Abstract

This article outlines the results of a three-month-long community letter-writing and letter-sharing project called “Viral Epistolary” (VE), which we completed online in Italy during the first wave of COVID-19 lockdowns. In it, we collected 340 digital letters from all over the country and connected thousands of people through epistolary exchanges. We used the genre of letters as a mediating, meaning-making, and (auto)biographical tool whereby people could share their experiences of domestic isolation and physical distancing, thus creating a community of support. Based on a well-documented understanding of meaning-making as a core human endeavor, especially in times of social disruption and personal crisis, this article frames sense-making as a transcendental and even spiritual process that yields broad principles for organizing life. Thus, the research adopts a psychosocial perspective on spirituality and applies thematic analysis to qualitatively analyze written narratives. The results reveal that many respondents underwent a three-part, not-necessarily-sequential process of collapsing, self-distancing, and transcending during lockdown, which allowed them to rearrange themselves according to the new total social fact of the pandemic. Through this process, respondents negotiated themes of semiotic crisis, striving for meaning, and beyond meaning (the essential). Finally, the article discusses the role of meaning as a transcendental component of psychosocial meaning-making coping processes and tries to highlight how shared writing experiences can stimulate personal and communal healing processes in the wake of social crises.

Keywords: COVID-19, Meaning-making, Psychosocial theory, Spiritualty, Transcendence

Societies worldwide were not prepared for COVID-19, neither in terms of healthcare capacity nor institutional organization (Higgins et al., 2020). The pandemic has disrupted well-established social dynamics—from the global to the local—affecting the stability of individuals’ meaning frameworks, their daily tasks of sense-making, and their ordinary ways of experiencing the world (e.g., Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). These changes have undermined various dimensions of people’s health, while the physical distancing and domestic quarantine measures designed to counteract the spread of the virus have eroded familiar psychosocial coping resources, making it harder to participate in communities or social networks (e.g., Brooks et al., 2020). Because COVID-19 will likely persist for a long time, it is vital that we address these diminished psychosocial coping resources while also renewing public health policies. In light of this need, this paper presents the results of a digital community project called Viral Epistolary (VE), a letter-writing and letter-sharing initiative carried out in Italy during the first wave of the pandemic. The project aimed to mitigate the potential mental health consequences of Italy’s harsh lockdown measures by providing a relational space for people to share their domestic isolation, physical distancing, and pandemic experiences. Letters, in this case, were used as the medium and as the meaning-making and (auto)biographical tool amongst a community of sense-makers, and we analyzed their contents from a spiritual psychosocial perspective to understand how meaning-making has a spiritual dimension, helping people to escape material conditions and restore transcendental meanings.

The first wave of COVID-19 in Italy

COVID-19 was first detected in early November 2019 in Wuhan—the capital city of China’s Hubei province—and it became globally prevalent within five months. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern (WHO, 2021b), and on March 11 they declared it a pandemic (WHO, 2021c). Since then, the virus has abruptly and radically changed all domains of life, from the individual and social to the economic and political (WHO, 2021a). Populations have faced different waves of the pandemic and multiple peaks in infections. According to Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE), which maintains a COVID-19 dashboard, more than four million people had lost their lives to the virus as of September 3, 2021 (Johns Hopkins CSSE, 2021). Although vaccines started to be available in the first months of 2021, new virus variants and low vaccination rates in developing countries still pose enormous obstacles to eradicating the virus for good.

Amongst the Western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic countries, Italy was the first to experience the full scope of the pandemic’s debilitating effects (Boccia et al., 2020). The first cases were detected on January 29, 2020, at the Spallanzani Hospital in Rome, and the Italian government decreed a state of emergency just days later, on January 31. The so-called “first wave,” however, started at the beginning of March 2020 and lasted until mid-June 2020. Hard national lockdown measures were instated on March 11, when all Italian territories were declared a “red zone.” This entailed suspending all unnecessary movement, establishing and enforcing a daytime curfew, closing all social places, and adopting domestic isolation and physical distancing measures (Paterlini, 2020). These lockdown measures were challenging for many people, exacerbating existing social issues such as domestic violence while creating new problems for mental health and personal and corporate finance. Sadly, these consequences could not be dealt with appropriately as social, economic, and political activities were totally curtailed by the virus. The Italian Health Service was unprepared to receive thousands of hospital patients, and, consequently, intensive care units were quickly saturated, with ever-diminishing supplies of oxygen tanks and public health personnel. Moreover, the pressure to control the pandemic lowered the standards of territorial medicine, furthering the confusion of the general population. Thus, the consequences of the first wave were tremendous, taking the lives of more than 30,000 Italian citizens, especially in Northern Italy where the virus first circulated. Thankfully, all subsequent waves (from the end of October 2020 to the beginning of June 2021) were better managed as the Italian government deployed a more complex management system and initiated a vaccination campaign (Bontempi, 2021).

Framing COVID-19 as more than a public health problem: a question of meaning-making

Due to its global scale, COVID-19 has gained scientific attention across all scientific domains. This interest can also be attributed to the virus’s more than medical effects—how it has shaped and impacted people’s life domains. Indeed, COVID-19 is more than a pandemic; it is a syndemic, as The Lancet editor Richard Horton named it (Horton, 2020), or a total social fact (Mauss, 1923-24/2012)—a phenomenon that penetrates every aspect of social and personal life. Attending to this fact shifts the emphasis from solely public health concerns to multidimensional processes of personal, interpersonal, and social meaning-making. Indeed, Markham et al. (2020) explained that one of the challenges for the human, social, and psychological sciences is figuring out how to approach COVID-19 from the perspective of personal and collective meaning-making. The aim of meaning-making should be to understand people’s lived experiences and to formulate new kinds of relationships between the self and the other, or between humans and the planet, through macro- and micro-level analysis. Therefore, lines of inquiry are heterogeneous, ranging from loss, mental health, and prosocial or destructive social behaviors to the social, economic, and political transformations triggered by COVID-19 (e.g., Miller, 2020). The issue of meaning crosses disciplinary boundaries.

For example, from a cultural anthropological perspective, Erll (2020) noted that new social rhythms are emerging, requiring us to reframe the concepts of time and the past and the role of collective memory before, during, and after COVID-19. Similarly, in cultural sociology, Demertzis and Eyerman (2020) described COVID-19 as a “compressed or virtual cultural trauma,” while Alexander and Smith (2020) defined it as a “natural experiment” that allows us to analyze a new set of collective representations associated with the virus. From this vantage point, the first phases of the pandemic are an incredible example of the societal and individual capacity for high-speed, meaningful bricolage. This is why Matthewman and Huppatz (2020) called for a broad sociology of COVID-19, interpreted as a “social experiment,” that should examine the social production and development of pandemics and associated vulnerabilities.

