Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease is a life-threatening neurodegenerative disorder. About 50 million people across the globe are affected by this disease. At final stages, this disease causes patients to lose cognitive ability, memory, and brain cells to the point of being totally dependent on other individuals for livelihood. The incidence of this disease is increasing across the world in the recent years, making the need of a better drug an urgency. Existing drugs show various side effects and natural sources of medicinal drugs are being explored. In this study, we explore the activity of natural compounds isolated through GC–MS analysis from the haustoria of palmyra palm against two major Alzheimer’s disease-causing enzymes, β-secretase and acetylcholinesterase. The binding affinity of these compounds against the target proteins and their pharmacokinetic properties were checked. Among the 37 compounds docked, 5 compounds showed good binding affinity and pharmacokinetic properties. These natural compounds showed a potential as a drug against Alzheimer’s disease. Further research is needed to study the synergistic activity of the compounds in live cells.

Keywords: Borassus flabellifer, Alzheimer’s disease, GC–MS analysis, β-secretase, Acetylcholinesterase

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease, which gets worse over time. The pathology of the disease was first recognized by Dr. Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist, in a 51-year-old woman. He identified the presence of miliary foci (plaques) and fibrils (tangles) in the brain of the patient. After more than a century of identification of the disease and research, a complete solution to this disease is not available yet [1]. Various theories have been proposed to explain the onset of the disease. Pathological lesions caused by two proteins are believed to be the cause of Alzheimer’s disease, namely β-amyloid and phosphorylated tau protein tangles. Alzheimer’s disease is a life-threatening disease [2]. Alzheimer’s disease increases suffering and pain in the life of individuals and their families. Daily self-care activities become an impossible task at later stages of Alzheimer’s disease, putting tremendous pressure on the caregivers. The clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease include loss of memory and depreciation of the ability to speak and think [3].

The majority of the diseased individuals are above 65 years old. Recent studies show the possibility of incidence before 65 years of age. Fifty million people are affected by Alzheimer’s disease worldwide, out of which 4 million reside in India. Research suggests the APOE4 gene plays a major role in causing the disease. Cognitive impairment, loss of memory, difficulty in learning, and brain cell damage progress with time to make living normal lives difficult with the progress of time. The brain starts to shrink (atrophy), leading to a loss in memory, to the extent of forgetting important events in the life of patients. Incidence of psychopathic diseases may also occur [2].

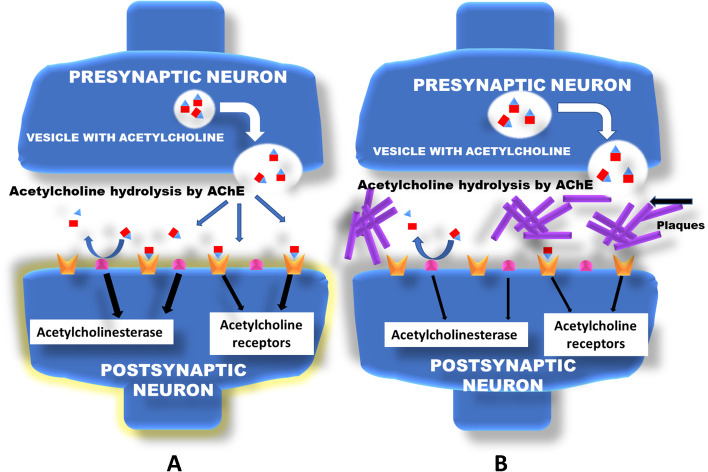

Acetylcholinesterase is a major enzyme required in the breakdown of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Fig. 1). The hydrolysis of acetylcholine to acetic acid and choline by acetylcholinesterase is necessary in healthy brain, but becomes an issue in Alzheimer’s disease [4]. This is because of the low concentrations of acetylcholine, which become even lower if acetylcholinesterase is left unchecked.

Fig. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of synaptic action of AChE (acetylcholinesterase) in healthy (A) and diseased (B) neuronal cells

The blocking of this enzyme is done by action of various drugs which are available for patients. Drugs like donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine block acetylcholinesterase to increase acetylcholine in synapses of neurons. These drugs have undesirable side effects, and better drugs are needed.

