no difference between the two groups in the secondary outcome of hospital admission. There were no drug-related severe adverse events.

Conclusion

In this clinical trial, favipiravir therapy in mild COVID-19 patients did not reduce the time to viral clearance within 15 days of starting the treatment.

Keywords: Clinical trial, Favipiravir, Mild COVID-19, Non-severe SARS-CoV-2

Introduction

As of December 20, 2021, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected more than 275 million people worldwide and caused nearly five million deaths [1]. Since the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, researchers have studied potential effective therapies [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. Favipiravir is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor with activity against influenza virus. It has also shown activity in blocking the replication of other RNA viruses [7,8]. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a positive-sense single-strand RNA virus, making its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase a potential target that favipiravir can block [9]. Favipiravir showed promising results in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 in earlier studies [[10], [11], [12]] and has been listed as a possible treatment in different regimen protocols for mild to moderate COVID-19 by various health regulators and agencies [13,14]. Starting treatment of mild COVID-19 early may prevent progression to a more severe form of the disease [15,16].

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of favipiravir monotherapy in treating mild COVID-19, we conducted a multicentre placebo-controlled randomized trial in Saudi Arabia (Avi-Mild-19).

Methods

Study design

The trial enrolled patients from seven community medical centres and ambulatory care centres in Saudi Arabia. The trial was sponsored by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC). Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board at the Ministry of National Guard—Health Affairs and the Ministry of Health. The trial was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB). The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice.

Randomization and blinding

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to oral favipiravir or placebo. The randomization schedule was generated using the PLAN Procedure (SAS) with a block size of four, stratified by study site. The generated list was embedded in the Research Electronic Data Capture system to ensure allocation concealment. Participants, investigators, and study staff remained unaware of the treatment assignment. The sponsor's investigational drug unit, which is not part of the study team, held the information for treatment allocation.

Patients

The study population was patients aged ≥18 years from community settings who had been diagnosed with mild COVID-19 (confirmed by positive PCR test for SARS-CoV-2); they were enrolled within 5 days of disease onset. Mild COVID-19 was defined as mild illness (with or without respiratory symptoms) with oxygen saturation >94% on room air and management at home with appropriate therapy. Mild illness can include symptoms of uncomplicated upper respiratory tract viral infection, such as fever, fatigue, cough (with or without sputum production), anorexia, malaise, muscle pain, sore throat, dyspnoea, nasal congestion, or headache. Rarely, patients may also present with diarrhoea, nausea, and vomiting.

Key exclusion criteria included hospitalized moderate or severe COVID-19 cases, pregnant or breastfeeding female patients, and those who used favipiravir or participated in other interventional drugs clinical study within 30 days before the first dose of the study treatment. The exclusion criteria also included major comorbidities such as hematologic malignancy, advanced (stage 4–5) chronic kidney disease (including dialysis therapy), severe liver damage (Child-Pugh score C or aspartate aminotransferase >5 times the upper limit), or HIV. Patients with history of gout or hyperuricemia (two times above the upper limit of normal), patients with sensitivity/allergy to favipiravir, and cases with a clinical prognosis of nonsurvival, palliative care, or deep coma were also excluded.

Procedure

Study participants were randomized to receive favipiravir 1800 mg (nine tablets) twice daily as a loading dose on day 1 followed by 800 mg (four tablets) twice daily as a maintenance dose for a total duration of 5 to 7 days of therapy or matching placebo. Follow-up was started on the second day of enrolment by a research coordinator or a study physician via daily phone calls for 14 days or until secondary endpoints were reached. The follow-up also assessed patient compliance, health status, and clinical symptoms. A final follow-up phone call was conducted on day 28 for all patients. Patients were required to visit study sites on days 5 ± 1 day, 10 ± 1 day, and 15 ± 2 days for nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs and blood tests. The swabs were used for detection of SARS-CoV-2 by RT-PCR to document the time of viral clearance (a negative result) or persistence (a positive result).

Efficacy and safety assessment

The primary endpoint of this study was time from start of treatment to viral clearance, defined as conversion of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results from positive to negative within 15 days as described in procedures.

