Abstract

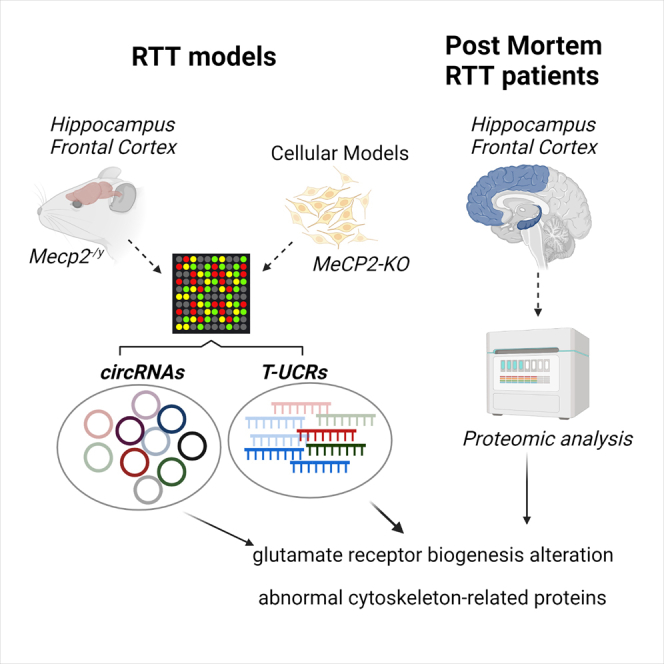

Noncoding RNAs play regulatory roles in physiopathology, but their involvement in neurodevelopmental diseases is poorly understood. Rett syndrome is a severe, progressive neurodevelopmental disorder linked to loss-of-function mutations of the MeCP2 gene for which no cure is yet available. Analysis of the noncoding RNA profile corresponding to the brain-abundant circular RNA (circRNA) and transcribed-ultraconserved region (T-UCR) populations in a mouse model of the disease reveals widespread dysregulation and enrichment in glutamatergic excitatory signaling and microtubule cytoskeleton pathways of the corresponding host genes. Proteomic analysis of hippocampal samples from affected individuals confirms abnormal levels of several cytoskeleton-related proteins together with key alterations in neurotransmission. Importantly, the glutamate receptor GRIA3 gene displays altered biogenesis in affected individuals and in vitro human cells and is influenced by expression of two ultraconserved RNAs. We also describe post-transcriptional regulation of SIRT2 by circRNAs, which modulates acetylation and total protein levels of GluR-1. As a consequence, both regulatory mechanisms converge on the biogenesis of AMPA receptors, with an effect on neuronal differentiation. In both cases, the noncoding RNAs antagonize MeCP2-directed regulation. Our findings indicate that noncoding transcripts may contribute to key alterations in Rett syndrome and are not only useful tools for revealing dysregulated processes but also molecules of biomarker value.

Keywords: MeCP2, Rett syndrome, circRNA, T-UCR, noncoding RNA, AMPA receptor, SIRT2, microtubules, GRIA3

Graphical abstract

circRNAs and T-UCRs identify convergent pathways in mouse and human models of Rett syndrome. GRIA3 biogenesis is altered in affected individuals and human cells influenced by two ultraconserved RNAs. SIRT2 is post-transcriptionally regulated by circRNAs. Noncoding RNAs antagonize MeCP2-directed regulation, highlighting the potential of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) as biomarkers in Rett syndrome.

Introduction

Most of the human genome is transcribed as noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs),1 some of which have crucial roles in control of gene regulation, especially in the brain and in neurological diseases.2 Compared with other tissues, the brain displays a higher diversity of expressed ncRNAs and is the organ with the most tissue-specific long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), with regulated temporal and spatial expression patterns.3,4 lncRNAs are thought to play crucial roles in brain maturation and function, and, as a consequence, their dysregulation is likely to be important during onset or progression of a number of neurological diseases.5,6 Although most ncRNAs are linear molecules, a subgroup of them form a circle through covalent binding; circular RNAs (circRNAs) are expressed in a tissue- and organ-specific manner and derive mainly from non-canonical splicing of protein-coding pre-mRNAs.7 Their functions remain largely unexplored, although one proposed mode of action is based on their ability to titrate out the pool of functional microRNAs (miRNAs) (and also RNA-binding proteins or other small RNAs) by acting as molecular “sponges.”8, 9, 10, 11 In the brain, circRNAs are highly abundant in synapses and more conserved than other ncRNAs, and their expression seems to increase during development of the CNS.12 In addition, their presence in the bloodstream and their abundance in exosomes as circulating molecules may make them valuable biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis in a variety of human diseases, including disorders of the CNS and degenerative diseases.13

Rett syndrome (RTT; MIM: 312750) is a postnatal progressive neurodevelopmental pathology that affects 1 in ∼10,000 female births14,15 and in which loss of function mutations in the X chromosome-linked MeCP2 gene are the genetic basis of most cases.16 MeCP2 is a nuclear protein, expressed widely in a range of tissues, that is most abundant in neurons of the mature nervous system. It was first identified by Lewis et al.17 as a new protein that binds to methylated CpG dinucleotides. RTT is a progressive disorder with a normal prenatal and perinatal period and proper brain development during the first few months of life, associated with normal child neurodevelopment, motor function, and communication skills. However, developmental regression appears between 8 and 24 months of age.18 Thereafter, the disorder may become evident when affected individuals lose their verbal ability and show severe cognitive impairment, stereotypic behaviors, as well as cardiac and respiratory abnormalities.19,20 RTT is considered a synaptopathy, displaying aberrant expression of neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, transporters, and receptors, which are the basis of unbalanced excitatory/inhibitory neurotransmission.21 The lack of an effective cure or even of treatment options to ameliorate the most disabling symptoms of the disorder highlights the need for a better understanding of its physiopathology.22, 23, 24 Current efforts to tackle RTT include pharmacological and molecular genetics-based strategies, but the therapeutic approaches developed so far have had limited success (see Leonard et al.24 for a review).

Implementation of several mouse models that mimic the disease has been crucial to progress in research on RTT. For example, Mecp2 knockout (KO) mice have a range of physiological and neurological abnormalities that imitate the human syndrome. KO mice are normal overall until 4 weeks of age, after which they begin to suffer cognitive and motor dysfunction until they fully manifest the RTT-like phenotype at around 6–8 weeks of age. This leads to rapid weight loss and death at approximately 10 weeks of age.25 This and other models have been used to identify the molecular mechanisms and pathways with key roles in RTT etiology and have provided an essential platform for drug testing in pre-clinical assays. Nevertheless, the lack of effective therapies and biomarkers available warrants further examination of the cellular programs underlying the disorder.

One insufficiently understood aspect of RTT is the potential role of noncoding transcripts whose levels are impaired in the context of MeCP2 mutations. Although efforts have been made to characterize the RTT miRNome,26,27 and specific miRNAs have been investigated in the context of RTT,28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35 other classes of ncRNAs, including long species, have remained largely unexplored. In this study, we describe alterations in two types of ncRNA that are especially enriched in the brain: circRNA and transcribed-ultraconserved region (T-UCR) transcripts. Host genes for both classes of altered ncRNAs are particularly highly enriched in key processes in RTT (namely, neurotransmission and cytoskeleton dynamics), demonstrating the potential of ncRNAs to reveal crucial abnormalities in neurodevelopmental disorders.

Results

circRNAs are dysregulated in Mecp2 KO mouse models

circRNAs are important for many neurodevelopmental processes, including neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity.36,37 To identify circRNA molecules with altered expression in RTT, we used a circRNA microarray to accurately quantify their expression profiles in the hippocampus and frontal cortex of symptomatic, 8-week-old Mecp2 KO mice and compared their levels with those of wild-type littermates of the same age. circRNAs with a fold change of1.5 or greater and values of p ≤ 0.05 were selected as significantly differentially expressed (DE) transcripts (Figures 1A and S1A). There were fewer DE circRNAs in the mouse frontal cortex (FC) than in the hippocampus (HIP) (47 upregulated and 103 downregulated versus 141 upregulated and 247 downregulated, respectively). In accordance with the previously described upregulation of circRNAs during neuronal differentiation and maturation12 and the fact that individuals with RTT have reduced dendritic complexity and spine density,38 we found more downregulated circRNA species in the HIP of Mecp2 KO mice (Figure S1A). circRNAs most commonly derive from non-canonical splicing of the pre-mRNA of host protein-coding genes, and although in several examples there was little correlation between the variation in the abundance of a circRNA and its cognate linear RNA,39 one major factor that controls the expression of a particular circRNA is transcription of its host gene. Therefore, valuable insights can be gained from analyzing the gene ontologies of host genes. Enrichment analysis shows that DE circRNAs with a fold change of 2 or greater and p ≤ 0.05 derive from host genes belonging to categories related to synaptic transmission, specifically AMPA-type ionotropic glutamatergic receptors (Figures 1B, 1C, and S1B). These and other genes of special importance in brain development were selected for further validation (see below).

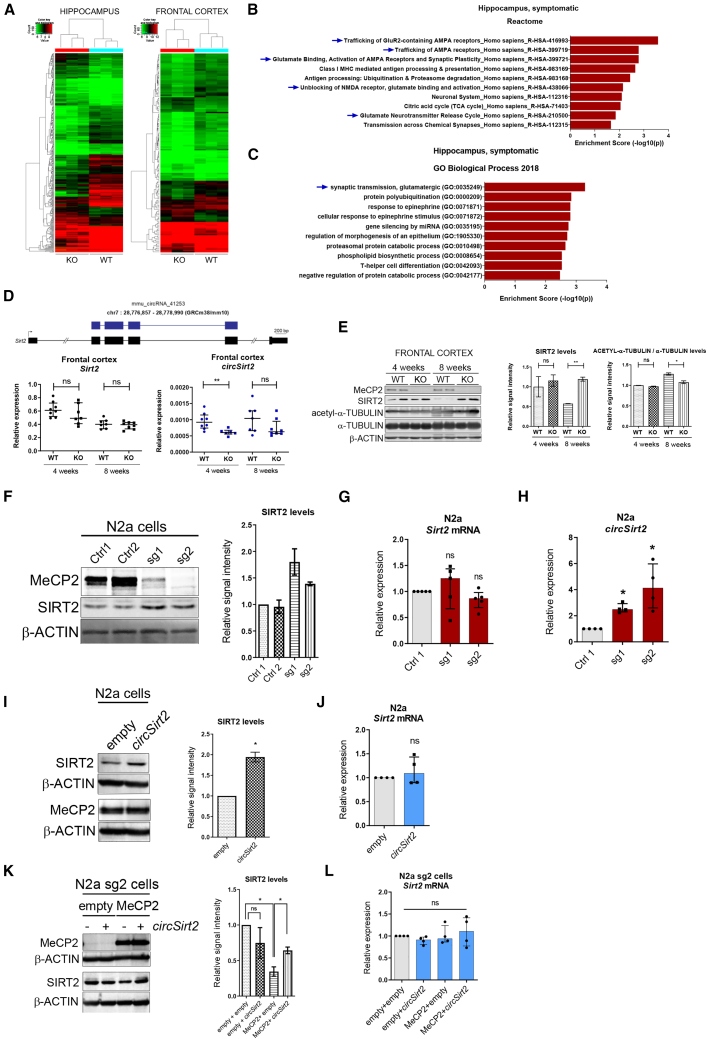

Figure 1.

