Abstract

Simple Summary

The diagnostic and therapeutic pathway of vulvar cancer impacts severely on the psychosocial and psychosexual equilibrium of women affected by it. The current literature shows the presence of depressive and anxious symptoms in association with physical, psychological and behavioural alterations in sexuality as well as deterioration of partner relationship. The aim of this article is to highlight the difficulties and challenges faced by women diagnosed and treated for vulvar cancer to provide early recognition and appropriate assistance. By implementing an integrated care model, it should be possible to detect unmet needs and improve the quality of life of these women.

Abstract

Women who are diagnosed and treated for vulvar cancer are at higher risk of psychological distress, sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction with partner relationships. The aim of this article is to provide a review of the psychological, relational and sexual issues experienced by women with vulvar cancer in order to highlight the importance of this issue and improve the quality of care offered to these patients. A review of the literature was performed using PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library. The results are presented as a narrative synthesis and highlight the massive impact of vulvar cancer: depressive and anxiety symptoms were more frequent in these women, and vulvar cancer may have a negative effect on sexuality from a physical, psychological and behavioural point of view. Factors that may negatively affect these women’s lives are shame, insecurity or difficulties in self-care and daily activities. This review highlights the psychosocial and psychosexual issues faced by women diagnosed and treated for vulvar cancer, although more studies are needed to better investigate this field of interest and to identify strategies to relieve their psychological distress. Care providers should implement an integrated care model to help women with vulvar cancer recognise and address their unmet needs.

Keywords: vulvar cancer, anxiety, depression, distress, sexual functioning, quality of life

1. Introduction

Vulvar cancer is a rare malignancy with an incidence of 2.5–4.4 per 100,000 persons per year, making it the fourth most common gynaecological malignancy in Europe [1]. The most common type is vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC), followed by basal cell carcinoma, extramammary Paget’s disease and vulvar melanoma. The median age at diagnosis is 69 years [2]. Risk factors for the development of VSCC include increasing age, human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, immunodeficiency, smoking and vulvar inflammatory conditions [3]. Notably, in recent decades, the incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), the precursor to VSCC, has doubled for all age groups, increasing the most for patients under the age of 50 [4].

VSCC has two precursor forms: (1) vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) HPV-related (i.e. vulvar high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, VHSIL) and (2) HPV-unrelated, also known as differentiated VIN (dVIN), typically related to chronic vulvar inflammatory conditions (e.g., lichen sclerosus or lichen planus). These two different biological entities also have a differing epidemiology, characteristics, and prognosis [5,6,7,8]. The diagnosis of vulvar cancer is often delayed, as there is not adequate awareness among women: the majority of women feel embarrassed to ask their physicians about vulvar health and vulvar symptoms [9]. VSCC is often asymptomatic for a long period of time, or it can present with pruritus, irritation, or pain. Late-presenting symptoms include bleeding, pain, vaginal discharge, and urinary- or bowel-related symptoms. Clinically, VSCC can present as an erythematous patch, plaque, ulcer, or mass.

Staging is based on a vulvar biopsy to determine stromal invasion, which represents an important prognostic factor, then a clinical assessment of tumour size, groin lymph nodes and eventual distant metastases [10]. The treatment of stage I disease is surgical excision with adjuvant radiation (RT) in cases with high-risk factors. Stages II–IVA vulvar cancer, locally advanced disease, is usually treated with radical surgery and adjuvant chemoradiation. In selected cases, neoadjuvant chemoradiation can be used to reduce tumour size to facilitate surgical resection in an attempt to avoid a pelvic exenteration. For stage IVB, palliation with chemotherapy (CT) and/or RT is recommended [10].

The various surgical options have different impacts on the quality of life of the patients. A wide local excision is a simple excision of a vulvar tumour, a procedure reserved for preinvasive disease and stage IA vulvar cancers; this is the most conservative vulvar surgery in cases of malignancy. A modified radical vulvectomy combines the excision of the primary tumour and bilateral groin dissection [11]. On incision at the primary vulvar tumour site, the surgeon should try to spare the vital organs (e.g., urethra, clitoris and anal sphincter) [12]. Reconstructive surgery may be needed during this procedure [13]. Wound dehiscence and infection are common after radical vulvectomy. The most radical surgery is total pelvic exenteration, which is reserved exclusively for carefully selected patients with malignancy extended to other organs (e.g., urethra, anus and vagina). Despite its large impact on the patient’s quality of life, pelvic exenteration can be a potentially curative option. Surgical morbidity is high and includes infections, wound dehiscence, and urinary- and gastrointestinal-related complications. Inguinofemoral lymph node dissection is indicated when stromal invasion is >1 mm, and it is burdened with many postoperative complications including a significantly increased risk of lymphedema and wound breakdown [14]. For this reason, sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered in pT1 vulvar cancers [15].

Although vulvar surgery and treatment has become more targeted and less radical over the decades, it may still cause scarring and mutilation of the external genitalia, and it also may affect various nerves and blood vessels involved in sexual, anal and/or urinary functions [16]. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vulvar cancer or VIN are at high risk of psychological distress, sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction with partner relationships [17]. Factors associated with post-treatment sexual dysfunction include history of depression or anxiety, patient’s increased age and the excision size of the vulvar cancer. Interest in the QoL of women with vulvar cancer has increased in recent years [18,19,20]. Most studies on QoL after vulvectomy are, however, focused on postoperative complications and long-term side effects [21,22,23], whereas the impact that surgery may have on sexual health and on a patient’s relationships have not been properly investigated. Despite the first paper on post-surgical sexual function following vulvar cancer being published almost 40 years ago [24], the true impact of the different types of vulvectomies on the sexual health of vulvar cancer survivors has been poorly investigated.

The aim of this literature review is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the psychological, relational and sexual issues experienced by women with vulvar cancer in order to inform both researchers and clinicians of the steps needed to advance knowledge in this area and to improve the quality of care offered to these patients.

