Abstract

Purpose:

Multigene panel testing has increased the detection of germline mutations in patients with breast cancer. The implications of using radiotherapy (RT) to treat patients with pathogenic variant (PV) mutations are not well understood and have been studied mostly in women with only BRCA1 or BRCA2 PVs. We analyzed oncologic outcomes and toxicity after adjuvant RT in a contemporary, diverse cohort of breast cancer patients who underwent genetic panel testing.

Methods and Materials:

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 286 women with clinical stage I-III breast cancer diagnosed 1995–2017 who underwent surgery, breast or chest wall RT with or without regional nodal irradiation, multigene panel testing, and evaluation at a large cancer center’s genetic screening program. We evaluated rates of overall survival (OS), locoregional recurrence (LRR), disease-specific death (DSD), and radiation-related toxicities in three groups: BRCA1/2 PV carriers, non-BRCA1/2 PV carriers, and patients without PV mutations.

Results:

PVs were detected in 25.2% of the cohort (12.6% BRCA1/2 and 12.6% non-BRCA1/2). The most commonly detected non-BRCA1/2 mutated genes were ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, CDH1, TP53, and PTEN. The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 4.4 years (95% confidence interval 3.8–4.9 years). No differences were found in OS, LRR, or DSD between groups (P>0.1 for all). Acute and late toxicities were comparable across groups.

Conclusion:

Oncologic and toxicity outcomes after RT in women with PV germline mutations detected by multigene pane testing are similar to those in patients without detectable mutations, supporting the use of adjuvant RT as a standard of care when indicated.

Introduction

Approximately 5%−10% of breast cancer cases have been linked with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (BRCA1/2),1 and 20%−30% of cases have been linked with other hereditary breast cancer (HBC)-associated genes.2,3 BRCA1/2 has a central role in DNA damage repair, which has implications for both oncogenesis and therapeutic response, including the repair of radiation-induced double-strand breaks.4 From a radiobiological perspective, concern has been expressed that defective DNA repair mechanisms may confer radiosensitivity to both tumors and normal tissues, which may lead to better tumor control but more second cancers and toxicity after radiotherapy (RT).5 Compared to outcomes in patients with a BRCA1/2 germline mutation,6–8 relatively little has been published on RT-induced sequelae among patients with mutations in non-BRCA1/2 HBC DNA repair genes such as ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, and RAD50/51 which are often tested on multigene panels.

Advances in DNA sequencing technology have enhanced the time- and cost-effectiveness of multigene panel testing9 and gene sequencing patents being overturned10 have both increased the use of multigene panel testing. Expanded gene panels provide a more comprehensive genetic risk assessment when a hereditary link to breast cancer is suspected. As a result, the American Society of Breast Surgeons recently called for universal germline panel testing for all patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer.11 However, enthusiasm for multigene panel testing has outpaced the data to guide RT-related clinical decision-making in this setting. The goal of this study was to evaluate oncologic outcomes and RT-related toxicity in a diverse group of breast cancer patients who underwent panel germline mutation testing.

Methods

After institutional review board approval, we searched our institutional databases for women ≥18 years old treated with definitive surgery and adjuvant external-beam RT for clinical stage I-III breast cancer who also underwent multigene panel testing and were evaluated at the ***. We analyzed three groups: carriers of any BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant (PV; “BRCA1/2 mut”), carriers of non-BRCA1/2 PVs (“other mut”) only, and patients with no detectable PV mutation (“no mut”) who may harbor variants of unknown significance (VUS). Multigene panel testing was defined as germline evaluation for a minimum of BRCA1/2 and at least one other gene.

Tumors were categorized according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual 7th edition.12 In cases of synchronous, bilateral breast cancers, the higher clinical stage cancer was recorded as the index primary cancer. RT-related toxicities were recorded per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0. Acute toxicities were those that occurred during or within the first 3 months of radiotherapy.

