Abstract

Background

The COVID 19 pandemic has had a crucial effect on the patterns of disease and treatment in the healthcare system. This study examines the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on respiratory ED visits and admissions broken down by age group and respiratory diagnostic category.

Methods

Data on non-COVID related ED visits and hospitalizations from the ED were obtained in a retrospective analysis for 29 acute care hospitals, covering 98% of ED beds in Israel, and analyzed by 5 age groups: under one-year-old, 1–17, 18–44, 45–74 and 75 and over. Diagnoses were classified into three categories: Upper respiratory tract infections (URTI), pneumonia, and COPD or asthma. Data were collected for the whole of 2020, and compared for each month to the average number of cases in the three pre-COVID years (2017–2019).

Results

In 2020 compared to 2017–2019, there was a decrease of 34% in non-COVID ED visits due to URTI, 40% for pneumonia and a 35% decrease for COPD and asthma. Reductions occurred in most age groups, but were most marked among infants under a year, during and following lockdowns, with an 80% reduction. Patients over 75 years old displayed a marked drop in URTI visits. Pediatric asthma visits fell during lockdowns, but spiked when restrictions were lifted, accompanied by a higher proportion admitted. The percent of admissions from the ED visits remained mostly stable for pneumonia; the percent of young adults admitted with URTI decreased significantly from March to October.

Conclusions

Changing patterns of ED use were probably due to a combination of a reduced rate of viral diseases, availability of additional virtual services, and avoidance of exposure to the ED environment. Improved hygiene measures during peaks of respiratory infections could be implemented in future to reduce respiratory morbidity; and continued provision of remote health services may reduce overuse of ED services for mild cases.

Keywords: COVID-19, Respiratory disorders, Emergency department (ED) visits, Admissions, URTI, Asthma, Pneumonia

1. Introduction

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, reductions in seasonal flu and other respiratory viruses have been noted in different parts of the world, potentially due to social distancing, use of masks and improved hygiene, as well as school closures and restricted travel. [[1], [2], [3], [4]] A systematic review including multiple countries concluded that the introduction of non-pharmaceutical interventions, aimed to reduce COVID transmission, also resulted in reduced flu burden. [5] Reductions in overall ED visits have also been reported following the pandemic and the public health measures in place, in Japan [6] and in the US. [7] Such reduction was also documented in pediatric ED visits. [8]

Respiratory infections are transmitted in a similar way to COVID, so visits and admissions related to non-COVID respiratory infections are likely to be affected by public health measures.

Since different age groups were differentially affected by COVID burden, and by public health measures (e.g. workplace or school closures), it is prudent to investigate whether there was also a differential effect on acute respiratory illnesses requiring urgent care.

In Israel, the first COVID-19 case was confirmed at the end of February 2020. The first wave of disease was observed in mid-March and April 2020, with up to 550 new confirmed COVID-19 cases per day. With rising numbers of new cases, a national lockdown was imposed in April. In May and June, the number of new cases decreased dramatically, and restrictions were gradually removed. In July 2020, the number of new infections started to rise, creating a second disease wave and reaching a peak of 9000 new cases per day in late September to early October, when a second national lockdown was implemented. Based on the overall population of 9.135 million citizens on 31/12/2019, [9] the figures of the first and second waves represent a rate of 6.0 and 76.6 daily cases per 100,000 population in the first and second waves, respectively.

Public health measures, including the enforcement of mask wearing, social distancing, and closing schools differentially by grade were the main strategy to tackle the spread of infection throughout these months, until the national vaccination effort began in late December 2020. Patients were encouraged to forgo physical appointments and choose telemedicine (telephone or video appointments) where possible.

Study question: The aim of this study was to compare the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on non-COVID respiratory visits to the ED and the percent of ED patients admitted in different age groups and by types of respiratory diagnostic category.

2. Methods

We extracted data on ED visits and hospitalizations from the ED from the National Emergency Department Visits Database (NEDVD) maintained in the Health Information Division in the Ministry of Health (MOH), and conducted a retrospective analysis. The NEDVD includes all visits to ED in 29 acute care hospitals in Israel (covering 98% of ED beds). The database includes demographic characteristics, time of admission and discharge, destination following discharge and diagnosis according to ICD-9-CM.