In the field of psychology, there have been calls to explore the psychosocial responses to emerging infections (Loveday, 2020). This approach is based on Strong’s (1990) epidemic psychology, which is the dominant psychosocial model of early responses to fatal epidemics. Notably, epidemic psychology acknowledges three types of psychosocial epidemics: an epidemic of fear (and of suspicion, irrationality, and stigma), an epidemic of explanations (a volatile intellectual state) or of moral controversy, and an epidemic of actions or proposed actions. Furthermore, due to its disruptive and unexpected nature, COVID-19 can also be understood via the theoretical framework of liminality (Stenner, 2017) insofar as it promotes spontaneous liminal experiences (Stenner et al., 2017)—moments that suspend people’s conventional ways of organizing their experiences, requiring that they reframe several aspects of their lives. Lost between a vanishing past and a vague future, and complicated by the psychosocial momentum of the pandemic, the present becomes a moment of psychological and social transformation (i.e., a “meanwhile” that is lived and narrated in the present continuous tense; Kapferer, 2004).

Spirituality and health: meaning-making as transcendent activities

From a historical perspective, spirituality and religion have always been important concepts in the psychosocial analysis of human ways of being (e.g., Parsons, 2010; Říčan, 2004; Valsiner et al., 2016). Many have tried to clarify both concepts and their relationships from a theoretical, empirical, and meta-analytical standpoint (Bauer & Johnson, 2018; Demmrich & Huber, 2019; Gall et al., 2011; Jastrzębski, 2020; Schwab, 2013), often to prevent them from being reduced to catch-all terms (Rose, 2001) or cultural buzzwords (Watts, 2020). For example, Richardson (2013) rejected notions of religion or spirituality that frame the self as an encapsulated entity that must withdraw from the modern world in order to achieve enlightenment or sanctity. He used Thomas Long’s writings and the concept of strong relationality to dispute the contemporary tendency to abstract from everyday life and objectify the world, thus highlighting how spiritual experiences are often mutual—a collaborative process of seeking what is important and worthwhile. Moreover, he used Berger’s notion of many realities to explain how mystical experiences open a sacred space through which people can discover richer dimensions of everyday life. In another seminal work, Pargament (1997) argued that spirituality, or the search for the sacred, exceeds the notion of higher powers. Furthering this distinction, Watts (2020) drew a conceptual boundary between the study of spirituality and the study for spirituality and identified three common assumptions associated with the word “spirituality”: a semantic shift from religiosity to spirituality, a deep cultural affinity with Romanticism, and historical roots in the 1960s. Westerink (2012) asserted that the term “spirituality” is perceived as vague because it arises in areas where different intellectual, religious, and cultural values coexist; thus, spirituality is more than a fashionable or trending concept—it is a broad category that encompasses different religious contents and theological projects.

The effort to define spirituality continues to be important, as many reviews and meta-analyses that describe the state of the art highlight. For example, Harris et al. (2018) reviewed major definitions of the term in the relevant literature, finding that spirituality was associated with eight concepts: “an internal emphasis, a belief system, a relationship, an ultimate concern, meaningfulness, self-enhancement, self-transcendence, and monism” (p. 5). Meanwhile, Santos and Michaels (2020) applied a partial prototype analysis to understand how laypeople conceptualize spirituality. Their study, which framed spirituality as a prototypical phenomenon, identified six main dimensions of spirituality: self and values, religious belief, existential connection, life force, transcendence, and meaning. Therefore, what makes spirituality interesting to study with regard to meaning-making processes and health is that, using Chirico’s definition (Chirico, 2021, p. 152), spirituality refers “to a morality-oriented intellectual connectedness with the self, others and the entire universe that is guided by a connection with the Transcendent and Superior. It includes the concepts of meaningfulness, completeness and connectedness, which provide coherent meaning, love and happiness.” Indeed, it is well established that spirituality can be an important determinant of well-being and health, especially in critical circumstances (e.g., Del Castillo, 2020).

Therefore, the spiritual dimension in psychosocial meaning-making and coping processes inherently refers to the transcendental meanings that can be identified while engaging in such processes. We designed our research to shed light on such connections.

Writing as a dialogical narrative and meaning-making practice

Qualitative research often touts the importance of narrative as a meaning-making process (e.g., Bamberg, 2006; Smith & Sparkes, 2008). Whether philosophy (e.g., Ricoeur, 1984, 1991), cultural psychology (Bruner, 1993; Polkinghorne, 1991), or interactionist/linguistic approaches in sociology (De Fina & Georgakopoulou, 2008), all human and social science disciplines regard narrative as a psychosocial practice that makes the world through meaningful stories. Narrative can assume many different forms, but in the last few decades there has been renewed interest in written texts (archives, digital texts, etc.), especially in the genre of letters and epistolaries within (auto)biographical studies (Jolly, 1999). Letters and epistolaries are documents of life, sociohistorical practices, and sites of engagement whereby writers construct and reflect upon their identities in a dialogical, reflexive, and emergent manner (Georgakopoulou, 2006; Stanley, 2004; Tamboukou, 2011, 2020). Thus, writing such a document involves a psychological effort—exercised within a cultural and sociohistorical frame—to reflect upon and reframe one’s life in connection with someone or something else (e.g., Tokarska et al., 2019; Vannier, 2018). For example, Bolger et al. (2003) explained the utility of diary methods for capturing what Allport (1942) called the “particulars of life”—that is, life as it is lived while it unfolds. By generating such “life documents” (Allport, 1942), diary methods allow researchers to closely examine experiences and reports in a natural and spontaneous context. Furthermore, they grant uncommon access to rare or specific phenomena. From a psycholinguistic perspective, Venuleo et al. (2020) used semiotic cultural psychosocial theory to explore the symbolic universes through which Italian people represent the pandemic and its meanings, thereby bridging subjective experiences and social interpretations of lockdown measures. On the clinical side, Negri et al. (2020) adopted Pennebaker’s “expressive writing method” to collect writings about the Lombardy region’s confinement period, which they used to study the linguistic markers of emotional regulation and elaboration. Key to this effort was the concept of psychological emergency, a state of mind that can be triggered by a single traumatic event or, significantly, by the broader and more complex context in which the event takes place.

