Abstract

Electrochemical hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) refers to the process of generating hydrogen by splitting water molecules with applied external voltage on the active catalysts. HER reaction in the acidic medium can be studied by different mechanisms such as Volmer reaction (adsorption), Heyrovsky reaction (electrochemical desorption) or Tafel reaction (recombination). In this paper, facile hydrothermal methods are utilized to synthesis a high-performance metal-inorganic composite electrocatalyst, consisting of platinum nanoparticles (Pt) and molybdenum disulfide nanosheets (MoS2) with different platinum loading. The as-synthesized composite is further used as an electrocatalyst for HER. The as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90-modified glassy carbon electrode shows the best electrocatalytic performance than pure MoS2 nanosheets. It exhibits Pt-like performance with the lowest Tafel slope of 41 mV dec−1 and superior electrocatalytic stability in an acidic medium. According to this, the HER mechanism is related to the Volmer-Heyrovsky mechanism, where hydrogen adsorption and desorption occur in the two-step process. According to electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis, the presence of Pt nanoparticles enhanced the HER performance of the MoS2 nanosheets because of the increased number of charge carriers transport.

Keywords: Platinum nanoparticles, Molybdenum disulfide, Electrocatalyst, Hydrogen evolution reaction, Acidic medium

Introduction

Various environmental issues are the results of global activities and the consumption of fossil fuels. Therefore, there have been challenges to figure out sustainable, clean, and eco-friendly fuels to overcome this problem. An inspiring alternative energy carrier to replace fossil fuels is hydrogen (H2) which is clean and free from CO2 emission. Therefore, it is of great interest to produce H2 from renewable resources such as water [1–4]. Hydrogen could be obtained from the splitting of water, an energy-intensive process that requires 237 kJ/mol. Electrolytic water splitting is a process where an electrical current dissociates water into oxygen and hydrogen. This process entails substantial effort in discovering breakthrough electrolytes and electrodes that are low cost, efficient, long-lasting, and stable. Hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is an excellent route to produce high purity (≈ 100%) hydrogen from water electrolysis [5, 6]. Therefore, an ideal catalyst must have high stability and be present to start proton reduction with minimum over potential and large cathodic current densities, which leads to enhancing the HER efficiency [7–10].

So far, the most effective HER electrocatalysts reported are Platinum (Pt) and its alloy because of rapid reduction kinetics, low overpotential, and small onset potential for high-efficiency energy conversion [11, 12] However, it is not adequate to use a large amount of Pt due to its low availability and high price as an electrocatalyst [13]. On the other hand, it can significantly enhance Pt electrocatalyst activity by reducing the size and increasing the surface area, allowing more atoms at the exterior and subsurface site to be involved in the catalytic process [14]. Therefore, control of Pt size and avoiding its agglomeration are favourable strategies to enance its electrocatalytic activity [15]. Consequently, it is very effective to deposit Pt nanoparticles with high homogeneity on the supporting materials such as conductive polymers, carbon, metal oxide, and sulfide[16] The supporting materials typically provide accessibility and stabilization platforms for nanoparticle growth and bring about modified reactivity and additional adsorption and active sites [17] Therefore, the decoration of Pt nanostructures such as nanostructure on supporting materials not only enhances the physiochemical properties of supporting materials but also prevents agglomeration of Pt, which influences the activity of composite towards HER [18–21]. Newly, earth plentiful source, high efficiency, and affordable transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) are considered good alternatives for HER. Synthesizing TMD nanomaterials as HER electrocatalysts requires considerable effort due to their noteworthy characteristics such as excellent electrochemical, optical, mechanical properties. They have low overpotential, small Tafel slope, and high air stability which exhibit high HER performance. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) and tungsten disulfide (WS2) are two materials among the TMDs group, which have electrical properties that can be altered from metallic to semiconducting by varying their crystal structure and the number of layers. MoS2 is one of the well-known and most widely investigated semiconductors which is an eco-friendly, non-toxic, and abundant semiconductor with an atomic-thickness layer structure similar to graphene [22–25]. HER performance of bulk MoS2 was investigated by J.C.Bennett et al. in 1977 and found that its activity is low, as evidenced by a large Tafel slope of 692 mV/dec and a high onset potential of about − 0.09 V versus HER. MoS2 nanoparticles were reported as HER active species by Hinnemann et al. in 2005. Afterward, MoS2 has taken back popularity, and a slew of new techniques have arisen to improve its HER electrocatalytic performance.[26]. According to the recent work, the HER activity of MoS2 is highly related to the exposed edges, while due to its semiconductive nature, it has poor conductivity [27]. To solve this problem, designing a novel composite based on MoS2 with the high exposed active sites and enhancing its conductivity is the key to elevating the properties of MoS2-based electrocatalysts for HER [2, 28] Moreover, MoS2 nanosheets possess good electrochemical stability and high surface area. They also function as effective support materials to efficiently decorate highly catalytic active species such as Pt nanoparticle to attain HER catalytic activity [29]

Herein, we successfully demonstrate a productive and straightforward hydrothermal method for synthesizing MoS2 nanosheets supported Pt nanoparticles (Pt/Mo). The as-synthesized Pt/Mo composites with different Pt loading were used as electrocatalyst for HER. Optimization of Pt loading on the surface of MoS2 nanosheet is an attempt to understand the effect of Pt loading on the electrocatalytic activity of MoS2 nanosheet in HER. This technique decreases Pt consumption in the composite because MoS2 nanosheets compensate Pt effects in the composite, which is a more affordable way in the hydrogen production economy.

Experimental Methods

Chemical Reagent

All chemicals that were used in this experiment, such as Chloroplatinic acid solution (H2PtCl6), Thioacetamide powder (C2H5NS), Ammonium heptamolybdate powder ((NH4)6Mo7O24) and Sulfuric acid solution (H2SO4) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Synthesis of MoS2 Nanosheets

Hydrothermal treatment was performed to synthesize MoS2 nanosheet, in which 188 mg of C2H5NS and 309 mg of (NH4)6Mo7O24 were taken and completely dissolved for an hour in 45 ml of distilled water. Later this colourless mixture was transferred into a stainless 45 ml Teflon-lined autoclave and kept at 180 °C for 18 h. After that, the black powder MoS2 was centrifuged and washed with distilled water three times. The final black powder product dried at 65 °C for a day.

Synthesis of Pt/Mo Composites

In a typical process, 50 mg of MoS2 nanosheets were dispersed in 25 ml of deionized water under sonication for 30 min to get homogenous dispersion. Then, 60 μL of H2PtCl6 (8% in H2O) solution was dissolved in 20 ml of distilled water, and then the solution was added drop wisely to the MoS2 dispersion under sonication for an hour. The final mixture was heated at 70 ºC for 4 h. The as-synthesized Pt/Mo-x composites with x = 60, 90, and 120 μL of H2PtCl6 were referred to as Pt/Mo-60, Pt/Mo-90, and Pt/Mo-120 with 1.17 × 10–2 gr, 1.75 × 10–2 gr, and 2.34 × 10–2 gr Pt loading, respectively. The same procedure was done in the previous section for washing and drying Pt/Mo composite with different Pt loading.