2. Material and Methods

The search was conducted in the following databases on 14 July 2021: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and the Cochrane Library. Keywords included: vulvar malignancy, vulvar neoplasms, vulvar cancer, vulva *, vulvectomy, gynaecologic *, gynecologic *, cancer *, tumor *, cancer survivors/psychology, psychological adaptation, quality of life, psychological distress, stress, anxiety, depression, sexuality, sexual dysfunction, partner and sexual partner. Primary research studies that investigated psychological, psychosocial and/or sexual consequences of vulvar cancer in adult women were included with no limitations related to publication date. Studies on gynaecological cancer not focusing specifically on vulvar malignancy were excluded. Only studies in the English language were included. The references of the identified studies and relevant reviews were manually searched to identify other relevant articles. The results of the evidence found are presented as a narrative synthesis.

3. Results

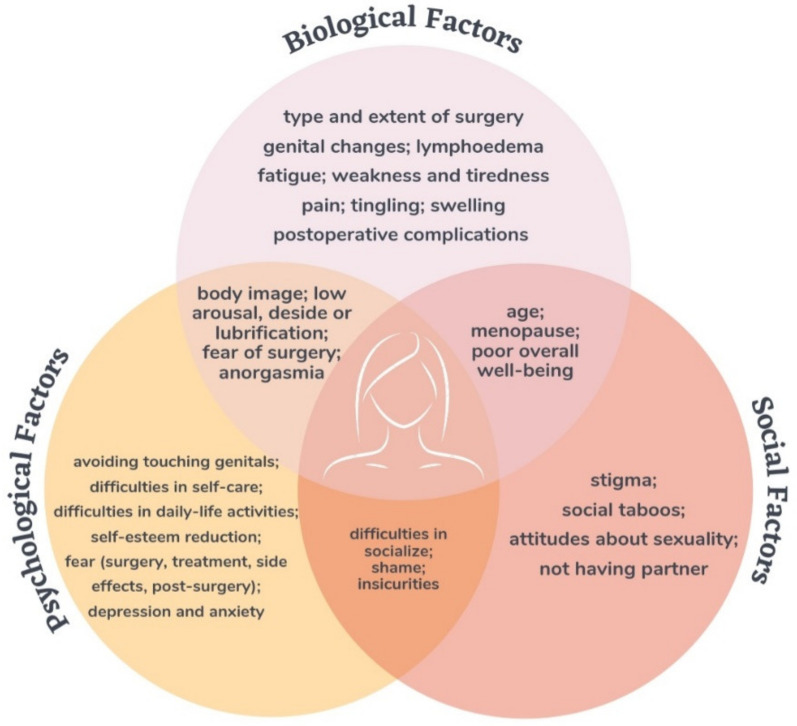

The initial search retrieved 1715 articles after duplicates removal. Of these, only 30 articles were considered eligible for inclusion in the review. The details of the included studies are described in Table 1, while a summary of the results is given in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the included studies.

| Category | Studies | Country | Mean Age | Type of Surgery | Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | Blbulyan et al., 2020 [25] | Russia | 56.3 | - | EORTC; FACT-G | Lower overall quality of life. Restrictions in physical activity, poorer social interaction and emotional sphere. Worse global health status. |

| de Melo Ferreira et al., 2012 [26] | Brazil | 66.9 | Vulvectomy + IFL | EORTC | ||

| Farrel et al., 2014 [27] | Australia | 63 | IFL | UBQC | ||

| Gane et al., 2018 [28] | Australia | 57 | Vulvectomy with or without SNB or IFL | FACT-G | ||

| Günther et al., 2014 [29] | Germany | 63 WLE–59 RV | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | EORTC | ||

| Hellinga et al., 2018 [30] | Netherlands | 65.5 | WLE/radical vulvectomy/pelvic exenteration + reconstruction with lotus petal flap | EORTC | ||

| Janda et al., 2004 [18] | Australia | 68.8 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | ECOG-PSR; FACT-G | ||

| Jones et al., 2016 [31] | UK | 59.9 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | EORTC | ||

| Likes et al., 2007 [32] | USA | 47.5 | WLE | EORTC | ||

| Oonk et al., 2009 [20] | Netherlands | 69 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with SNB or IFL | EORTC | ||

| Novackova et al., 2012 [33] | Czech Republic | 66.5 CONS–73.8 RAD | WLE or radical vulvectomy with SNB or IFL | EORTC | ||

| Senn et al., 2013 [34] | Germany | 18 (VIN) 42 (K) | Laser vaporisation/WLE/vulvectomy/radical vulvectomy/exenteration with or without SNB or IFL | WOMAN-PRO | ||

| Weijmar Schultz et al., 1990 [35] | Netherlands | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Trott et al., 2020 [36] | Germany | 63 | Unspecified vulvar surgery with or without SNB or IFL with or without reconstruction | EORTC | ||

| Partner relationship |

Aerts et al., 2014 [37] | Belgium | 57.4 | Vulvectomy with or without SNB | DAS | Lower quality of partner relationship, marital satisfaction and dyadic cohesion. |

| Barlow et al., 2014 [38] | Australia | 58 | Radical partial or total vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Sexual Functioning |

Aerts et al., 2014 [37] | Belgium | 57.4 | Vulvectomy with or without SNB | SFSS; SSPQ | Worse sexual functioning. Disruption and reduction in sexual activity. |

| Andersen et al., 1983 [24] | USA | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy | SCL-90 | ||

| Andersen et al., 1988 [39] | USA | 50.3 | Laser vaporisation/WLE/vulvectomy | DSFI; SAI | ||

| Andreasson et al., 1986 [40] | Denmark | 45.8 | Vulvectomy | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Barlow et al., 2014 [38] | Australia | 58 | Radical partial or total vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Blbulyan et al., 2020 [25] | Russia | 56.3 | - | FSFI | ||

| Farrel et al., 2014 [27] | Australia | 63 | IFL | clinical information | ||

| Green et al., 2000 [41] | USA | 60 | Vulvectomy with or without IFL | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Grimm et al., 2016 [42] | Germany | 51.5 | Laser vaporisation/WLE/radical vulvectomy | FSFI | ||

| Hazewinkel et al., 2012 [43] | Netherlands | 68 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without SNB or IFL | FSFI; BIS | ||

| Hellinga et al., 2018 [30] | Netherlands | 65.5 | WLE/radical vulvectomy/pelvic exenteration + reconstruction with lotus petal flap | FSFI; BIS | ||

| Jones et al., 2016 [31] | UK | 59.9 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Weijmar Schultz et al., 1990 [35] | Netherlands | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Likes et al., 2007 [32] | USA | 47.5 | WLE | FSFI | ||

