Abstract

As the leaf of Actinidia arguta has shown antioxidant activity, a study was conducted to identify the active ingredients. Forty-eight compounds were isolated from the leaves of A. arguta through various chromatographic techniques. Further characterization of the structures on the basis of 1D and 2D NMR and MS data identified several aromatic compounds, including phenylpropanoid derivatives, phenolics, coumarins, flavonoids and lignans. Among them, five compounds were newly reported, naturally occurring, and named argutosides A–D (1–4), which consist of phenylpropanoid glycosides that are conjugated with a phenolic moiety, and argutoside E (5), which is a coumarin glycoside that is conjugated with a phenylpropanoid unit. The isolated compounds showed good antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity with differences in activity depending on the structures. Molecular docking analysis demonstrated the interaction between the hydroxyl and carbonyl groups of compounds 1 and 5 with α-glucosidase. Taken together, the leaves of A. arguta are rich in aromatic compounds with diverse structures. Therefore, the leaves of A. arguta and their aromatic components might be beneficial for oxidative stress and glucose-related diseases.

Keywords: Actinidia arguta, aromatic, argutosides A–E, antioxidant, α-glucosidase, molecular docking analysis

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress is caused by the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which bind to molecules in vivo and consequently alter their structures and functions. An antioxidant-related defense mechanism exists to protect against generated ROS. However, persistent oxidative stress by excessive production of ROS eventually leads to diverse severe diseases such as cancer, inflammation and metabolic diseases [1,2,3].

Diabetes is a metabolic disease with a high incidence worldwide. In diabetes, the blood glucose level increases due to the abnormal operation of insulin, which causes various complications and develops into a serious disease [4]. Various factors are known to be involved in the onset and progression of diabetes; oxidative stress is one such mediator [5,6]. The increased ROS attack the pancreas and interfere with the normal function of insulin [7,8]. In other words, oxidative stress and diabetes are mutually detrimental to each other [9,10].

Accordingly, research into the development of a therapeutic agent for diabetes is being actively conducted. α-Glucosidase is an intestinal enzyme which converts carbohydrates into single monosaccharides. Therefore, α-glucosidase inhibitors are used for the treatment of diabetes and carbohydrate-mediated diseases [11,12]. Antioxidants are also used for the prevention and treatment of diabetes.

Natural products are good sources for antioxidants and are widely used in the prevention and treatment of various diseases [13]. In particular, polyphenols are representative components with antioxidant action and are present in various plants. In addition, they also have therapeutic potential for metabolic diseases and have shown excellent results in various diabetes models [14,15].

Actinidia arguta, also called hardy kiwifruit or kiwiberry, has small fruits with a smooth green skin. Due to its cold-resistant characteristic, it can be cultivated in Northeast Asia [16,17]. The grains of A. arguta are mainly consumed as fresh fruits while the cooked leaves are used in the treatment of various diseases with antioxidant, antibacterial, antidiabetic and anti-inflammatory effects [18,19,20]. We recognized the importance of A. arguta as a native plant together with its biological activities and, thus, investigated the efficacy and ingredients of A. arguta. As a follow-up study on A. arguta leaves [21], the antioxidant and anti-diabetic effects of the extracts were confirmed. Further investigation into the bioactive constituents of A. arguta leaves resulted in the isolation of 48 compounds, including five new compounds. On the basis of 1D and 2D NMR and MS data, the structures of the isolated compounds were determined to be aromatic and included phenylpropanoid derivatives, phenolics, coumarins, flavonoids and lignans. The antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the isolated compounds were measured and their mechanism of action was analyzed using molecular docking analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The leaves of A. arguta were obtained from a farm in Gwangyang, South Korea (GPS: DD 34.990714, 127.591508) in August 2016. After identification by the herbarium of the College of Pharmacy Chungbuk National University, voucher specimens (CBNU2016-AAL) were deposited in a specimen room of the herbarium.

2.2. General Experimental Procedure

The UV and IR spectra were obtained using Jasco UV-550 (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) and Perkin–Elmer model LE599 (Perkin–Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) spectrometer, respectively. A Bruker DRX 400 or 500 MHz spectrometer (Bruker-Biospin, Karlsruhe, Germany) were used for the analysis of NMR signals using CD3OD as a solvent. ESIMS and HRESI-TOF-MS data were obtained on LCQ Fleet and maXis 4G mass spectrometers (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany), respectively. Semi-preparative HPLC (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was performed using a Waters 515 HPLC pump with a 996-photodiode array detector, and Waters Empower software using a Gemini-NX ODS-column (150 × 10.0 mm and 150 × 21.2 mm). Column chromatography procedures were performed using silica gel (200–400 mesh, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Sephadex LH-20 (25–100 µm, Pharmacia Fine Chemical Industries Co., Uppsala, Sweden). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using aluminum plates precoated with Kieselgel 60 F254 (0.25 mm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

2.3. Extraction and Isolation

The dried powder of A. arguta leaves (4.0 kg) was extracted with 80% MeOH (30 L × 2) at room temperature. The MeOH extract (350.0 g) was suspended in H2O (2 L) and partitioned successively with n-hexane, CH2Cl2, EtOAc and n-BuOH (each 2L × 2) for 24 h.

The CH2Cl2 fraction (AALC, 24.1 g) was chromatographed on silica gel and eluted with a mixture of n-hexane-EtOAc (100% n-hexane to 100% EtOAc) to obtain fourteen subfractions (AALC1-C14). Subfraction C13 (3.2 g) was subjected to MPLC on RP-silica gel and eluted with mixtures of MeOH-H2O (5% MeOH to 100% MeOH) to give three subfractions (C13A-C13C). Compounds 12 and 43 were purified from C13B and C13C, respectively, by semi-preparative HPLC and eluted with acetonitrile-H2O (20:80). Compounds 41, 42 and 47 were purified from C14 F by Sephadex LH-20 and eluted with MeOH followed by semi-preparative HPLC and elution with acetonitrile-H2O (20:80).

