Abstract

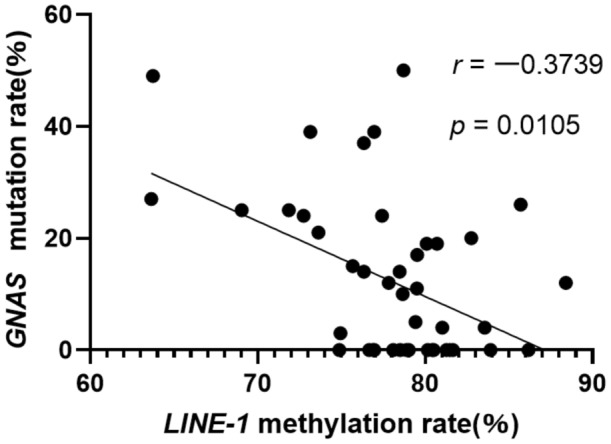

We aimed to assess some of the potential genetic pathways for cancer development from non-malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) by evaluating genetic mutations and methylation. In total, 46 dissected regions in 33 IPMN cases were analyzed and compared between malignant-potential and benign cases, or between malignant-potential and benign tissue dissected regions including low-grade IPMN dissected regions accompanied by malignant-potential regions. Several gene mutations, gene methylations, and proteins were assessed by pyrosequencing and immunohistochemical analysis. RASSF1A methylation was more frequent in malignant-potential dissected regions (p = 0.0329). LINE-1 methylation was inversely correlated with GNAS mutation (r = − 0.3739, p = 0.0105). In cases with malignant-potential dissected regions, GNAS mutation was associated with less frequent perivascular invasion (p = 0.0128), perineural invasion (p = 0.0377), and lymph node metastasis (p = 0.0377) but significantly longer overall survival, compared to malignant-potential cases without GNAS mutation (p = 0.0419). The presence of concordant KRAS and GNAS mutations in the malignant-potential and benign dissected regions were more frequent among branch-duct IPMN cases than among the other types (p = 0.0319). Methylation of RASSF1A, CDKN2A, and LINE-1 and GNAS mutation may be relevant to cancer development, IPMN subtypes, and cancer prognosis.

Subject terms: Cysts, Gastrointestinal cancer, Oncogenes, Tumour biomarkers

Introduction

An intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) in the pancreas is a cystic tumor with unique histopathologic features, including massive dilatation of the pancreatic duct, mucin hypersecretion, and papillary epithelial projections into the pancreatic duct tributaries1–3. Some IPMNs progress to IPMN with associated invasive carcinoma (IC-IPMN), which is associated with a poor prognosis4. Pre-operative diagnosis of high-risk IPMNs is still challenging, although the International Consensus Guidelines for the Management of pancreatic IPMNs were revised in 20175. The guideline defines main-duct (MD) IPMN patients and branch-duct (BD) IPMN patients based on worrisome features and high-risk stigmata to determine whether surgery is indicated. Although these criteria are useful for identifying patients recommended for surgery, their diagnostic accuracy for invasive IPMN before surgery needs to be improved6.

Characterization of the methylation patterns of genes implicated in human tumorigenesis may grant insight into the biology of pancreatic IPMNs7. KRAS and BRAF are two key oncogenes in the RAS/RAF/MEK/MAP-kinase signaling pathway and are also common gene mutations in colorectal cancer8. Pancreatic tumors reportedly harbor several gene aberrations, including those in KRAS, GNAS, and BRAF9–11. The early acquisition of a KRAS mutation is likely essential for triggering the adenoma-carcinoma sequence in pancreatic tumors12, and molecular profiling of KRAS and GNAS can help with determining whether invasive cancer in a pancreas with an IPMN is associated or concomitant13. Additionally, methylation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), a tumor suppressor gene that encodes P16 (or P16INK4a) and P14arf14, long interspersed nuclear element-1 (LINE-1) retrotransposition, a major hallmark of cancer accompanied by global chromosomal instability, genomic instability, and genetic heterogeneity15, and Ras association domain family member 1A (RASSF1A), a tumor-suppressor gene frequently inactivated in various human cancers16,17 has been studied in pancreatic tumors14,18,19. However, few studies have examined their methylation status in IPMN cases. Moreover, some IPMNs express P16 and P539,20, which are encoded by CDKN2A and TP53, respectively. These gene and protein features may be linked to the clinical course of an IPMN, providing insight into its progression and enabling prediction of malignant transformation.

We assessed some of the potential genetic pathways for cancer development from non-malignant IPMN and evaluated the clinicopathological characteristics of IPMNs with based on genetic mutation and methylation profiling using pyrosequencing and immunohistochemical analysis.

Methods

Case selection

In total, 13 cases of IPMN with associated invasive carcinoma (IC-IPMN), 5 cases of IPMN with high-grade dysplasia (HG-IPMN, also known as carcinoma in situ), and 15 cases of sporadic IPMN with low-grade dysplasia (LG-IPMN) were retrieved from the pathology files of the Department of Experimental Pathology and Tumor Biology, Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences. All tumor samples comprised resected, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. Informed consent was obtained, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nagoya City University (approval no. 60-00-0990) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Clinicopathologic data were obtained from medical records. All hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides were reviewed by three authors (K.M., G.A., and H.K.) blinded to the clinical information.

