Abstract

Humanitarian social enterprises (HSEs) are facing mounting pressure to incorporate social innovation into their practice. This study thus identifies how HSEs leverage organizational capabilities toward developing social innovation. Specifically, it considers how resource scarcity and operating circumstances affect the capabilities used by HSEs for developing social innovation, using a longitudinal case study approach with qualitative data from 12 hunger-relief HSEs operating in the United States. Based on 59 interviews with 31 managers and directors and related documents, several propositions are posited. The findings suggest that resource availability (i.e., scarcity vs. abundance) leads some HSEs to focus on developing social innovation using their collaborative capabilities, while others leverage their absorptive capacity. Further, HSEs adjust their approach to developing social innovation based on whether they are operating in ordinary circumstances (i.e., before the COVID pandemic) or extraordinary ones (i.e., during the COVID pandemic). Interestingly, the findings suggest that the organizational capabilities used by HSEs are adjusted as these enterprises become more familiar with extraordinary operating circumstances. For example, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, resource-scarce HSEs focused on parallel bricolage to develop social innovation. Subsequently, they focused on selective bricolage. The findings offer novel insights by relating the social innovation of social enterprises to crisis management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10551-021-05014-9.

Keywords: Resource scarcity, Social innovation, Social enterprise, Bricolage, COVID-19 pandemic

Introduction

Philabundance is a hunger-relief HSE located in the city of Chester, Pennsylvania, where the last supermarket closed in 2001. Faced with rising demand for food from beneficiaries and pressure from stakeholders, Philabundance joined forces with several local partners to fight off food scarcity in the city by opening and operating a nonprofit grocery store. The innovative project was a complex undertaking, mainly because the business model was untested. It was also a collaborative effort among many organizations. The result was the development of a 16,000-square-foot grocery store, allowing many families to put healthy foods on their tables.

Humanitarian social enterprises (HSEs) are a unique form of social enterprises that operate as non-profit organizations and depend on donations in terms of revenue and volunteers in terms of human resources (Seelos & Mair, 2005; Van Wassenhove, 2006). The example of Philabundance demonstrates that HSEs face mounting pressures to innovate continually. In the recent past, the number of people in need of services provided by HSEs has almost doubled globally, and the cost of providing those services has almost tripled (OCHA, 2020). Expectations from donors, government agencies, and other providers incentivize HSEs to demonstrate continual improvement and novel ways to address their causes (Dhanani & Connolly, 2015). Social innovations—new social practices that aim to develop and implement novel ideas to meet unsatisfied social needs—are beneficial to HSEs. Through social innovations, HSEs manifest their willingness and proactive stance for meeting stakeholder expectations (European Commission, 2013; Lawson-Lartego & Mathiassen, 2020).

Organizational capabilities that can enable HSEs to innovate are essential for innovation development (Collis, 1994; Kusunoki et al., 1998). However, leveraging organizational capabilities that enable developing social innovations by HSEs can be affected by the resource scarcity level (Austin et al., 2006; Farooq, 2017; Laforet & Tann, 2006). HSEs’ dependency on resources provided by others (i.e., donations and volunteers) make them highly reliant on the resources available in their operating environment. Resource scarcity—the lack of the critical resources required by a firm operating in the environment—is important to assess the capabilities that enable the development of social innovation by HSEs (Dess & Beard, 1984).

How resource scarcity in the operating environment affects the development of innovation is unclear. Some studies suggest that an abundance of resources offers more opportunities to innovate (Meyer & Leitner, 2018). While resource scarcity restricts investment beyond necessities, resource abundance lowers the effort necessary for survival, thus potentially allowing for the development of innovations (Goll & Rasheed, 1997, p. 45; Kach et al., 2016). Other studies suggest that resource scarcity can prompt innovations (Bhatt et al., 2019; Meyer & Leitner, 2018). Specifically, while the lack of resources disincentivizes innovation (Cunha et al., 2014; Spithoven et al., 2013; Stokes, 2014), organizations can adjust the capabilities used to develop innovations to their environment.

The above argument creates an incipient framework for investigating the capabilities that lead to social innovation by HSEs. However, the literature fails to consider the operating environment or the use of particular organizational capabilities. Resource scarcity or abundance can be caused by the unavailability of resources in ordinary times (i.e., the ordinary operating environment for HSEs), characterized by relatively stable supply and demand. However, resource scarcity can also be caused by extraordinary circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a drastic increase in demand and a drastic decrease in supply. Theoretically, while both settings can affect the selection of organizational capabilities for developing innovation, their consequences differ. Such distinctions are missing from the literature. We offer further explanation about the difference between ordinary and extraordinary environments in the next section and in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions

| Term | Definition | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Humanitarian social enterprise | A unique form of social enterprises that operate as non-profit organizations and depend on donations and volunteers for revenue | Seelos and Mair (2005), Van Wassenhove (2006) |

| Social innovation | New social practices that aim to develop and implement novel ideas that are motivated by a goal of meeting an unsatisfied social need | Pol and Ville (2009), Phillips et al. (2015), European Commission (2013) |

| Resource scarcity | The lack of critical resources needed by a firm operating within an environment | Dess and Beard (1984) |

| Absorptive capacity | An organization’s ability to identify, assimilate, transform, and use external knowledge | Azadegan (2011), Cohen and Levinthal (1990) |

| Collaborative capabilities | An organization’s ability to facilitate combining operational resources offered by other organizations with internal operational resources in developing solutions | Davis and Friske (2013), Yao et al. (2019) |

| Bricolage | An organization’s ability to “make do" by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities toward developing new solutions | Baker and Nelson (2005) |

| Parallel bricolage | Form of bricolage that is applied using a broad range of resources and across many domains of activity | Rönkkö et al. (2014) |

| Selective bricolage | Form of bricolage that is applied more judiciously and in one or a few domains of activity | Senyard et al. (2014) |

| Ordinary operating environment for HSEs | A situation that HSEs face progressively over time, characterized by predictable levels of resource scarcity rather than due to a single, distinctive incident | Van Wassenhove (2006) |

| Extraordinary operating environment for HSEs | A situation that HSEs face due to a single, distinctive incident characterized by (i) sudden changes in the environment and (ii) alteration of the availability and unpredictability of resources such as scarcity of resources | Van Wassenhove (2006) |

As noted above, the innovation itself is important, but so are the capabilities that enable firms to innovate (Collis, 1994; Kusunoki et al., 1998). Organizational capabilities are routines or manifestations of observable corporate structures and processes that determine how firms transform inputs into outputs (Collis, 1994). However, as we explain later, selecting which organizational capability to use in developing innovation is difficult because there are inherent trade-offs in terms of the resources and effort invested in them (McGahan et al., 2021). We thus try to determine the relationship between the resource scarcity and organizational capabilities of HSEs in ordinary and extraordinary operating environments for developing social innovations. While it is still unclear whether resource scarcity acts as a hindrance or enabler in the innovation context (Austin et al., 2006; Farooq, 2017; Kach et al., 2016), our research helps investigate which organizational capabilities are best used based on the level of resource scarcity.

We use a case study approach with interviews from 31 managers and directors (59 interviews) along with related documents from 12 HSEs operating in the US. The interviews were conducted across multiple periods to capture the effects of ordinary and extraordinary operating environments. The context is hunger relief. Until April 2020, US hunger-relief HSEs were grappling with challenges associated with the chronic hunger issue in the country under an operating environment that comprises notable resource scarcity. The dire circumstances surrounding the hunger issue in the US cannot be overemphasized. The effect of malnutrition on a large percentage of children and adults is severely detrimental for society at large (Dickinson, 2019). Since April 2020, HSEs have also faced the challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which created an extraordinary operating environment that augmented resource scarcity (Laborde et al., 2020).