Prespecified secondary endpoints included time from the start of treatment (favipiravir or placebo) to clinical recovery, with normalization of fever and respiratory symptoms and relief of cough (or other relevant symptoms at enrolment) maintained for at least 72 hours; need to use antibiotics within 15 days after starting the medicine; progression of disease in a 28-day period, including hospitalization and intensive care unit admission with or without ventilation requirement; and 28-day mortality. Additional secondary safety endpoints included the occurrence of allergic reactions, medication intolerance, and liver toxicity within 15 days of taking the study drug.

Statistical analysis

A one-sided test of whether the hazard ratio (HR) is 1 with an overall sample size of 576 (288 in the control group and 288 in the treatment group) achieved 90% power at a 0.025 significance level when the HR is 1.330. An interim analysis was planned after recruitment and follow-up of 40% of the total number of participants (i.e. 230). The interim analysis was designed to test for early stopping owing to futility or for efficacy and sample size re-estimation. The decision rules based on the study protocol were (a) to stop the trial for early efficacy if the interim analysis p-value was <0.01, (b) to stop the trial for futility if the interim analysis p-value was ≥0.25, or (c) to declare the trial significant if the sum of the interim analysis and final stage p-values was <0.1832 [12].

The survival analysis method for interval-censored data was used to analyze the primary endpoints owing to the nature of the data collection (i.e. clearance observed at specific follow-up times). Results were reported in terms of HR and 95% CI and one-sided p-value based on the Cox proportional hazards model. A similar analysis was conducted for the secondary outcome of time to symptom resolution in the two treatment groups at 15 days. Analysis of adverse events (AEs) was primarily descriptive, using the proportion of patients who experienced AEs. More detailed analysis methods are included in the statistical analysis plan (see appendix 1 (Statistical Analysis Plan)).

Stopping the trial

DSMB requested an assessment of the conditional power to form a recommendation on continuing the trial upon recruitment and follow-up of more than 40% of the estimated study sample size (231 patients). On September 21, 2021, the DSMB reviewed the interim analysis result and recommended stopping the trial owing to futility based on the calculated p-value.

