Abstract

Many studies have confirmed that the CENPK gene regulates the progression of cancers, but its specific molecular mechanism remains unidentified, as does its significance in the analysis of human cancers. We specify a comprehensive genomic architecture of the CENPK gene associated with the tumor immune microenvironment and its clinical relevance across a broad spectrum of solid tumors. Statistics from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) of over 30 solid tumors were examined. CENPK was expressed differentially in several cancers and is significantly associated in survival outcomes, with higher CENPK signifying a worse prognosis for ACC, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, MESO, and SARC. We further examined its clinical relevance with tumor immunogenic features. The expression level of CENPK was not only strongly linked to the tumor infiltration, such as tumor-infiltrating immune cells and immune scores but also linked to microsatellite instability and tumor mutation burden in diverse cancers (P<0.05). I mmune markers such as TNFRSF14 and VSIR were highly expressed on over 20 kinds of human cancer and mismatch repair genes like MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 were positively related with CENPK expression. Moreover, the methyltransferases and functional pathways also seem to have a relationship with the CENPK. CENPK is expected to be a guiding marker gene for clinical prognosis and tumor personalized immunotherapy.

Keywords: Pan-cancer, prognostic bio-maker, CENPK, immune infiltration, clinical significance

Introduction

With the progressively profound description of cancer and sensitivity of its detection, it is a leading cause of death. The greatest challenge now is better cancer treatment, which remains flawed and not appropriate for all patients’ circumstances. Analysis of molecular aberrations across multiple cancer types, known as pan-cancer analysis, draws a comprehensive picture of commonalities, differences, and emerging themes in key biologic processes among tumor types [1]. Previous pan-cancer analysis has found characteristics that might contribute to reveal subtypes and direct sensitive therapies from the genomic landscape, exploring certain oncogenic pathway-related genes [2-5]. Andrew et al. has presented the data on over 18,000 cases across 39 malignancies. FOXM1 regulatory network was recognized as a major predictor of adverse outcome and KLRB1 as a favorable prognostic gene [6]. A study on prognostic lncRNA investigated SCAT7 in multiple cancer types. It interacted with hnRNPK/YBX1 complex and influenced cancer cell indications through the regulation of FGF/FGFR and its downstream PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways [7]. According to a recent article, m6A regulators and their interactive genes such as BCL9L, impact the outcome of different cancers and have the potential to enlighten the design of adjuvant treatments [8]. An additional retrospective study of transcriptional profiles of 20,752 samples of 25 types of cancer was achieved to claim that KDM8, acting on the HNF4A pathway, was a tumor suppressor down-regulated in the liver and pancreatic tumors and an independent prognostic factor [9].

There is growing evidence that kinetochore dysregulation or dysfunction is strongly related to the growth of cancer. Human centromere protein K is a protein encoded by the CENPK gene, playing a crucial role in the progression of tumors through regulating the separation of chromosomes [10,11]. Overexpression of CENPK has been demonstrated in various human malignancies including ovarian cancer [12] and breast cancer [13]. Our results showed that the CENPK-YAP1-EMT axis plays a critical part in regulating HCC malignant progression, making this axis a therapeutic target for HCC [14]. Lately, with the deepening of explorations of CENPK, the role of CENPK in promoting tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis were recognized in lung adenocarcinoma [15], differentiated thyroid carcinoma [16], and tongue squamous cell carcinoma [17]. Considering that CENPK is a new oncogene candidate, the addition of insightful integrated analyses from genomic and epigenomic platforms is necessary.

In our study, we projected to study the expression of CENPK and its prognostic significance in human tumors. The connection of CENPK with tumor infiltration, immune score, neoantigens, microsatellite instability (MSI), and tumor mutational burden (TMB) were analyzed for numerous types of cancer to probe for immunogenicity. Likewise, we also explored the association among CENPK gene mutation, mismatch repair-related genes, and methyltransferases. To provide a comprehensive genomic architecture of CENPK, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was explored on the principal functional pathways across different cancers.

Materials and methods

Data sets and collecting process

The data sets of patients were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/). Our study collected over 20,000 initial tumor samples and corresponding para-tumor samples of 28 kinds of carcinoma. The data from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) project were sorted from the website (http://www.broadinstitute.org/ccle). For this study, only the public raw data were utilized, avoiding authorization from the Committee of Ethics. This study obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (approval no. 2018-40).

Differential expression of CENPK and screening of cancers related to survival

The data on the CENPK gene expressed in carcinomatous and adjacent normal samples were gained from the TCGA. Kruskal-Wallis test and univariate Cox analysis helped us confirm the differential expression of CENPK in various carcinomas. We also tried to evaluate the correlation between CENPK expression level and some clinical features utilizing a univariate Cox analysis. Statistical significance was set at P-value =0.05. Kaplan-Meier (KM) analysis was applied to associate the disease-free interval (DFI), disease-specific survival (DSS), overall survival (OS), and progression-free interval (PFI) with CENPK gene expression level in various cancers. The difference between CENPK gene expression and survival status by assessed by log-rank test. Visually, we drew a survival-associated forest plot.

Tumor immunity and CENPK mutation

The tumor immunity estimation resource (TIMER, https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) is regarded as a complete method for a systematic study of the immune infiltration of several kinds of carcinoma [18]. In TIMER, a de-convolution statistical technique is applied to calculate the immune cell level of tumor infiltration based on gene expression data [19]. By the TIMER algorithm, we checked the correlation among CENPK expression levels and six different levels of immune infiltration cells (B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils). We also investigated the co-expression situation across cancer types. Using the foundation of ssGSEA, we gained a stromal score and immune score by ESTIMATE (Estimation of STromal and Immune cells in Malignant Tumor tissues using Expression data) to intuitively conclude the correlation with CENPK gene expression. We made a comparison between CENPK expression and neoantigen count among numerous cancers. Then, we examined the tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) corresponding to CENPK gene expression. To further explore the gene-regulating mechanism of oncogenesis, we acknowledged the CENPK mutation and the relationship with mismatch repair-related genes and methyltransferases in many cancers.

Gene set enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichment investigation was similarly accomplished applying GSEA (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) software v2.2.1 (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). When the number of random sample arrangements is 100 and the significance threshold is P<0.05, R software (http://r-project.org/) and Bioconductor (http://bioconductor.org/) are applied for visualizing our results.

Statistical methods

Wilcoxon log-rank test was applied to assess the noticeably increased amount of gene expression z-scores for carcinogenic tissues, as compared to adjacent normal tissues. The variation in CENPK expression between various cancer periods was assessed by Kruskal-Wallis test. Survival was investigated by the log-rank test, Cox proportional hazards regression model, and KM curves. For the correlation analysis, Spearman’s test was applied.

