Abstract

We present herein the development of a series of viologen–amino acid hybrids, obtained in good yields either by successive alkylations of 4,4′-bipyridine, or by Zincke reactions followed by a second alkylation step. The potential of the obtained amino acids has been exemplified, either as typical guests of the curcubituril family of hosts (particularly CB[7]/[8]) or as suitable building blocks for the solution/solid-phase synthesis of two model tripeptides with the viologen core inserted within their sequences.

Viologens (Vs), compounds resulting from the diquaternization of 4,4′-bipyridine, are one of the most studied classes of stimuli-responsive moieties in chemistry, mainly due to their synthetic accessibility and adjustable properties, such as reversible redox behavior and π-acceptor character.1 Consequently, this broad family of organic salts has been extensively used in a variety of practical applications,2 including the development of V-based electrochromic materials3 or, more recently, aqueous redox flow batteries.4,5

Furthermore, their high tunability and stimuli-responsiveness have made Vs prime components on the evolution of supramolecular chemistry. For instance, Vs can be found as the key parts of the family of macrocyclic receptors known as ExBoxes developed by Stoddart et al.6 or as archetypical guests of relevant hosts7 such as aryl-containing coronands,8 pillarenes,9 or cucurbiturils10,11 (referred in this paper as CB[n]s, n = 7,8; Figure 1). In particular, the host–guest chemistry of viologens and CB[8] is currently highly significant,12 as heteroternary complexes can be prepared in a predictable fashion, typically by using a V as first guest and an electron donor as second (D). Furthermore, the very accessible and reversible first reduction potential of Vs enables the controlled assembly/disassembly of the obtained CB[8]:V:D [3]pseudorotaxane in very convenient experimental conditions. Hence, this redox-controlled “handcuff strategy” has become the weapon of choice not only for the transient heteroligation of discrete small molecules by CB[8]10−13 but also for the creation of more complex assemblies.10−14

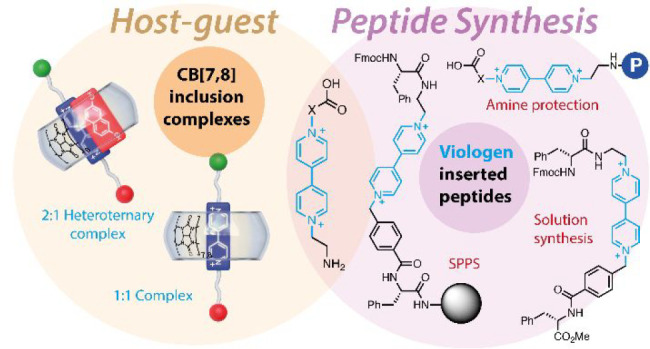

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of the V–amino acid hybrids discussed in this work and of the CB[n] (n = 7, 8) hosts.

Following our interest in the supramolecular chemistry of pyridinium salts,15 we initiated a research program focused on the CB[n]-based modification of peptides owning appropriate viologen moieties as binding motifs.16 In this context, we found the lack of a general methodology for the insertion of the V core within peptide sequences, with most of the procedures reported so far being focused on the end-capping or lateral chain modification of the oligomer with the electroactive motif.16−18 Consequently, we envisaged the synthesis of a series of viologen–amino acid hybrids (Figure 1) that would potentially allow for their implementation in liquid or solid phase peptide synthesis (L/SPPS) and could retain the characteristics required for the CB[7,8]-based molecular recognition.