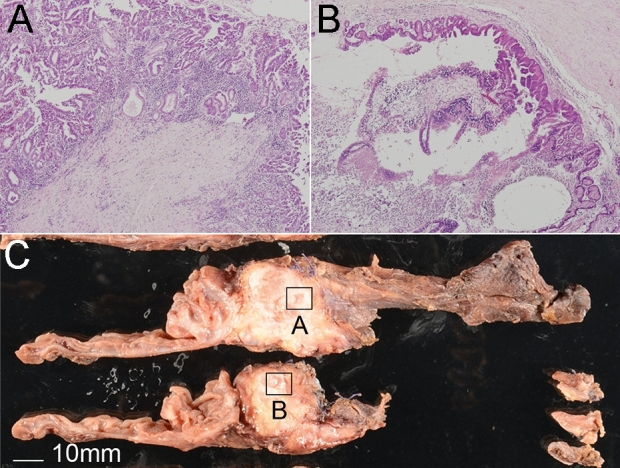

Other LG-IPMN spots were chosen from the low-grade IPMN lesion involved in the original malignant-potential IPMN, as close as possible to, and ultimately one or two slides away from, the original 18 IC-IPMN and HG-IPMN lesions. They were dissected and collected as accompanying LG-IPMN (A-IPMN) samples. Representative images of the positional relationship between the malignant-potential and A-IPMN dissected regions are shown in Fig. 1. According to radiographic images and pathological findings, all IC-IPMNs were diagnosed with IPMN-derived carcinoma, which is different from concomitant invasive carcinoma21.

Figure 1.

Representative images of the positional relationships between malignant-potential IPMN ((A), HG-IPMN in the image) and A-IPMN (B) dissected regions. Original magnification, × 40. Scale bar = 10 mm. A-IPMN was defined as a benign IPMN dissected region, as close as possible to the malignant-potential IPMN (within one or two slices).

Clinicopathologic data

The following clinicopathologic factors were analyzed: age, sex, primary tumor site (head, body/tail, or multifocal), tumor type (MD-IPMN, BD-IPMN, or mixed), tumor size, main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilatation, IPMN subtype, overall survival (OS), presence of mural nodules, and lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, and perineural invasion status.

DNA extraction and bisulfite treatment

All cases were manually macrodissected (approximately 10 × 10 mm) from tissues under a microscope (Eclipse 80i, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using a fine needle, and DNA was isolated from FFPE sections using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and Maxwell 16 FFPE Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI). A NanoDrop™ ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used to quantify the purified DNA. Bisulfite treatment was carried out as described previously22.

DNA methylation analysis

DNA methylation was analyzed using bisulfite pyrosequencing as described previously23,24. Briefly, genomic DNA (1 μg) was modified with sodium bisulfite using an EpiTect Bisulfite kit (Qiagen). Pyrosequencing was carried out using a PSQ 96MA system (Qiagen) with a Pyro Gold Reagent kit (Qiagen), and the results were analyzed using Pyro Q-CpG software (Qiagen). Methylation of CDKN2A, LINE-1, and RASSF1A was analyzed using bisulfite pyrosequencing. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S1. A cut-off value of 10% was used to determine whether the CDKN2A and RASSF1A genes were methylation-positive as described previously25–27. LINE-1 methylation was analyzed quantitatively.

Analysis of KRAS, BRAF, and GNAS mutations

Mutations in KRAS (codons 12 and 13 of exon 2), BRAF (V600E), and GNAS (codon 201 of exon 8) were examined using a PyroMark Q24 pyrosequencer as described previously28,29. Each reaction contained 1× PCR buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM each dNTP, 5 pmol forward primer, 5 pmol reverse primer (biotinylated), 0.8 U HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen), 10 ng of template DNA, and dH2O to a final volume of 25 μL. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 15 min; 38 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 53 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 20 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min, followed by holding at 8 °C. Following amplification, 10 μL of biotinylated PCR product was immobilized on streptavidin-coated Sepharose beads (streptavidin Sepharose high performance; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ) and washed in 70% EtOH. The purified biotinylated PCR products were loaded into the PyroMark Q24 system (Qiagen) with PyroMark Gold Reagent (Qiagen) containing 0.3 μM sequencing primer and annealing buffer. KRAS Pyro® (Qiagen) and BRAF Pyro® (Qiagen) were used to detect the KRAS and BRAF mutations, respectively, and the GNAS primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S1. A cut-off value of 10% was used to determine whether the genes were mutation-positive as described previously30.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. After antigen retrieval using heat treatment, immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed using an automated immunostainer (Bond-Max, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and monoclonal antibodies against RASSF1 (clone EPR7127, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:100), P16 (clone E6H4, Ventana, Tucson, AZ; 1:1), P53 (clone DO7 NCL-L-p53-DO7, Leica Biosystems; 1:800). The tissue was considered to express RASSF1 and P16 when the stain levels for these proteins were equal to those seen in a normal pancreatic duct and a homogenous staining P53 IHC pattern in the epithelium was considered to reflect the expression of P53. For all IHC staining, the expression of protein in > 10% of epithelium from the dissected epithelium was considered a positive result31–34.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using non-parametric tests. Continuous data are given as median values with ranges or means with SDs. Statistical evaluation of data from two groups was performed using the χ2 test, Fisher exact test, or Mann–Whitney U test for unpaired cases. The OS was measured from the date of surgery or diagnosis to the date of death from any cause. Patients not known to have died were censored on the date of their last follow-up. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 were considered significant. Correlations of methylation levels with other biological features were evaluated using Spearman’s rank-order correlation. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Patient characteristics