Results

Pan-cancer expression landscape of CENPK

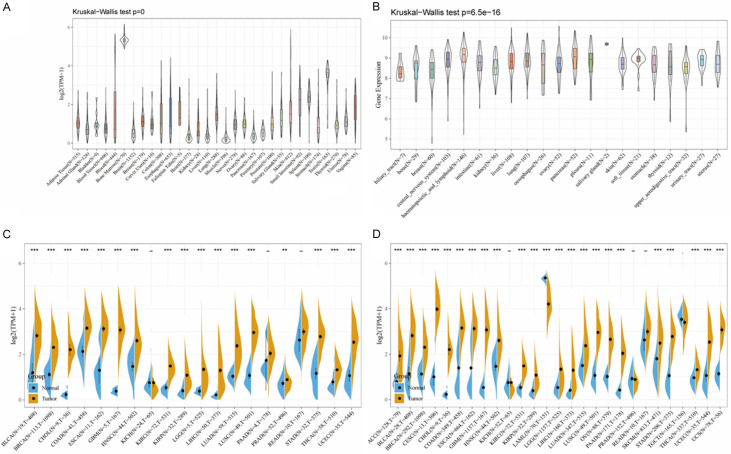

Examining the outcomes of cancer patients in GTEX (Genotype-Tissue Expression) and CCLE (Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia), we found the CENPK gene expressed in diverse normal tissues, highly expressed in bone marrow and testis but with low levels in heart, liver, and muscle (Figure 1A, 1B). In cancer we found significantly upregulated CENPK expression between tumor samples versus paired normal samples, except KICH, PAAD, and READ in GETX database and KICH, PRAD, READ, and TGCT in the CCLE database (Figure 1C, 1D). Combing GTEX and CCLE analysis results, CENPK was constantly up-regulated in most cancer-type samples, except KICH, PAAD, and READ.

Figure 1.

CENPK expression level in human pan-cancer analyses. A. Expression of CENPK in 31 tissues in GTEX. B. Expression of CENPK in 21 tissues in CCLE. C. Level of CENPK in TCGA. D. Expression level in TCGA combined with GTEX. The blue and yellow bar graphs indicate normal and tumor tissues, respectively. *P<.05; **P<.01; ***P<.001.

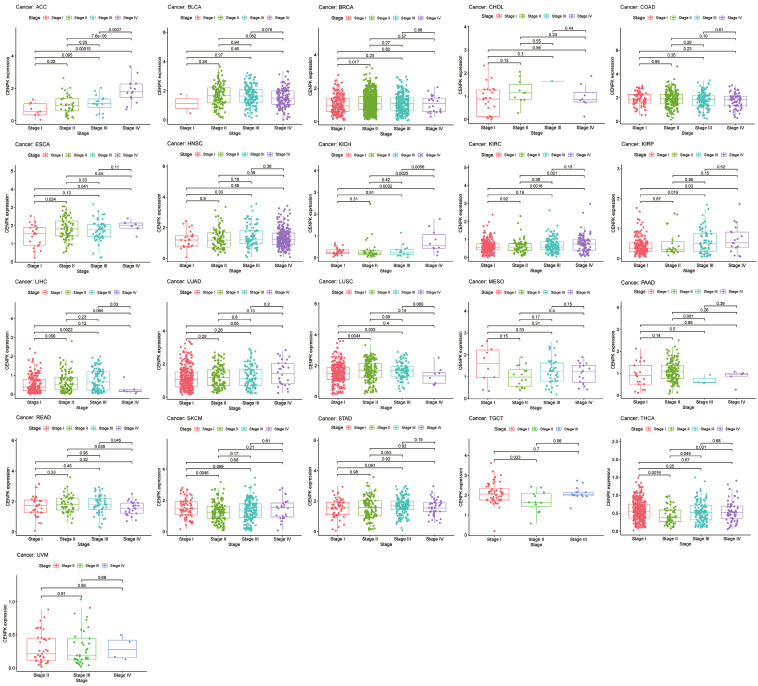

Correlation between CENPK expression and clinical features

To broadly learn about the CENPK expression in multiple cancers, we examined the gene expression level corresponding to clinical cancer stage and age of onset. As shown in Figure 2, the vast majority of malignant tumors we studied had statistical relevance between CENPK expression and clinical stage among 21 common cancers (P<0.05). CENPK is up-regulated with stage in ACC, BRAC, ESCA, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LUAD, and THCA, whereas it is down-regulated according to stage in READ, SKCM, and TGCT. Interestingly, in the analysis of LIHC and LUSC, we saw patients with early-stage highly expressed CENPK, but it was expressed at low levels in an advanced stage. CENPK gene remained stable in BLCA, CHOL, COAD, HNSC, MESO, STAD, and UVM regardless of stage. Taking 65 years old as a dividing line, CENPK expression level differed in 6 of 28 common cancers. They were ESCA, LAML, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, and PAAD (P<0.05, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Box plot shows the association of CENPK expression with age for cancers.

Figure 3.

Box plot shows the association of CENPK expression with pathologic stages for cancers.