Physical and Chemical Characterization

The physical characterization of the material, such as crystal structure, size, and morphology, was studied by an X-ray diffractometer (XRD Smart Lab Guidance, Rigaku) and a High-resolution transmission electron microscope (HR-TEM Techno, FEI). Prior to drop-casting on the copper grid, the dilute and homogenous dispersion was prepared in DI water under sonication. The chemical analysis of the material, such as elemental composition and oxidation states, was conducted by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS Model 1257, Perkin Elmer) and Raman (HR800 JY, Lab RAM HR) spectroscopy. The electrochemical measurements were carried out by galvanostat/potentiostat (Autolab PSTAGT50).

Electrode Fabrication

Preparation of the electrode for electrochemical measurement was carried out by the drop casting method. Briefly, 5 mg of the different electrocatalysts was sonicated in 5 ml of distilling water for 30 min. Same methode was done to prepare solution of 20 wt% Pt/C for electrochemical mesearment. The working electrode utilized in this system is a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Then, five μL of homogenous dispersion was drop casted on the surface of the clean GCE. The electrodes stayed at room temperature for complete dryness.

Electrochemical Measurement

Electrochemical measurement was performed in the solution of 0.5 M H2SO4. Briefly, 15 ml of the 0.5 M H2SO4 solution was used as the electrolyte in the three-electrode cell. The electrocatalytic HER activities of pure MoS2, Pt/Mo-x composites with different Pt loading (x = 60, 90, 120), and commercial Pt (Pt/C) were studied in the 0.5 M H2SO4 solution by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) techniques using a three-electrode cell. The as-synthesized samples-modified GCE was used as the working electrode. The reference and counter electrodes were chosen to be an Ag/AgCl electrode and a graphite rod, respectively. The polarization curves were obtained by sweeping the potential from 0.1 to − 0.6 V υs RHE at a potential sweep rate of 20 mV/s.

Results and Discussion

Structural and Morphological Analysis

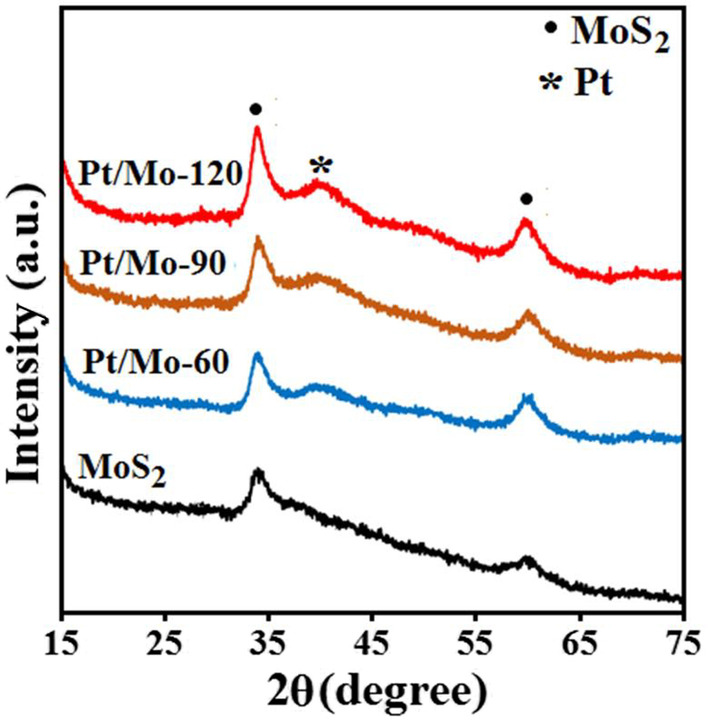

X-ray diffractograms of the pure MoS2 nanosheets and Pt/Mo-x composites with three different Pt loading (x = 60, 90, 120) are shown in Fig. 1. The two peaks at 2θ values of 33.791° and 59.471° are indexed to the (100) and (106) planes, respectively (JCPDS Card No. 98–002-4000), of the hexagonal structure of MoS2 (2H phase) with lattice constants of a = 3.15 Å, b = 3.15 Å and c = 12.3 Å [22] However, compared with the pure MoS2 nanosheets, the X-ray diffractograms of the Pt/Mo-x composites with three different Pt loading exhibits an additional (111) peak at 2θ = 39.57° can be assigned to the (111) diffraction of cubic platinum (JCPDS card no. 00-004-0802) with the lattice constant a = b = 3.923 Å [29]. In addition, no other peaks were observed apart from the peaks of MoS2 and Pt, indicating a high phase purity of the Pt/Mo-x composites. Notably, the XRD results of Pt/Mo-x composites with three different Pt loading demonstrates that as Pt loading content in composite increases, the intensity of the peak at 2θ = 39.57° increases.

Fig.1.

X-ray diffraction patterns of pure MoS2 nanosheets and Pt/Mo-x (x = 60, 90, 120) composites

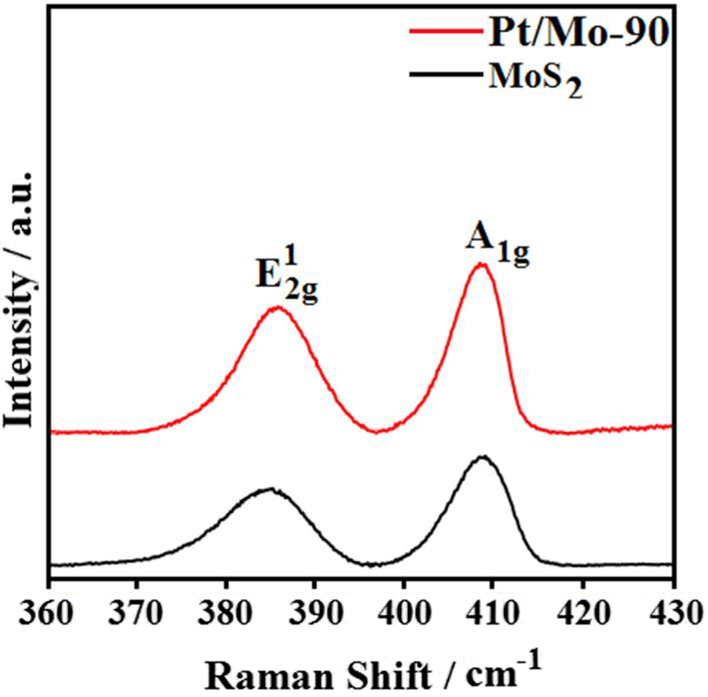

Raman spectroscopy technique is an efficient non-destructive chemical analysis to investigate the structural properties and the details of the thickness of MoS2 nanosheets. Figure 2 shows the Raman spectra of pure MoS2 nanosheets and Pt/Mo-90 composite, obtained over the range of 360–430 cm−1, where two longitudinal peaks of pure MoS2 at 384 cm−1 and 407 cm−1 are assigned to the and A1g modes. The former one could be attributed to the planar vibrations between S and Mo atom, while the latter one illustrates the vibration of sulfides in the out-of-plane direction [22]. Based on the peak position difference between and A1g modes which were calculated to be 23 cm−1, the MoS2 nanosheets were determined to be tri-layers [30] On the other hand, the Raman spectra of Pt/Mo-90 shows similar spectra compared to blank MoS2, but only an increase in peak intensity and slight red shift of both the and A1g peaks were observed in the Raman spectrum of Pt/Mo-90, implying a successful formation of the composite with the decoration of Pt nanoparticles on the surface of MoS2 nanosheets [31]. Noted, the slight red shift of phonon modes may be assigned to the heating of the composite during the Pt decoration [31].

