Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus group A strain variations of 28 isolates from The Netherlands collected during three consecutive seasons were studied by analyzing G protein sequences. Several lineages circulated repeatedly and simultaneously during the respective seasons. No relationships were found between lineages on the one hand and clinical severity or age on the other.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) can be divided into two groups, A and B, on the basis of the reaction with monoclonal antibodies directed against the F and G proteins (1, 23) and nucleotide sequence differences of several genes (5, 16, 30, 31). These two groups circulate independently in the human population, with group A being the most prevalent (14, 23).

Also, within the two groups substantial strain differences have been described, mainly associated with the divergence in the gene encoding the G protein (17), which is the most variable protein of the virus. Several lineages within groups A and B also seem to cocirculate simultaneously in the population (3, 30). Studies on RSV strains show an accumulation of amino acid changes over the years, suggesting antigenic drift-based, immunity-mediated selection (4, 5, 8, 15, 27).

One of the most interesting features of RSV is its ability to cause repeated infections throughout life (9, 11). This enables RSV to remain present at high levels in the population, and it has been estimated that at least 50% of children encounter their first RSV infection during their first winter season. Strain variation is thought to contribute to its ability to cause frequent reinfections (4, 8, 32).

The clinical severity of RSV infection is associated with epidemiological and host factors, which include socioeconomic status (26), age (26), prematurity (25), and underlying heart and/or lung disease (10, 19). Several studies have evaluated differences in clinical severity between groups A and B. In about half of these studies, no differences in clinical severity were detected between the groups involved (14, 18, 21, 22, 28, 34, 37), and in the other studies, group A seemed to be associated with more severe clinical disease (12, 13, 20, 23, 29, 33, 36). It has been suggested that virus variants within group A are responsible for this discrepancy (7, 12, 36).

To further address this issue, we selected group A strains from three consecutive winter seasons and subjected isolates of these strains to sequence analyses of part of the G protein. The strains were isolated from children for whom standardized clinical data were available from a previous study concerning RSV-A versus RSV-B and clinical severity (18).

RSV isolates (n = 293) found in routine diagnostics during three consecutive winter seasons were typed by performing direct immune fluorescence on cells from nasopharyngeal washings using specific monoclonal antibodies MAB 92-11C for group A and MAB 109-10B for group B (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.) as previously described (2). Twenty-eight RSV group A isolates were selected for sequence analysis.

All five group A strains available from the first season (1992–1993) were included. Eleven from the second season (1993–1994) and twelve from the third season (1994–1995) were selected from children who had experienced either a mild infection (not admitted) or a severe infection as determined by clinical parameters upon admission (see below).

Demographic and clinical data on the children during the acute phase and at the time of the control visit were collected in a previous study (18). Briefly, the data included gender, age, duration of pregnancy, underlying disease, feeding difficulties, history of apnea, the presence of retractions, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation (SaO2) in room air, partial CO2 pressure (pCO2), pH, abnormalities on X rays, admission to an intensive care unit, and the need for artificial ventilation. Severe RSV infection was defined as meeting one or more of the following criteria: pCO2 > 6.6 kPa, SaO2 < 90%, and/or the need for artificial ventilation.

Viral RNA extraction and amplification of the viral RNA by reverse transcriptase PCR were carried out as described previously (35). Briefly, RNA was extracted from 100 μl of culture supernatant using a guanidinium isothiocyanate solution and was collected by precipitation with isopropanol. The viral RNA was then amplified by reverse transcriptase PCR using oligonucleotide primers G(A)-173s (GGCAATGATAATCTCAACTTC) and G(A)-525as (TGAATATGCTGCAGGGTACT), which resulted in an amplified fragment of 392 bp spanning the first hypervariable region of the G protein (amino acids [aa] 100 to 132). The amplified products were subjected to nucleotide sequence analysis by cycle sequencing using an ABI dye terminator sequencing system and analysis on an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk a/d IJssel, The Netherlands). Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the G protein gene of the RSV isolates was carried out using the GCG package (Madison, Wis.). Multiple sequence files were analyzed by DNAPARS in the PHYLIP package (6). Subsequently, phenograms were generated using the DRAWGRAM program.

Clinical data of patients from the respective seasons were compared in a χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann-Whitney U test when applicable.

