Abstract

Laboratory recovery and confirmation of the etiologic agent in necrotizing retinochoroiditis are problematic. Tissue culture and intraocular antibody titers were compared as adjuncts to clinical diagnosis for toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis: the correlations were 91 and 67%, respectively. Isolation of Toxoplasma gondii may establish a definitive diagnosis in patients with toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis.

Toxoplasma gondii is an ancient, obligate, intracellular parasite with a predilection for central nervous system, skeletal, and intraocular tissues (4, 15, 18, 24–26, 35, 40, 43). Routine diagnosis of congenital or acquired toxoplasmosis is made by serology. For intraocular infection, the diagnosis is clinical, based on symptomatic, active retinochoroiditis recrudescent from a healed chorioretinal scar. Atypical toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis may occur during acquired disease or mimic necrotizing viral retinitis in immunocompromised individuals (4, 9, 25–27, 32–35, 37, 42). Laboratory tests with high positive predictability are desirable in atypical cases to avoid vision loss or delay in diagnosis (1, 6–10, 14, 17, 19, 24, 25, 31–35, 42; D. Miller, E. M. Perez, and M. G. Diaz, unpublished data).

Current laboratory methods for confirmation of toxoplasmosis include (i) direct detection of the parasites in tissues or body fluids by using histological, Giemsa, or immunofluorescence stains or nucleic acid amplification techniques; (ii) isolation of the protozoan in mice or tissue culture; and (iii) investigation of T. gondii anti-immunoglobulin M (IgM), -IgG, -IgA, and -IgE antibodies in serum and intraocular fluids. Sensitivity and specificity may vary greatly between laboratories and applications (6, 11, 15, 18, 19, 28–30, 33–35, 39–43).

We evaluated the usefulness of cell culture isolation to confirm the presence T. gondii in intraocular fluids of patients with a clinical diagnosis of necrotizing retinochoroiditis.

Seventeen intraocular samples were collected from 11 patients from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 1998, during diagnostic vitrectomies or enucleations for atypical, severe retinochoroiditis, and submitted for culture. Monolayers of human fibroblasts (MRC-5; Bartels, Issaquah, Wash.) and, as volume permitted, epitheloid cell lines (A549, Bartels; PMK,VIROMED, Minneapolis, Minn.) were inoculated with 1 to 2 drops (0.1 to 0.2 ml) of intraocular fluids and or tissue mixtures. Cell lines (in tubes) were maintained in 2.5 to 3 ml of prepared tissue culture media supplemented with 3% heat-inactivated fetal calf bovine serum in a CO2 incubator for 30 days or until the detection of cytopathic effect of T. gondii tachyzoites or plaques (7). Spot smears were prepared from tubes with at least 25% cytopathic effect. Positive control slides were prepared as described above from cells lines inoculated with T. gondii ATCC 40050 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.). Negative control smears were prepared from the mock-inoculated tubes.

Four methods were employed to identify and confirm the isolation of T. gondii from tissue culture monolayers. These included (i) direct examination by phase contrast and an inverted microscope at ×20 and ×40; (ii) examination of Giemsa (Hema 3; Biochemical Sciences, Inc., Swedesboro, N.J.)-stained spot smears at ×20 and ×100 under oil immersion, with controls including spot smears prepared from T. gondii ATCC 40050 and uninoculated monolayers; (iii) immunofluorescence detection with an IgG-fluorescein conjugate (Virostat, Portland, Maine) directed against the cell wall of tachyzoites of the RH strain of T. gondii; and (iv) amplification of original samples and culture supernatants of positive patients, with a primer set directed against the B1 gene of T. gondii obtained from Genmed Biotechnologies, Inc. (South San Francisco, Calif.), and performed as previously described (The presence of a 194-bp product signaled a result consistent with the targeted DNA sequences.)

Intraocular antibody (IOAb) titers were determined at the Pathology Reference Laboratory, University of Miami Hospitals and Clinics, Miami, Fla.

