Abstract

Background

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) can be challenging for high thrombus burden and catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction. The Xposition-S stent was designed to prevent stent undersizing and minimize strut malapposition. We evaluated 1-year clinical outcomes of a nitinol, self-apposing®, sirolimus-eluting stent, pre-mounted on a novel balloon delivery system, in de novo lesions of patients presenting with STEMI undergoing pPCI.

Methods

The iPOSITION is a prospective, multicenter, post-market, observational study. The primary endpoint, target lesion failure (TLF), was defined as the composite of cardiac death, recurrent target vessel myocardial infarction (TV-MI), and clinically driven target lesion revascularization (TLR).

Results

The study enrolled 247 STEMI patients from 7 Italian centers. Both device and procedural success occurred in 99.2% of patients, without any death, TV-MI, TLR, or stent thrombosis during the hospital stay and at 30-day follow-up. At 1 year, TLF occurred in 2.6%, cardiac death occurred in 1.7%, TV-MI occurred in 0.4%, and TLR in 0.4% of patients. The 1-year stent thrombosis rate was 0.4%.

Conclusions

The use of an X-position S self-apposing® stent is feasible in STEMI pPCI, with excellent post-procedural results and 1-year outcomes.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, clinical trials, self-apposing stent, nitinol stent, interventional device, innovation, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), complex, primary PCI, drug-eluting stent

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death worldwide. The incidence of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) ranges from 43 to 144 new cases per 100,000 per year in Europe, with 116 per 100,000 cases per year in Italy [1]. In STEMI, prompt reperfusion by primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) and drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation is the recommended strategy, within indicated timeframes [2, 3]. In the acute phase, catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction and high thrombus burden can interfere with proper lumen diameter evaluation and stent sizing. Subsequently, the dissolution of jailed thrombotic material and vessel relaxation can result in strut malapposition, with increased risk of stent thrombosis over time [4–6]. A self-apposing® stent, which dynamically adapts to the vessel wall after the index procedure with a continuous radial force, can be a promising therapeutic option [7–9]. This observational study aimed to collect clinical data to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a nitinol, self-apposing®, sirolimus-eluting stent, pre-mounted on a novel balloon delivery system, in de novo lesions of native coronary arteries of patients presenting with STEMI.

Methods

Study overview

The iPOSITION Registry (Prospective, observational, Italian multi-center registry of selfaPposing ® cOronary Stent in patients presenting with ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarc-TION) was an Italian, prospective, multicenter, post-market, observational study. The study was conducted in full conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local medical ethics committees of all participating sites. Written informed consent was obtained before inclusion. The iPOSITION study was registered to the National Institutes of Health database with reference number NCT02979236 (full details available at https://clinicaltrials.gov).

Patient selection and procedural instructions

Patients older than 18 years, presenting with STEMI, undergoing pPCI, in which use of the Xposition S (STENTYS S.A., Paris, France) stent was planned at the operator’s discretion, were eligible for inclusion. Patients with at least one of the following criteria were excluded: cardiogenic shock at presentation, severe tortuous vessels, highly calcified lesions, intrastent pathology, multiple lesions requiring stenting in the target vessel, known allergies to stent components, inability to comply with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), known comorbidities conditioning life expectancy to less than 1 year, known pregnancy or childbearing potential, and inability to provide written informed consent. Accurate lesion preparation with pre-dilation was encouraged, when deemed feasible, to obtain a residual stenosis diameter < 30%. Post-dilation was recommended, preferably using a non-compliant balloon of the same size of the reference vessel diameter. After the pPCI procedure, all patients were transferred to a coronary intensive care unit and treated according to local protocols.