The EtOAc fraction (AALE, 24.4 g) was chromatographed on silica gel and eluted with a mixture of CH2Cl2-MeOH by step gradient (100% CH2Cl2 to 100% MeOH) to obtain eleven subfractions (AALE1-E11). Subfraction E4 (2.5 g) was subjected to MPLC on RP-silica gel and eluted with mixtures of MeOH-H2O (5% to 100% MeOH) to give six subfractions (E4A–E4F). Subfraction E4C was separated into two subfractions (E4F1–E4F2) by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH). Compounds 9, 10, 13, 14 and 20 were purified from E4C2 by semi-preparative HPLC (acetonitrile-H2O, 20:80). E5 (2.9 g) was subjected to MPLC on RP-silica gel (mixtures of MeOH-H2O, 5% to 100% MeOH) to give eight subfractions (E5A–E5H). Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography (MeOH) of E5B, E5C, E5G and E5H gave compounds 11, 8, 31 and 22, respectively. Compounds 17 and 18 were isolated from E5D by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) followed by semi-preparative HPLC and elution with acetonitrile-H2O (30:70). Subfraction E5F was separated by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to obtain E5F1 and E5F2, which gives compounds 32 and 29, respectively, by semi-preparative HPLC and elution with acetonitrile-H2O (30:70).

Subfraction E6 (3.2 g) was subjected to MPLC on RP-silica gel and eluted with mixtures of MeOH-H2O (5% MeOH to 100% MeOH) to give eight subfractions (E6A–E6H). Compounds 12 and 15 were purified from E6B by semi-preparative HPLC (acetonitrile-H2O, 50:50). Compounds 16 and 19 were purified from E6C by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) followed by semi-preparative HPLC (acetonitrile-H2O, 50:50). Compounds 30 and 25 were purified from E6D and E6F, respectively, by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH). E7 (2.6 g) was subjected to MPLC on RP-silica gel and eluted with mixtures of MeOH-H2O (10% MeOH to 100% MeOH) to give nine subfractions (E7A–E7I). E7D was separated to obtain E7D1 by Sephadex LH-20 and eluted with MeOH. Compound 40 was purified from E7D1 by semi-preparative HPLC and eluted with acetonitrile-H2O (30:70).

Subfraction E8 (4.2 g) was subjected to MPLC on RP-silica gel and eluted with mixtures of MeOH-H2O (5% to 100% MeOH) to give nine subfractions (E8A–E8I). E8C, E8D and E8E were subjected to Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give compound 37, 36 and 38, respectively. Subfraction E8G was separated by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to obtain E8G1 and E8G2, which gives compounds 44 and 39, respectively, by semi-preparative HPLC and elution with MeCN-H2O (20:80). E8I (2.9 g) was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give four subfractions (E8I1–E8I4). Compounds 45 and 46 were isolated from E8I2 by semi-preparative HPLC (acetonitrile-H2O, 18:82). Semi-preparative HPLC (acetonitrile-H2O, 18:82) of E8I4 gives compounds 1, 5, 6, 7 and 28.

Subfraction E9 (5.0 g) was subjected to MPLC on RP-silica gel and eluted with mixtures of MeOH-H2O (5% to 100% MeOH) to give ten subfractions (E9A–E9J). Compounds 33, 23, 34 and 35 were isolated from E9E, E9H, E9I and E9J, respectively, by Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH). Subfraction E9H was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give 3 subfractions (E9H1–E9H3). Compounds 2 and 3 were purified from E9H2 by semi-preparative HPLC (acetonitrile-H2O, 20:80). Subfraction E9I was subjected to Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to give 4 subfractions (E9I1–E9I4). Compounds 4 and 48 were obtained from E9I2 by semi-preparative HPLC (acetonitrile-H2O, 23:77). Compounds 24, 26 and 27 were purified from E9I3 by semi-preparative HPLC (MeCN-H2O, 20:80).

2.3.1. Argutoside A (1)

Brown syrup; IR νmax 3411, 1664 cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) and 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD), see Tables 1 and 2, Figures S1–S4; HRESI-TOF-MS (positive mode) m/z 511.1210 (calcd. for C24H24NaO11, 511.1216, Figure S5).

2.3.2. Argutoside B (2)

Brown syrup; IR νmax 3411, 1631 cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) and 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD), see Tables 1 and 2, Figures S6–S9; HRESI-TOF-MS (positive mode) m/z 485.1418 (calcd. for C23H26NaO10, 485.1424, Figure S10).

2.3.3. Argutoside C (3)

Brown syrup; IR νmax 3411, 1666 cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) and 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD), see Tables 1 and 2, Figures S11–S14: ESIMS m/z 485 [M + Na]+; HRESI-TOF-MS (positive mode) m/z 485.1418 ([M + Na]+ calcd. for C23H26NaO10, 485.1424, Figure S15).

2.3.4. Argutoside D (4)

Brown syrup; IR νmax 3423, 1666 cm−1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) and 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD), see Tables 1 and 2, Figures S16–S19; HRESI-TOF-MS m/z 529.1680 (calcd. for C25H30NaO11, 529.1686, Figure S20).

2.3.5. Argutoside E (5)

Brown syrup; IR νmax 3419, 1660 cm-1; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) and 13C-NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6), see Table 3 and Figures S21–S24; HRESI-TOF-MS m/z 525.1003 (calcd. for C24H22NaO12, 525.1009, Figure S25).

2.4. Measurement of α-Glucosidase Activity

The inhibitory effect on α-glucosidase was measured using α-glucosidase (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (EC 3.2.1.20) [21]. A test sample was mixed with 80 μL enzyme buffer and 10 μL α-glucosidase and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, after the addition of 10 μL p-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside solution for enzyme reaction, the amount of p-nitrophenol that was cleaved by the enzyme was determined by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm in a 96-well microplate reader. Acarbose was used as a positive control.

2.5. Measurement of DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

The antioxidant activity was evaluated by measuring the free radical scavenging activity using DPPH as previously reported [20]. In brief, freshly prepared DPPH solution was mixed with the samples. The mixture was reacted at room temperature for 10 min, and the absorbance was measured at 550 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control.

2.6. Molecular Docking Studies

SYBYL-X 2.1.1 (Tripos Ltd., St. Louis, MO, USA) with crystal structures of N-terminal subunit (NtMGAM; PDB-ID: 2QMJ) and C-terminal subunit (CtMGAM; PDB-ID: 3TOP) of human maltase-glucoamylase (MGAM) were used, respectively, for molecular docking studies of active compounds [19].

