Abstract

Objectives Endometriosis is a chronic disease which is diagnosed by surgical intervention combined with a histological work-up. Current international and national recommendations do not require the histological determination of the proliferation rate. The diagnostic and clinical importance of the mitotic rate in endometriotic lesions still remains to be elucidated.

Methods In this retrospective study, the mitotic rates and clinical data of 542 patients with histologically diagnosed endometriosis were analyzed. The mean patient age was 33.5 ± 8.0 (17 – 72) years, and the mean reproductive lifespan was 21.2 ± 7.8 (4 – 41) years. Patients were divided into two groups and patientsʼ reproductive history and clinical endometriosis characteristics were compared between groups. The study group consisted of women with confirmed mitotic figures (n = 140, 25.83%) and the control group comprised women without proliferative activity according to their mitotic rates (n = 402, 74.27%).

Results Women with endometriotic lesions and histologically confirmed mitotic figures were significantly more likely to have a higher endometriosis stage (p = 0.001), deep infiltrating endometriosis (p < 0.001), ovarian endometrioma (p = 0.012), and infertility (p = 0.049). A mitotic rate > 0 was seen significantly less often in cases with incidental findings of endometriosis (p = 0.031). The presence of symptoms and basic characteristics such as age, age at onset of menarche, reproductive lifespan and parity did not differ between the group with and the group without mitotic figures.

Conclusion This study shows that a simple histological assessment of the mitotic rate offers additional diagnostic value for the detection of advanced stages of endometriosis. The possible role as a predictive marker for the recurrence of endometriosis or the development of endometriosis-associated cancer will require future study.

Key words: endometriosis, mitotic rate, infertility, laparoscopy, endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer

Zusammenfassung

Ziele Endometriose ist eine chronische Erkrankung, die durch einen chirurgischen Eingriff und einen histologischen Nachweis diagnostiziert wird. Laut den aktuellen internationalen und nationalen Empfehlungen ist der histologische Nachweis der Proliferationsrate nicht nötig. Die diagnostische und klinische Bedeutung der Mitoserate in endometriotischen Läsionen ist immer noch ungeklärt.

Methoden In dieser retrospektiven Studie wurden die Mitoseraten und die klinischen Daten von 542 Patientinnen mit histologisch nachgewiesener Endometriose analysiert. Das durchschnittliche Alter der Patientinnen betrug 33,5 ± 8,0 (17 – 72) Jahre, und ihre durchschnittliche Reproduktionsspanne lag bei 21,2 ± 7,8 (4 – 41) Jahren. Die Reproduktionsgeschichte und klinischen Endometriosemerkmale wurden verglichen. Die Studiengruppe bestand aus Frauen, bei denen Mitosefiguren nachgewiesen wurden (n = 140, 25,83%), und die Kontrollgruppe bestand aus Frauen ohne Proliferationsaktivität (n = 402, 74,27%).

Ergebnisse Frauen mit endometriotischen Läsionen und einem histologischen Nachweis von Mitosefiguren hatten signifikant häufiger ein klinisch höheres Endometriosestadium (p = 0,001), tief infiltrierende Endometriose (p < 0,001), ovarielle Endometriome (p = 0,012) oder Infertilität (p = 0,049). Frauen, bei denen eine Endometriose als Zufallsbefund entdeckt wurde, hatten signifikant weniger oft eine Mitoserate von > 0 (p = 0,031). Es gab keine Unterschiede in den Symptomen und Charakteristika wie Alter, Menarche, Reproduktionsspanne und Parität zwischen der Gruppe mit und der Gruppe ohne Mitosefiguren.

Schlussfolgerung Diese Studie zeigt, dass eine einfache histologische Evaluierung der Mitoserate für die Erkennung einer Endometriose im fortgeschrittenen Stadium einen diagnostischen Mehrwert bietet. Um die Bedeutung der Mitoserate als prädiktiven Marker für das Wiederauftreten einer Endometriose bzw. für die Entwicklung von endometrioseassoziiertem Krebs zu evaluieren, werden weitere Untersuchungen benötigt.

