During the past year, the fast-spreading new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1] has led to the outbreak of a pandemic that has changed our lives. The increase in the overall mortality [2] results from the viral infection itself but also derives from the lack of access to vital medical treatments, and the health systems being utterly challenged by the worldwide pandemic. On top of this, social distancing and travel limitations have impeded the physical presence of proctors during innovative procedures in developing centers, reducing the spread of medical knowledge and patients’ access to cutting-edge technologies.

The idea of telemedicine and remote proctoring emerged already in the pre-covid era [3], as a solution to uneven distribution of up-to-date medical treatments in the modern-day world. In cardiology, there are reports on successful tele-proctored catheter-based atrial fibrillation (AF) ablations [4] and transcatheter aortic valve implantations [5]. However, to our knowledge, there are no reports on cryoballoon (CB) remote-proctored AF ablations. We believe that CB technology is perfectly suited to remote training thanks to its “single-shot” feature and reduced operator dependency compared with other AF ablation techniques.

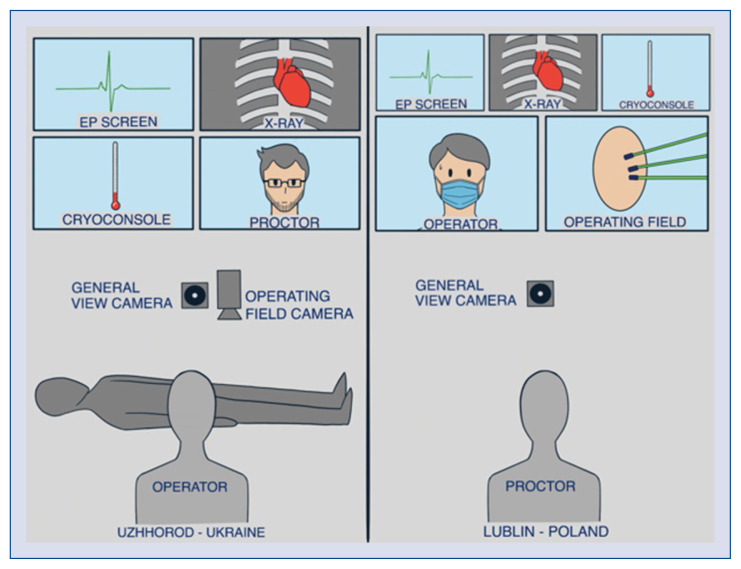

At the beginning of the pandemic, a CB ablation proctor affiliated to the Department of Cardiology of the Medical University of Lublin, Poland (A.G.) was scheduled to visit the Cardiac Center in Uzhhorod, Zakarpattia Oblast, Ukraine, to provide expert support with the first-in-site CB AF ablation procedures. Considering the consecutive waves of the pandemic, we decided to perform the cases with the “remote-presence” technique [3]. To ensure maximum safety and effectiveness of the training, two main issues had to be addressed: the on-site presence of a skilled operator, and a high-quality, real-time audiovisual connection. The first issue was overcome by inviting an operator experienced in classic AF ablation from the Amosov National Institute of Cardiovascular Surgery in Kyiv, Ukraine (M.P.), who had no travel restrictions within Ukraine. The second was solved by arranging a pre-procedural “sham” (no patient-involved) remote ablation, which allowed us to test the audiovisual connection between the virtual operating room (vOR) in the Medical Simulation Center in Lublin (Poland) and the real operating room (rOR) in the Cardiology Clinic at Uzhhorod (Ukraine), separated by a distance of 400 km, which showed that we had a reliable high-resolution real-time audio-visual connection between the two centers. DellTM (Dell Inc., US) and AppleTM portable computers (Apple Inc., US) together with compatible external camera-microphone units, smartphones (iPhone XS, Apple Inc, US), and a dedicated protected health information (PHI-secure) Zoom platform providing end-to-end 256-bit encryption (Zoom Video Communications Inc., US) with a backup Internet connection were used to ensure audio-visual communication. In the vOR in Poland, the transmitted images from the EP system (CardioLab, GE Prucka, US), fluoroscopy screen (Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, Netherlands), cryoconsole (Medtronic, USA), and the operation site view were combined in one 60-inch high-resolution flat screen (LG Corp., South Korea) to provide the proctor with full audiovisual access to the procedure (Fig. 1). Three patients with paroxysmal symptomatic AF were recruited for remotely proctored CB ablation. The patient characteristics and procedural data are presented in Table 1. All CB-based pulmonary vein isolation procedures were performed in accordance with European Society of Cardiology guidelines [6], as thoroughly described previously [7, 8].

