Abstract

Enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) is believed to be a non-invasive treatment for coronary artery disease and angina. The aim of this study was to determine the safety and effectiveness of EECP in refractory angina patients through a systematic reviews and meta-analysis. We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature published on PubMed, Cochrane library, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Trip Database and Google Scholar databases using appropriate keywords and specific strategy with no time limit. Having selected and screened the studies based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria and evaluating their quality based on the Cochrane checklist. For the meta-analysis,the Mantel-Haenszel method or the generic Inverse Variance was used. Analyses were done with Review Manager 5.2 software. A number of 299 studies were initially reviewed and finally, seventeen studies were included in the meta-analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Also, thirteen outcomes were analyzed and the results of meta-analysis in twelve outcomes including (Systolic Blood Pressure (7 studies), Diastolic Blood Pressure (7 studies), Pulse Pressure (4 studies), Mean Arterial Pressures (4 studies), Heart Rate (6 studies), Angina episodes (7 studies), Walking distance (2 studies),Canadian Cardiovascular Society classification (6 studies), Flow-Mediated Dilation (3 studies), Daily Nitrate Usage (4 studies), Exercise Treadmill Test-Time (2 studies), ST-segment depression (2 studies)demonstrated a significant clinical advantage in the EECP treatment effectiveness in patients with angina. No significant difference was observed regarding EECP usefulness (P = 0.18) in the outcome of brachial artery diameter (2 studies). Based on the meta-analysis, the results indicate the safety and effectiveness of EECP in patients with angina pectoris and indicate the usefulness of this treatment in these patients. In general, the authors believe that the general conclusion in this regard requires some studies with a large sample size and a control group assignment.

Keywords: Safety, Effectiveness, EECP, Angina, Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analysis

Introduction

The cardiovascular disease epidemic has plagued most countries worldwide. Although many cardiovascular diseases can be treated, it is still the leading cause of death in men and women throughout the world. 1

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 17.9 million people died of cardiovascular disease in 2019, accounting for 32% of all deaths per year. Of course, 85% of deaths are due to heart attack and stroke. 2 Cardiovascular mortality is predicted to account for more than 23.6 million per year by 2030. 3 The total cost incurred due to cardiovascular disease is reported to be $ 177.5 billion annually. 4

Cardiovascular diseases can be prevented through addressing behavioral risk factors such as smoking, unhealthy diet, obesity, physical inactivity and persistent alcohol use. People with cardiovascular disease or people at high cardiovascular risk need to be diagnosed and managed early through counseling and medication, if required. 2 Although drug and invasive treatments have increased life expectancy among many patients, many of these patients are resistant to these treatments.Angina, also known as angina pectoris, is chest pain, usually caused by blockage or spasm of the arteries that carry blood to the heart muscle. 5

Some patients with angina neither adequately react to medication, nor they respond well to myocardial revascularization. However, the desired treatment outcome cannot be achieved in some of these patients, because the risk-benefit ratio is not very considerable for myocardial revascularization. However, in some of these patients, the desired treatment outcome cannot be achieved because the risk-benefit ratio is not very attractive for myocardial revascularization. In all of these cases, enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) can be used as a potential treatment for chronic refractory angina. 6

EECP approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 1995. EECP was first introduced in the treatment of angina and was subsequently applied in various conditions including heart failure, ischemic cerebrovascular diseases and cardiomyopathy. EECP is a non-invasive mechanical, outpatient treatment for coronary artery disease (CAD) patients with refractory angina pectoris. Various studies have shown that EECP improves the symptoms of angina, myocardial ischemia, left ventricular function, and quality of life. 7-10 Patients for whom EECP treatment is effective may experience lasting benefits for up to 5 years after treatment. Therefore, EECP may be a long-term, cost-effective, non-invasive treatment for chronic angina. 11,12

Owing to the significant prevalence of refractory angina syndrome in population groups and the extent of results regarding the safety and effectiveness of EECP in the treatment of patients suffering from chronic angina, the present study was conducted as a systematic review and meta-analysis. The aim of this study was to determine the safety and effectiveness of EECP in refractory angina patients.

Methods

Search Strategy

Keywords including (EECP, enhanced external counterpulsation, external counter pulsation, angina) in PubMed, Cochrane library, Scopus, Science Direct, Trip databases were applied to garner research studies that reported on the safety and effectiveness of EECP technology with no time limit until May 2021.

For each database, a specific and appropriate search strategy was used according to query and its structured components. The Google Scholar search engine was used to look up relevant resources and complete the search coverage. The searched studies references were also used to find the related studies.

Selection of Studies

Initially, the studies obtained from electronic search and manual search were organized using EndNote software followed with screening and selection of studies through two stages based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the first stage, the titles and abstracts of the studies were reviewed after omitting the duplicate studies, and, the full text of the selected studies was collected and reviewed in the second stage. Then, the list of sources of the remaining studies was reviewed and, if necessary, the corresponding authors of important studies were contacted. Screening and selection of studies were performed by two reviewers (SH and MMJ) independently.

