Abstract

Tcea3 is present in high concentrations in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) and functions to activate Lefty1, a negative regulator of Nodal signaling. The Nodal pathway has numerous biological activities, including mesoderm induction and patterning in early embryogenesis. Here, we demonstrate that the suppression of Tcea3 in mESCs shifts the cells from pluripotency into enhanced mesoderm development. Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and VEGFC, major transcription factors that regulate vasculogenesis, are activated in Tcea3 knocked down (Tcea3 KD) mESCs. Moreover, differentiating Tcea3 KD mESCs have perturbed gene expression profiles with suppressed ectoderm and activated mesoderm lineage markers. Most early differentiating Tcea3 KD cells expressed Brachyury-T, a mesoderm marker, whereas control cells did not express the gene. Finally, development of chimeric embryos that included Tcea3 KD mESCs was perturbed.

Keywords: Tcea3, Vasculogenesis, Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs)

INTRODUCTION

Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) derived from the inner cell mass (ICM) of peri-implantation blastocysts can proliferate indefinitely and commit to differentiation into all cell types in vitro and in vivo (1). Therefore, the study of ESCs—especially mESCs—has provided valuable insights into early embryogenesis in mammals (2). Extrinsic stimuli, such as exogenously imposed or autonomously produced cytokines, play critical roles in ESC fate determination by triggering distinct signaling cascades (3). Among these signals, Activin/Nodal signaling is recognized as a pivotal regulatory cue in instructing the fate of ESCs (4). Smad2-dependent Activin/Nodal signaling is dispensable for the self-renewal maintenance of mESCs, but is required for differentiation into various types of cells, especially mesoderm (5–7). Phospho-Smad2 activated by Activin/Nodal directly regulates the expression of a cohort of developmental regulators, such as Tapbp, to induce meso-endoderm differentiation (5).

The development of the vascular system is one of the earliest events in embryogenesis because the growing embryo needs a transportation system to supply oxygen and nutrients. Vascular development begins before the initiation of embryonic circulation by producing endothelial cell progenitors, which are assembled together to form an early primitive vessel network (8). Genetic deletion studies in mice revealed that activation of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway is essential for the generation of the ESC lineage and the vasculature (9,10).

Tcea3 is an isoform of the transcription elongation factor TFIIS (11). Previously, we reported that Tcea3 is highly enriched in mouse ESCs and inhibits Smad2 phosphorylation by activating the expression of Lefty1, a negative regulator of Nodal signaling (12). Like Activin/Nodal signaling, Tcea3 is also dispensable for self-renewal maintenance, but overexpression of Tcea3 impairs the in vitro differentiation capacity. Suppression of Tcea3 leads to enhanced expression of meso-endoderm markers during in vitro differentiation. In addition, mesoderm marker genes are downregulated in Tcea3-overexpressing mESCs under self-renewing culture conditions, suggesting that Tcea3 functions to regulate lineage differentiation of mESCs by modulating Smad2 phosphorylation (12). However, the role of Tcea3 in vasculogenesis of ESCs has not been examined. We report here that Tcea3 suppression enhances the vascular development potential of mESCs. We examined whether transcription factors regulating vascular development are activated in Tcea3 knocked-down (Tcea3 KD) mESCs. We also examined whether Tcea3 KD mESCs differentiate more rapidly under endothelial differentiation culture conditions. Finally, we confirmed that chimeric embryos developed from Tcea3 KD mESCs had highly vascularized skin at embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5). These findings support the importance of Tcea3 expression during vasculogenesis by ESCs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

J1 mESCs (catalog No. SCRC-1010) were purchased from ATCC (www.atcc.org) and maintained as described previously (13). Briefly, mESCs were maintained on 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes in ESC medium, which consists of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% horse serum (Gibco Invitrogen), 2 mM glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 µg/ml) (Gibco Invitrogen), 1 × nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and LIF (1,000 U/ml) (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were obtained from Modern Cell & Tissue Technologies, Inc. (Seoul, Korea) and cultured in gelatin-coated plates with EGM-2 medium and supplements (Lonza, CC-3162) in the presence of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Differentiation of ESCs

