Abstract

The Flipped Classroom (FC) approach is an important model for individualizing teaching, improving motivation, interaction, and increasing academic performance in a student-centered learning environment. However, at FC, not all students benefit equally from teaching opportunities. There may be important individual differences that affect their academic performance. The relationship between personality traits and academic performance in the FC model in which collaborative group studies are carried out is important for the design of individualized learning environments. In this context, the aim of this study is to research the relationship between academic success and personality traits within a collaborative flipped classroom model. Additionally, in this study, the differentiation of the relationship between academic success and personality traits according to gender, motivation, engagement, and interaction variables were examined. In this research, relational screening model was utilized. The application was achieved through the participation of 167 students for a 14-week period in Turkey. In the research, self-description form and data collection instruments were utilized. At the end of this research, Extraversion from personality traits is the strongest predictor of academic performance in FC. According to descriptive statistics, it was found that female students scored higher in FC settings for extraversion, and male students had higher scores for openness than other structures. In addition, it was found that the motivation scores of women and engagement scores of men were prominent. It was observed that the openness personality of the students with low motivation and the agreeableness of the students with high motivation is more dominant than the other personality structures. Students with the low level of engagement had the highest openness, and those with high agreeableness scores were the highest. The students with the low level of interaction had the highest openness scores, while those with high levels of interaction had the highest conscientiousness. While personality traits and academic achievements of students differed significantly according to gender, motivation and interaction levels, no significant difference was found according to engagement levels. The results reached in this study will guide the applicators about how the students become more ready to learn based on the personality traits of the classroom in which the FC model was utilized.

Keywords: Flipped classroom, Higher education, Academic success, Big five personality traits, Gender, Motivation, Interaction, Engagement

Introduction

Flipped Classroom (FC) is a model which is regarded as important in terms of individualizing the education in a student-centered learning environment, achieving active learning, developing interaction and the class-time to be utilized efficiently (Awidi & Paynter, 2019; Bergmann & Sams, 2009; Davies et al., 2013; Francl, 2014; Freeman et al., 2014; O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015). As a type of blended learning, FC (Durak, 2017), aims to achieve participation of the students in educational process and educational activities based on their skills and interests (Kim et al., 2014; Van Alten et al., 2019). Accordingly, the aim of this model is to construct a student profile, which is concentrated on the educational activity engagement, self-confident, enthusiastic, self-willedand motivated, and to individualize the education (Vasileva-Stojanovska et al., 2015). Individualizing the education at FC enables many positive results which are related to academic performance to be reached (Jovanovic et al., 2019; Lai & Hwang, 2016; Munir et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2018; Wilson, 2014). In the literature, it was mentioned that FC has academic outputs like collaborative work of students on particular subjects (Foldnes, 2016; Fox & Docherty, 2019), participation in evaluation process and independent learning skills (Shi et al., 2018; Wilson, 2014), self-directed learning skills (Lai & Hwang, 2016), development of learning responsibility (Chang & Lin, 2019; Huang & Hong, 2016; Moffett, 2015), improvement of academic performance (Lai & Hwang, 2016; Munir et al., 2018), motivation (Bhagat et al., 2016), satisfaction (Bösner et al., 2015; Forsey et al., 2013; O’Flaherty & Phillips, 2015), development of attitude towards learning in a positive direction (Chao et al., 2015) and enabling adoption of high-level thinking skills (Alsowat, 2016; Giannakos et al., 2014; Yildiz-Durak, 2018). However, in the study conducted by Vasileva-Stojanovska et al. (2015), it was indicated that the basic provision of achieving the best learning performance in blended learning environments is to provide a learning environment that is adapted in accordance with the personality traits of the students, and at the end of the related research it was found that personality traits are one of the important predictors of academic success at FC.

Personality traits are one of the main factors affecting the academic performance of the students (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2008; Furnham et al., 2009; Poropat, 2009; Vasileva-Stojanovska et al., 2015). In the previous studies, it was indicated that in teaching environments personality traits will affect many factors like student perceptions and their mood states (Calvo, 2009; Keller & Karau, 2013; Reis et al., 2018; Stewart et al., 2004), interaction level (Sun & Hsu, 2013) and academic success (Chamorro-Premuzic et al., 2006; Marks et al., 2005; Thompson & Zamboanga, 2004). When the literature was examined, even there are studies on the relation of students’ academic performance with personality traits, it was observed that the number of the studies (Lyons et al., 2017; Vasileva-Stojanovska et al., 2015) in which personality traits at FC were examined needs to be increased, and the nomological network on this subject needs to be expanded. As a matter of fact, although there are many findings in the literature regarding the relationships between personality traits and academic performance, current studies are needed for the consistency and generalizability of this relationship. According to Brandt et al. (2020), academic performance is the result of learning processes that are interactive in nature and reflects the interaction between the characteristics of the individual and the characteristics of the contexts in which learning takes place. Thus, time-varying educational opportunities and characteristics of flipped learning settings may affect the aspects of the relationship between personality traits and academic performance. For example, according to Fuster (2017), introverted individuals tend to be more reflective and therefore may benefit more from online learning environments that are asynchronous, progress at an individual pace, and do not involve group work. Extroverted individuals, on the other hand, will experience social loneliness in online environments. Learning experiences, interactions, and preferences of introverted and extroverted individuals will differ in learning environments consisting of face-to-face and online dimensions at FC. It is expected that this will have different reflections on academic performance.

In this study, collaborative learning and learning settings that provide face-to-face and online learning opportunities were created at FC. This learning environment is thought to represent a new learning context for personality traits and performance. It was hypothesized that this would lead to different associations between personality traits and academic performance. On the other hand, the Covid-19 pandemic has been the main driver of rapid growth in online education. It can be foreseen that the current trend will continue in the future. For this reason, the relationship between different individualized teaching styles and students’ academic performance should be examined in order to increase the accessibility and sustainability of higher education for many students (Abe, 2020). Moreover, in the study conducted by Lyons et al. (2017), the result was reached that all students cannot equally benefit from the learning means provided at FC, and among the factors affecting students’ benefiting statuses from FC and their learning preferences, personality traits come first.

However, according to Munir et al., (2018), the approaches having the highest potential are collaborative learning approaches to make learning at FC be more individualized and dynamic and to handle pedagogical problems about individualization. Thus, collaborative learning is a tutorial approach in which students interact and share their knowledge and skills to reach a particular learning objective (Bernard et al., 2000). On the other hand, according to some studies in the literature, FC, by nature, is an approach necessitating collaborative learning (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018; Betihavas et al., 2016; Foldnes, 2016; Fox & Docherty, 2019; Lai & Hwang, 2016; Sohrabi & Iraj, 2016).

This study aims to shed more light on student characteristics associated with successful FC learning, focusing specifically on the relationships between the big five personality traits and academic performance. Studies examining the relationships between personality traits and academic performance have not dealt with variables such as motivation, engagement, and interaction, which are important determinants of academic performance, in a holistic way. Therefore, it is unclear how personality and academic achievement are related to each other and whether the levels of motivation, engagement, and interaction provide differentiation. Therefore, a secondary aim of this study is to evaluate the relationship between academic achievement and personality traits in FC with motivation, engagement, and interaction levels. For these purposes, the research questions of the study are as follows:

Research Question 1: How are students’ levels of academic success in computing, personal traits, motivation, engagement, and interaction levels at FC?

Research Question 2: How are the relations between academic success in computing and personal characteristics at FC?

Research Question 3: Does the relationship between academic success and personality traits differ according to gender, motivation, engagement, and interaction variables?