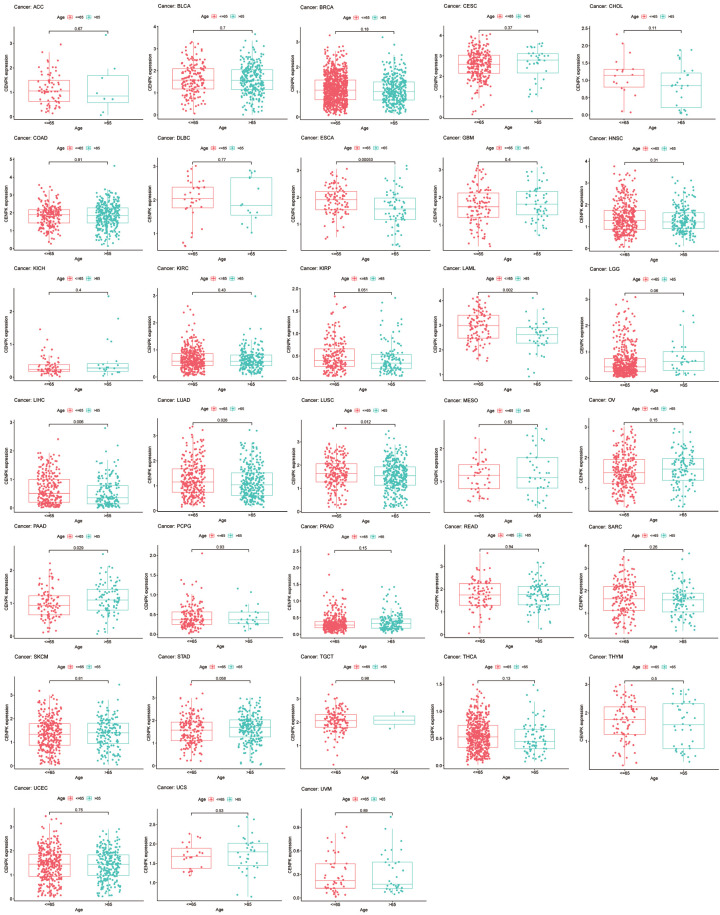

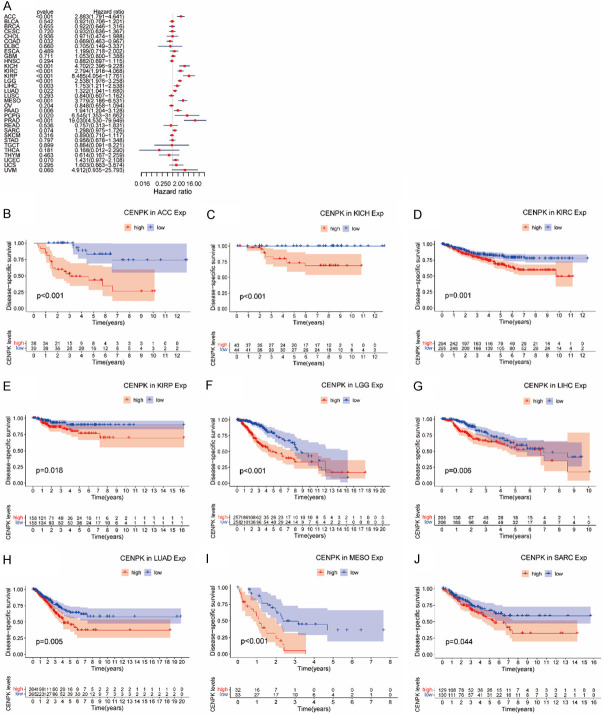

Screening of CENPK survival-linked cancers

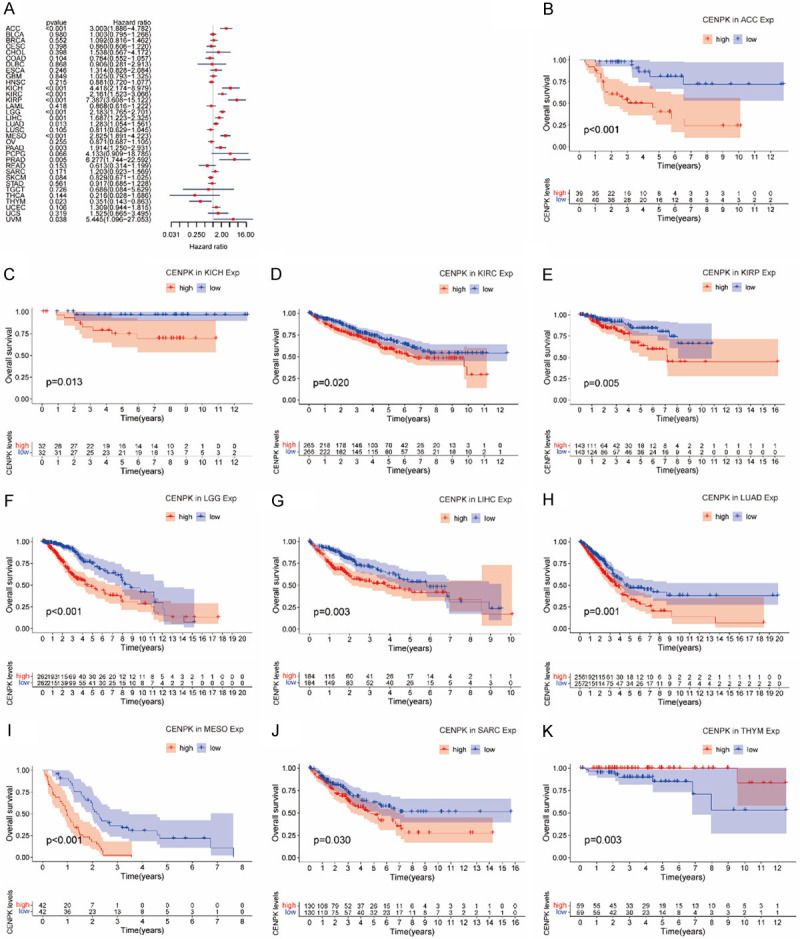

To examine the prognostic association of CENPK gene, we made Cox regression analysis and KM curves of some survival indexes, including OS (overall survival), DSS (disease-specific survival), DFI (disease-free interval), and PFI (progression-free interval). In an OS study on 33 kinds of cancer, Cox regression demonstrated that higher expression of CENPK was a protective factor in ACC (P<0.001), KICH (P<0.001), KIRC (P<0.001), KIRP (P<0.001), LGG (P<0.001), LIHC (P=0.001), LUAD (P=0.013), MESO (P<0.001), PAAD (P=0.003), PRAS (P=0.005) and UVM (P=0.038), but a risk factor in THYM (P=0.023, Figure 4A). Correspondingly, the KM curves displayed that CENPK had a protective role in overall survival of ACC (P<0.001, Figure 4B), KICH (P=0.013, Figure 4C), KIRC (P=0.02, Figure 4D), KIRP (P=0.005, Figure 4E), LGG (P<0.001, Figure 4F), LIHC (P=0.003, Figure 4G), LUAD (P=0.001, Figure 4H), MESO (P<0.001, Figure 4G) and SARC (P=0.03, Figure 4J), but was a driving force in THYM (P=0.003, Figure 4K).

Figure 4.

Association of CENPK expression with patient overall survival (OS). A. Forest plot shows the relationship of CENPK expression with patient OS. B-K. Kaplan-Meier analyses show the association between CENPK expression and OS for cancers.

Using the patients with DSS data, we studied 32 kinds of cancer. The results of analysis showed that CENPK works as a predisposing element in ACC (P<0.001), KICH (P<0.001), KIRC (P<0.001), KIRP (P<0.001), LGG (P<0.001), LIHC (P=0.003), MESO (P<0.001), PAAD (P=0.006), PCPG (P=0.02) and PRAD (P<0.001), but a risk factor in COAD (P=0.032) and LUAD (P=0.022) as illustrated in Figure 5A. Patients with lower expression of CENPK tended to have better DSS outcome than those with higher CENPK expression in ACC (P<0.001, Figure 5B), KICH (P<0.001, Figure 5C), KIRC (P=0.001, Figure 5D), KIRP (P=0.018, Figure 5E), LGG (P<0.001, Figure 5F), LIHC (P=0.006, Figure 5G), LUAD (P=0.005, Figure 5H), MESO (P<0.001, Figure 5I) and SARC (P=0.044, Figure 5J).

Figure 5.

Association of CENPK expression with patient disease-specific survival (DSS). A. The forest plot shows the relationship of CENPK expression with DSS. B-J. Kaplan-Meier analyses show the association between CENPK expression and DSS for cancers.

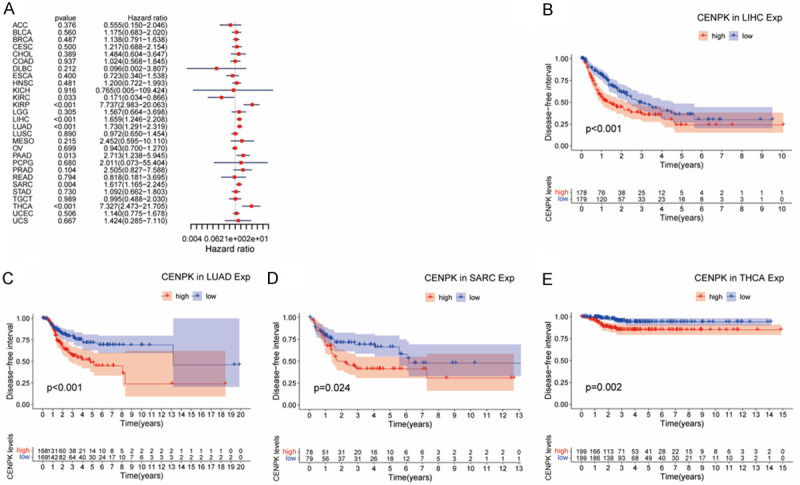

Cox regression analysis of DFI disclosed that higher CENPK expression was a predisposing factor in KIRC (P=0.033), KIRP (P<0.001), LIHC (P<0.001), LUAD (P<0.001), PAAD (P=0.013), SARC (P=0.004) and THCA (P<0.001, Figure 6A), involving 28 types of tumors. Consistently, KM curves suggested patients with higher CENPK expression had shorter disease-free intervals in LIHC (P<0.001, Figure 6B), LUAD (P<0.001, Figure 6C), SARC (P=0.024, Figure 6D), and THCA (P=0.002, Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

Association of CENPK expression with patient disease-free interval (DFI). A. The forest plot shows the relationship of CENPK expression with DFI. B-E. Kaplan-Meier analyses show the association between CENPK expression and DFI for cancers.