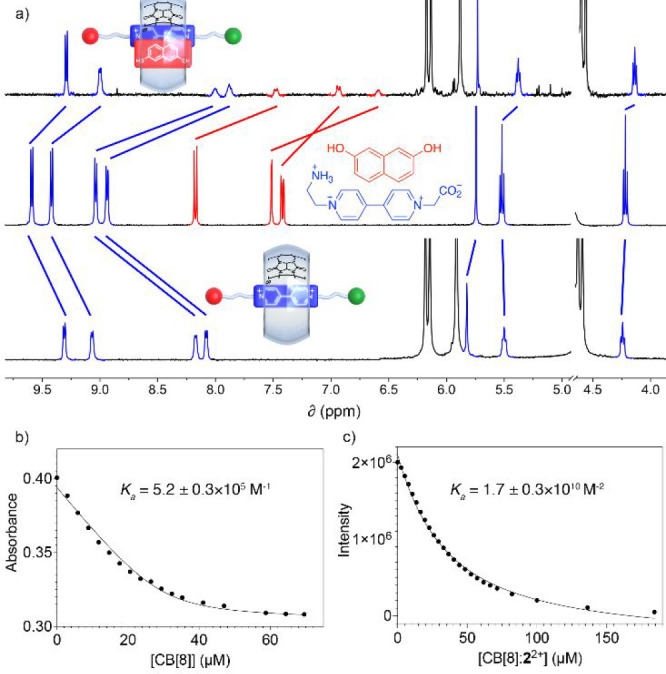

Considering the well-established methodology for the synthesis of unsymmetrical Vs,2,19 we first tackled the synthesis of a V–amino acid hybrid by direct introduction of the envisioned functional groups through successive alkylation reactions of the 4,4′-bipyridine (BP) core. As shown in Scheme 1, the unprotected amino acid 2H·3Cl could be prepared by reaction of BP with commercially available 2-bromoethan-1-amonium bromide, followed by a second alkylation of the intermediate 1H·2Br with ethyl 2-bromoacetate, and a final step for the hydrolysis of the corresponding ester with aqueous HCl, which produces as well the complete metathesis of the bromide counterions, leading to the trichloride salt in a decent 36% overall yield.20

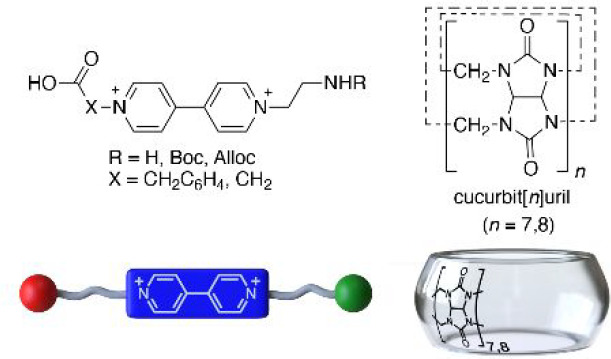

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Amino Acid 2H·3Cl and Representation of the Binary CB[7,8]:22+ and Heteroternary CB[8]:22+:2,7-DHN Complexes.