Categorical variables were compared by using X2 or Fisher’s exact tests; continuous variables were compared by using t tests. Time intervals were measured from the date of definitive surgery for the index breast cancer. Locoregional recurrence (LRR) was defined as clinically or pathologically confirmed disease recurrence in the ipsilateral breast/chest wall and/or draining lymphatics. Patients with >1 year of follow-up after breast surgery were included. Rates of LRR and DSD were estimated by the method of cumulative incidence, with death considered a competing risk; outcomes based on mutational status were compared by using Gray’s test. Actuarial probabilities of overall survival (OS) were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level α=0.05. Analyses were performed via SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), Splus 8.2 (TIBCO Software Inc, Palo Alto, CA), and R 2.15.1.

Results

Patients

We identified 286 women diagnosed from 1995 through 2017 who met the inclusion criteria; clinicopathologic features by mutation group are detailed in Table 1. Thirty-six percent of the cohort (104/286) self-reported as non-white, 15% as African American/Black, 14% Hispanic/Latino, and 8% Asian/American Indian/Alaska Native. Patients with any PV had higher clinical stage disease (stage III: BRCA1/2 42% vs. other mut 42% vs. no mut 26%; P=0.02). A greater proportion of the BRCA1/2 PV group underwent mastectomy (83% vs. 53% other mut and 42% no mut, P<0.001) and chest wall and regional nodal irradiation (83% vs. 53% other mut and 42% no mut, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic patient characteristics

| Characteristic | No. patients (%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BRCA1/2 mut (N=36) |

Other mut (N=36) |

No mut (N=214) |

||

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤40 | 15 (42) | 11 (31) | 75 (35) | 0.61 |

| >40 | 21 (58) | 25 (69) | 139 (65) | |

| Race | ||||

| Asian or American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 18 (8) | 0.28 |

| Black/African American | 7 (19) | 3 (8) | 32 (15) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6 (17) | 2 (6) | 32 (15) | |

| White | 20 (56) | 30 (83) | 132 (62) | |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Pre | 26 (72) | 24 (67) | 141 (66) | 0.76 |

| Post* | 10 (28) | 12 (33) | 73 (34) | |

| Clinical T status | ||||

| T0/Tis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0.21 |

| T1 | 7 (19) | 9 (25) | 80 (37) | |

| T2 | 17 (47) | 15 (42) | 87 (41) | |

| T3 | 9 (25) | 9 (25) | 27 (13) | |

| T4 | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 15 (7) | |

| Unknown** | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | |

| Clinical nodal status | ||||

| N0 | 26 (72) | 21 (58) | 99 (47) | 0.01 |

| N+ | 10 (28) | 15 (42) | 112 (53) | |

| Unknown** | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | |

| Overall clinical stage | ||||

| I | 4 (11) | 6 (17) | 68 (32) | 0.02 |

| II | 17 (47) | 15 (42) | 90 (42) | |

| III | 15 (42) | 15 (42) | 56 (26) | |

| Pathologic T status | ||||

| T0/Tis | 10 (28) | 7 (19) | 47 (22) | 0.19 |

| T1 | 11 (31) | 9 (25) | 86 (40) | |

| T2 | 10 (28) | 10 (28) | 55 (26) | |

| T3 | 4 (11) | 10 (28) | 21 (10) | |

| T4 | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | |

| Pathologic nodal status | ||||

| N0 | 19 (53) | 22 (61) | 85 (40) | 0.03 |

| N+ | 17 (47) | 14 (39) | 129 (60) | |

| Overall pathologic stage | ||||

| 0 | 10 (28) | 6 (17) | 39 (18) | 0.01 |

| I | 4 (11) | 4 (11) | 70 (33) | |

| II | 14 (39) | 14 (39) | 66 (31) | |

| Hormone receptor status | ||||

| Positive | 25 (69) | 28 (78) | 150 (70) | 0.63 |

| Negative | 11 (31) | 8 (22) | 64 (30) | |

| Her2-neu status | ||||

| Positive | 3 (8) | 8 (22) | 49 (23) | 0.11 |

| Negative | 33 (92) | 28 (78) | 160 (77) | |

| Unknown** | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | |

| TNBC status | ||||

| TNBC | 11 (31) | 8 (22) | 40 (19) | 0.26 |

| Non-TNBC | 25 (69) | 28 (78) | 173 (81) | |

| Unknown** | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Nuclear grade | ||||