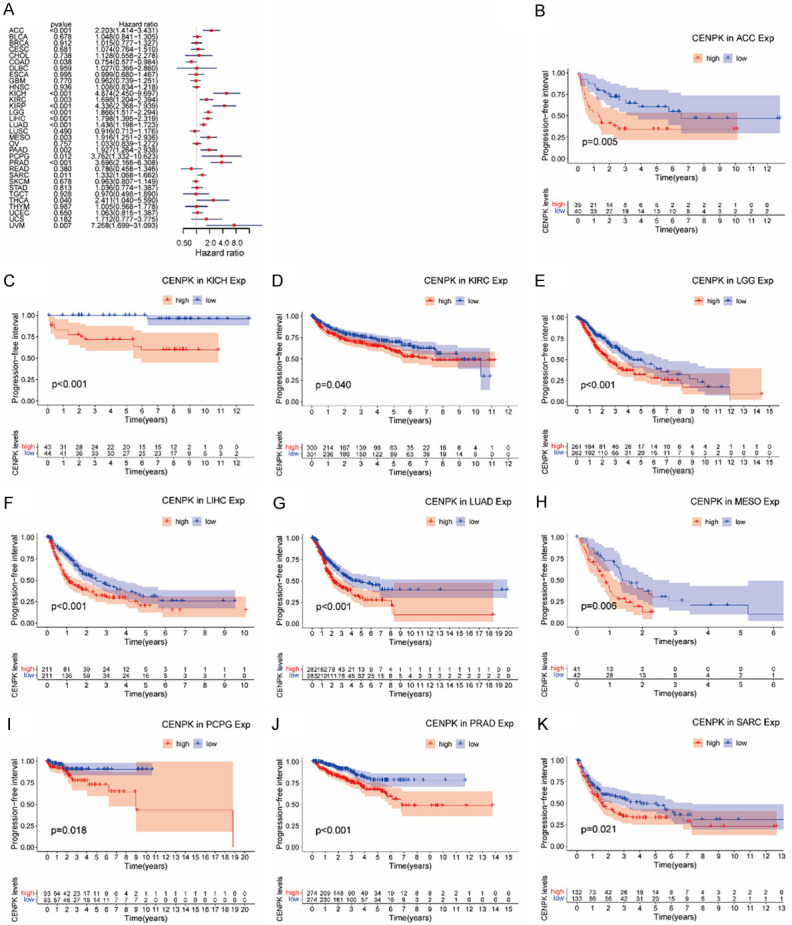

In the PFI analysis involving 32 cancers, we found that CENPK gene played a predisposing role in the progress of ACC (P<0.001), COAD (P<0.001), KICH (P<0.001), KIRC (P<0.001), KIRP (P<0.001), LGG (P=0.038), LIHC (P<0.001), LUAD (P<0.001), MESO (P=0.003), PAAD (P=0.002), PCPG (P=0.012), PRAD (P<0.001), SARC (P=0.011), THCA (P=0.04) and UVM (P=0.007, Figure 7A). A large majority of cancers were predisposed to by CENPK except COAD, where CENPK acted as a risk factor (P=0.038, Figure 7A). KM analysis showed a negative influence of CENPK in ACC (P=0.005, Figure 7B), KICH (P<0.001, Figure 7C), KIRC (P=0.04, Figure 7D), LGG (P<0.001, Figure 7E), LIHC (P<0.001, Figure 7F), LUAD (P<0.001, Figure 7G), MESO (P=0.006, Figure 7H), PCPG (P=0.018, Figure 7I), PRAD (P<0.001, Figure 7J), and SARC (P=0.021, Figure 7K).

Figure 7.

Association of CENPK expression with patient progression-free interval (PFI). A. The forest plot shows the relationship of CENPK expression with PFI. B-K. Kaplan-Meier analyses show the association between CENPK expression and PFI for cancers.

CENPK expression was linked to the level of immune infiltration and immune markers

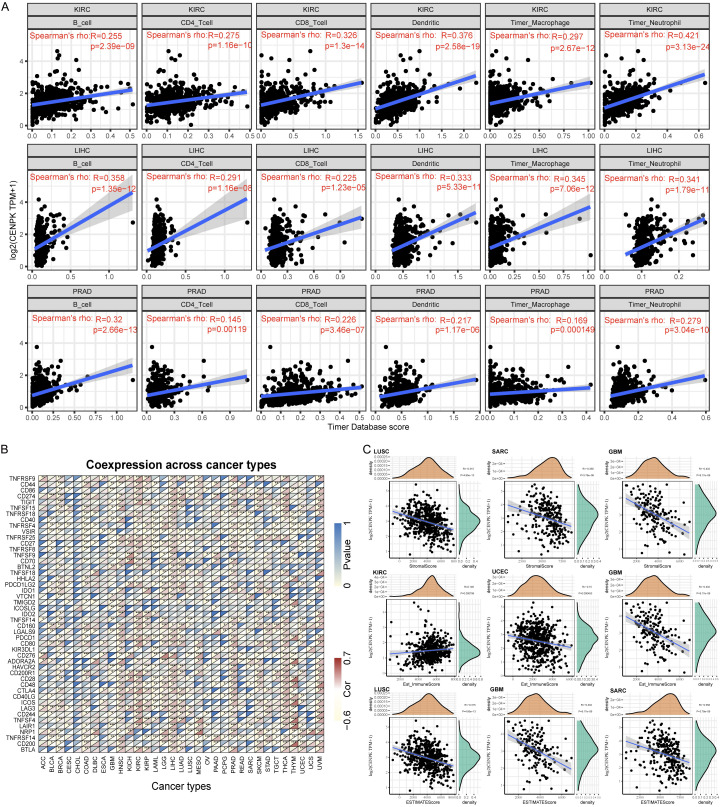

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) have become a crucial predictive indicator for prognostic tumors and a promising guide of adjuvant therapy. So, we further explored the micro-environment of the tumors. We gathered immune cell infiltrate data in patients with KIRC, LIHC, and PRAD from the Timer Database. Spearman analysis demonstrated a distinct positive linear dependence in CENPK expression and six immune cells (B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils, P<0.001, Figure 8A). These immune cells were stimulated as the CENPK expression level increased. Then we analyzed the co-expression of some acknowledged biomarkers in 33 kinds of cancers as presented in Figure 8B. We discovered that CENPK was associated with the expression level of several immune markers in roughly 20 cancers, including TNFRSF14 in BLCA, BRCA, COAD, DBLC, GBM, HNSC, KIRP, LAML, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, MESO, OV, PAAD, PCPG, PRAD, READ, SKCM, STAD, TGCT, THCA, THYM, and UCEC; VSIR in BLCA, BRCA, COAD, ESCA, GBM, KIRP, LAML, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, LUSC, MESO, OV, PCPG, PRAD, READ, SARC, STAD, TGCT, THYM, and UCEC; CD276 and LAG3 in 19 cancers.