This study included 13 IC-IPMN, 5 HG-IPMN, 15 LG-IPMN, and 13 A-IPMN cases. According to the World Health Organization classification scheme35 and a previous study36, IPMN cases were classified into malignant-potential IPMN (IC-IPMN and HG-IPMN) and LG-IPMN cases. The patients’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The average age of the malignant-potential IPMN and LG-IPMN cases was 69 (range 55–84) and 68 (43–80) years, respectively. The malignant-potential IPMN cases included 8 males and 10 females, and the LG-IPMN cases included 13 males and 2 females. There were eight MD-IPMN cases (44%) among the malignant-potential IPMN cases, and eight of the LG-IPMN cases were also MD-IPMN cases (53%). Pathological examination of resected IC-IPMN tissues detected perivascular invasion and perineural invasion in 7 (53%) and 6 (46%) cases, respectively. Regarding therapeutic approaches, of 13 IC-IPMN patients, 4 patients received chemotherapy, 1 received radiotherapy, and 1 patient received chemoradiotherapy after tumor resection. Among the malignant-potential IPMN cases, the follow-up period ranged from 3 to 118 months. The overall 1-year survival rate of malignant-potential IPMN patients was 77%, with a median survival duration of 47 months. No significant differences in the patients’ characteristics were evident between the malignant-potential and LG-IPMN cases, except the proportion of males (44% vs. 86%, p = 0.0272).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Malignant-potential IPMN (n = 18) | LG-IPMN (n = 15) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-IPMN (n = 13) | HG-IPMN (n = 5) | ||||

| Age (mean [range]) | 69 (55–84) | 71 (68–76) | 68 (43–80) | NS* | |

| Sex (male/female) | 6/7 | 2/3 | 13/2 | 0.0272* | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||||

| Head | 6 (46) | 3 (60) | 7 (46) | NS* | |

| Body or tail | 6 (46) | 1 (20) | 8 (53) | ||

| Multifocal | 1 (7) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | ||

| IPMN type, n (%) | NS* | ||||

| MD-IPMN | 6 (46) | 2 (40) | 8 (53) | ||

| BD-IPMN | 6 (46) | 1 (20) | 7 (46) | ||

| Mixed | 1 (7) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | ||

| Tumor size (mm), n (%) | NS* | ||||

| < 30/ ≥ 30 | 6 (46)/7 (53) | 3 (60)/2 (40) | 9 (60)/6 (40) | ||

| Mural nodule, n (%) | NS* | ||||

| Enhanced /none or non-enhanced | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 3 (20) | ||

| 13 (100) | 4 (80) | 12 (80) | |||

| MPD dilatation (mm), n (%) | NS* | ||||

| < 10/ ≥ 10 | 3 (23)/10 (76) | 0 (0)/5 (100) | 4 (26)/11 (73) | ||

| Stage, n (%) | |||||

| IA/IB | 3 (23)/2 (15) | – | – | ||

| IIA/IIB | 1 (7)/5 (38) | – | – | ||

| III | 2 (15) | – | – | ||

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | |||||

| Yes/no | 6 (46)/7 (53) | – | |||

| Perivascular invasion, n (%) | |||||

| Yes/no | 7 (53)/6 (46) | – | – | ||

| Perineural invasion, n (%) | |||||

| Yes/no | 6 (46)/7 (53) | – | – | ||

| Histopathologic type | Malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions (n = 18) | Benign IPMN dissected regions (n = 28) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-IPMN (n = 13) | HG-IPMN (n = 5) | LG-IPMN (n = 15) | A-IPMN (n = 13) | ||

| Gastric, n (%) | 6 (33†) | 0 (0†) | 12 (42‡) | 6 (21‡) | NS§ |

| Intestinal, n (%) | 5 (27†) | 4 (22†) | 3 (10‡) | 7 (25‡) | NS§ |

| Pancreatobilliary, n (%) | 2 (11†) | 1 (5†) | 0 (0‡) | 0 (0‡) | 0.0255§ |

MD-IPMN main duct IPMN, BD-IPMN branch duct IPMN.

*p-value for comparisons of malignant-potential IPMN and LG-IPMN.

†Proportions among malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions.

‡Proportions among benign dissected regions.

§p-value for comparisons among malignant-potential IPMN (IC-IPMN and HG-IPMN) and benign IPMN (LG-IPMN and A-IPMN) dissected regions.

On the basis of histology, all dissected tissue regions were classified as malignant-potential (IC-IPMN or HG-IPMN) or benign (LG-IPMN or A-IPMN) and further subclassified into gastric (n = 24), intestinal (n = 19), or pancreatobiliary types (n = 3). All dissected regions of pancreatobiliary type were malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions and statistically more frequent compared with benign IPMN dissected regions (16% vs 0%, p = 0.0255).

Pyrosequencing

Pyrosequencing analysis was performed in all cases (Supplementary Fig. S1), and the results are represented as heat maps (Fig. 2). The positive RASSF1A methylation rate differed significantly between the malignant-potential and benign IPMN dissected regions (94% vs. 67%, p = 0.0329). No significant difference in CDKN2A methylation (11% vs. 3%, p = 0.3121), KRAS mutation (33% vs. 35%, p = 0.8686), or GNAS mutation (38% vs. 53%, p = 0.3306) was evident between the two groups. LINE-1 methylation levels have no significant difference between the two groups (p = 0.7173, Mann–Whitney U test). BRAF mutation was detected in one A-IPMN dissected region surrounding an HG-IPMN.

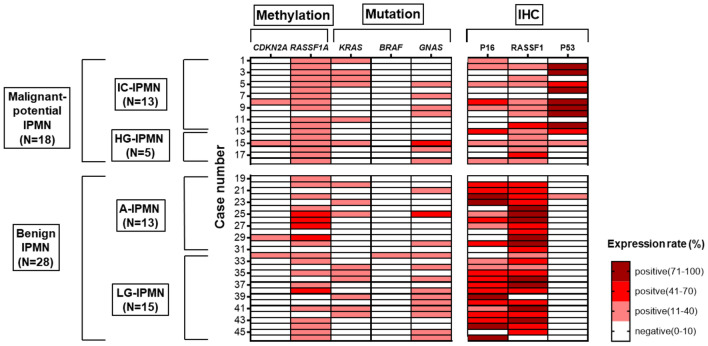

Figure 2.

Heat map visualization of the results of pyrosequencing and IHC analyses. White cells, negative expression. Red or brown cells, positive expression. Because of the undetermined threshold, LINE-1 methylation is not depicted.

