Abstract

Background

Right ventricular impairment (RVI) secondary to altered hemodynamics contributes to morbidity and mortality in adult patients after tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) repair. The goal of this study was to describe signaling pathways contributing to right ventricular (RV) remodeling by analyzing over lifetime alterations of RV gene expression in affected patients.

Methods

RV tissue was collected at the time of cardiac surgery in 13 patients with a diagnosis of TOF. RNA was isolated and whole transcriptome sequencing was performed. Gene profiles were compared between a group of 6 adults with signs of RVI undergoing right ventricle to pulmonary artery conduit surgery and a group of 7 infants, undergoing TOF correction. Definition of RVI in adult patients was based on clinical symptoms, evidence of RV hypertrophy, dilation, dysfunction or elevated pressure on echocardiographic, cardiovascular magnetic resonance, or catheterization evaluation.

Results

Median age was 34 years in RVI patients and 5 months in infants. Based on P adjusted value <0.01, RNA sequencing of RV specimens identified a total of 3,010 differentially expressed genes in adult patients with TOF and RVI as compared to infant patients with TOF. Gene Ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes databases highlighted pathways involved in cellular metabolism, cell-cell communication, cell cycling and cellular contractility to be dysregulated in adults with corrected TOF and chronic RVI.

Conclusions

RV transcriptome profiling in adult patients with RVI after TOF repair allows identification of signaling pathways, contributing to pathologic RV remodeling and helps in the discovery of biomarkers for disease progression and of new therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Right ventricular impairment (RVI), congenital heart disease, transcriptome profiling, molecular signaling pathways

Introduction

Due to improvements in diagnostic techniques, interventional procedures and surgical treatment more children with complex congenital heart disease (CCHD) survive into adulthood (1,2). The right ventricle is often stressed by the underlying anatomical abnormalities, surgical lesions, or pulmonary valve defects leading to pressure and/or volume overload (3). Right ventricular impairment (RVI) subsequently occurs in about 26% of CCHD patients (4) and might lead to sudden cardiac death and life-threatening long-term complications. Secondary to altered hemodynamics and myocardial stress, right ventricular (RV) remodeling, such as hypertrophy, fibrosis, arrhythmias, inflammation and dysfunction, occurs (3,5). Activation of fibroblasts, upregulation of inflammatory pathways, increased release of neurohormones and differences in gene regulation of cardiac metabolism, energy production and mitochondrial function occur in the stressed right ventricle (3,6). Additionally, the right ventricle has been suggested to suffer earlier than the left ventricle from oxidative stress in response to hemodynamic stress, which might contribute to the development of pathologic conditions (3). Preventing the transition from compensated- to non-compensated right heart failure (HF) in affected patients by timely interventions, operations, or targeted medical therapy would decrease morbidity and mortality in affected CCHD patients. However, at this point, the severity of pathologic RV remodeling can only inaccurately be predicted by clinical examination and imaging techniques (7). Consequently, the identification of biomarkers to optimize patient treatment and determine the extent of RV myocardial remodeling is of utmost importance. Furthermore, patients currently receive standard left ventricular (LV) failure therapies which are often ineffective in the right ventricle (7,8). A potential reason for this failure is the differences in molecular signaling pathways between the right and the left ventricle which cause diverse adaption strategies to pathologic conditions (6,7). To date, data referring to molecular pathways contributing to RV remodeling and RVI in patients with CCHD are scarce. The aim of this study was to identify differential gene expression over time in affected patients and to define molecular signaling pathways which might play a pivotal role in the development of RVI in patients with CCHD.

We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-894).

