Abstract

Accumulation of misfolded proteins such as amyloid-β (Aβ), tau, and α-synuclein (α-Syn) in the brain leads to synaptic dysfunction, neuronal damage, and the onset of relevant neurodegenerative disorder/s. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) are characterized by the aberrant accumulation of α-Syn intracytoplasmic Lewy body inclusions and dystrophic Lewy neurites resulting in neurodegeneration associated with inflammation. Cell to cell propagation of α-Syn aggregates is implicated in the progression of PD/DLB, and high concentrations of anti-α-Syn antibodies could inhibit/reduce the spreading of this pathological molecule in the brain. To ensure sufficient therapeutic concentrations of anti-α-Syn antibodies in the periphery and CNS, we developed four α-Syn DNA vaccines based on the universal MultiTEP platform technology designed especially for the elderly with immunosenescence. Here, we are reporting on the efficacy and immunogenicity of these vaccines targeting three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn aa85–99 (PV-1947D), aa109–126 (PV-1948D), aa126–140 (PV-1949D) separately or simultaneously (PV-1950D) in a mouse model of synucleinopathies mimicking PD/DLB. All vaccines induced high titers of antibodies specific to hα-Syn that significantly reduced PD/DLB-like pathology in hα-Syn D line mice. The most significant reduction of the total and protein kinase resistant hα-Syn, as well as neurodegeneration, were observed in various brain regions of mice vaccinated with PV-1949D and PV-1950D in a sex-dependent manner. Based on these preclinical data, we selected the PV-1950D vaccine for future IND enabling preclinical studies and clinical development.

Subject terms: Parkinson's disease, DNA vaccines

Introduction

In Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) patients, aggregated human α-synuclein (hα-Syn) accumulates in the neuronal soma1–5 and throughout axons6 and synapses7–10 affecting the neocortex, limbic structures, striatonigral system, and peripheral autonomic neurons. In contrast to this, in patients with multiple system atrophy (MSA), hα-Syn accumulates primarily in oligodendroglia, although aggregated forms of this misfolded protein are also detected within neurons and astrocytes1,11–13. While MSA is a rare disease, currently in the USA, over 1 million people are living with disorders associated with PD/DLB, and yearly ~60,000 new cases are identified. Today, medications may help control some symptoms of PD/DLB, but only a few treatments have been developed with the disease-modifying potential so far14–16.

The era of vaccination against neurodegenerative disorders was initiated over 20 years ago when Schenk’s group reported on effective clearance of extracellular amyloid pathology after immunizations of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with fibrillar beta-amyloid peptide (Aβ42) formulated in Th1 type QS-21 adjuvant17,18. Active and passive immunotherapeutic strategies targeting various misfolded proteins involved in different neurodegenerative diseases, including DLB, PD, and MSA disorders, have been pursued after that seminal study19–29. These published data suggested that a sufficient concentration of antibodies specific to aggregated proteins could be viable for targeting extracellular and intracellular pathological molecules involved in the appropriate neurodegenerative disorders. More specifically, we showed that vaccinations of hα-Syn Tg D line mice, mimicking certain aspects of PD/DLB with full-length recombinant hα-Syn protein, induced therapeutically potent antibodies capable of reducing intracellular toxic hα-Syn aggregates. Importantly, we identified four B-cell epitopes spanning amino acids 85–99, 109–123, 112–126, and 126–138 of hα-Syn20,22,30 that have been used for the generation of vaccines and monoclonal antibodies (mAb) for the treatment of PD, DLB, and MSA. For example, it was reported that administration of mAb specific to aa118–126 of hα-Syn (9A4) reduced neurological deficits and improved behavior of Tg D line (aka PDGFβ-α-Syn) mice31, while two other mAb (1H7 and 5D12) mitigated neurodegeneration in the line 61 mice (aka Thy1-α-Syn)32. Later it was shown that short peptide mimicking aa sequence 110–130 of hα-Syn attached to Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin carrier formulated in Alum adjuvant, induced therapeutically potent antibodies in these two mouse models of PD/DLB. In addition, this vaccine decreased the accumulation of hα-Syn, reduced demyelination in the neocortex, striatum, and corpus callosum, and reduced neurodegeneration (improve motor and memory functions) in MBP-α-Syn Tg mice mimicking MSA20,22,31–33. Based on these preclinical data AFFiRiS developed PD01A and PD03A vaccines based on short peptides mimicking amino acid sequence at the C-terminus of hα-Syn22,33,34. Both vaccines were tested in Phase 1 trials in the MSA patients35 and patients with a clinical diagnosis of PD36,37.

PD01A was more immunogenic in both MSA and PD patients. In PD patients, immunizations induced anti-PD01 antibodies with median titer equal to 1:3580 in Study 1, which reached 1:20,000 when patients were boosted after a 91week period (Study 2). However, mean titers of antibodies specific to α-Syn were lower, reaching 1:330 and 1:4209, after Study 1 and Study 2, respectively.

In sum, anti-hα-Syn immunotherapies reduced the accumulation of pathological α-Syn in axons and synapses and alleviated motor and learning deficits in various models of α-synucleinopathies20,22,31–33. The pathway for antibody-mediated reduction of intracellular pathological molecules such as hα-Syn involves multiple mechanisms28,38,39, including (i) microglial mediated clearance22,40, (ii) degradation via endosomal-lysosomal system31,41, (iii) reduction of protein aggregation42, (iv) blocking aggregation through the binding to C-terminally truncated forms that are stimulating α-syn aggregation43, (v) induction of degradation via the proteasome19,44; and (vi) blockage of transsynaptic propagation23,45. Multiple published data demonstrated that intracellular pathological proteins, such as hα-Syn, can transmit from cell to cell in a prion-like fashion46–51. Therefore, an immunogenic vaccine that can generate substantial titers of antibodies targeting these pathological forms of hα-Syn could inhibit/block its propagation from cell to cell and delay the progression of diseases related to synucleinopathies20,29,31,40.

Previously, using already identified B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn20,30, we have developed four DNA vaccines, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D30, based on universal and immunogenic MultiTEP platform technology52–55. Three DNA vaccines target individual B-cell antigenic determinants of hα-Syn spanning aa85–99 (PV-1947D), aa109–126 (PV-1948D), aa126–140 (PV-1949D), while the last one (PV-1950D) targets all these B-cell epitopes simultaneously. Immunizations of wild-type mice with these vaccines induced high titers of anti-hα-Syn antibodies and robust T helper (Th) cell responses specific to the MultiTEP vaccine platform without activating potentially detrimental autoreactive Th cells that recognize hα-Syn self-protein30. The main objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of antibodies generated by these vaccines targeting the above-mentioned B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn in a mouse model of PD/DLB and to select the most effective epitopes for the development of PD/DLB vaccine for the future preclinical IND enabling studies.

Results

Immunogenicity of PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccines in a mouse model of synucleinopathies

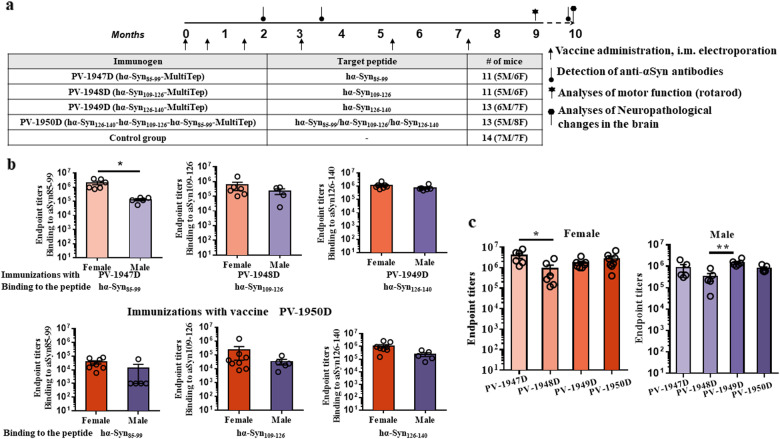

The hα-Syn D line was selected for this study because of the early and progressive accumulation of insoluble hα-Syn accompanied by motor deficits in these mice56–58. First, we tested the immunogenicity of all DNA vaccines by assessing endpoint titers of antibodies specific to peptides representing the appropriate B-cell epitope of hα-Syn (Fig. 1a). Intramuscular immunizations of mice with PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D vaccines followed by electroporation (EP) induced strong humoral immune responses (Fig. 1b) in all mice regardless of the sex after three boosts and then maintained the same antibody titers during subsequent two administrations. Of note, these antibodies are specific to only peptides representing the B-cell epitope of hα-Syn incorporated in the construct (Fig. 1b, upper panel), i.e., no cross-reactive antibodies were detected. On the contrary, mice immunized with the PV-1950D vaccine generated antibodies recognizing three peptides representing all three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn (Fig. 1b, lower panel). Interestingly, we detected a higher titer of antibodies specific to B-cell epitope spanning aa126–140 followed by antibodies specific to aa109–126, while titers of antibodies recognizing aa85–99 peptide were lowest (Fig. 1b, lower panel).