Significance of the Research

There are concerns about students’ learning and developing professional skills during the instructions conducted at higher education. FC contributes students spending most of their in-class-times on the applications to improve their learning performances and gives chance to their application skills to develop (Strayer, 2012). Additionally, utilization of FC for contribution and development of various skills in educational environments increases day by day (Murillo-Zamorano et al., 2019). When the literature on FC was reviewed, it was observed that personality traits, academic success, interaction, engagement, and motivation are significant variables. On the other hand, the related literature focused too much on the collaborative learning experiences at FC and the effect of personality traits on academic success. Accordingly, the necessity of investigating the relationship between the collaborative applications in FK and personality traits came to the fore. The results of this study are expected to provide guidance to the instructors and to the future research on individualization of FC. This study sheds light on the understanding that student will demonstrate higher academic success, higher motivation, engagement, and interaction in FC environment, and sheds light on the effect of learner’s personality to the learning process. The results of this study may provide important clues about course developing and designing at FC and contribute instructors to develop different opinions on design. Additionally, the results of this study may be guiding not only for the blended courses with academic purpose but also for the other education institutions providing blended education and for the instructors.

In the following sections of this study, there are conceptual and theoretical foundations, literature review, method, results, discussion, and conclusion sections, respectively.

Conceptual Background and Literature Review

Theoretical Basis

In the literature, it is seen that various theoretical frameworks are used in FC studies. Li et al. (2021) emphasize that many theoretical foundations such as personalization, higher-order thinking, self-direction, collaborative, problem-based learning, peer-assisted learning, and self-determination are used in FC studies.

Bredow et al. (2021), in their meta-analysis study, indicate that one of the most prominent theories in the effective design of FC is constructivist learning theory. Therefore, in this study, the design and implementation of FC were carried out within the framework of constructivism theory. Emphasizing the important role of the collaborative in learning, constructivism theory provides a theoretical basis for the development of flipped classes in this study. The basic principle of constructivism theory is that learning occurs when a person constructs his own knowledge actively, not passively (Tobin & Tippins, 1993). Interaction and collaborative activities in FC provide the context that allows the student to socially construct knowledge individually or with peers. According to Li et al. (2021), in the learning process, students should take initiative to discover new knowledge and connections, solve problems, and complete tasks in real situations in collaboration with others. In this study, in the collaborative FC environment, students’ personal characteristics were evaluated as a related construct in providing knowledge construction.

Flipped Classroom

FC is a model in which direct teaching is provided out-of-class and mostly via videos. And in-class, FC is a model aiming to spare more time for in-depth discussions about the subject, problem-solving activities, peer collaboration and activities of individualized instructor guidance (Francl, 2014). Bergmann and Sams (2012) indicated that this method means not only video courses, and the significant point is the meaningful and interactive activities that are performed in-class. Moreover, one of the most striking features of FC is that it increases the individual responsibility on student’s learning (Fautch, 2015; O’Flaherty & Philips, 2015; Staker & Horn, 2012). In such an active learning environment, students out-of-class learn the information they need to learn about the course during the time which is suitable for them and in-class-time is further spared to collaborative and student-active works. Additionally, it was indicated that FC increases the interaction between the students and the teacher (Strayer, 2012; Touchton, 2015). FC supports student-student, student-content and student-teacher interaction chances via online collaboration instruments (e-library, discussion environments, messenger, shares, etc.), and enables students to spend more time in-class (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018). An increase in student-teacher interaction enabled the role of the instructor in this model to shift from content presenter to the learning coach (Bergmann & Sams, 2012).

The related literature demonstrates that FC has various benefits to educational and learning processes (Chao et al., 2015; Missildine et al., 2013; Pierce & Fox, 2012). According to Yildiz-Durak (2018), while new content is presented once or only the unclear parts are re-explained in the traditional classroom, in FC model it is possible that students review the written learning materials at a speed they want and as much as they need or skip the content, they already have information about. This status enables the student to proceed based on his/her speed. On the other hand, according to Moffett (2015), since students can access learning content independent from the notion of time-space, out-of-class learning is flexible. According to Lai and Hwang (2016), FC model encourages development of self-regulation strategies, which are related to out-of-class learning processes. Because, FC has a structure that will support the student to develop learning responsibility (Kim et al., 2014; Mok, 2014; Van Alten et al., 2019). At FC during in-class and out-of-class learning, students participate in questioning and problem-solving activities, construct their knowledge, conducts collaborative works with their peers and utilize fast and various feedback receiving means. Since they enable chances of abundant learning choices, collaborative learning, and interaction, all these statuses develop the learning performance (Yildiz-Durak, 2018).

Collaborative learning contributes to deeper, meaningful learning and development of social skills (Johnson & Johnson, 1999). Since it is an environment in which the students are responsible for their self-learning, they actively learn; meta-cognitive learning takes place, and because it utilizes small-group activities to develop teacher-student-content interaction, FC includes collaborative learning (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018).

In an environment in which teachers take less part in information transfer and students are responsible for their self-learning, mechanisms of FC approach require high motivation, satisfaction and active participation (Freeman et al., 2014). However, within FC approach, the question of how personality traits may affect students’ interaction with a learning environment, their preferences, willing to collaborative work and learning experiences is examined. Lyons, Limniou, Schermbrucker, Hands, and Downes (2017) researched how personality affects students’ preferences, decision-making processes, intention to learn and readiness to education at FC compared to traditional courses. The related study identified the Big Five Personality Traits (in word Openness, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, Extraversion and Neuroticism) as individual differences affecting the preference of different learning and teaching approaches. Lyons et al. (2017) emphasized that interaction preference at FC has a relation with high Agreeableness and low Neuroticism, and meaningful learning will be achieved as these personality traits encourage participation in collaborative works. Furthermore, the reflective learning stills which include transfer of learned information to problem statuses are in relation to Conscientiousness and Openness to experience (Komarraju et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2019). Therefore, it was emphasized that high Openness, Conscientiousness, and low Agreeableness and low Neuroticism affect performance expectation, intention to learn, learning preferences and decision-making processes at FC. Learning performance’s potential to be affected by personality traits at FC is high because learning responsibility is given to the student, achievement of self-learning is attained and the learning approach is flexibility (Hao, 2016).

Collaborative Learning at FC

Collaborative learning is an approach in which students work in small groups for a common objective, interact mutually and share their knowledge and skills to reach to a particular learning objective (Prince, 2004). Collaborative learning is a type of learner-learner interaction (Bernard et al., 2000) and it depends on social constructivist learning theory emphasizing that learning and knowledge are affected from interaction and collaboration (Krange & Ludvigsen, 2008). According to this constructivist learning opinion, development of learning can be understood not only by individual studies but also it is necessary to examine the outer social environment. Individual’s learning requires a particular social environment and a social process including child’s growing up in this environment and peer supported applications (Vygotsky, 1978). According to Slavin (1990), collaborative learning is more than working as a group and it is the construction of mutual attachment in a positive way in order that a particular objective or output is achieved.

Collaborative learning increases active learning by pushing students to manage their groups and the content developed in the groups, and to take responsibility for developing the communication (Keyser, 2000). through collaborative group works, and accordingly students may gain cognitive, social and communication skills like achieving self-learning and sustaining it, taking responsibility, expressing themselves, receiving peer support, benefiting from ideas of each other, solidarity, finding solution to the problems rooting from conflicts and respecting to different features (Johnson & Johnson, 1986). According to So and Brush (2008) and Elia et al. (2019), there are computer-mediated communication instruments at the technical base of collaborative learning. These instruments are important to ease group learning processes between group members having different learning styles in different time and spaces or in face-to-face environments, to study on group project, for active participation, to exchange knowledge and skills, and to develop interpersonal communication skills. Accordingly, FC comprises collaborative learning (Munir et al., 2018). Tucker (2012) indicated that students at FC can utilize their class-times in order to work together and participate in collaborative learning. Within collaborative FC environments, students can notice their self-learning levels; since they need to find solutions together with their peers, they can develop skills of deep learning and critical thinking, and to reflect their learning, they can utilize class-time at FC. On the other hand, there are findings in the literature that collaborative learning increases student’s participation and motivation (Herrmann, 2013), and develops learning performance (Johnson & Johnson, 2008). Since it was thought that collaborative works would be effective on students’ academic performance also at FC, a collaborative FC model was constructed in the current study.