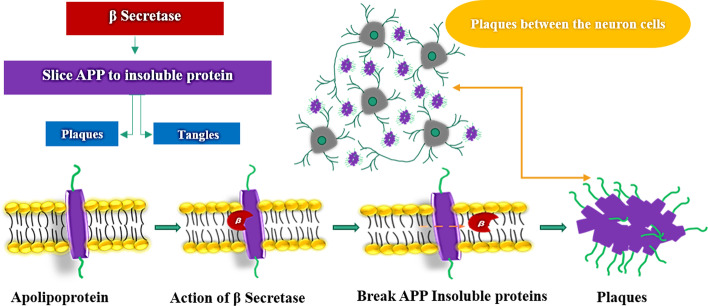

The amyloid precursor proteins (APP) are responsible for the growth and repair of neurons [3]. The APP is cleaved by enzymes and converts APP into soluble protein fibers and will be broken eventually and recycled. Three types of secretase enzymes are known to play a role in the cutting of APP which are α-secretase, β-secretase, and γ-secretase. However, in the case of the beta-secretase enzyme, it cleaves the amyloid precursor protein (APP) into insoluble monomer β-amyloid protein. The insoluble monomer protein fibers are sticky and adhere between the neuronal cells causing beta-amyloid plaques and tacky inside the neuron cells and create tangles (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Image showing the involvement of β-secretase in causing plaques and tangles. Presence of plaques in between neuron cells and the action of β-secretase on amyloid precursor protein is also shown

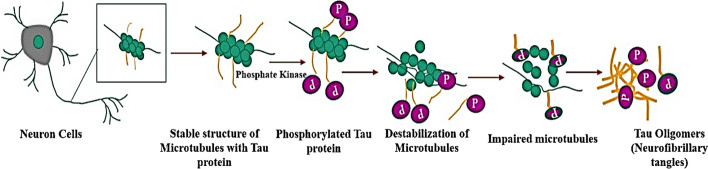

These plaques interrupt signals between neuron and neuron, block the blood vessels in the brain, and cause amyloid angiopathy, hemorrhage, and rupture of cells. The tau protein present between the microtubules prevents it from damage to the cytoskeleton (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Image showing formation of tau oligomers in the neuron cells

Insulin resistance plays a major role in Alzheimer’s disease. The exact mechanisms are unknown. The β-amyloid plaques initiate a cascade of reactions inside the microtubules by activating phosphate kinase and transfer phosphate group to tau protein. Tau protein structures are modified and stop supporting microtubules causing neurofibrillary tangles. This leads to neuron having non-functional microtubules, which then sends signals for apoptosis, leading to neuron death, i.e., atrophy. This atrophy causes the shrinking of the brain. This atrophy of brain cells leads to short-term memory, loss of motor skills and language, long-term memory loss, and disorientation of all of which lead ultimately to the person becoming bedridden and cause death [3]. Diagnosis is still a challenge and one definite way to diagnose the disease is not available till date.

With no ultimate remedy for the disease, researchers are still searching for a solution. Natural sources of compounds such as plants are also being explored due to the rich diversity of medicinal compounds present in plants [5]. India is known for its rich flora and abundance of medicinal plants across the nation. Earlier studies with the natural compounds show results that indicated that plant compounds are potential drug candidates against various diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease [6]. Natural compounds from medicinal plants are studied as they are less toxic and have lower side effects to synthetically prepared compounds. Here, in our study, we have identified potential compounds from the haustoria of Palmyra palm tree by GC–MS analysis. These compounds were then studied for docking affinities against two protein targets, namely acetylcholinesterase and β-secretase. The compounds showed good binding scores and had shown good ADME properties, indicating that these compounds have potential as drugs against Alzheimer’s disease.

Materials and Methods

Retrieval of Ligands

Thirty-six potential ligands were identified from palmyra palm ethanolic extract. PubChem and Chemspider databases were used for the retrieval of ligands. These ligands were chosen to be docked against target proteins. 3D structures of these ligands were downloaded for docking and ADME studies.