Fig. 1. PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D induced high titers of antibodies specific to appropriate peptide/s and full-length α-Syn in α-Syn/Tg D line mice.

a Design of experimental protocol in hα-Syn Tg D line mice vaccinated with various MultiTEP-based DNA immunogens targeting different epitopes of hα-Syn. Mice were 2.5–4.5 mo of age at the start and 12–14 months old at the end of the experiment. b Endpoint titers of antibodies specific to hα-Syn85–99, hα-Syn109–126, and hα-Syn126–140 peptides were detected in sera collected after the fourth immunization with indicated immunogens by ELISA. Error bars indicate the mean values of antibody titers ± SEM (*p < 0.05). PV-1950D induced higher responses to epitopes aa109–126 (p < 0.05 for female and male mice) and aa126–140 (p < 0.01 for female mice and p < 0.05 for male mice) compared with the epitope aa85–99. c Antibody titers of antibodies specific to recombinant full-length α-Syn. Titers were significantly higher in PV-1947D vs. PV-1948D (p < 0.05) in female and PV-1949D vs. PV-1948D (p < 0.01) male mice groups. Error bars indicate the mean values of antibody titers ± SEM.

Importantly, all four DNA vaccines in D line mice induced high titers of antibodies specific to full-length hα-Syn (Fig. 1c). However, in general, the immunizations of female mice resulted in the production of slightly higher anti-hα-Syn antibodies than those detected in male mice (Fig. 1c).

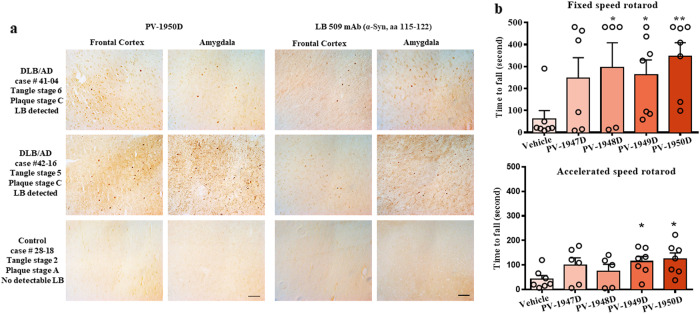

Previously, we reported that antibodies generated in wild-type mice immunized with PV-1950D recognized LB in the brain sections from several DLB cases30. In this study, we analyzed the binding of IgG antibodies purified from sera of mice vaccinated with the PV-1950D to the frontal cortex and amygdala (Amy) sections of brains from DLB/AD combined pathology cases (case #42-16 and #41-04) characterized at UCI Brain Bank and Tissue Repository (see Methods section). The data had demonstrated that antibodies recognized pathological α-Syn in the frontal cortex and Amy regions of the brains from DLB/AD cases (Fig. 2a). As expected, antibodies specific to three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn did not stain control brain sections.

Fig. 2. Anti-hα-Syn antibodies induced by PV-1950 recognized LBs in the brains from DLB/AD cases and improve motor function of hα-Syn/Tg D line mice.

a Representative images of the frontal cortex and amygdala sections from two DLB/AD cases stained with antibodies generated by PV-1950D and anti-αSyn commercial antibodies LB509. Magnification ×20, scale bar 50 μm. b Motor skills of female mice were tested in Fixed speed rotarod and accelerated speed rotarod. Statistical significance is calculated using an unpaired t-test. Due to high body weight and clumsiness, male mice were excluded from the behavior tests. Error bars indicate the mean values ± SEM.

Anti-ha-Syn antibodies improved motor deficits in an immune mouse model of PD/DLB

Previously, it was shown that the D line mouse model of PD/DLB shows an early and progressive accumulation of hα-Syn accompanied by motor deficits57. To ensure that antibodies specific to various B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn generated after administering mice with appropriate DNA vaccines can reduce age-associated motor deficits, we tested mice in a widely used rotarod test. The D line female mice immunized with PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D ran significantly longer on a fixed rotarod than control nonimmune mice (Fig. 2b). However, the efficacy of antibodies specific to all three hα-Syn B-cell epitopes induced by PV-1950D was more profound (p < 0.05 for PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and p < 0.01 for PV-1950D). In the accelerated test, significant changes in the duration of stay on a rod were observed in aged D line female mice immunized with PV-1949D and PV-1950D compared with control animals (p < 0.05, Fig. 2b). These findings suggest that PV-1950D is the most effective DNA vaccine that improved motor deficits in a mouse model of PD/DLB producing antibodies recognizing all three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn simultaneously.

We should mention that our attempt to test male D line aged mice in rotarod tests was not successful. These mice of all vaccinated and control groups could not stay on the rod and fell after 2–3 s, probably because of their high weight. Interestingly, these data coincide with published results demonstrating that D line male mice perform worse than female mice, slipping more often during the challenging beam walk test than females57.

The therapeutic efficacy of antibodies specific to three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn in a mouse model of PD/DLB

To confirm that the improvement of motor deficits is associated with the reduction of neuropathology, we analyzed the efficacy of all DNA vaccines in 12–14 months old D line mice that develop an age-dependent progressive accumulation of α-Syn56,57. For this purpose, we performed a comprehensive neuropathological analysis with various antibodies (α-Syn, GFAP, Iba1, NeuN, and TH) in multiple brain regions [neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and S. Nigra (SN)] in mice divided by sex (male and female).

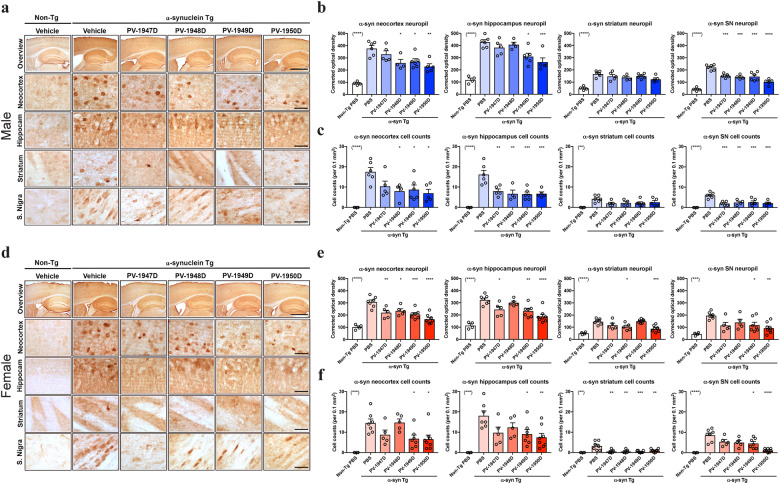

We first analyzed α-Syn neuropathology in the mice utilizing the Syn1 antibody against total α-syn (mouse and human). More specifically, we analyzed levels of immunoreactivity in the neuropil (corrected optical density), reflecting the levels of α-Syn in the nerve terminals and α-Syn-positive aggregates in neuronal cell bodies. In the neocortex of male mice, immunization with PV-1948D (p < 0.05), PV-1949D (p < 0.05), and PV-1950D (p < 0.01) but not with PV-1947D reduced levels of α-Syn immunoreactivity in the neuropil, while in the hippocampus immunization with PV-1949D (p < 0.05) and PV-1950D (p < 0.001) was most effective, in contrast to only minimal or no effect observed in the striatum neuropil. Nonetheless, in the SN, all vaccines reduced levels of α-Syn in the neuropil (p < 0.001 for PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and p < 0.0001 for PV-1950D) (Fig. 3a, b). Numbers of α-Syn-positive aggregates in neuronal cell bodies were also reduced in the neocortex of male mice immunized with PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D (all p < 0.05), but not PV-1947D. At the same time, while in the hippocampus and SN, all four vaccines reduced α-Syn-positive aggregates (from p < 0.01 to p < 0.001), no effects were observed in the striatum (Fig. 3a, c). In the neocortex of female mice α-Syn immunoreactivity in the neuropil was decreased by immunization with all four vaccines [PV-1947D (p < 0.01), PV-1948D (p < 0.05), PV-1949D (p < 0.001) and PV-1950D (p < 0.0001)], while in the hippocampus PV-1947D (p < 0.05), PV-1949D (p < 0.01) and PV-1950D (p < 0.0001) were most effective. In the striatum, PV-1948D (p < 0.05) and PV-1950D (p < 0.001) had a modest effect in the neuropil, while in the SN of mice immunized with PV-1949D (p < 0.05) and PV-1950D (p < 0.0001) reduced levels of α-syn in the neuropil was observed (Fig. 3d, e). Numbers of α-syn-positive aggregates in neuronal cell bodies were also reduced in the neocortex and hippocampus of female mice immunized with PV-1949D (p < 0.05) and PV-1950D (p < 0.01), while in the striatum, all four vaccines reduced α-syn-positive aggregates (p < 0.01 for PV-1947D, PV-1948D and PV-1950D; p < 0.001 for PV-1949D). Immunizations with only PV-1949D (p < 0.05) and PV-1950D (p < 0.0001) reduced α-Syn-positive aggregates in the SN of female mice (Fig. 3d, f). In summary, mostly PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D reduced accumulation of α-syn-in the neuropil and neurons with PV-1950D more effective, the effects on total α-syn were more prominent in male than in female mice (Table 1).

Fig. 3. Vaccination with MultiTEP-based anti-αSyn vaccines significantly reduced the accumulation of total α-synuclein in D line transgenic mice.

a Representative images of male mice brain sections immunostained with the antibody against total αSyn (Syn1) from top to bottom panels include an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra region in non-Tg and hαSyn Tg mouse treated with vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D. b Image analysis of αSyn in the neuropil expressed as mean corrected optical density in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) in male mice. c Image analysis of αSyn-positive cell counts per 0.1 mm2 in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) in male mice. d Representative images of brain sections from female mice immunostained with the Syn1 antibody, panels from top to bottom illustrate an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and hαSyn Tg mouse treated with vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. e Image analysis of αSyn in the neuropil expressed as mean corrected neuropil optical density in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) in female mice. f Image analysis of αSyn-positive cell counts per 0.1 mm2 in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) in female mice. The scale bar in the overview is 250 µm, the others are 25 µm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Table 1.