Methods

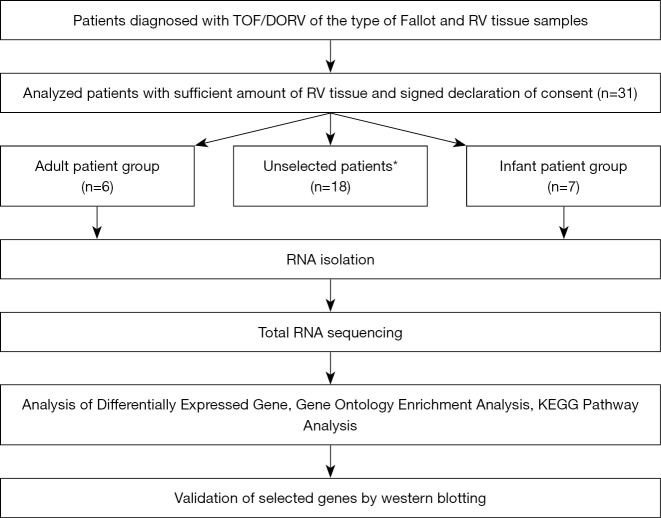

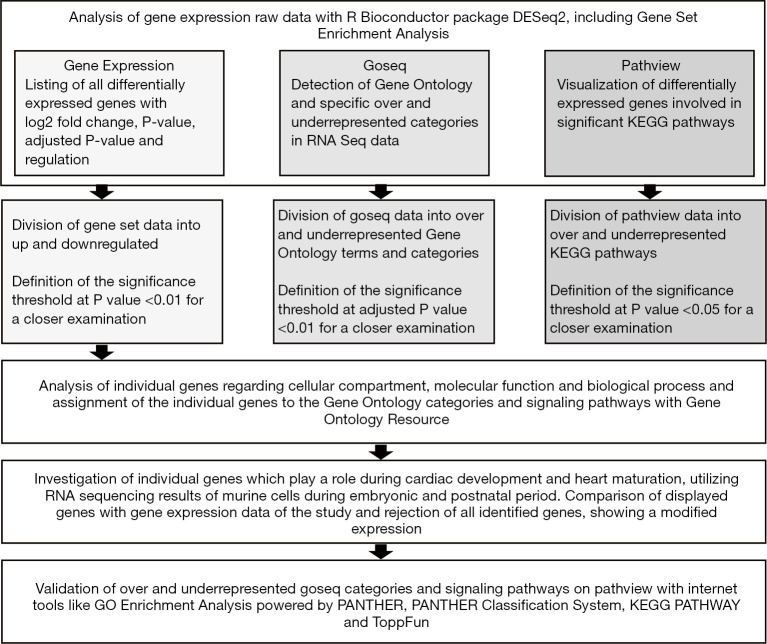

The study protocol is depicted in Figure 1. Briefly, RV tissue was obtained from patients with a primary diagnosis of tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) at the time of surgical treatment after informed consent. Surgeries included corrective repair for infants or elective replacement of right ventricle to pulmonary artery (RV-PA) conduit for adult patients. Clinical, laboratory, electrocardiogram and imaging data were analyzed by medical chart review. The criteria for RVI were selected based on the International Right Heart Foundation Working Group recommendations (9) and the scientific statement of the American Heart Association (10). Patients with syndromes and any other organ failure were excluded. Total RNA was isolated, RNA quantity was measured, and RNA quality was assessed. Whole transcriptome analysis was performed by total RNA sequencing of cardiac tissue samples as previously described (11). RNA library was prepared, quality and quantity of the RNA library were estimated, and RNA sequencing of 100 bp paired-end runs was performed with Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, California, United States). The number of reads mapping to annotated genes was quantified after alignment and differential gene expression between groups was performed. Pathway and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, which are common approaches to interpret gene expression data based on functional annotation, were performed. Bioinformatical tools used to validate pathway analysis, biological activity and allocation of individual genes to Gene Ontology categories are depicted in Figure 2 and selected suitable genes are shown in Figure S2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the performed process of the study design. Patient enrollment with underlying anatomical diagnosis, group classification and process of sample preparation with analysis of results. *, unselected patients due to genetic disorders, lacking clear clinical characterization and insufficient signs of RV impairment. DORV, double outlet right ventricle; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RV, right ventricular; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot.

Figure 2.

Bioinformatical analysis of whole transcriptome differential expression data. Bioinformatical analysis performed to evaluate significant biological pathways derived from whole transcriptome differential gene expression data. GO, Gene Ontology; goseq, gene ontology for RNA Sequencing; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; PANTHER, Protein Analysis Through Evolutionary Relationships; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RNA Seq, RNA Sequencing.

The total of 3,010 differentially expressed genes were compared to 50 most significant genes, regulating cardiac development and heart maturation, which were identified by RNA sequencing of murine cells during embryonic and postnatal period. Overlapping genes were not included in further interpretation of results (12) (Figure S1 and Table S9). Western blot was performed as previously described (11) for selected proteins isolated from RV myocardial tissue of affected patients.

Statistic evaluation was implemented by applying R Bioconductor package DEseq2 to transcriptome profiles and tested for differential gene expression between adult and infant patients. The P values were corrected for the purpose of multiple testing by Benjamini and Hochberg procedure. The level of significance was set at a P value of less than 0.01 and a fold-change value of greater than 2 or less than −2. Based on that, all significant differentially expressed genes were selected for further analysis. The results of Gene Ontology (GO) and Pathway analysis with an adjusted P value less than 0.01 (GO) and a P value less than 0.05 (KEGG) were assigned as significant.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethics committee (approval 10/16/2017, number 242/17S, and approval 01/11/2017, number 592,16S) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was taken from all patients.

Please see Supplementary file (Appendix 1) for detailed description of Material and Methods.

Results

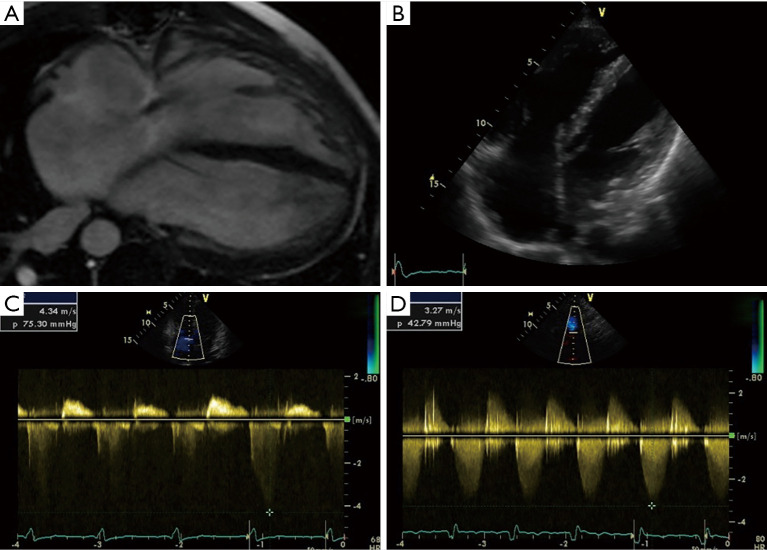

Myocardial tissue samples were collected from a group of 6 adult patients with signs of chronic RVI undergoing RV-PA conduit surgery (“cases”) and from a group of 7 infant patients undergoing elective TOF correction (“controls”). Patients in the “case” and the “control” group were in median 34 and 0.5 years, respectively, old at the time of sample collection (range, 29 to 62 years and 4.8 to 5.8 months, respectively). Follow-up time since corrective surgery was 34 years in median (range, 27 to 50 years) in adult patients with CCHD and RVI. Underlying structural heart disease was TOF in 12 patients and double outlet right ventricle (DORV) of the type Fallot in 1 patient (Tables 1,2). Clinical, laboratory, cardiopulmonary exercise testing and imaging parameters of adult patients are depicted in Table 3 (13,14). All patients of the case group had progressive exercise intolerance and were in New York Heart Association functional class II and higher. Most patients showed engorgement of their jugular veins or enlarged liver on physical examination. Three of 6 patients showed severe stenosis of the pulmonary valve and 3 of 6 patients showed severe pulmonary regurgitation. There was RV hypertrophy and enlargement in all patients on transthoracic echocardiography and/or cardiovascular magnetic resonance tomography (CMR). Exemplary imaging is depicted in Figure 3.