ADME and Toxicity Analysis

Failures in clinical trials of potential compounds could cause loss of time, money, and other resources. The possibility of such failures is significantly reduced when the ligands are checked for pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties. The computational studies on the structure of ligand could reveal how successful it would be under in vivo.

Swiss ADME (http://www.swissadme.ch) was used to screen the ligands for the best pharmacokinetically relevant compounds. ADME stands for absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Other factors including oral bioavailability, blood–brain-barrier permeability, and lead likeness are also considered. Lipinski’s rule of five was used to analyze the drug likeness of the chosen ligands.

Retrieval and Preparation of Protein

The target proteins were acetylcholinesterase and β-secretase. The proteins were retrieved from PDB database (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do). The protein ID for acetylcholinesterase is 2ACE (10.2210/pdb2ACE/pdb) and for beta-secretase, ID is 1SGZ (10.2210/pdb1SGZ/pdb). The proteins were prepared separately on the Discovery studio visualization tool. Polar hydrogens were added and Gasteiger charges were added.

Virtual Screening and Visualization

Acetylcholinesterase

Acetylcholinesterase is an enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine through hydrolysis to yield reusable derivatives which are recycled as transmitters [4]. The ligands were docked against the target protein using PyRx[7]. PyRx is a virtual screening software which can test for the binding affinity of multiple ligands against a target protein. PyRx is a useful, user-friendly, quick virtual screening tool.

AutoDock Vina plugin tool was used to dock the potential compounds retrieved from PubChem against acetylcholinesterase target protein. The entire protein was covered under grid box and docking was done. The scoring function of the virtual screening tool has a prominent place in predicting the degree of successful interaction between ligands against the target protein. The scoring function used is the AutoDock Vina tool in PyRx 0.8. The Discovery Studio visualization tool was used to visualize the docked compounds [8].

Beta-Secretase

Beta-Secretase is an enzyme that is responsible for the incorrect cleaving of the amyloid precursor protein to give beta-amyloid fragments which cause plaques and disrupt brain signalling[9]. The ligands were docked against the protein through PyRx virtual screening tool [7].

AutoDock Vina plugin tool was used to dock the potential compounds retrieved from PubChem against beta-secretase target protein. Complete protein was covered under grid box and docking was done. The visualization of docked ligands was done using Discovery Studio visualization tool.

Results and Discussion

Prediction of Drug Likeness Through ADMET Analysis

Computational methods have been used to predict the drug likeness and pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds. The selected compounds were screened for the ADME analysis and the best compounds were studied further for binding scores. ADME stands for absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Pharmacokinetic properties are to be studied before the clinical trials for potential compounds to decrease failure under in vivo studies. Parameters including molecular weight, number of hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, rotatable bonds, and Log P value are checked for the estimation of drug likeness of the compounds. Lipinski’s rule of five is used to study the drug likeness and predict the possibility of successful trial under in vivo conditions[10]. Other factors such as gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain-barrier permeability, and bioavailability were checked.

Log P values are a major player in the success of a potential compound. Best scores for Log P are below 5. Higher Log P values indicate the compounds have high metabolic turnover and low solubility and oral absorption, which are not optimal for potential drug candidates. Bioavailability scores of 0.55 are considered best. Bioavailability scores are a combination of Lipinski’s rule of five, TPSA, and molecular charge. Verber’s rule scores also indicate the oral availability of a potential compound.

All the compounds showed good pharmacokinetic properties and showed to be promising compounds for further research. Particularly 4 compounds showed excellent properties, viz. Thiazolo[3,2-a]benzimidazol-3(2H)-one,2-(4-acetoxybenzylideno)-, Phenanthro[1,2-b]furan-10,11-dione,6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-1,6,6-trimethyl-, 1(2H)-Naphthalenone,3,4-dihydro-5,7-dimethyl-, and Ethanone 1-phenyl-2-(4,5-diphenyl-2-imidazolylthio). These are non-mutagenic, with high gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain-barrier permeants which are excellent candidates for further research.

