Abstract

Outbreaks of food-borne listeriosis have often involved strains of serotype 4b. Examination of multiple isolates from three different outbreaks revealed that ca. 11 to 29% of each epidemic population consisted of strains which were negative with the serotype-specific monoclonal antibody c74.22, lacked galactose from the teichoic acid of the cell wall, and were resistant to the serotype 4b-specific phage 2671.

Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b has been implicated in ca. 40% of sporadic cases of listeriosis and in most major food-borne epidemics (2, 5, 14). Several of the high-impact outbreaks which took place in Europe and North America during the past two decades involved one clonal lineage. In North America, this lineage was implicated in the 1981 Nova Scotia coleslaw outbreak (41 cases; 18 deaths) (13), as well as in the 1985 Jalisco (Spanish-style) cheese outbreak in Los Angeles (142 cases; 48 deaths) (11). The lineage possesses a characteristic restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) (20) and also has a modification of DNA at GATC sites, possibly reflecting the presence of a cognate restriction endonuclease that may serve as a defensive strategy against phage invasion (21). At least two other genetically distinct serotype 4b lineages have been implicated in food-borne outbreaks in North America: one was associated with the New England outbreak of 1983 (49 cases; 14 deaths) and was epidemiologically linked to contaminated pasteurized milk (4), whereas the other was responsible for the 1998-to-1999 multistate outbreak of listeriosis (101 cases; 21 deaths), in which Listeria-contaminated hot dogs were implicated (1).

In earlier work we described monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) c74.22 and c74.33, which reacted with strains of serotype 4b, 4d, and 4e but with no other L. monocytogenes serotypes (8). The MAbs appear to recognize surface antigenic determinants associated with sugar substituents on the teichoic acid of the cell wall (9, 12). As a rule, serotype 4b isolates of food or clinical origin reacted strongly with these MAbs, with the notable exception of two clinical strains from the Nova Scotia and New England outbreaks which were positive with c74.33 but negative with c74.22 (8). It would seem important to determine whether this special phenotype (c74.22 negative, c74.33 positive) was also seen in other clinical isolates from the same outbreak population and in implicated food or environmental isolates. Therefore, we examined the incidence of c74.22-negative strains among a large number of isolates from three separate epidemics of listeriosis (the New England and Nova Scotia outbreaks and the Jalisco cheese outbreak).

The outbreak populations which we surveyed in this study were chosen on the basis of the availability of multiple isolates from the same outbreak. The strains were derived from the Listeria strain collection maintained at the National Animal Disease Center and are listed in Table 1. All strains were of serotype 4b. The strains were maintained at −70°C with minimal passaging in the laboratory and were grown as previously described (8). The Jalisco cheese outbreak isolates included 18 clinical isolates, as well as 11 food isolates and 16 environmental isolates from the implicated cheese plant. Of the 26 Nova Scotia outbreak-associated strains, 24 were clinical and only two strains were available from the implicated food (coleslaw). The New England outbreak strains were all of clinical origin, as the etiologic agent was never isolated from the implicated food source (milk) or from the environment (4).

TABLE 1.

Reactivities with MAbs c74.22 and c74.33 and sensitivities to phage 2671 of L. monocytogenes strains from three outbreaks

| Strain | Origina | Reactivity to:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c74.22 | c74.33 | φ2671b | ||

| LMJL1 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMJL2 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL3 | Jalisco, clinical/ | − | + | R |

| LMJL4 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL5 | Jalisco, clinical/ | − | + | R |

| LMJL6 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMJL7 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL8 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL9 | Jalisco, clinical/ | (+)c | + | S |

| LMJL10 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMJL11 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL12 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL13 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL14 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMJL15 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL16 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMJL17 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL18 | Jalisco, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMJL19 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | |

| LMJL20 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | |

| LMJL21 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | S |

| LMJL22 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | |

| LMJL23 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | |

| LMJL24 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | |

| LMJL25 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | |

| LMJL26 | Jalisco, cheese | + | + | S |

| LMJL27 | Jalisco, cheese | (+) | + | S |

| LMJL28 | Jalisco, cheese curd | + | + | |

| LMJL29 | Jalisco, Mexican sour cream | (+) | + | S |

| LMJL30 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL31 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL32 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL33 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL34 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL35 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL36 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | − | + | R |

| LMJL37 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL38 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | |

| LMJL39 | Jalisco, cheese plant/ | + | + | S |

| LMJL40 | Jalisco, cheese plant, cooler condensate | + | + | |

| LMJL41 | Jalisco, cheese plant, ants, flies, debris | + | + | |

| LMJL42 | Jalisco, cheese plant, ants | + | + | |

| LMJL43 | Jalisco, cheese plant, pasteurizer | + | + | |

| LMJL44 | Jalisco, cheese plant, drain | + | + | |

| LMJL45 | Jalisco, cheese plant, sodium caseinate | + | + | |

| LMNS1 | Nova Scotia, placenta | − | + | R |

| LMNS2 | Nova Scotia, endometrium | + | + | S |

| LMNS3 | Nova Scotia, placenta | + | + | |

| LMNS4 | Nova Scotia, placenta | − | + | R |

| LMNS5 | Nova Scotia, throat | − | + | R |

| LMNS6 | Nova Scotia, vagina | + | + | S |

| LMNS7 | Nova Scotia, blood | − | + | R |

| LMNS8 | Nova Scotia, blood | + | + | S |

| LMNS9 | Nova Scotia, blood | + | + | |

| LMNS10 | Nova Scotia, blood | + | + | |

| LMNS11 | Nova Scotia, blood | + | + | |

| LMNS12 | Nova Scotia, blood | + | + | |

| LMNS13 | Nova Scotia, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMNS14 | Nova Scotia, stillborn | + | + | |

| LMNS15 | Nova Scotia, throat | (+) | + | |

| LMNS16 | Nova Scotia, clinical/ | − | + | R |

| LMNS17 | Nova Scotia, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMNS18 | Nova Scotia, throat | + | + | |

| LMNS19 | Nova Scotia, umbilicus | − | + | R |

| LMNS20 | Nova Scotia, stool | + | + | |

| LMNS17 | Nova Scotia, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMNS18 | Nova Scotia, throat | + | + | |

| LMNS19 | Nova Scotia, umbilicus | − | + | R |

| LMNS20 | Nova Scotia, stool | + | + | |

| LMNS21 | Nova Scotia, placenta | − | + | R |

| LMNS22 | Nova Scotia, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMNS23 | Nova Scotia, vagina | + | + | S |

| LMNS24 | Nova Scotia, baby | + | + | S |

| LMNS25 | Nova Scotia, coleslaw | + | + | |

| LMNS26 | Nova Scotia, coleslaw | + | + | |

| LMNE1 | New England, clinical/ | − | + | R |

| LMNE2 | New England, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMNE3 | New England, clinical/ | + | + | S |

| LMNE4 | New England, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMNE5 | New England, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMNE6 | New England, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMNE6 | New England, clinical/ (“Scott A”) | (+) | + | |

| LMNE8 | New England, clinical/ | + | + | |

| LMNE9 | New England, clinical/ | + | + | |

Outbreak and source of isolate. Jalisco, Jalisco cheese outbreak. Slash marks indicate that no data about the exact site or organ were available.

R, resistant to phage 2671; S, phage sensitive; blank, not determined.

Plus signs in parentheses indicate that the strain was c74.22 positive but that reactivity was reduced.

All Nova Scotia and Jalisco cheese epidemic-associated strains listed in Table 1 had the epidemic clone-specific RFLP in the ltrB genomic region, which is involved in the ability of the pathogen to grow at low temperatures (20), and the DNA modification characteristic of this epidemic clonal lineage, which rendered their DNA resistant to digestion by Sau3AI (21). In contrast, strains of the New England outbreak lacked this DNA modification and the ltrB-specific RFLP (20, 21) and constitute an independent epidemic-associated lineage. Earlier studies have shown that the New England outbreak strains were genetically closely related to each other (19).

Strains were screened with c74.22 and c74.33 by means of colony immunoblots carried out as described elsewhere (10). All strains were positive with c74.33. In contrast, several were found to be c74.22 negative, completely lacking a color signal in the colony immunoblots (Table 1). The c74.22-positive or c74.22-negative phenotype was reproducible and stable following repeated passages in the laboratory. Furthermore, repeated screenings of c74.22-negative strains failed to identify any c74.22-positive revertants.