Figure 8.

CENPK expression is correlated with cancer immunity. A. TIMER predicts that the CENPK level is related to the degree of immune infiltration within KIRC, LIHC and PRAD. B. The heat map represents the relationship between 47 immune checkpoint genes and gene expression of CENPK. For each pair, the right triangle is colored to represent the P-value; the left triangle is colored to indicate the Spearman correlation coefficient. *P<.05; **P<.01; ***P<.001. C. Relationship between gene expression with the StromalScore, Est_ImmuneScore and ESTIMATEScore.

Correlation analysis with immune score

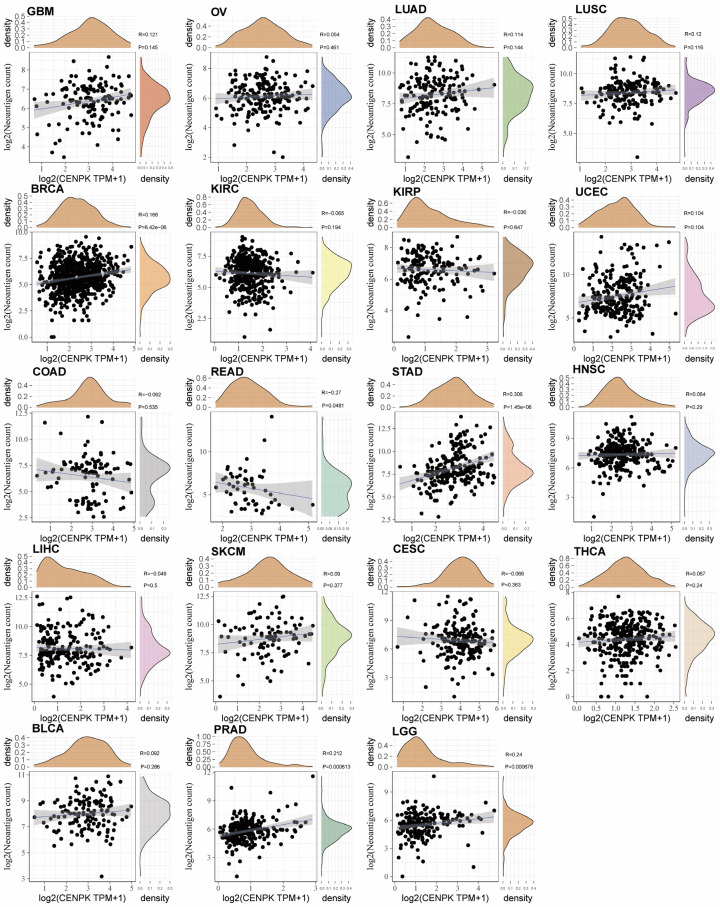

We furthermore utilized the ssGESA method to calculate the Stromal score and Immune score in Figure 8C, suggesting a negative correlation of CENPK and Stromal Score in LUSC, SARC, and GBM (P<0.001); negative correlation of CENPK and Immune score in UCEC and GBM (P<0.001); but a positive correlation in KIRC (P<0.001). ESTIMATE score was obtained by combining the Stromal score and Immune score, showing that CENPK gene expression was negatively correlated with ESTIMATE score in LUSC, SARC, and GBM (P<0.001, Figure 8C). These data spoke volumes for the influence of CENPK in regulating cancer immune response. Figure 9 shows that CENPK was positively correlated with neoantigens in BRAC (P<0.001), STAD (P<0.001), PRAD (P=0.00061), and LGG (P=0.00067), but negatively correlated with READ (P=0.048). No relationship with neoantigens was seen in GBM, OV, LUAD, LUSC, KIRC, KIRP, UCEC, COAD, HNSC, LIHC, SKCM, CESC, THCA, or BLCA.

Figure 9.

Relationship between the number of neoantigens and gene expression in each tumor.