Data on ED visits and admissions were analyzed in 5 age groups: under one year old, 1–17, 18–44, 45–74 and 75 and over. Data were collected for 2020 by month, and compared for each month to the number of cases in the corresponding month averaged from 2017 to 2019, in order to overcome potential confounders arising from fluctuations in cases from one year to the next. All patients with diagnosis of COVID-19 were excluded from the study. We chose three categories of acute respiratory diagnoses: Upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) (460–466, 786.01, 786.02 ICD-9-CM codes), pneumonia (480–486 ICD-9-CM codes), and COPD or asthma (491–496, 786.07 ICD-9-CM codes). The number of influenza visits was extremely small and therefore was not included in the analysis. Other respiratory diseases not included in this study were other chronic diseases of the lung and pleura and external harm to the respiratory tract such as pneumothorax and aspirations.

Hospital admissions from ED are reported as the percent of admissions of ED visits for each of the three respiratory diagnostic types. The percent of admissions was compared to that of the percent from average 2017–2019.

We analyzed the data with SAS version 9.4. P values were calculated according to the method recommended by Silcocks. [10]

3. Results

3.1. ED visits

During 2020 there were 108,012 ED visits with respiratory related diagnoses compared to 152,526, which was the average number of visits per year in 2017–2019 (Table 1 ). Of these, there was a decrease of 32% in the total amount of visits to the ED due to URTI, a decrease of 33% of visits for pneumonia and a 32% decrease for COPD and Asthma. These three groups comprised 85% of all non-Covid19 respiratory related visits.

Table 1.

ED visits and admission rates by disease category, year and relative change, 2020/average 2017–2019

| ED visits (N, % change) |

% of ED visits admitted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Average 2017–2019 | % change 2020/average 2017–2019 | 2020 | Average 2017–2019 | |

| URTI | 47,220 | 69,323 | −32% | 18% | 21% |

| Pneumonia | 26,662 | 39,749 | −33% | 67% | 63% |

| COPD & asthma | 17,510 | 25,428 | −32% | 51% | 52% |

| All respiratory | 108,012 | 152,526 | −29% | 45% | 44% |

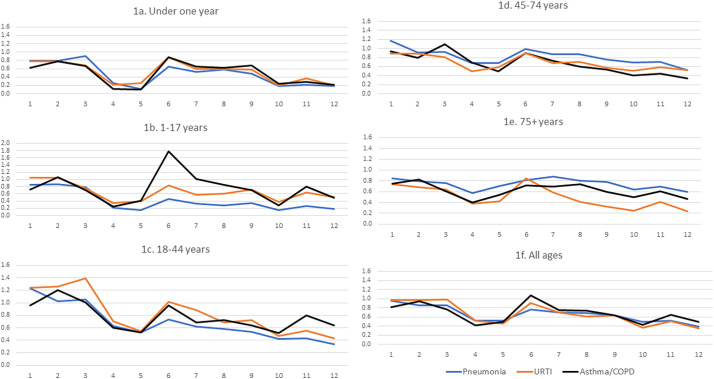

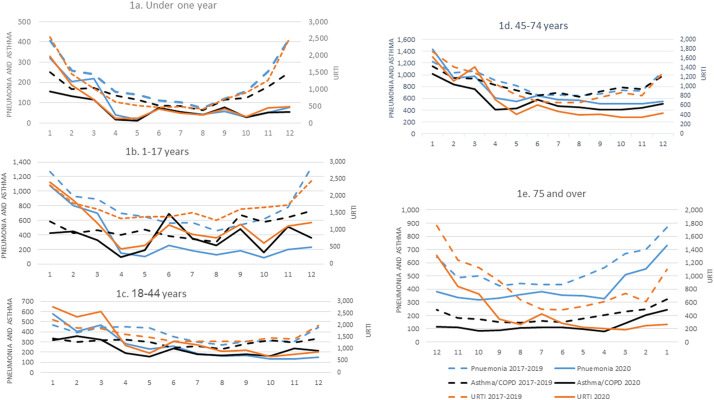

Reductions were seen in most age groups (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ). Fig. 1 presents the ratio of ED visits between 2020 vs the average of 2017–2019 per month; Fig. 2 presents raw number of visits per month. Among infants under a year, this reduction was most marked during and shortly after both lockdowns (April–May and October–December 2020) with an 80% reduction in visits compared to corresponding months in 2017–2019. This reduction was around 40% in July–September when restrictions were relaxed. For infants a reduction occurred in all types of respiratory complaints throughout the year. During the first wave, the reduction was more prominent for asthma and wheezing compared with URTI, and pneumonia (89%, 76% and 72%, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Ratio of ED visits by disease category and month, 2020/average 2017–2019.

Fig. 2.

Number of ED visits by disease category in 2020 and average of 2017–2019.