The frequency of c74.22-negative strains varied among the three epidemic-associated populations, as summarized in Table 2. Among clinical isolates, c74.22-negative strains were most common in the Nova Scotia outbreak population (29.2%). Of the food and environmental isolates from the Jalisco cheese outbreak, 1 of 16 environmental isolates and none of 11 food isolates were c74.22 negative. The negative isolates from the Nova Scotia outbreak were all of clinical origin. The two available isolates from the implicated food (coleslaw) were both c74.22 positive (Tables 1 and 2). In addition to the c74.22-negative strains, each population also harbored a small number of isolates which were c74.22 positive, but at reduced levels (the blue color intensity in the colony immunoblots was approximately one-fourth of that produced by c74.22-positive strains). Interestingly, strain Scott A (LMNE6), extensively used in bacteriologic studies, was one such c74.22-reduced strain.

TABLE 2.

Incidence of MAb c74.22-negative, phage 2671-resistant strains within epidemic populations of L. monocytogenes

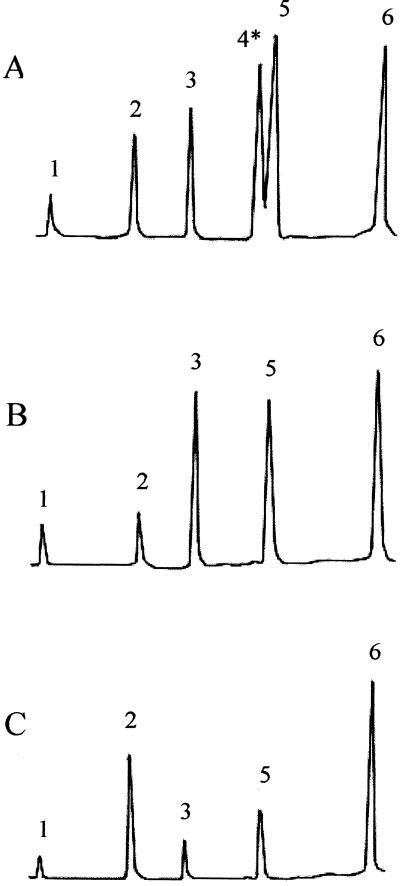

Genetic and biochemical studies suggest that teichoic acid glycosylation is required for reactivity of L. monocytogenes serotype 4b with c74.22 (10, 12). To determine whether teichoic acid glycosylation was impaired in the c74.22-negative epidemic strains, we used previously described methods (3, 7, 16) to determine the cell wall composition of six c74.22-negative clinical isolates (strain LMJL3, from the Jalisco cheese outbreak; strains LMNS1, LMNS4, LMNS16, and LMNS21, from the Nova Scotia outbreak; and strain LMNE1, from the New England outbreak [Table 1]). One c74.22-positive strain from the Jalisco cheese epidemic was also included (strain LMJL21) and was confirmed to have a teichoic acid composition typical of serotype 4b strains (Fig. 1A), with galactose and glucose as substituents on the N-acetylglucosamine in the teichoic acid backbone of this serotype (3, 7, 16). In contrast, the teichoic acids of all six c74.22-negative strains lacked galactose. Glucose, however, was present, at wild-type levels in four strains (LMJL3, LMNS1, LMNS16, and LMNS21) and at somewhat reduced levels in two strains (LMNS4 and LMNE1). The structural implications of the apparent reduction in glucose levels of the teichoic acids of the latter strains were not investigated further. Representative gas chromatographs are shown in Fig. 1B (strain LMJL3) and Fig. 1C (LMNS4).

FIG. 1.

Teichoic acid composition in epidemic-associated strains. (A) Strain LMJL21 (c74.22-positive); (B and C) c74.22-negative strains LMJL3 and LMNS4, respectively. Peaks: 1, glycerol; 2, anhydroribitol; 3, ribitol; 4, galactose; 5, glucose; 6, glucosamine. The position of the galactose peak has been marked by an asterisk. Note the absence of the galactose peak in panels B and C. Glucose (peak 5) is present in all three strains, although at reduced levels in panel C. Teichoic acids were prepared as described previously (3, 16).

In L. monocytogenes, teichoic acid sugar substituents have been shown to serve as receptors for serotype-specific phage (15, 18). Infections with the serotype 4b-specific phage 2671, carried out as described elsewhere (21), revealed that the c74.22-negative epidemic-associated strains were all resistant to this phage. Strains with reduced reactivity to c74.22 were phage sensitive and were indistinguishable in this regard from c74.22-positive isolates (Table 1).