Schlüsselwörter: Endometriose, Mitoserate, Infertilität, Laparoskopie, endometrioseassoziiertes Ovarialkarzinom

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common gynecological disease which is typically diagnosed by a histological examination after laparoscopy. Around 10% of women aged 15 – 50 years suffer from dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, abdominal and pelvic pain as well as infertility and are diagnosed with endometriosis 1 . The presentation of symptoms in women with endometriosis is suggestive for the location of the endometriotic lesions and the clinical stage 2 , but up to now, the definitive diagnosis of endometriosis needs surgery. Serum markers for endometriosis are being investigated but have not yet been clinically established 3 , 4 .

International and national guidelines recommend a histological assessment after surgical procedures to make a diagnosis of endometriosis 5 , 6 . An initiative to evaluate the quality of care in endometriosis centers in German-speaking countries in Europe was recently published 7 . It reported that all certified endometriosis centers took biopsies to confirm endometriosis histologically.

Nevertheless, the current guidelines give no clear statements about the specific procedures for the histological assessment 5 , 6 . Standardized quality indicators for diagnosis and therapy have not been implemented to date 7 .

Mitotic figures as a marker of cell proliferation in endometriotic lesions were initially described by Nisolle and Donnez 8 , 9 . The detection of mitotic figures and determination of the mitotic rate per 10 high-power fields after staining with hematoxylin and eosin is an established marker of cellular proliferation in oncology 6 . The disadvantages of counting mitotic figures are the high inter- and intra-observer variation rates and limited reproducibility 10 , 11 . Another marker of cell proliferation proposed for the diagnosis of endometriosis is Ki-67 12 .

Using the mitotic rate as an additional histopathological assessment of cellular proliferation is an established, cost-efficient procedure and part of the routine histological examination. It is routinely used not only in oncology but also for the histological diagnosis of endometriosis.

Atypical ovarian endometriosis is known to be especially associated with an increased risk of malignancy 13 . Currently, molecular mechanisms and biomarkers are being carefully investigated in women with endometriosis to find a diagnostic algorithm for the prediction and possibly prevention or treatment of women with an increased risk of endometriosis-associated malignancies 14 . Histological parameters of cell proliferation may have an additional diagnostic value when assessing the severity of endometriosis but could also serve as predictive markers for the development of malignant epithelial tumors.

This study aimed to assess the diagnostic impact of detected mitotic figures as a marker of proliferation in endometriotic lesions in a retrospective study carried out at a tertiary university endometriosis center.

Material and Methods

A total of 812 patients with a diagnosis of endometriosis were treated at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics in a tertiary university center during the study period from 2013 to 2016. The patientsʼ clinical data were analyzed after ethical approval of the study protocol (by the local Ethics Committee of TU Dresden, EK 189062018) and the consent of study participants treated in the University Endometriosis Center was obtained.