LINE-1 methylation was inversely correlated with GNAS mutation (r = − 0.3739, p = 0.0105, Fig. 3), but it was not significantly correlated with either KRAS mutation (r = − 0.1633, p = 0.2782) or RASSF1A methylation (r = − 0.1151, p = 0.4463). Additionally, genetic aberrations in A-IPMN dissected regions showed no significance compared to LG-IPMN dissected regions.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots of the associations of the LINE-1 methylation rate with the GNAS methylation rate.

IHC analyses of P16, P53, and RASSF1

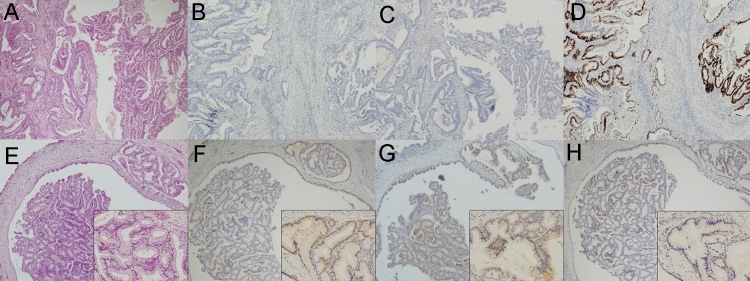

Representative images of the malignant-potential and benign IPMN dissected regions are shown in Fig. 4A–H. Typically, the malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions (Fig. 4A) were P16 negative (Fig. 4B), RASSF1 negative (Fig. 4C), and P53 positive (Fig. 4D), whereas the benign IPMN dissected regions (Fig. 4E) were P16 positive (Fig. 4F), RASSF1 positive (Fig. 4G), and P53 negative (Fig. 4H). The IHC results are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 4.

Representative images of a malignant-potential dissected region (A–D) and benign dissected region (E–H) showing H&E staining (A,E), and P16 (B,F), RASSF1 (C,G), and P53 (D,H) expression. Original magnification, × 40; inset magnification, × 200.

P16 positivity according to IHC was more frequent among benign than malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions (82% vs. 44%, p = 0.0078). The rate of CDKN2A methylation was inversely correlated with the rate of P16 IHC expression (p = 0.0024, r = − 0.4375). Although there was no significant correlation between the rate of RASSF1A methylation and the rate of RASSF1 expression (p = 0.3588), 9 of 10 (90%) RASSF1A hypomethylation cases were positive for RASSF1 according to IHC. The rate of P53 positivity according to IHC, by contrast, was more frequent among malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions than benign IPMN dissected regions (55% vs. 3%, p < 0.0001).

The rates of P16, RASSF1, and P53 positivity according to IHC did not differ significantly across clinicopathological parameters or between LG-IPMN and A-IPMN dissected regions.

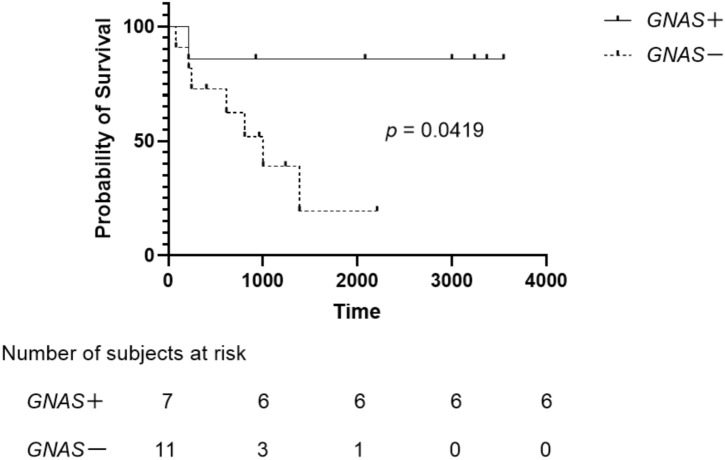

Clinicopathologic associations of pyrosequencing and IHC outcomes

The relationships between clinicopathological parameters, methylation and mutation status, and IHC results are shown in Table 2. Tumor size, the presence of mural nodules, and MPD diameter were compared among all cases; histological types of IPMN were compared among all tissue dissected regions; and the status of lymph node metastasis, perivascular invasion, and perineural invasion was compared among malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions. For all dissected regions, CDKN2A methylation was more frequent in intestinal-type dissected regions than in gastric-type dissected regions (15% vs. 0%; p = 0.0436). Among the malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions, GNAS mutation was less frequent among those with perivascular invasion compared to those without (0% vs. 63%, p = 0.0128), dissected regions with perineural invasion (0% vs. 58%; p = 0.0377), or dissected regions exhibiting lymph node metastasis (0% vs. 58%; p = 0.0377). Furthermore, 7 cases of malignant-potential dissected regions with a GNAS mutation had a significantly longer OS than 11 cases of malignant-potential dissected regions without a GNAS mutation (undefined days vs. 1004 days; p = 0.0419) (Fig. 5). The Histopathologic type of IPMN did not affect the prognosis of malignant-potential IPMN.

Table 2.