3. Results

3.1. Structural Elucidation

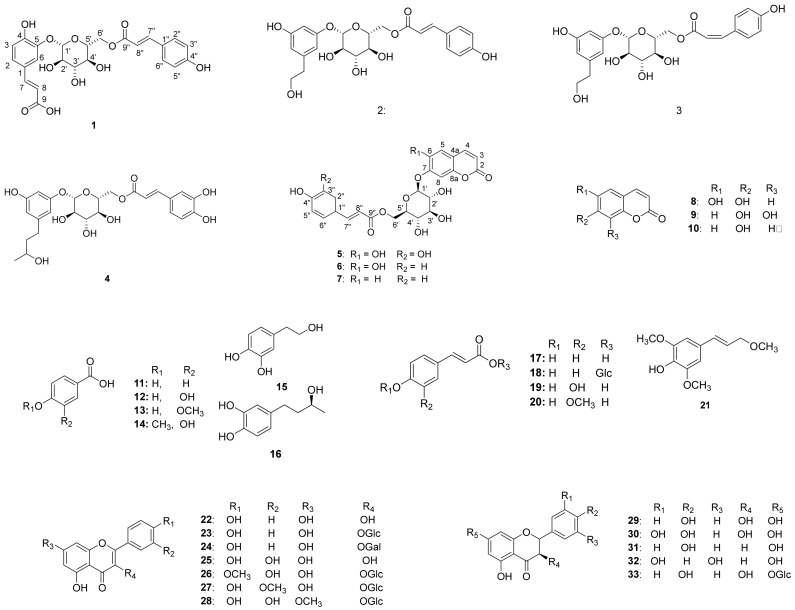

Chromatographic separation of the EtOAc fraction of A. arguta resulted in the isolation of five new compounds (1–5) together with forty-three known compounds (6–48) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–48 from the leaves of A. arguta.

3.1.1. Structural Determination of New Compounds

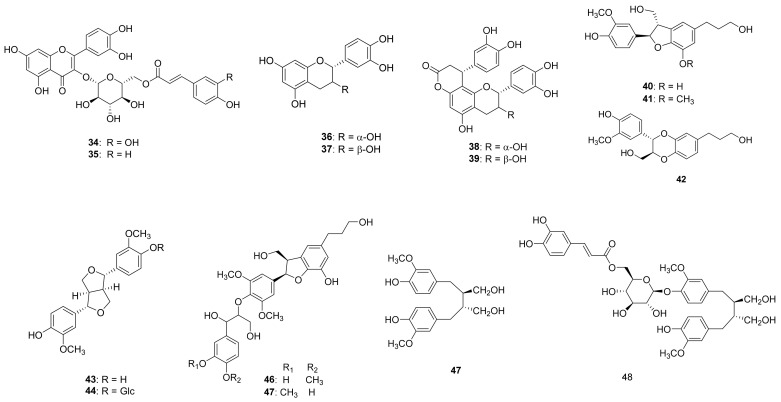

Compound 1 (Table 1 and Table 2) was isolated as a brown syrup and the molecular formula was deduced as C24H24O11 from the HRESI-TOF-MS (m/z 511.1210 [M + Na]+, calcd. for C24H24NaO11, 511.1216) and 13C-NMR data. The IR spectrum showed typical absorption bands of hydroxy and carbonyl groups at 3411 and 1664 cm−1, respectively. The 1H-NMR spectrum of compound 1 showed typical signals for a glucosyl anomeric proton in the β-configuration at δH 4.92 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, H-1′). The presence of a glucosyl moiety was also confirmed by the glucosyl carbon signals at 101.9 (C-1′), 73.3 (C-2′), 76.0 (C-3′), 70.6 (C-4′), 74.3 (C-5′), 63.5 (C-6′)]. In the aromatic regions of the 1H- and 13C-NMR, signals for a 1,3,4-trisubstituted aromatic ring at [δH 7.41 (1H, d, J = 2.0 Hz, H-2), 7.17 (1H, d, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, H-6), 6.88 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-5); δC 126.6 (C-1), 116.0 (C-2), 145.4 (C-3), 149.4 (C-4), 116.1 (C-5), 124.4 (C-6)] and a 1,4-disubstituted aromatic ring at [δH 7.42 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-3”, 5”), 6.80 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-2”, 6”); δC 125.7 (C-1”), 115.4 (C-2”, 6”), 129.9 (C-3”, 5”), 159.9 (C-4”)] were observed. The 1H-NMR spectrum also revealed two pairs of olefinic groups in the trans configuration at [δH 7.58 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-7), 6.33 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-8); δc 144.7 (C-7), 116.1 (C-8)] and [δH 7.61 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-7”), 6.34 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-8”); δc 145.7 (C-7”), 113.2 (C-8”)], respectively. Additionally, signals for two carbonyl carbons [δC 169.6 and 167.8] were observed in the 13C-NMR spectrum. These signals were assigned to the trans-caffeoyl group and the trans-coumaroyl group based on the HMBC correlations between H-7/C-1, H-7/C-9 and H-2”/C-7”, H-7”/C-9”, respectively (Figure 2). Therefore, compound 1 was suggested to consist of a glucose, a trans-caffeoyl group and a trans-coumaroyl group. The connections between these moieties were determined by HMBC correlation. The HMBC correlations from H-1′ of a glucose to C-5 of a trans-caffeoyl group, and from H-6′ of a glucose to C-9″ of a trans-coumaroyl group suggested the linkages of a trans-caffeoyl group to a glucose and a glucose to a trans-coumaroyl group. Combined with the above-mentioned data, compound 1 was elucidated as shown and named argutoside A.

Table 1.