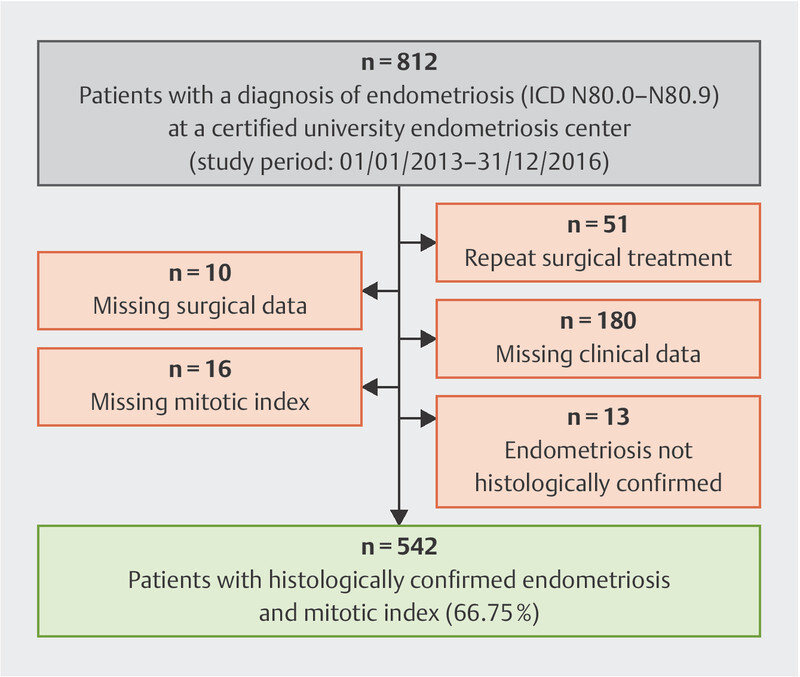

Patient characteristics

After patients without biopsies showing endometriosis and a histological assessment which included a mitotic figure count in standardized HPF areas after H & E staining were excluded, a total of 542 patients remained and were included in this study. No additional staining to evaluate cellular proliferation, e.g., using Ki-67, was performed. Each patient was only included once in the study even if they underwent repeat surgical treatment in the same hospital. The inclusion chart of the study is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Flowchart showing the inclusion into the retrospective study of patients treated for endometriosis at a university center.

Measurements

The following parameters were assessed: diagnosis based on the international classification of diseases, symptoms, medical history including medication, previous pregnancies, abortions and births, organ manifestations, endometriosis stage based on the rASRM score (revised score of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine) 15 , histology, surgical intervention and recommended endocrine treatment. The ENZIAN classification was used for deep infiltrating endometriosis 16 . As not all lesions were documented photographically, further classification of each endometriotic lesion into typical or atypical as proposed by Nisolle et al. 17 could not be performed systematically in the setting of a retrospective study.

The mitotic figure count was determined after H & E staining and performed as a standardized procedure used for histological assessment in oncology. The method was described by Barry et al. in 2001 11 .

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V. 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). χ 2 and Fisherʼs exact tests were used for the analysis of categorical variables. Quantitative variables were compared using Mann-Whitney U test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 542 patients with histologically confirmed endometriosis were included in the study. The mean age of these patients was 33.5 ± 8.0 years. The majority of the women were nulligravida (n = 313, 58.29%); 350 (66.04%) had not previously given birth.

Analysis and mitotic figure count

After mitotic figures were counted, 402 women (74.27%) were found to have no mitotic figures in 10 microscopic high-power fields (HPF). These women were assigned to the control group of women without proliferative activity based on mitotic figures. 140 women (25.83%) had at least one mitotic figure in 10 HPFs and were diagnosed as having endometriosis with proliferative activity based on the presence of mitotic figures. The mean number of mitotic figures was 0.4 ± 0.8 (0 – 7) for all patients included in the study. Six women had three mitotic figures, four and five mitoses were counted in three women respectively, and seven mitotic figures were counted in one woman. As the number of women with a higher mitotic index was small, no additional statistical analysis was performed to assess the association between mitotic index and disease severity.

The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of women with histologically confirmed endometriosis (n = 542). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (median, range) or number (%).

| Clinical characteristics | Patients |

|---|---|

|

rASRM: revised classification of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine

9

.

1 In 19 cases no rARSM classification was given; 9 of those women had endometriosis of the abdominal wall without laparoscopy and 10 women had adenomyosis. The ENZIAN score was used for those clinical entities. | |