To induce spontaneous differentiation, mESCs were cultured in LIF-deficient ESC medium. The medium was changed every 2 days for mESC culture or differentiation. To confirm differentiation, alkaline phosphatase activity was measured by using the EnzoLyte™ pNPP Alkaline Phosphatase Assay kit (AnaSpec, catalog No. 71230), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For endothelial differentiation, mESCs and stable knockdown cells of Tcea3 were seeded at 2 × 105 cells in a 0.1% gelatin-coated 60-mm plate. The following day, the cells were used for endothelial differentiation, which consisted of two steps. First, the ESC culture medium was changed to a LIF-deficient ESC medium containing VEGF (50 ng/ml) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (20 ng/ml) and the cells were incubated for 48 h. Then, the differentiation medium was changed to EGM-2 medium with supplements (Lonza, CC-3162) for the next 5 days. After endothelial differentiation of mESCs, tube formation assays were performed to evaluate vessel formation by the differentiated endothelial cells. The differentiated cells and HUVECs were seeded at 3 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates on Matrigel (BD Biosciences, MA) that was previously polymerized for 30 min at 37°C. Changes in cell morphology were observed and photographed 24 h after seeding.

Genetic Modification of mESCs

A shRNA plasmid targeting mouse Tcea3 was purchased (RMM3981-97073145, Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA) to generate stable knockdown cell lines of Tcea3. shRNA plasmids were transfected into mESCs with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and stably transfected lines were established according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Microarrays

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and biotinylated cRNA was prepared from 0.55 µg of total RNA using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Following fragmentation, 1.5 µg of cRNA was hybridized to the Illumina Mouse WG-6 Expression Beadchip according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Arrays were scanned with an Illumina Bead Array Reader Confocal Scanner according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Array data processing and analysis were performed using Illumina BeadStudio v3.1.3 (Gene Expression Module v3.3.8).

Generation and Analysis of Chimeric Embryos

To determine the in vivo developmental potential of Tcea3 KD mESCs, chimeric embryos were made with GFP-expressing mESCs using standard ES cell transfer procedures for chimera production (Macrogen, Seoul, Korea). Typically, 8 to 12 GFP-expressing mESCs were injected into the cavity of a blastocyst from C57BL/6 mice. A total of 18−19 injected blastocysts were transferred into the uterus of a pseudopregnant ICR female at E2.5. Embryos were dissected at E13.5, and the contribution of injected mESCs was determined by the intensity of the GFP signal. For further histological analysis, embryos were embedded in paraffin using standard methods (14). Sections were cut at 7-µm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Inmmunocytochemistry

J1 mESCs and Tcea3 KD cells were cultured on gelatin-coated cover slips. The cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Next, the cells were incubated in blocking buffer (5% bovine serum albumin in PBS) at room temperature for 1 h and then in anti-Brachyury antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., catalog No. sc-20109) overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, catalog No. A21207) for 1 h in the dark. The cover slips were then washed with PBS and mounted with VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA, catalog No. H-1200). Images were visualized using an inverted microscope (ECLIPSE E600; Nikon, Kanagawa, Japan) and analyzed using the INFINITY2-1C software (Innerview 2.0, Lumenera, Canada).

RESULTS

Previously, we reported that Tcea3 KD mESCs have an enhanced differentiation capacity (12). However, we did not address the effect of Tcea3 on lineage-specific differentiation of mESCs. To understand the change in differentiation potential of Tcea3 KD mESCs, we analyzed the genome-wide gene expression profiles of Tcea3 KD mESCs under both self-renewing and early differentiating conditions.