Neuropathological changes in brain regions of vaccinated and control hαSyn-tg D line mice.

| α-Syn-tg male | α-Syn-tg female | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Tg PBS | PBS | PV-1947D | PV-1948D | PV-1949D | PV-1950D | nonTg PBS | PBS | PV-1947D | PV-1948D | PV-1949D | PV-1950D | ||

| syn1 optical density | Neocortex | + | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Hippocampus | ++ | +++++ | ++++ | +++++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | ++ | |

| Striatum | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | |

| Substantia nigra | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | |

| syn1 cell count | Neocortex | − | +++++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | − | ++++ | +++ | ++++ | ++ | ++ |

| Hippocampus | − | ++++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | − | +++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | |

| Striatum | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | |

| Substantia nigra | − | ++ | + | + | + | + | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | |

| syn1 PK optical density | Neocortex | + | ++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | + | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ |

| Hippocampus | + | +++++ | ++++ | +++++ | ++++ | +++++ | + | +++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | |

| Striatum | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Substantia nigra | + | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| syn1 PK cell count | Neocortex | − | +++ | + | + | + | + | − | +++ | + | + | ++ | ++ |

| Hippocampus | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Striatum | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Substantia nigra | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | |

| NeuN | Neocortex | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Hippocampus | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | |

| Striatum | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Substantia nigra | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| GFAP | Neocortex | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Hippocampus | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Striatum | + | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Substantia nigra | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | |

| Iba1 | Neocortex | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Hippocampus | +++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | +++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Striatum | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| Substantia nigra | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | |

| TH | Striatum | +++++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Substantia nigra | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | +++++ | |

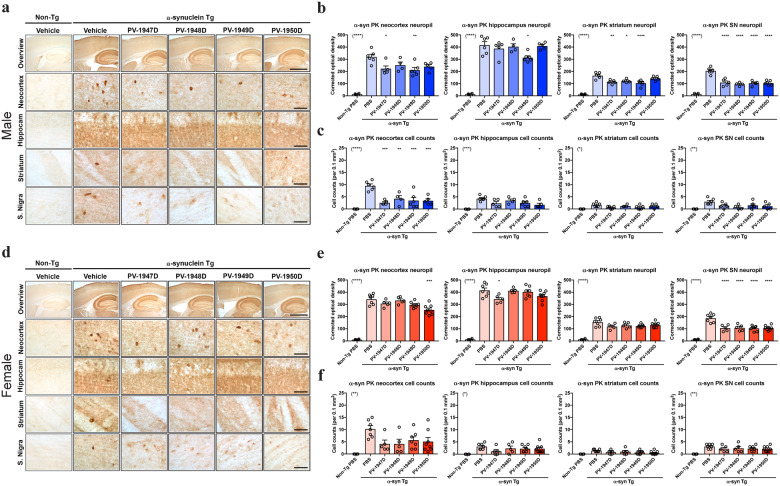

Next, we investigated the effects of the DNA vaccines on levels of pathological α-Syn by analyzing levels of proteinase K (PK)-resistant α-Syn aggregates in the neuropil and neuronal cell bodies59. In the neocortex of male mice, levels of PK-resistant α-syn immunoreactivity in the neuropil were decreased by vaccinations with PV-1947D (p < 0.05) and PV-1949D (p < 0.01) but not with PV-1948D and PV-1950D, while in the hippocampus immunization with PV-1949D (p < 0.05) was most effective (Fig. 4a, b). In contrast, PK-resistant α-Syn was reduced in the striatum of mice immunized with PV-1947D (p < 0.01), PV-1948D (p < 0.05), and PV-1949D (p < 0.0001), and in SN neuropil of mice immunized with all four DNA vaccines (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4a, b). The numbers of PK-resistant α-Syn-positive aggregates in neuronal cell bodies were also reduced in the neocortex of male mice by all four DNA vaccines [PV-1947D (p < 0.001), PV-1948D (p < 0.01), PV-1949D (p < 0.001), and PV-1950D (p < 0.001)], while in the hippocampus only PV-1950D (p < 0.05) reduced SN PK-resistant α-Syn in neurons (Fig. 4a, c). No effects were observed with either of the four DNA vaccines in the striatum or SN of the male mice (Fig. 4a, c). The immunoreactivity of PK-resistant neuropil α-Syn was decreased in the neocortex of female mice immunized with only PV-1950D (p < 0.001) and in the hippocampus of female mice immunized with only PV-1947D (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4d, e). Although the immunizations with all four DNA vaccines did not reduce PK-resistant α-Syn level in the striatum, it significantly reduced levels of this pathological molecule in SN neuropil (p < 0.0001) of female mice (Fig. 4d, e). The numbers of PK-resistant α-Syn-positive aggregates in neuronal cell bodies were not significantly reduced in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, or SN of female mice (Fig. 4d, f). In summary, immunizations with PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D modestly reduced the accumulation of PK-resistant α-Syn in the neocortex and SN, and these effects were more prominent in male than in female mice (Table 1). As a side note, we did not observe any differences between control and vaccinated mice when hα-syn was measured by ELISA in total half-brain homogenates as well as in cytosolic and particulate fractions. These discrepancies between IHC and biochemical data are likely associated with the analyses of individual brain regions in IHC and entire half-brain homogenates in the case of biochemistry.

Fig. 4. Vaccination with MultiTEP-based DNA vaccines significantly reduced the accumulation of PK-resistant α-synuclein in transgenic mice.

a Representative images of brain sections from male mice pretreated with proteinase K (PK) and immunostained with an antibody against α-synuclein. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and hαSyn Tg mice treated with vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. b Image analysis of PK-resistant αSyn in the neuropil expressed and corrected optical density in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) in male mice. c Image analysis of PK-resistant αSyn-positive cell counts per 0.1 mm2 in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) of male mice. d Representative images of brain sections from female mice pretreated with PK and immunostained with an antibody against α-synuclein. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mouse treated with vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. e Image analysis of PK-resistant αSyn in the neuropil expressed as optical density in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) in female mice. f Image analysis of αSyn cell counts per 0.1 mm2 in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra (from left to right) in female mice. The scale bar in the overview is 250 µm, the others are 25 µm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

We have previously shown that in the D line mouse model, the accumulation of hα-Syn is associated with the loss of neurons in the deeper layers of the neocortex and CA3 of the hippocampus and loss of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) fibers in the striatum that reflects dopaminergic neuron loss60. Therefore, we investigated whether immunizations with DNA vaccines ameliorated neurodegeneration in Tg hα-Syn D line mice (Figs. 5 and 6).

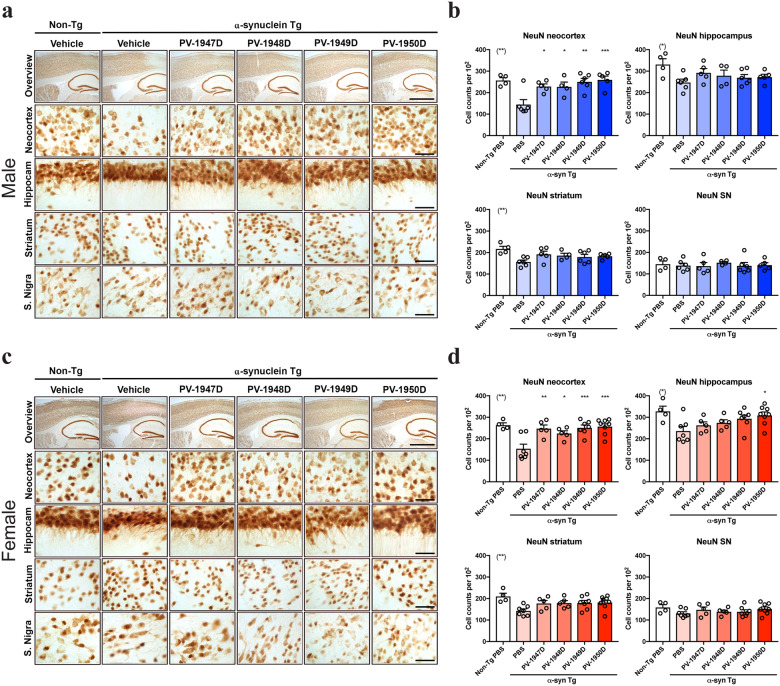

Fig. 5. Vaccination with MultiTEP-based DNA vaccines significantly ameliorated the loss of neurons in hα-Syn Tg mice.

a Representative images of male mice of immunostained with the pan-neuronal marker-NeuN. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mouse treated with vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. b Image analysis of NeuN-positive neuronal cell count per 102 in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra of male mice. c Representative images of female mice immunostained with the pan-neuronal marker-NeuN. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mice with the vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. d Image analysis of NeuN-positive neuronal cell counts per 102 in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra in female mice. The scale bar in the overview is 250 µm, the others are 25 µm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