Finally, the process of searching and selecting studies was mapped using the PRISMA flow chart.

Eligibility criteria

Population: Angina patients;

Intervention: Enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP);

Outcome: Clinical efficacy, functional consequences, side effects and safety;

Type of studies: Trial and observational studies

Exclusion criteria were that; 1) Studies published in languages other than English or Persian; 2) Studies whose statistical data were incomplete or not reported at all; 3) Studies that have not evaluated the intended outcomes; 4) Studies without explicit methodology or results; 5) Studies whose population was arrhythmias leading to dysfunction, active thrombophlebitis, aortic aneurysms, significant valvular diseases, or pregnant women.

Risk of bias/quality assessment

Cochrane checklist were used to assess the risk of bias tool that assesses the risks of selection, performance, detection, attrition, and reporting. 13 Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias, and disagreements were resolved through discussion or consulting the third reviewer.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers extracted the data. In addition, we extracted the following variables: title of article, first author, year of publication, country, number of patient, type of study, statistical data related to each outcome, outcome follow-up time, and other useful information. After filling out the data extraction forms (designed in Excel), the disagreements were resolved through discussion or consulting the third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

Mean Difference (MD) and Inverse Variance (IV) method were used to pool the data in cases where the data was binary, the relative risk was used to pool the data using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test (CMH) test. Pooled estimates were performed using a random-effects model in case of heterogeneity; otherwise, fixed-effects model was used. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated using means of chi-square and I2 statistics. The I2 more than or equal to 40% was considered high statistical heterogeneity. 14 The proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each categorical factor. The meta-analysis was performed using RevMan Software (version 5.2).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

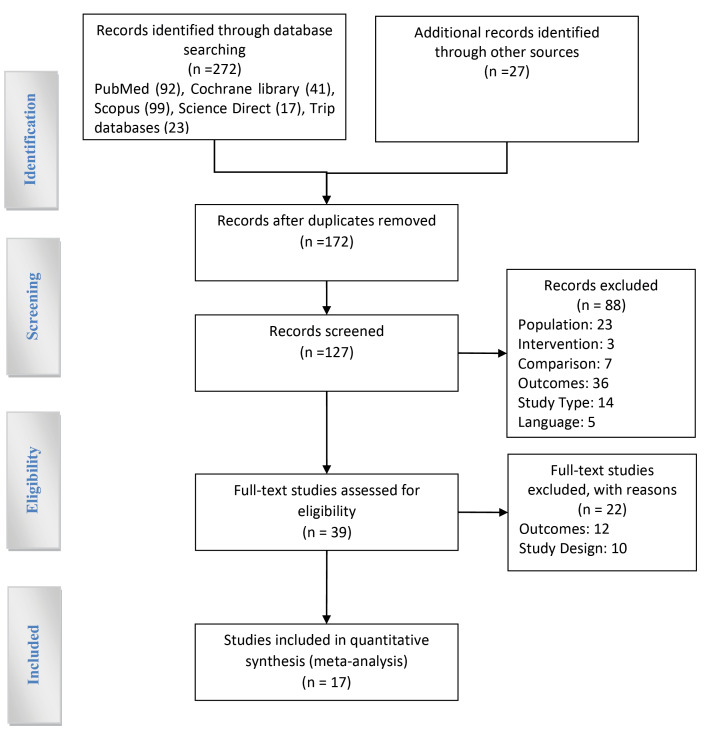

Databases search revealed 272 studies in the first stage, manual search and review added 27 studies to this number, which totaled 299 studies. Having deleted the common titles, we carried out an initial screening of 127 studies. After studying the title and abstract, 88 studies were omitted due to inconsistency with the purpose of the study. The full text of 39 studies was then assessed for eligibility. Finally, 17 studies were included in quantitative synthesis.

Figure 1 shows the process of searching and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for selection of studies for the systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA Diagram)

All the seventeen studies reviewed the desired outcomes and related statistical data before and after treatment of refractory angina pectoris patients with EECP. Of these seventeen studies, sixteen were clinical trials in which the total study population are 582 patients and was a type of cohort in which the study population included 450 patients. The mean age of patients was 27.1 years in the Gurovich study15 and 76.8 years in the Braverman study16 All studies were published between 1999 and 2020, (Table 1).