Analysis of the altered circRNA population in MeCP2-deficient mice and cell lines

(A) Heatmap and hierarchical clustering analysis of circular RNAs (circRNAs) that are DE in the HIP and FC of 8-week-old Mecp2 KO and WT mice (two-tailed unpaired t test, fold change > 1.5, p < 0.05). (B and C) Enriched Gene Ontology terms for the host genes of altered circRNA (fold change > 2), as identified by functional clustering (Enrichr). The y axis shows the Gene Ontology (GO) terms, and the x axis shows the statistical significance (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). Categories corresponding to glutamatergic trafficking and/or signaling are highlighted. (D) Top panel: intronic/exonic organization of linear (black) and circular (blue) transcripts in the Sirt2 locus. Coordinates correspond to those of the UCSC Genome Browser (GRCh38/mm10 release). Only the potentially circularized exons and 5ʹ and -3′ regions of the Sirt2 transcripts are included. Bottom panel: the expression levels of Sirt2 (left) and circSirt2 (right) were analyzed by qRT-PCR in FC from WT and KO pre-symptomatic (4-week-old) and symptomatic (8-week-old) mice. Graphs show the median and interquartile range of 6–8 replicates from different animals per condition. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests were used (∗∗p < 0.01; ns, not significant). (E) Western blot analysis of MeCP2, SIRT2, acetyl-α-tubulin, and α-tubulin in FC from WT and KO pre-symptomatic and symptomatic mice. Samples from two animals per condition are shown. Graphs on the right represent quantitation of band intensity (unpaired t test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). (F) Western blot analysis of MeCP2 and SIRT2 in N2a cells (2 controls and 2 Mecp2-KO clones). Two sgRNA sequences targeting the Mecp2 gene were used (sg1 and sg2). The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of two representative experiments. (G and H) Expression levels of Sirt2 mRNA and circSirt2 were analyzed by qRT-PCR in the same samples as in (F). Graphs show the median and interquartile range (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, ∗p < 0.05). (I) Western blot analysis of SIRT2, β-actin, and MeCP2 in N2a cells overexpressed with an empty or circSirt2 plasmid. The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of two representative experiments (two-tailed unpaired t test, ∗p < 0.05). (J) Expression levels of Sirt2 mRNA were analyzed by qRT-PCR in the same samples as in (I). The graph shows the median and interquartile range (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). (K) Western blot analysis of MeCP2 and SIRT2 in N2a KO cells (sg2 clone) upon overexpression of circSirt2 and/or MeCP2, as indicated. The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of two representative experiments (two-tailed unpaired t test, ∗p < 0.05). (L) Expression levels of Sirt2 mRNA were analyzed by qRT-PCR in the same samples as in (K). The graph shows the median and interquartile range (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). See also Figure S1.

SIRT2 and related circRNAs are altered in mouse and human models of RTT

The microtubule cytoskeleton plays an essential role in neuronal function, migration, and differentiation and influences trafficking to dendritic spines of AMPA-type receptors.40 Importantly, the acetylation state of microtubules regulates molecular motor trafficking of mRNA and of vesicles containing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is one of the major downstream targets of MeCP2 in RTT pathogenesis.41 In addition, a reduction in acetylated α-tubulin has been reported in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons and mouse models of the syndrome.42,43 The HDAC6 and SIRT2 lysine deacetylases are thought to play a role in α-tubulin deacetylation, and their deregulation is considered to be important in certain neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases.44,45 In particular, we detected a decrease in circSirt2 in the FC of pre-symptomatic mice, which was not accompanied by changes in host gene mRNA levels (Figure 1D). Because some circRNAs modulate translation of their linear counterparts, we assayed the levels of SIRT2 protein by western blot and detected a marked increase in the FC (but not the HIP) of 8-week-old symptomatic mice and a reduction in acetylation of the SIRT2 main target, α-tubulin (Figures 1E and S1C), which confirms previous observations of reduced levels of acetylated α-tubulin in MeCP2-depleted cells.43

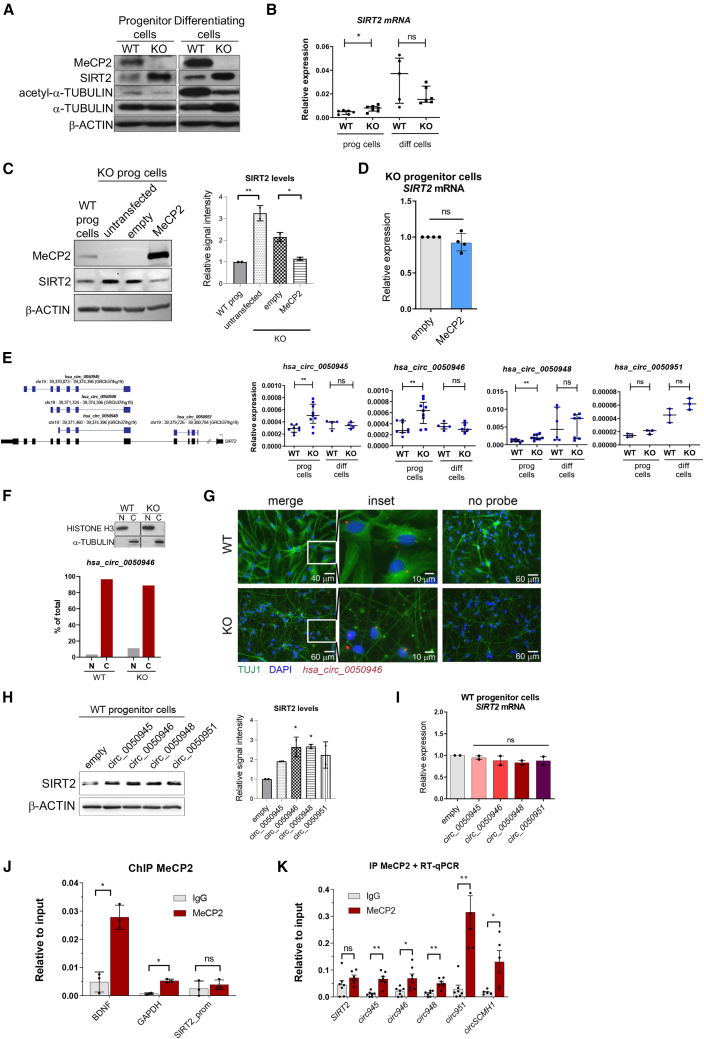

To confirm these observations, we used two cellular models, the mouse neuroblastoma N2a cell line and the human neural progenitor cell line ReNCell VM, which were engineered to suppress MeCP2 expression through genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9. On one hand, and in accordance with the data from mice, decreased levels of MeCP2 protein in N2a cells correlated with an increase in SIRT2 protein levels (Figure 1F), whereas Sirt2 linear transcript levels remained unaltered (Figure 1G). Notably, circSIRT2 expression was upregulated under these conditions (Figure 1H). Further, overexpression of circSIRT2 in wild-type N2a cells produced a 2-fold increase in SIRT2 protein levels without altering Sirt2 mRNA (Figures 1I and 1J). Finally, circSIRT2 counteracts the effect of MeCP2 overexpression in N2a KO cells, restoring the levels of SIRT2 protein, again without any change in Sirt2 mRNA levels (Figures 1K and 1L). On the other hand, we observed a similar regulation taking place in human neural progenitor cells. As shown in Figures 2A and 2B, levels of SIRT2 protein (but not of its mRNA) were much higher in MeCP2-KO cells, especially in spontaneously differentiating cells, concomitant with a decrease in the levels of acetylated α-tubulin. Overexpression of MeCP2 in MeCP2 KO cells downregulated SIRT2 protein (Figure 2C) but not its mRNA (Figure 2D), again pointing to post-transcriptional regulation. To ascertain the potential role of circRNAs therein, we investigated the expression of human circSIRT2 in our neural progenitor cells. There are several annotated circRNA molecules from the SIRT2 locus, including hsa_circ_0050951, which is highly similar to mouse circSIRT2. We were able to detect four of these species, three of which were upregulated in MeCP2 KO progenitor cells (Figure 2E). Cellular fractionation and RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) experiments indicated that these circRNAs accumulated in the cytoplasm (Figures 2F and S2A) and were enriched in the cellular soma (Figures 2G and S2B), and only hsa_circ_0050951 was quantitatively present in the nucleus (Figure S2A). To test their functional relevance, we overexpressed them in wild-type (WT) progenitor cells and observed that all of them caused an increase in SIRT2 protein levels (Figure 2H) without affecting SIRT2 mRNA (Figure 2I). Of note, this increase was attenuated when we combined overexpression of the circRNAs with overexpression of MeCP2 in MeCP2 KO neural progenitor cells (Figures S2C and S2D). We finally wanted to determine how MeCP2 could influence circSIRT2 production. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) data do not indicate an enrichment of MeCP2 on the promoter of the SIRT2 gene and on circularized exons (Figure 2J); in contrast, we could quantitatively retrieve all circSIRT2 species (but not linear SIRT2 mRNA) in MeCP2 immunoprecipitation assays (Figure 2K). This is reminiscent of the recently described binding of MeCP2 to circSCMH1 in ischemic stroke models.46 Of note, circ_0050951, the most nuclear of all circSIRT2 molecules (Figure S2A), displayed the highest enrichment in MeCP2 immunoprecipitations(Figure 2K), suggesting that nuclear retention might be directed by its binding to MeCP2. Use of the catRAPID algorithm confirmed the high capacity of the NID and C-t domains within MeCP2 to interact with all circSIRT2 RNAs (Figure S2E), coinciding with previous observations of MeCP2 RNA binding ability (recently reviewed by Good et al.47). These results indicate that linear and circular SIRT2 molecules are subject to differential regulation by MeCP2 and point to a post-transcriptional regulatory role of circSIRT2 that might affect SIRT2 protein levels and, potentially, microtubule cytoskeleton dynamics.