Munir et al. (2018) indicate that collaborative learning can be beneficial only when it is managed carefully, otherwise, it may have difficulties. For example, in-group or inter-groups rivalry may emerge or if the basic processes of collaborative learning cannot be understood by the students sufficiently, classroom management problems may emerge. On the other hand, creating collaborative groups is a demanding work and achieving group cohesion may become a problem. Perceptions of collaborative learning may differentiate based on cultural background or disciplines (Gillies, 2016). Within this context, developing in-class time creativeness for the solution of the prospect problems, which may emerge in FC environments, may be utilized for contributing to new ways of critical thinking and problem solving, and for student-teacher interaction (Roehl et al., 2013). Additionally, teacher coaching on how students can collaborate to solve their problems in collaborative learning groups may be important for the solution of prospect problems.

Kim et al. (2014), in their study, presented the principles of FC model design within revised community of inquiry (CoI) framework (cognitive presence, social presence, teaching presence, and learner presence). This framework demonstrates that creating information, particularly in online/blended learning environments, roots from active students and the interaction based on the collaboration between the content and teachers (Shea & Bidjerano, 2010, Shea et al., 2012). When these interactions are taken into consideration, it is thought that FC environment interactions will improve CoI and enhance efficiency of collaborative FC environment.

Personality Traits

Five Traits of Individual Personality

Agreeableness can be expressed as individual’s level of collaboration, well temper, trustworthiness and flexibility (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Sulea et al., 2015). Individuals having a higher Agreeableness trait give priority to success at work/school environment and to social activity (Judge et al., 1999). For this reason, such individuals tend to try to solve the problems they come across (Zimmerman, 2008). Furthermore, individuals having high agreeableness trait are expected to comply with the necessities of the tasks assigned to them (Salgado, 2002). Since individuals having Agreeableness trait tend to social interaction, they are expected to be more active at FC. Because individuals having lower Agreeableness trait have conflict and disagreements in their relations, they break rules at educational environment, or they tend to ignore the rules (Goldberg, 1999).

While individuals having higher Conscientiousness trait are identified as success oriented, planned, organized, trustworthy and responsible, individuals having lower conscientiousness trait can be expressed as careless, unreliable, and irresponsible (Saleem et al., 2011). Extraversion as the personality trait expresses enthusiasm, ambitiousness, activeness, sociability, and optimism levels of the individual (Clark & Watson, 1999).

Neuroticism is a personality trait, which is in relation with the emotional balance levels of the individual (Swider & Zimmerman, 2010). Individuals who can be identified as neurotic have difficulty in adapting to any kind changes in their work or living environments and they tend to focus on negative aspects of the environment.

Openness is a personality trait, which is in relation with levels of creativeness, intellectual curiosity, and open mindedness of the individual. Individuals having high level of openness trait are creative, flexible, and curious, open to changes and they tend to regard the disappointments, which are related to the difficulties they encounter or the negative emotions/difficulties like anxiety as important chances for their personal developments (Zimmerman, 2008).

Extraversion is the personality trait, which is in relation with individual’s states of being enthusiastic, cheerful, assertive, energetic, enterprising, and excited about the prospect chances (Costa & McCrae, 1992). On the contrary, the ones having introversion trait prefer to be alone in their academic and social lives. At FC in which collaborative works are, done students are expected to efficiently interact with lesson sources and group friends. As it is expressed by Zhao and Seibert (2006), individuals having extraversion trait tend to efficiently develop social interactions and this status seems to be beneficial for improving motivation and commitment of their other co-workers.

Overview of the Research on Personality Traits and FC

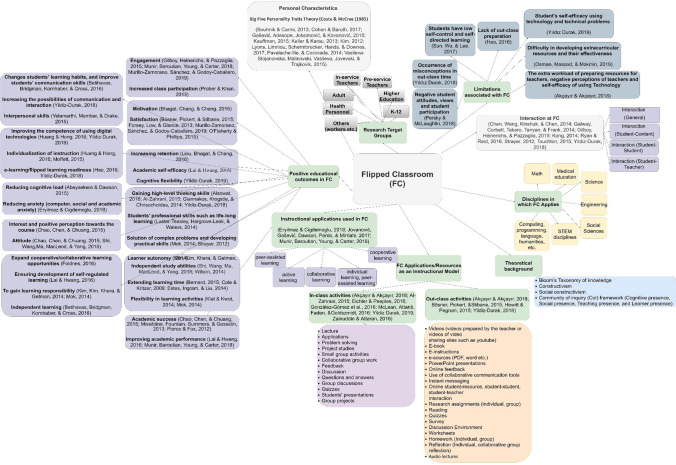

FC is a concept attracting attention of the researchers particularly for the last 20 years (Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018). A nomological network was created within context of this study in order to have a better understanding of FC related results, fields utilized and the activities done at FC (See: Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Nomological Network Based on the Studies related to Flipped Classroom

In studies dealing with the FC model and personality traits, it was seen that FC practices basically consist of in-class and out-of-class activities. It was observed that elements of lecture applications, problem solving-project studies, small group activities, collaborative group work, feedback, group discussion, questions and answers, quizzes, students’ presentations were used in in-class activities. In out-of-class activities; videos, e-book, e-instructions, e-sources, online feedback, use of collaborative communication tools, instant messaging, online student-resource, student-student, student-teacher interaction, research assignments (individual, group), reading, quizzes, survey, discussion environment, worksheets, homework (individual, group), reflection (individual, collaborative group reflection) and audio lectures were prominent. It was seen that the FC model is used in different disciplines in education (e.g. math, Medical education, Science, Engineering, Social Sciences, STEM disciplines, computing, programming, language, humanities). Looking at the positive educational outcomes of the FC model, it was seen that the improvement of academic success and academic performance comes to the fore. However, it was seen that the FC model is effective in developing engagement, motivation, interaction, satisfaction, attitude, responsibility, and various high-level thinking skills. It was seen that studies have been carried out with different research groups and some limitations have emerged in these groups. Among these limitations, the inadequacy of out-class preparation, negative attitudes, inadequacies in using technology, formation of misconceptions, the inadequacy of interpersonal extracurricular interaction can be counted. Overall, these reviews tend to conclude that the FC model is associated with increased student achievement, motivation, interaction, and engagement. However, it can be said that there are limitations in FC and individualized designs will be a solution considering personal characteristics.

Academic Success and Personality Traits at FC

Studies demonstrate that Big Five traits are in relation with academic performance (eg., Laidra et al., 2007; Poropat, 2009; Sorić et al., 2017). In the study conducted by Lyons, Limniou, Schermbrucker, Hands, and Downes (2017), it was emphasized that personality traits at FC affected the statuses which will affect academic success like intention to learn and learning preferences. The relation of academic success with Big Five traits at FC was explained within context of Conscientiousness, Openness, Agreeableness, Extraversion and Neuroticism scopes.

Conscientiousness, in other words self-discipline, eases concentrating on academic studies by taking the responsibility of learning (Steel et al., 2001). Development of learning responsibility through the individual, independent studying and the flexibility provided, and increase of academic performance were aimed at FC learning (Shi et al., 2018; Wilson, 2014). Within this context, it is expected that individuals having high Conscientiousness trait will be more successful since they will be able to maintain sustainability of the learning without leaving the learning environments and by taking the responsibility of learning at FC. Openness, in other words imagination, contributes to new working patterns and idea generation (Rimfeld et al., 2016, s. 718; Zeidner & Matthews, 2000). Al-Zahrani (2015) emphasized that FC may encourage students’ creativity particularly on fluency, flexibility, and innovation issues in collaborative environments. Additionally, FC is perceived as a concept which may make their creativity be considerably easier according to the opinions of the students. For this reason, it is expected that the students whose Openness trait comes to the forefront are more ready to utilize FC and to generate ideas more actively in collaborative learning environments (e.g. group discussions). Agreeableness, in other words consistency, supports attendance to class, social communication and collaborative group works (Lounsbury et al., 2003). Extraversion, in other words extroversion, supports socializing but, on the other hand prevents students from concentrating on their learning duties (Bidjerano & Dai, 2007). Because the collaborative FC studies are discussed in this study, it is thought that it will positively contribute to academic success. Neuroticism, on the other hand, is indicated to include neuroticism and anxieties which prevent performance (Poropat, 2009). It is thought that Neuroticism trait may have a preventive effect on group cohesion of the students, their learning preferences and decision-making processes during collaborative learning activities at FC. According to Reis et al. (2018), at technology-supported collaborative environments, positive personality traits positively affect students’ sense of belonging, state of being enthusiastic about collaborative working, group cohesion, motivation, and creation of meaningful interactions with purpose of learning. Thus, collaborative learning activities at FC and academic success are expected to be affected from personality traits. From this context forth, following hypotheses were created in the current study:

H1a. At FC, there is a meaningful positive relation between agreeableness and academic success.