Table 1. Main characteristics of included studies.

| First author | Year | Country | Study Design | Mean age±SD | Sample Size | Population | Follow-up |

EECP

*

Sessions |

| Arora 17 | 1999 |

USA (New York) |

Clinical trials | 64 ± 9 | 71 | Angina and coronary artery disease | 4-7 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Beck 18 | 2014 |

USA (Rhode Island) |

Clinical trials | 64 ± 8 | 25 | Left ventricular dysfunction & coronary artery disease | 7 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Beck 19 | 2015 |

USA (Rhode Island) |

Clinical trials | 64.2 ± 2.6 | 10 | Left ventricular dysfunction | 7 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Bondesson 20 | 2010 | Sweden | Clinical trials | 69 | 100 | Refractory angina pectoris | 12 months | 35 1to 2-hour sessions |

| Braith 21 | 2010 |

USA (Florida) |

Clinical trials | 64.44 ± 9.63 | 28 | Coronary artery disease | 7 weeks | 35 1- hour sessions |

| Braverman 16 | 2013 |

USA (Pennsylvania) |

Clinical trials | 76.8 ± 7 | 86 | With Aortic Stenosis | 6 weeks | N.R |

| Casey 22 | 2008 |

USA (Rochester) |

Clinical trials | 63 ± 11 |

12 |

Angina pectoris | 7 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Casey 23 | 2011 |

USA (Rochester) |

Clinical trials | 64 ± 2 | 28 | Chronic Angina Pectoris | 7 weeks | 35 1- hour sessions |

| Dockery 24 | 2004 | UK | Clinical trials | 63.7 ± 6.7 | 23 | Patients with Angina | 7 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Gurovich 15 | 2013 | USA | Clinical trials | 27.1 ± 5 | 18 | Coronary artery disease and unstable angina | 4-7 weeks | 35 45-min to 1-hour sessions |

| Hashemi 25 | 2008 | Iran | Clinical trials | 63.93 ± 8.6 |

15 |

Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 1 month | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Kumar 26 | 2009 |

USA (New York) |

Clinical trials | 61 ± 8 | 47 |

Prior coronary revascularization who had chronic refractory angina pectoris |

12 months | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Michaels 27 | 2007 | USA | Clinical trials | 62 ± 10 | 24 | Chronic stable angina due to coronary artery disease | 7 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Nichols 28 | 2006 |

USA (Florida) |

Clinical trials | 61 ± 7.1 | 20 | Refractory angina pectoris | 7 to 8 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Soran 29 | 2007 | USA | Cohort | 69 ± 11 |

450 |

Refractory angina and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction |

6 months | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Tartaglia 30 | 2003 |

USA (New York) |

Clinical trials | 68 ± 9 | 25 | Angiographically proven coronary artery disease | 4-7 weeks | 35 1-hour sessions |

| Wu 31 | 2020 | Sweden | Clinical trials | 65.8 | 50 |

Refractory Angina Pectoris |

6 months | 35 1-hour sessions |

*Abbreviations: EECP, enhanced external counterpulsation; N.R, No Report

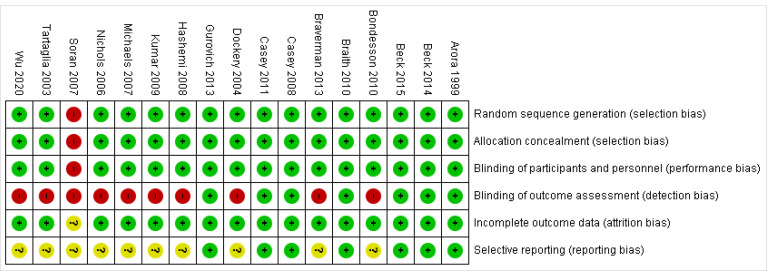

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias assessment of the studies showed that, 7 studies out of 17 studies were of good quality (low risk bias), one study was of low quality (high risk bias) and 9 studies were of moderate quality. The most important challenge for studies in Cochrane risk of bias items was related to item blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias). Also in the item selection reporting (reporting bias) 59% of the studies were unclear risk (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias item for each included study low risk bias, high-risk bias, unclear risk

Outcomes

After categorizing the outcomes of the 17 studies included in the present study, 13 outcomes were extracted: Systolic Blood Pressure (7 studies), Diastolic Blood Pressure (7 studies), Pulse Pressure (4 studies), Mean Arterial Pressures (4 studies), Heart Rate (6 studies), Angina episodes (7 studies), Walking distance (2 studies), Canadian Cardiovascular Society (6 studies), Flow-Mediated Dilation (3 studies), Daily Nitrate Usage (4 studies), Exercise Treadmill Test-Time (2 studies), ST-segment depression (2 studies) and brachial artery diameter (2 studies).11 outcomes were analyzed for clinical efficacy and functional consequences (Effectiveness) and 2 outcomes were analyzed as safety criteria.