Among children aged 1–17, the pattern was slightly different. While ED visits were reduced compared to the previous years for all respiratory diseases, asthma behaved differently. Asthma visits dropped during April and May, but peaked in June to a rate almost twice as high as the previous years, subsequently dropping again to the same level as in previous years.

In young adults, aged 18–44, from April till the end of 2020 respiratory ED visits were lower than in previous years for all causes. The 45–74 age group showed a reduction in all causes with a greater reduction in URTI. From mid to end of 2020, pneumonia showed less reduction in the number of ED visits, compared with the other diagnostic categories.

Reductions for persons aged 75 and over were less marked than in younger age groups. The greatest decrease was seen for URTI, reaching a 75% drop in October and December. Visits for pneumonia decreased overall by only 25%.

In most months and in most age groups in all three disease categories, the decrease in number of ED visits in 2020 was statistically significant compared to the average of 2017–2019 (p < 0.05) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Number of ED visits by disease category in 2020 vs average of 2017–2019.

| Age | Month | N-average 2017–2019 |

N-2020 |

p value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia 2017–2019 | URTI 2017–2019 | Asthma/COPD 2017–2019 | Pneumonia 2020 | URTI 2020 | Asthma/COPD 2020 | Pneumonia | URTI | Asthma/COPD | ||

| <1 year | 1 | 404 | 2547 | 251 | 320 | 1968 | 156 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 258 | 1460 | 167 | 204 | 1128 | 131 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.041 | |

| 3 | 241 | 1014 | 172 | 218 | 688 | 115 | 0.297 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| 4 | 154 | 622 | 137 | 40 | 129 | 16 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | 140 | 512 | 114 | 16 | 132 | 12 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 6 | 109 | 466 | 86 | 71 | 407 | 75 | 0.005 | 0.048 | 0.431 | |

| 7 | 103 | 490 | 84 | 54 | 293 | 54 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.014 | |

| 8 | 74 | 409 | 63 | 43 | 244 | 39 | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.021 | |

| 9 | 120 | 714 | 114 | 57 | 412 | 77 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 | |

| 10 | 156 | 897 | 123 | 29 | 183 | 29 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 11 | 254 | 1264 | 180 | 52 | 455 | 51 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 12 | 421 | 2512 | 251 | 78 | 489 | 53 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 1–17 years | 1 | 1271 | 2314 | 589 | 1075 | 2411 | 424 | 0.000 | 0.163 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 931 | 1785 | 423 | 805 | 1877 | 450 | 0.003 | 0.133 | 0.379 | |

| 3 | 893 | 1618 | 461 | 699 | 1206 | 326 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 4 | 693 | 1334 | 396 | 148 | 449 | 95 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | 649 | 1387 | 472 | 99 | 549 | 194 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 6 | 562 | 1384 | 385 | 259 | 1158 | 690 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 7 | 571 | 1504 | 344 | 185 | 873 | 351 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.810 | |

| 8 | 459 | 1283 | 304 | 129 | 776 | 258 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.056 | |

| 9 | 533 | 1613 | 672 | 180 | 1159 | 479 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 10 | 613 | 1664 | 577 | 89 | 617 | 158 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 11 | 780 | 1735 | 639 | 202 | 1116 | 512 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 12 | 1324 | 2437 | 728 | 235 | 1223 | 360 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 18–44 years | 1 | 468 | 2229 | 333 | 575 | 2759 | 320 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.648 |

| 2 | 394 | 1880 | 300 | 402 | 2360 | 361 | 0.804 | 0.000 | 0.020 | |

| 3 | 442 | 1852 | 320 | 465 | 2582 | 323 | 0.472 | 0.000 | 0.948 | |

| 4 | 449 | 1622 | 321 | 281 | 1139 | 191 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | 441 | 1486 | 299 | 229 | 809 | 157 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 6 | 355 | 1306 | 244 | 259 | 1323 | 235 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.704 | |

| 7 | 301 | 1315 | 260 | 187 | 1160 | 178 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 | |

| 8 | 275 | 1306 | 233 | 160 | 895 | 167 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| 9 | 309 | 1302 | 284 | 166 | 940 | 181 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 10 | 314 | 1455 | 316 | 133 | 677 | 162 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 11 | 304 | 1411 | 297 | 131 | 774 | 236 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.009 | |

| 12 | 444 | 1980 | 338 | 151 | 857 | 216 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 45–74 years | 1 | 1221 | 1735 | 1140 | 1427 | 1633 | 1016 | 0.000 | 0.083 | 0.008 |