1H-NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 1–4 (CD3OD).

| Title 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 7.41 (d, 2.0) | 6.78 (s) | 6.78 (s) | 6.76 (s) |

| 4 | - | 6.78 (s) | 6.78 (s) | 6.76 (s) |

| 5 | 6.88 (d, 8.4) | - | - | - |

| 6 | 7.17 (dd, 8.4, 2.0) | 7.04 (s) | 7.04 (s) | 7.00 (s) |

| 7 | 7.58 (d, 15.6) | 2.67 (2H, t, 7.2) | 2.71 (2H, t, 7.2) | 2.53 (2H, m) |

| 8 | 6.33 (d, 15.6) | 3.67 (2H, t, 7.2) | 3.70 (2H, t, 7.2) | 1.63 (2H, m) |

| 9 | - | - | - | 3.62 (m) |

| 10 | - | - | - | 1.11 (3H, d, 6.0) |

| 1′ | 4.92 (d, 7.6) | 4.78 (d, 7.6) | 4.76 (d, 7.6) | 4.77 (d. 7.2) |

| 2′ | 3.41–3.57 (m) | 3.40–3.54 (m) | 3.40–3.52 (m) | 3.41–3.54 (m) |

| 3′ | 3.41–3.57 (m) | 3.40–3.54 (m) | 3.40–3.52 (m) | 3.41–3.54 (m) |

| 4′ | 3.41–3.57 (m) | 3.40–3.54 (m) | 3.40–3.52 (m) | 3.41–3.54 (m) |

| 5′ | 3.82 (m) | 3.73 (m) | 3.67 (m) | 3.74 (m) |

| 6′ | 4.59 (dd, 12.0, 2.0) | 4.60 (dd, 12.0, 2.0) | 4.55 (dd, 12.0, 2.0) | 4.59 (dd, 12.0, 2.4) |

| 4.38 (dd, 12.0, 6.6) | 4.37 (dd, 12.0, 6.6) | 4.33 (dd, 12.0, 6.6) | 4.37 (dd, 12.0, 6.8) | |

| 2′′ | 6.80 (d, 8.8) | 6.83 (d, 8.8) | 6.73 (d, 8.8) | 7.08 (d, 1.6) |

| 3′′ | 7.42 (d, 8.8) | 7.50 (d, 8.8) | 7.66 (d, 8.8) | - |

| 5′′ | 7.42 (d, 8.8) | 7.50 (d, 8.8) | 7.66 (d, 8.8) | 6.80 (d, 8.4) |

| 6′′ | 6.80 (d, 8.8) | 6.83 (d, 8.8) | 6.73 (d, 8.8) | 6.97 (dd, 8.4, 1.6) |

| 7′′ | 7.61 (d, 16.0) | 7.68 (d, 16.0) | 6.93 (d, 12.8) | 7.60 (d, 15.6) |

| 8′′ | 6.34 (d, 16.0) | 6.41 (d, 16.0) | 5.83 (d, 12.8) | 6.33 (d, 15.6) |

Table 2.

13C-NMR spectroscopic data for compounds 1–4 (CD3OD).

| Carbon NO. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 126.6 | 130.7 | 130.6 | 133.9 |

| 2 | 116.0 | 123.9 | 123.9 | 123.2 |

| 3 | 145.4 | 145.1 | 145.1 | 144.8 |

| 4 | 149.4 | 115.5 | 115.5 | 115.5 |

| 5 | 116.1 | 145.3 | 145.3 | 145.1 |

| 6 | 124.4 | 118.1 | 118.1 | 117.5 |

| 7 | 144.7 | 38.2 | 38.2 | 31.1 |

| 8 | 115.5 | 62.9 | 63.0 | 40.6 |

| 9 | 169.6 | - | - | 66.3 |

| 10 | - | - | - | 22.1 |

| 1′ | 101.9 | 102.9 | 102.9 | 102.9 |

| 2′ | 73.3 | 73.4 | 73.4 | 73.4 |

| 3′ | 76.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 | 76.0 |

| 4′ | 70.6 | 70.4 | 70.3 | 70.4 |

| 5′ | 74.3 | 74.4 | 74.3 | 74.4 |

| 6′ | 63.5 | 63.3 | 63.0 | 63.3 |

| 1” | 125.7 | 125.7 | 126.1 | 126.2 |

| 2” | 115.4 | 115.4 | 114.4 | 113.7 |

| 3” | 129.9 | 129.9 | 132.4 | 145.5 |

| 4” | 159.9 | 160.0 | 158.7 | 148.3 |

| 5” | 129.9 | 129.9 | 132.4 | 115.1 |

| 6” | 115.4 | 115.4 | 114.4 | 121.8 |

| 7” | 145.7 | 145.6 | 144.3 | 146.0 |

| 8” | 113.2 | 113.4 | 114.7 | 113.3 |

| 9” | 167.8 | 167.6 | 166.6 | 167.6 |

Figure 2.

Key HMBC correlations (→) of new compounds 1–5.

Compound 2 (Table 1 and Table 2) was purified as a brown syrup. The molecular formula was deduced as C23H26NaO10 from the HRESI-TOF-MS (m/z 485.1418 [M + Na]+, calcd. for C23H26NaO10, 485.1424)), which was verified by its 13C-NMR data. Similar to compound 1, the presence of a glucose was easily deduced from glucosyl anomeric signals [δH 4.78 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, H-1′); δC 102.9]. The presence of a trans-coumaroyl group was also suggested by the signals at [δH 6.83 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-2”, 6”), 7.50 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, H-3”, 5”), 7.68 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-7”), 6.41 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-8”); δC 125.7 (C-1”), 115.4 (C-2”, 6”), 129.9 (C-3”, 5”), 160.0 (C-4”), 145.6 (C-7”), 113.4 (C-8”), 167.6 (C-9”)] together with the HMBC correlations. Besides the aforementioned signals for a glucose and trans-coumaroyl group, signals for a 1,3,5-trisubstituted aromatic ring [δH 6.78 (2H, s, H-2, 4), 7.04 (1H, s, H-6); δC 130.7 (C-1), 123.9 (C-2), 145.1 (C-3), 115.5 (C-4), 145.3 (C-5), 118.1 (C-6)] two methylene [δH 2.67 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-7), 3.67 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-8); δC 38.2 (C-7), 62.9 (C-8)], and an oxygenated methine [δH 3.62 (1H, m, H-9); δC 66.3] were observed in 1H- and 13C-NMR together with HSQC spectrum. These additional signals were assigned to a 3, 5-dihydroxyphenylethanol group based on the correlations between H-2/C-7 and H-8/C-7 in the HMBC spectrum. The positions of a 3, 5-dihydroxyphenylethanol group and a trans-coumaroyl group were determined to be C-1′ and C-6′, respectively, from the HMBC correlations of H-1′/C-3 and H-6′/C-9”. Consequently, the structure of compound 2 was defined as shown and named argutoside B. The 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of 3 (Table 1 and Table 2) were similar to those of compound 2, with the difference being the replacement of the trans-olefinic protons with a large coupling constant [δH 7.68 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-7”), 6.41 (1H, d, J = 16.0 Hz, H-8”)] by cis-olefinic protons with a smaller coupling constant [δH 6.93 (1H, d, J = 12.8 Hz, H-7′), 5.86 (1H, d, J = 12.8 Hz, H-8′)]. Therefore, the structure of compound 3 was defined as shown and named argutoside C.