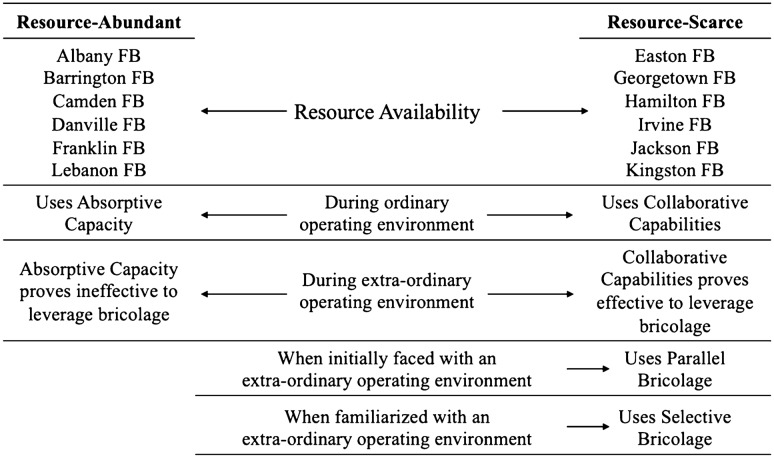

We find that both resource scarcity and resource abundance have a notable influence on what capabilities HSEs use for developing social innovation. Those facing resource scarcity rely on their collaborative capabilities (CC)—an organization’s ability to combine the operational resources offered by other organizations with internal operational resources (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Davis & Friske, 2013). However, those operating in resource-abundant settings rely on their absorptive capacity (AC)—an organization’s ability to identify, assimilate, transform, and use external knowledge (Azadegan, 2011; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). The advent of the COVID-19 pandemic (extraordinary environment) led resource-scarce HSEs to readjust and leverage bricolage in developing social innovation—an organization’s ability to “make do" by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities toward developing new solutions (Baker & Nelson, 2005). However, as the resource-scarce HSEs become familiar with this extraordinary operating environment, they shifted from parallel to selective bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005; Rönkkö et al., 2014).

This study significantly contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it contributes to resource scarcity and its effects on innovation through social enterprises by highlighting how operating environment that underlies both resource scarcity and resource abundance leads to the use of different capabilities for social innovation. Second, the study informs the research on humanitarian relief by offering deeper insights and highlighting the varied effects of resource scarcity and resource abundance. Finally, it contributes to the literature on crisis management by highlighting the role played by extraordinary contexts, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and how they lead to changes in the type of organizational capabilities (e.g., collaborative capability, absorptive capacity, and different types of bricolage) used for social innovation. Practically, managers in charge of HSEs should select the right capability in developing social innovations.

Literature Review

Resource Scarcity and Its Effect on Innovation Development

We define resource scarcity as the lack of critical resources required by a firm in its operating environment (Dess & Beard, 1984). Table 1 shows the definitions used in this study. Some studies view resource scarcity as an impediment for an organization to develop innovation (Bhatt et al., 2019; Kach et al., 2016; Meyer & Leitner, 2018). Resource scarce environments can limit the breadth of organizational innovation efforts because lack of resources can diminish the number of options and choices for experimentation and trial (Farooq, 2017). By contrast, enterprises operating in environments with adequate access to financial resources carry more innovative activities (Keizer et al., 2002). The social entrepreneurship literature also highlights the negative impact of resource scarcity on the innovation activities of social enterprises (e.g., Bhatt et al., 2019). For example, Austin et al. (2006) focus on how restrictions on profit distribution limit non-profit social enterprises from accessing capital markets. Laforet and Tann (2006) report that limited financial resources critically obstruct the innovation activities of social enterprises. Given that the focus has been on the outcome and not the process of innovation development, the literature does not consider which organizational capabilities are best suited for innovation development in resource-scarce or -abundant settings.

Others suggest that resource scarcity can actually help with innovativeness by pressing an organization to think creatively (Kach et al., 2016; Mehta & Zhu, 2015). Katila and Shane (2005) find that resource scarcity is positively related to innovation, particularly in competitive markets, as resource-scarce environments foster organizations’ innovativeness by leading them toward techniques that help reduce waste. Spithoven et al. (2013) show how the lack of resources acts as a motivation for innovativeness. However, Cunha et al. (2014) explain how scarcity in different forms can affect product development. Stokes (2014) suggest that creative thinking is often initiated by necessity. Rosenzweig and Mazursky (2014) find that constraints have a positive association with innovativeness in terms of technological output.

Extant studies have also suggested that resource scarcity leads to social innovation. For instance, Gundry et al. (2011) explain how the lack of resources leads social entrepreneurs to creatively innovate through scaling and replication. Further, Hoegl et al. (2008) report how resource constraints support creativity among social enterprises. However, Van Burg et al. (2012) find that environmental resource constraints have a positive effect on opportunity identification among social enterprises. In summary, while resource scarcity can be a strong predictor of how organizations develop innovation, its effects are debated, and the literature does not consider the settings behind resource scarcity. This literature stream also comes short in studying which organizational capabilities are best suited for innovation development.

For social enterprises, resource scarcity creates challenges even during ordinary operating environments—defined as a situation that HSEs face progressively over time, characterized by predictable levels of resource scarcity rather than due to a single, distinctive incident (Van Wassenhove, 2006). For instance, for US hunger-relief HSEs, food insecurity and food poverty have been steadily on the rise during the past decades. Meanwhile, food and funds donations have been in short supply (Mohan et al., 2013). Nevertheless, how resource scarcity affects social enterprises is not uniform. For example, non-profit organizations with more convenient locations and higher service quality often receive larger donations (Nagurney & Dutta, 2019), possibly because some donors are more interested in helping certain regions over others (Çelik et al., 2012). Indeed, donation inequality has been a prevalent concern in fundraising for social causes (Chakraborty & Ewens, 2018). For instance, some hunger-relief HSEs operate in food deserts (i.e., areas with limited access to affordable and nutritious food) (Blanchard & Matthews, 2007), which makes the collection of food and financial donations more difficult. By contrast, other HSEs may have better access to resources because they operate in areas where access to donations is easier.

The issue of resource scarcity took a new turn at the beginning of March 2020. Shortly after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the US authorities issued stay-at-home directives and required the closure of non-essential businesses. COVID-19 is an example of an extraordinary operating environment for HSEs, defined as a situation that HSEs face due to a single, distinctive incident characterized by (i) sudden changes in the environment and (ii) alteration of the availability and unpredictability of resources such as scarcity of resources (Van Wassenhove, 2006). Dyring COVID-19, the country’s unemployment rate doubled (Sherman, 2020). Consequently, the number of people and organizations requiring assistance increased, placing tremendous pressure on social enterprises. Simultaneously, COVID-19 also led to a significant reduction in the external resources available to social enterprises. For example, as of the end of April, the US and other developed countries had donated only 13% of what humanitarian organizations required for the entire year’s operation (HRW, 2020). To make matters worse, movement restrictions not only made it more difficult for social enterprises to reach the needy but also led to a significant drop in volunteers because of health concerns (Tierney & Mahtani, 2020).

The above shows how resource scarcity can differ between ordinary and extraordinary operating environments. Arguably, this requires identifying different organizational capabilities of HSEs for developing social innovation due to the opportunity (or lack thereof) to reflect, strategize and respond effectively caused by time constraints. In an ordinary operating environment, such as hunger, poverty, and famine, HSEs have more time to reflect, strategize and decide on how to respond (Van Wassenhove, 2006). Indeed, the prolonged nature of such events may suggest that different types of innovation (and different types of capabilities—as related to our paper) may need to be practiced. On the other hand, as we note above in defining extraordinary operating environments, the development of innovation and the practice of capabilities for innovation has to occur with the realization that there are more time constraints. There is limited time to reflect, strategize and decide on how to respond and practice capabilities.