H1b. At FC, there is a meaningful positive relation between conscientiousness and academic success.

H1c.At FC, there is a meaningful positive relation between extraversion and academic success.

H1d. At FC, there is a meaningful negative relation between neuroticism and academic success.

H1e. At FC, there is a meaningful positive relation between openness and academic success.

Academic Success and Personality Traits in FC Model According to Gender

At an analysis study conducted by Allen and Walter (2018), entity of a relation between Big five and gender was emphasized. According to Muscanell and Guadagno (2012), gender differences are important in online environments, and they bring about differentiation in terms of the time period spent online engagement, interest and motivation. For example, it was emphasized that women have higher possibility to utilize online environments and collaborative instruments to socially interact, and have higher tendency to success (Guadagno et al., 2011). At this study role of the gender in the relation between personality traits and academic success at FC was examined. In fact, any kind of findings on this subject could not be reached in the related literature.

Academic Success and Personality Traits in FC Model According to Motivation

At various studies in the literature, there are results on the relationship between academic success and motivation. However, according to Komarraju et al. (2009), the relationship between personality and academic motivation is very important and limited number of studies handled this relationship. In the mentioned study, motivation is thought to have a role in the relationship between academic success and personal characteristics. Because individual differences are important for the success objectives of the students. Students may be very enthusiastic to achieve their success objectives based on their personal characteristics and may perceive difficulties they have in learning as a chance or they may give up by regarding difficulties as thread (Elliot & Thrash, 2010; Harackiewicz et al., 2002). Yet, adequate evidence of personality’s effects on academic motivation and success objectives is not available.

Academic Success and Personality Traits in FC Model According to Engagement

Academic attendance of the student is regarded as an important indicator of the fact that proceeding of the academic activities are achieved at an optimal level (Reeve & Tseng, 2011). Academic attendance expresses attendance levels of the students to various scientific activities in academic environments (Fredricks et al., 2004). Studies indicated that students having high academic engagement may achieve higher academic success (Dotterer & Lowe, 2012). Thus, academic engagement becomes more important if it requires out-of-school works and collaborative learning like in the FC (Yildiz Durak, 2022). As a result of these reasons, at FC academic interaction is thought to be effective in the relationship between personal characteristics and academic success.

Academic Success and Personality Traits in FC Model According to Interaction

Collaborative learning is based on constructivist interaction (Hernández-Sellés et al., 2019). Moore (1989) suggested an interaction framework, which includes learner-teacher interaction, learner-student interaction and source-learner interaction in on-line distance education. In order to secure quality of the learning processes interaction component should be taken into consideration. Interaction component is also quite important for the FC because interactions of source-student and teacher should take place during out-of-class times (Yildiz-Durak, 2018). On the other hand, personal characteristics are thought to be in relationship with interaction patterns of the students. Any kind of studies which handle this context were not reached.

Method

In the study relational screening model was applied. Relational screening model aims to determine the covariance status and/or the level between two or more variables (Karasar, 2013).

Study Group

This study is conducted through participation of 167 university students from a public university in Turkey to the application done in 2017 and 2018 academic year fall semester. Among the participants 63.5% is female and 36.5% is male. Students participating to the study are predominantly 18-24 age group bachelor students. Majority of the participants (83.20%) are observed to use information technologies more than 3 years. Another majority of the participants (80.80%) uses internet longer than 1 hour daily.

Data Collection Instruments

In the study Self-description Form and three separate data collection instruments have been utilized.

Self-description Form: Developed by the researcher, this data collection instrument consisted of two parts. During the development process of this form, opinions of two field experts were consulted. Survey items differ based on the questions and are in Likert pattern in general. With self-description form, which is the first part, data collection on personal information of study group was aimed. This part consisted of 3 items in total. ICT usage experience and its period, frequency of educational activities at FC and 22 questions on the period participants spent while utilizing components of the environment were presented at the other part. The data on educational activities at FC, weekly frequency of learning tasks and weekly spent hourly time were collected from statements of the participants under 44 items. 10 items were prepared regarding the interaction of the students with the environment. Student’s interaction frequency with educational partners and sources was determined by giving Likert pattern options in the questions on the interactions between student-student, student-teacher, and student-source. Since Edmodo media, which is utilized as the on-line learning environment does not allow instructors to access to user logos, student statements were based on. Activities determined in this form were created by listing the activities conducted within the content of the lesson.

Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire: Original version of this scale was developed by Pintrich, Smith, Garcia and McKeachie (1991) and scale’s adaptation to Turkish language was done by Büyüköztürk, Akgün, Özkahveci and Demirel (2004). This scale which was developed for university students is composed of 31 items and 6 sub-scopes (intrinsic goal orientation, extrinsic goal orientation, task value, control beliefs, self-efficacy for learning and performance, and test anxiety). This scale which is in 7-Likert type is graded in forms of “strongly disagree”(1) and “strongly agree”(7). According to the results of the exploratory factor analysis of the original scale, it was found that there were 6 factors with an eigenvalue bigger than 1. Factor loading values were found to be between 0.46-0.80. In the present study, factor loading values ranged from 0.628 to 0.918. The total variance explained by the structure collected in all factors was 56%. In the current study, the total variance explained by the structure was 72.86%. In the confirmatory factor analysis of the original scale, the c2/sd ratio was 4.47. Since this ratio was less than 5, the model is acceptable. The fit index values are RMSEA=0.06, GFI=0.88, AGFI=0.85, CFI=0.82, NNFI=0.80, RMR=0.18 and SRMR=0.06 and were at an acceptable level. In this study Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient is calculated as 0.977. Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients of the sub-scales are calculated as 0.881, 0.979, 0.901, 0.895, 0.886, 0.917 respectively. The values were found to be at an acceptable level (0.70) (Nunnally, 1978). On the other hand, the half-split method results of this scale were calculated as 0.967. These results show that the internal consistency of the measurement tool is high. It was seen that the item-total correlations for all items in the scale vary between 0.524-0.910. The t-test results between the upper 27% and lower 27% groups show a significant difference for all items and subscale total scores. These results were interpreted as the items in the scale had high validity and were items intended to measure the same behavior.

Big Five Personality Traits Scale: This scale was developed by Rammstedt and John (2007) and adapted to Turkish culture by Horzum, Ayas and Padır (2017). This scale is composed of 10 items and it is in 5-factor type. The scale aims to scale the Big Five personality traits. According to the results of the exploratory factor analysis of the original scale, it was found that it was gathered in 5 factors with an eigenvalue bigger than 1. Factor loading values were found to be between 0.706-0.946. The total variance explained by the structure gathered in 5 factors was 88.4%. In the confirmatory factor analysis of the original scale, fit index values were found as RMSEA=0.062, GFI=0.96, AGFI=0.91, CFI=0.98, NFI=0.97, and SRMR=0.035, and these indices were found to indicate perfect fit. Cronbach’s alpha reliability values were calculated as 0.88 for extraversion, 0.81 for agreeableness, 0.90 for self-control, 0.85 for neuroticism, and 0.84 for openness, respectively. In addition, the validity and reliability values obtained in the context of this study were presented in the findings section.