Effectiveness

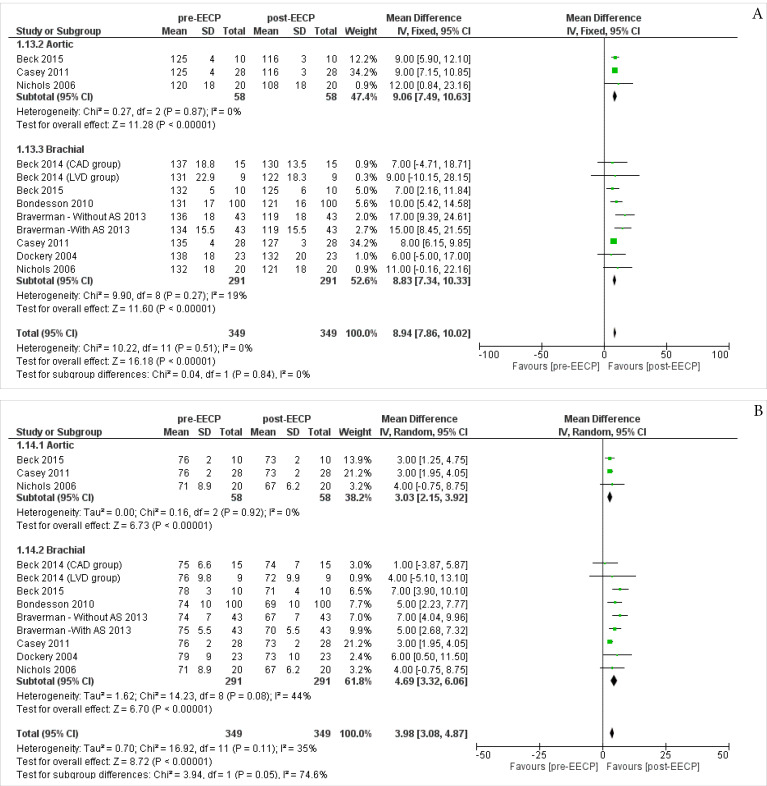

Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP)

Three studies 19,23,28 including 58 patients assessed the Aortic SBP outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Aortic SBP was 9.06 (95% CI; 7.49, 10.63) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 3A). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.87).

Figure 3.

Forest plot analysis of the (A) SBP (B) DBP

Seven studies 16,18-20,23,24,28 including 291 patients assessed the Barchial Systolic Blood Pressureoutcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Barchial SBP was 8.83 (95% CI; 7.34, 10.33) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 3A). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 19%, P = 0.27).

The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Aortic and Barchial SBP was 8.94 (95% CI; 7.86, 10.02) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.51).

Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP)

Three studies 19,23,28 including 58 patients assessed the Aortic DBPoutcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Aortic DBP was 3.03 (95% CI; 2.15, 3.92) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 3B). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.92).

Seven studies 16,18-20,23,24,28 including 291 patients assessed the Barchial DBPoutcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Barchial DBP was 4.69 (95% CI; 3.32, 6.06) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, P4). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 44%, P = 0.08).

The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Aortic and Barchial DBP was 3.98 (95% CI; 3.08, 4.87) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 35%, P = 0.11).

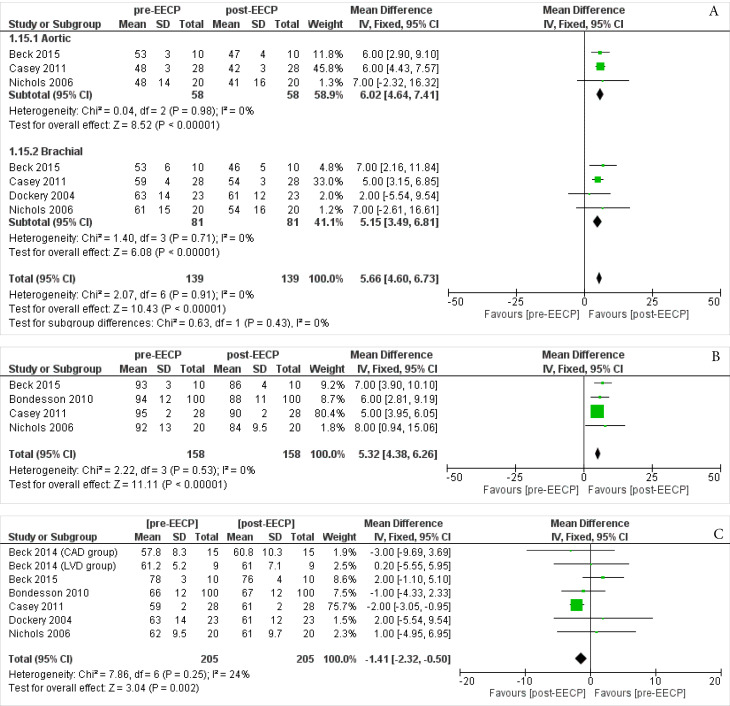

Pulse Pressure (PP)

Three studies 19,23,28 including 58 patients assessed the Aortic PPoutcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Aortic PP was 6.02 (95% CI; 4.64, 7.41) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 4A). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.98).

Figure 4.

Forest plot analysis of the (A) PP (B) MAP (C) Heart Rate

Four studies 19,23,24,28 including 81 patients assessed the Barchial PPoutcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Barchial PP was 5.15 (95% CI; 3.49, 6.81) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 4A). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.71).

The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Aortic and Barchial PP was 5.66 (95% CI; 4.60, 6.73) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.91).

Mean Arterial Pressures(MAP)

Four studies 19,20,23,28 including 158 patients assessed the MAP outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for MAP was 5.32 (95% CI; 4.38, 6.26) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 4B). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.53).