Figure 2.

Analysis of SIRT2 and circSIRT2 expression in human neural progenitor and differentiating cells

(A) Western blot analysis of MeCP2, SIRT2, acetyl-α-tubulin, and α-tubulin in WT or MeCP2 KO neural progenitors and differentiating cells (30 days). (B) Expression levels of SIRT2 mRNA in the same samples as in (A) were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Graphs show the median and interquartile range (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, ∗p < 0.05). (C) Western blot analysis of MeCP2 and SIRT2 in MeCP2 KO neural progenitor cells upon ectopic expression of MeCP2. WT cells are also shown for comparison. The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of two representative experiments (one-way ANOVA was used; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). (D) Expression levels of SIRT2 mRNA were analyzed by qRT-PCR in MeCP2 KO control or MeCP2-overexpressing progenitor cells. The graph shows the median and interquartile range (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). (E) Left: intronic/exonic organization of linear (black) and circular (blue) transcripts in the human SIRT2 locus. Coordinates correspond to those of the UCSC Genome Browser (GRCh37/hg19 release). Only the detected circRNAs and 5ʹ and -3′ regions of SIRT2 transcripts are included. Right: expression levels of the described circRNAs in WT or MeCP2 KO progenitor or differentiating cells (30 days) were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Graphs represent the median with interquartile range (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, ∗∗p < 0.01). (F) Nuclear/cytoplasmic fractionation of WT or MeCP2 KO differentiating neural progenitor cells (day 14), analyzed by qRT-PCR and western blot to assess fraction purity. (G) RNA ISH showing localization of human hsa_circ_0050946 (derived from the SIRT2 gene) in WT or MeCP2 KO differentiating neural progenitor cells (14 days). Colocalization with the neuronal marker TUJ1 is shown. Scale bar size is indicated in each panel. (H) Western blot analysis of SIRT2 in WT neural progenitor cells upon overexpression of the circular transcripts from the human SIRT2 locus. The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of two representative experiments (one-way ANOVA was used; ∗p < 0.05). (I) Expression levels of SIRT2 mRNA were analyzed by qRT-PCR in the same samples as in (H). One-way ANOVA was used. (J) Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled to qPCR to determine MeCP2 binding to the SIRT2 promoter in WT progenitor cells. The graph represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. The enrichments corresponding to BDNF and GAPDH promoters are shown for comparison. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used (∗p < 0.05). (K) qRT-PCR analysis of retrieved RNA following MeCP2 IP in WT progenitor cells. SIRT2 locus-derived transcripts were analyzed. circSCMH1 was used as a positive control. The graph represents the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test was used (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). See also Figure S2.

circSIRT2 modulates GluR-1 levels through regulation of SIRT2

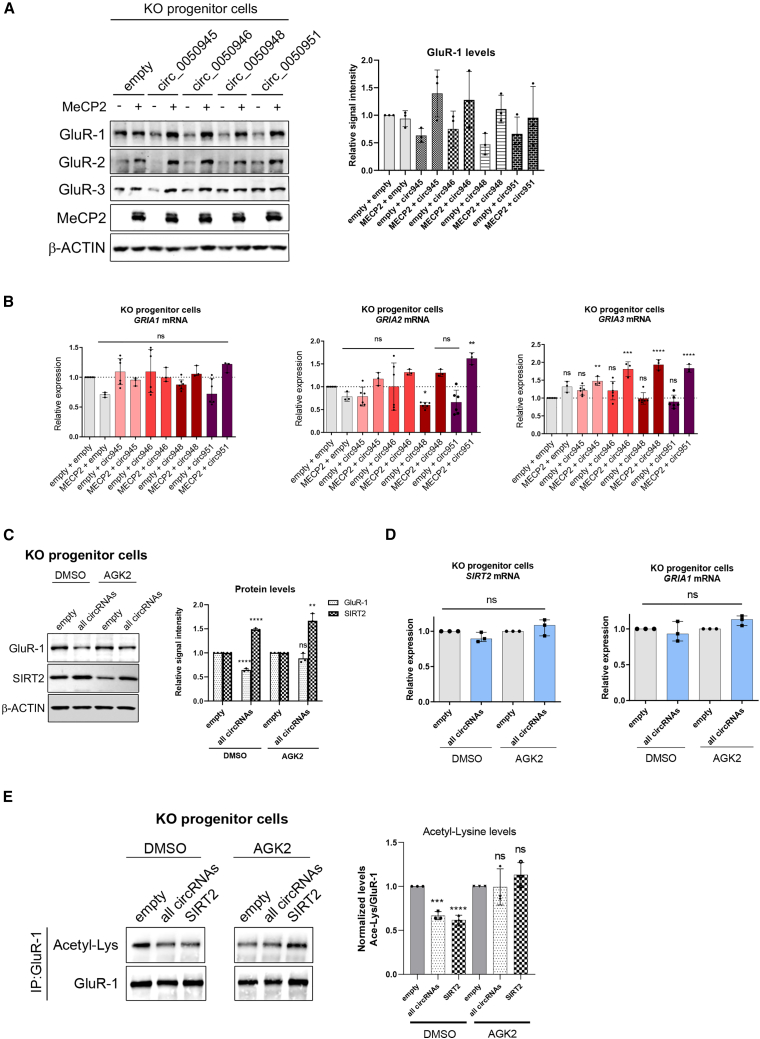

Another potentially relevant target of SIRT2 in the context of RTT is GluR-1, a subunit of AMPAR complexes. Glutamate receptors have a key role in excitatory synaptic transmission in the CNS, and alterations in MeCP2 levels in glutamatergic neurons contribute to the RTT phenotype,48 possibly to varying degrees, depending on the brain region. We have previously observed smaller miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents in cultured neurons from Mecp2 KO mouse cerebellum.49 In hippocampal glutamatergic synapses, most postsynaptic receptors are heterotetramers that contain GluR-1/GluR-2 and GluR-2/GluR-3 subunits (encoded by the genes GRIA1–GRIA3). SIRT2 has been reported to promote deacetylation of GluR-1, downregulating protein levels and impairing AMPAR trafficking and synaptic plasticity.50,51 Given the effect of circSIRT2 on the levels of SIRT2 protein, we next investigated whether changes in circSIRT2 levels could alter the expression of AMPA receptor subunits. As shown in Figures S2F and S2G, overexpression of individual circSIRT2 RNAs in WT neural progenitor cells had little effect on GluR-1/2/3 mRNA or protein levels. However, their enforced expression in MeCP2 KO cells resulted in a marked decrease in GluR-1 and -2 protein levels and, to a minor extent, also in GluR-3 levels, and this could be reversed by overexpression of MeCP2 (Figure 3A), indicating that varying levels of circRNAs in the background of MeCP2 deficiency may contribute greatly to AMPAR biogenesis. This effect on protein levels was not mirrored by major changes in GRIA1–GRIA3 mRNA levels (Figure 3B), pointing to post-transcriptional regulation. To assess circRNA roles in the reported control of GluR-1 acetylation by SIRT2, we next co-transfected all circSIRT2 RNAs together and observed a decrease in GluR-1 protein levels (but not its mRNA levels) that was dependent on intact SIRT2 activity because use of the specific SIRT2 inhibitor AGK2 blocked the effect. Again, this was independent of changes in mRNA levels of either protein (Figures 3C and 3D). In view of this, we next immunoprecipitated GluR-1 and confirmed that its acetylation levels were downregulated upon overexpression of circSIRT2 RNAs to a degree similar to the effect of overexpressing SIRT2. This effect could be abolished using a SIRT2 inhibitor, suggesting that the circRNA molecules control GluR biogenesis by modulating SIRT2 levels (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Analysis of regulation by circRNAs from the SIRT2 locus on GluR-1–GluR-3 proteins

(A) Western blot analysis of GluR-1, -2, and -3 proteins in MeCP2 KO neural progenitor cells upon overexpression of the different circSIRT2 RNAs, individually or in combination with MeCP2 ectopic expression, as indicated. The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of three representative experiments (one-way ANOVA was used). (B) Expression levels of GRIA1, GRIA2, or GRIA3 mRNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR in the same samples as in (A). Graphs represent the median with interquartile range of at least 3 independent replicas (one-way ANOVA was used; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). (C) Western blot analysis of GluR-1 and SIRT2 proteins in KO progenitor cells upon overexpression of all four circSIRT2 RNAs (circ_0050945, circ_0050946, circ_0050948 and circ_0050951). Cells treated with the SIRT2 inhibitor AGK2 were compared with control cells (DMSO treated). The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity (mean ± SD) of three representative experiments (unpaired t test, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). (D) Expression levels of SIRT2 and GRIA1 mRNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR in the same samples as in (C). Graphs represent the median with interquartile range of at least 3 independent replicas (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). (E) GluR-1 IP from MeCP2 KO neural progenitor cells was analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against GluR-1 and acetyl-lysine. Cells were transfected with a control vector (empty) or the four circSIRT2 or SIRT2-HA plasmids and treated with the AGK2 inhibitor or mock treated (DMSO), as indicated. The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity (mean ± SD) of three representative experiments (one-way ANOVA, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Other circRNAs dysregulated in RTT are potentially associated with cytoskeleton and GluR proteins

Other circRNA species whose host genes play a role in cytoskeleton dynamics include circDnah2 and circMap1a, and it is worth noting that truncating variants of the latter have been associated with autism spectrum disorder.52 Most of Dnah2 and Map1a circular and linear species were downregulated in the FC of pre-symptomatic and symptomatic mice (Figures S1D and S1E). Another circRNA species of potential relevance to RTT is circFoxp1, which we found to be downregulated in the pre-symptomatic FC and upregulated in the symptomatic HIP (Figures S1F and S1G). The host gene, Foxp1, which encodes a transcription factor with an important role in brain development and whose loss causes autistic behavior and intellectual disability in mice,53 is dysregulated extensively in several different murine models of the disorder, as seen in recent meta-analyses of transcriptomic changes in RTT.54 Accordingly, we observed a significant decrease of the linear form in the symptomatic FC of Mecp2 KO animals (Figure S1F). Similarly, circBirc6, which was deregulated in the HIP and the FC (Figures S1H and S1I), originates from a candidate gene in autism spectrum disorders.55 In addition to the regulation by circSIRT2 shown above, an enrichment analysis indicates that many genes corresponding to subunits of AMPA receptors contain circRNA species that are altered in KO mice. In the FC, we did indeed observe a tendency (but not a statistically significant one) toward downregulation of the circGria4 RNA, similar to the linear form (Figure S1J). In the case of Gria2, the circular form appeared to be downregulated, in contrast to the linear form, but again the difference was not statistically significant (Figure S1K). It is clear that there is important dysregulation of the circRNA transcriptome that does not always coincide with changes in the corresponding host genes, highlighting their putative independent roles.