| Psychological health | Aerts et al., 2014 [37] | Belgium | 57.4 | Vulvectomy with or without sentinel node dissection | BDI | Presence of depressive and anxious symptoms, worsened by altered body image and sexual difficulties. Impact on general well-being, quality of life, and relationship with partner and families. |

| Avery et al., 1974 [44] | USA | NA | Vulvectomy | clinical information | ||

| Andersen et al., 1983 [24] | USA | 55 | WLE or radical vulvectomy | BDI | ||

| Andreasson et al., 1986 [40] | Denmark | 45.8 | Vulvectomy | ad hoc questionnaire | ||

| Corney et al., 1992 [45] | UK | 71% >65 | Radical vulvectomy, Wertheim’s hysterectomy or pelvic exenteration | HADS; clinical interview | ||

| Green et al., 2000 [41] | USA | 60 | Vulvectomy with or without IFL | PRIME-MD | ||

| Janda et al., 2004 [18] | Australia | 68.8 | WLE or radical vulvectomy with or without IFL | FACT-G; HADS | ||

| Jefferies and Clifford, 2012 [46] | UK | >50 | - | clinical interview | ||

| McGrath et al., 2013 [47] | Australia | NA | - | clinical interview | ||

| Senn et al., 2011 [48] | Germany | 55 | Laser vaporisation/WLE/radical vulvectomy with or without SNB or IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Senn et al., 2013 [34] | Germany | 18 (VIN) 42 (K) | Laser vaporisation/WLE/vulvectomy/radical vulvectomy/exenteration with or without SNB or IFL | WOMAN-PRO | ||

| Stellman et al., 1984 [49] | USA | 53.4 | Vulvectomy or radical vulvectomy | SQ | ||

| Tamburini et al., 1986 [19] | Italy | 51.7 | Vulvectomy with or without IFL | clinical interview | ||

| Thuesen et al., 1992 [50] | Denmark | 41.4 | WLE | clinical interview; ad hoc questionnaire |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; BIS = Body Image Scale; ECOG-PSR = ECOG Scale of Performance Status; CONS = sentinel lymph node biopsy; DAS = Dyadic Adjustment Scale; DSFI = Derogates Sexual Functioning Inventory; EORTC = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; FACT-G = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General; FSFI = Female Sexuality Index; GSI = Global Severity Index; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IFL = inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy; NA = not available; PRIME-MD = Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders; RAD = inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy; RV = radial vulvectomy; SAI = Sexual Arousability Index; SCL-90 = Symptoms Checklist-90; SFSS = Short Sexual Functioning Scale; SNB = sentinel node biopsy; SSPQ = Specific Sexual Problems Questionnaire; SQ = Kellner Symptom Questionnaire; UBQC = Utility-Based Questionnaire-Cancer; WLE = wide local excision.

Figure 1.

Summary of the results. This figure shows the main bio–psycho–social factors that impact the psychosocial and sexual well-being of women with vulvar cancer.

3.1. Psychological Impact

Vulvar cancer is a rare condition. Due to the lack of studies regarding the impact of the disease, little is known about the specific emotional, social and psychological impacts on these patients. Diagnosis and treatment, primarily consisting of surgery ranging from local excision to radical vulvectomy and clitoris removal, may have a significant negative psychological effect on these women. Symptoms may range from anxiety and sexual dysfunction to major depressive disorders. Depending on the extent of surgery, participants’ self-perception of being a woman has been reported to be influenced in at least four dimensions: the appearance of post-surgical female genitals, sexuality, attractiveness and self-confidence [48].

The need for emotional support from the preoperative phase to follow-up care has already been recognised by Avery et al. in 1974 [44]. The first systematic review was carried out by Jefferies and Clifford [51], who examined the psychological, physical and sexual consequences for women following diagnosis and treatment for cancer of the vulva. Eight out of the 14 studies analysed reported psychological changes as a result of the diagnosis and surgery for vulvar cancer [19,24,39,40,41,45,49,50]. Only a few of these authors used validated measurement tools to record levels of depression and anxiety [18,24,37,41,45,49].

In terms of psychological distress and/or depression, in the study by Andersen [24], women affected by vulvar cancer experienced substantial and significant levels of distress in comparison to healthy women. Nearly 50% of the patients interviewed by Andreasson et al. [40] had an altered sense of their body image, describing feelings of “not being the same woman”. This finding was later supported by Andreasson et al. [40], Stellman et al. [49], and Thuesen et al. [50].

Stellman and colleagues [49] reported that four out of nine women were unable to name the anatomic area surgically removed. This may have increased the women’s feelings of isolation and embarrassment. The study also reported that six out of nine women were depressed and anxious. Loss of self-confidence and self-esteem, also associated with depression, were noted.

The study by Tamburini et al. [19] revealed that 72% of the sample showed symptoms on the hypochondria scale, 63% on the depression scale, 63% on the hysteria scale and 18% on the psychotic scale (paranoia, schizophrenia). These results, both for “neurotic” (hypochondria, hysteria and depression) and, to a lesser extent, the “psychotic” scales (paranoia, schizophrenia) tended to be more pathological than in patients undergoing the same radical surgery for carcinoma of the uterine cervix. This may be explained by the feeling of awkwardness or loss of self-esteem resulting from external genital mutilation and by severe sexual difficulties.

In a retrospective study by Corney et al. [45], women who underwent major gynaecological surgery (vulvectomy, hysterectomy and pelvic exenteration) for carcinoma of the cervix and vulva were interviewed to evaluate postoperative psychosocial and psychosexual problems, revealing that 21% of the women suffered from anxiety and 14% from depression.The study also tried to assess the relationship between the level of distress and the different clinical phases, finding that the period of highest distress or worry usually coincided with the period of most uncertainty. For 39% of women, the most distressing time was between the first medical indication of clinical problems and the diagnosis of cancer, and an additional 37% felt that it was the period between diagnosis and the operation. Moreover, this study showed that the presence of sexual problems was significantly associated with the women’s level of anxiety. However, it was difficult to ascertain whether the sexual problems were making the women more anxious or whether their anxiety was affecting their sexual behaviour, cognition or emotions.

Green [41] detected symptoms of depression in 31% of women treated with vulvar surgery, but only 14% were taking antidepressant medication. Women with higher depression scores had greater sexual aversion disorder and experienced higher levels of body image disturbance and global sexual dysfunction. Janda et al. [52] showed that 21.8% of patients in the sample were affected by severe anxiety and 6.3% by depression.