Humanitarian Social Enterprises and Social Innovation

This study focuses on HSEs as a unique form of social enterprise that operates as non-profit organizations and is dependent on donations for revenue and volunteers for human resources. Generally, social enterprises are hybrid organizations that combine multiple institutional logics [i.e., social logic (focusing on social needs) and market logic (focus on profit generation)] (Bull & Ridley-Duff, 2019; Hudon et al., 2020). Social enterprises and HSEs focus on finding creative and self-sustainable solutions to deal with modern-day social challenges (Bull & Ridley-Duff, 2019). However, while the mission of social enterprises is to maximize social and environmental benefits alongside profit, the mission for HSEs centers on social well-being in a non-profit context. Additionally, while social enterprises are structured as taxable commercial businesses with a business model, HSEs are structured as non-profit entities (501c3 in the USA) requiring financial transparency (Kerlin, 2006). Table A-1 in the Online Supplement shows the key similarities and differences between social enterprises and HSEs.

Literature on crisis management has also highlighted the importance of managing such complicated and unique situations by HSEs (Starr & Van Wassenhove, 2014; Van Wassenhove, 2006). Notable here is the work of Sodhi and Tang (2014) that suggests how social enterprises are critical for developing humanitarian relief and economic recovery efforts during crises. Similarly, Starr and Van Wassenhove (2014) suggest how humanitarian efforts are imperative in reducing the severity of crisis events. Nevertheless, there is limited understanding of how the organizational capabilities of HSE are useful for developing innovations during crises.

Practitioners and the academic literature suggest that innovation is often side-stepped by HSEs (Betts & Bloom, 2014). Social innovation refers to developing and implementing novel ideas motivated by an unsatisfied social need (European Commission, 2013; Phillips et al., 2015; Pol & Ville, 2009). As previously noted, the shortcomings in innovation and the capabilities that help HSEs innovate may be attributed to environmental resource scarcity (Austin et al., 2006; Bhatt & Altinay, 2013). Nevertheless, the topic has received limited attention in the literature.

As discussed, the organizational capabilities that enable the development of social innovations are of key importance (Collis, 1994; Kusunoki et al., 1998). For instance, some studies highlight the role of CC (e.g., Lashitew et al., 2020; Manning & Roessler, 2014) as an organization’s ability to combine operational resources offered by other organizations with internal operational resources in developing solutions (Davis & Friske, 2013; Yao et al., 2019). Previous research shows that CCs are related to organizational sustainability commitment and new product development efforts (Luzzini et al., 2015; Vachon & Klassen, 2008). Others highlight the importance of social capital (Bhatt & Altinay, 2013) and learning orientation (L'Hermitte et al., 2017). A few studies focus on the importance of learning from the outside (Huarng & Yu, 2011; Hope et al., 2019), often referred to as AC in the organizational learning and innovation literature. AC is defined as the ability to identify, transform, and use external knowledge to develop social innovation (Azadegan & Dooley, 2010; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

Another notable capability is bricolage—“making do" by applying combinations of the resources at hand to new problems and opportunities (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Among the studies using bricolage is that of Lashitew et al. (2020), who focus on the significant role of native capabilities (e.g., including locally available knowledge, resources, and networks) when applying bricolage to poverty alleviation efforts. Bricolage can take different forms (Baker & Nelson, 2005). For example, parallel bricolage involves undertaking efforts in multiple domains; however, material bricolage involves only limited ones (Rönkkö et al., 2014). While most extant research has looked at bricolage, CC, and AC in commercial settings, this evidence may be transferrable to our research context. This is because the external environment caused by humanitarian disasters could lead to similar demand to leverage CC, AC, and bricolage by HSEs.

A note of clarification is necessary here. Bricolage and AC differ because bricolage is innovating with what is readily available, while AC uses external knowledge.1 Further, bricolage and CC differ because bricolage may or may not leverage the use of external operational resources (Busch & Barkema, 2021). Specifically, bricolage is focused on developing innovations with limited available resources (often internal) (Senyard et al., 2014), whereas CC or AC do not have such a discriminating perspective. Nevertheless, the literature on social innovation falls short in differentiating the effects of these different forms of organizational capabilities in developing innovation.

Methods

A longitudinal case study approach, defined as “studying the same phenomenon at two or more different points of time” (Yin, 2018, p. 51) was chosen. Specifically, our research question observes how innovation capabilities differ in alternative circumstances (Yin, 2018), reflected by the time intervals for the longitudinal case study. Specifically, following the before and after logic (Yin, 2018), the time intervals are either ordinary operating circumstances (normal times, before COVID-19 pandemic) and extraordinary ones (at the onset and after more familiarity with the COVID-19 pandemic).

Additionally, considering that research on how HSEs develop innovation is nascent, an exploratory approach using multiple cases is used. The unit of analysis is the organization developing social innovation. We purposefully chose hunger-relief HSEs, given that hunger is considered a primary objective among United Nations Sustainability Development Goals. Hunger-relief HSEs include those that collect, organize, and deliver food to help alleviate the suffering that comes from the lack of food and inadequate nutrition (Ataseven et al., 2018). Further, hunger is a profoundly alarming national concern in the US. In 2019, 48.1 million Americans, representing 10.5% of US households, were classified as food insecure (USDA, 2020). Finally, the literature provides evidence for hunger-relief HSEs to develop innovation (e.g., Ataseven et al., 2018; Fisher, 2017; Mohan et al., 2013).

Case Selection

The focus of the research methodology was to collect empirical evidence on how hunger-relief HSEs leverage their capabilities for developing social innovation under varied operating environments and resource scarcity. We started the data collection by contacting a national organization that forms a network of more than 200 hunger-relief HSEs. We obtained secondary data from the national organization, which provided us with the names of HSEs that were operating in resource-scarce and resource-abundant settings. Following Bose (2015), resource availability in the served area (e.g., scarce and abundant) was defined based on metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). According to the US Census Bureau, an area is defined as metropolitan if a minimum of one urban core area has a population of at least 50,000. MSAs directly affect the level of resource availability (scarce or abundant) in the served areas, thereby affecting the availability of financial and in-kind resources for hunger-relief HSEs. First, hunger-relief HSEs that serve MSAs with a higher number of beneficiaries are typically located in densely populated areas, thus having more opportunities to attract financial donations and develop capabilities due to the larger number of manufacturers and wholesalers in the area (Bettencourt et al., 2007). MSAs with low populations offer evidence of the lack of resource availability for hunger-relief HSEs. Second, hunger-relief HSEs located in low populated MSAs—labeled as “food deserts”—encounter more severe competition for financial and in-kind donations. These hunger-relief HSEs need to make significant efforts for collecting financial and in-kind donations. The US Census has identified 383 MSAs, with populations ranging from 20 million (New York-Newark-Jersey City MSA) to 54,000 people (Carson City, Nevada MSA). We calculated the mean and median scores for all MSAs; HSEs that were above average are considered “resource-abundant” and those below average “resource-scarce.” The national organization’s executives confirmed the appropriateness of the measure for resource scarcity and the classifications of hunger-relief HSEs chosen for analysis. We subsequently triangulated the MSA measure with other forms of evidence provided by respondents, HSEs’ websites, and documentation. We found no evidence that indicated that other financial sources led to a different categorization of the selected resource-scarce HSEs (e.g., large financial donors or sponsors). The final sample comprised 12 HSEs chosen based on the resource availability level (scarce or abundant) in the served areas; six of these were classified as resource-scarce and six as resource-abundant. This categorization provided a foundation for positing propositions regarding social innovation development.