Academic success: Academic success score of the students is the average score calculated by University Information Management System through one midterm exam and one final exam. Midterm and final exams which were done to scale academic success levels of the participants in informatics lesson have a structure which comprises all titles of the content. Subject titles taking place in the content are as “basic concepts of information technologies, usage of office package programs, blog creation and sharing”.

Application Process

Application lasted 14 weeks in total. At the 8th week midterm and at the 15th week final exams were done. In Basic Information Technologies class, course materials were prepared within context of the course (video, sample works, etc.,) and e-sources were delivered during the same weeks to all groups via edmodo (edmodo.com) system. In the first week, information about both desktop and mobile versions of edmodo was given and all students were enabled to log on to the system. At the beginning of the semester, content of the lesson, teaching method and evaluation process were explained. In Basic Information Technologies class, a midterm and a final exam which cover all subjects of the lesson were done. Midterm exams make 40% and final exams make 60% of the scores of a student. Students were asked to compose small groups (4-5 persons) for collaborative learning. Their self preferences were based on in creation of these groups in accordance with the social communication of the students. For each group a sub-group was created at edmodo which they used during the whole semester. By this way, out-of-class learning activities of the students at FC were examined through collaborative groups. Accordingly, groups were asked to write reflection report for each week at their blogs. To this end, one person from each group created blog at the blogger and added other friends in the group to the blog as the writer/editor. At the end of each week, groups wrote a reflection blog about their weekly learning.

Videos, e-books and work sheets were shared through on-line environment for extracurricular studies. In order that students have discussions in a collaborative environment out-of-class, discussion questions were shared at edmodo by the lecturer. To direct the discussions between student groups, lecturer of the lesson supervised the on-line environment continuously.

While Edmodo media displays discussion questions and number of activities of the groups/individuals who like the shares and reply at any time, all activities done in the system were listed by the researcher because, edmodo does not provide the logs like students’ surfing in the system, time they spent in the system etc, and the frequency of these activities and the time spent on these activities were calculated based on self-reporting.

At the end of Basic Information Technologies class (week 14th), students were asked to fill in data collection instruments. On the other hand, because the efficiency of personality traits in improving the learning was examined; collaborative group works, interaction between group members and group consistency were particularly paid attention.

To make the teaching effective and to contribute to the learning at FC, responsible lecturer of the lesson aims to determine and compensate wrong or incomplete learning by asking questions during in-class times. In order to enable students to transfer their knowledge and personal experiences in educational applications during both in-class and out-of-class processes; blogs, micro-blogs and discussions were attached importance. Encouraging the reflective applications in collaborative groups contributes participants to developing emotional relations. We aimed to improve the reflective applications by utilizing on-line chat instruments, discussion environments, blogs and micro-blogs. Applications conducted within frame of FC model, screen shuts of the course content and the applications conducted in relationship with the application process are presented at Table A and Figure A in the Appendix.

Data Analysis

Before starting the analysis of the data, transformations were made between the Likert structures of the scales. Dawes (2008) proved in his study that data collected in 5 point Likert format can be easily transferred to 7 point Likert equivalence using a simple rescaling method. In this context, depending on the method used by Dawes (2002), the scales used in the research were converted to 7-point Likert scales. According to this method, a simple arithmetic procedure is followed in which the scale endpoints are fixed to the endpoints of the 7-point scale for the 5-point versions. Intervening scale values are added at equal numerical intervals. In this context, the following formula is used to convert a 5-point rating to a 7-point Likert structure:

x7 = (x5– 1)(6/4) + 1

Additionally, while the breakpoints were settled for scale scores, intervals suggested in the study where the scale was developed were primarily taken into consideration, and if there was a leveling in the original scale development study, that leveling was utilized. If there was not a leveling, while interpreting, values of mean/item number in 5-Likert scales were regarded as low level on condition that they were below two, and regarded as high level if they were above two. Moreover, for 7-Likert scales, values of mean/item number were regarded as low level if they were below 3 and regarded as high level if they were at and above 3.

In order to come up with a model which determines entity of the relationship between university students’ levels of academic success in computing and their personal characteristics, explains and predicts the relationship between these variables; Structural Equation Model (SEM) was utilized. Variance-based PLS-SEM using partial least square was used and analyzes were made with SmartPLS 3.0. Structural equation modeling was carried out in two stages, analyzing the measurement model to validate the indicators in the model and testing the structural model.

Personality traits and academic success of university students; One-way multivariate analysis of variance (one-way MANOVA) was used to examine the situation according to gender, motivation for learning, engagement, and interaction level for learning. Assumptions for this analysis are reported in the result section.

Results

Findings Related to Research Question 1

Descriptive Findings

After computing education, descriptive values on students’ levels of academic success, personality traits, motivation, engagement, and interaction are presented at Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

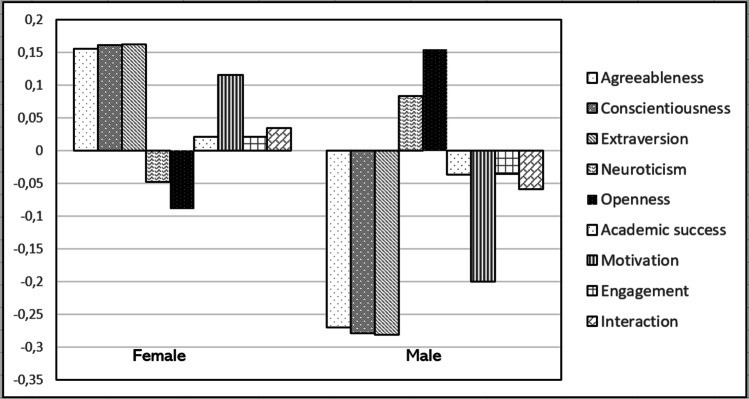

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the means of research variables according to Z scores by gender

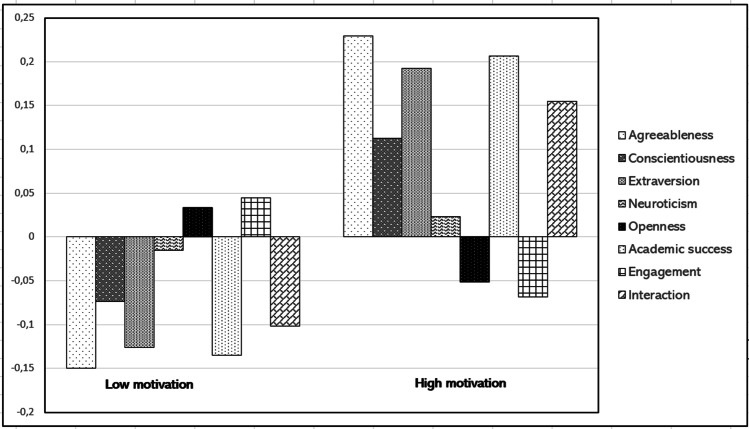

Fig. 3.

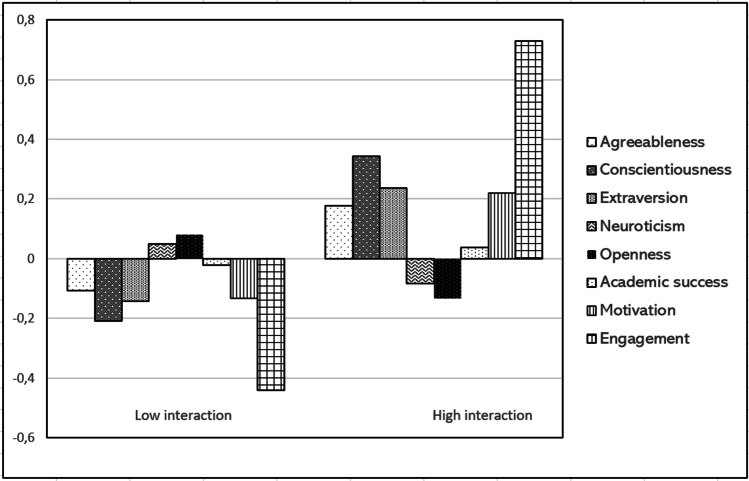

Comparison of the mean of the research variables according to the motivation levels according to the Z scores