The resistance of the c74.22-negative bacteria appeared to be related to failure of the phage to adsorb, since phage adsorption assays (15) with strains LMJL1 and LMJL3 (c74.22-positive and c74.22-negative clinical isolates, respectively, from the Jalisco cheese outbreak [Table 1]) showed a significant (10- to 20-fold) decrease in phage adsorption onto the c74.22-negative cells (data not shown). The receptor for serotype 4b-specific phage has been shown to be the N-acetylglucosamine of the teichoic acid (18). Since this teichoic acid component is normal in these strains (Fig. 1), we can conclude that galactose on the teichoic acid either is required for normal presentation of the phage receptor or may serve as the receptor itself.

The observed stability of the c74.22-positive and c74.22-negative phenotypes suggests that the c74.22-negative strains are not likely to be simple laboratory variants. In our experience with numerous serotype 4b strains, we never encountered loss of c74.22 reactivity in response to growth conditions, laboratory storage, and/or repeated subculturing. In fact, reactivity with c74.22 is one of the most stable phenotypes in laboratory cultures of serotype 4b bacteria and is present in all sporadic strains of serotype 4b which we have screened to date (8; Z. Lan and S. Kathariou, unpublished data). We therefore hypothesize that the epidemic-associated c74.22-negative strains were present in the vehicle of infection or, alternatively, that they represent spontaneous mutants of c74.22-positive bacteria that became established in the course of infection in certain patients. Unfortunately, we lack food isolates specifically linked to those patients who yielded the c74.22-negative strains. In the two outbreaks from which food-derived strains were available, however, all examined food-derived isolates were c74.22 positive (Table 1), although we cannot exclude the possibility that c74.22-negative strains might have been identified in a larger population of food isolates.

The alternative hypothesis, that the c74.22-negative phenotype became established independently in different patients in the course of their infection by c74.22-positive bacteria, may deserve consideration. The c74.22-specific antigen is constitutively expressed on the surfaces of serotype 4b cells, at least when they are grown in vitro (8), and sugar substituents on teichoic acids have been shown to be strong immunogens (7, 17). Thus, strains lacking expression of this surface antigen may be at an advantage in terms of immune system evasion. Individual variation in the immune statuses of the patients, as well as possible strain-specific determinants, may account for the observed variation in the incidence of c74.22-negative strains among outbreaks and from one patient to another.

The phage resistance that accompanies the c74.22-negative phenotype and the altered teichoic acid glycosylation would also be expected to confer a selective advantage on bacteria in foods and in the environment. However, only 1 of 29 food and environmental epidemic-associated strains was found to be c74.22 negative (Table 1). In our opinion, selective pressure for loss of the phage receptor may be low for these strains, which are already substantially phage resistant (21), probably due to a preexisting restriction-modification system(s).

The genetic basis for the c74.22-negative phenotype of the epidemic-associated strains described here remains to be identified. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of the Jalisco cheese outbreak strains LMJL1 and LMJL3 (c74.22 positive and negative, respectively) showed that the strains had identical patterns (R. Y. Kanenaka, personal communication). Genomic fingerprinting using repetitive element PCR (6) also yielded identical patterns (E. M. Meleshkevich and S. Kathariou, unpublished data). This suggests that the c74.22-negative phenotype was not accompanied by detectable genomic rearrangements. In addition, the mutation does not appear to be located in the recently described gtcA gene, mutations in which render the bacteria c74.22 negative (but still c74.33 positive) and result in a loss of galactose and a marked reduction in glucose levels in the teichoic acids of the cell wall (12). The gtcA sequence, including the regulatory region, was identical between two c74.22-positive and c74.22-negative strains from the Jalisco cheese outbreak (12). It appears, therefore, that the mutation responsible for the c74.22-negative phenotype of LMJL3 resides not in gtcA but in another, as yet unidentified locus. These findings were in agreement with our cell wall analysis data, which showed that the c74.22-negative epidemic strains lacked galactose in the teichoic acids of the cell walls but still maintained glucose. In contrast, transposon-induced mutants in gtcA had only trace levels of glucose in the teichoic acids (12).