| 2 | 1036 | 1417 | 943 | 942 | 1123 | 837 | 0.036 | 0.000 | 0.013 | |

| 3 | 1061 | 1292 | 933 | 975 | 1415 | 755 | 0.061 | 0.019 | 0.000 | |

| 4 | 905 | 1055 | 826 | 612 | 725 | 408 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | 815 | 824 | 735 | 549 | 408 | 430 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 6 | 656 | 684 | 650 | 646 | 612 | 581 | 0.803 | 0.049 | 0.053 | |

| 7 | 659 | 660 | 695 | 577 | 477 | 467 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 8 | 650 | 667 | 631 | 565 | 396 | 447 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 9 | 674 | 770 | 715 | 512 | 408 | 405 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 10 | 738 | 872 | 790 | 511 | 349 | 405 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 11 | 727 | 807 | 755 | 513 | 353 | 438 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 12 | 1057 | 1289 | 988 | 544 | 437 | 510 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 75+ years | 1 | 1735 | 884 | 645 | 1462 | 656 | 486 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 1403 | 620 | 495 | 1107 | 423 | 408 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.004 | |

| 3 | 1338 | 565 | 464 | 1019 | 362 | 280 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 4 | 1129 | 461 | 412 | 652 | 174 | 164 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | 991 | 319 | 352 | 700 | 135 | 192 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 6 | 866 | 250 | 302 | 709 | 212 | 218 | 0.000 | 0.085 | 0.000 | |

| 7 | 867 | 245 | 318 | 760 | 143 | 222 | 0.008 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 8 | 889 | 271 | 292 | 716 | 111 | 215 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| 9 | 853 | 304 | 299 | 666 | 100 | 178 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 10 | 1000 | 370 | 342 | 640 | 91 | 170 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 11 | 976 | 307 | 361 | 673 | 126 | 219 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 12 | 1284 | 551 | 488 | 759 | 133 | 227 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

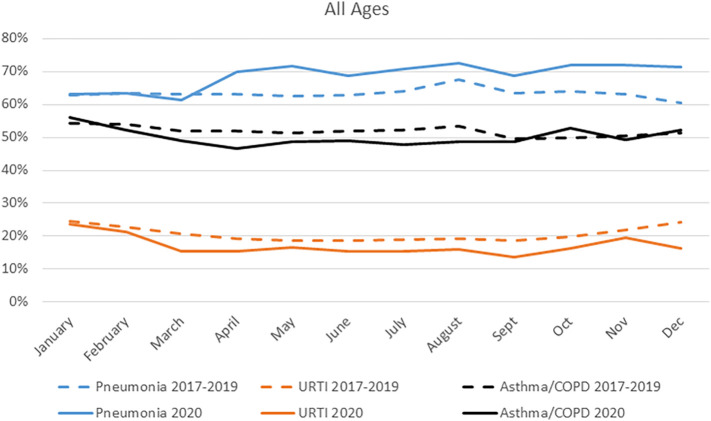

3.2. Hospital admissions

The percent of admissions from ED to hospital wards was significantly higher for pneumonia (p < 0.05) for the total study population from April till the end of 2020 compared to previous years. The decrease in percent of admission for URTI was significant from February till December. The decrease of percent of admission for Asthma or COPD was statistically significant only in March–April and June–August (Fig. 3 , Table 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Percent of ED visits admitted, by disease category and month, 2020 and average 2017–2019.

Table 3.

Percent of ED patients admitted by disease category in 2020 vs average of 2017–2019.

| Age | Month | Pneumonia 2017–2019 | Pneumonia 2020 | P value | URTI 2017–2019 | URTI 2020 | P value | Asthma/COPD 2017–2019 | Asthma/COPD 2020 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 1 | 42% | 45% | 0.375 | 39% | 39% | 0.641 | 33% | 30% | 0.512 |