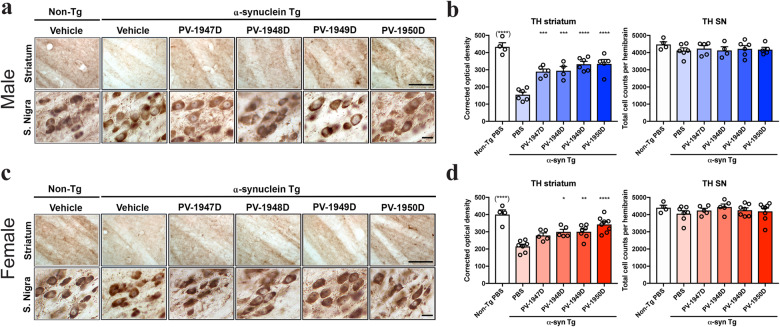

Fig. 6. Vaccination with MultiTEP-based DNA vaccines significantly ameliorated the loss of TH fibers in hα-Syn Tg mice.

a Representative images of brain sections from male mice immunostained with an antibody against the dopamine cell marker tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). From top to bottom, each panel illustrates the striatum and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mouse with the vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. b Image analysis of TH-positive fibers expressed as corrected optical density in the striatum and total TH-positive cell counts per midbrain in substantia nigra of male mice. c Representative images of brain sections of female mice of immunostained with an antibody against TH. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom the striatum and substantia nigra in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mouse with a vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. d Image analysis of TH-positive fibers expressed as corrected optical density in striatum and total TH-positive cell counts per midbrain in substantia nigra of female mice. The scale bar is 100 µm for Striatum and 10 µm for S. Nigra. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

With an antibody against the pan-neuronal marker NeuN, compared to male non-Tg controls, the vehicle-treated male Tg hα-Syn mice showed a 44% loss in neurons of the neocortex. In contrast, neuronal counts in the neocortex of immunized male mice were significantly higher than that in control hα-Syn-Tg mice [PV-1947D (p < 0.05), PV-1948D (p < 0.05), PV-1949D (p < 0.01), and PV-1950D (p < 0.001)] and were comparable to non-Tg controls (Fig. 5a, b). In the hippocampus and striatum of the male hα-syn-Tg mice, there was a mild 26% loss of neurons compared to non-Tg mice. Immunization with the DNA vaccines showed a trend toward normalization that was not significant. No loss of neurons or effects of the DNA vaccines were detected in the SN (Fig. 5a, b). Likewise, compared to the female non-Tg controls, the vehicle-treated female Tg hα-syn mice showed a 50% loss in neurons in the neocortex. In contrast, immunized female mice showed comparable to non-Tg controls neuronal counts that were significantly higher [PV-1947D (p < 0.01), PV-1948D (p < 0.05), PV-1949D (p < 0.001), and PV-1950D (p < 0.001)] than in female Tg hα-Syn mice (Fig. 5c, d). In the hippocampus of the female α-syn-Tg mice, there was a moderate 35% loss of neurons compared to non-Tg mice. Immunization with the PV-1950D vaccine targeting all three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn was the most effective (p < 0.05) at ameliorating neurodegeneration in the hippocampus of these mice (Fig. 5c, d). In the striatum, there was a mild 20% loss of neurons with a trend toward normalization with immunization that was not significant. No loss of neurons or effects of the DNA vaccines were detected in the SN of female mice (Fig. 5c, d). In summary, immunization with PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D ameliorated the loss of neurons in the neocortex with PV-1950D more effectively. Of note, the effects of the vaccination were more prominent in the female mice than the male (Table 1).

Regarding the striatonigral dopaminergic system, compared to male non-Tg controls, the vehicle-treated male hα-Syn-Tg mice showed a 65% loss of TH-positive fibers in the striatum. The density of TH-positive fibers is significantly higher in mice immunized with PV-1947D (p < 0.001), PV-1948D (p < 0.001), PV-1949D (p < 0.0001), and PV-1950D (p < 0.0001), and it is comparable to non-Tg controls. We did not detect any loss of neurons or effects of the DNA vaccines in the SN of mice (Fig. 6a, b). Similarly, compared to the female non-Tg controls, the vehicle-treated female hα-Syn-Tg mice showed a 45% loss in TH-positive fibers in the striatum. Mice immunized with PV-1948D (p < 0.05), PV-1949D (p < 0.01), and PV-1950D (p < 0.0001), but not PV-1947D showed significantly higher TH-positive fiber density, which was comparable to non-Tg controls (Fig. 6c, d). We did not detect any loss of neurons or effects of the DNA vaccines in the SN of female mice (Fig. 6c, d). In summary, immunization with PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D ameliorated the loss of NeuN neurons in the neocortex with PV-1950D more effectively. The vaccination effects were more prominent in the female mice compared to the male (Table 1). For the dopaminergic system, the four DNA vaccines were more effective in the male than in the female mice, with PV-1950D displaying more significant effects.

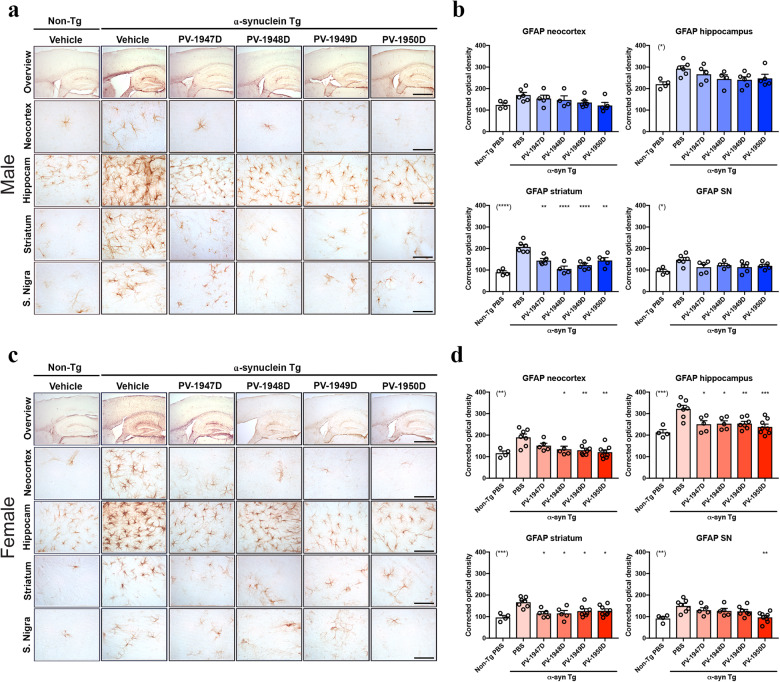

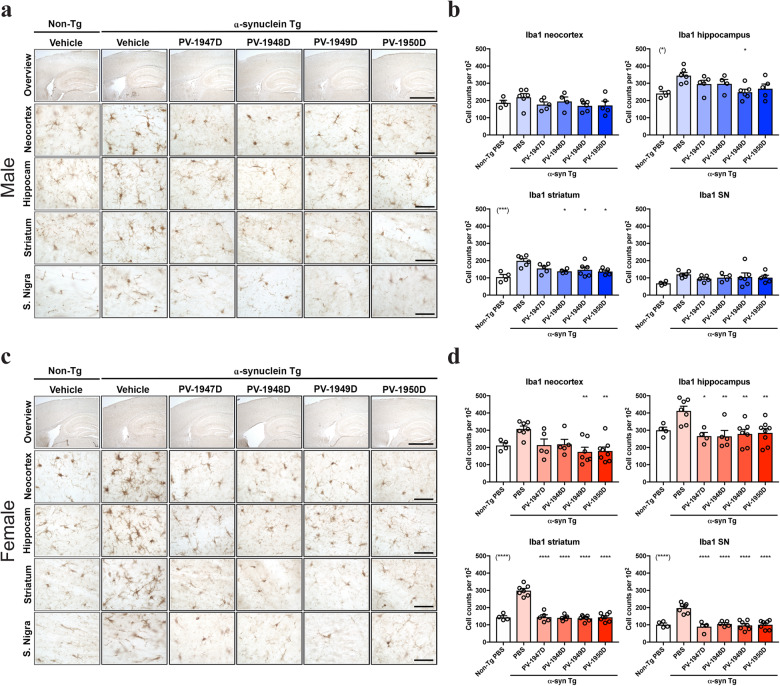

Since the progressive accumulation of hα-syn and neurodegeneration are accompanied by neuroinflammation in the hα-syn-Tg D line mouse model, we analyzed changes in astrogliosis and microgliosis in vaccinated animals. At first, we examined the effects of the DNA vaccination in astrogliosis with an antibody against GFAP. As previously shown, the vehicle-treated male hα-syn-Tg mice showed mild astrogliosis in the neocortex and hippocampus, which is not significant compared to non-Tg controls. Mice immunized with PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D showed a trend toward reduced GFAP immunoreactivity, but effects were not significant compared to vehicle-treated male hα-syn-Tg mice (Fig. 7a, b). In the striatum of the male hα-syn-Tg mice, there was a significant increase in GFAP compared to non-Tg mice, which was decreased to the normal level comparable with non-Tg mice by immunizations with the DNA vaccines. No effects of the immunizations were detected in the SN (Fig. 7a, b). The vehicle-treated female hα-syn-Tg mice showed significant astrogliosis in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and SN compared to the female non-Tg controls. Mice immunized with PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D showed levels of GFAP similar to non-Tg controls (Fig. 7c, d) in the hippocampus and striatum. In the neocortex, three DNA vaccines (PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D) were effective in reducing astrogliosis, while only PV-1950D treated mice showed a significant reduction of GFAP in SN (Fig. 7c, d). Finally, compared to male non-Tg controls, the vehicle-treated male hα-Syn-Tg showed a mild microgliosis in the neocortex and hippocampus, and vaccination with PV-1949D reduced Iba1 immunoreactivity to levels comparable to non-Tg controls (Fig. 8a, b). In the striatum of the male hα-Syn-Tg mice, there was a mild increase in Iba1 compared to non-Tg mice. Immunization with the PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D showed normalization of Iba1 levels comparable to non-Tg mice, while no effects of the DNA vaccines were detected in the SN (Fig. 8a, b). In the female non-Tg controls, the vehicle-treated female hα-Syn-Tg mice showed significant microgliosis in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and SN. Immunization with PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D significantly reduced the Iba1 levels in the hippocampus, striatum, and SN, while only PV-1949D and PV-1950D showed significant effects in the neocortex (Fig. 8c, d). In summary, vehicle-treated hα-Syn-Tg mice showed astrogliosis and microgliosis that was more prominent in the female mice. Nonetheless, DNA vaccines were more effective at reducing astrogliosis and microgliosis in females than male mice showing slightly higher effects with PV-1949D and PV-1950D.