Relationships between the clinicopathologic parameters and methylation, mutation, and IHC results.

| Clinicopathologic features | n | CDKN2A methylation | RASSF1A methylation | KRAS mutation | GNAS mutation | P16 IHC | P53 IHC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | n (%) | p | ||

| Clinical factors | |||||||||||||

| Tumor size (mm)* | |||||||||||||

| < 30 | 19 | 0 (0) | NS | 15 (78) | NS | 9 (47) | NS | 12 (63) | NS | 12 (63) | NS | 4 (21) | NS |

| ≧ 30 | 14 | 2 (14) | 12 (85) | 5 (35) | 6 (42) | 10 (71) | 6 (42) | ||||||

| Mural nodule* | |||||||||||||

| Enhanced | 11 | 0 (0) | NS | 10 (90) | NS | 4 (36) | NS | 6 (54) | NS | 7 (63) | NS | 4 (36) | NS |

| None/non-enhanced | 22 | 2 (9) | 17 (77) | 10 (45) | 12 (54) | 15 (68) | 6 (27) | ||||||

| MPD dilatation (mm)* | |||||||||||||

| < 10 | 7 | 0 (0) | NS | 5 (71) | NS | 4 (57) | NS | 3 (42) | NS | 6 (85) | NS | 1 (14) | NS |

| ≧ 10 | 26 | 2 (7) | 22 (84) | 10 (38) | 15 (57) | 16 (61) | 9 (34) | ||||||

| Pathologic factors | |||||||||||||

| Histologic types† | |||||||||||||

| Gastric | 24 | 0 (0) | 0.0436§ | 21 (87) | NS | 9 (37) | NS | 9 (37) | NS | 19 (79) | NS | 5 (20) | NS |

| Intestinal | 19 | 3 (15) | 12 (63) | 4 (21) | 12 (63) | 10 (52) | 5 (26) | ||||||

| Pancreatobiliary | 3 | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | ||||||

| Lymph node metastasis‡ | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 1 (16) | NS | 6 (100) | NS | 1 (16) | NS | 0 (0) | 0.0377 | 3 (50) | NS | 5 (83) | NS |

| No | 12 | 1 (8) | 11 (91) | 5 (41) | 7 (58) | 3 (25) | 5 (41) | ||||||

| Perivascular invasion‡ | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 7 | 1 (14) | NS | 7 (100) | NS | 3 (42) | NS | 0 (0) | 0.0128 | 4 (57) | NS | 4 (57) | NS |

| No | 11 | 1 (9) | 10 (90) | 3 (27) | 7 (63) | 4 (36) | 6 (54) | ||||||

| Perineural invasion‡ | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 6 | 0 (0) | NS | 4 (66) | NS | 2 (33) | NS | 0 (0) | 0.0377 | 3 (50) | NS | 4 (66) | NS |

| No | 12 | 2 (16) | 9 (75) | 4 (33) | 7 (58) | 5 (41) | 6 (50) | ||||||

No significant differences were observed for LINE-1 methylation, BRAF mutation, or the IHC results for RASSF1.

*All cases.

†All dissected tissue regions.

‡Only malignant-potential cases.

§p-value for comparison between gastric and intestinal types.

Figure 5.

Overall survival of patients with (solid line) and without (dotted line) GNAS mutation in the malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method and were compared using the log-rank test.

RASSF1A methylation, LINE-1 methylation, KRAS mutation, and BRAF mutation status as well as the P16, RASSF1, and P53 positivity rates according to IHC did not differ significantly across clinicopathological parameters.

Methylation and mutation differences in two dissected regions from the same case

To explore malignant initiation and transformation, the methylation and mutation status was compared between malignant-potential IPMN (IC-IPMN and HG-IPMN) and benign A-IPMN dissected regions obtained in pairs from 11 IC-IPMN and 2 HG-IPMN cases (Table 3). Overall, 5 out of 13 (38%) malignant-potential dissected regions harbored the same KRAS and GNAS mutations. Cases harboring concordant sequences of KRAS and GNAS mutations between malignant-potential IPMN and A-IPMN dissected regions were more frequent among BD-IPMN cases than among MD-IPMN and mixed IPMN cases (80% vs. 12%, p = 0.0319).

Table 3.

Patterns of methylation and mutation results for malignant-potential IPMN and A-IPMN dissected regions accompanied by malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions.

| Case # | Subtype | Malignant-potential IPMN dissected region | A-IPMN dissected region | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KRAS Codon 12 |

GNAS V600E |

Methylation positive |

KRAS Codon 12 |

GNAS V600E |

Methylation positive | |||||||

| Sequence | % | Sequence | % | Sequence | % | Sequence | % | |||||

| 1 | BD-IPMN | Invasive | GGT → GTT | 16 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → GTT | 17 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A |

| 2 | Invasive | GGT → GTT | 20 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → GTT | 5 | WT | 0 | ||

| 3 | Invasive | GGT → GTT | 3 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → GTT | 8 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | |

| 4 | Invasive | GGT → GTT | 6 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → GTT | 1 | WT | 0 | ||

| 5 | Invasive | GGT → GAT | 11 | CGT → TGT | 15 | RASSF1A | GGT → AGT | 4 | CGT → TGT | 4 | RASSF1A | |

| 6 | MD-IPMN | Invasive | GGT → GAT | 9 | CGT → TGT | 14 | RASSF1A | GGT → GAT | 37 | CGT → TGT | 49 | RASSF1A |

| 7 | Invasive | WT | 0 | WT | 0 |

CDKN2A RASSF1A |

GGC → GAC | 3 | CGT → TGT | 25 | ||

| 8 | Invasive | GGT → GTT | 9 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → GAT | 7 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | |

| 9 | Invasive | GGT → GAT | 4 | CGT → TGT | 39 | GGT → AGT | 4 | CGT → TGT | 5 | RASSF1A | ||

| 10 | Invasive | GGT → GAT | 18 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → TGT | 1 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | |

| 11 | Mixed-IPMN | Invasive | GGT → AGT | 6 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → TGT | 1 | WT | 0 | |

| 12 | HG-IPMN | GGT → GAT | 4 | CGT → TGT | 25 | RASSF1A | GGT → GAT | 3 | CGT → TGT | 19 | RASSF1A | |

| 13 | HG-IPMN | WT | 0 | WT | 0 | RASSF1A | GGT → CGT | 3 | CGT → TGT | 12 |

CDKN2A RASSF1A |

|

Cases with bold letters have concordant KRAS and GNAS sequences between malignant-potential IPMN and A-IPMN dissected regions.