Fig. 2.

The Raman spectra of pure MoS2 nanosheets and Pt/Mo-90 composite

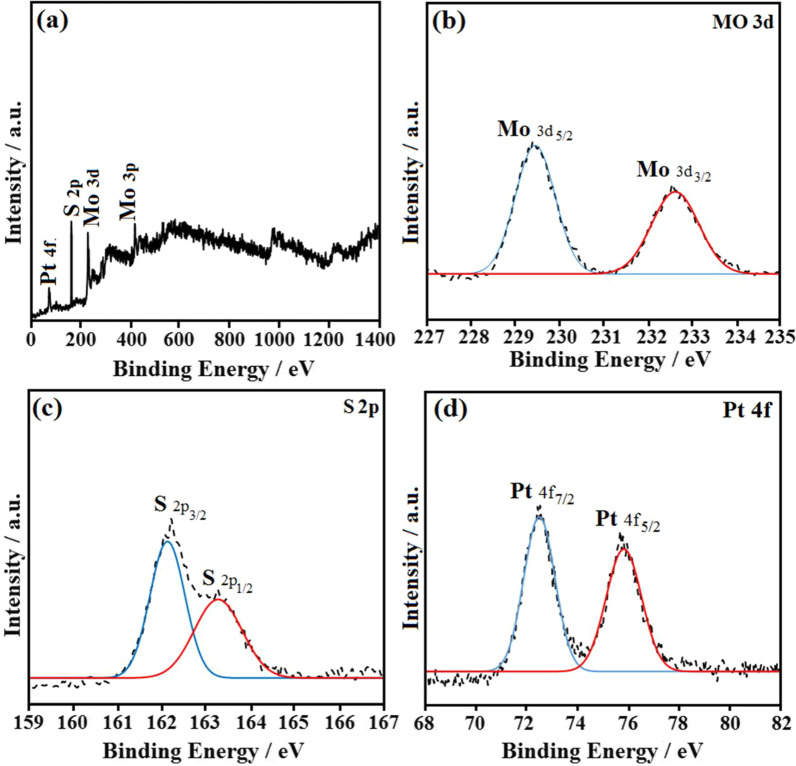

The XPS analysis was performed to investigate the surface atom electronic structure of the Pt/Mo composite (Fig. 3). From the wide scan XPS spectrum of Pt/Mo-90 composite, the elements of sulfur (S), molybdenum (Mo), and Platinum (Pt) can be determined. As shown in Fig. 3a, four peaks obviously observed in the XPS survey spectrum of Pt/Mo-90 composite at 74.2 eV (Pt 4f), 162.4 eV (S 2p), 229.6 eV (Mo 3d), and 408.9 eV (Mo 3p). The atomic ratio value of S 2p: Mo 3d is estimated at 2.04, which reveals a successful hydrothermal process that leads to the formation of the MoS2 nanosheets [32]

Fig. 3.

Wide scan XPS spectra of a Pt/Mo-90 composite; The high-resolution XPS spectra of b Mo 3d, c S 2p, and d Pt 4f of Pt/Mo-90 composite

The XPS spectrum corresponding to that of Mo 3d of the Pt/Mo-90 composite shows two strong peaks at 229.4 and 232.5 eV, which are referred to as the Mo 3d5/2 and Mo 3d3/2 doublet, respectively (Fig. 3b) [33]. Notably, the XPS spectra of Mo 3d clearly confirmed the existence of Mo (IV) in the MoS2 structure due to of presence of these two different strong peaks. The S 2p component of Pt/Mo-90 composite, which suggests S binding, exhibits two binding energies at 162.1 eV and 163.3 eV corresponding to the S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 in MoS2 structure (Fig. 3c) [33]. Besides, in the spectrum of Pt 4f of Pt/Mo-90 composite, two peaks were observed at 72.6 eV and 65.8 eV which are related to the Pt 4f7/2 and Pt 4f 5/2, respectively (Fig. 3d) [34].