Virtual Screening of Ligands

The ligands were docked against two protein targets, acetylcholinesterase and β-secretase. Acetylcholinesterase is an enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine into reusable derivatives through hydrolysis. This action of enzyme is necessary to recycle the acetylcholine in normal conditions after transmission of signal. However, in an Alzheimer’s patient, the synapses of the neurons are blocked by plaques which cause delay or loss of signalling. The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase can improve signalling by decreasing the rate of hydrolysis of acetylcholine to choline moiety.

Beta-Secretase is known to be responsible for the cleaving of beta-amyloid protein to beta-amyloid plaques, which are the hallmark of Alzheimer’s and dementia. The inhibition of the action of beta-secretase can ensure that the amyloid precursor protein is not cut into insoluble beta-amyloid [11].

The results for acetylcholinesterase were between − 3.9 and − 11.4, which are considered good, and are represented in Table 1. The results for beta-secretase were between − 3.3 and − 9.7 kcal/mol and are represented in Table 2. The results for both the proteins indicated that these compounds are excellent candidates for further research. Only compounds which scored above − 8 kcal/mol were considered best ligands among the 36 docked compounds.

Table 1.

Docking images of best ligands against acetylcholinesterase

Table 2.

Docking images of best ligands against beta-secretase

Among these, the best binding affinity was shown by Ethanone 1-phenyl-2-(4,5-diphenyl-2-imidazolylthio)- with a score of − 11.4 kcal/mol. Ethanone 1-phenyl-2-(4,5-diphenyl-2-imidazolylthio)- is a 4,5-diarylimidazole-2-thione derivative, which is a subclass of thione derivatives that are known for various biological activities[12].

Thiazolo[3.2-a]benzimidazol-3(2H)-one,2-(4-acetoxybenzylideno)- also showed a good binding affinity of − 10.6 kcal/mol with acetylcholinesterase. It shows excellent pharmacokinetic properties. It is a Thiazolo[3,2-a]benzimidazole derivative, which is known to be biologically active[13].

Phenanthro[1,2-b]furan-10,11-dione,6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-1,6,6-trimethyl- is another compound which showed good binding scores of − 9.9 kcal/mol. It is a medically valuable compound because of its various biological actions[14–16]. 2-Azetidinone,3-(1,1-dimethylethyl)-1,4-diphenyl-,trans- also shows good binding score of − 8.5 kcal/mol. 1(2H)-Naphthalenone,3,4-dihydro-5,7-dimethyl- is a tetralone derivative and has the binding affinity of − 8.3 kcal/mol. Tetralone derivatives are also known for its action on serotonin and dopamine[17].

These ligands also showed good binding scores for beta-secretase. Among the docked ligands, Phenanthro[1,2-b]furan-10,11-dione,6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-1,6,6-trimethyl- showed the highest docking score of − 9.7 kcal/mol. Thiazolo[3,2-a]benzimidazol-3(2H)-one,2-(4-acetoxybenzylideno)- showed a score of − 9 kcal/mol. Ethanone,1-phenyl-2-(4,5-diphenyl-2-imidazolylthio)- showed a score of − 8.6 kcal/mol.

Conclusion

The docking results showed that the potential compounds of Borassus flabellifer may be potential compounds for further studies against Alzheimer’s disease. Among the 36 ligands which were docked against beta-secretase and acetylcholinesterase, the best results against both proteins were showed by 3 compounds. Binding scores above − 8 kcal/mol were considered top ligands. Five compounds showed best interaction with acetylcholinesterase and 3 compounds showed best interaction with β-secretase. These compounds also showed excellent pharmacokinetic properties. The potential use of these compounds against both acetylcholinesterase and beta-secretase could be highly valuable in treatment. Further studies could show valuable insight to the effectiveness of these compounds under in vivo. Studies could also indicate the synergistic action of the natural compounds against Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to B.S. Abdur Rahman Institute of Science & Technology, Chennai for providing research facilities in School of Life Sciences.