Compound 4 (Table 1 and Table 2) was purified as brown syrup. The molecular formula was deduced as C25H30NaO11 from the HRESI-TOF-MS (m/z 529.1680 [M + Na]+, calcd. for C25H30NaO11, 529.1686), which was verified by its 13C-NMR data. Similar to compounds 1–3, the presence of a glucose was easily deduced from glucosyl anomeric signals [δH 4.77 (1H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, H-1′); δC 102.9]. The presence of a trans-caffeoyl group was also suggested from the signals at [δH 7.08 (1H, d, J = 1.6 Hz, H-2”), 6.80 (1H, d, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, H-5”), 6.97 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-6”), 7.60 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-7”), 6.33 (1H, d, J = 15.6 Hz, H-8”); δC 126.2 (C-1”), 113.7 (C-2”), 145.5 (C-3”), 148.3 (C-4”), 115.1 (C-5”), 121.8 (C-6”), 146.0 (C-7”), 113.3 (C-8”), 167.6 (C-9”)] together with the HMBC correlations. Besides the aforementioned signals, signals for a 1,3,5-trisubstituted aromatic ring [δH 6.76 (2H, s, H-2, 4), 7.00 (1H, s, H-6); δC 133.9 (C-1), 123.2 (C-2), 144.8 (C-3), 115.5 (C-4), 145.1 (C-5), 117.5 (C-6)], two methylene [δH 2.53 (2H, m, H-7), 1.63 (2H, m, H-8); δC 31.1 (C-7), 40.6 (C-8)], an oxygenated methine [δH 3.62 (1H, m, H-9); δC 66.3] and a methyl group [δH 1.11 (3H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, H-10); δC 22.1] were observed in 1H- and 13C-NMR together with the HSQC spectrum. The HMBC correlations of H-2/C7, H-8/C-9 and H-10/C-9 attributed the connection of a 1-(3,5-dihydroxyphenyl)-butan-3-ol group to the glucose and trans-caffeoyl groups. The HMBC correlations of H-1′/C-3 and of H-6′/C-9″ confirmed the linkage between a trans-caffeoyl group, a glucose and a 1-(3,5-dihydroxyphenyl)-butan-3-ol group, as shown in Figure 2. Conclusively, compound 4 was defined as shown and named argutoside D.

Compound 5 (Table 3) was purified as a brown syrup with the molecular formula of C24H22O12 deduced by HRESI-TOF-MS analysis (m/z 525.1003, calcd. for C24H22NaO12, 525.1009) and 13C-NMR data. The 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra of compound 5 showed the signals for a glucose and a trans-coumaroyl group, similar to those of compounds 1–4. However, signals for two cis-olefinic protons at δH 7.68 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-4) and 5.85 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, H-3) suggested that compound 5 was a coumarin derivative, which was supported by the characteristic UV absorption maxima at 211 and 327 nm. Additionally, two aromatic protons at δH 7.24 (1H, s, H-5) and δH 6.74 (1H, s, H-8) together with 13C-NMR signals of δC 166.8 (C-2), 111.7 (C-3), 144.7 (C-4), 110.6 (C-4a), 114.7 (C-5), 151.1 (C-6), 143.2 (C-7), 103.7 (C-8), 146.1 (C-8a)] suggested the existence of one 6,7-disubstituted coumarin skeleton. Further analysis using the HMBC correlation together with a comparison to the previous data identified the coumarin moiety as 6,7-dihydroxycoumarin, esculetin [22]. Therefore, compound 1 was suggested to consist of a glucose, a trans-caffeoyl group and a 6,7-dihydroxycoumarin moiety. The HMBC correlations from H-1′ of a glucose to C-7 of a 6,7-dihydroxycoumarin group suggested the linkage between 6,7-dihydroxycoumarin and a glucose, and the HMBC correlations from H-6′ of a glucose to C-9″ of trans-caffeoyl group suggested the linkage between a glucose and a trans-caffeoyl group. Based on these data, the structure of compound 5 was defined as esculetin 7-O-(6′-O-trans-caffeoyl)-β-glucopyranoside and named argutoside E.

Table 3.

1H- and 13C-NMR spectroscopic data for compound 5 (DMSO-d6).

| Carbon NO. | 1H | 13C |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | - | 166.8 |