| Age (years) | 33.5 ± 8.0 (17 – 72) |

| Obstetric history | |

|

313 (58.29%) |

|

350 (66.04%) |

| Age at onset of menarche (years) | 13.0 ± 1.50 (9 – 17) |

| Reproductive lifespan (years) | 21.2 ± 7.8 (4 – 41) |

| Mean duration of menstrual cycle (n = 286) | 29.5 ± 7.6 (13 – 90) |

| Mean duration of menstrual bleeding (n = 314) | 5.7 ± 1.8 (2 – 15) |

| Previous history of endometriosis | |

|

404 (74.54%) |

|

128 (23.61%) |

| Main reason for surgery | |

|

192 (35.42%) |

|

130 (23.99%) |

|

100 (18.45%) |

| Symptoms prior to surgery | |

|

238 (43.91%) |

|

56 (10.33%) |

|

42 (7.75%) |

|

103 (19.00%) |

|

210 (38,74%) |

|

80 (14.8%) |

| Concomitant gynecological diagnoses | |

|

32 (5.90%) |

| Surgery | |

|

152 (28.04%) |

|

390 (71.96%) |

|

496 (91.51%) |

|

36 (6.60%) |

| Occurrence of endometriosis | |

|

58 (10.70%) |

|

180 (33.21%) |

|

103 (19.00%) |

|

185 (34.13%) |

| rASRM classification (n = 523) 1 | |

|

214 (40.92%) |

|

95 (18.16%) |

|

111 (21.22%) |

|

103 (19.69%) |

| Hormonal treatment at the time of surgery | 102 (18.82%) |

| Mean number of probes for histological assessment | 3.2 ± 1.8 (1 – 13) |

| Mean mitotic rate | 0.4 ± 0.8 (0 – 7) |

Presence of mitotic figures and clinical characteristics

The clinical data of the two subgroups were compared based on the presence of mitotic figures in up to 10 HPF. The results of this comparison are shown in Table 2 . Surgery was planned significantly more often because of acute or chronic pain (p = 0.018) in the subgroups with mitotic figures. The predominant reason for surgery was infertility, and there were no significant differences between the two subgroups with regard to infertility, whereas a diagnosis of endometriosis during surgery for other reasons was more frequent in the group without mitotic figures (p = 0.031).

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of the subgroups without and with mitotic figures as a marker of active proliferation in 542 women with histologically confirmed endometriosis.

| Clinical characteristics | Endometriosis without mitotic figures (n = 402) | Endometriosis with a mitotic rate ≥ 1 (n = 140) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Significant differences: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001. 1 Other indications for surgery were: ovarian cysts not suspicious for endometriosis (n = 45), surgery for fibroids (n = 29), hysterectomy (n = 14), ectopic pregnancy (n = 6), suspected uterine malformation (n = 3), cryopreservation of ovarian tissue (n = 2), tubal sterilization (n = 1). | |||

| Age (years) | 33.9 ± 8.2 (17 – 72) | 32.5 ± 7.2 (19 – 55) | 0.134 |

| Obstetric history | |||

|

233 (58.25%) | 80 (58.39%) | 0.772 |

|

263 (65.91%) | 87 (63.50%) | 0.925 |

| Age at onset of menarche (years) | 13.1 ± 1.5 (9 – 17) | 12.9 ± 1.4 (9 – 16) | 0.667 |

| Reproductive lifespan (years) | 21.9 ± 8.1 (4 – 41) | 19.4 ± 6.5 (5 – 35) | 0.023* |

| Mean duration of menstrual cycle (n = 286) | 29.3 ± 7.3 (13 – 90) | 29.9 ± 8.2 (21 – 90) | 0.643 |

| Mean duration of menstrual bleeding (n = 314) | 5.6 ± 1.8 (2 – 14) | 5.9 ± 2.0 (3 – 15) | 0.138 |