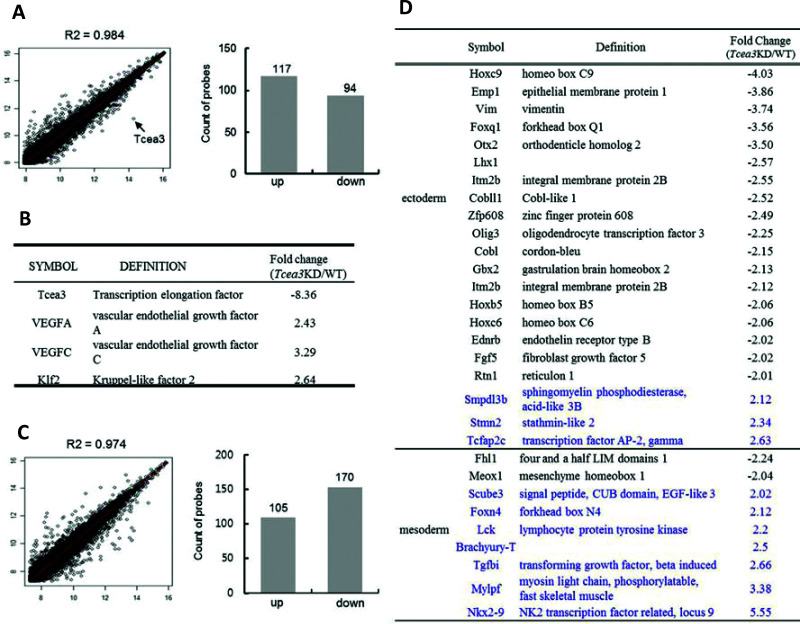

Scatter plots of the cDNA microarray results showed that suppression of Tcea3 did not alter the gene expression profiles of mESCs significantly (R 2 = 0.984). Among a total of 45,281 genes on the MouseWG-6 v2 Expression BeadChip (Illumina), expression of 211 genes (0.46% of the total) was significantly altered in Tcea3 KD cells according to a Student’s t test analysis with a 99% confidence level (upregulated: 117 genes; downregulated: 94 genes) (Fig. 1A). VEGF is a cytokine best known for inducing embryonic vasculogenesis (15). VEGFA was identified as one of 12 genes critical to vasculogenesis by systematic analysis of vascular defects in knockout mice (16), and VEGFC promotes vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in three-dimensional collagen gels (17). Interestingly, the microarray analysis of gene expression profiles of Tcea3 KD mESCs revealed that the expression of two isoforms of VEGF was activated in Tcea3 KD mESCs in self-renewing culture conditions (Fig. 1B). In addition, a Klf2 transcription factor, which modulates blood vessel maturation through smooth muscle cell migration, is also activated in Tcea3 KD mESCs (18). These results suggest that suppression of Tcea3 expression may enhance the vascular differentiation potential of mESCs. We next induced the spontaneous differentiation of mESCs by culturing the cells in the absence of LIF for 3 days and then analyzed the gene expression profiles by microarray analysis. Like the self-renewing cells, the gene expression profiles of differentiating Tcea3 KD cells were not significantly altered relative to mESCs (R 2 = 0.974) (Fig. 1C). Among the 45,281 genes examined, 0.61% (275 genes) were significantly altered in Tcea3 KD mESCs according to a Student’s t test with a 99% confidence level (downregulated: 105 genes; upregulated: 170 genes). All altered genes were classified using the PANTHER classification system, which classifies genes into families and subfamilies of shared function and categorizes them by molecular function, biological process, and pathway (http://www.pantherdb.org). Interestingly, whereas 7 of 9 genes related to mesoderm development were activated in differentiating Tcea3 KD mESCs, 18 of 21 ectoderm-related genes were suppressed (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that suppression of Tcea3 expression in self-renewing ESCs leads to enhanced expression of mesoderm lineage-related genes during differentiation of mESCs.

Figure 1.

Gene expression profiles of Tcea3 KD mESCs. (A) Scatter plots of cDNA microarray analysis of Tcea3 KD mESCs (R 2 = correlation coefficients) showing that 117 genes are activated and 94 genes are suppressed in Tcea3 KD mESCs. (B) Panther classification of 211 genes showed that major regulators of vasculogenesis are activated in Tcea3 KD mESCs. (C) Scatter plots of cDNA microarray analysis of differentiating Tcea3 KD mESCs (R 2 = correlation coefficients) showing that 105 genes are activated and 170 genes are suppressed in Tcea3 KD mESCs. Differentiation of mESCs was induced by culturing in medium lacking LIF for 3 days. (D) Panther classification of 275 genes showed that 18 of 21 ectoderm lineage marker genes were suppressed, whereas 7 of 9 mesoderm lineage marker genes were activated.