Data Collection

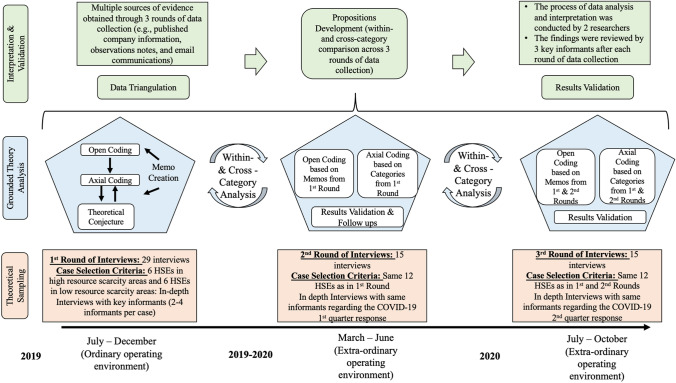

Unlike deductive research, which is confirmatory and requires a specific sample size, an exploratory case study relies on theoretical sampling, the findings guiding the data collection and sample size (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2007; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Figure 1 presents an overview of the data collection process. The data were collected in three rounds: the first round included 29 interviews (during ordinary operating environments, collected between July and December of 2019), the second round 15 interviews (at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, collected between March and June of 2020), and the third round 15 interviews (over the COVID-19 pandemic, collected between July and October of 2020).

Fig. 1.

Methodological steps for case selection, analysis, triangulation, and propositions

The propositions related to social innovation rely primarily on the descriptive data from in-depth interviews with key informants, observations of the activities in key informants’ operating facilities and warehouses, documents provided by key informants, and material gathered from official HSEs’ websites (see Online Appendix for the data sources). The findings are based on in-depth interviews with 31 key informants (59 interviews because some were interviewed more than once), including CEOs, executive directors, and chief operating officers. The key informants were influential decision-makers responsible for making major corporate decisions and managing operations. Table 2 presents each key informant’s profile, including their pseudonyms, titles, and background information. Grounded theory analysis relies on 397 pages of single-spaced text transcriptions from the in-depth interviews, an additional 55 pages of recorded researcher observations, and information gathered from websites—all of which were systematically coded and analyzed.

Table 2.

Profiles of key informants

| Hunger relief organization | Resource scarcity of the area | Organizational size | Informant(s) | Informant title | Informant experience (years) | Interview length (min) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area serveda | Population servedb | 1st round | 2nd round | 3rd round | ||||||

| 1 | Albany HRO | Low | VL | VL | Jacob | Chief Operating Officer | > 20 | 30 | 65 | 45 |

| James | President & CEO | > 20 | 70 | |||||||

| Linda | VP of Agency Relations | 10–15 | 35 | |||||||

| 2 | Barrington HRO | Low | VL | VL | John | Executive Director | > 20 | 130 | 80 | |

| Emma | Director of Development | > 20 | 65 | 35 | 65 | |||||

| Olivia | Assistant Director of Procurement | 0–5 | 25 | 25 | ||||||

| 3 | Camden HRO | Low | L | M | Jessica | President & CEO | > 20 | 60 | 35 | |

| Maria | Chief Operating Officer | > 20 | 55 | 60 | ||||||

| Kevin | Chief Communications Officer | 10–15 | 35 | 35 | ||||||

| 4 | Danville HRO | Low | M | L | William | Director of Strategic Initiative | 15–20 | 40 | 45 | |

| Mary | Chief Operating Officer | 15–20 | 60 | 60 | ||||||

| Jessica | President & CEO | > 20 | 40 | 35 | ||||||

| 5 | Easton HRO | High | VS | VS | Nancy | Executive Director | > 20 | 70 | 70 | |

| Phillip | Chief Operating Officer | > 20 | 45 | 55 | ||||||

| 6 | Franklin HRO | Low | L | L | Lisa | President & CEO | 15–20 | 70 | ||

| Matthew | Chief Operating Officer | > 20 | ||||||||

| Karen | Director of Partnership & Programs | 15–20 | 60 | 70 | 60 | |||||

| Alice | Chief Communications Officer | 10–15 | 55 | |||||||

| 7 | Georgetown HRO | High | M | S | Miranda | Senior Manager of Partnerships | 10–15 | 55 | 60 | |

| Luke | President & CEO | > 20 | 65 | 65 | ||||||

| 8 | Hamilton HRO | High | S | S | Donna | President & CEO | > 20 | 70 | 75 | 35 |

| Emily | Director of Finance | 10–15 | 35 | |||||||

| 9 | Irvine HRO | High | L | S | Kevin | President & CEO | > 20 | 70 | 70 | |

| Brian | Director of Operations | > 20 | 40 | |||||||

| 10 | Jackson HRO | High | M | M | Alex | President & CEO | > 20 | 45 | ||

| Chris | Chief Operating Officer | > 20 | 45 | 35 | ||||||

| Ronald | Director of Development | 10–15 | 65 | |||||||

| 11 | Kingston HRO | High | L | M | Max | President & CEO | > 20 | 60 | 45 | |

| Samantha | Director of Relationship Management | > 20 | 60 | 35 | ||||||

| Jeffery | VP of Community Relations | 10–15 | 55 | 55 | ||||||

| 12 | Lebanon HRO | Low | M | M | Brent | CEO | > 20 | 40 | 65 | |

| David | Director of Procurement | 10–15 | 55 | 75 | ||||||

| Stephanie | Director of Development | 5–10 | 60 | |||||||

| Total Number of Interviews | 29 | 15 | 15 | |||||||

Notes All key informants are key managers in their HSEs and have decision-making power. The names of informants and HSEs are pseudonyms

aArea served (square miles) very small (VS)—< 500, small (S)—1000, medium (M)—1000–2000, large (L)—2000–5000, very large (VL)—> 5000

bPopulation served—< 50,000, S—50,000–500,000, M—500,000–2,000,000, L—2,000,000–5,000,000, VL—> 5,000,000

The First Round of Data Collection

The first data collection round included initial interviews with two HSEs (one resource-scarce and one resource-abundant) focused on innovation in the ordinary operating environment. Based on the obtained information, we compared the data, and the remaining questions related to the categories, properties, and unexplored innovation relationships suggested which HSEs to sample next (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Subsequently, we conducted additional interviews and analyzed them as they were transcribed. In the successive interviews, we used more refined questions based on the emergent findings from the analyses. This mix of theoretical sampling and the constant comparison technique between interviews allowed for the triangulation of the findings (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2007). Compared to statistical sampling, theoretical sampling emphasizes the increase in variation because maximizing variation allows the most in-depth examination of emerging conceptual categories, properties, and relationships. We continued to interview additional subjects until theoretical saturation was reached; the inclusion of additional information did not generate any novel information about a conceptual category (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This occurred after 29 interviews with 12 HSEs (six organizations for each resource-scarce setting). The first round of interviews in the ordinary operating environment was conducted between July and December of 2019.

A semi-structured interview protocol was created to collect information from the in-depth interviews, which included open-ended questions to encourage the key informant to elaborate on focal topics and minimize researcher influence (see the Online Appendix for the first round’s interview protocol questions). We identified the most qualified informants (Yin, 2018) using the following approach. First, we identify HSEs in different areas based on resource availability (e.g., scarce and abundant) based on their websites. The national hunger-relief organization highlighted the fact that innovation development is part of the strategic-level decisions made by executives and directors in all HSEs. Therefore, we contacted the CEOs or executive directors, who pointed us to the most qualified informants.

During the interviews, the key informants directed the conversations while the interviewing researcher ensured the key informant discussed the focal topics (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2007). The principal investigator conducted most interviews on-site. Site visits permitted researchers to directly interact with key informants in their natural work environments, providing rich information through interactions, discussions, and observation. Most interviews were one-on-one with the principal investigator, although one interview was conducted in a small group setting. The interviews averaged 55 min, ranging from 25 min to over 2 h in length (see Table 2). All interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed.

The Second Round of Data Collection

At the beginning of March 2020, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic. In the following weeks, many HSEs could not rely on external sources and tried to become more self-sufficient by using combinations of the resources available at hand to the new problems and opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the second round of data collection investigated whether the addition of an acute crisis changed how hunger relief HSEs leveraged their capabilities. The second round of interviews was conducted between March and June of 2020 using a semi-structured interview protocol (see the Online Appendix for the second round’s interview protocol questions). All interviews were conducted by phone due to the COVID-19 pandemic social distancing guidelines. Otherwise, the interview process was the same as in the first round. We also started analyzing the data immediately after the first interviews but identified no new themes for any of the coding categories after 15 interviews. This led us to believe that we reached saturation.