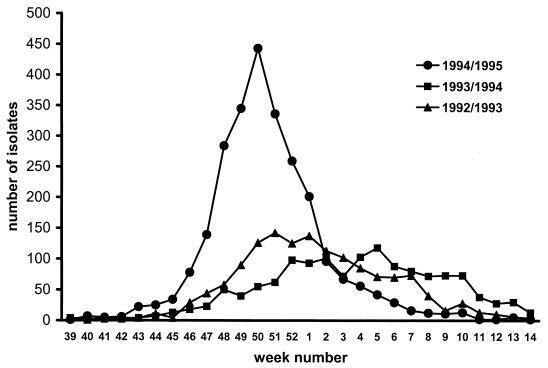

During the three winter seasons, 232 children younger than 12 months of age were diagnosed with a RSV infection by direct immune fluorescence and/or virus isolation. In 1992–1993 a predominance of group B viruses was found, season 1993–1994 showed a mixed epidemic, and in season 1994–1995 all children were infected with group A viruses (18). Figure 1 shows the numbers of RSV isolates in The Netherlands per week during the three seasons. In the 1994–1995 season, a short steep peak in the first weeks of December was observed. During this third season, more children younger than 1 month of age were admitted. Children in the third season had a higher mean pCO2 and lower pH (Table 1) than children in the first two seasons. No other differences in parameters known to correlate with clinical severity could be objectively measured.

FIG. 1.

Number of RSV isolates per week during the three seasons studied, as recorded by the combined Dutch Virology Laboratories. (Published with permission of the Dutch Working Group on Clinical Virology.)

TABLE 1.

Clinical parameters of RSV-infected patients during three consecutive seasons

| Patient variable | Season

|

Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992–1993 and 1993–1994 | 1994–1995 | ||

| No. of children | 130 | 102 | NS |

| No. (%) <37 mo gestation | 37 (28.5) | 21 (20.5) | NS |

| No. (%) <1 mo old | 9 (6.9) | 17 (16.7) | 0.035 |

| Mean (SD) respiratory rate | 51.9 (13.4) | 51.6 (20.3) | NS |

| No. (%) with history of apnea | 23 (17.7) | 23 (22.5) | NS |

| No. (%) wheezing | 47 (36.1) | 34 (33.2) | NS |

| Mean (% SD) pCO2 | 6.1 (1.4) | 6.93 (2.35) | 0.027 |

| Mean (SD) pH | 7.36 (0.07) | 7.33 (0.11) | 0.040 |

| Mean (SD) SaO2 | 90.7 (8.7) | 89.9 (12.2) | NS |

| No. (%) on artificial ventilation | 13 (10.0) | 15 (14.7) | NS |

| No. (%) with severe RSVb | 51 (39.2) | 46 (45.1) | NS |

Clinical data of patients were compared in a χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, or Mann-Whitney U test when applicable. NS, no statistical difference.

Severe RSV infection was defined as meeting one or more of the following criteria: pCO2 > 6.6 kPa, SaO2 < 90%, and/or on artificial ventilation.

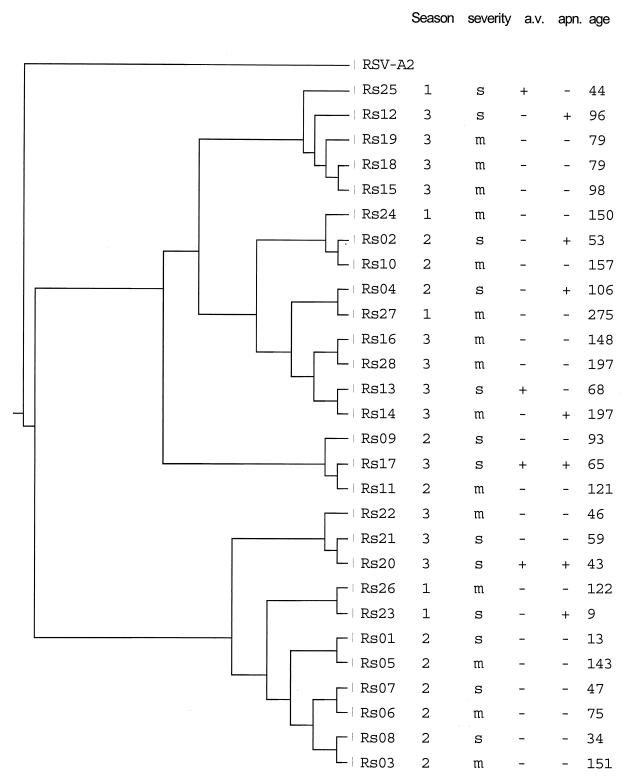

G protein amplicons of 28 RSV group A isolates divided over the three seasons were studied by sequence analysis, and a phenogram was generated (Fig. 2). Season of infection, age upon diagnosis, and clinical parameters—severity score, artificial ventilation, and apnea—are indicated in the phenogram.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic dendrogram showing relatedness of group A isolates determined by sequence analyses of the first hypervariable region of the G protein. Isolates were selected from three consecutive seasons in the Sophia Children's Hospital of Rotterdam. Seasons indicated are as follows: 1, 1992–1993; 2, 1993–1994; 3, 1994–1995. For each isolate, the following patient characteristics are indicated. Severity of RSV infection: s, severe; m, mild. Severe was defined as meeting one or more of the following criteria: pCO2 > 6.6 kPa, SaO2 < 90%, and a need for artificial ventilation. a.v., the need for artificial ventilation; apn., a history of apnea; age, the age in days upon admission.