Fig. 7. Vaccination with MultiTEP-based DNA vaccines significantly reduced astrogliosis in α-synuclein transgenic mice.

a Representative images of brain sections from male mice immunostained with an antibody against the astroglial marker-GFAP. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mice with a vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. b Image analysis of GFAP immunoreactivity expressed as corrected optical density in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra of male mice. c Representative images of the brain sections of female mice immunostained with an antibody against the astroglial marker-GFAP. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mice with a vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. d Image analysis of GFAP immunostaining expressed ad corrected optical density in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra of female mice. The scale bar in the overview is 250 µm, the others are 25 µm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Fig. 8. Vaccination with MultiTEP-based DNA vaccines significantly reduced microgliosis in α-synuclein transgenic mice.

a Representative images of the brain sections from male mice immunostained with an antibody against the microglial cell marker -Iba1. Each panel from top to bottom represents an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mice with a vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. b Image analysis of Iba1 positive cell count per 102 in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra of male mice. c Representative images of the brain sections of female mice immunostained with an antibody against the microglial cell marker Iba1. Each panel illustrates from top to bottom an overview of the brain, neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra regions in non-Tg, and αSyn Tg mice with a vehicle, PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccination. d Image analysis of Iba1 positive cell counts in the neocortex, hippocampus, striatum, and substantia nigra of female mice. The scale bar in the overview is 250 µm, the others are 25 µm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

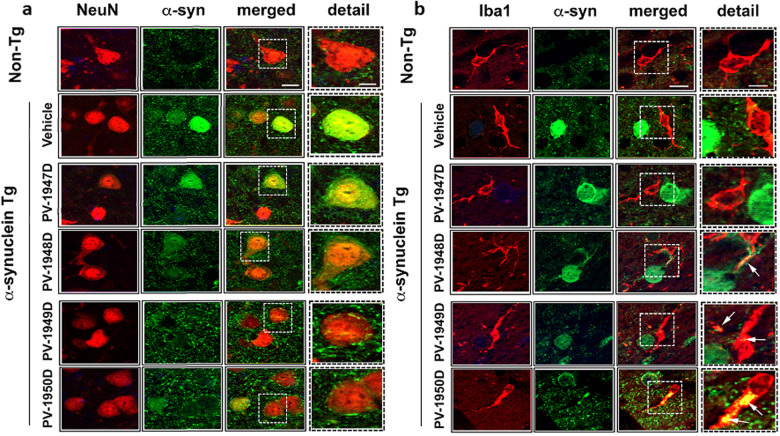

Immunofluorescence analysis of sections double-labeled with antibodies against the neuronal marker NeuN and α-syn showed significant colocalization of α-syn aggregates in the neurons in the vehicle-treated hα-syn-Tg mice (Fig. 9a). We observed a similar level of α-syn accumulation in neurons in mice immunized with PV-1947D. However, mice vaccinated with PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D tended to accumulate less hα-syn in NeuN-positive neurons, with the most negligible accumulation in PV-1950D immunized mice. Double-labeled analyses of brain sections with anti-α-syn and the microglial cell marker Iba1 antibodies showed no colocalization in vehicle-treated hα-syn-Tg mice or mice immunized with PV-1947D. In the brain of hα-syn-Tg mice treated with PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D, the microglial cell bodies and the processes were in closer opposition to the neuronal α-syn aggregates. Moreover, some microglia in the immunized mice displaced colocalization with α-syn suggesting clearance of α-syn via the microglia in the vaccinated mice (Fig. 9b).

Fig. 9. Immunofluorescence analysis of double-labeled brain sections.

Less accumulation of hα-syn in NeuN-positive neurons (a) and a closer opposition of microglia to the neuronal α-syn aggregates (b) in mice vaccinated with PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D was observed compared with PV-1947 vaccinated and control mice. The scale bar is10 μm in the solid box and 5 μm in the dotted box.

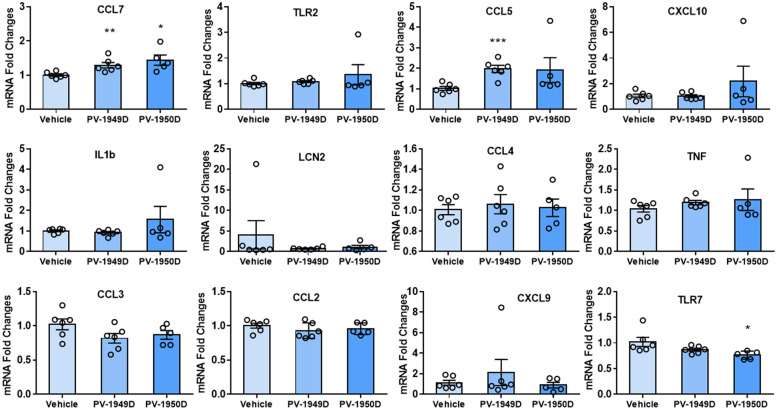

Finally, we analyzed the expression pattern of inflammatory genes in mice immunized with PV-1949D and PV-1950D by Nanostring assay. However, and unfortunately, data showed high variability between individual mice in each group, including the control group injected with placebo followed by EP, so we additionally analyzed selected inflammatory genes expression by RT-qPCR. RT-qPCR analyses indicated that immunizations with PV-1949D and PV-1950D did not change the expression level of the majority of inflammatory genes with few exceptions. The expression of CCL7 and CCL5 were upregulated in mice immunized with PV-1949D, and CCL7 was slightly upregulated, and TLR7 was slightly downregulated in mice immunized with PV-1950D (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Changes in the expression of molecules involved in the inflammatory pathway.

Brains of mice vaccinated with PV-1949D and PV-1950D were analyzed by RT-qPCR.

Discussion

The era of vaccination against neurodegenerative disorders was initiated over 20 years ago when Schenk’s group reported on effective clearance of extracellular amyloid pathology after immunization of a mouse model of AD with fibrillar beta-amyloid peptide formulated in Th1 type adjuvant17,18. Active vaccination strategies targeting various misfolded proteins involved in different neurodegenerative disorders, including DLB/PD, have been pursued after that seminal study19–29. At the same time, it was shown that immunotherapy based on passive administration of mAb specific to Aβ, tau, and α-syn also reduced the accumulation of these pathological molecules in the appropriate animal models23,31,45,61–66. Data from clinical trials on Aβ, tau, and α-Syn immunotherapy support preclinical results and demonstrate that antibodies at relatively high concentrations could reduce the accumulation of related pathological molecules in CNS of participants. In particular, follow-up analyses of the AN-1792 trial demonstrated that even after 14 years, the vaccinated subjects were plaque-free, and there was a significant inverse correlation between peripheral blood anti-Aβ antibody titers and the plaque counts67. In first-in-human trials in patients with PD, vaccination with PD01 substantially reduced CSF levels of α-synuclein oligomers in high-responders36. In Phase 2 AADVac1 trial, vaccinated patients had a reduction of CSF pTau181 and pTau217, and stabilization of total tau, compared with placebo (reported by Alzforum). Unfortunately, so far, both Aβ and tau immunotherapy approaches have uniformly been negative likely because treatment was started too late as a therapeutic measure. Although some clinical trials are still in progress, overall, the field is moving to earlier interventions that suggest even starting immunotherapy in non-diseased people. However, due to the complexity, cost, and need for frequent (every 1–3 mo) intravenous injections of non-diseased people with high concentration mAb, passive vaccination is not ideal for long-term preventive treatment. By contrast, if safe, the immunogenic active vaccine generating antibodies specific to misfolded proteins in non-diseased people could prevent/reduce the accumulation of pathological molecules and, at least, delay the onset and progression of the relevant neurodegenerative diseases for several years. Of course, to start preventive immunization of healthy people at risk of disease, one should have both an accurate predictive biomarker and an immunogenic, safe vaccine.

While many groups worldwide are currently developing blood/CSF/brain biomarkers68–71, we have been developing an immunogenic vaccine platform designated as MultiTEP for almost 20 years30,72–74. This universal vaccine platform is composed of 12 promiscuous foreign Th cell HLA-restricted epitopes: one synthetic peptide PADRE, eight tetanus toxin small non-toxic peptides, two peptides from hepatitis B surface, and core antigens, and one influenza peptide from M protein. The MultiTEP platform is specifically designed for human vaccines and aimed to (i) overcome self-tolerance by inducing Th cell responses specific to MultiTEP, but not possibly harmful responses to self-epitope from pathological molecules involved in neurodegenerative disorders; (ii) diminish variability of immune responses due to HLA diversity in humans; (iii) augment production of appropriate antibodies in vaccinated subjects through activation of not only naïve Th cells but also pre-existing memory Th cells which will be especially beneficial for elderly patients with immunosenescence75,76. This mechanism of action for the MultiTEP platform is supported by our vaccine studies in mouse models of AD and tauopathies, rabbits, and, importantly, nonhuman primates with highly polymorphic MHC class II genes similar to humans30,52,53,55,72–74,77,78.