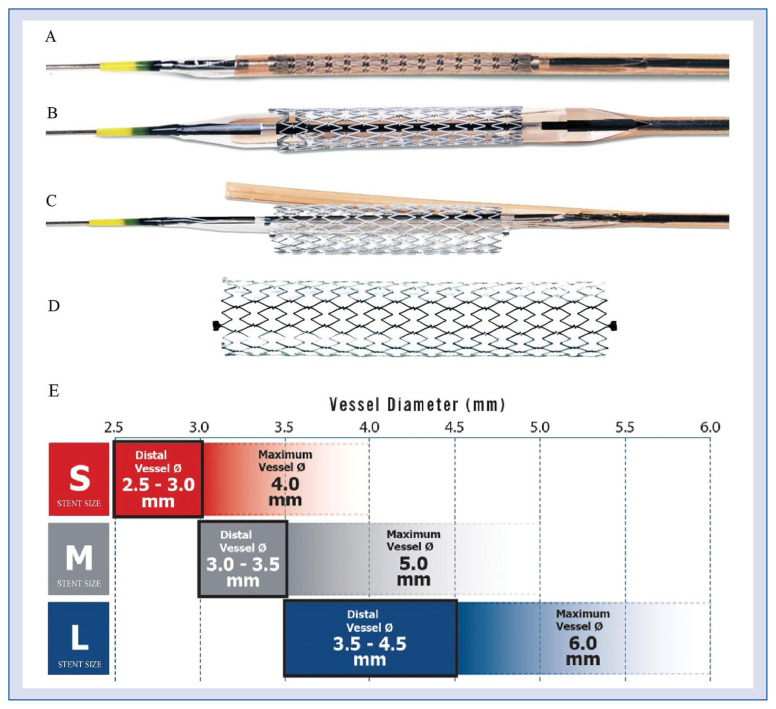

Device description

The Xposition S, available on the market since the beginning of 2016, is a new generation self-apposing® DES, pre-mounted on a novel balloon delivery system (Fig. 1). The stent is made of a Z-shaped mesh of nitinol (nickel/titanium alloy) and incorporates 1.4 μg/mm2 of sirolimus in a durable polymer matrix (ProTeqtor®) of polysulfone and soluble polyvinylpyrrolidone. Small interconnections between stent struts allow disconnections for easy side branch access in bifurcation setting. The stent is available in four lengths (17, 22, 27, and 37 mm) and three sizes suitable for reference vessel diameters of 2.5–3.0 mm (small), 3.0–3.5 mm (medium), and 3.5–4.5 mm (large), compatible with a maximum vessel diameter of 6 mm (Fig. 1E). Strut thickness ranges from 103 μm (small size) to 133 μm (medium and large sizes). The stent is folded on a delivery balloon, which is covered with a distal “splitable” sheath assembly. The nominal diameter of the delivery balloon is the same as the smallest diameter for which the stent is suitable. When the semi-compliant delivery balloon is inflated within the sheath with a pressure of at least 12 atmospheres, the sheath assembly splits, and the stent is deployed. The sheath is then withdrawn together with the balloon.

Figure 1.

The Xposition S drug-eluting stent; A. The stent is pre-mounted on a semi-compliant balloon and is restrained by a pre-cut sheath; B. Balloon inflation splits the stent from distal to proximal and releases the self-apposing® stent; C. The balloon is then deflated; D. The balloon and the sheath are then withdrawn leaving the stent apposed to the vessel wall; E. Xposition S stent sizes.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the occurrence of target lesion failure (TLF) at 1-year follow-up. TLF was defined as the composite of cardiac death (CD), recurrent target vessel myocardial infarction (TV-MI), and clinically driven target lesion revascularization (TLR). Secondary endpoints included the following: 30-day TLF, procedural success during the hospital stay, death from any cause, 30-day and 1-year stent thrombosis (ST), and any individual component of the primary endpoint. Procedural success was defined as any device success with the obtainment of vessel recanalization (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] grade 2–3 flow), a diameter stenosis ≤ 30% and without the occurrence of death, reinfarction, or repeated revascularization of the target vessel during the hospital stay. DAPT compliance was also investigated. A detailed overview of endpoint definition is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Sample size calculation

The predicted rate of 1-year TLF primary endpoint was 2.5% on the basis of data reported by a previous registry [10]. Hence, a minimum sample size of 235 patients was considered enough to provide a ± 2% estimation of the primary outcome with a type-I error of 5% and a power of 80%. Taking into account 5% as a possible rate of loss at follow-up, a total of 247 patients were finally enrolled.