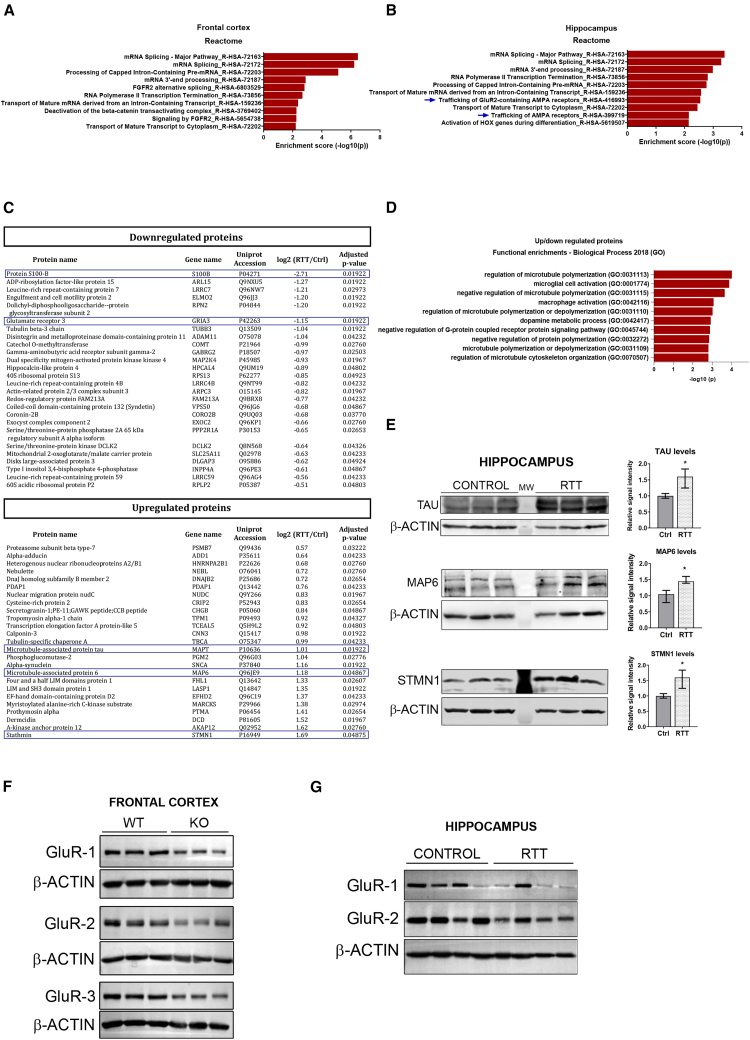

Transcripts derived from UCRs are altered in Mecp2 KO mice

The T-UCR transcriptome is another type of ncRNA that has never been analyzed previously in RTT models. T-UCRs are derived from genomic regions that are 100% conserved between humans, mice, and rats. Despite growing evidence of their potential as disease biomarkers,56, 57, 58 their extraordinary conservation and potential role in gene regulation are still insufficiently understood. In our mouse model of RTT, we found a number of T-UCRs that were altered in Mecp2 KO mice. Interestingly, although results from the FC reflected the expected enrichment in T-UCRs on host genes involved in mRNA biogenesis (Figure 4A),59 the results in the HIP again indicate an enrichment in categories related to AMPA receptor trafficking (Figure 4B; see below). Among the dysregulated T-UCRs, we confirmed the negatively correlated expression of the uc.309 transcript, which is antisense to an intron within Btrc. Btrc expression was downregulated in pre-symptomatic mice, whereas uc.309 was upregulated (Figure S3A). It is worth bearing in mind that Btrc is an E3 ubiquitin ligase required for correct neural differentiation through its ability to degrade REST, a master repressor of neuronal programs in non-neuronal lineages.60 The transcription factor Zeb2 also has an essential role in CNS development (reviewed by Epifanova et al.61). It was found to be altered in the HIP and FC of Mecp2 KO mice and contained several T-UCRs that had distinct patterns of expression (Figure S3B). Additionally, Hnrnph1, a splicing regulator with pathogenic variants associated with intellectual disability,62 was also dysregulated in the HIP and FC, displaying negatively correlated associations with uc.186 (Figure S3C). In all of these examples, expression of the T-UCRs and their respective host genes was not positively correlated, reflecting independent regulatory control and/or antagonistic expression and suggesting that T-UCR expression has a negative effect on the host genes.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the altered T-UCR population in Mecp2 KO mice and proteomics analysis of postmortem samples from individuals with RTT

(A and B) Enriched GO terms for the host genes of altered T-UCRs in the FC and HIP of Mecp2 KO mice (p < 0.05), as identified by functional clustering (reactome.org). The y axis shows GO terms, and the x axis shows statistical significance. (C) List of dysregulated proteins (adjusted p < 0.05) in the HIP of individuals with RTT. The ID of the corresponding gene and the expression change are indicated. Highlighted proteins were validated by western blot in this work. (D) Enriched GO terms for the altered proteins in the HIP of individuals with RTT, as identified by functional clustering (p < 0.05, Enrichr). The y axis shows GO terms, and the x axis shows the degree of statistical significance. (E) Western blot analysis of TAU, MAP6, and STMN1 in the HIP of brains from individuals with RTT. Samples from three control individuals and three individuals with RTT are shown. Graphs on the right represent quantitation of band intensity (unpaired t test, ∗p < 0.05). (F) Western blot analysis of GluR-1, -2, and -3 proteins in the FC of WT or Mecp2 KO symptomatic (8-week-old) mice. (G) Western blot analysis of GluR-1 and -2 in the HIP of brains from individuals with RTT. Samples from four control individuals and four individuals with RTT are shown. See also Figures S3 and S4.

The proteome from postmortem human HIP reveals changes in microtubule-cytoskeleton dynamics and AMPAR trafficking

To compare key pathway alterations in the mouse model with those found in individuals with RTT, we next analyzed the whole proteome of postmortem hippocampal regions from four control individuals and four individuals with RTT. Sequencing the MeCP2 gene detected alterations in all four clinically diagnosed individuals with RTT, whereas no mutations were found in the control samples. Mutations were not expected to produce truncated proteins, and western blot analysis revealed similar levels of protein (Figure S4A). Proteins significantly altered (false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.05) in individuals with RTT are listed in Figure 4C. An enrichment analysis revealed that categories related to microtubule dynamics were overrepresented and also pointed to alterations in microglia/macrophage activation (Figure 4D). Deficits in microtubule polymerization have been increasingly recognized in animal models of RTT63,64 as well as in MeCP2-deficient fibroblasts,65 and lower levels of expression of tubulin genes have been observed in the brain tissue of individuals with RTT.66 We confirmed the changes in several microtubule cytoskeleton-related proteins in the HIP from affected individuals, including upregulation of the microtubule-associated proteins TAU, MAP6, and STMN1, which might contribute to microtubule destabilization (Figure 4E). Unexpectedly, the most strongly downregulated protein in the proteome of HIP from affected individuals was the glial-specific protein S100B, an observation that is quite the opposite of the enrichment of glial cells seen in RTT models.67,68 However, early studies of RTT also detected a tendency toward downregulation of this astroglial protein in the cerebrospinal fluid of individuals with RTT,69 and more recent studies have reported no alterations in S100B expression in the hypothalamus of Mecp2 KO mice.70 This could reflect region-specific disruptions because we observed a decrease in S100B mRNA expression and protein levels in the HIP of Mecp2 KO mice (Figures S4B and S4C) but an increase in the FC of the same mice (Figure S4D). In addition, levels of S100B mRNA and protein in differentiating human neural progenitors were also higher in MeCP2 KO cells (Figures S4E and S4F). It is worth noting that S100B is very important for maturation of a variety of neurons in different CNS regions, including the HIP, as a consequence of its ability to promote and stabilize microtubule assembly.71,72 S100B is also important for glutamate clearance and has been shown to protect hippocampal neurons against toxic concentrations of glutamate.73 Given our findings linking circSIRT2 ncRNAs with AMPAR subunit regulation in cell models and the fact that our proteomics analysis showed that AMPA glutamate receptor 3 (GluR-3) was markedly downregulated in the HIP of individuals with RTT (Figure 4C), we next assessed GluR protein levels in mouse and human RTT samples. Indeed, GluR-1, -2, and -3 were downregulated in the FC of symptomatic MeCP2 KO mice (Figure 4F), and GluR-1 and -2 were also found to be decreased in the HIP of individuals with RTT (Figure 4G). As for GluR-3, we looked at its expression in more detail, taking into account that the gene hosts two ultraconserved transcripts.

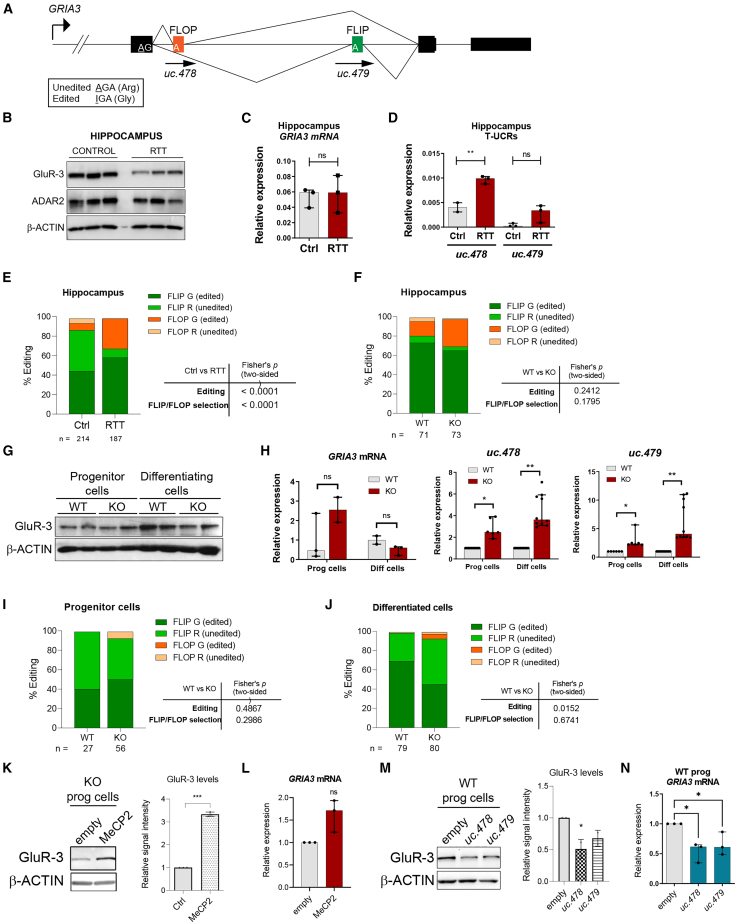

Changes in mRNA editing and protein levels of GluR-3 are correlated with T-UCR expression in human models of RTT