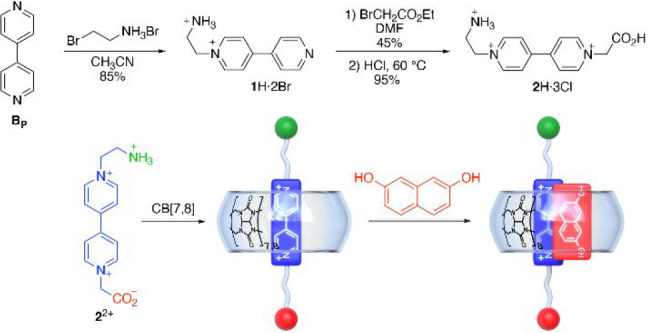

To test the ability of the obtained amino acid as appropriate guest for CB[n]s, we proceeded to study the complexation of the zwitterionic form 22+ by CB[7]/[8] in buffered aqueous media at pD = 7; a fact that would simplify the assessing of the binding interactions by means of 1H NMR spectroscopy.21 Both in the case of CB[7] and CB[8], the changes observed in the NMR spectra of guest 22+ upon addition of increasing quantities of host22 are in agreement with the complexation of the V moiety following a fast, but near coalescence, exchange rate on the NMR time scale. In both cases, the complexation-induced shifts (CISs) for equimolar mixtures of host and guest (see, for instance, Figure 2a)22 are fully consistent with the inclusion process producing 1:1 symmetric pseudorotaxanes. In essence, the shielding of the signals attributable to the viologen core of 22+ as well as the slight deshielding of the methylene pendant groups of the guest suggest the expected binding mode with the V core inserted within the cavity of the hosts as in similar systems.10 ESI-MS spectrometry also verified the formation of the binary complexes, with intense peaks corresponding to the expected species being detected for [CB[7]:2]+2 at (m/z) calcd 711.7428, found 711.7434 and for [CB[8]:2]+2 at (m/z) calcd 794.7674, found 794.7679.22 Furthermore, UV–vis titration experiments allowed for the assessment of the association constants, with the obtained data fitting appropriately to 1:1 isotherms with Ka (CB[7]:22+) = (5.7 ± 0.5)105 M–1 and Ka (CB[8]:2) = (5.2 ± 0.3) 105 M–1 (Figure 2b), values in good agreement with those previously reported for similar systems.10

Figure 2.

(a) Partial 1H NMR spectra (D2O, 500 MHz) for equimolar (1 mM) mixtures at 343.15 K of (middle) 22+ and 2,7-DHN, (top) 22+, 2,7-DHN and CB[8], and (bottom) 22+ and CB[8]. (b) Fitting of the observed variation in the absorption at λ = 272 nm of a 29.4 μM 22+ solution in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH = 7.0), upon addition of increasing concentrations of CB[8]. (c) Fitting of the observed variation in the fluorescence emission at λem= 345 nm of a 10 μM 2,7-DHN solution in phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH = 7.0), upon addition of increasing concentrations of CB[8]:22+.

Finally, the obtention of the heteroternary complex between CB[8], 22+, and 2,7-DHN, as a typical second guest, was also tested by NMR (Figure 2a). Although some of the resonances for the two guests disappear because of a near-coalescence exchange regime on the technique at rt,22 the problem was surpassed by recording the experiment at 343.15 K for a 1:1:1 mixture of the compounds at 1 mM (Figure 2a), clearly showing the expected CISs for this type of complexes. Furthermore, the inclusion of 2,7-DHN as a second guest was also corroborated by fluorescence titrations, which allowed us to estimate the overall Ka (CB[8]:22+:2,7-DHN) = (1.7 ± 0.3) 1010 M–2 (Figure 2c).22

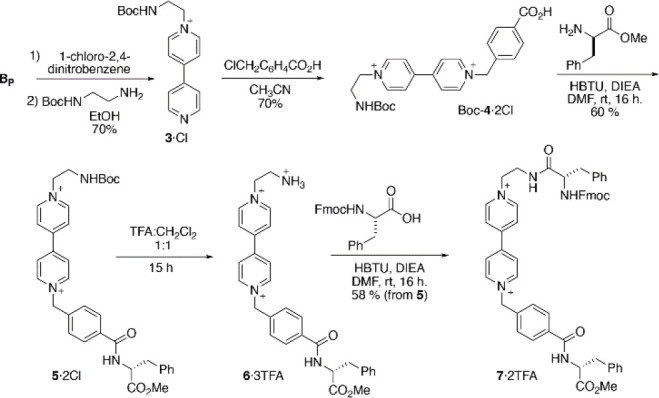

Following the development of the V-containing amino acids for peptide synthesis, we envisaged two main modifications on the previously discussed synthetic route: (a) replacement of the 1-(carboxymethyl)pyridin-1-ium moiety for a more stable acid functionality (i.e., 1-(4-carboxybenzyl)pyridin-1-ium),18 able to surpass potential decomposition by decarboxylation (vide supra)20 and (b) the introduction of suitable amino protecting groups within our V–amino acid hybrids.23 Consequently, we decided to tackle first the obtention of compound Boc-4·2Cl, a tert-butylcarbonyl (Boc)-N-protected derivative suitably protected for LPPS. In this case, the V–amino acid hybrid was synthesized in a good 49% overall yield, first by the Zincke reaction between readily available N-Boc-ethylene diamine and the 2,4-dinitrobenzene-activated salt of BP,19 followed by a subsequent alkylation of intermediate 3·Cl with 4-(chloromethyl)benzoic acid (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of the N-Protected V–Amino Acid Hybrid Boc-4·2Cl and Its Implementation on the Synthesis of the Model Tripeptide 7·2TFA.