| 3 | 5.85 (d, 9.2) | 111.7 |

| 4 | 7.68 (d, 9.2) | 144.7 |

| 4a | - | 110.6 |

| 5 | 7.24 (s) | 114.7 |

| 6 | - | 151.1 |

| 7 | - | 143.2 |

| 8 | 6.74 (s) | 103.7 |

| 8a | - | 146.1 |

| 1′ | 4.81 (d, 7.2) | 102.3 |

| 2′ | 3.34–3.50 (m) | 73.6 |

| 3′ | 3.34–3.50 (m) | 76.3 |

| 4′ | 3.34–3.50 (m) | 70.5 |

| 5′ | 3.68 (m) | 74.5 |

| 6′ | 4.45 (dd, 12.0, 1.6), 4.24 (dd, 12.0, 7.2) | 63.8 |

| 1” | - | 125.9 |

| 2” | 7.06 (d, 1.6) | 115.4 |

| 3” | - | 146.1 |

| 4” | - | 149.0 |

| 5” | 6.77 (d, 8.0) | 116.2 |

| 6” | 6.99 (dd, 8.0, 1.6) | 121.9 |

| 7” | 7.49 (d, 16.0) | 145.8 |

| 8” | 6.32 (d, 16.0) | 114.3 |

| 9” | - | 166.8 |

3.1.2. Identification of Known Compounds

The known compounds were identified as esculetin 7-O-(6′-O-trans-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside (6) [23], umbelliferone 7-O-(6′-O-trans-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside (7) [23], esculetin (8) [22], 7,8-Dihydroxycoumarin (9) [24], umbelliferone (10) [25], 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (11) [26], protocatechuic acid (12) [26], vanillic acid (13) [27], isovanillic acid (14) [28], hydroxytyrosol (15) [28], (-)-rhodolatouchol (16) [29], p-E-coumaric acid (17) [30], p-E-coumaric acid-9-O-glucopyranoside (18) [23], E-caffeic acid (19) [28], E-ferulic acid (20) [31], 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic alcohol (21) [32], kaempferol (22) [33], kaempferol 3-O-β-glucopyranoside (23) [34], kaempferol 3-O-β-galactopyranoside (24) [35], quercetin (25) [36], tamarixin (26) [37], isorhamnetin 3-O-β-glucopyranoside (27) [30], rhamnetin 3-O-β-glucopyranoside (28) [35], dihydrokaempferol (29) [35], dihydroquercetin (30) [38], naringenin (31) [35], 5,7,3′,5′-tetrahydroxyflavanone (32) [38], sinensin (33) [39], quercetin 3-O-(6”-O-E-caffeoyl)-β-glucopyranoside (34) [39], quercetin 3-O-(6”-O-E-coumaroyl)-β-glucopyranoside (35) [40], epicatechin (36) [30], catechin (37) [35], cinchonain Ia (38) [41], catechin-[8,7-e]-4b-(3,4-dihydroxy-phenyl)-dihydro-2(3H)-pyranone (39) [40], 7S,8R-cedrusin (40) [42], dehydroconiferyl alcohol (41) [40], (7S,8S)-3-methoxy-3′,7-epoxy-8,4′-oxyneoligna-4,9,9′-triol (42) [43], pinoresinol (43) [44], pinoresinol 4-O-β-glucopyranoside (44) [42], alutaceuol (45) [29], alutaceuol isomer (46) [29], (-)-(2R,3R)-secoisolariciresinol (47) [45], glehlinoside F (48) [46] via analysis of their physical data and comparison with literature values.

3.2. Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity

3.2.1. Antioxidant and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of Compounds

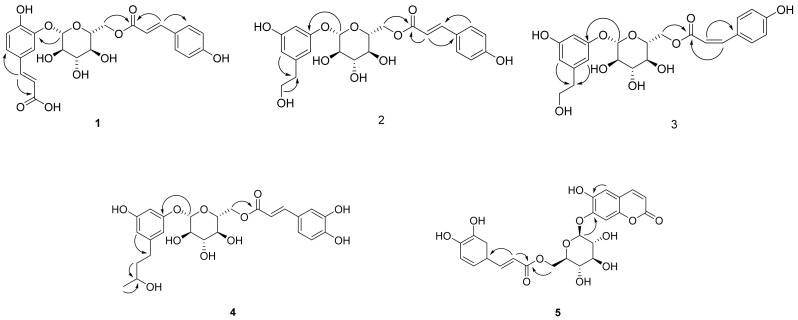

The antioxidant and anti-diabetic activity of the isolated compounds were evaluated by measuring the DPPH radical scavenging and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. The isolated compounds showed good antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity with differences in activity depending on the structures. In particular, new compounds 1, 2, 4 and 5 showed antioxidant activity and compounds 1, 3 and 5 showed α-glucosidase inhibitory activity in our assay system (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of compounds 1–48 from A. arguta leaves.

As described above, the leaf of A. arguta is rich in phenolic compounds, and a total of 48 compounds were purified in this study. All 48 of the compounds that were isolated in this study are aromatic compounds and can be subdivided according to the compound skeleton as follows: phenylpropanoid derivatives (1–4, 16–21), coumarins (5–10), simple phenolics (11–15), flavonoids (22–39) and lignans (40–48). The biological activity of the isolated compounds differs depending on their structure, and flavonoid showed excellent efficacy while lignan showed comparatively weak efficacy in our assay system. Interestingly, the leaf of A. arguta contained phenolic-conjugates that were bound to various skeletons such as phenylpropanoid-conjugates, coumarin-conjugates, flavonoid-conjugates and lignan-conjugates. These conjugates showed antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity and contributed to the beneficial effect of A. arguta leaves.

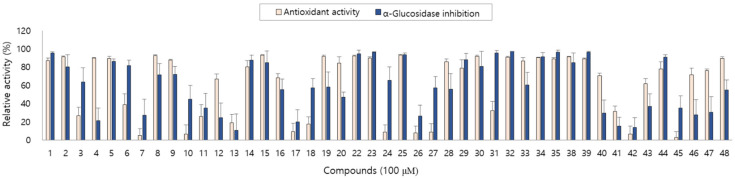

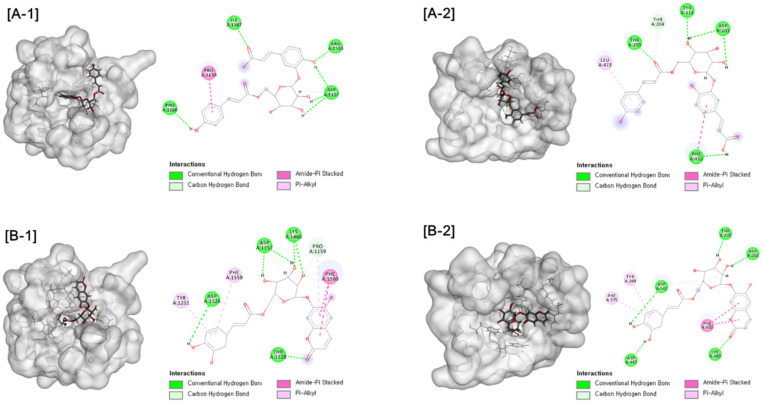

3.2.2. Molecular Docking Analysis

Further molecular docking analysis was conducted for two types of human maltase-glucoamylase (NtMGAM and CtMGAM) in order to propose the mechanisms of the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of active compounds. Consistent with experimental results, interactions with the α-glucosidase were suggested for active compounds. Hydrogen bonds were formed between compound 1 and NtMGAM and CtMGAM, respectively. Compound 5 exhibited the interaction by forming hydrogen bonds and Pi-alkyl interactions, as shown in Figure 4. These results indicate that compounds 1 and 5 could be inserted into the active site of the enzyme by different types of interactions and could inhibit α-glucosidase activity.