Results

Participants

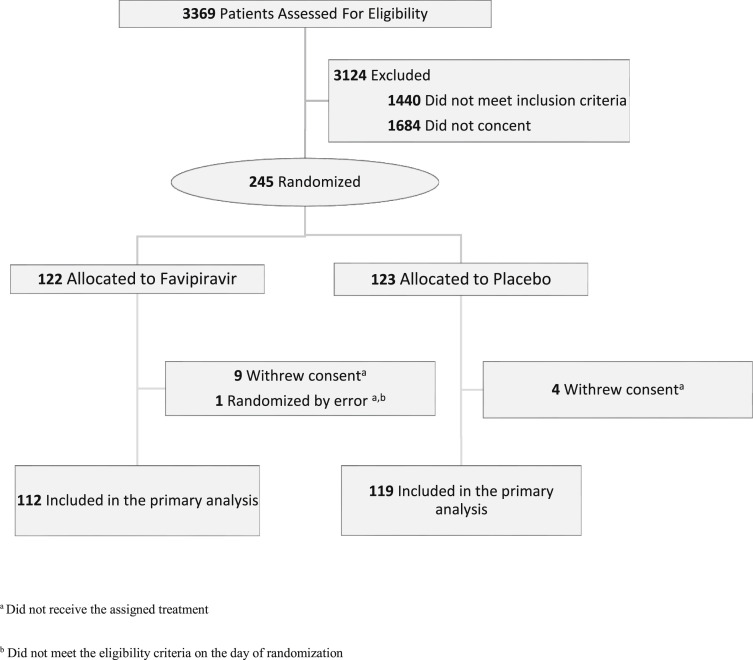

Between July 23, 2020 and August 4, 2021, 245 patients were randomized. Among those, 231 began the study and received the assigned treatment (112 in the favipiravir group and 119 in the placebo group). Of the 14 patients excluded after randomization, one did not meet eligibility criteria, and 13 withdrew consent; none received the study treatment (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Participants had a median age of 37 years (interquartile range (IQR): 32–44 years), and 155 (67%) were male. One patient had cardiovascular disease, 14 (6%) had hypertension, 25 (10.8%) had diabetes, and eight (3.4%) had asthma at the baseline. Approximately 39 (16.8%) were obese (body mass index >30 kg/m2). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between groups (Table 1 ) with a minor insignificant imbalance in body mass index, diabetes, and smoking.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Participants, no. (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Favipiravir (n = 112) | Placebo (n = 119) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 72 (64.2) | 83 (69.7) |

| Female | 40 (35.7) | 36 (30.2) |

| Age, (y) median (IQR) | 37 (31.5–45) | 36 (32–44) |

| BMI, ≥30 kg/m2 | 24 (21.4) | 15 (12.6) |

| Comorbidities and risk factors | ||

| Hypertension | 8 (5) | 6 (7) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 0 | 1 (0.8) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| Asthma | 5 (4.4) | 3 (2.5) |

| Chronic neurological disorder | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| Rheumatologic/autoimmune disorder | 0 | 1 (0.8) |

| Diabetes with complications | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.8) |

| Diabetes without complications | 13 (11.6) | 9 (7.5) |

| Smoking | 4 (3.5) | 8 (6.7) |

| Time from symptoms onset to randomization (d), median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) |

| Laboratory variables | ||

| White blood cell count, median (IQR), × 109/L | 5.19 (4.1–6.3) | 5.14 (4–6.8) |

| Lymphocyte count, median (IQR), × 109/L | 1.9 (1.4–2.4) | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 15 (13.6–15.7) | 15 (14–16.2) |

| Platelet count, median (IQR), × 109/L | 231 (193–277) | 244 (211–289) |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L), median (IQR) | 76 (64–85) | 74 (64–84) |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L), median (IQR) | 8.2 (5.3–11.7) | 8.3 (5.7–11.7) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L), median (IQR) | 24 (20–31) | 25 (20–32.7) |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L), median (IQR) | 28 (20–40.3) | 30.8 (20–51) |

BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

In the favipiravir group, 101 (90%) completed the treatment duration (minimum 5 days total). Discontinuation of treatment before 5 days (in 10% of patients) was due to AEs in two patients, was unexplained in three patients, and was because of hospitalization in six patients. Of 119 patients in the placebo group, 113 (94.9%) completed the assigned treatment duration; discontinuation of placebo before 5 days was due to AEs in two patients, was unexplained in three patients, and was because of hospitalization in one patient. Nonetheless, all patients were evaluated for the outcome on day 28.