With the N-protected amino acid Boc-4·2Cl in our hands, we proceeded to assess its use on LPPS by addressing the preparation of the simple model tripeptide Fmoc-l-Phe-4-d-Phe-OMe·2TFA (7·2TFA). The synthesis of this compound was performed from the C- to N-terminus so, first, Boc-4·2Cl was coupled to the d-phenylalanine methyl ester to give the dipeptide 5·2Cl. Next, cleavage of the Boc group with TFA resulted in the ammonium salt 6·3TFA, which was subsequently used without further purification on the final coupling with Fmoc-l-Phe-OH leading to 7·2TFA. The compound was obtained on a decent 35% overall yield, with an analytical sample being purified by HPLC, and extensively characterized by ESI-MS spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy (Figure 3).

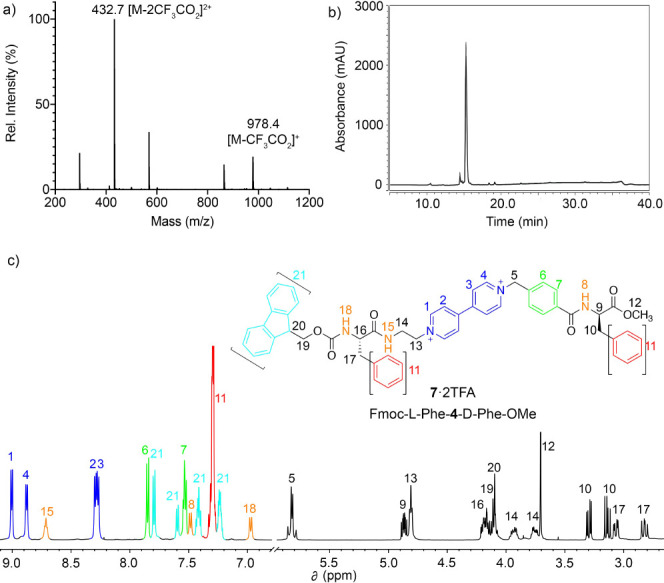

Figure 3.

(a) MS spectrum corresponding to the peak at tR = 16 min of the HPLC chromatogram at 220 nm (b) for 7·2TFA. (c) Partial 1H NMR spectra (CD3CN, 500 MHz) for 7·2TFA including the assignation based on 1D and 2D NMR.

Among other features, the assignation of the 1H NMR spectrum of 7·2TFA allows us to identify in the aromatic region not only distinctive resonances attributable to the benzyl, phenylene, and Fmoc moieties but also the other four characteristic doublets of the V core. Regarding the ESI-MS, the spectrogram shows the signal attributable to the 72+ cation as the base peak at m/z calcd for [M – 2CF3CO2]2+ 432.6914, found 432.6915.

