Abstract

Postpartum depression (PPD) is the most frequent psychiatric complication during the postnatal period. According to existing evidence, an association exists between the development of PPD and the maintenance of breastfeeding. A brief motivational intervention (bMI), based on the motivational interview, seems effective in promoting breastfeeding. The objective of this study was to analyse the impact of a bMI aiming to promote breastfeeding on the development of PPD and explore the mediating/moderating roles of breastfeeding and breastfeeding self-efficacy in the effect of the intervention on developing PPD. Eighty-eight women who gave birth by vaginal delivery and started breastfeeding during the immediate postpartum period were randomly assigned to the intervention group (bMI) or control group (breastfeeding education). Randomisation by minimisation was carried out. The breastfeeding duration was longer in the intervention group (11.06 (± 2.94) weeks vs 9.02 (± 4.44), p = 0.013). The bMI was associated with a lower score on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, with a regression β coefficient of − 2.12 (95% CI − 3.82; − 0.41). A part of this effect was mediated by the effect of the intervention on the duration of breastfeeding (mediation/moderation index β = − 0.57 (95% CI − 1.30; − 0.04)). These findings suggest that a bMI aiming to promote breastfeeding has a positive impact preventing PPD mainly due to its effectiveness in increasing the duration of breastfeeding.

Subject terms: Public health, Health care, Lifestyle modification

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is the most frequent psychiatric complication during the postnatal period1, with a reported prevalence ranging between 10 and 15% and even up to 30% depending on the diagnostic criteria used2–5. PPD is characterised by a persistent state of mind in mothers accompanied by feelings of sadness, uselessness, or hopelessness and the inability to face and feel joy for the new baby6,7. Other symptoms, such as agitation, anxiety, loss of appetite, lack of concentration, fatigue, or suicidal ideation, may appear6,8. PPD is associated with alterations in the behaviour of the mother regarding her baby that have a negative impact on the emotional, cognitive, and motor development of the child4. In addition, women who suffer from PPD have an increased risk of developing major depression in the future9.

The development of this pathology during the postpartum period seems to be related to the hormonal alterations that occur during this period4. Other factors that increase the probability of its development have been identified, including (i) a history of psychiatric disorders (history of depression, anxiety or depression in pregnancy or postpartum depression)7,10; (ii) stressful life events (including stressors related to childcare), problems in the marital relationship, and lack of support11,12; (iii) sociodemographic characteristics (low educational or socioeconomic level, absence of a partner, or unemployment)7,13; and (iv) some clinical circumstances, such as caesarean delivery, primiparity, and complications during pregnancy13,14.

However, evidence suggests that a relationship exists between breastfeeding (BF) and PPD. Exclusive BF is the ideal food for newborns up to the sixth month of life, and the maintenance of BF along with other foods is recommended for at least 1 or 2 years15,16. Optimal BF is associated with benefits to maternal and child health17–22, and it has been estimated that the adequate practice of BF is associated with the prevention of 820,000 deaths per year of children aged under 5 years and 19,500 deaths of women related to breast cancer23. Therefore, achieving the goal of at least 50% of children aged under 6 months being exclusively breastfed is one of the objectives set by the WHO in its “Global Nutrition Targets 2025”24. Regarding the association between BF and PPD, while some authors point out that women with PPD have a shorter duration of BF25–27. Other authors note that women who breastfeed are less likely to develop PPD and associate a longer duration of BF with better mental wellbeing among women during the postpartum period and a decrease in the negative feelings that characterise PPD11,21,28. Furthermore, several studies have found that mothers with a high level of breastfeeding self-efficacy (BSE) have lower scores on PPD rating scales29–32.

Background

Various approaches to PPD prevention have been implemented as follows: (i) interpersonal counselling interventions 33,34, (ii) cognitive-behavioural therapies 35,36, (iii) therapies to modify health habits 37–39, and (iv) postpartum support interventions 2,40–44. A meta-analysis performed for the US Preventive Services Task Force45 found that cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal therapy are effective interventions for preventing PPD.

Among interpersonal therapies, the brief motivational intervention (bMI) is based on the motivational interview, which could be defined as a collaborative communication style designed to increase personal motivation to achieve one's goals while exploring the individual's ambivalences to change within an atmosphere of acceptance46. This type of intervention has already been shown to be effective in increasing the duration of BF and the level of BSE47–53. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, only two studies54,55 analysed the use of this type of therapy to improve help-seeking when women experience negative feelings associated with PPD.

The evidence suggests that a complex relationship exists among the duration of BF, the presence of PPD11,21,25,27, and the level of BSE29,31. Therefore, analysing whether an intervention that acts on BF and BSE also has an impact on PPD and determining the causal relationships and the magnitude of the effect among these factors are relevant and pertinent.

The study

Aims

This study aimed to analyse the impact of a bMI aiming to promote BF on the development of PPD and explore the mediating/moderating role of BF and BSE in the effect of the intervention on the development of PPD.

For the aims described above, we hypothesise the following:

Women who receive a bMI would have fewer depressive symptoms in the third month postpartum.

The effect of the bMI on the BF rates acts as a mediator of the relationship between the bMI and the presence of depressive symptoms postpartum.