Figure 4.

[A] Docking picture of compound 1 to CtMGAM (A-1) and NtMGAM (A-2) and [B] compound 5 to CtMGAM (B-1) and NtMGAM (B-2). The interactions of conventional hydrogen bond (green color), carbon hydrogen bond (light green color), amide-Pi stacked (pink color) and Pi-alkyl (light pine) were shown.

4. Conclusions

An investigation into the leaves of A. arguta led to the isolation of 48 aromatic compounds, including 5 new compounds. The structures of the isolated compounds were determined to be aromatic, including phenylpropanoid derivatives, phenolics, coumarins, flavonoids and lignans. Five new compounds were defined as argutosides A–D (1–4), which consist of phenylpropanoid glycosides conjugated with a phenolic compound, and argutosides E (5), which is a coumarin glycoside conjugated with a phenylpropanoid. The isolated compounds showed good antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity with differences in activity depending on the structures. The analysis of the interactions between hydroxyl and carbonyl groups of active compounds 1 and 5 and α-glucosidase by molecular docking analysis supported the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. In conclusion, the aromatic constituents of A. arguta leaves with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity might be beneficial to glucose-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Korea Basic Science Institute for the NMR spectroscopic measurements.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox10121896/s1, Figures S1–S25: 1H, 13C, HSQC, HMBC and HRESI-MS spectrums of new compounds 1–5.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H.A. and M.K.L.; methodology, J.H.A., S.H.R., S.L., S.W.Y. and A.T.; software, Y.K.H. and K.Y.L.; validation, J.H.A., S.H.R., B.Y.H. and M.K.L.; formal analysis, J.H.A., B.Y.H. and M.K.L.; investigation, J.H.A., S.H.R., S.L., S.W.Y., A.T. and M.K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.A., S.H.R. and M.K.L.; writing—review and editing, J.H.A., S.H.R. and M.K.L.; supervision, M.K.L.; project administration, M.K.L.; funding acquisition, M.K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program (2018R1D1A1A09082613) and Medical Research Center program (2017R1A5A2015541) through the National Research Foundation of Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Reuter S., Gupta S.C., Chaturvedi M.M., Aggarwal B.B. Oxidative stress, inflammation and cancer: How are they linked? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:1603–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butterfield D.A., Halliwell B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019;20:148–160. doi: 10.1038/s41583-019-0132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaribeygi H., Sathyapalan T., Atkin S.L., Sahebkar A. Molecular mechanisms linking oxidative stress and diabetes mellitus. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020;2020:8609213. doi: 10.1155/2020/8609213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitocco D., Tesauro M., Alessandro R., Ghirlanda G., Cardillo C. Oxidative stress in diabetes: Implications for vascular and other complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:21525–21550. doi: 10.3390/ijms141121525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giacco F. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ. Res. 2011;107:1058–1070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao D., Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia-induced reactive oxygen species increase expression of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and RAGE ligands. Diabetes. 2010;59:249–255. doi: 10.2337/db09-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefano G.B., Challenger S., Kream R.M. Hyperglycemia-associated alterations in cellular signaling and dysregulated mitochondrial bioenergetics in human metabolic disorders. Eur. J. Nutr. 2016;55:2339–2345. doi: 10.1007/s00394-016-1212-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maritim A.C., Sanders R.A., Watkins J.B. Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: A review. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2003;17:24–38. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rendra E., Riabov V., Mossel D.M., Sevastyanova T., Harmsen M.C., Kzhyshkowska J. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in macrophage activation and function in diabetes. Immunobiology. 2018;224:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghani U. Re-exploring promising α-glucosidase inhibitors for potential development into oral anti-diabetic drugs: Finding needle in the haystack. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;103:133–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joshi S.R., Standl E., Tong N., Shah P., Kalra S., Rathod R. Therapeutic potential of α-glucosidase inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: An evidence-based review. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2015;16:1959–1981. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1070827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umeno A., Horie M., Murotomi K., Nakajima Y., Yoshida Y. Antioxidative and antidiabetic effects of natural polyphenols and isoflavones. Molecules. 2016;30:708. doi: 10.3390/molecules21060708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin D., Xiao M., Zhao J., Li Z., Xing B., Li X., Kong M., Li L., Zhang Q., Liu Y., et al. An Overview of plant phenolic compounds and their importance in human nutrition and management of type 2 diabetes. Molecules. 2016;21:1374. doi: 10.3390/molecules21101374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang P., Li T., Wu X., Nice E.C., Huang C., Zhang Y. Oxidative stress and diabetes: Antioxidative strategies. Front. Med. 2020;14:583–600. doi: 10.1007/s11684-019-0729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Latocha P. The nutritional and health benefits of kiwiberry (Actinidia arguta)—A Review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2017;72:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s11130-017-0637-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Almeida D., Pinto D., Santos J., Vinha A.F., Palmeira J., Ferreira H.N., Rodrigues F., Oliveira B.P.P. Hardy kiwifruit leaves (Actinidia arguta): An extraordinary source of value-added compounds for food industry. Food Chem. 2018;259:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H.Y., Hwang K.W., Park S.Y. Extracts of Actinidia arguta stems inhibited LPS-induced inflammatory responses through nuclear factor-κB pathway in Raw 264.7 cells. Nutr. Res. 2014;34:1008–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heo K.H., Sun X., Shim D.W., Kim M.K., Koppula S., Yu S.H., Kim H.B., Kim T.J., Kang T.B., Lee K.H. Actinidia arguta extract attenuates inflammasome activation: Potential involvement in NLRP3 ubiquitination. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;213:159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim G.D., Lee J.Y., Auh J.H. Metabolomic screening of anti-inflammatory compounds from the leaves of Actinidia arguta (Hardy Kiwi) Foods. 