| I-II | 13 (36) | 19 (53) | 100 (47) | 0.33 |

| III | 23 (64) | 17 (47) | 111 (52) | |

| Unknown** | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | |

| LVSI | ||||

| Yes | 10 (29) | 10 (28) | 44 (20.6) | 0.48 |

| No | 25 (71) | 26 (72) | 164 (76.6) | |

| Unknown** | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.8) | |

| Year of surgery | ||||

| ≤2000 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (7) | 0.09 |

| 2001–2010 | 4 (11) | 5 (14) | 44 (21) | |

| 2011–2017 | 32 (89) | 31 (86) | 155 (72) | |

| Type of definitive surgery | ||||

| Breast conserving surgery | 6 (17) | 17 (47) | 125 (58) | <0.001 |

| Mastectomy | 30 (83) | 19 (53) | 89 (42) | |

| No. positive nodes | ||||

| <10 | 2 (6) | 3 (8) | 11 (5) | 0.69 |

| ≥10 | 34 (94) | 33 (92) | 203 (95) | |

| No. nodes removed | ||||

| <10 | 27 (75) | 23 (64) | 110 (51) | 0.02 |

| ≥10 | 9 (25) | 13 (36) | 104 (49) | |

| Radiation type | ||||

| Breast | 4 (11) | 8 (22) | 88 (41) | <0.001 |

| Breast+RNI | 2 (6) | 9 (25) | 37 (17) | |

| CW only | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| CW+RNI | 30 (83) | 19 (53) | 88 (41) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 26 (72) | 20 (56) | 106 (50) | 0.04 |

| No | 10 (28) | 16 (44) | 108 (50) | |

| Any chemotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 33 (92) | 33 (92) | 171 (80) | 0.08 |

| No | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 43 (20) | |

| Adjuvant hormone therapy | ||||

| Yes | 22 (61) | 26 (73) | 141 (66) | 0.60 |

| No | 14 (39) | 10 (28) | 73 (34) | |

| Synchronous contralateral breast cancer | ||||

| Yes | 2 (6) | 3 (8) | 6 (3) | 0.13 |

| No | 34 (94) | 33 (92) | 208 (97) | |

Patients who had a prophylactic or therapeutic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at the time of diagnosis were considered post-menopausal.

Patients with unknown status were omitted from statistical analyses.

Abbreviations: CW, chest wall; LVSI, lymphovascular space invasion; RNI, regional nodal irradiation; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

12.6% of the women (36/286) were found to have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 PV mutation and 12.6% (36/286) a non-BRCA1/2 PV mutation (Table 2); one patient had PVs in both BRCA1 and ATM and another had PVs in both BRCA2 and MUTYH. The most commonly detected non-BRCA1/2 PVs were CHEK2 (8/215), ATM (8/216), and PALB2 (5/228). Two patients with ATM PVs also had a RAD50 and a CHEK2 PV. Other commonly tested genes with lower positivity rates included TP53 (3/282), PTEN (1/279), and CDH1 (0/262). Sixty-two patients (22%) received hypofractionated radiotherapy; of those with a PV mutation, 8 (11%) received hypofractionated radiotherapy.

Table 2.

