Abstract

Brain kappa-opioid receptors (KORs) are implicated in the pathophysiology of depressive and anxiety disorders, stimulating interest in the therapeutic potential of KOR antagonists. Research on KOR function has tended to focus on KOR-expressing neurons and pathways such as the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. However, KORs are also expressed on non-neuronal cells including microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain. The effects of KOR antagonists on microglia are not understood despite the potential contributions of these cells to overall responsiveness to this class of drugs. Previous work in vitro suggests that KOR activation suppresses proinflammatory signaling mediated by immune cells including microglia. Here, we examined how KOR antagonism affects microglia function in vivo, together with its effects on physiological and behavioral responses to an immune challenge. Pretreatment with the prototypical KOR antagonist JDTic potentiates levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1ß, IL-6) in blood following administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an immune-activating agent, without triggering effects on its own. Using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACs), we found that KOR antagonism potentiates LPS-induced cytokine expression within microglia. This effect is accompanied by potentiation of LPS-induced hyperthermia, although reductions in body weight and locomotion were not affected. Histological analyses confirm that LPS produces visible changes in microglia morphology consistent with activation, but this effect is not altered by KOR antagonism. Considering that inflammation is increasingly implicated in depressive and anxiety disorders, these findings raise the possibility that KOR antagonist actions on microglia may detract from actions on neurons that contribute to their therapeutic potential.

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing evidence that psychiatric conditions may involve the immune system. In major depressive disorder (MDD) several of the strongest genetic associations (Levey et al., 2021) and several of the pathways most consistently dysregulated are key components of the immune system (Wittenberg et al., 2020). Cytokines are altered in MDD (Miller et al., 2009) and in animal models frequently used to study depression (Hodes et al., 2014). Further, direct administration of proinflammatory cytokines can produce depressive-like behaviors in animal models, and depression is a common side-effect of treatment with the proinflammatory cytokines interferons (Lotrich, 2009). As such, the regulation of these proinflammatory pathways in the brain may be an important aspect of the underlying mechanisms of MDD as well as other stress and anxiety-related disorders (Haroon et al., 2017; Menard et al., 2017).

Microglia are the resident immune cells in the brain, and there is increasing appreciation that they can have broad roles in the regulation of synaptic connections, cell death, and neuronal activity (Carlezon and Missig, 2021; Prinz et al., 2019). Although microglia are the major source of proinflammatory cytokines in the brain, many cytokines readily cross the blood-brain barrier, creating a complex and potentially bidirectional relationship between peripheral and central immune responses. There are multiple mechanisms by which the nervous system and immune system may interact, including through the release of neuropeptides. Multiple immune cell types, including microglia, appear to express multiple neuropeptide receptors and exhibit an array of diverse responses following activation these receptors (Souza-Moreira et al., 2011). As such neuropeptide systems are emerging as potentially important mechanism in immune regulation in the central nervous system.

The kappa opioid receptor (KOR) is an inhibitory (Gi protein-coupled) receptor that is endogenously activated by dynorphin (Chavkin et al., 1982). KORs are highly expressed in the nucleus accumbens (NAc), a brain region in which dynorphin is upregulated by stress (for review, see (Knoll and Carlezon, 2010; Van’t Veer and Carlezon, 2013). Activation of NAc KORs can lead to inhibition of local dopamine release, an effect implicated in anhedonia and other depressive-like signs (Muschamp et al., 2012; Van’t Veer and Carlezon, 2013). Administration of KOR antagonists produces antidepressant and anxiolytic-like effects in models used to study these conditions, the presumed mechanism of which is blockade of KOR-mediated suppression of mesocorticolimbic dopamine system function (for review, see Muschamp and Carlezon, 2013). Such findings have triggered interest in the role for KOR regulation of the neural circuits of motivation and emotion as well as the potential utility of KOR antagonists for treating mood and anxiety disorders (Carlezon and Krystal, 2016; Carroll and Carlezon, 2013). Indeed, reports on early clinical trials of KOR antagonists for the treatment of MDD suggest some efficacy in reducing anhedonia, a key sign of the condition (Krystal et al., 2020; Pizzagalli et al., 2020).

In contrast, the roles of KORs on microglia and other non-neuronal cells has not been studied thoroughly. Previous studies suggest that KORs are expressed on microglia, and that activation of microglial KORs in vitro suppresses proinflammatory signaling (Chao et al., 1996; Feng et al., 2014). Beyond these studies, however, very little is known about interactions among KORs, inflammation, and stress-related conditions. Here, we examined in male mice how KOR antagonism affects inflammatory responses at baseline and following administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Specifically, we used the prototypical selective KOR antagonist JDTic to examine the effects of KOR function on LPS-induced peripheral immune responses (by measuring proinflammatory cytokines in the blood) and central immune responses (by isolating microglia and evaluating changes in the expression of genes encoding proinflammatory factors). In parallel, we also examined physiological and behavioral responses (by using biotelemetry to measure body temperature and locomotor activity) and microglia morphology (by using immunohistochemistry and microstructural analyses) to explore possible mechanisms.

METHODS

Animals

Male C57Bl/6J mice 8–10 weeks old were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The mice were housed under a 12-hour light and 12-hour dark schedule temperature (21 ± 2C and humidity (50 ± 20%), and food and water were available ad libitum throughout the duration of the experiment. Following arrival at McLean Hospital, the mice were given seven days to recover and habituate to the vivarium prior to starting the experiment. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at McLean Hospital.

Drug Administration Paradigm

Mice were pretreated with intraperitoneal (IP) JDTic (30 mg/kg; synthesized by F. I. Carroll) or saline vehicle, followed 24 hours later by LPS (0.5 mg/kg, IP; E.Coli 0111:B4, Sigma) or saline vehicle. In mice, this JDTic dose and pretreatment period have been shown previously to produce anti-stress effects (Wells et al., 2017). For studies focusing on gene analyses, mice were euthanized with isoflurane 3 hours after LPS (6 hours into the light phase) and cardiac puncture was used to collect blood, followed by transcardial perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and brain extraction for microglia isolation (Fig. 1A). For studies focusing on vivo endpoints, mice were implanted IP with wireless transmitters as described (Missig et al., 2020) (see below), enabling continuous collection of telemetry (locomotor activity, body temperature) without tethering. After seven days of recovery, baseline measurements were recorded continuously for 72 hours before administration of JDTic (or saline) and LPS (or saline) exactly as performed in the gene expression studies. In addition, 24 hr after these studies, the mice were euthanized with isoflurane and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde for immunohistochemistry analyses (Fig. 1B).