Efficacy

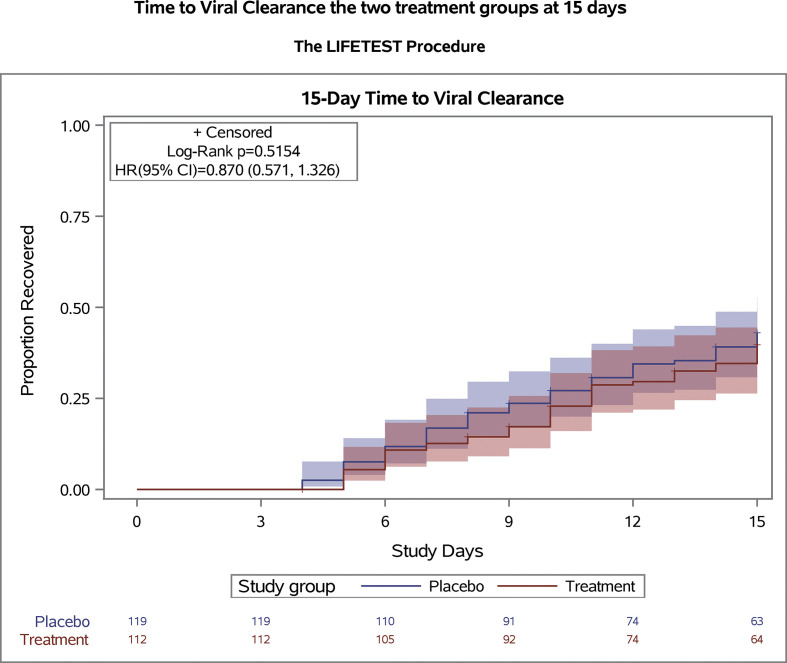

The primary outcome was ascertained in all patients in the modified intention-to-treat population. Viral clearance within 15 days occurred in 42 of 112 (37.5%) in the favipiravir group and 49 of 119 (41.1%) in the placebo group. Time to viral clearance was not significantly different between the two groups (Fig. 2 ), with a median of 10 days (IQR: 6–12 days) in the favipiravir group and 8 days (IQR: 6–12 days) in the placebo group (HR = 0.87; 95% CI 0.571–1.326; p = 0.51).

Fig. 2.

Time to viral clearance in the modified intention-to-treat analysis. The survival curves are survival function (Kaplan-Meier) curves with a p-value calculated by the log-rank test showing time to viral clearance in the modified intention-to-treat population. There was no difference between the treatment and placebo groups in time of SARS-CoV-2 PCR converting from positive to negative. Patients were followed for 15 days after randomization.

The number of patients with COVID-19–related hospital admission was six (5.3%) in the favipiravir group and two (1.6%) in the placebo group (p = 0.16). Furthermore, the median time to clinical recovery was 7 days (IQR: 4–11 days) in the favipiravir group and 7 days (IQR: 5–10 days) in the placebo group (95% CI 0.639–1.250; p = 0.51) (Fig. S1). There was no difference in the resolution of any symptoms or the need to use antibiotics. (see Table 2 )

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes

| Outcome | Favipiravir (N = 112), n (%) | Placebo (N = 119), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| Time to viral clearance (d), median (IQR) | 10 (6–12) | 8 (6–12) |

| Secondary outcome | ||

| Time to clinical recovery (d), median (IQR) | 7 (4–11) | 7 (5–10) |

| Need to use antibiotics | 8 (7.1) | 5 (4.2) |

| Complications | ||

| Emergency department visits | 11 (9.8) | 7 (5.8) |

| Hospitalization | 6 (5.3) | 2 (1.6) |

| ICU admission | 3 (2.6) | 0 |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| 28-day mortality | 0 | 0 |

ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

Safety

AEs were experienced by eight (7.1%) patients in the favipiravir group and seven (5.8%) in the placebo group; however, none were serious according to the protocol definition. AEs leading to discontinuation of the study were only recorded in four patients, two in each group. Discontinuations were mainly due to gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. AEs were more common in the favipiravir group than in the placebo group, including skin rash, respiratory symptoms, and vomiting (Table S2).

Significant elevations in the levels of liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase and alanine transaminase) were noted more often in the favipiravir group; all returned to the normal range by the day-28 follow-up. Three patients in the favipiravir group and one in the placebo group had worsened kidney function, with a drop in creatinine clearance below 60 mL/min. No patient had creatinine clearance <30 mL/min or required haemodialysis in our study.

By day-28 follow-up, emergency department/urgent care visits in the favipiravir group were greater than in the placebo group: 11 (9.8%) and seven (5.8%), respectively (p = 0.36). The eight hospitalizations in both groups were related to disease progression, and none were related to treatment AEs. No other serious AEs were reported, and there were no deaths in either study group.