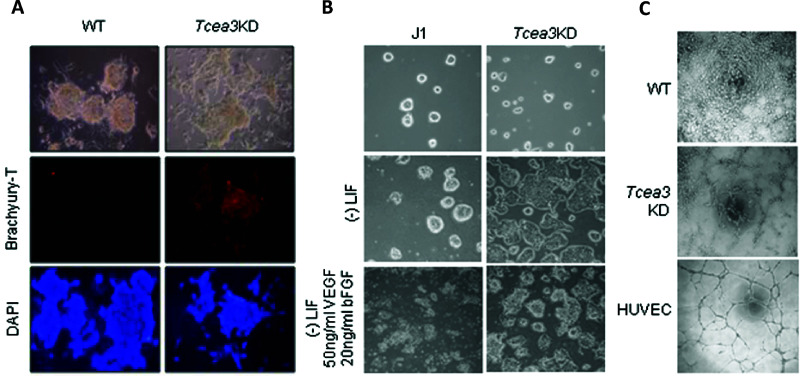

Based on the results of the microarray analysis of Tcea3 KD mESCs, we next investigated whether Tcea3 KD enhanced the differentiation capacity to mesoderm lineages. Most of the differentiating Tcea3 KD cells that were cultured under spontaneous differentiation culture conditions (as above) for 3 days express the mesoderm marker Brachyury-T (Fig. 2A). This result is consistent with the result of the microarray analysis (Fig. 1D) and further confirms that Tcea3 KD is prone to differentiate into mesodermal lineages.

Figure 2.

Tcea3 KD mESCs have an enhanced vascular differentiation potential. (A) Tcea3 KD and WT mESCs were induced to differentiate by culturing in medium lacking LIF for 3 days, and differentiating cells were immunostained with the mesoderm marker Brachyury-T. (B) Tcea3 KD and WT mESCs were induced to differentiate by culturing in medium lacking LIF, in the presence or absence of VEGF and bFGF, for 3 days. Differentiating cell morphology was examined by light microscopy. (C) Tube formation of endothelial-like cells differentiated from J1 and Tcea3 KD mESCs. After endothelial differentiation of mESCs for 7 days, the cells were plated on Matrigel to evaluate the vessel formation potential of the differentiated endothelial-like cells. More vessel-like structures were observed in endothelial-like cells differentiated from Tcea3 KD cells compared to those from WT ESCs.

We further confirmed the functional activity of endothelial-like cells differentiated from Tcea3 KD cell lines. The activity was evaluated by tube formation assays after endothelial differentiation of Tcea3 KD cell lines for 7 days. The cells were incubated in spontaneous differentiation culture medium containing VEGF (50 ng/ml) and FGF (20 ng/ml) for 2 days (Fig. 2B). Tcea3 KD cells showed a more differentiated cell morphology compared to wild-type (WT) mESCs in the presence of VEGF and bFGF (Fig. 2B). The cells were cultured in EGM medium for the next 5 days and then plated on Matrigel to confirm tube-forming potential (Fig. 2C). Tcea3 KD cells formed more vessel-like structures compared to WT mESCs (Fig. 2C). HUVECs were used as a positive control for tube formation (Fig. 2C).