Thus, VE can be defined as a spontaneous-emergent network of solidarity, a digital experience-sharing community that fosters cooperative meaning-making (Elcheroth & Drury, 2020), a communal means of coping with large-scale events (Polizzi et al., 2020), and a use of social media to maintain social networks during times of crisis (Wiederhold, 2020). By deploying VE in the midst of COVID-19, we hoped to explore how participants regarded and depicted the pandemic and the consequent physical distancing and domestic isolation measures. Additionally, we sought to understand the lockdown’s impact on meaning-searching and meaning-making processes and to observe how respondents utilized spirituality, implicitly or explicitly, as a tool to navigate the suspension of ordinary experience. We believe that the resulting insights contribute to the psychosocial literature on how global-scale, traumatic, and disruptive events are interpreted by individuals within an experience-sharing community. Finally, we believe that our research can contribute to a community-oriented psychology of religion, as suggested by Bingaman (2020) and Nelson (2012), and to an understanding of digital tools in this setting.

The research

Viral epistolary: project organization

As stated in the introductory paragraph, VE was an online community project that sought to create communal experiences during a COVID-19 lockdown in Italy through digital letter-writing and reading practices.

The VE project worked as follows. We first created a website and complementary Facebook and Instagram profiles with general information about the project (aims and modes of participation). We then invited people all over the country to join the community (i.e., subscribe) through a social media campaign and third-party profiles. All participants subscribed to our epistolary feed and received some basic writing instructions through which they were invited to share their domestic isolation experiences in an open manner (specifically, 10 tips were provided: be simple; try to use details; write it as a gift; be kind; take all the time you need; ask questions; help those who are in need; use not only words but also sounds, paintings; enjoy yourself; and, if you want, re-read). We offered three modes of participation. First, people could send their letters by email to VE, at which point we would forward them to all the people who had subscribed. These were called “prompt letters,” and they were distributed daily throughout the 85-day lockdown. Second, people could simply subscribe to receive the emails/letters. Third, people could answer the prompt letters, thereby beginning a correspondence with the original writer. Answering was very simple; in every letter, subscribers could find an external, private link where they could upload their responses.

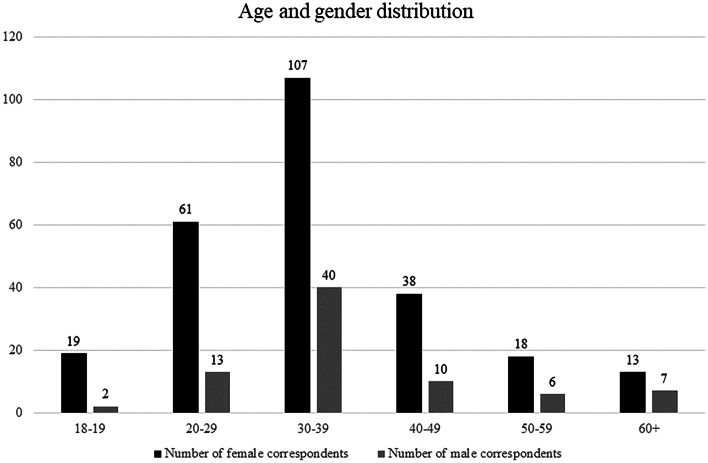

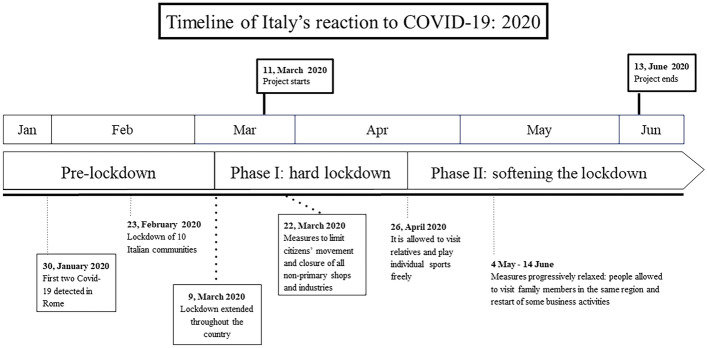

Table 1 shows the age and gender distribution of the 332 people who actively participated (that is, subscribed to the project epistolary feed) in the three-month project, which proceeded throughout Italy’s hard lockdown (from the beginning of March 2020 to the beginning of June 2020—see Fig. 1). Most of the participants were Italian, though three were French, two were English, and two were Spanish. All participants were proficient at writing in Italian and so did not require translation assistance (excerpts of letters were later translated into English; see below). We received a total of 340 letters written by 172 unique participants (the remaining 160 active subscribers read the epistolary feed with a 90% rate of opening); 85 of the letters were prompt letters, and the remaining 255 were correspondence letters. The average length of the letters was 800 words. The Facebook and Instagram pages amassed around 2,500 followers cumulatively (followers could read only some of the prompt letters), and the website tracked more than 20,000 interactions. Finally, all subscribers (whether writers or readers) signed the informed consent in which they agreed to the online publication of their letters and their use in our study.

Table 1.

Age and Gender Distribution of Participants

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 in Italy and the Viral Epistolary Project

Methodology

After assembling the archive of letters from the epistolary exchanges, we began our qualitative analysis. This method of inquiry is well established across the social and human sciences, and it encompasses several different modes of data collection, most of them based on (auto)biographical narratives from different media. Hence, we decided to use thematic analysis to evaluate our data (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Polkinghorne, 1995). More precisely, we developed a hybrid version of thematic analysis through an iterative and abductive analytical process that mixes bottom-up and top-down techniques, making it both flexible and consistent (e.g., Testoni et al., 2019).

Therefore, we first familiarized ourselves with the entire corpus of data and then, secondly, began to code the 85 prompt letters and the associated 255 correspondence letters. Three researchers participated in the coding process. They worked autonomously and held daily group discussions to assess consensus and reliability in the ways data were being coded. Each had been trained in this method and had previously adopted it in other psychosocial qualitative studies. Moreover, at the end of the analysis, they discussed and revised their results with the other two researchers involved. As stated earlier, we adopted a constant comparative strategy, which means that once major categories (or subthemes) started to emerge from the codes, we turned to the rest of the correspondence letters to evaluate the persistence of these categories and to explore related insights. Eventually, new nuances emerged that enriched and fortified the original themes, as is the goal with thematic analysis. We conducted the analysis with the support of Atlas.ti, a software program that allows researchers to store all their data in a unique file (for hermeneutical unity), to code excerpts of data, to track and monitor coding activity in a dedicated folder, and to create categories (subthemes or families) and themes (superfamilies). Finally, all the coding process, from letters excerpts, codes, subthemes, and themes, was translated into English for scientific communication purposes.