The increase in maternal BSE targeted by the bMI acts as a moderator of the relationship between the bMI and the presence of depressive symptoms postpartum.

Design

A randomised, controlled, multicentre, parallel-group clinical trial was carried out.

Participants

The study was carried out in two public hospitals in southwestern Spain between February 2018 and January 2019.

The participants in this study were women who gave birth via vaginal delivery to healthy newborns and who started BF in the hour after delivery regardless of the number of pregnancies or previous deliveries. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) mother-newborn separation after delivery due to admission to the neonatal care unit; (b) psychiatric disorder or cognitive damage previously diagnosed in the woman (including the diagnosis of depression before or during pregnancy); (c) impossibility of follow-up with the newborn-mother dyad; (d) women without adequate prenatal care that included prepartum depression screening; and (e) communication barriers.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was established based on the effects obtained in similar studies on BF and EBF48–50. With a common alpha risk of 0.05, a beta risk of 0.20, and an estimated loss to follow-up of 10%, we calculated that we needed to include 44 participants in each group.

Procedures

During the immediate postpartum period (first 2 h after delivery), participation in the study was requested from all women who met the inclusion criteria and did not present any of the exclusion criteria based on the clinical history recorded and completed at admission to the hospital until the sample size was reached.

As described in the published study protocol56, after recruitment and signing of informed consent, an initial interview was carried out to collect the baseline variables of the participating women. Subsequently, through a randomisation process by minimisation57, the women were blindly assigned to one of the two study groups. The midwife responsible for the recruitment and collection of the baseline data was unaware of the randomisation sequence until the investigator in charge of the randomisation reported the result. This researcher obtained the data required for the anonymised randomisation. The collection of the follow‐up data was carried out by another researcher blinded to the intervention/control group status of the participants.

After the randomisation process, the women assigned to the intervention group received a single bMI as follows: a semi-structured interview based on open questions, reflections, and summaries according to the principles of motivational interviewing46. The content of the bMI included the exploration of motivations, ambivalences, barriers, and facilitators of the development of BF and the woman's BSE (Table 1).

Table 1.

Content of the training sessions.

| Brief motivational intervention | Breastfeeding educational session |

|---|---|

| ✓ Introduction: the objectives of the intervention were explained, and trust was promoted through an empathetic therapeutic approach |

✓ A good start to breastfeeding Skin-to-skin contact and baby-led breastfeeding attachment |

| ✓ Promote self-efficacy: the woman's confidence in her ability to breastfeed was promoted by identifying the mother's goals, available resources and possible difficulties, promoting learning and reinforcing skills to address BF |

✓ Keys to success in breastfeeding in the first days Keep baby in the room with the mother Responsive feeding Early signs of infant hunger Checking the breastfeeding latch Information regarding stimulating and expressing milk manually or with a breast pump Basic feeding routines and times Avoid teats, dummies and complementary feeds |

| ✓ Motivation: the woman’s motivation to maintain breastfeeding was explored |

✓ Information for the return home Follow-up of BF by healthcare personnel Useful reference web pages |

| ✓ Exploration of ambivalence: possible ambivalence was addressed with nonconfrontational responses to the mother's descriptions of any resistance to breastfeeding, her motivation for breastfeeding, and her perceived self‐efficacy | |

| ✓ Final summary: a verbal review of the most important issues addressed and an opportunity to answer any questions that the mother may have had. Emphasising the advantages of their motivation and ability to find resources and facilitators in their environment to promote their self-efficacy |

The women in the control group received a single educational session that addressed the correct guidelines for achieving successful BF. The session consisted of providing information regarding BF and tips for success (Table 1) using the information leaflet distributed and approved by the Spanish Association of Paediatrics “Congratulations on Your New Motherhood” as a guide58.

Both sessions were carried out during the immediate postpartum period in individual sessions by the same midwife with extensive experience in BF who was specifically trained in motivational interviewing by expert psychologists. The duration of the two types of sessions ranged between 20 and 30 min. The women in both groups were given written information regarding BF through the brochure “Congratulations on Your New Motherhood!”59 and information regarding BF support groups in their area.

The women in both study groups received booster calls at the 1st postpartum month, lasting no longer than 15 min. The calls in the intervention group followed the principles of the motivational interview, and in the calls to the women in the control group, the women were encouraged to continue BF, and resolutions to possible doubts were offered. At the 3rd month, the women were contacted by phone by another researcher for the collection of the results variables. In both cases, telephone contact was attempted up to 3 times for 1 week before considering the absence of response as a loss of the study.

Outcome measures

The variables collected at baseline included the following: (i) sociodemographic variables: age, stable partner (yes/no), educational level (no education, elementary, high school or higher), employment status, and socioeconomic level (< € 13,000/year; € 13,001–21,700/year; and > € 21,700/year); (ii) clinical variables: body mass index, pregnancy weeks, type of delivery, previous children, and newborn weight; and (iii) factors related to BF success: BF experience and BF training. Age, education level, employment situation, and previous experience with BF were the variables used in the randomisation process by minimisation.