In conclusion, the three epidemic strain populations studied here appear to contain antigenically unique strains, the teichoic acid of which lacks the galactose substituents characteristic of serotype 4b. Studies of populations from additional epidemics, especially those involving novel lineages (e.g., the recent multistate outbreak of 1998 to 1999 [1]), will enhance our understanding of the population structure of epidemic-associated L. monocytogenes and may lead to better understanding of pathogen-host interactions in human food-borne listeriosis.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative AAFS grant 92-37201-8095 and by ILSI-North America. E. E. Clark was supported by a Haumana Program fellowship for minority student research participation.

We are grateful to J. Rocourt (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) for the gift of phage 2671 and to Zheng Lan for the phage adsorption assays. We also thank Wei Zheng, Edward Lanwermeyer, Thong Truong, and the other members of our laboratories for valuable feedback and support throughout the course of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 1998–1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;47:1117–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiedler F, Seger J, Schrettenbrunner A, Seeliger H P R. The biochemistry of murein and cell wall teichoic acids in the genus Listeria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1984;5:360–376. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleming D W, Cochi S L, MacDonald K L, Brondum J, Hayes P S, Plikaytis B D, Holmes M B, Audurier A, Broome C V, Reingold A L. Pasteurized milk as a vehicle of infection in an outbreak of listeriosis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:404–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502143120704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gellin B G, Broome C V. Listeriosis. JAMA. 1998;261:1313–1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jersek B, Tcherneva E, Rijpens N, Herman L. Repetitive element sequence-based PCR for species and strain discrimination in the genus Listeria. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;23:55–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamisango K, Fujii H, Okumura H, Saiki I, Araki Y, Yamamura Y, Azuma I. Structural and immunochemical studies of teichoic acid of Listeria monocytogenes. J Biochem. 1983;93:1401–1409. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kathariou S, Mizumoto C, Allen R D, Fok A K, Benedict A A. Monoclonal antibodies with a high degree of specificity for Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3548–3552. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3548-3552.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lei X-H. Molecular studies of surface antigens specific for serotype 4b Listeria monocytogenes. Ph.D. thesis. Honolulu: University of Hawaii; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei X-L, Promadej N, Kathariou S. DNA fragments from regions involved in surface antigen expression specifically identify Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4 and a subset thereof, cluster IIB (serotypes 4b, 4d, and 4e) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1077–1082. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1077-1082.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linnan M J, Mascola L, Lou X D, Goulet V, May S, Salminen C, Hird D W, Yonekura M L, Hayes P, Weaver R, et al. Epidemic listeriosis associated with Mexican-style cheese. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:823–828. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809293191303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Promadej N, Fiedler F, Cossart P, Dramsi S, Kathariou S. Wall teichoic acid glycosylation in serotype 4b Listeria monocytogenes requires gtcA, a novel, serogroup-specific gene. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:418–425. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.2.418-425.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlech W F, III, Lavigne P M, Bortolussi R A, Allen A C, Haldane E V, Wort A J, Hightower A W, Johnson S E, King S H, Nicholls E S, Broome C V. Epidemic listeriosis—evidence for transmission by food. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:203–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198301273080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuchat A, Swaminathan B, Broome C V. Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:169–183. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran H L, Fiedler F, Hodgson D A, Kathariou S. Transposon-induced mutations in two loci of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2a result in phage resistance and lack of N-acetylglucosamine in the teichoic acid of the cell wall. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4793–4798. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4793-4798.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchikawa K, Sekikawa J, Azuma I. Structural studies on teichoic acids in cell walls of several serotypes of Listeria monocytogenes. J Biochem. 1986;99:315–327. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ullman W W, Cameron J A. Immunochemistry of the cell walls of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1969;98:486–493. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.2.486-493.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wendlinger G, Loessner M J, Scherer S. Bacteriophage receptors on Listeria monocytogenes cells are the N-acetylglucosamine and rhamnose substituents of teichoic acids or the peptidoglycan itself. Microbiology. 1996;142:985–992. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wesley I V, Aston F. Restriction enzyme analysis of Listeria monocytogenes strains associated with food-borne epidemics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:969–975. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.969-975.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng W, Kathariou S. Differentiation of epidemic-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes by restriction fragment length polymorphism in a gene region essential for growth at low temperatures (4°C) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4310–4314. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4310-4314.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng W, Kathariou S. Host-mediated modification of Sau3AI restriction in Listeria monocytogenes: prevalence in epidemic-associated strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3085–3089. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3085-3089.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]