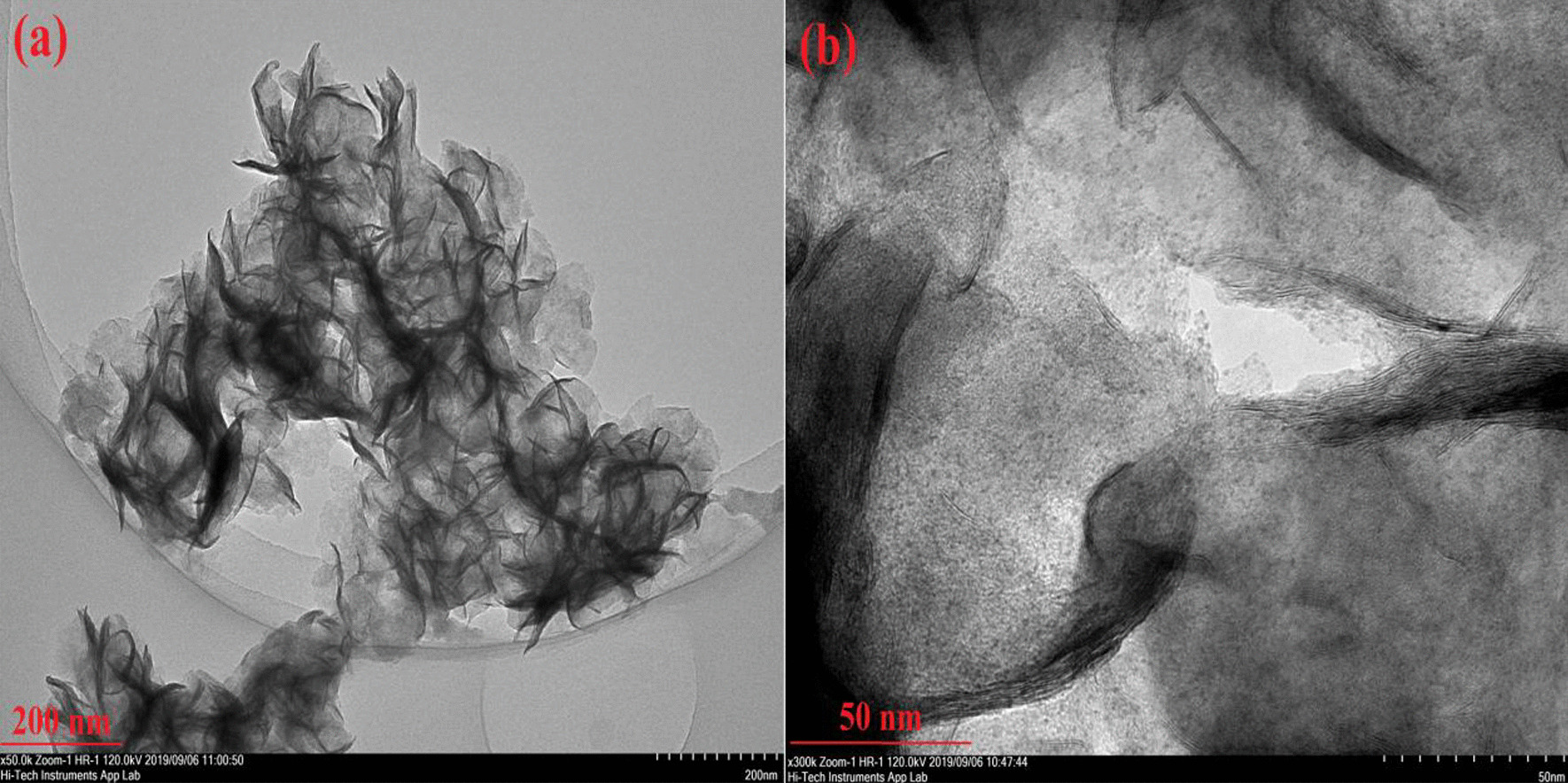

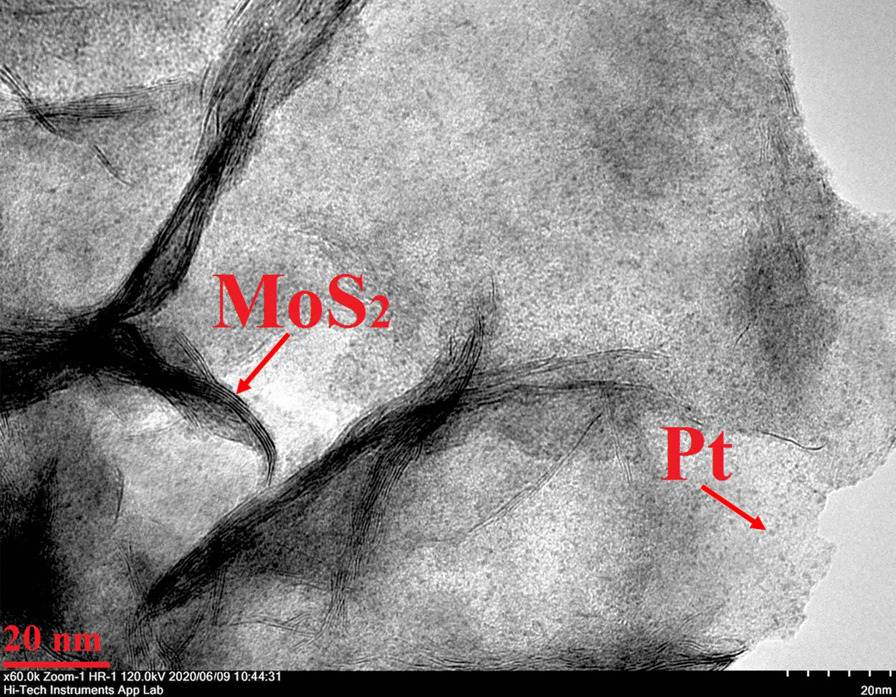

The morphology of the as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90 composite was carried out by TEM analysis (Fig. 4 and 5). Figure 4a represents the TEM image of the as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90. The average diameter of the as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90 was obtained 1 μm, and the surface structure of the nanosheet is wrinkle shape. According to Fig. 4b, in Pt/Mo-90 the Pt nanoparticles have grown uniformly on the surface of MoS2 nanosheet.

Fig. 4.

a, b TEM image of Pt/Mo-90 composite

Fig. 5.

High magnification TEM image of Pt/Mo-90 composite

Figure 5 shows the high-resolution TEM image of Pt/Mo-90 composite in which Pt nanoparticles are successfully decorated on the surface of the MoS2 nanosheet having an average size of 2 nm. Notably, Fig. 5 confirmed that some of the Pt nanoparticles being also located between the crumpled MoS2 nanosheets.

Catalytic Performance for HER

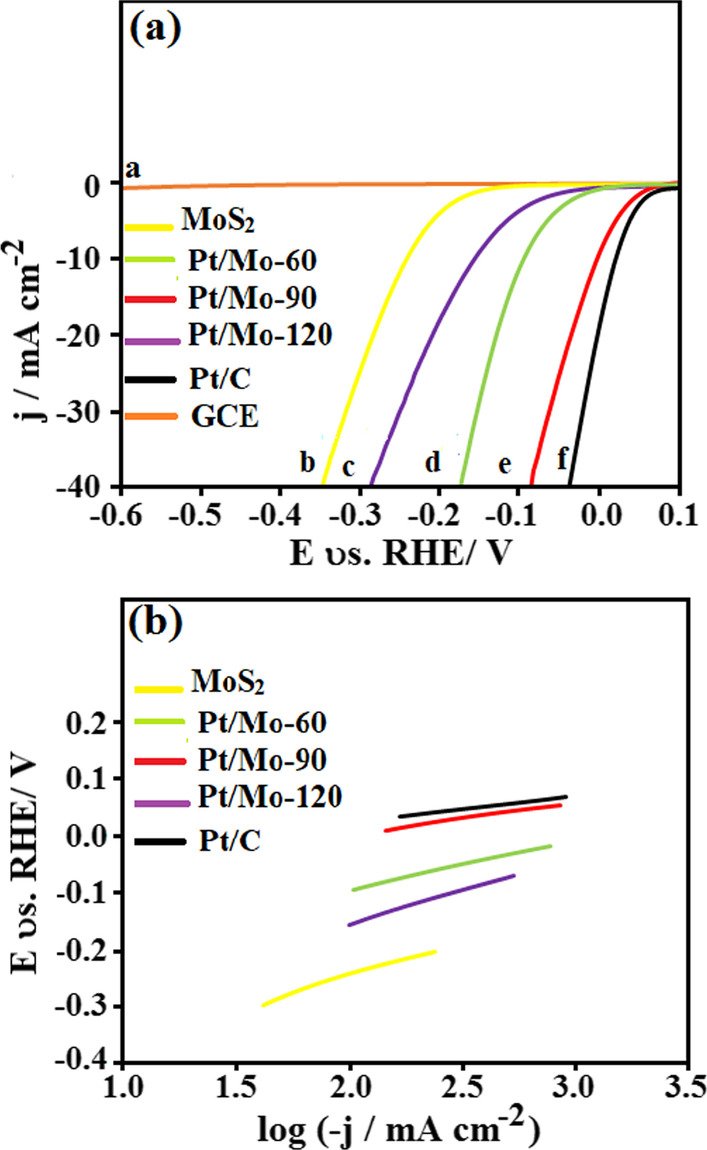

To obtain knowledge about the effect of Pt loading on HER electrocatalytic performance of MoS2 nanosheet, the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was performed in N2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 using a three-electrode electrochemical cell. Figure 6a shows the polarization curves of different electrocatalysts such as bare GCE, pure MoS2 nanosheets, Pt/Mo-x (x = 60, 90, 120), and 20 wt.% Pt/C-modified GCE at the scan rate of 20 mV s−1. There is not any HER activity observed from the bare GCE; hence the effect of GCE is neglected.