2019;8:47. doi: 10.3390/foods8020047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn J.H., Park Y., Yeon S.W., Jo Y.H., Han Y.K., Turk T., Ryu S.H., Hwang B.Y., Lee K.Y., Lee M.K. Phenylpropanoid-conjugated triterpenoids from the leaves of Actinidia arguta and their inhibitory activity on α-glucosidase. J. Nat. Prod. 2020;83:1416–1423. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.9b00643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He R., Huang X., Zhang Y., Wu L., Nie H., Zhou D., Liu B., Deng S., Yang R., Huang S., et al. Structural characterization and assessment of the cytotoxicity of 2,3-dihydro-1H-indene derivatives and coumarin glucosides from the bark of Streblus indicus. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:2472–2478. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn J.H., Park Y., Jo Y.H., Kim S.B., Yeon S.W., Kim J.G., Turk A., Song J.Y., Kim Y., Hwang B.Y., et al. Organic acid conjugated phenolic compounds of hardy kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta) and their NF-κB inhibitory activity. Food Chem. 2020;308:125666. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin Y.L., Wang W.Y. Chemical constituents of Vernonia patula. Chin. Pharm. J. 2002;54:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma B., Guo H.F., Lou H.X. A new lignan and two eudesmanes from Lepidozia vitrea. Helvet. Chim. Acta. 2007;90:58–62. doi: 10.1002/hlca.200790021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timonen J.M., Nieminen R.M., Sareila O., Goulas A., Moilanen L.J., Haukka M., Vainiotalo P., Moilanen E., Aulaskari P.H. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory effects of a series of novel 7-hydroxycoumarin derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:3845–3850. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding H.Y., Lin H.C., Teng C.M., Wu Y.C. Phytochemical and pharmacological studies on Chinese Paeonia species. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2000;47:381–388. doi: 10.1002/jccs.200000051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoang L., Joo G.J., Kim W.C., Jeon S.Y., Choi S.H., Kim J.W., Rhee I.K., Hur J.M., Song K.S. Growth inhibitors of lettuce seedings from Bacillus cereus EJ-121. Plant Growth Reg. 2005;47:149–154. doi: 10.1007/s10725-005-3217-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park C.H., Kim K.H., Lee I.K., Lee S.Y., Choi S.U., Lee J.H., Lee K.R. Phenolic constituents of Acorus gramineus. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2011;34:1289–1296. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0808-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H.Z., Song H.J., Li H.M., Pan Y.Y., Li R.T. Characterization of phenolic compounds from Rhododendron alutaceum. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2012;35:1887–1893. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-1104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee Y.G., Cho J.Y., Kim C.M., Lee S.H., Kim W.S., Jeon T.I., Park K.H., Moon J.H. Coumaroyl quinic acid derivatives and flavonoids from immature pear (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai) fruit. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2013;22:803–810. doi: 10.1007/s10068-013-0148-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prachayasittikul S., Suphapong S., Worachartcheewan A., Lawung R., Ruchirawat S., Prachayasittikul V. Bioacitive metabolites from Spilanthes acmella Murr. Molecules. 2009;14:850–867. doi: 10.3390/molecules14020850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohlmann F., Chen Z.L., Schuster A. Aromatic esters from Solidago decurrens. Phytochemstry. 1981;20:2601–2602. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(81)83109-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Itoh T., Ninomiya M., Yasuda M., Koshikawa K., Deyashiki Y., Nozawa Y., Akao Y., Koketsu M. Inhibitory effects of flavonoids isolated from Fragaria ananassa Duch on IgE-mediated degranulation in rat basophilic leukemia RBL-2H3. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:5374–5379. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han J.T., Bang M.H., Chun O.K., Kim D.O., Lee C.Y., Baek N.I. Flavonol glycosides from the aerial parts of Aceriphyllum rossii and their antioxidant activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2004;27:390–395. doi: 10.1007/BF02980079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jeon S.H., Chun W.J., Choi Y.J., Kwon Y.S. Cytotoxic constituents from the bark of Salix hulteni. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2008;31:978–982. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lim E.K., Ashford D.A., Hou B.K., Jackson R.G., Bowles D.J. Arabidopsis glycosyltransferases as biocatalysts in fermentation for regioselective synthesis of diverse quercetin glucosides. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004;87:623–631. doi: 10.1002/bit.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fico G., Rodondi G., Flamini G., Passarella D., Tome F. Comparative phytochemical and morphological analyses of three Italian Primula species. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:1683–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He Z., Lian W., Liu J., Zheng R., Xu H., Du G., Liu A. Isolation, structural characterization and neuraminidase inhibitory activities of polyphenolic constituents from Flos caryophylli. Phytochem. Lett. 2017;19:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.phytol.2016.12.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calzada F., Cedillo-Rivera R., Mata R. Antiprotozoal activity of the constituents of Conyza filaginoides. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:671–673. doi: 10.1021/np000442o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wan C.P., Yuan T., Cirello A.L., Seeram N.P. Antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory phenolics isolated from highbush blueberry flowers. Food Chem. 2012;135:1929–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pizzolatti M.G., Venson A.F., Junior A.S., Smania E.F.A., Braz-Filho R. Two epimeric flavalignans from Trichilia catigua (Meliaceae) with antimicrobial activity. J. Biosci. 2002;57:483–488. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-5-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim T.H., Ito H., Hayashi K., Hasegawa T., Machiguchi T., Yoshida T. Aromatic constituents from the Heartwood of Santalum album L. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:641–644. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fang J.M., Lee C.K., Cheng Y.S. Lignans from leaves of Juniperus chinensis. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3659–3661. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang W., Wang J. In vitro antioxidant properties and in vivo lowering blood lipid of Forsythia suspense leaves. Med. Chem. Res. 2010;19:617–628. doi: 10.1007/s00044-009-9217-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moon S.S., Rahman A.A., Kim J.Y., Kee S.H. Hanultarin, a cytotoxic lignin as an inhibitor of actin cytoskeleton polymerization from the seeds of Trichosanthes kirilowii. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:7264–7269. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data is contained within the article or Supplementary Material.