As a main variable, the presence of PPD was assessed through the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a tool that has been translated and validated in Spanish60. The EPDS contains questions regarding how the woman has felt during the last 7 days61. Women with scores greater than 10 have a high probability of meeting the diagnostic criteria for depression. The EPDS was collected at the third month postpartum. In this study, a score of 11 or higher on the EPDS was considered a cut-off point for the diagnosis of PPD with a sensitivity and specificity of 81 and 88%, respectively2.

In this study, information regarding BF was collected at the time of the PPD assessment. Information on the week duration and maintenance of BF (exclusive or not exclusive) was collected in the third month postpartum.

The preintervention and third-month-postpartum BSE levels were also analysed using the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale Short-Form (BSES-SF)62. This 14‐item scale has good internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.92. This scale identifies women at the greatest risk of discontinuing BF, assesses BF behaviours and cognitions to individualise confidence‐building strategies, and evaluates the effectiveness of various interventions. This scale has been validated in Spanish.

Ethical considerations

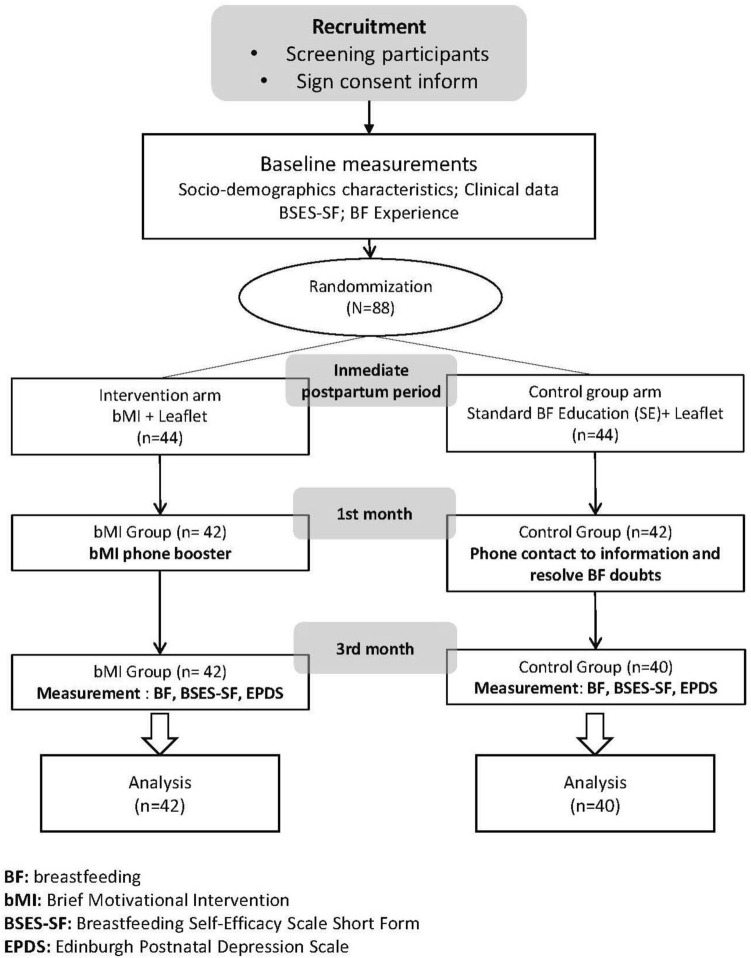

The Badajoz Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Extremadura Health Service approved the study in 2017 (180022909). The study protocol was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The protocol of this study was registered on Clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03357549; Date of first registration: 30/11/2017). The participants received written information regarding the aims of the study and were informed that participation was voluntary in accordance with the general recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki (“World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki,” 2013). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The confidentiality of the participants was maintained at all times. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram of the study.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the study.

The women participating in this study who were diagnosed with PPD by the EPDS were referred to psychiatric services for proper care.

Data collection

The baseline variables were collected from the clinical history and initial interview before the randomisation of the participants to each study group. The data from the third month were collected by telephone calls between May 2018 and January 2019. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram of the study.

Validity and reliability

The EPDS validated in Spanish women has a positive predictive value of 63.2% and a negative predictive value of 97.7%. The Spanish version of the BSES-SF has good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.91. To minimise the possibility of bias due to unmeasured characteristics related to the use of different interviewers, the same midwife conducted the bMI and the BF education sessions. Due to randomisation, all participants had an equal chance of receiving the intervention.

Data analysis

A similar distribution of the baseline characteristics was verified. The quantitative variables were compared between the groups with a Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test according to the normality of their distribution. A Pearson chi-squared test and Fisher's exact test were used for the comparisons of the categorical variables.

To analyse the effect of the intervention on the development of PPD, the scores on the EPDS scale were compared between both study arms. To quantify the strength of the association between the bMI and the development of PPD, a multinomial logistic regression was performed, which allowed us to obtain estimates of the odds ratio (OR) and adjusted OR (aOR) when introducing the maintenance of BF at the time of PPD assessment as an independent variable in the model. All estimates were conducted with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). All statistical procedures were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York).

Finally, to determine the role of the increase in BSE and duration of BF in the association between bMI and PPD, mediation and moderation analyses were performed according to the Hayes method63,64 through the PROCESS macro64 2016 version in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York).