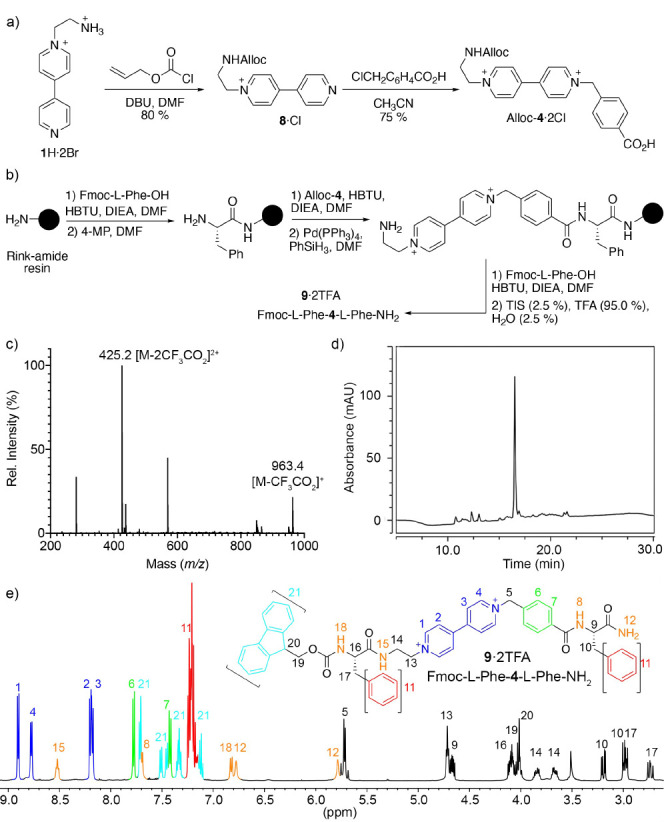

Finally, we tackled the implementation of our V–amino acid hybrids into SPPS. For this purpose, we devised first the synthesis of the appropriate N-protected amino acid Alloc-4·2Cl, having an Alloc group, orthogonal to Fmoc, and that would enable the classic Fmoc/t-Bu SPPS strategy.24 To obtain Alloc-4·2Cl, we used a slight modification of the synthetic protocol explained above for Boc-4·2Cl (Scheme 1), with the introduction of the protecting group on intermediate 1H·2Br just before the second alkylation of BP (Figure 4a). In that manner, the targeted amino acid was successfully synthesized in an excellent 51% overall yield, simply by reaction of the aminoethylbipyridium 1H·2Br with allyl chloroformate followed by the introduction of the corresponding 4-(chloromethyl)benzoic acid moiety. Consequently, by using the Fmoc/t-Bu strategy on a Rink amide resin, we followed with the SPPS of the model tripeptide Fmoc-l-Phe-4-l-Phe-NH2 (9·2TFA). As shown in Figure 4b, that was achieved by coupling of Fmoc-l-Phe-OH to the resin and subsequent deprotection, followed by introduction of the V moiety by coupling of Alloc-4·2Cl using HBTU/DIEA in DMF. Alloc deprotection using a slight modification of the classic Pd(PPh3)4/PhSiH3 method,25 immediately followed by the coupling of Fmoc-l-Phe-OH and cleavage from the solid support, led to tripeptide 9·2TFA on a 6% overall yield after semipreparative HPLC purification. The associated ESI-MS spectrogram for the main peak on the HPLC chromatogram showed peaks at m/z = 963.3699 and m/z = 425.1915 corresponding to the loss of the trifluoroacetate anions on the expected structure (Figure 4c,d). Furthermore, the 1D/2D NMR experiments recorded in CD3CN/D2O for the purified reaction product showed data fully consistent with that observed for 7·2TFA and expected for 9·2TFA and allowed for a full assignment of the 1H/13C nuclei in the molecule. As in the case of 7·2TFA, the introduction of the V moiety within the analogous tripeptide 9 can be easily inferred from the diagnostic resonances of the electroactive unit on the 1H NMR (Figure 4e).

Figure 4.

(a) Synthesis of the N-Alloc protected V–amino acid hybrid Alloc-4·2Cl. (b) SPPS of the model tripeptide 9·2TFA. (c) MS spectrum corresponding to the peak at tR = 16.6 min of the HPLC chromatogram at 220 nm (d) for 9·2TFA. (e) Partial 1H NMR spectra (CD3CN, 500 MHz) for 9·2TFA including the assignation based on 1D and 2D NMR data.