Table 1. Patients characteristics of the adult patient group.

| Adult patients | Identification number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111087 | 111088 | 111089 | 111091 | 111092 | 111094 | |

| Age (years) | 31 | 43 | 29 | 37 | 61 | 31 |

| Sex (M/F) | M | F | F | F | F | F |

| Height (cm) | 172 | 174 | 165 | 156 | 162 | 150 |

| Weight (kg) | 66.3 | 75.9 | 63.1 | 68.5 | 73.1 | 44.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.3 | 25.1 | 23.1 | 28.4 | 27.8 | 20.0 |

| Anatomical diagnosis | DORV | TOF | TOF | TOF | TOF | TOF |

| Type of surgery | Allograft implantation | RVOTO resection | Conduit change | Conduit change | RVOTO resection, conduit change | Conduit change |

| Age at corrective repair (years) | 4 | 3.5 | 0.4 | 4 | 11 | 5 |

BMI, body mass index; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; RVOTO, right ventricular outflow tract obstruction; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot.

Table 2. Patients characteristics of the infant patient group.

| Infant patients | Identification number | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111093 | 111095 | 111096 | 111097 | 111099 | 111100 | 111198 | |

| Age (months) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Sex (M/F) | M | M | F | M | M | M | M |

| Height (cm) | 64 | 62 | 63 | 62.5 | 63 | 68 | 63 |

| Weight (g) | 7,605 | 5,950 | 5,960 | 7,405 | 5,900 | 6,960 | 5,700 |

| Anatomical diagnosis | TOF | TOF | TOF | TOF | TOF | TOF | TOF |

| Type of surgery | Corrective repair | Corrective repair | Corrective repair | Corrective repair | Corrective Repair | Corrective repair | Corrective repair |

TOF, tetralogy of Fallot.

Table 3. Clinical parameters, cardiorenal and cardiohepatic serum markers, electrocardiogram as well as imaging parameters and preoperative medication.

| Adult patients | Patient identification number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111087 | 111088 | 111089 | 111091 | 111092 | 111094 | |

| Clinical parameters | ||||||

| Functional capacity (NYHA classification) | II | III | II | III | IV | III |

| Peripheral edema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Engorgement of jugular veins | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| Enlargement of liver | 0 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 0 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cyanosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiorenal serum markers | ||||||

| GFR (mL/min) | – | 69 | 120 | 106 | 44 | 118 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.60 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 1.24 | 0.61 |

| Blood urine nitrogen (mg/dL) | 85.5 | 31.0 | 20.7 | 33.9 | 68.4 | 27.9 |

| Cardiohepatic serum markers | ||||||

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.591 | 1.25 | 0.430 | 0.25 | 2.49 | 0.33 |

| ɣ-GT (U/L) | 53.6 | 21.6 | 57.5 | 24.7 | 480 | 38.4 |

| AP (U/L) | 38.2 | 56.7 | 84.4 | 46.0 | 128 | 56.5 |

| Electrocardiogram | ||||||

| Right-axis deviation | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Incomplete/complete right bundle branch block | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Length of QRS interval (ms) | 200 | 100 | 110 | 100 | 120 | 120 |

| Abnormal repolarization | + | + | + | 0 | + | + |

| Atrial/ventricular tachyarrhythmias | +a | 0 | 0 | +b | +c | 0 |

| Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +d | 0 |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging | ||||||

| RVEF (%) | 50 | 52 | 67 | 57 | – | 52 |

| LVEF (%) | 51 | 58 | 59 | 68 | – | 60 |

| Pulmonary regurgitation fraction (%)A | 52 | 10 | 21 | 11 | – | – |

| RVSV (mL) | 121 | 87 | 92 | 48 | – | 58 |

| RVEDVI (mL/m2) | 138 | 89 | 84 | 51 | – | 80 |

| Increased RVEDVB | + | + | + | 0 | – | + |

| RVESVI (mL/m2) | 68 | 42 | 28 | 22 | – | 39 |

| Increased RVESVC | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

| Echocardiography | ||||||

| Decreased RVEFD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Pulmonary regurgitationE | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| PV Vmax (m/s) | 3.90 | – | 3.48 | 4.53 | 1.94 | 4.05 |

| PV mean PG (mmHg) | – | – | – | 54.52 | 11.24 | – |

| PV max PG (mmHg) | 60.78 | 85 | 48.5 | 82.07 | 15.07 | 65.73 |

| RV hypertrophy | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Increased RVPF | 0 | + | + | – | + | + |

| Preoperative medication | ||||||

| Beta-blocker | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Diuretic | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

0, not present; +, present; –, data not available. The electrocardiogram criteria for right ventricular impairment were taken from the scientific statement of the American Heart Association (10). The imaging reference values used were taken from the Guidelines for the Echocardiographic Assessment of Right Heart in Adults reported from the American Society of Echocardiography (13). The cut of value for moderate to severe pulmonary regurgitation were based on the publication of the Department of Cardiology and the Toronto Congenital Cardiac Care Centre for Adults (14). a, atrial fibrillation; b, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on exercise testing; c, atrial flutter and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in invasive electrophysiological examination; d, primary prophylactic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator with adequate shocks later on; A, moderate to severe pulmonary regurgitation fraction >20%; B, right ventricular enddiastolic volume index >80 mL/m2; C, right ventricular end-systolic volume index >46 mL/m2; D, RVEF <44%; E, moderate to severe pulmonary regurgitation; F, increased RVP: right ventricular pressure >40 mmHg. NYHA, New York Heart Association Class; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ɣ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVSV, right ventricular stroke volume; RVEDVI, right ventricular enddiastolic volume index; RVESVI, right ventricular end-systolic volume index; PV Vmax, maximum velocity over pulmonic valve; PV mean PG, mean pressure gradient over pulmonic valve; PV max PG, maximum pressure gradient over pulmonic valve; RV, right ventricular.