Results

Participation was requested from 88 women who met the inclusion criteria, and none of them declined to participate. During the follow-up period, in total, six losses occurred, all of which were due to the impossibility of phone contact (Fig. 1). These women were somewhat younger, with a mean age (± standard deviation) of 27.83 (± 8.04) years vs. 33.18 (± 4.76) years among those who completed the study (p = 0.013); had a lower level of income (income < € 13,001/year: 66.7% vs. 9.2%, p = 0.002); and were mostly first-time mothers (83.3% vs. 37.8%, p = 0.016).

The mean age of the women was 32.82 years (± 5.17). More women in the intervention group had higher education (34.1% vs 18.2%) and previous experience with BF (63.6% vs 56.8%). No differences were found in the other baseline variables. There were no differences in the baseline score on the BSES-SF as follows: 59.14 (± 9.35) in the bMI group and 59.41 (± 8.45) in the control group (p = 0.886) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Total sample N = 88 |

bMI group n = 44 |

Control group n = 44 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) M (SD) | 32.82 (5.17) | 32.4 (5.99) | 33.25 (4.21) |

| BMI median [IQR] | 22.32 [20.25–26] | 22.23 [20.66–24.86] | 22.67 [19.89–27.08] |

| Education n (%) | |||

| No studies/primary | 29 (33) | 11 (25) | 18 (40.9) |

| Secondary | 36 (40.9) | 18 (40.9) | 18 (40.9) |

| University/postgraduate | 23 (26.1) | 15 (34.1) | 8 (18.2) |

| Employment n (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 37 (42) | 18 (40.9) | 19 (43.2) |

| Work for others | 46 (52.3) | 25 (56.8) | 21 (47.7) |

| Own-account work | 5 (5.7) | 1 (2.3) | 4 (9.1) |

| Annual family income n (%) | |||

| < 13,000 € | 12 (13.6) | 7 (15.9) | 5 (11.4) |

| 13,000–21,700 € | 61 (69.3) | 29 (65.9) | 32 (72.7) |

| > 21,700 € | 15 (17) | 8 (18.2) | 7 (15.9) |

| Has more children n (%) | 58 (65.9) | 29 (65.9) | 29 (65.9) |

| Previous experience BF n (%) | 53 (60.2) | 28 (63.6) | 25 (56.8) |

| Received specific training in BF n (%) | 38 (43.2) | 19 (43.2) | 19 (43.2) |

| Pregnancy weeks M (SD) | 39.14 (1.24) | 39.16 (1.18) | 39.11 (1.32) |

| Newborn weight (grams) M (SD) | 3270.6 (451.82) | 3241.14 (410.58) | 3300 (492.63) |

| Type of delivery n (%) | |||

| Spontaneous | 81 (92) | 40 (90.9) | 41 (93.2) |

| Forceps | 5 (5.7) | 2 (4.5) | 3 (6.8) |

| Vacuum | 2 (2.3) | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0) |

| BSES-SF Score M (SD) | 59.27 (8.86) | 59.14 (9.35) | 59.41 (8.45) |

M mean, SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range, bMI brief motivational intervention, BF breastfeeding, BSES-SF Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale Short Form, BMI body mass index.

The duration of BF (including both exclusive and nonexclusive) was 11.06 (± 2.94) weeks in the bMI group compared to 9.02 (± 4.44) weeks in the control group (p = 0.013). In the mothers who completed the follow-up, the baseline BSES-SF scores were practically the same in both groups. However, the intervention group had 4.13 points more than the intervention group at the third month postpartum (Table 3). When comparing the intra-group scores, we found that in the intervention group, the self-efficacy score was increased by 6.24 points, while in the control group, there were no significant differences.

Table 3.

Intra-group and inter-group comparison of breastfeeding self-efficacy.

| bMI group n = 42 |

Control group n = 40 |

p value (inter-group) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSES-SF Basal Score Mean (SD) | 59.14 (9.31) | 59.68 (8.66) | 0.7901 |

| BSES-SF 3rd month Score Mean (SD) | 65.38 (6.23) | 61.25 (8.74) | 0.0151 |

| p value (intra-group) | < 0.0011 | 0.3041 |

bMI brief motivational intervention, BSES-SF Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale Short Form.

1Student’s t-test.