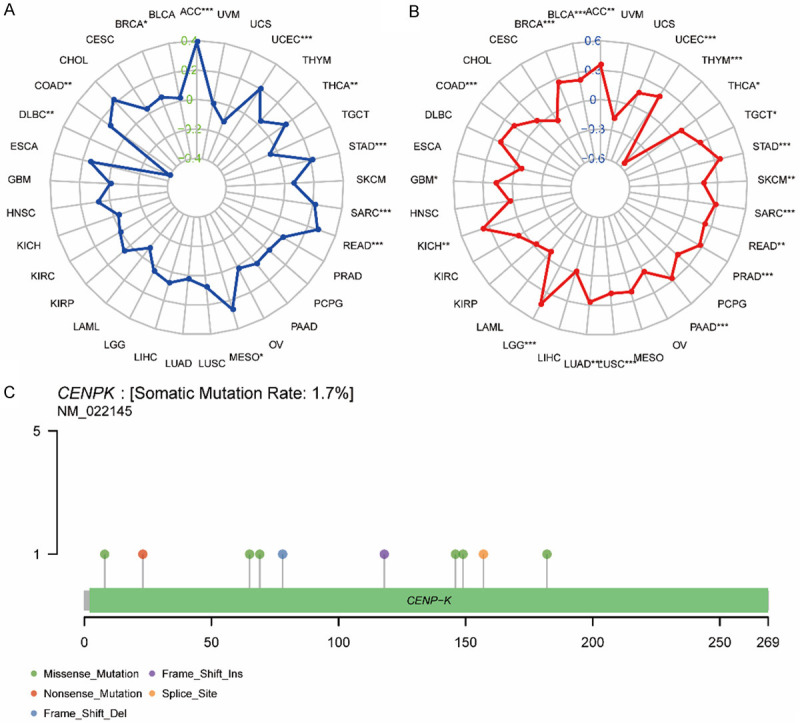

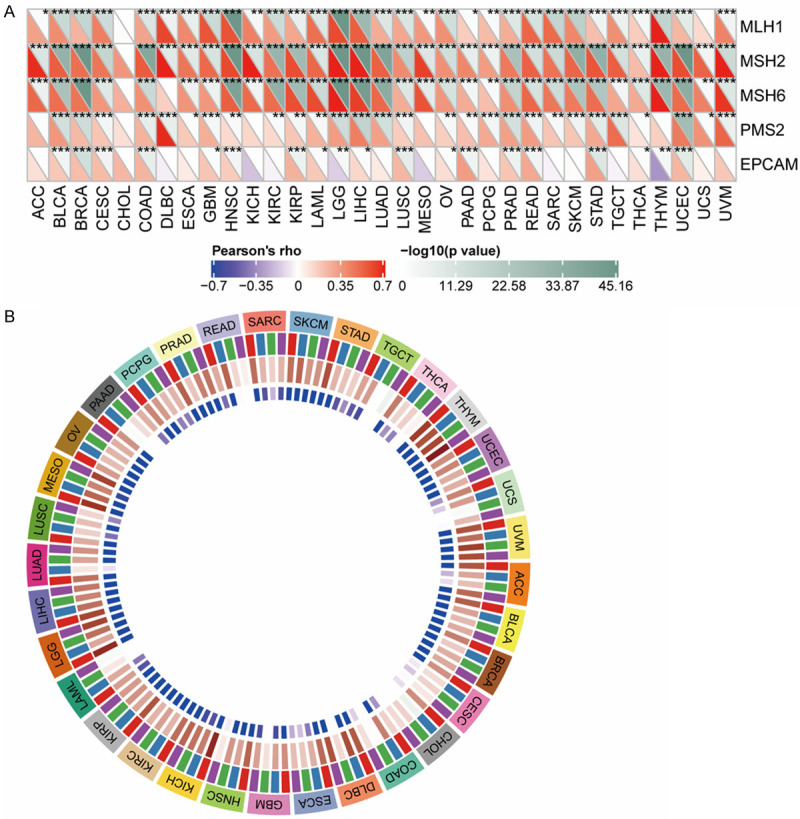

Genetic analysis

To unlock the potential of the CENPK gene in clinical immune therapy, we tried to analyze TMB and MSI. The results displayed in Figure 10A disclosed that CENPK level was positively associated with TMB in ACC (P<0.0001), UCEC (P<0.0001), THCA (P<0.001), STAD (P<0.0001) SARC (P<0.0001), READ (P<0.0001), MESO (P<0.01), COAD (P<0.001) and BRAC (P<0.01), but negatively associated with MTB in DLBC (P<0.001). MSI analysis shown in Figure 10B illustrated that the CENPK level was positively associated with MSI in ACC (P<0.001), UCEC (P<0.0001), TGCT (P<0.01), STAD (P<0.0001), SKCM (P<0.001), SARC (P<0.0001), READ (P<0.001), PRAD (P<0.0001), PAAD (P<0.001), LUSC (P<0.0001), LUAD (P<0.0001), LGG (P<0.0001), KICH (P<0.001), GBM (P<0.01), COAD (P<0.0001), BRAC (P<0.0001) and BLCA (P<0.0001), but negatively correlated with THCA (P<0.01). We further concluded that CENPK gene expression is much more likely to imply higher TMB or TSI in the vast majority of tumors and is a promising target gene for effective immune therapy. Figure 10C shows the number, type, and site of CENPK mutations. The gene database showed that the somatic mutation rate of CENPK is 1.7%, which includes missense mutations, frameshift insertion, nonsense mutations, splice sites, and frameshift deletion. From the heatmap describing the relationship with CENPK and some familiar mismatch repair-related genes, we could find MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 had a comprehensive relationship with all the cancers we studied except CHOL (P<0.01, Figure 11A). PMS2 and EPCAM were connected to most of the 33 cancers. Numerous previous studies confirmed that gene methylation is closely related to malignant variance and clinicopathologic features, including lymphatic metastasis, tissue invasion, and multiple lesions. As illustrated in Figure 11B, we made a correlational analysis of four acknowledged methyltransferases in all types of cancer. CENPK expression had a strong connection with methyltransferases in most cancers. A weaker correlation with one or two methyltransferases and CENPK was shown in TGCT, THCA, UCS, CESC, CHOL, COAD, LAML, PAAD and READ. We conclude that the CENPK gene has an association with mismatch repair-related genes and methyltransferases, regulating malignant cell progression. Our hypothesis is that CENPK promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis by suppressing mismatch repair-related genes induced by methyltransferases. To confirm this assumption, it needs additional study integrating more evidence of causality.

Figure 10.

Correlation of CENPK expression with TMB and MSI and mutation pattern of CENPK gene in tumor samples. A. The radar chart displays the overlap between CENPK and TMB. The number represents the Spearman correlation coefficient. B. The radar chart displays the overlap between CENPK and MSI. The number represents the Spearman correlation coefficient. C. Mutation of CENPK in UCSC.

Figure 11.

Relationship between CENPK expression with MMRS and methyltransferase in various tumor samples. A. Relationship between CENPK expression and mutation of 5 MMRs genes. B. Relationship between 4 methyltransferases and CENPK expression.

Functional analysis

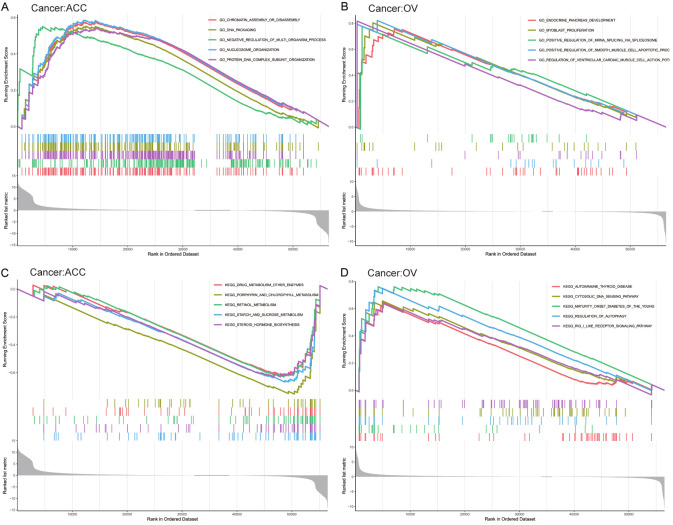

The biological consequences of CENPK expression were evaluated employing GSEA. In ACC, the obvious benefit of CENPK was presented in accordance GO (Gene Ontology) terms: GO_CHROMATIN_ASSEMBLY_OR_DISASSEMBLY, GO_DNA_PACKAGING, GO_NEGATIVE_REGULATION_OF_MULTI_-ORGANISM_PROCESS, GO_NUCLEOSOME_ORGANIZATION, and GO_PROTEIN_DNA_COMPLEX_SUBUNIT_ORGANIZATION (Figure 12A). The accordant KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) terms interestingly presented substantial reduction: KEGG_DRUG_METABOLISM_OTHER_ENZYMES, KEGG_PORPHYRIN_AND_CHLOROPHYLL_METABOLISM, KEGG_RETINOL_METABOLISM, KEGG_STARCH_AND_SUCROSE_METABOLISM, and KEGG_STEROID_HORMONE_BIOSYNTHESIS (Figure 12C). In OV, the obvious improvement of CENPK was presented in accordance GO terms: GO_ENDOCRINE_PANCREAS_DEVELOPMENT, GO_MYOBLAST_PROLIFERATION, GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_MRNA_SPLICING_VIA_SOLICEOSOME, GO_POSITIVE_REGULATION_OF_SMOOTH_MUSCLE_CELL_APOPTOTIC_PROCESS, and GO_REGULATION_OF_VENTRICULAR_CARDIAC_MUSCLE_CELL_ACTION (Figure 12B). The accordance KEGG terms also presented substantial improvement: KEGG_AUTOIMMUNE_THYROID_DISEASE, KEGG_CYTOSOLIC_ DNA_SENSING_PATHWAY, KEGG_MATURITY_ONSET_DIABETES_OF_THE_YOUNG, KEGG_REGULATION_OF_AUTOPHAGY, and KEGG_RIG_I_LIKE_RECEPTOR_SIGNALING_PATHWAY (Figure 12D).