Taking advantage of the universality and immunogenicity of the MultiTEP platform as well as DNA vaccination technology79–81 providing a unique alternative method of immunization (i.e., DNA constructs are relatively safe, cost- and time-efficient, and do not require frequently toxic conventional adjuvants82), we developed four DNA α-Syn vaccines. These vaccines induced the production of high titers of antibodies specific to three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn separately and simultaneously in wild-type mice30. The main objective of the current study was to evaluate the efficacy and immunogenicity of MultiTEP-based PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D vaccines targeting B-cell epitopes aa85–99, aa109–126, aa126–140 of pathological hα-Syn separately or simultaneously in an animal model of PD/DLB56.

Data presented above demonstrated that the MultiTEP platform-based DNA vaccines induce high titers of antibodies specific to three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn in immunized D line mice. These supported our published data with MultiTEP platform-based vaccines targeting Aβ and tau separately or together55,72–74,77,78. More importantly, the data presented demonstrate that all four DNA vaccines are, to varying degrees, effective in reducing the accumulation of total and aggregated PK-resistant forms of hα-Syn, ameliorating neurodegeneration, in a sex-dependent manner, and improving motor deficits in the D line mouse model of PD/DLB. While for effects in the dopaminergic system, the four DNA vaccines were more effective in the male than in the female mice, with PV-1950D displaying more significant effects.

In terms of neuroinflammation, DNA vaccines were more effective at reducing astrogliosis and microgliosis in females than male mice, with PV-1949D and PV-1950D showing slightly more efficient effects. Our study is one of the first to consider sex differences in response to vaccines for neurodegenerative disorders. The sexual dimorphism in response to the vaccine might be related to environmental, genetic, hormonal factors and severity of the neurodegenerative pathology. It is known that in transgenic models, AD pathology is more prominent in females83. Likewise, a more significant number of women than men are affected by AD (2:1 women: men ratio)84. Nonetheless, whether indicators such as prevalence and incidence translate to sex differences is controversial84. Interestingly, immunotherapy studies targeting Aβ in AD Tg models have shown some differences, with male mice showing a greater reduction of Aβ compared to female mice85. In terms of DLB, there is a slight increase in frequency in females to males (ratio 1.2 women: man), while PD is more frequent in males86. In Tg D line mice, the pathology is similar between males and females57. We found that titers in response to the DNA vaccines were slightly higher in female mice for the present study. Thus, the differences in response to immunotherapy might be related to general factors implicated in determining sex differences in response to vaccination87. In agreement with our findings, previous studies investigating sex dimorphism in various types of vaccines against infectious agents have shown that typically, females develop higher titer responses and higher levels of immunogenicity88. There are multiple mechanisms involved that might explain the sex differences in vaccine-induced immunity, including hormonal, genetic, and microbiome differences between males and females88. It is currently unknown if the gender differences in vaccine response observed in animal models might translate to humans, however, our study suggests that when further developing vaccines for PD and other synucleinopathies, consideration for sex differences is warranted.

Inflammation plays an important role in the progression of AD/PD and other neurodegenerative diseases; hence reduction of neuroinflammation could be beneficial. Immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated that antibodies specific to all three B-cell epitopes of hα-Syn did not generate inflammation in the brain of vaccinated mouse models of DLB/PD. Moreover, we detected a significant reduction in the numbers of activated GFAP+ astrocytes and Iba1+ microglia cells, indicating that vaccination diminished inflammation associated with the accumulation of pathological hα-Syn.

Interestingly, double immunolabeling analysis showed that the vaccines reduced the accumulation of α-Syn in the neuronal cell bodies, especially PV-1950D that was concomitantly associated with the presence of α-Syn in microglial cells. This suggests that either extracellular or neuronal α-Syn captured by the antibodies might be uptake by microglial cells that in turn might be able to clear α-Syn aggregates via phagocytosis and/or autophagy-lysosomal mechanisms. This is consistent with previous studies showing microglial clearance of α-Syn in mice passively immunized with antibodies against the C-terminus of α-Syn40 and that microglia is capable of clearing α-Syn via autophagy89,90.

Analyses of the expression pattern of inflammatory genes in control and immunized mice by Nanostring assay showed high variability between individual mice in each group, making it challenging to detect gene expression changes. Therefore, based on Nanostring data, we additionally analyzed selected inflammatory genes expression by RT-qPCR. The data supported the results with GFAP+ astrocytes and Iba1+ microglia cells, indicating that PV-1949D and PV-1950D did not change the expression level of most inflammatory genes, with a few exceptions. Further experiments with a higher number of mice are needed to overcome observed variability and generate more precise molecular data to reveal the impact of vaccination on inflammatory genes expression.

PV-1949D and PV-1950D were the most effective vaccines, but given that the latter induced antibodies specific to all three B-cell epitopes of pathological hα-Syn, which could reduce pathological aggregates through a combination of mechanisms (such as increased lysosomal/autophagy and microglial removal of intracellular and transcellular aggregates, interfering with cell-to-cell propagation of α-synuclein and destabilizing α-synuclein oligomers and fibrils), we chose PV-1950D for future IND-enabling studies.

In sum, using MultiTEP platform technology developed for the elderly, we have studied immunogenicity and efficacy of DNA vaccines targeting three different epitopes of pathological hα-Syn separately or together. We hypothesized that antibodies generated by either of these vaccines could reduce/inhibit aggregation of hα-Syn in vaccinated subjects and delay the onset of disease or its progression. Future IND enabling CMC and safety/toxicity studies may support the translation of the most immunogenic and effective PV-1950D vaccine to clinical trials.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female and male mice of C57BL6/DBA2 background (H-2b/d) over-expressing hα-Syn under the PDGF-β promoter (D Line) were used in this study56,58,91. A total of 62 Tg hα-Syn mice (n = 28 male and n = 34 female) at age 2.5–4.5 m/o at the start and 12–14 m/o at the end of the experiment have been used in this study (Fig. 1a). All animals were housed in a temperature and Slight-cycle controlled facility, and their care was under the guidelines of NIH and an approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol at UC Irvine.

Ethics statement

All animal procedures were conducted in an AAALACi accredited facility in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals per the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of California, Irvine (UCI). Studies adhere to the NIH and the UCI Animal Care Guidelines.

DNA vaccines

The generation of PV-1947D, PV-1948D, PV-1949D, and PV-1950D plasmids were described previously30. Briefly, minigenes encoding three copies of appropriate B-cell epitope (aa85–99, aa109–126, aa126–140, or all these epitopes together) have been synthesized (GenScript), ligated with a gene encoding MultiTEP composed of a string of twelve foreign Th epitopes52 and cloned into the pVAX1 vector (Invitrogen). Plasmids were purified by Aldevron, and the correct sequences of the generated plasmids were confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis. Expression and secretion of the proteins encoded by generated DNA constructs were confirmed as described in30.

Experimental protocols

Immunizations

Mice in experimental and control groups were injected into both anterior tibialis muscles with 20 µg per leg of the appropriate plasmid in 30 µl PBS or PBS, respectively. Immediately after the DNA administration, electrical pulses were applied using the AgilPulseTM device from BTX Harvard Apparatus, as previously described30. Briefly, the needle electrode made of two parallel rows of four 5-mm needles 0.3 mm in diameter (1.5 × 4-mm gap) was inserted in such a way that the IM injection site was located between the two needle rows. The EP pulses were applied (“high amplitude, short duration” (450/0.05) two pulses and “low amplitude, long-duration” (110/10) eight pulses) using the AgilPulseTM device from BTX Harvard Apparatus (Holliston, MA). Mice, 2–4 mo of age at the start of immunization, received six injections with indicated DNA vaccines or PBS followed by EP on weeks 0, 2, 6, 12, 21, and 29. The sera were collected before injection (pre-bleed) and two weeks after the third (week 8) and fifth (week 23) immunizations. Sera collected after the third injection was used both for analyzing the humoral immune responses and purification of polyclonal antibodies. The motor function of mice was tested two weeks after the last immunization. Mice were terminated at the age of 12–14 mo, and brains were collected for immunohistological analysis. A more detailed experimental protocol is provided in Fig. 1a.

Detection of antibody titers and isotypes

The endpoint titers of antibodies were detected via ELISA using appropriate peptides or full-length recombinant hα-Syn protein as we described earlier92. Briefly, the wells of the ELISA plates were coated with 1 µg/ml of hα-Syn protein (rPeptide) or the appropriate peptide (hα-Syn85-99, hα-Syn109– 126, and hα-Syn126–140) synthesized at Genscript. Sera from individual mice were diluted (serial dilutions from 1:1000 to 1:2,560,000), and endpoint titers were calculated as the reciprocal of the highest sera dilution that gave a reading twice above the background levels of binding of non-immunized sera at the same dilution (cutoff).