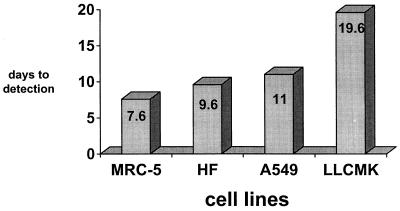

T. gondii tachyzoites were recovered in 7 of the 17 samples (Table 1). Detection time ranged from 2 to 23 days (Fig. 1), with an average of 12 days. Parasites appeared as brightly refringent, 7- to 8-μm, crescent-shaped organisms singularly or in clusters. No viral pathogens were isolated on the initial or subsequent passages. For the five (45%) patients with a final diagnosis of active toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis, the positive predictive value of culture was 100% (5 of 5). The final diagnoses for the remaining patients were lymphoma (two patients), cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis (three patients), and inactive (healed) toxoplasmic infection (one patient). No parasites were isolated from the samples of these patients.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of tissue culture, IOAbs, PCR, and histopathology for confirmation of T. gondii toxoplasmic retinochoroiditisa

| Patient | Sourceb | Result by:

|

Final clinical diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOAb titer | Tissue culture | PCR | |||

| 1 | Vitreous OD | NDc | Negative | ND | Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis |

| Vitreous OS | ND | Positive | Positive | ||

| 2 | Eyewall tissue OD | Positive | Positive | Positive | Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis |

| Vitreous OD (biopsy) | Positive | Positive | |||

| Vitreous wash OD | Positive | Positive | |||

| 3 | Vitreous biopsy OD | Positive | Positive | Positive | Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis |

| 4 | Vitreous biopsy OS | Positive | Positive | Positive | Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis |

| 5 | Eyewall OD | Positive | Negative | ND | Lymphoma |

| Vitreous OD | Negative | ND | |||

| 6 | Vitreous OD | Negative | Negative | ND | CMV retinitis |

| 7 | Vitreous OS | ND | Negative | ND | CMV, Nocardia |

| 8 | Vitreous 1 OD | ND | Negative | Lymphoma | |

| Vitreous 2 OD | ND | Negative | ND | ||

| 9 | Retinal biopsy OD | ND | Negative | ND | CMV retinitis by medical response |

| Vitreous OD | ND | Negative | ND | ||

| 10 | Vitreous OD | Negative | Positive | ND | Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis |

| 11 | Vitreous OD | ND | Negative | ND | Toxoplasmic scars (healed) |

| Correlation with final diagnosis: no. with result/no. tested (%) |

4/6 (67) | 10/11 (91) | 4/4 (100) | ||

The results represent 17 samples from 11 patients.

OD, right eye; OS, left eye. Vitreous 1 and 2 represent two separate samples.

ND, not done.

FIG. 1.

Number of days to detection for recovery of T. gondii in tissue culture.

Antitoxoplasmic IOAbs (IgG) were evaluated for six (54%) patients. The correlation between IOAb titers and final diagnosis was four of six, or 67%.

Titers were positive for three (75%) of the four culture-positive patients screened. We used PCR for confirmation of our T. gondii isolates. Toxoplasmic DNA was found in both the original samples and the cell culture supernatants of all culture-positive patients.

Several reports have confirmed the value of rapid isolation of T. gondii from localized nonocular fluids and tissues and its utility to validate the clinical impression when serological tests were inconclusive (1, 2, 8, 12, 16, 22). Attempts to recover T. gondii from intraocular fluids have been reported. Most of these have been by inoculation of postmortem fluids or enucleated tissues into mice (8, 10, 12, 21, 22). Isolation in mice is considered the “gold standard,” but the technique is cumbersome and time-consuming, and success is impacted by variable susceptibility of the mice, virulence of the infecting parasite, and the route and dose of the inoculum. Deouin and coworkers found the sensitivity of tissue culture to be equivalent to that of mice for inocula of 1 to 100 parasites (13).

Our results provide the first report of routine detection of T. gondii in intraocular fluids in patients with necrotizing retinochoroiditis due to T. gondii. All culture-positive results were from human immunodeficiency virus-positive or AIDS patients. Our average detection time of 12 days is longer than the recovery times reported in the literature for detection of T. gondii in cases of encephalitis or parasitemia (3, 22, 36, 38). This may be due in part to the volume of sample (0.1 to 0.5 ml) and in part because tubes, rather than shell vials or microtiter plates, were used for detection.