| Previous history of endometriosis (n = 397) | |||

|

305 (76.83%) | 99 (73.31%) | 0.239 |

|

92 (23.17%) | 36 (26.69%) | |

| Predominant reason for surgery | |||

|

150 (37.78%) | 42 (31.11%) | 0.018* |

|

90 (22.67%) | 40 (29.62%) | 0.415 |

|

83 (20.64%) | 17 (12.14%) | 0.031* |

| Symptoms prior to surgery | |||

|

255 (63.43%) | 86 (61.42%) | 0.685 |

|

178 (44.28%) | 60 (42.9%) | 0.843 |

|

35 (8.71%) | 7 (5.00%) | 0.199 |

|

82 (20.40%) | 21 (15.00%) | 0.171 |

|

44 (10.95%) | 12 (8.57%) | 0.268 |

|

147 (36.37%) | 63 (45.00%) | 0.049* |

|

63 (15.67%) | 17 (12.14%) | 0.336 |

| Surgery | |||

|

373 (93.02%) | 123 (87.86%) | 0.036* |

|

23 (5.74%) | 123 (9.29%) | |

| rASRM classification (n = 523) | |||

|

179 (45.90%) | 35 (26.32%) | |

|

67 (17.18%) | 28 (21.05%) | 0.001* |

|

74 (18.97%) | 37 (27.82%) | |

|

70 (17.95%) | 33 (24.81%) | |

| Hormonal treatment | 81 (20.15%) | 21 (15.00%) | 0.210 |

|

55 (13.7%) | 18 (12.9%) | 0.886 |

| Only one biopsy for histological assessment | 71 (17.67%) | 12 (8.56%) | < 0.001** |

| Occurrence of endometriosis (n = 542) | |||

|

42 (10.42%) | 16 (11.43%) | 0.752 |

|

121 (30.31%) | 59 (42.14%) | 0.012* |

|

37 (9.20%) | 32 (22.86%) | < 0.001* |

| Peritoneal adhesions | 140 (34.83%) | 45 (32.14%) | 0.606 |

| Other ovarian cysts | 49 (12.19%) | 15 (10.71%) | 0.761 |

| Uterine malformations (n = 451) | 27 (6.72%) | 5 (3.57%) | 0.214 |

We found no statistical difference between the two groups with regard to self-reported symptoms prior to surgery. Only infertility was more common in women with mitotic figures (45.0%) than in the subgroup without detected mitotic figures (36,4%). The mean reproductive lifespan from the onset of menarche to surgery for endometriosis was significantly shorter in women with detected mitotic figures in endometriotic lesions (19.4 vs. 21.9 years, cf. Table 2 ).

Significantly more lesions showed mitotic figures in the group of women with deep infiltrating endometriosis (p < 0.001), ovarian endometrioma (p = 0.012) and infertility (p = 0.049). Mitotic figures and countable mitotic rates were more common in women with multiple endometriotic lesions (p < 0.001). Surgery was performed in the majority of cases via laparoscopy (91.51%).

Our results showed that there was no significant difference with regard to the presence of mitotic figures in the biopsies of women undergoing concurrent hormonal treatment at the time of surgery compared to women without endocrine treatment (p = 0.210). Forty-nine women were treated with combined oral contraceptives, 12 (24.5%) of whom had mitotic activity. Twenty-six patients took progestin only pills, mainly dienogest (n = 19), and three of them had mitotic activity (15.8%). Only one woman was treated with long-acting agonists of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH); no mitosis was detected in this woman. In the group receiving endocrine treatment, no difference was detected with regard to different medications (p = 0.793).