Findings

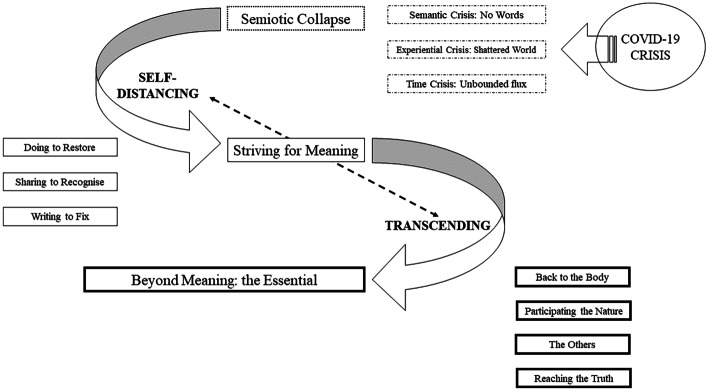

Three themes emerged from our analysis: Semiotic Collapse, Striving for Meaning, and Beyond Meaning: The Essential (see Fig. 2). These themes emerged as movements within a three-part (though not necessarily sequential) process of collapsing, self-distancing, and transcending.

Fig. 2.

Results of the Thematic Analysis

Semiotic collapse

The theme Semiotic Collapse gathers all the letters and/or excerpts that refer to the loss or failure of a well-established set of meanings for understanding one’s own experiential milieu. The first subtheme, Semantic Crisis: No Words, refers to the absence of any previous meaning or life vocabulary that could help to conceptualize the pandemic. N. [female, 20–29] expresses this absence in the following statement: “When we go out again, maybe for a beer, we will laugh—we will be (apparently) happy. But something inside us will have changed forever. We will feel a sensation, perhaps of emptiness, that we can hardly describe.” Similarly, M. [male, 30–39] states at the end of her letter, “This is how an absurd plot, to which I paid no attention at the beginning, wrote itself, making pain and astonishment its main protagonists.” S. [female, 40–49] highlights the process of becoming attuned to thoughts that used to be suppressed by daily habits, witnessing their ambiguous nature and power:

[Much like how], when we’re in the dark, we rely more on hearing and touch, we are now developing—perhaps all of us, perhaps not—a greater sensitivity to concepts that we used to be able to ignore more easily. The hectic daily routine was perhaps an ointment, a way of fooling ourselves, an antidote to the ills that afflict us and that were easier to escape. Now we are here, standing still. We find ourselves in a muddy cloud in which it is hard to navigate. We try to float, but is that really what we want?

The second subtheme, Existential Crisis: Shattered World, illustrates the dissolution or fragmentation of one’s meaning-making framework—and, by extension, of the world. S. [female, 40–49] writes:

I do not remember in my life such conflicting, mixed, sometimes merged, sometimes opposed sensations and not being able to give them an order, a ranking. Fear certainly led the way, but it did not work alone; another element usually accompanied it, and when it appeared, everything went out of control: impotence. . . . More than two months after the beginning of the nightmare, I struggle to remember, to relive, as if my mind wanted to keep [these feelings] far away, confused, hidden. . . . I feel more serene, but I am always confused; I would like to reflect or plan, but I cannot—I lack the basic tools. . . . It’s impossible to hold on to a thought that you can’t hold with your hands, that you can’t put in a plan, that doesn’t connect to anything before or after, that you don’t know how to place or where to place it.

C. [female, 20–29] also captures the feeling of her world fading away:

I feel as though I have been holding the threads of a very dense net in my hands, and that, as long as my hands remained clenched, the rest of the world would remain closed in on itself, holding its breath with me, finally still, for the first time since I can remember, instead of forcing me to run after it. I had the false sense that I was one of the centers of that sleeping world and that . . . I could have dragged everything with me, cradling it, and then come back down with my feet, returning it to its precarious balance again, just in the span of a breath—the changing height of a belly that rises and falls with the air that inflates and deflates it. . . . We wanted to break down the superfluous, the useless, the fixed residue of heavy thoughts that had to be supplanted by others in order to rediscover the beautiful, the useful, the holy and strictly necessary. And then? It’s all here again, or rather, here as always; and so, now that I have to slowly let go of the threads, I feel them like the ropes of a moored boat that are loosening and falling, and the boat is moving, but I remain on the dock.

The third subtheme, Temporal Crisis: Unbounded Flux, refers to time as an aleatory force, “bleeding” out and stretching beyond former temporal frames. L. [male, 40–49] expresses this sentiment as follows:

I have lost all sense of time. The days go by one after the other. I feel “forced” to stay at home, perhaps because when nothing significant happens in my life, I don’t even have anything significant to say. The word “perhaps” is a sign, for me, of the loss of certainty and security, both with regard to the present and, even more so, to the future.

V. [female, 20–29] describes this feeling in a similar way:

I often arrive at the end of the day angry with myself for not having used all the time I have at my disposal in a fair and constructive manner. Then I ask myself, fair for whom? Constructive for whom? I reproach myself because I should be studying and writing my postgraduate dissertation, but I cannot; I cannot stay focused for more than five minutes. I do not read novels because, if I must read, I must read the books for my dissertation, and in the end, I do not do either. It is an endless vortex of guilt.

R. [female, 50–59] defers to philosophy to make her point:

Until yesterday, I had managed to develop a kind of Bergsonian idea of time, convinced that it was flowing and that, somehow, we were passing through it more slowly than ever. Terrible and imposing as never before, finally re-emerging from the thousands of daily circumstances with which we willingly obscure it in an attempt to circumvent it. But what is the face of time? Have we ever dated it? Have we ever tried to give it a physiognomy? How strange, then! Now that we can perceive it almost as if it had the consistency of flesh, we feel that it is cruelly taken away from us. Time is circular, it contracts and expands at the same time without us being able to enclose it in a form. All this is now visible to the naked eye.

Striving for meaning

The theme Striving for Meaning refers to all the writings and narratives where the writers expressed their struggles in finding new ways of experiencing everyday life. All three subthemes fall within the self-distancing phase of psychosocial meaning-making.

The first subtheme, Writing to Fix, refers to the respondents’ use of writing to express and externalize their feelings, giving them a precise space that can be observed with proper detachment. G. [male, 20–29], reflecting on her days in lockdown, says:

Sitting at my desk, I find myself eager to pick up a pen and paper, but the blank sheet of paper reminds me of the emptiness that surrounds me, so I decide to write on the spur of the moment. I hear the sound of the tip of the pen as I write, which unexpectedly provides some consolation.