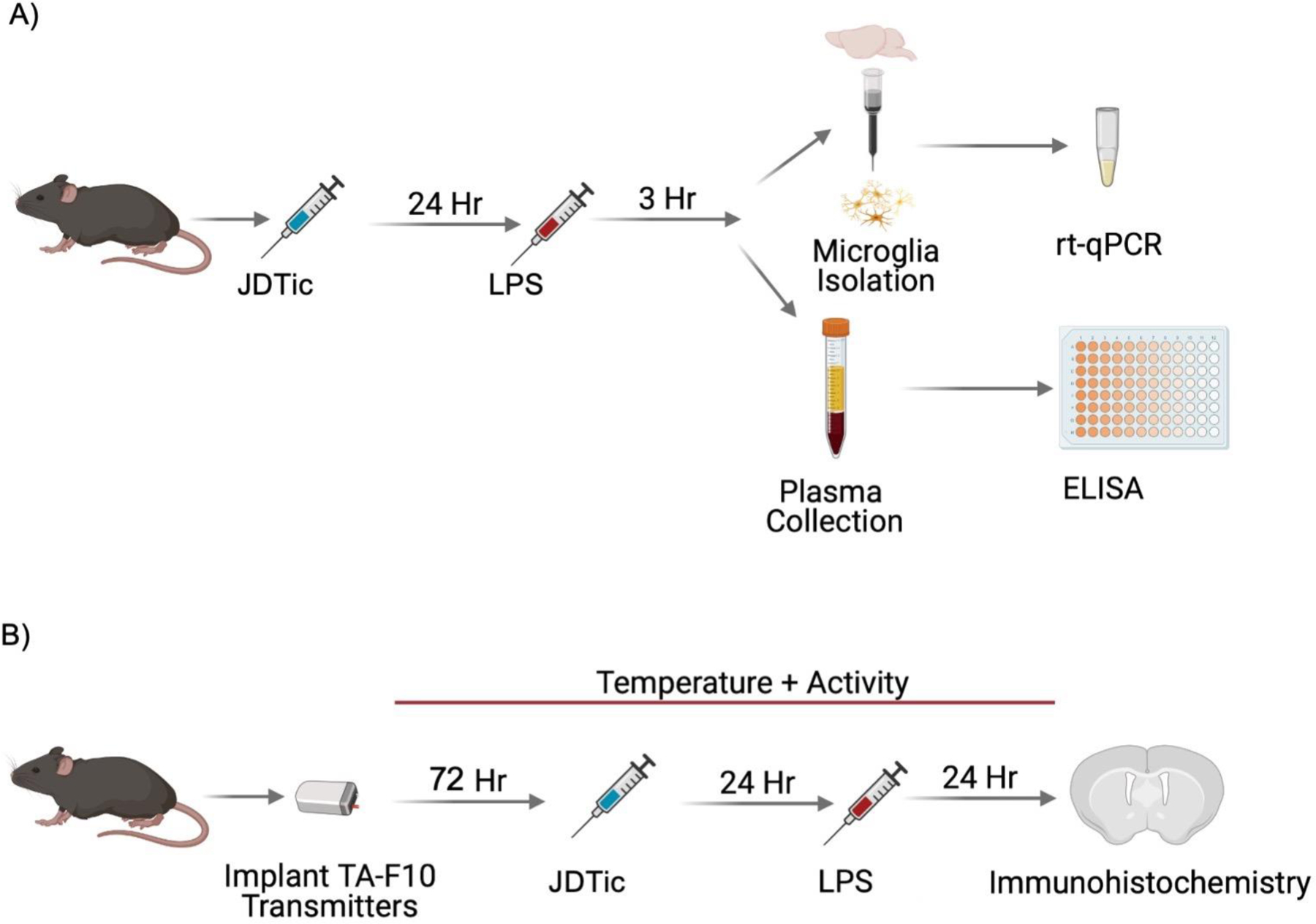

Fig. 1: Experimental paradigms.

Male C57BL/6J mice underwent in one of two experimental paradigms. A) Mice were administered JDTic (30mg/kg, IP) or saline and then 24 hours later received either LPS (0.5mg/kg, IP) or saline. Three hours later, blood was collected via cardiac puncture and then mice were transcardially perfused with PBS and whole brains were processed into a single-cell suspension for microglia isolation and analysis with qPCR. Blood was analyzed for proinflammatory cytokines using ELISAs. B) Mice were implanted with wireless telemetry devices that measure body temperature and locomotor activity and allowed seven days to recover. Transmitters were turned on and 72 hours of baseline was recorded before injection with JDTic (30mg/kg, IP) or saline. 24 hours later LPS (0.5mg/kg, IP) or saline was administered and then 24 hours later mice were perfused for microglia histological analysis.

Transmitter implantation

Radiotelemetry transmitters (TA-F10, Data Science International [DSI], St Paul, MN) were implanted under ketamine/xylazine (100/10 mg/kg, IP) anesthesia according to manufacturer’s instructions, as described (Missig et al., 2020). Mice were immobilized and an incision was made into the intraperitoneal cavity where transmitters were implanted. Wound was closed with silk sutures internally and wound clips externally. Mice received a post-surgery analgesic (ketoprofen 5 mg/kg) for the first 48 hours following surgery. They were allowed at least seven days in a singly housed plexiglass cage prior to the start of the experiment.

Analysis of Locomotor Activity and Body Temperature

Mice were singly house in a standard mouse cage on top of an RPC-1 PhysioTel receiver (DSI), which detected signal from the transmitters. The receivers were connected to a data exchange matrix (DSI) that continuously uploaded recording data at 1 Hz for temperature and locomotor activity data. Locomotor activity and body temperature data were collected continuously using Ponemah Software (DSI) and quantified using Neuroscore (DSI), and analyzed in 10-sec epochs or 1-hr bins.

Cytokine analysis

Analysis of cytokines was performed using commercially available ELISA kits for IL-6 (R&D Systems, #M6000B) and IL-1ß/IL-1F2 (R&D Systems, #MLB00C). Samples were run in duplicate according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blood was collected via cardiac puncture into EDTA coated vials (no. 367835, Becton, Dickinson and Company). Samples were centrifuged for plasma serum collection, which was then frozen at −80C for storage and thawed before ELISA analysis. Results were analyzed using a four-parameter logistic curve fit as recommended by the manufacturer.

Microglia Isolation

Microglia were isolated via a magnetic activated cells sorting (MACS) system by following the manufacturer’s “Isolation and cultivation of microglia from adult mouse or rat brain” protocol (Miltenyi Biotec). Briefly, the mice were transcardially perfused with PBS before brain extraction. Whole brains were homogenized into a single-cell suspension using the Adult Brain Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec), and enzymatically digested in the gentleMACS Octo Dissociator with heaters. Samples were then passed through a 20-gauge needle 3 times prior to passing through a 70ųm filter. Debris removal was performed as recommended by the manufacturer. Cells were labeled via anti-CD11B magnetic microbeads followed by magnetic separation using a MACS MS column (Miltenyi Biotec). Whole brain single-cell suspensions were separated into CD11B+ (microglia/macrophage) and CD11B− (non-microglia: i.e., neurons, astrocytes, endothelial cells, etc.) fractions and stored at −80C until RNA extraction.

RNA extraction and qPCR

RNA was isolated using a guanidine-isothiocyanate column-based method with the PureLink RNA Micro Kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantity and purity were analyzed using a Nanodrop 2000 Spectrophotometer. Between 200–400μg of RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA), and qPCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad) in a 20ųL reaction on a MyiQ Single Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (BioRad). Primers used were specific for KOR (Oprk1; 5’-GAATCCGACAGTAATGGCAGTG-3’and 5’-GACAGCGGTGATGATAACAGG-3’ ) TMEM119 (Tmem119; 5’-CCTACTCTGTGTCACTCCCG-3’ and 5’-CACGTACTGCCGGAAGAAATC-3’), IL-1ß; (Il1b; 5’-GCAACTGTTCCTGAACTCAACT-3’ and 5’-ATCTTTTGGGGTCCGTCAACT-3’, TNFα (Tnf; 5’-CCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT-3’ and 5’-GCTACGACGTGGGCTACAG-3’), and IL-6 (Il6; 5’-TAGTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCC-3’ and 5’-TTGGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTC-3’) and with exception of KOR were designed by the Harvard PrimerBank (Wang et al., 2012). For each sample the gene ITM2B was used as a reference (Itm2b; 5’-AGACCTACAAACTGCAGCGCC-3’ and 5’-AAAGGGGCAGGGTATGCTGTGG-3’) to calculate relative gene expression using the 2^(−delta delta CT) method.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described (Li et al., 2018) (Missig et al., 2020). Brains were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, equilibrated to 30% sucrose, and then cryosectioned (30μm). Sections containing the NaC were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin, and then incubated with 1:1000 rabbit anti-IBA-1 antibody (Code no. 019–19741, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) and 1:2000 rat anti-CD68 [FA-11] antibody (Code no. ab53444, Abcam PLC) overnight at 4°C. Following rinses, sections were incubated in 1:400 AlexaFluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit (Code no. A-21206, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 555 goat anti-rat (Code no. A-21434, Thermo Fisher Scientific) antibodies for 2 hours, rinsed, and then mounted on slides. Images were obtained with a 20X objective using a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP8, Leica, Wetzler, Germany) of the identical portion of the NaC. All images were acquired under identical settings and parameters, and then exported to NIH ImageJ for analysis. Colocalization of IBA-1 and CD68 was performed and analyzed by a blinded scorer in ImageJ. Microglia morphology was analyzed using the Sholl Analysis tool in FIJI, as described (Li et al., 2018; Missig et al., 2020).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA (Preteatment × Treatment). Contrasts were made comparing saline to each treatment and corrected using Sidak’s correction for multiple comparisons (m.c.). T-tests were used to compare two groups. To examine data from Sholl analyses, two-way ANOVAs (Treatment × Distance) with repeated measures were performed. Outliers were identified using Grubbs test and removed from analyses. To examine the normality of residuals the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus (K2) test was used. In cases of non-normality, the non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used, and multiple comparisons were adjusted with the Holm-Sidak method. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9.1.2. Results were considered statistically significant at P≤0.05.