Statistical methods

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation in the case of a normal distribution; conversely; when they were non-normally distributed, medians and quartiles were reported. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Time-to-event analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves; the comparison between curves was obtained with the log-rank test. We considered p < 0.05 for statistical significance. Variables associated with 1-year TLF were identified by univariate Cox proportional hazard regression. Hazard ratios (HR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and p-values were reported. All the analyses were performed with SPSS (IBM Corp., IBM SPSS Version 24.0., Armonk, NY, US), Med-Calc (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium), and R-project (Core Team 2013, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria); p < 0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance.

Results

A total of 247 STEMI patients were enrolled in 7 Italian centers from June 2016 to July 2018. Eighteen patients were lost at 1-year follow-up, so the final analysis was performed on 229 patients.

Baseline characteristics

Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 61 ± 11 years, with the majority being male (83%). More than half of the patients had systemic arterial hypertension (51%), and almost one in two was an active cigarette smoker (46%), 30% had coronary artery disease, a quarter had hypercholesterolemia (25%), and 13% had diabetes mellitus. Most of the patients presented in Killip class I (88.7%), with more than a half less than 3 h from symptom onset (54%). Culprit lesions were identified predominantly in the right coronary artery (43%) and the left anterior descending coronary artery (41%). Only a minority of patients required a pPCI of the left main (n = 4). High thrombus burden (TIMI thrombus burden 4–5) was identified in 41% of lesions and required thrombus aspiration in 30% of cases; 24% of lesions involved a bifurcation site. A complete overview of angiographic and procedural characteristics is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

iPOSITION baseline demographic characteristics, clinical history, cardiovascular risk factors, clinical presentation, and procedural characteristics.

| BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS | |

| Age [years] | 60.9 ± 10.9 |

| Sex (male) | 204 (82.6%) |

| Clinical history | |

| Previous MI (> 30 days) | 9 (3.6%) |

| Previous CABG | 3 (1.2%) |

| Previous PCI | 11 (4.5%) |

| Previous stroke/TIA | 4 (1.6%) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Hypertension | 126 (51.0%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (13.4%) |

| Renal dysfunction (GFR < 60 mL/ /min/1.73 m2) | 7 (2.8%) |

| Smoker: | |

| Active smoker | 113 (45.7%) |

| Former smoker | 33 (13.4%) |

| Family history CAD | 74 (30%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 62 (25.1%) |