Fig. 6.

a LSV curves of a bare GCE, b Pure MoS2 nanosheets, c Pt/Mo-120, d Pt/Mo-60, e Pt/Mo-90 composite, and f Pt/C; b Tafel plot of different electrocatalyst

According to Fig. 6a, the presence of Pt nanoparticles causes in enhancing of the onset potential, half-wave potential, and overpotential of MoS2 nanosheets. However, with the increase of the Pt loading up to 90 μl, the LSV curve initially enhances for Pt/Mo-90, but further increase in Pt loading up to 120 μl leads to worsening of the LSV curve. Based on the LSV curve, at a current density of − 10 mA cm−2, the pure MoS2 nanosheets, Pt/Mo-120, and Pt/Mo-60 composites exhibit onset potential of − 0.15, − 0.03, and − 0.01 V, respectively, while Pt/Mo-90 and Pt/C show a remarkable onset potential of + 0.05 and + 0.07 V, respectively. Another prominent factor in HER activity is the half-wave potential (the potential where the current is half of the limiting current). According to Fig. 6a, the half-wave potential of Pt/Mo-x (x = 60, 90, 120) composite electrodes showed a more positive potential compared with pure MoS2 nanosheets because of the presence of Pt nanoparticles in composites. Moreover, the Pt/Mo-90-modified GCE at the current density of − 10 mA cm−2 showed a lower overpotential of − 0.01 V, comparing with the pure MoS2-modified GCE (− 0.24 V), Pt/Mo-120-modified GCE (− 0.16 V), and Pt/Mo-60-modified GCE (− 0.09 V), respectively. Notably, the overpotential value of Pt/Mo-90 (− 0.01 V) was very near to that of 20 wt.% Pt/C (+ 0.01 V), showing that the composite electrocatalyst had Pt-like electrocatalytic activity.

The Tafel plot is another important metric in HER. It is utilised to investigate the kinetics of the materials' HER electrocatalytic activity. Figure 6b exhibits the Tafel plots of the different electrocatalysts. As observed, among all electrocatalyst composites, Pt/Mo-90-modified GCE exhibited the smallest Tafel slope of 41 mV dec−1, which is very near to the commercial of 20 wt.% Pt/C (37 mV dec−1). Pt/Mo-60 (75 mV dec−1) and Pt/Mo-120 (112 mV dec−1) showed larger Tafel slop comparing to Pt/Mo-90 while lower than pure MoS2 nanosheet (126 mV dec−1). According to the earlier works, HER reaction in the acidic medium can be studied by three different mechanisms. Volmer reaction is the first one, in which the source of the proton is the hydronium ion (H3O+) for the primary discharge step [35]:

| 1 |

Based on the above formula, b is the Tafel slope, F is the Faraday constant, R is the ideal gas constant, α is the symmetry factor ( ≈ 0.5), and T is the temperature. Heyrovsky reaction (Electrochemical desorption) or Tafel reaction (recombination) will occur in the following steps as shown by Eq. 2 and 3, respectively.

| 2 |

| 3 |

According to the as-calculated Tafel slope of Pt/Mo-90 composite (41 mV dec−1), the HER mechanism is related to the Volmer-Heyrovsky mechanism, where hydrogen adsorption and desorption occur in the two-step process.

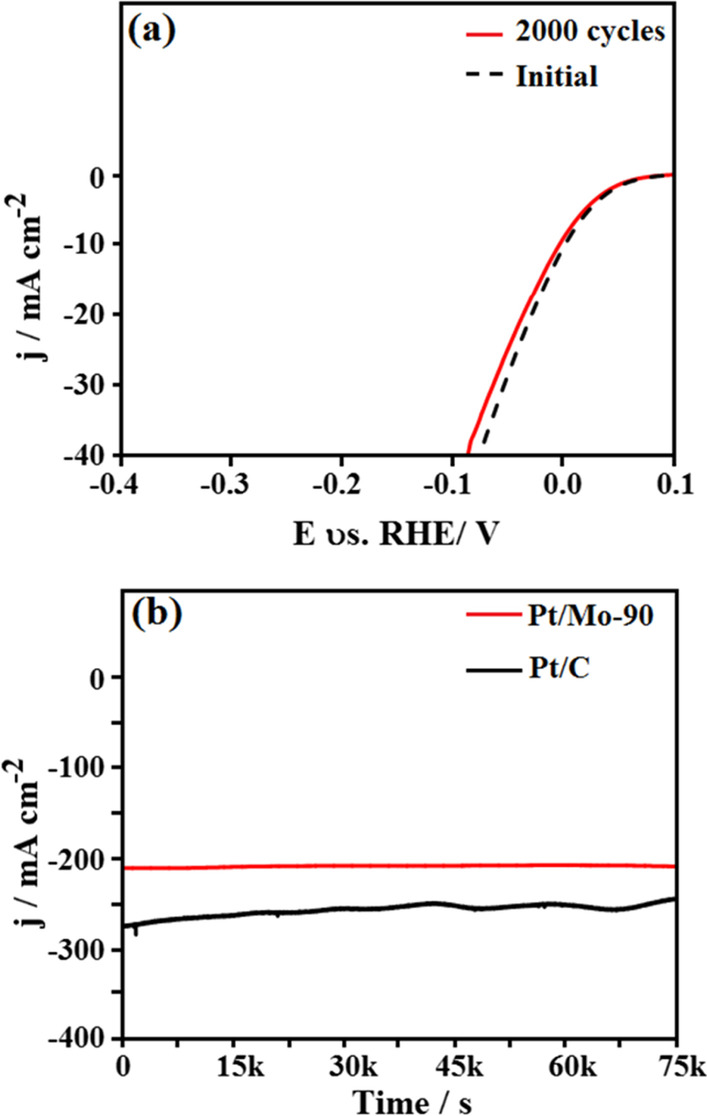

Durability and Stability

Two key factors to investigate the HER electrocatalytic activity are long-term stability and durability. Therefore, to study the as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90 composite durability, continuous cyclic voltammogram (CV) scanning was performed in 0.5 M H2SO4 as an electrolyte under the scan rate of 50 mV s−1. As seen in Fig. 7a, the LSV curve of Pt/Mo-90-modified GCE even after 2000 cycles does not show any changes or drift, which indicates that the as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90 composite has high durability.