Figure 3.

Exemplary imaging from patient 111087 showing right ventricular enlargement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (A) and echocardiography (B) with elevated right ventricular pressure estimated by pressure gradient between the right ventricle and the right atrium on Doppler imaging (C). Echocardiographic continuous wave Doppler imaging illustrates severe stenosis and regurgitation of the right-ventricular-to-pulmonary-artery (RV-PA) allograft (D).

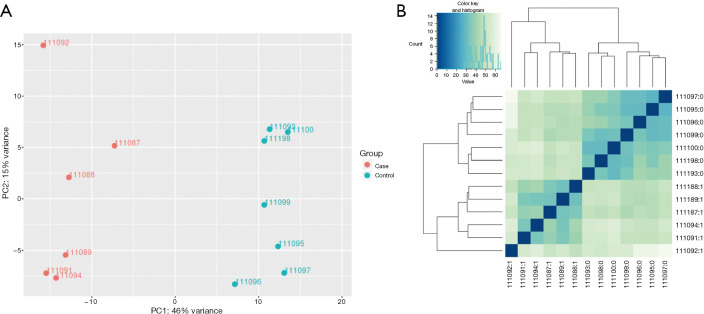

The statistical evaluation with Principal Component Analysis visualized well separated samples, demonstrating difference in the compared groups and homogeneity (Figure 4). Transcriptome profiling of RV specimens identified in total 23,398 genes to be differentially expressed in the case group of adult patients with RVI as compared to the control group of infant TOF patients. Thereof, 12,626 genes were upregulated, and 10,772 genes were downregulated. Considering a P adjusted value of less than 0.01 and a fold change value of greater than 2 and less than −2, a total of 3,010 genes were significantly differentially expressed. Of those, 1,703 genes were upregulated, and 1,307 genes were downregulated (Figure 5). Hierarchical clustering of the 100 most significantly differentially expressed genes is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis of adult TOF patients and RVI secondary to chronic RV volume and/or pressure overload compared to infant TOF patients. The diagram charted both groups as clusters, at which red dots symbolize the adult patients (“cases”) and blue dots the infant patients (“controls”) (A). The samples are well separated, demonstrating difference in the compared groups (B). Low variance and homogeneity within both clusters is the base for comparability. TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; RVI, right ventricular impairment; RV, right ventricular.

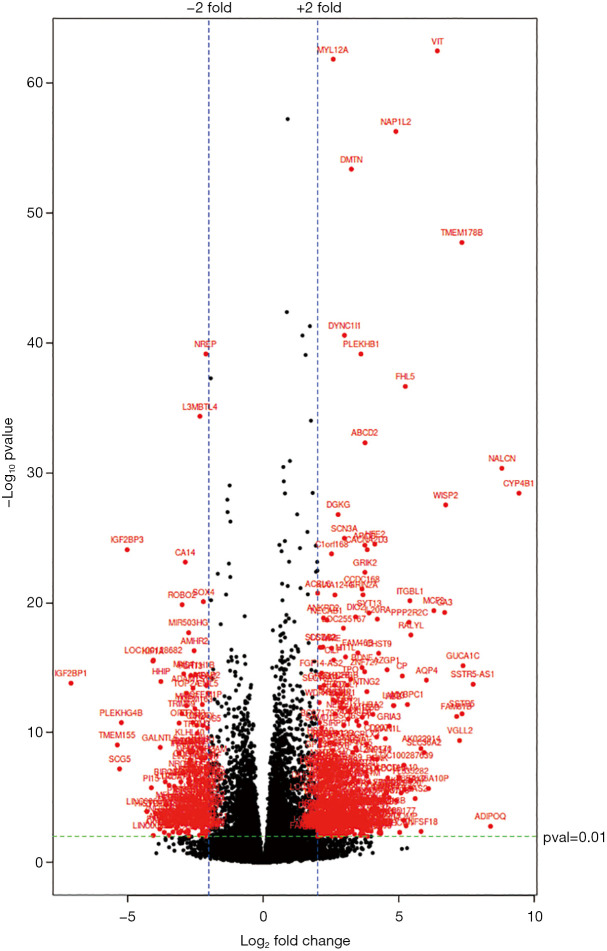

Figure 5.

Volcano Plot visualizes detected significantly dysregulated genes from gene expression analysis. The log 2-fold change is displayed on the x axis and the significance is shown on the y axis as the negative logarithm (log10scale) of the FDR corrected P value. The significance cutoff (P value <0.01) is highlighted with a green dashed line. Dysregulated genes which lie within the defined significant limits are shown in red.