RESULTS

KOR inhibition enhances peripheral cytokine responses to LPS

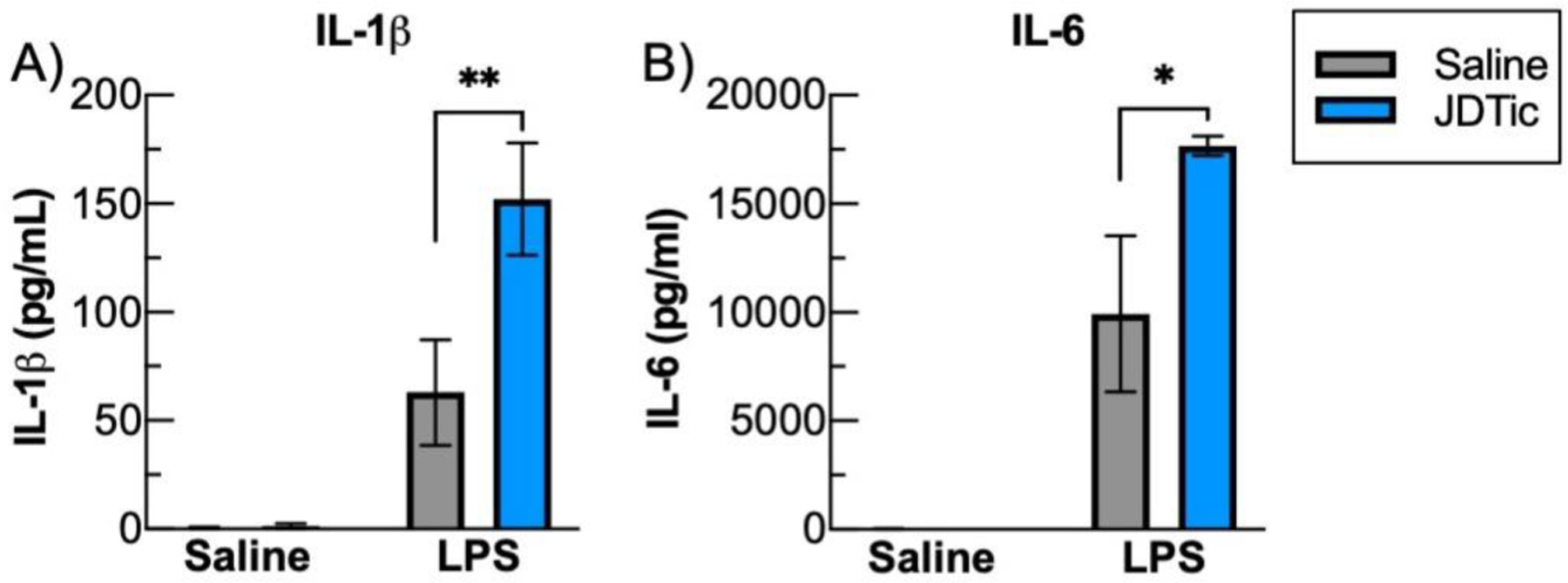

The experimental design used throughout these studies yielded four treatment conditions: Saline-Saline (SS), Saline-LPS (SL), JDTic-Saline (JS), and JDTic-LPS (JL). In the studies focusing on gene expression endpoints, cardiac blood was collected three hours after LPS administration for analysis via ELISA analysis of IL-1ß and IL-6. This time point corresponds to near-peak production of cytokines following LPS administration. As expected, LPS induced significant peripheral (plasma) elevations of both IL-1ß (main effect saline vs. LPS, F(1,20)=35.90, P<0.01) (Fig. 2A) and IL-6 (Saline vs. LPS, F(1,20)=57.53, P<0.01) (Fig. 2B). At baseline, pretreatment with JDTic did not alter levels of either IL-1ß (SS: 0.56±0.4 vs. JS: 1.34±1.2 pg/mL, m.c. P>0.05) or IL-6 (SS: 28.12±13.4 vs. JS: 10.33±4.4 pg/mL, m.c. p P>0.05). However, JDTic pretreatment dramatically enhanced the LPS-induced peripheral cytokine response, approximately doubling the levels of IL-1ß (LPS × JDTic: F(1,20)=6.19, p < 0.05, SL: 62.97±24.5 vs. JL: 152.10±25.8 pg/mL, m.c. P<0.01) and IL-6 (LPS × JDTic: F(1,20)=4.56, P<0.05, SL: 9926.59±3605 vs. JL: 17670.44±453.1 pg/mL, m.c. P<0.01). These findings indicate that while KOR antagonism has no effects on peripheral cytokine responses on its own, it enhances the proinflammatory cytokine responses that occur in response to an immune challenge.

Fig. 2. JDTic potentiates peripheral proinflammatory cytokine responses to LPS.

Three hours following LPS or saline plasma was collected, and cytokine responses were measured with ELISAs. A) IL-1ß was almost was at almost undetectable in control, saline treated mice and this was unaltered by JDTic. There was an elevation of IL-1ß following LPS that was significantly amplified with JDTic pretreatment. B) Similarly, there were low levels of IL-6 in saline treated animals and this was unaltered by JDTic. LPS substantially increased IL-6 a response that was further significantly potentiated by JDTic. n = 6 per group. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01, Mean ± SEM.

KOR inhibition amplifies LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression in microglia