Heart Rate

Six studies 18-20,23,24,28 including 205 patients assessed the Heart Rate outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for Heart Rate was -1.41 (95% CI; -2.32, -0.50) in favor of the post-EECP (P = 0.002, Figure 4C). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 24%, P = 0.25).

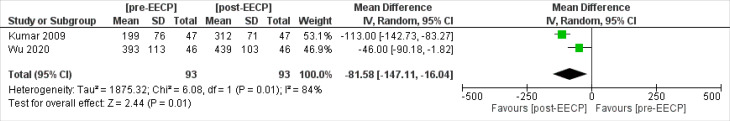

Walking distance

Two studies 26,31 including 93 patients assessed the walking distance outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for walking distance was -81.58 (95% CI; -147.11, -16.04) in favor of the post-EECP (P = 0.01, Figure 5). Test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 84%, P= 0.01).

Figure 5.

Forest plot analysis of the walking distance

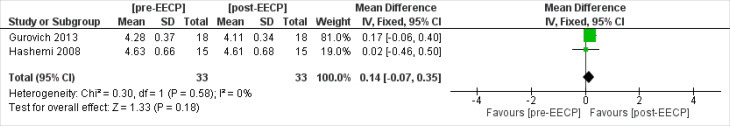

Brachial Artery Diameter

Two studies 15,25 including 33 patients assessed the brachial artery diameter outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for brachial artery diameter was 0.14 (95% CI; -0.07, 0.35). The result of meta- analysis this outcome showed that there was no statistically significant difference between post-EECP & pre-EECP in terms of this outcome (P = 0.18, Figure 6). Test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 84%, P = 0.01).

Figure 6.

Forest plot analysis of the Brachial Artery Diameter

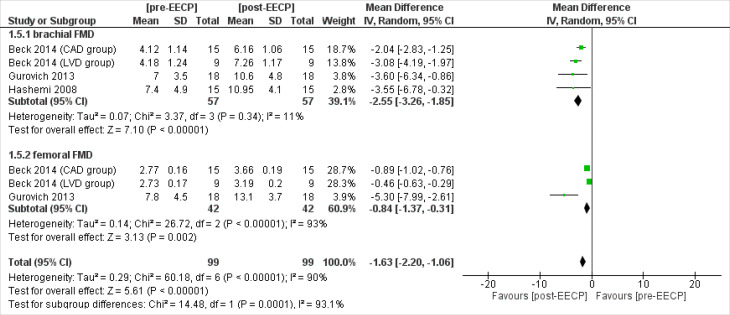

Flow-Mediated Dilation(FMD)

Three studies 15,18,25 including 57 patients assessed the brachial FMD outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for brachial FMD was -2.55 (95% CI; -3.26, -1.85) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 7). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 11%, P = 0.34).

Figure 7.

Forest plot analysis of the Flow-Mediated Dilation (FMD)

Two studies 15,18 including 42 patients assessed the femoral FMD outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for femoral FMD was -0.84 (95% CI; -1.37, -0.31) in favor of the post-EECP (P = 0.002, Figure 7). Test for heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2 = 93%, P < 0.00001).

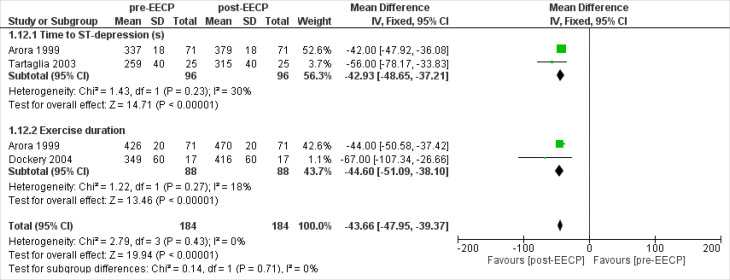

Exercise Treadmill Test-Time

Two studies 17,30 including 96 patients assessed the time to ST depression outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for time to ST depression was -42.93 (95% CI; -48.65, -37.21) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 8). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 30%, P = 0.23).

Figure 8.

Forest plot analysis of the Exercise Treadmill Test-Time

Two studies 17,24 including 88 patients assessed the exercise duration outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for exercise duration was -44.60 (95% CI; -51.09, -38.10) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 8). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 18%, P = 0.27).

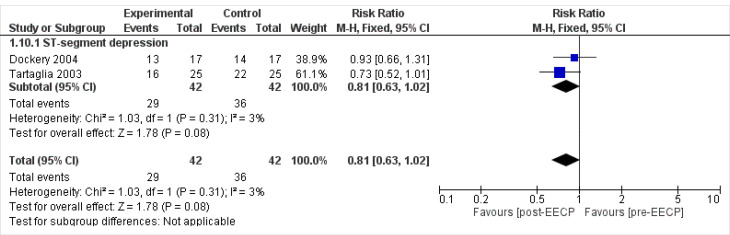

ST-segment depression

Two studies 24,30 including 42 patients assessed the ST depression outcomes of the patients. The overall Mantel-Haenszel Pooled RR calculated for ST depression was 0.81 (95% CI; 0.63, 1.02). The result of meta- analysis this outcome showed that there was no statistically significant difference between post-EECP & pre-EECP in terms of this outcome (P = 0.08, Figure 9). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 3%, P = 0.31).