Pathogenic variant mutations identified in multigene panel testing

| Gene | No. pathogenic variant mutations identified/No. patients tested (%) |

|---|---|

| AIP | 0/1 |

| ALK | 0/2 |

| ANKRD26 | 0/1 |

| APC | 0/55 |

| ATM | 8/216 (4)*, ǁ |

| AXIN2 | 0/9 |

| BAP1 | 0/5 |

| BARD1 | 1/94 (1)* |

| BLM | 0/2 |

| BMPR1A | 0/54 |

| BRCA1 | 10/286 (4)* |

| BRCA2 | 26/286 (9)* |

| BRIP1 | 4/102 (4)* |

| CASR | 0/1 |

| CDC73 | 0/2 |

| CDH1 | 0/262 |

| CDK4 | 0/53 |

| CDKN1B | 0/2 |

| CDKN1C | 0/2 |

| CDKN2A | 0/54 |

| CEBPA | 0/2 |

| CHEK2 | 8/215 (4)* |

| CTNNA1 | 0/1 |

| DDX41 | 0/1 |

| DICER1 | 0/5 |

| DIS3L2 | 0/2 |

| EGFR | 0/1 |

| EPCAM | 0/88 |

| ETV6 | 0/1 |

| FANCC | 0/6 |

| FH | 0/7 |

| FLCN | 0/6 |

| GALNT12 | 0/3 |

| GATA2 | 0/2 |

| GPC3 | 0/2 |

| GREM1 | 0/35 |

| HOXB13 | 0/12 |

| HRAS | 0/1 |

| KIT | 0/2 |

| MAX | 0/5 |

| MEN1 | 0/6 |

| MET | 0/6 |

| MITF | 0/5 |

| MLH1 | 1/93 (1)** |

| MRE11A | 0/39 |

| MSH2 | 0/92 |

| MSH3 | 0/4 |

| MSH6 | 0/91 |

| MUTYH | 2/90 (2)*** |

| NBN | 0/102 |

| NF1 | 0/53 |

| NF2 | 0/1 |

| NTHL1 | 0/3 |

| PALB2 | 5/228 (2)* |

| PDGFRA | 0/2 |

| PH0X2B | 0/2 |

| PMS2 | 1/89 (1)** |

| P0LD1 | 0/41 |

| POLE | 0/39 |

| P0T1 | 0/3 |

| PRKAR1A | 0/2 |

| PTCH1 | 0/2 |

| PTEN | 1/279 (0.4)ǂ |

| RAD50 | 1/41 (2)* |

| RAD51C | 1/103 (1)* |

| RAD51D | 0/102 |

| RB1 | 0/2 |

| RECQL | 0/2 |

| RECQL4 | 0/1 |

| RET | 0/5 |

| RNF43 | 0/2 |

| RPS20 | 0/2 |

| RUNX1 | 0/2 |

| SDHA | 0/5 |

| SDHAF2 | 0/6 |

| SDHB | 0/8 |

| SDHC | 0/8 |

| SDHD | 1/6 (17)ǂ |

| SMAD4 | 0/54 |

| SMARCA4 | 0/10 |

| SMARCB1 | 0/3 |

| SMARCE1 | 0/3 |

| SRP72 | 0/1 |

| STK11 | 0/134 |

| SUFU | 0/2 |

| TERC | 0/2 |

| TERT | 0/2 |

| TMEM127 | 0/5 |

| TP53 | 3/282 (1)ǂ |

| TSC1 | 0/7 |

| TSC2 | 0/7 |

| VHL | 1/11 (9)ǂ |

| WRN | 0/1 |

| WT1 | 0/2 |

Gene function:

Double Stranded DNA Damage Repair via Homologous Recombination;