The study by Senn et al. [48] focused on the symptoms of women during the first 6 months following surgical treatment for vulvar neoplasia. Using narrative interviews, the study showed eight interrelated psychological themes: delayed diagnosis, disclosed disease, disturbed self-image, changed vulva care, experienced wound-related symptoms, evoked emotions, affected interpersonal interactions and feared illness progression. The unknown diagnosis, surgery, location, changed female genitals and experienced symptoms evoked feelings of embarrassment, uncertainty, fear, sadness and tiredness. Senn et al. [34] tried to measure these symptoms with the WOMAN-PRO instrument, developed by them in 2013. The results showed that the three most prevalent psychosocial symptoms/issues were “tiredness” (95.4%), “insecurity” (83.1%) and “feeling that my body has changed” (76.9%). Despite physical symptoms occurring more frequently, in this sample they were less distressing than difficulties in daily life and psychosocial symptoms/issues.

Through a phenomenological study, Jefferies and Clifford [46] gave a voice to women regarding the stories of their illness, their feelings and their thoughts about diagnosis and treatment for cancer of the vulva. This study was an overview of their lived experience described using the concept of invisibility in the context of four existential dimensions: body, relationship, space and time.

The findings of the study by McGrath et al. [47] demonstrated that the challenges in relation to the diagnosis and treatment of vulvar cancer are exacerbated by concerns about privacy, shame and fear. Because of the private nature of the disease, the women from the sample tended to keep the condition a secret once diagnosed; the feeling of shame was as powerful as the sense of privacy. These feelings were so strong that even when a woman died of this cancer, the type of cancer was not revealed to avoid shame. Lastly, it was common for the women to feel scared and worried about the cancer, especially when first diagnosed.

In the study by Aerts et al. [37], women with a diagnosis of vulvar malignancy were compared to healthy controls. When compared with the situation before surgery, no significant differences in depressive symptoms, general well-being and quality of partner relationship were found after surgery. However, in comparison with healthy controls, women with vulvar malignancy reported significantly lower levels of psychological functioning both before and after treatment.

Finally, the review of the literature by Boden et al. [53] highlighted important psychosocial issues that women diagnosed and living with cancer of the vulva have to face. Challenges include social stigma surrounding the vulva and the diagnosis of vulvar cancer, feeling unprepared both physically and psychologically and a lack of information and support.

The literature, although poor, shows the massive impact of vulvar cancer, both in psychological and social dimensions. Through different means of investigation, the presence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in women has been demonstrated in every phase, from diagnosis to postoperative follow up. Moreover, the altered body image due to the surgical treatment and the presence of sexual difficulties can lead to deterioration in the emotional state. All of these elements can influence the women’s general well-being, quality of life and their relationship with partners and families.

In conclusion, the review of the literature reveals the paucity of current studies regarding women who are suffering from cancer of the vulva today. Clearly there is a need for more research into the special needs of this small group of women.

3.2. Quality of Life, Sexuality and Partner Relationship

Several studies [18,27,28,31,32,33,36] reported an overall worsening of quality of life. Three studies [25,29,30] explored this aspect further, noting that the worsening of quality of life was related to a decrease in physical and cognitive functioning, social interactions and an increase in physical and emotional symptoms. The study by de Melo Ferreira and colleagues [26], going into more detail, found a negative correlation between quality of life and the severity of lymphoedema of the lower extremities.

Only two studies investigated partner relationships [37,38]. Aerts and colleagues [37] observed that poorer quality of partner relationship, marital satisfaction and dyadic cohesion were more common in women with preoperative vulvar malignancy. Dissatisfaction with partner life was also maintained at 6 months and 1 year after the operation. In this respect, Barlow and colleagues [38] found that conservative surgery led to no negative impact on couples’ relationships.

Sexual functioning in this disease has been investigated but most frequently from a physiological perspective. However, some studies have intersected biological function with more psychosocial components. Aerts and colleagues [37] found that there is a correlation between psychosocial well-being and sexual dysfunction in patients with vulvar cancer. In general, it seems that vulvar cancer has a negative effect on sexuality not only from a physical point of view, for example, due to the fact of presenting with anorgasmia, difficulty in lubrication or pain, but also from a psychological and behavioural point of view, e.g., due to the fact of reporting reduced desire, reduced satisfaction, reduced sexual activity, fear of penetration or avoidance behaviour [24,25,27,30,31,32,35,38,40,41,43]. Of interest are the results presented in the study by Andersen and colleagues [24], which showed that while there was a deterioration in sexual functioning from a physiological point of view, there was little negative impact on sexual life. However, there was a reluctance to enter into relationships with new partners for those who did not have any before the illness.

Related Bio–Psycho–Social Factors

Several factors are responsible for the deterioration of quality of life, sexual functioning and partner relationships. In general, studies have considered the various factors, often incorporating the collection of these data into clinical interviews or using generic, albeit validated, assessment instruments. Although pre-existing problems have been shown to play an important role [32,33,36], several studies have reported that treatments and surgeries are crucial to patients’ physical, mental and social health. Three studies [24,41,42] pointed out that outcomes seem to be correlated with the magnitude of surgical intervention. Aerts and colleagues and Likes and colleagues [32,37] found a negative correlation between quality of life and the excision size of the vulvar malignancy, meanwhile Gunther et al. [29], Barlow et al. [38] and Hazewinkel et al. [43] identified radical vulvectomy and clitoral removal as determinants of worsening quality of life, sexual functioning and partner life. Inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy also appears to negatively impact the lives of vulvar cancer patients as was found by Novackova and colleagues [33].

Some authors have observed that in connection with surgery, important impacting factors are fear of possible removal of their clitoris and fear of pain on resumption of sexual intercourse [38]. In general, it seems that aesthetic and functional changes of the genitals [39] and having undergone multiple vulvar procedures [38] have a significantly negative impact on well-being during the postoperative period. The postoperative period itself is not without risk due to the possibility of incurring postoperative wound-healing complications [36] that not only slow down the healing process but also hinder the recovery of normal biological, social and psychological functions. Factors associated with post-treatment sexual dysfunction include older age, poor overall well-being and history of depression and anxiety [37,42].