The Third Round of Data Collection

Follow-up conversations with the interviewees suggested that after a few months, the initial chaos and confusion about the crisis had subsided significantly and that hunger-relief HSEs were better organized. The third round of interviews included questions specific to the behaviors over the pandemic and was conducted between July and October of 2020. A semi-structured interview protocol was used (see the Online Appendix for the third round interview protocol questions), and the interviewing process was similar to the first and second rounds. All interviews were conducted by video conference due to the COVID-19 pandemic social distancing guidelines. We started by analyzing the data immediately after the first interviews were collected. After 15 interviews, we found no new themes, meaning we had reached saturation (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Data Analysis

For the analysis, the interview transcripts, researcher observations, and published company information were imported into NVivo 11. Open and axial coding was used to systematically code the descriptive data to determine important categories and themes (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

After the first five initial interviews, open coding was initiated to identify and label essential categories. The labels were closely matched to the key informant’s actual words whenever possible (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). During open coding, multiple concepts that described aspects of the same social innovation phenomenon were grouped to form higher-order categories. For example, open coding led to the identification of donors and fundraising, both of which describe HSEs’ funding resources.

In addition to open coding, we axially coded the emerging categories to better understand the depth and types of relationships among categories (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2007). Axial coding revealed the connections between categories and subcategories, forming the structure of the emerging propositions and corresponding framework. Finally, the interpretation stage was validated during multiple meetings with the three researchers to similarly discuss the coding and its interpretation as in the previous stages.

To evaluate the validity and quality of the research design, we addressed reliability, construct validity, and external validity (Lashitew et al., 2020; Yin, 2018). First, we used an interview protocol to help increase reliability; we applied a funneling approach to interviewing so that the general questions were asked before the specific ones. This approach helped avoid the responses to specific questions biasing the answers to the general ones (Charmaz & Belgrave, 2007). The initial protocol specified broad themes related to the innovation environment, as well as the relationships with suppliers, donors, and customers. We subsequently started by looking for differences among HSEs. However, as the interviews progressed, we began asking more specific questions related to resource scarcity and innovation development. Data source triangulation ensured that the information obtained from multiple sources was aligned (Yin, 2018), and was accomplished by two researchers cross-checking the evidence collected from interviews, researcher observations, published company information, annual reports, and email correspondence. We ensured intercoder reliability by having two coders categorize the content from the informants’ interviews, emails, published company information, and observation notes (Yin, 2018). Finally, we grounded the emergent observations from our findings with the theoretical elements from the literature on absorptive capacity (Azadegan & Dooley, 2010; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), collaborative capabilities (Davis & Friske, 2013), and bricolage (Baker & Nelson, 2005) to address external validity.

Results

Overall Findings

Operating context plays a key role in how HSEs approach social innovation. In an ordinary operating environment, those operating in resource-scarce settings rely on CCs to develop social innovation. While CCs facilitate the ability to work with other organizations (Davis & Friske, 2013; Yao et al., 2019), HSEs operating in resource-abundant settings rely on their AC to identify, assimilate, transform, and use external knowledge (Azadegan, 2011; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990).

This suggests that HSEs operating in resource-scarce settings rely on leveraging others’ involvement. However, those in resource-abundant settings rely on applying others’ knowledge. Examples of CCs include relationships with farmers to use their resources to develop new channels to minimize the cost of waste management and with distribution centers to improve perishable item delivery. Examples of AC include leveraging the external knowledge developed through research by partnering organizations and paying close attention to market patterns to explore viable new ideas.

The COVID-19 pandemic led HSEs to readjust their approaches. Under extraordinary operating circumstances, HSEs were faced with several other challenges, the first being the significant increase in demand. Second, the COVID-19 pandemic changed how food was delivered because of new social distancing and food preparation protocols. Moreover, the different stages of the pandemic carried different challenges. To combat these issues, HSEs shifted to using bricolage toward social innovation. Bricolage can recombine internal and external resources into new forms, apply diverse resources in novel ways, and transform material and tools toward developing new solutions (Baker & Nelson, 2005).

Interestingly, in extraordinary operating environments, HSEs operating in resource-scarce settings demonstrated competence in developing social innovation through bricolage. The type of bricolage that resource-scarce HSEs applied shifted from parallel to selective as the pandemic progressed (Baker & Nelson, 2005; Rönkkö et al., 2014). At the onset, HSEs had to find solutions to immediate problems using a reactive approach. Subsequently, using a more discriminating approach, they settled for one or a few areas. Figure 2 presents the overall findings.

Fig. 2.

Study design and propositions related to case study selection and differentiations

Within-Category Analysis

Here, we present the within-category analysis findings and describe how social innovation is developed by resource-scarce and resource-abundant HSEs. All resource-scarce HSEs have in common the fact that social innovations during ordinary operating environments were concentrated around improving operational efficiency. Examples include redesigning facility and warehousing operations to optimally use space, develop better work allocation, and use inexpensive local resources to build additional operational capabilities.

Resource-scarce HSEs were also heavily involved in building close relationships in their communities. Most served rural areas with low population densities in most counties and one main county with a higher population density. The within-category analysis indicated that low-density population areas strengthened the relationship between HSEs and their partners. Only a few food production and manufacturing entities were in areas served by resource-scarce HSEs. For example, Easton HSE serves a high resource-scarce area, requiring more efforts to collect donations. It does not receive much in terms of in-kind (financial) donations, making it more difficult to create an advantage based on incoming food and fund contributions. Most resource-scarce HSEs’ performance indicators are lower than the national average. Moreover, these HSEs were all subject to heavy budgeting constraints, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The within-category analysis of resource-abundant HSEs showed that serving densely populated areas provided more opportunities to attract volunteers. The larger number of manufacturers and wholesalers also made it easier to find food and funding sources, which limited the need for in-kind donations. However, resource-abundant HSEs serve millions of residents, which often overwhelmed them because of the broad range of expectations. However, the served areas promoted developing new internal organizational capabilities.

In the ordinary operating environment, resource-abundant HSEs focused on social innovation for new initiatives, such as enhanced food offerings, nutrition education programs, and reaching out to a larger proportion of the needy population. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the demand for these HSEs rose significantly, and the availability of some resources increased. This provided additional challenges.

Cross-Category Analysis

HSEs, Social Innovation, and the Hunger Crisis

The cross-category analysis suggests that resource availability plays a key role in how HSEs apply innovation in their ordinary operating environments. HSEs operating in resource-scarce settings looked for ways to leverage their working relationships with corporate partners, grocery stores, and other members of their supply networks to collectively apply their resources and talent to social innovation. To do so, they built and maintained strong partnerships with organizations within and beyond the humanitarian and food sectors. Sharing resources also helped reduce the burden on HSEs’ internal resources by assigning tasks, responsibilities, and resource procurement to other organizations. For instance, the Chief Operating Officer of Easton HSE explained how their ability to collaborate with grocery stores and hog farmers allowed them to reduce waste management costs.

The President and CEO of Georgetown HSE highlighted how food donations from a distant county were facilitated by “… strengthening the relationship with [the county] and acquiring more products” through leveraging collaborative relationships with orchards, corporate partners, and other partner agencies.