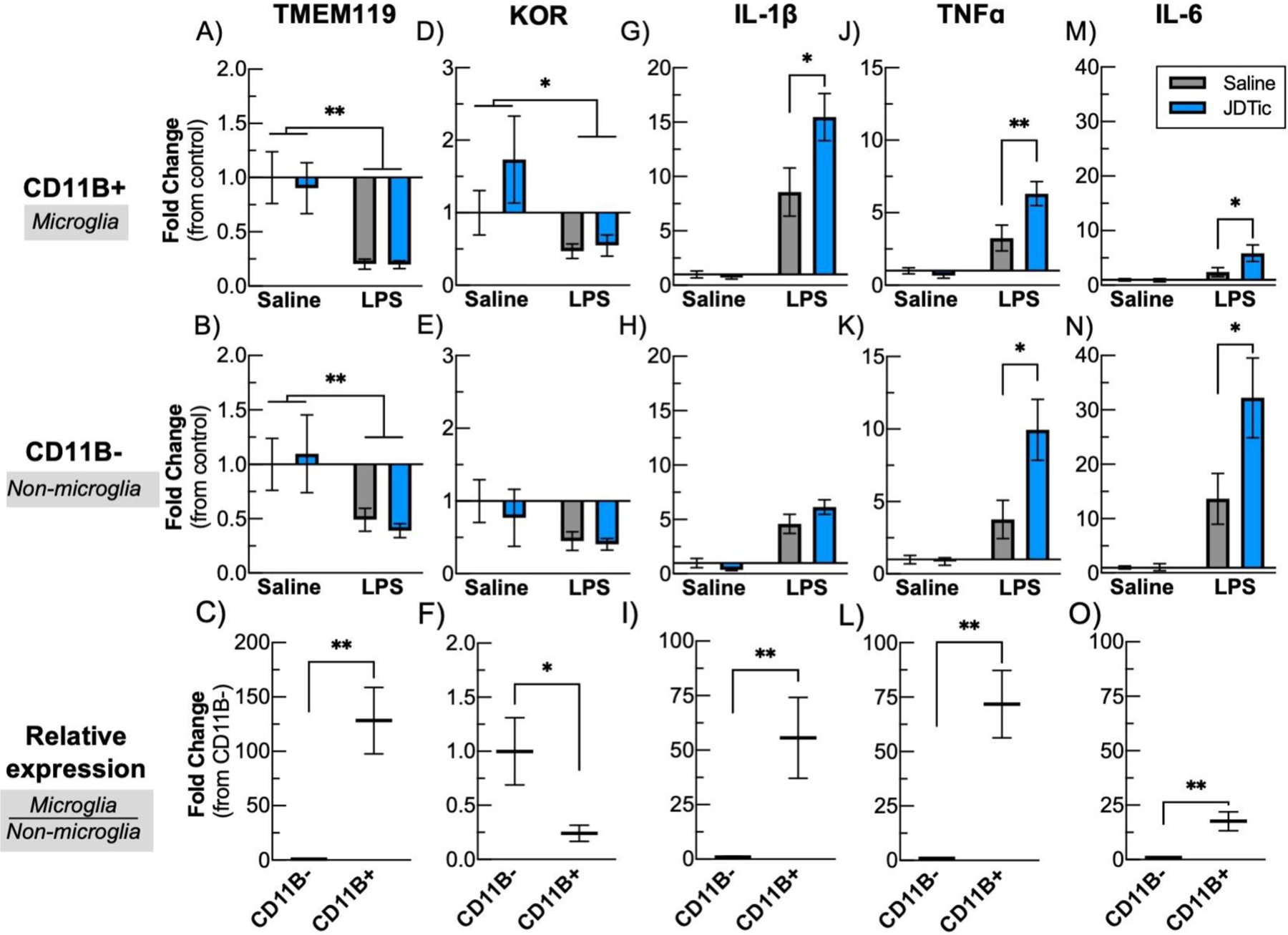

RT-qPCR was used to quantify gene expression from whole brain single-cell suspensions separated into CD11B+ (microglia/macrophage) and CD11B− (non-microglia) fractions. Analysis of TMEM119 (Fig. 3A–C), a marker highly enriched in microglia, indicated substantially higher expression in the CD11B+ fraction compared to CD11B− fraction (Figure 3C, 128.3±30.6-fold enrichment, t10=4.16, P<0.01), confirming successful separation of fractions into microglia and non-microglia cells. LPS decreased expression of TMEM119 in both CD11B+ (Fig. 3A, LPS: F(1,23)=24.5, P<0.01) and in the CD11B− fraction (Fig. 3B, LPS: F(1,23)=9.3, P<0.01), consistent with previous findings (Bennett et al. 2016). JDTic pretreatment did not alter the downregulation of TMEM119. LPS produced a significant downregulation of KOR (encoded by Oprk1) in the microglia fraction (Fig. 3D, LPS: F(1,23)=7.44, P<0.05), but this effect did not reach statistical significance in the CD11B− fraction (Fig. 3E). This downregulation was not altered by JDTic pretreatment. Expression of KOR was found in the microglia fraction at ~25% of the CD11B− fraction (0.24±0.07-fold enrichment, t10=2.37, P<0.05) (Fig. 3F). These results suggest that KOR is expressed on microglia—albeit at relatively low levels when compared to neuron-containing fractions—and that microglia KOR expression is functionally regulated in response to an inflammatory stimulus. To determine if KOR antagonism can directly alter microglia inflammatory cytokine responses, we examined expression of IL-1ß, TNFα, and IL-6 in the different cell fractions (Fig. 3G–O). As expected, LPS induced a significant upregulation of all of these cytokines for both the CD11B+ and CD11B− fractions (Fig. 3G,H,J,K,M,N main effect of LPS, P’s<0.01). On its own, JDTic did not alter levels of any of these cytokines in either fraction (m.c. SS vs. JS, P’s>0.05). However, JDTic enhanced LPS-induced cytokine expression in the microglia fraction, producing increases in IL-1ß (Fig. 3G, m.c. SL: 8.57±2.2 vs. JL: 15.5±2.2-fold change, P<0.05) and TNFα (Fig. 3J, m.c. SL: 3.26±0.9 vs. JL: 6.3±0.8-fold change, P<0.01), as well as an increase in IL-6 (Fig. 3M, m.c. SL: 2.41±0.8 vs. JL: 5.86±1.5-fold change, P<0.05). JDTic similarly enhanced LPS-induced cytokine expression in the CD11B− fraction with significant increases in TNFα, Fig. 3K, m.c. SL: 3.77±1.3 vs. JL: 9.95±2.1-fold change, P<0.05) and IL-6 (Fig. 3N, m.c. SL: 13.7±4.7 vs. JL: 32.2±7.3-fold change, P<0.05). In all cases, cytokine expression was considerably more abundant in the microglia fraction (IL-1ß: Fig. 3I, 55.7±18.6 fold enrichment, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, P<0.01, TNFα, Fig. 3L, 71.8±15.5 fold enrichment, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, P<0.01, IL-6: Fig. 3O, 17.61±4.3 fold enrichment, t10=3.85, P<0.01). These results suggest that KOR antagonism potentiates LPS-induced cytokine expression predominantly through actions on microglia.

Fig. 3: JDTic potentiates microglia proinflammatory cytokine expression in response to LPS.

Three hours following LPS mice were transcardially perfused with PBS and whole brains were enzymatically dissociated into single-cell suspensions using an GentleMACs. Using anti-CD11B microbeads using magnetic activated cell sorting, dividing samples into two fractions a highly enriched microglia fraction (CD11B+, top row), and a non-microglia fraction (CD11B−, middle row). RNA was isolated and qPCR was performed for proinflammatory cytokines, as well as the microglia marker TMEM119 and KOR. To compare the relative amount of transcript in each fraction (i.e. degree of microglia expression compared to other brain cells), the control, saline treated fractions for each transcript were directly compared (bottom row). n = 5–9 per group. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01, Mean ± SEM.