Several lineages of RSV were found to be present during the three seasons studied, and several lineages could be identified during all three seasons. Closely related strains were also found to occur in subsequent seasons. The observed clustering of the RSV isolates proved to be independent of season or patient-related parameters (Fig. 2).

Thus, several lineages of RSV-A cocirculated during the three seasons studied, and clinically severe as well as milder cases were evenly distributed over the different lineages found.

RSV infections are usually found during several months in the winter season. In the 1994–1995 season, a relatively high incidence of RSV infections during a relatively short period was found. In the 1994–1995 season, more children from the very young age group were admitted. The only clinical parameters objectively found to be more severe in the 1994–1995 season were the pCO2 and the pH. These parameters may be directly related to the younger age of the children involved, since a significant relationship between pCO2 and age has been previously described (24).

The RSV-G protein is the most variable of the RSV proteins; therefore, we chose to sequence a variable part of the RSV-G protein to study strain variation within subgroup A. However, it is not known where in the RSV genome putative virulence factors would be located. Since we sequenced only a small part of the genome, it cannot be fully excluded that mutations important for virulence elsewhere on the RSV genome were missed.

The isolates from the 1994–1995 season were all of group A. We investigated whether this peak represented a single, possibly more virulent, strain of RSV-A. Despite the limited number of strains that were sequenced, it was clear that in the 1994–1995 season, as well as in the other two seasons, several different strains cocirculated, and severe infections or younger age proved not to be related to one particular strain. In addition, closely related strains were found during different seasons, as has been described previously (3, 8, 30).

Collectively, our data show that during a winter season when relatively many children are admitted during a relatively short period, several strains may cocirculate in the population. In addition, it was shown that clinically more severe cases were found spread over the branches of the phylogenetic tree. Therefore, severity of infection could not be attributed to particular lineages of RSV.