| 2 | 43% | 41% | 0.633 | 38% | 39% | 0.655 | 32% | 39% | 0.145 | |

| 3 | 41% | 44% | 0.434 | 31% | 33% | 0.525 | 33% | 44% | 0.030 | |

| 4 | 38% | 43% | 0.612 | 24% | 26% | 0.595 | 34% | 19% | 0.283 | |

| 5 | 36% | 50% | 0.296 | 20% | 25% | 0.141 | 33% | 25% | 0.758 | |

| 6 | 36% | 37% | 0.892 | 17% | 23% | 0.017 | 33% | 48% | 0.029 | |

| 7 | 38% | 30% | 0.286 | 20% | 14% | 0.033 | 35% | 44% | 0.212 | |

| 8 | 39% | 30% | 0.307 | 21% | 17% | 0.255 | 40% | 38% | 1.000 | |

| 9 | 33% | 25% | 0.223 | 21% | 19% | 0.392 | 33% | 44% | 0.085 | |

| 10 | 34% | 38% | 0.687 | 26% | 21% | 0.163 | 35% | 45% | 0.320 | |

| 11 | 41% | 42% | 0.885 | 34% | 26% | 0.001 | 37% | 47% | 0.173 | |

| 12 | 41% | 35% | 0.288 | 38% | 23% | 0.000 | 32% | 53% | 0.004 | |

| 1–17 years | 1 | 32% | 31% | 0.482 | 14% | 15% | 0.329 | 31% | 38% | 0.009 |

| 2 | 34% | 35% | 0.768 | 13% | 14% | 0.458 | 33% | 35% | 0.561 | |

| 3 | 35% | 33% | 0.371 | 14% | 13% | 0.369 | 31% | 35% | 0.262 | |

| 4 | 34% | 29% | 0.280 | 13% | 11% | 0.450 | 33% | 21% | 0.022 | |

| 5 | 35% | 33% | 0.914 | 14% | 16% | 0.267 | 34% | 35% | 0.872 | |

| 6 | 33% | 34% | 0.777 | 13% | 13% | 0.961 | 34% | 38% | 0.088 | |

| 7 | 32% | 37% | 0.160 | 13% | 11% | 0.135 | 31% | 33% | 0.351 | |

| 8 | 33% | 35% | 0.625 | 14% | 13% | 0.494 | 34% | 34% | 0.766 | |

| 9 | 32% | 26% | 0.149 | 13% | 11% | 0.070 | 36% | 40% | 0.102 | |

| 10 | 34% | 36% | 0.731 | 13% | 15% | 0.383 | 33% | 25% | 0.062 | |

| 11 | 34% | 37% | 0.489 | 13% | 16% | 0.005 | 34% | 41% | 0.007 | |

| 12 | 33% | 36% | 0.354 | 14% | 13% | 0.399 | 32% | 36% | 0.202 | |

| 18–44 years | 1 | 47% | 45% | 0.298 | 14% | 14% | 0.360 | 33% | 36% | 0.417 |

| 2 | 42% | 39% | 0.319 | 14% | 14% | 0.525 | 30% | 29% | 0.540 | |

| 3 | 43% | 40% | 0.230 | 15% | 8% | 0.000 | 27% | 20% | 0.015 | |

| 4 | 43% | 39% | 0.259 | 15% | 9% | 0.000 | 28% | 24% | 0.184 | |

| 5 | 40% | 35% | 0.164 | 17% | 11% | 0.000 | 30% | 24% | 0.182 | |

| 6 | 41% | 44% | 0.362 | 18% | 9% | 0.000 | 30% | 29% | 1.000 | |

| 7 | 43% | 36% | 0.087 | 18% | 12% | 0.000 | 29% | 26% | 0.521 | |

| 8 | 44% | 46% | 0.602 | 16% | 11% | 0.000 | 30% | 19% | 0.003 | |

| 9 | 44% | 44% | 1.000 | 16% | 9% | 0.000 | 28% | 28% | 0.928 | |

| 10 | 44% | 50% | 0.162 | 16% | 12% | 0.007 | 27% | 28% | 0.924 | |

| 11 | 46% | 42% | 0.453 | 16% | 14% | 0.150 | 30% | 27% | 0.337 | |

| 12 | 44% | 48% | 0.438 | 16% | 12% | 0.002 | 31% | 28% | 0.567 | |

| 45–74 years | 1 | 72% | 73% | 0.444 | 22% | 25% | 0.011 | 66% | 65% | 0.881 |

| 2 | 72% | 75% | 0.080 | 22% | 22% | 0.871 | 64% | 64% | 0.806 | |

| 3 | 70% | 68% | 0.264 | 22% | 15% | 0.000 | 63% | 60% | 0.204 | |

| 4 | 70% | 74% | 0.031 | 22% | 19% | 0.050 | 63% | 56% | 0.010 | |

| 5 | 70% | 71% | 0.718 | 23% | 20% | 0.203 | 63% | 57% | 0.039 | |

| 6 | 71% | 71% | 0.803 | 25% | 21% | 0.040 | 63% | 61% | 0.406 | |

| 7 | 72% | 70% | 0.208 | 25% | 21% | 0.085 | 63% | 56% | 0.006 | |

| 8 | 75% | 70% | 0.044 | 26% | 24% | 0.450 | 63% | 59% | 0.116 | |

| 9 | 71% | 71% | 0.827 | 23% | 18% | 0.045 | 62% | 60% | 0.372 | |

| 10 | 72% | 70% | 0.385 | 24% | 21% | 0.285 | 63% | 65% | 0.540 | |

| 11 | 75% | 75% | 0.821 | 25% | 26% | 0.646 | 63% | 61% | 0.388 | |

| 12 | 74% | 75% | 0.634 | 24% | 21% | 0.109 | 66% | 64% | 0.338 | |

| 75+ | 1 | 87% | 88% | 0.559 | 40% | 46% | 0.007 | 74% | 75% | 0.954 |

| 2 | 86% | 88% | 0.183 | 41% | 47% | 0.014 | 74% | 74% | 1.000 | |

| 3 | 87% | 88% | 0.526 | 39% | 45% | 0.024 | 74% | 70% | 0.119 | |

| 4 | 87% | 90% | 0.026 | 41% | 48% | 0.103 | 72% | 68% | 0.268 | |

| 5 | 88% | 90% | 0.212 | 38% | 37% | 0.850 | 75% | 65% | 0.005 | |

| 6 | 89% | 91% | 0.048 | 41% | 36% | 0.205 | 73% | 72% | 0.800 | |

| 7 | 89% | 91% | 0.078 | 41% | 51% | 0.042 | 76% | 71% | 0.143 | |

| 8 | 90% | 89% | 0.782 | 42% | 47% | 0.358 | 76% | 70% | 0.095 | |

| 9 | 88% | 88% | 1.000 | 43% | 46% | 0.524 | 76% | 71% | 0.127 | |