Regarding therapies, two studies found that radiotherapy or adjuvant inguinal radiotherapy [33,43] have a negative impact on patients’ lives, mainly due to the associated side effects. The most impactful side effect seems to be lymphoedema, considered globally [20,29,31,33,38] or specifically of the lower extremities [18,26]. Lymphoedema causes patients pain, changes in sleep, fatigue, reduced movement amplitude and financial costs [26]. It is a tiring and energy-reducing condition, as it requires constant attention in terms of wearing compression stockings, performing massages and undergoing other treatments. It can reduce a patient’s ability to work, perform household duties and socialise as well as negatively affecting the patients’ body image and self-esteem [18]. Other side effects that affect patients’ lives are pain [28,29,30,31] and leg pain [27], persistent swelling of the lower limbs or vulva and/or pelvic/abdominal region [28], tingling [28] and fatigue [31,33].

From a psychological and behavioural point of view, factors such as body image disruption [24,34,38,41], feelings of weakness and fatigue [28,31,34] and avoidance behaviours regarding sexual intercourse and touching the genital area [38] seem to be decisive in worsening quality of life, quality of relationships and sexuality.

In addition to the psychological aspects of vulvar cancer, social, cultural and interpersonal aspects negatively affect patients’ quality of life, sexuality and relationship with their partners. Studies have shown that age can modulate a person’s response to the disease and treatment. On the one hand, younger women show more distress because of the greater proximity to the onset of menopause [24] and the impediments in the activities of daily living: the younger the patients are, the more they feel they should and would like to have more active lives with a greater number of relationships and a more active sex life [34]. On the other hand, it has been observed that with advancing age, patients experience greater suffering related to difficulties in investing in new romantic relationships and taking care of themselves [32,33,36]. Older patients also have prevalent attitudes about sexuality in later life such as those indicating that such activity is inappropriate, unimportant or readily expendable [24]. More generally, factors that negatively impact the lives of women with vulvar cancer are shame or insecurity [33,34], difficulties in self-care [48] and in daily activities such as homecare [34] and not having a sexual partner [33]. Stigma and social taboos also seem to play a key role [48].

4. Discussion

Despite covering a large time span—from the 1983 study by Andersen and colleagues to the 2020 study by Blbulyan et al.—the impact of vulvar cancer on mental health, quality of life, sexuality and relationships has been little investigated. The aim of this narrative review was to update the knowledge on these themes and suggest future directions for clinical practice and research.

Regarding quality of life, studies have often focused on well-being in general or global health; however, specific aspects of quality of life, emotional regulation and the ability and willingness to take care of oneself would also be of interest. Vulvar cancer seems to also have a role in worsening sexual functioning with a disruption and reduction in sexual activity. Similarly, the included studies observed lower quality of partner relationships, marital satisfaction and dyadic cohesion.

Regarding mental health issues, depressive and anxiety symptoms were prevalent among women affected by vulvar neoplasia at every step of the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway. Different factors can contribute to the onset of these symptoms. Psychological distress may be related to the altered body image due to the aftermath of the surgery. The results of the studies, although scarce, demonstrate that women may experience feelings of shame and embarrassment related to strong social stigma, which may lead to feelings of isolation and a loss of self-esteem. Moreover, sexual dysfunction is strongly associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms, which are often clinically significant, with a mutual influence.

Depression and cancer risk seem to be linked by a mutual relationship. The experience of receiving a cancer diagnosis can be a significant source of distress, with the onset of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms that can lead to sleep disturbance which may, in turn, increase the risk of depression. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common among cancer patients with prevalence rates up to four-times higher than the general population [54]. Conversely, depression confers worse outcomes in oncological settings including non-adherence to treatment and increased mortality [55]. According to a study by Wang et al. [56], the estimated absolute risk increases (ARIs) associated with depression and anxiety are 34.3 events/100,000 person years for cancer incidence and 28.2 events/100,000 person years for cancer-specific mortality. Several mechanisms could explain this reciprocal influence [56]. Psychosocial stressors in cancer promote inflammation and oxidative/nitrosative stress, with alterations in cytokine secretion and regulation (TNF-a or Il-6) [57]; decreased immunosurveillance; dysfunctional activation of the autonomic nervous system and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. Given the high prevalence of depression and anxiety in the general population, particularly among cancer patients, and in consideration of the bidirectional link between the neuroendocrine and immune systems, the screening and intervention of underlying depressive and anxiety symptoms has significant repercussions both on clinical practice and public health regarding cancer prevention and treatment.

The studies included in this review have several limitations. First, most of the studies use non-validated tools such as clinical interviews or data taken from medical records. While these have made it possible to obtain qualitative insight into patients’ experiences, there is less scope for distinguishing between areas and isolating the factors that impact on them. Sexual function has often been addressed on a physiological level via the maintenance of sexual activity or physical dysfunction (e.g., orgasm, pain on penetration and lubrication). Sexual satisfaction cannot be reduced simply to the extent of physical impairment, the presence of symptoms or the ability to perform a sexual task considered normal [35]. The fact that sex life is scarcely investigated from a psychological point of view may be due not only to the limitations of the studies but also to social and cultural issues surrounding the perception of the possibility for women to desire an active and satisfying sex life after the age of 50. A healthy sex life has been shown to play a key role in maintaining mental and physical health.

4.1. Implications for Future Research

Future studies with better methodological quality are needed to obtain more reliable data. In particular, controlled studies are needed. Given the high survival rate of vulvar cancer patients [58], quality of life, sexuality and psychological well-being are key areas for investigation, along with the long-term consequences of the disease and treatment pathways. These areas are crucial not only due to the high prevalence of psychological distress among cancer patient but also due to the consequences of such disorders on overall health [59]. In fact, considering breast cancer, a much more widespread, well-known and well-studied type of cancer among women, a large volume of literature is available on quality of life [60], sexuality [61,62] and partner relationships [63,64]. Furthermore, future studies should investigate the psychological aspects of sexual experience, shame, body image, desire and avoidance of desire as well as considering the sexual orientation of patients and the specific needs related to it that may emerge. It would also be useful to consider sexuality as a subjective, personal and individual dimension and not only within the context of the couple. Regarding the relationship with a partner, it would be interesting in the future to investigate not only the level of satisfaction and sexual activity but also other factors such as attachment.