Acknowledgments

We thank Conny Kruyssen for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson L J, Hierholzer J C, Tsou C, Hendry R M, Fernie B F, Stone Y, McIntosh K. Antigenic characterization of respiratory syncytial virus strains with monoclonal antibodies. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:626–633. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandenburg A H, Groen J, Van Steensel-Moll H A, Claas E J C, Rothbarth P H, Neijens H J, Osterhaus A D M E. Respiratory syncytial virus specific serum antibodies in infants under six months of age: limited serological response upon infection. J Med Virol. 1997;52:97–104. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199705)52:1<97::aid-jmv16>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cane P A, Matthews D A, Pringle C R. Analysis of relatedness of subgroup A respiratory syncytial viruses isolated worldwide. Virus Res. 1992;25:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90096-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cane P A, Matthews D A, Pringle C R. Analysis of respiratory syncytial virus strain variation in successive epidemics in one city. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.1-4.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cane P A, Pringle C R. Evolution of subgroup A respiratory syncytial virus: evidence for progressive accumulation of amino acid changes in the attachment protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2918–2925. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2918-2925.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felsenstein J. Phylip-Phylogeny Interference Package. Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher J N, Smyth R L, Thomas H M, Ashby D, Hart C A. Respiratory syncytial virus genotypes and disease severity among children in hospital. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:508–511. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.6.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia O, Martin M, Dopazo J, Arbiza J, Frabasile S, Russi J, Hortal M, Perez-Brena P, Martinez I, Garcia-Barreno B. Evolutionary pattern of human respiratory syncytial virus (subgroup A): cocirculating lineages and correlation of genetic and antigenic changes in the G glycoprotein. J Virol. 1994;68:5448–5459. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5448-5459.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glezen W P, Taber L H, Frank A L, Kasel J A. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:543–546. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200053026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groothuis J R, Gutierrez K M, Lauer B A. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 1988;82:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall C B, Walsh E E, Long C E, Schnabel K C. Immunity to and frequency of reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:693–698. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall C B, Walsh E E, Schnabel K C, Long C E, McConnochie K M, Hildreth S W, Anderson L J. Occurrence of groups A and B of respiratory syncytial virus over 15 years: associated epidemiologic and clinical characteristics in hospitalized and ambulatory children. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:1283–1290. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heikkinen T, Waris M, Ruuskanen O, Putto-Laurila A, Mertsola J. Incidence of acute otitis media associated with group A and B respiratory syncytial virus infections. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:419–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendry R M, Talis A L, Godfrey E, Anderson L J, Fernie B F, McIntosh K. Concurrent circulation of antigenically distinct strains of respiratory syncytial virus during community outbreaks. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:291–297. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansen J, Christensen L S, Hornsleth A, Klug B, Hansen K S, Nir M. Restriction pattern variability of respiratory syncytial virus during three consecutive epidemics in Denmark. APMIS. 1997;105:303–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1997.tb00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson P R, Spriggs M K, Olmsted R A, Collins P L. The G glycoprotein of human respiratory syncytial viruses of subgroups A and B: extensive sequence divergence between antigenically related proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:5625–5629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.16.5625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson P R, Jr, Olmsted R A, Prince G A, Murphy B R, Alling D W, Walsh E E, Collins P L. Antigenic relatedness between glycoproteins of human respiratory syncytial virus subgroups A and B: evaluation of the contributions of F and G glycoproteins to immunity. J Virol. 1987;61:3163–3166. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.10.3163-3166.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kneyber M C, Brandenburg A H, Rothbarth P H, de Groot R, Ott A, Van Steensel-Moll H A. Relationship between clinical severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection and subtype. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:137–140. doi: 10.1136/adc.75.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald N E, Hall C B, Suffin S C, Alexson C, Harris P J, Manning J A. Respiratory syncytial viral infection in infants with congenital heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:397–400. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208123070702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McConnochie K M, Hall C B, Walsh E E, Roghmann K J. Variation in severity of respiratory syncytial virus infections with subtype. J Pediatr. 1990;117:52–62. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntosh E D, De Silva L M, Oates R K. Clinical severity of respiratory syncytial virus group A and B infection in Sydney, Australia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:815–819. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199310000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monto A S, Ohmit S. Respiratory syncytial virus in a community population: circulation of subgroups A and B since 1965. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:781–783. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mufson M A, Belshe R B, Orvell C, Norrby E. Respiratory syncytial virus epidemics: variable dominance of subgroups A and B strains among children, 1981–1986. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:143–148. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulholland E K, Olinsky A, Shann F A. Clinical findings and severity of acute bronchiolitis. Lancet. 1990;335:1259–1261. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91314-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navas L, Wang E, de Carvalho V, Robinson J. Improved outcome of respiratory syncytial virus infection in a high-risk hospitalized population of Canadian children. Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada. J Pediatr. 1992;121:348–354. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)90000-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parrott R H, Kim H W, Arrobio J O, Hodes D S, Murphy B R, Brandt C D, Camargo E, Chanock R M. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus infection in Washington, D.C. II. Infection and disease with respect to age, immunologic status, race and sex. Am J Epidemiol. 1973;98:289–300. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a121558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peret T C, Hall C B, Schnabel K C, Golub J A, Anderson L J. Circulation patterns of genetically distinct group A and B strains of human respiratory syncytial virus in a community. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2221–2229. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-9-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russi J C, Chiparelli H, Montano A, Etorena P, Hortal M. Respiratory syncytial virus subgroups and pneumonia in children. (Letter and comment.) Lancet. 1989;2:1039–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salomon H E, Avila M M, Cerqueiro M C, Orvell C, Weissenbacher M. Clinical and epidemiologic aspects of respiratory syncytial virus antigenic variants in Argentinian children. (Letter.) J Infect Dis. 1991;163:1167. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storch G A, Anderson L J, Park C S, Tsou C, Dohner D E. Antigenic and genomic diversity within group A respiratory syncytial virus. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:858–861. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sullender W M, Mufson M A, Anderson L J, Wertz G W. Genetic diversity of the attachment protein of subgroup B respiratory syncytial viruses. J Virol. 1991;65:5425–5434. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5425-5434.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullender W M, Mufson M A, Prince G A, Anderson L J, Wertz G W. Antigenic and genetic diversity among the attachment proteins of group A respiratory syncytial viruses that have caused repeat infections in children. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:925–932. doi: 10.1086/515697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor C E, Morrow S, Scott M, Young B, Toms G L. Comparative virulence of respiratory syncytial virus subgroups A and B. (Letter.) Lancet. 1989;1:777–778. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsutsumi H, Onuma M, Nagai K, Yamazaki H, Chiba S. Clinical characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) subgroup infections in Japan. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;23:671–674. doi: 10.3109/00365549109024291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Milaan A J, Sprenger M J, Rothbarth P H, Brandenburg A H, Masurel N, Class E C. Detection of respiratory syncytial virus by RNA-polymerase chain reaction and differentiation of subgroups with oligonucleotide probes. J Med Virol. 1994;44:80–87. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh E E, McConnochie K M, Long C E, Hall C B. Severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection is related to virus strain. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:814–820. doi: 10.1086/513976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang E E, Law B J, Stephens D. Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada (PICNIC) prospective study of risk factors and outcomes in patients hospitalized with respiratory syncytial viral lower respiratory tract infection. J Pediatr. 1995;126:212–219. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]