Fig. 7.

a LSV curves of Pt/Mo-90 composite prior to and posterior to 2000 CV cycles; b The chronoamperometric response of Pt/Mo-90 and Pt/C under − 0.25 V

The stability of the electrodes is another critical parameter in HER application. For this reason, the chronoamperometric (current vs. time) response of the as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90 composite was done in N2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte (Fig. 7b). As seen in Fig. 7b, the as-synthesized Pt/Mo-90 composite shows high stability during 20 h of the experiment at a constant potential of − 0.25 V, which is more stable than Pt/C. Table 1 demonstrates some of the HER activity parameters such as overpotential, Tafel slope, and stability of the Pt/Mo-90 and some of the recently reported composites. As seen, the Pt/Mo-90 composite is comparable to that of the other electrocatalysts.

Table 1.

A Summary and a comparison of the current work with earlier studies in the literature

| Modified electrode | Electrolyte | Vover (mV) | Tafel slop (mV dec−1) | Stability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh-MoS2 | 0.5 M H2SO4 | − 47 | 24 | 20 h | [36] |

| MoSx@NiO | 1 M KOH | − 406 | 43 | 13 h | [37] |

| Co-WS2 | 0.5 M H2SO4 | − 134 | 76 | – | [38] |

| FeP/C | 0.5 M H2SO4 | − 95 | 74 | 15 h | [39] |

| MoS2 | 0.5 M H2SO4 | − 194 | 59 | 9 h | [40] |

| Pt/CoSe | 1 M PBS | − 19 | 35 | 40 h | [41] |

| Ni-CoCHH/NF-S | 1 M KOH | − 100 | 40 | 25 h | [42] |

| MoC@GS | 0.5 M H2SO4 | − 132 | 46 | 10 h | [43] |

| Pt/Mo-90 | 0.5 M H2SO4 | − 10 | 41 | 20 h | This work |

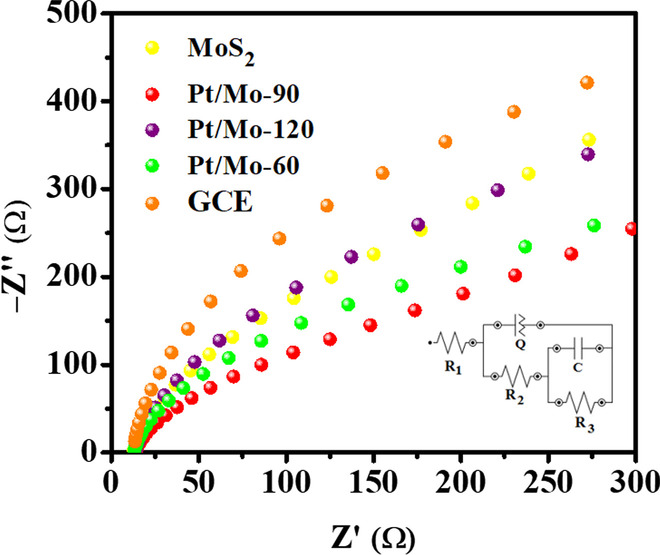

As seen in LSV curve and Tafel, Pt nanoparticles increased the HER activity of MoS2 nanosheets in the Pt/Mo-x (x = 60, 90, 120) composites This enhancement could be due to the synergistic interaction between the MoS2 nanosheets and Pt nanoparticles which are active the materials and results in increasing, the number of charge carriers transport. Therefore, to examine the kinetic interactions at the cathode, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was done in the frequency range of 0.1–105 Hz at a five mV AC signal amplitude (the reaction between ion diffusion and electrode). Figure 8 shows the Nyquist plots of the bare GCE, pure MoS2, Pt/Mo-60, Pt/Mo-90, and Pt/Mo-120-modified GCE in 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte. As shown in the inset of Fig. 8, the EIS curves were simulated using the non-linear least square method according to the equivalent circuit. On the basis of the fitting circuit, different parameters were observed, such as R1 (solution resistance), R2 (charge transfer resistance), Q (constant phase element), and C (double-layer capacitance).

Fig. 8.

Nyquist plots of bare GCE, Pure MoS2 nanosheets, Pt/Mo-60, Pt/Mo-90, and Pt/Mo-120-modified GCE in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution; inset: the equivalent circuit

A semicircle at the low-frequency region is because of a charge transfer between the electrolyte and the electrode. As is seen in Fig. 8, a semicircle can be observed at a low-frequency region, revealing that Faradaic charge transfer is happening among the electrolyte and the cathode interface (R2). Getting a satisfactory correlative between the simulated complex circuit with the experimental data, Q and R3 components were introduced to the circuit.

As is shown in Table 2, pure MoS2 and the Pt/Mo-x (x = 60, 90, 120) composites exhibit almost the same solution resistances (R1). However, the R2 of the Pt/Mo-90 composite is smaller than the pure MoS2 (Table 2). This indicates that the electrocatalytic activity of the MoS2 nanosheets was increased by the presence of Pt caused by the increased number of charge carriers transport, resulting in a faster rate of charge transfer. However, the further increment of Pt loading beyond the optimum level of 90 μL caused a decrease of catalytic activity, as shown by the increased R2 value of the Pt/Mo-120-modified GCE electrode (Fig. 8 and Table 2). It was indicated that excessive loading of Pt could lead to agglomeration of Pt nanoparticles during synthesis, causing reduced surface area and catalytic active sites. This increase in R2 value brought about a significant decrease in HER catalytic performance.

Table 2.

Electrochemical parameters achieved from the simulation of the EIS results

| Electrode | R1 | R2 | R3 | C | Q | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ω cm2) | (Ω cm2) | (Ω cm2) | (μF cm2) | Y0 (μ Ω−1 sncm−2) | ||

| MoS2-GCE | 35.6 | 996 | 4.5 × 103 | 122 | 10.60 | 0.80 |

| Pt/Mo-60-GCE | 38.1 | 242 | 1.59 × 103 | 83 | 4.08 | 0.85 |

| Pt/Mo-90-GCE | 34.8 | 147 | 1.22 × 103 | 27 | 2.83 | 0.89 |

| Pt/Mo-120-GCE | 35.1 | 635 | 1.97 × 103 | 31 | 2.63 | 0.77 |

To understand better the mechanism of electron transfer, we propose here a band alignment of the most efficient Pt/Mo-90 composite device.