Figure 1.

Visual transmission scheme between the operating room in Uzhhorod, Ukraine (left panel) and virtual operating room in the Medical Simulation Center in Lublin, Poland (right panel) with all live screens available to the operator and the proctor. Additional transmission of a high-definition operating field view is important to closely monitor all the operator’s maneuvers.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and procedural data of the remotely proctored cryoballoon ablations.

| Patients’ characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Patient | Age | Sex | EHRA score | LA diameter [cm] | LVEF [%] |

| 1 | 55 | Male | 2b | 4.5 | 63 |

| 2 | 48 | Male | 3 | 4.1 | 60 |

| 3 | 60 | Male | 2b | 4.3 | 56 |

|

| |||||

| Procedural parameters | |||||

|

| |||||

| Patient | Procedure time [min] | LA dwell time [min] | Fluoro time [min] | Number of PVs isolated | Complications |

|

| |||||

| 1 | 165 | 110 | 24 | 4/4 | No |

| 2 | 130 | 35 | 18 | 4/4 | No |

| 3 | 160 | 57 | 20 | 4/4 | No |

EHRA — European Heart Rhythm Association; LA — left atrium; LVEF — left ventricular ejection fraction; PVs — pulmonary veins

We present herein a first report on remote proctoring of CB-based AF ablations. The procedures were performed by an experienced point-by-point AF ablation operator under the remote guidance of an experienced cryoballoon ablation operator. All pulmonary veins were isolated, and there were no complications.

We believe that there are multiple advantages of a tele-proctoring approach. The most important is that it overcomes travel limitations and cuts travel expenditures [9], ensuring the access to novel cutting-edge procedures to virtually any place with access to a fast and reliable Internet connection [10]. Secondly, it eases the search for an available proctor. With fast Internet connection and readily available technical equipment, remotely-proctored services can be provided even by a quarantined physician, who otherwise would not be able to conduct any medical procedure — either on-site or remotely.

The key disadvantage of remote-presence-based teleproctoring is the lack of the physical presence of the proctor in the operating room. In the case of potential difficulties, he/she cannot take over the case with his/her own hands. This essential disadvantage can be, however, turned into an important benefit. Firstly, even with onsite proctoring for novel techniques, the trainee is usually a highly qualified operator, who should easily manage all procedure-related complications. Apparently, this is even more true with remote proctoring, which will result in the finest trainee preparation. Secondly, being aware of an attentive, yet not physically present proctor, and thus realizing that the procedure outcome depends literally on his/her own hands, the trainee might acquire the specific skills faster, which may result in a steeper learning curve. Our case series of remote monitoring of CB ablation demonstrates that teleproctoring in cardiac electrophysiology can be easily performed. However, its feasibility and safety are yet to be demonstrated, and further data are needed.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Andrzej Glowniak reports speaking and proctoring honoraria from Medtronic and Abbott; Marcin Sudol and Oksana Dyomenko are the Medtronic company employees; Gian-Battista Chierchia and Carlo de Asmundis reports speaker fees for Medtronic, Biotronik, Biosense Webster, Abbott, and proctoring honoraria from Medtronic. All other autors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Guan Wj, Ni Zy, Hu Yu, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannatà A, Bromage DI, McDonagh TA. The collateral cardiovascular damage of COVID-19: only history will reveal the depth of the iceberg. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(15):1524–1527. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith CD, Skandalakis JE. Remote presence proctoring by using a wireless remote-control videoconferencing system. Surg Innov. 2005;12(2):139–143. doi: 10.1177/155335060501200212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinoda Y, Sato A, Adach T, et al. Early clinical experience of radiofrequency catheter ablation using an audiovisual telesupport system. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17(5 Pt B):870–875. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arslan F, Gerckens U. Virtual support for remote proctoring in TAVR during COVID-19. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ccd.29504. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reissmann B, Heeger CH, Opitz K, et al. Clinical outcomes of cryoballoon ablation for pulmonary vein isolation: Impact of intraprocedural heart rhythm. Cardiol J. 2020 doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2020.0147. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glowniak A, Tarkowski A, Fic P, et al. Second-generation cryoballoon ablation for recurrent atrial fibrillation after an index procedure with radiofrequency versus cryo: Different pulmonary vein reconnection patterns but similar long-term outcome-Results of a multicenter analysis. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2019;30(7):1005–1012. doi: 10.1111/jce.13938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually Perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goel SS, Greenbaum AB, Patel A, et al. Role of Teleproctoring in Challenging and Innovative Structural Interventions Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(16):1945–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]