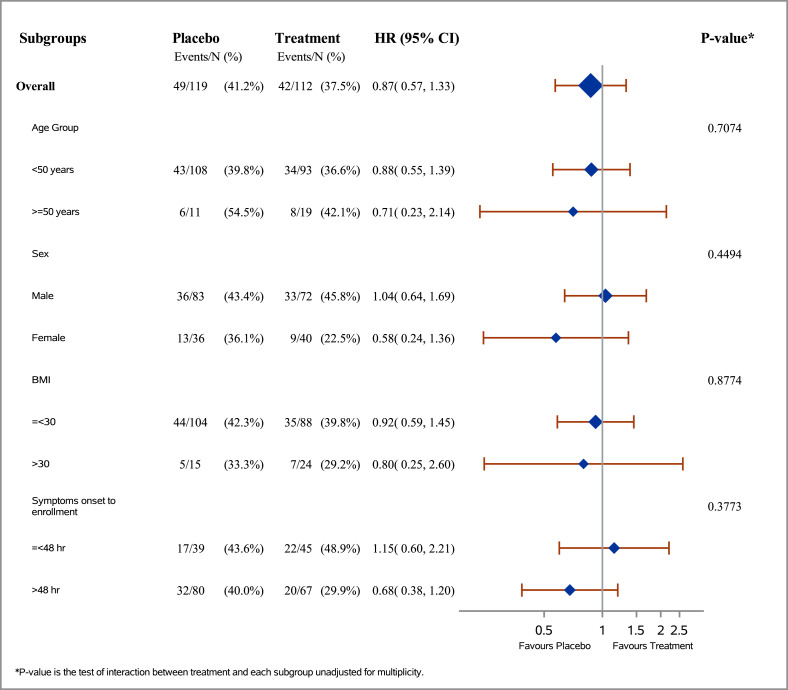

Subgroup and exploratory analyses

The intervention did not affect the primary outcome when age, sex, obesity, and symptoms duration before enrolment were considered as subgroups. In the subgroup of those who used favipiravir within 48 hours of symptom onset, clinical improvement or the time to viral clearance were not significantly different (Fig. 3 ; Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

Time to viral clearance in subgroups.

Discussion

In this double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial, favipiravir was not associated with faster viral clearance or a better clinical outcome when initiated in the first 5 days of the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.

Several antiviral agents with the potential ability to treat SARS-CoV-2 infection have been studied, including remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir-ritonavir, and interferon, in the solidarity trial and other trials and were found ineffective [5,17,18]. Owing to the lack of impact on COVID-19 mortality of the studied agents, evaluation of other potential antivirals such as favipiravir in a prospective setting was needed [19,20]. A randomized study of favipiravir in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 failed to show statistical significance on the primary endpoint of time to RT-PCR negativity. In that trial, a significant improvement in reducing the time to clinical recovery was observed; however, the difference tends to disappear in mild cases, where median time to clinical recovery was 3 versus 4 days in favipiravir and control groups, respectively [11]. Contrary to these findings, a more recent randomized clinical trial noted positive results of favipiravir treatment in moderate COVID-19 [21]. The primary endpoint of this single-blinded trial of 156 patients was a composite of clinical, radiological, and microbiological outcomes. We previously reported the efficacy of combined favipiravir and hydroxychloroquine in treating moderate to severe COVID-19 in a prospective randomized controlled trial. When compared to the standard of care, the combination was found to be ineffective using a seven-category ordinal scale for clinical improvement [22]. The previous trial focused on moderate to severe cases and did not evaluate single favipiravir treatment. The discrepancies in results from favipiravir trials can be due to many factors, such as study design, population, and ethnicity; the inconsistency in defining COVID-19 severity could have also affected the variability of reported results.

Two systematic reviews did not reveal any significant difference between favipiravir and comparators un fatality rate and mechanical ventilation requirement [23,24] but noted that it may promote viral clearance within 7 days and clinical improvement within 14 days of treatment, especially in mild to moderate COVID-19 [24]. Data on the early initiation of antiviral therapy, which could lead to a rapid and significant improvement in viral infections, support our current trial [25,26].

Our data are consistent with previous studies on the absence of favipiravir's effectiveness in all examined endpoints (viral clearance, time to clinical improvement, and hospital admission), supporting the lack of effectiveness in this population. Taken together, it could be extrapolated that there is no effect of favipiravir on COVID-19, regardless of disease severity.