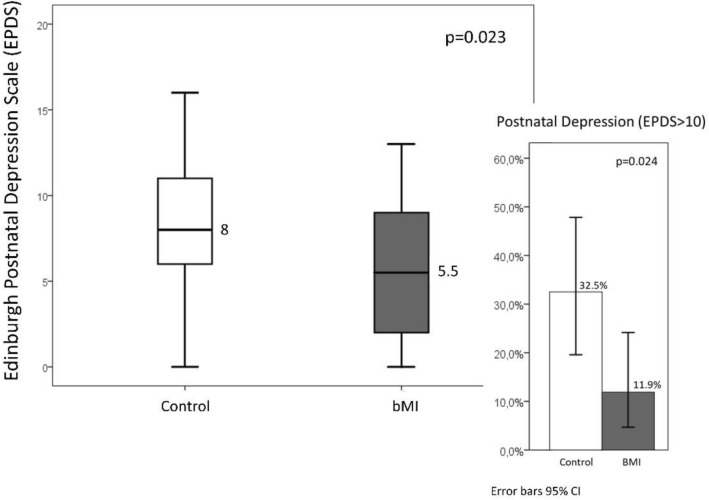

The EPDS score in the control group, with a median [interquartile range] of 8 [6–11], was higher than that in the group that received the bMI, with a median of 5.5 [1.75–9] (Fig. 2). When considering scores above 10, which indicate a high probability of a PPD diagnosis, the percentage of women with a probable diagnosis of PPD was higher in the control group (30% vs. 11.9%) (Fig. 2). When the magnitude of the association was measured, we found that the women who received the intervention were less likely to score above 10 on the EPDS, with an OR of 0.32 (95% CI 0.1; 0.99) (p = 0.050). This association magnitude hardly varied when adjusting this effect for BF at the time of the evaluation (aOR of 0.33 [95% CI 0.10; 1.08] p = 0.068).

Figure 2.

Analysis of postpartum depression in the study groups.

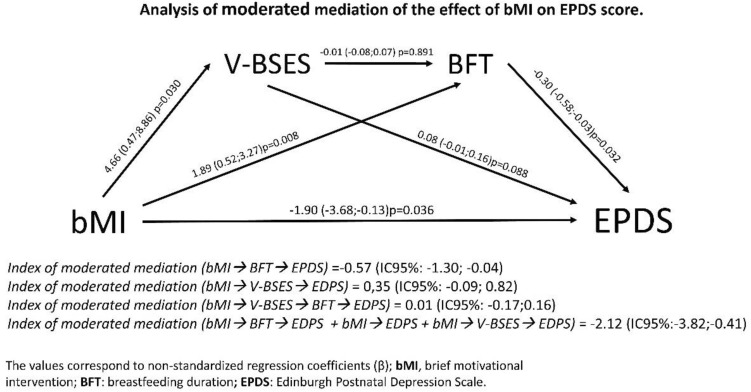

The mediation/moderation analyses showed that the effect of the bMI on the variation in BSE did not mediate the effect of the intervention on the score on the EDPS scale, with a β mediation/moderation index of 0.35 (95% CI − 0.09; 0.82) (Fig. 3). However, this mediation/moderation analysis showed that the effect of the intervention on the BF time acted as a mediator of the effect of bMI on the EPDS score, with a β moderation/mediation index of − 0.57 (95% CI − 1.30; − 0.04) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Analysis of the moderated mediation of the effect of the brief motivational intervention on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale.

The interaction analyses showed that educational level and previous experience with BF did not interfere with the effect of the bMI on the EPDS score (F = 0.672, p = 0.514; and F = 1.541, p = 0.218, respectively). In addition, analysis of the possible moderating effect of the increase in BSE on the effect of the bMI on PPD showed that it did not act as a moderator as follows: it had a β mediation/moderation index of − 0.25 (95% CI − 0.20; 0.16) (p = 0.786).

Discussion

Our results show that women who received a bMI to promote BF during the immediate postpartum period with telephone reinforcement at 1 month postpartum scored lower on the EPDS at the third postpartum month than those who received an educational session concerning BF at the same time. Our analyses show that the women who received bMI had a lower probability of scoring above 10, which is a score associated with a high probability of the existence of PPD. This probability is slightly modified when considering the maintenance of BF at the time of the PPD assessment.

The existing evidence concerning effective interventions for the prevention of PPD has been analysed in several systematic reviews65–67. In a 2013 systematic review65, it was found that postpartum visits by nurses or midwives, telephone peer support, and interpersonal psychotherapy were effective in reducing symptoms associated with depression. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis66 found that cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal therapy were effective interventions to prevent PPD. The bMI can be classified as an interpersonal therapy65, which could explain the effect of the intervention on the EPDS score.

To better understand the results obtained by the bMI on the development of feelings associated with PPD, mediation/moderation analyses were carried out, which showed that a part of the effect of the bMI on the EPDS score was mediated by the effect of the bMI on the duration of BF. The women in the intervention group had a longer duration of BF, which has been associated with a lower probability of developing PPD in some studies11,21,28. Although the evidence concerning the association between BF and PPD is unclear, some authors note that women with PPD have a shorter duration of BF25–27, and other authors note that women who breastfeed are less likely to develop PPD11,21,28. The mediating effect of BF duration on the relationship between bMI and EPDS scores found in our study reinforces the hypothesis of these authors, who found a protective effect of BF on PPD23,68. Moreover, in our study, the previous presence of depressive symptoms was ruled out. However, a large part of the effect of bMI on PPD is due exclusively to the intervention. A bMI aiming to promote breastfeeding could indirectly act in the development of negative feelings associated with depression, producing a protective effect34. Similar interventions based on motivational interviewing and Bandura's theory of self-efficacy have found that there is an increase in the ability to seek help by women and a decrease in the risk of developing PPD during the postpartum period34,54.