Another example of effective social innovation comes from the President and CEO of Irvine HSE. This HSE was able to build a vegetable garden bed through a collaborative effort with the local citizens and a landscaping company:

Because we do not have much money or products, we try to utilize the relationships we have. We started to grow some products, but we could not afford to [grow] what we needed. So, we had a group come out and build the [garden] beds. Then, we got the landscaping company to come in and fill in properly … and start growing food. (President and CEO, Georgetown HSE)

Another informant explains how his HSE improved the transportation process by collaborating effectively with a distribution center:

Collaborations and relationships are everything. Relationships really help us to be efficient. … We know receiving docks and grocery stores can be very busy at certain times. [But] if you establish that relationship well, you might get in and out of a store much quicker. You also will gain more flexibility with them, in terms of if altering your route is made better by changing your time in the store. (President and CEO, Kingston HSE)

HSEs operating in resource-abundant settings do not face high resource constraints because they have adequate resources for learning from external entities. However, they need to be able to implement and customize external innovative ideas to fit their internal needs. They thus emphasize developing capabilities to detect new ideas and evaluate them for internal use, or what is labeled as AC in the literature. To be clear, AC is the mere use of external knowledge and its application by internal resources, as it assesses the organization’s ability to learn from the outside.

Several HSEs in this category emphasized focusing on possible opportunities to develop social innovation through formal and informal interactions with outsiders. The key informants mentioned they encouraged routine meetings, conferences, workshops, and community events as incubators for gathering ideas. For instance, several HSEs in this category paid close attention to research work by a national organization focused on hunger relief. These HSEs routinely attended their conferences and webinars to learn potential ways to improve operations. One informant noted: “We learn from them [the national organization] and innovate based on their research and suggestions” (CEO, Lebanon HSE). Others highlighted the importance of monitoring the external context and sharing ideas. Interestingly, the Executive Director of Barrington HSE focuses on books about innovation that highlight how to implement ideas developed elsewhere. Another informant summarizes this approach as follows:

We implement almost all new ideas; we try to see if it works with us. We closely look at the food market situation and make a better product and do a better service as a result of that. (Chief Operating Officer, Danville HSE)

Additional examples of CC use and AC use are presented in Table 3. This leads to our first pair of propositions:

Table 3.

Examples of innovation activities in an ordinary operating environment

| Ordinary operating environment (P1a/P1b) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource-abundant HSEs: examples of innovation activities | Resource-scarce HSEs: examples of innovation activities | ||

| Absorptive capacity | Collaborative capabilities | ||

| Albany HSE | Use air cover provided by national organizations to monitor the market situation in real time to create a superior product. (Proposition 1b) | Easton HSE | Used reverse utilization chain offered by stores and hog farmers combined with internal transportation to develop solutions for waste management |

| Barrington HSE | Leverage knowledge acquired through books about innovation that highlight how to implement ideas developed elsewhere. (Proposition 1b) | Georgetown HSE | Set up the process of receiving food from a distant county using resources provided by county orchards to find innovative ways of acquiring product |

| Camden HSE | Communicate with the downstream supply chain partners to acquire new information used to develop unique distribution network. (Proposition 1b) | Hamilton HSE | Used established relation ship with grocery stores to find different ways to acquire product that has been diverted off the record. (Proposition 1a) |

| Danville HSE | Implement almost all new ideas to understand whether the ideas work for HSE. (Proposition 1b) | Acquired financial&physical resources from donors and internal excessive capacities to open a nonprofit store to innovatively reach more people | |

| Monitor the food market trends to make a better product and do a better service by using that information. (Proposition 1b) | Irvine HSE | Build a new vegetable garden bed through collaborative effort with the local citizens, a landscaping company, and HSE's internal volunteers | |

| Franklin HSE | Using information acquired through attending conferences, invent solutions focused on increasing the number of programs offered to reach a broader group. (Proposition 1b) | Jackson HSE | Employ a marketing specialist provided by a partner agency jointly with internal director of development to develop innovative promotional campaign. (Proposition 1a) |

| Lebanon HSE | Paid close attention to research work done by a national organization and routinely attend webinars to learn about potential ways to improve operations. (Proposition 1b) | Kingston HSE | Used transportation equipment provided by community partners and HSE's drivers to start holding mobile pantries to feed seniors in the rural areas. (Proposition 1a) |

Proposition 1a

In ordinary operating environments, the practice of CC by resource-scarce HSEs leads to social innovation.

Proposition 1b

In ordinary operating environments, the practice of AC by resource-abundant HSEs leads to social innovation.

HSEs, Social Innovation, and Bricolage During the COVID-19 Pandemic

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, an extraordinary operating environment added to the lack of available resources and changed the operating context of HSEs drastically. The demand for food and food delivery increased while donations decreased. One informant noted:

Before the pandemic, we picked up food from more than 300 retail partners, but the panic buying (by customers) during the first few months of the pandemic drained our stores. The rescued food was down to about 30% of what we usually get. (President and CEO, Danville HSE)

Further, HSEs were forced to carefully consider how to use their resources. During the pandemic, HSEs had to find creative solutions to reorganize processes, improve operational efficiency, and restructure delivery performance. Some tried to “make do” using resources that provided some means, no matter how limited. Such arrangements were necessary because of the significantly reduced food supply through groceries. For instance, Irvine HSE used its familiarity with trucking companies to find independent truckers that could find excess food nearby. Its President and CEO highlighted that Irvine HSE arranged for rejected loads to be delivered to them by these independent truckers.

Another approach is “resource recombination” (Senyard et al., 2014). For instance, an HSE was able to rearrange its material delivery process. The President and CEO of Barrington HSE explained how they and their downstream partners reconfigured the use of personnel and delivery process to develop a “grab-and-go” food center. Using existing resources, the new food center complied with social distancing mandates while providing easy access to food for families with school children.

Another informant explained how reassigning paid staff members helped respond to COVID-19. At a time when the number of volunteers was drastically reduced because of health concerns,2 the reconfiguration of human resources helped deal with the new challenges:

We are a large organization; we have a larger staff team and a larger volunteer base [as compared to other HSEs, [but] we were significantly affected [by the pandemic]. We readjusted our operations to fit our tight budget. We could not get help from volunteers, so all our staff members were doing all sorts of warehousing jobs. (Chief Operating Officer, Albany HSE)

Additional examples of the use of bricolage are presented in Table 4. The above quotes, along with other evidence, suggest that HSEs emphasized bricolage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we posit:

Table 4.

Examples of innovation activities in an extraordinary operating environment

| Extra-ordinary operating environment (P2-P3a/P3b) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Resource-abundant HSEs: examples of innovation activities | ||

| Absorptive capacity | Bricolage | |

| Albany HSE | Readjusted operations to fit the budget; no help from volunteers, staff members were doing all sort of warehousing jobs. Needed to be efficient | New environment forced to innovate but first were unable to respond due to the inability to reuse past knowledge. (Proposition 3b) |

| Barrington HSE | With no resources, created a new distribution network for school lunch programs, an alternative to backpack program: grab-and-go food centers | Needed to shut the programs (e.g., nutrition awareness, driving school, cooking classes) down during COVID; the skills utilized before COVID were not much at help when the things went crazy. (Proposition 3b) |

| Camden HSE | Concentrated on cutting the costs down and using everything we have. We did that by dividing our team up and we sent trucks to different locations | |

| Danville HSE | The panic buying (by customers) drained the stores; HSE needed to find other ways to find the product. Volunteers were not able to come to us so we contacted them and asked to leave some foods by the door; we were able to pick that food up. (Proposition 2) | Spent much resources on developing skills so that the organization could effectively respond to the disaster, proved to be ineffective. It took some time to figure out the way to move forward during COVID. (Proposition 3b) |

| Franklin HSE | Readjusted administrative structure so that full-time employees were performing innovative tasks. (Proposition 2) | The services grew to 500% more direct distributions a month and the knowledge assimilated before during COVID proved to be impractical |

| Lebanon HSE | Pivoted everything through drive-thru now, trying to eliminate and decrease the amount of contact anybody has with the clients.(Proposition 2) | Required to wait for the research work to appear before concentrating on developing innovations. (Proposition 3b) |