With regard to the impact of different medical treatments, the approach to vulvar cancer has changed considerably over time, with a succession of different surgical procedures and pharmacological treatments. In light of this, it would be interesting to assess how different types of intervention may have different impacts on psychological, social and sexual outcomes. Future studies could compare different treatment pathways to explore this further.

4.2. Implications for Clinical Practice

The impacts of vulvar cancer on psychosocial- and sexuality-related areas highlight the importance of implementing effective strategies in both primary and secondary prevention. The ideal goal should be early recognition and appropriate treatment of the elements of psychosexual and psychosocial distress. These approaches should lead to an improvement in general well-being, a healthier sex life and more stable and supportive relationships.

Firstly, healthcare professionals should be adequately trained to help women to understand the basics of female external genital anatomy, so that they can learn the difference between physiological and pathological features. Very few women engage in vulvar self-examination, and few women who identify abnormalities seek appropriate medical care. Vulvar self-examination may allow women to have a healthier relationship with their genitals, overcoming the obstacles due to the feelings of shame, judgment and embarrassment. In fact, this is an easy procedure that takes only a few minutes and could change the clinical course of some pathologies and, in some cases, could save lives [9].

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has recognised psychological distress as the sixth vital sign in cancer care [65]. For this reason, it may be useful to facilitate its early detection using screening tests in a very early phase of the diagnostic and therapeutic pathways. This kind of test should be approved and validated so that it can determine clinical risk categories and assign the most effective interventional treatment. The importance of the role of psycho-oncologists in the treatment of vulvar cancer should be emphasised for proposing and offering psychological support and psychoeducational interventions. These kinds of interventions could be useful not only for sustaining women’s sexual health [66] and their emotional condition but also for supporting the familial network. Moreover, evaluation by a psychiatric specialist may be useful in order to provide possible psychopharmacological therapy in the presence of severe depressive–anxiety symptoms, analysing the risk factors and any pharmacological interactions with chemotherapy treatments. This may be useful in improving the detection and treatment of psychosexual and psychosocial distress. The ideal goal could be the integration of a psycho-oncologist and/or psychiatrist in the multidisciplinary team for the treatment of vulvar cancer with the aim of addressing both the physical and psychosocial needs of these women [67].

5. Conclusions

This review highlights the psychosocial and psychosexual issues faced by women diagnosed with and treated for vulvar cancer. Many questions regarding the detection and management of psychological distress, sexual dysfunction and relational problems remain open, mainly due to the limited research into this area and the scarce integration of psycho-oncological knowledge in routine care. Care providers should implement an integrated care model to help women with vulvar cancer to recognise and address their still unmet needs, working within a bio–psycho–social framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.C., F.M., M.M. and F.B.; data collection, F.M., M.M. and N.G.; interpretation of data, all authors; writing—original draft preparation, F.M., M.M., F.B. and S.C.; figure preparation, F.M.; writing—review and editing, all the authors; supervision, S.C., L.O. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted with no specific funding support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019 69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. About the SEER Program. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];2014 Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/about/