Author Contribution

Jason Abraham: investigation, conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, reviewing and editing, formal analysis and artwork. H. Noorul Samsoon Maharifa: methodology, investigation, conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, resources, reviewing and editing, visualization, formal analysis and artwork. S. Hemalatha: conceptualization, resources, supervision, data curation, validation, and project administration.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Department of Science and Technology DST/SATYAM/COVID-19/2020/213 (G).

Data Availability

Data will be available on request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

All authors read and approved the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hardy J. A hundred years of Alzheimer’s disease research. Neuron. 2006;52:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei P, Ayton S, Bush AI. The essential elements of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2021;296:100105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV120.008207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo T, Zhang D, Zeng Y, Huang TY, Xu H, Zhao Y. Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2020;15:1–37. doi: 10.1186/s13024-020-00391-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesulam MM, Guillozet A, Shaw P, Levey A, Duysen EG, Lockridge O. Acetylcholinesterase knockouts establish central cholinergic pathways and can use butyrylcholinesterase to hydrolyze acetylcholine. Neuroscience. 2002;110:627–639. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00613-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dos Santos TC, Gomes TM, Pinto BAS, Camara AL, De Andrade Paes AM. Naturally occurring acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and their potential use for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2018;9:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta MK, Vadde R. In silico identification of natural product inhibitors for γ-secretase activating protein, a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2019;120:10323–10336. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dallakyan S, Olson AJ. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2015;1263:243–250. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2269-7_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D Studio. (2008). Discovery studio life science modeling and simulations, Researchgate.Net. 1–8

- 9.Kareti SR, Pharm SM. In silico molecular docking analysis of potential anti-Alzheimer’s compounds present in chloroform extract of Carissa carandas leaf using gas chromatography MS/MS. Current Therapeutic Research, Clinical and Experimental. 2020;93:100615. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2020.100615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipinski CA. Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies. 2004;1:337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basha FH, Waseem M, Srinivasan H. Cellular and molecular mechanism in neurodegeneration: Possible role of neuroprotectants. Cell Biochemistry and Function. 2021;39(5):613–622. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohan, R., Chou, Y. L., Bihovsky, R., Lumma, W. C. Jr, Erhardt, P. W., & Shaw, K. J. (1991). Synthesis and biological activity of angiotensin II analogues containing a Val-His replacement, Val psi[CH(CONH2)NH]His. J Med Chem, 34(1991), 2402–2410. 10.1021/jm00112a014 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Alkhaldi AAM, Al-Sanea MM, Nocentini A, Eldehna WM, Elsayed ZM, Bonardi A, Abo-Ashour MF, El-Damasy AK, Abdel-Maksoud MS, Al-Warhi T, Gratteri P, Abdel-Aziz HA, Supuran CT, El-Haggar R. 3-Methylthiazolo[3,2-a]benzimidazole-benzenesulfonamide conjugates as novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitors endowed with anticancer activity: Design, synthesis, biological and molecular modeling studies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2020;207:112745. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subedi L, Gaire BP. Tanshinone IIA: A phytochemical as a promising drug candidate for neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacological Research. 2021;169:105661. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan Z, Chen J, Li X, Dong N. Tanshinone IIA induces ferroptosis in gastric cancer cells through p53-mediated SLC7A11 down-regulation. Bioscience Reports. 2020;40:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BSR20201807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo, D., Li, X., Hou, Y., Hou, Y., Luan, J., Weng, J., Zhan, J., & Lin, D. (2021). Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate promotes spinal cord injury repair by inhibiting blood spinal cord barrier disruption in vitro and in vivo. Drug Dev Res. 10.1002/ddr.21898 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Ceylan M, Kocyigit UM, Usta NC, Gürbüzlü B, Temel Y, Alwasel SH, Gülçin İ. Synthesis, carbonic anhydrase I and II isoenzymes inhibition properties, and antibacterial activities of novel tetralone-based 1,4-benzothiazepine derivatives. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology. 2017;31:1–11. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Not applicable.