A. [male, 60 +] states:

I am sorry, I promised myself I would not write anything that would make you feel bad. I am writing because I want to exorcise this fear and, at the same time, put it in a positive context. Because my lists, with the many things to do and the initiatives that are taking place, are proof of how I am—and I think you too are—inside something that stubbornly tries to go on, despite everything. And if there is this desire for normality—if we continue, even in the distance, to look for each other, to organize ourselves, to feel united—something can be recovered.

A. [female, 30–39] responds to F.’s [male, 40–49] doubts about the usefulness of writing, saying:

Writing is one of the pleasant things in life. I do not believe, as you say, that it serves no purpose—not even in your case. Writing is a way of giving ourselves attention that we often deny ourselves because we are always busy with something. And what you write about yourself gives me the impression that you are stingy with your attention to yourself. Evidently, you are constantly attentive to what you do or think, you are always observing yourself, and yet it seems to me that you only look at yourself from the outside, as though you were other than yourself, like a judging eye, condemning you from the outside.

The second subtheme, Sharing to Recognize, refers to the respondents’ attempts to externalize their meaning-making projects by sharing them with someone else. For example, V. [male, 18–19] writes:

I am staying with my parents at home, with my boyfriend away. Anyway, even though my parents’ everyday presence and my boyfriend’s absence are tough, we really talk a lot, in a very different way from usual. Asking “how are you?” and “how do you feel?” is not merely routine anymore. These are important moments where you have the chance to share what is going on with you.

The third subtheme, Doing to Restore, describes the respondents’ reliance on a schedule to express a more cogent sense of time than the aleatory time they are experiencing. E. [female, 30–39], for example, notes: “I don’t know which day it is anymore, so I have started planning my activities. I use a notebook to list all my bullet points. It helps me a lot because it restores a feeling of differentiation between days and weeks.”

Beyond meaning: the essential

The theme Beyond Meaning: The Essential refers to texts, dialogues, and excerpts in which the experience or the feeling of having established a higher sense of one’s own life is expressed through rediscovering something very essential. All four subthemes fall within the transcending phase of psychosocial meaning-making.

The first subtheme, Back to the Body, describes how respondents achieved transcendence by moving from immanent, contextual meanings to essential ones. G. [female, 50–59] writes:

I take a moment on this strange day that started badly to breathe. . . . I breathe in, letting fresh air into my lungs, feeling my diaphragm drop and my belly swell. I stay like this for a couple of seconds and then I exhale, feeling my abdomen slowly deflate. There, I am alive. I feel it. Every now and then I have to stop and remind myself.

P. [male, 30–39] echoes this thought, writing:

Not all went well: I immediately fell ill with a fever and many symptoms with which I do not want to bore you . . . , but which still, a month later, debilitate my body and, even more so, my mind. . . . [T]oday I have decided to stop everything. I am going back to silence, listening only to my body. I will try to cleanse my body—which I have intoxicated with drugs—and my spirit, which I have intoxicated with bad thoughts.

S. [female, 40–49] also returns to the foundational rhythm of the breath:

So, what do you do to give meaning to your days? Yes, read, listen to audio books, cook, watch films and TV series, listen to music, listen to friends, study (which is never enough!), exercise, take theater lessons, do, do, do. But then what? What is left to give meaning to these strange days, to this strange time that leaves us as if suspended in the cosmic ether, but at the same time makes us feel like birds confined in a cage? I do not know. I start humbly from the origins. I breathe. I stay. And I feel alive.

The second subtheme, Participating in Nature, highlights how nature and natural forces help to ground people’s feelings in a broader framework. L. [male, 20–29] writes:

This moment in which everything seems to be suspended and immobile leaves little room for distraction, and, consequently, many people—including you—are exploiting it (even against their will) to look inside themselves. However, if I were you, I would try to apply your great gifts of observation to the external environment for once. Stop observing yourself and start observing the world outside, its inexorable flow, and its most banal manifestations: the alternation of day and night, the arrival of spring, despite the apparent patina of absolute stasis of these [lockdown] days. Perhaps you will discover in this process of forgetting yourself that you are part of a whole that continues to breathe, letting yourself go to the wave of that breath and surprising yourself by understanding that even this forgetful abandonment—the same that you feel during intercourse and that I believe many people have in common—is not something detached from you. On the contrary, it is entirely part of you, or rather, it is the most spiritual part of you that flies away to join the other and rejoin the whole.

Fittingly, D. [female, 20–29] addresses her letter to the sea:

I miss touching you, smelling you. I miss the residue you leave on my skin, in my hair. I ask your forgiveness on behalf of myself and many others. Forgive us one day for all that has been and all that will be. We, your children, do not learn easily. And like your waves perpetually breaking on the rocks, we humans need to bang our heads against the wall many times to realize that our actions are possibly harmful, dangerous, and stupid. But you know, maybe this time we can dare to say that change will come. You must have wondered why we no longer cross you. We have not disappeared, we have not left you alone; you are in our hearts, in our memories, in our photos, in our letters. We just moved away a little, giving you a chance to refresh yourself, to feel free. Perhaps, as I said, we have understood the importance of life. And you, my dear neighbor, are above all this.

The third subtheme, The Others, involves imagining and cherishing one’s significant others. A. [male, 40–49] writes:

I miss people’s faces, too; the first two weeks, which I spent completely alone, were the most difficult from this point of view. They made me realize how human contact, even fleeting—a glance, a smile returned by a stranger—is fundamental nourishment for the mind and soul.

L. [female, 50–59] commiserates:

What I want to say to those of you who are reading: if you have a boyfriend/girlfriend, a partner, or any person who makes you feel good in this quarantine, thank them. Enjoy these days, forget about unnecessary things, make love, play cards, drink wine, listen to music, prepare a bath with candles everywhere. Realize the rarity of this moment, of this time, of what you have. . . . If you are with your family, thank life. Shave your father’s or brother’s hair—it might be satisfying. I have done it.

I. [female, 20–29] puts the feeling very concisely, writing, “She [I. is referring to her grandmother] now spends a lot of time together with the people she has always adored the most. They eat and chat together, laugh, reminisce and... stay. Just being. Something forgotten for a long time: the sense of being.”