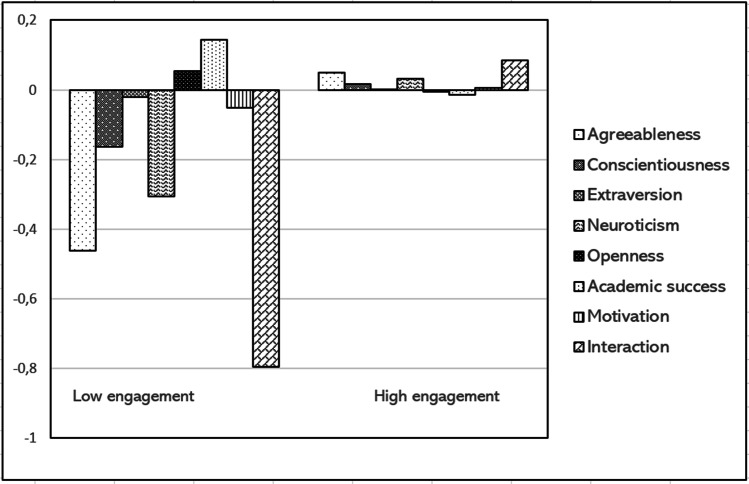

Fig. 4.

Comparison of means of research variables according to engagement levels according to Z-scores

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the means of research variables according to their Z scores according to their interaction levels

According to Figure 2, the extraversion scores of female students were the highest. It is followed by conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness, respectively. The students’ motivation scores are followed by their interaction, academic success, and engagement scores. From this point of view, it can be said that extraversion and motivation for learning come to the fore in FC settings among female students. In male students, on the other hand, it is seen that the openness comes to the fore. This is followed by neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion. Engagement scores of male students are followed by academic success, interaction, and motivation scores.

According to Figure 3, students with low motivation have the highest openness personality structure scores. It is followed by neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness, respectively. Engagement scores of students are followed by interaction and academic success scores. It was seen that the agreeableness comes to the fore in highly motivated students. It is followed by extraversion, conscientiousness neuroticism, and openness, respectively. The academic success scores of these students were followed by interaction and engagement scores.

According to Figure 4, students with low engagement have the highest openness scores. This is followed by extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and agreeableness. Academic success scores are followed by motivation and interaction scores. It was seen that the agreeableness comes to the fore in students with high engagement. This is followed by neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness. The interaction scores of these students are followed by their interaction and academic success scores.

According to Figure 5, students with low interaction have the highest openness scores. This is followed by neuroticism, agreeableness extraversion, and conscientiousness. Academic success scores are followed by motivation and engagement scores. It was seen that the conscientiousness comes to the fore in high-engagement students. This is followed by extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness, respectively. These students’ engagement scores were followed by their motivation and academic success scores.

Findings Related to Research Question 2

SEM

Measurement Model

Internal consistency reliability, convergent and discriminant validity were examined for the reflective measurement model. For the formative measurement model, variance inflation factor (VIF) values for indicator collinearity were examined.

The fact that all factor loads were bigger than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2017) and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) value is above 0.50 (Hair et al., 2018) shows that the convergent reality is good. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability value is expected to be above 0.70 (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015; Jöreskog, 1971). Items with factor loadings below 0.70 were excluded from the model.

According to Table 1, the factor load of all items in the measurement model was bigger than 0.70. AVE values above 0.50 in all structures. In the measurement tool used for the measurement of personality traits, each factor was represented by two items (one of which is reversed). On the other hand, the factor load of the items in the five structures related to personality traits ranged from 0.40 to 0.70. In order to move the model fit, validity, and reliability values from acceptable to perfect fit, reversed items were removed and these constructs were represented by one item. Diamantopoulos, Sarstedt, Fuchs, Wilczynski, & Kaiser (2012) and Rossiter (2002) stated that single-item structures can measure as valid as multi-item structures.

Table 1.

Factor loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha, rho_A, Composite Reliability and Average Variance Extracted (AVE)

| Structures | Factor Loading (between items) | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_A | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality traits | |||||

| Agreeableness | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Conscientiousness | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Extraversion | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Neuroticism | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Openness | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Academic success | 0.908-0.934 | 0.823 | 0.838 | 0.918 | 0.849 |

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) values for discriminant validity were examined. HTMT values were presented in Table 2 and these values were expected to be below 0.90 (Henseler et al., 2015; Ringle et al., 2015). HTMT values indicate that discriminant validity was achieved. As a result, it was seen that the measurement model meets the criteria set forth in the literature.

Table 2.

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic success | |||||

| Agreeableness | 0.085 | ||||

| Conscientiousness | 0.036 | 0.379 | |||

| Extraversion | 0.159 | 0.286 | 0.122 | ||

| Neuroticism | 0.055 | 0.108 | 0.232 | 0.054 | |

| Openness | 0.055 | 0.032 | 0.067 | 0.062 | 0.065 |

According to Table 3, between academic success and extraversion (r=0.135); There is a significant positive correlation between agreeableness and extraversion (r=0.286), conscientiousness (r=0.379), and neuroticism (r=0.108). Extraversion and conscientiousness are also significantly related (r=0.122). Conscientiousness and neuroticism are other related personality structures (r=0.232).

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [6] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1] Academic success | 1.000 | |||||

| [2] Agreeableness | 0.074 | 1.000 | ||||

| [3] Openness | 0.047 | -0.032 | 1.000 | |||

| [4] Extraversion | 0.135 | 0.286 | 0.062 | 1.000 | ||

| [5] Conscientiousness | 0.032 | 0.379 | 0.067 | 0.122 | 1.000 | |

| [6] Neuroticism | 0.030 | 0.108 | 0.065 | 0.054 | 0.232 | 1.000 |

Structural Model

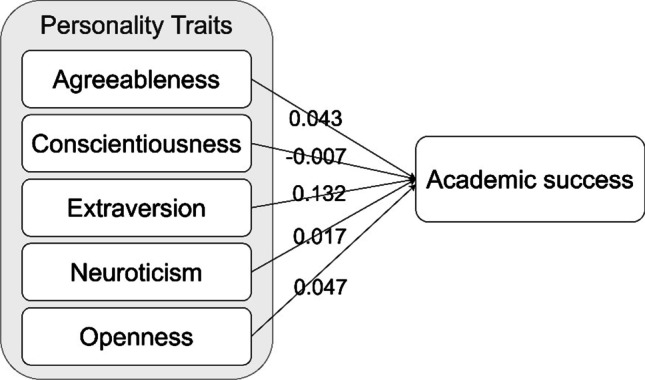

In this study, a total of five hypotheses were tested. The structure reached as a result of testing the research model was presented in Figure 6.

Fig. 6.

Structural model results-path coefficient

The findings regarding the evaluation of the hypotheses were presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hypothesis test

| Hypothesis | Path | B | t-value | p | Supported(Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | Agreeableness ➡ Academic success | 0.043 | 0.482 | 0.630 | No |

| H1b | Conscientiousness➡ Academic success | -0.007 | 0.055 | 0.956 | No |

| H1c | Extraversion➡ Academic success | 0.132 | 1.987 | 0.047 | Yes |

| H1d | Neuroticism➡ Academic success | 0.017 | 0.236 | 0.813 | No |

| H1e | Openness➡ Academic success | 0.047 | 0.549 | 0.583 | No |

As seen in Figure 6 and Table 4, the hypothesis that there is a significant relationship between agreeableness and academic success was rejected (β= 0.043; p>0.05; H1a supported/no). Conscientiousness personality has no direct effect on academic success (β= -0.007; p>0.05; H1b supported/no). It was found that there was a significant relationship between Extraversion and Academic success (β=0.132; p<0.05) and H1c was supported. It was concluded that neuroticism was not negatively and significantly associated with academic success (β = 0.017, p>0.05; H1d supported/no). Finally, it was found that there was no significant relationship between openness and academic success (β = 0.047, p>0.05) and H1e was not supported.