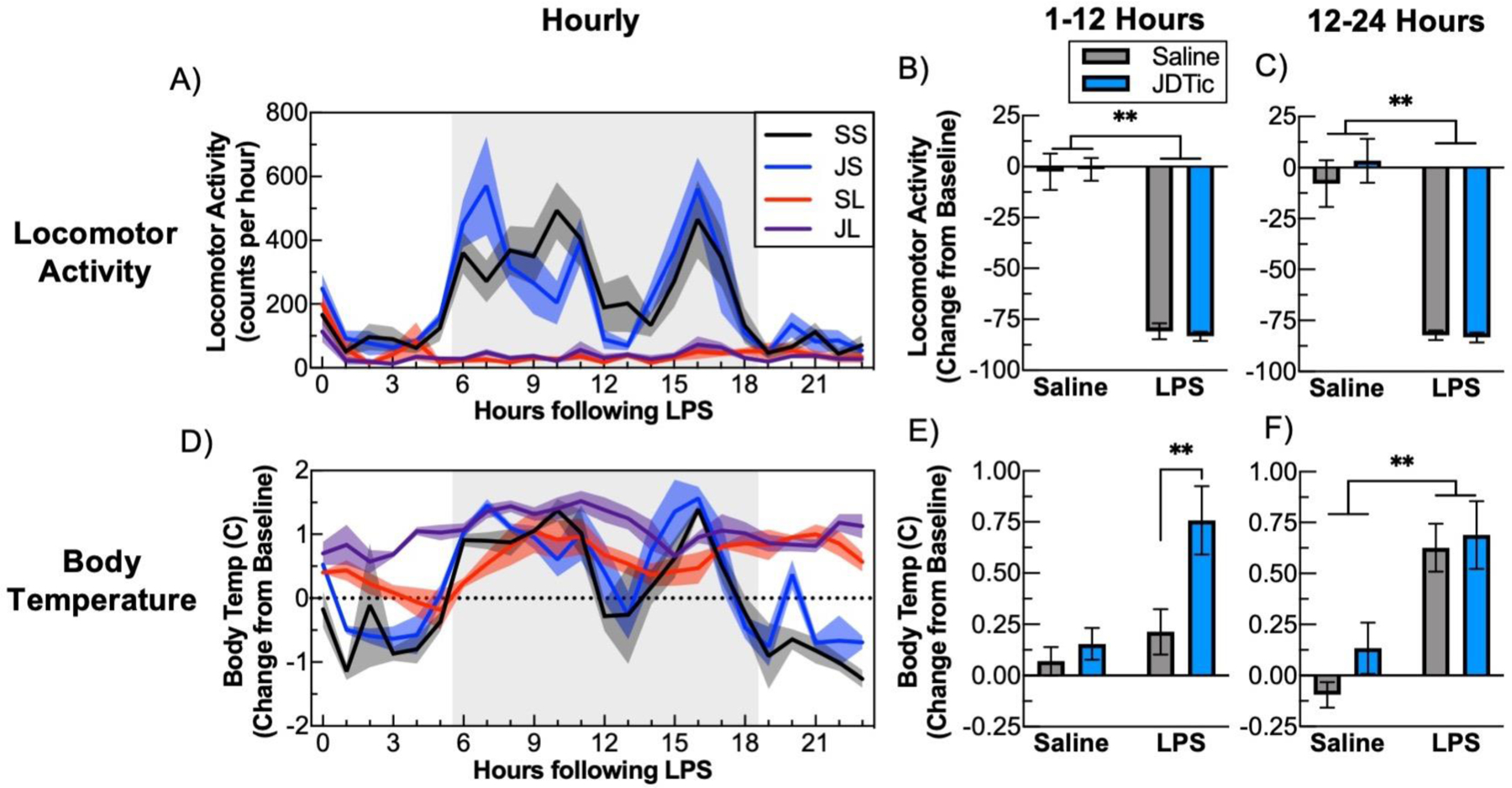

KOR inhibition enhances LPS-induced hyperthermia

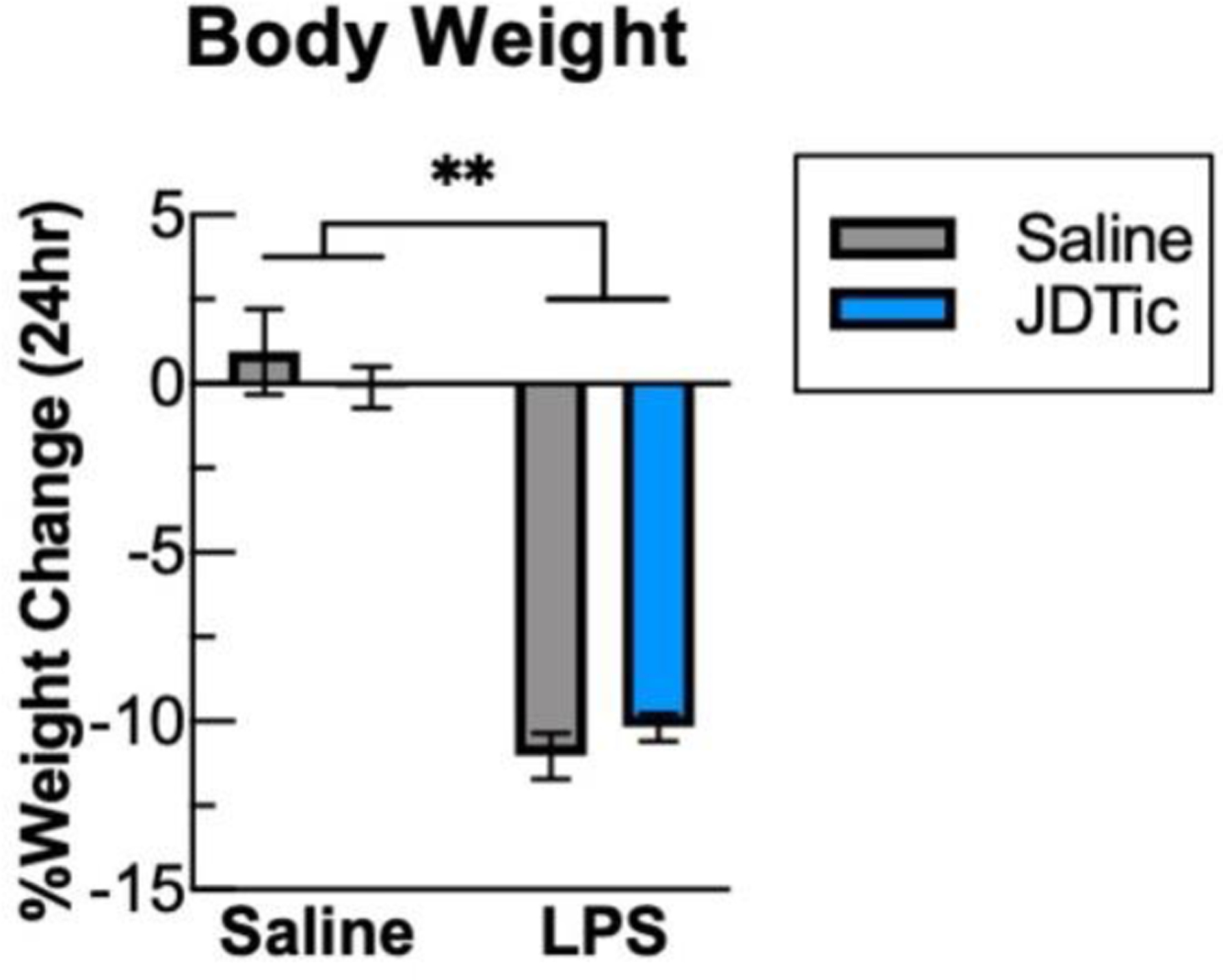

During infection, many organisms mount a stereotyped and adaptive series of behavioral and physiological responses including fatigue, fever, and anorexia collectively termed as “sickness behavior” (Dantzer and Kelley, 2007). In studies parallel to those focused on gene expression, we examined physiological endpoints in mice implanted with wireless telemetry devices that enable continuous measurement of locomotor activity and body temperature. As expected, LPS produced a significant loss of body weight (~10%) 24 hours following administration (Fig. 4, LPS: SS: 0.95±1.3 vs. SL: −11.0±0.7, and JS:−0.11±0.62 vs. JL:−10.2±0.42, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, P’s<0.01). JDTic had no effect on weight loss in vehicle or LPS-treated mice. LPS also produced suppression of locomotor activity throughout the 24-hour recording period (Fig. 5A), which included loss of the diurnal increases in locomotor activity normally seen during the dark phase readily apparent in SS and JS mice (Fig. 5A). Relative to baseline, LPS produced sustained ~80% reductions in locomotor activity levels during the first (Fig. 5B, LPS: F(1,22)=181.3, P<0.01) and second 12-hr recording periods (Fig. 5C, SS vs JS and SL vs. JL, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, P’s<0.01). JDTic did not have any significant effects on locomotor activity in vehicle or LPS-treated mice. LPS also produced sustained elevations in body temperature following LPS (Fig. 5D). These effects were most readily apparent when activity levels are low during the light phase, when LPS virtually eliminated the typically strong correlation between locomotor activity levels and body temperature (correlation of Activity and Temperature (R2), SS:0.62±0.05, JS: 0.70±0.04, SL:0.05±0.02, JL: 0.06±0.02, LPS: F(1,22)=271.4, P<0.01). JDTic enhanced LPS-induced increases in body temperature during the first 12-hr period (Fig 5E, LPS × JDTic: F(1,22)=4.32, P< 0.05 m.c. SL: 0.21±0.1 vs. JL: 0.76±0.2 C, P<0.05), whereas similar degrees of increases were seen in all LPS-treated mice during the second 12-hr period (Fig. 5F, LPS (F(1,22)=28.2, P< 0.01). These findings suggest that KOR antagonism can enhance LPS effects on body temperature, which can be uncoupled from effects on locomotor activity.

Fig. 4: Bodyweight loss following LPS is not altered by JDTic.

Bodyweight of mice was measured immediately before and 24 hours after LPS injection. LPS lead to a significant decrease in bodyweight an effect that was not altered by JDTic. n = 6–7 per group. ** p < 0.01 (vs. Baseline), Mean ± SEM.

Fig. 5: JDTic amplifies LPS-induced hyperthemia.