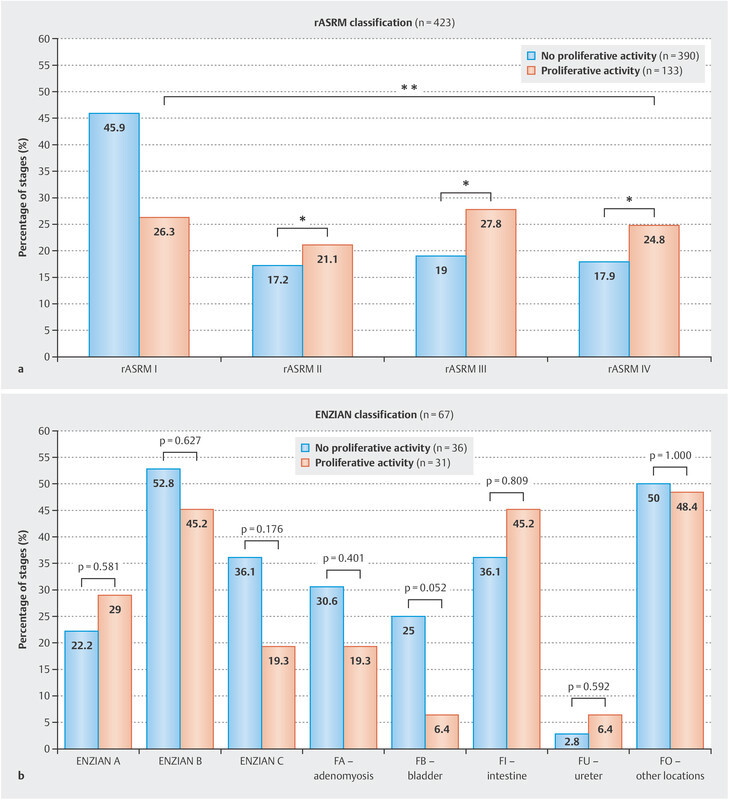

The percentages for the different stages based on the rASRM and ENZIAN scores for the groups with inactive and active proliferation are shown in Fig. 2 a and b . rASRM stages differed significantly between the two subgroups (p = 0.001). In spite of the higher occurrence of deep infiltrating endometriosis, the distribution of the lesions classified using the ENZIAN score does not show significant differences ( Fig. 2 b ).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of stages using the rASRM ( a ) and the ENZIAN score ( b ) in patients without and with detected mitotic figures as a marker of proliferative activity.

Discussion

Since the first description of mitotic figures in endometriotic lesions 8 , 9 only a few studies have been published on the topic of active proliferation in endometriotic lesions. The detection of mitotic figures as a marker of active proliferation in cancer cells after H & E staining is a standardized procedure 18 . Assessment is easy to perform without further staining or additional costs. Usually, 10 HPF are controlled and the number of mitotic figures is counted and documented. It appears that proliferative cellular activity does not change during the menstrual cycle in the ectopic endometrial tissue of women with endometriosis 17 . Nisolle et al. identified the mitotic rate as a histological marker for the intraoperative appearance of endometriotic lesions during surgery and as a morphological criterion for typical and atypical lesions 17 . The mitotic rate was a histological correlate for the macroscopic appearance of proliferation. In our study, we defined one mitotic figure and more in 10 HPFs as a sign of active cellular proliferation. In this retrospective analysis of clinical data from one single center, we examined the correlation between baseline characteristics and the presence of mitotic figures in the tissue of endometriotic lesions from more than 500 women.

The presence of mitotic figures had a significant additional diagnostic value with regard to the severity of endometriosis. After comparing the characteristics of women in our two subgroups, we found a statistically significant higher risk of severe endometriosis, with higher rASRM stages and deep infiltrating endometriosis, in the group with confirmed mitotic figures.

No statistically significant differences were seen between the two groups with regard to medical history, mean age at surgery, age at onset of menarche, menstrual cycle, or typical endometriosis-associated symptoms. The study shows the representative clinical baseline data of women with endometriosis, which were comparable to former studies on the clinical characteristics of endometriosis 18 , 19 , 20 . Interestingly, we found a statistically significant difference with regard to the interval between onset of menarche and surgery as a surrogate marker for reproductive lifespan and mitotic rate, with shorter reproductive lifespan in women with higher rates. It could be hypothesized that a longer reproductive lifespan with a longer cumulative exposure to estrogen may be correlated with active cellular proliferation. But our results suggest that endometriosis is diagnosed significantly earlier in women with active proliferative disease.