DNA Repair via Mismatch Repair,

DNA Repair via Base Excision Repair,

Tumor Suppressor,

DNA Repair via Non-Homologous End Joining

Outcomes

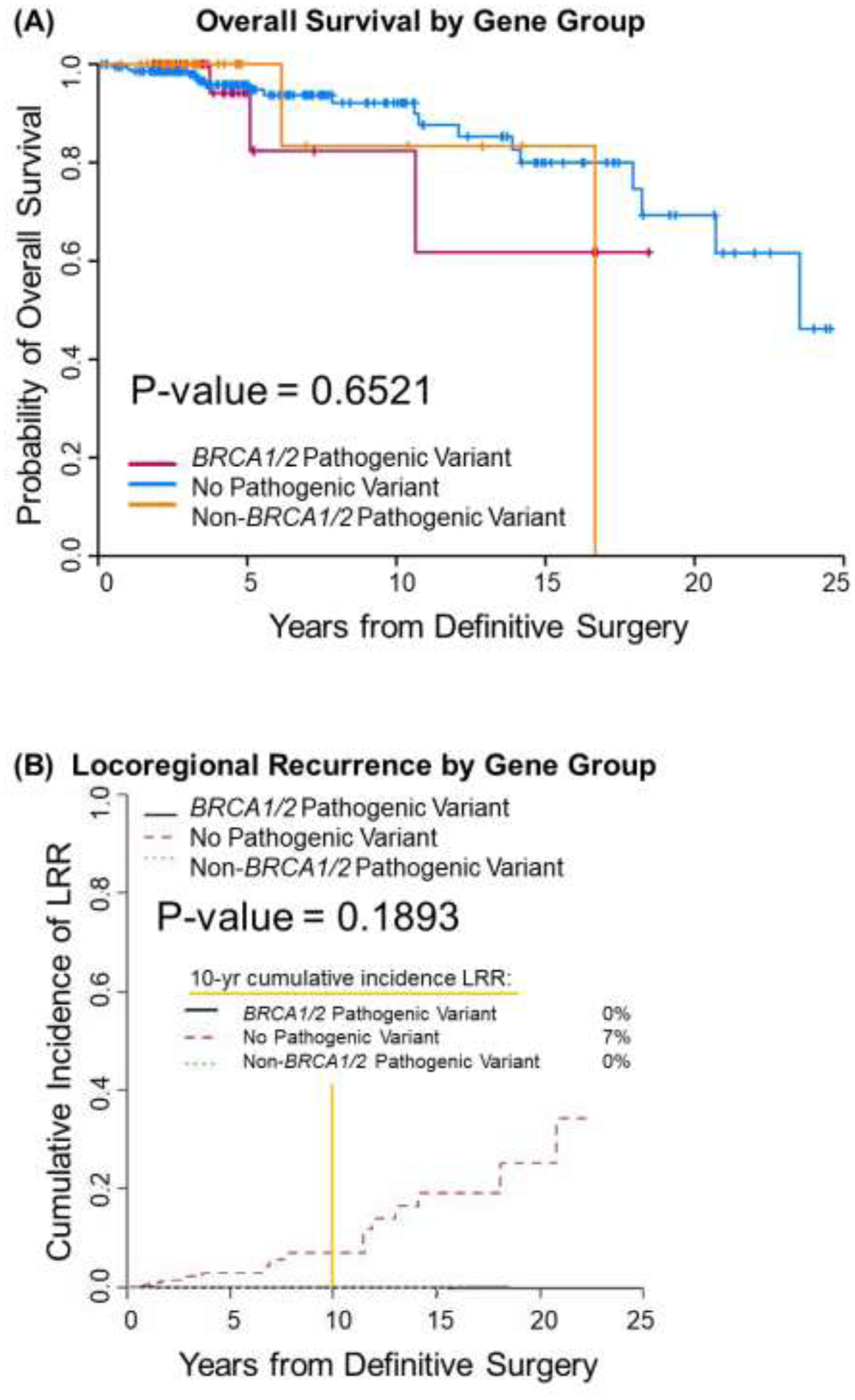

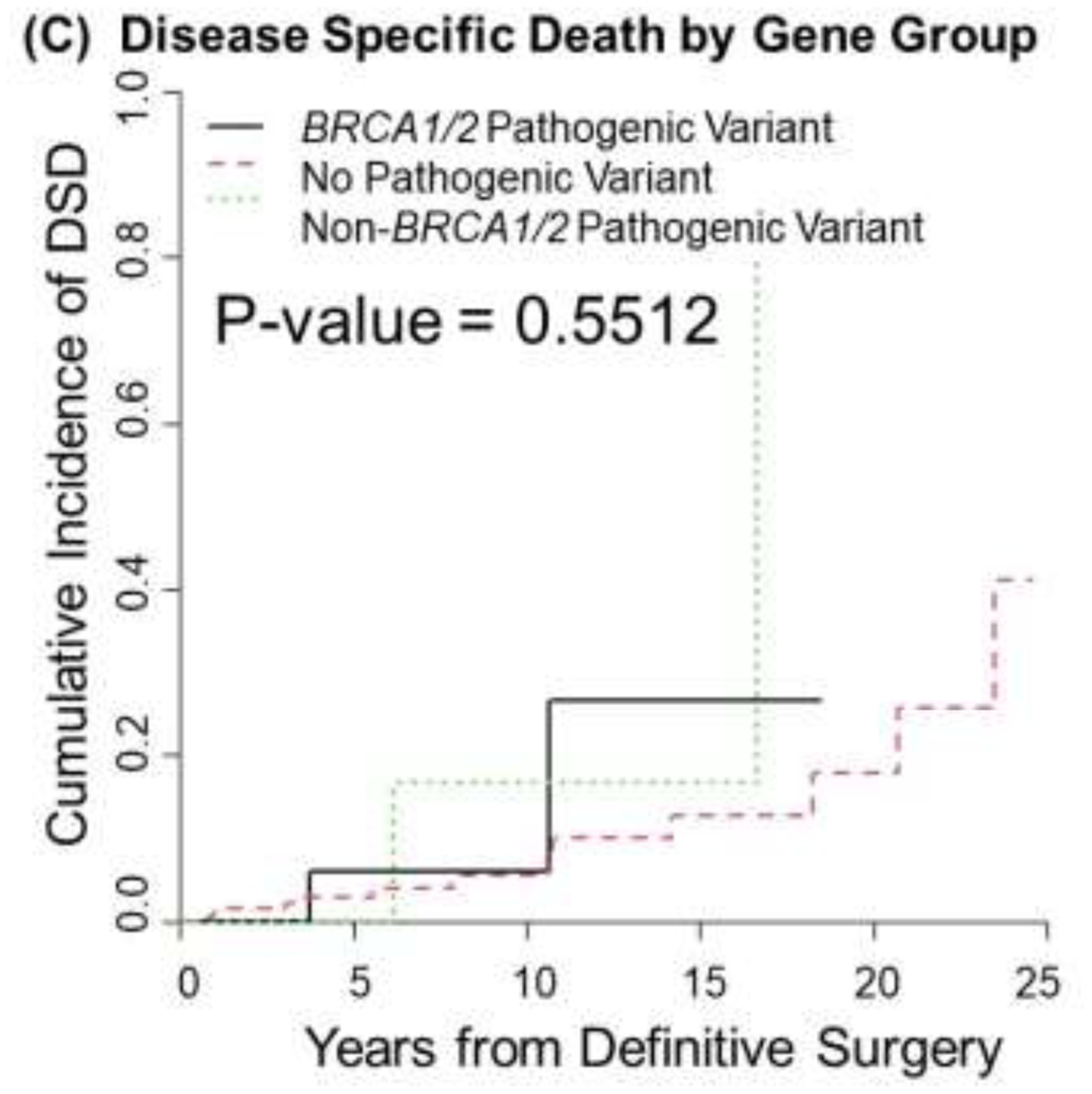

The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 4.4 years (95% confidence interval 3.8–4.9 years). No differences were found among the three mutation groups in OS (P=0.65), LRR (P=0.19), or DSD (P=0.55) (Fig. 1 A–C). Ten-year overall survival rates were 0.82, (95% CI: 0.43, 0.96), 0.83 (95% CI: 0.27, 0.97), and 0.92 (95% CI: 0.85, 0.96) in the BRCA1/2 mut, other mut, and no mut groups, respectively. No patients in the BRCA1/2 mut or other mut groups experienced LRR, whereas the 10-year cumulative incidence of LRR was 7% (95% CI 2–12%) in the no mut group. Ten-year DSD rates were 6% (95% CI 0–17%) for the BRCA1/2 mut group, 17% (95% CI 0–49%) for the other mut group, and 5% (95% CI: 1–10%) for the no mut group. The small number of events precluded univariate and multivariable analyses. Acute and late toxicities as well as second cancers were comparable between groups (Table 3). Any acute grade ≥2 toxicity, the vast majority of which were skin toxicities, was seen in 36% of the BRCA1/2 mut group, 42% of the other mut group, and 39% of the no mut group (p=0.89). Any late grade ≥2 toxicity was seen in 3% of the BRCA1/2 mut patients (skin toxicity), 3% of the other mut patients (lymphedema), and 4% of those with no mut (skin and fatigue) (p=1.00)

Fig 1.

Overall survival (A), locoregional recurrence (B), and disease specific death (C) by genetic mutation status as detected by panel testing.

Table 3.