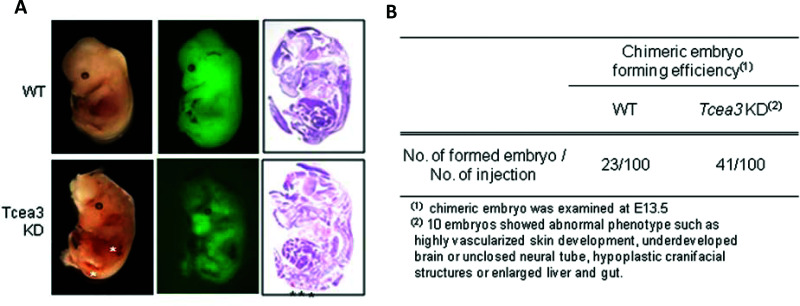

Finally, we further examined the in vivo developmental potential of Tcea3 KD cells by analyzing chimeric mice. GFP-expressing mESCs were injected into mouse blastocysts, and the chimeric embryo development was examined at E13.5. Chimeric embryos were successfully generated using Tcea3 KD as well as WT mESCs when the same numbers of GFP-expressing Tcea3 KD or WT mESCs were injected into the cavities of blastocysts from C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that Tcea3 KD mESCs retain basal in vivo pluripotency, although the differentiation capacity of the Tcea3 KD mESCs appeared to be significantly different during in vitro differentiation. Some chimeric embryos formed with Tcea3 KD cells showed highly vascularized skin, implying that alteration of Tcea3 expression affected in vivo pluripotency (Fig. 3A). In addition, other abnormal phenotypes, such as an underdeveloped brain, incomplete neural tube closure, hypoplastic cranifacial structures, and enlarged liver and gut, were observed in the chimeric embryos formed from Tcea3 KD cells (Fig. 3B and data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that Tcea3 is a key regulator controlling vasculogenesis by mESCs.

Figure 3.

Embryos that developed from Tcea3 KD mESCs exhibit abnormal phenotypes including highly vascularized skin. (A) Comparison of chimeric embryos generated by injecting GFP-expressing WT or Tcea3 KD mESCs. Left panels, morphological features of representative chimeric embryos; middle panels, GFP signals from the corresponding embryos; right panels, H&E-stained embryo midsagittal sections. All embryos generated from WT cells appeared normal. By contrast, highly vascularized tissues were detected from some embryos generated from Tcea3 KD as indicated by the asterisks. (B) The efficiency of chimeric embryo formation from blastocysts containing WT or Tcea3 KD mESCs. Whereas all embryos generated by WT cells look normal, some chimeric embryos generated by Tcea3 KD cells appeared developmentally abnormal.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we showed that Tcea3 regulates Lefty1, which is an inhibitor of Nodal-Smad2 signaling, in mESCs (12). Mesodermal differentiation markers were activated in Tcea3 KD cells in self-renewal culture conditions, and Tcea3 KD cells responded rapidly to external differentiation signals, probably due to the preactivated nodal-Smad2 signaling components (5,12). Because stem cells have been intensively investigated as a potential source of cells for proangiogenic therapies, including ischemic tissues, we studied the impact of altered Tcea3 expression on vasculogenesis by mESCs. In vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrated that suppression of Tcea3 promotes vasculogenesis by mESCs. Genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation chip analysis showed that development-related genes are direct targets of phospho-Smad2 (5). Importantly, the gene expression profile suggests that the underlying mechanism of enhanced vasculogenesis by Tcea3 KD cells is an enrichment of vasculogenesis-related genes in the ESCs under both self-renewal and differentiation conditions. Whether the expression of vasculogenesis-related genes is directly regulated by phospho-Smad2 will be important to determine in future studies. The unperturbed gene expression profiles of Tcea3 KD cells are consistent with a previous report indicating that Tcea3 is dispensable for self-renewal maintenance and specifically activates transcription elongation in its target genes (12).

Although more embryos developed from Tcea3 KD chimeric blastocysts than from WT chimeric blastocysts, the Tcea3 KD-derived embryos exhibited a number of developmental abnormalities (Fig. 3B), suggesting that modulation of gene expression by Tcea3 is crucial for normal development. In addition to highly vascularized skin development, chimeric embryos derived from Tcea3 KD mESCs exhibited failures in neural tube closure and had underdeveloped brains. These results suggest that expression level of Tcea3 may influence brain development, as well as vasculogenesis, during embryo development. Consistent with this result, Activin and TGF-β are reported to have effects on brain development and on the fate decisions of neural stem/progenitor cells both in vitro and in vivo (19). Therefore, elucidation of Tcea3 activity during development will be important for understanding the process of brain formation during embryogenesis. In this study, we suggest that Tcea3 regulates balanced lineage differentiation of mESCs, which is essential for normal development of embryo. Further studies regarding the role of Tcea3 in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis will contribute to the understanding of molecular mechanisms of pluripotency of ESCs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012M3A9C6050367, 2012R1A1A3003070). This research is also supported by the Priority Research Centers Program through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (20120006679) and Korea Health Technology R&D project, Ministry of Health & Welfare (A091087-0911-0000200).