Figure 12.

Enrichment results of the GO and KEGG pathways in the high expression group and the low expression group.

Discussion

Currently, the detection, monitoring, and treatment of oncological diseases are becoming more systematic, comprehensive, and individualized, attributed to the rapid development of medical technology and medical practitioners’ relentless exploration of the field of oncology. Nevertheless, the path to exploring more personalized and effective oncology treatments is limitless. CENPK is a subunit of a CENPH-CENPI-associated centromeric complex that targets CENPA to centromeres and is required for proper kinetochore function and mitotic progression. Wang et al. found that CENPK is aberrantly upregulated in HCC tumor tissues. CENPK-YAP1-EMT axis plays a critical role in regulating HCC malignant progression [20]. Overexpression of CENPK has been demonstrated in various human malignancies including ovarian cancer [12] and breast cancer [13]. Our results suggest that the CENPK-YAP1-EMT axis plays a critical role in regulating HCC malignant progression, indicating the role of this axis as a therapeutic target for HCC [14]. Our analysis was focused on the crucial role of the CENPK gene in the development of different cancers by carefully studying the data on various kinds of cancer with a large sample size from GTEX and CCLE. We first noticed the abnormal expression of CENPK in different tumors and various clinical features such as stage and age. Employing Cox and KM curve analyses, we found different expression of CENPK in different survival indicators, indicating CENPK as a promising prognostic element of certain malignancies. The result presented that higher CENPK signified a worse prognosis for ACC, KICH, KIRC, KIRP, LGG, LIHC, LUAD, MESO, and SARC.

Integrated treatment of tumors is always developing and the accessible managements are surgical operation, chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and targeted therapies. To help select a satisfactory treatment, immunotherapy is now a hot topic in oncology. Combination immunotherapy is an obvious strategy to pursue, aiming squarely on correcting the immunologic defects in the tumor microenvironment [21]. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) play a vital role in inducing a response to chemotherapy and refining clinical outcome in all types of malignancy [22]. In our investigation, we found CENPK could consistently stimulate all six types of immune cells (B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, dendritic cells, macrophages, and neutrophils) in KIRC, LIHC, and PRAD. Immune biomarkers also had some relationship with CENPK expression in approximately 20 kinds of cancers. TNRFSF14 is known to be a promotor in follicular lymphoma [22], signifying unfavorable clinical variables and a higher risk of transformation. Julija et al. proposed VSIR was a member of the B7 family of negative immune checkpoint regulators, related to good survival in mesotheliomas, especially the epithelioid type [23,24]. We discovered that TNFRSF14 and VSIR were highly expressed on over 20 kinds of human malignancies, implying CENPK may affect the immune response in these tumor types.

Specific gene mutations can predict prognosis and response to treatment. Neoantigens are antigens encoded by tumor-specific mutated genes, regarded to have a key role for neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy [25]. It was identified that higher somatic TMB and MSI were linked to improved efficiency with immunotherapy and better overall survival for most cancer histologies [26-29]. The mutations and loss-of-function of mismatch repair genes were the upstream reasons for MSI. In our report, CENPK was positively correlated with neoantigens in BRAC, STAD, PRAD, and LGG, but negatively correlated with READ. To figure out the gene microenvironment, we found CENPK was also related to TMB in ACC, UCEC, THCA, STAD, SARC, READ, MESO, COAD, and BRAC. Even closer and wider correlation with MSI in different cancers. MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 were positively related to CENPK expression. All these outcomes show that CENPK may increase MSI and TMB by regulating mismatch repair genes, thereby promoting tumor progression. Studies in recent years have discovered diverse pathways in cancer that are affected by methyltransferases, mostly focused on cell proliferation, cell death resistance, invasion, and metastasis [30]. Furthermore, we also found a strong relationship between CENPK and methyltransferases, suggesting a genetic microscopic mechanism focused on cell proliferation, cell death resistance, invasion, and metastasis [30]. Nonetheless, further studies are warranted to fully uncover the roles and mechanisms of the CENPK gene.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we deliver a comprehensive genomic architecture for the effect of the CENPK gene on the immune microenvironment across about 30 solid tumors using data from TCGA and CCLE. Our outcomes showed that the expression level and mutation of the CENPK gene could regulate the immune microenvironment and long-term clinical outcome across different malignances. Commonly, our thorough pan-cancer investigation has illustrated the potential of CENPK to foresee the survival status for some kinds of cancer. From an immunology and genetics perspective, it correlated with tumor immunogenic features (mutational burden and neoantigen abundance). CENPK is expected to be a guiding marker gene for clinical prognosis and tumor immunotherapy. This lays the groundwork for the design of future experimental and clinical studies. Nevertheless, the CENPK gene still promotes a wide-ranging and in-depth knowledge of the molecular mechanisms in cancer.