T. gondii DNA was also confirmed by PCR in the intraocular fluids from all culture-positive cases. PCR has been used to detect Toxoplasma antigens in tissues and fluids of patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis and pulmonary and congenital disease (7, 12, 20, 23). Others have investigated direct detection in ocular tissues and fluids (2, 5; D. Miller, J. L. Davis, W. W. Culbertson, S. C. Pflugfelder, and D. Nicholson, Clin. Virol. Symp., abstract, 1993). In a series of 300 aqueous humor samples, Dupon and coworkers found that the sensitivity of the technique was limited, in part due to the small volume (0.1 to 0.2 ml) (16).

One limitation of this study is the small number of patients. Since only patients with severe necrotizing retinochoroiditis were included, patients with less severe disease might be less likely to have positive cultures. However, patients with less severe disease rarely need adjunctive testing. Culture of intraocular fluids and tissues appears to be a highly effective means of diagnosis in patients with severe, atypical necrotizing retinochoroiditis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A M. Comparative study of methods used for the isolation of Toxoplasma gondii. Bull W H O. 1967;36:344–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aouizerate J, Cazenave J, Poirier L, Verin P, Cheyrou A, Begueret J, Lagoutte F. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii in aqueous humor by the polymerase chain reaction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:107–109. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.2.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asensi V, Carton J A, Maradona J A, Ona M, Arribas J M. Clinical value of blood cultures for detection of Toxoplasma gondii in human immunodeficiency virus seropositive patients with and without cerebral lesions or computerized tomography. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:511–512. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaman M H, McCabe R E, Wong S Y, Remington J S. Toxoplasma gondii. In: Mandell G L, Bennett J E, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 2455–2475. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brezin A P, Egwuagu C E, Silveria C, Thulliez P, Martins M C, Mahdi R M, Belfort R, Jr, Nussenblatt R B. Analysis of aqueous humor in ocular toxoplasmosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brezin A P, Egwuagu C E, Brunier M, Silveria C, Mahdi R M, Gazzinelli R T, Belfort R, Jr, Nussenblatt R B. Identification of Toxoplasma gondii in paraffin-embedded sections by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;110:599–604. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burg J L, Grover C M, Pouletty P, Boothroyd J C. Direct and sensitive detection of a pathogenic protozoan, Toxoplasma gondii, by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1787–1792. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.8.1787-1792.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang C H C, Stulberg C, Bollinger M S, Walker R, Brough A J. Isolation of Toxoplasma gondii in tissue culture. J Pediatr. 1972;81:790. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(72)80106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochereau-Massin I, LeHoang P, Lautier-Frau M, Zerdoun E, Zazoun L, Robinet M, Marcel P, Girard B, Katlama C, Leport C, Rozenbaum W, Coulaud J P, Gentilini M. Ocular toxoplasmosis in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:130–135. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73975-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Contini C, Roman R, Magno S, Delia S. Diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection in AIDS patients by tissue culture technique. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:434–440. doi: 10.1007/BF02114900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis J L, Feur W, Culbertson W W, Pflugfelder S C. Interpretation of intraocular and serum antibody levels in necrotizing retinitis. Retina. 1995;15:233–240. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199515030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Derouin F, Mazeron M C, Garin Y J F. Comparative study of tissue culture and mouse inoculation methods for demonstration of Toxoplasma gondii. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:1597–1600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.9.1597-1600.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Derouin F, Sarfati C, Beauvais B, Iliou M-C, Dehen L, Lariviere M. Laboratory diagnosis of pulmonary toxoplasmosis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1661–1663. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.7.1661-1663.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desmonts G. Definitive serological diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;76:839–851. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1966.03850010841012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubey J P, Lindsay D S, Speer C A. Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and biology and development of tissue cysts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:267–299. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dupon M, Cazenave J, Pellegrini J-L, Ragnaud J-M, Cheyrou A, Fischer I, Leng B, Lacut J-Y. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii by PCR and tissue culture in cerebrospinal fluid and blood of human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2421–2426. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2421-2426.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elkins B S, Holland G N, Opremcak E M, Dunn J P, Jr, Jabs D A, Johnston W H, Green W R. Ocular toxoplasmosis misdiagnosed as cytomegalovirus retinopathy in immunocompromised patients. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagliuso D J, Teich S A, Friedman A H, Orellana J. Ocular toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1990;88:63–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross V, Roggenkamp A, Janitschke K, Heeseman J. Improved sensitivity of the polymerase chain reaction for detection of Toxoplasma gondii in biological and human clinical specimens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:33–39. doi: 10.1007/BF01971268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover C M, Thulliez P, Remington J S, Boothroyd J C. Rapid prenatal diagnosis of congenital Toxoplasma infection by using polymerase chain reaction and amniotic fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2297–2301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.10.2297-2301.