According to current guidelines and clinical algorithms, the indication for surgery is usually based on three indicators: pain, infertility, and clinical signs of endometriosis 21 . In our study, pain was the main reason for surgery significantly more often in the subgroup of women with detected mitotic figures, which corresponded to more advanced stages of endometriosis. Although detection of mitotic figures correlated with clinical stage and especially with deep infiltrating endometriosis, no significant difference was seen with regard to overall clinical symptoms ( Table 2 ). This may be explained by the high variability of symptoms. The results of studies investigating endometriosis-related pain and clinical staging or localization are conflicting. In an Italian study with 1000 patients, Vercellini et al. reported a higher severity of pain symptoms in patients with higher rASRM stages 22 . In contrast, a study by the US-American group of Sinai et al. with a similar sample size found that women with lower rASRM stages (I – II) suffered more frequently from dyspareunia. There were no differences with regard to other symptoms between the group with low rASRM stages and the group with a high rASRM stage 19 . The heterogenous clinical symptoms of endometriosis may explain why our study did not find any statistical differences in the mitotic rate with regard to most symptoms. A prospective multicenter study evaluating longitudinal clinical data in combination with repeated standardized pain questionnaires might find statistical differences. Women with symptoms of infertility have higher stages of endometriosis after an invasive diagnosis 20 , 24 .

There was no significant difference in the number of women with adenomyosis and typical clinical symptoms of dysmenorrhea and abnormal uterine bleeding in the groups with and without active proliferation (p = 0.752). Adenomyosis is a highly proliferative disease of the uterus, and higher Ki-67 cell indices were found in uterine myometrial tissue 25 . Nevertheless, we calculated the cellular proliferative rate for adenomyosis and endometriotic tissue.

The strengths of this study are the large sample size and the detailed information on symptoms, reproductive health and medical history. Although the data was collected retrospectively, information about the extent of disease was obtained from surgical records, and staging of the disease was standardized. The study was performed in a single certified endometriosis center. While this is a strength, it may also lead to a selection bias with a tendency to higher stages. This can be seen in the percentage of women with deep infiltrating endometriosis in our study (19.0%). A recent publication reported a lower percentage (14.4%) of deep infiltrating endometriosis in patients with endometriosis 26 . A detailed analysis of ENZIAN stages and the distribution of endometriotic lesions in deep infiltrating endometriosis did not show significant differences.

The long-term follow-up is of special interest in view of the data on recurrence and the possible development of cancerous lesions. The lack of follow-up is one of the limitations of this study. A prospective follow-up study is currently being planned.

The presence of mitotic figures as a marker of severe disease could be an additional factor when recommending that women receive a longer follow-up and treatment to prevent recurrence 27 . We propose that women in whom mitotic figures are detected should have shorter postoperative follow-up intervals and that the time to pregnancy in cases of infertility should be shortened. Assisted reproductive techniques could be proposed earlier for women with confirmed mitotic figures.

Although this retrospective study did not find an association between the mitotic rate and recurrence, further prospective validating studies could clarify the prognostic value of mitotic figures and their impact on recurrence.

Endometriosis can lead to epithelial cancer, although the underlying mechanisms are still not understood 28 . The mitotic rate could serve as an early prognostic marker for women who have a higher risk of developing endometriosis-associated cancer and who therefore require intensified long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

The mitotic rate can be used as a simple additional histological assessment for endometriosis. Histology is already routinely used to investigate endometriosis, and this approach would not need additional training of the pathologist or additional staining of the specimen. We can confirm that the mitotic rate can be an effective diagnostic tool in women with more severe endometriosis based on their surgical findings. Our data strongly suggest that further studies should be carried out to investigate the association between mitotic rate and the rate of recurrence after the initial diagnosis of endometriosis and pregnancy outcomes in women with infertility.