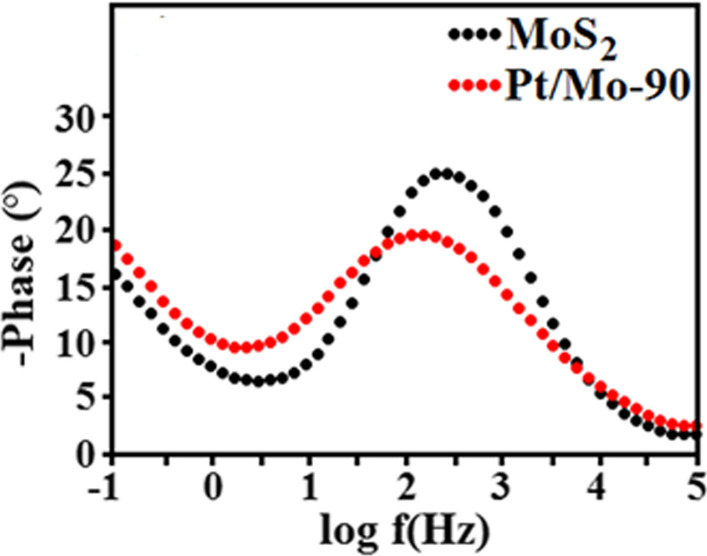

Figure 9 shows the effect of Pt nanoparticles on the electron–hole recombination of the HER devices that could be obtained from the Bode EIS plot [44]. The electron lifetime () can be estimated using the frequency at the middle frequency peak (1–100 Hz) in the Bode phase plot from the following equation [45]

| 4 |

Based on the Bode plot (Fig. 9, it is obvious that the electron lifetime of Pt/Mo-90 composite is higher than pure MoS2 because of the lower . Therefore, presence of Pt nanoparticles in composite has enhanced electron lifetime which leads to improve the HER activity of the device.

Fig. 9.

Bode EIS plots of the pure MoS2 and Pt/Mo-90 composite

Conclusion

In conclusion, a hydrothermal method is utilized to synthesis MoS2 nanosheets with an average diameter of 1 μm. At the later stage, Pt nanoparticles having a diameter of 2 nm on average and different Pt content were deposited onto MoS2 nanosheets to produce Pt/Mo-x (x = 60, 90, 120) composites as electrocatalysts for the HER. XRD micrographs, XPS, TEM, and Raman support the presence of Pt nanoparticle on the surface of MoS2. Among these different electrocatalysts, the Pt/Mo-90- modified GCE showed excellent electrocatalytic activity, stability, and durability for HER application. Regarding the overpotential, the Pt/Mo-90 composite showed Pt-like activity with an overpotential of only − 0.01 V μs. RHE to reach a current density of − 10 mA cm−2 in 0.5 M H2SO4. Moreover, in comparing with the Tafel slop of Pt/C (37 mV dec−1), the Pt/Mo-90 composite exhibited the smallest Tafel slope of 41 mV dec−1. This composite showed good long-term stability after 20 h as well. The EIS measurement confirmed that the electrodes' electrocatalytic activity depends on the amount of Pt loading; increasing the Pt loading up to 120 μl leads to a rise in charge transfer resistance of the composite electrode, which results in a decrease in the HER electrocatalytic activity.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- Pt

Platinum

- Pt/Mo

Platinum molybdenum disufide

- MoS2

Molybdenum disulfide

- H2

Hydrogen

- HER

Hydrogen evolution reaction

- TMDs

Transition Metal dichalcogenides

- H2PtCl6

Chloroplatinic acid solution

- C2H5NS

Thioacetamide powder

- ((NH4)6Mo7O24)

Ammonium heptamolybdate powder

- (H2SO4)

Sulfuric acid solution

- H2O

Water

- Pt/Mo-x (x = 60, 90, 120)

Platinum molybdenum disufide composites with different Pt loading

- LSV

Linear sweep voltammetry

- EIS

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

- RHE

Reversible hydrogen electrode

- Pt/C

Commercial Platinum 20 wt.%

- GCE

Glassy carbon electrode

- 2H

Hexagonal

- XRD

X-Ray diffraction

- XPS

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- S

Sulfur

- Mo

Molybdenum

- H3O+

Hydronium ion

- b

Tafel slope

- F

Faraday constant

- R

Ideal gas constant

- α

Symmetry factor

- T

Temperature

- CV

Cyclic voltammetry

- N2

Nitrogen

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- KOH

Potassium hydroxide

- R1

Solution resistance

- R2

Charge transfer resistance

- Q

Constant phase element

- C

Double-layer capacitance

- R3

Resistance

- CB

Conduction band

- VB

Valence band

Electron lifetime

- fp

Frequency

Authors' contributions

MR carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. MS conceived and supervised the study. YA supervised the study. BTG did the characterization and interpretation. HB assisted with Synthesis of materials and writing. EM was responsible for electrochemical measurement. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All the authors have contributed equally in preparing the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the AUA-UAEU Joint Research Grant Project (IF016-2021 and G00003485).

Availability of data and materials

All the data and material are available in the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mina Razavi, Email: minarazavi220@gmail.com.

M. Sookhakian, Email: m.sokhakian@um.edu.my

Y. Alias, Email: yatimah70@um.edu.my

References

- 1.Lin L, Zhou W, Gao R, et al. Low-Temperature hydrogen production from water and methanol using Pt/α-MoC catalysts. Nature. 2017;544:80–83. doi: 10.1038/nature21672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin Z, Li Y, Hao X, 郝旭强靳治良, 李彦兵 * (2021) of 15) 物理化学学报 Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. Phys-Chim Sin 2021:1912033. 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201912033