WT, wild type.

RASSF1A hypermethylation was present in four IC-IPMN dissected regions—two in BD-IPMN cases, one in a MD-IPMN case, and one in a mixed IPMN case, in which no hypermethylation existed in comparable A-IPMN dissected regions. No malignant-potential dissected region had a GNAS sequence different from that in a comparable A-IPMN dissected region, and the KRAS sequence was identical. The BRAF mutation, CDKN2A methylation, and LINE-1 methylation status did not differ significantly between the two dissected regions.

Discussion

IPMNs are frequently encountered in clinical practice and are associated with a risk of malignancy. Risk stratification based on radiological characteristics has been proposed5. Research has focused on molecular biomarkers relevant to malignant transformation and clinical characteristics, with a few used in clinical practice. We performed pyrosequencing and IHC analysis of 46 dissected regions (13 IC-IPMN, 5 HG- IPMN, and 28 LG-IPMN including 13 A-IPMN dissected regions) in 33 IPMN cases. IPMN tissue harbors various kinds of dysplasia. Therefore, it is common for pathological studies to choose more than two separate IPMN lesions separately in a given case and genetically analyze all of chosen spots1,13.

Gene mutations and methylation analyzed by pyrosequencing included those for CDKN2A, RASSF1A, LINE1, KRAS, BRAF, and GNAS, which have been investigated in IPMN or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma11,17,37–40. The reason why we used a cut-off value of 10% is because we macrodissected the tissue samples, which included non-tumor cells such as lymphocytes, fibroblasts, and acinar cells. We assume the mixture of a variety of cells would lower the cut-off values of the pyrosequencing compared with other studies and other studies examined RASSF1A methylation or KRAS and GNAS mutations used cut-off values of 10% as well25,26,30. In addition, protein levels of P16, P53, and RASSF1 were examined using IHC28.

Importantly, IPMNs with RASSF1A methylation were detected in 36 of 46 IPMN dissected regions (78%) and were more frequent in malignant-potential IPMN dissected regions than in benign IPMN dissected regions. RASSF1 is a putative tumor suppressor gene that controls tumor growth by inhibiting the RAS pathway41,42 and RASSF1A, one of the seven transcript isoforms of RASSF143, is frequently inactivated via methylation44. RASSF1A hypermethylation was detected in 64% of primary pancreas adenocarcinomas45, similar to our finding of RASSF1A hypermethylation in IPMN cases. There is reportedly an inverse correlation between RASSF1A silencing and KRAS activation45, although we did not obtain such a result. Our data implicate RASSF1A hypermethylation in the malignant transformation of benign IPMN epithelium. Interestingly, two cases of IC-IPMN dissected regions with RASSF1A hypermethylation did not exhibit RASSF1A hypermethylation in A-IPMN dissected regions, but all dissected regions harbored the same KRAS and GNAS mutations. Therefore, RASSF1A hypermethylation may play an important role in the transformation of benign IPMN epithelium. Dissected regions with RASSF1A hypermethylation failed to show an inverse correlation with RASSF1 expression, indicating that other factors—such as gene mutations and methylation of other RASSF1 isoforms—modulate RASSF1 protein synthesis43.

GNAS mutation was positively correlated with the OS of patients with malignant-potential cases. In short, IPMN patients without GNAS mutation had a poor prognosis, consistent with a previous report on 149 IPMN cases among which GNAS mutation was associated with prolonged survival46. Furthermore, GNAS mutation was less frequent in the IC-IPMN dissected regions with perineural or perivascular invasion than in those without, indicating that IC-IPMN without GNAS mutation can be aggressive. Mutations in GNAS at codon 201 have been identified as a hallmark molecular alteration in IPMNs with a prevalence of 66%39 and GNAS mutation is frequent in IPMN-associated adenocarcinoma47,48. Some IPMN cases without GNAS mutation may progress aggressively, which can be associated with other genes.

Genetic and epigenetic alterations inactivating CDKN2A are encountered in many cancers, including pancreatic cancer49. In this study, CDKN2A methylation had neither a prognostic association nor a high frequency in the malignant-potential IPMN cases. However, methylation was significantly more frequent in intestinal-subtype dissected regions, although the histopathologic type of IPMN did not affect the prognosis of malignant-potential IPMN, as a previous study stated46. These findings on CDKN2A methylation have not been reported previously, and further studies to clarify the mechanism and association are needed.

We evaluated the links to global DNA methylation of LINE-1, hypomethylation of which is a common epigenetic alteration in tumor cells50. LINE-1 did not exhibit significant hypomethylation in the IPMN cases and had no clinicopathological significance itself, as reported for pancreatic cancer19. Furthermore, the transpositional activity of LINE-1 is typically silenced by DNA methylation and LINE-1 hypomethylation causes genomic instability, leading to genome-wide mutations, insertions, or deletions50, consistent with the inverse correlation observed between LINE-1 methylation and GNAS mutation. Therefore, LINE-1 methylation may indirectly affect the malignant transformation of IPMN epithelium.

We performed a P53 IHC study instead of focusing on TP53, a tumor suppressor gene that prevents serious DNA damage and carcinogenesis51. P53 is mutated in around 50% of human cancers52. The majority of mutations occur within its central core sequence-specific DNA-binding domain with six hot spots in codons, resulting in the production of conformationally aberrant P53 proteins (mutant P53). TP53 hot-spot mutations account for 30% of those reported53. The most common TP53 mutations not only impair its tumor-suppressor function (loss of function) but also confer novel pro-oncogenic potential on TP53 (gain of function), markedly enhancing tumor progression and drug resistance54. Additionally, P53 IHC positivity is reportedly relevant to the metastasis or prognosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma49,50,55–57 and is associated with the prognosis of pancreatic ductal cancer58. Our data suggest that P53 IHC positivity is associated with malignant transformation of IPMNs, consistent with a previous report59.