GRIA3 pre-mRNA undergoes alternative splicing to produce two splice variants containing one of the two mutually exclusive alternative exons (flip and flop variants), which confer distinct channel opening/closing kinetics to the receptor, with a suggested faster desensitization time for the flop variant.74, 75, 76 In addition, the diversity of GRIA3 transcripts is enhanced by adenosine-to-inosine editing of a position directly upstream of the alternative exons, which can result in an Arg-to-Gly change in the amino acid sequence of GluR-3 and additional fine-tuning of its receptor features. Importantly, flop and flip exons overlap with UCRs from where two transcripts are generated: uc.478 and uc.479 (Figure 5A). We first confirmed that GluR-3 protein levels were lower in the HIP of individuals with RTT (Figure 5B). This was not accompanied by a decrease in the total mRNA level, which was unaltered (Figure 5C) but, rather, by upregulation of expression of uc.478 and, to a lesser extent, of uc.479 (Figure 5D). This seems to be region specific because no noticeable changes in GRIA3 mRNA or protein levels or in T-UCR expression were found in the cerebellum or Brodmann area 10 of the same individuals (Figures S5A–S5F). We looked in detail at the frequency of editing and alternative exon selection in the HIP by performing RT-PCR of the 3′ end of GRIA3 transcripts and then cloning and sequencing the amplified products. Even though the flip exon was the one most frequently included in all samples, we noted a 3-fold difference in the ratio of flop exon inclusion (Figure 5E; from ∼10% in the control to ∼30% in RTT). In addition to this, we observed (1) a marked difference in editing levels (∼50% in control individuals compared with 90% in individuals with RTT) and (2) a significant non-random association of alternative exon selection and editing with RTT samples (Figure 5E). In comparison, the HIP of Mecp2 KO mice was highly edited, similar to WT animals (∼90%), and showed no significant differences in flip/flop selection or Gria3 and uc.478/uc.479 expression (Figures 5F and S5H–S5K), suggesting that these features are not present in this region of the Mecp2y/– animal model.

Figure 5.

Characterization of GRIA3 and T-UCR expression levels and editing in HIP from postmortem RTT samples, the mouse model, and human neural progenitor cells

(A) Schematic illustrating the GRIA3 locus encompassing the 3ʹ exons, including the alternatively spliced flip and flop exons and the A/I RNA editing site, where the arginine is recoded to a glycine. (B) Western blot analysis of GluR-3 and ADAR2 in the HIP of three postmortem samples from individuals with RTT and three samples from healthy control individuals. (C and D) Expression levels of GRIA3 mRNA and the T-UCRs uc.478 and uc.479 were analyzed in the same samples as in (B) by qRT-PCR. Graphs represent the median with interquartile range of the data from the three subjects per group (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, ∗∗p < 0.01). (E) Analysis of editing and alternative splicing choice of GRIA3 mRNA in the HIP from three postmortem samples of individuals with RTT and samples from three healthy control individuals. Percentages correspond to data pooled from sequences of at least 60 clones per subject. The contingency graph displays flip/flop selection and the associated edited/unedited status. Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used to measure the statistical significance of the editing and alternative splicing analyses. (F) Analysis of editing and alternative splicing choice of Gria3 mRNA in the HIP of control and Mecp2 KO mice. Percentages correspond to pooled data from sequences of at least two animals per condition. The contingency graph displays flip/flop selection and the associated edited/unedited status. Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used to estimate the statistical significance of the editing and alternative splicing analyses. (G) Western blot analysis of GluR-3 in WT and MeCP2 KO neural progenitor or freely differentiated cells (30 days). Two independent replicates were loaded per condition. (H) Expression levels of GRIA3 mRNA and the T-UCRs uc.478 and uc.479 were analyzed in the same samples as in (G) by qRT-PCR. Graphs represent the median with 95% confidence interval (CI) of the data (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U [GRIA3] or Wilcoxon tests [T-UCRs], ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). (I) Analysis of editing and alternative splicing choice of GRIA3 mRNA in WT or MeCP2 KO neural progenitor cells. Percentages correspond to pooled data from sequences of at least two replicates per condition. The contingency graph displays flip/flop selection and the associated edited/unedited status. Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) was used to estimate the statistical significance of the editing and alternative splicing analyses. (J) As in (I) but with cells freely differentiating for 30 days. (K) Western blot analysis of GluR-3 in KO progenitor cells (control or overexpressing MeCP2). The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of two representative experiments (a two-tailed t test was used; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (L) Expression levels of GRIA3 mRNA were analyzed in the same samples as in (K) by qRT-PCR. The graph represents the median with 95% CI of the data (two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test). (M) Western blot analysis of GluR-3 in WT neural progenitor cells upon overexpression of uc.478 or uc.479. The graph on the right represents quantitation of band intensity of two representative experiments (one-way ANOVA was used; ∗p < 0.05). (N) Expression levels of GRIA3 mRNA were analyzed in the same samples as in (M) by qRT-PCR. The graph represents the median with 95% CI of the data (one-way ANOVA was used; ∗p < 0.05). See also Figure S5.

Editing levels of GRIA receptor subunits were generally correlated with levels of the editing enzyme ADAR2.77 However, we did not detect any significant changes in ADAR2 protein levels in our RTT samples (Figure 5B), suggesting that other mechanisms determine the alterations in GRIA3 editing. To investigate this further, we explored the transcripts from the GRIA3 locus in human neural progenitor cells knocked out for MeCP2. When forced to differentiate (freely or toward glutamatergic neurons), levels of GluR-3 protein in KO cells also decreased (Figures 5G, S5L, and S5M) without any significant change in mRNA levels (Figure 5H). Importantly, levels of uc.478 and uc.479 increased in KO progenitor and differentiating cells (Figure 5H), which is concomitant with an increase (although not a statistically different one) in editing in progenitor cells from 40% to 50% and a decrease in differentiating cells from 70% to 50% (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.0152) (Figures 5I and 5J). Under the same conditions, flip/flop exon selection was not altered in MeCP2 KO cells (Figures 5I and 5J). To investigate the potential role of T-UCR expression in GRIA3 regulation in the context of RTT, we first carried out ChIP experiments and observed an enrichment of MeCP2 on the GRIA3 promoter (Figure S5N) but not direct binding of MeCP2 to GRIA3 mRNA or uc.478 or uc.479 RNAs (Figure S5O), pointing to direct transcriptional regulation of the loci by MeCP2. Regulation of GRIA3 by MeCP2 was further confirmed by overexpressing MeCP2 in KO cells, where both protein and mRNA levels were upregulated (Figures 5K and 5L). We next observed that uc.478 and uc.479 are nuclear poly(A) transcripts (Figures S5P and S5Q) and proceeded to overexpress them in WT progenitor cells (where they are present at low levels) from the pLVX-shRNA2 plasmid to generate transcripts with features that would mimic the endogenous T-UCRs. Overexpression of uc.478 and uc.479 resulted in downregulation of GRIA3 mRNA and protein levels (Figures 5M and 5N) but had little effect on editing levels and alternative exon selection (Figure S5R). This confirms the ability of ultraconserved transcripts to regulate gene expression and specifically shows the complex regulation of the GRIA3 locus.

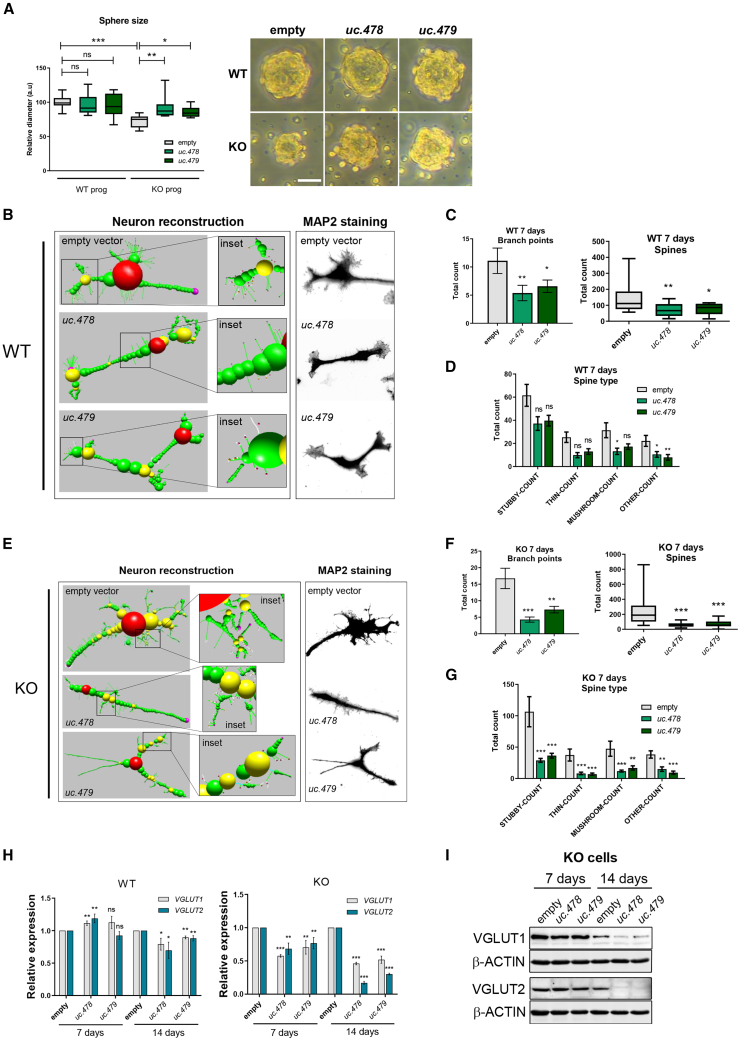

The ultraconserved uc.478 and uc.479 RNAs influence key aspects of RTT neural progenitor cell physiology

Given the observed influence on GluR-3 levels, we went on to investigate the potential effect of the ultraconserved uc.478 and uc.479 on more general features of RTT cellular models. Previous reports have described that neurosphere formation is defective in MeCP2 mutant cells,78 and we observed a decreased size of spheres in our MeCP2-KO neural progenitor cells (Figure 6A). Interestingly, overexpression of uc.478 or uc.479 on their own was able to restore sphere diameter in KO cells while not altering WT cells, suggesting that the levels of these ultraconserved ncRNAs play roles in refining the pluripotent or differentiating features in the MeCP2 mutant background. In addition, structural analysis of cells driven toward glutamatergic differentiation indicated that overexpression of uc.478 or uc.479 resulted in a marked decrease in neuronal complexity, as measured by the number of branchpoints and spines in WT (Figures 6B–6D) and KO cells (Figures 6E–6G). In accordance with this, as the time course of differentiation progressed, we detected downregulated levels of the glutamate transporters VGlut1 and VGlut2 (at the mRNA and protein levels; Figures 6H and 6I), which are associated with synaptic vesicles and represent canonical markers of glutamatergic neurons. This suggests a broad effect of ultraconserved transcripts on neural stem cell physiology in the context of RTT.