Figure 9.

Forest plot analysis of the ST-segment depression

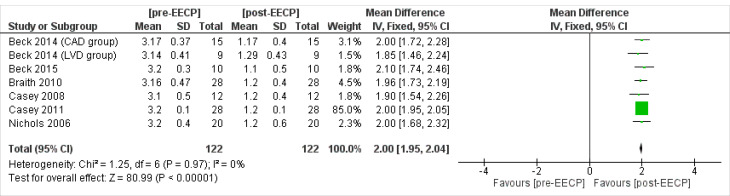

CCS classification (CCS angina class)

Six studies 18,19,21-23,28 including 122 patients assessed the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) angina class outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for CCS angina class was 2 (95% CI; 1.95, 2.04) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 10). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.97).

Figure 10.

Forest plot analysis of the CCS angina class

Safety

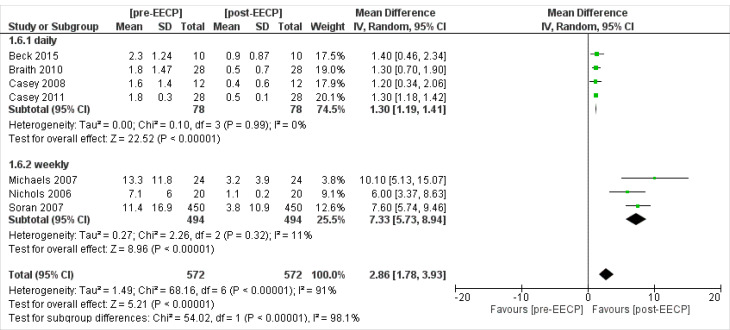

Angina episodes

Four studies 19,21-23 including 78 patients assessed the daily angina episodes outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for daily angina episodes was 1.30 (95% CI; 1.19, 1.41) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 11). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 0%, P = 0.99).

Figure 11.

Forest plot analysis of the Angina episodes

Three studies 27-29 including 494 patients assessed the weekly angina episodes outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for weekly angina episodes was 7.33 (95% CI; 5.73, 8.94) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 11). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 11%, P = 0.32).

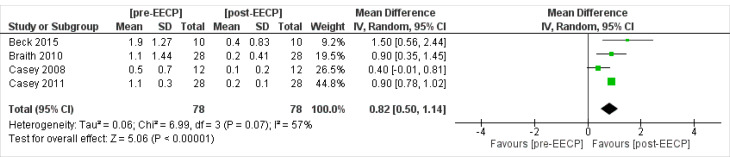

Daily Nitrate Usage

Four studies 19,21-23 including 78 patients assessed the daily nitrate usage outcomes of the patients. The overall Inverse Variance Pooled MD calculated for daily nitrate usage was 0.82 (95% CI; 0.50, 1.41) in favor of the post-EECP (P < 0.00001, Figure 12). Test for heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2 = 57%, P = 0.07).

Figure 12.

Forest plot analysis of the Daily Nitrate Usage

Discussion

A total of 299 studies were obtained through systematic search based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and finally seventeen studies would effectively pertain to the desired consequences before and after treatment of patients with angina. Of these 17 studies, 16 are clinical trials with a total population of 582 patients, only one cohort study with a population of 450 patients. The mean age of patients was 27.1 years in the Gurovich study 15 and 76.8 years in the Braverman study. 16 All studies were published between 1999 and 2020. The evaluation of these studies quality, showed that, sixteen studies out of 17 studies submitted were of high quality and only one article was of low quality.

In this study, thirteen outcomes were analyzed and the results of meta-analysis in twelve outcomes indicate a significant clinical advantage in terms of the usefulness of EECP treatment in patients with angina. The effects of Aortic and Barchial SBP and Aortic and Barchial DBP in seven studies and the consequences of Aortic and Barchial PP and MAP in four studies were significantly reduced after treatment with EECP (P < 0.00001). The outcomes of Heart Rate, walking distance, and Exercise Treadmill Test-Time which significantly increased after treatment with EECP were reported in six, two and three studies, respectively (P < 0.00001). The outcome of angina episodes which was evaluated in four studies on daily basis and three studies weekly and also the outcome of CCS angina which was evaluated from a meta-analysis of six studies and the outcome of daily nitrate consumption which was evaluated from a meta-analysis of four studies revealed significantly reduced outcomes after treatment with EECP (P < 0.00001). The outcome of brachial and femoral FMD, which was examined in three studies, was significantly increased after treatment with EECP (P < 0.00001).No significant difference was observed in terms of usefulness in treatment with EECP (P = 0.18) only in the outcome of brachial artery diameter, which was the result of meta-analysis of two studies. The effect size index was the mean difference in all outcomes, except one outcome (t-segment depression) which used relative risk, whose results also indicate a significant outcome in favor of EECP treatment.