REFERENCES

- 1. Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 1981; 292(5819):154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rossant J. Stem cells and early lineage development. Cell 2008, 132(4):527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pera MF, Tam PP. Extrinsic regulation of pluripotent stem cells. Nature 2010; 465(7299):713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Watabe T, Miyazono K. Roles of TGF-beta family signaling in stem cell renewal and differentiation. Cell Res 2009; 19(1):103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fei T, Zhu S, Xia K, Zhang J, Li Z, Han JD, et al. Smad2 mediates Activin/Nodal signaling in mesendoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Res 2010; 20(12):1306–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown S, Teo A, Pauklin S, Hannan N, Cho CH, Lim B, et al. Activin/Nodal signaling controls divergent transcriptional networks in human embryonic stem cells and in endoderm progenitors. Stem Cells 2011; 29(8):1176–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee KL, Lim SK, Orlov YL, Yit le Y, Yang H, Ang LT, et al. Graded Nodal/Activin signaling titrates conversion of quantitative phospho-Smad2 levels into qualitative embryonic stem cell fate decisions. PLoS Genet 2011; 7(6):e1002130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferguson JE 3rd, Kelley RW, Patterson C. Mechanisms of endothelial differentiation in embryonic vasculogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2005; 25(11):2246–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gerber HP, Malik AK, Solar GP, Sherman D, Liang XH, Meng G, et al. VEGF regulates haematopoietic stem cell survival by an internal autocrine loop mechanism. Nature 2002; 417(6892):954–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ng YS, Ramsauer M, Loureiro RM, D’Amore PA. Identification of genes involved in VEGF-mediated vascular morphogenesis using embryonic stem cell-derived cystic embryoid bodies. Lab Invest 2004; 84(9):1209–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Labhart P, Morgan GT. Identification of novel genes encoding transcription elongation factor TFIIS (TCEA) in vertebrates: Conservation of three distinct TFIIS isoforms in frog, mouse, and human. Genomics 1998; 52(3):278–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Park KS, Cha Y, Kim CH, Ahn HJ, Kim D, Ko S, et al. Transcription elongation factor Tcea3 regulates the pluripotent differentiation potential of mouse embryonic stem cells, via the Lefty1-Nodal-Smad2 pathway. Stem Cells 2013; 31(2):282–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jirmanova L, Afanassieff M, Gobert-Gosse S, Markossian S, Savatier P. Differential contributions of ERK and PI3-kinase to the regulation of cyclin D1 expression and to the control of the G1/S transition in mouse embryonic stem cells. Oncogene 2002; 21(36):5515–5528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaufman MH. Postcranial morphological features of homozygous tetraploid mouse embryos. J Anat 1992; 180(Pt. 3):521–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ferrara N. VEGF and the quest for tumour angiogenesis factors. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2(10):795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Argraves WS, Drake CJ. Genes critical to vasculogenesis as defined by systematic analysis of vascular defects in knockout mice. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 2005; 286(2):875–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bauer SM, Bauer RJ, Liu ZJ, Chen H, Goldstein L, Velazquez OC. Vascular endothelial growth factor-C promotes vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and collagen constriction in three-dimensional collagen gels. J Vasc Surg 2005; 41(4):699–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu J, Bohanan CS, Neumann JC, Lingrel JB. KLF2 transcription factor modulates blood vessel maturation through smooth muscle cell migration. J Biol Chem 2008; 283(7):3942–3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rodriguez-Martinez G, Velasco I. Activin and TGF-beta effects on brain development and neural stem cells. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2012; 11(7):844–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]