In terms of safety, AEs reported in our trial were similar to those in previous reports [[27], [28], [29]]. Unlike our study, some trials reported chest pain and an increase in triglyceride levels as AEs after favipiravir treatment [27,28,30]. Other trials also reported hyperuricemia as a non-serious adverse drug reaction secondary to favipiravir [29,30], but uric acid was not part of our follow-up laboratory testing because we excluded all patients with gout based on the study protocol. However, although no serious AEs were observed in either group, the daily pill burden was a major challenge. The recommended daily doses to achieve acceptable plasma concentrations are 3600 mg (18 tablets) on the first day and 1600 mg (8 tablets) on the following days. Such a number of pills with unproven benefits can be undesirable owing to difficulties in administration and possible AEs.

The study has also encountered some limitations due to the sample size, noncompliance, missing data, and withdrawal after randomization. Nevertheless, the study showed an almost certain result of non-efficacy of the investigational drug. Viral clearance as a primary endpoint was used commonly in viral clinical trials, including prior influenza clinical trials. Because more than 80% of COVID-19 cases would not progress to severe illness or require hospitalization, clinical improvement might not reflect the efficacy of the antiviral when symptom resolution occurs without therapy and can be very subjective. The study team favoured a more objective outcome of viral clearance. Furthermore, reducing viral clearance could strongly affect disease transmission, a critical infection control measure. The study is still considered underpowered for the secondary clinical endpoints, but it can help in designing future clinical trials and generate valuable systematic reviews and meta-analyses. To our knowledge, this is the largest double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of favipiravir monotherapy in treating patients with mild COVID-19. In addition, our trial adds to the growing body of evidence on the clinical and microbiological benefits of repurposing antiviral therapy, particularly favipiravir, for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In conclusion, this randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial found no clinical or virological benefit in treating mild COVID-19 patients with favipiravir. The trial result may influence decisions to remove favipiravir from national protocols for COVID-19 treatment.

Transparency declaration

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Saudi Arabia (protocol no. RC20/220/R). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author contributions

MBo, AAlh, EM, and MAb developed the study concept and design. SAlr, MBa, ZG, HAlt, KAlh, SAls, and AT participated in enrolment and data collection. AAlh, MBo, and OA participated in the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data. HAlq, SA, AAlh, OA, EM, and NA critically reviewed the manuscript. OA performed the statistical analysis. MBo obtained the funding. AM, MAla, RJ, KS, NA, KAA, SJ, AAls, FA, MAls, MAJ, and SAlj contributed in administrative, technical, and material support. AAla, KAla, AAls, and MBo participated in supervision. All authors critically revised the report and approved the final version to be submitted for publication. The corresponding author confirms that he had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the site's team members for their great effort and help enrolling participants (names are provided in Appendix S1) and all the healthcare workers who took care of the patients during this trial. We thank Dr. Saleh Altamimi, CEO of First Riyadh Health Cluster in Saudi Arabia, and all other health care leaders in the Ministry of Health for supporting this trial. We also thank the DSMB members for their input and critical review of the data.

Editor: L. Scudeller

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.12.026.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.COVID-19 Map - Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center [Internet] 2020. Johns Hopkins coronavirus resource center.https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html [cited 20 December 2021]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [Internet] 2020. WHO.https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [cited 7 November 2021]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timeline . 2021. WHO's COVID-19 response [Internet]. WHO.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline [cited 7 November 2021]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao X., Ye F., Zhang M., Cui C., Huang B., Niu P., et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:732–739. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan H., Peto R., Karim Q., Alejandria M., Henao-Restrepo A., García C., et al. Repurposed antiviral drugs for COVID-19 –interim WHO SOLIDARITY trial results. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:497–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2023184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delang L., Abdelnabi R., Neyts J. Favipiravir as a potential countermeasure against neglected and emerging RNA viruses. Antiviral Res. 2018;153:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furuta Y., Komeno T., Nakamura T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B. 2017;93:449–463. doi: 10.2183/pjab.93.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buonaguro L., Tagliamonte M., Tornesello M., Buonaguro F. SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase as target for antiviral therapy. J Transl Med. 2020;18:185. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alamer A., Alrashed A., Alfaifi M., Alosaimi B., AlHassar F., Almutairi M., et al. Effectiveness and safety of favipiravir compared to supportive care in moderately to critically ill COVID-19 patients: a retrospective study with propensity score matching sensitivity analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37:1085–1097. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1920900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Udwadia Z., Singh P., Barkate H., Patil S., Rangwala S., Pendse A., et al. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir, an oral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, in mild-to-moderate COVID-19: a randomized, comparative, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;103:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassanipour S., Arab-Zozani M., Amani B., Heidarzad F., Fathalipour M., Martinez-de-Hoyo R. The efficacy and safety of Favipiravir in treatment of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Sci Rep. 2021;1:11022. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90551-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamakawa K., Yamamoto R., Ishimaru G., Hashimoto H., Terayama T., Hara Y., et al. Japanese Rapid/Living recommendations on drug management for COVID-19. Acute Med Surg. 2021;8:e664. doi: 10.1002/ams2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Pages/Default.aspx [Internet]. [cited 7 November 2021]. Available from:

- 15.Wu Z., McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. JAMA. 2020;323:1239. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forrest J.I., Rayner C.R., Park J.J.H., Mills E.J. Early treatment of COVID-19 disease: a missed opportunity. Infect Dis Ther. 2020;9:715–720. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reis G., Moreira Silva EA dos S., Medeiros Silva D.C., Thabane L., Singh G., Park J.J.H., et al. Effect of early treatment with hydroxychloroquine or lopinavir and ritonavir on risk of hospitalization among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong Y., Shamsuddin A., Campbell H., Theodoratou E. Current COVID-19 treatments: rapid review of the literature. J Glob Health. 2021;11:10003. doi: 10.7189/jogh.11.10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiraki K., Daikoku T. Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections. Pharmacol Ther. 2020;209:107512. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baranovich T., Wong S.-S., Armstrong J., Marjuki H., Webby R.J., Webster R.G., et al. T-705 (favipiravir) induces lethal mutagenesis in influenza A H1N1 viruses in vitro. J Virol. 2013;87:3741–3751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02346-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shinkai M., Tsushima K., Tanaka S., Hagiwara E., Tarumoto N., Kawada I., et al. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir in moderate COVID-19 pneumonia patients without oxygen therapy: a randomized, phase III clinical trial. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10:2489–2509. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00517-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosaeed M., Mahmoud E., Hussein M., Alharbi A., Alsaedy A., Alothman A., et al. A trial of favipiravir and hydroxychloroquine combination in adults hospitalized with moderate and severe Covid-19: a structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21:904. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04825-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Özlüşen B., Kozan Ş., Akcan R.E., Kalender M., Yaprak D., Peltek İ.B., et al. Effectiveness of favipiravir in COVID-19: a live systematic review. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40:2573–2583. doi: 10.1007/s10096-021-04307-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manabe T., Kambayashi D., Akatsu H., Kudo K. Favipiravir for the treatment of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:489. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06164-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oboho I., Reed C., Leon M., Rothrock G., Aragon D., Meek J., et al. 1341 The benefit of early influenza antiviral treatment of pregnant women hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:S58. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A. Early versus late oseltamivir treatment in severely ill patients with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1): speed is life. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:959–963. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivashchenko A.A., Dmitriev K.A., Vostokova N.V., Azarova V.N., Blinow A.A., Egorova A.N., et al. AVIFAVIR for treatment of patients with moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): interim results of a phase II/III multicenter randomized clinical trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:531–534. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai Q., Yang M., Liu D., Chen J., Shu D., Xia J., et al. Experimental treatment with favipiravir for COVID-19: an open-label control study. Engineering (Beijing) 2020;6:1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C., Zhang Y., Huang J., Yin P., Cheng Z., Wu J., et al. Favipiravir versus arbidol for clinical recovery rate in moderate and severe adult COVID-19 patients: a prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled clinical trial. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:683296. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.683296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doi Y., Hibino M., Hase R., Yamamoto M., Kasamatsu Y., Hirose M., et al. A prospective, randomized, open-label trial of early versus late favipiravir therapy in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01897-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.