Acknowledgements

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Ma X, Liu Y, Liu Y, Alexandrov LB, Edmonson MN, Gawad C, Zhou X, Li Y, Rusch MC, Easton J, Huether R, Gonzalez-Pena V, Wilkinson MR, Hermida LC, Davis S, Sioson E, Pounds S, Cao X, Ries RE, Wang Z, Chen X, Dong L, Diskin SJ, Smith MA, Guidry Auvil JM, Meltzer PS, Lau CC, Perlman EJ, Maris JM, Meshinchi S, Hunger SP, Gerhard DS, Zhang J. Pan-cancer genome and transcriptome analyses of 1,699 paediatric leukaemias and solid tumours. Nature. 2018;555:371–376. doi: 10.1038/nature25795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Priestley P, Baber J, Lolkema MP, Steeghs N, de Bruijn E, Shale C, Duyvesteyn K, Haidari S, van Hoeck A, Onstenk W, Roepman P, Voda M, Bloemendal HJ, Tjan-Heijnen VCG, van Herpen CML, Labots M, Witteveen PO, Smit EF, Sleijfer S, Voest EE, Cuppen E. Pan-cancer whole-genome analyses of metastatic solid tumours. Nature. 2019;575:210–216. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1689-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleppe A, Albregtsen F, Vlatkovic L, Pradhan M, Nielsen B, Hveem TS, Askautrud HA, Kristensen GB, Nesbakken A, Trovik J, Wæhre H, Tomlinson I, Shepherd NA, Novelli M, Kerr DJ, Danielsen HE. Chromatin organisation and cancer prognosis: a pan-cancer study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:356–369. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30899-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das S, Camphausen K, Shankavaram U. Cancer-specific immune prognostic signature in solid tumors and its relation to immune checkpoint therapies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:2476. doi: 10.3390/cancers12092476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger AC, Korkut A, Kanchi RS, Hegde AM, Lenoir W, Liu W, Liu Y, Fan H, Shen H, Ravikumar V, Rao A, Schultz A, Li X, Sumazin P, Williams C, Mestdagh P, Gunaratne PH, Yau C, Bowlby R, Robertson AG, Tiezzi DG, Wang C, Cherniack AD, Godwin AK, Kuderer NM, Rader JS, Zuna RE, Sood AK, Lazar AJ, Ojesina AI, Adebamowo C, Adebamowo SN, Baggerly KA, Chen TW, Chiu HS, Lefever S, Liu L, MacKenzie K, Orsulic S, Roszik J, Shelley CS, Song Q, Vellano CP, Wentzensen N Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Weinstein JN, Mills GB, Levine DA, Akbani R. A comprehensive pan-cancer molecular study of gynecologic and breast cancers. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:690–705. e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gentles AJ, Newman AM, Liu CL, Bratman SV, Feng W, Kim D, Nair VS, Xu Y, Khuong A, Hoang CD, Diehn M, West RB, Plevritis SK, Alizadeh AA. The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat Med. 2015;21:938–945. doi: 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali MM, Akhade VS, Kosalai ST, Subhash S, Statello L, Meryet-Figuiere M, Abrahamsson J, Mondal T, Kanduri C. PAN-cancer analysis of S-phase enriched lncRNAs identifies oncogenic drivers and biomarkers. Nat Commun. 2018;9:883. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03265-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen S, Zhang R, Jiang Y, Li Y, Lin L, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Shen H, Hu Z, Wei Y, Chen F. Comprehensive analyses of m6A regulators and interactive coding and non-coding RNAs across 32 cancer types. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:67. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang WH, Forde D, Lai AG. Dual prognostic role of 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases in ten cancer types: implications for cell cycle regulation and cell adhesion maintenance. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2019;39:23. doi: 10.1186/s40880-019-0369-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scully R. The spindle-assembly checkpoint, aneuploidy, and gastrointestinal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2665–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1008017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleveland DW, Mao Y, Sullivan KF. Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell. 2003;112:407–421. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee YC, Huang CC, Lin DY, Chang WC, Lee KH. Overexpression of centromere protein K (CENPK) in ovarian cancer is correlated with poor patient survival and associated with predictive and prognostic relevance. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1386. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komatsu M, Yoshimaru T, Matsuo T, Kiyotani K, Miyoshi Y, Tanahashi T, Rokutan K, Yamaguchi R, Saito A, Imoto S, Miyano S, Nakamura Y, Sasa M, Shimada M, Katagiri T. Molecular features of triple negative breast cancer cells by genome-wide gene expression profiling analysis. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:478–506. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Li H, Xia C, Yang X, Dai B, Tao K, Dou K. Downregulation of CENPK suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma malignant progression through regulating YAP1. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:869–882. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S190061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma J, Chen X, Lin M, Wang Z, Wu Y, Li J. Bioinformatics analysis combined with experiments predicts CENPK as a potential prognostic factor for lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:65. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01760-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Q, Liang J, Zhang S, An N, Xu L, Ye C. Overexpression of centromere protein K (CENPK) gene in differentiated thyroid carcinoma promote cell proliferation and migration. Bioengineered. 2021;12:1299–1310. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1911533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia B, Dao J, Han J, Huang Z, Sun X, Zheng X, Xiang S, Zhou H, Liu S. LINC00958 promotes the proliferation of TSCC via miR-211-5p/CENPK axis and activating the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:147. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01808-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, Traugh N, Chen Q, Liu JS, Li B, Liu XS. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li B, Severson E, Pignon JC, Zhao H, Li T, Novak J, Jiang P, Shen H, Aster JC, Rodig S, Signoretti S, Liu JS, Liu XS. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016;17:174. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Li H, Xia C, Yang X, Dai B, Tao K, Dou K. Downregulation of CENPK suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma malignant progression through regulating YAP1. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:869–882. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S190061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan C, Liu H, Robins E, Song W, Liu D, Li Z, Zheng L. Next-generation immuno-oncology agents: current momentum shifts in cancer immunotherapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:29. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00862-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotsiou E, Okosun J, Besley C, Iqbal S, Matthews J, Fitzgibbon J, Gribben JG, Davies JK. TNFRSF14 aberrations in follicular lymphoma increase clinically significant allogeneic T-cell responses. Blood. 2016;128:72–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-10-679191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hmeljak J, Sanchez-Vega F, Hoadley KA, Shih J, Stewart C, Heiman D, Tarpey P, Danilova L, Drill E, Gibb EA, Bowlby R, Kanchi R, Osmanbeyoglu HU, Sekido Y, Takeshita J, Newton Y, Graim K, Gupta M, Gay CM, Diao L, Gibbs DL, Thorsson V, Iype L, Kantheti H, Severson DT, Ravegnini G, Desmeules P, Jungbluth AA, Travis WD, Dacic S, Chirieac LR, Galateau-Sallé F, Fujimoto J, Husain AN, Silveira HC, Rusch VW, Rintoul RC, Pass H, Kindler H, Zauderer MG, Kwiatkowski DJ, Bueno R, Tsao AS, Creaney J, Lichtenberg T, Leraas K, Bowen J TCGA Research Network. Felau I, Zenklusen JC, Akbani R, Cherniack AD, Byers LA, Noble MS, Fletcher JA, Robertson AG, Shen R, Aburatani H, Robinson BW, Campbell P, Ladanyi M. Integrative molecular characterization of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1548–1565. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung YS, Kim M, Cha YJ, Kim KA, Shim HS. Expression of V-set immunoregulatory receptor in malignant mesothelioma. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:263–270. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu YC, Robbins PF. Cancer immunotherapy targeting neoantigens. Semin Immunol. 2016;28:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, Barron DA, Zehir A, Jordan EJ, Omuro A, Kaley TJ, Kendall SM, Motzer RJ, Hakimi AA, Voss MH, Russo P, Rosenberg J, Iyer G, Bochner BH, Bajorin DF, Al-Ahmadie HA, Chaft JE, Rudin CM, Riely GJ, Baxi S, Ho AL, Wong RJ, Pfister DG, Wolchok JD, Barker CA, Gutin PH, Brennan CW, Tabar V, Mellinghoff IK, DeAngelis LM, Ariyan CE, Lee N, Tap WD, Gounder MM, D’Angelo SP, Saltz L, Stadler ZK, Scher HI, Baselga J, Razavi P, Klebanoff CA, Yaeger R, Segal NH, Ku GY, DeMatteo RP, Ladanyi M, Rizvi NA, Berger MF, Riaz N, Solit DB, Chan TA, Morris LGT. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51:202–206. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Velzen MJM, Derks S, van Grieken NCT, Haj Mohammad N, van Laarhoven HWM. MSI as a predictive factor for treatment outcome of gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2020;86:102024. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hause RJ, Pritchard CC, Shendure J, Salipante SJ. Classification and characterization of microsatellite instability across 18 cancer types. Nat Med. 2016;22:1342–1350. doi: 10.1038/nm.4191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cao D, Xu H, Xu X, Guo T, Ge W. High tumor mutation burden predicts better efficacy of immunotherapy: a pooled analysis of 103078 cancer patients. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1629258. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1629258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeng C, Huang W, Li Y, Weng H. Roles of METTL3 in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic targeting. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:117. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00951-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]