Additionally, the applied bMI achieved a greater increase in BSE than the control intervention, and a higher level of BSE has been associated with a lower EPDS score29–32. However, the mediation/moderation analyses showed that although the bMI produced a greater increase in BSE than the control intervention, this increase did not mediate the effect that bMI had on developing PPD. These analyses indicate that the bMI also does not moderate the effect of developing PPD. The reason for this discrepancy with previous evidence could be that a higher BSE is also associated with a longer duration of BF69–72, and the latter is truly related to the development of PPD.

Therefore, the bMI applied in this study is effective in preventing the development of PPD partially due to the intervention and partially due to its effect on the duration of BF. To our knowledge, this is the first to analyse the impact of an intervention directly aiming to provide BF support on the development of PPD using mediation/moderation analyses. This approach allowed us to estimate the direct and indirect causal effect paths of the intervention on the EPDS score. The role as mediator of BF that we observed in our results allows us to suppose that other interventions aiming to increase the duration of BF could have the same collateral effect on the psychological well-being of women. However, more research is needed to clarify whether other interventions aiming to promote BF could have the same effect on PPD. Furthermore, although the bMI appears to be effective in promoting BF47–50, additional studies are still needed to analyse this efficacy in different situations. If these results are confirmed, the convenience of including this type of intervention in routine healthcare practice could be reinforced. The bMI applied in this study is easily integrated into clinical practice. The application of this intervention by nursing and midwifery through its integration into the usual care of mothers and babies could be feasible and easily achievable since it only requires an investment in the specific training of professionals73. Increasing the duration of BF could have an important impact on public health due to the associated benefits, such as the reduction in infant and female morbidity and mortality22,23, to which could be added a reduction in the burden of disease associated with PPD. This approach could make the widespread implementation of programs to promote BF through bMI a cost–benefit practice, as has occurred in other clinical settings73.

Limitations

The findings of this study are limited by its design since the intervention was applied in women without a history of certain psychiatric disorders (depression, depression and anxiety during pregnancy, or postpartum depression)7,10. Such history is one of the most relevant risk factors for the development of PPD; thus, the effectiveness of this intervention could be diminished in women with a psychiatric history. Furthermore, an assessment of baseline EPDS score was not carried out in this study. Although the program of medical check-ups to follow up the pregnancy of the national health system contemplates depression symptoms evaluation, the determination of depression through the clinical history may not have been effective in all cases. Additionally, it was not applied in women who gave birth by caesarean section or had complications in pregnancy, which are two other factors associated with PPD13,14. Therefore, it could be necessary to investigate whether this bMI aiming to promote BF has an impact on the development of PPD in women with these characteristics. Finally, this intervention aimed to promote BF; thus, given its design, it would not be feasible to use this bMI to help prevent PPD in women who are unwilling or unable to engage in BF. A modification in the design of the bMI would be required to adapt it to preventing the development of PPD specifically.

Despite our efforts to achieve a balanced distribution of the variables strongly associated with the outcome using randomisation by minimisation, between-group baseline differences in education level and previous experience with BF were found. Although these differences were not very important, these factors were introduced into the adjusted models to prevent their effect on the results. Furthermore, some characteristics of the women classified as lost to follow-up, such as primiparity or low socioeconomic status, are associated with a greater probability of developing PPD. More studies are needed to evaluate how these factors could affect the possible implementation of intervention programmes.

Conclusions

A bMI for the promotion of BF applied during the immediate postpartum period in women who initiate BF in the first hour of life of the newborn and reinforced by one telephone call per month is associated with a lower score on the EPDS at the third postpartum month.

Part of the effect of this bMI on the EPDS score is due to the intervention itself. However, a significant part of the effect is mediated by the effect of the bMI on the duration of BF, which could support evidence associating a longer duration of BF with a lower probability of PPD development11,21,28.

Given the importance of both improving the duration of BF and preventing PPD, more research is needed to support the findings found in this study. In addition, future studies should analyse the efficacy of the bMI in women with greater susceptibility to the development of PPD, such as women with a history of psychiatric disorders, those who deliver by caesarean section, and those with complications during pregnancy.

Author contributions

C.F.A.: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Investigation; Formal analysis; Writing-original draft; Funding acquisition; E.S.M.: Investigation; Writing-review and editing; S.C.D.: Investigation; Writing-review and editing; P.S.G.: Investigation; Writing-review and editing; S.C.G.: Conceptualisation; Methodology; Formal analysis; Writing-review and editing; Project administration; Funding acquisition.

Funding

This study was awarded the “International Confederation of Midwives Research Award 2018” funded by Johnson & Johnson. The members of the GISyC group are funded by “Programa Operativo FEDER Extremadura (2014–2020) y Fondo Europeo Desarrollo Regional (FEDER)” (GR18146).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mendoza BC, Saldivia S. Actualización en depresión postparto: el desafío permanente de optimizar su detección y abordaje. Rev. Med. Chil. 2015;143:887–894. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872015000700010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levis B, Negeri Z, Sun Y, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2020;371:4022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pope CJ, Mazmanian D. Breastfeeding and postpartum depression: An overview and methodological recommendations for future research. Depress. Res. Treat. 2016;2016:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2016/4765310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brummelte S, Galea LAM. Postpartum depression: Etiology, treatment and consequences for maternal care. Horm. Behav. 2016;77:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartmann JM, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Cesar JA. Postpartum depression: prevalence and associated factors. Cad. Saude Publica. 2017;33:94016. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00094016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM V.pdf. Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Tratornos Mentales 1000 (2014).