| Resource-Scarce HSEs: Examples of Innovation Activities | ||

|---|---|---|

| Collaborative Capabilities | Bricolage | |

| Easton HSE | Pandemic forced to come up with innovative solutions at accelerated rate using only resources that we had on hands. (Proposition 2) | Utilized the technology provided by the long-term tech partner to create fundraising events online that employees used to connect with donors. (Proposition 3a) |

| Georgetown HSE | Combined resources from different departments to find innovation solutions for solving the lack of volunteers. (Proposition 2) | Started hosting calls with other organizations to teach them some of the collaboration approaches acquired before the pandemic due to operating environment constraints. (Proposition 3a) |

| Hamilton HSE | Partnered with a cloud based tech company that shared how to create a fundraising events online; able to utilize some of partners' technology that we did not use before. We would have never thought that we would need it. (Proposition 2) | Employed community conventions to utilize regular volunteers from various sectors. (Proposition 3a) |

| Jointly with a close partner (health food manufacturing company) started handing out boxes of ingredients that students could use to construct their own customizable meals. (Proposition 3a) | ||

| Irvine HSE | The grocery stores were out food so we were able to get some extra food from independent trackers. (Proposition 2) | To respond to the demand increase, build the capacity of the partners by combining internal and community resources. (Proposition 3a) |

| Jackson HSE | Both HSEs focused on direct distribution. Found new ways to use old technologies to identify areas in high need; so that the employees can target those areas directly. (Proposition 2) | Partnered with pantries to find alternative locations for regular volunteers to work with maintaining social distance guidelines |

| Kingston HSE | Started to grow products but we could not afford; created a system of connecting with the community to get seeds, beds, dirt, volunteers | |

Proposition 2

In extraordinary operating environments, the practice of bricolage by HSEs leads to social innovation.

HSEs and the Effectiveness of Social Innovation During the COVID-19 Pandemic

We noted earlier how the CCs used by some HSEs helped develop social innovation during ordinary operating times. Interestingly, the case evidence suggests that CCs were also particularly useful during the COVID-19 pandemic for HSEs operating in resource-scarce settings. However, during the pandemic, the lack of available resources became a far-reaching concern. For instance, an HSE operating in a resource-scarce setting had to resort to using whatever resources were available from the community to grow the vegetables they used to grow themselves:

[During the COVID-19 pandemic] … we started to grow some products, but we could not afford to [grow] what we needed so we created a whole system of connecting with the community to get seeds, beds, dirt, volunteers. (Director of Relationship Management, Kingston HSE)

The President and CEO of Hamilton HSE explains how they used past relationships to create a system for delivering ready-to-make meals to university students. Another informant explained how his organization was able to apply an earlier agreement with a tech company responsible for data storage to receive pro-bono training on online fundraising (Executive Director, Easton HSE). However, this is in contrast to how developing social innovations internally (i.e., AC) helped resource-abundant HSEs. One informant explained how knowledge from their internally developed nutrition awareness programs “were not much help when the things went crazy.” (Director of Development, Barrington HSE).

Others highlighted how, during the pandemic, the ability to gather and leverage external knowledge to develop internal initiatives seemed disconnected from the served population’s immediate and urgent needs. Further, the acuity of this crisis did not allow them to gather, analyze, and carefully implement external knowledge promptly, nor did the best practices gathered by resource-abundant HSEs before the COVID-19 pandemic fit needs. The Director of Partnership & Programs of Franklin HSE explained how some of the information sources used for AC were unavailable during the pandemic.

In short, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the CCs previously developed by resource-scarce HSEs were useful for social innovation. For example, one informant from a resource-scarce HSE explains how the “struggling” during the chronic crisis actually prepared them to better face the acute crisis. She also mentioned how resource-abundant HSEs were not privy to the same collaborative experiences (President and CEO, Hamilton HSE). Interestingly, she continued to explain how her HSE was able to offer guidance on its collaborative approach to other HSEs when the pandemic struck. Other informants also confirmed that sharing their novel approaches used by resource-scarce HSEs was in demand:

We had an online seminar where less fortunate organizations were sharing some of their strategies we were employing for years. (VP of Community Relations, Kingston HSE)

During COVID, we started to host calls with other organizations to teach them some of the things we learnt due to our area constraints. (Senior Manager of Partnerships, Georgetown HSE)

This leads us to our next propositions:

Proposition 3a

In extraordinary operating environments, the practice of CC leads to the ability of resource-scarce HSEs to develop social innovation.

Proposition 3b

In extraordinary operating environments, the practice of AC does not lead to the ability of resource-abundant HSEs to develop social innovation.

HSEs and Parallel Bricolage at the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic created unique challenges. First, a particularly important challenge was the unprecedented increase of vulnerable populations (children and senior adults). Effectively meeting the needs of these groups required additional steps in the delivery process. Some groups also had special dietary needs. Second, many HSEs had to radically reconsider their sorting, packaging, preparation, and delivery processes to comply with the social distancing and food preparation (food-to-surface exposure) requirements.

Third, the demand and supply changed. For instance, the number of volunteers and amounts of donated food diminished significantly. Simultaneously, financial support from the national organization increased. One informant noted how over 90% of HSEs’ demand modeling and network analysis was no longer applicable at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. All these factors created an exceedingly uncertain and ambiguous environment, thus requiring a drastic readjustment in how resources were used.

At the onset of the pandemic, resource-scarce HSEs relied on parallel bricolage to develop social innovation. Using resources, such as labor, material, and infrastructure, was targeted at improving as many areas as quickly as possible. One informant explained that, because of the chaotic nature of the onset, they tried many different novel ways to “reach people, estimate the demand, reestablish operations” (Chief Operating Officer, Jackson HSE). Another explained how his HSE started a new program to engage virtual volunteers, partnered with a local community group to promote fundraising, and worked on reorganizing its processes:

We did many innovations simultaneously since April. One of the most innovative ways was called "virtual volunteers." We used our Instagram and Facebook accounts to help spread the word [for available service] around the community. We also partnered with a dozen small community groups and local churches that virtually helped us to promote our message [for fundraising] … And of course [our] operations needed to be reorganized too.

The President and CEO of Hamilton HSE explained how his HSE tried to spread its resources to find new and creative ways for funding, food delivery, packaging, and volunteer recruitment. He reiterated the point above by noting: “it was an unprecedented situation, we needed to be creative in every aspect.” The Chief Operating Officer of Easton HSE explained how his HSE was involved in parallel bricolage at several levels and in several areas. For instance, it relied on staff to provide general life skills for the newly vulnerable population and developed new delivery systems and improved warehouse sorting and packaging operations.

In hindsight, many informants were not fully satisfied with the outcomes of their attempts at parallel bricolage and attested to its shortcomings. One informant noted:

“We might have been better [off] if we just focused on one thing and let other organizations do the rest, but we did not know where or how to start.” Another explained: “Surely, we could have been more efficient and not spread our attention on so many things, but it was just so hard.”

Nevertheless, the uncertainty and ambiguity led many HSEs to accept the ramifications of working on a diverse set of efforts, even if some may have led to hasty and amateurish results. Additional examples of the use of parallel bricolage are presented in Table 5. In short, HSEs were faced with a surprisingly demanding and unprecedented set of circumstances at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and used parallel bricolage for developing multiple social innovations simultaneously. Therefore:

Table 5.