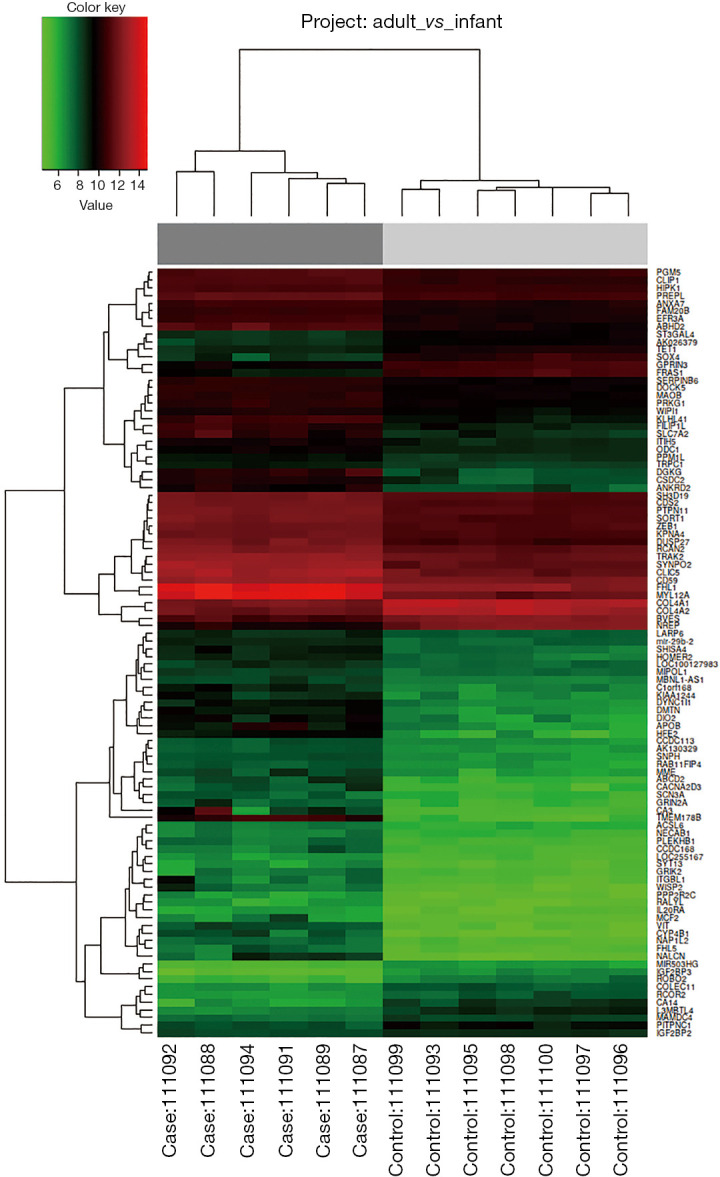

Figure 6.

Hierarchical clustering of the 100 most significantly dysregulated genes. Heatmap classified the samples into two major clusters of upregulated (red colored) and downregulated (green colored) genes according to the condition (“cases/adult” versus “controls/infant” patients) of the samples. By using the heatmap, raw gene expression data were visualized and grouped, based on the similarity of their gene expression pattern. Each column signifies different patient samples, and each row represents a significantly dysregulated gene. The variation in color and intensity of the boxes symbolizes the changes in gene expression, entailing red represents upregulated genes, green represents downregulated genes and black implies unchanged gene expression. The appositional heatmap features the 100 most significant dysregulated genes of the gene expression raw data.

Pathway and gene set enrichment analysis revealed 162 GO terms to be significantly upregulated by the expressed genes. The highly expressed GO terms for cellular components indicated cytoplasmic part and cytoplasm, including contractile fiber as well as contractile fiber part with myofibril, sarcomere, I Band and Z Disc, to be dysregulated in adult patients with CCHD. Additionally, extracellular space, extracellular organelle inclusive of extracellular vesicle and extracellular exosome were highlighted to be involved in dysregulated pathways. Cellular component genes, associated with vesicle, intracellular vesicle, cytoplasmic vesicle, secretory vesicle and secretory granule rank among the most significantly upregulated pathways (Tables S1,S7). Most significant increase of molecular function included protein binding as well as oxidoreductase, catalytic peptidase regulator, peptidase inhibitor activity (Tables S2,S7). Significantly increased biological processes included oxidation reduction process, vesicle mediated transport and secretion by cells, as well es regulation of exocytosis (Tables S3,S7).

A total of 218 GO terms were significantly downregulated in adult compared to infant patients on functional annotation of differentially expressed genes. The most significant GO terms for cellular components included intracellular organelles, chromosome and protein-DNA complexes (Tables S4,S8). Significantly downregulated genes of molecular function were mostly associated with DNA and transcription processes (Tables S5,S8). In line Biological processes involving cell cycling and regulation of gene expression were significantly downregulated (Tables S6,S8).

KEGG analysis showed retinol metabolism (hsa00830) and PPAR signaling pathway (hsa03320) to be significantly upregulated, considering a P value of less than 0.05 (Table S7). Cell cycle (hsa04110), DNA replication (hsa03030) and ribosome (hsa03010) were most significantly downregulated on KEGG analysis, based on a P value of less than 0.05 (Table S8).

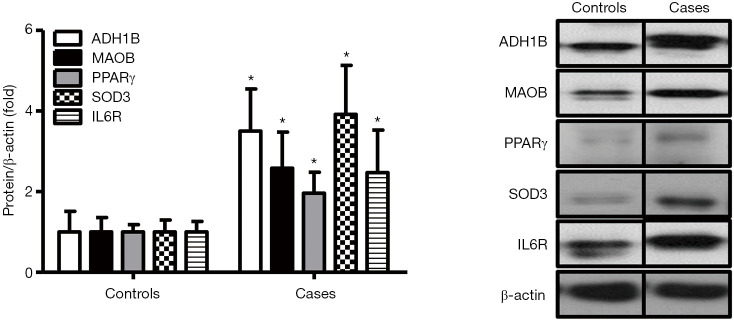

Western blot analyses on proteins extracted from RV tissues were performed for validation of RNA sequencing results. Protein levels of ADH1B, PPAR gamma, MAOB and SOD3 representing critical genes involved in the retinol metabolism, PPAR signaling, and response to oxidative stress pathways, respectively, were significantly increased (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Western blot validation of selected dysregulated target proteins. Total proteins were isolated from the right ventricular myocardium of infant- (“controls”) and adult (“cases”) patients. Western blot analyses were performed using antibodies against alcohol dehydrogenase 1B (ADH1B), monoamine oxidase B (MAOB), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), superoxide dismutase 3 (SOD3), and interleukin 6 receptor (IL6R). β-actin served as a loading control. Representative blots are shown. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used (n=3; *, P<0.05 vs. corresponding control).

Discussion

Differential gene expression and molecular signaling pathways contributing to pathologic myocardial remodeling differ between the left (6,15) and the right ventricle (5,6,15,16). Knowledge about the molecular fundamentals and cellular changes which are involved in the development of RV remodeling secondary to chronic pressure and/or volume overload in CCHD patients is limited (7). The present study evaluated differentially expressed genes of RV tissue from adult patients with TOF and chronic pressure and/or volume overloaded right ventricle compared to infants with TOF by whole transcriptome profiling. Detailed bioinformatic and statistical analysis identified signaling pathways potentially contributing to pathologic RV remodeling in affected patients.