The fourth subtheme, Reaching Truth, is well illustrated by G.’s [male, 30–39] words:

I have realized how important small gestures, small attentions are when they are made with the heart. I have really understood which people are really close to me, and which are just passing through. . . . I have realized that people who I thought were my friends have actually shown themselves to be what they really are. I’m not a person who criticizes or makes up things about other people, but this period has opened my eyes to how selfish people can be when the occasion arises. Absolutely not. I realized that it is really good to take care of oneself, not only by taking care of the skin, flesh, and bones that we have, but also (and especially) of what is inside. I have understood that life is too short to be bitter about everything that surrounds us. I have understood.

On a briefer note, R. [female, 50–59] writes: “We are called upon to go back to basics, to face ghosts and weaknesses, to hopefully transform ourselves into a more evolved version of ourselves. Like a metamorphosis. And the process is inevitably painful.”

Discussion

As summarized in Fig. 2 and in the first theme of our analysis, our findings suggest that COVID-19 has prompted a threefold crisis: a semantic crisis (no words), an experiential crisis (shattered world), and a temporal crisis (unbounded flux). These crises generate a condition of semiotic collapse—a perturbing dissolution of everyday meaning-making frameworks that leaves individuals unable to understand their existential milieu within the pandemic. What characterizes this semiotic collapse is a heightened affective state of astonishment after realizing that one’s ordinary, stable, and largely predictable life has been suspended. Domestic isolation and physical distancing measures form the material bases of this collapse by reducing access to usual life spaces and the meanings they afford.

As noted in the second theme, respondents deployed three strategies to distance themselves from the indistinctness of their new daily experiences: writing to fix, sharing to recognize, and doing to restore. All these self-distancing strategies embodied a striving for meaning in response to the impoverishment of life in lockdown. Where writing helps to organize random feelings and ever-changing thoughts, sharing (through writing and reading letters or through talking to loved ones) helps to foreground the timeless commonalities that still bond us. Finally, scheduling activities helps to structure time and bestow broader significance to otherwise empty activities. In other words, when a meaningful relation with/in the world is threatened by semiotic collapse, self-distancing triggers a striving for (contextual) meaning, which allows people to reactivate intersubjective experiences and identify new proto-forms of stability.

The last theme, Beyond Meaning: The Essential, refers to the restoration of a higher sense of the self amidst the pandemic. Here, the contextual meanings (or proto-forms of stability) achieved through self-distancing provide the foundations for transcendence—understood as the generalization of particular relations into higher truths or states of being. This experience often entails a deep and even mystical discovery as it provides access to an inner or hidden reality by leading respondents back to the body, to nature, to significant others, and finally to truth. In this way, semiotic meanings become modes of self-organization.

Overall, the findings show that, following a multidimensional crisis, self-distancing can open up a psychosocial space–time where new contextual meanings take root. Eventually, these meanings can transcend their original contexts, becoming stable and essential ways of experiencing/organizing life. In other words, transcendence is a form of meta-psychosocial reflection that extends the meaning-making process from (inter)personal spaces to a spiritual, sacred sphere. Arguably, our results highlight that this is not necessarily a sequential process and thus it does not have a causal temporal dimension. Indeed, what emerges from the writers’ letters is that each of them occupied a different position within the process and faced specific challenges. As an example, even in letters written toward the end of the 85-day lockdown, the saliency of the semiotic collapse was still active, with writers starting to recognize the meaning-making work they were probably about to face sometime soon. Therefore, the themes are to be considered as categories in their own right, with some participants expressing all of them and some expressing only some of them.

Previous literature has demonstrated that transcendence is a core human method for coping with stressful life situations (e.g., Borgen, 2017). Our findings resemble those of Van Tongeren and Showalter Van Tongeren (2021), who elaborated the existential positive psychology model of suffering by adding the triad of existential concern, existential anxiety, and cultivating meanings. Similarly, Zhang et al.’s (2021) systematic review of spiritual fortitude, or the ability to draw on spiritual resources (i.e., self-distancing and transcending) during times of crisis, highlights the pertinency of our results. Fisher (2010) work on the four-domains model of spiritual health and well-being, which encompasses the personal, communal, environmental, and transcendental domains, is also compatible with our findings insofar as these domains embody the contexts for human sense-making. Moreover, our findings are consistent with the recent critical reinterpretation of Maslow’s theory (e.g., Koltko-Rivera, 2006; Louca et al., 2021).

On the other hand, as other important psychosocial and community-oriented studies conducted in Italy have shown (e.g., Aresi et al., 2020; Compare et al., 2021; Gatti & Procentese, 2021), there is still the need to develop effective people-community relationships projects that can act as meaningful drivers of recovery processes under stressful or traumatic circumstances (Procentese et al., 2021). At the same time, cross-national surveys have highlighted the fundamental role of a meaning-centered coping style (e.g., Eisenbeck et al., 2022), which is the strongest predictor of physical and mental health among the different coping strategies used for dealing with COVID-19 implications. Moreover, Castiglioni and Gaj (2020) called for a nonmedical intervention toward the general population, founded in meaning-making processes, which uses narratives, metaphors, a sense of predictability, and coherence (all of them very important in a dialogic writing experience) to help individuals and communities to deal with the psychosocial burden of the pandemic.

Moreover, these findings can have important operative implications. For example, as writing can be a healing practice during a traumatic experience, future studies could measure the post-traumatic growth of people who participate in this kind of intervention and people who do not. In this way, our conclusions could be better supported.

Limitations

Our research has two main caveats, which we highlight for future studies to address. First, we did not collect detailed relevant social and demographic information (apart from age, gender, and place of domicile) from our participants due to the nature of the project and the recruitment method. Specifically, we designed the procedures of subscription and participation (whether in the form of writing, corresponding, or reading) to be easily accessible, open, and friendly. Therefore, we did not want to ask for more details and decided to let such information emerge from the writings. However, it could have been useful to know, for instance, whether the participants had a loved one who had COVID-19 or to gather more structured background data with a set of multiple-choice questions derived from the literature (e.g., whether they considered themselves religious, spiritual, or neither; how they were continuing to engage in social relationships; how they would define their feelings and emotions). In light of the above, further studies could use a deeper sociodemographic approach to gather more background information and use this source of data to strengthen the interpretation of data or explore a new level of analysis. Additionally, though the relational dimensions of the epistolary exchanges are important, our unit of analysis was not the specific correspondence texts and the replies to them (that is, the micro-interactions created between writers and respondents). Further studies could focus closely on how meanings are interpersonally negotiated in the temporal dialogic dimension of correspondence by analyzing correspondence practices as creating semiotic border spaces where recursive processes of exchange, identification, and differentiation take place.