Rotarod performance test

The rotarod is an automated apparatus with a 3-cm diameter “grooved rod,” speed controls, and a lever that triggers the timer to stop once the mouse falls from the rod. We measured motor coordination and balance by examining the ability of control and immunized female mice to run on a fixed and accelerated speed rotarod, as was described73. For the fixation rotarod test, the mice were trained for three days in raw at 12 rpm to stay on the fixed speed rotarod for 2 min. If animals fall off, they were placed back onto the spinning rod to learn the task. Twenty-four hours after the last training session, mice were tested for four consecutive trials at 12 rpm for 2 min, and latency to fall off the rotating rod is measured. Data were presented as an average of four trials. For the acceleration test, rotarod speed increased in rpm (from 4 to 40) over the entire testing trial (5 min). The experiment was run by an investigator who was blinded to genotype and treatment. Results were then de-coded during statistical analysis by a second independent investigator.

Brain collection

Brains were collected immediately following perfusion. The left hemisphere from each mouse was postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h then stored in PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide. Right hemispheres previously frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 °C were powdered in liquid nitrogen using mortar and pestle and used for isolation of RNA.

Immunohistochemical assays and image analyses

The procedure for immunohistochemical analysis has been described elsewhere60,93. Briefly, blind-coded sagittal sections were incubated with the following primary antibodies; anti-α-synuclein(Syn1, #610787, BD bioscience, San Diego, CA, 1:250), anti-α-synuclein (Syn211, # 36-008), anti-NeuN(#MAB377, 1:1000), anti-GFAP (#MAB3402, 1:1000), anti-TH (# AB152, Millipore, County Cork, Ireland, 1:1000), and anti-Iba1 (#019-19741, Wako, Richmond, VA, 1:1000). To detect protease K (PK) resistant α-synuclein aggregates, the sections were pretreated with PK (10 µg/ml) for 8 minutes prior to incubating with anti-α-synuclein antibody94. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, the sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibodies and subsequently detected utilizing an ABC staining kit (both from Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, PA). All sections were imaged by an Olympus BX41 microscope, and the immunoreactivity levels were determined by utilizing ImageJ (NIH). To determine α-synuclein pathology, neurodegeneration, microgliosis, and astrogliosis, the optical density of α-synuclein and GFAP per field (230 mm×184 mm) and the numbers of α-synuclein-positive, NeuN-positive, TH-positive fibers, Iba1-positive cells per indicated field were analyzed using Image Quant 1.43 program (NIH).

Human α-synuclein enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Right hemispheres, previously frozen on dry ice and stored at -80oC, were crushed in liquid nitrogen using mortar and pestle. The brain powder was homogenized in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, and proteinase inhibitor cocktails). Cytosolic and membrane fractions were separated by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C as previously described95. The concentrations of human α-synuclein were determined in lysates normalized to contain 10 μg of total protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Double immunolabeling and imaging

For double immunofluorescence labeling, blind-coded vibratome sections were incubated with the combinations of antibodies against NeuN/α-syn and Iba1/α-syn, as previously described96. The immunostained brain sections and neurons were visualized with Texas-red and FITC-tagged secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories) and mounted under glass coverslips with anti-fading media (Vector Laboratories) after staining the nucleus with DAPI (Hoechst 33258). Briefly, as previously described96, the double immunolabeled sections were imaged with an Apotome II mounted in a Carl Zeiss AxioImager Z1 microscope.

Detection of hα-Syn in human brain tissues from AD/DLB cases

Antibodies from mice immunized with PV-1950D were screened for the ability to bind to LB in the human brain tissues, as we previously described30,54,73. As a positive control, we used anti-α-synuclein (LB509, # ab27766, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Briefly, purified anti-hα-Syn antibodies (1 µg/ml) were added to the serial 40 µm brain sections of formalin-fixed frontal cortical and Amy tissues from two typical AD/DLB cases obtained from the UCI MiND Brain Bank and Tissue Repository with the following neuropathology: (i) case #42-16: tangle stage 5, Plaque stage C, LB detected in substantia nigra, entorhinal cortex, Amy, frontal/temporal/parietal/rostral cingulate cortex, locus coeruleus, dorsal motor vagal nucleus, oculomotor nucleus, hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and olfactory bulb, and (ii) case #41-04: tangle stage 6, Aβ plaque stage C, LB detected in substantia nigra, Amy, frontal/temporal/parietal/rostral cingulate, locus coeruleus, and innominate substance. A control case, brain #28-18 has tangle stage 2 and plaque stage A, but no detectable LB that is typical for pre-AD and early AD neuropathology. After the brain sections were mounted on the slides and pretreated with citrate buffer, they were incubated with α-synuclein (2 μg/ml) primary antibodies, then with the biotinylated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) and subsequently detected utilizing an ABC staining kit and DAB substrate (both from Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. A digital camera (Olympus BX 51, Japan) was used to capture images of LBs at ×20 magnification.

Gene expression analyses

About 10 mg of crushed brain powder was used to purify RNA according to the manufacturer’s protocols using the RNeasy Mini Kit and QiaShredder homogenization columns (Qiagen). RNA was run with the Nanostring Mouse Neuroinflammation Panel (Nanostring) at the UCI core facility. Analysis of select genes was performed in nSolver software (Nanostring). In addition, reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed for gene expression analyses of selected genes. RNA was reverse transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase and random primers (Applied Biosystems). Fifty nanograms of cDNA was used for qPCR by Taqman gene expression assay with primers and probes from Applied Biosystems (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-qPCR was run in QuantStudio(TM) 7 Flex System. As a control housekeeping gene, β-actin was used. Fold changes in gene expression were calculated according to the formula: Fold difference = 2−(ΔΔCT values), where ΔΔC T value = sample ΔC T values − control ΔC T values, where ΔC T values = sample C T value − housekeeping gene C T value.

Statistical analysis

Statistical parameters (mean, standard deviation, significant difference, etc.) were calculated using the Prism 6.07 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Statistically significant differences were examined using analysis of variance (ordinary one-way ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-test or unpaired t-test (a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from NIH (R01AG20241, R01NS050895, and U01AG060965). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author contributions

C.K. and A.H. equally contributed to this work as co-first authors, and E.M. and M.G.A. equally contributed as co-corresponding authors. C.K., M.I., A.A., E.R., and M.S. performed immunohistochemical /immunofluorescence and biochemical analyses of the brains. A.H., H.D., and T.A. prepared DNA plasmids, performed the immunizations of mice, and analyzed immune responses. G.C., K.Z. performed behavioral testing of animals and purified the protein vaccine. J.H., T.A., and A.G. performed Nanostring and RT-qPCR. I.P. performed human brains IHC. M.B.J., D.H.C., made substantial contributions to the conception of studies. A.G., E.M., M.G.A. made substantial contributions to the conception, design of the work, interpretation of results, mentored primary authors, drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors have revised, read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article, and materials are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

M.G.A. and A.G. are co-founders of Nuravax that licensed MultiTEP vaccine platform technology from the Institute for Molecular Medicine. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01102-3

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Changyoun Kim, Armine Hovakimyan.

These authors jointly supervised: Eliezer Masliah, Michael G. Agadjanyan.

Change history

10/15/2024

Editor's Note: Readers are alerted that concerns have been raised regarding the reliability of data presented in this article. Further editorial action will be taken if appropriate once the investigation into the concerns is complete and all parties have been given an opportunity to respond in full.

Change history

7/17/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41541-023-00703-0

Change history

3/12/2025

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: 10.1038/s41541-025-01102-3

Contributor Information

Eliezer Masliah, Email: eliezer.masliah@nih.gov.

Michael G. Agadjanyan, Email: magadjanyan@immed.org

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41541-021-00424-2.