| Time from onset of symptoms | |

| < 3 h | 134 (54.3%) |

| ≥ 3 h and < 6 h | 74 (30.0%) |

| ≥ 6 h and <12 h | 28 (11.3%) |

| ≥ 12 h | 11 (4.5%) |

| Killip class | |

| I | 219 (88.7%) |

| II | 19 (7.7%) |

| III | 4 (2.0%) |

| IV | 0 (0.0%) |

| Unknown | 4 (1.6%) |

| Lesion location | |

| RCA | 107 (43.3%) |

| LM | 4 (1.6%) |

| LAD | 101 (40.9%) |

| LCX | 34 (13.8%) |

| Ramus | 2 (0.8%) |

| Lesion characteristics | |

| Reference vessel diameter [mm] | 3.40 ± 0.46 |

| Length [mm] | 26.1 ± 10.5 |

| High thrombus burden (TIMI thrombus grade ≥ 4) | 101 (40.9%) |

| Ostial lesion | 18 (7.3%) |

| Bifurcation | 58 (23.5%) |

| Calcifications (≥ mild) | 37 (15.0%) |

| Tortuosity (≥ mild) | 12 (4.9%) |

| Xposition S size | |

| S (2.5–3.0 mm) | 60 (24.3%) |

| M (3.0–3.5 mm) | 127 (51.4%) |

| L (3.5–4.5 mm) | 60 (24.3%) |

| Xposition S length | |

| 17 mm 30 | (12.1%) |

| 22 mm 86 | (34.8%) |

| 27 mm 73 | (29.6%) |

| 37 mm 58 | (23.5%) |

| Techniques used | |

| QCA assessment | 12 (4.9%) |

| Intravascular imaging (IVUS or OCT) | 6 (2.4%) |

| Thrombus aspiration | 73 (29.6%) |

| Pre-dilation | 204 (82.6%) |

| Post-dilation | 186 (75.3%) |

| POST-PROCEDURAL OUTCOMES | |

| Procedural outcomes | |

| TIMI flow post: | |

| 0 | 0 (0.0%) |

| 1 | 2 (0.8%) |

| 2 | 16 (6.5%) |

| 3 | 227 (92.7%) |

| Postprocedural vessel dissection | 3 (1.2%) |

Variables have been reported as mean ± standard deviation or number (%). MI — myocardial infarction; CABG — coronary artery by-pass graft; PCI — percutaneous coronary intervention; TIA — transient ischemic attack; GFR — glomerular filtration rate; CAD — coronary artery disease; RCA — right coronary artery; LM — left main; LAD — left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX — left circumflex coronary artery; TIMI —Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; QCA — quantitative coronary analysis; IVUS — intravascular ultrasound; OCT — optical coherence tomography

Primary endpoint

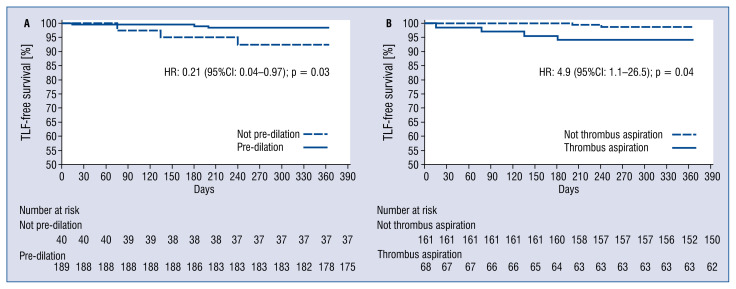

Eighteen (7.3%) patients were lost at 1-year follow-up. The primary endpoint of 1-year TLF occurred in 6 patients (2.6%; 95% CI 0.53–4.67). Four patients died, and all events were attributed to a cardiac cause, resulting in a 1-year cardiac death rate of 1.7% (95% CI 0.03–3.37). Recurrent TV-MI was observed in 1 patient (0.4%; 95% CI 0.0–1.22). Clinically indicated TLR was performed in 1 patient (0.4%; 95% CI 0.0–1.22). Freedom from TLF at 1-year follow-up was 97.4% ± 1.1%; it was significantly higher in patients whose lesions were treated with pre-dilation (98.4% ± 0.9% vs. 92.5% ± 4.2%, p = 0.03; Fig. 2A) and lower with thrombus aspiration (94.1% ± 2.9% vs. 98.7% ± 0.9%, p = 0.04; Fig. 2B). At univariate Cox regression, performing pre-dilation was associated with better freedom from TLF (HR = 0.21, 95% CI 0.04–0.97); conversely, thrombus aspiration was associated with worse freedom from TLF (HR = 4.9, 95% CI 1.1–26.5). All the other variables reported in Table 1 were also tested, but none of them was significantly associated with 1-year TLF.

Figure 2.

A. Freedom from target lesion failure at 1 year; comparison between patients whose lesions were treated with pre-dilation (solid line) and those whose were not (dashed line); B. Freedom from target lesion failure at 1 year; comparison between patients whose lesions were treated with thrombus aspiration (solid line) and those whose were not (dashed line).