Funding

No funding to declare.

Availability of Data and Material

Data are all available online; the raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The research followed the APA’s Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate

All participants signed an informed consent for the participation to the project.

Consent for Publication

All participants signed an informed consent for the publication of their contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ciro De Vincenzo, Email: ciro.devincenzo@phd.unipd.it.

Adriano Zamperini, Email: adriano.zamperini@unipd.it.

References

- Alexander JC, Smith P. COVID-19 and symbolic action: Global pandemic as code, narrative, and cultural performance. American Journal of Cultural Sociology. 2020;8(3):263–269. doi: 10.1057/s41290-020-00123-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G. W. (1942). The use of personal documents in psychological science. Social Science Research Council Bulletin, 49, xix + 210.

- Aresi, G., Procentese, F., Gattino, S., Tzankova, I., Gatti, F., Compare, C., Marzana, D., Mannarini, T., Fedi, A., Marta, E., & Guarino, A. (2020). Prosocial behaviours under collective quarantine conditions. A latent class analysis study during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. 10.31234/osf.io/jb5hw [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bamberg M. Stories: Big or small. Narrative Inquiry. 2006;16(1):139–147. doi: 10.1075/ni.16.1.18bam. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AS, Johnson TJ. Conceptual overlap of spirituality and religion: an item content analysis of several common measures. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. 2018;21(1):14–36. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2018.1437004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bingaman KA. Religious and spiritual experience in the digital age: Unprecedented evolutionary forces. Pastoral Psychology. 2020;69(4):291–305. doi: 10.1007/s11089-020-00895-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boccia S, Ricciardi W, Ioannidis JP. What other countries can learn from Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020;180(7):927. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54(1):579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi, E. (2021). The Europe second wave of COVID-19 infection and the Italy strange situation. Environmental Research, 193, 110476. 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Borgen B. The human mental transcending ability as a coping and life-expanding resource. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. 2017;20(1):70–93. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2017.1330130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3532534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. (1993). Acts of meaning: Four lectures on mind and culture. Harvard University Press.

- Castiglioni, M., & Gaj, N. (2020). Fostering the reconstruction of meaning among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 567419. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.567419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chirico F. Spirituality to cope with COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and future global challenges. Journal of Health and Social Sciences. 2021;6(2):151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Compare C, Prati G, Guarino A, Gatti F, Procentese F, Fedi A, Aresi GU, Gattino S, Marzana D, Tzankova I, Albanesi C. Predictors of prosocial behavior during the COVID-19 national lockdown in Italy: Testing the role of psychological sense of community and other community assets. Community Psychology in Global Perspective. 2021;7(2):22–38. doi: 10.1285/i24212113v7i2p22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Fina A, Georgakopoulou A. Analysing narratives as practices. Qualitative Research. 2008;8(3):379–387. doi: 10.1177/1468794106093634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del Castillo FA. Health, spirituality and COVID-19: Themes and insights. Journal of Public Health. 2020;43(2):e254–e255. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demertzis N, Eyerman R. COVID-19 as cultural trauma. American Journal of Cultural Sociology. 2020;8(3):428–450. doi: 10.1057/s41290-020-00112-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmrich, S., & Huber, S. (2019). Multidimensionality of spirituality: a qualitative study among secular individuals. Religions, 10(11), 613. 10.3390/rel10110613

- Eisenbeck, N., Carreno, D. F., Wong, P., Hicks, J. A., María, R. G., Puga, J. L., Greville, J., Testoni, I., Biancalani, G., López, A., Villareal, S., Enea, V., Schulz-Quach, C., Jansen, J., Sanchez-Ruiz, M. J., Yıldırım, M., Arslan, G., Cruz, J., Sofia, R. M., & García-Montes, J. M. (2022). An international study on psychological coping during COVID-19: Towards a meaning-centered coping style. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 22(1), 100256. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2021.100256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elcheroth G, Drury J. Collective resilience in times of crisis: Lessons from the literature for socially effective responses to the pandemic. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2020;59(3):703–713. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erll, A. (2020). Afterword: Memory worlds in times of Corona, Memory Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698020943014

- Fisher J. Development and application of a spiritual well-being questionnaire called SHALOM. Religions. 2010;1(1):105–121. doi: 10.3390/rel1010105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gall TL, Malette J, Guirguis-Younger M. Spirituality and religiousness: a diversity of definitions. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. 2011;13(3):158–181. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2011.593404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, F., & Procentese, F. (2021). Local community experience as an anchor sustaining reorientation processes during COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(8), 4385. 10.3390/su13084385

- Georgakopoulou A. Thinking big with small stories in narrative and identity analysis. Narrative Inquiry. 2006;16(1):122–130. doi: 10.1075/ni.16.1.16geo. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KA, Howell DS, Spurgeon DW. Faith concepts in psychology: Three 30-year definitional content analyses. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2018;10(1):1–29. doi: 10.1037/rel0000134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins R, Martin E, Vesperi MD. An anthropology of the COVID-19 pandemic. Anthropology Now. 2020;12(1):2–6. doi: 10.1080/19428200.2020.1760627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. Lancet. 2020;396(10255):874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzębski, A. K. (2020). The challenging task of defining spirituality. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 1–19. 10.1080/19349637.2020.1858734

- Johns Hopkins CSSE. (2021). COVID-19 map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Jolly M. Defining a field: The encyclopedia of life writing. Auto/biography Studies. 1999;14(2):309–316. doi: 10.1080/08989575.1999.10815225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, B. (2004). Ritual dynamics and virtual practice: Beyond representation and meaning. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Social and Cultural Practice, 48(2), 35–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23178856. Accessed 3 Sept 2021.

- Koltko-Rivera ME. Rediscovering the later version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Self-transcendence and opportunities for theory, research, and unification. Review of General Psychology. 2006;10(4):302–317. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.10.4.302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Louca E, Esmailnia S, Thoma N. A critical review of Maslow’s theory of spirituality. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health. 2021;23:1–17. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2021.1932694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loveday H. Fear, explanation and action—The psychosocial response to emerging infections. Journal of Infection Prevention. 2020;21(2):44–46. doi: 10.1177/1757177420911511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham AN, Harris A, Luka ME. Massive and microscopic sense making during COVID-19 times. Qualitative Inquiry. 2020;27(7):759–766. doi: 10.1177/1077800420962477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthewman S, Huppatz K. A sociology of COVID-19. Journal of Sociology. 2020;56(4):675–683. doi: 10.1177/1440783320939416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss, M. (1923–24/2012). Essai sur Le Don: Forme et raison de l’échange dans Les societes archaïques [The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies]. Presses Universitaires de France.