Finally, we tried to qualitatively assess the interaction between one of our model peptides (7·2TFA) and CB[8]. Hence, a 1 mM solution of 7·2TFA, in D2O with 50 mM phosphate buffer solution at pD = 7, was saturated with CB[8] and the corresponding 1H NMR recorded after filtration of excess nondissolved macrocyle.22 Although the resulting complex pattern of broadened signals qualitatively imply an interaction between CB[8] and the amino acid–viologen hybrid, further extensive investigation would be needed in order to properly characterize this intricate system.17

In summary, we have described in this work the development of a series of viologen–amino acid hybrids that have been efficiently prepared both as “naked” or as N-protected derivatives suitable for L/SPPS. The ability of obtained amino acids as typical first guests of the cucurbituril family of hosts was explored for the unprotected derivative 2H·3Cl, being found to behave in a similar fashion with both CB[7] and CB[8], as other simple viologen derivatives. Furthermore, we have corroborated the implementation of the N-protected derivatives Boc-4·2Cl and Alloc-4·2Cl on, respectively, the L and SPPS of a model tripeptide having the Phe-V-Phe sequence. Overall, these results expand considerably not only the toolbox for the synthesis of new (redox) stimuli-responsive peptide materials,26 but they open as well the door for the transient noncovalent modification of peptide structures by means of CB[8]-based heteroternary complexation,27 an area that we are currently exploring in our laboratories.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the funding received from the Agencia Estatal de Investigación and FEDER (PID2019-105272GB-I00 and CTQ2017-89166-R), the Consellería de Educación, Universidade e Formación Profesional, Xunta de Galicia (ED431C 2018/39 and 508/2020), and the European Research Council (Grant Agreement No. 851179). I.N. thanks the MECD (FPU program) for financial support. E.P. thanks the Agencia Estatal de Investigación for her Ramón y Cajal contract (RYC2019-027199-I). Funding for open access charge: Universidade da Coruña/CISUG.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.1c02040.