Secondary endpoint

Both device and procedural success occurred in 99.2% (95% CI 98.09–100%) of patients, without any death, recurrent TV-MI, TLR, or ST during the hospital stay and at 30-day follow-up. A single event of possible ST occurred, resulting in a 1-year ST rate of 0.4% (95% CI 0.0–1.22%).

DAPT compliance

Almost all patients were on DAPT after discharge (99%), 94% with a potent P2Y12 inhibitor (ticagrelor or prasugrel) and acetylsalicylate (n = 232). A total of 95% of patients (n = 213) were still on DAPT at 1-year follow-up. Three patients had switched to oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation or mechanical heart valve implantation. The remaining 4% of patients (n = 9) had switched to a single antiplatelet therapy, four with acetylsalicylate and five with a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Discussion

Main findings

The present post-marketing registry clearly shows that the use of the Xposition S self-apposing ® stent is feasible in pPCI, with an excellent result in almost all STEMI patients. Good midterm outcomes corroborate such findings, with a significant TLF risk reduction when lesions were prepared with pre-dilation, without thrombus aspiration. Procedural and clinical outcomes were comparable to other currently available balloon-expandable DES in the same setting [11–13]. The APPOSITION III study [9, 10] investigated clinical outcomes in STEMI pPCI with the previous version of the same device. Although a direct comparison cannot be performed, we here document a much lower ST, leading to a lower 1-year TLF rate, because only a single possible ST event was observed. Several factor potentially contributed to this notable outcome improvement. First, the introduction and the extensive use of the more potent P2Y12 inhibitors could have strongly reduced thrombotic events [14]. Secondly, as we learned from the APPOSITION III itself [9, 10], a higher post-dilation rate might have reduced events by the improvement of strut apposition. Thirdly, even when post-dilation was not performed, the new releasing system in the iPOSITION may have guaranteed a larger stent expansion because of the balloon inflation, whereas in the APPOSITION III the stent expansion was left solely to its elastic properties, with an increasing risk of stent under-expansion [15–18].

We observed a high rate of 1-year DAPT compliance in our study, and patients with inability to comply with DAPT were excluded as per the protocol. Therefore, our results cannot be extended to a high bleeding risk population [19].

Unfortunately, we have to acknowledge that the Xposition S self-apposing® stent is currently no longer available in the market. The Stentys Company claimed that its search for a strategic partner failed, and subsequently its shareholders voted for dissolution.

Technical insight

Statistic regression with univariate Cox model and subgroup analysis (Fig. 2) revealed lesion predilation and avoidance of thrombus aspiration were associated with a lower 1-year TLF rate. The lack of clinical benefits of thrombus aspiration in STEMI pPCI has already been proven in randomized clinical trials [20–22]. Pre-dilation may favor lesion preparation before stenting, but concerns about the risk of no-reflow phenomenon due to thrombotic debridement and microcirculatory impairment often discourage this approach in STEMI [23–26]. The clinical benefit of pre-dilation in our study could be a hypothesis-generating result for further future investigations.

Limitations of the study

The results should be interpreted with caution because of several limitations: 1) iPOSITION enrolled non-randomized and non-consecutive patients, so a selection bias cannot be excluded, 2) variables associated with 1-year TLF events were not tested in a multivariate model for low event rates, 3) clinical follow-up was limited to 1 year, and a longer observation would be advisable to explore the response to DAPT demodulation, 4) no data on the completeness of revascularization were collected [27], 5) events were not adjudicated by an independent clinical event committee, and 6) a slightly high rate of patients were lost at follow-up.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicenter Italian registry evaluating the performance of the nitinol self-apposing DES in a STEMI population and the first worldwide study weighing up the self-apposing DES novel balloon delivery system. Both procedural success and 1-year clinical outcomes were excellent. Although acknowledging the current unavailability of the device on the market, we should further investigate such a promising device in order to better define the role of self-apposing® DES in STEMI pPCI.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr M. Di Biasi from Interventional Cardiology Unit of “L. Sacco” Hospital, Milano, Italy and Dr. A. Ferraro from Interventional Cardiology Unit of “P. Ciaccio” Hospital, Catanzaro, Italy for their patient screening and enrolment.