- 7.O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013;9:379–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stotland NL. Mental health aspects of women’s reproductive health: A global review of the literature. Psychiatr. Serv. 2010;61:421–421. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Josefsson A, Sydsjö G. A follow-up study of postpartum depressed women: Recurrent maternal depressive symptoms and child behavior after four years. Arch. Womens Ment. Health. 2007;10:141–145. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0185-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pope CJ, Mazmanian D, Bédard M, Sharma V. Breastfeeding and postpartum depression: Assessing the influence of breastfeeding intention and other risk factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;200:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Q, et al. Impact of some social and clinical factors on the development of postpartum depression in Chinese women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:226. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-02906-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R, Dennis CL. Prevalence and risk factors for comorbid postpartum depressive symptomatology and anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;198:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alzahrani AD. Risk factors for postnatal depression among Primipara mothers. Span. J. Psychol. 2019;22:1–8. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2019.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Özcan NK, Boyacıoğlu NE, Dinç H. Postpartum depression prevalence and risk factors in Turkey: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017;31:420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding. WHOhttp://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs342/en/ (2017).

- 16.American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012;129:e827–e841. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmadizar F, et al. Breastfeeding is associated with a decreased risk of childhood asthma exacerbations later in life. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:649–654. doi: 10.1111/pai.12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unar-Munguía M, et al. Breastfeeding mode and risk of breast cancer. J. Hum. Lact. 2017;33:890334416683676. doi: 10.1177/0890334416683676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colaizy TT, et al. Impact of optimized breastfeeding on the costs of necrotizing enterocolitis in extremely low birthweight infants. J. Pediatr. 2016;175:100–105.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horta BL, Loret-de-Mola C, Victora CG. Long-term consequences of breastfeeding on cholesterol, obesity, systolic blood pressure and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:30–37. doi: 10.1111/apa.13133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdhury R, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:96–113. doi: 10.1111/apa.13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horta BL, Victora CG. Long-Term Health Effects of Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review. WHO Library; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Victora CG, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization & UNICEF . Global Nutrion Target 2025. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Bunn J, Lovel H, Harrington R. Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: A cohort study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61:946–952. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darcy JM, et al. Maternal depressive symptomatology: 16-month follow-up of infant and maternal health-related quality of life. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2011;24:249–257. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva CS, et al. Association between postpartum depression and the practice of exclusive breastfeeding in the first three months of life. J. Pediatr. (Versão em Port.) 2017;93:356–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunha, M. C. M. et al. The evidence-based practice: Breastfeeding as a preventive factor for postpartum depression. in Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing vol. 621 121–130 (Springer, Cham, 2018).