GO Enrichment Analysis and KEGG pathway analysis identified significant dysregulation of genes encoding for structural cellular component and of genes involved in certain biological and functional processes to be significantly dysregulated in RV tissues of adult patients with TOF and chronic hemodynamic RV stressors. Genes associated to the contractile fiber part and actin cytoskeleton of the cell, in particular genes of myofibril, I Band, Z Disc and the contractile units of myocytes, the sarcomere, were particularly upregulated. Increase of contractile protein expression was also described by others in infants with pressure overloaded right ventricles (17). Those findings might explain diastolic RV dysfunction reported by others in patients with TOF (18,19). Analogous findings of alterations in gene expression of cytoskeleton proteins and extracellular matrix proteins were also made in myocardium of failing left ventricles (3,7,15,16). Additionally, upregulation of oxidation-reduction processes was identified as critical biological process involved in RV remodeling of affected patients in the current study. Mechanical pressure is one of the main cardiac stress factors, leading to dysfunctional mitochondria, resulting in increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Dysfunctional mitochondria and imbalance of the redox system contribute to HF (20). Furthermore, upregulation of genes encoding for proteins involved in cell-cell-communication and several molecular pathways, implicating extracellular exosome, extracellular vesicle, vesicle mediated transport and secretory vesicle, were found to be upregulated in adults with RVI in the current study. There is evidence that ROS can stimulate the production of exosomes and affect the molecular content of exosomes, among various other external stimulation factors, of which are some still unknown (21,22). Exosomes are extracellular 40 to 150 nm diameter lipid vesicles secreted by cells (22,23) to facilitate intercellular communication by transferring miRNA, mRNA and proteins between cells (24). It is hypothesized that exosomes might play a role in cardiac remodeling in the response to cardiac stress by influencing inflammation, interstitial fibrosis, ventricular hypertrophy and changes in contractility (22). Due to the unique function of exosomes to promote intercellular communication, they are currently of interest as therapeutic agents and potential biomarkers for various diseases, including cardiovascular diseases (25,26).

The current study also showed the upregulation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling pathway. PPARs play a role as nuclear receptor transcription factors, activated by specific ligands such as long chain fatty acids (27). The expression of genes, regulated by the three PPAR isoforms, contribute to cardiac metabolic processes, in particular lipid, fatty acid and glucose homeostasis, cell differentiation and control of inflammation (27-30). Upregulation of the PPAR signaling pathway in the current study is consistent to results of previous studies which report dysregulated PPAR signaling pathway in the context of cardiac remodeling, myocardial hypertrophy and HF (27,31-33). PPARs regulate gene expression by forming a nuclear heterodimeric complex with retinoid X receptor (RXR) and binding to specific promoter regions of the target genes to be regulated (29,30). RXR is one of the major genes involved in retinol metabolism. In line with this, KEGG bioinformatical analysis revealed a highly significant involvement of the retinol pathway in RV tissues of affected patients. In addition to RXR (P value 0.0051), genes such as RDH10 (P value 0.00076), ADH1B (P value 4.93E-11), ADH1C (P value 0.00037) and CYP1A1 (P value 1.01E-05) were significantly upregulated. Activation of retinoic acid signaling in left ventricular tissue in conjunction with myocardial ischemia and remodeling after myocardial infarction in mice was reported by others (34). The retinol metabolism utilizes vitamin A and its derivates to ensure cardiac supply of various forms of all trans retinoic acids (atRA) (34). AtRA function as ligands via binding to nuclear receptors like RAR or RXR (34). The receptors form heterodimers and bind to DNA regulatory sequences, whereby regulating the frequency of gene expression, plus modifying interconnection with other signaling pathways (34). The results of the current study concur with previous studies, investigating dysregulation of retinol metabolism in ventricular remodeling and HF. We speculate that not only the left ventricle, but also the right ventricle shows a dysregulation of retinol metabolism in the development of RVI, which is also supported by our results. The activation of metabolites of retinol metabolism may play a previously unimagined role in RV remodeling and in response to cardiac damage and repair. The simultaneous overexpression of genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, PPAR signaling pathway as well as retinol metabolism indicate the interdependence of the individual signaling pathways (31) and promote the presumption of contributing to RV remodeling in stages of RVI in adult patients with CCHD.

During the development of RV remodeling and RVI, RNA sequencing revealed a marked adjustment of gene expression, regarding mitotic cell cycle, cell division and DNA replication. Downregulation of differentially expressed genes, associated with DNA binding transcription factor activity, transcription regulator activity as well as RNA polymerase 2 transcription factor activity, support the assumption of decreased cell cycling in stressed RV myocardium of adult patients with signs of RVI. In line with above findings, reduction of gene expression with respect to nucleus, chromosome, protein-DNA complex, spindle and replication fork strengthen suspicion of declined cell proliferation and cell maintenance in cardiac remodeling. Downregulation of cell cycle leads to a fatal lack of myocardial regeneration, due to failing proliferation of normal functioning cardiomyocytes (35). Experimental research determined cardiac loss of ability to reentry cell cycle, since differentiated cells such as adult cardiomyocytes typically become post-mitotic and exit the cell cycle postnatal (36,37). The present study indicates that stressed myocardium retains the incapability to re-enter cell cycle in patients with CCHD and RVI, facing adverse cardiac remodeling. Cardiac tissue consequently encounters difficulties in adaption to pathologic conditions such as pressure and volume overload, which results in impaired cardiac injury repair and hypertrophy, leading to increased risk of cardiac morbidity and mortality (38,39). The incapacity to enter cell cycle, guaranteeing cell proliferation, injury regeneration and preservation of ventricular function, aggravate pathophysiologic conditions and encourage development of RV remodeling and RVI.