Figure 6.

Phenotypic analysis of neural progenitors and differentiating cells upon overexpression of uc.478 and uc.479

(A) The diameter of neurospheres was measured for WT or MeCP2 KO cells upon overexpression of uc.478 or uc.479. Graphs represent the median and interquartile range (a two-tailed t test was used; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Images correspond to representative spheres of each condition. Scale bar in the sphere, 100 μm. (B) Control WT neural progenitors or cells overexpressing uc.478 or uc.479, as indicated, were driven toward glutamatergic differentiation for 7 days, stained with MAP2, and reconstructed in silico from confocal images with NeuronStudio software. One representative picture for each condition is shown. (C) Automatic analysis of the cells in (B) allowed total branchpoints and spine count per condition (n = 20 neurons, one-way ANOVA was used; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). (D) For the same cells as in (B), the abundance of each spine subtype was determined with NeuronStudio software (n = 20 neurons, one-way ANOVA was used; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). (E–G) the same analysis as in (B)–(D) was performed in MeCP2 KO cells. (H) Expression levels of VGlut1 and VGlut2 mRNA were analyzed by qRT-PCR in WT or MeCP2 KO cells overexpressing uc.478 or uc.479 and driven toward glutamatergic differentiation for 7 or 14 days, as indicated. The graph represents the mean ± SD of three independent replicas (unpaired t test was used; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). (I) Western blot analysis of VGlut1 and VGlut2 protein levels from the same MeCP2 KO cells as in (H).

We detected MeCP2-dependent dysregulation of noncoding transcripts of the circRNA and T-UCR type that reveal complex regulation of transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms that converge toward alterations in trafficking and glutamate receptor biogenesis.

Discussion

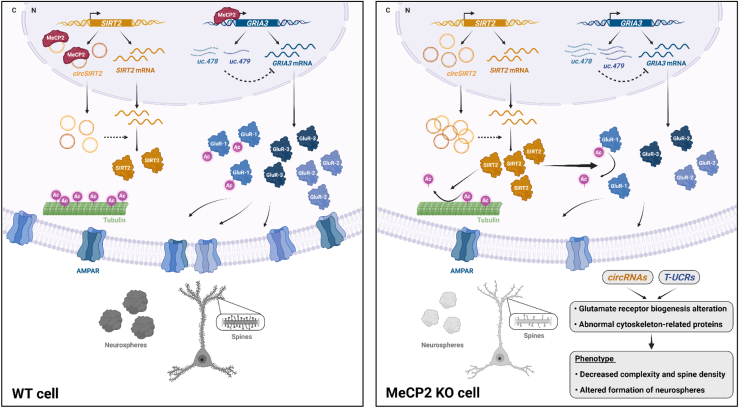

The alterations affecting ncRNA species in RTT are largely unknown. Several studies have addressed dysregulation of miRNAs acting downstream of MeCP2 or as direct regulators of MeCP2 expression, and it has been suggested that some of them are potential biomarkers or of potential therapeutic value.79,80 However, other types of ncRNAs have not been explored. Here we used four experimental models (the mouse Mecp2y/− [Bird] model, the mouse N2a neuroblastoma cell line knocked out for Mecp2, neural progenitor cells knocked out for MeCP2, and postmortem brain regions from affected individuals) to investigate two specific types of ncRNAs (circRNAs and T-UCRs) that are highly conserved in mouse and human. Alterations in these ncRNA populations have revealed dysregulated pathways that are common to the different contexts, specifically identifying two fundamental processes: the dynamics of the microtubule cytoskeleton and glutamatergic trafficking and signaling. It is remarkable that analysis of distinct types of ncRNAs have revealed converging altered pathways in RTT, and our molecular dissection provides a working model of regulation that integrates gene expression regulation by T-UCRs and circRNAs to ultimately modulate GluR subunit biogenesis, possibly in coordination with altered cytoskeleton trafficking (Figure 7). Arguably, the different experimental settings and the intrinsic nature of neurodevelopmental dynamics have resulted in some cases exhibiting an unexpected direction and/or magnitude of difference (e.g., those in uc.479 levels in postmortem HIP to those in differentiating neural progenitors; Figures 5D and 5H). However, the coincidence in the altered pathway as a whole (GRIA3 biogenesis) highlights the potential for ncRNAs to uncover hotspots of dysregulation as well as their potential involvement as targets or regulators.

Figure 7.

Schematic summarizing the findings in this work

Analysis of two types of ncRNAs in mouse and human models of RTT has revealed converging pathways. In WT cells, binding of MeCP2 to circSIRT2 species may prevent upregulation of SIRT2 and excessive deacetylation of cytoskeleton proteins and AMPAR subunits, whereas low levels of T-UCRs originating from the GRIA3 locus contribute to normal expression of GluR proteins. In MeCP2-mutant cells, high levels of circSIRT2s in the cytoplasm promote post-transcriptional upregulation of SIRT2 protein, which results in tubulin and GluR1 destabilization. In addition, upregulated uc.478 and uc.479 levels further downregulate GluR subunits with a global effect on the complexity of glutamatergic neurons. Dashed arrows indicate still unclear mechanisms of regulation. This figure was created with BioRender.

As a proxy for ncRNA function, our enrichment analysis of circRNA and T-UCR host genes revealed Gene Ontology categories related to glutamatergic signaling, specifically in the HIP, but not in the FC, of Mecp2 KO mice (Figures 1B, 1C, 4A, and 4B). Dysfunction in brain circuits and in the excitatory/inhibitory balance is a manifestation of altered molecular mechanisms downstream of MeCP2 loss but may differ from region to region. Glutamate signaling has an important role in learning and memory through the plasticity, or modification, of channel properties and synaptic anatomy, most notably in the HIP of the mammalian central nervous system.81 In this regard, glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, which is prominent in the HIP, has been associated with decreased neuronal regeneration and dendritic branching, leading to impaired spatial learning,82 and recent studies have reported a link between GluR receptors and RTT. Remarkably, de novo variants in GRIA2 cause neurodevelopmental disorders, including RTT-like features.83 The biogenesis of GRIA transcripts could be under direct control of MeCP2 because the protein directly regulates alternative splicing of many genes,84,85 including the flip/flop exons of the Gria1–Gria3 genes (without changing total mRNA) in the cortex of Mecp2 KO male and Mecp2−/+ female mice, influencing AMPAR-gated current and synaptic transmission.86 We found no significant differences in exon selection in the HIP of KO males, suggesting that this fine-tuning of alternative splicing is region specific. In contrast, we detected robust changes in editing rates in the postmortem HIP and an engineered neural progenitor cell line depleted in MeCP2 (Figure 5). Our data are consistent with direct regulation of T-UCRs by MeCP2 in a hypothetical scenario where MeCP2 recruitment to intragenic sites promotes or represses overlapping noncoding transcripts. The opposite roles of MeCP2, uc.478, and uc.479 in GRIA3 expression and protein levels (Figure 5) suggest complex regulatory dynamics that, in conjunction with alternative splicing selection and editing of the gene, strongly influence the function of the receptor. Editing and splicing have been linked to transport of AMPA receptors, and unedited transcripts are more efficiently targeted to dendrites,87 with a subsequent effect on protein stability. Thus, the hyperediting we observed in RTT samples could account for the lower levels of GluR3 protein noted in the absence of changes in mRNA levels. The great complexity of the glutamate system in the developing brain makes it a challenging target, but understanding its regulatory networks is essential for informed design of effective therapies. T-UCR and circRNA function may form the basis of this biogenesis, as indicated by this study and a recent report on circGRIA1, which is involved in age-related loss of synaptic plasticity by controlling GRIA1 transcription.37 The close relationship of these AMPA-type receptors with the PSD95 pathway, a major excitatory pathway downstream of BDNF and IGF1 signaling, deficient in RTT and the target of current therapeutic strategies,24,88,89 is further proof of the importance of understanding their biogenesis.

The other major altered pathway revealed by the ncRNA analysis in mice and also observed in the proteomics analysis of samples from affected individuals was that regulating trafficking and microtubule dynamics. Several studies have highlighted the occurrence of microtubule instability and microtubule-dependent deficits in RTT, which may underlie the well-documented abnormal neuronal morphology and synaptic plasticity of MeCP2-deficient brains and contribute substantially to the neuropathology of RTT.38,90,91 This includes alterations in microtubule polymerization dynamics in mouse models and MeCP2-mutant fibroblasts63,64 as well as impairment of mitotic spindle organization.92 MeCP2 has been coeluted with tubulins and other cytoskeleton components such as MAP6 (which we identify as upregulated in our proteomics analysis of postmortem RTT HIP) in co-immunoprecipitation studies,93 suggesting a direct effect of MeCP2 loss on cytoskeleton organization. Also related to cytoskeleton abnormalities, and similar to what is seen in mouse models of MeCP2 triplication syndrome94 (which has phenotypic similarities to RTT), we also detected an increase in the microtubule-associated tau protein in postmortem HIP.

Our data highlight the ability of ncRNA dysregulation to reveal key pathway abnormalities in the physiopathology of RTT. One general caveat of most transcriptomic studies in the field is the fact that expression profiles of specific genes differ greatly between studies, as meta-analysis have reported.54,95 This is probably a result of the heterogeneous models of study and the high dependency of MeCP2-directed gene expression regulation on varying neurodevelopmental conditions. However, the most severely changed biological pathways and processes tend to be the same in the different approaches, and our analysis of the most conserved subset of the noncoding transcriptome suggests that dysregulated ncRNAs are involved in the same key pathways. Further research on the mechanism of action of candidate species will provide insights into their value as potential therapeutic targets or as biomarkers of the disease. We anticipate that, in most cases, the concordant expression between host genes and circRNAs or T-UCRs confers the features of a putative biomarker. This might be particularly relevant for circular transcripts because they are stable molecules present in exosomes that are able to cross the blood-brain barrier, becoming accessible in most human biofluids and circumventing the problematic availability of brain biopsies.96 Further research is needed to ensure the maintenance of origination features, but exosomal circRNAs that could be specifically associated with early stages of neurodevelopmental disorders may be a promising tool for improving current diagnostic limitations.