- 29.Ngo LTH, Chou HF, Gau ML, Liu CY. Breastfeeding self-efficacy and related factors in postpartum Vietnamese women. Midwifery. 2019;70:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Sá Vieira Abuchaim E, Caldeira NT, Di Lucca MM, Varela M, Silva IA. Postpartum depression and maternal self-efficacy for breastfeeding: Prevalence and association. ACTA Paul. Enferm. 2016;29:664–670. [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Sa Vieira E, Caldeira NT, Eugênio DS, di Lucca MM, Silva IA. Breastfeeding self-efficacy and postpartum depression: a cohort study. Rev. Lat. Am. Enfermagem. 2018;26:e3035. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.2110.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zubaran C, Foresti K. The correlation between breastfeeding self-efficacy and maternal postpartum depression in southern Brazil. Sex Reprod. Healthc. 2013;4:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zlotnick C, Tzilos G, Miller I, Seifer R, Stout R. Randomized controlled trial to prevent postpartum depression in mothers on public assistance. J. Affect. Disord. 2016;189:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shorey S, Chan SWC, Chong YS, He H-GG. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a postnatal psychoeducation programme on self-efficacy, social support and postnatal depression among primiparas. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015;71:1260–1273. doi: 10.1111/jan.12590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milgrom J, Schembri C, Ericksen J, Ross J, Gemmill AW. Towards parenthood: An antenatal intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and parenting difficulties. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;130:385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mao HJ, Li HJ, Chiu H, Chan WC, Chen SL. Effectiveness of antenatal emotional self-management training program in prevention of postnatal depression in Chinese women. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 2012;48:218–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2012.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Özkan SA, Kücükkelepce DS, Korkmaz B, Yılmaz G, Bozkurt MA. The effectiveness of an exercise intervention in reducing the severity of postpartum depression: A randomized controlled trial. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 2020;56:844–850. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewis BA, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline data for the Healthy Mom II Trial: A randomized trial examining the efficacy of exercise and wellness interventions for the prevention of postpartum depression. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2018;70:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surkan PJ, Gottlieb BR, McCormick MC, Hunt A, Peterson KE. Impact of a health promotion intervention on maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months postpartum. Matern. Child Health J. 2012;16:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0729-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacArthur C, et al. Effects of redesigned community postnatal care on womens’ health 4 months after birth: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:378–385. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07596-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brugha TS, Morrell CJ, Slade P, Walters SJ. Universal prevention of depression in women postnatally: Cluster randomized trial evidence in primary care. Psychol. Med. 2011;41:739–748. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiggins M, et al. The social support and family health study: A randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of two alternative forms of postnatal support for mothers living in disadvantaged inner-city areas. Health Technol. Assess. 2004 doi: 10.3310/hta8320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dennis CL, et al. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: Multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:280–283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werner EA, et al. (2015) PREPP: Postpartum depression prevention through the mother–infant dyad. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health. 2015;192(19):229–242. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0549-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Connor E, Senger CA, Henninger ML, Coppola E, Gaynes BN. Interventions to prevent perinatal depression: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019;321:588–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franco-Antonio C, Calderón-García JF, Santano-Mogena E, Rico-Martín S, Cordovilla-Guardia S. Effectiveness of a brief motivational intervention to increase the breastfeeding duration in the first 6 months postpartum: Randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020;76:888–902. doi: 10.1111/jan.14274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilhelm SL, Stepans MBF, Hertzog M, Rodehorst TKC, Gardner P. Motivational interviewing to promote sustained breastfeeding. JOGNN J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35:340–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilhelm SL, Aguirre TM, Koehler AE, Rodehorst TK. Evaluating motivational interviewing to promote breastfeeding by rural Mexican-American mothers: The challenge of attrition. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2015;38:7–21. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2014.971977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elliott-Rudder M, Pilotto L, McIntyre E, Ramanathan S. Motivational interviewing improves exclusive breastfeeding in an Australian randomised controlled trial. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2014;103:e11–e16. doi: 10.1111/apa.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franco-Antonio C, Santano-Mogena E, Sánchez-García P, Chimento-Díaz S, Cordovilla-Guardia S. Effect of a brief motivational intervention in the immediate postpartum period on breastfeeding self-efficacy: Randomized controlled trial. Res. Nurs. Health. 2021;44:295–307. doi: 10.1002/nur.22115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naroee H, Rakhshkhorshid M, Shakiba M, Navidian A. The Effect of motivational interviewing on self-efficacy and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding rates: A quasi-experimental study. Breastfeed. Med. 2020;15:522–527. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2019.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Addicks SH, McNeil DW. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing to support breastfeeding among Appalachian women. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2019;48:418–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holt C, Milgrom J, Gemmill AW. Improving help-seeking for postnatal depression and anxiety: A cluster randomised controlled trial of motivational interviewing. Arch. Womens. Ment. Health. 2017;20:791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0767-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fernandez y Garcia E, et al. Pediatric-based intervention to motivate mothers to seek follow-up for depression screens: The Motivating Our Mothers (MOM) trial. Acad. Pediatr. 2015;15:311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Franco-Antonio C, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief motivational intervention to improve exclusive breastfeeding rates: Study protocol. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019;75:888–897. doi: 10.1111/jan.13917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Han B, Enas NH, McEntegart D. Randomization by minimization for unbalanced treatment allocation. Stat. Med. 2009;28:3329–3346. doi: 10.1002/sim.3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Comité de Lactancia Materna AEP. Recomendaciones sobre lactancia materna. 16 http://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/201202-recomendaciones-lactancia-materna.pdf (2012).

- 59.Comité de Lactancia Materna AEP. ¡Enhorabuena por tu reciente maternidad! AEPhttp://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/documentos/triptico-lactancia-maternidad.pdf (2015).

- 60.Garcia-Esteve L, Ascaso C, Ojuel J, Navarro P. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in Spanish mothers. J. Affect. Disord. 2003;75:71–76. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oliver-Roig A, et al. The Spanish version of the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form: Reliability and validity assessment. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012;49:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017;98:39–57. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dennis C, Dowswell T. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochraine Database Syst. Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1017/S1463423614000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Connor, E. et al. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to Prevent Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2019). [PubMed]

- 67.Sockol LE, Epperson CN, Barber JP. Preventing postpartum depression: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013;33:1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grummer-Strawn LM, Rollins N. Summarising the health effects of breastfeeding. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 2015;104:1–2. doi: 10.1111/apa.13136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blyth R, et al. Effect of maternal confidence on breastfeeding duration: An application of breastfeeding self-efficacy theory. Birth. 2002;29:278–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowles BC. Promoting breastfeeding self-efficacy: Fear appeals in breastfeeding management. Clin. Lact. 2011;2:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kingston D, Dennis C, Sword W. Exploring breast-feeding self-efficacy. J Perinat Neonat Nurs. 2015;21:207–215. doi: 10.1097/01.JPN.0000285810.13527.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oliver Roig, A. El abandono prematuro de la lactancia materna:: incidencia , factores de riesgo y estrategias de protección , promoción y apoyo a la lactancia. España (2012).

- 73.Schwindt R, Agley J, Newhouse R, Ferren M. Screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) training for nurses in acute care settings: Lessons learned. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019;48:19–21. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2019.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]