References

- 1.Wakabayashi, K. Where and how alpha-synuclein pathology spreads in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropathology40, 415–425, 10.1111/neup.12691 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volpicelli-Daley, L. A. et al. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils induce Lewy body pathology leading to synaptic dysfunction and neuron death. Neuron72, 57–71 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vekrellis, K., Xilouri, M., Emmanouilidou, E., Rideout, H. J. & Stefanis, L. Pathological roles of alpha-synuclein in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol.10, 1015–1025 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee, V. M. & Trojanowski, J. Q. Mechanisms of Parkinson’s disease linked to pathological alpha-synuclein: new targets for drug discovery. Neuron52, 33–38 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goedert, M., Jakes, R. & Spillantini, M. G. The synucleinopathies: twenty years on. J. Parkinson’s Dis.7, S51–S69 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Games, D. et al. Axonopathy in an alpha-synuclein transgenic model of Lewy body disease is associated with extensive accumulation of C-terminal-truncated alpha-synuclein. Am. J. Pathol.182, 940–953 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer, M. L. & Schulz-Schaeffer, W. J. Presynaptic alpha-synuclein aggregates, not Lewy bodies, cause neurodegeneration in dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Neurosci.27, 1405–1410 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridi, J. C. & Hirth, F. Mechanisms of alpha-synuclein induced synaptopathy in Parkinson’s Disease. Front Neurosci.12, 80 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan, J. A. et al. Early synaptic dysfunction induced by alpha-synuclein in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep.7, 6363 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockenstein, E. et al. Accumulation of oligomer-prone alpha-synuclein exacerbates synaptic and neuronal degeneration in vivo. Brain137, 1496–1513 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellner, L., Jellinger, K. A., Wenning, G. K. & Stefanova, N. Glial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of alpha-synucleinopathies: emerging concepts. Acta Neuropathol.121, 675–693 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jellinger, K. A. & Lantos, P. L. Papp-Lantos inclusions and the pathogenesis of multiple system atrophy: an update. Acta Neuropathol.119, 657–667 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monzio Compagnoni, G. & Di Fonzo, A. Understanding the pathogenesis of multiple system atrophy: state of the art and future perspectives. Acta Neuropathol. Commun.7, 113 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang, A. E. & Espay, A. J. Disease modification in Parkinson’s disease: current approaches, challenges, and future considerations. Mov. Disord.33, 660–677 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fahn, S. et al. Levodopa and the progression of Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med.351, 2498–2508 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahn, S. Does levodopa slow or hasten the rate of progression of Parkinson’s disease? J. Neurol.252, IV37–IV42 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schenk, D. et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse [see comments]. Nature400, 173–177 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overk, C. & Masliah, E. Dale Schenk one year anniversary: fighting to preserve the memories. J. Alzheimers Dis.62, 1–13 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chatterjee, D. & Kordower, J. H. Immunotherapy in Parkinson’s disease: current status and future directions. Neurobiol. Dis.132, 104587 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masliah, E. et al. Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron46, 857–868 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asuni, A. A., Boutajangout, A., Quartermain, D. & Sigurdsson, E. M. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau conformers in a tangle mouse model reduces brain pathology with associated functional improvements. J. Neurosci.27, 9115–9129 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandler, M. et al. Next-generation active immunization approach for synucleinopathies: implications for Parkinson’s disease clinical trials. Acta Neuropathol.127, 861–879 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schofield, D. J. et al. Preclinical development of a high affinity alpha-synuclein antibody, MEDI1341, that can enter the brain, sequester extracellular alpha-synuclein and attenuate alpha-synuclein spreading in vivo. Neurobiol. Dis.132, 104582 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandusky-Beltran, L. A. & Sigurdsson, E. M. Tau immunotherapies: lessons learned, current status and future considerations. Neuropharmacology, 108104, 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108104 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Novak, P., Kontsekova, E., Zilka, N. & Novak, M. Ten years of Tau-targeted immunotherapy: the path walked and the roads ahead. Front Neurosci.12, 798 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bittar, A., Bhatt, N. & Kayed, R. Advances and considerations in AD tau-targeted immunotherapy. Neurobiol. Dis.134, 104707 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shin, J., Kim, H. J. & Jeon, B. Immunotherapy targeting neurodegenerative proteinopathies: alpha-synucleinopathies and tauopathies. J. Mov. Disord.13, 11–19 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwon, S., Iba, M., Kim, C. & Masliah, E. Immunotherapies for aging-related neurodegenerative diseases-emerging perspectives and new targets. Neurotherapeutics, 10.1007/s13311-020-00853-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Valera, E. & Masliah, E. Immunotherapy for neurodegenerative diseases: focus on alpha-synucleinopathies. Pharmacol. Ther.138, 311–322 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davtyan, H. et al. MultiTEP platform-based DNA vaccines for alpha-synucleinopathies: preclinical evaluation of immunogenicity and therapeutic potency. Neurobiol. Aging59, 156–170 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masliah, E. et al. Passive immunization reduces behavioral and neuropathological deficits in an alpha-synuclein transgenic model of Lewy body disease. PLoS ONE6, e19338 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Games, D. et al. Reducing C-terminal-truncated alpha-synuclein by immunotherapy attenuates neurodegeneration and propagation in Parkinson’s disease-like models. J. Neurosci.34, 9441–9454 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mandler, M. et al. Active immunization against alpha-synuclein ameliorates the degenerative pathology and prevents demyelination in a model of multiple system atrophy. Mol. Neurodegener.10, 10 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneeberger, A., Mandler, M., Mattner, F. & Schmidt, W. Vaccination for Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord.18, S11–S13 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meissner, W. G. et al. A phase 1 randomized trial of specific active alpha-synuclein immunotherapies PD01A and PD03A in multiple system atrophy. Mov. Disord.35, 1957–1965 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volc, D. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the alpha-synuclein active immunotherapeutic PD01A in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, single-blinded, phase 1 trial. Lancet Neurol.19, 591–600 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poewe, W. et al. Safety and tolerability of active immunotherapy targeting α-synuclein with PD03A in patients with early Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 1 study. J. Parkinsons Dis. 1–11, 10.3233/JPD-212594 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Katsinelos, T., Tuck, B. J., Mukadam, A. S. & McEwan, W. A. The Role of Antibodies and Their Receptors in Protection Against Ordered Protein Assembly in Neurodegeneration. Front Immunol.10, 1139 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valera, E., Spencer, B. & Masliah, E. Immunotherapeutic approaches targeting amyloid-beta, alpha-synuclein, and tau for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Neurotherapeutics13, 179–189 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bae, E. J. et al. Antibody-aided clearance of extracellular alpha-synuclein prevents cell-to-cell aggregate transmission. J. Neurosci.32, 13454–13469 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spencer, B. et al. ESCRT-mediated uptake and degradation of brain-targeted alpha-synuclein single chain antibody attenuates neuronal degeneration in vivo. Mol. Ther.22, 1753–1767 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.El-Agnaf, O. et al. Differential effects of immunotherapy with antibodies targeting alpha-synuclein oligomers and fibrils in a transgenic model of synucleinopathy. Neurobiol. Dis.104, 85–96 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43.McGlinchey, R. P. et al. C-terminal alpha-synuclein truncations are linked to cysteine cathepsin activity in Parkinson’s disease. J. Biol. Chem.294, 9973–9984 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chatterjee, D. et al. Proteasome-targeted nanobodies alleviate pathology and functional decline in an alpha-synuclein-based Parkinson’s disease model. NPJ Parkinsons Dis.4, 25 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spencer, B. et al. Anti-alpha-synuclein immunotherapy reduces alpha-synuclein propagation in the axon and degeneration in a combined viral vector and transgenic model of synucleinopathy. Acta Neuropathol. Commun.5, 7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desplats, P. et al. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA106, 13010–13015 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chu, Y. & Kordower, J. H. The prion hypothesis of Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep.15, 28 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brundin, P., Ma, J. & Kordower, J. H. How strong is the evidence that Parkinson’s disease is a prion disorder? Curr. Opin. Neurol.29, 459–466 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ugalde, C. L., Finkelstein, D. I., Lawson, V. A. & Hill, A. F. Pathogenic mechanisms of prion protein, amyloid-beta and alpha-synuclein misfolding: the prion concept and neurotoxicity of protein oligomers. J. Neurochem.139, 162–180 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen, Y. et al. Engineering synucleinopathy-resistant human dopaminergic neurons by CRISPR-mediated deletion of the SNCA gene. Eur. J. Neurosci.49, 510–524 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melki, R. Alpha-synuclein and the prion hypothesis in Parkinson’s disease. Rev. Neurol.174, 644–652 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghochikyan, A. et al. Refinement of a DNA based Alzheimer’s disease epitope vaccine in rabbits. Hum. Vaccin Immunother.9, 1002–1010 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Evans, C. F. et al. Epitope-based DNA vaccine for Alzheimer’s disease: translational study in macaques. Alzheimers Dement.10, 284–295 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davtyan, H. et al. MultiTEP platform-based DNA epitope vaccine targeting N-terminus of tau induces strong immune responses and reduces tau pathology in THY-Tau22 mice. Vaccine35, 2015–2024 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petrushina, I. et al. Characterization and preclinical evaluation of the cGMP grade DNA based vaccine, AV-1959D to enter the first-in-human clinical trials. Neurobiol. Dis.139, 104823 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Masliah, E. et al. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science287, 1265–1269 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amschl, D. et al. Time course and progression of wild type alpha-synuclein accumulation in a transgenic mouse model. BMC Neurosci.14, 6 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rockenstein, E., Crews, L. & Masliah, E. Transgenic animal models of neurodegenerative diseases and their application to treatment development. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev.59, 1093–1102 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Price, D. L. et al. The small molecule alpha-synuclein misfolding inhibitor, NPT200-11, produces multiple benefits in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep.8, 16165 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim, C. et al. Immunotherapy targeting toll-like receptor 2 alleviates neurodegeneration in models of synucleinopathy by modulating alpha-synuclein transmission and neuroinflammation. Mol. Neurodegener.13, 43 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Agadjanyan, M. G. et al. Humanized monoclonal antibody armanezumab specific to N-terminus of pathological tau: characterization and therapeutic potency. Mol. Neurodegener.12, 33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dai, C. L., Tung, Y. C., Liu, F., Gong, C. X. & Iqbal, K. Tau passive immunization inhibits not only tau but also Abeta pathology. Alzheimers Res. Ther.9, 1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sankaranarayanan, S. et al. Passive immunization with phospho-tau antibodies reduces tau pathology and functional deficits in two distinct mouse tauopathy models. PLoS ONE10, e0125614 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aisen, P. S. & Vellas, B. Passive immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: what have we learned, and where are we headed? J. Nutr. Health Aging17, 49–50 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yanamandra, K. et al. Anti-tau antibody reduces insoluble tau and decreases brain atrophy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol.2, 278–288 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yanamandra, K. et al. Anti-tau antibodies that block tau aggregate seeding in vitro markedly decrease pathology and improve cognition in vivo. Neuron80, 402–414 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nicoll, J. A. R. et al. Persistent neuropathological effects 14 years following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain142, 2113–2126 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paolini Paoletti, F., Gaetani, L. & Parnetti, L. The challenge of disease-modifying therapies in Parkinson’s disease: role of CSF biomarkers. Biomolecules10, 10.3390/biom10020335 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]