Findings Related to Research Question 3

MANOVA Analyses

One-way MANOVA results regarding the differences in students’ personality traits and academic achievement scores according to gender, motivation, engagement, and interaction variables were summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

One way MANOVA results

| Gender* | Motivation** | Engagement*** | Interaction**** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic success | F=0.131, p=0.717, η2=0.001 | F=4.763, p=0.03, η2= 0.028 | F=0.367, p=0.545, η2= 0.002 | F=0.136, p=0.713, η2= 0.001 |

| Agreeableness | F=7.794, p=0.006, η2=0.045 | F=1.389, p=0.24, η2= 0.008 | F=0.475, p=0.492, η2= 0.003 | F=12.831, p=0.00, η2= 0.072 |

| Conscientiousness | F=7.910, p=0.006, η2=0.046 | F=4.129, p=0.044 η2= 0.024 | F=0.008, p=0.931, η2= 0.00 | F=5.857, p=0.017, η2= 0.034 |

| Extraversion | F=7.290, p=0.008, η2=0.042 | F=5.911, p=0.016, η2= 0.035 | F=3.839, p=0.052, η2= 0.023 | F=3.248, p=0.073, η2= 0.019 |

| Neuroticism | F=0.660, p=0.418, η2=0.004 | F=0.058, p=0.81, η2= 0.00 | F=1.655, p=0.20, η2= 0.01 | F=0.683, p=0.41, η2= 0.004 |

| Openness | F=2.309, p=0.131, η2=0.014 | F=0.283, p=0.595, η2= 0.002 | F=0.052, p=0.821, η2= 0.00 | F=1.796, p=0.182, η2= 0.011 |

*Wilks Lambda (λ) =0.908, F=2.713, p<0.05, η 2 = 0.092

**Wilks Lambda (λ) =0.914, F=2.497, p<0.05, η 2 = 0.086

***Wilks Lambda (λ) =0.960, F=2.712, p>0.05, η 2 = 0.040

****Wilks Lambda (λ) =0.905, F=2.800, p<0.05, η 2 = 0.095

The Levene test results regarding the equality of group variances before the analysis did not show significance in all scales (p>0.001). That is, the variances of the different groups for the scales were equal. This shows that the prerequisites for the analysis of variance are met. The test results regarding the equality of the covariance matrices of the groups regarding the dependent variables, on the other hand, show that the covariance matrices are equal, respectively (Box’s M = 17.913; 27.149; 20.598; 31.026, p > 0.01).

According to the one-way MANOVA analysis conducted to examine whether the differences between gender categories are significant, it was concluded that the average scores of the students’ personality traits and academic achievement (λ=0.908, F=2.713, p<0.05) variables differed significantly from each other. The effect size value of the categories of university students by gender was (η2=0.092). This value shows that the gender variable has a low effect on the dependent variables. As a result of MANOVA analysis, while there was a difference in terms of gender categories in agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion structures, no significant difference was found in terms of academic success, neuroticism, and openness.

According to the motivation categories (low-high), it was concluded that the average scores of the students’ personality traits and academic achievement (λ=0.914, F=2.497, p<0.05) variables differed significantly from each other. The effect size value was (η2=0.086). This value shows that motivation levels have a low effect on dependent variables. As a result of MANOVA analysis, while there was a difference in terms of motivation categories in academic success, conscientiousness, and extraversion structures, no significant difference was found in terms of agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness.

According to the engagement categories (low-high), it was concluded that the average scores of the students’ personality traits and academic achievement (λ=0.908, F=2.712, p<0.05) variables did not differ significantly from each other.

According to the interaction categories (low-high), it was concluded that the average scores of the students’ personality traits and academic achievement (λ=0.905, F=2.800, p<0.05) variables differed significantly from each other. The effect size value was (η2=0.095). This value shows that the interaction levels have a low effect on the dependent variables. As a result of MANOVA analysis, while there was a difference in terms of interaction categories in agreeableness and conscientiousness structures, no significant difference was found in terms of academic success, neuroticism, extraversion, and openness.

Discussion

Objective of this study is to determine students’ levels of academic success, motivation, engagement to learn and interaction through FC model, which is designed for information technologies lesson, and collaborative learning activities are utilized in, and to review the relationships between academic success and personality traits. In this study, effect of personality traits on academic success is reviewed through FC model in which collaborative group works are done.

Discussion Related to Research Question 1

When the descriptive results were examined, the extraversion scores of female students have the highest scores compared to other structures. It is followed by conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness, respectively. Motivation scores of female students are followed by interaction, academic success, and engagement scores. In male students, on the other hand, it was seen that the openness comes to the fore. It is followed by neuroticism, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, respectively. Engagement scores of male students are followed by academic success, interaction, and motivation scores. According to Bunker et al. (2021), the differences in behavioral norms, expectations, and beliefs between men and women are the reasons for the gender differentiation in terms of big five personality structures. In a meta-analysis study by Feingold (1994), which included long-term longitudinal findings, females were found to be significantly higher than males in all big five personality structures except openness. Schmitt et al. (2008) reached similar findings. It was seen that the findings of the study support the findings in the literature apart from the neuroticism structure. On the other hand, women’s motivation, academic achievement, interaction, and engagement scores were higher than men. The reason for this difference may be situations such as actively participating in activities in the FC model, taking responsibility, and effective communication in collaborative groups, depending on personality traits.

Low motivation students have higher openness personality scores than other personality structures. It is followed by neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness, respectively. Engagement scores of these students are followed by interaction and academic success scores. It was seen that the agreeableness personality structure comes to the fore in highly motivated students. It was followed by extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness, respectively. The academic success scores of these students are followed by interaction and engagement scores. In the collaborative FC model, the characteristics of students who are open to experience but have evaluation anxiety and see difficulties as threats may be related to low motivation. On the other hand, it is thought that agreeableness supports high motivation by positively affecting in-group dynamics in collaborative environments. Similar comments can be made for engagement and interaction levels. On the other hand, high motivation is highly correlated with variables such as academic achievement and interaction. Looking at the literature, Komarraju and Karau (2005) found that the structures that best explain the engagement motivation are openness and extraversion, and the academic motivation is conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness. Current research findings differ from the literature. The characteristics of the learning environment may be effective on the basis of these differences.

Students with a low level of engagement have the highest openness personality structure scores. This is followed by extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and agreeableness. Academic success scores are followed by motivation and interaction scores. It was seen that the agreeableness comes to the fore in students with high engagement. This is followed by neuroticism, conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness. The interaction scores of these students are followed by their interaction and academic success scores. Students with low interaction have the highest openness personality structure scores. This is followed by neuroticism, agreeableness extraversion, and conscientiousness. Academic success scores are followed by motivation and engagement scores. It was seen that the conscientiousness comes to the fore in high-engagement students. This is followed by extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness, respectively. These students’ engagement scores were followed by their motivation and academic success scores. Conscientiousness, in other words, self-control, is the personality trait that supports academic performance by the way of readiness (Steel et al., 2001). It can be interpreted as an expected result that students who have self-control in preparing for extracurricular activities have higher engagement in FC.

Discussion Related to Research Question 2

In the PLS-SEM analysis, it is reached to the result that the personality trait having the highest effect on academic success at collaborative FC is extraversion. It was found that the H1c hypothesis was supported. The results in the studies of the related literature demonstrate that the most important predictor of academic success is generally conscientiousness trait (Keller & Karau, 2013; Komarraju et al., 2011; Meyer et al., 2019; Poropat, 2009). However, in this study, importance of conscientiousness trait on academic success stayed behind of extraversion trait. Extraversion is a personality trait, which is related to the statuses of extraversion, sociality, being energetic, sociability and being excited about the chance (Costa & McCrae, 1992). It is thought that collaborative FC activities conducted within frame of this study were effective on the study results and caused difference in the result of the current research compared to previous study results. Thus, collaborative group activities were conducted for 14 weeks within the current study. Utilization of digital collaborative communication instruments was paid attention for development of students’ sociality. It was supported that students interact effectively with course sources, their teachers, and their group friends. Then, it can be said that students with dominant social skills have more positive reflections on their academic success. Thus, Zhao and Seibert (2006) indicate that individuals with extraversion trait are tended to develop active social interactions and this status reflects to motivation and engagement. Abe (2020) emphasized that extraversion is the personality structure that draws the most attention, especially for online learning environments that include communication tools.