- 3.Stroup A., Harlan L., Trimble E. Demographic, clinical, and treatment trends among women diagnosed with vulvar cancer in the United States. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2008 108:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.11.011. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825807009195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joura E.A., Lösch A., Haider-Angeler M.G., Breitenecker G., Leodolter S. Trends in vulvar neoplasia. Increasing incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva in young women. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Reprod. Med. 2000 45:613–615. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10986677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Avoort I.A.M., Shirango H., Hoevenaars B.M., Grefte J.M.M., de Hullu J.A., de Wilde P.C.M., Bulten J., Melchers W., Massuger L.F.A.G. Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma is a Multifactorial Disease Following Two Separate and Independent Pathways. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2006 25:22–29. doi: 10.1097/01.pgp.0000177646.38266.6a. Available online: http://journals.lww.com/00004347-200601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Nieuwenhof H.P., van Kempen L.C., de Hullu J.A., Bekkers R.L., Bulten J., Melchers W.J., Massuger L.F. The Etiologic Role of HPV in Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma Fine Tuned. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009 18:2061–2067. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0209. Available online: http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Handisurya A., Schellenbacher C., Kirnbauer R. Diseases caused by human papillomaviruses (HPV) [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2009 7:453–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.06988.x. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.06988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bornstein J., Bogliatto F., Haefner H.K., Stockdale C.K., Preti M., Bohl T.G., Reutter J., ISSVD Terminology Committee The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Terminology of Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2016 20:11–14. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000169. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00128360-201601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preti M., Selk A., Stockdale C., Bevilacqua F., Vieira-Baptista P., Borella F., Gallio N., Cosma S., Melo C., Micheletti L., et al. Knowledge of Vulvar Anatomy and Self-examination in a Sample of Italian Women. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2021 25:166–171. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000585. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger T.H., Hakim A.A., Lee S.J., Wakabayashi M.T., Morgan R.J., Han E.S. Surgical Management of Vulvar Cancer. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2016 15:121–128. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0009. Available online: https://jnccn.org/doi/10.6004/jnccn.2017.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiSaia P.J., Creasman W.T., Rich W.M. An alternate approach to early cancer of the vulva. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1979 133:825–832. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90119-4. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0002937879901194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaps J.M., Fu Y.S., Montz F.J., Hacker N.F., Berek J.S. Surgical-pathologic variables predictive of local recurrence in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 1990 38:309–314. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90064-R. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/009082589090064R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Höckel M., Dornhöfer N. Vulvovaginal reconstruction for neoplastic disease. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Lancet Oncol. 2008 9:559–568. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70147-5. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470204508701475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stehman F.B., Bundy B.N., Ball H., Clarke-Pearson D.L. Sites of failure and times to failure in carcinoma of the vulva treated conservatively: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996 174:1128–1133. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70654-3. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002937896706543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Covens A., Vella E.T., Kennedy E.B., Reade C.J., Jimenez W., Le T. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in vulvar cancer: Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline recommendations. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2015 137:351–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.02.014. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S009082581500654X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Doorn H.C., Ansink A., Verhaar-Langereis M.M., Stalpers L.L. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation for advanced primary vulvar cancer. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006 :CD003752. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003752.pub2. Available online: https://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD003752.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aerts L., Enzlin P., Vergote I., Verhaeghe J., Poppe W., Amant F. Sexual, Psychological, and Relational Functioning in Women after Surgical Treatment for Vulvar Malignancy: A Literature Review. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Sex. Med. 2012 9:361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02520.x. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1743609515338522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janda M., Obermair A., Cella D., Crandon A.J., Trimmel M. Vulvar cancer patients’ quality of life: A qualitative assessment. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2004 14:875–881. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-00009577-200409000-00021. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.14524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamburini M., Filiberti A., Ventafridda V., de Palo G. Quality of Life and Psychological State after Radical Vulvectomy. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 1986 5:263–269. doi: 10.3109/01674828609016766. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/01674828609016766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oonk M., van Os M., de Bock G., de Hullu J., Ansink A., van der Zee A. A comparison of quality of life between vulvar cancer patients after sentinel lymph node procedure only and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2009 113:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.006. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825808010561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayhan A., Tuncer Z.S., Akarin R., Yücel I., Develioǧlu O., Mercan R., Zeyneloǧlu H. Complications of radical vulvectomy and inguinal lymphadenectomy for the treatment of carcinoma of the vulva. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Surg. Oncol. 1992 51:243–245. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930510408. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1434654/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balat O., Edwards C., Delclos L. Complications following combined surgery (radical vulvectomy versus wide local excision) and radiotherapy for the treatment of carcinoma of the vulva: Report of 73 patients. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2000 21:501–503. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11198043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaarenstroom K.N., Kenter G.G., Trimbos J.B., Agous I., Amant F., Peters A.A.W., Vergote I. Postoperative complications after vulvectomy and inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy using separate groin incisions. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2003 13:522–527. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-00009577-200307000-00019. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen B.L., Hacker N.F. Psychosexual adjustment after vulvar surgery. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Obstet. Gynecol. 1983 62:457–462. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6888823. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blbulyan T.A., Solopova A.G., Ivanov A.E., Kurkina E.I. Effect of postoperative rehabilitation on quality of life in patients with vulvar cancer. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. 2020 14:415–425. doi: 10.17749/2313-7347/ob.gyn.rep.2020.156. Available online: https://www.gynecology.su/jour/article/view/790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreira A.P.D.M., de Figueiredo E.M., Lima R.A., Cândido E.B., Monteiro M.V.D.C., Franco T.M.R.D.F., Traiman P., da Silva-Filho A.L. Quality of life in women with vulvar cancer submitted to surgical treatment: A comparative study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012 165:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.06.027. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301211512002941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrell R., Gebski V., Hacker N.F. Quality of Life After Complete Lymphadenectomy for Vulvar Cancer: Do Women Prefer Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy? [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2014 24:813–819. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000101. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gane E.M., Steele M.L., Janda M., Ward L.C., Reul-Hirche H., Carter J., Quinn M., Obermair A., Hayes S.C. The Prevalence, Incidence, and Quality-of-Life Impact of Lymphedema After Treatment for Vulvar or Vaginal Cancer. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Rehabil. Oncol. 2018 36:48–55. doi: 10.1097/01.REO.0000000000000102. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/01893697-201801000-00008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Günther V., Malchow B., Schubert M., Andresen L., Jochens A., Jonat W., Mundhenke C., Alkatout I. Impact of radical operative treatment on the quality of life in women with vulvar cancer—A retrospective study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014 40:875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.027. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0748798314003941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hellinga J., Grootenhuis N.C.T., Werker P.M., de Bock G.H., van der Zee A.G., Oonk M.H., Stenekes M.W. Quality of Life and Sexual Functioning After Vulvar Reconstruction with the Lotus Petal Flap. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2018 28:1728–1736. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001340. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0000000000001340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones G.L., Jacques R.M., Thompson J., Wood H.J., Hughes J., Ledger W., Alazzam M., Radley S.C., Tidy J.A. The impact of surgery for vulval cancer upon health-related quality of life and pelvic floor outcomes during the first year of treatment: A longitudinal, mixed methods study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Psycho-Oncology. 2016 25:656–662. doi: 10.1002/pon.3992. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Likes W.M., Stegbauer C., Tillmanns T., Pruett J. Correlates of sexual function following vulvar excision. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2007 105:600–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.027. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825807000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novackova M., Halaska M.J., Robova H., Mala I., Pluta M., Chmel R., Rob L. A Prospective Study in Detection of Lower-Limb Lymphedema and Evaluation of Quality of Life After Vulvar Cancer Surgery. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2012 22:1081–1088. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31825866d0. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0b013e31825866d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senn B., Eicher M., Mueller M., Hornung R., Fink D., Baessler K., Hampl M., Denhaerynck K., Spirig R., Engberg S. A patient-reported outcome measure to identify occurrence and distress of post-surgery symptoms of WOMen with vulvAr Neoplasia (WOMAN-PRO)—A cross sectional study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2013 129:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.038. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S009082581200995X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weijmar Schultz W.C.M., van de Wiel H.B.M., Bouma J., Janssens J., Littlewood J. Psychosexual functioning after the treatment of cancer of the vulva: A longitudinal study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Cancer. 1990 66:402–407. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900715)66:2<402::AID-CNCR2820660234>3.0.CO;2-X. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1097-0142(19900715)66:2%3C402::AID-CNCR2820660234%3E3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trott S., Höckel M., Dornhöfer N., Geue K., Aktas B., Wolf B. Quality of life and associated factors after surgical treatment of vulvar cancer by vulvar field resection (VFR) [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020 302:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05584-5. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00404-020-05584-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aerts L., Enzlin P., Verhaeghe J., Vergote I., Amant F. Psychologic, Relational, and Sexual Functioning in Women After Surgical Treatment of Vulvar Malignancy: A Prospective Controlled Study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2014 24:372–380. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000035. Available online: https://ijgc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barlow E.L., Hacker N.F., Hussain R., Parmenter G. Sexuality and body image following treatment for early-stage vulvar cancer: A qualitative study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Adv. Nurs. 2014 70:1856–1866. doi: 10.1111/jan.12346. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jan.12346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersen B.L., Turnquist D., Lapolla J., Turner D. Sexual functioning after treatment of in situ vulvar cancer: Preliminary report. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Obstet. Gynecol. 1988 71:15–19. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3336539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andreasson B., Moth I., Jensen S.B., Bock J.E. Sexual Function and Somatopsychic Reactions in Vulvectomy-Operated Women and their Partners. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1986 65:7–10. doi: 10.3109/00016348609158221. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.3109/00016348609158221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green M.S., Naumann R., Elliot M., Hall J.B., Higgins R.V., Grigsby J.H. Sexual Dysfunction Following Vulvectomy. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2000 77:73–77. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5745. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825800957457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimm D., Eulenburg C., Brümmer O., Schliedermann A.-K., Trillsch F., Prieske K., Gieseking F., Selka E., Mahner S., Woelber L. Sexual activity and function after surgical treatment in patients with (pre)invasive vulvar lesions. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Support. Care Cancer. 2015 24:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2812-8. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00520-015-2812-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hazewinkel M.H., Laan E.T., Sprangers M.A., Fons G., Burger M.P., Roovers J.-P.W. Long-term sexual function in survivors of vulvar cancer: A cross-sectional study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2012 126:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.015. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825812002703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Avery W., Gardner C., Palmer S. Vulvectomy. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Am. J. Nurs. 1974 74:453–455. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4492906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corney R., Everett H., Howells A., Crowther M. Psychosocial adjustment following major gynaecological surgery for carcinoma of the cervix and vulva. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Psychosom. Res. 1992 36:561–568. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90041-Y. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/002239999290041Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jefferies H., Clifford C. Invisibility: The lived experience of women with cancer of the vulva. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Cancer Nurs. 2012 35:382–389. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31823335a1. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00002820-201209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGrath P., Rawson N. Key factors impacting on diagnosis and treatment for vulvar cancer for Indigenous women: Findings from Australia. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Support. Care Cancer. 2013 21:2769–2775. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1859-7. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00520-013-1859-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Senn B., Gafner D., Happ M., Eicher M., Mueller M., Engberg S., Spirig R. The unspoken disease: Symptom experience in women with vulval neoplasia and surgical treatment: A qualitative study. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Eur. J. Cancer Care. 2011 20:747–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01267.x. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stellman R.E., Goodwin J.M., Robinson J., Dansak D., Hilgers R.D. Psychological effects of vulvectomy. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Psychosom. Res. 1984 25:779–783. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(84)72965-3. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0033318284729653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thuesen B., Andreasson B., Bock J.E. Sexual function and somatopsychic reactions after local excision of vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1992 71:126–128. doi: 10.3109/00016349209007969. Available online: http://doi.wiley.com/10.3109/00016349209007969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jefferies H., Clifford C. A literature review of the impact of a diagnosis of cancer of the vulva and surgical treatment. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Clin. Nurs. 2011 20:3128–3142. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03728.x. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Janda M., Obermair A., Cella D., Perrin L., Nicklin J., Gordon-Ward B., Crandon A.J., Trimmel M. The functional assessment of cancer-vulvar: Reliability and validity. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Gynecol. Oncol. 2005 97:568–575. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.01.047. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825805001137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boden J., Willis S. The psychosocial issues of women with cancer of the vulva. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Radiother. Pract. 2019 18:93–97. doi: 10.1017/S1460396918000420. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1460396918000420/type/journal_article. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Niedzwiedz C.L., Knifton L., Robb K.A., Katikireddi S.V., Smith D.J. Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];BMC Cancer. 2019 19:943. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4. Available online: https://bmccancer.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walker J., Hansen C.H., Martin P., Sawhney A., Thekkumpurath P., Beale C., Symeonides S., Wall L., Murray G., Sharpe M. Prevalence of depression in adults with cancer: A systematic review. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Ann. Oncol. 2013 24:895–900. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds575. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0923753419371893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y.-H., Li J.-Q., Shi J.-F., Que J.-Y., Liu J.-J., Lappin J., Leung J., Ravindran A.V., Chen W.-Q., Qiao Y.-L., et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Mol. Psychiatry. 2020 25:1487–1499. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0595-x. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-019-0595-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jia Y., Li F., Liu Y., Zhao J., Leng M., Chen L. Depression and cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Public Health. 2017 149:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.04.026. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0033350617301737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Board C.N.E. Vulvar Cancer: Statistics. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)]. Available online: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/vulvar-cancer/statistics.