In contrast, we also confirmed several cases of antagonistic expression, whereby production of the ncRNA may cross-talk with expression of the host gene. One important example is the SIRT2 locus, where early alterations in circRNA expression could confer biomarker features and reveal an extra layer of regulation of the SIRT2 gene mediated by ncRNAs. In this case, we hypothesize that the regulation we have shown by the circRNAs originating from the same locus in mouse and human models could function at the translational stage or even through interaction with the SIRT2 protein, similar to what has been described for circPABPN1 or circMBNL1,9,97 and underlie the changes in α-tubulin and GluR1 modifications that contribute to aberrant microtubule dynamics and AMPAR formation. However, we cannot rule out involvement of third partners mediating the regulation; namely, miRNAs, the most studied targets for circRNAs. Future studies will help clarify the detailed mechanism that explains how the family of circSIRT2 influences SIRT2 protein levels.

Despite major advances over the last two decades, restoration of MeCP2 levels to the physiological window of activity remains a major technical challenge in tackling RTT. No drug has so far been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treating RTT, and current treatments with other medications only partially address some of the symptoms. In the absence of an effective therapeutic agent, a better understanding of the contribution of the noncoding transcriptome to key dysregulated pathways is essential if we are to gain insights into two major aspects: (1) identification of molecules that are useful as biomarkers or therapeutic entry targets at all stages of the disease and (2) identification of new mechanisms and regulatory agents in gene expression control, metabolic pathways, and signaling processes downstream of MeCP2 function. Modulation of the expression of specific lncRNAs has shown promising results in Angelman and Dravet syndromes (whose symptoms overlap with those of RTT),98,99 and we anticipate that ncRNAs may become very useful tools in clinical research of RTT.

Materials and methods

Animals and RNA extraction for microarray analysis

Total RNA from the B6.129P2(c)-Mecp2tm1+1Bird mouse model of RTT25 was analyzed. The animals were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA; stock number 003890) and maintained on a C57BL/6J background. All animals were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions with a 12-h light-dark cycle, with drinking water and food available ad libitum. 20 Mecp2−/y (KO-null male) and 20 WT mice were used. All procedures and experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of the Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL) under the guidelines of Spanish animal welfare laws. Mice were euthanized following the biomedical research endpoint guidelines. Each brain region was isolated, weighed, and frozen on dry ice immediately after extraction and stored at −80°C until use.

Total RNA was extracted using the miRCURY RNA Isolation Kit – Cell & Plant (300110, Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. 20 mg of HIP and FC from 3 symptomatic (8-week-old) and 3 pre-symptomatic (4-week-old) animals was used per condition (WT and KO). The isolated RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (M6101, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to remove all DNA traces, and RNA integrity was assessed with a 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) microcapillary electrophoresis system using the RNA Nano 6000 Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of the RNA of all isolated RNA samples was analyzed using 5 ng RNA/sample input.

Postmortem samples

Postmortem brain tissue from control individuals and individuals with RTT was obtained from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) NeuroBioBank at the University of Maryland (Baltimore, MD, USA) and the Human Brain and Spinal Fluid Resource Center, VA West Los Angeles Healthcare Care Center (Los Angeles, CA, USA), which is sponsored by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders (NMSS), and Stroke (NINDS)/National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Cell culture of progenitor and differentiating cells

Immortalized human neural progenitors (ReNCells VM, SCC008) were purchased from Merck Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). The cells were obtained from 10-week-old ventral mesencephalon of fetal brain and immortalized with v-myc transfection, maintaining a pluripotent and proliferative state in the presence of two growth factors: basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF-2) (20 ng/mL, SRP4037) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) (20 ng/mL; SRP3027, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). ReNCells VM were cultured on laminin-coated plates (20 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with DMEM-F12 medium (L0093-500; Biowest, Nuaillé, France) containing 0.2% heparin (STEMCELL Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), B-27 complete vitamins (17504-044, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and antibiotic-antimycotic (L0010-100, Biowest, Nuaillé, France) at 37°C with maximum humidity in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. For subculturing, cells were detached using Accutase (SCR005, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and centrifuged for 5 min at 300 × g. Pellets were gently resuspended and plated after cell counting. The medium was replaced every other day, and cells were sub-cultured every 3–6 days when 90% confluence was reached. Spontaneous differentiation was performed by withdrawing EGF and bFGF-2 from the culture medium when 90% confluence was reached; ReNCells VM differentiated into a mixture of populations of neurons and glia (as described elsewhere).100 Treatment with AGK2 (A8231, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was conducted at 5 μM for 24 h; an equivalent concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle served as a control. Mouse Neuro 2a (N2a) cells (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC] CCL-131) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10270, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, as described elsewhere.101

MeCP2 editing by CRISPR-Cas9

CRISPR-Cas9 technology102 was used for engineering MECP2 KO in human ReNCells VM and mice N2a cells. The guide RNA (gRNA) targeting exon 4 of the human MECP2 genomic sequence (5ʹ-AAAAGCCTTTCGCTCTAAAG-3ʹ) was designed using the CRISPR Design tool page (http://crispr.mit.edu/), and the best-scored guide was selected and cloned into pSpCas9 (BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) (48138, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). The plasmid (2 μg) was delivered by nucleofection with A33 voltage (VPI-1003, Primary Neurons Kit, Amaxa, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) in progenitor ReNCells VM (2 million cells per experiment). After nucleofection, cells were coated on laminin-coated plates in complete medium (with EGF and bFGF-2) supplemented with Revitacell (A2644501, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for the first day. Two days after nucleofection, cells were detached and resuspended in PBS for flow cytometry selection. Cells containing green fluorescence (EGFP+) were selected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and then pooled and cloned. Sanger sequencing was performed using a 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) to confirm insertions or deletions (indels) within the targeted region after non-homologous end joining, resulting in a premature stop codon at position 133 of the amino acid sequence. For mouse N2a cells, all transfections were performed in 6-well plates, with 60%–80% confluence at the time of transfection. The gRNAs targeting exons 3 and 4 of the Mecp2 genomic sequence (5ʹ-GGGCGCTCCATTATCCGTGAC-3ʹ and 5ʹ-GGATTTTGACTTCACGGTAAC-3ʹ, respectively) were designed based on CrispR Gold software,103 and forward and reverse oligos were mixed and phosphorylated individually. Then annealed oligo duplexes were cloned into the BbsI sites of pSpCas9 (BB)-2A-GFP (PX458) (48138, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA). Transfection was performed with jetPRIME (114-15, Polyplus-transfection, Strasbourg, France) using 2 μg DNA and 4 μL reagent per well in 2 mL of cell growth medium, following the manufacturer’s instructions. 48 h after transfection, the transductant cells (EGFP+) were observed using optical microscopy. Isolation of clonal cells with specific modifications was performed by serial dilution, followed by an expansion time to establish a new clonal cell line. Mecp2 KO was confirmed by western blotting.

Plasmid construction

MeCP2 was restored in mouse and human MeCP2 KO cells. The mouse Mecp2 sequence was cloned into the pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen1 (632187, Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) vector using the oligos mMeCP2-EcoRI Fw and hMeCP2-BamHI Rv, into EcoRI and BamHI cutting sites. For the human MECP2 sequence, exons 4 and 3 were amplified from the genome with overlapping sequences using the oligos hMeCP2e1-Fus Fw and hMeCP2-ex3 Rv (for exon 3) and hMeCP2-ex4 Fw and hMeCP2-BamHI Rv (for exon 4). Moreover, exon 1 was engineered to replace 14 nucleotides with high content of C and G; the triplet substitution was done considering the preferential codon use, and the corresponding 13 amino acids were not altered. In both strategies, a Kozak sequence was inserted. Human circRNAs were cloned into the BstEII-H and SacII sites of the pcDNA3.1(+) CircRNA Mini Vector (60648, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) with the following oligos: circ_0050945 BstEII Fw (forward for hsa_circ_0050945, hsa_circ_0050946, and hsa_circ_0050948), circ_0050951 BstEII Fw (forward for hsa_circ_0050951), circ_0050945 SacII Rv (reverse for hsa_circ_0050945), circ_0050946 SacII Rv (reverse for hsa_circ_0050946), circ_0050948 SacII Rv (reverse for hsa_circ_0050948), and circ_0050951 SacII Rv (reverse for hsa_circ_0050951). Mouse circRNA (mmu_circRNA_41253) was cloned between EcoRV and BstEII sites with the following oligos: mmu_circ_41253 EcoRV Fw and mmu_circ_41253 BstEII Rv. To improve circularization, a sequence of 35 nt upstream and downstream of introns was added. uc.478 and uc.479 were overexpressed by cloning into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the vector pLVX-shRNA2 (632179, Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) using the following oligos: Uc478-BamHI Fw and Uc478-EcoRI Rv for uc.478 and Uc479-BamHI Fw and Uc479-EcoRI Rv for uc.479. The pcDNA4TO- SIRT2-hemagglutinin (HA) plasmid104 was a gift from Dr. Vaquero’s lab (IJC, Badalona, Spain).

Transfection and lentivirus production/infection

Cells were plated on 100-mm dishes 24 h before the experiment, and cloned circRNAs plasmids were transfected with Lipofectamine Stem Reagent (STEM00003, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the company guidelines. The empty pcDNA3.1(+) CircRNA Mini Vector was used as a control. For pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen1, pLVX-shRNA2 constructs and glutamatergic differentiation vectors (TetOhNGN2-P2A-EGFP-T2A-PuroR and CMV-rtTA), lentiviral particles were produced in HEK293T cells as described below. HEK293T cells were cultivated in DMEM with GlutaMAX (31966-021, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10270, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. HEK293T cells were triple-transfected with specific vectors plus packaging plasmids with jetPRIME (114-15, Polyplus-transfection, Strasbourg, France) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Viral particles with pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen1 and pLVX-shRNA2 empty vector were used as a control. Lenti-X Concentration (PT4421-2, Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA) was used for concentrating viral particles in DMEM-F12 medium. Cells were infected with viral particles, followed by a 2-day recovery period before the experiments started. ZsGreen1 was used as a marker to visualize transductants cells by fluorescence microscopy for pLVX-IRES-ZsGreen1 plasmids, whereas the TetO-hNGN2-P2A-EGFP-T2A-PuroR vector was selected by puromycin (ant-pr, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) and visualized with EGFP fluorescence.