The major limitation of the current study is the lack of whole transcriptome profile of RV tissue gained from healthy patients without structural heart disease and without myocardial disease state as a control group. The use of a donor heart, which is discarded for organ transplantation, would have provided an opportunity to remove healthy tissue from the right ventricle and use it as a reference material. Nevertheless, it must be noted, that not-transplantable donor hearts are often not completely healthy with exposition to abundant factors, typically changing gene expression. Besides, the rejection of a donor heart is a rarity. Also, the falsification of the results of gene sequencing by temporal issue and processing complications should also not be underestimated. Because of altered myocardial gene expression after organ ischemia and organ processing outside the body it is not ideal to use not-transplantable donor hearts as healthy reference tissue (40). The focus of the current study was therefore the alteration of gene expression patterns contributing to RV remodeling in chronic volume and/or pressure overloaded RVs over lifetime in a cohort of CCHD patients with similar structural heart disease, namely TOF. The control group consistent of infants TOF where RV tissue was collected at the time of surgical repair at the age of 4–5 months. Limited data of developmentally regulated genes in myocardial tissue, showing a switch during aging process, hamper the identification and exclusion of all genes, being essential in heart development during early childhood. By comparing most significant single-cell RNA sequencing results of murine cells to our results, genes associated with cardiac development were identified and excluded for further interpretation. However, according to few studies there are indications that genes play a variety of roles in both heart development and pathological cardiac remodeling (41). It has also been described that embryonic patterns and fetal gene programs, which are crucial for heart development and maturation, get reactivated in pathological conditions, leading to HF and death (42). Studies have shown that members of the myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) family are expressed in both embryonic cardiac tissue and postnatal hypertrophic cardiac remodeling (43). MEF2 proteins such as MEF2C function as transcription factors, increasing expression of certain fetal and cardiac genes, including natriuretic peptide A (NPPA), skeletal alpha actin (ACTA1), desmin (DES) and dystrophin (DMD). Concomitant to previous observations expression ofMEF2C, NPPA, ACTA1, DES and DMD were found to be upregulated in our study, reinforcing the suggestion of reactivation of fetal gene programs in pathological heart conditions (Table S10). Considering these emerging evidences, important information of gene expression changes during cardiac remodeling might get missed by excluding alleged developmentally regulated genes. Another limitation is the unequal distribution of female and male patients in the infant and adult patient group. While the infant patient group is dominated by males (6/7), the adult patient group is composed of more females (5/6). The gender disparity might have an impact on gender specific alterations in gene expression, which makes transferability more difficult. However, whereas there are contradictory data regarding gender differences in gene expression of the left ventricular myocardium in human (44) and animal (45) studies, to our knowledge the impact of gender on mRNA expression in human RV heart tissue has not been described so far in the literature. Two of the six adult patients were on cardiac medication at the time of study. The influence of this on gene expression in unknown and due to small sample size, we were not able to focus on this in the current analysis. Lastly, as this is a single-center study with retrospective data analysis, the results cannot simply be generalized and extrapolated to other centers.

Conclusions

There is altered RV gene expression over lifetime in adult patients with RVI due to long-term sequelae of CCHD. Analysis of different gene expression profiles identified molecular pathways involved in cell-cell communication, exosomes, extracellular vesicles, oxidation reduction process, contractile fiber and retinol metabolism to be involved in pathologic RV remodeling secondary to chronic volume and/or pressure overload. The identification of molecular pathways leading to pathological RV remodeling and failure is crucial for the development of new therapies and upcoming biomarkers, screening assays for risk stratification and disease monitoring. The current study contributes to a better understanding of the molecular characterization of RV remodeling and RVI, which significantly increases morbidity and mortality in patients with CCHD, surviving into adulthood.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by the German Centre for Cardiovascular Research (Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung e. V., DZHK) Excellence Program Rotation Grant (Cordula Maria Wolf), Berlin, Germany.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethics committee (approval 10/16/2017, number 242/17S, and approval 01/11/2017, number 592,16S) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was taken from all patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Footnotes

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Yskert von Kodolitsch, Harald Kaemmerer, Koichiro Niwa) for the series “Current Management Aspects in Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD): Part IV” published in Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-894