No relationship was found between academic achievement and conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness. Therefore, it was found that the hypotheses H1a, H1b, H1d, and H1e were not supported. However, there are findings in the literature that especially conscientiousness is associated with learning performance (e.g. Keller & Karau, 2013; Komarraju et al., 2011; Poropat, 2009). This result may be related to the possibility of the relationship between personality traits and academic achievement being affected by contextual changes (e.g. Kim, 2018)). These different findings may be due to dynamics within collaborative groups, research environments, cultural differences, relationships between personality structures, learning styles, and satisfaction or participant differences towards hybrid learning. On the other hand, it was stated that students in online classes do not need to meet regularly for education at a certain place and time, that is, it can be associated with increased responsibility and uncertainty in learner time management (Keller & Karau, 2013). However, in this study, it was found that the academic achievement of the students who tended to score higher in neuroticism in this online and face-to-face education format was not significantly adversely affected. The reason for this finding can be considered as the fact that FC compensates for the disadvantages of online learning with its online and face-to-face structure.

Discussion Related to Research Question 3

One-way MANOVA analysis results show that personality traits and academic achievements differ significantly according to gender categories. While there is a difference in terms of gender categories in the constructs of agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, there is no significant difference in terms of academic success, neuroticism, and openness. According to motivation categories (low-high), personality traits and academic achievements differ significantly. While there was a difference in terms of motivation levels in academic success, conscientiousness, and extraversion structures, no significant difference was found in terms of agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness. According to the engagement categories (low-high), students’ personality traits and academic achievement did not differ significantly from each other.

According to the interaction categories (low-high), students’ personality traits and academic achievements differ significantly from each other. While there was a difference in terms of interaction categories in the structures of agreeableness and conscientiousness, no significant difference was found in terms of academic success, neuroticism, extraversion, and openness.

Limitation and Suggestion

While our study presents evidence for the efficiency of personality traits on academic performance, self-efficacy, motivation, interaction, and engagement at FC in which collaborative works are done, generalization of the findings out of the study’s scope should be carefully done. During the selection of collaborative groups, student volunteering was basic. Due to this status, it should be kept in mind that findings of the study will not provide information about to which direction the interactions of individuals having different personal traits were/will be and to which direction the consistency of the group was/will be. Because of this reason, by taking personality traits into consideration during creation of collaborative groups in future studies, effect on academic performance can be examined by way of creating homogeneous or heterogeneous groups in terms of dominant traits. Effect of personality traits on collaborative learning at FC should be examined in detail through qualitative studies. Additionally, it is necessary that schematic characteristics which can be effective to support different personality traits at FC are identified in a more detailed way and their effects are examined.

Implications

The results of this study reveal that one personality dimension in cooperative FC requires special attention: extraversion (See: Figure 6). Course content, both online and face-to-face, should allow practitioners to interact synchronously or asynchronously with their peers and teachers, supporting the extroversion feature of the collaborative FC model, especially for online learning contexts. For this, it can be suggested that teachers should diversify these interaction ways in FC, encourage students to communicate with online discussion environments, instant questions and instant feedback, in short, make more efforts to increase student communication in the learning environment. Practitioners need to focus on activities to be more reflective for introverted individuals, especially in face-to-face FC environments. In addition, online learning environments and reflection report that progress according to the asynchronous, individual pace of the online dimension can be used to support the face-to-face dimension. The research has shown that the academic self-efficacy of students in computing education carried out with the cooperative FC model differs according to the extraversion personality trait, and the extraversion personality trait is more prominent in women. From this point of view, in order to design a collaborative FC model that is extroverted and supportive of socialization, immediate feedback should be provided for students to share their learning experiences, express their thoughts freely, participate in the decision-making processes by voting with e-survey, provide more interaction, and class-wide or collaborative group discussion should be encouraged.

It was seen that academic success, interaction, agreeableness, and extraversion variables come to the fore when their motivation is high. It seems that by supporting the development of students’ motivation to learn, we can facilitate both the increase in learning performance and the potential positive effect of agreeableness and extraversion on academic achievement. It should be kept in mind that agreeableness is important in highly motivated students in order to overcome possible in-group difficulties in FC where collaborative work is carried out. Students with low levels of engagement and interaction have openness, and students with high engagement and interaction have agreeableness and conscientiousness, respectively. Since personality traits are often considered to be of a hard-to-change nature (John & Srivastava, 1999), it seems reasonable to direct educational interventions to engagement and communication preferences in FC, given that students are relatively more variable. For example, regarding agreeableness, it seems beneficial to focus on improving students’ communication preferences at school, class or parent level, according to the contextual approach, as well as their personal communication preferences. On the other hand, when components suitable for students’ personality traits are supported in FC, their decision-making processes will also be supported. As a matter of fact, personality traits are effective in students’ decision-making processes (Martincin & Stead, 2015; Penn & Lent, 2018). For example, the interaction of a student with a dependent decision-making style in cooperative groups can be supported to be more active in FC and the uncertainty in decision-making processes can be eliminated through interaction. More guidance can be given to students with this decision-making style.

Conclusion

This study examined the role of personality traits in supporting academic success through FC model in which collaborative group works are done. Our study provides evidence for the role of personality and academic performance in cooperative group work in FC. Instead of looking at the one-dimensional relationship, the changes in personality structures and academic success were examined according to gender, motivation, engagement, and interaction levels, and partial differentiations were observed according to these categories. Such differentiations may also explain the variations and inconsistencies in personality structure-performance relationships in the literature. It is also important to take into account the context-specific nature of the subject, in order to gain a better understanding of the subject.

Studies in the literature demonstrate that utilization of collaborative learning activities and FC model for improving academic success, motivation, satisfaction, interaction and engagement is beneficial (Bhagat, Chang, & Chang, 2016; Chao, Chen, & Chuang, 2015; Chen, Hwang, & Chang, 2019; Foldnes, 2016; Fox & Docherty, 2019; Gilboy, Heinerichs, & Pazzaglia, 2015; Lai & Hwang, 2016; Missildine, Fountain, Summers, & Gosselin, 2013; Munir, Baroutian, Young, & Carter, 2018; Murillo-Zamorano, Sánchez, & Godoy-Caballero, 2019; Pierce & Fox, 2012). Different from the previous studies, current study demonstrates that personality traits are in relationship with academic success at FC model in which collaborative applications are done, and effects of personality traits differentiate based on gender, motivation, interaction, and engagement. Within this context, it is possible to say that to improve the efficiency of educational processes at FC in which collaborative applications are done, taking characteristics of personality traits into consideration will be effective. This will contribute to a more productive and efficient FC process. The results will guide the applicators in how students become more readiness to learn based on the personality traits of the classrooms in which FC model is utilized. This study serves to increase the awareness of the personality traits’ effect on the issues surrounding the students’ success, motivation, and interaction behaviors during the course. To increase students’ academic performance and to overcome the difficulties about the collaborative works at FC, it is important that the relationship of personality traits with interaction and engagement is taken into consideration. The most striking result of this study is that the personality trait having the biggest effect on the academic success at collaborative FC is extraversion. This finding demonstrates that the chance of the students having extraversion trait to better utilize the means of collaborative FC to improve their academic performances is higher.

Funding

This study was not funded by any funding agencies or academic organizations.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

In addition, informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abe JAA. Big five, linguistic styles, and successful online learning. The Internet and Higher Education. 2020;45:100724. [Google Scholar]

- Akçayır G, Akçayır M. The flipped classroom: A review of its advantages and challenges. Computers & Education. 2018;126:334–345. [Google Scholar]