| 10 | 88% | 85% | 0.017 | 39% | 32% | 0.217 | 75% | 76% | 0.775 | |

| 11 | 89% | 88% | 0.500 | 40% | 40% | 0.923 | 76% | 72% | 0.232 | |

| 12 | 89% | 88% | 0.224 | 41% | 38% | 0.464 | 75% | 76% | 0.623 |

Overall, the percentage of admissions from the ED remained more stable in children than in adults (Table 3). The percentage of pneumonia cases admitted among aged 0–44 was similar to the previous year, while for 45 and over there were some fluctuations over the year. The percentage for URTI cases was significantly lower among those aged 18–44 from March till October and December (p < 0.05), for other ages there were some fluctuations over the year. Infants under a year old showed a higher admission rate for asthma and wheezing during March, June and December (p < 0.05) only, and children aged 1–17 showed a decrease only in April and increase only in November (p < 0.05). Among adults percent admitted for asthma or COPD was reduced in some months compared to previous years.

4. Discussion

Our analysis, extracted from the national ED Visits Database and covering data from all 29 general hospitals in Israel, demonstrated the effect of the waves of pandemic activity on non-COVID ED visits and hospitalizations during the first year of the pandemic, compared with parallel months in the previous, pre-pandemic years.

The study demonstrates a dramatic reduction in respiratory ED visits in parallel to lockdowns and stay at home orders during both pandemic waves in all age groups and diagnoses. The decrease was more prominent in infants and children (under 1 year and 1–17 olds) compared with adults.

4.1. What could explain this drop in ED visits?

During the first year of the pandemic, public health measures were the main defence strategy to reduce transmission, in Israel as in other countries. Campaigns urged people to use telemedicine where possible. [11] Paediatrician visits became more available via telephone or video chat through the HMO, which may have relieved burden on urgent care services. Use of telemedicine visits jumped from 15% in 2019 to 29% in 2020 [12], with a marked increase in older patients, and minority groups which had previously low use of digital services. [13] Furthermore, schools were closed for 8 weeks during the first wave and while preschool and younger schoolchildren subsequently returned to the classroom, the majority of older schoolchildren did not return to full in-person classes until after the second wave. Mandatory face masks from April 12, 2020, for children aged 6+ and adults, in public spaces, including schools, probably contributed to the decrease of viral transmission, since masks were associated with a 47% decrease in transmission of respiratory viruses in the general (non-healthcare workers) population. [14] A retrospective analysis of daily viral positive tests, daily ED visits and hospitalizations during a 10-year follow-up in Canada revealed that community respiratory viruses were a major driver of ED visits and hospitalizations due to respiratory tract infections and COPD but hardly contributed to asthma. [15]

Lower incidence of influenza has been reported in Israel [16] as well as in other countries compared to previous years [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. The current findings show variations across age groups for pneumonia, and other acute respiratory disorders. Data from one US medical centre reported a significant drop in pediatric ED visits for acute respiratory illnesses over 3 months (March–May 2020) compared to previous years. [17] This pattern is supported here with national data across a whole year from Israel, and excluding patients ultimately found to be COVID-19 positive, allowing a comprehensive analysis of changing ED use in relation to the timing of the pandemic peaks of increased infection incidence.