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-894

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-894

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/cdt-20-894). The series “Current Management Aspects in Adult Congenital Heart Disease (ACHD): Part IV” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Warnes CA, Liberthson R, Danielson GK, et al. Task force 1: the changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1170-5. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01272-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazor Dray E, Marelli AJ. Adult Congenital Heart Disease: Scope of the Problem. Cardiol Clin 2015;33:503-12, vii. 10.1016/j.ccl.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy S, Bernstein D. Molecular Mechanisms of Right Ventricular Failure. Circulation 2015;132:1734-42. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dinardo JA. Heart failure associated with adult congenital heart disease. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2013;17:44-54. 10.1177/1089253212469841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy S, Zhao M, Hu DQ, et al. Physiologic and molecular characterization of a murine model of right ventricular volume overload. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013;304:H1314-27. 10.1152/ajpheart.00776.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams JL, Cavus O, Loccoh EC, et al. Defining the molecular signatures of human right heart failure. Life Sci 2018;196:118-26. 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy S, Bernstein D. The vulnerable right ventricle. Curr Opin Pediatr 2015;27:563-8. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NM, et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J 2010;31: 2915-57. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehra MR, Park MH, Landzberg MJ, et al. Right heart failure: toward a common language. Pulm Circ 2013;3:963-7. 10.1086/674750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstam MA, Kiernan MS, Bernstein D, et al. Evaluation and Management of Right-Sided Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e578-e622. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kračun D, Riess F, Kanchev I, et al. The beta3-integrin binding protein beta3-endonexin is a novel negative regulator of hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014;20:1964-76. 10.1089/ars.2013.5286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeLaughter DM, Bick AG, Wakimoto H, et al. Single-Cell Resolution of Temporal Gene Expression during Heart Development. Dev Cell 2016;39:480-90. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:685-713; quiz 86-8. 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wald RM, Redington AN, Pereira A, et al. Refining the assessment of pulmonary regurgitation in adults after tetralogy of Fallot repair: should we be measuring regurgitant fraction or regurgitant volume? Eur Heart J 2009;30:356-61. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urashima T, Zhao M, Wagner R, et al. Molecular and physiological characterization of RV remodeling in a murine model of pulmonary stenosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008;295:H1351-H1368. 10.1152/ajpheart.91526.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan FL, Moravec CS, Li J, et al. The gene expression fingerprint of human heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002;99:11387-92. 10.1073/pnas.162370099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bond AR, Iacobazzi D, Abdul-Ghani S, et al. Changes in contractile protein expression are linked to ventricular stiffness in infants with pulmonary hypertension or right ventricular hypertrophy due to congenital heart disease. Open Heart 2018;5:e000716. 10.1136/openhrt-2017-000716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaturvedi RR, Shore DF, Lincoln C, et al. Acute right ventricular restrictive physiology after repair of tetralogy of Fallot: association with myocardial injury and oxidative stress. Circulation 1999;100:1540-7. 10.1161/01.CIR.100.14.1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatzoulis MA, Clark AL, Cullen S, et al. Right ventricular diastolic function 15 to 35 years after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Restrictive physiology predicts superior exercise performance. Circulation 1995;91:1775-81. 10.1161/01.CIR.91.6.1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palaniyandi SS, Qi X, Yogalingam G, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial processes: a target for heart failure. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech 2010;7:e95-e102. 10.1016/j.ddmec.2010.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik ZA, Kott KS, Poe AJ, et al. Cardiac myocyte exosomes: stability, HSP60, and proteomics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013;304:H954-65. 10.1152/ajpheart.00835.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cervio E, Barile L, Moccetti T, et al. Exosomes for Intramyocardial Intercellular Communication. Stem Cells Int 2015;2015:482171. 10.1155/2015/482171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathivanan S, Ji H, Simpson RJ. Exosomes: extracellular organelles important in intercellular communication. J Proteomics 2010;73: 1907-20. 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yellon DM, Davidson SM. Exosomes: nanoparticles involved in cardioprotection? Circ Res 2014;114:325-32. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Février B, Raposo G. Exosomes: endosomal-derived vesicles shipping extracellular messages. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2004;16:415-21. 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sluijter JP, Verhage V, Deddens JC, et al. Microvesicles and exosomes for intracardiac communication. Cardiovasc Res 2014;102:302-11. 10.1093/cvr/cvu022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finck BN. The PPAR regulatory system in cardiac physiology and disease. Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:269-77. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osorio JC, Stanley WC, Linke A, et al. Impaired myocardial fatty acid oxidation and reduced protein expression of retinoid X receptor-alpha in pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation 2002;106:606-12. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000023531.22727.C1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren JS, Oka SI, Zablocki D, et al. Metabolic reprogramming via PPARalpha signaling in cardiac hypertrophy and failure: From metabolomics to epigenetics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2017;313:H584-H596. 10.1152/ajpheart.00103.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmadian M, Suh JM, Hah N, et al. PPARgamma signaling and metabolism: the good, the bad and the future. Nat Med 2013;19:557-66. 10.1038/nm.3159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Bilsen M, Smeets PJ, Gilde AJ, et al. Metabolic remodelling of the failing heart: the cardiac burn-out syndrome? Cardiovasc Res 2004;61:218-26. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asakawa M, Takano H, Nagai T, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma plays a critical role in inhibition of cardiac hypertrophy in vitro and in vivo. Circulation 2002;105:1240-6. 10.1161/hc1002.105225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilde AJ, van der Lee KA, Willemsen PH, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and PPARbeta/delta, but not PPARgamma, modulate the expression of genes involved in cardiac lipid metabolism. Circ Res 2003;92:518-24. 10.1161/01.RES.0000060700.55247.7C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilbija D, Haugen F, Sagave J, et al. Retinoic acid signalling is activated in the postischemic heart and may influence remodelling. PLoS One 2012;7:e44740. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohamed TMA, Ang YS, Radzinsky E, et al. Regulation of Cell Cycle to Stimulate Adult Cardiomyocyte Proliferation and Cardiac Regeneration. Cell 2018;173:104-116.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bicknell KA, Coxon CH, Brooks G. Can the cardiomyocyte cell cycle be reprogrammed? J Mol Cell Cardiol 2007;42:706-21. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahuja P, Sdek P, MacLellan WR. Cardiac myocyte cell cycle control in development, disease, and regeneration. Physiol Rev 2007;87:521-44. 10.1152/physrev.00032.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woo YJ, Panlilio CM, Cheng RK, et al. Therapeutic delivery of cyclin A2 induces myocardial regeneration and enhances cardiac function in ischemic heart failure. Circulation 2006;114:I206-13. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valente AM, Gauvreau K, Assenza GE, et al. Contemporary predictors of death and sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot enrolled in the INDICATOR cohort. Heart 2014;100:247-53. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowes BD, Minobe W, Abraham WT, et al. Changes in gene expression in the intact human heart. Downregulation of alpha-myosin heavy chain in hypertrophied, failing ventricular myocardium. J Clin Invest 1997;100:2315-24. 10.1172/JCI119770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu S, Nie J, Luan Q, et al. Phosphorylation of the Twist1-family basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors is involved in pathological cardiac remodeling. PLoS One 2011;6:e19251. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verma SK, Deshmukh V, Liu P, et al. Reactivation of fetal splicing programs in diabetic hearts is mediated by protein kinase C signaling. J Biol Chem 2013;288:35372-86. 10.1074/jbc.M113.507426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dirkx E, da Costa Martins PA, De Windt LJ. Regulation of fetal gene expression in heart failure. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013;1832:2414-24. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ambrosi CM, Yamada KA, Nerbonne JM, et al. Gender differences in electrophysiological gene expression in failing and non-failing human hearts. PLoS One 2013;8:e54635. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weinberg EO, Thienelt CD, Katz SE, et al. Gender differences in molecular remodeling in pressure overload hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:264-73. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00165-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]