We also examined the genetic pathways in two dissected regions from the same case. The dissected material contained a variety of cell types such as lymphocytes, fibroblasts, acinar cells, besides the target IPMN epithelium. Additionally, the proportion of neoplastic content is different and low in samples60, even though their sample sizes are same. However, the study did not compare subtle difference of genetic or epigenetic aberrations between malignant-potential dissected regions, and just compare between malignant-potential and benign dissected regions. Therefore, low neoplastic content did not influence our result that RASSF1A methylation is frequent in malignant-potential IPMN. Based on clonal relations of driver mutations, Omori et al. classified IPMN development into three types: a sequential subtype featuring less diversity in incipient foci with frequent GNAS mutations; a branch-off subtype featuring identical KRAS mutations with different GNAS mutations; and a de novo subtype harboring driver mutations absent from concurrent IPMNs13. Patients with the branch-off subtype had longer disease-free survival compared to those with the other two subtypes13. Our study showed that the BD-IPMN developed via cloning in a sequential manner with concordant sequences of the KRAS and GNAS mutations. This is reasonable because IC-IPMN derived from a BD-IPMN progresses from an IPMN located in a small area of the branch duct independent from the MPD and other branch ducts. By contrast, MD-IPMN or mixed-type IPMN progresses in a large area, including the MPD. Although no other clinicopathological differences were detected according to KRAS or GNAS mutation status, further studies with additional samples might clarify meaningful associations based on the mutation sequences. Furthermore, although all malignant-potential IPMNs in this study initially seemed to be IPMN-derived histologically, 61% of the malignant-potential dissected regions had KRAS sequences different from those of the comparable A-IPMN dissected regions. Because the early acquisition of a KRAS mutation triggers the adenoma-carcinoma sequence12, some malignant-potential IPMNs with different KRAS mutations from the adjacent LG-IPMN may develop into concomitant pancreatic cancer independently of the original IPMN.

This study had several limitations. Macrodissection mixed the extracted DNA of various cells, except the tumor epithelium, resulting in a lower cut-off value for the pyrosequencing analysis. The small number of patients studied might have biased the analyses and prevented multivariate analysis. Moreover, small number of HG-IPMN precluded from showing any statistical significances to identify genetic or epigenetic aberrations in only the pre-malignant lesions. TP53, mutations of which are common in pancreatic cancer, had too many hot spots for pyrosequencing. Therefore, we evaluated P53 expression using IHC. Further studies are necessary to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, we studied several gene mutations and methylation events using pyrosequencing and IHC. Several of the gene aberrations detected may be relevant to cancer development, IPMN subtypes, and cancer prognosis. The findings provide insight into cancer development from an IPMN and will facilitate clinical surveillance and treatment-related decision-making.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Yukimi Itoh, Department of Gastroenterology and Metabolism, Nagoya City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences for helping us to perform IHC staining. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 221S0002 and 16H06279 (PAGS) to Hiromu Suzuki, 19K08449 to Katsuyuki Miyabe, 17K09479 to Itaru Naitoh, and 17H07008 to Akihisa Kato.

Author contributions

G.A. collected participants and samples, conducted the study, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. K.M. planned the study, collected participants and samples, conducted the study, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. H.K. conducted the study and analyzed the data. M.Y. collected participants and samples, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. T.S. and Y.O. analyzed and interpreted the data. H.S., N.A., K.K., A.K., N.J., M.N., Y.H., I.N., K.H. and Y.M. collected participants and samples and revised the manuscript. S.T. conducted the study and revised the manuscript. H.S. conducted the study, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. H.K. supervised the entire study, revised the manuscript, and did the final approval of the version to be submitted.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-04335-z.