Experimental procedures, characterization data for new compounds, and titration experiments for CB[7,8]complexes (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Monk P. M. S.The Viologens: Physicochemical Properties, Synthesis, and Applications of the Salts of 4,4′-Bipyridine; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- For recent reviews on viologens and viologen-based materials, see:; a Striepe L.; Baumgartner T. Viologens and Their Application as Functional Materials. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 16924–16940. 10.1002/chem.201703348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ding J.; Zheng C.; Wang L.; Lu C.; Zhang B.; Chen Y.; Li M.; Zhai G.; Zhuang X. Viologen-inspired functional materials: synthetic strategies and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 23337–23360. 10.1039/C9TA01724K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhou X.-H.; Fan Y.; Li W.-X.; Zhang X.; Liang R.-R.; Lin F.; Zhan T.-G.; Cui J.; Liu L.-J.; Zhao X.; Zhang K.-D. Viologen derivatives with extended π-conjugation structures: From supra-/molecular building blocks to organic porous materials. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 1757–1767. 10.1016/j.cclet.2019.12.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Shah K. W.; Wang S.-X.; Soo D. X. Y.; Xu J. Viologen-Based Electrochromic Materials: From Small Molecules, Polymers and Composites to Their Applications. Polymers 2019, 11, 1839. 10.3390/polym11111839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Madasamy K.; Velayutham D.; Suryanarayanan V.; Kathiresan M.; Ho K.-C. Viologen-based electrochromic materials and devices. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 4622–4637. 10.1039/C9TC00416E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Lu W.; Zhang H.; Li X. Aqueous Flow Batteries: Research and Development. Chem. - Eur. J. 2019, 25, 1649–1664. 10.1002/chem.201802798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see:; a Hu B.; DeBruler C.; Rhodes Z.; Liu T. L. Long-Cycling Aqueous Organic Redox Flow Battery (AORFB) toward Sustainable and Safe Energy Storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1207–1214. 10.1021/jacs.6b10984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b DeBruler C.; Hu B.; Moss J.; Liu X.; Luo J.; Sun Y.; Liu T. L. Designer Two-Electron Storage Viologen Anolyte Materials for Neutral Aqueous Organic Redox Flow Batteries. Chem. 2017, 3, 961–978. 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Liu Y.; Li Y.; Zuo P.; Chen Q.; Tang G.; Sun P.; Yang Z.; Xu T. Screening Viologen Derivatives for Neutral Aqueous Organic Redox Flow Batteries. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 2245–2249. 10.1002/cssc.202000381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Dale E. J.; Vermeulen N. A.; Juricek M.; Barnes J. C.; Young R. M.; Wasielewski M. R.; Stoddart J. F. Supramolecular Explorations: Exhibiting the Extent of Extended Cationic Cyclophanes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 262–273. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang Y.; Frasconi M.; Stoddart J. F. Introducing Stable Radicals into Molecular Machines. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 927–935. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent reviews discussing the chemistry of viologens as guests of different macrocyclic hosts, see:; a Ashwin B. C. M. A.; Shanmugavelan P.; Muthu Mareeswaran P. Electrochemical aspects of cyclodextrin, calixarene and cucurbituril inclusion complexes. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2020, 98, 149–170. 10.1007/s10847-020-01028-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Surveying macrocyclic chemistry: from flexible crown ethers to rigid cyclophanes:Liu Z.; Nalluri S. K.; Mohan; Stoddart J. F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2459–2478. 10.1039/C7CS00185A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Blanco-Gomez A.; Cortón P.; Barravecchia L.; Neira I.; Pazos E.; Peinador C.; García M. D. Controlled binding of organic guests by stimuli-responsive macrocycles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3834–3862. 10.1039/D0CS00109K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Yan X.; Huang F.; Niu Z.; Gibson H. W. Stimuli-Responsive Host–Guest Systems Based on the Recognition of Cryptands by Organic Guests. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1995–2005. 10.1021/ar500046r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M.; Yang Y.; Chi X.; Zhang Z.; Huang F. Pillararenes, A New Class of Macrocycles for Supramolecular Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1294–1308. 10.1021/ar2003418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucurbituril-based molecular recognition.; Barrow S. J.; Kasera S.; Rowland M. J.; del Barrio J.; Scherman O. A. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12320–12406. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucurbiturils and Related Macrocycles; Kim K., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pazos E.; Novo P.; Peinador C.; Kaifer A. E.; García M. D. Cucurbit[8]uril (CB[8])-Based Supramolecular Switches. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 403–416. 10.1002/anie.201806575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko Y. H.; Kim E.; Hwang I.; Kim K. Supramolecular assemblies built with host-stabilized charge-transfer interactions. Chem. Commun. 2007, 13, 1305–1315. 10.1039/B615103E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See, for instance:; a Liu Y.-H.; Zhang Y.-M.; Yu H.-J.; Liu Y. Cucurbituril-Based Biomacromolecular Assemblies. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3870–3880. 10.1002/anie.202009797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yang X.; Wang R.; Kermagoret A.; Bardelang D. Oligomeric Cucurbituril Complexes: from Peculiar Assemblies to Emerging Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 21280–21292. 10.1002/anie.202004622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zou H.; Liu J.; Li Y.; Li X.; Wang X. Cucurbit[8]uril-Based Polymers and Polymer Materials. Small 2018, 14, 1802234. 10.1002/smll.201802234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neira I.; Blanco-Gómez A.; Quintela J. M.; García M. D.; Peinador C. Dissecting the “Blue Box”: Self-Assembly Strategies for the Construction of Multipurpose Polycationic Cyclophanes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2336–2346. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Solid-phase Zincke reaction for the synthesis of peptide-4,4′-bipyridinium conjugates.Corton P.; Novo P.; López-Sobrado V.; García M. D.; Peinador C.; Pazos E. Synthesis 2020, 52, 537–543. 10.1055/s-0039-1690016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Novo P.; García M. D.; Peinador C.; Pazos E. Reversible Control of DNA Binding with Cucurbit[8]uril-Induced Supramolecular 4,4′-Bipyridinium-Peptide Dimers. Bioconjugate Chem. 2021, 32, 507–511. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.1c00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See, for instance:; a Oh K. J.; Cash K. J.; Hugenberg V.; Plaxco K. W. Peptide Beacons: A New Design for Polypeptide-Based Optical Biosensors. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007, 18, 607–609. 10.1021/bc060319u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Reczek J. J.; Rebolini E.; Urbach A. R. Solid-Phase Synthesis of Peptide–Viologen Conjugates. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 2111–2114. 10.1021/jo100018f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Clarke D. E.; Olesińska M.; Mönch T.; Schoenaers B.; Stesmans A.; Scherman O. A. Aryl-viologen pentapeptide self-assembled conductive nanofibers. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 7354–7357. 10.1039/C9CC00862D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Otter R.; Besenius P. Probing the Folding of Peptide–Polymer Conjugates Using the π-Dimerization of Viologen End-Groups. Organic Materials 2020, 02, 143–148. 10.1055/s-0040-1710343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallouk et al. have reported the synthesis of V-containing (S)-valine-leucine-alanine peptidic cyclophane.; Gavin J. A.; García M. E.; Benesi A. J.; Mallouk T. E. Chiral Molecular Recognition in a Tripeptide Benzylviologen Cyclophane Host.. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 63, 7663–7669. 10.1021/jo980352c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domarco O.; Neira I.; Rama T.; Blanco-Gómez A.; García M. D.; Peinador C.; Quintela J. M. Synthesis of non-symmetric viologen-containing ditopic ligands and their Pd(ii)/Pt(ii)-directed self-assembly. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 3594–3602. 10.1039/C7OB00161D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromoacetic acid was not directly used as an alkylating agent, as it has been thoroughly reported that the reaction of BP derivatives with haloacetic acid often produces N-methylated derivatives upon prolonged heating and by decarboxylation of the corresponding 1-(carboxymethyl)pyridin-1-ium moiety. See, for instance:; a Yang C.; Wang M.-S.; Cai L.-Z.; Jiang X.-M.; Wu M.; Guo G.-C.; Huang J.-S. Crystal structures and visible-light excited photoluminescence of N-methyl-4,4′-bipyridinium chloride and its Zn(II) and Cd(II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2010, 13, 1021–1024. 10.1016/j.inoche.2010.05.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hagemann T.; Strumpf M.; Schroeter E.; Stolze C.; Grube M.; Nischang I.; Hager M. D.; Schubert U. S. (2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl-Containing Zwitterionic Polymer as Catholyte Species for High-Capacity Aqueous Polymer Redox Flow Batteries. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 7987–7999. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b02201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neira I.; García M. D.; Peinador C.; Kaifer A. E. Terminal Carboxylate Effects on the Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Cucurbit[7]uril Binding to Guests Containing a Central Bis(Pyridinium)-Xylylene Site. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 2325–2329. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See the Supporting Information.