The outcomes meta-analysis results showed that, the I2 statistic, which is the criterion for the presence of heterogeneity, was calculated below 25% except for the outcomes of walking distance and femoral flow-mediated dilation, which indicates the absence of significant heterogeneity. This in turn, increases the reliability and general and definite conclusions about the effectiveness and safety of this treatment and its generalizability.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Zhang et al 32 in 2015, only were the implications of the CCS Angina Class examined. The present study in which thirteen outcomes have been evaluated and meta-analyzed is comprehensive and up-to-date. Amin et al 33 systematic review in 2010 examined the effectiveness of EECP in young 18-year-olds, in which only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) article which compared EECP with sham was evaluated, whereas the present study is 10 years newer and more up-to-date than the study in question. In addition, studies that examined the EECP with the placebo group or other treatments such as medication were limited, hence in this study the effectiveness of EECP was evaluated before and after treatment. Of course, evaluating the effectiveness and safety of the EECP before and after treatment faces the bias, which reduces the validity and generalizability of the results thanks to the bias associated with the study design of such RCTs. Another systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to assess whether EECP affects myocardial perfusion in CAD patients. It has been shown that standard EECP treatment significantly increases myocardial perfusion in CAD patients. 5

One of the limitations of this study was the short follow-up time of the results in the studies submitted for analysis. To the best of our knowledge and based on the studies submitted, there was no evidence of examining the outcomes of long-term follow-up periods (more than one year), and there is a large study gap in this regard, accordingly. It seems that we need to conduct studies with a follow-up time of more than one year in order to make a more realistic decision and judgment about the therapeutic role of EECP. Other limitations of this study are the small sample size of each study and the consequent low sample size of the meta-analyzed consequences. Also, articles whose statistical data were not fully reported were not included in the study. Therefore, two articles were not included in the study because their statistical data were not fully reported and we did not have access to their statistical data. 34,35 We tried to contact the author of these studies, but unfortunately, we were not able to receive any related data, and the incompleteness of the statistical data may affect the results.

Conclusion

Although, the results significantly indicate the safety and effectiveness of EECP in patients with angina pectoris and indicate the usefulness of this treatment in these patients based on the meta-analyzes; in general, the authors believe that, the general conclusion in this case requires high quality studies along with larger sample size and a control group due to the afro-mentioned limitations and the existence of evidence with low sample size as well as the examination of the outcomes before and after the treatment, though.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals who have contributed at various stages through the development of this project

Competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the local ethical committee (code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1398.829) and the Helsinki Declaration was respected across the study.

Funding/Support

The project has been supported by of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences

References

- 1.Mazloomi Mahmodabadi SS, Shahbazi H, Motlagh Z, Momeni Sarvestani M, Sadeghzadeh J. The study of knowledge, attitude and practice of Yazd restaurant chefs in preventing cardiovascular diseases risk factors in 2010. Toloo-e-Behdasht. 2011;10(1):14–27. Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). World Health Organization (WHO); 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds). Accessed April 14, 2021.