References

- 1.Fujii H, et al. Genetic progression and heterogeneity in intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Am. J. Pathol. 1997;151:1447–1454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loftus EV, et al. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas: clinicopathologic features, outcome, and nomenclature. Members of the pancreas clinic, and pancreatic surgeons of Mayo Clinic. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1909–1918. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Longnecker DS. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1995;119:197–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibi Y, et al. Pancreatic juice cytology and subclassification of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2007;34:197–204. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31802dea0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka M, et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738–753. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe Y, et al. The validity of the surgical indication for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas advocated by the 2017 revised International Association of Pancreatology consensus guidelines. Surg. Today. 2018;48:1011–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00595-018-1691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.House MG, Guo M, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Herman JG. Molecular progression of promoter methylation in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) of the pancreas. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:193–198. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Midthun L, et al. Concomitant KRAS and BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2019;10:577–581. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.01.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biankin AV, et al. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia in association with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: Implications for disease progression and recurrence. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004;28:1184–1192. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131556.22382.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amato E, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of cancer genes dissects the molecular profiles of intraductal papillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J. Pathol. 2014;233:217–227. doi: 10.1002/path.4344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren R, et al. Activation of the RAS pathway through uncommon BRAF mutations in mucinous pancreatic cysts without KRAS mutation. Mod. Pathol. 2021;34:438–444. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00647-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanda M, et al. Presence of somatic mutations in most early-stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:730–733. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omori Y, et al. Pathways of progression from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma based on molecular features. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:647–661. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao R, Choi BY, Lee MH, Bode AM, Dong Z. Implications of genetic and epigenetic alterations of CDKN2A (p16(INK4a)) in cancer. EBioMedicine. 2016;8:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Zhang R, Yu J. New understanding of the relevant role of LINE-1 retrotransposition in human disease and immune modulation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:657. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubois F, Bergot E, Zalcman G, Levallet G. RASSF1A, puppeteer of cellular homeostasis, fights tumorigenesis, and metastasis-an updated review. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:928. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2169-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amato E, et al. RASSF1 tumor suppressor gene in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: correlation of expression, chromosomal status and epigenetic changes. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:11. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng DF, et al. DNA methylation of multiple tumor-related genes in association with overexpression of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) during multistage carcinogenesis of the pancreas. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:1160–1168. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamura K, et al. LINE-1 methylation level and prognosis in pancreas cancer: Pyrosequencing technology and literature review. Surg. Today. 2017;47:1450–1459. doi: 10.1007/s00595-017-1539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abe K, et al. Different patterns of p16INK4A and p53 protein expressions in intraductal papillary-mucinous neoplasms and pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Pancreas. 2007;34:85–91. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000240608.56806.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basturk O, et al. A revised classification system and recommendations from the baltimore consensus meeting for neoplastic precursor lesions in the pancreas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015;39:1730–1741. doi: 10.1097/pas.0000000000000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Igarashi S, et al. A novel correlation between LINE-1 hypomethylation and the malignancy of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:5114–5123. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-10-0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toyota M, et al. Epigenetic silencing of microRNA-34b/c and B-cell translocation gene 4 is associated with CpG island methylation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4123–4132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-08-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawada T, et al. Assessment of epigenetic alterations in early colorectal lesions containing BRAF mutations. Oncotarget. 2016;7:35106–35118. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolff EM, et al. RUNX3 methylation reveals that bladder tumors are older in patients with a history of smoking. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6208–6214. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang HJ, et al. Quantitative analysis of cancer-associated gene methylation connected to risk factors in Korean colorectal cancer patients. J. Prev. Med. Public Health. 2012;45:251–258. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2012.45.4.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kinugawa Y, et al. Methylation of tumor suppressor genes in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2017;46:614–618. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0000000000000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto E, et al. Molecular dissection of premalignant colorectal lesions reveals early onset of the CpG island methylator phenotype. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;181:1847–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada M, et al. Frequent activating GNAS mutations in villous adenoma of the colorectum. J. Pathol. 2012;228:113–118. doi: 10.1002/path.4012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pietrantonio F, et al. Toward the molecular dissection of peritoneal pseudomyxoma. Ann. Oncol. 2016;27:2097–2103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ando K, et al. Discrimination of p53 immunohistochemistry-positive tumors by its staining pattern in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2015;4:75–83. doi: 10.1002/cam4.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, et al. Prognostic and predictive role of COX-2, XRCC1 and RASSF1 expression in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma receiving radiotherapy. Oncol. Lett. 2017;13:2549–2556. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwatate Y, et al. Prognostic significance of p16 protein in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2020;13:83–91. doi: 10.3892/mco.2020.2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu B, Ghossein R, Lane J, Lin O, Katabi N. The utility of p16 immunostaining in fine needle aspiration in p16-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 2016;54:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board . Digestive System Tumours, WHO Cassification of Tumours. IARC; 2019. pp. 310–314. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimizu Y, et al. New model for predicting malignancy in patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Ann. Surg. 2020;272:155–162. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodic N, et al. Retrotransposon insertions in the clonal evolution of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat. Med. 2015;21:1060–1064. doi: 10.1038/nm.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitz D, et al. KRAS/GNAS-testing by highly sensitive deep targeted next generation sequencing improves the endoscopic ultrasound-guided workup of suspected mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1002/gcc.22946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu J, et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3:92. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan MC, et al. GNAS and KRAS mutations define separate progression pathways in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm-associated carcinoma. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015;220:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shivakumar L, Minna J, Sakamaki T, Pestell R, White MA. The RASSF1A tumor suppressor blocks cell cycle progression and inhibits cyclin D1 accumulation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:4309–4318. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.12.4309-4318.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dammann R, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of a RAS association domain family protein from the lung tumour suppressor locus 3p21.3. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:315–319. doi: 10.1038/77083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agathanggelou A, Cooper WN, Latif F. Role of the Ras-association domain family 1 tumor suppressor gene in human cancers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3497–3508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-04-4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van der Weyden L, Adams DJ. The Ras-association domain family (RASSF) members and their role in human tumourigenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1776:58–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dammann R, et al. Frequent RASSF1A promoter hypermethylation and K-ras mutations in pancreatic carcinoma. Oncogene. 2003;22:3806–3812. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaujoux S, et al. GNAS but not extended RAS mutations spectrum are associated with a better prognosis in intraductal pancreatic mucinous neoplasms. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019;26:2640–2650. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hosoda W, et al. GNAS mutation is a frequent event in pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and associated adenocarcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2015;466:665–674. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1751-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molin MD, et al. Clinicopathological correlates of activating GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20:3802–3808. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Underwood T. Pan-cancer analysis of whole genomes. Nature. 2020;578:82–93. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1969-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature. 1983;301:89–92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lane DP. Cancer p53, guardian of the genome. Nature. 1992;358:15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991;253:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ozaki T, et al. Impact of RUNX2 on drug-resistant human pancreatic cancer cells with p53 mutations. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:309. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brosh R, Rotter V. When mutants gain new powers: News from the mutant p53 field. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:701–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurahara H, et al. Impact of p53 and PDGFR-β expression on metastasis and prognosis of patients with pancreatic cancer. World J. Surg. 2016;40:1977–1984. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DiGiuseppe JA, et al. Overexpression of p53 protein in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1994;101:684–688. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.6.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang SY, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of p53 expression in human pancreatic carcinomas. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1994;118:150–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yokoyama M, Yamanaka Y, Friess H, Buchler M, Korc M. p53 expression in human pancreatic cancer correlates with enhanced biological aggressiveness. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:2477–2483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Islam HK, et al. Immunohistochemical study of genetic alterations in intraductal and invasive ductal tumors of the pancreas. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:879–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Geiersbach K, et al. Digitally guided microdissection aids somatic mutation detection in difficult to dissect tumors. Cancer Genet. 2016;209:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.