Glutamatergic differentiation protocol

Glutamatergic differentiation was performed as described by Ho et al.105 Briefly, cells were seeded on laminin-coated plates 24 h before infection. Cells were double-infected with TetO-hNGN2-P2A-EGFP-T2A-PuroR and CMV-rtTA as described above. 48 h after infection, doxycycline (1 μg/mL) was administered to the cells, followed by puromycin (0.5 μg/mL) the next day. After 24 h of puromycin selection, EGF and FGF-2 were withdrawn from the medium, and cells were allowed to differentiate for 21 days. During the first week of differentiation, half of the medium was changed every day, maintaining doxycycline concentration. In the second week of differentiation, the medium was changed every other day, reducing doxycycline concentration to half with each change until complete removal by the last week of differentiation. qRT-PCR was performed to confirmed overexpression of glutamatergic marker VGlut1.

Neurosphere formation assay

Neurosphere formation was performed as proposed by Donato et al.100 Briefly, 2.5 million cells were cultured in non-coated flasks with complete medium (EGF and FGF-2) to induce neurospheres formation. After 24 h of plating, images were acquired with a 20× objective in under a DM IL LED Fluo microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Sphere diameter was measured using ImageJ software (v.1.53k).

Analysis of neuronal morphology

WT and MeCP2-KO cells overexpressing T-UCRs and the pLVX-shRNA2 empty vector were differentiated on glass coverslips for 7 days following the glutamatergic differentiation protocol described above. Neuronal morphology was analyzed after an immunofluorescence assay as follows. the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS buffer with 1 mM NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2 for 30 min at room temperature (RT). The coverslips were blocked with 5% BSA and 5% goat serum in 0.3% Triton™ X-100 (X100, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS buffer for 1 h at RT. The primary antibody anti-MAP2 (1:400; 8707, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) was diluted in the same blocking solution and incubated overnight. A secondary antibody (1:1,000, anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555; A31572, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was incubated for 1 h at RT in the dark. Coverslips were washed between steps with PBS three times for 5 min each. DAPI (5 mg/mL) was used for nucleus staining. Coverslips were mounted in Mowiol solution and dried overnight at RT, protected from the light. The images were acquired under a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (CMRB, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain) and analyzed using ImageJ software (v.1.53k). Neurons were reconstructed using NeuroStudio software (v.0.9.92) as described elsewhere.49 Briefly, a three-dimensional dendritic network was built with a Sholl analysis by automated segmentation, and concentric circles were drawn from the soma (over a length of 20 μm with concentric circles of 10 μm) throughout the projection’s length. Neuronal components are categorized and represented by spheres: the soma is represented in red; neurites are tracked in green, branchpoints are represented in yellow, and spines are colored in orange, pink, and gray according to their subtype (stubby, mushroom, and thin). An estimation of spines density was retrieved, and the spines were counted (n = 20 neurons per condition).

circRNA microarray analysis

Total RNA from each sample was treated with RNase R to enrich the circRNA. The enriched circRNA was then amplified and transcribed into fluorescent cRNA using random primers according to the Arraystar Super RNA Labeling protocol (Arraystar, Rockville, MD, USA). The labeled cRNAs were hybridized onto the Arraystar Mouse Circular RNA Microarray V2 (8 × 15 K) and incubated for 17 h at 65°C in an Agilent hybridization oven. After washing with PBS, slides were scanned with a G2505C scanner (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

circRNA data analysis

Data were extracted using Agilent Feature Extraction software. A series of data processing operations, including quantile normalization, was performed using the Limma 3.22.7 package in R. After quantile normalization of the raw data, low-intensity filtering was performed, and the circRNAs for which at least 3 of 12 samples had “P” or “M” flags (defined by GeneSpring software) were retained for further analyses. Significantly DE circRNAs (t test, p < 0.05) and a greater than 1.5-fold difference in expression between the two groups were identified through volcano plot filtering. Hierarchical clustering was performed to distinguish different patterns of circRNA expression among the samples.

T-UCR microarray analysis

We used a customized single-channel Agilent array (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which was deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GPL22858). It contains a collection of sense and antisense probes for various types of ncRNAs (18,009 probes corresponding to 1,271 human pre-miRNAs, 8,660 probes corresponding to 626 mouse pre-miRNAs [miRBase 21], 2,745 probes corresponding to 479 ultra-conserved elements, 16,314 probes corresponding to 1,283 human-specific transcribed pyknons, and 2,197 probes corresponding to 97 lncRNAs). The hybridization was performed as described.106 Data preprocessing steps of background correction, normalization, and summarization were performed in R v.3.5.1 (https://www.r-project.org/) using functions in the Limma library.107 A threshold for positive spot selection was calculated as the mean value of all dark corner spots plus twice the standard deviation.108 Linear models and empirical Bayes methods from Limma were used to obtain the statistics and assess differential gene expression between two sample types. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of less than 0.05, and we imposed a cutoff of functional relevance on the fold change in absolute value of 1.1.

GluR-1 immunoprecipitation (IP)

Cell pellets were lysed in stringent RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 50 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% SDS, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail) supplemented with deacetylase inhibitors (100 μM trichostatin A, 50 mM sodium butyrate, and 50 mM nicotinamide), incubating for 30 min in a rocker at 4°C. Lysates were then cleared by centrifugation, and protein concentration was measured. 1 mg of total extract was incubated with 5 μg of anti-GluR-1 rabbit antibody (ab109450, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) or control rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (I5006, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 60 μL of Dynabeads M-280 sheep anti-rabbit IgG (11204D, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 h at 4°C. Beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer and boiled in the presence of Laemmli buffer for western blot analysis.

RNA IP

To retrieve the RNA species bound by MeCP2, we used the protocol described by Cheng et al.109 with minor variations. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of CLIP lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 100 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal CA-630, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 1× protease inhibitor cocktail), sonicated on ice at 10%–15% of amplitude for 30 s (5 s on and 10 s off), and treated with 14 U of Turbo DNase (AM2238, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C for 5 min. Lysates were then cleared by centrifugation, and protein concentration was measured. mg of protein was immunoprecipitated for 2 h at RT with 5 μg of MECP2 antibody (M9317, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or control rabbit IgG antibody (I5006, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) preincubated for 30 min at RT with 50 μL Dynabeads M-280 sheep anti-rabbit IgG (11204D, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The pulled down RNA was extracted by adding 1 mL of TRIzol reagent (15596-018, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After phenol extraction, isopropanol precipitation, and DNase treatment, the final pellet was resuspended in 20 μL H2O. Each RNA sample was split into 2 tubes; one tube was reverse transcribed, and the other was mock treated (without reverse transcriptase). cDNA was analyzed by qPCR. Input material processed in parallel was used to estimate pull-down efficiency.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

For mRNA, circRNA, and T-UCR expression analysis, total RNA was extracted with the Maxwell RSC miRNA Tissue Kit (AS1460, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The isolated RNA was treated with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (M6101, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) (twice for the T-UCR analysis) and reverse transcribed using the RevertAid RT Reverse Transcription Kit (K1691, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A negative control without reverse transcriptase was run in parallel to control for genomic contamination. Real-time PCR reactions were performed in triplicate in the QuantStudio 5 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), using 10–60 ng cDNA, 6 μL SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and 416 nM primers in a final volume of 12 μL for 384-well plates. All data were acquired and analyzed with QuantStudio Design & Analysis Software v.1.3.1 and normalized with respect to B2m as an endogenous control in mouse samples and L13 in human samples. Relative RNA levels were calculated using the comparative Ct method (ΔΔCt). A list of the primers used can be found in Table S1.

Western blot

20 mg of mouse FC or HIP and human postmortem HIP were resuspended in Laemmli buffer (2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 60 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], and 0.01% bromophenol blue), sonicated, and boiled for 5 min at 95°C. The sample concentration was determined by quantifying the absorbance at 260 nm with a NanoDrop One/OneC Microvolume UV spectrophotometer and using the equivalency between DNA and histone quantity (6 units A260nm [DNA] = 1 μg/μL of protein). Proteins were transferred to a 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membrane (10600001, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) and incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody diluted in 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (663684B, Atlas Chemical, Houston, TX, USA). After three washes with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, membranes were incubated for 1 h at RT in a benchtop shaker with the secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000, A0545; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000; NA9310, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Luminata-HRT; Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) were used to visualize the proteins. Films were scanned, and the band analysis tool of the Quantity One software application was used for background subtraction and to determine the density of the bands. The proteins detected were MeCP2 (1:1,000; ab2829, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), SIRT2 (1:2,000; ab211033, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), acetyl-α-tubulin (1:2,000; T6793, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), α-tubulin horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:5,000; ab40742, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), β-actin HRP (1:30,000; a3854, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), TAU (1:1,000; ab64193, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), MAP6/STOP (1:1,000; 4265, Cell Signal, Danvers, MA, USA), STMN1 (1:500; 3352, Cell Signal, Danvers, MA, USA), S100b (1:1,000; Z0311, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), GluR-1 (1:1,000; ab109450, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), GluR-2 (1:1,000, 13607, Cell Signal, Danvers, MA, USA), GluR-3 (1:2,000; 4676, Cell Signal, Danvers, MA, USA), acetyl-lysine (1:1,000; ab80178, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), ADAR2 (1:400; HPA018277, Atlas Antibodies, Bromma, Sweden), SOX2 (1:1,000; 3579, Cell Signal, Danvers, MA, USA), and Ki67 (1:1,000; ab16667, Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation and poly(A) selection

Subcellular fractionation was performed with a PARIS kit (AM1921, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Proportional amounts of RNA from each fraction were subjected to qRT-PCR, and the results were normalized, considering the total quantity of RNA recovered from each fraction. MALAT1 and GAPDH primers were used as controls to verify nuclear and cytoplasmic separation of the mRNA. At the protein level, separation was confirmed by western blot with histone H3 (1:5,000; ab1791, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and α-tubulin HRP (1:5,000; ab40742, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Additionally, MeCP2 (1:1,000; ab2829, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was detected by western blot to confirm nuclear localization and absence in human KO cells. A Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (61006, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to separate poly(A)+ and poly(A)− RNAs, following the manufacturer’s instructions and performing three rounds of selection. RNA enrichment in each sample was analyzed by qRT-PCR, using GAPDH and MALAT1 as controls for poly(A)+ and poly(A)− samples, respectively.

ChIP assay