Infants had dramatically reduced ED visits for all respiratory causes during the two pandemic waves. This points both to less morbidity due to lockdowns, but also to possible overuse in this population during routine times, in addition to parents' fear of their infants contracting COVID-19 infection while waiting in the ED, or upon admission to the wards. Analysis of hospital admissions can indicate severity of cases, and whether changes in use of ED for respiratory conditions represent underuse or usual overuse. [18] The admission rate for infants and children varied but in general did not increase dramatically in most months. The admission rate remained largely unchanged in older adults, indicating that cases coming to the ED during 2020 were not more severe than usual. This supports the assumption that the major contributor to decreased ED visits is a true decrease in need – less respiratory infections that cause UTRI and pneumonia.

Changes in urgent asthma visits can shed light on changes in overall respiratory morbidity since exacerbation of asthma in infants is related to respiratory viruses in more than 80% of cases. Other reasons are exposure to both indoor and outdoor allergens and pollutants and poor medical control. [19] Asthma visits and proportion of children admitted dropped during the first two COVID waves which involved lockdowns, and then spiked in June 2020, corresponding with relaxation of restrictions and opening of schools. Other cases are seasonal and allergy-related, potentially explaining the peaks in June and October among children. Lockdowns, face-mask wearing and less exposure to other children during remote learning might explain a considerable reduction in asthma related ED visits.

Studies of asthma in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic have shown reduced hospitalizations, fewer ED visits, and improved asthma control during the pandemic, and have linked these favourable outcomes to lockdowns and school closures [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21]].

In contrast, older groups suffer more from COPD and less from seasonal/allergic asthma. Reductions in COPD were demonstrated throughout the pandemic year, likely influenced by fewer viruses circulating and less air pollution during lockdowns. COPD is correlated with increased risk of severe pneumonia and poor outcomes when patients develop COVID-19. This might divert patients to avoid utilization of healthcare services which require physical contact like ED visits. [20] Older age groups showed smaller reductions in ED visits for pneumonia, which are less affected by outdoor influences in frail older populations.

Different patterns in children and adults may indicate different behaviours, with older adults staying home more, wearing masks and maintaining physical distance from others, while young children were less likely to wear masks (correctly) and to social distance. The greatest change in children's exposure was likely related to school closures. In the summer months when restrictions were relaxed, children were back at school/summer camps and congregating with others, likely to a greater degree than adults. This might explain a 72% increase during June 2020, compared with June 2019, of asthma related ED visits. This contrasts with the US which had consistently lower pediatric asthma-related ED visits throughout the year, but also did not re-open schools during this period. [21]

Strengths of the study include comprehensive data from all ED departments, and exclusion of COVID 19 positive patients in order to eliminate COVID morbidity and examine the effect of the pandemic on other respiratory morbidity. All the data are aggregative preventing analysis based on individual factors.

5. Conclusion and implications

National data from the whole of 2020 demonstrated fewer ED visits for non-COVID respiratory causes occurring throughout the pandemic year compared to the previous year, with the sharpest decrease during the two lockdowns, especially among young children The marked reduction in URTIs suggests that improved hygiene measures, such as mask wearing and social distancing during peaks of respiratory infections could be implemented in the future to reduce morbidity in influenza, RSV and other viral outbreaks and not only during the COVID-19 era.

Improved access to community services during out-of-hours or more accessible remote communication with the paediatrician to support parents in the management of children's illnesses could be considered to reduce burden on ED in this age group. Indeed, additional services provided by HMOs during the pandemic, including telephone and other virtual visits, may have had an impact on ED visits, with GPs and paediatricians being more available, in Israel [22] as elsewhere [23]. In this sense, the accelerated utilization of remote health created by the pandemic, if continued in the future, might reduce ED overuse in times of normalcy too. Indeed Bestsenny et al. estimated – based on US Medicare and Medicaid data - that in the future 20% of ED visits could be avoided or diverted using telemedicine and remote urgent care [24].

Changing patterns of ED use for URTI this year were probably due to a combination of both a reduced rate of viral diseases such as RSV and influenza, and also parents refraining from over exposure to the ED environment for fear of COVID-19 contamination. We can hope that this experience might prove to be an incentive in future years to reduce the use of ED services for mild URTI cases, some of which could be treated in the community.