- 3.Liu Y, Hao X, Hu H, Jin Z. High efficiency electron transfer realized over nis2/mose2 s-scheme heterojunction in photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Wuli Huaxue Xuebao/Acta Phys Chim Sin. 2021 doi: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB202008030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Q, Chen W, Cheng H, et al. WS2 nanosheets with highly-enhanced electrochemical activity by facile control of sulfur vacancies. ChemCatChem. 2019;11:2667–2675. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201900341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo J, Xu P, Zhang D, et al. Synthesis of 3D-MoO2 microsphere supported MoSe2 as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanotechnology. 2017 doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aa8947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu D, Tong R, Qu Y, et al. Highly improved electrocatalytic activity of NiSx: effects of Cr-doping and phase transition. Appl Catal B. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.118721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lv H, Xi Z, Chen Z, et al. A new core/shell NiAu/Au nanoparticle catalyst with pt-like activity for hydrogen evolution reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5859–5862. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie J, Gao L, Jiang H, et al. Platinum nanocrystals decorated on defect-rich MoS2 nanosheets for pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction. Cryst Growth Des. 2019;19:60–65. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.8b01594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Q, Shao M, Yu SH, et al. One-pot synthesis of Co-doped VSe2 nanosheets for enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2019;2:644–653. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.8b01659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu GR, Hui JJ, Huang T, et al. Platinum nanocuboids supported on reduced graphene oxide as efficient electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J Power Sour. 2015;285:393–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.03.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin H, Zhao S, Zhao K, et al. Ultrathin platinum nanowires grown on single-layered nickel hydroxide with high hydrogen evolution activity. Nat Commun. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhong X, Tang J, Wang J, et al. 3D heterostructured pure and N-doped Ni3S2/VS2 nanosheets for high efficient overall water splitting. Electrochim Acta. 2018;269:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.02.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao J, Wei F, Zhang X, et al. Defect and doping engineered penta-graphene for catalysis of hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s11671-021-03590-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, An P, Zhou W, et al (2018) Dynamic traction of lattice-confined platinum atoms into mesoporous carbon matrix for hydrogen evolution reaction [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Navaee A, Salimi A. Anodic platinum dissolution, entrapping by amine functionalized-reduced graphene oxide: a simple approach to derive the uniform distribution of platinum nanoparticles with efficient electrocatalytic activity for durable hydrogen evolution and ethanol oxidation. Electrochim Acta. 2016;211:322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sookhakian M, Ridwan NA, Zalnezhad E, et al. Layer-by-layer electrodeposited reduced graphene oxide-copper nanopolyhedra films as efficient platinum-free counter electrodes in high efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. J Electrochem Soc. 2016;163:D154–D159. doi: 10.1149/2.0561605jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azarang M, Sookhakian M, Aliahmad M, et al. Nitrogen-doped graphene-supported zinc sulfide nanorods as efficient Pt-free for visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43:14905–14914. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.06.082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sookhakian M, Tong GB, Alias Y. In-Situ electrodeposition of rhodium nanoparticles anchored on reduced graphene oxide nanosheets as an efficient oxygen reduction electrocatalyst. Appl Organomet Chem. 2020 doi: 10.1002/aoc.5370. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sookhakian M, Ullah H, Mat Teridi MA, et al. Boron-doped graphene-supported manganese oxide nanotubes as an efficient non-metal catalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction. Sustain Energy Fuels. 2020;4:737–749. doi: 10.1039/c9se00775j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernsmeier D, Sachse R, Bernicke M, et al. Outstanding hydrogen evolution performance of supported Pt nanoparticles: Incorporation of preformed colloids into mesoporous carbon films. J Catal. 2019;369:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2018.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zainal SN, Sookhakian M, Woi PM, Alias Y. Ternary molybdenum disulfide nanosheets-cobalt oxide nanocubes-platinum composite as efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. Electrochim Acta. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sookhakian M, Basirun WJ, Goh BT, et al. Molybdenum disulfide nanosheet decorated with silver nanoparticles for selective detection of dopamine. Colloids Surf B. 2019;176:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su J, Liu ZT, Feng LP, Li N. Effect of temperature on thermal properties of monolayer MoS2 sheet. J Alloys Compd. 2015;622:777–782. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.10.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu P, Sun G, Chen Y, et al. MoSe2-Ni3Se4 hybrid nanoelectrocatalysts and their enhanced electrocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s11671-020-03368-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu X, Liu L. MoS2 with controlled thickness for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s11671-021-03596-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Q, Qu Y, Liu D, et al. Two-dimensional layered materials: high-efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2020;3:6270–6296. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.0c01331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar DP, Hong S, Reddy DA, Kim TK. Ultrathin MoS2 layers anchored exfoliated reduced graphene oxide nanosheet hybrid as a highly efficient cocatalyst for CdS nanorods towards enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production. Appl Catal B. 2017;212:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.04.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Y, Ji Z, Zu S, et al. Ultrafast plasmonic hot electron transfer in Au nanoantenna/MoS2 heterostructures. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:6394–6401. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201601779. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tajabadi MT, Sookhakian M, Zalnezhad E, et al. Electrodeposition of flower-like platinum on electrophoretically grown nitrogen-doped graphene as a highly sensitive electrochemical non-enzymatic biosensor for hydrogen peroxide detection. Appl Surf Sci. 2016;386:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.06.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SK, Chu D, Song DY, et al. Electrical and photovoltaic properties of residue-free MoS2 thin films by liquid exfoliation method. Nanotechnology. 2017 doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aa6740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burman D, Santra S, Pramanik P, Guha PK. Pt decorated MoS2 nanoflakes for ultrasensitive resistive humidity sensor. Nanotechnology. 2018 doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/aaa79d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shao J, Li Y, Zhong M, et al. Enhanced-performance flexible supercapacitor based on Pt-doped MoS2. Mater Lett. 2019;252:173–177. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2019.05.124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi K, Yu S, Wang Q, et al. Decoration of the inert basal plane of defect-rich MoS2 with Pd atoms for achieving Pt-similar HER activity. J Mater Chem A. 2016;4:4025–4031. doi: 10.1039/c5ta10337a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Cao X, Fang L, et al. MoS2 nanoflower supported Pt nanoparticle as an efficient electrocatalyst for ethanol oxidation reaction. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2019;44:16411–16423. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.04.251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Wang H, Xie L, et al. MoS2 nanoparticles grown on graphene: an advanced catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7296–7299. doi: 10.1021/ja201269b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng Y, Lu S, Liao F, et al. Rh-MoS2 nanocomposite catalysts with Pt-like activity for hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv Funct Mater. 2017 doi: 10.1002/adfm.201700359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibupoto ZH, Tahira A, Tang PY, et al. MoS x @NiO composite nanostructures: an advanced nonprecious catalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction in alkaline media. Adv Funct Mater. 2019 doi: 10.1002/adfm.201807562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou L, Yan S, Song H, et al. Multivariate control of effective cobalt doping in tungsten disulfide for highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Sci Rep. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37598-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng Z, Qiu X, Yu Y, et al. Polydopamine coated prussian blue analogue derived hollow carbon nanobox with FeP encapsulated for hydrogen evolution. Carbon. 2019;152:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2019.05.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolar S, Shit S, Kumar JS, et al. Optimization of active surface area of flower like MoS2 using V-doping towards enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction in acidic and basic medium. Appl Catal B. 2019;254:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang K, Liu B, Luo M, et al. Single platinum atoms embedded in nanoporous cobalt selenide as electrocatalyst for accelerating hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat Commun. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09765-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu W, Li X, Wei F, et al. Fast sulfurization of nickel foam-supported nickel-cobalt carbonate hydroxide nanowire array at room temperature for hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. Electrochim Acta. 2019;318:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.06.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi Z, Wang Y, Lin H, et al. Porous nanoMoC@graphite shell derived from a MOFs-directed strategy: an efficient electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J Mater Chem A. 2016;4:6006–6013. doi: 10.1039/c6ta01900e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nouri M, Zare-Dehnavi N, Jamali-Sheini F, Yousefi R. Synthesis and characterization of type-II p(CuxSey)/n(g-C3N4) heterojunction with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic performance for degradation of dye pollutants. Colloids Surf A. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.124656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moghaddam Saray A, Zare-Dehnavi N, Jamali-Sheini F, Yousefi R. Type-II p(SnSe)-n(g-C3N4) heterostructure as a fast visible-light photocatalytic material: Boosted by an efficient interfacial charge transfer of p-n heterojunction. J Alloys Compd. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.154436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data and material are available in the manuscript.