Toxicities and second cancers

| Grade and Type of Toxicity | No. patients (%) | P- Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BRCA1/2 mut (N=36) |

Other mut (N=36) |

No mut (N=214) |

||

| Any acute | ||||

| 0–1 | 23 (64%) | 21 (58%) | 130 (61%) | 0.89 |

| ≥2 | 13 (36%) | 15 (42%) | 84 (39%) | |

| Acute skin | ||||

| 0–1 | 23 (64%) | 26 (72%) | 133 (62%) | 0.51 |

| ≥2 | 13 (36%) | 10 (28%) | 81 (38%) | |

| Acute breast pain, atrophy, or edema | ||||

| 0–1 | 35 (97%) | 34 (94%) | 211 (99%) | 0.17 |

| ≥2 | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | 3 (1%) | |

| Acute other | ||||

| 0–1 | 36 (100%) | 32 (89%) | 212 (99%) | 0.01 |

| ≥2 | 0 (0%) | 4 (11%)* | 2 (1%)** | |

| Any late | ||||

| 0–1 | 35 (97%) | 35 (97%) | 205 (96%) | 1.00 |

| ≥2*** | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 9 (4%) | |

| Late skin | ||||

| 0–1 | 35 (97%) | 36 (100%) | 206 (96%) | 0.85 |

| ≥2 | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (4%) | |

| Late breast pain, atrophy, or edema | ||||

| 0–1 | 36 (100%) | 36 (100%) | 214 (100%) | — |

| ≥2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Late other | ||||

| 0–1 | 36 (100%) | 35 (97%) | 213 (99.5%) | 0.44 |

| ≥2 | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%)ǂ | 1 (0.5%)ǂǂ | |

| Second Cancers | ||||

| Any | 2 (5.5%) | 2 (5.5%) | 17 (7.9%) | |

| Central Nervous System Cancer | 2 | |||

| Colorectal Cancer | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gastric Cancer | 1 | |||

| Genitourinary Cancer | 1° | 3 | ||

| Gynecologic Cancer (Non-Ovarian) | 1 | 4 | ||

| Hematologic Cancer | 1 | |||

| Lung Cancer | 1°° | |||

| Sarcomas thought to be RT-associated | 3 | |||

| Thyroid Cancer | 2 | |||

Shingles in a patient with a PTEN PV, fatigue in 2 patients with CHEK2 PV and 1 patient with a RAD51C PV.

Fatigue and shoulder arthralgia

Lymphedema in a patient with a PALB2 PV

Fatigue

No grade ≥3 late toxicities were observed, and no cardiac or pulmonary toxicities were reported.

Patient with a TP53 PV

Patient with an ATM PV

Discussion

Expanded genetic testing in breast cancer patients can identify significantly more carriers of mutations in HBC genes beyond BRCA1/2.13 The increased use of multigene panel testing brings both opportunities and challenges, including if and how results should be integrated into treatment paradigms. Breast radiotherapy is a well-tolerated adjuvant therapy with minor long-term adverse effects.14 Nevertheless, a recent population-based cohort study demonstrated that women with PV mutations in HBC genes are less likely to receive guideline-concordant care for early-stage breast cancer, with omission of RT more common for mutation carriers than non-carriers.15

Recently, the American Society of Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) convened expert panels to devise guidelines for the use of RT in patients with germline mutations.16–18 The ASTRO Think Tank advised that the presence of BRCA1/2, PALB2, CHEK2, and RAD50/51 mutations should not influence RT decisions, but that RT should be considered with caution for patients with certain ATM PVs.16, 18–19 Reassuringly, the findings of the current study are in line with these recommendations. We report that oncologic outcomes and complications after RT in women with multigene panel-detected PVs are similar to those in women without known mutations in spite of advanced stage in the PV cohorts.

Limitations of this study include the low numbers of detected non-BRCA1/2 mutations, which is a function of both the heterogeneity in multigene panels over the study period and the low incidence of HBCs. The scope of this study did not permit analysis of specific allelic mutations and outcomes. Further, the retrospective study design has inherent biases with regard to toxicity collection in addition to selection, follow-up, and survival biases. Nevertheless, this study provides real-world clinical data that address the sequelae of RT in a diverse group of patients with germline mutations, and additional large-scale, prospective data from such patients is warranted.

Conclusions

Oncologic outcomes and toxicities after adjuvant RT in women with breast cancer and PV germline mutations detected by multigene panel testing are similar to those in patients without known mutations, supporting the use of RT when clinically indicated. Further mechanistic studies investigating the relationship between specific genetic perturbations and RT response may guide more informed clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Christine F. Wogan, MS, ELS, from MD Anderson’s Division of Radiation Oncology for editorial assistance.