As pandemic waves continue to come and go, and we attempt to adapt to the new normal and live with COVID, lessons can be learned from the past year. Parents should be reminded to keep home sick children to reduce the spread of respiratory and other diseases, and continued provision of virtual services may help reduce the burden on urgent care teams.

Funding

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ziona Haklai: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yael Applbaum: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Vicki Myers: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Mor Saban: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Ethel-Sherry Gordon: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Rachel Wilf-Miron: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Osnat Luxenburg: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

References

- 1.Sunagawa S., Iha Y., Kinjo T., Nakamura K., Fujita J. Disappearance of summer influenza in the Okinawa prefecture during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. Respir Investig. 2021;59(1):149–152. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2020.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Q.S., Wood T., Jelley L., Jennings T., Jefferies S., Daniells K., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on influenza and other respiratory viral infections in New Zealand. Nat Commun. 2021 Dec;12(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan S.G., Carlson S., Cheng A.C., Chilver M.B.N., Dwyer D.E., Irwin M., et al. Where has all the influenza gone? The impact of COVID-19 on the circulation of influenza and other respiratory viruses, Australia, March to September 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020 Nov;25(47) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.47.2001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olsen S. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1305–1309. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fricke L.M., Glöckner S., Dreier M., Lange B. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions targeted at COVID-19 pandemic on influenza burden - a systematic review. J Inf Secur. 2021;82(1):1–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekine I., Uojima H., Koyama H. Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department patient trends in Japan: a retrospective analysis. Acute Med Surg. 2020;7(1) doi: 10.1002/ams2.603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucero A., Lee A., Hyun J., Lee C., Pan L. Underutilization of the emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(6):15–23. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.8.48632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matera L., Nenna R., Rizzo V. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic impact on pediatric emergency rooms: a multicenter study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8753. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CBS. Central Bureau of Statistics Israel Localities. 2020. https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/Pages/2019/יישובים-בישראל.aspx Accessed June 24, 2020. 2019.

- 10.Silcocks P. Estimating confidence limits on a standardized mortality ratio when the expected number is not error free. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994;48:313–317. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Rosa S., Spaccarotella C., Basso C., Calabrò M.P., Curcio A., Filardi P.P., et al. Reduction of hospitalizations for myocardial infarction in Italy in the COVID-19 era. Eur Heart J. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.OECD Health at a glance 2021: Digital health. 2021. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/08cffda7-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/08cffda7-en

- 13.Linder R. Israel after Corona - Remote Services Reaching New Audiences. 2021. https://www.themarker.com/coronavirus/.premium-1.8887367. The Marker.

- 14.Liang M., Gao L., Cheng C., Zhou Q., Uy J.P., Heiner K., et al. Efficacy of face mask in preventing respiratory virus transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satia I., Cusack R., Greene J.M., O’Byrne P.M., Killian K.J., Johnston N. Prevalence and contribution of respiratory viruses in the community to rates of emergency department visits and hospitalizations with respiratory tract infections, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. PLoS One. 2020;15(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICDC . Report for the Week Ending in December 19, 2020. Israel Centre for Disease Control; 2020. Monitoring respiratory viruses in Israel.https://www.gov.il/he/departments/publications/reports/corona-flu-19122020 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddadin Z., Blozinski A., Fernandez K., Vittetoe K., Greeno A., Halasa N., et al. Changes in pediatric emergency department visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11(4) doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-005074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long C.M., Mehrhoff C., Abdel-Latief E., Rech M., Laubham M. Factors influencing pediatric emergency department visits for low-acuity conditions. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(5):265–268. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu L.S., Tsai M.C. Asthma exacerbation in children: a practical review. Pediatr Neonatol. 2014;55(2):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung J.M., Niikura M., Yang C.W.T., Sin D.D. COVID-19 and COPD. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2) doi: 10.1183/13993003.02108-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheehan W., Patel S., Margolis R., Kachroo N., Pillai D., Teach S. Pediatric asthma exacerbations during the COVID-19 pandemic: absence of the typical fall seasonal spike in Washington DC. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pr. 2021;9(5):2073. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grossman Z., Chodick G., Reingold S.M., Chapnick G., Ashkenazi S. The future of telemedicine visits after COVID-19: perceptions of primary care pediatricians. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2020;9:53. doi: 10.1186/s13584-020-00414-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiks A.G., Jenssen B.P., Ray K.N. A defining moment for pediatric primary care telehealth. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(1):9–10. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bestsennyy O., Gilbert G., Harris A., Rost J. Telehealth – A Quarter Trillion Dollar Post-COVID-19 Reality. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/telehealth-a-quarter-trillion-dollar-post-covid-19-reality