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinemann M H, Gold J M W, Maisel J. Bilateral toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis in a patient with AIDS. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:571–575. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050160127028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hofflin J M, Remington J S. Tissue culture isolation of toxoplasma from blood of a patient with AIDS. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:925–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohlfeld P, Daffos F, Costa J M, Thulliez P, Forestier F, Vidaud M. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis with a polymerase-chain-reaction test on amniotic fluid. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:695–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409153311102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland G N. Ocular toxoplasmosis in the immunocompromised host. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:399–402. doi: 10.1007/BF02306488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holland G N, Engstrom R E, Jr, Glasgow B J, Berger B B, Daniels S A, Sidikaro Y, Harmon J A, Fischer D H, Boyer D S, Rao N A, Eagle R C, Jr, Kreiger A E, Foos R Y. Ocular toxoplasmosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:653–667. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90697-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holland G N, O'Connor R, Jr, Belfort R, Remington J S. Toxoplasma. In: Pepose J S, Holland G N, Wilhelmus K R, editors. Ocular infection and immunity. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1996. pp. 1183–1223. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson M W, Greven G M, Jaffe G S, Sudhalkar H, Vine A K. Atypical, severe, toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis in elderly patients. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:48–57. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karim K A, Ludlam G B. The relationship and significance of antibody titers as determined by various methods in glandular and ocular toxoplasmosis. J Clin Pathol. 1975;28:42–49. doi: 10.1136/jcp.28.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kijlstra A, Luyendijk L, Baarsma G S, Rothova A, Schweitzer C M C, Timmerman Z, de Vries J, Breebaart A C. Aqueous humor analysis as a diagnostic tool in toxoplasma uveitis. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;1:383–386. doi: 10.1007/BF02306485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kijlstra A, van Den Horn G J, Luyendijk L, Baarsma G S, Schweitzer C M C, Zaal M J M, Timmerman Z, Beintema M, Rothova A. Laboratory tests in uveitis: new developments in the analysis of local antibody production. Doc Ophthalmol. 1990;75:225–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00164835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis M L, Culbertson W W, Post M J D, Miller D, Kokame G T, Dix R D. Herpes simplex virus type 1: a cause of the acute retinal syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:875–878. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32823-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morinelli E N, Dugel P U, Lee M. Opportunistic intraocular infections in AIDS. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1992;90:97–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nussenblatt R B, Belfort R. Ocular toxoplasmosis: an old disease revisited. JAMA. 1994;271:304–307. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.4.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parke D W, Font R L. Diffuse toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis in a patient with AIDS. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:571–575. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050160127028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothova A, Kijlstra A. Toxoplasma, recent developments, therapy and prevention. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:369–370. doi: 10.1007/BF02306482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shepp D H, Hackman R C, Conley E K, Anderson J B, Meyers J D. Toxoplasma gondii reactivation identified by detection of parasitemia in tissue culture. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:218–221. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-2-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith R E. Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis as an emerging problem in AIDS patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:738–739. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90711-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tirard V, Neil G, Rosenheim M, Katlama C, Ciceron L, Ogunkolade W, Davis M, Gentilini M. Diagnosis of toxoplasmosis in patients with AIDS by isolation of the parasite from the blood. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:634. doi: 10.1056/nejm199102283240914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Turunen H J, Leinikki P O, Saari K M. Demonstration of intraocular synthesis of immunoglobulin G antibodies for specific diagnosis of toxoplasmic chorioretinitis by enzyme immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;17:988–992. doi: 10.1128/jcm.17.6.988-992.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Knapen F. Toxoplasmosis, old stories and new facts. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:371–375. doi: 10.1007/BF02306483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Loon A M. Laboratory diagnosis of toxoplasmosis. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:377–381. doi: 10.1007/BF02306484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss A, Margo C E, Ledford D K, Lockey R F, Brinser J H. Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis as an initial manifestation of the acquired deficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101:2248–2249. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90605-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson M, McAuley J B. Toxoplasma. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 1374–1382. [Google Scholar]