Funding

No funding was used for the study or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Giudice L C, Kao L C. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364:1789–1799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicolaus K, Reckenbeil L, Bräuer D. Cycle-related diarrhea and dysmenorrhea are independent predictors of peritoneal endometriosis, cycle-related dyschezia is an independent predictor of rectal involvement. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2020;80:307–315. doi: 10.1055/a-1033-9588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjorkman S, Taylor H S. MicroRNAs in endometriosis: biological function and emerging biomarker candidates. Biol Reprod. 2019;100:1135–1146. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioz014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moustafa S, Burn M, Mamillapalli R. Accurate diagnosis of endometriosis using serum microRNAs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;22:5570–5.57E13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology . Dunselman G A, Vermeulen N, Becker C. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29:400–412. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burghaus S, Schäfer S D, Beckmann M W. Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis. Guideline of the DGGG, SGGG and OEGGG (S2k Level, AWMF Registry Number 015/045, August 2020) Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2021;81:422–446. doi: 10.1055/a-1380-3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.for the QS Endo Working Group of the Endometriosis Research Foundation (SEF) . Zeppernick F, Zeppernick M, Janschek E. QS ENDO Real – A Study by the German Endometriosis Research Foundation (SEF) on the Reality of Care for Patients with Endometriosis in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2020;80:179–189. doi: 10.1055/a-1068-9260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nisolle-Pochet M, Casanas-Roux F, Donnez J. Histologic study of ovarian endometriosis after hormonal therapy. Fertil Steril. 1988;49:423–426. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59766-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nisolle M, Casanas-Roux F, Anaf V. Morphometric study of the stromal vascularization in peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:681–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yadav K S, Gonuguntla S, Ealla K K. Assessment of interobserver variability in mitotic figure counting in different histological grades of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2012;13:339–344. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barry M, Sinha S K, Leader M B. Poor agreement in recognition of abnormal mitoses: requirement for standardized and robust definitions. Histopathology. 2001;38:68–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahyaoglu I, Kahyaoglu S, Moraloglu O. Comparison of Ki-67 proliferative index between eutopic and ectopic endometrium: a case control study. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;51:393–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukunaga M, Nomura K, Ishikawa E. Ovarian atypical endometriosis: its close association with malignant epithelial tumours. Histopathology. 1997;30:249–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.d01-592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeAngelo C, Tarasiewicz M B, Strother A. Endometriosis: A malignant fingerprint. J Cancer Res Ther Oncol. 2020;8:206. doi: 10.17303/jcrto.2020.8.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817–821. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas D, Chvatal R, Habelsberger A. Preoperative planning of surgery for deeply infiltrating endometriosis using the ENZIAN classification. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;166:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nisolle M, Casanas-Roux F, Donnez J. Immunohistochemical analysis of proliferative activity and steroid receptor expression in peritoneal and ovarian endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:912–919. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis D, Ohgaki H, Wiestler O, Cavenee W. Lyon: WHO Press; 2016. WHO Classification of Tumours of the central nervous System. 4th ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinaii N, Plumb K, Cotton L. Differences in characteristics among 1,000 women with endometriosis based on extent of disease. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbas S, Ihle P, Köster I. Prevalence and incidence of diagnosed endometriosis and risk of endometriosis in patients with endometriosis-related symptoms: findings from a statutory health insurance-based cohort in Germany. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;160:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fauconnier A, Chapron C, Dubuisson J-B. Relation between pain symptoms and the anatomic location of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:719–726. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kho R M, Andres M P, Borrelli G M. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: Comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:102–110. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:266–271. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wimberger P, Grübling N, Riehn A. Endometriosis – A Chameleon: Patientsʼ Perception of Clinical Symptoms, Treatment Strategies and Their Impact on Symptoms. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2014;74:940–946. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nepomnyashchikh L M, Lushnikova E L, Molodykh O P. Immunocytochemical analysis of proliferative activity of endometrial and myometrial cell populations in focal and stromal adenomyosis. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2013;155:512–517. doi: 10.1007/s10517-013-2190-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Audebert A, Petousis S, Margioula-Siarkou C. Anatomic distribution of endometriosis: A reappraisal based on series of 1101 patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;230:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Findeklee S, Radosa J C, Hamza A. Treatment algorithm for women with endometriosis in a certified Endometriosis Unit. Minerva Ginecol. 2020;72:43–49. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4784.20.04490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bulun S E, Wan Y, Matei D. Epithelial Mutations in Endometriosis: Link to Ovarian Cancer. Endocrinology. 2019;160:626–638. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]