Funding:

Supported in part by the Assessment, Intervention and Measurement (AIM) Shared Resource through a Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016672, PI: P. Pisters, MD Anderson Cancer Center) and the Biostatistics Research Group Cancer Center Support Grant (5P30CA016672-44, PI: J, Lee, MD Anderson Cancer Center) from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health

Conflict of Interests:

The authors report the following support present during the 36 months prior to publication, all of which are for activities outside the submitted work. Drs. Shaitelman and Sawakuchi report research support from the NIH (R21CA252411), Emerson Collective Foundation, Alpha Tau, and Artios Pharma. Drs. Shaitelman, Sawakuchi and Bright are supported by a research grant from TAE Life Sciences. Dr. Sawakuchi reports research support from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas. Dr. Shaitelman reports contracted research support from Exact Sciences. Drs. Hoffman and Smith have a research grant from Varian Medical Systems. Dr. Smith has royalty and equity interest in Oncora Medical. Dr. Litton is involved with research supported by Pfizer/medivation, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Merck, Jounce, and EMD Serono; she also serves on guideline committees for ASCO, NCCN and SITC. Dr. Stecklein reports non-financial support from Myriad Genetics. Dr. Woodward has received fees from Exact Sciences and Epic Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability:

De-identified research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Narod SA, Foulkes WD. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(9):665–676. doi: 10.1038/nrc1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filippini SE, Vega A. Breast cancer genes: beyond BRCA1 and BRCA2. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2013;18:1358–1372. doi: 10.2741/4185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stratton MR, Rahman N. The emerging landscape of breast cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40(1):17–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN. BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2012;12(1):68–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc3181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernier J, Poortmans P. Clinical relevance of normal and tumour cell radiosensitivity in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: A review. The Breast. 2015;24(2):100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, et al. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. 1990;250(4988):1684–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2270482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narod SA, Feunteun J, Lynch HT, et al. Familial breast-ovarian cancer locus on chromosome 17q12-q23. Lancet. 1991;338(8759):82–83. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wooster R, Neuhausen SL, Mangion J, et al. Localization of a breast cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2, to chromosome 13q12–13. Science. 1994;265(5181):2088–2090. doi: 10.1126/science.8091231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun L, Brentnall A, Patel S, et al. A Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Multigene Testing for All Patients With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1718. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.12–398 Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc. (06/13/2013) Published online 2013:22.

- 11.Manahan ER, Kuerer HM, Sebastian M, et al. Consensus Guidelines on Genetic` Testing for Hereditary Breast Cancer from the American Society of Breast Surgeons. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3025–3031. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07549-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene F, Trotti A, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook: From the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. Springer-Verlag; 2010. Accessed May 15, 2021. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9780387884424 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desmond A, Kurian AW, Gabree M, et al. Clinical Actionability of Multigene Panel Testing for Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk Assessment. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(7):943–951. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whelan TJ, Olivotto IA, Parulekar WR, et al. Regional Nodal Irradiation in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(4):307–316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurian AW, Ward KC, Abrahamse P, et al. Association of Germline Genetic Testing Results With Locoregional and Systemic Therapy in Patients With Breast Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(4):e196400. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.6400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergom C, West CM, Higginson DS, et al. The Implications of Genetic Testing on Radiation Therapy Decisions: A Guide for Radiation Oncologists. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(4):698–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tung NM, Boughey JC, Pierce LJ, et al. Management of Hereditary Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology Guideline. JCO. 2020;38(18):2080–2106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trombetta MG, Dragun A, Mayr NA, Pierce LJ. ASTRO Radiation Therapy Summary of the ASCO-ASTRO-SSO Guideline on Management of Hereditary Breast Cancer. Practical Radiation Oncology. 2020;10(4):235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2020.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiner AS, Robson ME, Mellemkjær L, et al. Radiation Treatment, ATM, BRCA1/2, and CHEK2*1100delC Pathogenic Variants and Risk of Contralateral Breast Cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2020;112(12):1275–1279. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.