- 3.Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1859–1922. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32335-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGillion M, Arthur H, Andréll P, Watt-Watson J. Self management training in refractory angina. BMJ. 2008;336(7640):338–339. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39465.522569.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin X, Deng Y, Wu D, Yu L, Huang R. Does enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) significantly affect myocardial perfusion?: a systematic review & meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0151822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin S, Xiao-Ming W, Gui-Fu W. Expert consensus on the clinical application of enhanced external counterpulsation in elderly people (2019) Aging Med (Milton) 2020;3(1):16–24. doi: 10.1002/agm2.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loh PH, Cleland JG, Louis AA, Kennard ED, Cook JF, Caplin JL. et al. Enhanced external counterpulsation in the treatment of chronic refractory angina: a long-term follow-up outcome from the International Enhanced External Counterpulsation Patient Registry. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31(4):159–164. doi: 10.1002/clc.20117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esmaeilzadeh M, Khaledifar A, Maleki M, Sadeghpour A, Samiei N, Moladoust H. et al. Evaluation of left ventricular systolic and diastolic regional function after enhanced external counter pulsation therapy using strain rate imaging. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10(1):120–126. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pettersson T, Bondesson S, Cojocaru D, Ohlsson O, Wackenfors A, Edvinsson L. One year follow-up of patients with refractory angina pectoris treated with enhanced external counterpulsation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson WE, Hui JC, Cohn PF. Long-term prognosis of patients with angina treated with enhanced external counterpulsation: five-year follow-up study. Clin Cardiol. 2000;23(4):254–258. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960230406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raza A, Steinberg K, Tartaglia J, Frishman WH, Gupta T. Enhanced external counterpulsation therapy: past, present, and future. Cardiol Rev. 2017;25(2):59–67. doi: 10.1097/crd.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurovich AN, Braith RW. Enhanced external counterpulsation creates acute blood flow patterns responsible for improved flow-mediated dilation in humans. Hypertens Res. 2013;36(4):297–305. doi: 10.1038/hr.2012.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braverman DL, Braitman L, Figueredo VM. The safety and efficacy of enhanced external counterpulsation as a treatment for angina in patients with aortic stenosis. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(2):82–87. doi: 10.1002/clc.22073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arora RR, Chou TM, Jain D, Fleishman B, Crawford L, McKiernan T. et al. The multicenter study of enhanced external counterpulsation (MUST-EECP): effect of EECP on exercise-induced myocardial ischemia and anginal episodes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(7):1833–1840. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck DT, Martin JS, Casey DP, Avery JC, Sardina PD, Braith RW. Enhanced external counterpulsation improves endothelial function and exercise capacity in patients with ischaemic left ventricular dysfunction. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2014;41(9):628–636. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck DT, Casey DP, Martin JS, Sardina PD, Braith RW. Enhanced external counterpulsation reduces indices of central blood pressure and myocardial oxygen demand in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2015;42(4):315–320. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bondesson S, Pettersson T, Ohlsson O, Hallberg IR, Wackenfors A, Edvinsson L. Effects on blood pressure in patients with refractory angina pectoris after enhanced external counterpulsation. Blood Press. 2010;19(5):287–294. doi: 10.3109/08037051003794375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braith RW, Conti CR, Nichols WW, Choi CY, Khuddus MA, Beck DT. et al. Enhanced external counterpulsation improves peripheral artery flow-mediated dilation in patients with chronic angina: a randomized sham-controlled study. Circulation. 2010;122(16):1612–1620. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.109.923482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casey DP, Conti CR, Nichols WW, Choi CY, Khuddus MA, Braith RW. Effect of enhanced external counterpulsation on inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in patients with angina pectoris and angiographic coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(3):300–302. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casey DP, Beck DT, Nichols WW, Conti CR, Choi CY, Khuddus MA. et al. Effects of enhanced external counterpulsation on arterial stiffness and myocardial oxygen demand in patients with chronic angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(10):1466–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dockery F, Rajkumar C, Bulpitt CJ, Hall RJ, Bagger JP. Enhanced external counterpulsation does not alter arterial stiffness in patients with angina. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27(12):689–692. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960271206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hashemi M, Hoseinbalam M, Khazaei M. Long-term effect of enhanced external counterpulsation on endothelial function in the patients with intractable angina. Heart Lung Circ. 2008;17(5):383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Aronow WS, Vadnerkar A, Sidhu P, Mittal S, Kasliwal RR. et al. Effect of enhanced external counterpulsation on clinical symptoms, quality of life, 6-minute walking distance, and echocardiographic measurements of left ventricular systolic and diastolic function after 35 days of treatment and at 1-year follow up in 47 patients with chronic refractory angina pectoris. Am J Ther. 2009;16(2):116–118. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31814db0ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaels AD, Bart BA, Pinto T, Lafferty J, Fung G, Kennard ED. The effects of enhanced external counterpulsation on time- and frequency-domain measures of heart rate variability. J Electrocardiol. 2007;40(6):515–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichols WW, Estrada JC, Braith RW, Owens K, Conti CR. Enhanced external counterpulsation treatment improves arterial wall properties and wave reflection characteristics in patients with refractory angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(6):1208–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soran O, Kennard ED, Bart BA, Kelsey SF. Impact of external counterpulsation treatment on emergency department visits and hospitalizations in refractory angina patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Congest Heart Fail. 2007;13(1):36–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2007.05989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tartaglia J, Stenerson J Jr, Charney R, Ramasamy S, Fleishman BL, Gerardi P. et al. Exercise capability and myocardial perfusion in chronic angina patients treated with enhanced external counterpulsation. Clin Cardiol. 2003;26(6):287–290. doi: 10.1002/clc.4950260610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu E, Desta L, Broström A, Mårtensson J. Effectiveness of enhanced external counterpulsation treatment on symptom burden, medication profile, physical capacity, cardiac anxiety, and health-related quality of life in patients with refractory angina pectoris. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;35(4):375–385. doi: 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C, Liu X, Wang X, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Ge Z. Efficacy of enhanced external counterpulsation in patients with chronic refractory angina on Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) angina class: an updated meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(47):e2002. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000002002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amin F, Al Hajeri A, Civelek B, Fedorowicz Z, Manzer BM. Enhanced external counterpulsation for chronic angina pectoris. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010(2):CD007219. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007219.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stys T, Lawson WE, Hui JC, Lang G, Liuzzo J, Cohn PF. Acute hemodynamic effects and angina improvement with enhanced external counterpulsation. Angiology. 2001;52(10):653–658. doi: 10.1177/000331970105201001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bondesson S, Pettersson T, Erdling A, Hallberg IR, Wackenfors A, Edvinsson L. Comparison of patients undergoing enhanced external counterpulsation and spinal cord stimulation for refractory angina pectoris. Coron Artery Dis. 2008;19(8):627–634. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e3283162489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]