- 59.Baziliansky S., Cohen M. Emotion regulation and psychological distress in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Stress Health. 2021 37:3–18. doi: 10.1002/smi.2972. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smi.2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mokhatri-Hesari P., Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: Review of reviews from 2008 to 2018. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2020 18:1–25. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01591-x. Available online: https://hqlo.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12955-020-01591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Faria B.M., Rodrigues I.M., Marquez L.V., Pires U.D.S., de Oliveira S.V. The impact of mastectomy on body image and sexuality in women with breast cancer: A systematic review. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Psicooncología. 2021 18:91–115. doi: 10.5209/psic.74534. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/PSIC/article/view/74534. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang Y.-C., Chang S.-R., Chiu S.-C. Sexual Problems of Patients with Breast Cancer After Treatment. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Cancer Nurs. 2019 42:418–425. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000592. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valente M., Chirico I., Ottoboni G., Chattat R. Relationship Dynamics among Couples Dealing with Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021 18:7288. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18147288. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/14/7288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brandão T., Pedro J., Nunes N., Martins M., Costa M.E., Matos P.M. Marital adjustment in the context of female breast cancer: A systematic review. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Psycho-Oncol. 2017 26:2019–2029. doi: 10.1002/pon.4432. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/pon.4432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fradgley E.A., Bultz B.D., Kelly B.J., Loscalzo M.J., Grassi L., Sitaram B. Progress toward integrating Distress as the Sixth Vital Sign: A global snapshot of triumphs and tribulations in precision supportive care. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];J. Psychosoc. Oncol. Res. Pract. 2019 1:e2. doi: 10.1097/OR9.0000000000000002. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/jporp/Fulltext/2019/07000/Progress_toward_integrating_Distress_as_the_Sixth.2.aspx. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sopfe J., Pettigrew J., Afghahi A., Appiah L., Coons H. Interventions to Improve Sexual Health in Women Living with and Surviving Cancer: Review and Recommendations. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Cancers. 2021 13:3153. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133153. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/13/13/3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elit L., Reade C.J. Recommendations for Follow-up Care for Gynecologic Cancer Survivors. [(accessed on 30 October 2021)];Obstet. Gynecol. 2015 126:1207–1214. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001129. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/00006250-201512000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]