- Miller ED. The COVID-19 pandemic crisis: The loss and trauma event of our time. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2020;25(6–7):560–572. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2020.1759217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negri, A., Andreoli, G., Barazzetti, A., Zamin, C., & Christian, C. (2020). Linguistic markers of the emotion elaboration surrounding the confinement period in the Italian epicenter of COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 568281. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nelson JM. Taking community seriously: a theory and method for a community-oriented psychology of religion. Pastoral Psychology. 2012;61(5–6):851–863. doi: 10.1007/s11089-012-0454-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and spirituality? Yes and no. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 1997;9(1):3–16. doi: 10.1037/e568022011-002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons WB. On mapping the psychology and religion movement: Psychology as religion and modern spirituality. Pastoral Psychology. 2010;59(1):15–25. doi: 10.1007/s11089-009-0210-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paterlini, M. (2020). On the front lines of coronavirus: The Italian response to COVID-19. BMJ, 368, m1065. 10.1136/bmj.m1065 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(6):510–512. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polizzi C, Jay Lynn S, Perry A. Stress and coping in the time of COVID-19: Pathways to resilience and recovery. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17(2):59–62. doi: 10.36131/CN20200204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne DE. Narrative and self-concept. Journal of Narrative and Life History. 1991;1(2–3):135–153. doi: 10.1075/jnlh.1.2-3.04nar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne DE. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 1995;8(1):5–23. doi: 10.1080/0951839950080103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Procentese F, Gatti F, Ceglie E. Sensemaking processes during the first months of COVID-19 pandemic: Using diaries to deepen how Italian youths experienced lockdown measures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(23):1–19. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Říčan PR. Spirituality: The story of a concept in the psychology of religion. Archive for the Psychology of Religion. 2004;26(1):135–156. doi: 10.1163/0084672053597996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson FC. Investigating psychology and transcendence. Pastoral Psychology. 2013;63(3):355–365. doi: 10.1007/s11089-013-0536-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and narrative, vol. 1 (K. McLaughlin & D. Pellauer, Trans.). University of Chicago Press.

- Ricoeur, P. (1991). From text to action: Essays in hermeneutics, II (K. Blarney & J. B. Thompson, Trans.). Northwestern University Press.

- Rose S. Is the term spirituality a word that everyone uses, but nobody knows what anyone means by it? Journal of Contemporary Religion. 2001;16(2):193–207. doi: 10.1080/13537900120040663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, C., & Michaels, J. L. (2020). What are the core features and dimensions of spirituality? Applying a partial prototype analysis to understand how laypeople mentally represent spirituality as a concept. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12. 10.1037/rel0000380

- Schwab JR. Religious meaning making: Positioning identities through stories. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2013;5(3):219–226. doi: 10.1037/a0031557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley L. The epistolarium: on theorizing letters and correspondences. Auto/biography. 2004;12(3):201–235. doi: 10.1191/0967550704ab014oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, Sparkes AC. Contrasting perspectives on narrating selves and identities: an invitation to dialogue. Qualitative Research. 2008;8(1):5–35. doi: 10.1177/1468794107085221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stenner P. Liminality and experience. Palgrave Macmillan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stenner P, Greco M, F. Motzkau J. Introduction to the special issue on liminal hotspots. Theory & Psychology. 2017;27(2):141–146. doi: 10.1177/0959354316687867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strong P. Epidemic psychology: a model. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1990;12(3):249–259. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11347150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamboukou M. Interfaces in narrative research: Letters as technologies of the self and as traces of social forces. Qualitative Research. 2011;11(5):625–641. doi: 10.1177/1468794111413493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamboukou, M. (2020). Epistolary lives: Fragments, sensibility, assemblages in auto/biographical research. In The Palgrave Handbook of Auto/Biography (pp. 157–164). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Testoni I, Bingaman K, Gengarelli G, Capriati M, De Vincenzo C, Toniolo A, Zamperini A. Self-appropriation between social mourning and individuation: a qualitative study on psychosocial transition among Jehovah’s witnesses. Pastoral Psychology. 2019;68(6):687–703. doi: 10.1007/s11089-019-00871-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tokarska U, Dryll E, Cierpka A. Letter to a grandchild as a narrative tool of older adults’ biographical experience exploration. Narrative Inquiry. 2019;29(1):29–49. doi: 10.1075/ni.18049.tok. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tongeren, D. R., & Van Tongeren, S. A. S. (2021). Finding meaning amidst COVID-19: an existential positive psychology model of suffering. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Valsiner, J., Marsico, G., Chaudhary, N., Sato, T., & Dazzani, V. (Eds.) (2016). Psychology as a science of human being: The Yokohama Manifesto. Springer.

- Vannier M. The power of the pen: Prisoners’ letters to explore extreme imprisonment. Criminology & Criminal Justice. 2018;20(3):1–19. doi: 10.1177/1748895818818872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venuleo, C., Marinaci, T., Gennaro, A., & Palmieri, A. (2020). The meaning of living in the time of COVID-19. A large sample narrative inquiry. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Watts G. Making sense of the study of spirituality: Late modernity on trial. Religion. 2020;50(4):590–614. doi: 10.1080/0048721x.2020.1758229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westerink H. Spirituality in psychology of religion: a concept in search of its meaning. Archive for the Psychology of Religion. 2012;34(1):3–15. doi: 10.1163/157361212x644486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold BK. Using social media to our advantage: Alleviating anxiety during a pandemic. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2020;23(4):197–198. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.29180.bkw. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021a). Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 response. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline?gclid=CjwKCAjw0qOIBhBhEiwAyvVcfyg4uaokOrVq99XSiB3NaIqlyZDZ6R4LTmYvSPNb_gehCvJ7LBckjhoCRgAQAvD_BwE#event-2

- World Health Organization. (2021b). WHO director-general’s statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)#.XrwxQJ0aVqI.link. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

- World Health Organization. (2021c). WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed 3 Aug 2021.

- Zhang, H., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Davis, E. B., Aten, J. D., McElroy-Heltzel, S., Davis, D. E., Shannonhouse, L., Hodge, A. S., Captari, L. E. (2021). Spiritual fortitude: a systematic review of the literature and implications for COVID-19 coping. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 8. 10.1037/scp0000267

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are all available online; the raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.