Mice were implanted with remote telemetry devices that enable continuous measurement of body temperature and locomotor activity. After a 72 hour baseline period mice were either injected with JDTic or saline and then 24 hours later with LPS. A) LPS induced an almost complete suppression of locomotor activity for 24 hours following administration and comparing locomotor activity to its 72-hour baseline shows a significant suppression by LPS during B) the first 12-hour period and C) the second 12-hour period following LPS, with no additional effects of JDTic. D) Examining body temperature change compared to average baseline temperature reveals that LPS lead to an elevation of body temperature. This is especially evident during the light phase when body temperature, when body temperature is typically lower due to the lack of locomotor activity. E) Comparing change in body temperature during the first 12-hour period shows a substantial elevation by JDTic pretreatment during this period, F) but not during the second 12-hour period. n = 7–8 per group. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 Mean ± SEM.

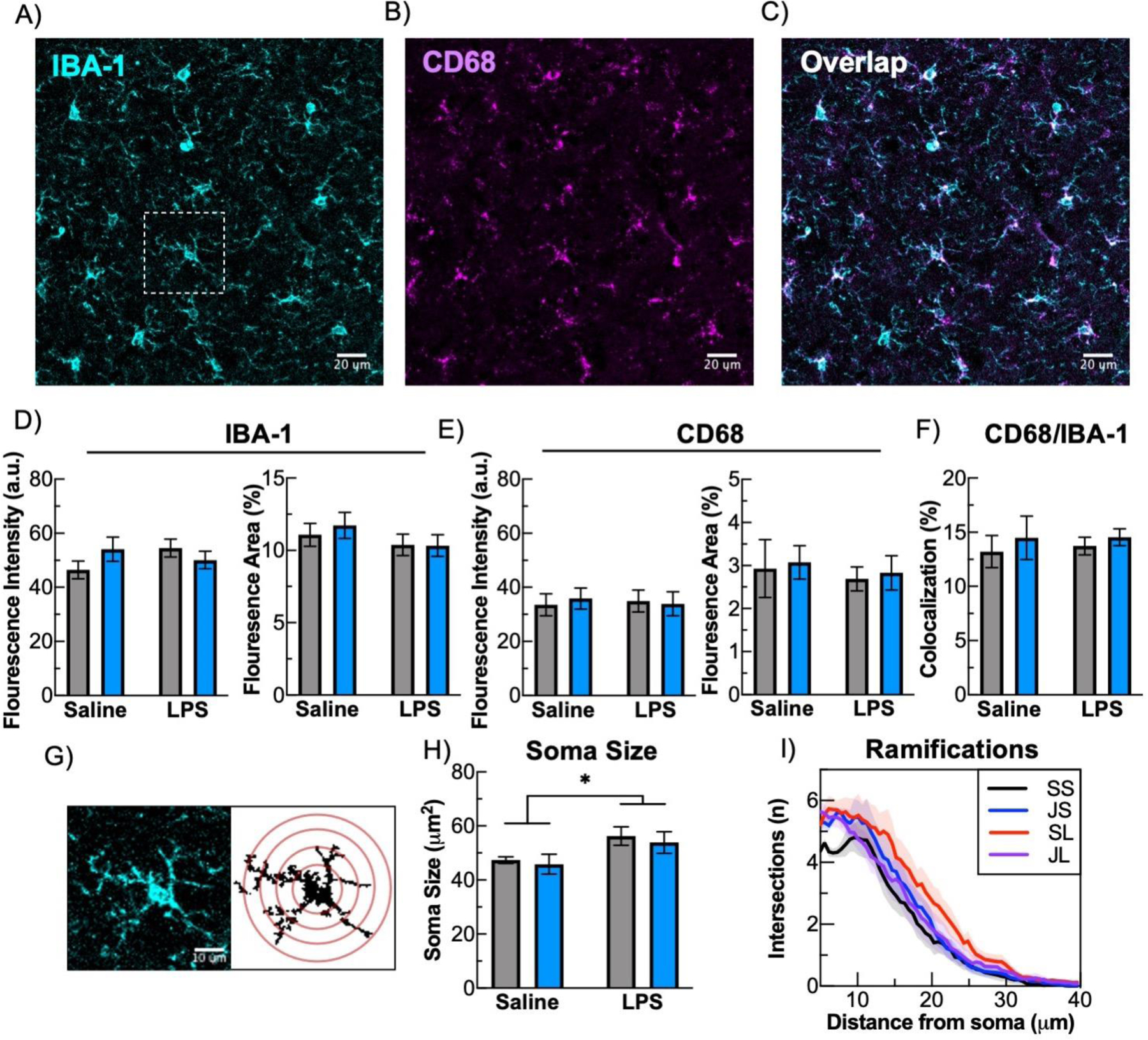

Alterations in microglia morphology following LPS and KOR inhibition

In response to immune stimulation, microglia undergo a series of stereotypical morphological modifications as part of the transition to different activational states. We have previously reported that LPS produces such changes in the amygdala, a brain area implicated in stress responsiveness (Li et al., 2018). To determine if KOR antagonism affects these modifications in the NAc—representing a potential mechanism by which it might enhance LPS effects—we performed immunohistochemistry for the microglia/macrophage marker IBA-1 and co-stained for the glycoprotein CD68, which is expressed and upregulated in microglia following immune stimulation and often used as a marker for microglia phagocytosis. LPS did not produce significant changes in IBA-1 staining intensity or area in the NAc, regardless of JDTic treatment (Fig. 6A,D). Similarly there were no significant changes in CD68 levels (Fig. 6B,E). As expected, CD68 was coexpressed with IBA-1 (Fig. 6F), and there were no differences in the extent of overlap of CD68 with IBA-1 between any of the treatment conditions (Figure 6C). Previous work has shown that, in response to a variety of inflammatory or damage associated signals, microglia can undergo a morphological transition from a highly ramified state with a small soma to an amoeboid state with decreased ramification and larger soma size (Davis et al., 2017; Tremblay et al., 2011). However, these changes are not binary; a variety of different morphologies can be observed, consistent with recent studies suggesting microglia exhibit a multitude of activational states (Masuda et al., 2020). To evaluate microglia morphological alterations, we measured soma size and the degree of ramifications with a Sholl analysis (Fig. 6G). LPS produced a significant increase in the soma size of NAc microglia (Fig. 6H, LPS: F(1,15)=6.76, P<0.05) that was not affected by JDTic. Additionally, Sholl analysis indicated that neither JDTic and LPS nor LPS led to significant alterations in microglia ramifications (Fig. 6I, P>0.05). These findings extend previous work in other brain areas (e.g., (Li et al., 2018) to show that LPS produces visible changes in microglia morphology consistent with activation, while also suggesting that the ability of KOR antagonism to enhance LPS effects are not affecting this process.

Fig. 6: Altered microglia morphology by LPS and JDTic.

To examine microglia for microglial histological alterations double-labeling immunohistochemistry for IBA-1 and CD68 from brain sections containing the NAc. A) example image of IBA-1, B) CD68, C), and the overlap between IBA-1 and CD68. There were no significant effects by LPS or JDTIC on NAc staining intensity (left) or area (right) for D) IBA-1, E) CD68, or F) the amount CD68 overlap with IBA-1. G) To evaluate morphological changes a Sholl analysis was performed on IBA-1 staining, as depicted from microglia cell that is an inset depicted in A). H) Soma size was significantly increased by LPS. I) Results of Sholl analysis with all treatment groups comparing distance from soma to number of intersections. n = 4–5 mice per group, derived from average of 3 sections per mouse, and 10 microglia per section for histology (30 total microglia per mouse) * p< 0.05 ** p < 0.01 Mean ± SEM.