Footnotes

This paper was guest edited by Prof. Krzysztof J. Filipiak

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(8):943–957. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(2):87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Hear J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook S, Windecker S. Early stent thrombosis: past, present, and future. Circulation. 2009;119(5):657–659. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Werkum JW, Heestermans AA, Zomer AC, et al. Predictors of coronary stent thrombosis: the Dutch Stent Thrombosis Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(16):1399–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Hoeven BL, Liem SS, Jukema JW, et al. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: 9-month angiographic and intravascular ultrasound results and 12-month clinical outcome results from the MISSION! Intervention Study J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(6):618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spaulding C, Amoroso G, Verheye S, et al. Assessment of the safety and performance of the stentys self-expanding coronary stent system in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(10):A105.E977. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)60978-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Geuns RJ, Tamburino C, Fajadet J, et al. Self-expanding versus balloon-expandable stents in acute myocardial infarction: results from the APPOSITION II study: self-expanding stents in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(12):1209–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu H, Grundeken MJ, Vos NS, et al. Clinical outcomes with the STENTYS self-apposing coronary stent in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: Two-year insights from the APPOSITION III registry. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:e572–e577. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-16-00676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch KT, Grundeken MJ, Vos NS, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of the STENTYS Self-Apposing¨ coronary stent in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the APPOSITION III registry. EuroIntervention. 2015;11(3):264–271. doi: 10.4244/EIJY15M02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofma SH, Brouwer J, Velders MA, et al. Second-generation everolimus-eluting stents versus first-generation sirolimus-eluting stents in acute myocardial infarction. 1-year results of the randomized XAMI (XienceV Stent vs. Cypher Stent in Primary PCI for Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(5):381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu D, Lu TF, Matter CM, et al. Effect of biolimus-eluting stents with biodegradable polymer vs bare-metal stents. JAMA. 2012;308:777–787. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabate M, Cequier A, Iñiguez A, et al. Everolimus-eluting stent versus bare-metal stent in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (EXAMINATION): 1 year results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9852):1482–1490. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2017:213–254. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezx334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura M, Mintz GS, Carlier S, et al. Outcome after acute incomplete sirolimus-eluting stent apposition as assessed by serial intravascular ultrasound. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(4):436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujii K, Carlier SG, Mintz GS, et al. Stent underexpansion and residual reference segment stenosis are related to stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: an intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(7):995–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong MK, Mintz GS, Lee CW, et al. Intravascular ultrasound predictors of angiographic restenosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(11):1305–1310. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheneau E, Leborgne L, Mintz GS, et al. Predictors of subacute stent thrombosis: results of a systematic intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 2003;108(1):43–47. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078636.71728.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corpataux N, Spirito A, Gragnano F, et al. Validation of high bleeding risk criteria and definition as proposed by the academic research consortium for high bleeding risk. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(38):3743–3749. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svilaas T, Vlaar PJ, van der Horst IC, et al. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(6):557–567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fröbert O, Lagerqvist Bo, Olivecrona GK, et al. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(17):1587–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, et al. TOTAL Investigators. Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(15):1389–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Rakowski T, et al. Impact of direct stenting on outcome of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (from the EUROTRANSFER registry) Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;84(6):925–931. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bessonov I, Zyrianov I, Kuznetsov V, et al. TCTAP A-024 comparison of direct stenting versus pre-dilation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(16):S10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.035.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azzalini L, Millán X, Ly HQ, et al. Direct stenting versus pre-dilation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Interv Cardiol. 2015;28(2):119–131. doi: 10.1111/joic.12190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahmoud KD, Jolly SS, James S, et al. Clinical impact of direct stenting and interaction with thrombus aspiration in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: Thrombectomy Trialists Collaboration. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(26):2472–2479. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimarino M, Curzen N, Cicchitti V, et al. The adequacy of myocardial revascularization in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):1748–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.