Examples of parallel and selective bricolage activities

| Extra-ordinary operating environment (P4–P5) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Initially faced Parallel bricolage |

Familiarized Selective bricolage |

|

| Easton HSE | Needed to start from scratch—rethink boxing, storing, distribution operations in light of social distancing and mass closings. Forced to innovate to supplement significant drops in both cash and food donations. Tried to find new ways to get cash, but then VP team stepped in significantly, so we moved toward transformation of operations jointly with looking for some fresh ides to how to rescue food. (Proposition 4) | Concentrated on ways to improve the reduced volume from the retail supply chain. To increase the food donations, started a social media campaign teaching local community members how to start a physical food drive. Within two weeks, increased our food donations by 20%. (Proposition 5) |

| Georgetown HSE | Needed to spread attention across many innovative activities. Came up with new ways to comply with federal, health and safety laws. Organized an online volunteer legal and safety consultant team. Disorder was everywhere, tried to find novel ways to reach people, estimate the demand, and distribution model. (Proposition 4) | Developed innovation to turn the system of delivery around. A lot of the packaging was not happening at warehouse facilities, it's happening on a local level [distribution] where there's a smaller amount that needs to be packed and a smaller group of people can come together. (Proposition 5) |

| Hamilton HSE | Needed to be creative in every aspect. It was critical to find extra resources to come up with new and creative ways in added funding, food delivery, packaging. Started doing online fundraising event: university assisted by sharing tips and going access to the software. (Proposition 4) | Focused on readjusting classes. Started doing recorded classes; offered classes virtually through video. Members of the team can be on a Zoom meeting and show a two to three minutes segment of the grocery store's tour in the fresh produce section. Then the video stops and they have a conversation about what they've just learned or heard with their classmates on Zoom. (Proposition 5) |

| Irvine HSE | Developed many innovations simultaneously. Organized "virtual volunteers." Used Instagram and Facebook accounts to spread the word [for available service] around the community. Partnered with small community groups and local churches that virtually assisted in promoting messages [for fundraising]. Reorganized operations. (Proposition 4) | Selected to focus on virtual volunteers. Started hosting Zoom meetings for virtual fundraising events. During the first 3 months, received so many individual donations, that needed thousands of thank you notes cards, had families that were writing thank you notes for donors, children drawing pictures. (Proposition 5) |

| Jackson HSE | Innovations were focused on various areas but most developed using only in-house resources. Needed to find creative ways to have executive meeting, repackage food donations into smaller quantities, connect with donors virtually, redesign the warehouse layout to comply with social distancing requirements. (Proposition 4) | Once the initial chaos was gone, finally had all hands-on deck for the first time. When Governor announced that students are returning to campus, needed to concentrate on them as well as our K-12 feeding programs. Focused innovation on students, and parents, access mobile-ordered meals from campus dining outlets and pantries |

| Kingston HSE | Forced to think creatively to overcome the environmental limitations created by COVID. To serve high-risk senior populations, employees and regular volunteers were driving around the area and were leaving food packages on the door steps. Might have been better off focusing on one area, but did not know where or how to start. (Proposition 4) | Took time to understand but were able to adapt to the situation. The biggest issue was the food supply going down, so concentrated creative abilities on creating a virtual wish lists. People were bringing items that were posted online and the companies were delivering it right to the warehouse. (Proposition 5) |

Proposition 4

When initially faced with an extraordinary operating environment, the practice of parallel bricolage in multiple domains of activity by resource-scarce HSEs leads to social innovation.

HSEs and Selective Bricolage Over the Progression of COVID-19 Pandemic

The challenges associated with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a presumably hasty approach to social innovation by making improvements in diverse areas. However, the progression of the pandemic created distinct challenges. To start with, the demand volume steadily rose to record levels. Those in need kept increasing in numbers because more heads of household were losing jobs. As one informant noted, “We had an about 500% increase in the number of people that rely on our services.” As the pandemic progressed, the food and cash reserves from donated funds depleted, and funding by the national organization was reduced. Overall, the progression of the pandemic led to exhausted resources and a substantial rise in demand.

These challenges were rather burdensome but also provided opportunities for HSEs to become more familiar with the operating task environment. The challenges became simpler to define and to find solutions for. In short, dealing with these challenges was added to the know-how of HSEs. More importantly, facing familiar problems allowed HSEs to prioritize where their efforts could be most valuable.

As the pandemic progressed, HSEs applied selective bricolage. For instance, at the onset of the pandemic, Jackson HSE tried to work on five different ways to reach several rural communities (parallel bricolage). As it became more familiar with the pandemic, it chose to concentrate on fewer communities, which could be best served by fewer and better-planned initiatives (selective bricolage). The Director of Development explains: “Once the initial chaos was gone, it felt like we [Jackson HSE] finally had all hands-on deck for the first time.” Ultimately, Jackson HSE concentrated its efforts on using campus dining outlets to deliver meals to university students.

Another HSE faced a heavy shortage of in-kind donations as the pandemic progressed. It thus decided to concentrate on increasing its donations through physical food drives launched through online social media campaigns. The key informant notes:

In September, we concentrated on ways to improve the reduced [volume from the] retail supply chain. To increase the food donations, we started a social media campaign that was teaching our local community members how to start a physical food drive. Many families, businesses, [and] charitable organizations suggested holding food drives. Within two weeks, we increased our food donations by 20%. (Executive Director, Easton HSE)

Kingston HSE faced a severe shortage of volunteers because of the fear of exposure to the virus as the pandemic progressed. The President and CEO decided to focus on increasing the volunteer base by reworking its operations using virtual meetings.

The President and CEO of Irvine HSE highlighted how the enterprises focus on improving beneficiary access. Namely, it set up freestanding (unmanned) outdoor pantries on school properties. The outdoor pantries were available to everyone in the community and operated using the "take what you need, give what you can" credo. Another HSE focused on realigning its packaging and delivery resources to get food closer to beneficiaries. Instead of focusing on multiple delivery systems, it worked on revamping its delivery system using existing resources:

We tried to turn that system [of delivery] around. A lot of the packaging is not happening at the hunger-relief organization now, it's happening on a local level where there's a smaller amount that needs to be packed and a smaller group of people can come together in a local food pantry to do the packing that needs to be done for their community. (President and CEO, Hamilton HSE)

Additional examples of selective bricolage are presented in Table 5. In short, over the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic, resource-scarce HSEs were faced with unprecedented demand and exhausted resources. However, as they were already familiar with these challenges, they were able to prioritize and focus their attention on a few areas with the potential to make the most impact. Therefore,

Proposition 5

When familiarized with the extraordinary operating environment, the practice of selective bricolage in limited domains of activity by resource-scarce HSEs leads to social innovation.

Discussion

This study explored how HSEs develop social innovations. We found that, during ordinary operating times, HSEs operating in resource-abundant settings use AC to innovate, which is traditional in innovation development. Indeed, the availability of resources allows for a better search for external knowledge and its application to internal settings. By contrast, those operating in resource-scarce settings use their capabilities to nurture partnerships, innovation alliances, and innovation networks, which are CCs (Dhanaraj & Parkhe, 2006; Stuart, 2000). These HSEs have no choice but to engage with other organizations and collaboratively develop social innovation.

The most counter-intuitive finding is that the shortcomings faced by resource-scarce HSEs work to their advantage when faced with extraordinary circumstances that entail a severe shortage of available resources. The experience of working in difficult contexts allows resource-scarce HSEs to recognize useful capabilities and apply them in new and different ways. Bricolage, or “making do” with whatever is available, becomes the main arsenal of capabilities for resource-scarce HSEs during extraordinary circumstances. We did not find any evidence of bricolage in ordinary times for both resource-scarce and resource abundance HSEs. Interestingly, the type of bricolage used to develop social innovation can change form in an extraordinary operating environment. Crisis lifecycle models suggest that, as a crisis progresses, organizations understand it better and can better react to its ramifications (Fink et al., 1971). Barring out-of-control circumstances (i.e., escalating crises), the progression of an extraordinary circumstance usually implies that challenges can become more predictable (Fink et al., 1971), which we confirm. Whereas the onset of COVID-19 involved using parallel bricolage by spreading resources across many areas, as the crisis progressed, a more systematic, prioritized, and focused approach to social innovations was used. Interestingly, the extraordinary circumstances highlight the potential for the limited effectiveness of parallel bricolage. Indeed, the literature suggests that applying resources to numerous parallel initiatives may result in a bricolage “trap” that restricts innovation success (Fisher, 2017). Instead, better prioritization and planning through selective bricolage helps develop social innovation.

Theoretical Contributions