DISCUSSION

Here we show that the proinflammatory effects of LPS are amplified by KOR antagonism. These effects are detectable in blood as well as in ex vivo brain tissue. Specifically, systemic administration of LPS to adult mice produces increases in the proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1ß, IL-6) in plasma. Pretreatment with the KOR-selective antagonist JDTic at a dose with anti-stress like effects on behavioral endpoints such as sleep disruption in mice (Wells et al., 2017) produced large increases in the effects of LPS on these same cytokines, without causing effects of its own. In ex vivo studies designed to explore the cellular substrates of these effects, we used MACS to separate brain tissue from mice given these treatments into fractions containing microglia or non-microglial cells on the basis of expression of the microglial marker CD11B (Bordt et al., 2020). Similar to our findings in blood, we found that LPS produces increases in proinflammatory cytokines in both the CD11B+ fraction (which includes microglia/macrophages) and the CD11B− fraction (which includes neurons, astrocytes, and endothelial cells), and that these effects are also potentiated by pretreatment with JDTic. Importantly, however, cytokine expression was considerably more abundant in the microglia fraction than in the non-neuronal fraction, providing insight on the relative contributions of these cell types in regulating the proinflammatory response. LPS also produced a significant downregulation in KOR expression in the microglial fraction, suggesting rapid and dynamic regulation of these receptors in this cell type, without effects in the non-microglia (i.e., neuronal) fraction. When considered together, these results suggest that KOR antagonism potentiates LPS-induced cytokine expression in the brain predominantly through actions on microglia.

Interactions between immune activation and KOR antagonism were also seen in some, though not all, of the other endpoints under study. Administration of LPS produces increases in core body temperature—a fever-like effect—that were enhanced by JDTic, indicating that KOR antagonism amplifies this key aspect of the immune activation response. However, LPS also caused reductions in body weight and locomotor activity, neither of which were further affected by KOR antagonism. These results were somewhat surprising, considering that we anticipated that KOR antagonism would also amplify LPS-induced reductions in body weight and locomotor activity on the basis of the findings when proinflammatory cytokines and body temperature were used as endpoints. One possible explanation for this pattern of results is that LPS alone produced maximal effects on both outcomes, such that it was not possible to observe a further potentiation of its effects under the conditions used for testing. In the case of body weight, it is also possible that KOR antagonist effects on neurons can offset their effects on microglia. For example, KOR antagonists can produce small increases in extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in the NAc (Maisonneuve et al., 1994), presumably by blocking the inhibitory actions of dynorphin at KORs expressed on the terminals of mesolimbic inputs from the ventral tegmental area (Svingos et al., 1999). Increases in brain DA function can “energize” feeding behaviors (Wise, 2006), which in this case would, if anything, tend to offset the anorectic effects of LPS. However, KOR activation has been demonstrated to regulate feeding in ways that may be inconsistent with DA regulation, indicating that there are likely diverse mechanisms underlying KORs effects on feeding (Castro and Berridge, 2014; Woolley et al., 2007). The finding that KOR antagonism influences LPS-induced effects on body temperature without affecting locomotor activity supports our previous observations that these two endpoints can be uncoupled (Wells et al., 2017). Administration of LPS also produces visible changes in the morphology of NAc microglia that are consistent with a state of heightened activation. Specifically, LPS produced increases in the soma size of microglia in the NAc, although other indicators of activation (e.g., number of ramifications) were not significantly changed. The effect of LPS on soma size was not affected by KOR antagonist pretreatment. While additional work is needed to provide insight on the cellular mechanisms by which KOR antagonism amplifies the proinflammatory effects of LPS, these data provide early evidence that it is unlikely that they involve the types of changes in glia cell morphology that are detectable by Sholl analyses.

There are numerous important caveats for these studies. It is important to emphasize that while microglia are located throughout the brain, emerging evidence suggests regional heterogeneity in morphology, function, and gene expression profiles (Tan et al., 2020). For example, mRNA encoding KORs (Oprk1) in microglia is highest within striatal regions such as the NAc, but appears absent from microglia in other areas (Dropviz.org) (Saunders et al., 2018). These observations raise the possibility that receptor expression on microglia is dynamic and exquisitely responsive to the local milieu, such as the distribution of neuropeptides (e.g., dynorphin). We focused on the NAc because it has been implicated in the antidepressant/anxiolytic-like effects of KOR antagonists (Carlezon and Krystal, 2016), but it is possible that the prodepressive effects of LPS may be regulated in other KOR-expressing regions (Tejeda et al., 2017; Van’t Veer et al., 2016). As such, morphology studies focusing on these interactions in other brain areas may yield differing patterns of results. Future studies are needed to understand if there is regional heterogeneity of microglia responses to KOR inhibition. Additionally, it is unclear whether microglia KORs are driving the potentiation of inflammatory responses seen with KOR inhibition, or if microglia are responding to higher levels of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines released by other immune cells. Cell type-specific deletion of KORs would enable a more thorough characterization of the role of microglia KORs in this potentiated response. Another caveat is that these early studies were conducted only in male mice. Previous work indicates that early postnatal treatment with LPS can produce sex differences in behavior and in the relative expression levels of gene encoding pro- and anti-inflammatory factors (Carlezon et al., 2019). In addition, work in rats suggests that there are sex differences in KOR function, with males being more sensitive to KOR agonists than females (Conway et al., 2019; Russell et al., 2014). The present studies may serve as a basis for more comprehensive studies of interactions between inflammation and KORs to explore mechanism and potential sex differences.

The current work has potentially important implications for the development of KOR antagonists as therapeutics for treating neuropsychiatric conditions. Inflammation is increasingly implicated in depressive and anxiety disorders (Haroon et al., 2017; Menard et al., 2017). Our previous work indicates that even a single exposure to LPS can produce persistent signs of anhedonia and other depressive and anxiety-like effects (Carlezon et al., 2019; Li et al., 2018), and the present data suggest that these effects could be amplified by KOR antagonism primarily by microglia-mediated increases in proinflammatory cytokines. Considering that activation of KORs on microglia normally serves to suppress proinflammatory signaling (Chao et al., 1996), these new findings raise the possibility that KOR antagonist effects on microglia (i.e., disinhibition of cytokine release) may detract from simultaneous effects on neurons (e.g., disinhibition of mesolimbic DA system function) that contribute to the therapeutic potential of this class of drugs (Carlezon and Krystal, 2016). The present data set the stage for future studies designed to examine if mitigating KOR antagonism effects on microglia and/or enhancing effects on neurons can enhance the efficacy or safety of KOR antagonists.

Highlights.

Inflammatory processes are implicated in psychiatric illnesses including depression.

Microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, express kappa-opioid receptors (KORs).

KOR antagonists are being developed for the treatment of depression.

We show that KOR antagonists enhance microglia-mediated proinflammatory responses.

KOR antagonist actions on microglia may detract from therapeutic actions on neurons.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURES

This research was supported by NIH grant R01MH063266 and gifts from the Robert and Donna Landreth Family Fund, the Eric Dorris Memorial Fellowship, and the Teamsters Local 25 Autism Fund. In the last 2 years, WC has received compensation as a consultant from Psy Therapeutics. None of the other authors have disclosures relevant to this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Bordt EA, Block CL, Petrozziello T, Sadri-Vakili G, Smith CJ, Edlow AG and Bilbo SD (2020) Isolation of Microglia from Mouse or Human Tissue. STAR Protoc 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA Jr., Kim W, Missig G, Finger BC, Landino SM, Alexander AJ, Mokler EL, Robbins JO, Li Y, Bolshakov VY, McDougle CJ and Kim KS (2019) Maternal and early postnatal immune activation produce sex-specific effects on autism-like behaviors and neuroimmune function in mice. Sci Rep 9:16928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA Jr. and Krystal AD (2016) Kappa-Opioid Antagonists for Psychiatric Disorders: From Bench to Clinical Trials. Depress Anxiety 33:895–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA and Missig G (2021) Super glue: emerging roles for non-neuronal brain cells in mental health. Neuropsychopharmacology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll FI and Carlezon WA Jr. (2013) Development of kappa opioid receptor antagonists. J Med Chem 56:2178–2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro DC and Berridge KC (2014) Opioid hedonic hotspot in nucleus accumbens shell: mu, delta, and kappa maps for enhancement of sweetness “liking” and “wanting”. J Neurosci 34:4239–4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CC, Gekker G, Hu S, Sheng WS, Shark KB, Bu DF, Archer S, Bidlack JM and Peterson PK (1996) kappa opioid receptors in human microglia downregulate human immunodeficiency virus 1 expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:8051–8056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavkin C, James IF and Goldstein A (1982) Dynorphin is a specific endogenous ligand of the kappa opioid receptor. Science 215:413–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway SM, Puttick D, Russell S, Potter D, Roitman MF and Chartoff EH (2019) Females are less sensitive than males to the motivational- and dopamine-suppressing effects of kappa opioid receptor activation. Neuropharmacology 146:231–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R and Kelley KW (2007) Twenty years of research on cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain Behav Immun 21:153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BM, Salinas-Navarro M, Cordeiro MF, Moons L and De Groef L (2017) Characterizing microglia activation: a spatial statistics approach to maximize information extraction. Sci Rep 7:1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Wu CY, Burton FH, Loh HH and Wei LN (2014) beta-arrestin protects neurons by mediating endogenous opioid arrest of inflammatory microglia. Cell Death Differ 21:397–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon E, Miller AH and Sanacora G (2017) Inflammation, Glutamate, and Glia: A Trio of Trouble in Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 42:193–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodes GE, Pfau ML, Leboeuf M, Golden SA, Christoffel DJ, Bregman D, Rebusi N, Heshmati M, Aleyasin H, Warren BL, Lebonte B, Horn S, Lapidus KA, Stelzhammer V, Wong EH, Bahn S, Krishnan V, Bolanos-Guzman CA, Murrough JW, Merad M and Russo SJ (2014) Individual differences in the peripheral immune system promote resilience versus susceptibility to social stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:16136–16141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoll AT and Carlezon WA Jr. (2010) Dynorphin, stress, and depression. Brain Res 1314:56–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal AD, Pizzagalli DA, Smoski M, Mathew SJ, Nurnberger J Jr., Lisanby SH, Iosifescu D, Murrough JW, Yang H, Weiner RD, Calabrese JR, Sanacora G, Hermes G, Keefe RSE, Song A, Goodman W, Szabo ST, Whitton AE, Gao K and Potter WZ (2020) A randomized proof-of-mechanism trial applying the ‘fast-fail’ approach to evaluating kappa-opioid antagonism as a treatment for anhedonia. Nat Med 26:760–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey DF, Stein MB, Wendt FR, Pathak GA, Zhou H, Aslan M, Quaden R, Harrington KM, Nunez YZ, Overstreet C, Radhakrishnan K, Sanacora G, McIntosh AM, Shi J, Shringarpure SS, andMe Research T, Million Veteran P, Concato J, Polimanti R and Gelernter J (2021) Bi-ancestral depression GWAS in the Million Veteran Program and meta-analysis in >1.2 million individuals highlight new therapeutic directions. Nat Neurosci 24:954–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Missig G, Finger BC, Landino SM, Alexander AJ, Mokler EL, Robbins JO, Manasian Y, Kim W, Kim KS, McDougle CJ, Carlezon WA Jr. and Bolshakov VY (2018) Maternal and Early Postnatal Immune Activation Produce Dissociable Effects on Neurotransmission in mPFC-Amygdala Circuits. J Neurosci 38:3358–3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrich FE (2009) Major depression during interferon-alpha treatment: vulnerability and prevention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 11:417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve IM, Archer S and Glick SD (1994) U50,488, a kappa opioid receptor agonist, attenuates cocaine-induced increases in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Neurosci Lett 181:57–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T, Sankowski R, Staszewski O and Prinz M (2020) Microglia Heterogeneity in the Single-Cell Era. Cell Rep 30:1271–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard C, Pfau ML, Hodes GE and Russo SJ (2017) Immune and Neuroendocrine Mechanisms of Stress Vulnerability and Resilience. Neuropsychopharmacology 42:62–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AH, Maletic V and Raison CL (2009) Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry 65:732–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missig G, Robbins JO, Mokler EL, McCullough KM, Bilbo SD, McDougle CJ and Carlezon WA Jr. (2020) Sex-dependent neurobiological features of prenatal immune activation via TLR7. Mol Psychiatry 25:2330–2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschamp JW and Carlezon WA Jr. (2013) Roles of nucleus accumbens CREB and dynorphin in dysregulation of motivation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3:a012005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muschamp JW, Nemeth CL, Robison AJ, Nestler EJ and Carlezon WA Jr. (2012) DeltaFosB enhances the rewarding effects of cocaine while reducing the pro-depressive effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist U50488. Biol Psychiatry 71:44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Smoski M, Ang YS, Whitton AE, Sanacora G, Mathew SJ, Nurnberger J Jr., Lisanby SH, Iosifescu DV, Murrough JW, Yang H, Weiner RD, Calabrese JR, Goodman W, Potter WZ and Krystal AD (2020) Selective kappa-opioid antagonism ameliorates anhedonic behavior: evidence from the Fast-fail Trial in Mood and Anxiety Spectrum Disorders (FAST-MAS). Neuropsychopharmacology 45:1656–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz M, Jung S and Priller J (2019) Microglia Biology: One Century of Evolving Concepts. Cell 179:292–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell SE, Rachlin AB, Smith KL, Muschamp J, Berry L, Zhao Z and Chartoff EH (2014) Sex differences in sensitivity to the depressive-like effects of the kappa opioid receptor agonist U-50488 in rats. Biol Psychiatry 76:213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders A, Macosko EZ, Wysoker A, Goldman M, Krienen FM, de Rivera H, Bien E, Baum M, Bortolin L, Wang S, Goeva A, Nemesh J, Kamitaki N, Brumbaugh S, Kulp D and McCarroll SA (2018) Molecular Diversity and Specializations among the Cells of the Adult Mouse Brain. Cell 174:1015–1030 e1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Moreira L, Campos-Salinas J, Caro M and Gonzalez-Rey E (2011) Neuropeptides as pleiotropic modulators of the immune response. Neuroendocrinology 94:89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Colago EE and Pickel VM (1999) Cellular sites for dynorphin activation of kappa-opioid receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens shell. J Neurosci 19:1804–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan YL, Yuan Y and Tian L (2020) Microglial regional heterogeneity and its role in the brain. Mol Psychiatry 25:351–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tejeda HA, Wu J, Kornspun AR, Pignatelli M, Kashtelyan V, Krashes MJ, Lowell BB, Carlezon WA Jr. and Bonci A (2017) Pathway- and Cell-Specific Kappa-Opioid Receptor Modulation of Excitation-Inhibition Balance Differentially Gates D1 and D2 Accumbens Neuron Activity. Neuron 93:147–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay ME, Stevens B, Sierra A, Wake H, Bessis A and Nimmerjahn A (2011) The role of microglia in the healthy brain. J Neurosci 31:16064–16069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van’t Veer A and Carlezon WA Jr. (2013) Role of kappa-opioid receptors in stress and anxiety-related behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 229:435–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van’t Veer A, Smith KL, Cohen BM, Carlezon WA Jr. and Bechtholt AJ (2016) Kappa-opioid receptors differentially regulate low and high levels of ethanol intake in female mice. Brain Behav 6:e00523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Spandidos A, Wang H and Seed B (2012) PrimerBank: a PCR primer database for quantitative gene expression analysis, 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res 40:D1144–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells AM, Ridener E, Bourbonais CA, Kim W, Pantazopoulos H, Carroll FI, Kim KS, Cohen BM and Carlezon WA Jr. (2017) Effects of Chronic Social Defeat Stress on Sleep and Circadian Rhythms Are Mitigated by Kappa-Opioid Receptor Antagonism. J Neurosci 37:7656–7668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA (2006) Role of brain dopamine in food reward and reinforcement. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 361:1149–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg GM, Greene J, Vertes PE, Drevets WC and Bullmore ET (2020) Major Depressive Disorder Is Associated With Differential Expression of Innate Immune and Neutrophil-Related Gene Networks in Peripheral Blood: A Quantitative Review of Whole-Genome Transcriptional Data From Case-Control Studies. Biol Psychiatry 88:625–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley JD, Lee BS, Kim B and Fields HL (2007) Opposing effects of intra-nucleus accumbens mu and kappa opioid agonists on sensory specific satiety. Neuroscience 146:1445–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]