- Ramalingam V.; Urbach A. R. Cucurbit[8]uril Rotaxanes. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4898–4901. 10.1021/ol201991e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidro-Llobet A.; Álvarez M.; Albericio F. Amino Acid-Protecting Groups. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2455–2504. 10.1021/cr800323s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thieriet N.; Alsina J.; Giralt E.; Guibe F.; Albericio F. Use of Alloc-amino acids in solid-phase peptide synthesis. Tandem deprotection-coupling reactions using neutral conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7275–7278. 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01690-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Mart R. J.; Osborne R. D.; Stevens M. M.; Ulijn R. V. Peptide-based stimuli-responsive biomaterials. Soft Matter 2006, 2, 822–835. 10.1039/b607706d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lowik D. W. P. M.; Leunissen E. H. P.; van den Heuvel M.; Hansen M. B.; van Hest J. C. M. Stimulus Responsive Peptide Based Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3394–3412. 10.1039/b914342b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Shah A.; Malik M. S.; Khan G. S.; Nosheen E.; Iftikhar F. J.; Khan F. A.; Shukla S. S.; Akhter M. S.; Kraatz H. B.; Aminabhavi T. M. Stimuli-Responsive Peptide-Based Biomaterials as Drug Delivery Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 353, 559–583. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.07.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C.; Huang Z.; Fang Y.; Liu J. Construction of protein assemblies by host-guest interactions with cucurbiturils. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 4272–4281. 10.1039/C7OB00686A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.